Kristine H. Harper's Blog, page 7

November 4, 2021

Thoughts on the Importance of Change

Today I want to share an extract from my new book project with the working title Uncultivated. I am in process, so sharing this is mainly to test it here in my online laboratory: in other words, comments, critique, thoughts, and suggestions are more than welcome!

This extract is written when we were still in Spain, and I have just dug it out in order to continue the thought process. I find it more and more important to embrace change in all shapes. Not least in education. In my book Anti-trend I also explore change and openness in relation to the sustainable design-object.

The book is built up around a negation of the 10 commandments of cultivation:

We have to adapt and behaveWe are superior to animalsWe are separated from natureWe must be ambitious We have to work hard What cannot be explained is not trueDeath is dangerousDecay must be defeatedTime is linear God is dead

This short extract is a comment and antithesis to Commandment no 4: We must be ambitious:

“The other day I asked my oldest son to put words on how he feels about being at the school he is attending at the moment, which is based on the British National Curriculum, and is very traditional in its approach to learning (more or less only classroom style learning, frequent tests etc.), and which he really doesn’t like. I wanted to get insight into what exactly it is that he doesn’t like, because I know that he doesn’t mind working hard, that the tests don’t frighten him, and that he enjoys learning. I asked him to sit quietly for a bit and think about his discontent and then just start writing freely, exactly what first came into his mind. He wrote: When I am at school, I feel like nothing ever happens: the teachers do the same every week, nothing ever changes, we do everything at the same time, every day, every week. I feel like the other students in my class will never change either. When I do something different than usual, it is normally against my teachers’ will. I never feel like I fit in there, because I change over time, but I feel like I am not allowed to, and that nothing at the school will ever change.

Change is natural. Change is one of the only thing we can be certain of: we change constantly; our moods, feelings, and bodies change – change is a part of life and of our everyday existence. Like my son put it: I change over time. And I can only say that yes, he does! And that fighting that change would be like fighting the natural flow of a river and the waves in the sea. I see the change, at the moment I actually notice the changes he is going through nearly every day, because he is a young teenager and is growing like a weed; slowly becoming a man. And I feel his change too—it materialises in questions like: when did you move away from home, mum? And comments like: When I see the teenagers in this little town (the town we are at this writing moment living in), I just know that they will live here for the rest of their lives; it’s like, I see this young couple with one or two small children, and I can see that it is the teenagers that I just walked by in about 10 years. But for me it’s different; I have no idea where I will live, and I like it that way. And also, in his sudden, very cultivated ability, to make conversation—he will say: mum, how is your friend Susanne doing, have you spoken to her recently? Or, how was your day; did you get anything written?

Not only we, but our surroundings are also in constant flux: you cannot step into the same river twice, as the ancient pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus put it: the water stream is constantly flowing changing the structure and composition of the river. But in the traditional school system there isn’t much space for change—for thinking out of the box, or for turning things upside down or tearing them apart in order to seek an untraditional solution. Cultivation involves normalisation, and normalisation is largely a business-as-usual-approach. The same things are done over and over again, the same ways of teaching and learning are repeated throughout generations, the same tests are used, the same curriculum is used continuously and nationwide, the same discussions are conducted, and the same goals are lined out. These goals are principally aiming towards one day getting a good exam result, so that one can continue at a good graduate school, and hereafter get a well-paid job.

But as the world is ever changing, how can we teach and expect children to learn in the same way as their parents and even their grandparents? How can we assume that the same skills are still needed? (…)”

October 15, 2021

Take only what you need

My head has been about to explode this past week. I am filled up with the wisdom from Daniel Quinn’s Ishmael that I finished reading a couple of weeks ago (actually, filled up is an understatement; it has gotten to a point where my family is getting slightly annoyed with me and my: “now you are letting Mother Culture’s stories control you again”, or “that is such a Taker-attitude…!”, or “well, Ishmael wouldn’t agree here” – I guess outbursts like that get rather irritating after a while, especially if you have no idea what the obsessed “outburster” is talking about), I started reading The Story of B (mind-blowing!), I am super inspired by a man I met some months back, and with whom I have been communicating ever since about biodiversity, fireflies, and holy cows (I will get back to that shortly). Furthermore, I am inclined to take my immaterialism even further by constantly encouraging myself to take and consume only what I need. And, last but not least, I received the first printed copy of my new book Anti-trend last week, and I am feeling so grateful to see all my thoughts and theories on sustainable living and resilient design in beautiful print accompanied by an abundance of inspirational images and embraced by an amazing cover hand drawn by Ted Guidotti (the book is not officially published yet, but can be preordered).

A browse through my new book Anti-trendLet’s start with the holy cows. I met Wayan Wardika a few months ago at Omunity Bali. We were talking over one of the beautiful vegan meals that are always served there. His stories on diversity and balance between humans and nature were very captivating, and I knew I needed to hear more about his approach to sustainability, so our conversation continued via phone the following weeks.

