Kristine H. Harper's Blog, page 6

April 3, 2022

The Butterfly

This post consists of a short extract from my new book Anti-trend. It is taken from Chapter 5: Three Anti-trendy Reasons for Designing New Objects in a World With Way too Many Things – and is interlinked with the conversation Liina Klauss and I had at our combined film premiere and book launch last Friday at The Bridge Green School.

I hope you will enjoy!

***

The butterflyAs initiated in the beginning of this subsection, designing for longevity and a long product life might not be the only way to create sustainable things. Designing objects with a short lifespan could be an alternative sustainable design approach that would enable and encourage people to live sustainably, and to enable people to do so in a more playful or light-hearted manner.

Long-lived objects are dependent on consumers being willing to invest in quality, thoroughness, innovative solutions, and in handmade crafts. Creating long-lived objects is time consuming, and the price tag should reflect that. However, investing in durability is not possible for everyone, and being able to afford doing so or being well-informed or well-educated enough and consequently in a position to make qualified choices and to prioritize sustainability tends to increase inequality and discrimination in a society. Because, the superior feeling of consuming and living sustainably tends to go hand in hand with a condescending division between “them”—the ones who shop carelessly, or the ones who don’t know any better and ignorantly pollute our environment—and “us”: the ones who are well-informed and who prioritize sustainability; who don’t compromise when it comes to ideals or image; who would not buy single-use plastic bottles or use plastic straws; who would not purchase fast-fashion clothes; who buy carbon offsets when flying; who drive electric vehicles; who don’t buy plastic toys for their kids; who only invest in beautifully crafted furniture; who holiday only in ecological resorts, etc. All of these are expensive ways of living sustainably.

In other words, sustainable consumption and living has unfortunately become yet another elitist way of increasing the already gaping gap between the rich and the poor, between cultivated and uninformed, between educated and unsophisticated, between enlightened and ignorant, between the politically correct and the “inconsiderate.” Mending that gap might be one of the most important tasks for the sustainable designer, and a way of doing that might be the creation of sustainable, short-lived, affordable design-objects.

Liina Klauss, Perpetual Plastic, Bali 2020

Liina Klauss, Perpetual Plastic, Bali 2020

Designing single-use items or products that adhere to fleeting trends out of materials that last for a long time is actually kind of bizarre. Despite this being common practice, it is a flaw. How can designing single-use straws and bags out of plastic and short-lived flip flops out of imperishable foam rubber have become custom? Why is creating trend-based stuff that is intentionally made to be fleeting out of resource-demanding natural materials like cotton, wool, hardwood, or out of synthetic materials that cannot deteriorate naturally—like polyester, nylon, rayon, or polyethylene—be considered business as usual? If you think about this in a logical manner, designing something for short-term usage out of materials that can last for hundreds of years is erroneous and should be considered a design error.

So, should designing single-use products meant for short-term usage be banned? Well, yes that would be one way to eradicate this problematic situation. But since that is neither realistic nor necessary let’s look at another way of getting around the problem of trash and discarded things building up in oceans and landfills due to trend-based planned and perceived obsolescence.

This morning my youngest son found a big, blue dead butterfly lying on our bedroom floor. He was delighted: the butterfly’s short life ending right there in our bedroom felt magical and beautiful. Now it is afternoon, and ants have already started to ingest it, and in a couple of days it will be gone completely. The other morning the large cocoon on the wall of our bathroom was empty; the butterfly had left it and had flown away. This is the natural cycle of life. Florae and faunae alternate or deteriorate, two terms and tactics that are the inspiration for the sustainable design strategy that can lead to the creation of resilient, anti-trendy design-objects.

In order for a sustainable design-object to be long lived it must be alterable (flexible, adjustable, upgradeable, repairable, or aesthetically decayable), and in order for a sustainable design-object to be short-lived, it must be able to naturally deteriorate.

March 16, 2022

Encouraging Usage

This post consists of another short extract from my new book Anti-trend. It is taken from Chapter 3: Anti-trend and Authenticity. Considerations on what good design really means.

I hope you will enjoy!

***

Let’s return to the term usage that I am suggesting as a replacement for consumption. In my handling of the word usage, I am not solely referring to the usability or the practical, functional qualities of an object. Actually, when you purchase objects for long-term usage, you should avoid solely buying an item because it fulfils a practical need of yours—the need to cook, dress, or transport yourself. This dimension of an object’s properties is obviously important, but a lot of our dearest belongings are not exclusively practical items, but items that also please us aesthetically—or, they are both functional and aesthetically nourishing. I have eloquently elaborated on the aesthetic dimension of objects and the importance in Aesthetic Sustainability. But, in relation to usage, the aesthetic dimension is so crucial that we cannot avoid bringing it in focus in this context as well.

Basically put, if you invest in things that nourish you aesthetically, you will be less inclined to experience them as obsolete when they have been consumed—or are no longer functional or appear worn and weathered, or when the fashion trends have shifted—and more inclined to repair them. You might find yourself more motivated to creatively focus on the usability of the object; maybe you will even find that it can be used for more than the one thing it was bought for. The aesthetically nourishing dimension of an object often leads to an emotional bond between the object and the user or owner. If an emotional bond arises, mindlessly discarding the particular object becomes next to impossible.

Embroidered jacket made from recycled tablecloths by Danish La Femme Rousse

Embroidered jacket made from recycled tablecloths by Danish La Femme RousseWhen you are about to buy something next, try to stop for a moment and consider how you will get rid of it again. The things that pro- vide you with a quick “consumer-fix” are often the ones you will want to get rid of the fastest because they are rapidly experienced as insignificant and trivial, but the things that give you a quick feel-good fix are usually the hardest ones to get rid of because no one wants to buy them as second-hand items, and no one wants to receive them as hand-me-downs. Think of that quick-fix trendy dress you bought before a party, or that cheap easy-chair that wasn’t exactly what you wanted but was bought to fill that void in your living room, or that new pedometer gadget, which at the time felt so important, and that now just stays in your drawer. We are all guilty of such irrational consumer ventures, and we all know how short-lived their pleasure is.

An important question to raise in this context is: What does it take for an object to encourage usage, mending, sustaining, and repairing?

We should demand something from the objects we are surrounded by. Sustainable objects shouldn’t be designed to make our lives easier but to question the way we do things—to make us stop and think, remain critical, reconsider and change if necessary, and be present and appreciative. Obviously, we should be willing to pay more for such well-thought-out objects than for mass-produced, trend-based things. Using the term investing rather than shopping might be the first step.

