Kristine H. Harper's Blog, page 5

October 13, 2022

An antidote to sustainable luxury

Living sustainably should be the most reasonable and the most natural way of life. Mending, reusing, recycling, sharing, and eating local groceries are all examples of activities that are at the core of sustainable living, and that are also affordable, unpretentious, and accessible. So why is sustainability often associated with luxury, elitisms, and exclusivity? Why has sustainable design and sustainable living become a status symbols and ways of expressing wealth and sophistication?

Looking back in history at traditional ways of life, basic approaches to sustainable living are countless: prolonging the life of things, repairing, reinforcing, preserving, conserving, communally consuming, sharing, crafting, gardening, locally sourcing, composting, following the cycles of nature and seasons, etc. Such activities and ways of life are exactly what are celebrated as a part of the simple living tendency, which means that there is a growing tendency of engaging in and celebrating democratic, communal, unpretentious sustainability.

However, despite repairing, reusing, and recycling being both affordable and accessible ways of life and approaches to consumption, they don’t seem to be common. As a matter of fact, the least well-off seem to be the least engaged in such sustainable and affordable activities. Why? Well, in order to be able to repair and mend one’s belongings, these belongings must be repairable! And, generally cheap, mass-produced goods aren’t. They are produced to be obsolete after a short period of usage. Fast-fashion products are generally made from composite and/or artificial materials that cannot be patched or mended in a way that doesn’t leave unflattering spots on the fabric surface, and they, per definition, adhere to fleeting trends, which make them appear outmoded after a short period of time.

Similarly, cheap toys, home accessories, kitchen utensils, etc., wear out and get damaged in ways that make them hard or maybe even impossible to mend. They are made from flimsy materials that break easily, and they are cheaper to replace than to repair. Aligned herewith, the cheapest foods are mass-produced fast foods, and are typically wrapped in plastic and Styrofoam, produced to be homogeneous and bland in large food factories and often transported across the world. They are obviously not the most sustainable products, without even getting into the health hazards that they represent, the animal cruelty to produce, or the unethical, oppressive work conditions that are involved in the production.

Beautiful foodporn at Stedsans in Sweden. Slow well-made, simple, unpretentious; a recipe for democratic sustainability

Beautiful foodporn at Stedsans in Sweden. Slow well-made, simple, unpretentious; a recipe for democratic sustainabilitySustainable design-objects and ecological, sustainable foods are created and produced to be expensive. They are made and branded to be yet another traditional status symbol, yet another way to express wealth. Even though living sustainably should and could be the most reasonable and natural way of life, it is out of reach for the majority of people. Sustainability has become pretentious, elitist, and for those who are fortunate, well-off, and well-informed, and those who tend to increase the division between sustainable and unsustainable living by sitting “on their high horses” pointing fingers. Sustainability has become a way to separate social classes. It is an extremely effective example of storytelling that profits from self-righteousness and class-divisions, creating an us versus them mentality. There is no community feeling in luxurious sustainability.

But do sustainable things really have to be expensive and pretentious? Of course, designing durable, long-lasting objects tends to require thoroughness and time-consuming research; and of course the creators of sustainable solutions have to be paid for their efforts, and the manufacturers and workers should receive fair salaries.

However, designing for a long life might not be the only way to create a sustainable thing. The sustainable short-lived object represents a different approach to sustainable design by celebrating change, transience, and impermanence. Designing short-lived sustainable objects produced to deteriorate naturally can be a sustainable kind of planned obsolescence.

Amazing green tiles at Le Jardin Restaurant in Marrakech – these imperfect raw beauties will surely decay aesthetically

Amazing green tiles at Le Jardin Restaurant in Marrakech – these imperfect raw beauties will surely decay aestheticallyThere is a plethora of inspirational examples of sustainable living in the past that are affordable and straight forward. The raw and open design-object is created to encourage such ways of sustainable living. It is repairable, flexible, and embraces the user’s needs and preferences—and in that sense it is upgradable. The raw and open design-object is unpretentious and modest in the sense that it isn’t—at its starting point—flashy; it might not even look like much, because it represents a nearly blank canvas to be filled by the user. It is the user who makes it unique and shapes its aesthetics—its look, feel, ambience—simply by using it, perhaps by decorating it, by allowing for the traces of usage to manifest on it, and by maintaining and mending it. The open and raw design-object falls into the category of long-lived design-objects, but its durability is not initially linked to loud aesthetics or challenging compositions. It typically has a very simple, neutral appearance, because its initial look and ambiance should allow for the user to put their mark on it and affect its look. The raw design-object might develop from having a neutral, modest, and simple expression to being loud, flamboyant, and colourful depending on the user’s preferences and stories.

The open and raw design-object should have a broad appeal. Designing with openness and inclusiveness in mind is a way of aiming for broad applicability and relevance, which means that as many people as possible, regardless of cultural background and capital or habits, feel intrigued by the object. Opening up the design-object is a way of “loosening it up” by generalising and allowing whoever purchases it and uses it to shape and influence it.

The narrative of the open, raw design object is created through usage, and thereby it isn’t pre-made in the shape of delicious, seductive sustainable storytelling. It arises from the post-creation phase. It contains a great deal of time; the time spent molding, wearing, changing, or mending inherent changes that unfold.

The open, raw design-object is charged with the time of usage, and as such it is ever-changing.

***

Read much more about openness, rawness, and democratic, short-lived sustainability in my new book Anti-trend – in particular in Chapter 5 of the book: Three Anti-trendy Reasons for Designing New Objects in a World With Way too Many Things

October 4, 2022

Anti-trendy design: a hymn to rawness, flexibility and repairability

This post consists of an extract from my book Anti-trend. It is taken from the last chapter in the book; a chapter dedicated to investigating the characteristics of the anti-trendy design-object.

***

The Anti-trendy Design-objectOne of the major realizations that I have made throughout the research for and the writing of this book is that the number one obstacle when it comes to eliminating over-consumption and the pollution and oppression that follows in the wake is a combination of our cultural and societal norms and trends influenced by capitalism and the credulous praise of growth—and in part that our idea of the good life seems to be interlinked with consumption: consumption of luxurious food and drink, exotic holidays, fancy cars, and of a continuous stream of new clothes, gadgets, and entertainment.

Naming this book Anti-trend, which initially was just meant as a working title due to the fact that I was concerned it might hold too many fashion-connotations to carry the entire project, has turned out to be an apt descriptor during the whole process of book-writing. Trends are interlinked with the ever-changing status-symbols and norms that are intertwined with consumerism. Anti-trends are the antitheses. Trends and the fleeting stream of whatever is vogue, and the longing for trendy, alluring products, is one of the chief offenders to combat when it comes to reduction of consumption in the name of sustainable development. The other one is habits; our routines that keep us stuck in a pattern of over-consumption and make us reluctant to change, even if the change is meaningful and beneficial for us and our community as well as our human-made and natural environment. An alternative is needed. We are in need of more anti-trendy, resilient product solutions that include a larger degree of user-flexibility, and of objects that are designed to be open to change. In order to alter our cultural and societal norms, more sustainably innovative product solutions are compulsory. In order for the supply or creation of sustainable design solutions that encourage resilient living to raise, the demand for resilient, sustainable products must increase, and vice versa. The creation of sustainable solutions and the need are interlinked. One cannot look at one side of this equation without looking at the other one as well.

Anti-trend is not synonymous with immovability and stagnation, even though it could appear to be since trends are associated with newness and change. Anti-trendy objects are intertwined with flexibility and alteration.

