Elizabeth Rusch's Blog, page 19

October 29, 2013

Advice from an Expert (not me)

I thought I was being so smart. When we decided to dedicate

October to a discussion of the Common Core, a subject I don’t have much to say

about, I grabbed a date at the very end of the month. My plan: see what other

people wrote, and liberally borrow ideas for my own post. But now it’s all been said, and said well, and it seems

unhelpful to repeat. So I’m going in a different direction.

Luckily for me, at a children’s and teen literature conference

earlier this month, I got to see librarian, supervisor of librarians, and all-around

Common Core expert Sue Bartle give a presentation called “The Common Core,

Nonfiction, and You!” Two things she said grabbed my attention. First, and I

quote, “I don’t care about the Common Core. I care about nonfiction.”

Second, she mentioned that she once played Benedict Arnold’s

mother in a school play.

But back to the Common Core. With all the concerns among parents

and educators about how they will be implemented, Sue clearly feels that the

new standards are bringing positive attention to nonfiction. After the talk, she

generously agreed to chat further about how the CC will impact

nonfiction authors.

“I keep hearing it’s going to be great for us,” I said. “Do

you think that’s true?”

“Absolutely” was the short answer. Teachers have lots of concerns

about implementation, she said, especially about the added emphasis on testing.

But the increased attention on nonfiction is a great thing. “Teachers need help

getting kids excited about reading, and that’s where your books come in.”

I asked about how the Common Core might change the way

nonfiction is viewed. She explained that it’s pretty common for librarians to know

fiction better than nonfiction, and to see nonfiction largely as something kids

ask about when they have to write a report. The Common Core can “elevate

nonfiction,” she said, “and get more people talking about it.” She thinks the

CC will be great for those readers, often boys, who naturally prefer

nonfiction, but who are sometimes steered toward “real literature”—that is,

novels. A good book about snakes should count as “real” reading, Sue said.

“So with the librarians you supervise, you’ve seen an

increased interest in nonfiction?”

Yes, she said. “Librarians and teachers often ask, ‘Tell us

books, tell us what’s good.’ Everyone knows about Jim Murphy, how great his

books are.” And they’re hearing more about other great authors—she mentioned

Tanya Lee Stone’s Courage Has No Color

and Sue Macy’s Wheels of Change.

“Great books that can accomplish what Common Core sets out to do.” She’d like

to see publishers promote their nonfiction titles as aggressively as they do

their fiction, and thinks it may happen. “We’ll see.”

Seems like good news, right? But then I got the question I’m

most interested in: “Should writers pay attention to the Common Core?”

“Continue to do what you do,” she said. “Don’t spend time

thinking about Common Core. We look for good stories. If you take the time to

weave in the Common Core, we’re going to see it, and not in a good way.”

“But what if someone writes a good book, and it doesn’t meet

the standards?” I asked. “Isn’t that a danger?”

“A book on almost any subject can meet the Common Core, can

be used in a Common Core way. The key is: can the book be a starting point for

going deeper, for analysis? Can it spark engaged reading and stamina?”

“So writers should know about the Common Core standards,

understand them, but only after

writing should we think about how they relate to what we have done—is that

about right?”

“Yes,” she said, adding, “I beg you never to have the

standards sitting there when you write.”

Sue Bartle is the School Library System Director at E2CC BOCES in western New York. Check out her blog at: http://nonfictionandthecommoncore.blo...

Published on October 29, 2013 09:19

October 28, 2013

Las Vegas, Non-Fiction and the CCSS for Math

I'm just back from Sin City, known to some as Las Vegas. I swear I was sinless. Not a single quarter went from my pocket to the slot. (I've seen the math and I know slot machines are a bad deal -- except for the casino.) I went to Vegas because I gave a talk there at the Western Regional Conference of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, and when I wasn't speaking I was attending sessions. I wanted to see what the math people had to say about the Common Core State Standards.

Most of the media spotlight on the CCSS has focused on tests and the scary prospect of falling test scores under the CCSS. Math educators, on the other hand, talk a lot more about teaching students than what will happen when the students (and the standards) fall victim to the latest round of standardized testing. One plank of the CCSS is the Standards for Mathematical Practice; these are the forms of expertise that teachers at all levels should seek to develop in their students. For example, the first one says, "Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them." Can't argue with that.

The other thing I heard a lot was the word "rigor," which is designated as one of the three key instructional shifts of the CCCSS for Mathematics. (I knew you were wondering: the other two are Focus and Coherence.) And, as it turns out, "rigor" is a controversial word in math circles. Can you figure out why?

The other thing I heard a lot was the word "rigor," which is designated as one of the three key instructional shifts of the CCCSS for Mathematics. (I knew you were wondering: the other two are Focus and Coherence.) And, as it turns out, "rigor" is a controversial word in math circles. Can you figure out why?Well, as with so many things these days, there's the Tea Party crowd and there's the rest of us. To the Tea Party-goers, rigor means "more "(problems), "faster" (answers), "better" (% correct) and "higher "(test scores, of course). To the math educators I heard at NCTM, "rigor" means three elements: "conceptual understanding, procedural skill and fluency, and application with equal intensity," as explained in "Key Instructional Shifts of the Common Core State Standards for Mathematics." A metaphor proffered by one presenter was that of a three-legged stool. Rigor is the stool and the three legs are those three elements, apportioned equally if the stool is going to stay upright and level.

Wow! Conceptual understanding and application equal to skill and fluency? Yep. I've always thought that was the right equation and now the notion is ascendant with the CCSS. I've been thinking about where non-fiction fits in. My first thought, echoed by those I spoke with, was the "application" component. After all, through stories, readers see how math concepts can be applied to the real world. To pick one classic of the "math-lit" genre, Pat Hutchins's The Doorbell Rang comes to mind. Two children are about to enjoy a plate of twelve cookies when the doorbell rings and a guest arrives ... then another ring and two more guests ... then another two... then six more ... then.... (you'll just have to read the book to find out). Each step of the way, to their long-faced chagrin, they must modify their calculation of how many cookies each of them will get. With an enlightened teacher or parent at the helm, the math will be rampant. Here, in delightful literary form, is an application of addition, division, factors, even algebra.

Wow! Conceptual understanding and application equal to skill and fluency? Yep. I've always thought that was the right equation and now the notion is ascendant with the CCSS. I've been thinking about where non-fiction fits in. My first thought, echoed by those I spoke with, was the "application" component. After all, through stories, readers see how math concepts can be applied to the real world. To pick one classic of the "math-lit" genre, Pat Hutchins's The Doorbell Rang comes to mind. Two children are about to enjoy a plate of twelve cookies when the doorbell rings and a guest arrives ... then another ring and two more guests ... then another two... then six more ... then.... (you'll just have to read the book to find out). Each step of the way, to their long-faced chagrin, they must modify their calculation of how many cookies each of them will get. With an enlightened teacher or parent at the helm, the math will be rampant. Here, in delightful literary form, is an application of addition, division, factors, even algebra.

