Kristine H. Harper's Blog, page 4

April 5, 2023

Democratic sustainability

Around a year ago I spoke at a design conference. I spoke about aesthetic sustainability and the importance of investing in durable things: things that last, both functionally and aesthetically. And, I spoke about how decay at times can beautify an object; how wear and weathering can increase the value of a well-made piece of furniture or clothing.

There was a question from the crowd: “What if you cannot afford to invest in a well-crafted table that ages with beauty?”

It was a good and relevant question. Because despite the fact that investing in durable things that can last for decades and continuously nourish us aesthetically is probably the most affordable and reasonable in the long run, this is not an option for everyone.

Sustainability has become the new luxury.

Creating durable design objects is time consuming, and of course the pricetag should reflect that. However, this means that investing in durability is not a possibility for everyone, and that sustainable consumption tends to increase societal inequality.

Living sustainably ought to be the most reasonable and the most natural way of life. Mending, reusing, recycling, sharing as well as eating local groceries are all examples of activities that are at the core of sustainable living, and that are furthermore affordable, unpretentious, and accessible. So why is sustainability associated with luxury and exclusivity? Why has sustainable design and sustainable living become status symbols and ways of expressing wealth and sophistication?

Looking back in history, basic approaches to sustainable living are countless: prolonging the life of things, repairing, reinforcing, preserving, conserving, communally consuming, sharing, crafting, gardening, locally sourcing, composting, following the cycles of nature and seasons etc.

However, despite repairing, reusing and recycling being both affordable and accessible ways of life, they don’t seem to be vastly common. As a matter of fact, the least well-off seem to be the least engaged in such sustainable (and affordable) activities.

Why?

Well, in order to be able to repair one’s belongings, these belongings must be repairable. And generally cheap mass-produced goods are not. They are produced to be obsolete after a short period of usage. Fast-fashion products for example are typically made from composite and/or artificial materials that cannot be patched or mended in a way that doesn’t leave unflattering spots on the fabric-surface, and furthermore they, per definition, adhere to fleeting trends, which make them appear outmoded after a short period of time.

Similarly, cheap toys, home accessories, kitchen utensils etc. wear out and get damaged in ways that make them hard or maybe even impossible to mend. They are made from flimsy materials that break easily, and they are cheaper to replace than to repair.

Aligned herewith, the cheapest foods are mass-produced fast foods; and such are typically wrapped in plastic and Styrofoam, produced in manifolds in large food factories and often transported across the world, and as such they are obviously not the most sustainable products.

Sustainable design-objects as well as ecological, sustainable foods on the other hand are created and produced to be expensive; they are made and branded to be yet another traditional status-symbol, or yet another way to express wealth. And so, even though living sustainably should and could be the most reasonable and natural way of life, it is out of reach for the vast majority of people. Hence sustainability has become pretentious, elitist, and for the fortunate well-off and well-informed few (who tend to increase the division further between sustainable and unsustainable living by sitting “on their high horses” pointing fingers and says: “oh my, I cannot believe they don’t know any better than to act, shop, eat, drive, travel like that”).

Sustainability has become a way to separate the wheat from the chaff. It is an extremely effective example of storytelling that profits from righteousness and class-divisions (and hence creates an “us” and a “them”). There is no community-feeling in luxurious sustainability.

Designing cheap products meant for short-term usage out of materials that last for a very, very long time, maybe even for hundreds of years, and that whilst breaking down slowly emit polluting gasses is actually kind of bizarre. Despite this being common practice, it is a flaw.

How can designing e.g. flip flops out of imperishable foam rubber have become custom? And, why is creating trend-based stuffs that are intentionally made to be fleeting out of resource-demanding natural materials like cotton or hardwood, or out of synthetic materials that cannot deteriorate naturally, like polyester, nylon, rayon or polyethylene, considered business as usual? If you think about this in a logical manner, designing something for short-term usage out of materials that can last for (more or less) ever is erroneous and should be considered a design error.

Unless sustainable solutions are made accessible to the vast majority, unless sustainability is inclusive rather than exclusive, unless sustainable living is the norm rather than a branded lifestyle for the privileged few, well then the ability to embrace a sustainable lifestyle will remain yet another way of increasing the inequality gap between populaces.

Overcoming that gap requires affordability, accessibility and repairability; sustainable design solutions should ideally be created to be egalitarian rather than elitist. Of course, slowly crafted objects are more expensive than mass-produced goods (and rightfully so), and of course innovative design solutions created with the purpose of encouraging sustainable living often require massive material and technological research and development, which initially makes the outcome costlier than conventional products. But creating affordable, enduring, repairable things is not impossible. Not at all.

However, democratising sustainability doesn’t only involve simplifying and optimising sustainable solutions in order to make them more affordable (even though this process is a part hereof). It also requires a change in habitual mass-consumption.

As long as mindless consumption is still the general norm, as long as discarding things when they are slightly worn out or broken is still the most common (and the cheapest) procedure, and as long as shopping is viewed as a reward for long work-hours, creating sustainable design solutions that encourage reduced consumption, challenges use-and-throw-away-habits, and favours repairs is a task that is not solely linked to affordability.

Democratising sustainability requires a mix of accessible, affordable, durable and repairable things and a mass-consumer culture that favours longevity and creative mends.

All photos are from my newly started democratic (meaning affordable, ethically produced) sustainable luxury brand illusi. Follow along on instagram: we are launching products and workshops soon.

April 1, 2023

Find me a ring with the power to make a happy man sad and a sad man happy

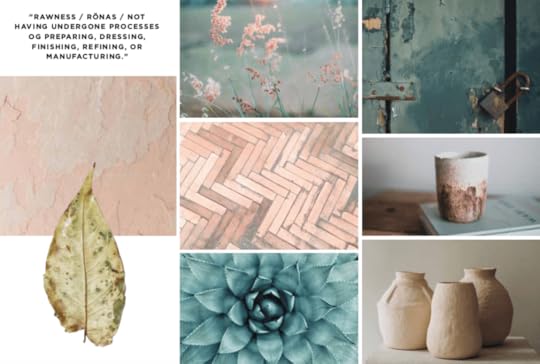

The most resilient design-object is characterised by a degree of rawness and wildness, and as such it is impermanent!

Now, this statement might sound a little odd, as we usually associate resilience with hardiness and durability, which are synonymous to permanence. Nevertheless, the most resilient object is impermanent in the sense that it embraces impermanence and changes.

No matter how we look at resilience and sustainability, designing an object that is meant to be durable by focusing on permanence as something that is fixed, static, or non-changeable makes very little sense. An object that is fixed, totally completed when released into the world, is not created to be used. However, the user phase is crucial in order for an object to be durable. If all usage does is add to the unflattering decay of the object, the user will soon be longing for a new perfectly permanent object to replace the old one.

Design-objects should be designed to nurture and accommodate human life. And in order to make this happen, we can beneficially consult nature for advice on how to rethink the idea that designing permanently stagnated objects is the way to create durable, sustainable things. Nature is governed by transformations, evolution, changes, decay, decomposition, and rebirth.

Change is the only constant, not only in nature but also in human life.

Designing inflexible, stagnated objects seems like the wrong approach if the objective is to enable and encourage sustainable living. The pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus is known for having said that no person ever steps into the same river twice, for it is not the same river and he is not the same person. Everything around us and inside us is always in flux. Our days are filled with changes: atmospheric and physical changes in our surroundings; mental and emotional changes in our minds; and physical changes in our bodies.

I heard a Jewish folktale from my yoga instructor that portrays this well.

It goes like this:

“King Salomon once lost a chess game to his most trusted advisor, Benaiah Ben Yehoyada. Being a bit of a bad loser, King Salomon decides to teach Benaiah a humbling lesson by assigning him an impossible task: to find him a ring with the power to make a happy man sad and a sad man happy. Benaiah is given half a year to produce this magical ring. He searches in every corner of the kingdom, but to no avail.

Just as he returns to face the king and admit his failure, Benaiah stumbles into a small and dusty workshop tucked away in a little alley not far from the castle. After one look at the inside of the little store, Benaiah disappointedly turns around to walk away. It is impossible that this goldsmith will have what not even the most famous goldsmiths in the kingdom have ever heard of.

