Kristine H. Harper's Blog, page 2

June 3, 2024

Slowing down can be a way of rewilding yourself

Life lately for me has been taking place in the slow lane.

It is not easy for me to slow down. I always have a thousand projects and ideas for writing, research, new designs, collaborations, etc. etc. And all of that noise tends to be mixed with piles of books I would like to read, music I want to re(listen) to (I am trying to slowly go through my record collection, reliving why I bought each record), and plants I want to try to grow in my garden (and as this whole gardening thing is 100% learning by doing, there are lots of trials and frustrating errors!).

One of the many beautiful butterflies in my garden

One of the many beautiful butterflies in my gardenBut, slowing down is important. Most of us can agree to that. So, why can it be so hard?

Perhaps one of the reasons is that when we slow down, we don’t feel productive. And in a result-focused, growth-obsessed time era like ours that can be hard.

However, I have discovered that when I allow (or force!) myself to slow down something interesting happens. And that is: I get novel ideas that take my research to places I hadn’t gotten to if I had pushed myself to study for hour upon hour, I meet people and form connections I otherwise wouldn’t have — and these lead to talks that inspire me and create new fruitful opportunities, I experience nature as a part of me and get deeply nourished by the natural environment around me, and I am much more focused and calmer when I engage in problem solving.

Furthermore, my garden really likes it when I am slow and calm; the plants thrive on slowness.

Slowing down has become my way of rewilding myself.

My son cutting down bananas in our garden

My son cutting down bananas in our gardenI recently read up on French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s (1712–1778) philosophy, and in particular his seminal Emile, or On Education (1762). In short, the philosophical explorations of Emile revolve around the boy Emile, who is taken away from society by his teacher in order to let the natural course of development take place (and without being disrupted by society and cultivation). Rousseau’s mission was to explore an educational system that allows for what he calls the natural man to develop without being corrupted by society.

Rousseau pleaded for children to be children rather than small adults. Until children are 12 years old, they should run around and not sit by a desk, he thought. Rather, they should be outside and learn from nature, and do so without science textbooks (which in his opinion would be considered negative education, at that stage of children’s development). The child is a natural learner, and so, (s)he should be encouraged to cultivate that innate ability and inborn curiosity.

And so, in order to fulfill this dream, Emile is kept away from society by his tutor. Only as a teenager is he introduced to citizenship. This is done in order to ensure that the essence of early-stage education is characterized by free exploration; by play and by slow exploration of nature.

My neighbouring farmer

My neighbouring farmerRousseau’s core-belief was that in order to live a happy life (or a life worth sustaining) one should leave the city and live in a natural environment. He envisioned small, harmonious, self-sufficient communities in sync with the local environment and nature. In a sense one could argue that he was a forerunner for the slow living movement as well as for locally grown, sourced produce. He would most certainly have been against big global chains and the homogenization and sameness that such entities enthrall.

The plea in Emile holds a bit of Thoreauvian into-the-wild-ness.

American essayist and philosopher Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862) wrote Walden: Or, Life in the Woods in 1854. The book revolves around him leaving society and wandering into the woods, building a cabin on his own, and staying there for two years, two months, and two days (what a statement, right?).

In the forest near Walden Pond, Massachusetts he spent his time reflecting on how to live a good, fulfilling, non-materialistic, and self-sufficient life. As Thoreau states in the beginning of the book:

”I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”

The Rosseauean idea of society corrupting us and misleading us seeps through this. That in order to live natural, authentic, fulfilling lives (that we can sustain and justify) we must leave society, turn our backs on civilization and engage in an (slow) uncultivated way of life in close connection with nature, if only for a while. It is the idea that we cannot as a part of society be fully free and creative.

However, while Rousseau discusses the education of the child (the uncultivated mind and soul), Thoreau focuses on rewilding the cultivated, civilized adult. The undoing of the harm of civilization can be done, but it requires a withdrawal, it requires a conscious move away from society and back into the wild.

I guess Rousseau would argue that a more applicable way would be not to get there in the first place: to ensure through the upbringing and education of children that they are equipped to live as a natural being within society; to reinforce instead of reverse, to prevent instead of cure.

Maybe that would also make it easier to slow down.

Cover art by Lene Refsgaard

April 10, 2024

Can aesthetic preferences be inherited?

When I studied philosophy at university decades ago I was captivated by philosophical aesthetics, particularly the sublime aesthetic experience, which encompasses chaos, asymmetry, distortion, imperfections as well as decay. And this fascination has never left me. Rather, it has set the tone for my research and my books.

The sublime aesthetic experience, as opposed to the beautiful, is initiated by phenomena or objects that provide the receiver with an aesthetic kind of pleasure that doesn’t match the “classical” concept of beauty.

The difference between the beautiful and the sublime concerns the difference between order and chaos; between symmetry and asymmetry; between predictability and unpredictability; between demarcation and boundlessness; between form and formlessness; between proportion and irregularity; and between the kind of aesthetic experience that nurtures one’s comfort zone and that which challenges or breaks it.

The beautiful and the sublime are at once diametrically opposed and mutually dependent on each other. In a sense, they embody the yin and yang of aesthetics. They are fundamentally different, but existentially dependent. For instance, it is nonsensical to speak about symmetry without at the same time understanding the concept of asymmetry, just as harmony cannot be grasped completely without its opposite, disharmony.

One of my many heroes within sublime philosophical aesthetics is French philosopher Jean-Francois Lyotard (1924–1998), who launched what he called the postmodern sublime, which he linked to the 20th-century Avant-Garde art. He viewed the sublime as an essential element of the artists who revolted against the Romantic “closed” pictorial space.

The aesthetic of sublimity liberates pictorial art from the demand to facilitate concrete messages, and thereby it sets free the power of creation.

Whereas Lyotard associates modernity with the nostalgic, romantic sublime, he relates postmodernity to the other form of sublimity, which, to him, encompasses the true sublime — or at least the kind of sublimity he finds the most interesting. The (postmodern) intense sublime moment revolves around the pleasure of It is happening, the delight of something shocking (an object or phenomenon) as well as the fear that It will stop happening, and that nothing further will happen. The dialectic of delight and fear, pleasure and pain, or the It is happening and the It can stop happening hence characterizes his definition of the sublime.

The sublime aesthetic experience can beneficially be interlinked with the prolonging of the design experience, and hence with object-related sustainability (which I have investigated in my book Aesthetic Sustainability).

But the focus of this article is the sublime aesthetics of decay.

In our culture, beauty is often considered a fleeting thing. Something that disappears as a result of decay, wear, or aging. Something that is “crisp” and new. In this way, beauty is connected to the polished, to the not-worn, to the “pretty,” and to the pure, aromatic, and proper.

However, there exist philosophico-aesthetic traditions that associate beauty with the uneven, unpolished, and corporeally challenging — rather than with newness — and even with aging, decay, and wear. This concerns the aesthetics of decay — a concept favored by photographers who are attracted to ruins and abandoned urban environments.

The aesthetics of decay celebrate decline! Aestheticians of decay like to show the beauty of peeling paint; tattered wallpaper; overgrown walls covered in wild, uncontrollable vegetation; and pockmarked rooftops infested with pigeon’s nests and spider webs — or, in other words, the beauty that appears when letting something “be,” allowing the ravages of time, wind, and weather to stamp objects and buildings.

