My precious

I am still in the process of writing a new book that I have named Uncultivated.

The book is built around negations of what I have chosen to call “the ten commandments of cultivation”. The intention herewith is to challenge taken-for-granted cultural and societal “truths” and assumptions and to promote a rewilding of the cultivated human being.

The ten commandments are the following:

We have to adapt and behaveWe are superior to animalsWe are separated from natureWe must be ambitiousWe must work hardWe must consumeWhat we cannot explain is not trueWe do not talk about deathWe must defeat decayWe must live in the nowIn this post I will share a short passage from Chapter 6: We must consume.

My favourite glitter shoes.

My favourite glitter shoes.  Waste art-installation made by arist Liina Klauss

Waste art-installation made by arist Liina Klauss We buy glittery, shiny things like were we magpies; collect and store them in our homes and wear them to decorate our bodies and flash our wealth and/or trend- or sustainability-awareness.

Consumption is so much more than just surviving — we are way, way past satisfying our most basic needs for food and shelter, and we consume more for entertainment and image than for functional, practical reasons. Even the consumption of food and drink has become a lifestyle-act: what and when we eat and even if we eat appears to be a part of our late-modern identity-creation (do we occasionally fast or do we engage in intermediate fasting on a daily basis — and hence withhold from consumption?).

Refraining from consumption when it comes to fast fashion items and other trendy knickknacks seems to have also become a nearly activist-like choice that signals consciousness and awareness (and is typically flashed on social media). But the act of refraining from consumption is for the privileged few only; for the once who can make a choice and decide not to consume — because they already have more than enough, and because they will never go to bed hungry unless this is a conscious decision.

(quick parenthesis here: when I write “they” I of course mean “we”, as I too am a part of the privileged few, who are fortunate enough to check in and out of consumption as if it were an existentialist quest.)

Photo by charlesdeluvio on Unsplash

Photo by charlesdeluvio on Unsplash My own photo of a very instagramable coffee

My own photo of a very instagramable coffeeIs being a consumer an identity? Late-modern, privileged consumption is interlinked with feel-good-experiences, acknowledging gazes and status symbols — well, in general with experiences rather than with getting fed and nourished (which you might initially, naïvely, think consumption was all about, given the word) or with being clothed and sheltered.

One could even raise the question: What are we if we don’t consume? (well, unless it is a conscious act of non-consumption, under which circumstances we are still acknowledging the driving force and the importance of consumption).

What is our purpose if we don’t participate in the spending party — if we don’t desire anything or rather any thing? Because, let’s not forget that you can desire something without desiring things, objects, shiny stuff. But it appears that we have forgotten how to do that. And this despite the fact that all our most applauded current lifestyle tendencies (slow living, simple living, minimal living) celebrate living with less belongings and with more awareness.

Photo by Uliana Kopanytsia on Unsplash

Photo by Uliana Kopanytsia on Unsplash Handwoven tablecloth by illusi

Handwoven tablecloth by illusi

During the pandemic consumerism even seemed to become more predominant as an identity creator. I guess it in a way makes sense, as it was one of the only possible ways to interact, communicate, and feel alive! So, despite the fact that most people were stuck at home and hence had no-one to flash their brand new phone or gadget to, and nowhere to go wearing their new trendy outfits, consumption via online shops skyrocketed.

What does that tell us about our consumption of things? If we don’t consume in order to be well-dressed when we go to work or to be up to date in the eyes of our peers, I guess the consumption of new, fashionable, tech-trendy, glittery things has become a crucial part of our personal well-being.

This reminds me of a sign I often pass in a shop in Ubud that says: “shopping is cheaper than therapy.

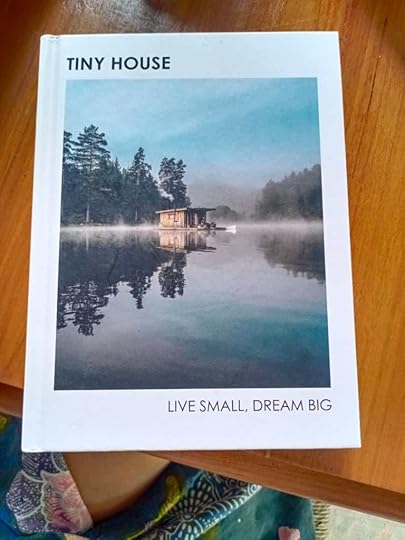

The dream of the simple life is a predominant theme in books, films and on blogs

The dream of the simple life is a predominant theme in books, films and on blogs

We need an alternative to consumerism. We need an anti-consumerist manifesto: one that will gain loads of followers and that can fill our late-modern lives with sense and direction. And we need it pretty much right now.

Why? Well, firstly, and obviously, because our overconsumption is a ticking bomb under an ecological disaster waiting to happen (or sorry, more correctly; a disaster that is already happening).

I don’t like to lay out doomsday scenarios. But overconsumption of insignificant, unsustainable short-lived things wrapped in cheap plastic meant to be thrown away after removal (but never really disappears) is one of the main sinners when it comes to pollution.