Wayan lives in a village called Taro north of Ubud. He is engaged in the cultivation of biodiversity by rewilding nature and implementing permaculture principles. Taro is known for its holy white cows. These cows are considered sacred and are carefully taken care of by the locals. The holy white cow symbolises the hindu goddess Shiva. In Balinese hinduism Shiva is the creator, the maintainer and the destroyer of cyclic existence: she is the sustainer of natural balance. This symbolism manifests in the holy cows of Taro in several ways: for example their manure is used as a natural fertilizer, and it is known for also having healing powers. In other words; the soil is not only nourished, it is also healed by the manure from the holy white cows. Furthermore, the urine from the white cows is used to make a natural (yet very effective) pesticide by mixing it with herbs and fermenting it. The herbs used have an naturally “spicy” or bitter aroma, such as ginger, turmeric and lemongrass. When this mixture is sprayed on the plants that are being farmed bugs will stay off them, and hence the plants are protected and can thrive. The mixture is also an organic fertilizer.

The other morning I was sitting in my open house enjoying my morning tea, as I heard a strange sounds. Kind of the sound from a spray bottle that kept going. I looked into the surrounding jungle and saw a man walking around carrying a container on his back (making him look like a Ghost Buster), spraying its content onto the ground. The man farms papaya on the land around my house, and it turned out that he was spraying pesticides (unfortunately not the organic kind that is produced in Taro) around the trees. I asked why, and he said: to kill the weeds. (Among other things, I thought.)

We have been told by Mother Culture (sorry to use Ishmael’s words once again) that weeds are bad and must be killed, as they limit the farming of human food. But we forget that weeds are an important part of the food chain, and that wild growing weeds are the habitat of insects, mice, birds, snakes etc.

The white cows in Taro village, Bali are considered sacred by the locals.

The white cows in Taro village, Bali are considered sacred by the locals.Oh, and the fireflies. As Wayan and I were talking at Omunity we were overlooking the surrounding rice fields, and Wayan said: there are so many certifications that are supposed to indicate sustainable farming and commitment to the environment, but many of them are nothing but greenwashing. Do you know what the only true certification in a climate like this is? Fireflies! The existence of fireflies is an indication of a good environment; clean air, non-contaminated water, and high soil quality, because fireflies only live in environments with well-developed biodiversity. Its simple: Less pesticides equals more fireflies! That is a very tangible kind of sustainability certification, and most importantly it is impossible to manipulate.

The most reliable indicators for a sustainable environment are to be found in knowledge on food chains and biodiversity. Wayan also told me that fireflies have been disappearing for years in many areas in Bali. Monoculture and usage of toxic pesticides destroy their habitat. The most sustainable way of life is interlinked with diversity. Not only in nature, but also among us human beings.

All of Wayan’s knowledge on balance and diversity that he manifests together with his fellow citizens of Taro village is in direct opposition to what Daniel Quinn describes as totalitarian agriculture in The Story of B. Totalitarian agriculture subordinates all life forms to the production of human food – simply put, it is build up around the belief that the whole world belongs to us humans, and that we have the right to turn all land into human food (however, despite us doing so there is still famine in many parts of the world). The mantra is growth, and the consequence is loss of biodiversity and ecological imbalance. As a part of, what Daniel Quinn describes as The Great Forgetting, human beings forgot the simple, yet profound wisdom of taking only what you need.

The people of our culture are used to bad news and are fully prepared for bad news, and no one would think for a moment of denouncing me if I stood up and proclaimed that we’re all doomed and damned. It’s precisely because I do not proclaim this that I’m denounced. Before attempting to articulate the good news I bring, let me first make crystal clear the bad news people are always prepared to hear. Man is the scourge of the planet, and he was BORN a scourge, just a few thousand years ago. Believe me, I can win applause all over the world by pronouncing these words. But the news I’m here to bring you is much different:

The Story of B, Daniel Quinn

Man [Woman] was born MILLIONS of years ago, and he was no more a scourge than hawks or lions or squids. He lived AT PEACE with the world . . . for MILLIONS of years. This doesn’t mean he was a saint. This doesn’t mean he walked the earth like a Buddha. It means he lived as harmlessly as a hyena or a shark or a rattlesnake. It’s not MAN who is the scourge of the world, it’s a single culture. One culture out of hundreds of thousands of cultures, OUR culture.

And here is the best of the news I have to bring: We don’t have to change HUMANKIND in order to survive. We only have to change a single culture. I don’t mean to suggest that this is an easy task. But at least it’s not an impossible one

September 20, 2021

Interview #10: Repair Enthusiast and Author Isabelle McAllister

I have been looking so much forward to sharing this interview with you. Not only because Isabelle McAllister is a brilliant sustainable visionary and activist, but also because she is a dear friend of mine.