In this moment, the owner — an old and frail man — approaches him and asks how he might help him. Benaiah sighs and shares his quest for a ring that possesses the power to make a sad man happy and a happy man sad. The old goldsmith smiles, nods, and says he might just have what Benaiah is looking for. Stunned, Benaiah waits patiently as the old man rummages in the back of his store.

After a short while the goldsmith returns and hands him an unassuming gold ring. Inspecting the ring, Benaiah discovers an engraved sentence on the inside. Benaiah reads the sentence and his face lights up. He pays the old goldsmith handsomely and hurries back to the castle.

King Salomon watches him approach, looking forward to Benaiah’s admittance of defeat. With a knowing smile Benaiah hands Salomon the gold ring. Salomon frowns, turns the ring in his fingers, and finally detects the engraving.

He reads: “This too shall pass.”

Salomon, in his wisdom, sees that this ring contains the truth. Life is impermanent and everything will pass.”

Yes, life is indeed impermanence, and everything will pass — not least of which, our situational needs and desires. Designing for permanence, for immovability, for fixedness makes no sense, especially not if the goal of the design process is sustainability and resilience.

In nature, an organism must be adaptable in order to survive; it must be able to adjust to new environments or to changes in its current milieu. There are creatures that develop resistance to the venom of predators who hunt them, mice that grow immune to poison — or lice for that matter; I have excessive experience with these little unbelievably resilient critters here in southeast Asia.

There are plants in deserts that develop their stems or leaves to store water in periods of drought.

Human beings are also naturally adaptable to the environment that they live in. People who live in high altitudes — such as Tibetans — have adapted to living with oxygen levels up to 40% lower than at sea level.

The Moken people of the Andaman Sea have eyes that have adapted to see more clearly under water by being able to decrease the pupil-size and change the lens shape — a trait also seen in seals and dolphins. The Moken even go so far as to train their eyes — exercising these skills in their children from when they are babies.

The Swedish scientist Anna Gislén spent three months with the Mokens in 1999, and during that period she investigated their unique underwater vision. She discovered that while non-Moken children — Gislén included a group of European children who were on holiday in Thailand in the research process — were able to train underwater acuity to a degree, the Moken children still had a genetic advantage and their eyes were not irritated by the saltwater as was the case for the European children’s eyes.

In accordance with natural growth and evolution, design solutions should be evolutionary and adaptable in order to be sustainable. Because how can anyone possibly foresee future needs or situations?

The aesthetically resilient design-object embraces change and impermanence by being adaptable and by inviting nourishing, meaningful rhythms into the user’s life. Rhythms that celebrate the changes in life, the diversity and irregularity of materials and resources, and the asymmetry and wildness of raw beauty.

Photos:

Handwoven textiles from Lombok. I am starting a company called illusi with my friend Maya with the purpose of sustaining endangered crafts in Indonesia (primarily textile-weaving and the creation of natural textile dye), upcycling waste materials, facilitating workshops, and creating empowering opportunities for local artisans.Please follow along on Instagram! We are launching mid-april, but the account is already up and running – and there are a few beautiful photos of the amazingly talented weavers in Lombok we are collaborating with.More beautiful handwoven textiles from Lombok. The vision of illusi is to create affordable, aesthetically sustainable textiles and garments charged with time and made to embrace decay and user traces. That (in my opinion) is the ultimate design-flexibility and an ode to change.My beautiful Marius snorkeling by Nusa Penida.

February 22, 2023

Interview #12: Meet Margarida from Seeds & Stories

It has been a while since I have done an interview here on The Immaterialist. But now I am finally ready with a new talk with an incredible, inspiring human being: Margarida from Seeds & Stories.

Read about how the company was started, about regenerative agriculture, building bioregional textile communities, the importance of women’s empowerment, and about the profound and inspirational visions Margarida has for the future of Seeds & Stories.

Read also about how you can support the project and get engaged in sustainable entrepreneurship.

I hope you will enjoy!

***

What does sustainability mean to you?I have to say regeneration means more to me than sustainability. I believe we have reached a point where sustainability is no longer enough. Hence, rather than doing less harm and mitigating the negative impacts of our actions and choices, we should focus on amplifying positive impacts and making things better for all people, mother nature and future generations.

Regeneration, for me, is about healing. It is about restoring a healthy and mutually beneficial relationship between people and nature, increasing the prosperity of human and natural systems. It is about implementing solutions that have multiple benefits to the natural world and people in an integrated, reciprocal and long-lasting way. Ecological health, meaningful livelihoods, food security, socio-cultural vitality, quality growth, greater resilience, diversity, and fairness. In a nutshell, for me, regeneration is all about improving the world from how we found it, and to do so in perpetuit

***

Tell us about your journey with Seeds & StoriesLet me go back in time so you understand where the idea and inspiration come from.

I have been an advocate for women’s rights and empowerment since an early age but ended up working for 14 years in Westminster as a political/legal researcher. I was unhappy with my job for a long time and started looking at ways of making a real, long-term, positive impact on people and the planet, making the world a better place while bringing meaning into my life. My journey towards a more sustainable life started ten years ago when I became vegan. I started being more aware of the impact of my choices, from food to fashion, on people and the planet. I progressively started changing my lifestyle and making more conscious choices. I started travelling for a purpose, visiting and supporting women’s groups and local artisans; I completely embraced community-based tourism. The work of the women groups and social enterprises I visited around the world and the difference they can make to the women they work with and with little resources certainly inspired me to launch my social enterprise.

The Fashion Revolution further opened my eyes towards the negative impact of the fashion industry on people and the planet. It empowered me to make my contribution towards a fashion industry for good. Then I came across Fibershed and Rebecca Burgess’s book, Fibershed: Growing a Movement of Farmers, Fashion Activists, and Makers for a New Textile Economy, which had a massive impact on me. I became fascinated by the regenerative movement and wanted to learn more about how we can make the world better by applying nature-based solutions. I even took a Permaculture Design Training course. Needless to say, Seeds & Stories is greatly inspired by the Fibershed.

Why Uganda?

Well, in 2018, I visited Uganda as a community-based tourist. I had the opportunity to visit several women’s groups and learn more about the difference they were making to local women. I spent some time in Bigodi and fell in love with the village and its people. I had a wonderful time with Tinka’s family, who introduced me to Stella, a local artisan. Stella showed me a few basket-weaving techniques and shared her knowledge of local natural dyes. Stella is now the chairperson of Seeds & Stories’ women’s group. During this time, I also learned about the economic, social, and environmental issues women in Bigodi face.

In 2020, the time had come to change my life and follow my passions for women’s empowerment and my commitment to making fashion force for good. Brexit happened, and I lost my job and didn’t miss the opportunity to finally change my life and career and focus on what matters to me. The idea for Seeds & Stories started developing. I approached John Tinka, the founder of The Kibale Association For Rural and Environmental Development (KAFRED) and Betty Tinka, the chairwoman of Bigodi Women’s Group, with whom I stayed in 2018. I shared my idea for a women’s social enterprise in Bigodi, which they loved. They conducted a survey of local women regarding their interests, challenges and aspirations. The survey demonstrated that they had identified a lack of sustainable income as their biggest challenge and demonstrated a strong interest by local women in being involved in a new income generating project.

Obviously, during the pandemic, I could not travel, but I managed to travel again to Bigodi in the summer of 2021. I met with a group of local women who confirmed the urgency to develop income-generating alternatives outside mainstream tourism. I thoroughly explained the project, its aims, values and activities. They welcomed and showed their willingness to be part of Seeds & Stories. In fact, they didn’t waste time setting up an executive committee and electing their chairperson, Stella.

Seeds & Stories was officially launched in September 2021, when our constitution was unanimously approved and we registered as a community-based organisation. By talking to local conservationists, I also learned that there was also a strong need to revive traditional farming methods. I spent one month in Bigodi and used my time there to get to know the women and the community better, and also to teach them embroidery. I encouraged them to use their creativity and traditional craft-making skills to create new products. I encouraged them to support and learn from each other. It was wonderful to see their confidence progressively growing.

Seeds & Stories enables me to move my values forward; it combines my passion for women’s empowerment, craft making, and regenerative fashion. It allows me to make a real difference for women in rural Uganda, contributing to gender equality, social justice, climate justice and environmental regeneration.

