Allison Gilbert's Blog, page 4

May 29, 2020

Judith Warner shares memories of her dear friend, gone too soon

Judith Warner is a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress and a frequent contributing writer for The New York Times. Her latest piece, “The War Between Middle Schoolers and Their Parents Ends Now,” shares how the coronavirus lockdown is an opportunity for a reset with your children. She and I met in 2011 when she did a book talk for We’ve Got Issues: Children and Parents in the Age of Medication, which followed her best-seller, Perfect Madness: Motherhood in the Age of Anxiety. Her latest book is And Then They Stopped Talking to Me: Making Sense of Middle School, and how I wish I had this book when my children were living through those emotion-charged years!

In our interview, Judith shares memories of her dear friend Sally Kux, who passed away in October 2014 at age 52.

Because of the coronavirus outbreak, too many friends have lost loved ones. Perhaps you saw the front page of The New York Times dedicated to the 100,000 lives lost so far in the United States? In the print version, directly below the headline, is the powerful statement:

They were not simply names on a list. They were us.

The New York Times introduced us to the many lives lost with snippets such as; Fred Walter Gray, 75, “Liked his bacon and hash browns crispy” or Chad Capule, 49, “I.T. project manager remembered for his love of trivia.”

I’d like to think Judith’s friend Sally’s mini tribute might be: “Could do an unaided headstand.” I loved this conversation with Judith. I’m grateful for her willingness to share the below intimate memories of her dear friend.

Allison Gilbert: What one memento reminds you most of Sally?

Judith Warner: There are two. The memento that I keep literally closest to my heart is a heart-shaped, amber pendant that my friend Sally’s husband, David, gave me not long after she passed away. The other – hard to think of it as a “memento,” because it’s so large – is an antique French daybed, which we bought in Paris, where we lived right before moving to Washington, DC, and used as a living room couch. It’s a huge, bulky piece, with three high sides, and to get it into our small house, we had to remove our dining room window, because it couldn’t fit through any door. Sally loved it, and when she and her husband would come over for dinner, she and I would sit on it afterwards, each of us curled up in a corner, our legs stretched out toward the other. Our great pleasure was not-changing for dinner; she’d call beforehand and say, almost warily, “Are you getting dressed? I’m still in my yoga pants,” and we’d happily decide to stay in our yoga pants, which felt like a great liberation. As a result, it was very easy for us to get comfortable on this big, deep, high-off-the-floor rectangular thing that no one else knew how to sit on. We’d be cozy and sheltered inside the floral and stripe upholstery, and they’d pretty much have to drag us out of it at the end of the evening. We loved that.

Allison: Where do you keep the necklace, and do you still use the daybed?

Judith: I keep the necklace in my bedroom when I’m not wearing it. It lives in a beautiful little lacquered box that Sally brought back from Russia, where she spent a fair bit of time as a PhD student and a member of the State Department. The day bed is in the living room, near the fireplace now, though it was against a wall – the one wall in the house large enough to accommodate it — when Sally and I would sit there together. I have to admit, I don’t think I’ve sat on it since she died. I can’t get comfortable.

Allison: What is the most satisfying way you’ve developed for keeping Sally’s memory alive?

Judith: Yoga. Sally was devoted to yoga. There are pictures of her doing a headstand – unaided – two weeks before she died. And there’s another from the same day where she’s doing child’s pose on a mat with an oval of light around her, as though the heavens were signaling that it was almost her time. Right after she passed away, a bunch of us met to do yoga, led by Kelly, the woman Sally always practiced with, and we felt really strongly that she was with us. It’s five and a half years ago now, but I can still remember the feeling of sun on my face, and that it was her presence. We did yoga right before her memorial service as well, in a classroom in her temple, and I’m pretty sure I wore my yoga pants (with a nice shirt) into the sanctuary after. Eventually, Kelly and I started practicing together early in the morning – though not as early as when she’d practiced with Sally, whose power of will and self-discipline were all but boundless. Our new friendship always feels to me like a direct and ongoing gift from Sally herself.

Allison: Being proactive about remembering loved ones drives resilience and sparks happiness. Have you found this to be the case?

Judith: Absolutely. Every year, on the anniversary of her death, I join David and Kelly and another friend, Mary Kay, and we walk through the alleys of our Washington, D.C. neighborhood, which Sally loved to do. She grew up in the house where she later lived with her family, and so she knew the area inside and out. I’m still discovering the alleys, many of which have former victory gardens, now community flower patches. It’s like a parallel, secret world.