Isabelle and I met around three years ago here in Bali, when we had both just moved here. We have had a myriad of inspiring discussions, and she always has a way of asking thought-provoking questions and making me see things in a new perspective (which I love!). She is constantly searching for new knowledge and continuously tips me on inspiring podcasts to listen too or new books to read.

Isabelle recently published the book Skavank (in Swedish), which means imperfect, flawed or broken, and is filled with aesthetically nourishing photos of beautifully decayed things, inspiration on how to repair broken belongings (and convincing visual proof of how these repairs will make your things more appealing and valuable), encouraging thoughts on the importance of reducing consumption by mending and upcycling the things we already own, and lots of vintage bliss and tactilely inventive house restorations.

Besides from being an author, Isabelle runs the podcast Fornyarna, is an incredibly thrilling instagram activist, a scholarship founder, DIY enthusiast, and climate advocate. Yes, she is active! And, yes she is inspiring!

***

What does sustainability mean to you?To be kind. And really mean it. In action and words. Saying this almost sounds naïve but I think that is more a realisation of how far we are from really trying to take care of the planet and each other.

Sustainability to me is also a wish to form a deeper connection between all things living.

***

How would you describe your mission in Skavank?Skavank (translates as imperfect/flawed/broken) is a book about our things, about our relationship with them and how we can mend, tend and care for the stuff we surround ourselves with.

The new and fresh has been desirable for so long (in relation to both people and things), and the trends have fluctuated extremely fast. It has often seemed more efficient (and cheaper!) to buy new than to repair. I have worked with interior projects, design and DIY for several decades and contributed to both new consumption but also reuse over the years.

Over time, the unsustainability of our consumption rate has become increasingly clear to me. Things are so quickly becoming obsolete and consumed that we don’t know how to take care of our stuff, mend, repair and make use of traditional handicraft. We are losing the knowledge of working with our hands. So many things that we consider as finished and obsolete can be restored and valued if we change our ideas about them.

Skavank wants to challenge old thought patterns, tell about the properties of different materials and show how old and chipped things can get a new life. Isn’t it also the case that the things that are already pre-owned and handled – by us or by others – hold something that new stuff lacks; patina, provenance or personality? Something that requires time, care and durability. A kind of acceptance of the transient.

This book wants to show the beauty of the imperfect, and the satisfaction of taking care of something. To use what you already have for as long as possible is one of the best things you can do for the planet – and maybe the process of doing so can heal us too.

***

What do you view as the biggest environmental problem?Probably the polarisation in society. We try to simplify and see everything as black or white, profit or debt, bad or good and straight when life is actually a rainbow!

I think most issues tend to be both complex and simple, but somehow most of us mix them up, so we don’t know what up or down anymore. I think it’s time to go back to basics, to find the core – the roots of what, how and why we do things: to Re-wild.

So, maybe time is the biggest environmental problem. The system that has provided us with the illusion that we need to fill our days to the brim with things that are not really important.

***

What are your working on at the moment – and what’s next for you?I’m still working with my new book Skavank. It’s a starting point for many conversations, so I’m doing podcasts, interviews, moderate conversations and giving talks. I also facilitate workshops with more hands-on crafts – how to practically make your things last.

Other than that, I’m trying to find my way in this transformation that is needed – so where can I serve and be useful in the best way? I always worked very broad, in many different contexts. I like it, but sometimes it takes a little bit longer to find a clear path. Also, I have realised that the idea of a clear path is just an illusion and that in transformations normal rules don’t apply – so I’m basically just trying to enjoy the ride!

Read more about Isabelle here.

September 16, 2021

Interview #9: Lisa Wells, author of ‘Believers’

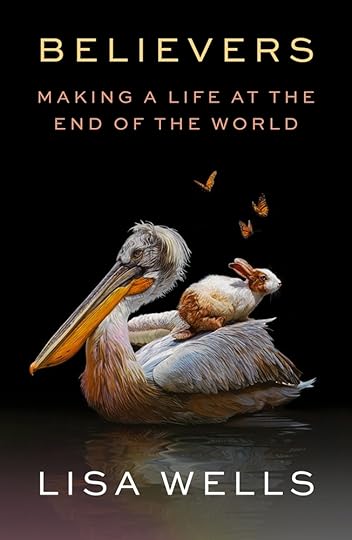

I am excited to bring you yet another interview with an incredible sustainable visionary. Lisa Wells is an american poet and essayist and the author of Believers: Making a Life at the End of the World which is her first nonfiction book.

I fortunately stumbled upon Lisa’s thought-provoking approaches to sustainability in her recent podcast interview with Futuresteading. I was listening to the interview last week whilst riding my motorbike from our little jungle village to Ubud to pick up my youngest son from school. And, listening to Lisa saying things like: “let’s recognise that we are just creatures on this planet with a very short life that should be as joyful as possible, and one of the ways that we get joy is by doing the things that are going to heal us and create abundance,” made me feel like: “yes! Exactly”, as did her talking about the importance of both making individual steps towards a more sustainable lifestyle by building and nourishing local communities and fostering personal bonds to nature, and trying to affect political change by for example showing up for future generations at protests: that we need all of that and everything in between.