***

January 24, 2022

The Abandoned Amusement Park

This post is another extract from my new Uncultivated book project. As previously described the book is built up around negations of “the ten commandments of cultivation”. The intention herewith is to challenge taken-for-granted cultural and societal “truths” and assumptions and to promote a rewilding of the cultivated human being.

The ten commandments are the following:

We have to adapt and behaveWe are superior to animalsWe are separated from natureWe must be ambitiousWe have to work hardWhat cannot be explained is not trueWe do not talk about deathDecay must be defeatedTime is linearGod is deadIn this post I will share another passage from the section: What cannot be explained is not true. This section is a description of an eerie experience I had this weekend together with my oldest son.

Sometimes what cannot be explained is true.

***

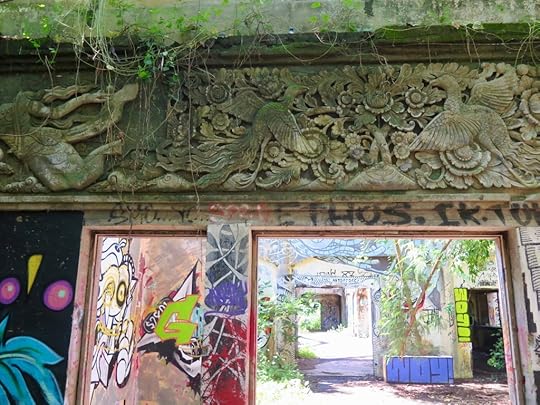

What cannot be explained is not trueI am riding my motorbike with my 14-year-old son on the back on a steaming hot Sunday from our house in the jungle towards the coast. The destination is an abandoned amusement park called Taman Festival Park that has apparently been taken over by tropical nature and graffiti art. We have no idea what to expect. I was tipped by a friend to check it out and have done a quick google search to find the location and seen a few intriguing photos. When we arrive at the empty parking area by the entrance to the park, we are met by a man who claims that we have to pay an entrance fee to him. As the amount is not unreasonable, and I am not in the mood to negotiate we pay him, and he points up some stairs and says: you can enter up there and adds (to our amusement) good luck. The ticket booths are covered in graffiti and the glass is shattered. We pass them and continue through the entrance gates.

Strangely there are no dogs in the park. Stray dogs are everywhere in Bali, and as we enter the parking area, we see a bunch of scruffy looking dogs roaming the beach, but for some reason the park is completely dog less. The only living creatures we encounter are a multitude of mosquitoes, piles of wriggling centipedes, swallows and bats. Besides therefrom the park is cleared of visible life. A couple of other visitors are here; two young men with cameras, who are leaving as we enter, nodding at us quietly as a greeting. The atmosphere is eerily peaceful. The only sounds are the howling winds and the ocean.

As we walk further into the park we are met by enormous ruined buildings with shattered windows and missing roofs. Vines, tropical flowers, and large branches with giant leaves are growing in and around them, and the broken concrete walls are covered in colorful graffiti art; some of it absolutely amazing. We are both in awe. The beauty of the decay combined with the lush tropical plants and the colorful graffiti is breathtaking. We are quietly taking photos and walking slowly through what used to be a huge atrium. The stairs to the second floor are still partly intact, yet overgrown with green leaves, so we carefully walk upstairs. The view of the vast ocean and the colossal ruin covered in greeneries that meets us is sublime, breathtaking.

We leave the ruined atrium and walk into a square with a shattered fountain in the middle. One can sense the grandeur that this place must undoubtedly have had when it was just built. Another massive building is facing the square and as we approach and are met by an intimidating graffitied snake, we realize that it is the remains of a movie theater. We can enter the darkness of the ruined cinema but feel reluctant. Every intuitive hunch in us screams: no!

We decide to continue and pass through a gate covered in thick vines and leaves and enter a courtyard. Strange holes are dug in the soil – they look like freshly dug graves and my son and I send each other a bewildered look. What are those holes for? He asks me. No idea, I say, should we leave? No, it’s ok, lets walk through here and check out the building over there. He points to some wide steps that lead up to a massive decaying building with a surrounding colonnade. I hesitate for a bit and then nod at him. As we walk through the courtyard, we pass a tall chapel-like building which, strangely, isn’t plastered in graffiti. Plants have almost completely taken over its walls and tropical vines are hanging from the roof. There is a small overgrown passage next to it, and as we look down it suddenly an orange scooter driven by an old Balinese man with grey hair passes. A small boy is sitting on the back of the scooter holding on to the old man. They pass, and then disappear. And we think nothing of it at the moment.

As we walk into the grand crumbling colonnade surrounding the massive structure swallows fly out towards us, and bats are hanging from the ceiling. I am really not a big fan of bats, and my son knows, but he says: let’s just check out the open area, then we can leave. I nod, and we continue. The ground of colonnade is covered in rainwater and the graffitied walls are reflecting in the water giving the sight an illusion of abolition of up and down. We walk into the massive demolished center of the building; the iron structure is the only thing still standing and loose pieces of timber are hanging from it, giving it a very unsafe look.

When we leave the area and walk back through the overgrown gate, into the sunlight and away from the swarms of mosquitoes that harass and bite us in all the shadowed areas, my son suddenly says: where did that man disappear to? What do you mean? I reply. There was a man standing right there – he points to a clearing – he was right there, wearing a grey shirt, but now he is gone. Did you see him? I shake my head. That is strange, my son mumbles.

We walk slowly towards a few more graffitied shattered buildings, take some photos, and then decide we have had enough. We are both quiet, contemplating. As we ride home, we both exclaim: holy s…, what was that place all about?!

After returning home we are so filled up with the overwhelming impressions from the park that we begin to frantically read everything we can find about it. The story of Taman Festival Park is insane. The 9-hectare amusement park that sprawls along the southern coast of Bali was built in the late 1990’s by the Indonesian government as a major tourist attraction. The park was to feature a fancy 3D theatre, an erupting model of a volcano, a swimming pool planned to be the largest in Bali, an inverted roller coaster, and a crocodile pit. However, on a Friday (the 13th, as a matter of fact!) in March 1998 lightning struck the park and destroyed the expensive laser equipment as well and some of the buildings. Insurance didn’t cover natural disasters and the park was never completely finished and never opened. The park has now been abandoned for over two decades and has been more or less swallowed by the jungle.