Seeds & Stories is a women-led social enterprise based in Bigodi, a rural village in Western Uganda, that uses circular fashion as a tool for women’s empowerment and environmental regeneration. Seeds & Stories is developing slowly, but steadily. It was only in the summer of 2022 that we started creating products, after we finally got funds that allowed us to provide training in product development to our group of artisans.

We aim to create quality artisan-made, soil-to-soil products that support the livelihoods of women artisans in Bigodi and can be returned to Mother Nature at the end of their life-cycle. We source and produce locally. We use what is locally or regionally available to make our products: Bigodi is rich in natural fibres, and we only use local fibres indigenous to the region, such as palm leaf, papyrus, banana fibre (agricultural waste) and marantacloa. Likewise, we only use natural dyes, a combination of foraged plants, leaves, seeds, roots and rainwater to dye our natural fibres.

It is a fascinating journey to work with the Seeds & Stories group of women and learn more about local natural fibres and dyes, and about what we can create with them. I have learned a lot from them, but also shared my knowledge on natural dyeing, eco-printing and natural ink making. Working alongside other community-based organisations, such as Kafred, I am doing my best to empower the community to embrace the circular economy and regenerative practices, and to revive traditional ways of doing things so they can work with nature, not against it.

After five hardworking months, we were able to develop six products. I am incredibly proud of all our artisans and team and what we have achieved so far. It has been a long and challenging journey, but a super rewarding one.

All our products are 100% made in Bigodi in harmony with nature. Our group of local women artisans use traditional techniques passed down through generations, such as basket and mat weaving, to make our unique, soil-to-soil handbags. Some products take around two weeks to complete, and hence, it is challenging to sell them at a fair price in local and national markets. What people expect to pay is not enough to cover the amount of work, time and dedication of our artisans.

Seeds and Stories is a non-profit social enterprise. Selling products will make us financially sustainable, pay wages, training, materials or tools, and invest in community projects. Well, we just started selling, so hopefully, soon we will find customers that love the products and appreciate what we do, thus willing to pay a fair price.

Since starting this journey, I have met many like-minded, inspirational, impactful people like yourself, Kristine. It has been a joy to meet, exchange ideas and join forces with people and organisations with the same values and principles. I am also honoured and grateful for all meaningful connections and partnerships with other community-based organisations and social enterprises in Uganda.

***

What are your visions for Seeds & Stories?Seeds & Stories’ vision is to support rural communities to become more resilient and self-reliant, healthy and equitable by providing them with the necessary skills, resources and facilitation. We aim to achieve financial sustainability within three years by selling our products. I furthermore hope that our impactful products will allow us to offer training programmes and employment to an increasing number of women artisans, providing them with a regular income and sustainable, meaningful livelihoods and enabling them to lift themselves out of poverty through work that values their skills and culture.

I strongly believe that by switching from conventional agriculture to regenerative farming we can turn problems into solutions. Regenerative agriculture has the potential to create a range of environmental and social co-benefits: soil restoration, increased biodiversity, improved water cycles, maximised community resilience, environmental regeneration, and livelihood enhancement.

We want to produce soil-to-soil products that create social and economic opportunities for local women and positively impact communities, animals, and the planet. Hence, we have set a goal only to use local raw materials that have regenerative properties in local ecosystems, namely increasing soil fertility, enhancing biodiversity and increasing the rate of carbon sequestration from the atmosphere into the soil, contributing, in this way, to climate change mitigation.

We want to buy a piece of degraded land and transform it into a permaculture demonstration site. This site will allow the local community to learn about regenerative agricultural practices that will help build community capacity in the future. Hereafter, we wish to build a workshop run by renewable energy, with rainwater harvesting and wastewater treatment systems. Having our own space, a permaculture-designed farm will allow us to put in place effective and efficient production processes that generate no waste, reduce water usage and run on renewable energy. It will enable us to design, create and sell products in a closed loop incorporating innovative and creative solutions to regenerate natural resources.

I am absolutely fascinated by bioregional textile communities and ‘soil to soil’ fashion and textile systems. Bigodi is rich in natural fibres, and we want to explore what community-led bioregional integrated systems of natural fibres, natural dyes, and food growing could look like in Bigodi. I believe, in this way, we can play a more active role in restoring ecosystems, regenerating natural resources, creating meaningful and sustainable livelihoods and helping build resilient communities while advancing gender equality.

We hope, Bigodi can serve as a pilot project which can be adapted to other rural communities in Africa.

***

How can people help your project grow?Ohh, people can help us in many different ways. First of all, by buying our products – if they love and need them, of course.

If you purchase Seeds & Stories products, you make a meaningful and positive difference in the lives of women in rural Uganda by helping us creating jobs, more economic opportunities and meaningful livelihoods while having a positive impact on the environment.

You can also help us moving forward with our regenerative journey by contributing with advice and spreading the word about us. You can follow us via our website, on Instagram, and on Linkedin.

By sponsoring an artisan, you can help us to continue to offer training and build up the skills of our artisan. We plan to provide our group of women and other farmers in the community with regenerative agriculture training. And we also want to offer literacy classes.

By making a donation, you can also help us immensely. Any contribution can make a difference to the women in rural Uganda and help us with our mission.

We are also always looking for passionate volunteers to help us out online or on the ground. So, if you love Seeds & Stories and support our mission and feel that you would be able to contribute in some way, please feel free to reach out.

***

What is your advice for entrepreneurs working with sustainability and women’s empowerment?To deeply engage with the communities you work with.

To build meaningful partnerships with women’s groups and other local organisations.

To listen to the beneficiaries and to involve them in decision-making. Listen, and ask lots of questions, and embrace people-centred approaches.

To respect and embrace the cultural and ecological uniqueness of places where you work. Start small, step by step. Stay faithful to your mission, vision and values.

And last but not least; to make sure you have a solid and dedicated team.

February 7, 2023

Here are (five of) the books that made my heart sing in 2022

Karl-Ove Knausgård’s (or Knausgaard for the non-Scandinavians) The Morning Star (I read in in Danish, therefore this cover-image).

Karl-Ove Knausgård’s (or Knausgaard for the non-Scandinavians) The Morning Star (I read in in Danish, therefore this cover-image).“In a strange way, what I read coincided with what I was. I read about the raging sea as the sea raged, I read about the whispering forest as the forest whispered, and when I read that to pray was not to speak, but to become silent, that only in silence could God’s kingdom be sought, God’s kingdom came. God’s kingdom was the moment. The trees, the forest, the sea, the lily, the bird, all existed in the moment. To them, there was no such thing as future or past. Nor any fear or terror. That was the first turning point. The second came when I read what followed: What happens to the bird does not concern it. It was the most radical thought I had ever known. It would free me from all pain, all suffering. What happens to me does not concern me.”

I admit it. I am a Knausgaard addict.

I have read everything the man has ever written and am a big fan of his six-volume My Struggle.

I was a bit late reading The Morning Star, because I refuse to read e-books, and books are not very easily accessible here in Bali (unless you like spiritual self-help books or books in the genre “how to make money without giving a f.. about anything and without working more than an hour a day”).

But at the end of the year, I finally got my hands on The Morning Star (thanks to my mother), and even in my Mother tongue Danish (bliss).

What a book. What a story.

The narrative takes place in the course of two days, and alternates between nine main characters, who all experience the rise of a huge new star in the sky.

There is an apocalyptic feeling to the story, and you sit back with a lot of unanswered questions. Is the feeling of a lurking evil an indication of a disaster about to happen? Is nature finally fighting back? In all the intertwined sub-stories the characters have encounters with animals acting in strange, unusual ways: flocks of crabs migrating from the sea into the forest, an eagle attacking a sparrow eating crumbs from a cafe-table in the middle of the city, a racoon appearing in a living room, a deer approaching a parked car maintaining eye-contact with the amazed driver for long minutes, huge swarms of ladybirds filling up a terrace… The weather is also abnormal; unusually hot and moist, and the Norwegian fjord is turned into a nearly tropical setting.

The Morning Star is a grand novel about life and death, about nature and human relations, about mental health, loneliness and immense beauty, and about embracing the things we don’t understand and cannot explain.

***

Another book that made my heart sing in 2022 is Richard Powers’ most recent novel Bewilderment. You might know Powers as the author of The Overstory, the incredible saga of human interconnectivity with tress.