There is a degree of rewilding within the sublime aesthetics, which is probably part of the reason why I have felt so attracted to the concept of rewilding ever since I first came across is, and am currently researching it in relation to nature, human life and design. The idea is letting go of control and allowing for wild nature to grow and develop in uncultivated manners.

And, now my oldest son has developed a fascination for decaying, abandoned buildings and urban areas.

He recently made a documentary about an abandoned amusement park here in Bali called Taman Festival Park (which I wrote about here), and when we visited Hanoi last week, he wanted to see an abandoned suburban area called Lideco Bắc 32 and photograph it. And so, we went.

It was an eerie place! But I totally understood his fascination with the quiet empty streets and the abandoned buildings. He was a bit disappointed that the vines and trees that he had seen grow wildly in photos on the internet had been trimmed, but the beauty of decay, the sublime horror, was predominant in this creepy silent place that had been built to house hundreds of families but never got off its ground.

When we are going to Europe this summer, he has a few decaying places and buildings lined up, and I am happy to come along.

February 14, 2024

Reframing the Way We Design, Use and Consume Things

In sustainability debates the three Rs: Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle are often featured as a useful sustainable trinity.

However, I always solely focus on reduction rather than reusing products or product waste and/or recycling when working with sustainable design.

My focus on reduction is not meant as an attempt to underestimate the value or importance of the other two Rs, but no matter how good we are at recycling waste materials and using them for new products, it still requires large amounts of natural resources to do so. And, no matter how efficiently we reuse discarded objects by implementing take-back systems, it doesn’t eliminate the fact that there are simply too many unwanted things in the world.

Focusing on reusing and recycling can be dangerous, as it tends to create the mentality that overproduction and overconsumption is justifiable, because there are systems to take care of our excess things when we no longer want or need them. However, the existing systems cannot cope with the overload of goods being produced and discarded.

Reducing consumption (and encouraging reduced consumption through design) is essential in my opinion and a central part of my research — but furthermore our times call for something more radical on top hereof. And hence, I have added a new R to the trinity, namely Reframe.

Southeast Saga Reborn Kimono, detail

Southeast Saga Reborn Kimono, detailReframing concerns first of all rethinking and reevaluating the way we look at objects, at things — at all the beautiful, functional, and not so beautiful and not so functional objects we surround ourselves with. Reframing involves a phenomenological approach to our physical surroundings.

When I write phenomenological, I mean a focus on our bodily, physical, tactile interactions with the things in our surroundings, rather than a symbolic one. As one of my favourite thinkers, Danish artist and philosopher Willy Ørsov (1920–1990) puts it: “An object is a frozen or fixed event”.

Let me explain.

The majority of the things we discard are not discarded because they no longer work, or because they are worn out, broken, torn or faded. No. Most discarded things are still perfectly fine, in the sense that they still work in the intended way: they can still be worn and used in the way they were designed to be. Of course one of the reasons for rejection is likely that they are made in a way that makes them impossible to repair, mend or update. But the main reason that we discard our things is that they are no longer trendy, or that they no longer nourish us aesthetically. The reason for the rejection is in other words mainly interlinked with their symbolic value rather than their functional, phenomenal value. So, when reframing the way we design and produce things and the way we consume things, un-symbolising them is one of the crucial steps!

The symbolic side of an object, or the associations that an object might trigger, is, according to Ørskov, only a secondary quality, whereas the primary quality concerns the object’s purely physical and spatial existence or presence. And therefore, if a sculptor (or a designer, for that matter), as the point of departure for the creative process, has decided the “fate” of the object based on its symbolic value, she is, according to Ørskov, working in a reverse manner, and is thereby at risk of creating fleeting objects that can only be described as what Ørskov calls “fashion phenomena” (which is a strictly negative designation!). The durable and truly effective and aesthetically nourishing object is in conflict with fashion and trends. And hence with consumption.

I recently read a very thought-provoking book by Korean-born philosopher Byung-Chul Han called Saving Beauty. Han is occupied with how our late-modern need for smoothness and convenience has destroyed beauty in the sense that beauty has turned into nothing but blandness and easily digestible, pleasurable simplicity.

Han’s book on beauty starts like this:

“The smooth is the signature of the present time. It connects the sculptures of Jeff Koons, iPhones and Brazilian waxing. Why do we today find what is smooth beautiful? Beyond its aesthetic effect, it reflects a general social imperative. It embodies today’s society of positivity. What is smooth does not injure. Nor does it offer any resistance. It is looking for Like. The smooth object deletes its Against. Any form of negativity is removed.”

No, Han is not a big fan of Koons. He later writes that Koons’ smooth sculptures cause a haptic compulsion to touch them, even the desire to suck them. This is not a good thing in Han’s world. Not at all. In order to save beauty — and reunite with all facets of beauty; not only the smooth ones, but also rawness, the anti-smoothness, complexity, the sublime — we must salvage negativity.

And I agree.

As I wrote in my book Anti-trend:

“The enduring aesthetic pleasure that the resilient design-object awakens in the receiver is reliant on changeability, on a degree of rawness, and on accepting that not everything can be controlled. The aesthetically resilient design-object is raw and uncontrolled in the sense that it is open to the traces that usage will leave on or within it; it is open to be molded and mended in ways that will fit the individual user, and it is open to the stories that are linked to traces of wear.”

The aesthetics of beauty in modern times equal smoothification. And the aesthetic of the smooth is embodied in Koons’ smooth, shiny sculptures: they lack negativity and are reduced to beauty, joy and communication. They are shiny as mirrors — and isn’t that all we want now-a-days? A mirror that we can meet ourselves in, admire ourselves in, be confirmed within (- otherness, rawness, decay, danger, diversity, negativity is absent). As Han. puts it: The beautiful is exhausted in a Like-it culture.

Perhaps reframing involves an anti-smoothification! The smooth and shiny beauty that Han revolts against doesn’t leave us with anything but a pleasurable meeting with ourselves; with sameness and self-absorbedness; with our own smoothified reflection (which is at times filtered until a state of unrecognizability). Our narcissistic late-modern culture really doesn’t need more of this smooth kind of beauty. No. What is needed is more heaviness (as I normally call it) or more negativity (as Han would call it).

This basically means that we need more friction and less “smoothness” and convenience. We need more purpose, more commitment, more heaviness and less insignificant lightness. We cannot justify using natural resources to create boring smoothness and convenience products that might on the surface appear to improve our lives, but really only make us feel more and more detached. From our natural environment, from true, raw beauty, and from each other.

We are used to considering the resources around us a commodity for us to use to create things; most of them insignificant, some of them even single-use, and a small percentage of them made for long-lasting usage and made to be aesthetically sustainable; meaning non-smooth, but made to be used and worn and to develop and decay in a nourishing, raw manner. We are used to considering nature’s resources inexhaustible.

But they are not.

Of course, they are not. No natural growth process can keep up with the speed at which we are cutting down trees and harvesting crops. We are running out of natural resources and are being forced to reframe our perspective.

One of Einstein’s theories was that nothing can be created or destroyed — only energy is moved around. If that is true (and I believe it is) then all the single-use and all the discarded products and the mountains of material waste that are currently being created are a huge problem. They dissolve energy and they block the flow of life.