We also read about visitors being observed and followed from a distance as they walked through the park – by a young boy with a shaved head and by a skinny man – only to lose sight of their followers as they reapproached the entrance/exit. And about how these visitors after returning home fell sick and were bedridden for days. We read about the park being the most haunted place in Bali: about the spirits (some evil) that roam the park, and about how locals never enter, because, as they say: nothing living ever comes out of there. We read about how locals do offerings that include animals (chickens, goats and pigs) every fortnight at entrance area of the park to ensure that the spirits stay content and remain within the park. And about how those offerings are always gone when they return in the morning. We read stories about the crocodiles that were left behind when the park was deserted and about rumours that the crocodiles initially were fed chickens by local farmers, but later started eating each other as well as humans. It is said that the last crocodiles were finally removed, but this has never been confirmed (and I start to wonder why there absolutely no dogs in the park). These stories all add to the unease that we both felt when we were in there; a feeling that made us stick close to the entrance area and forced us to comprise our curiosity to explore more and wander deeper down the overgrown paths of the park.

And then suddenly my son reads a story on a custom motorbike and vintage scooter show that was held in the park just as it was about to open its doors to the public. He turns completely pale and starts to shake. I immediately know why. The orange scooter we saw with the old man and the child wasn’t of this world, and we both immediately know that this is the truth: it isn’t possible to ride a scooter through the overgrown area behind the chapel-like building that borders the massive ruined building behind it. And as soon as the scooter passed us its sound disappeared. I am never going back there ever again, says my son.

I cannot explain what we experienced. But it was real.

January 17, 2022

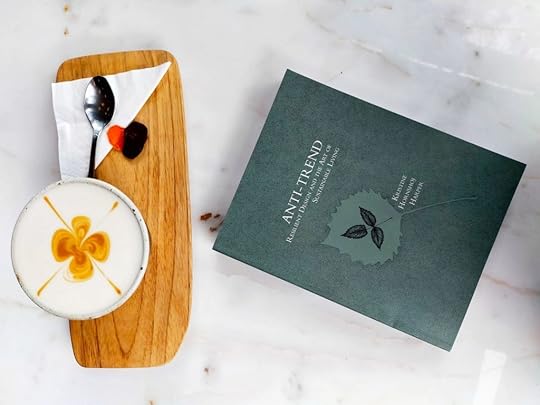

Anti-trend, Resilient Design and the Art of Sustainable Living

Today my new book “Anti-trend – Resilient Design and the Art of Sustainable Living” has finally been released and is now available worldwide.

I bring you here the introduction to the book:

Introduction

IntroductionThe overall purpose with this book is to encourage designers and consumers to take responsibility for overproduction and overconsumption, and to alter unsustainable production and behavioral patterns. There is a current need for responsibility to be taken, and for action. A collective need that unites us all worldwide as a “we.” Hence, when I use the term we I mean both the creatives, who have the power to shape our reality and influence future ways of living, and the consumers, who have the authority to alter and change demands. We need to understand that we can all make a difference, and that no step toward a more sustainable and resilient world is too small. We need to enable sustainable innovators to lead the way by daring to change our ways. We need to believe that when our intuition tells us that somethings is wrong, maybe it is wrong. We need more civil engagement, or even more civil disobedience. We need more products that empower workers and artisans, and much less growth-thinking in order to turn around the environmental crisis that we are facing. We need resilience and anti-trend as opposed to consumption that encourages fleeting trends. We need long lasting, aesthetically nourishing design-objects that can inspire us to buy much less. And we need sustainable short-lived objects that can satisfy our fleeting needs. We need sustainable living solutions that can enable us and our natural environment to flourish. We need sustainable pioneers who can arouse a need in us to shake up our habitual ways of life, which tend to revolve around work and consumption. We need more friction and less “smoothness” and convenience. We need more purpose, more commitment, more heaviness and less insignificant lightness. We need to embrace change and celebrate diversity. We need community-feelings and shareable products and living solutions rather than greed and selfish “Ark”-builders. We need all of this, and so much more. And this book is my attempt to provide a small slice of this cake.

Through an investigation of anti-trend as opposed to volatile trends the importance of pursuing anti-trend and resilience in life in general and in relation to the creation of sustainable design-objects and living solutions is underlined. Hence, the anti-trend investigations navigate through two main focal points: anti-trendy living and the anti-trendy design practice. Establishing a sustainable lifestyle and designing durable products have one very important thing in common: they revolve around the formation of an enduring core that can function as a stable, yet flexible foundation for actions and usage.

The book contains an inherent “supply and demand” logic, which in short can be described like this: in order for the supply or creation of sustainable design solutions that encourage resilient living to raise, the demand for resilient, sustainable products must increase, and vice versa. The creation of sustainable solutions and the need therefore are in other words intertwined.

In my perspective one of the most important and vital ways of overcoming and turning around the immense environmental problems we are currently facing worldwide is radical reduction of consumption. When I write consumption, I mean it in the most straightforward sense of the word: buying too many things and going through and getting rid of them again way too quickly. The fashion industry alone emits more carbon than international flights and maritime shipping combined, and in addition hereto, think about the production and consumption of furniture, home accessories, toys, and other knick-knacks. However, despite the fact that altering our habitual consumer ways might sound easy, it ap- pears to be unbelievably hard. Even though we are bombarded with horrific and very tangible scenarios involving starving polar bears, whales with plastic-filled stomachs, and burning rivers, and even though these images are presented as interlinked with overconsumption, we continue to shop and we continue to discard the majority of our belongings way before they don’t work anymore or are worn out, and hence we continue to add to the mountains and islands of trash that are building up in landfills and in oceans. Why? Because we are evil? No, of course not. Rather, the reason could be partly interlinked with an increasing detachment from our physical, natural environment and partly with the fact that habits are hard to change, particularly when engulfed in a busy daily routine. Furthermore, our lack of sustainable action is likely connected to the fact that status symbols are to an extent associated with new, glittery things, and to the constant craving for more that seems to govern our late-modern minds and societies, as well as to the despair that this entails. Therefore, a significant part of the book is dedicated to an investigation of despair as well as authentic, sustainable living as an antidote. Other parts of the book are committed to solutions: to an investigation of how objects and living solutions can encourage fulfilled, sustainable, resilient living with less; and to parse the three legitimate reasons for creating new products in a world that is already overflowing with things, product-waste, and the anti-trendy design-object.