But what about the other two legs of the stool? Can non-fiction add to their support? You've no doubt figured out my answer: of course. Take conceptual understanding. I'll choose a book of my own, If Dogs Were Dinosaurs, which is a companion to the earlier If You Hopped Like a Frog. Both are about proportion, The first compares animal abilities to corresponding abilities of animals; the second looks at relative size (scale) through preposterous examples. "If a submarine sandwich were a real submarine. . . a pickle slice could save your life." The math is explained in the back — and it's easy! See the funny examples, read the back matter, try a few examples of your own (thank you, teachers), and voilà: ratio and proportion make sense. Daunting (and boring) no more. Many have told me so.

But what about the other two legs of the stool? Can non-fiction add to their support? You've no doubt figured out my answer: of course. Take conceptual understanding. I'll choose a book of my own, If Dogs Were Dinosaurs, which is a companion to the earlier If You Hopped Like a Frog. Both are about proportion, The first compares animal abilities to corresponding abilities of animals; the second looks at relative size (scale) through preposterous examples. "If a submarine sandwich were a real submarine. . . a pickle slice could save your life." The math is explained in the back — and it's easy! See the funny examples, read the back matter, try a few examples of your own (thank you, teachers), and voilà: ratio and proportion make sense. Daunting (and boring) no more. Many have told me so.

Computational fluency is a tougher nut for an author to crack and I would say that in most cases it should not be the goal of a non-fiction author unless her paycheck comes from a textbook publisher (in which case, she probably doesn't write on this blog!). But I won't disallow the possibility of "procedural skill and fluency" being a side benefit to a "real" book. Take If You Made a Million, my book for young children about the math of money. Five coin combinations equivalent to a quarter are given (one quarter, two dimes and a nickel, three nickels and a dime, five nickels and 25 pennies). Does that mean there are only five? One second grader explored this question -- and found thirteen. Two students in the same class determined that there are 49 coin combinations that equal fifty cents. ("We were proud of our work because we finally finished it," they wrote.) Think of all the basic skills practice that went into that determination! It didn't feel like drudgery because it wasn't. But the skills were basic just the same.

Computational fluency is a tougher nut for an author to crack and I would say that in most cases it should not be the goal of a non-fiction author unless her paycheck comes from a textbook publisher (in which case, she probably doesn't write on this blog!). But I won't disallow the possibility of "procedural skill and fluency" being a side benefit to a "real" book. Take If You Made a Million, my book for young children about the math of money. Five coin combinations equivalent to a quarter are given (one quarter, two dimes and a nickel, three nickels and a dime, five nickels and 25 pennies). Does that mean there are only five? One second grader explored this question -- and found thirteen. Two students in the same class determined that there are 49 coin combinations that equal fifty cents. ("We were proud of our work because we finally finished it," they wrote.) Think of all the basic skills practice that went into that determination! It didn't feel like drudgery because it wasn't. But the skills were basic just the same.So, as is often the case (especially around this blog!), non-fiction is the answer. By no means is it all that's needed to meet the Common Core math standards, but it sure can help the stool stand up proud, tall and well balanced.

Published on October 28, 2013 23:38

October 25, 2013

Creativity and the Common Core

This month on Interesting Nonfiction for Kids the topic has

been the Common Core Curriculum.The

posts have been varied and informative – an invaluable resource for educators.

Everyone has been talking about the Common Core, from my

eight-grade son’s Language Arts teacher to Arne Duncan to Matt Damon. When I

mentioned to my husband that for this month I had to write something about the

Common Core, he had no clue to what I was talking about, though that term was

thrown to us the entire Back-To-School night.

President Obama said in a July 2009 speech,

“You get to

decide what comes next. You get to choose where change will take us, because

the future does not belong to those who gather armies on a field of battle or

bury missiles in the ground; the future belongs to young people with an

education and the imagination to create. That is the source of power in this

century. And given all that has happened in your two decades on Earth, just

imagine what you can create in the years to come.”

The much-quoted portion of that speech is the line, “the

future belongs to young people with an education and the imagination to create.”

The government through Common Core is trying to address the “young

people with an education” issue, but we seem to be missing half of that

equation – imagination to create.

For your Friday entertainment, I’ll leave you with this

wonderful TED talk by Sir Kenneth Robinson. He says all I would like to write about

creativity, schools and our students, but about 1,000% better. Whether you have already seen this or not,

it’s always aspirational and timely. Our challenge is to now implement

creativity in the classroom.

The ideas of our students are the future.

been the Common Core Curriculum.The

posts have been varied and informative – an invaluable resource for educators.

Everyone has been talking about the Common Core, from my

eight-grade son’s Language Arts teacher to Arne Duncan to Matt Damon. When I

mentioned to my husband that for this month I had to write something about the

Common Core, he had no clue to what I was talking about, though that term was

thrown to us the entire Back-To-School night.

President Obama said in a July 2009 speech,

“You get to

decide what comes next. You get to choose where change will take us, because

the future does not belong to those who gather armies on a field of battle or

bury missiles in the ground; the future belongs to young people with an

education and the imagination to create. That is the source of power in this

century. And given all that has happened in your two decades on Earth, just

imagine what you can create in the years to come.”

The much-quoted portion of that speech is the line, “the

future belongs to young people with an education and the imagination to create.”

The government through Common Core is trying to address the “young

people with an education” issue, but we seem to be missing half of that

equation – imagination to create.

For your Friday entertainment, I’ll leave you with this

wonderful TED talk by Sir Kenneth Robinson. He says all I would like to write about

creativity, schools and our students, but about 1,000% better. Whether you have already seen this or not,

it’s always aspirational and timely. Our challenge is to now implement

creativity in the classroom.

The ideas of our students are the future.

Published on October 25, 2013 07:28

October 24, 2013

The Joy of Exploring Book Structure with the Common Core

Like many fellow INK bloggers, I don’t think about the

Common Core while writing my books. Yet when I read the Common Core anchor reading

standards, I get a sense that they are designed to get kids to explore some of

the things that I DO think about when I write a book. Maybe that is not such a bad thing.

Take, for instance, structure. The reading standards

(especially CCRA.R.5) ask students to think about how a piece

of writing is structured and why the author might have structured it that

way. I think about structure. I obsess

about structure. Considering how to

structure a book is the most fun, the most creative, and perhaps the most

important part of my writing process.

Structure is a the-world-is-your-oyster kind of thing. The options for structuring a piece of writing

to inspire, entertain, and inform are endless. I can be creative, literary,

artistic, poetic, humorous, vivid, and suspenseful. I can use metaphor,

imagery, narrative arc, voice, or any other tool I’d like. When I write, I’m

like a curator at a museum. I get to decide what to focus on and how to present

it. So half the fun is figuring out: What is the best way to tell this story?

What interesting or clever structure will make this amazing material come to

life for readers?

Let me give you an example. Since the release of two new

books this year, I now have three books for young readers on volcanoes. Each

has a completely different structure.

VOLCANO RISING, a picture book for young kids, age five to

VOLCANO RISING, a picture book for young kids, age five to

nine, focuses on the creative force of volcanoes, how volcanoes shape the

landscape, building mountains and creating islands where there were none

before. The book is organized around an idea: creative eruptions. I introduce

the concept, explain it, and then give eight vivid examples. The book also has

two layers of text. In the first, I employ lyrical language so that it’s lovely

to read aloud. The second layer offers more detailed descriptions of

fascinating creative eruptions for parents or teachers to share with kids or

for independent readers to explore on their own.