Bewilderment is the story of a father (Theo) and his 9-year old son Robin (or Robbie as his father calls him), who have lost their wife/mother and are trying to navigate the world and get on their feet again after their loss.

Robbie is a very emotional boy, who is in almost every way different than the majority of his 9-year old peers (his teachers would like him to get a diagnosis, so that he can be medicated, but his father Theo refuses). He is bullied at school and gets expelled for smashing his friend in the face, after the friend makes an unkind comment about his deceased mother. This leads to Theo taking him out of school and homeschooling him. Theo is an astrobiologist searching for life throughout the cosmos, and Robbie ends up spending most of his days at Theo’s lab.

Robbie is a dedicated vegan suffering from eco-anxiety, who again and again and engages in fundraising projects to safe endangered animal species. There is a heartbreaking beauty in seeing the state of the world through the eyes of an emotional, hyper-sensitive 9-years old.

Powers explores in Bewilderment the idea of an empathy-machine that allows you to feel what other people feel; and actually not only other people, but with all living beings. This thought experiment raises questions like:

What if human despair and the appalling ecological state of the natural world are related?What if we could feel what pigs felt, or what it would feel like to be a bird or a dog or a horse — would we then be more empathetic towards these beings?And what if we could feel what it felt like to be another person, would we then be kinder, more focused on kinship and connectivity rather than on competition and rivalry?I have a great idea, Robbie said. Dr. Currier’s lab could take a dog. A really good dog. But it could also be a cat or a bear or even a bird (…)

Take a dog and do what, Robbie? His thoughts these days often grew richer than he could say.

Take him and scan him. Scan his brain while he was really excited. Then people could train on his patterns, and we’d learn what It felt like to be a dog. (…)

Robbie was right: we needed universal mandatory courses of neutral feedback training like passing the Constitution test or getting a driver’s license. The template animal could be a dog or a cat or a bear or even one of my son’s beloved birds. Anything that could make us feel what it was like not to be us.”

The idea of an empathy machine that can allow us to feel what others feel — even animals and plants — is a beautiful philosophical experiment that explores what is needed the most in the world right now.

Perhaps the solution to some of the big problems we consensually facing; pollution, animal and plant species going extinct, cultural blandness due to globalisation, homogenisation, inequality, racism, sexism, chauvinism, terrorism etc. etc. is to be found in fostering and cultivating our “soft skills”, like the ability to feel empathy and be compassionate and kind, to be intuitive, and to feel love and experience beauty?

Ever since I read “Bewilderment” I think of the book when I look at the night sky from my jungle house.

Ever since I read “Bewilderment” I think of the book when I look at the night sky from my jungle house.***

The next book on my list is a re-read for me. It’s one of my “bibles”, and it is written by one of my heroes: Existentialist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir. The title of the book is The Ethics of Ambiguity.

“The notion of ambiguity must not be confused with that of absurdity. To declare that existence is absurd is to deny that it can ever be given a meaning; so to say it is ambiguous is to assert that it’s meaning is never fixed, that it must be constantly won. Absurdity challenges every ethics; but also the finished rationalisation of the real would leave no room for ethics; it is because man’s condition is ambiguous that he seeks, through failure & outrageousness, to save his existence.”

This is one of the books I try to re-read every couple of years. It beats the living daylights out of any self-help book, ethical treatise, or spiritual essay, and it is furthermore immensely relevant to today’s discussions on climate, sustainability, (in)equality, and welfare.

In de Beauvoir’s existentialist philosophy, alike Sartre’s and Kierkegaard’s, human development toward authenticity and true freedom is described as a progression through a range of stages (from the least free to the most). In her terminology: from the sub-human to the passionate human.

De Beauvoir declares in The Ethics of Ambiguity that being free is not the equivalent of being able to do whatever you want whenever you want. Rather, true freedom involves embracing the transcendence of existence (as abstract as this might sound). And this movement most certainly doesn’t include the oppression of others; it is its antithesis. As a matter of fact, the existence of other free individuals is the very condition of one’s own freedom.

This point can beneficially be drawn into today’s capitalistic consumer reality. If suppressing others — whether this be directly or indirectly — makes you unfree, you are actually acting against your own freedom when buying and consuming goods that you know are probably not produced in an ethical way. Products that you know are most likely produced by workers in an Asian sweatshop who are paid an astoundingly low wage, and who work long hours under horrific conditions in order for you to be able to wear the newest trendy fashion item at a low cost, or in order for you to buy weekly new plastic toys for your kids. Because let’s be honest: when we buy a cotton shirt for less than $10, a pair of shiny new shoes for $15, or a radio-controlled plastic car for $5, we know that in order for this to be possible somewhere in the value-chain someone must have surely paid a high price.

When using others and compromising their freedom for your own gain, you are not truly free. To be free and to be able to obtain and consume whatever you want at the expense of others is to participate in oppression, no matter how we look at it.

Passion is an important part of genuine freedom, according to de Beauvoir — and one can only be passionate about something that one is sincerely engaged in. However, passion is only converted into genuine freedom if it is shared — or, if the object for the passion is “opened up” to others. One cannot be fulfilled if limited to oneself. Joy, and the desire to share, makes passion authentically free!

“If a man prefers the land he has discovered to the possession of this land, a painting or a statue to their material presence, it is insofar as they appear to him as possibilities open to other men.”

In order for us to “cherish the land discovered more than the possession of this land”, we must follow our path in life, and not obey cultural norms, must-does, and must-haves of others — even if this path requires a degree of civil disobedience or disapproving gazes. If not, the possession (or the status that comes with whatever one does or creates) rather than the object for our passion (or the land itself ) is the focus.

Meaning must come from within. The condemnation of freedom, which is substantial in existentialist philosophy, involves an obligation to act accordingly with one’s purpose as well as an involvement in the world.

Much more can be said about this book. I won’t say anymore right now. But it is, in my opinion, a must read.

***

I have also loved (!) reading a lot of Indonesian literature last year, especially Happy Stories, Mostly by Norman Erikson Pasaribu and Apple & Knife by Intan Paramaditha.

Thanks to my lovely friend, Indonesian poet Cyntha Hariadi (who’s lyric is unfortunately not translated to English — and as much as I try, my Indonesian language does not yet allow me engaging in poetry), I have been gently guided to this treasure chest of contemporary Indonesian literature — and honestly, there is so much to say that I will have to write an article just on each of these books. I will however dive briefly into Happy Stories, Mostly by Norman Erikson Pasaribu.

“If a friend invites you over for dinner, don’t turn them down like you’ve done before. Even though i’s your first chance to, don’t bring a date — you’ll look like you’re trying too hard. Bring a bag of mangos; wear a little red dress. When people ask for your timeline of events that led to your breakup, keep it short. Some popular responses: We both liked to read, but turns out you need a better reason to stay together. Or, His farting problem was unbearable. Don’t bother to lie about your supposed novel project if they don’t ask. They won’t really care.

(…)

Go jogging every morning. You need the endorphins and also quiet moments for yourself. Don’t bring your iPod. And don’t catch Pokémon. Turn all your focus inward. If you see any of your college classmates, say hi. If they invite you to run with them, say you’re happy with your current route. If they say, all right, they’ll join you, reply, “Perfect!” and laugh. Don’t sing to yourself while you’re running — they’ll think silence makes you uncomfortable. Respond to any remarks they make, whether political, pseudoaltruistic, narcissistic, or even poetic.”

This quote is taken form one of the twelve short stories called “A young poet’s guide to surviving a broken heart”.

The twelve novels are independent, but also intertwined (some of the characters and places recur), and all in a subtle manner occupied with gender and homosexuality in a culture where you don’t speak about such things. There is a moving, at times heartbreaking sensitivity to the tales of the characters trying to find their way in a world and culture that doesn’t accept them for what and who they are, or the charters who didn’t accept others (loved ones) for who they were, and are now living in denial and in an unspoken state of regret. Like the mother, Mama Sandra, in the story So what’s your name Sandra who decides to travel to My Son in Vietnam after her only son’s death (even though she has never in her life gone any where before). What appears to be a pilgrimage of sorrow turns out to be a crusade of regret; her son’s suicide is interlinked with Mama Sandra’s rejection of him after her finding out that he is homosexual.