How do we restore the flow of life? How do we reframe and alter the way we look at products, at consumption, at things, at resources, at beauty and our need for soothing self-affirmation and for convenience?

January 10, 2024

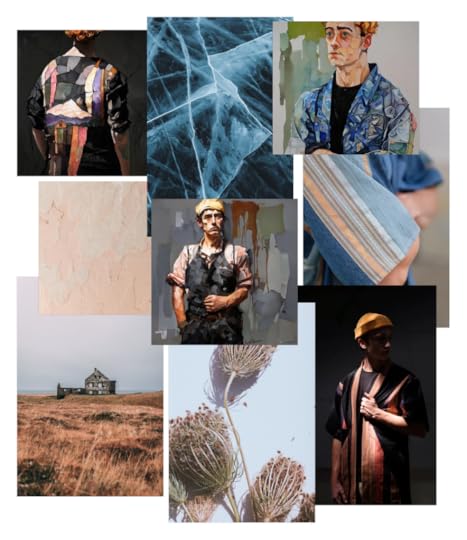

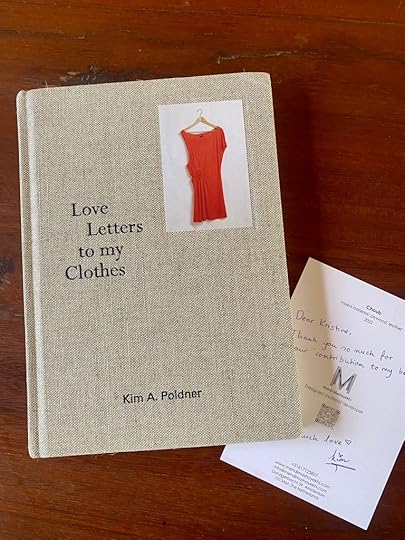

Introduction to the book ‘Love Letters to my Clothes’

I recently had the pleasure of writing the foreword to Kim A. Poldner’s new book Love letters to my clothes. It is an inspiring and extremely aesthetically nourishing book that celebrates the clothes we wear and love — and by doing so, investigates the difference between meaningful and meaningless garments.

Kim has given me permission to share the foreword here with you, and I will follow up with an interview with Kim next month.

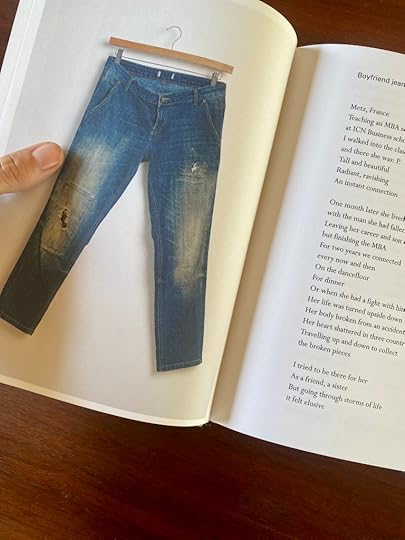

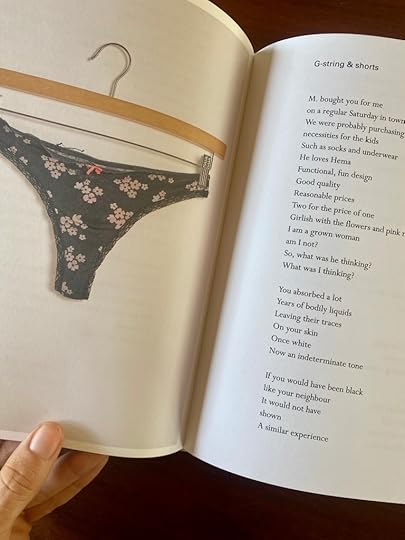

This book is a celebration of user traces and decay, of loving bonds between people and their belongings, of the time that lingers and adds character to lovingly used things, and of inclusive sustainability. The garments in this book are carriers of time and an embodied discussion on how decay can keep an initial object-crush fresh and broaden our perspective on what sustainable fashion encompasses. They constitute a material manifesto of long-term usage.

In my books on aesthetic sustainability and design I have explored what object related sustainability means and what a justifiable life worth sustaining involves. Repetitions and endurance are crucial elements. But sustainable living also involves letting go of actions, relationships, and objects that are not — or are no longer — beneficial, constructive, or worth sustaining in relation to one’s life’s journey. In Love Letters to my Clothes this is exactly what Kim A. Poldner does.

Prolonging the lifespan of our belongings constitutes a cornerstone in sustainable living: being mindful of what we buy and focusing on the usage and the value of things rather than on the momentary newness fix. Long-term usage involves mending, improving, and caring. But, as the only constant is change — like a wise man said thousands of years ago (Heraclitus, Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher, 544 BCE) — sometimes it is time to let go. When things no longer fulfil or serve us but start to drain us or keep us stuck in the past, or when things are so closed that their aesthetics are no longer nourishing, it might be time to say goodbye — with love and gratitude for the time they served us, of course.

However, just imagine if some of the potentially resilient clothes in the book — like the Karen Millen dress (that was somehow always too static for the author to fall deeply in love with) or the Silk dress (that literally fell apart) — had been designed to be open to wear and tear, open to usage, and open to life. They could have then stayed in the author’s wardrobe for years and years to come; developed with her changing needs or altering body. Instead of being discarded, they could have been an ever-evolving aesthetic display of usage and life. When things are closed, however, they have an expiration date.

Sustainable fashion should be open rather than closed.

Images from the book Love Letters to my Clothes

Images from the book Love Letters to my Clothes

Besides the celebration of decay, the book presents an intriguing, and much needed, democratic, non-elitist approach to sustainability. By exhibiting her decaying pieces of clothing, and even serenading them, the author challenges what it means to be well-dressed. This display contains an inherent critique of materialistic, flashy status symbols as well as a refreshing appeal for new (sustainable) forms of cultural, societal prestige. Maybe the new well-dressed could be wearing mended garments and uniquely combined preloved outfits; flashing creativity and sense of aesthetics rather than purchasing power?

At present, however, it appears that sustainability has become the new luxury — and not in the “wear-your-clothes-till-they-fall-apart” kind of way. Despite repairing and reusing being both affordable and approachable ways of life, they (still) don’t seem to be vastly common. And furthermore, the least well-off seem to be the least engaged in such sustainable (and affordable) activities.

Why? Well, in order to be able to repair one’s belongings, they must be repairable, and in order to reuse things, they must decay in an aesthetically pleasing way. And generally cheap mass-produced things do not. They are produced to be obsolete after a short period of usage. Sustainable design-objects created for longevity on the other hand are typically marketed as luxurious, which seems to legitimise their price tag. Of course, slowly crafted, thoroughly designed objects and well-researched sustainable design solutions are pricier than mass-produced goods (and rightfully so). But creating affordable enduring, repairable things is not impossible.

When sustainable design is branded as yet another traditional status-symbol, or yet another way to express wealth, living sustainably alters from being the most reasonable way of life to being out of reach for the vast majority. Sustainable living should be interlinked with simplicity and community, repairing and sharing, but instead it primarily connotes good (expensive) materials, silent retreats, slowness, and electric vehicles. Sustainability has become for the fortunate well-off and well-informed few; it profits from righteousness and class-divisions. There is no community-feeling in exclusive sustainability.

Some of the clothes I would write love letters to.