WILL IT BLOW? is designed to be a fun, interactive way for

kids age six to ten to understand and use cutting-edge volcano monitoring by

drawing a playful parallel between volcano monitoring and

detective work. The book introduces Mount St. Helens as the

suspect, and the chapters describe

clues that volcanologists gather. Each chapter ends with a

real case study from Mount St. Helens’ 2004-2008 eruption where kids apply what

they learned about clues to guess what Mount St. Helens might do next. WILL IT

BLOW? offers pretty hefty scientific material presented through the lens of

detective work.

ERUPTION! VOLCANOES AND THE SCIENCE OF SAVING LIVES is for

older readers, kids age ten and up. It’s a no-holds-barred immersion into the

destructive power of volcanoes and the intense challenge of predicting deadly

violent eruptions. I follow a small team of scientists as they work on the

flanks of steaming, quaking, ash-spewing volcanoes all over the world—from

Colombia and the Philippines to Chile and Indonesia—as they struggle to predict

eruptions and prevent tragedies. I chose some historical eruptions and some current ones to show how the scientists' work has evolved over time, and tried to weave together the scientific process with suspenseful, nail-biting material to pull readers through.

One topic, volcanoes, with three very different

structures. What does this mean for what

might happen in the classroom with my volcano books? Teachers could have

students look at all three of these books and describe their structures and

what they accomplish. To explore the

structure of VOLCANO RISING, a teacher could ask: Why did the author chose the

eight volcanoes that she features in this book? What is the purpose of the two

different layers of text? How do the layers affect how the book might be used? To delve deeper into the structure of WILL IT

BLOW? a teacher could ask: How is the theme of volcanology-as-detective-work

reflected in the structure of the book? How does the opening chapter set the

stage for the rest of the book? What is the common structure found in each

chapter and what does that structure accomplish? For ERUPTION, students could

explore: Why does the author tell the stories of several eruptions? Why those

eruptions? What does each add?

Why stop with my volcano books? Students could check out three

more volcano books and describe how they are the same and different. Teachers

could even ask students to brainstorm ideas for three more ways one could structure a book about volcanoes. To me,

structure is about both creativity and synthesizing information, so exploring

structure can offer both hard-core analysis and a creative outlet.

I’m a little obsessed with structure, so teachers and

students probably have lots to talk about by picking apart the structures of my

books. My nonfiction picturebook

biography THE PLANET HUNTER: THE STORY BEHIND WHAT HAPPENED TO PLUTO explains

why Pluto is not considered a planet anymore by telling the true story of the

astronomer behind it. I use the structure of a narrative arc, which is commonly

used in fiction, with a character (astronomer Mike Brown) who wants something

(to find more planets in our solar system), rising tension, a climax and a

resolution. Teachers can explore narrative arc structure with students by

having them find these parts in the story.

In my nonfiction picture book biography of Maria Anna Mozart

–Wolfgang Mozart’s older sister who was also a child prodigy – I used the

structure of a piano sonata, the type of music Maria Anna played most often, as

the structure for the book. So in FOR THE LOVE OF MUSIC, I divided her story

into movements and employed other other musical notations to highlight events

in Maria Anna’s life. The Mozart

children’s whirlwind musical tour of Europe is in a section called Allegro (the

fast tempo of the first movement of a piano sonata). When Wolfgang climbs into

a carriage headed for Italy, leaving his sister behind, the section is Coda (an

ending.) In a section titled Fermata (in which everything stops), Maria Anna's

piano warps in the frigid weather, and in Cadenza (a passage for a soloist to

improvise), Maria Anna weeps for Wolfgang, who dies so young. Classroom discussions about this structure could address: How

does the sonata structure shape the book? What constraints did using this

structure put on the author? What did the structure add?

Basically, I think the standards open the door to asking

readers to notice a book’s structure, to think about why a book is structured

the way it is, to imagine how it could have been structured differently and to

consider a variety of ways to structure their writing, too.

What might this look like in the classroom more generally? Talk about books

with interesting structures. Find books on the same topic or subject matter

with different structures and discuss how the structures differ and how that

affects the book.

To develop writing skills, kids could brainstorm at least

three different possible structures for a piece of writing. (I do this before

writing my books, though I don’t limit myself to only three.) Student could write

about the same topic more than once, employing very different structures. (I often

write multiple drafts of different parts of my books, testing out different

structures.)

Encouraging students to consider creative ways to structure

a piece of writing can give kids a way to really engage with the material and

make it their own. To me any topic becomes more interesting if I ask

myself: How could I structure this to be the most interesting and most

effective? If teachers encourage kids to

think creatively about structuring their writing, students may engage more

deeply with the material and, ultimately, write pieces that are more

interesting to read.

Elizabeth Rusch

P.S. While my books offer good opportunities to discuss structure,

I think they can also spur discussions around other elements of the Common

Core, such as theme (R.2), word choice (R.4), and point of view (R.6). To

give teachers ideas on how to use my books to support Common Core learning, I

have created a short, half-page Common Core Bookmark for each of my books based on the reading anchor standards.

Click on a title to get the short guide:

Electrical Wizard: How Nikola Tesla Lit Up the World

Eruption! Volcanoes and the Science of Saving Lives

For the Love of Music: The Remarkable Story of Maria Anna Mozart

Generation Fix: Young Ideas for a Better World

The Mighty Mars Rovers: The incredible adventures of Spirit and Opportunity

The Planet Hunter: The Story Behind What Happened to Pluto

Volcano Rising

Will It Blow? Become a Volcano Detective at Mount St. Helens

If you happen like the format I created to distill my Common

Core-related ideas about my books into a half-page bookmark, please feel free

to use this blank version.

Common Core while writing my books. Yet when I read the Common Core anchor reading

standards, I get a sense that they are designed to get kids to explore some of

the things that I DO think about when I write a book. Maybe that is not such a bad thing.

Take, for instance, structure. The reading standards

(especially CCRA.R.5) ask students to think about how a piece

of writing is structured and why the author might have structured it that

way. I think about structure. I obsess

about structure. Considering how to

structure a book is the most fun, the most creative, and perhaps the most

important part of my writing process.

Structure is a the-world-is-your-oyster kind of thing. The options for structuring a piece of writing

to inspire, entertain, and inform are endless. I can be creative, literary,

artistic, poetic, humorous, vivid, and suspenseful. I can use metaphor,

imagery, narrative arc, voice, or any other tool I’d like. When I write, I’m

like a curator at a museum. I get to decide what to focus on and how to present

it. So half the fun is figuring out: What is the best way to tell this story?

What interesting or clever structure will make this amazing material come to

life for readers?

Let me give you an example. Since the release of two new

books this year, I now have three books for young readers on volcanoes. Each

has a completely different structure.