In the below table the differences between anti-trendy and trendy design-objects are compared side by side:

The anti-trendy design objectThe trendy design-object ResilientFleetingLong-lived or short-lived (permanence or sustainable planned obsolescence) Perceived as obsolete after a short period of usage (despite being made from materials that can last for a long time)HeavyLightAlterable, adaptable, in flowStaticFlexibleFixedRepairable, mendableUn-repairableRaw, imperfectSmoothOpen, ever evolvingClosedRegrowth and degrowthExponential growth followed by rapid declinationUnderdone (usage “finishes” it)Declines or worsens when usedCircular, iterativeLinearChallenging expressions or functionalities (might offer new ways of life or nudge the user to alter habits)Convenience (easily understandable, usable, and decodable)Uneven, variated textures (tactilely nourishing)Picture perfect (even the slightest blemish ruins its appearance)DiverseHomogeneousEncourages wholesome rhythmsPraises newnessEmbraces and celebrates decayDecay makes it obsoleteUpcycled or craftedMade from virgin materialsSharableMade to be consumed (and replaced)Cherishes innovation (made to encourage sustainable living)Conventional (made to “fit in”)Challenges conventional status symbolsMade to be admired by peersFriction, texturesqueEvenness, “glittery” surfacesAs the table shows, the anti-trendy design-object is characterized by being flexible, alterable, and repairable. But it is also interlinked with more abstract characteristics such as heaviness and rawness. These features are entwined with the friction and openness of the anti-trendy object, as they revolve around an object’s ability to nourish the receiver’s senses by introducing a degree of “graininess” or coarseness to the daily life; they are not easily or quickly digestible or consumable and require time to consume.

The anti-trendy design-object is underdone in the sense that when it is released into the world by the designer it is not yet finished. Usage finishes it, as the object is created to develop and to embrace change and decay. The anti-trendy design-object is characterized by gently nudging the user toward sustainable living; whether that means inviting more textural stimulation into life by investing in handcrafted artefacts that are anti-smooth or texturesque, engaging in nourishing daily rhythms that can provide life with a sense of direction and with the beauty of continuity and perseverance, or by allowing for more rawness, inconvenience, and heaviness in life in order to escape the despair and the dullness that follows detachment from nature and a life in a homogeneous physical—and cultural—environment.

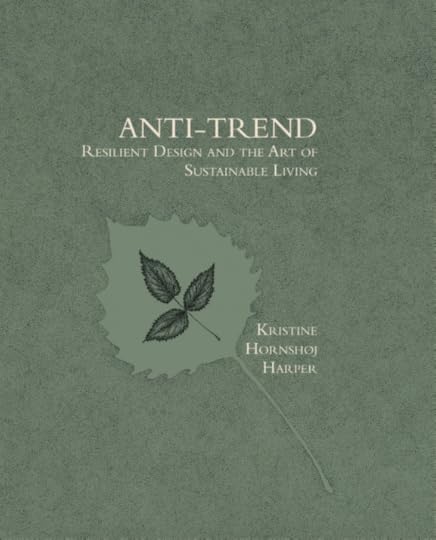

Flexibility moodboard from my recent anti-trend report made in collaboration with Pej Gruppen: Scandinavian Trend Institute

Flexibility moodboard from my recent anti-trend report made in collaboration with Pej Gruppen: Scandinavian Trend InstituteThe trendy design-object is made to develop from being new, shiny, and attractive at its peak—when it is brand-new and freshly acquired by the consumer—to slowly, or perhaps very quickly, being experienced as unattractive and obsolete. That is the mechanism that makes the wheels of consumption spin.

The trendy design-object is linear: it moves from a starting point to an endpoint, and this development is designed to be a downgrade. A trendy dress, pair of shoes, piece of furniture or toy is premeditated to be consumed—to have all its nutrients sucked out of it and provide the user with a quick burst of energy, and then to be discarded or expelled. As an antithesis, the anti-trendy design-object has a circular or, maybe even more accurately, an iterative lifespan. Using the term iterative rather than circular is done to emphasize the anti-trendy design-object’s inherent ability to develop, as well as the fact that despite anti-trendy development involving continuous aesthetic nourishment, it doesn’t necessarily implicate a movement back to its starting point. It might in some cases, but not always. In the section “Waste Materials, Deconstruction, and Upcycling” in Chapter Five I discussed different ways of embracing decay and traces of usage in a design-object, one of them being “wiping the slate clean” or returning to a default state. The example from the mentioned section includes furniture made from plastic waste characterized by a hardiness that makes it extremely durable and robust, and furthermore makes it possible to sand away scratches and other traces from usage and continuously remove blemishes in order to keep the original look and style. This particular development can be described as circular; it repeatedly returns the object to its starting point because the object is designed to rejuvenate.

Rawness moodboard from same anti-trend report

Rawness moodboard from same anti-trend reportHowever, in most other cases, the anti-trendy design-object develops in a more iterative way. An iterative process involves doing something again and again, usually to improve it. This is exactly what happens when the anti-trendy object is being used. The more the object is used, the better it becomes. It matures and develops, supporting the functional and aesthetic needs of the user. The anti-trendy design-object is created to be long-lived and is underdone when released into the world. Usage molds it, refines it, and gives it character. Iterative refinement involves the modification and enhancement of the object; the anti-trendy object is made to be used, touched, timeworn, shared, modified, repaired, adjusted, decorated, personalized, and altered.

September 19, 2022

Whatever Lasts: Ongoing conversation with Isabelle McAllister

Remember being a child or a teenager and having a pen pal? Remember engaging in a letter exchange (as in a handwritten, pen on paper kind of letter exchange) with someone from another part of the world or from another part of your country, and experiencing the excitement of receiving letters with colourful stamps decorating the envelopes and sheets of handwritten paper (maybe embellished with small drawings and maybe with photos enclosed)?

Perhaps you are not as old as me, and perhaps such pen pals are a blast from the past, but I sure remember my childhood pen pals. For years I exchanged letters with a boy from Seoul, Korea. I was matched up with him by my teacher, and we wrote long letters to each-other in English (about what I don’t remember exactly, but probably about our lives and cultural differences) and we exchanged photos. An then suddenly it stopped. I wonder what happened to him?

I also had a pen pal from southern Denmark (a girl from a small town called Vojens; I can’t believe I actually remember that, because I don’t remember her name). We were also paired by our teachers, and encourage to engage in a written, ongoing conversation, and we too wrote letters for years, exchanged photos and even met a few times. I forgot why we stopped our conversation, but sitting in my room listening to music and writing those letters is a fond memory of mine, and receiving responses from her even fonder.

The slowness of that kind of conversation holds a distinctive beauty. The beauty of anticipation, of not knowing when the answer will arrive (and what the answer will hold), and of course the letter-writing process itself. I recall the satisfaction of folding my handwritten pages, and perhaps adding small drawings, a photo, clippings from a magazine or maybe a dried flower, and then closing and sealing the envelope and writing the address of my receiver in my neatest letters (not the easiest task for me; my handwriting has always been messy and big).

Anyway, before getting totally lost in sentimentalising my past letter-writing adventures, let’s move to the actual topic of this post: my new conversational project Whatever Lasts with my friend Isabelle McAllister.

I met Isabelle back in 2018, when we both moved to Bali with our families. We quickly discovered that we share a passion for a bunch of things, like wearing our clothes for as long as possible (at times beyond a point of embarrassing shabbiness) – and repairing them in fun ways, if possible – reading books on sustainable living as well as philosophical novels, listening to podcasts on anything from cultural dogmas to sustainable solutions and new technology, slow living and (barefooted) nature romanticism, and uncultivated, rewilded living and education.