The book is also extremely humorous and at times nearly surrealist. Like The True Story of the Story of the Giant in which a young man sets out to find a fabled giant in the mountainous Tapanuli region in North Sumatra after having heard of the legend of Parulian the giant from a classmate.

“After that, I roamed around North Sumatra for one and a half years, burning trough all my Big Java Vacation savings and loosing twenty-five kilos from trying to save money by eating only once a day. And then, out of the blue, in a village called Partonun, from the lips of a very old woman weaving ulos came a tale — a very short one — about Parulian. The woman told a story about a little boy who grew a full adult’s height every year, until he was as tall as a mountain and could speak with God”

I am going to have to re-read these short stories soon. Very soon!

***

Last, but not least, I have to also mention this incredible novel— despite it being in Danish, and not translated to English (which means a lot of you probably can’t read it, unfortunately). But this is one of the books that made my heart sing the loudest last year! Ohh my!

Josefine Klougart is a Danish novelist, and Alt dette kunne du få (which translates to something like: You could have all of this) is her sixth novel.

This beautiful novel is about interconnectivity between human beings; family bonds and breaks, friendships, sisterhoods, bonds of love, and about kinship between humans and nature; about childhood experiences of being at home in the natural world, about loosing that sensitivity, and about reclaiming it as an adult.

It holds descriptions of beauty experiences so intense and magnificent that it brought tears to my eyes. It is an incredible piece of literature, a piece of sublimity.

There were many other incredible books that I enjoyed in 2022, but these five are the ones that made a particularly strong impression on me

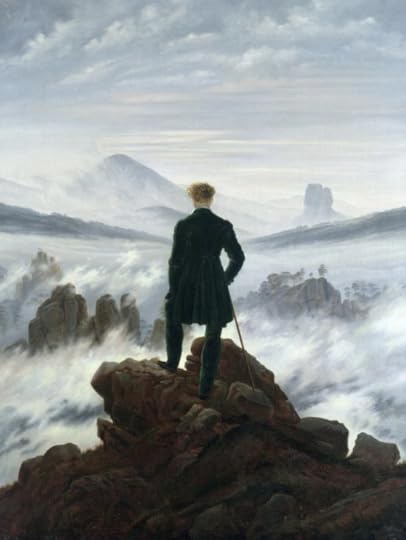

Reading a book is like a journey, is like an odyssey. Reading a book is a beautiful, slow aesthetic experience. Reading a book confirms the connectivity between human beings. Reading a book can lead to a deep sense of belonging and of being at home in the world. Reading a book can change stuck perspectives and allow for the river of life to flow.

Happy reading!

January 28, 2023

Sustainable storytelling

There is something wrong with storytelling on sustainability, and it is not only greenwashing. Most stories that are told don’t feel feel relevant – they just feel, well, insignificant. and on top hereof, their wording often feels a bit like the way you would speak when trying to get an unruly child to eat properly: lots of raised index fingres and lots of don’ts; no, no, no (tsk tsk tsk):

“Don’t use plastic bags”; “Don’t travel by airplane”; “Don’t buy fast fashion.”

There are rarely immediate alternatives provided, and the consequences of not stopping our plastic-bag use, fast airplane travel, fashion-based behaviour is linked to doomsday scenarios: starving polar bears, melting poles, an increase in earthquakes and other natural disasters like heatwaves and ice storms, etc.

To the common consumer, drawing a line between buying that trendy dress and wearing it only once before discarding it—or saying “Yes please” to that plastic bag to put tomatoes in in the supermarket and the melting Antarctic ice is—understandably—difficult. Relevance is the key word here. Relevance and applicability. Unless you feel that what is served to you in the immense stream of information that bombards us daily is relevant to you as well as applicable to your life, you will most likely not feel inclined to act accordingly. Understandably so, actually.

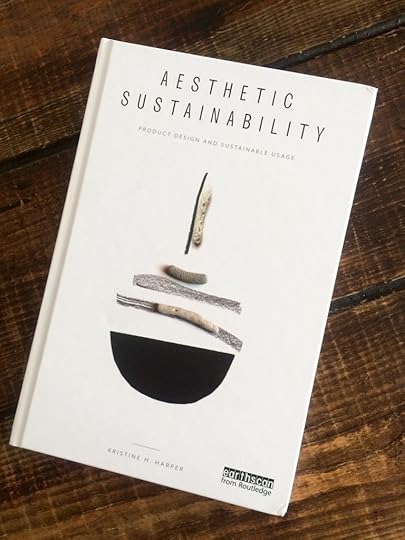

Live Small, Dream Big. That is a bloody good title… And the book itself is full of passion driven projects and aesthetically nourishing photos; inspiring when talking about convincing storytelling. The right photo is not from the same book, but from a novel by Linn Ullmann (in Danish): there is nothing like a good, well-written novel to ignite your storytelling gene, just saying. I really think that fiction is a generally overlooked source of inspiration when working with branding, storytelling, design etc.

Live Small, Dream Big. That is a bloody good title… And the book itself is full of passion driven projects and aesthetically nourishing photos; inspiring when talking about convincing storytelling. The right photo is not from the same book, but from a novel by Linn Ullmann (in Danish): there is nothing like a good, well-written novel to ignite your storytelling gene, just saying. I really think that fiction is a generally overlooked source of inspiration when working with branding, storytelling, design etc. There is something wrong with the way the importance of acting and consuming sustainably is communicated. Maybe that is part of the reason why only a small percentage of consumers are reducing consumption radically. The stories told must resonate with people in order to be persuasive. A large part of the problem is also that changing consumer habits is inconvenient and difficult, but perhaps if the general consumer felt more empowered—if s/he felt the action would make a difference; if it was apparent that there is indeed a link between dying marine life and unsustainable shopping habits; and that by altering habits by reducing fast fashion purchases and investing in more crafts products and generally buying less, but better, more resilient products s/he would make a difference—I believe that we would see a greater number of consumers altering their current practices radically.

This point highlights the importance of no-nonsense, empowering, emotion-stirring, resilient, sustainable communication.

***

Values and beliefsThe problem with communication on sustainability is that it often originates—and ends—in companies’ and organisations’ sustainability strategies and goals. These tend to be too abstract, broad, and rational, which makes it very difficult to write applicable, relevant, touching stories that call for action.

An example of very abstract and broad sustainability goals is UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (the SDGs) to be reached by 2030. The goals are ambitious, which is not a bad thing. We are in need of ambitious objectives regarding sustainability, equality, and environmental issues at the moment. However, the SDGs are virtually impossible to grasp and measure. And, they are difficult for a designer to work with and implement in product solutions that can encourage sustainable behaviour.

Let me exemplify my point by highlighting and analysing some of the SDGs.

Beneath each of the SDGs an array of targets is listed, which is actually a great way to concretise abstract and theoretical objectives. However, the target points are not in any way concrete. If you, for example, take a look at goal number five: Gender Equality, and click on the targets and indicators, the first target point is:

“End all forms of discrimination against all women and girls everywhere.”

Now, there is a lot to say about this target point. One cannot possibly disagree with the importance of it, but how can it in any way be measured, or reached for that matter?

The same goes for the other SDGs. Under number seven: Affordable and Clean Energy, the first target point you will find is:

“By 2030, ensure universal access to affordable, reliable and modern energy services.”

Universal access? Affordable? Modern? These terms are all extremely abstract. What is affordable? I guess that depends on a lot of things, and on where and who you are. What does modern mean? Up-to date? State of the art? High-tech? When one uses terms that are this broad there is a risk of miscommunication, or at least of not getting an important message through, which the SDGs most certainly are. One must help the reader or listener to anchor the exact meaning that one wants to communicate; and making use of broad, abstract terms like the ones listed here is not a suitable way of doing so. A word like modern contains too many connotations and meanings, and it will be open to many individual interpretations. An option is a concept definition, or even better; a different, more distinct word.

Furthermore, as above mentioned, goals must be reachable, which is why aiming for universal access might be slightly farfetched—even given the fairly long timeframe.Think about all the remote regions in the world; how would this ever be achievable? Unless of course, the minds behind this target point have something concrete in mind, like an off-grid package. But, if that is the case, then why not state it like that in order to make the goal more understandable and reachable? The goals would be more clear, plausible, and usable if they were made concrete and accessible.