VOLCANO RISING, a picture book for young kids, age five to

VOLCANO RISING, a picture book for young kids, age five tonine, focuses on the creative force of volcanoes, how volcanoes shape the

landscape, building mountains and creating islands where there were none

before. The book is organized around an idea: creative eruptions. I introduce

the concept, explain it, and then give eight vivid examples. The book also has

two layers of text. In the first, I employ lyrical language so that it’s lovely

to read aloud. The second layer offers more detailed descriptions of

fascinating creative eruptions for parents or teachers to share with kids or

for independent readers to explore on their own.

WILL IT BLOW? is designed to be a fun, interactive way for

kids age six to ten to understand and use cutting-edge volcano monitoring by

drawing a playful parallel between volcano monitoring and

detective work. The book introduces Mount St. Helens as the

suspect, and the chapters describe

clues that volcanologists gather. Each chapter ends with a

real case study from Mount St. Helens’ 2004-2008 eruption where kids apply what

they learned about clues to guess what Mount St. Helens might do next. WILL IT

BLOW? offers pretty hefty scientific material presented through the lens of

detective work.

ERUPTION! VOLCANOES AND THE SCIENCE OF SAVING LIVES is for

older readers, kids age ten and up. It’s a no-holds-barred immersion into the

destructive power of volcanoes and the intense challenge of predicting deadly

violent eruptions. I follow a small team of scientists as they work on the

flanks of steaming, quaking, ash-spewing volcanoes all over the world—from

Colombia and the Philippines to Chile and Indonesia—as they struggle to predict

eruptions and prevent tragedies. I chose some historical eruptions and some current ones to show how the scientists' work has evolved over time, and tried to weave together the scientific process with suspenseful, nail-biting material to pull readers through.

One topic, volcanoes, with three very different

structures. What does this mean for what

might happen in the classroom with my volcano books? Teachers could have

students look at all three of these books and describe their structures and

what they accomplish. To explore the

structure of VOLCANO RISING, a teacher could ask: Why did the author chose the

eight volcanoes that she features in this book? What is the purpose of the two

different layers of text? How do the layers affect how the book might be used? To delve deeper into the structure of WILL IT

BLOW? a teacher could ask: How is the theme of volcanology-as-detective-work

reflected in the structure of the book? How does the opening chapter set the

stage for the rest of the book? What is the common structure found in each

chapter and what does that structure accomplish? For ERUPTION, students could

explore: Why does the author tell the stories of several eruptions? Why those

eruptions? What does each add?

Why stop with my volcano books? Students could check out three

more volcano books and describe how they are the same and different. Teachers

could even ask students to brainstorm ideas for three more ways one could structure a book about volcanoes. To me,

structure is about both creativity and synthesizing information, so exploring

structure can offer both hard-core analysis and a creative outlet.

I’m a little obsessed with structure, so teachers and

students probably have lots to talk about by picking apart the structures of my

books. My nonfiction picturebook

biography THE PLANET HUNTER: THE STORY BEHIND WHAT HAPPENED TO PLUTO explains

why Pluto is not considered a planet anymore by telling the true story of the

astronomer behind it. I use the structure of a narrative arc, which is commonly

used in fiction, with a character (astronomer Mike Brown) who wants something

(to find more planets in our solar system), rising tension, a climax and a

resolution. Teachers can explore narrative arc structure with students by

having them find these parts in the story.

In my nonfiction picture book biography of Maria Anna Mozart

–Wolfgang Mozart’s older sister who was also a child prodigy – I used the

structure of a piano sonata, the type of music Maria Anna played most often, as

the structure for the book. So in FOR THE LOVE OF MUSIC, I divided her story

into movements and employed other other musical notations to highlight events

in Maria Anna’s life. The Mozart

children’s whirlwind musical tour of Europe is in a section called Allegro (the

fast tempo of the first movement of a piano sonata). When Wolfgang climbs into

a carriage headed for Italy, leaving his sister behind, the section is Coda (an

ending.) In a section titled Fermata (in which everything stops), Maria Anna's

piano warps in the frigid weather, and in Cadenza (a passage for a soloist to

improvise), Maria Anna weeps for Wolfgang, who dies so young. Classroom discussions about this structure could address: How

does the sonata structure shape the book? What constraints did using this

structure put on the author? What did the structure add?

Basically, I think the standards open the door to asking

readers to notice a book’s structure, to think about why a book is structured

the way it is, to imagine how it could have been structured differently and to

consider a variety of ways to structure their writing, too.

What might this look like in the classroom more generally? Talk about books

with interesting structures. Find books on the same topic or subject matter

with different structures and discuss how the structures differ and how that

affects the book.

To develop writing skills, kids could brainstorm at least

three different possible structures for a piece of writing. (I do this before

writing my books, though I don’t limit myself to only three.) Student could write

about the same topic more than once, employing very different structures. (I often

write multiple drafts of different parts of my books, testing out different

structures.)

Encouraging students to consider creative ways to structure

a piece of writing can give kids a way to really engage with the material and

make it their own. To me any topic becomes more interesting if I ask

myself: How could I structure this to be the most interesting and most

effective? If teachers encourage kids to

think creatively about structuring their writing, students may engage more

deeply with the material and, ultimately, write pieces that are more

interesting to read.

Elizabeth Rusch

P.S. While my books offer good opportunities to discuss structure,

I think they can also spur discussions around other elements of the Common

Core, such as theme (R.2), word choice (R.4), and point of view (R.6). To

give teachers ideas on how to use my books to support Common Core learning, I

have created a short, half-page Common Core Bookmark for each of my books based on the reading anchor standards.

Click on a title to get the short guide:

Electrical Wizard: How Nikola Tesla Lit Up the World

Eruption! Volcanoes and the Science of Saving Lives

For the Love of Music: The Remarkable Story of Maria Anna Mozart

Generation Fix: Young Ideas for a Better World

The Mighty Mars Rovers: The incredible adventures of Spirit and Opportunity

The Planet Hunter: The Story Behind What Happened to Pluto

Volcano Rising

Will It Blow? Become a Volcano Detective at Mount St. Helens

If you happen like the format I created to distill my Common

Core-related ideas about my books into a half-page bookmark, please feel free

to use this blank version.

Published on October 24, 2013 04:00

October 22, 2013

What Publishers Are Doing

I’ve never studied educational theory, and only visit schools as

“queen/author for a day.” So I was rather nonplussed when we agreed to write

about Common Core Standards this month. I figured other bloggers would say lots

of great things before my late-in-the-month turn – and I could copy off their

paper. Well, they’ve did, and I

really don’t have anything to add.

Except that

Cheryl Harness’s “shame-faced cinders” (in her recent post) reminded me of the cinders still lurking in my hiking boots from

my recent tortuous climb up Stromboli…..

….and Mount Etna.

Then Caroline Arnold, a good friend and good writer (like

Charlotte), described a recent talk she gave on the subject wherein she

discussed what her publishers are doing about the standards. So I’m

copying off her paper instead. Here are what a few of my editors say about Common Core

Standards and nonfiction books.

Lerner and Carolrhoda Books

Editor Andrew Karre’s responses were swift, short, and sweet.

1. Have the Common Core Standards

brought any change to the number or type of books you are acquiring?

Yes, to a certain extent.

2. Are you making any changes to the back matter to relate more

directly to the standards?