Allison: Loss is a great teacher. In what way have you derived greater joy and meaning from life following loss?

Judith: After Sally died, I deeply regretted opportunities for connection that I had missed: invitations to join her group of friends for gardening (I don’t like groups) or to go swim laps (I don’t like indoor pools), or to be a part of her Saturday morning yoga practice. Sally and Kelly did ashtanga yoga. They’d learned it years before, taking class in a nearby studio every morning at 5:30 am. Ashtanga is very hard, and puts a lot of stress on your joints, and I felt I needed to wait, to be stronger, and generally “better,” before I could go practice with them on any kind of regular basis. Also, their group practice conflicted with my own favorite yoga class at the gym. I am struck now by my idiotic short-sightedness. And by that fateful sense that I had to be “good enough” before I was worthy of joining in. The first time I practiced alone with Kelly – a few years after Sally’s death – it felt so great just to be there, in the sunroom-turned-yoga studio in her house, and I thought, I don’t have to be good-enough; it’s enough just to show up. And that idea – that what matters is simply the fact of showing up – was life-changing, because it’s the antidote to perfectionism, and the isolation that so often goes with it. Showing up for others, and showing up to do something good for yourself. I’ve tried and tried since to be better about that. But it’s a “practice,” as they say, like yoga itself.

May 5, 2020

Before Covid-19, General Martin Dempsey Remembers Soldiers Who Died

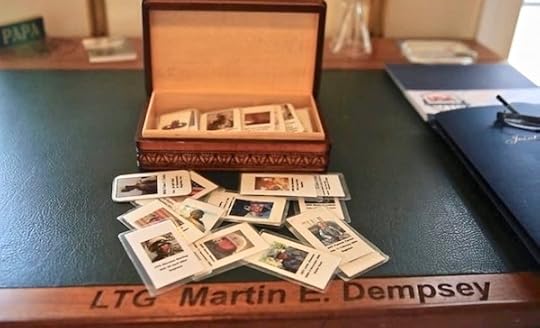

General Martin Dempsey, the 18th Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, keeps a special walnut box on his desk at home. It is full of photographs of soldiers who died under his command in Iraq. General Dempsey says the box is a tangible reminder of each life that was lost, and the pictures push him to always consider what’s really important.

A few years ago, I was honored to meet General Dempsey as part of my work as an Advisory Board member for the Tragedy Assistance Program for Survivors (TAPS). I am grateful he agreed to share his thoughts with me about grief and resilience, especially now as so many of us are coping with loss and needing courage and strength.

General Dempsey’s new book, No Time for Spectators: The Lessons That Mattered Most from West Point to the West Wing, reveals his unique and wholly unexpected perspective on love, life, and loss. Every chapter is a gripping read and I really enjoyed learning about his behind the scenes relationship with President Barack Obama. I tore through his book in just a few days and truly could not put it down. I’m honored to bring you this special Q&A.

Allison: I’d love to learn about the special box on your desk. Can you tell me more?

General Dempsey: Many years ago, a mentor told me that I’d know the military profession was right for me if I “fell in love with my soldiers.” I did. Years later, as a Division Commander in Baghdad in 2003-2004, I had 32,000 soldiers assigned to me. They were a remarkably creative, courageous, and resilient group of young men and women. In the summer of 2003, we began to take casualties. In order to remember them and to honor their memories, I had a small laminated card made for each soldier who was killed. On every card is a photograph of the fallen hero, a description of the circumstances of the soldier’s death, and some information about the family each left behind. I rotate keeping three cards in my wallet at all times, and the remainder I keep in a small wooden box engraved with the words, “Make it Matter.”

Allison: How many cards do you have?

General Dempsey: There are 132 cards in total. At any one time, there are the three cards in my wallet. The other 129 cards are in the box.

Allison: How does having the box affect how you view the future?

General Dempsey: Every day, I try to live up to that phrase, “Make it Matter.” I remind myself that the souls represented by the cards in the box gave up their potential so that the rest of us could achieve ours. We can’t bring them back, but we can make their sacrifices matter in the way we live our lives. I try to “make it matter” for others every day, mostly in small ways but occasionally in big ways. In the aggregate, in any walk of life, we can make what we do matter.

Allison: Being proactive about remembering loved ones drives resilience and sparks happiness. Have you found this to be the case?

General Dempsey: I have. Time has a healing effect on grief, but time shouldn’t diminish our resolve to be better human beings and better leaders. I used to tell young military officers that if you find greater happiness in doing something good for someone else than in any personal accomplishment, then you are the kind of leader we need you to be.