When I got home I ordered the book and wrote to Lisa to ask her to do an interview for The Immaterialist. Now I am hoping that Believers will reach the jungle before too long, as the extracts and interviews I have found online have triggered my interest even more. Not least since it appears that one of the predominant missions of the book is to do away with the sustainability-mantra of “leaving no traces”. The people Lisa visits leave traces; they shape and affect their surroundings, only in a sustainable way

It took Lisa six years to write Believers, which is built around a series of interviews with off-grid believers and activists who are all dedicated to reconnect to earth and to save the planet from human exploitation and climate change.

The believers in the books demonstrate that there is not one answer to how to live sustainably; there are many.

***

What does sustainability mean to you?It’s a question worth asking. Before I started writing Believers I hadn’t given it much thought. I had gauzy, culturally received notions of sustainability in the vein of “leave no trace.” As I dug into the stories in the book a thread began to emerge about the impacts of those received ideas and where they came from. In the U.S., settler-environmentalists like me grew up with a conservationist literature and ethos that exalted nature and treated so-called wilderness areas as cathedrals. But nature was separate, nota community of life they belonged to and shaped. The whole thing is predicated on the idea that humans don’t fill an ecological niche like every other creature on earth. It’s also an erasure by omission of ancientland-tending traditions that were practiced for most of human history all over the world.

In short, what sustainability doesn’t mean is “leave no trace.” So what does it mean?

The book’s answer is provided by the people I write about, and most have a similar message: commit to a place, feed that which feeds you, give life to that which gives you life, plant more seeds than you harvest, etc. If your lifestyle can sustain you, your community, and the myriad lives you depend on indefinitely you’re probably on the right track.

***

How would you describe your mission in Believers?My foremost mission as a writer is to keep the reader interested. I try my best to honestly explore difficult questions without paying lip service to the doxa or defaulting to cliché. I’m always interested in increasing complexity. I don’t always succeed and acknowledging my own short comings and poking fun at myself is part of the agenda, too.

My Believers-specific mission was to discover ways to live that support life on the planet now and for future generations. At the time, I felt like the discourse was pretty heavy on “dismantlement”—which is great—but I don’t think it’s enough to tear stuff down, we also need positive constructs to live into.

If our descendants are alive and well in 100 years, it will not be because we exported our unexamined lives to another planet. It will be because we were, in this era, able to articulate visions of life on earth that did not result in their destruction.

Believers: Making a Life at the End of the World

***

What do you view as the biggest environmental problem?The civilization most of us live within is our biggest problem: an expansionist, hierarchical system dependent on what Daniel Quinn called “totalitarian agriculture,” so named to “stress the way it subordinates all life-forms to the relentless, single-minded production of human food.”

Atmospheric carbon from industry, deforestation, soil degradation—they all come back to this single system. The good news is, for most of human history people have lived in heterogenous ways that support the health of the soil, the air, and of their ecosystems so it’s something we’re quite capable of doing.

***

What’s next for you?I’ve just finished a piece for Harper’s Magazine about composting human remains (spoiler alert: I plan to have my corpse turned into compost!)

I’ve also been exploring group dynamics and the unconscious forces that shape them. I don’t plan to look at it exclusively through the lens of environmental impacts, but I do think much of what we’re afraid to let go of—stuff like climate control, streaming TV, eating for sport, etc. are the consolations of the chronically stressed and isolated.

Many of us have lost our ability to live together cooperatively over the long run, but there are interpersonal technologies that can help us remember how, and I think that’s the huge prize we stand to gain as infrastructure collapses. We are wired for interdependence and without it we miss out on a lot of meaning and purpose, belonging and pleasure… You can’t override millions of years of social adaptation in a few hundred, or even a few thousand years of empire.

Read more about Lisa and her work here.

August 22, 2021

Interview #8: Anti-trend

Five Minutes With: Kristine Harper, Author, “Anti-trend: Resilient Design and the Art of Sustainable Living”

I have been interviewed by Story of Books and am bringing the full interview here on the blog. I was asked some excellent questions about my upcoming book Anti-trend – and about resilient living, sustainable storytelling, crafts preservation, and whether or not the pandemic has altered our view on sustainability.

August 9, 2021

Cultural sustainability

At the moment I am deeply engaged in building up a sustainable weaving collaboration focused on the preservation of endangered crafts traditions and women’s empowerment with my dear friend Putu. The collaboration is called Alamanda and it is located in the village Sudaji in the mountainous Sawan district in the Buleleng region in North Bali. The immensely talented craftswomen with whom we work are masters at endek (ikat) weaving as well as the complicated art of songket (double ikat weaving), which is a weaving technique that results is highly detailed textiles with the same beautiful pattern on each side and hence no purl side. There are only a small handful of weavers in the entire Buleleng region who master the art of Songket weaving, which makes the technique endangered and prone to extinction.