Not many. Our back matter was already pretty robust. In

that case CC confirmed our approach.

3. Have you changed your marketing strategy to accommodate the

standards?

Yes, definitely.

4. Any other comments about the standards and what they might mean to

your list?

I think it means great things for creative, thoughtful,

author-led nonfiction—which is to say I’ll be able to continue doing it and

maybe do more of it. I think it’s a huge boon for poets.

Katie

O’Neel, publicist at Lerner and Carolrhoda, elaborated.

We have started to include the Common Core correlations of each

title in our catalog front list. We have also created Common Core libraries,

which provide curated bundles of books, in library-bound or multi-user ebook

formats, that have particularly strong correlations to the Common Core. We have

also created hundreds of Common Core teaching guides that are available for

free download on our website.

It’s all very user-friendly at https://www.lernerbooks.com/pages/common-Core.aspx

Holiday House

Editor Julie Amper weighed in.

“Holiday House has always published books with the school

curriculum in mind. New we are adding

information on how the book fits the Standards and how it could be used. In both our catalog and on our website we have annotated how books

fit the Standards and how they might be used.

We do not see the Common Core Standards as a departure from what

good teachers having been doing for a long time. The Standards aren’t teaching

new or different information, but are rather a checklist of skills teachers

have worked on with their students for years. We see great opportunities

for creative teaching by adoption of the Common Core Standards and use of trade

books and other materials in the classroom.”

The Holiday

House website’s home page has a link to Common Core State Standards which links

to Teaching Ideas, Titles by Subject, and teachers’ materials. www.holidayhouse.com

Boyds Mills/Calkins Creek

Boyds Mills

Press, with their well-respected Calkins Creek American history imprint, and

Word Song, a poetry imprint, are poised to take advantage of Common Core

Standards. Kerry McManus, publicist for Boyds Mills and Calkins Creek, reports

that the spring 2014 catalog will link the new titles to various standards, and

Educators’ Guides will do the same.

Chicago Review Press

With a large

back and front list of middle grade activity books do draw on, Mary Kravenas, Marketing Manager, writes,

“There hasn’t been a huge

sea change in how we look at acquiring books. If anything, the CC standards

have confirmed what we had already established with our list -- the strength

and importance of non-fiction books for K-12 students. We do look a little

deeper now when we’re positioning a title, discussing what standards a title

addresses, and it reaffirms our commitment to quality non-fiction.”

So teachers and writers, just....

Published on October 22, 2013 21:30

It's a challenge to meet Common Core State Standards!

So, you're using the Common Core State Standards and you want books that align* with the standards, right? Let's try a little challenge...I'm going to see how many standards can be partly or completely fulfilled with one of my books.

*Is it just me, or does the use of the word align, often used in this context, sound a little funny? As if a chiropractor was involved, perhaps.

My new fall book, Jack & the Hungry Giant , starts out the same way as the traditional fairy tale. There are magic beans, a beanstalk, and a boy that climbs into the sky. It isn't long before Jack is discovered inside the huge castle. The fearsome giant announces, "I'm hungry!" so Jack takes a flying leap to escape. The giant manages to grab him by the shoelace, warns him to be more careful, and asks, "Are you hungry, too?" It turns out that Waldorf is a friendly giant and an excellent chef. The rest of the book revolves around turning veggies, fruit, grains, and the rest of the MyPlate food groups into a healthy meal, then dishing up a plateful. For more info and images from the book, see this post on my blog.

••• By the way, until October 31 the publisher is sponsoring a giveaway of several copies on Goodreads. I'm hoping that a couple of I.N.K. readers will win a copy! •••

To compare the old with the new, pick out a traditional version of Jack and the Beanstalk to contrast with Jack & the Hungry Giant for the following *Common Core standards:

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.1.9 Compare and contrast the adventures and experiences of characters in stories.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.2.9

Compare and contrast two or more versions of the same story (e.g.,

Cinderella stories) by different authors or from different cultures.

Or choose an informational book or other text about MyPlate to compare with Jack.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.2.9 Compare and contrast the most important points presented by two texts on the same topic.

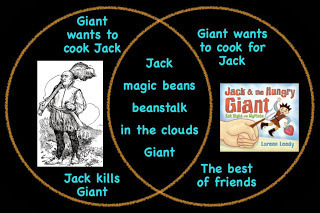

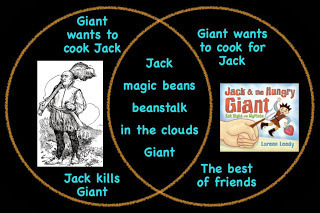

A Venn diagram can work well for this kind of comparison. (Hmmm, guess we can't claim any math standards, can we?) The image below could be a model for an anchor chart:

The picture of the giant on the left is from ClipArt Etc., a source of free, mostly antique images for educational use.

I've made this freebie book activity to use with Jack that's available on this page in my TeachersPayTeachers shop. Kids will make lists of foods, so that can count as the "answer questions" part of:

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.1.1 Ask and answer questions about key details in a text.

Also included is a MyPlate printable for kids to draw and label food items in the various groups: Vegetables, Fruits, Grains, Protein Foods, Dairy. In addition, it would be easy to do some vocabulary word work using the food groups and names of the individual goodies:

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.2.4 Determine the meaning of words and phrases in a text relevant to a grade 2 topic or subject area.

For example, students can make an individual or class picture dictionary of words and definitions to fulfill that standard.

So, that adds up to 5 standards for Jack & the Hungry Giant. Not bad for one book. But wait...I hate to leave out math standards entirely....

Let's use the illustrations to do some counting: how many grapes are visible on the Fruit pages? How many raspberries? How many peas does Jack put on his plate? Draw a picture of Jack with 10 blueberries in a circle around him; draw a straight line of peanuts across the page then count how many.

CCSS.Math.Content.K.CC.B.5

Count to answer “how many?” questions about as many as 20 things

arranged in a line, a rectangular array, or a circle, or as many as 10

things in a scattered configuration; given a number from 1–20, count out

that many objects.

Students could do a survey about the food preferences of their classmates in each food group. Would you rather eat broccoli, green beans, or asparagus? Then they'll make a graph to display the results.

CCSS.Math.Content.1.MD.C.4

Organize, represent, and interpret data with up to three categories;

ask and answer questions about the total number of data points, how many

in each category, and how many more or less are in one category than in

another.

Kids can measure items in the book such as the corn on the cob on the Vegetables page or the banana on the Fruits page.

CCSS.Math.Content.2.MD.A.1

Measure the length of an object by selecting and using appropriate

tools such as rulers, yardsticks, meter sticks, and measuring tapes.

Okay, now we're up to 8 standards! I hope most of these suggestions are more or less reasonable and will inspire ideas about how an informational picture book can be used to meet Common Core standards.