Communication on sustainability, equality, and environment tends to be too intellectual and non-concrete—as well as way too facts-based and non-emotional. An example of the lack of ability to make the goals feel applicable is SDG number four: Quality Education. Underneath each of the goals you will find the progress that has been made toward reaching the goals by 2030, which in itself is brilliant, but the information is very rational, and packed with facts. Furthermore, this specific goal (alongside many of the others as well, of course) has been greatly affected by the COVID-pandemic. Progress of goal four in 2022 hence starts like this:

“The COVID-19 outbreak has caused a global education crisis. Most education systems in the world have been severely affected by education disruptions and have faced unprecedented challenges. School closures brought on by the pandemic have had devastating consequences for children’s learning and well-being. It is estimated that 147 million children missed more than half of their in-class instruction over the past two years. This generation of children could lose a combined total of $17 trillion in lifetime earnings in present value. School closures have affected girls, children from disadvantaged backgrounds, those living in rural areas, children with disabilities and children from ethnic minorities more than their peers.”

As devastating as this all is, I am not feeling any engagement. I feel upset about it, of course, devastated even. But even though the facts are shocking, it doesn’t make me feel engaged in any way, I just feel powerless; what do to?! Where to start?!

It all feels disastrous and way too big.

However, action is what we need. Action, passion, and engagement.

Unless we are passionate about something; unless it feels relevant and applicable, and perhaps most importantly, possible to do something about, our engagement will typically be short-lived.

Storytelling on sustainability (and education, equality etc.) needs to be personal, applicable, and empowering. Rather than rattling off discouraging facts about the state of the world, more stories that create transparency about the personal consequences for specific, tangible individuals, and stories about solutions and alternative ways of life that feel nourishing, inspiring and empowering needed.

Within communication about sustainability and environmental issues there are manifold alienating terms such as biodiversity, natural resources, ecosystem, permaculture, environment etc. Terms like these are so abstract, conceptual, and nonfigurative that they mean nothing to the majority of people. They create no internal images, or if they do, they are likely diffuse, diluted, and non-expressive. In order to make people want to act—to get out of their easy chairs and change their convenient habits in the name of environmental issues—communication on sustainability must be more engaging, vivid, and personal.

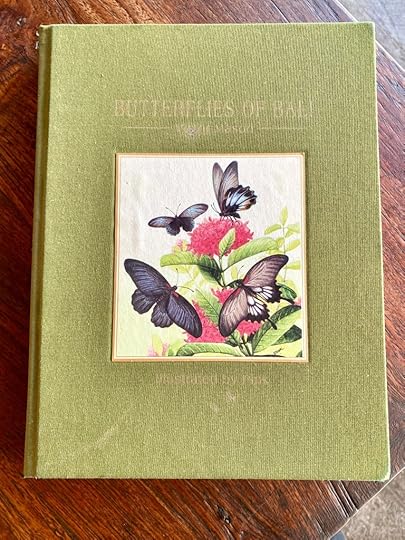

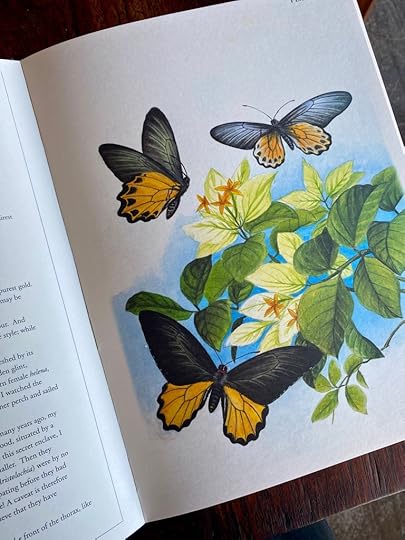

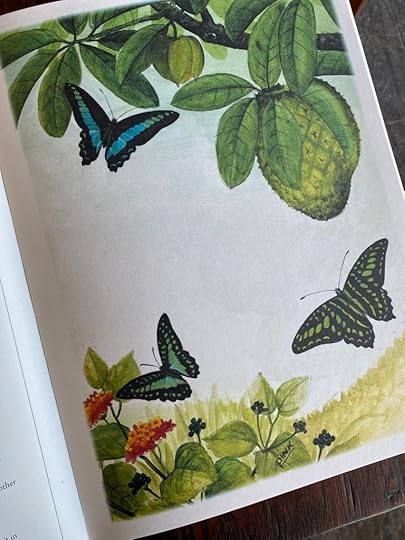

Photos from a beautiful book I recently stumbled upon in a house I stayed in in North of Bali. There are more than 350 species of butterflies here in Bali. They thrive in the diverse, tropical nature. But just like everywhere else, they are threatened. Agricultural monoculture destroys their habitat. In my birth-country Denmark, for example, there are only around 60 species of butterflies left.

Photos from a beautiful book I recently stumbled upon in a house I stayed in in North of Bali. There are more than 350 species of butterflies here in Bali. They thrive in the diverse, tropical nature. But just like everywhere else, they are threatened. Agricultural monoculture destroys their habitat. In my birth-country Denmark, for example, there are only around 60 species of butterflies left. This book made me think of all that, whilst I was looking at the lush, green mountains of the northern. Perfect storytelling. Perfect call for action. No raised fingers were needed.

Pictures must be created in the minds of the audience; emotions must be awoken; we must feel the consequences of our current consumerism and use-and-throw-away-mentality rather than rationally understand it. Companies and organisations need to talk more about values and beliefs and less about facts in order to encourage sustainable change.

And, this is where Aristotle’s forms of appeal become relevant. As ancient as they are.

***

Sustainable forms of appealThe theory of persuasion is created by Aristotle nearly two and a half thousand years ago. Aristotle operates in his Rhetoric with three central forms of appeal to be used when seeking to influence one’s reader, listener, or receiver:

ethos, pathos, and logos

Both pathos and ethos appeal to the recipient’s emotions, though in different ways: pathos awakens passionate emotions, whereas ethos is an ethical form of appeal, and hence pleas to the receiver’s virtue and moral. Logos differs by appealing to the recipient’s reason.

The theory of the forms of appeal was originally written for the speechwriter, and outlines how to create a persuasive public speech and present a compelling argument. However, the points made in Rhetoric can be beneficially used when generating a convincing, sustainable (design) argument as well. If a speech—or a designed object or concept for that matter—is experienced as being relevant it has an effect on its audience.

A central point to note from Rhetoric is that one should ideally make use of all three forms of appeal, and that doing so requires a thorough understanding of the recipient. This basically underlines the fact that if you do not know who you are addressing it is next to impossible to convince them to act in accordance with your message, and, if one tries to convince everybody by speaking broadly and generally without anchoring and concretising one’s points, relevance and applicability fails to appear, which might be the problem with the aforementioned SDGs.

The importance of making use of all three ways of persuasion becomes clear, when diving further into an understanding of each form of appeal. Ethos concerns the speaker—or the designer or sender of the product. Ethos is built up when the speaker appears trustworthy and virtuous. Pathos is related to the audience. When the pathos argument is well-composed it arouses strong momentary feelings within the receiver. Logos appeals to the recipient’s reason and is linked to the topic or the cause of the speech—rather than to the speaker or the audience. In relation to the sustainable-design argument the logos appeal could involve facts about the design-object or “nerdy,” technical details.

Logos is a strong form of appeal, as it can be experienced as very convincing to get the “hard facts” about something present- ed. Most politicians make use of logos when they serve percentages on economic growth (or decline), unemployment, or welfare as hard-hitting arguments in a political dispute. In relation to general communication about sustainability and environment, logos is also widely used: facts about CO2 emissions, statistics on global warming, climate refugees, and numbers regarding the loss of biodiverse areas are communicated in a matter-of-fact kind of way. Importantly though, Aristotle stresses the point that one should never use logos as the only form of appeal, as rattling off facts tends to bore the audience, and thus have no effect. Logos must be combined with at least one of the emotional forms of appeal—pathos or ethos—and ideally with both.

A good way of gaining insight into Aristotle’s forms of appeal is sitting down and listening to a bunch of TED talks. Quickly you will notice that the ones that work—that are captivating and compelling—are not necessarily the ones aligned with your areas of interest, but rather the ones that make use of all three forms of appeal. The speaker offers an insight into her or his life story and actions—establishing ethos; you feel sympathy with the speaker and closeness. Important and well-documented facts about what happened or about the cause that the speaker is passionate about are explained—convincing using logos to build up. And lastly, you—the audience—are drawn in, and you are touched or moved in some way. Maybe you feel sad, angry, or happy, and the limits and the distance between you and the speaker are momentarily eliminated. Pathos is aroused within you.