Around half a year ago Isabelle and I started a written conversation. Not handwritten, but a dialogue in the shape of emails (which according to my teenage son is almost an as ancient form of communication as actual letter writing).

We started our email-correspondence much like a classic pen-pal thing – except we already know each other, of course. But besides from that, pretty pen-palish in the sense that we agreed to engage in good old-fashioned written communication: longer than text messages and no voice-memos. And, in the sense that the conversation takes place from two far-apart places: Stockholm, Sweden and Bali, Indonesia.

I was excited about this conversation from the beginning, because there is nothing like a good discussion about topics that you are deeply engaged in. Especially when your discussion partner, like Isabelle, is a master at leading you to new angles on these topics and guiding you to look into a bunch of inspiring articles/podcasts/books. And, I have already received so many fun, thought-provoking, intriguing responses from her that I am feeling that good old pen pal thrill: when will the next letter arrive in my inbox?

Recently we decided to start posting our correspondence on Instagram. Mainly due to the fact that our communication quickly started evolving into a culture-critical, anti-capitalistic, nature-romanticising debate that we are longing to get others’ input on. Because, honestly, we agree so much on these topics that a healthy dose of critique might do the discussion some good.

So, we hope you will join us in this ongoing written communication that we have decided to call Whatever Lasts. The beauty of it now taking place on social media is also that is has allowed for us to add photos and videoclips to our letters (which makes it feel almost like my bygone pen pal letters with enclosed magazine clippings, photos and dried flowers).

Whatever Lasts

Remember being a child or a teenager and having a pen pal? Remember engaging in a letter exchange (as in a handwritten, pen on paper kind of letter exchange) with someone from another part of the world or from another part of your country, and experiencing the excitement of receiving letters with colourful stamps decorating the envelopes and sheets of handwritten paper (maybe embellished with small drawings and maybe with photos enclosed)?

Perhaps you are not as old as me, and perhaps such pen pals are a blast from the past, but I sure remember my childhood pen pals. For years I exchanged letters with a boy from Seoul, Korea. I was matched up with him by my teacher, and we wrote long letters to each-other in English (about what I don’t remember exactly, but probably about our lives and cultural differences) and we exchanged photos. An then suddenly it stopped. I wonder what happened to him?

I also had a pen pal from southern Denmark (a girl from a small town called Vojens; I can’t believe I actually remember that, because I don’t remember her name). We were also paired by our teachers, and encourage to engage in a written, ongoing conversation, and we too wrote letters for years, exchanged photos and even met a few times. I forgot why we stopped our conversation, but sitting in my room listening to music and writing those letters is a fond memory of mine, and receiving responses from her even fonder.

The slowness of that kind of conversation holds a distinctive beauty. The beauty of anticipation, of not knowing when the answer will arrive (and what the answer will hold), and of course the letter-writing process itself. I recall the satisfaction of folding my handwritten pages, and perhaps adding small drawings, a photo, clippings from a magazine or maybe a dried flower, and then closing and sealing the envelope and writing the address of my receiver in my neatest letters (not the easiest task for me; my handwriting has always been messy and big).

Anyway, before getting totally lost in sentimentalising my past letter-writing adventures, let’s move to the actual topic of this post: my new conversational project Whatever Lasts with my friend Isabelle McAllister.

I met Isabelle back in 2018, when we both moved to Bali with our families. We quickly discovered that we share a passion for a bunch of things, like wearing our clothes for as long as possible (at times beyond a point of embarrassing shabbiness) – and repairing them in fun ways, if possible – reading books on sustainable living as well as philosophical novels, listening to podcasts on anything from cultural dogmas to sustainable solutions and new technology, slow living and (barefooted) nature romanticism, and uncultivated, rewilded living and education.

Around half a year ago Isabelle and I started a written conversation. Not handwritten, but a dialogue in the shape of emails (which according to my teenage son is almost an as ancient form of communication as actual letter writing).

We started our email-correspondence much like a classic pen-pal thing – except we already know each other, of course. But besides from that, pretty pen-palish in the sense that we agreed to engage in good old-fashioned written communication: longer than text messages and no voice-memos. And, in the sense that the conversation takes place from two far-apart places: Stockholm, Sweden and Bali, Indonesia.

I was excited about this conversation from the beginning, because there is nothing like a good discussion about topics that you are deeply engaged in. Especially when your discussion partner, like Isabelle, is a master at leading you to new angles on these topics and guiding you to look into a bunch of inspiring articles/podcasts/books. And, I have already received so many fun, thought-provoking, intriguing responses from her that I am feeling that good old pen pal thrill: when will the next letter arrive in my inbox?

Recently we decided to start posting our correspondence on Instagram. Mainly due to the fact that our communication quickly started evolving into a culture-critical, anti-capitalistic, nature-romanticising debate that we are longing to get others’ input on. Because, honestly, we agree so much on these topics that a healthy dose of critique might do the discussion some good.

So, we hope you will join us in this ongoing written communication that we have decided to call Whatever Lasts. The beauty of it now taking place on social media is also that is has allowed for us to add photos and videoclips to our letters (which makes it feel almost like my bygone pen pal letters with enclosed magazine clippings, photos and dried flowers).

September 1, 2022

An ode to being bored

In Danish Philosopher Søren Kierkegaard’s (1813–1855) seminal work Either-Or, Kierkegaard introduces a personality-type that he calls “the Aesthete.” The Aesthete is characterized by living in the now and constantly seeking pleasurable, easy-going experiences. The aesthetic approach to life is hedonistic, lust-based, founded on momentary desires, and hence the life of the Aesthete lacks continuity and stability: it is built up around short glittery moments that are not linked together, but rather disjointed like marbles in a box.

The Aesthete is governed by an extreme focus on excitement and pleasure, as s/he views boredom and triviality as the root to all evil. This pleasure-seeking venture leads to a life directed by questions like: What do I want to experience, enjoy, eat, purchase next?

However, even though the Aesthete might— on the surface—appear happy and fortunate, s/he is not an authentic person. The Aesthete is, according to Kierkegaard, always absent to the self and never present, despite his/her constant hunt for momentary here-and-now experiences. The content of life, the fullness of consciousness, and the essence of being is, so to speak, located outside oneself. Happiness is solely based on external stimuli.

Welcoming slowness into one’s life can be a way of overcoming the restless pleasure-seeking venture that characterises the aesthetician stage. Photo from my recent anti-trend report.

If one is governed by the idea that pleasure requires novelty, like the Aesthete is, the enjoyment of consumption is per definition finite. The restlessness of late-modern society—in which innovation, newness, disruption, and changeability are buzz-words—resembles the restlessness of the aesthetician stage. The relief from boredom is only fleeting. The Aesthete is occupied with getting as many interesting, pleasurable experiences as possible: with feeling good or having a good time, again and again. If the Aesthete for example gives money to charity, it is because it makes her or him feel good. The Aesthete is always controlled and steered by pleasure. What do I feel like doing? What will make me feel better? These questions are the steering wheel in the life of the Aesthete—but actually they are also very applicable contemporary societal guiding principles. We are essentially often encouraged—by experience-focused self-help books and adverts—to live our lives in accordance with the Aesthete; to spoil ourselves and indulge in comfort-providing spa-, travel-, dining-, or consumer-experiences. To flee boredom by all means. To live here and now and to spend money on whatever takes our fancy, without thinking about tomorrow.