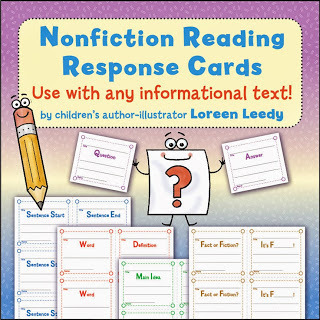

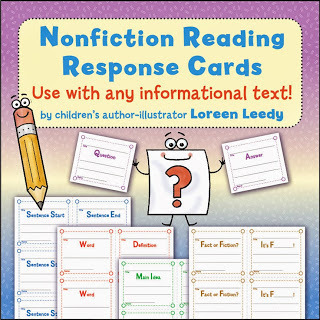

One more thing...would anyone be interested in a resource that can be used with any informational text?

These printable Nonfiction Reading Response Cards have only been in my TpT shop for a few weeks but have been downloaded over 1,000 times already, so there must be a need for this kind of template. Students fill out the cards based on a book they're reading. The cards come in pairs as shown on the cover image above: Sentence Start and End; Question and Answer, Word and Definition; Main Ideas and Details; and Fact or Fiction? Teachers can utilize some or all of the cards depending on the circumstances and try one of the game ideas to turn reading into an engaging group experience. Note: this resource will be free until the end of October. What standards can these cards help to meet?

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.3.1 Ask and answer questions to demonstrate understanding of a text, referring explicitly to the text as the basis for the answers. [e.g. include page numbers]

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.3.2 Determine the main idea of a text; recount the key details and explain how they support the main idea.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.3.4 Determine the meaning of general academic and domain-specific words and phrases in a text relevant to a grade 3 topic or subject area.

These are all for 3rd grade but there are similar standards in other grades.

Whew...this turned out to be a long post...hope it has been helpful!

Loreen

My web site

*The Common Core Standards are © Copyright 2010. National Governors Association Center for Best

Practices and Council of Chief State School Officers. All rights

reserved.

*Is it just me, or does the use of the word align, often used in this context, sound a little funny? As if a chiropractor was involved, perhaps.

My new fall book, Jack & the Hungry Giant , starts out the same way as the traditional fairy tale. There are magic beans, a beanstalk, and a boy that climbs into the sky. It isn't long before Jack is discovered inside the huge castle. The fearsome giant announces, "I'm hungry!" so Jack takes a flying leap to escape. The giant manages to grab him by the shoelace, warns him to be more careful, and asks, "Are you hungry, too?" It turns out that Waldorf is a friendly giant and an excellent chef. The rest of the book revolves around turning veggies, fruit, grains, and the rest of the MyPlate food groups into a healthy meal, then dishing up a plateful. For more info and images from the book, see this post on my blog.

••• By the way, until October 31 the publisher is sponsoring a giveaway of several copies on Goodreads. I'm hoping that a couple of I.N.K. readers will win a copy! •••

To compare the old with the new, pick out a traditional version of Jack and the Beanstalk to contrast with Jack & the Hungry Giant for the following *Common Core standards:

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.1.9 Compare and contrast the adventures and experiences of characters in stories.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.2.9

Compare and contrast two or more versions of the same story (e.g.,

Cinderella stories) by different authors or from different cultures.

Or choose an informational book or other text about MyPlate to compare with Jack.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.2.9 Compare and contrast the most important points presented by two texts on the same topic.

A Venn diagram can work well for this kind of comparison. (Hmmm, guess we can't claim any math standards, can we?) The image below could be a model for an anchor chart:

The picture of the giant on the left is from ClipArt Etc., a source of free, mostly antique images for educational use.

I've made this freebie book activity to use with Jack that's available on this page in my TeachersPayTeachers shop. Kids will make lists of foods, so that can count as the "answer questions" part of:

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.1.1 Ask and answer questions about key details in a text.

Also included is a MyPlate printable for kids to draw and label food items in the various groups: Vegetables, Fruits, Grains, Protein Foods, Dairy. In addition, it would be easy to do some vocabulary word work using the food groups and names of the individual goodies:

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.2.4 Determine the meaning of words and phrases in a text relevant to a grade 2 topic or subject area.

For example, students can make an individual or class picture dictionary of words and definitions to fulfill that standard.

So, that adds up to 5 standards for Jack & the Hungry Giant. Not bad for one book. But wait...I hate to leave out math standards entirely....

Let's use the illustrations to do some counting: how many grapes are visible on the Fruit pages? How many raspberries? How many peas does Jack put on his plate? Draw a picture of Jack with 10 blueberries in a circle around him; draw a straight line of peanuts across the page then count how many.

CCSS.Math.Content.K.CC.B.5

Count to answer “how many?” questions about as many as 20 things

arranged in a line, a rectangular array, or a circle, or as many as 10

things in a scattered configuration; given a number from 1–20, count out

that many objects.

Students could do a survey about the food preferences of their classmates in each food group. Would you rather eat broccoli, green beans, or asparagus? Then they'll make a graph to display the results.

CCSS.Math.Content.1.MD.C.4

Organize, represent, and interpret data with up to three categories;

ask and answer questions about the total number of data points, how many

in each category, and how many more or less are in one category than in

another.

Kids can measure items in the book such as the corn on the cob on the Vegetables page or the banana on the Fruits page.

CCSS.Math.Content.2.MD.A.1

Measure the length of an object by selecting and using appropriate

tools such as rulers, yardsticks, meter sticks, and measuring tapes.

Okay, now we're up to 8 standards! I hope most of these suggestions are more or less reasonable and will inspire ideas about how an informational picture book can be used to meet Common Core standards.

One more thing...would anyone be interested in a resource that can be used with any informational text?

These printable Nonfiction Reading Response Cards have only been in my TpT shop for a few weeks but have been downloaded over 1,000 times already, so there must be a need for this kind of template. Students fill out the cards based on a book they're reading. The cards come in pairs as shown on the cover image above: Sentence Start and End; Question and Answer, Word and Definition; Main Ideas and Details; and Fact or Fiction? Teachers can utilize some or all of the cards depending on the circumstances and try one of the game ideas to turn reading into an engaging group experience. Note: this resource will be free until the end of October. What standards can these cards help to meet?

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.3.1 Ask and answer questions to demonstrate understanding of a text, referring explicitly to the text as the basis for the answers. [e.g. include page numbers]

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.3.2 Determine the main idea of a text; recount the key details and explain how they support the main idea.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.3.4 Determine the meaning of general academic and domain-specific words and phrases in a text relevant to a grade 3 topic or subject area.

These are all for 3rd grade but there are similar standards in other grades.

Whew...this turned out to be a long post...hope it has been helpful!

Loreen

My web site

*The Common Core Standards are © Copyright 2010. National Governors Association Center for Best

Practices and Council of Chief State School Officers. All rights

reserved.

Published on October 22, 2013 00:00

October 21, 2013

What Others Have Said Re: Geo. C. + the CCSS Goes For Me 2

"Someone is always taking the joy out of life. For 20 years I proceed blissfully writing stories to keep the wolf from my door and to cause other people to forget for an hour or two the wolves at their doors and up pops [an] editor... and asks me for an article on the Tarzan theme."

Edgar Rice Burroughs

It's nearly 10 o'clock on the night before the morning upon which (I just realized) my October post is due to appear. A bit frayed and shopworn I am, having spent the last ten hours fussing with a perfectly speculative, i.e. crapshoot [May I say that?] nonfiction manuscript about a completely compelling (to me) subject, time, and place, none of which I shall divulge for fear of the Jinx. And, as I switch gears, wind up for the pitch, and otherwise warm to the subject at hand I confess that, though I was heartened by Deborah Heiligman's thoughtful and diverting consideration of George Clooney, I chew the lower lip a bit [Can one do that whilst biting the proverbial bullet?] at having had to set aside my obsession du jour to write about the Common Core.