Some of the clothes I would write love letters to.

I have lived in Bali, Indonesia for four years. And sustainability here is an entirely different conversation than when I was living in Denmark (which highlights the point on class-division). Let me explain.

When I just moved here, I spoke at a sustainable design festival. My focus was on aesthetic sustainability, the importance of investing in durable things, and how decay can beautify a well-made piece of furniture or clothing. There was a question from the crowd: “What if you cannot afford to invest in slowly crafted garments that age with beauty?” It was a relevant question. Because despite the fact that investing in durable things that can continuously nourish us aesthetically is probably the most affordable in the long run, this is not an option for everyone. If you have no savings, then how can you invest?

However, despite investing in thoroughly crafted, well-designed garments not being an option for everyone, there is one thing we can all do. And that is buying (mainly) second-hand. So why don’t we? I think the only answer to that question is that there is (still) a stigma connected with discarded things. Especially when it comes to clothes. And here in Indonesia this stigma is substantial. There is a visible amount of prestige interlinked with purchasing and flashing a glittery new plastic wrapped accessory or a chalky white synthetic statement t-shirt, never used before, and cheap enough to discard after a few times of wear; even in a place like this where the average salary is around 20 euros a day.

In my birth country Denmark too, there is still a degree of hesitation to track in relation to second-hand clothes. Buying new (sustainable) clothes remains more prestigious than buying used. And this despite the immense societal focus on recycling.

So, what is the solution? I think there are two solutions, actually, and that they need to go hand in hand. The first one being making it cool to wear preloved clothes by eliminating the cultural stigma, and the second one being democratising sustainability. Easier said than done, obviously.

In order to make second-hand garments cool we need more embodied manifestos of usage, like Love Letters to My Clothes. We need to preserve the intimate love-relation to our favourite clothes, focus on the aesthetically nourishing qualities of preloved garments, and celebrate the stories and memories that are stored in our wardrobe. And of course, we need to highlight the coolness-factor interlinked with unique outfits, creative mends, and beautifying wear and tear.

The art of democratising sustainability doesn’t only involve simplifying sustainable solutions in order to make them more affordable. It also requires a change in habitual mass-consumption. This change could be fueled by an understanding that unless the vast majority of people find pride in living sustainably the real healing will never happen.

Sustainable living should be inclusive rather than exclusive.

January 8, 2024

The Om of a Kimono

What does the mantra ‘Om’ have to do with a kimono? Let me share a story.

Ketut. It was Ketut who guided me into connecting the dots through the most surreal experience in my life: a plethora of ancient instrumentation guided to heal the soul. I never anticipated the influence a gong bath would have: it brought me into a deep state of relaxation where I began to see a kaleidoscope of visions. A colour which particularly stood out was indigo that also represents the sixth chakra. Ketut, who also happened to be a local priest in Ubud, Bali, blessed me by applying a few rice grains between my eyebrows, while simultaneously chanting a few sounds that for all I know were ancient mantras. In Balinese culture, placing rice on the forehead signifies life and the opening of the third eye: a powerful place in the human body where energy is concentrated: ‘’People have neglected their internal worlds, just breathe, everything you want is within you’’ he told me.

Just as individuals have lost touch with their internal voice, the hunger for fostering a deeper connection to our roots grows bigger. One way of manifesting it into reality is promoting balance in our emotional centres, or what most of us know as ‘chakras’. Awakening our authentic selves is an intricate dance, which essentially involves a rebirth of extinct values and a rebalance of the energy flow. If we think of this as awakening our authentic selves, fashion also needs to take on the path of breathing life into faded values. The yin to this yang is handcraft.

‘’The kimono is made to be worn by anyone who is attracted to it.’’ In order to fulfil its purpose, it needs a human body that can bring life into it. We often perceive garments and material culture as soul-less, when in fact they should be discerned as soul-ful. In order to shift this paradigm, fashion needs to be deconstructed and constructed in a new way. And then it hit me: is it only me who notices the resemblance between the silhouette of the kimono and the symbol used to illustrate the third eye chakra?

If we imagine the kimono as a representation of the human body, then the seven chakra centres are interpreted as the building blocks, each of which needs to be reconstructed if we want to build a resilient way of living.

Clothing, in its essence, represents a basic need: we need it to cover our naked bodies. If we think of this as a shield to the human body, it becomes our shelter. This sense of grounding corresponds to the first chakra: the root chakra. If we reimagine for a moment this energy centre, it signifies a sense of belonging. Just as we know our origins, it is equally important to look into where garments come from.

In other words, this shift would rebalance the root chakra of fashion. In this case, the intricate textile of the Biru kimono comes from a small village called Pringgasela in East Lombok, Indonesia. Rescued from a Balinese second hand market in Tabanan, discarded jeans have been rejected by previous owners and welcomed by Southeast Saga. This creative expression to otherwise forgotten garments carries a key message that can correlate to the sacral chakra. The second chakra governs emotions. When blocked, creativity becomes unbalanced and this is crucial if we look at it from the perspective of rapidly shifting trends.

However, when balanced, it promotes creative expression, which here is translated into upcycling cast-off products. A colour that stands out as an accent to the Biru kimono is orange, which interestingly enough is the colour that corresponds to the sacral chakra. Breathing life into material culture is a collective effort which is all about inclusion.

Southeast Saga’s kimonos are a collaboration between natural dye makers, Indonesian craftswomen and seamstresses, as well as a Scandinavian heritage with a commitment to conscious living and enduring aesthetics. Each ‘nourishing mosaic’ is unique, which unlocks a deeper level of authenticity. Charging clothing with a conscious human touch is a celebration of usage, as it implies that roughness, unevenness and irregularity may be experienced and are all integrated into the concept. This is a direct link between one’s sense of personal identity, which is actually the basis of what corresponds to the solar plexus chakra. Just as it is considered the powerhouse of the human body, an aesthetically resilient object is the powerhouse of fashion. Such an item encompasses material, physical and sensuous stories: the time that has been put into the object, the conceptualizing and constructing, as well as the time meant to be spent using the object.

By awakening this sense of connectedness to the world, the receiver becomes one with the object they wear: here the heart chakra is balanced. The key to awakening the heart chakra of fashion largely lies in phenomenology: understanding the story behind a designed object means gaining insight into contexts, connections and essentially re-attachment to our physical surroundings. Would all these connotations be known to the general audience unless communicated properly? We are so used to consuming that we rarely look for intention behind clothes. In order to set a message across, transparency is key and this is where fashion struggles the most today. The ‘throat chakra’ of design language needs a serious unblocking. In its essence, this energy centre is responsible for expressing oneself, while also hearing and being heard. Southeast Saga proposes a new way of looking at transparency to fashion. It isn’t solely about knowing where your clothes really come from and who is behind the product. It is more about understanding that if you want an artisanal object that tells a story, you need to wait for it to be manufactured especially for you.

Speaking of awakening our inner wisdom and listening to our intuition, the Biru kimono spoke to me the most. I always believed in signs, so I guess I was drawn to this particular kimono due the indigo shades I saw during my sound healing. ‘Biru’ also means ‘blue’ in Balinese, and blue is the colour of the third eye chakra. Here, I find correlation that subconsciously drew my attention to the so-called ‘third eye’. This is the energy centre where we create our own meaning to life and it acts as our internal compass. Resilient items would not be called resilient unless placed value into. And the way to place value is by charging it with our own meaning, besides the already given one. Thus, we become one with the object and we build a deeper emotional attachment to the garments we wear.