In order to get someone involved in the battle against inequality, oppression, unsustainable usage of natural resources, pollution, animal cruelty, etc., it is important to engage by evoking pathos; one must feel committed and passionate in order to act accordingly and feel that their actions matter—that every reduction of consumption, every ethical purchase, every heartfelt donation, and every choice not to use single-use plastic matters. If you feel that your actions are insignificant, which can very well happen when faced with massive world problems like climate chang- es, floating plastic islands, and polluted burning rivers, you will naturally be less inclined to change your unfortunate habits than if you feel that every sustainable attempt is an important and meaningful step in the right direction.

Another important point regarding pathos appeal is that it is a way of drawing a direct line between facts and action: this is how it is, and this is what needs to be done, now! And, furthermore, this is how you as an individual can do it. Pathos encourages immediate action.

The benefit of small-scale improvements could constructively be incorporated in the communication on sustainable living. Underlining the impact that we all have, just by choosing to purchase something or not, or by eating meat or not, or by using our right to civil disobedience and reacting if we experience oppressive behaviour by questioning it, is one way of communicating in a more down-to-earth and heart-felt way about sustainability and ethics. Another way is telling stories of the people behind the products we buy: the hands that create them, and the minds that conceive them. Such stories increase transparency.

The more presence a story can create between a design-object and user, the more inclined the user will be to take care the object.

We need stories or anecdotes packed with the tangible consequences of our current consumer ventures rather than fact-driven doomsday descriptions. We need stories about the people that create the products we mindlessly buy that can create transparency. We need presence rather than distance. Distance leads to detachment, detachment leads to indifference, and indifference leads to irrational consumption. It is so easy to forget about the underpaid workers in the sweatshop in Bangladesh when you enjoy your cheap, trendy new dress—harvesting approving gazes from peers and feeling fashionable and fresh, without having spent very much money.

Establishing a link between the underpaid worker and the feel-good dress as a part of the consumer-situation is next to impossible. However, we need to be reminded of that link, and initiatives like Fashion Revolution, founded by sustainable fashion campaigners Carry Somers and Orsola de Castro, do exactly that.

The Fashion Revolution was started as a result of the collapse of the Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh on the 24th of April 2013 (yes, it will be ten years ago this year). There were five clothes factories in the Rana Plaza, all manufacturing clothes for big global fast fashion brands. After rescue efforts en- sued, 1,138 people died and 2,500 people were injured, most of them young women.

Fashion Revolution believes that the most important step toward positive change in the fashion industry and more conscious and ethical consumption is transparency. And so, the revolutionary team behind Fashion Revolution encourages people to wonder and ask, “Who made my clothes?” by posting pictures of themselves on social media wearing clothes inside-out while tagging fast fashion brands and asking them this question tagged with #who made my clothes.

To date there are hundreds of thousands of posts on Instagram with the hashtag. The campaign creates an acute bond between the consumer and the maker, a bond that is crucial in order to decrease the distance between the consumer in the fast fashion store—who is about to buy yet another cheap dress—and the worker in the Bangladeshi factory who is working twelve hours a day for next to nothing.

This transparency logic is based on a simple supply and demand reasoning: if fewer consumers buy cheap, fast-fashion items because of increased awareness about the consequences of these purchases, and simultaneously make the big brands aware that they are no longer interested in buying unethically produced items, the brands will be forced to alter their business models and improve working conditions in the clothing manufacturing industry.

Fashion Revolution takes this a step further and encourages farmers, factory workers, artisans, and makers to create a response to the consumers’ question by posting a photo of themselves with the tag #I made your clothes. Suddenly photos of workers, artisans, and farmers from all over the world are popping up on social media, creating stories about the proud, skilled people and the—at times poor—living conditions that our seemingly innocent consumer-ventures affect. There is a lot of inspiring pathos and so much ethos in those stories.

Activism can generally be very inspiring when working with sustainable storytelling intended to make people act or alter unfortunate behaviour, because the core of activism is to promote change.

If you want more on this topic, you can read much more about sustainable storytelling in my book Anti-trend.

January 17, 2023

What is home?

This post consists of the exhibition text I recently wrote for my amazingly talented friend Lydia‘s current solo exhibition with the title “Yellow Brick Road” at RedSea Gallery in Singapore (January 12.-22. 2023).

Lydia’s paintings are large, dynamic and powerful, and I absolutely love looking at them, taking them in, and writing about them. Seeing photos of them don’t really do them justice; they must be experienced in person. And, if you happen to be in Singapore this week, here is your option.

***

Yellow Brick RoadWhat is home? A place? A sensation? Stillness? Movement? Anchoring? Detachment? Is homeliness to be found in the vibrant now or in our memories?

Or, is it all of the above?

In Lydia Janssen’s latest work she explores the concepts of home and homeliness.

Inspired by the Wizard of Oz and the main character Dorothy’s quest to get back to Kansas; the characters she meets along the way and the experiences that alter her sense of self and rattle her deeply rooted sense of place, Janssen investigates what it means to belong and feel at home.

In 2011, Janssen, her husband and their first-born daughter moved from New York City to Singapore, 7 years later as a family of five, they moved to Bali, Indonesia. Then in 2020, having traveled between five countries during the pandemic, all in an attempt to get back to their home in Bali, Janssen became fascinated with the psychology of space, place and how one’s definition of home changes when living a nomadic life. How can you belong somewhere when you are an expatriate, an immigrant, a foreigner, an outsider, a newcomer, a visitor, a guest; unfamiliar with the local customs and the language spoken?

Home can be a finite comfort zone in the midst of unfamiliarity. Or, the feeling of home might be essentialized in sudden glimpses; a scent, a sound, a feeling: elements that send you on a sensuous time travel. Back in time. To childhood rooms and neighborhoods; the smell of your father’s study: tobacco, ink and books; forbidden and alluring, the flavor of your annual birthday cake and the saturation of sweetness when the first bite would fill your month, the musky smell of newly fallen rain in the forest of your youth, the sensation of running your hands over your parent’s velvety sofa or walking through your childhood home barefooted. Sensory memories that momentarily dissolve time and concurrently remove you from the present and bind you to it. Rootlessness and groundedness, all at once.

Is feeling at home a movement towards becoming more and more yourself? Does it involve narrowing down the essence of you to its core elements?

Movement has always been home for Janssen; her past as a professional dancer leaves clear traces in all of her paintings. In her new work, movement is investigated in a vast variety of shapes: twisting, running, roaring animals; bodies that curve and spin, unfold and crumble; waves of color and light; rocking horses and long hair thrown forcefully back forming vibrant curved lines.

Home as a place associates simplicity and everydayness; it is our private sphere and the space for our most intimate feelings and activities. There is something mundane about homeliness, and the banal everydayness is also present in Janssen’s paintings and drawings: a naked woman examining herself in the mirror, a telephone, a fan, a television, a clock, cutlery. A home can be limiting and claustrophobic (especially when quarantined); and henceforth, the nomad life can constitute a liberating escape from restrictions and boundaries.

Our home is a multifaceted scene for privacy and secrecy as well as gatherings and celebrations. In one of Janssen’s paintings a birthday scene unfolds: a cake and a group of people fill the canvas; you can almost hear the clinking glasses and cheerful voices. The painting is simultaneously the antithesis to the intimacy of the everyday objects and an emphasis of the complexity of the layers of home.

Inspired by the work of the artist duo Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Janssen’s exploration of home furthermore includes wrapped sofas and chairs that leave you wondering what it takes for familiar, everyday objects to stop being recognisable, and whether or not recognisability is prerequisite for homeliness. Traveling around with her family over the past years, Janssen stayed in multiple impersonal, serviced apartments, surrounded by insignificant, dull, uncomfortable, unhomely furniture – longing for aesthetic nourishment, comfort and inspiration. She fantasized about wrapping the pieces of furniture around her and turning them into pure, open shapes, and explored this thought-experiment in her sketches. Could openness and pure shapes allow for personal associations to flourish and hence wipe out the impersonal, unhomely character of the standardized furniture?