However, before getting started, allow me to serve a small foretaste of each chapter as well as a structure-overview. The six chapters of the book are interlinked in pairs: Chapter One and Two’s mainly focus on anti-trend analysis of cultural and societal tendencies toward sustainable living. The methodology presented enables the researcher to differentiate between trend based, fleeting and deeply felt, durable needs and longings. Chapter Three and Four are devoted to an investigation of what it means to live authentically. The underlying hypothesis of the chapters is that overcoming despair leads to a more sustainable lifestyle and hence reduces overconsumption. Furthermore, these chapters investigate the importance of raw, “heavy” aesthetic experiences in relation to human well-being and sustainable living. Chapter Five and Six are devoted to defining the resilient design-object. These chapters dive into the reasoning for designing new things in a world overflowing with stuff as well as a concrete definition of the properties and characteristics of the resilient, anti-trendy design-object. In other words, the overall structure of the book goes like this: chapters One and Two: anti-trendy research; chapters Three and Four: authentic, sustainable living; and chapters Five and Six: the resilient design-object.

January 11, 2022

Creating Resilient Design-objects

As promised, I will share extracts from Anti-trend in the time prior to the official publication of the book – which is very soon (in less than a week actually!)

In this post, the paragraph from Anti-trend is taken from the last chapter of the book, Chapter 6: The Anti-trendy Design-object.

I hope you will enjoy!

***

Creating Resilient Design-objectsWe are at a stage now at which sustainable technology, material development, and products that can enable us to reduce our damaging impact on the natural environ- ment already exists. Still, we seem unwilling to alter our lifestyle. Sustainability appears to have become a matter of sustaining or maintaining our present existence and routines—enabling us to continue to live, act, shop, travel, and eat the way we always have. Recycling systems, sustainable waste management, and the countless numbers of online platforms for the sale of second-hand goods legitimize and justify our continuous consumer-venture, and even enable us to label it as sustainable. Sustainability has become another word for stagnation or for immovability in the sense that we purchase sustainable products and pursue sustainable lifestyle solutions that allow us to continue down the same path of overconsumption and capitalistic growth, only in a slightly “greener” way. It is all mostly business as usual, with the only difference from “old school” capitalism being the label of “sustainable.” This kind of sustainability is static, or, perhaps more correctly, it is stuck. It might appear circular in the sense that some kind of circulation takes place: things get bought, consumed, and either resold, downcycled, and made into scraps to be used for some insignificant purpose, or converted into vouchers to be used to purchase new things—yet another way of legitimizing continuous overconsumption. But this kind of circularity is not real, and it is not sustainable or aligned with the circularity that can be found in nature. The vast majority of the things that are consumed and that the user is done with end up in landfills, emitting toxic gasses as they slowly fade and vanish, or they fill our oceans, lakes, fjords, and rivers with polluting trash.

In nature there is no waste. Leaves that fall from a tree nourish the soil that they fall into. A decomposing tree trunk becomes home for insects and small mammals. An animal that dies turns into food for another animal or it deteriorates and fertilizes the earth. Decomposing fruit is eaten by ants and other insects. In a natural circular system everything is always altering, always in flux; nothing is wasted, and nothing is superfluous. As a part of the fake sustainability circularity narrative, we are told that something similar to nature’s ingenious waste-management system is happening. The truth is that static things made to fulfill a temporary consumer need to fit in, feel trendy, or be pampered are not reusable. They turn into the trash the second they are cast off.

One of the main problems with the way we are currently consuming, which is excessive and gratuitous, is the way the things we consume are designed and the amount of waste produced. What is needed is fundamental change; a radical reduction of consumption since the overconsumption of things that are quickly perceived as obsolete, despite them being made out of long-lasting materials is what has led us to where we are now. We need to practice a lifestyle that is not only slightly, but al lot greener. We need to pursue alternatives to the status quo rather than convulsively hold on to what we are used to and familiar with. Our current codes of conduct, status symbols, and behavioral patterns in relation to consumption are outdated and guilty of destroying our ecosystems and draining our natural resources. They are, as previously discussed, guilty of leading to despair, oppression, and increased inequality between populaces. Instead of buying carbon offsets we should travel by airplane less. Instead of returning our castoff clothes to fashion-stores in order to receive vouchers to purchase new rags we should reduce our clothing consumption radically. Instead of applauding people’s economic ability to buy yet another updated version of a perfectly fine object we should praise the beauty of well-made, long-lasting, well-functioning artifacts and creative mends. And instead of craving and demanding an even flow of new, flashy products made of virgin materials we should request products that encourage sustainable living by being made of recycled materials, that are upcycled from discarded products, or are made to be swapped or shared or to sustainably deteriorate.

Metaphorically speaking, what we are doing right now is like insisting on building a tropical waterpark in a desert, even though this is obviously immensely straining on the natural resources available, and despite the fact that it goes against the physical qualities and local resources of a desert. We will not accept and respect natural limitations, and we generally refuse to be restricted by lack of resources and local reserves. Deserts are a particularly good metaphor in this case because they appear to be useless to human beings. But despite a desert’s seeming uselessness in relation to the livelihood of humans, deserts are vitally important to the earth’s ecosystem, just as the artic sea pack is and just as rainforests are. Furthermore, if usefulness is a focal point, making use of desert land for harvesting solar energy or minerals rather than for constructions that are better fitted elsewhere should be the way forward. A good example of naturally sustainable usage of land is the rice fields in Bali that most typically are built on hills, ridges, or mountainsides that naturally have springs running through them or water running down from elevated lakes or streams—natural irrigation. This is a prime case of understanding and respecting a landscape or “listening to its soul” and its natural flow before farming it, creating constructions on it, or in other ways altering it to make it inhabitable or “useful” to human beings.

Ricefield in Sudaji, North Bali

Ricefield in Sudaji, North BaliWhen it comes to sustainable design solutions and sustainable living, a similar perspective is needed. We need to make use of land that has natural springs running through them to farm rice—symbolically speaking. The direction we are headed right now is leading us to proprietary obesity: it seems that we continuously over-consume and then feel weighed down by our belongings, which forces us go on a diet. We tidy up—we might even hire experts to help us do this—we throw a bunch of stuff away, we cherish minimal living for a while, only to find ourselves “overeating” soon again. All the alluring and very affordable offers are apparently just too tempting. The sudden bursts of minimalistic needs are apparently not sustainable, maintainable, or satisfying.

My blessed, minimalistic workspace. My sanctuary. My space for daily nourishing rhythms of writing and reading.