Allison: What do you know now about keeping the memories of these soldiers alive that you didn’t know when the losses occurred?

General Dempsey: Initially, and not surprisingly, when we suffer a loss our first emotion is grief. What I didn’t know was how empowering the memory of the loss could be later . . . if we let it.

Allison: Loss is a great teacher. In what way have you derived greater joy and meaning from life following loss?

General Dempsey: You are absolutely right that loss is a great teacher. What it should teach us is that we have a limited time on earth to make a difference. Therefore, we shouldn’t approach life as though it’s a spectator sport, especially now in these times of great complexity, ubiquitous information, and intense scrutiny. Think of it this way – for the good of all of us, each of us should realize that we have a contribution to make, and we should resolve to get off the sidelines and try to make it – in whatever walk of life and at whatever level of responsibility we find ourselves.

April 5, 2020

When Grief is Overwhelming

These are truly unsettling times. While many of us feel powerless, there is healing power in doing whatever we can to regain a measure of control, no matter how small that step may seem. One strategy is to set aside a few minutes each day (or maybe just a few minutes every week) to grieve and reflect. In my book, Passed and Present: Keeping Memories of Loved Ones Alive, I call this strategy Give Memories 100%. It may include carving out a moment to linger over photographs or re-read old letters, emails, and birthday cards. Devoting uninterrupted time to remembering is healing. It gives emotions their due. We are able to move forward without guilt or reservation because no emotion is given short shrift.

Here are eight stay-at-home projects to consider doing right now. They offer opportunities for a real emotional boost and include links to helpful blog posts that explain each one in detail.

Create a Google Doc for Cherished Recipes. Sharing family recipes can make us happier and feel more connected to those we miss most. Using Google Docs, create a recipe archive and invite relatives to contribute their favorite dishes and desserts. I’ve often written about the empowering nature of cooking on my grief and resilience blog. In two posts, author Benilde Little shares why one particular recipe makes her especially happy and I reveal what I’ve learned from Gwyneth Paltrow’s kitchen.

Get Outside. Use the extra time at home to enjoy the spring weather. I write about the emotional benefits of spending time outside in Passed and Present, and the healing power of gardening is a topic I explore at length in several posts on my blog. For example, I share how gardening boosts memories of loved ones and three ways to use warmer weather as a way to strengthen memories of loved ones.

Get Outside. Use the extra time at home to enjoy the spring weather. I write about the emotional benefits of spending time outside in Passed and Present, and the healing power of gardening is a topic I explore at length in several posts on my blog. For example, I share how gardening boosts memories of loved ones and three ways to use warmer weather as a way to strengthen memories of loved ones.

Start Spring Cleaning. We all know being tidy sparks joy. Just ask authors Marie Kondo and Gretchen Rubin! Yet what we don’t often talk about are the many ways getting rid of clutter can help us heal after loss. I hope you’ll be inspired by these posts about using spring cleaning to increase resilience after loss and five of my favorite ways to remember loved ones.

Start Spring Cleaning. We all know being tidy sparks joy. Just ask authors Marie Kondo and Gretchen Rubin! Yet what we don’t often talk about are the many ways getting rid of clutter can help us heal after loss. I hope you’ll be inspired by these posts about using spring cleaning to increase resilience after loss and five of my favorite ways to remember loved ones.

Upcycling Objects & Heirlooms. Transform t-shirts and jeans into throw pillows and beanbags. Turn fleece jackets and sweatshirts into cozy teddy bears. If you don’t have the skillset to pull these projects off on your own (neither do I!), consider setting aside a few items now and finding a local tailor to help you later. Some popular ideas I’ve written about include ways to upcycle clothing and repurpose unusual fabrics like tablecloths and linen napkins.

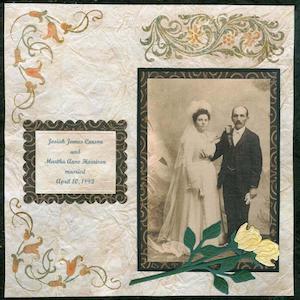

Create a Biographical Scrapbook. A biographical scrapbook is different than a typical scrapbook because it is about another person. To create one, gather snapshots of your loved one. Then locate a few pieces of flat memorabilia that conjure positive memories — ticket stubs, for example, are great for this purpose. Finally, find images online or in magazines that put these objects and photos into historical context. Read more on my blog about biographical scrapbooks and how photographs fuel happiness, plus innovative ways to use photos to remember loved ones.