The layers of the wrapped furniture are characteristic for Janssen’s new work. Layers of painting cover underlying motives and symbolize the many facettes of homeliness; some hidden, some visible.

Home might be characterized by a degree of constancy, but as a wise man stated thousands of years ago: the only constant is change. And, in Janssen’s work this statement is ever-present: flow, vitality, movement, dance. A whirlwind of beasts and bodies bombard your senses. One of the paintings can even be turned both horizontal and vertical to underline the changeability and flow of life. Like a river that you can never step into twice, the experience of Janssen’s work will alter, depending on your mood and emotions, memories and experiences, and on the atmospheric changes in your physical surroundings.

Janssen’s work holds an invitation to follow the colors and the shapes down the layers of the yellow brick road, home. Whatever that means to you.

My house says to me, “Do not leave me, for here dwells your past.”

And the road says to me, “Come and follow me, for I am your future.”

And I say to both my house and the road, “I have no past, nor have I a future. If I stay here, there is a going in my staying; and if I go there is a staying in my going. Only love and death will change all things.”

Khalil Gibran

December 20, 2022

Embrace your despair – it might set you free

Last night I went out for dinner with my family. My teenage son and I came 45 minutes before the rest of the family, and we had a conversation that made me want to read up on existentialist philosophy; particularly Kierkegaard and de Beauvoir.

Why? Well, we were sitting at a very beautiful restaurant in Ubud surrounded by lots of beautiful people; all looking very much alike, and apparently all agreeing on the dresscode and right thing to eat and drink; even the right way to enter the room and act (I won’t go into details here, as this observation is not meant as a critique or farce). Of course it’s normal that people want to fit in and match their “tribe”, but this was almost a little too much. And my teenage son started to laugh: it just seems so fake, he said.

I told him that they were probably all really nice, friendly people, but I must admit that the scenario around us started feeling slightly comical, as clone after clone walked in.

Why are we so eager to match our surroundings? We are people, not chameleons.

And what is the opposite of appearing fake; does being authentic necessarily involve standing out?

(Quick side-remark: In my new book-project Uncultivated, I am currently in the process of writing about our primitive brain, or our cave(wo)man brain as I have chosen to call it, and it’s immense need to feel secure, “right”, a part of something, liked, safe – and also how freeing ourselves from this innate instinct or shutting down the cave(wo)man brain might liberate us. Rewilding is a part hereof; more hereon later).

The following text consists of extracts from my book Anti-trend. It’s long, I know – and sorry about that – but maybe a long read over the holidays is an option? And if it is, and you are eager for more, I can warmly recommend diving into some of Kierkegaard’s or de Beauvoir’s writings (or Sartre’s or Nietzsche’s for that matter); they beat any self-help, personal development book ever written.

You can also read more about existentialist philosophy and its relation to sustainable living in Anti-trend.

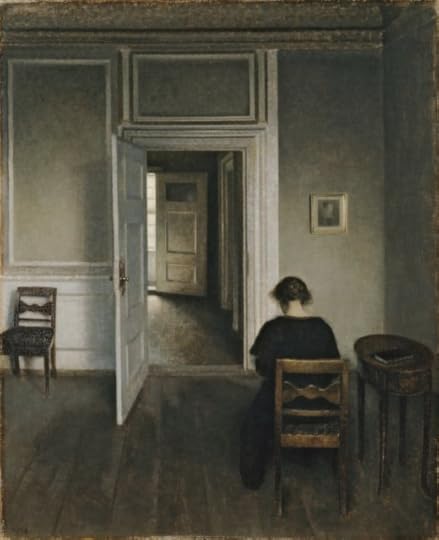

Vilhelm Hammershøi, Interiør, Strandgade 30, 1906-08. A painting that always spoke to me about the banality and despair of everyday life.

Vilhelm Hammershøi, Interiør, Strandgade 30, 1906-08. A painting that always spoke to me about the banality and despair of everyday life.***

In Danish Philosopher Søren Kierkegaard’s seminal work Either-Or, Kierkegaard introduces a personality-type that he calls “the Aesthete.” The Aesthete is characterised by living in the now and constantly seeking pleasurable, easy-going experiences. The aesthetic approach to life is hedonistic, lust-based, founded on momentary desires, and hence the life of the Aesthete lacks continuity and stability: it is built up around short glittery moments that are not linked together, but rather disjointed like marbles in a box. The Aesthete is governed by an extreme focus on excitement and pleasure, as s/he views boredom and triviality as the root to all evil.

The Aesthete lives in despair and is ruled by what Kierkegaard calls the “unhappy consciousness.” Despair, in Kierkegaard’s philosophy involves having an inauthentic, malfunctioning relationship to oneself—or being unaligned with oneself. Living in despair does not necessarily mean that one is unhappy; alike the Aesthete one can be and appear happy and enjoy one pleasurable moment after the other, even though deep-down despair is governing life.

The Aesthete has discovered that the immediate human condition, referred to by Kierkegaard as the Philistine, is empty and un-essential. However, the Aesthete also lives in despair, only more consciously. The life of the Philistine can be described as “human possibilities,” and the Aesthete has comprehended that the realisation of the possibilities is lacking.

The Philistine’s conviction that he is his own master is thus an illusion. He can only make that decision which has already been made by anonymous forces. If as a businessman, he decides to open a branch in the next town it is economic forces and the law of supply and demand which controls him. If he chooses a trip to Acapulco for his summer vacation his choice is dictated by the social pressure which prompts a man in his position to vacation in Acapulco. And the same wherever it appears as if he himself is making a decision and carrying out an action (Sløk, 1994).

As shown in this quote, by Danish Theologian and Philosopher Johannes Sløk, the Philistine is governed by expectations and the “rules” of social behaviour. The Philistine is extroverted and absorbed by life’s many problems, and hence is a busy person (which tends to be a status-symbol in our late-modern capitalistic, industrious, innovation-focused culture). But to be busy in a world where nothing is of genuine significance appears petty—even comical. The Philistine thinks that s/he is living an authentic life, but is guided by cultural constructions, which are solely valid due to conventions. His/her despair is unconscious (and thereby different than the despair of the Aesthete).

The moment the Philistine recognises that s/he is in fact a Philistine (and acknowledges that s/he is living an extroverted life dependent on success, status symbols, and the approving gazes of others)—if s/he ever does; most people don’t according to Kierkegaard—s/he is immediately transformed into an Aesthete.

But what does it take for a Philistine to realise that s/he is a Philistine? Nothing in particular. Or rather, the possibility for the realisation lurks in each moment. It might show itself as a sudden feeling of meaninglessness, or as Sløk puts it, “How you can suddenly stop amidst the bustle of the day and with uncanny clarity realise that all of it is at bottom nothing, that all striving is pointless vanity, that all goals crumble in indifference”. Perhaps you choose to ignore the feeling and move on in your busy life (and perhaps you drown the lurking despair by buying a few new glittery things or by opening a bottle of wine in the evening), but perhaps you don’t. And if you don’t ignore it, if you choose to let that moment of clarity grow, the process of realisation begins.

The first step away from the immediately given reality is a move toward the Aesthetician existence, which is nonetheless also characterised by despair. As a result of the emptiness and anxiety that stems from the insight into the Philistine existence and the lack of human realisation, the Aesthete places her/himself outside of reality. Thus, the Aesthete’s main problem is that s/he is unable to find an alternative to the given, Philistine reality. S/he understands that it is hollow, but is unable to find an alternative meaningful foundation for life. An ironic distance is kept from the Philistine, bourgeois existence, which s/he now finds ridiculous—but ironically, this distance ties her/him to the bourgeois life as the one that disassociates from it—a dissenter. S/he orbits the life that s/he refuses to be a part of. Nevertheless, the conscious despair of the Aesthete is a prerequisite for removing despair and emptiness—just as self-identity requires the unhappy awareness of non-identity.

But, what does the Aesthete do in order to stand the emptiness of being that s/he has discovered?

Kierkegaard’s Aesthete embarks on a hunt for uplifting moments of pleasure: a pleasure-hunt that is characterised by volatility and consumption. Consumption of beautiful lovers, luxurious experiences, delicious meals, and state-of-the-art goods. Since the aesthetician stage is characterised by a lack of individual standards or morality, the Aesthete focuses solely on experiences, pleasure, and well-being.