My blessed, minimalistic workspace. My sanctuary. My space for daily nourishing rhythms of writing and reading. The current consensus appears to be that improvements and progress are the equivalent of making things more comfortable, smoother, and more convenient by minimizing friction and heaviness. However, design improvements could and should ideally mean something entirely different. Improvements should increase the tactile experience and foster a tangible bond between object and owner. They should challenge the user’s senses and mind and induce more heaviness, in the most nourishing sense of this term (as previously discussed). They should encourage the user to repair and maintain an object or perhaps even to share it with others. Or they should activate the user and engage her or him in communal or sustainable actions.

Before designing yet another slightly better, slightly more convenient, slightly more streamlined, slightly easier to use version of a phone, a chair, a jacket, or a bowl for that matter, the sustainable designer should question the very inclination for this task, by asking the following question: What can legitimize designing something new? Are minor improvements or increased convenience a good enough reason? I wrote extensively about this in the previous chapter, but the question is worth once again emphasizing and elaborating on. Can you, literally and metaphorically speaking, legitimize replacing your entire kitchen because you want new cupboards that don’t make any noise when you close them, and because you cannot solely change the cupboards, since the other kitchen elements won’t mix and match? The new countertop has to have a skinnier, smoother surface than your old one. Can that in any way be an appropriate reason to improve one’s belongings in a world with scarce resources? Does today’s common consumer really need more convenience? Is the transition to smart everything and focusing on accessibility and user-friendliness above all really necessary?

(…)

January 4, 2022

Designing new objects in a world with way too many things

My new book Anti-trend will be published very soon (and can already now be pre-ordered). I am so excited to start the new year with this book publication and am looking forward to finally sharing all of my anti-trend theories with you.

In this and the following posts I will share short extracts from the book to give you a foretaste of the themes and discussions.

This post consists of short extracts on the sustainable value of sharing objects from Chapter 5: Three Anti-trendy Reasons for Designing New Objects in a World with Way too Many Things This chapter is split up into the following main sections:

Waste Materials, Deconstruction, and UpcyclingSustaining and EmpowermentEncouraging Sustainable LivingThe following extract is taken from section on encouraging sustainable living.

***

Encouraging Sustainable Living(…)

With this in mind, the third and last legitimation for designing new things in a world overflowing with discarded objects is to encourage sustainable, resilient living—and to demonstrate that it is possible to turn around the current state of affairs. To provide consumers with sustainable options and solutions; solutions that are available to all—not just to the fortunate few or to the elite—and solutions that inspire us to consume less, share more, and pursue a more fulfilling, resilient lifestyle. I state the latter because over-consumption and greediness in my perspective often occur out of dissatisfaction and the unfortunate “logic” that prosperity equals financial growth and a constant increase in material properties. Overconsumption and a buy-and-throw-away mentality is at the one end of the scale of the aforementioned golden mean, whereas nihilistic refusal and turning away from society altogether is at the other end. We need to find a balance. We need to seek durable permanence. We need objects that can satisfy our inherent need for beauty and aesthetic nourishment—in a sustainable manner.

I will be investigating the following three ways to encourage sustainable, resilient living based on product or concept design in this section: 1. collaborative consumption: swapping, sharing, and repairing; 2. long-lived and short-lived products; and 3. the open, raw design-object. These three approaches to sustainable design have the overall purpose of making it possible, attractive, accessible, and affordable for the common consumer to live as sustainably as possible. Furthermore, their objective is to encourage sustainable living by generating the empowering feeling of not being too small or insignificant to make a difference, no matter how vast the environmental problems might seem—as well as highlighting the beauty and the fulfilling feeling of wanting to make that difference.

***

Collaborative Consumption: Swapping, Sharing, and RepairingInstead of trying to convince consumers to buy less and focus on investing in better objects, maybe encouraging sustainable behavior by nudging them into wanting to do so and to share and repair their things would be a better and more effectual and durable approach. Because, despite the evidence of pollution and global warming and the link between these devastating scenarios and overconsumption, consumers don’t really seem to act or change their behavior; or at least, not enough do, and not on a large enough scale. There is still a large demand for cheaply produced goods, and the manufacturing industry still seeks to meet that demand by producing more stuff quicker and cheaper. The fast fashion industry emits more carbon than international flights and maritime shipping combined, more than 15 tons of textile waste is generated each year in the United States alone, and the number has doubled over the last 20 years, only confirming that increased pollution and global warming doesn’t scare consumers away from shopping for cheap clothes. Polyester clothing takes nearly 200 years to decompose and nylon is not much better, while they continue to release microplastic into the environment. It takes approximately 2,700 liters of water to make a cotton t-shirt, which becomes an even scarier scenario when understanding that globally, more than one in three people does not have access to safe drinking water.

In other words, the environmental impact of mass-produced clothes is huge—almost immeasurable. The production of low-priced toys, kitchenware, interior accessories, etc., is equally pollutant to add to that.

So, if alarming facts about pollution caused by fast fashion are not encouraging enough to alter consumption habits, perhaps the sustainable product designer’s main task is to seek new approaches to encourage sustainable behavior. But, how do you make people want to change their ways, rather than inform or scare them into doing so?

In general, consumption needs to be reduced massively. Investing in long-lasting things, or perhaps sharing or swapping things rather than using and throwing them away, should ideally be the norm. However, what does the prospect of being a long-term investment require from design-objects? And can any object be a shared object? The short answer to the latter question is: No, I don’t think so. And in this subsection, I intend to clarify why I don’t, and what it requires from an object to be swapped or shared and repaired.

Simply put, the main motive for overconsumption is the sensation that what one already owns is somehow obsolete. Maybe it is no longer functioning, and repair seems impossible—perhaps due to the design or to lack of access to the tools and/or skills needed—maybe it is weathered and worn out, or perhaps it still works fine, but it somehow feels wrong and is perceived as obsolete. A majority of the belongings of a 21st-century person are discarded due to perceived obsolescence, not because the products don’t work anymore or are worn out. So, if perceived obsolescence is one of the big sinners when it comes to the landfills filled with unwanted stuff, what does it take to eliminate this mechanism? What are the characteristics of objects: clothes, furniture, interior accessories, etc., that can continuously satisfy our need for newness? A newness that opens the door to the idea of sharable or swappable goods. Or are we looking at this wrong? Should the question rather be: How can the constant need for newness be eliminated?