Put the Social in Social Media. Update your Facebook status with a memory of your loved one and ask friends to share a favorite memory, too. Another meaningful idea is to temporarily swap your profile picture for a photo of your loved one. This small change will give friends a visible cue that you’re open to conversation and support. I share more on my blog about using social media to remember loved ones, including how I gained tremendous joy through social media on the 20th anniversary of losing my mom.

Celebrate Words. We always think we’ll remember our loved one’s funny or poignant sayings. Grab a small notebook and write these special words down. Once they’re on paper, you can get creative in how you preserve them. You can even explore your loved one’s handwriting. All you have to do is locate one of their old letters or postcards and send copies to a handwriting analyst. I’ve written about these possibilities on my blog and introduce you to an expert in New York who can help.

Support Small Businesses. Unemployment numbers are skyrocketing, but many people who own small businesses are still working from home. I am pleased to shine a spotlight on a few of these entrepreneurs like artist Emily McDowell, who makes unique empathy cards, and others who create one-of-a-kind designs from unusual objects like guitar picks and playing cards. Support them, if you can.

Stay safe – and please send me an email with your favorite stay-at-home, memory-boosting activities. Love to hear from you!

March 30, 2020

How New York Changed After the Worst Tragedy Too Few Remember

Thirty years ago, an arson fire at the Happy Land Social Club left 87 people dead. The effects are with us still. Before the fire was out and the smoke had lifted, Ruben Valladares was already in the emergency room with second- and third-degree burns covering half his body. The ambulance call report, handwritten at 3:47 a.m. and updated several times over the next hour, detailed the locations of this injuries. Read the rest at...

The post How New York Changed After the Worst Tragedy Too Few Remember appeared first on Allison Gilbert.

NY Times: How New York Changed After the Worst Tragedy Too Few Remember

Thirty years ago, an arson fire at the Happy Land Social Club left 87 people dead. The effects are with us still.

Thirty years ago, an arson fire at the Happy Land Social Club left 87 people dead. The effects are with us still.

Before the fire was out and the smoke had lifted, Ruben Valladares was already in the emergency room with second- and third-degree burns covering half his body. The ambulance call report, handwritten at 3:47 a.m. and updated several times over the next hour, detailed the locations of this injuries.

View a PDF of the article here

March 10, 2020

New York Times Bestselling Author Peggy Orenstein on Whether Grief Ever Goes Away

Peggy Orenstein is out with her latest book, Boys & Sex, an analysis of young men and their views on relationships, porn, love, and consent. The book is a follow-up to her New York Times best seller Girls & Sex. And because Orenstein is still on tour promoting her book, I was thrilled she agreed to sit down with me to reveal her thoughts about a much different, equally intimate topic: the death of her mother.

During our conversation, Orenstein struck me when she admitted to feeling a special connection to individuals who find themselves in similar positions. “I feel I have an ongoing relationship with people who’ve also suffered the loss of a parent because I’ve survived. Because I didn’t die.” I’m especially grateful to bring you our Q&A.

Allison: Tell me about your mom and your relationship with her. When did she pass away?

Peggy: Mom died four years ago. I think of my mom, miss my mom, and feel like she’s missing things I wish she could see every day. Even if your parent lived a long, healthy life, you still feel that loss.

Allison: What one memento do you have that most reminds you of your mom?

Peggy: I have her jewelry box from when she was 16, her Sweet 16 jewelry box, and I keep mementos in there, and pictures. It’s also where I keep her handwritten recipes and a little ¼ cup tin measuring cup that she used to use for baking. The jewelry box is on the shelf with my sweaters, so when I reach for a sweater, I see it. It’s one of my favorite things.

Allison: Have you ever repurposed an object that belonged to your mother?

Peggy: I’ve been meaning to have some pieces of jewelry my mom left me redesigned so that I would wear them — because her taste was not my taste — but I haven’t done it yet. We had similar taste in color but not otherwise. She was very prone to hearts and butterflies and flowers, but that’s not really who I am. There are stones I want to remove from some of her jewelry so I can turn them into something else. I also wear my maternal grandmother’s engagement ring that barely fits over my knuckles; it’s what I wear in lieu of a wedding ring as a memento of both my mom and grandmother. I have my mom’s wedding rings, as well.

Allison: Have you taken any steps to ensure your daughter maintains a connection to your mom, her grandmother?