I see it every day here in Bali. There is trash everywhere! Piles and piles of plastic waste in the ditch edges, dirty brown rivers of plastic that flow down the sides of the mountains during rainy season, heaps of plastic flip-flops and toothbrushes and ice cream wrappers and shampoo bottles and polyester shirts are washed in from the sea and turn the beaches into colourful patchworks of disaster, discarded clothes from all over the world are shipped here and pile up in landfills while slowly emitting methane clouds into the environment, and the same goes for hard plastic waste from computers and washing machines and televisions.

The beautiful rice fields surrounding our house. You can see the wooden fence around our land in the background

The beautiful rice fields surrounding our house. You can see the wooden fence around our land in the backgroundMy family and I recently bought land here in Bali–a blissful little piece of heaven overlooking vast rice fields and with the majestic over 3000 meter high volcano Mount Agung towering in the background–and started digging up the soil in order to plant vegetables and herbs and fill the land with tall, slender bamboo, fern and fruit trees, my awareness of the immense plastic pollution that we are facing here in Bali reached new heights. There were generations and generations of plastic in the soil! I almost felt like an archeologist; digging through layers, observing the different states of my findings. The further down we dug, the more old, dirty, yet hardly deteriorated, plastic surfaced. Some of the plastic that had clearly been there for years had the texture of parchment paper and was thin and porous, but still far from a state of deterioration. There were also old clothes, primarily made from polyester or rayon. I found shirts, socks, trousers, even shoes.

Since there is hardly any infrastructure for waste management here in Bali, most people just throw their trash in nature. And, when a piece of land, neighbouring a village, is uninhabited for a while (like ours was) it tends to become the village dumpster.

However, one could argue that this is only the case in developing countries like Indonesia, and that in Europe or America or Australia (or wherever you, my dear reader might be located) it is different: there is an effective system for waste management; waste is even mostly recycled or used as fuel or in other ways made into a ressource. And while that might be true, there are two points I would like to point out: 1. a lot of the waste that ends up in large landfills here in Indonesia is shipped here from Europe or America or Australia (which, as a subtle side remark, is a whole new way of exhibiting colonialism), and while this might solve the waste-problem that overconsumption constitutes in developed countries, it only adds to the overall global inequality. Furthermore, just because waste is out of sight, it doesn’t mean that it is gone. We live on a globe of connecting continents and oceans, and hence the pollution that these landfills cause should be everyone’s concern.

Which leads me to the next point; that 2. even though the worldwide waste-problem is not visible in developed countries, and one will not experience buying land and finding decades of plastic waste layered in the soil (like we did here), there is no recycling system and no “turning waste into a ressource” procedure that can keep up with the amounts of waste that are generated every year. Last time I checked the number was an astounding 2.12 billion tons of waste a year! If all that waste was loaded on trucks they would go around the world 24 times.

So actually, while you might be appalled by the image of my plastic-polluted backyard, the layers of pollution I am experiencing in our garden and here in our small village (plastic bottles thrown on the side of the road, sweet wrappers in the fields, nappies floating down the river, etc.) is nothing in comparison to the mountains of waste the population of a similar sized European village generates.

The only difference is visibility.

Besides the immense pollution that overconsumption causes, there is another reason for our concurrent need for an anti-consumerist manifesto. A reason that is closely interlinked with my present plea for uncultivation.

Let me explain.

Consumption contains destruction, says French philosopher Simone de Beauvoir. Consumption means utilising or going through stuff: things and experiences. It is a destructive movement, because the act of consuming is wasteful and mostly conducted for momentary pleasure. The act of consuming constitutes a counterpoint to storing up and saving, which is what you do when you aim for, what de Beauvoir eloquently calls: stationary plenitude in-itself.

The term stationary plenitude in-itself makes me think of phrases like self-sufficiency, resilience, nourishing repetitions, independence, and autonomy. All of which are related to leading an justifiable, sustainable life.

Consumption is in other words in opposition to sustainability. It is a negative movement, which at its core is based on destruction. But nevertheless; despite its destructive nature, consumption is a crucial way of being cultivated in our late modern reality.

Photo by Haithem Ferdi on Unsplash

Photo by Haithem Ferdi on Unsplash My very worn-out jeans (and my little friend Ana’s feet)

My very worn-out jeans (and my little friend Ana’s feet)Reducing consumption radically–by for example investing in only a few things that are made to last, by mending and repairing one’s belongings, by buying secondhand clothes, or by wearing the same clothes to parties every time, by embracing or even elevating wear and tear as a sign of a loving bond to one’s belongings, or by not giving a s… if one’s phone is not the right shape or thin enough or up-to-date with whatever tech-trend is predominant, and by flashing this behavior and thereby paving the way for a new sense of luxury and new rewilded status symbols, can be an uncultivated act of civil disobedience that might inspire others.

(And maybe writing about one’s actions could outline the well-needed uncultivated anti-consumerist manifesto).