Ketut was right. In order to build a resilient way of living, each individual imbues and charges material culture with their own interpretations. Those are deeply rooted in their experiences, emotions, stories and values. Rebalancing our internal energy centres stimulates a flow that undoubtedly translates into the physical world. Seeing the colour indigo was the trigger that led me into looking at the meaning behind chakras and I became interested in how I can apply this knowledge in material culture. Did you notice how the Biru kimono is primarily blue, the colour of the ajna? If the third eye chakra of fashion is handcraft, then rebalancing the flow of the rest of the energy centres would follow. ‘’Just repeat the sound ‘om’ every time you need to find your balance,’’ Ketut told me. He was once again right, if you really look at it, you will also find the ‘om’ in kimono, you just need to change your perspective.

This article is written by Mila Nedkova, one of my amazingly talented former students.

A bit about Mila, in her own words:

Dear reader,

People generally introduce themselves as their job title or their degrees. However, let me introduce myself a bit differently. I am the daughter of two wonderful people: my mother was a former dancer and my father was a former banker. I am also the younger (and very proud) sister of a lawyer. From my mother I inherited the fire in my soul and my father passed on to me his stubbornness.

My favourite book as a child was Pippi Longstocking. Likewise, I grew up to be an old soul, an endless dreamer and a recent discoverer of a spark I promised myself to follow. People often tell me I live in my own universe and with this I must agree. My dream is to open up to the world the door to my Villa Villekulla and let fellow explorers take a look into my rebellious mind and tag along my adventures where I share my values in the form of stories. Oh, and before I forget: by conventional beliefs I have a bachelor degree in sustainable fashion design and a master in critical studies of design. I currently work as a fashion stylist and my intention is to make this creative side of me join an intricate dance with writing on real design values. I remember couple of years ago someone told me not to do it and think twice about writing. But I am the stubborn daughter of a dancer.

And, an additional intriguing detail: guess what I named the house my family and I recently finished building here in Bali? Yes, you’re right: Villa Villekulla.

We are all connected, through our thoughts and actions. Our pasts encounters and interactions are intertwined with our present manifestations and sentiments. I am grateful that Mila reached out to me and am looking forward to our collaboration.

December 14, 2023

The art of deconstructing and upcycling discarded garments in order to give them a rebirth

Whereas recycling waste materials, like discarded plastic or textiles, involves the process of breaking down by shredding or melting the cast-off products in order to create a moldable, usable basic material, upcycling implicates re-designing and improving discarded products, maintaining the essence or the core of the product. Consequently, the upcycling of a garment involves giving the discarded piece new life, or a rebirth.

Upcycling of unwanted garments makes particularly good sense, as the fashion industry is known as one of the most polluting industries in the world. Not least because many of the large mainstream brands operate with a business model that involves overproduction in order to avoid having to reorder more items of a potentially popular style, which, as a side note, leads to endless outlets that continuously undermine the value of clothes. In other words, it is more lucrative to produce too much than to run out of a popular style, even if this involves having to throw away or burn the surplus stock, which says a lot about the cost of work and production in the factories used as well as the price of virgin-materials. This notion implies that when talking about textile-waste we are not only dealing with the millions of tons of clothing that consumers worldwide throw away every year because they are done consuming them. We are also dealing with “un-consumed” clothes. Subsequently, it seems that there is an almost endless source of materials — deadstock or second-hand garments — for the design-practice of upcycling garments, which most certainly makes this a legitimate reason for designing “new” things.

Reborn Kimonos from Southeast Saga

Reborn Kimonos from Southeast Saga Upcycling often includes redesigning or improving functioning garments or garments that are in good shape, but have been discarded due to perceived obsolescence, shifting trends, or overproduction. The majority of garments that are discarded are not worn out—maybe they have been used just a few times, or maybe they have never been used at all—they are just no longer timely and trendy. The act of upcycling garments—as well as other things for that matter—provides the sustainable designer with a creative dogma that can provide direction and beneficial limitations in the design process.

The upcycling dogma goes somewhat like this: only discarded garments or fabrics can be used, and the overall purpose is improving the quality of the cast-off products. The latter is important. The word upcycling contains an inherent appeal to upgrade, develop, and recover something that has been rejected, and hence an appeal to prolong its lifespan. In the book The Upcycle (McDonough and Braungart: 2013) one of the chapters is initiated by a very telling anecdote:

In Akira Kurosawa’s film Dersu Uzala, a group of travelers sets out to survey a region of harsh, wintery Siberian forest, territory impossible for them to navigate on their own. They encounter Dersu, a wise nomadic tribesman who knows the area and agrees to serve as a guide. During a storm, Dersu leads the group to a hut in the forest. Dry wood has been laid there already, left behind by the last visitor. Because of the previous visitor’s fore- thought, the travelers can light a fire and warm themselves in the devastating cold. When the group is ready to leave the hut, Dersu is astonished to discover they would do so without stocking a new supply of dry firewood for the next person seeking shelter. How could they think of doing that? Why would anyone do such a thing? From Dersu’s perspective the travelers should leave the place as the found it—in fact, better than they found it: upcycled.

Upcycling is about improving and enhancing. And, as the above quote beautifully captures, the act of upcycling includes an abundant mindset and a wish to add value to the world and improve lives. That is the core of upcycling.

The upcycling of things can involve mending worn out parts of an object or replacing damaged elements, but it can also imply more radical alternations of the original piece, or “hacks.” Upcycling hacks can be beneficially implemented into things that are perceived as obsolete due to their non-trendy look, which is often related to fashion. Hacking a discarded piece of clothing can implicate disassembling it into modules or fragments, and thereafter re-establishing it in a new manner.

Reborn Kimonos from Southeast Saga

Reborn Kimonos from Southeast Saga The thought of disassembly is closely related to deconstruction; a term, which has its roots in postmodern, semiotic philosophy, and is linked to the French philosopher Jacques Derrida (1930–2004).

To deconstruct is not to destroy. Deconstructing implies undoing something, which, in the case of upcycling garments could be the undoing of the trend-related look that makes the garment appear obsolete. Deconstruction implies breaking something down into parts in order to gain a thorough understanding of the components it is made up of. In Derrida’s philosophy, deconstruction is however not related objects, and certainly not to fashion, but to philosophical texts. In his seminal work Of Grammatology Derrida closely examines and deconstructs the language and logic of various canonical texts by Plato, Rousseau, Kant, Hegel, and Nietzsche. The word grammatology means “the scientific system of writing,” and Derrida seeks to disclose the ambiguity and complexity of the texts he analyses. Briefly put, Derrida’s deconstructivism is built upon a need to understand in order to re-evaluate Western assumptions, truisms, and values linked to binary oppositions, which typically contain an inherent hierarchy that uncritically favors one over the other. Examples of such oppositions are structure versus creativity, masculine versus feminine, white versus black, etc.

Deconstruction involves determining what is “wrong” with a given text — or, in my usage of the term, a discarded product — and, in so doing, detecting whether it is characterized by poorly built-up arguments — badly made components or materials — or internal inconsistency and taken-for-granted assumptions — an unendurable composition, which makes the overall expression unsustainable — and finally potentially undoing these “errors” in order to reconstruct it.