(…)

Let us for a short while imagine a world in which collaborative consumption is the norm. A world in which sharing clothes is normal, a world, in which owning very little stuff is status-providing, a world, in which purchasing something new involves responsibilities—to ensure that it is used well and passed on to others, when one is done with using it—rather than rights: to do whatever one wants with one’s belongings, and to throw them away when bored with them. A world, in which immaterialism rather than materialism governs consumption. In this world a range of new objects are needed. Objects that are sharable and collaboratively consumable, objects that can endure the extensive usage, that can be mended and updated, and that can circulate amongst and satisfy a group of owners due to flexibility and aesthetics.In other words, not all objects can be collaboratively consumed or shared. It requires certain object-qualities to be resilient enough to be co-owned. What exactly does it require? Adaptability? Subtleness? Does a sharable object need to have a modular structure so that single elements can be replaced if they no longer work or if they get worn out? It most certainly requires a degree of hardiness, because when an object is used by many rather than one, it obviously wears more rapidly. There are requirements in relation to the materials used when creating sharable objects. However, robustness can also take the shape of wearability and fit, if talking about garments; or of flexibility and size-adjustment, if talking about furniture; or of subtle aesthetics that ensure mixability with other items. These are qualities that ensure longevity.

(…)

December 13, 2021

Uncultivated: What cannot be explained is not true

In my previous post I shared an extract from my new Uncultivated book project. The book is built up around negations of “the ten commandments of cultivation”. The intention herewith is to challenge taken-for-granted cultural and societal “truths” and assumptions and to promote a rewilding of the cultivated human being.

The ten commandments are the following:

We have to adapt and behaveWe are superior to animalsWe are separated from natureWe must be ambitiousWe have to work hardWhat cannot be explained is not trueWe do not talk about deathDecay must be defeatedTime is linearGod is deadIn this post I will share a passage from the section: What cannot be explained is not true. This specific section is a description of an experience I had a couple of months ago in North Bali.

Sometimes what cannot be explained is true.

***

What cannot be explained is not trueLosing a loved one is horrible. Especially if that someone is taken away too early. Last week the neighbour of our Balinese friends died. She was only 34 years old and left behind a husband and a 5-year old son. What happens in Bali when someone dies is really quite remarkable. Especially when coming from an individualistic each-to-their-own-culture like my own western European one.

The day after the young woman died nearly 200 people stopped by the family’s home – bringing their condolences alongside money, cooked meals, rice and offerings. People would come and go and stick around for a while to cry or talk or just sit and be still together. And, to my wonder this went on for the coming 7 days. Family, friends, and neighbours (and not only the closest neighbours, but basically the entire village) would come and go; sit around and talk, offer a shoulder to cry on, tend to the little boy who lost his mother, cook some food, share a meal, a cookie or a cup of coffee, prepare offerings for the family temple, clean, wash dishes, or just sit in silence. The husband and his son were never alone. Not for one minute. And I could see it soothed them.

The deceased young woman was, as a parenthesis, buried on the second day after her death. Before the burial she was carefully cleaned, embraced and dressed by the neighbour women. She will be cremated later on when the family has saved up enough money to pay for the cremation ceremony (which is a costly affair here in Bali).

Then on the 8th day after the death of the young woman the closest family and neighbours went to a shaman. My husband and I were invited to join, not knowing what to expect. The shaman of the region in which the village our fiends is located in is a woman in her 50’s. When we arrived at her house there were already a lot of people there, and as we were coming in we met a man who was leaving, and who greeted us with teary eyes, saying: I spoke to my father. I am convinced it was him talking to me through the shaman; the way her mannerisms changed when his spirit entered her body, and the way she smiled, and of course the things he said to me through her – there is no doubt! Good luck, he then added and rushed out, filled with emotions and with eyes full of tears, needing to contemplate in solitude.

We went in only to be met by more teary, emotional people. I was not sure what to think. Everything in me tried to negate this experience – my culture’s voice was instantly turning critical and rational and explaining to me what was going on by saying: these people just lost someone dear to them, and they need to believe that this is true.

We were taken into a small room with a group of people, among them the widower and the young son as well as our friends. The shaman started chanting with closed eyes. Incense filled the room and everyone looked down quietly. After a while the shaman opened her eyes and started talking, addressing an elderly woman in the back of the room. Everything was happening in a mix of Balinese and Indonesian, so I wasn’t understanding a lot of the conversation, but my friend was explaining to me that it was the woman’s husband who was talking to her through the shaman. The woman was clearly affected and had many questions for the deceased husband.

And so, it went on. The shaman would address people in the room and talk to them as the spirits of the deceased loved ones would enter her body. Her mannerisms and voice would change, and on several occasions, she had concrete messages from the deceased; for example a man was told to take out the healing stone that his father left him (which he apparently never knew how to make use of) from the cupboard where he had stored it and give it to his son, because he would know how to use it. Another man was told to read the book that was left for him by his father, as now was the right time for him to understand its wisdom. And a woman was told by her deceased husband that he knew she was apprehensive about coming to the session, but that he was grateful that she did, and that he was still here with her looking out for her. There were tears and there was laughter.

The shaman contemplating in silence after the session

The shaman contemplating in silence after the sessionThen suddenly the tone, or rather the atmosphere changed. A sigh passed through the room, as the shaman looked directly at the little boy who recently lost his mother, and who happened to be sitting right next to me. She was starring at him, and tears started running uncontrollably down her cheeks. Until now she hadn’t cried, not once, but now she was sobbing and reaching out for the little boy. Anak saya, anak saya, she kept saying (my child, my child). And then she started talking to the young widower who was sitting right behind the little boy. She was very upset, and constantly holding her head telling him about all the pain she had (the young woman had had a tumor in her head for years and a seizure had caused her death). The husband was crying, and the little boy was terrified and got up to run out of the room – out to his grandparents who were sitting in the door opening. The shaman tried to grab him to hug him as he ran out, unsuccessfully – and then just sat back silently looking at him as he reached the arms of his grandfather. Her eyes were full of deprivation and sorrow. It was heartbreaking to look at.

She started talking to the husband again and to her sister who was sitting next to the widower. The sister was very upset, crying and constantly asking why she left so early, what they should do without her. She was explaining that she had so much pain in her head (apparently, she had been bedridden for months before her death) and that she couldn’t cope with it any longer, so she had had to let go. She was begging the husband and sister to promise to take care of the little boy. This went on for a long time. The shaman was crying the whole time.

