Reframing the Way We Design, Use and Consume Things

In sustainability debates the three Rs: Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle are often featured as a useful sustainable trinity.

However, I always solely focus on reduction rather than reusing products or product waste and/or recycling when working with sustainable design.

My focus on reduction is not meant as an attempt to underestimate the value or importance of the other two Rs, but no matter how good we are at recycling waste materials and using them for new products, it still requires large amounts of natural resources to do so. And, no matter how efficiently we reuse discarded objects by implementing take-back systems, it doesn’t eliminate the fact that there are simply too many unwanted things in the world.

Focusing on reusing and recycling can be dangerous, as it tends to create the mentality that overproduction and overconsumption is justifiable, because there are systems to take care of our excess things when we no longer want or need them. However, the existing systems cannot cope with the overload of goods being produced and discarded.

Reducing consumption (and encouraging reduced consumption through design) is essential in my opinion and a central part of my research — but furthermore our times call for something more radical on top hereof. And hence, I have added a new R to the trinity, namely Reframe.

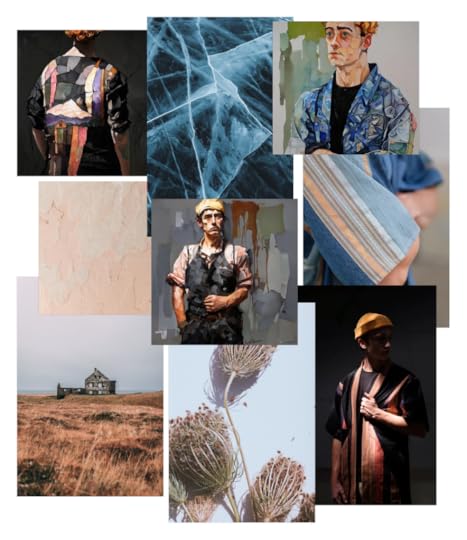

Southeast Saga Reborn Kimono, detail

Southeast Saga Reborn Kimono, detailReframing concerns first of all rethinking and reevaluating the way we look at objects, at things — at all the beautiful, functional, and not so beautiful and not so functional objects we surround ourselves with. Reframing involves a phenomenological approach to our physical surroundings.

When I write phenomenological, I mean a focus on our bodily, physical, tactile interactions with the things in our surroundings, rather than a symbolic one. As one of my favourite thinkers, Danish artist and philosopher Willy Ørsov (1920–1990) puts it: “An object is a frozen or fixed event”.

Let me explain.

The majority of the things we discard are not discarded because they no longer work, or because they are worn out, broken, torn or faded. No. Most discarded things are still perfectly fine, in the sense that they still work in the intended way: they can still be worn and used in the way they were designed to be. Of course one of the reasons for rejection is likely that they are made in a way that makes them impossible to repair, mend or update. But the main reason that we discard our things is that they are no longer trendy, or that they no longer nourish us aesthetically. The reason for the rejection is in other words mainly interlinked with their symbolic value rather than their functional, phenomenal value. So, when reframing the way we design and produce things and the way we consume things, un-symbolising them is one of the crucial steps!

The symbolic side of an object, or the associations that an object might trigger, is, according to Ørskov, only a secondary quality, whereas the primary quality concerns the object’s purely physical and spatial existence or presence. And therefore, if a sculptor (or a designer, for that matter), as the point of departure for the creative process, has decided the “fate” of the object based on its symbolic value, she is, according to Ørskov, working in a reverse manner, and is thereby at risk of creating fleeting objects that can only be described as what Ørskov calls “fashion phenomena” (which is a strictly negative designation!). The durable and truly effective and aesthetically nourishing object is in conflict with fashion and trends. And hence with consumption.

I recently read a very thought-provoking book by Korean-born philosopher Byung-Chul Han called Saving Beauty. Han is occupied with how our late-modern need for smoothness and convenience has destroyed beauty in the sense that beauty has turned into nothing but blandness and easily digestible, pleasurable simplicity.

Han’s book on beauty starts like this:

“The smooth is the signature of the present time. It connects the sculptures of Jeff Koons, iPhones and Brazilian waxing. Why do we today find what is smooth beautiful? Beyond its aesthetic effect, it reflects a general social imperative. It embodies today’s society of positivity. What is smooth does not injure. Nor does it offer any resistance. It is looking for Like. The smooth object deletes its Against. Any form of negativity is removed.”

No, Han is not a big fan of Koons. He later writes that Koons’ smooth sculptures cause a haptic compulsion to touch them, even the desire to suck them. This is not a good thing in Han’s world. Not at all. In order to save beauty — and reunite with all facets of beauty; not only the smooth ones, but also rawness, the anti-smoothness, complexity, the sublime — we must salvage negativity.

And I agree.

As I wrote in my book Anti-trend:

“The enduring aesthetic pleasure that the resilient design-object awakens in the receiver is reliant on changeability, on a degree of rawness, and on accepting that not everything can be controlled. The aesthetically resilient design-object is raw and uncontrolled in the sense that it is open to the traces that usage will leave on or within it; it is open to be molded and mended in ways that will fit the individual user, and it is open to the stories that are linked to traces of wear.”

The aesthetics of beauty in modern times equal smoothification. And the aesthetic of the smooth is embodied in Koons’ smooth, shiny sculptures: they lack negativity and are reduced to beauty, joy and communication. They are shiny as mirrors — and isn’t that all we want now-a-days? A mirror that we can meet ourselves in, admire ourselves in, be confirmed within (- otherness, rawness, decay, danger, diversity, negativity is absent). As Han. puts it: The beautiful is exhausted in a Like-it culture.

Perhaps reframing involves an anti-smoothification! The smooth and shiny beauty that Han revolts against doesn’t leave us with anything but a pleasurable meeting with ourselves; with sameness and self-absorbedness; with our own smoothified reflection (which is at times filtered until a state of unrecognizability). Our narcissistic late-modern culture really doesn’t need more of this smooth kind of beauty. No. What is needed is more heaviness (as I normally call it) or more negativity (as Han would call it).

This basically means that we need more friction and less “smoothness” and convenience. We need more purpose, more commitment, more heaviness and less insignificant lightness. We cannot justify using natural resources to create boring smoothness and convenience products that might on the surface appear to improve our lives, but really only make us feel more and more detached. From our natural environment, from true, raw beauty, and from each other.

We are used to considering the resources around us a commodity for us to use to create things; most of them insignificant, some of them even single-use, and a small percentage of them made for long-lasting usage and made to be aesthetically sustainable; meaning non-smooth, but made to be used and worn and to develop and decay in a nourishing, raw manner. We are used to considering nature’s resources inexhaustible.

But they are not.

Of course, they are not. No natural growth process can keep up with the speed at which we are cutting down trees and harvesting crops. We are running out of natural resources and are being forced to reframe our perspective.

One of Einstein’s theories was that nothing can be created or destroyed — only energy is moved around. If that is true (and I believe it is) then all the single-use and all the discarded products and the mountains of material waste that are currently being created are a huge problem. They dissolve energy and they block the flow of life.

How do we restore the flow of life? How do we reframe and alter the way we look at products, at consumption, at things, at resources, at beauty and our need for soothing self-affirmation and for convenience?