Peggy: I just talk about her a lot. I think she feels very close to my mom even though my mother was already pretty old by the time Daisy was born. I did do a lot of really conscious work to take Daisy to see my parents. We went back to Minneapolis a lot when she was littler in order to make sure she had that bond. A lot of memories come through food. For example, just after Chanukah, we made my mom’s potato latkes, and her Chanukah cookies. We also sometimes make her hamantaschen for Purim. My mom also made us a challah cover that we use on Friday nights that I think reminds Daisy of her. It’s almost like there’s nothing in particular we do, but yet I feel like my mom is really integrated into our lives.

Allison: One thing I do with my kids constantly is try to be careful about my language and always talk about my parents as “your grandma” and “your grandpa” instead of orienting the conversation about “my mom” or “my dad.” Do you find yourself doing the same thing?

Peggy: I’ve never thought about that consciously, but yes, I do that, too, and actually I sometimes laugh because I’ll get confused – it’s almost like being bilingual. I always refer to my parents [when talking to Daisy] as “Grandma” and “Grandpa.”

Allison: Loss is a valuable teacher. How has your life shifted because your mother died?

Peggy: My mom died at home, and in the time leading up to her death, in her last week, her family was all around her – all her children, all her grandchildren – we were all there. That period, as hard and intense as it was, was also incredibly meaningful and beautiful and bonding. There was a way she created family and community that was just so clear and well expressed in the time around her death. And that continues to mean so much to me.

February 20, 2020

NY Times: Rejecting the Name My Parents Chose

I was named for the main character in “Little Women.” Changing my name may be the most Jo March-like decision I could have made. Despite the byline you see on this article, the name my parents gave me was Jo. Not Josephine, just Jo. Inspired by the main character in “Little Women,” they dreamed I’d grow to become every bit as norm-bashing as Louisa May Alcott’s fictional character, Jo March….

I was named for the main character in “Little Women.” Changing my name may be the most Jo March-like decision I could have made. Despite the byline you see on this article, the name my parents gave me was Jo. Not Josephine, just Jo. Inspired by the main character in “Little Women,” they dreamed I’d grow to become every bit as norm-bashing as Louisa May Alcott’s fictional character, Jo March….

February 19, 2020

NY Times: Gilding the Gutters

MONTCLAIR – JESSICA de KONINCK knew that when she put her home of nearly 21 years on the market, she would need some help. “If I ever have any free time, the last thing I’d ever want to do is spend it decorating,” Ms. de Koninck admitted.

MONTCLAIR – JESSICA de KONINCK knew that when she put her home of nearly 21 years on the market, she would need some help. “If I ever have any free time, the last thing I’d ever want to do is spend it decorating,” Ms. de Koninck admitted.

Lack of time and interest had indeed taken a toll on her house. Ms. de Koninck had never redecorated while raising her two children, now grown, and her inclinations certainly did not shift after her husband became ill and died three years ago….Continue Reading

February 12, 2020

New York Times Bestselling Author Laurie Halse Anderson Reveals the Lessons Grief Teaches Us

In her memoir, Shout, New York Times bestselling author Laurie Halse Anderson turns away from her career as one of America’s most acclaimed authors of historical fiction and writes about being raped when she was 13. The experience transformed her adolescence and framed her emotional life well into adulthood.

I’ve known Laurie for a while now. We both went to Georgetown University, and since we met, I’ve always been impressed by her wit and generosity. I’m absolutely thrilled she agreed to talk with me about another deeply personal part of her life — the loss of her parents. In our Q&A, Laurie shares the lessons grief has taught her about living life to the fullest.

Allison: What one memento reminds you most of your mother? Your father?

Laurie: When my mother died ten years ago, her granddaughters each took a few items of her clothing. I kept some sweaters and donated the rest to a women’s shelter. I wear them when I’m missing her or coping with challenging situations. We’re getting ready to downsize and I’m pondering which one sweater I’ll take to the new house. It’s time to let the rest of them move on to someone who needs them more than I do.

My father died five years ago. He was a writer (as am I) and we both enjoyed office supply stores to an unhealthy degree. He left me a massive closet filled with envelopes, notepaper and pens. I suspect it will last me at least twenty years. Writing on the paper he gave me helps the words flow freely.

Allison: What is the most satisfying way you’ve developed for keeping the memory of your parents alive?

Laurie: I adore sharing stories about them with my kids and other relatives, especially centered on food. When we enjoy a great bagel topped with cream cheese, red onion, lox, capers and pepper, my father is among us. My mother liked dry martinis and fish chowder (though not at the same time), and she passed on recipes from generations before her, all seasoned with stories of her parents and grandparents.