Our late-modern cultural assumptions on “the good life” sends us out into the world with the mantra, “If it feels good, it is good.” Even children are taught from an early age, due to the absurd number of daily hours they spend in front of tablets, smart-phones, computers, and game consoles, that you don’t have to make an effort to learn anything, and that you never have to be bored. You very quickly excel in a computer game, and if you don’t, you can just delete it and find another one that matches your abilities better and that gives you a more pleasurable “here and now” experience. Children are taught to constantly seek pleasure: to build up their daily routine around a pleasure hunt of “shiny” moments that are not unlike that of the Aesthete’s.

The aesthetician stage is characterized by a lack of over-individual standards. The Aesthete focuses solely on fulfilling experiences, pleasure, and personal well-being—not unlike the contemporary narcissistic need to exhibit every single step one takes, every fancy outfit one buys, and every healthy and/or delicious meal one consumes (and every nice cup of coffee one drinks, like me in the below photo) on social media. Actually, I am convinced that Kierkegaard would agree that the Aesthete loves social media. I couldn’t imagine a better and easier way to create a self-composed poetic distance to everything and everyone.

However, a pleasure-hunting experience-based life is not an authentically fulfilling life according to Kierkegaard. We need to make meaningful choices and to commit ourselves to something and someone in order to live authentically. Yet, in our post-factual, post-religious, post-common-ground reality, in which neither authorities nor experts nor gods nor communities are providing us with valid guidelines or normative standards and values, we tend to be led by our aesthetician need for entertainment or at least momentarily satisfying experiences, or by our need to fit in. The problem with that is that our experience-hunt is controlled by our quickly changeable preferences led by trends; and trends are volatile, unstable, and constantly shifting.

We must find an alternative to the authorities and gods that we have killed. An alternative that makes us able to differentiate right from wrong. An alternative that can create new stability in an unsettled, aesthetician world. I am not saying that the doctrine of religion or authoritarianism is the sole way of creating a standpoint on which one can build an authentic life. But nevertheless, a standpoint is crucial in order to form a nourishing, stable counterpoint to abrupt experience and pleasure-hunts.

Read much more about the enduring relevance of existential philosophy and the relation to sustainable living in my book Anti-trend.

August 22, 2022

The core of sustainable living

This post contains extracta from my book Anti-trend. They are taken from the beginning of Chapter 2: Anti-trendy Intuition as well as from the subsection in the same chapter with the subtitle The Core of Sustainable Living.

I have recently on several occasions been reminded of exactly how important it is to be able to make use of my intuitive compass; Intuition can be grounding—and rather than being subjective it can be a gateway to understanding intersubjective elements and basic assumptions. Intuition links us to universal themes that are relevant and common to all human beings, cross culturally.

Anti-trendy intuition

Anti-trendy intuitionBeing intuitive and using one’s intuition to navigate and draw conclusions is generally an unwelcome methodology when performing theoretical research. Intuition is viewed as superficial, unserious, and overly subjective. But perhaps closing ourselves off to intuition denies us straightforward insights.

In this chapter, seemingly intangible concepts and methods like the intuitive compass, intersubjectivity, eidetic reduction, and sublimity will be investigated with the overall purpose of moving toward an understanding of what it means to adhere to anti-trendy tendencies, in the creation of design-objects, and in life in general.

The present usage of the term intuition is closely interrelated with phenomenological research. To intuitively grasp something, for example societal and cultural tendencies, involves moving from observations and hunches to an innate understanding of contexts, conditions, and connections. And, to gain intuitive insight into objects or environments can be described as a way of “checking in” to our fundamental human attachment to our physical surroundings—which appears to be lost when we feel detached from nature, from materials and textures, from sensations and atmospheres, and start doubting our sensory, bodily wisdom.

My hypothesis is that this kind of detachment causes unsustainable behavior, which materializes in a use-and-throw-away mentality, because, simply put, if we don’t feel connected to our physical surroundings, we are less inclined to take care of and maintain them. Hence, exercising one’s intuition is a vital part of both the sustainable design practice and sustainable living.

When consumers become increasingly intuitively and sensuously aware, they demand products that can nourish that awareness within them, and when designers are able to tune into their intuitive compass their ability to create resilient, anti-trendy design-objects that meet deeply felt consumer needs (rather than fleeting trend-based ones) increases. And hence, we are back at the inherent supply-demand logic of the book: namely that in order for the supply of sustainable, resilient design solutions that encourage sustainable living to raise the demand for such must increase, and vice versa.

In the following sections we will move from clarifying the connection between intuition and phenomenological research, investigating ways of disrupting the familiar with the purpose of seeing through “taken for granted truths” and thus potentially altering unfortunate behavioral patterns, and, finally, exploring ways to learn how to navigate intuitively in life and the creative process.

(…)

Drawing conclusions based on intuition is not the equivalent of basing every part of a decision-making process on subtle feelings or emotions. In secularized, and highly rational parts of the word, intuition is often associated with irrational feelings, superstition, and/or worthless gut-feelings, and hence linked to non-valid resolutions.

In my approach to working with the intuitive compass, however, intuition is not necessarily anti-rational nor is it fruitless or void due to its subjective character. Intuition can be grounding—and rather than being subjective it can be a gateway to understanding intersubjective elements and basic assumptions. Intuition links us to universal themes that are relevant and common to all human beings, cross culturally. Intuition is, or should be, the last or perhaps the first drop when making decisions regarding the creation of long-lasting objects, or when concluding upon societal, cultural behavioral patterns. In other words, when gathering insight into tendencies or predominant lifestyles of a time (in order to support or challenge these by creating anti-trendy, sustainable design-objects), making use of one’s intuitive compass can be the highly beneficial. In the following subsections, I will demonstrate how this can be done based on an investigation and definition of the concepts of phenomenological intuition, eidetic reduction, and intersubjectivity.

It might sound slightly “new age” when I use the term intersubjectivity. Nevertheless, intersubjectivity is a phenomenon considered and acknowledged in philosophy, psychology, sociology, and anthropology as a psychological relation between human beings—a kind of cognitive universalism. Within philosophy, intersubjectivity has been thoroughly treated by German philosopher Edmund Husserl (1859–1938), the founder of phenomenology, as well as by French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908–1961). The concept of intersubjectivity in Husserl’s philosophy indicates that although my subjective, individual perception of the world belongs to me, and another human being’s individual perception belongs to him or her, the world is immediately, directly, or on a “given” level experienced as one and the same. The intersubjective element of perception unites us. I will return to the concept of intersubjectivity and the important link between this term and intuition and the intuitive compass, but first, let’s take a look at why intuition often tends to be viewed as an invalid way of reaching insight and academic knowledge, as initiated at the beginning of this chapter.

The Core of Sustainable Living

The Core of Sustainable Living(…)

Can eidetic reduction also be used to understand and conceptually define an abstract idea like “sustainable living”?

The title of this book contains three main elements: anti-trend, resilient design, and sustainable living. What if we took a closer look at one of these elements while wearing our “eidetic reduction glasses”? As the concept of anti-trend has already been discussed and is furthermore the underlying theme of the entire book, and since a thorough detection and deconstruction of resilient design is presented in chapters Five and Six (in which a systematic analysis of what the anti-trendy design-object is resilient to is conducted), let’s take a look at the present idea of sustainable living.

Is it possible to reduce or deconstruct sustainable living in order to gain insight into its core essentials, and hence to apprehend what it essentially means to live sustainably? Or is what it means to live sustainably simultaneously too abstract and too individualistic and distinctive for it to be generalized?