Beautiful double ikat shawl by our amazing Alamanda collaborative.

Beautiful double ikat shawl by our amazing Alamanda collaborative. When traditional crafts techniques and traditional crafts expressions disappear, treasured knowledge and skill is lost. Crafts techniques and patterns are rarely enshrined or written down, and the traditional patterns are typically not sketched and stored, as they are often taught orally, or rather by showing the process by hand from one generation to the next. They are characterised by non-verbal transmission.

When artisans seek other earning opportunities, the crafts traditions die out. This is not only a large cultural loss, but a loss of diversity.

The slow process of endek weaving. Endek textiles are created on the large Alat Tenun Bukan Mesin (Indonesian: Manual Loom)

The slow process of endek weaving. Endek textiles are created on the large Alat Tenun Bukan Mesin (Indonesian: Manual Loom)In my upcoming book Anti-trend – Resilient Design and The Art of Sustainable Living I investigate how to sustain endangered crafts traditions by engaging in the balancing act of maintaining the core of the craft – the technique, hands-on wisdom, the look of the traditional patterns, the feel of textures, etc. – and updating the overall aesthetics in order to innovate. The difficulty here lies mainly in the curious fact that the significant aesthetics – the look and feel of the crafted product – which is linked to a specific crafts tradition is its strength but simultaneously its Achilles heel.

A craft-tradition is typically accompanied by certain motifs, patterns, textures, color combinations, carvings, or shapes, and is restricted to staying within the limitations of these. The motifs and textures are typically charged with connotations; with metaphysical meaning, allegories, symbols, stories, and signs, and linked to certain events or ceremonies – and only worn or used at these – societal status, family ties, or life-phases. And traditional artisans are trained to carry out these conventional patterns with precision. The problem is that the shapes and motifs of traditionally handcrafted artefacts might not meet the needs and aesthetic preferences of others than the narrow target group these were originally created for. Their symbolism might, so to speak, be lost in translation – or carry no meaning when detached from their origin – their function might be outdated, and their aesthetics might not be comprehensively nourishing.

The beauty of songket woven fabrics. This is an example of a traditional pattern taught through generations.

The beauty of songket woven fabrics. This is an example of a traditional pattern taught through generations.In relation to patterns, symbols, and motifs in the woven fabric, clarifying which elements are essential and unique for the region, and which ones are pure decoration can be beneficial. When sustaining a craft tradition preserving cultural and regional characteristics is of great importance. Doing so is also a way of underlining that these particular motifs and patterns are “owned” by this specific region and people despite the fact that they do not have the copyright.

Often regional and traditional patterns are incorporated in high fashion without designers giving credit to the original creators. This lack of credit doesn’t only apply to textile design and garments, but also to furniture, ceramics, jewellery, etc. This is another reason that the status-providing identity of being an artisan is vanishing. Giving credit to the original creators of patterns, techniques, motifs, shapes, etc., is empowering. This can be done through storytelling: telling of the inheritance and the people behind the products, and also – in the case of woven fabrics – by highlighting the crucial patterns and motifs.

This beautiful woman was one of the master weavers in Sudaji village. Her name was Dadong Sentari. She mastered various weaving techniques, such as endek (ikat) and songket (double ikat or two-sided ikat), and memorised a multitude of traditional patterns packed with symbols and anecdotes. She died this year at age 111!

This beautiful woman was one of the master weavers in Sudaji village. Her name was Dadong Sentari. She mastered various weaving techniques, such as endek (ikat) and songket (double ikat or two-sided ikat), and memorised a multitude of traditional patterns packed with symbols and anecdotes. She died this year at age 111!Many crafts traditions are endangered worldwide. They are taught throughout generations – from hand to hand. And, if the livelihood of artisans is threatened – as it is today due to the overproduction of mass-produced goods that handmade products cannot compete with in terms of price – young generations will seek other kinds of employment (in Bali, typically in tourism).

Right now in Bali, the pandemic has emptied the island from tourists. But instead of feeling despaired, I am touched by experiencing the Balinese people’s incredible resilience: there is hope and there is desire to do things differently and to return to ancient ways and principles that always worked – to farm and grow and create. Furthermore, there is an openness to new ways and new ideas. This is a golden opportunity for balinese crafts.

June 21, 2021

Balance is the key to sustainable consumption

The focus of my research is always sustainable design and living. Recently I have been predominantly engaged in what a life you can sustain and justify looks like, feels like, is like. I have benefitted greatly from looking at sustainable living this way: if sustainable living essentially means living a viable life that is justifiable on a longterm basis ethics become an important part of sustainable living. And of course consumption or the usage of products and things is a part hereof.