Allison: Being proactive about remembering loved ones drives resilience and sparks happiness. Have you found this to be the case?

Laurie: Our culture usually teaches us to avoid pain. That avoidance is often at the root of unhealthy behaviors like substance abuse, self-harm, gambling, compulsive shopping and violent outbursts. It’s healthier to confront the pain, to feel deeply and mourn fully. I was a wreck when my parents died and it changed me forever. Now I am this next version of me, matured a bit, with an appreciation of death and understanding of loss. My happiness has deeper roots and very few things upset me.

Allison: What do you know now about keeping the memory of your mother and father alive that you didn’t know when the losses occurred?

Laurie: I took care of both of my parents (and my father-in-law) at the end of their lives and held them as they crossed over. Before their deaths, I simply could not imagine a world without them, though I knew it would exist, at least in theory. Back then the notion that I would be able to function AND focus on the good memories seemed impossible. But then it all unfolded exactly the way it was supposed to.

Allison: Loss is a great teacher. In what way have you derived greater joy and meaning from life following loss?

Laurie: I know this sounds weird, but Death feels like a friendly companion to me, one who gently reminds me every hour to pay attention to this moment, this sip of coffee, this embrace. Caring for my parents and father-in-law and witnessing their deaths was one of the greatest gifts they gave me. Now I know how to live.

January 13, 2020

The BRCA Gene and Losing American Writer Elizabeth Wurtzel

Photo by Neville Elder

Elizabeth Wurtzel was a fearless writer, willing to share stark details of her own clinical depression, drug use, and sex life at an age when most of us are still crafting the narrative of who we are. Even her book titles – Prozac Nation: Young and Depressed in America and Bitch: In Praise of Difficult Women – were forthright and unflinching. Perhaps this is why I am struggling with Wurtzel’s death at the age of 52, from a cause that she could have taken steps to prevent.

Wurtzel and I shared many characteristics: We were Jewish New Yorkers of similar age, both of us writers, and most importantly we each had inherited a genetic mutation called BRCA. According to the CDC, half of women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation will get breast cancer and a third will get ovarian cancer by the time they reach 70. Compare that to women without the mutation: seven out of 100 will get breast cancer and one out of 100 will get ovarian cancer.

My personal response to learning these odds was decisive, even though I was still only in my 30s: I had my ovaries and fallopian tubes removed. In my 40s, I had a preventative double mastectomy. Luckily, I had the gift of knowledge – my mother, aunt and grandmother had all died young of either breast or ovarian cancer. I inherited a map to avoiding their fate.

Wurtzel was not so lucky. She didn’t know of her birth father’s identity – and his family’s medical history with BRCA – until three years ago. Still, she didn’t get tested for BRCA. Her philosophy on life was made clear in an essay she wrote for New York Magazine seven years ago: “I have always made choices without considering the consequences, because I know all I get is now. Maybe I get later, too, but I will deal with that later.”

The idea of living in the moment for the moment was Wurtzel’s greatest gift, her darkest nemesis and, ultimately, her cause of death. Her writing was brilliant because it was unsparing and painfully honest. She didn’t seem to fret over laying every part of herself bare to total strangers. In fact, the original cover of Bitch showed her posing topless while giving the reader the finger.

At various times in her life, she was able to pull herself out of the abyss of addiction and despair and save herself. She went to law school. She put words together that would break your heart. She married, finally. But, in the end, she was not able to save her own life. She didn’t get tested for BRCA, despite the fact that, as an Ashkenazi Jew, she was at greater risk for it. She didn’t have a mastectomy until after she was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer. By then, it was too late.

I’m not sure how much regret Wurtzel had for her big, wonderful mess of a life. But I know that not being tested for BRCA was one. As she wrote in The New York Times after her cancer diagnosis: “I could have had a mastectomy with reconstruction and skipped the part where I got cancer. I feel like the biggest idiot for not doing so . . . I am not sure why anyone with the BRCA mutation would not opt for a prophylactic mastectomy.”

Wurtzel is gone much too soon. She had so much more to experience, to write about, to tell us. She led the way so often, even if it was through pain. We are all diminished by her loss. But she leaves behind a life lesson for all women: Find out whether you have BRCA. If you do, it is not a death sentence, but an opportunity to lead a long, healthy life. Just as Wurtzel did battle against her demons and her addictions, she could have fought hard against BRCA if she had only known.