Maybe it is, but let’s try. Since living sustainably can seemingly mean many different things and have different and very diverse expressions or “looks,” the concept actually almost calls out for a core-definition. And since eidetic reduction is an imaginative variation-technique that can reveal patterns of meaning and be used for concept definition, using it to conceptually define sustainable living should be possible. The method of eidetic reduction constitutes a way of penetrating appearances as well as assumptions and connotations (which could be related to objects in our surroundings as well as to cultural habits, conventions, or societal phenomena) and leaving nothing but the core-elements behind. The purpose of an eidetic reduction is to capture the essence or nature of a phenomenon, whether a concrete one, like a vase or a chair, or an abstract one, like the idea of the sustainable life.

So, keeping these points in mind: What does living sustainably mean? How can we reduce sustainable living to its core essentials, and thus conceptually define this book’s interpretation on the art of sustainable living?

Sustainable is a multifaceted term that is synonymous to words like durable, justifiable, worthwhile, as well as ecological or “green.” Sustainable living is also linked with “the good life.” However, both durability—green and good living— and viability are ideas that can have a multitude of expressions and manifest in lots of different ways. In order to perform an eidetic reduction of a concept as abstract and multifaceted as sustainable living investigating the different manifestations hereof seems like the natural first step. Once an array of what a sustainable life can look like is outlined, one can embark on seeking the commons, the correlations, the drivers, or the eidos behind the complex surface.

And so, let’s initiate this thought-experiment by investigating various manifestations of sustainable living.

Living green and sustainably tends to connote reducing one’s usage of natural resources by altering one’s ways of transportation, flying less, eating less meat (or maybe none), shopping less (or maybe mainly buying second-hand items), making use of sustainable energy sources like solar power, etc. It is also associated with recycling waste, with reusing product-packaging and cast-off things, and with consuming ecological goods. However, sustainable living can also more abstractly mean living a life that is worthwhile and justifiable. And consequently, an existentialist as well as an ethical dimension is added to the idea of living sustainably: considerations about living a life that one can sustain and endure, a life that doesn’t “wear thin,” a life that one can justify living. In other words, sustainable living can go beyond concrete sustainable efforts and involve reflections on the meaningful and authentic life.

Unless you are motivated to live sustainably, like really motivated because doing so is aligned with your beliefs and values, and because you truly believe that changing your individual shopping habits or that travelling less by airplane will make a difference, you will likely not be persistent with your sustainable efforts, and hence they will be momentary and fleeting rather than enduring. As written in the introduction to the book: even though altering our habitual consumer ways and reducing consumption might sound fairly easy and straightforward, it appears to be unbelievably hard. Despite us being bombarded with horrific pictures of terrestrial and aquatic pollution and wildlife suffering due to the waste that overconsumption produces we still shop, we still discard the majority of our belongings way before they no longer work or are worn-out, and we continue to overload landfills and oceans with trash. Not because we are evil. Of course not. The reason is likely interlinked with the fact that habits are very hard to change, especially if we don’t believe that doing so will make an actual difference, and furthermore part of the reason might be that we are generally becoming increasingly detached from nature and simultaneously detached from the consequences of our actions.

Therefore, understanding the core behind sustainable efforts and sustainable living is crucial in order to see the full picture and in order to grasp the core of what living sustainably means.

Let’s take a look at the outlined concrete sustainable actions from the previous paragraph, which are connected to the three sustainable R’s: Reduce, Recycle, and Reuse.

Reducing is essential to sustainable living. As written in the introduction to the book, I view reduction of consumption as one the most important ways of pursuing a sustainable lifestyle, which I will elaborate vastly on in the upcoming chapters. However, reducing consumption on a permanent, consistent basis requires, as suggested, that doing so feels meaningful and that it is plausible. Taking the motivation for reducing consumption to pieces in order to reach its eidos will lead us to the core-motivation for doing so, just like the simplified eidetic reduction of the vase revealed the essential elements that are necessary in order to call an object a vase.

According to Aristotle a good, fulfilling life worth living and worth sustaining involves seeking a golden mean between extremes—between too much and too little. Only by finding that balance will we be fulfilled and happy. Living sustainably by reducing consumption concurrently doesn’t mean turning away from the world entirely and refusing everything: travels, pleasures, and aesthetic delight. Such a nihilistic withdrawal from society is not a sustainable way of life. Sustainable reduction involves finding a golden mean between mindless overconsumption and extremist detachment from society in the shape of a vivifying acquirement of useful and visually and textually nourishing objects that can establish enduring, aesthetically wholesome repetitions in everyday life.

Sustainable reduction is fulfilling and meaningful; it is life-affirming rather than life-denying, and therefore motivating and enduring.

Correspondingly, we could take a look at the concepts of recycling and reusing and the individual actions that are related hereto, such as sorting trash, using jam jars to store grains and flour, purchasing second-hand garments, buying recycled paper and biodegradable plastic bags, etc. Unless such actions are experienced as meaningful, impactful, or as something that makes a real difference, they are not continuously conducted.

Henceforward, an eidetic reduction of sustainable living must involve seeking the core motivations behind enduring sustainable efforts, not the ones that are performed because they are timely, trendy, or because sustainable consumption has become a way of fitting in and reaping admiring glances from peers, but the ones that reflect a deeply felt desire to live a meaningful life—a life that is incessantly fulfilling and that is ethically justifiable in relation to nature, animals, and fellow human beings. Such sustainable efforts are purposeful and revolve around the free, deeply felt desire to make a difference. Insight into such core motivations is of great value to the sustainable designer as accommodating these in the design experience is a way of creating meaningful, durable design-solutions that can alter unsustainable user-habits and promote the freedom to take action.

Living sustainably seems to revolve around two main elements: purpose and freedom. A sustainable life means living a life that one can sustain; a life that one can endure or withstand. This requires meaningful activities and nourishing repetitions, as well as purpose and direction.

Freedom is another important term, when defining sustainable living. In accordance with existentialist philosopher Sartre, we are condemned to be free, and in relation to living sustainably that means that whatever we do—if we choose to continuously over-consume, or if we choose to reduce our consumption in order to minimize our carbon footprint—we are responsible for these actions, since we are free to sustain or alter them. So, despite habits being hard to change, and that we might feel detached from nature and hence unable to experience the impact that unsustainable behavior has on flora and fauna, we are living in bad faith if we tell ourselves that we are unable to change and to take responsibility.

To live sustainably means living a life that we can endure and justify, and it involves taking full responsibility for our choices and actions.

Freedom is crucial when it comes to authentic living according to existentialist philosophers. But freedom involves responsibility. Freedom without responsibility is indifferent (and potentially unethical). True, authentic freedom is freedom to do what you want and follow your dreams while contributing to something, creating meaningful content for yourself and others, or making a difference for someone. Unauthentic characters in existentialist philosophy, such as Søren Kierkegaard’s Aesthete or Simone de Beauvoir’s Adventurer, whom I will elaborate on in the forthcoming chapter, are free, but they are not happy, and they do not live a life worth sustaining. Their existence is characterized by a range of incoherent, pleasurable moments that temporarily fill them up with joy and pleasure, but in the long run become empty and insignificant. Furthermore, they consciously choose to place themselves outside community and to not engage in any long-term relations with other people (in order to avoid responsibility).

Indulging in hedonism is, in other words, not the key to a fulfilling life that one can sustain and withstand, and selfish pleasure-seeking will (according to Kierkegaard and de Beauvoir) with time become nauseating. One will essentially only by freely engaging in the world and pursuing to somehow make a difference feel truly free and fulfilled. Without purpose and direction freedom becomes recklessness.