In the case of upcycling garments, which have been discarded because they are experienced as obsolete, the process of deconstruction can involve identifying the “modules” or components of the garment that don’t work aesthetically on a long-term basis, due to the fact that they are trend-based and fleeting. Once the trend-based components of the garment have been uncovered, these should be removed or hacked — and hence, radically changed — after which point, the upcycling or upgrading of the garment into an anti-trendy, sustainable, long-lasting piece of clothing can materialize.

The process of uncovering the product elements that are perceived as obsolete has similarities with the process of eidetic reduction. Briefly put, eidetic reduction involves uncovering the core qualities of an object. In the case of upcycling and the process of eliminating the components in an object that don’t work aesthetically on a long-term basis, this method can help determining which parts to maintain and which ones to hack or remove in order for the object to still be perceived as usable and functional.

The process of upcycling should lead to an improved, well-functioning object that is aesthetically sustainable and resilient. Even if the upcycling process results in radical changes of the original object, the outcome should still be functioning, and it should be charged with aesthetic qualities that ensure longevity.

This is exactly where the process of eidetic reduction comes in handy; eidetic reduction can reveal the core of clothing or clarify what it takes for an object to be described as a garment. The outcome of the hack or upcycling might be asymmetrical or complex in its expression, and the design process might involve altering an object from being a shirt into being a dress, or from being trousers into being a skirt or a kimono, but while the trend-based, fleeting look should be removed, the core or the “garment-framework” should be preserved — it must still be wearable — and components that can ensure long-term aesthetic nourishment should be added. This could involve adding tactilely stimulating elements or visually intriguing features, or it could manifest in a cleanse of the overall expression and thus an emphasis of the beauty of simplicity.

No matter how the upcycling process manifests, the outcome should be an improved, well-functioning garment that can be used for various occasions or provide the wearer with flexibility, which could materialize in an adaptable fit that enables adjustments over time in order to accommodate bodily changes.

Reborn Kimonos from Southeast Saga

Reborn Kimonos from Southeast Saga Deconstructivism is not only linked to language and logical argumentation in philosophical texts, it is also known as a postmodern architectural movement. This movement can be described as “anti-architecture” in the sense that it is characterized by distortion and fragmentation, as well as by deliberately stirring up the “common rules” of architecture. The result is characterized by fragmented constructions, and an absence of symmetry and harmony.

Similarly, the upcycling of clothes that used to be fashionable and now have been consumed and rejected might lead to “anti-design” in the sense that upcycled garments adhere to anti-trends rather than trends. Anti-trendy upcycled clothes might, in order to embody longevity, explore unpredictability and asymmetry, seeking to arouse the curiosity of the recipient and appeal to her/his wish to engage in visual and tactile explorations. An upcycled garment might be characterized by complexity and investigate the limits of what a piece of clothing can be and look like. The aesthetic receiver experience connected to it is characterized by being open and explorative.

The process of hacking discarded garments with the purpose of prolonging their lifespan and upgrade their value, which I am exploring in my writing and in Southeast Saga as a legitimation of designing new things in a world overflowing with unwanted stuff, can beneficially make use of the explorative design-principles from architectural deconstructivism.

The art of deconstructing cast-off apparel — that is still intact but is perceived as obsolete by the owner — involves pinpointing the trend-based part of the product that has made its existence transitory. In that sense, deconstruction can be described as a sort of reverse engineering of an item: it involves dissecting it or splitting it up into its core components (which eidetic reduction can help one do) and determining the trend-related, fleeting part of it, or the part or piece of it that doesn’t work anymore and makes it feel obsolete to the user. The obsolete part should then be removed, and the process of upcycling and rebirth can begin. This involves reconstruction with the aim of creating a long-lasting, sustainable new object. The part of a discarded piece of clothing that is perceived as obsolete might be its shape, its color or color combination, its trimmings, its fit, its silhouette, its composition, its material combination, or its texture. It might be related to its lack of flexibility or multifunctionality. Or, it might be linked to its blandness; if that is the case the notion on anti-design inspired by the architectonical deconstructivism might come in handy, which could involve working with asymmetry and distortion. Whatever the perceived obsolescence is associated with, it is most likely linked to the fleeting nature of fashion trends that dictate a new look multiple times a year.

Upcycled garments embody a new kind of luxury that revolves around creativity, uniqueness, and imperfections. Imperfections that radically upcycled garments express are not defects, and they don’t imply that something is malfunctioning. Upcycled garments are fully functional, imperfectly nourishing, challenging, and often asymmetrical.

December 7, 2023

The Slow Revolution Anno 2023-24

Can sourdough bread baking, long-reads, and growing tomatoes be considered acts of civil disobedience?

800 page novels, 3.5 hour blockbuster movies, 4+ hour podcasts… Not to mention homesteading social media accounts with millions (and millions) of followers, slow food journaling version 2.4 promoting sourdough bread-making, old-school pickling and marmalade making — what’s going on?

Are we experiencing a new and evolved slow revolution? Is this the beginning of a silent revolt against TikTok and other kinds of mind-numbing fast-pace entertainment that encourages overconsumption and is destroying our attention span?

Photo by Artur Rutkowski on Unsplash

Photo by Artur Rutkowski on UnsplashI started noticing these changes a couple of years ago. But the past half year they have been impossible to ignore. The podcasts I listen to that used to be around 30–45 minutes long are now easily 3.5–4 hours — allowing for a much, much more in-depth conversation as well as for small-talk and random anecdotes; I just finished reading my second 800+ page novel this year (and have read several 600+ page novels as well); and I am following more and more homesteading and slow-family-farming instagram accounts that somehow nourish me, aesthetically and emotionally (and I am clearly not the only one. Several of these accounts have millions of followers).

Furthermore, I have started enjoying my good old record-player again. The feel and the sound of the vinyl is just so much more satisfying than listening Spotify on my Sonos. It is the rawness and imperfection that makes the difference (alongside the offline-ness).

Photo by Cyrus Crossan on Unsplash

Photo by Cyrus Crossan on UnsplashTo answer the question in my subtitle: Can sourdough bread baking, long-reads, and growing tomatoes be considered acts of civil disobedience?

Yes, they certainly can!

In a world governed by overconsumption, capitalism, and reduced attention spans (making 10 second TikTok videos the preferred source of entertainment), self-sufficiency, long in-depth podcast conversations, lengthy novels (and movies) characterized by expansive character- and environment descriptions, and slow cooking most certainly are ways of revolt.

This revolution is accompanied by a rise in handmade products, which has given birth to a new idea of what luxury is. Luxury in the new age of slow living is not flashy. On the contrary actually. Luxury is interlinked with authenticity; with real people talking about stuff that matters to them, and often about how they broke free from the 9–5 rat-race. It is furthermore interlinked with time; with having time to read that 800 page novel, to listen to the 3.5 hour podcast, to bake sourdough bread, and to grow tomatoes.

Luxury is also closely connected to transparency; to purchasing (or perhaps more correctly, investing in) products that are made in an ethical and sustainable way, and in products that last and can be repaired — clothes for example that decay in an aesthetic manner and that can be mended without them looking like old rags. And herewith a new concept of what it means to be well-dressed has emerged. Being well-dressed in the new age of the slow revolution does not mean to wear clothes from well-known luxury brands, flashing one’s purchasing power. Rather, being well-dressed includes wearing handcrafted garments, flashing creative mends, and investing in handcrafted garments, upcycled clothes or vintage items.