And then all of a sudden the shaman got calmer and looked around the room at all the faces that were surrounding her: familiar faces of family members and neighbours. She smiled at each one of them and put her hands together in a suksma (thank you). When her gaze reached my husband and me her eyes stopped, and with a surprised smile she said: I remember you! I am very happy to see you here – thank you for coming. And she added: sorry I could never speak with you; my English is very bad. (the young woman had worked at our friends’ homestay for years and we had indeed met on several occasions, not being able to speak due to language barriers).

Before leaving the shaman’s body the young woman once again reached in the direction of her child and started crying. It was almost unbearable.

I cannot explain what happened. But it was real.

***

The featured photo that beautifies this article is a painting by my amazing friend artist Lydia Janssen

Lydia Janssen, The Ride, 2021

Lydia Janssen, The Ride, 2021

December 6, 2021

Uncultivated: You have to work hard

As previously mentioned, I am in the process of writing a new book with the working title Uncultivated. The book is built up around negations of “the ten commandments of cultivation”. The intention herewith is to jeopardize taken-for-granted cultural and societal “truths” in order to encourage rewilding.

We have to adapt and behaveWe are superior to animalsWe are separated from natureWe must be ambitiousWe have to work hardWhat cannot be explained is not trueWe do not talk about deathDecay must be defeatedTime is linearGod is deadIn this post I share an extract from the section: You have to work hard. In forthcoming posts I will share selections from other sections of the book (next up is: What cannot be explained is not true). Feedback is much appreciated!

***

You have to work hardI want to be a chef or a drummer or a runner or an artist or an animal caretaker, when I grow up, he says. It is hard to choose though, because I am good at so many things.“

“Being good at something requires hard work.” I am brought up with this sentence. I am nearly unable to think differently. And, as much as I absolutely love when my youngest son makes a statement like the above quoted, I can also feel that it triggers my basic assumptions, and that I deep down inside think: you cannot say stuff like that! Saying something like that is being big-headed, boasty, pretentious…!

But the thing is; when my 8-year old says that he is good at so many things, he is being anything but pretentious. He is being pure and uncultivated, honest and straightforward. He doesn’t yet know that you are not allowed to make a statement like that; that it is considered arrogant or inappropriate. He just feels that the world is open to him; that he could do anything he is passionate about, and that there are so many things he loves to do. Furthermore, he is filled up by the feeling that loving to do something makes you effortlessly good at it. This feeling is very motivating! And, it is very possibly true. I am writing this cautiously, because it is so unaligned with what my culture’s voice preaches.

My culture says: you have to learn lots of things you aren’t interested in and don’t love doing. This is important, because not everything can be fun and enjoyable. It just can’t! You have to work hard and do lots of stuff you don’t enjoy in order to succeed and become a good, civilized, cultivated human being.

My son says: I enjoy doing so many things, and I am good at them too; why shouldn’t I do those? Why should I do things I don’t like to do?

My culture says: everybody has to learn more or less the same things, whether they like these or not. This is important, because we have standards and procedures that have to be followed, and these have to be the same for everybody.

My son says: some of my friends are really good at yoga and at writing beautiful letters and at dancing and at reading aloud from text books. I am not, but I am really good at running and jumping and drawing and cooking; this is perfect because it would be really boring if we were all good at the same things.

“There is no one right way to live”, says Ishmael (in Daniel Quinn’s “Ishmael”) – and I am sure my son would agree.

My son and his friend going for an evening swim in North Bali.

My son and his friend going for an evening swim in North Bali.

November 29, 2021

Interview #11: Bio-designer and Artist Zena Holloway

I stumbled upon Zena Holloway‘s amazing work recently in an article in Luxiders Magazine. I was blown away by the idea of growing clothes! And, as I started looking more into Zena’s projects I knew I had to contact her to learn more and do an interview with her for The Immaterialist.

Zena uses nature as a 3D-printer by growing grass-roots in moulds made from beeswax. The roots can form both hardwearing and light, lacey structures depending on the patterns they are grown in, which opens for an wide array of opportunities. Imagine growing clothes or other design-objects for that matter, perhaps also packaging, from grass-roots! It could be a way of legitimising disposability or a sustainable way of working with short-lived products. And, it could also be a way of altering the current consensus on object longevity being interlinked with materials that are basically imperishable.

Please enjoy reading about Zena’s visionary thoughts and grass-root approach to wearable design.

***

What does sustainability mean to you?For me it’s about shifting the collective conscious towards a circular economy.

We need to learn to be smart about the way we use resources and accelerate green innovation so that materials can be used again and again. We need to shift towards more sustainable ways of living because the current linear model, that exploits the Earth, has an expiry date.

***

How did you get started growing wearables and sculptures?I first went diving in the 90’s. I was lucky enough to work in the Red Sea and the Caribbean when the coral was still alive and there was much to see. Rather like fishermen with stories of huge fish they’ve caught, divers speak about the creatures and sights they’ve seen underwater. The old divers described seeing nests of nurse sharks, flocks of turtles and coral reefs that were boiling over with fish.

Sadly, in the times we live, much of that is gone and what is left is dying. The reefs make up less than 0.1% of the surface area of the ocean and support a quarter of all marine creatures, but the coral is bleaching and dying at an alarming rate. It was this, as well as the problem of single use plastics in our oceans that got me interested in bio-design.

I wanted to search for solutions. I began by growing mycelium in my basement, harvesting mushrooms for the dinner table, and looking at how I could grow materials to replace plastics. I started from ground zero, bought a few books, researched online, and loved the idea that whatever I made would eventually end up on the compost heap and not in landfill.

Whilst my adventures into mycelium weren’t particularly productive it made me look at materials in a new way and when I came across willow root, growing underwater in my local river, I became interested in its binding qualities. It seemed root had similarities to mycelium, and I wondered if I could grow textiles or materials with it.

I’ve been growing root for about three years now and I still feel I’m just on the first step of a very long ladder of possibilities.

***

Tell about the process of growing clothes. What is your vision?Early on it struck me that the white roots of grass seed have similar properties to coral. They both branch out into connected, living networks that are the building blocks for the natural world. Playing with this concept, I purposefully guide the root into shapes and textures resembling coral – it’s my way of bringing the conversation back to ocean conservation, bio-diversity loss and the climate crisis.

I’ve learnt how to keep the root soft and supple, as well as make it rigid enough to support its own weight. Different patterns have different properties, some become light and lacey, whilst others grow more thickly into stronger pieces.