I will return to the discussion on the authentic, sustainable life in the upcoming chapters. But first, let us continue with the current investigation of intuitive insights.

(…)

August 9, 2022

Anti-trend report

Dette er et uddrag fra min Anti-trend rapport udarbejdet i samarbejde med PEJ Gruppen, Scandinavian Trend Institute.

Rapporten er bygget op omkring tre hovedtemaer slowness, rawness og flexibility, der kan bruges som inspiration til design af bæredygtige produkter. Temaerne er forbundne og kan med lethed kombineres. Første del af rapporten er viet til tidsåndsbeskrivelse, visuel inspiration og moodboards, anden del til overvejelser omkring bæredygtighed, konkrete retningslinjer for implementering af hovedtemaerne via produkt- og koncepteksempler samt storytelling og målgruppeovervejelser.

***

IntroduktionVores tid er præget af en voksende immaterialisme og en øget miljøbevidsthed. Der er en længsel efter (fællesskabs- og dele-)oplevelser og et tiltagende behov for demokratisk bæredygtigt design, der kan udgøre en antitese til forbrugerismens køb-og-smid-væk-mentalitet. Der ligger et anti-forbrugs-behov heri, som kan virke svært at arbejde med som produktdesigner. Men dette behov skal ikke nødvendigvis betragtes som et benspænd – snarere kan det lede til nye muligheder og måder at skabe designprodukter og -oplevelser på.

Anti-trends udgør en modpol til trend-baseret overforbrug af uholdbare ting. En anti-trend er ikke det samme som en modtrend til fremherskende forbrugertrends; snarere er anti-trends knyttet til holdbare brugs- og livsrytmer. Anti-trends er et billede på hvad det gode liv indbefatter for en given bruger: på holdbare måder at tilrettelægge dagligdagen på og på en velafbalanceret fordeling af arbejde og fritid.

I arbejdet med anti-trends undersøger man ikke blot på, hvad det næste “sort” bliver, men også hvorfor. Hermed kan man i højere grad implementere en langsigtet designstrategi, som har fokus såvel nutidige som fremtidige behov. Eksempelvis: Hvorfor har Slow Living fortsat stor tiltrækningskraft? Hvorfor er der en øget efterspørgsel efter håndlavede ting? Hvorfor er fællesskabs- og naturoplevelser i høj kurs? Og ikke mindst; hvordan kan disse behov imødekommes?

At designe produkter med udgangspunkt i anti-trends kan blandt andet omfatte anvendelsen af materialer, der forfalder æstetisk, eller som er fleksible, foranderlige eller reparerbare og dermed tilskynder til brug. Eller det kan involvere et arbejde med temaer, der er knyttet til universelle, menneskelige behov som f.eks. fællesskabsfølelse, forbindelse til naturen og behovet for at høre til og føle sig hjemme.

At arbejde med anti-trends er en tilsidesættelse af modens “trend-logik”, der dikterer, at en trend altid mødes af en modtrend, som indbefatter et diametralt anderledes look eller en livsstil i forhold til den forudgående trend – og at forbrugeren dermed konstant må udskifte sine ejendele for at være up to date. Det svingende trend-pendul, der styrer denne trend-logik kan ikke anvendes i arbejdet med anti-trends. Derimod ligger fokusset på at imødekomme langvarige, dybtfølte behov og skabelsen af funktionelt og æstetisk bæredygtigt design.

Design i det 21. århundrede bør ikke længere være knyttet til forbrugerisme, men snarere til brug og bæredygtige løsninger: det bør understøtte en harmonisk og tilfredsstillende livsstil, der ikke kræver hyppigt “hamskifte” og sæsonbaseret udskiftning af interiør. Der er et væld af måder, hvorpå man som produktdesigner kan gøre bæredygtig livsstil mulig for alle; at leve bæredygtigt bør ikke være en luksus for de få, men snarere det gængse.

Følgende korte uddrag er fra anden del af rapporten. Den fulde rapport kan købes på Trendstore.

***

At arbejde med bæredygtighed“The best arguments in the world won’t change a person’s mind. The only thing that can do that is a good story.”

Richard Powers, The Overstory

Hvordan arbejder man med bæredygtighed på en troværdig måde, som føles relevant for modtageren? Og, hvordan kan man skabe bæredygtige produkter, som er tilgængelige for en bred vifte af brugere?

Bæredygtighed er et begreb, som bliver brugt meget, måske endda for meget, og som derfor har en tendens til at blive udvandet og fremstå meningsløst. Derfor er det afgørende at være tydelig omkring hvilke bæredygtighedsaspekter, der arbejdes med, hvilket kan gøres ved hjælp af storytelling. Hvadenten man arbejder med langtidsholdbarhed, social responsibility, upcycling, genbrugsmaterialer, øko-materialer, sundhed, muligheden for reparation, fleksibilitet eller æstetisk bæredygtighed så skal det vises og beskrives med malende vendinger og gerne med masser af personlighed og visuelle elementer. Transparens og vedkommenhed bør være nøgleordene.

En hjørnesten i arbejdet med bæredygtigt design er at få forbrugeren til at forstå vigtigheden af at købe færre, men bedre produkter, som holder længere i mere end én forstand; både i forhold til kvalitet og i forhold til udtryk. Som en del heraf er det afgørende at kommunikere, hvorfor gode, vellavede, veldesignede objekter, der er skabt til at holde i mange år – eller etisk producerede produkter, som sikrer de mennesker, der står bag produktionen ordentlige levevilkår – koster penge. Er forbrugeren ikke villig til at betale det, som langsomt producerede produkter skabt med udgangspunkt i en grundig designproces reelt koster, er det svært for alvor at gøre en forskel som designer og medvirke til at eliminere overforbrug. Det er afgørende, at forbrugeren er indstillet på at lægge sit forbrug om. Dette betyder ikke, at der skal bruges hverken færre eller flere penge end tidligere, men snarere at det samme antal kroner og ører skal bruges på færre (men bedre) ting.

Som skrevet i introduktionen til denne rapport bør behovet for at reducere forbrug, leve mere bæredygtigt og invitere mere langsomhed og nærvær ind i dagligdagen som kendetegner vores tidsånd ikke ses som et problem for designere og producenter af tøj, møbler, interiør mm. Tværtimod! Der er masser af muligheder for at skabe nye forretningsmodeller, der er funderet på brug snarere end forbrug, for at skabe services, der muliggør udskiftning og opdatering af produktdele, for at udvikle koncepter og produktoplevelser, der opfordrer til nærvær og fællesskab, for at invitere brugeren med ind i designprocessen, og for at nå ud til segmenter, der ofte overses eller nye segmenter, der er voksende.

I de kommende tre afsnit præsenteres en række konkrete eksempler på hvordan man som designer og producent kan arbejde med de muligheder vores tid indeholder og skabe overbevisende storytelling og holdbare produktløsninger. Udgangspunktet er de tre overordnede anti-trends Slowness, Rawness og Flexibility.

Køb Anti-trend rapporten her, enten alene eller i kombination med den nye Greenery rapport, som har fokus på plantetrends.