As Tanya Lee Stone pointed out, "standards committees can suck the creativity out of learning." And that great teachers and librarians have been clever prospectors for years, mining the treasures to be found in nonfiction literature. Me, I was reminded of a weary young teacher I met at conference in Texas years ago, at which the subject was testing: "Must they suck every last drop of joy out of the classroom?" Having crashed and burned into shamefaced cinders as a student teacher some four decades ago, my wholehearted admiration is for the creative Classroom Captains. Had I a hat on, I would reverently take it off to them. I eventually found my way to writing and illustrating historical subjects: a joyous business. But I never gave one thought to curricular standards. As Jim Murphy quoted that which Steve Sheinkin noted re: Barbara Kerley's excellent and clarifying post, "I still hate the idea of thinking about standards." But now it's – o.m.g. – nearly 11 o'clock. How did that old quill-scratcher, William Shakespeare put it? By way of Macbeth , Act I Scene 7? Ah: "If it were done when 'tis done, then 'twere well it were done quickly." Amen to THAT.

As nearly all of my fellow Inksters/bloggers have pointed out, far better than I, we read, write, research, rewrite, and read still more about stories, events, individuals that command our wonderings, our curious attentions. That tempt us to go gallivanting to a museum or some distant library where more answers may await us. So launch an obsession that we find ourselves hunched over a keyboard all day, fussing with just the right way to tell about it all, so the words sing, so the facts are solid and the story rings true. Frustrated if you have to set it aside even for an hour, just because there's a blogpost to write or some four-legger needs to go outside.

"Yes, I know you're busy doing what-

ever it is you do, and it's the middle

of the night, but how 'bout a walk?"

Busting to tell about it in such a way that editors will pay us some money, That young readers we may never meet will get why it was/is so cool or such a big deal. Or how it all lead to the way things are now. How it works. Or how it looked and felt at that particular time, at that particular place, with that set of individuals. What was it like. Why it happened in just that way. If you do all of that as you've learned to do, as your imagination and education has directed, as you pray you can still do, as your subject merits and your readers deserve, then your words cannot help but satisfy a worthy roster of curriculum standards. They'll be worth the precious time of some hardworking teacher, who can wrap his or her head around the eye-crossing language of committee-driven directives while juggling the endless needs of his or her paperwork-generating principal, school board, conflicted, tax-strapped, seed-corn-eating government; as well as his or her delightful/tender/cruel/bored/precious students and their parents plus all of their bumptious universe of challenges at their separate-but-manifestly-unequal homes..

And so we beat on, ignoring the Sirens on the Rocks, whispering about books we'd like to read. The new autumn movies in the theaters. Or those most seductive things: projects one should not be doing. Planting bulbs. Plotting a murder mystery (mine usually involves a dead art director, but I digress) for Nanowrimo coming up. Listing what you'll pack in the camper of one's pickup truck, a la John Steinbeck before heading out to see.... But no: We nonfiction types, we creative cogs in the great literary-education complex have a lot of explaining to do. The standards are high, but the yoke is easy and the burden is light.

Depending on what day you ask, anyway.

Edgar Rice Burroughs

It's nearly 10 o'clock on the night before the morning upon which (I just realized) my October post is due to appear. A bit frayed and shopworn I am, having spent the last ten hours fussing with a perfectly speculative, i.e. crapshoot [May I say that?] nonfiction manuscript about a completely compelling (to me) subject, time, and place, none of which I shall divulge for fear of the Jinx. And, as I switch gears, wind up for the pitch, and otherwise warm to the subject at hand I confess that, though I was heartened by Deborah Heiligman's thoughtful and diverting consideration of George Clooney, I chew the lower lip a bit [Can one do that whilst biting the proverbial bullet?] at having had to set aside my obsession du jour to write about the Common Core.

As Tanya Lee Stone pointed out, "standards committees can suck the creativity out of learning." And that great teachers and librarians have been clever prospectors for years, mining the treasures to be found in nonfiction literature. Me, I was reminded of a weary young teacher I met at conference in Texas years ago, at which the subject was testing: "Must they suck every last drop of joy out of the classroom?" Having crashed and burned into shamefaced cinders as a student teacher some four decades ago, my wholehearted admiration is for the creative Classroom Captains. Had I a hat on, I would reverently take it off to them. I eventually found my way to writing and illustrating historical subjects: a joyous business. But I never gave one thought to curricular standards. As Jim Murphy quoted that which Steve Sheinkin noted re: Barbara Kerley's excellent and clarifying post, "I still hate the idea of thinking about standards." But now it's – o.m.g. – nearly 11 o'clock. How did that old quill-scratcher, William Shakespeare put it? By way of Macbeth , Act I Scene 7? Ah: "If it were done when 'tis done, then 'twere well it were done quickly." Amen to THAT.

As nearly all of my fellow Inksters/bloggers have pointed out, far better than I, we read, write, research, rewrite, and read still more about stories, events, individuals that command our wonderings, our curious attentions. That tempt us to go gallivanting to a museum or some distant library where more answers may await us. So launch an obsession that we find ourselves hunched over a keyboard all day, fussing with just the right way to tell about it all, so the words sing, so the facts are solid and the story rings true. Frustrated if you have to set it aside even for an hour, just because there's a blogpost to write or some four-legger needs to go outside.

"Yes, I know you're busy doing what-

ever it is you do, and it's the middle

of the night, but how 'bout a walk?"

Busting to tell about it in such a way that editors will pay us some money, That young readers we may never meet will get why it was/is so cool or such a big deal. Or how it all lead to the way things are now. How it works. Or how it looked and felt at that particular time, at that particular place, with that set of individuals. What was it like. Why it happened in just that way. If you do all of that as you've learned to do, as your imagination and education has directed, as you pray you can still do, as your subject merits and your readers deserve, then your words cannot help but satisfy a worthy roster of curriculum standards. They'll be worth the precious time of some hardworking teacher, who can wrap his or her head around the eye-crossing language of committee-driven directives while juggling the endless needs of his or her paperwork-generating principal, school board, conflicted, tax-strapped, seed-corn-eating government; as well as his or her delightful/tender/cruel/bored/precious students and their parents plus all of their bumptious universe of challenges at their separate-but-manifestly-unequal homes..

And so we beat on, ignoring the Sirens on the Rocks, whispering about books we'd like to read. The new autumn movies in the theaters. Or those most seductive things: projects one should not be doing. Planting bulbs. Plotting a murder mystery (mine usually involves a dead art director, but I digress) for Nanowrimo coming up. Listing what you'll pack in the camper of one's pickup truck, a la John Steinbeck before heading out to see.... But no: We nonfiction types, we creative cogs in the great literary-education complex have a lot of explaining to do. The standards are high, but the yoke is easy and the burden is light.

Depending on what day you ask, anyway.