It appears that many of us have had enough. Enough shallowness, enough empty calories in the shape of mindless entertainment, enough smoothness and sameness, enough each-to-their own, enough ridiculous TikTok shorts of tripping cats and chewing people and lip syncing and make-overs, enough consumption — as in buying stuff, going through it and discarding it again — and enough homogeneous, mass-produced convenience-foods and fast fashion products.

The slow revolution anno 23–24 is about reclaiming our civil rights to celebrate diversity, to engage in meaningful conversations, get aesthetically nourished by well-made things that last, to age with grace, to celebrate nature and seasons and the rhythms of life, and to have time enough to engage in reading, cooking, gardening, talking, playing, and listening to vinyl records.

Kimonos from Southeast Saga’s Reborn collection

Kimonos from Southeast Saga’s Reborn collection

November 20, 2023

Rewilding the design object

Rewilding the design-object should ideally be a bit like reintroducing the wolves in Yellowstone Park (which I wrote about in this article). It should be a celebration of letting go of control and allowing for natural processes to take place.

In order to create rewilded design-objects, the designer must initiate or curate the aesthetic design experience, and then dare to step back, allowing for the object to develop in the hands of the user, and for the aesthetic experience to cultivate and alter as the user’s stories and interaction infuse it.

In a sense, finishing a design-object completely before releasing it into the world is a little peculiar, if the object is made to be used, which I assume design-objects generally are. If something is completely done, with nothing to be added or taken away, the process of usage can only allow for deterioration moving toward a quickly approaching end.

Perfectly finished garments with no flexibility and no unevenness, and tables or kitchen counters with smooth, glossy surfaces generally tend to get less appealing when used, and wear and tear leaves unflattering marks, stains, and wrinkles. Such design-objects are at their peak when released into the world, and the user-phase becomes one long regression toward final rejection.

Consequently, such design-objects can be described as closed: closed off to usage and closed off to human attachment. Scratches and stains are not flattering additions to the finished or closed design-object.

When you do a simple search on the internet and read about what a product’s life cycle involves you will quickly come across four stages in the product’s market life: introduction, growth, maturity, and decline of demand.

The growth stage appears noteworthy and intriguing in the light of the above thoughts on the closed design object. Growth involves an inherent development potential that could comprise an antidote to the closedness.

However, growth in the product life cycle has nothing to do with opening up the product and including growth potential in the user phase. It implies that after a product is introduced to a market its popularity initially grows, but then, shortly after, reaches the maturity phase — when things become mainstream — and finally the decline phase sets in.

In other words, it is anticipated as a part of the product development that all products have a short life, and that the consumer within a limited timeframe — after a short honeymoon phase in which the product is valued and cherished — gets tired of the product and most likely discards it to make room for “falling in love” all over again with new products.

This mechanism is obviously good, dry, fast burning wood that feeds the fire of overconsumption. The planned obsolescence of a newly made product or the inherent unflattering decay, which can be concrete and physical in the sense that the product, might no longer be well-functioning or intact after a defined period of usage, and perceived in the sense that the product might still be intact, but experienced as obsolete due to the fast-shifting winds of trends and fashion, must be challenged by new sustainable design approaches and new consumer demands.

Growth should be integrated into the user-phase and should be synonymous to flexibility and progress, and maturity should associate aesthetic decay and beatifying jaggedness.

Why not design objects that are open to usage? Objects that flourish or grow better, more intriguing, and more beautiful throughout the user-phase, as the process of decay leaves its traces. Why not incorporate the process of usage into the design practice, and thus consider the user phase the phase of completion, or the phase in which the design-object obtains its true shape, identity, or true “colour”?

Similar to the release of the wolves in the Yellowstone Park, this way of approaching product development would require letting go of a degree of control.

Of course, the designer has—and should have—intentions with the design-object created, and of course, it should be charge it with aesthetically nourishing components and storytelling to ensure an anchoring of the receiver’s connotations so that they match the design concept and intentions.

But, as a part of rewilding the design-object the designer must dare to let the user phase take part in shaping the object and dare to allow for diversity to flourish. Ideally open and slightly undeveloped design-objects should be released into the world; objects that are open to wear and tear, to usage, and accessible to all the diverse, multifaceted stories that they will be charged with while being a part of the user’s life.

The aesthetics of the closed design-object are a celebration of perfection and smoothness, the resilient aesthetics of the open design-object are a tribute to rawness, wildness, wear and tear, and anti-homogeneity.

October 31, 2023

The Path to Interconnected Living

When we think of our milieu, we tend to look at it in terms of solely our human made environment — with all the infrastructure, constructions, and social and cultural conducts this entails. Within this environment there is a lot to learn for children and teenagers; there are a multitude of ways in which they must be cultivated in order to fit in and become decent citizens, neighbours, consumers, employees or employers, colleagues, friends, and husbands/wives.

Furthermore, the cityscapes we have created require lots of skills for young humans to navigate: they must learn how to steer traffic, first on foot, later perhaps on bicycle (depending where they grow up), and even later on or in motor vehicles, as well as in public transportation (if that is the dominant source of transport where they live).

These are of course all important skills and competences that are necessary in order to master a late-modern environment. But what about our natural environment? Why don’t we learn how to thrive and survive in nature? Why is there so little (if any) focus on fostering a kinship and living in harmony with our natural environment? Is it because there is hardly any wild nature left on this planet, and therefore this appears unnecessary? Or is it because we seem to have agreed that cultivation involves creating a distance to our natural surroundings; almost as if this distance (that tends to grow bigger and bigger the older we get) is a prerequisite to our sophistication and civilization?

Whatever the reason, the result is that we are more or less completely lost when it comes to navigating and surviving in wild nature. And because hereof nature scares us, feels messy and dirty to us, and is something we are disassociating ourselves from and something that we have learned to view as a resource for us to use, a commodity that we can mould and shape in whichever ways we want (in order to cultivate it or aestheticize it).

Consequently, if we were dumped in the middle of nowhere, in wild, flourishing, diverse, disorderly (yet perfectly harmonised) nature we would be totally lost. We have completely abandoned the core skills of our ancestors such as navigating by taking notice of the sky (as a parenthesis, my youngest son is intrigued by this notion at the moment, and practices every day telling the time by looking at the sky; a skill that he now masters to an extend that he has started questioning why one should ever wear a watch), creating fire, using wild plants for foods, medicine and shelter, protecting ourselves from animals by making sure our paths don’t cross (instead of killing them) etc. We have sacrificed these skills on the altar of comfort, cultivation, and material possessions; a sacrifice that is bigger than we are aware of. Because this exact sacrifice is what drives our unsustainable behaviour and is generally why we continue to pollute, over-consume and take advantage of nature.

Furthermore, this sacrifice has led the vast majority of us into despair; to a feeling of desolation and of never feeling satisfied.

Why?

Because during the development of distance between human beings and between us and our natural environment that characterises modern time, we have forgotten that we too are nature. Perhaps we have even told ourselves that our religions, our gods, preach human superiority and hence, that our supremacy is law. But is it law? Are we really free to use and exploit endlessly? Is that what genuine freedom feels like?