I am often asked if I have any tips on how to be a sustainable consumer using the theories from Aesthetic Sustainability – and I am always reluctant to answering this question. Not because I don’t find it important, but because my main aim when I develop my theories is to encourage radical reduction of consumption of newly made things created from virgin materials. Nevertheless, of course it is important to discuss sustainable consumption (or, as I prefer to call it, sustainable usage) of products. Because even if we manage to reduce our consumption radically, there will always be a need for functional, aesthetically nourishing things in human life.

In Aesthetic Sustainability I have developed an aesthetic strategy in order to provide the sustainable designer with a tool to be used in the design process in order to ensure that aesthetic value is charged into the design object. The strategy is based on the balance between an aesthetic experience founded on the pleasure of the familiar or the pleasure of the unfamiliar. Both kinds of aesthetic pleasure provides the recipient with satisfaction, however in very different ways.

The pleasure of the familiar is based on boosting the user’s comfort zone and making her/him feel comfortable, at ease, and accommodated by providing her/him with an instantly decodable, subtle, soothing design experience. Design objects created in accordance herewith are typically based on functionality, convenience, and on delicate aesthetic nourishment expressed in details and tactility, as they have a “quiet” expression or a subtle idiom.

The counterpoint, the pleasure of the unfamiliar, is all about challenging the receiver: shaking up her/his world and idea of product-categories, and questioning (unsustainable) habits and unfortunate habitual ways of usage. Products within this category are typically comfort zone breaking by having a loud, intrusive expression, or by forcing the user to stop her/his daily routine and wonder for a while.

Notebook made from recycled cardboard and paper by Slinat

Notebook made from recycled cardboard and paper by SlinatThe reason I am bringing up these two different ways of working aesthetic sustainability into a design object in relation to sustainable consumption is that they are useful guidelines to have in mind when shopping for e.g. clothes or furniture.

I have things that are subtle and can be used for many occasions; things that are functional, comfort providing and make me feel cozily camouflaged. And I have things that are loud and expressive; things that challenge the way I wear and use everyday objects and that are vivid and colourful. The mix of these things is what makes it possible for me to reduce my consumption radically. The balance they create in my wardrobe and my home nourishes me and makes me feel comfortably full and satisfied.

So, I guess my best advice for sustainable consumption is creating a balance in our physical belongings: a balance between pleasurable familiarity and pleasurable unfamiliarity. Sustainable consumption advices often lean towards buying minimalistic, subtle, smooth things, as they can be mixed and matched with other things easily and can be used for multiple occasions. Furthermore the thought is generally that dim colours and a subtle idioms are longlasting because one doesn’t get tired of looking at them. And while that might be true to an extend (but only to an extend, because the boredom this leads to typically results in overconsumption of trendy, short-lived accessories that can spice up things a little), I think that underestimating the aesthetic nourishment that comes with roughness, vivid colour combinations and unconventional shapes and materials is wrong.

According to ancient Ayurvedic wisdom a complete meal that leaves you satisfied without a need for consuming more is a balancing act between all six flavours (sweet, salty, sour, pungent, bitter and astringent), and similarly a balance must be created between different “flavours” in our wardrobe and home in order for us not to feel unsatisfied or in a constant need for more. Balance is the key to sustainable consumption.

May 12, 2021

Uncultivated

I have started writing a new book. The working title is Uncultivated. The book is a celebration of rawness, wildness, “not giving a damn”-ness and of intuition and deeply felt empathy and connectivity. My youngest son lives these words, every day! But it seems that allowing oneself to be raw, authentic, and to live in deep connection with one’s natural surroundings and inner longings disappears somewhere along the path of growing up. My oldest son who is a teenager has already lost a big part of it, and my inner raw child has more or less completely vanished.

This book is inspired by my youngest son’s behaviour, anecdotes and insights. Not that he is any wiser than other children, not that he is any more special than other children (well of course to me he is), but because all children have an inherent sense of authenticity and mindfulness.

At this moment of writing he is 7 years old. He is still very much a child and still very raw and in-tuned with his intuition and his surrounding world. Especially his way of being with and around animals is a manifestation of his rawness; I actually don’t think he views himself and them as being separated.

But I am already starting to sense cultivation sneaking in; it shows itself in sudden self-awareness or in self-doubt and it colours his stories and experiences.

Being cultivated is interlinked with being educated, refined, sophisticated, enlightened – but also with being civilized, disciplined, well-behaved, neat and tidy, sociable, polite, nice, or even polished and formal.

But what is the opposite? Synonyms for uncultivated are words like uneducated, simple, uncivilized and primitive. The uncultivated human being is raw, unpolished, or even barbaric and crude. The uncultivated is associated with something shapeless, uncontrolled, and wild.

Does education thus imply being molded, formed, created? Are we initially shapeless lumps of clay?