July 28, 2022

The rewilded city

The most sustainable city is a rewilded city – a city with space for diversity and for life to unfold in all its raw, messy forms and shapes. A city that isn’t too polished, homogenized, or cultivated. A city that is made for living, all kinds of living. A city that embraces life and is flexible, adaptable and updatable. This requires a degree of ruggedness or even space for “ugliness”: if there is a homogeneous, uniform concept of what a picturesque, well-organized city should look like this tends to limit opportunities for development, creativity, and free, messy living. Not that organization and efficiency is a no-go – obviously city-planning is important. But momentarily there is a tendency of eliminating all the “rough”, non-groomed areas in developed cities, and that cultivation and homogenization is reducing space for free, unorganized, impulsive, interim living and creative expressions.

In many cities, including my hometown Copenhagen, the raw areas in which unrestricted creativity unfolds and a degree of liberating “ugliness” is allowed to grow are constantly endanger by the cultivation of exclusive, homogeneous buildings. This cultivation of the city is the opposite of rewilding. Rewilding involves making space for life to flourish; it is a flexible, spacious approach that ensures the existence of “pockets” of ungroomed areas that can be shaped by the people who live there, and hence develop in accordance with life. Cultivating a cityscape on the other hand means cleaning up and making everything look picturesque and nicely polished, which in itself might sound intriguing, but is often a lifeless and stagnant procedure. Life is not static and motionless, and therefore designing or building for immobility and static perfection is the same as creating objects and buildings for admiration from a distance, not for living, not for usage, not for wear and tear, not for weathering.

But perhaps the goal with city-cultivation is increased consumption? When perfectly polished buildings, parks and squares decay they need to be re-groomed, re-polished, re-cultivated, and hence the ongoing battle against user traces and weathering sets in.

Allowing for rawness and flexibility in buildings and plazas is a way of inviting lived life in; of allowing the life of the users and inhabitants to shape and to mold. And it involves viewing user traces and decay as beautifying or enhancing rather than blemishing. In that sense, the processes of rewilding the city and rewilding nature are not much different. Rewilding involves letting life unfold, unrestricted and uncontrolled. Of creating a frame for unfolding (or allowing for an already existing frame to endure and evolve), and then, importantly (!), stepping back and letting whatever is meant to blossom and flourish grow.

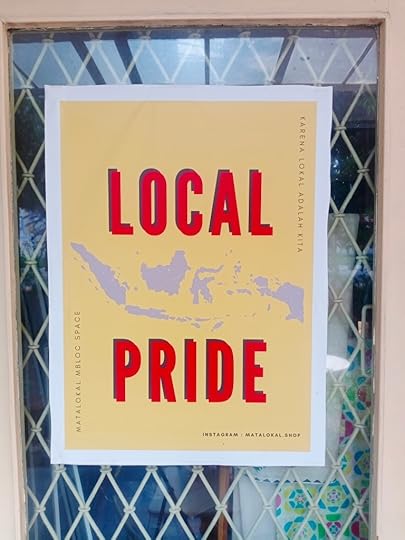

At this writing moment I am in Jakarta together with my oldest son, and blown away by the collage of a city this is. Now, I am not saying that there is anything sustainable about this city; it is highly polluted and literally sinking. As a matter of fact, it is supposed to be the most rapidly sinking city in the world, which at the current rate of sinking, meaning unless something drastically is done to turn around this development one-third of the city will be under water in 2050. North Jakarta is sinking 25 centimeters annually at the moment. The reason therefore is a combination of rising sea levels and an immense overuse of ground water due to massive development. So, sustainability in the ordinary sense, as in “green” is not exactly what one will experience here. The city is characterized by heavy traffic and smog, and an ever-increasing inequality between populaces that fosters immense poverty.

However, in relation to the above definition of the rewilded city there are fascinating “pockets” of diversity, street life and rawness to experience here.

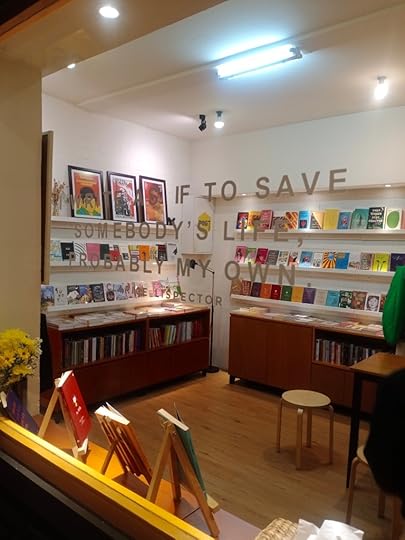

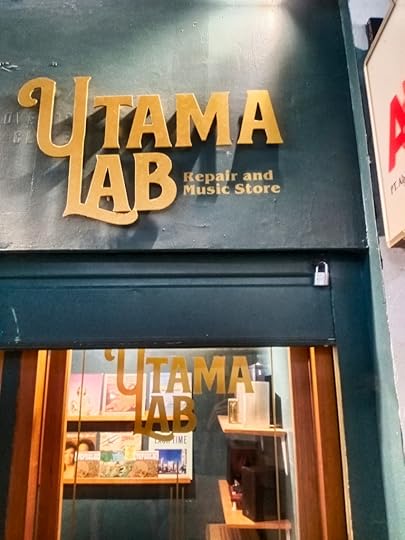

Yesterday, for example, I went to an old abandoned looking mall (really ugly place with dark corridors, fluorescent tubes in the ceilings, and peeling paint on the walls in an impossible 80’s color palette; cobalt blue, bright green, orange and brown). To my big surprise, however, the top floor of the mall had been taken over by creative hipsters, independent bookshops and small record studios. There was even a repair shop, which offered repairing your outdated electronics while you could drink a café latte and listen to records (I was very fond of this place, as the overconsumption of electronics and electronic waste is one of the main current polluters, only topped by the consumption of fast-fashion clothes and accessories). Vintage shops with colourful hippie clothes, corduroy bell bottom pants, felted hats, handmade jewellery and curiosities such as cartoon figurines, old toy cars, and feathered decorative ornaments were spread out throughout the corridors next to food stalls with delicious street food and matcha lattes. Cuddly, yet tough looking cats were hanging out next to the food stalls looking to be fed and petted. As mentioned, a couple of independent book shops were also to be found here with an amazing selection of e.g., Indonesian and international poetry, queer fiction, eco manifests, and feminist literature. I spoke to the owner of one of the book shops, and she said: we are so lucky being here, because the rent is low and stays low, which allows for us to curate with our heart. This notion would also explain the independent record stores and the small recording studios.

At the floor underneath, tailors were spread out throughout the dark corridors, and on the ground floor fruit, vegetables and fish was being sold by elderly ladies from their interim stalls. This made me remember that I was still in Indonesia, because the assortment and array of people on the top floor could have been found in any diverse large city.

All big cities have places like this mall; places that never turned out the way they were intended to. That are deteriorating and more or less abandoned. And, typically such places are demolished in order to make space for new, polished, neat places with the intention of modernizing the city. However, when the diverse life of a city is allowed to unfold, mold and shape such “un-places”, something enchanted occasionally starts growing. It is not always the case, of course. Sometimes the decay develops into a degree of irreversible neglect. But other times, when lived life and inventiveness is allowed to unfold, something beautiful occurs.

The rewilded city is a place that allows for unrestricted creativity to blossom.

May 30, 2022

Uncultivated: We have to adapt and behave

This post contains another extract from my new Uncultivated book project. The book is built around negations of what I have chosen to call “the ten commandments of cultivation”. The intention herewith is to challenge taken-for-granted cultural and societal “truths” and assumptions and to promote a rewilding of the cultivated human being.

The ten commandments are the following:

We have to adapt and behaveWe are superior to animalsWe are separated from natureWe must be ambitiousWe have to work hardWhat cannot be explained is not trueWe do not talk about deathDecay must be defeatedTime is linearGod is deadIn this post I will share a short passage from the first section: We have to adapt and behave.