The arisen slow movement and the increasing number of nature retreats, glamping sites and nature shelters, as well as the growing focus on nurturing our relationship to nature in literature (there is an almost Wordsworthy nature-romanticism going on here combined with a scientific approach to human-nature interconnectivity that is exemplary presented in The Overstory by Richard Powers) shows that somewhere deep down we know. We know that something fundamentally nourishing and wholesome is missing in our fast-paced, sheltered, urbanised, consumerist lives. We know that we need a balance.

And so, we seek to harmonise our lives by adding a “stock cube” of condensed nature-experiences in the shape of the occasional forest lake swimming, nights in a nature shelter or weekend getaways to remote off grid resorts.

But the true connection is still missing. And we wonder why.

While we are moving slowly through that fresh forest lake, and while we are sitting by the campfire surrounded by fragrant, dark nature we might feel a glimpse of connectivity, and we might get a rush of an unfamiliar sensuous satisfaction that isn’t thought-based nor interlinked with consumption; a profound feeling of belonging and of beauty — raw, unfiltered beauty. But once we leave the setting and go back to our convenient, sheltered lives the feeling is gone and has left us with nothing but a brief sense of relief. The momentary wordless experience of being at home in the world that characterises the sublime aesthetic experience stays with us for a bit, but the vibrations therefrom quickly fade away once our beeping phones and growth mindsets start invading our thoughts again.

To truly develop our sense of connectivity — to each other and to nature — through our sensitivity to beauty; through appreciation of the magic that surrounds us and is within us, we must incorporate it in our daily lives. Not only in weekend getaways, but in our everyday whereabouts. The sense of place and respect for our environment will grow from here.

October 21, 2023

The Sustainability Machine

In the first two chapters of my book Aesthetic Sustainability, I discuss the difference between the beautiful and the sublime aesthetic experience. And in relation to the investigation of the beautiful, I examine the functionalist approach to design and architecture and its roots in ancient Greek philosophy.

Allow me to briefly dive into this design approach here, as it is of great relevance to the overall theme of this article:

To Plato (c. 428–348 BC), a physical object can be considered beautiful if it clearly expresses the form or idea that gave birth to it. A beautiful chair, according to this way of thinking, is a chair that is clearly recognizable as being a chair and that is good at being a chair. There is thus a kind of precision to beauty. Beauty is precise and unambiguous in its expression. Beautiful physical objects are clearly expressed and decoded as what they are, at the same time as they are good at being what they are.

Such a viewpoint contains the germ of a functionalist approach to thinking aesthetics. Functionalism, a term for defining the style and historical context of early 20th century design and architecture, is dominated by simplicity and objectivity, understood as form being subservient to function.

Custom-made sofa by Southeast Saga

Custom-made sofa by Southeast Saga“Form follows function” is a well-known adage ascribed to functionalism, which aimed to cleanse form of anything but the absolute most necessary elements.

The famous phrase was uttered by the American architect Louis Sullivan (1856–1924), and it was in direct opposition to the organic decorative idiom of the previous art-nouveau period. The Bauhaus architect and furniture designer Marcel Breuer (1902–1981) called his chairs “sitting machines” and hereby gestured to the ancient idea that a chair is beautiful if it is good at being what it is. A chair becomes a sitting machine insofar as it is good to sit in. The form and expression of an object are thus inferior to its function (unless, of course, expression and aesthetics are a part of defining the comfort and longevity of a chair).

A sitting machine! A phrase that has an architectural counterpart in Swiss architect Le Corbusier’s (1887–1965) term living machine, which he used to describe his functionalist concept homes. I’ve always loved these terms; there is a liberating straightforwardness about “calling a spade a spade”. Because honestly, if a chair is not good at being a chair and hence to sit in and if a house is not good at being a living space, then why create them in the first place?

Of course this is not as unambiguous as it sounds. A chair, in our world of status-symbols and lifestyle trends, is so much more than just a chair. And a house too. But this is exactly why calling a chair a sitting machine and a house a living machine is so ingenious. Because, despite status symbols and trends being even more predominant now than during the functionalist design era, let’s not forget the most basic functions and aesthetically nourishing qualities of the objects we invest in and surround ourselves with. Doing so might encourage an increased focus on usage rather than consumption.

The beauty of allowing function to shape aesthetics is obvious when looking at Breuer’s sitting machines and Le Corbusier’s living machines: there is a nourishing simplicity to these “machines” and a very pure sense of quality that can beneficially be re-actualised as a part of current sustainable design efforts. The precision of the functionalist design approach can add a rejuvenating design strategy to a world overflowing with unwanted things and product waste. Because, if things have to be good at being what they, if they have to be precise and clear about the function they fulfil in order to have a raison d’etre, then there is no design-argument in the world (not even one based on growth and “more-wants-more” arguments) that can justify the creation of more insignificant knick knacks or more trend based rags.

Reborn, upcycled kimonos by Southeast Saga

Reborn, upcycled kimonos by Southeast Saga

In Aesthetic Sustainability I explore the benefit of narrowing sustainable garments down to their core-essentials by reducing them to keep-warm-and-dry-or-sheltered-from-the-sun-or-heat machines, before adding anything trend-/fashion-related to them. It appears that the experience of something (an object of any sort) being obsolete is dependent on trends rather than functionality, and that our global environmental crisis is therefore determined by eliminating this culturally constructed mechanism.

Inspired by the past functionalist design-heroes one could ask: what kind of machine do we need now?

We have plenty of sitting machines; plenty of stuff, plenty of things to use and go through, plenty of consumption-options. Maybe what we really need is a sustainable living machine? Or do we rather need a machine that can foster connectivity, empathy, and emotional intelligence? Or a machine that can encourage us to focus less on consumption, less on mindless entertainment, less on trivial pastimes and on social media likes– and more on nourishing heaviness and enduring aesthetic experiences?

Maybe our present day design heroes need to focus on how to make use of the largest material-resource we have right now, namely waste materials from discarded objects and unsustainable single-use products, or how to create new sustainable, perishable materials that don’t pose a threat to our ecosystem?

Detail from Reborn kimono by Southeast Saga

Detail from Reborn kimono by Southeast SagaSustainable resiliently aesthetic objects are sharable, durable, and they contain a certain degree of heaviness.

The term heaviness often connotes something dreary or gloomy, however, here it refers to meaning, substance, and stability and challenges. In order to live sustainably we must invite more heaviness into our lives; meaning, more substance, more stability as well as more significance and challenges.

Resiliently aesthetic objects are charged with heaviness in relation to the undertones, associations, and feelings that they awaken in the receiver. The sensations that are stimulated by an aesthetically resilient object are heavy in the sense that they don’t pass immediately — they linger.

However, the heaviness that the aesthetically resilient object is infused with is also very hands-on in a physical, phenomenological kind of way.

The hands-on heaviness that the resilient object encompasses consists of physical, material, sensuous stories; stories about the time that has been literally put into the object, which might even be discernible on the object’s surface; stories about the time that has been spent conceptualising and constructing or shaping it. Stories that leave nourishing traces on the object surface and invite usage rather than consumption.

Hand-embroidered signature, a little hello by the creator for the user (by Southeast Saga)

Hand-embroidered signature, a little hello by the creator for the user (by Southeast Saga)