There is a degree of unpredictability in being uncultivated. Maybe that’s why most synonyms for uncultivated are negatively charged or connote something savage. Maybe it is raw spontaneity that we wish to eliminate by cultivation, by refinement?

But something is lost in the cultivation and smoothening of all things raw. Something important that becomes obvious to me when I watch my son jumping out of the door ready to embrace yet another day in his own raw, “no damn given” kind of way. Something that is connected to vitality and to deep, innate joy.

Not that all cultivation is bad. Not at all. As Erik Fromm so rightly writes in Escape from Freedom: society doesn’t only have an oppressive function (but it does have one!, says Fromm), it also has a formative function. The only way to avoid oppression however, and to embrace creative, construction formation and socialisation is to enter into a spontaneous, free relationship with other human beings and with nature – a relationship that connects us with our surroundings without destroying our integrity.

[image error]The book is divided into ten sections that discuss the “truisms” or commandments of cultivation. The ten commandments of the late-modern cultivated individual are:

Being uncultivated is the antithesis to these commandments.

The following is a short extract from the book.

Decay must be defeated

He finds a large dead butterfly in our bedroom. It is laying on the floor with sparkly beautiful bluish wings. It hasn’t been dead for long. He’s excited. Can you believe that it chose to die right here, Mum? he says with radiant eyes. Isn’t it incredible that we get to see it like this before the ants start to devour it, I reply. Yes! He is happy. Wants to get paper and crayons and draw it. I want to see when the ants eat it, he says, I want to see it disappear.

The other morning a large cocoon that had been stuck to our bathroom wall for some time was empty; the brand new butterfly had left it. Such are the cycles of nature: flora and fauna change, decay, and perish. The beauty and magic of nature lies in many ways in these changes and in decay. The changing light of the sky; thunderclouds that drift in and darken everything, and rainbows that for short moments create above-ground coloured streaks, fog that eases, rain that gets denser and heralds the coming of autumn, fruit that when it is most ripe and aromatic is on the verge of rot, the perfumed scent of hyacinths culminating just before they wither, leaves withering and turning to soil and nourishment for other plants, bubbling spring-announcing buds: all a still life and landscape painters’ favourite motifs. Why? Because change holds the possibility of seeing and understanding; contrasts and contradictions are prerequisites for insight – and within decay lies the seed for something new.

Decay and perishability, however, are not exactly favourite themes in the life of cultivated, modern human beings. These elements of life are fought and denied, polished and smoothed. The consensus seems to be that the ravages of time are disfiguring. But against time we stand defeated. And by insisting on immutability and smoothness, we act against one of the, in my perspective, most liberating and uplifting “truths” of all, namely that everything is always changing: that the only constant in human life is change. To me, these sentences are liberating because they contain dynamism, movement, and vitality. They are the antitheses to the stagnant and static. Not because there is something wrong with a certain degree of stagnancy, stillness or anchoring in one’s life, not at all; but because if one convulsively clings to the status quo and opposes the natural course and traces of time and the currents in one’s life, one risks overlooking the beauty of allowing oneself to float, openly and freely. And furthermore, one overlooks the beauty of the raw and the weathered; of the beautifying traces of usage on a beloved object. Never allowing oneself to get carried away and let go of control creates blockages in one’s life: my son knows this instinctively, and every single day he lets go and floats along and away, which creates enormous amounts of presence and creativity in his existence.

I will be sharing more about the book on Instagram in the coming months. Feedback and comments are received with gratitude!

March 10, 2021

Anti-trend Research

Trends have always fascinated me. Why does something suddenly become trendy, fashionable, in? Why do style ideals change, often radically; from one extreme to the other? Are our aesthetic preferences that volatile, or are the ever-changing winds of trends to a greater extend caused by our longings and dreams?

Trend forecasting is based on predictions, and such predictions are often based on trend spotting: simply put: I spot an increase of patchwork jackets in the streetscape and hence conclude that the next trend will be patchwork garments. However, often new trends are simply reactions to the ‘mainstream’ or superficial cravings for newness in whichever shape this might come. This mechanism might leave one wondering; which came first: the chicken or the egg? Are the big trend forecasting agencies predicting or creating the future demands?

The reason for me to be focusing on anti-trends rather than trends is that trend-research tends to just scratch the surface. Trends are occupied with what, whereas anti-trend research is an understand of why. Anti-trends are an embodiment of the deeply felt longings for whatever constitutes the good life. Trends are fleeting and expressions of momentary likings, whereas anti-trends reflect underlying values.

If you spot a need for patchwork clothes and draw the direct conclusion that it would make sense for fashion clothes manufactorers to produce a manifold of patchwork apparels, you might miss the important fact that the spotted patchwork trend could be a manifestation of a deeply felt longing for the handmade and unique, for DIY and raggedness. And hence, producing stacks of identical patchwork jackets would be a failed attempt to accommodate these desires.