***

We have to adapt and behaveWe lived in the city when he was small. He went to a completely ordinary city kindergarten and hated every minute of it. “The children’s prison”, he called it, even though it was actually an excellent kindergarten with sweet educators and children. Every single morning it was a struggle to get him going. Getting him to wear boots and warm overalls in the winter made it even worse. He said: I cannot move! I cannot feel anything! And he screamed. I felt like the worst mother in the world when I left him in the kindergarten while he was being held back crying by one of the educators, who always assured me later in the day that it had stopped (the crying, that is) as soon as I was gone, and that he had had a really good day. But one cannot tame wild nature. Or you can, but it destroys it slowly. And he understood that intuitively. And so, he fought back. Vigorously. To save himself. Or, to sustain himself.

We realized we had to do something. Our daily life was unbearable because we had a constant bad conscience when he was in kindergarten, and every night we feared the morning struggle. We were told that he was challenging us. That it was a power struggle that he was trying to win. That we should stand firm and not let him decide. Not let him win. That he would get used to it with time. But I knew it was not true. I knew that for him it was all about self-preservation. That he fought for the right to his way of being in the world. The right to develop and be who he is. It wasn’t that he wouldn’t adjust to anything, just not to this.

So we did something.

We started looking at farmhouses in the southern part of Denmark; entertaining the idea that perhaps if every weekend we would leave the city and go to the countryside to get recharged things would change. Moving out of the city entirely seemed like too big a step for us at the time. What about schools? What about the neat coffee shops we had at every corner, and at which we thoroughly enjoyed working on our laptops? What about our friends? What about our beautiful, bright apartment in the city center? And, of course, what about our jobs? There seemed to be too many obstacles. But every morning as the struggle began; getting our youngest out of the door, into the cargo bike and delivered at kindergarten, and hereafter, with a growing lump in the throat, bike to work or to a café to write, solely thinking about how soon we could be back at the kindergarten to pick him up, the dream of a tranquil countryside existence grew stronger.

We convinced each other that the weekend country house could be the solution, so we spent weekend after weekend driving around looking at houses. But every time we sat in the car on the way back to the city, we were quiet. We both felt that it wasn’t quite right. It wasn’t the solution. And, one Sunday after looking at a house with a big barn and a beautiful garden for the second time, sitting quietly in the car driving back, contemplating silently on solutions and scenarios, I said something that changed our direction entirely. I said: we will never do this, right? My husband looked at me: no, he said.

And that was that. Our weekend country house dream ended right there in the car on a Danish gray October Sunday.

I think part of why we just suddenly knew that the weekend country house wasn’t the right step for us was the realization that it wasn’t a big enough step. Well, in terms of financial obligations it was a huge step, but not existentially. And the last thing we needed at that point was more expenses and less freedom. It would have been the most conventional thing to do though, and the most cultivated too. Leading a cultivated life tends to involve slowly expanding one’s material possessions and as a part hereof expanding one’s premises.

We contemplated a different strategy too: moving to the countryside and setting up a life there. But we were warned by numerous friends: you must make sure you pick the right area with likeminded people, otherwise you will come running back, they said. It felt right, so we stayed put.

(…)

May 9, 2022

On reading nature

In a few of my previous posts I have shared extracts from my new Uncultivated book project. The book is built up around negations of what I have chosen to call “the ten commandments of cultivation”. The intention herewith is to challenge taken-for-granted cultural and societal “truths” and assumptions and to promote a rewilding of the cultivated human being.

The ten commandments are the following:

We have to adapt and behaveWe are superior to animalsWe are separated from natureWe must be ambitiousWe have to work hardWhat cannot be explained is not trueWe do not talk about deathDecay must be defeatedTime is linearGod is deadIn this post I will share a passage from the section: We must be ambitious.

Some things cannot be forced.

***

We must be ambitiousMy youngest son is slow at learning how to read and write. It seems hard, uninteresting and irrelevant to him. The usability of it isn’t clear to him yet; and unless a skill appears relevant and usable it will always be wearisome to learn.

However, he is an amazing reader when it comes to reading nature. He will say: when the cicadas’ song turns into loud screams at sunset (listen mum!), it means that rain will start shortly (and yes, it sure does), when gusts of wind shake up the tree crowns like that it means that thunder is on its way, and: look at those patterns in the sand; a snake, a scorpion and some red ants have been here, but it is a few hours ago. He will say: never walk through tall grass like that in flipflops; you might scare a snake, and: when you walk through the jungle, stamp your feet like this (he shows me), because the snakes can sense the vibrations from a long distance and will stay away. And, when the croaking of frogs sounds a bit like it is coming from inside a bathroom or a fridge, it is because the frog is being eaten by a snake; it is on its way down its neck. The other day when he was bicycling home from the nearby river a heavy rainstorm surprised him, and he returned soaking wet accompanied by his dog Saga, he said: I was wondering why there was a really dark grey line at the bottom of the sky! Now I know what that means: get home as soon as possible, especially when you have to cycle through a field of tall coconut palms! (coconuts can fall down during storms and rain showers making it very dangerous to walk beneath them).

In the more magical genre, he will say: there are many waves in the ocean today, because a lot of people died today; every time someone dies the ocean makes a wave. And: the reason people get sick is because we are cutting down so many trees; we are connected with them: what they breathe out, we breathe in, and what we breathe out they breathe in.

He is curious and has a researcher’s approach when it comes to reading nature: will investigate, draw, gather samples, and explore connections. He is hungry for knowledge about nature, human intervention and interconnectivity; has a million questions of which I can only answer a fraction. Why can trees only grow to a certain height? Why do people eat pigs but not dogs – well, why do people eat animals at all; it’s not really different than eating humans? Why can’t people and animals talk? Why don’t different kinds of birds mate like different kinds of dogs do? What are stars made from? Why are leaves green?

He will lecture me too: did you know that female praying mantis (we have lots of huge ones here) eat the males when they make babies? And: did you know that there are a ton of plants that are eatable to humans that we never use for food?

He has a deep respect for nature. A respect that is fostered by him growing up in truly wild nature; not the cultivated, tamed nature that characterizes my motherland, but nature that can be dangerous, and that you need to know how to navigate in order to not get hurt or lost. Nature that is wild, raw and enchanted.

He might not be a strong reader and writer (yet), but he can make paint out of minerals, use plants for cloth-dyeing, build a small windmill, make healing tea out of herbs (he knows exactly what can be used and how to make the perfect blend), lay out a vegetable garden (he knows which plants should be placed next to each other and why, and he also lectures me on pollination by insects), take care of a great variety of animals: chickens, goats, dogs, cats, turtles, fish, tadpoles (he is feeding tadpoles in different growth stages at the moment; investigating their development thoroughly), cook an excessive selection of tasty dishes (including amazing vegan sushi, only slightly mashed), make recycled paper sheets out of discarded paper scraps, stitch and weave with yarn, fold all sorts of animals of origami paper, make toy cars out of bamboo, navigate with a compass, differentiate between venomous and non-venomous snakes, meditate and do yoga poses, use mantras to clear his mind and show gratitude, cut tropical fruit into perfect symmetrical shapes with a pocketknife, open a coconut by hitting it on a rock etc. etc.

(…)

As a sidenote; after I wrote this my son suddenly started reading. No problem. It seemed as if the capability was always there, dormant, and only once he found use for it, it came out.

Some things cannot be forced.