The joy of this project is that I’m straddling a wide range of disciplines from botany to mould-making, material innovation to fine art, chemistry to fashion – and just teaching myself as I go along.

At this stage I’m still researching root as a viable, sustainable fabric for clothing, and I think its future is bright.

***

What do you view as the biggest environmental problem?Carbon. The scary thing is we haven’t even managed to bend the curve on our emissions yet. It’s still pouring out, increasing temperatures, causing extreme weather patterns, melting glacial ice, raising sea-levels, killing coral, turning the oceans acidic etc.

We know what we need to do, we just need to push policy makers to accelerate carbon drawdown at full speed because the consequences of not doing it fast enough don’t bear thinking about.

November 17, 2021

What does sustainability mean?

This article is based on an opening passage in the last chapter of my new book Anti-trend (which will be published very soon and is available for preorder now).

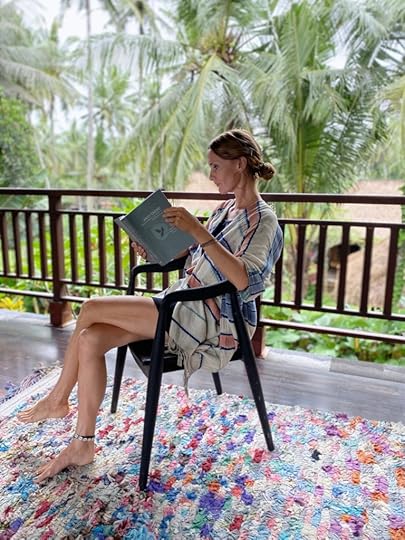

A loved one reading the first printed edition of Anti-trend at Rüsters Coffee in Ubud, Bali

A loved one reading the first printed edition of Anti-trend at Rüsters Coffee in Ubud, BaliI am often met with the question of what the most sustainable design-object or the most sustainable way of life looks like, feels like, is like? And, my answer mostly goes somewhat like this: a sustainable design-object encourages reduction of consumption by offering longevity, repairability, openness, and rawness, and aligned herewith, sustainable living involves minimizing consumption and maximizing aesthetically nourishing, enduring rhythms.

The more elaborate answer sounds like this:

One of the main problems with the way we are currently consuming, which is excessive and gratuitous, is the way the things we consume are designed and the amount of waste produced. What is needed is fundamental change; a radical reduction of consumption since the overconsumption of things that are quickly perceived as obsolete, despite them being made out of long-lasting materials is what has led us to where we are now. We need to practice a lifestyle that is not only slightly, but al lot greener. We need to pursue alternatives to the status quo rather than convulsively hold on to what we are used to and familiar with. Our current codes of conduct, status symbols, and behavioral patterns in relation to consumption are outdated and guilty of destroying our ecosystems and draining our natural resources. They are, as previously discussed, guilty of leading to despair, oppression, and increased inequality between populaces

Instead of returning our castoff clothes to fashion-stores in order to receive vouchers to purchase new rags we should reduce our clothing consumption radically. Instead of applauding people’s economic ability to buy yet another updated version of a perfectly fine object we should praise the beauty of well-made, long-lasting, well-functioning artefacts and creative mends. And instead of craving and demanding an even flow of new, flashy products made of virgin materials we should request products that encourage sustainable living by being made of recycled materials, that are upcycled from discarded products, or are made to be swapped or shared or to sustainably deteriorate.

Metaphorically speaking, what we are doing right now is like insisting on building a tropical waterpark in a desert, even though this is obviously immensely straining on the natural resources available, and despite the fact that it goes against the physical qualities and local resources of a desert. We will not accept and respect natural limitations, and we generally refuse to be restricted by lack of resources and local reserves. Deserts are a particularly good metaphor in this case because they appear to be useless to human beings. But despite a desert’s seeming uselessness in relation to the livelihood of humans, deserts are vitally important to the earth’s ecosystem, just as the artic sea pack is and just as rainforests are.

Furthermore, if usefulness is a focal point, making use of desert land for harvesting solar energy or minerals rather than for constructions that are better fitted elsewhere should be the way forward. A good example of naturally sustainable usage of land is the rice fields in Bali that most typically are built on hills, ridges, or mountainsides that naturally have springs running through them or water running down from elevated lakes or streams—natural irrigation. This is a prime case of understanding and respecting a landscape or “listening to its soul” and its natural flow before farming it, creating constructions on it, or in other ways altering it to make it inhabitable or “useful” to human beings.

When it comes to sustainable design solutions and sustainable living, a similar perspective is needed. We need to make use of land that has natural springs running through them to farm rice—symbolically speaking. The direction we are headed right now is leading us to proprietary obesity: it seems that we continuously over consume and then feel weighed down by our belongings, which forces us go on a diet. We tidy up—we might even hire experts to help us do this—we throw a bunch of stuff away, we cherish minimal living for a while, only to find ourselves “overeating” soon again. All the alluring and very affordable offers are apparently just too tempting. The sudden bursts of minimalistic needs are apparently not sustainable, maintainable, or satisfying.

The current consensus appears to be that improvements and progress are the equivalent of making things more comfortable, smoother, and more convenient by minimizing friction and heaviness. However, design improvements could and should ideally mean something entirely different. Improvements should increase the tactile experience and foster a tangible bond between object and owner. They should challenge the user’s senses and mind and induce more heaviness, in the most nourishing sense of this term. They should encourage the user to repair and maintain an object or perhaps even to share it with others. Or they should activate the user and engage her or him in communal or sustainable actions.

Aesthetically sustainable Boro rug by MITSUGU SASAKI

Aesthetically sustainable Boro rug by MITSUGU SASAKI Before designing yet another slightly better, slightly more convenient, slightly more streamlined, slightly easier to use version of a phone, a chair, a jacket, or a bowl for that matter, the sustainable designer should question the very inclination for this task, by asking the following question: What can legitimize designing something new? Are minor improvements or increased convenience a good enough reason?

Can you, literally and metaphorically speaking, legitimize replacing your entire kitchen because you want new cupboards that don’t make any noise when you close them, and because you cannot solely change the cupboards, since the other kitchen elements won’t mix and match? The new countertop has to have a skinnier, smoother surface than your old one. Can that in any way be an appropriate reason to improve one’s belongings in a world with scarce resources? Does today’s common consumer really need more convenience? And, is the transition to smart everything and focusing on accessibility and user-friendliness above all really necessary?