Trendy design products seek to accommodate current longings and fleeting desires to fit in, whereas anti-trendy design solutions meet long-lasting needs. Trend research leads to an understanding of current possibilities, whereas anti-trend research focuses on innovative future thinking – by digging deep down below the surface and by continuously asking ‘why’: why these style-ideals, why these longings, why these preferences? Why are we reacting like this to current affairs – and how will it affect our future concept of what living a good life worth sustaining might look like?

When engaging in anti-tend analysis I would under ‘normal’ circumstances (meaning pre or post pandemic times) be talking about slowness, about a growing desire for contemplation, for going off-grid and off-line, for locally grown, made and sourced foods and goods. Because the rule of thumb when working with the research of longlasting tendencies or anti-trends is that they emerge out of what we are missing in our lives. They come from deeply felt longings. Therefore, if we feel stressed out, overworked and overwhelmed and primarily use Netflix and sugar-rushes to get recharged, and if there is rarely time for slow cooking, good conversations with friends nor energy for reading and other mindful ways of revitalisation, then slowing down tends to become our image of the good life.

However, the usual themes of our time have changed over the past year. We are no longer longing for alone time, and we are no longer craving silence. We are isolated and restricted in a manifold of ways. There is still a need for off-line activities, as a matter of fact I think this need has grown, while it has also changed slightly. All the many zoom meetings and online classes add to the need for off-line gatherings and real life activities. And this need manifests in for example a growing gardening-trend; the need to yin-yang the many hours in front of a screen is being expressed as a desire to get one’s hands dirty, to grow something living, to touch, smell, and breath, to be outside. Preferably together with other people. And, the longing for being out there, in real life, with a group of likeminded, three-dimensional people is wood on a fire that was already smoldering before the pandemic, namely the off-grid tendency that is embodied in anything from home-schooling groups to off-grid retreats.

But another tendency is appearing due to the current (pandemic infested) longings as well. Cultural tendencies based on deeply felt needs tend to be manifestations of what we are running low on. And, at the moment most people are running low on a many things: off-line activities, as mentioned, but also touch/tactility, rawness (as a counter-pole to the smooth and sterile), face to face interactions, and also travels, adventures, partying and fun! I think that the pandemic-hibernation will lead to a exotic-far-far-away mega-trend that might reveal itself in a focus on traditional crafts and indigenous patterns in sustainable fashion, a need to eat food from all over the world (at home, now that travelling has become so troublesome), and hence new innovative samplings of locally sourced groceries and dishes from far-away exotic corners of the world, community dinners in the streets and the forests and parks, and many many more sharing concepts, since sharing is caring, and caring is love, and love is needed in these mask covered odd times, and for many years to come.

Slow Corona might reinforce the Slow Movement, but in a new way; it will foster a need for joy, freedom and community-experiences. As a sustainable designer, ways to check in to this tendency will be needed.

February 2, 2021

Anti-trend – and thoughts on being connected

It has been a very quiet period here at The Immaterialist, because I have been busy finishing the last chapter of my upcoming book with the title Anti-trend–Resilient Design and the Art of Sustainable Living. However, now I am done: the writing process has ended, beautiful photos have been obtained, the manuscript has been sent off to my great new publisher, and a good friend has created the most beautiful illustration for the cover (I can’t wait to share it all!) – and now the proofreading, editing and layout phase has begun. The book will be published around June. Much more hereon later.

My new writing project revolves around rewilding and connectivity, and is inspired by my youngest son and his very intriguing statements on human life, nature and interconnectivity.

I want to share my introduction to the project:

“My youngest son has an inherent sense of connectedness with his natural surroundings. He lives, navigates and learns this way. He moves and acts with a certainty that I envy: he seems convinced that we are an integrated part of nature, that human beings and nature are interconnected, and that talking about humans and nature as being separate doesn’t make any sense at all. He will say: “what we breathe out the trees need to breathe in, and what the trees breathe out we need to breathe in”, or “those fluffy clouds you see right there, mum, are there because a new baby was just born”, or “today the waves are really big because a lot of people died”. Such statements are made with a confidence that usually leaves me speechless. They are so natural and such an incorporated part of his being that he doesn’t think much of them; it is just the way things are. He will walk barefooted whenever possible (which to him means most of the time); he despises shoes; “when I wear them, I can’t feel anything”, he says. He often talks of his spirit-animal, which he says is the eagle. He says that he can always feel when an eagle is close by, which he has demonstrated on several occasions by suddenly saying “look” and pointing up, and sure enough an eagle is majestically floating around above us. My biggest fear is that he, like I did, will unlearn these truths and inherent sensations as a part of his “cultivation” and his education. Because I, unlike him, don’t feel particularly connected to a specific animal, and I, unlike him, have forgotten the feeling of being completely safe in wild nature.”

I look forward to sharing more on this project, as it progresses. Currently I am engaged in research on indigenous wisdom and wild schooling.