Published on October 21, 2013 05:00

October 18, 2013

Common Core Connections: In the Classroom

The Common

Core State Standards, voluntarily adopted by more than 45 states, is, according

to Joel Klein, former chancellor of the New York City public schools, “one of

the most promising education initiatives of the past half century.” For those of us who write nonfiction, it is

an opportunity to not only continue to write books that provide students with

knowledge and inspiration but also to share with teachers ways that our books

can be used in the classroom. Here are some suggestions for implementing the

Common Core standards with some of my books, by Sylvia M. Vardell, professor of

children’s and young adult literature at Texas Woman’s University, and

published in Book Links, November 2012.

In the classroom:

Use Ballet for Martha:

Making Appalachian Spring, as a springboard for discussing the power of

collaboration in creating a work of art. This is the behind-the-scenes story of

how the famous Martha Graham ballet, “Appalachian Spring,” came to be from its

inception through the composition of the score by Aaron Copland to the design

of the innovative sets by Isamu Noguchi. Invite students to identify key

moments of interaction between the players in the narrative and in direct

quotes (such as when Graham gives Copland a script and he responds with

comments that motivate her to rewrite).

But this book provides additional examples of collaboration,

too. Check out Greenberg’s web site (jangreenbergsandrajordan.com) for the

back-story on her collaboration with writing partner Sandra Jordan, editor Neal

Porter, illustrator Brian Floca, and even book designer Jennifer Browne. Or

share the audiobook adaptation of the book narrated by actress Sarah Jessica

Parker that includes a performance by the Seattle Symphony of the very score

that inspired the ballet. As a natural follow up, invite students to form

partnerships or small groups for their own collaborative projects, creating a

picture book, digital trailer, or audio podcast of their own.

Common

Core Connections

RI.5.3. Explain the relationships or interactions between

two or more individuals, events, ideas, or concepts in a historical,

scientific, or technical text based on specific information in the text.

In

the classroom: Asking questions is a big part of how

Jan Greenberg approaches art and writing about art and artists. While she was

growing up, her parents encouraged her with questions like these:

“What do you see?”

“What is the feeling

expressed in the painting?”

“Which is the best picture

in the gallery?”

Even within the narrative of several of her books, she

frequently poses questions to invite the reader to wonder, interpret, and

speculate. On p. 11 of Frank O. Gehry

Outside In, for example, she uses his famous Guggenheim

Museum in Bilbao, Spain,

to pose a series of questions that guide readers in “breaking down” the

building and considering it from multiple “angles.” Walk through these

questions with students to talk about the Bilbao Guggenheim or apply the same

questions to the buildings that are right there in their own environments (such

as their school building) since EVERY building is situated in a specific

landscape, made of various materials, and created in certain shapes, evoking

different feelings. Compare their responses and viewpoints with one another and

with the author.

Common

Core Connections

Ask and answer questions to demonstrate understanding of a text, referring

explicitly to the text as the basis for the answers.

Distinguish their own point of view from that of the author of a text.

In

the classroom:

Pairing

nonfiction and poetry may seem to be an unlikely partnership at first, but

these two different genres can complement one another by showing children how

writers approach the same topic in very different and distinctive ways, but

both strive to convey key concepts in clear language. After sharing some of

Greenberg’s picture book biographies (such as Action Jackson, Romare Bearden, Frank O. Gehry Outside In, and Ballet for Martha), guide students in

discussing key ideas in the life and work of the book’s subject. Jot those

ideas down, focusing on key words that are particularly vivid and descriptive.

Then challenge students to create “found” poems by arranging words (of their

choosing) from the list into poems. Share the poems and then add them to a library

display of the books. For examples of found poems from a variety of nonfiction

(and other) sources, see The Arrow Finds

its Mark edited by Georgia Heard.

Common

Core Connections

Determine the main idea of a text; recount the key details and explain how they

support the main idea.

Determine the main idea of a text and explain how it is supported by key

details; summarize the text.

Determine two or more main ideas of a text and explain how they are supported

by key details; summarize the text.

Published on October 18, 2013 01:40

October 17, 2013

What Jim Murphy Said

It's 7:30 am on the day of my monthly INK contribution and I have just done something for the first time in all the years I've been blogging for INK--I deleted the post I published here several hours ago.

I have been conflicted about writing about the CCSS, which is our theme for this month, since I started to draft my blog entry. That's because I've been conflicted about CCSS since it became a thing. Sure, it's great that awareness of interesting nonfiction is increasing. But teachers and librarians have been using nonfiction in brilliant ways long before committees started presuming they knew better. Wait, let me rephrase that. You see, I started out as an editor in elementary textbook publishing and I learned nearly 30 years ago that standards committees can suck the creativity out of learning, and that education standards are continually changing.

Great teachers are great teachers.

And no, I don't think about curriculum objectives and standards when I decide to write a book about something. (This is a real question I have been asked in many a conference setting.) And I never want to. If my books fit the standards and people find that useful, that is fine by me. Heck, I've even had guides written (thank you brilliant librarians who have helped me do that) so that people can connect my books to the CCSS if they so choose. But that is not a driving force for me as a writer. Passion is. Every time. If the topic is something I can't let go of, if it makes me crazy, or joyful, or outraged, or fascinated, and I just can't wait to immerse myself in the research, to pull it apart and turn it on its head, and make the best sense of it I can as I figure out the world right along with the rest of my fellow humans--that's when I know I want to write a book.

When I visit schools and talk to kids, I always make this point. If they are interested in something, their writing will be interesting. If they are passionate about something, their readers will be engaged. It's not about curriculum objectives. I leave that to the experts.

What was the post I deleted? It was basically about hating the label "informational text." And I do. Because that label steals all the passion from what I spend my life doing. I don't mind reposting that thought. But I deleted the post because I feared it came off as too snarky on a subject respected colleagues (on and off this blog) are writing about with grace.

So I re-read some of this month's CCSS posts and was impressed with all of them. There is valuable information here, which I do not want to tarnish. My original post had called my dear friend Deborah Heiligman's George Clooney and raised her a Robert Downey, Jr., and that part I'll keep! But it was Jim Murphy's post that I nodded my head to at every single sentence and said, yes, that's what I meant. What Jim said. What Jim Murphy said.

I have been conflicted about writing about the CCSS, which is our theme for this month, since I started to draft my blog entry. That's because I've been conflicted about CCSS since it became a thing. Sure, it's great that awareness of interesting nonfiction is increasing. But teachers and librarians have been using nonfiction in brilliant ways long before committees started presuming they knew better. Wait, let me rephrase that. You see, I started out as an editor in elementary textbook publishing and I learned nearly 30 years ago that standards committees can suck the creativity out of learning, and that education standards are continually changing.

Great teachers are great teachers.

And no, I don't think about curriculum objectives and standards when I decide to write a book about something. (This is a real question I have been asked in many a conference setting.) And I never want to. If my books fit the standards and people find that useful, that is fine by me. Heck, I've even had guides written (thank you brilliant librarians who have helped me do that) so that people can connect my books to the CCSS if they so choose. But that is not a driving force for me as a writer. Passion is. Every time. If the topic is something I can't let go of, if it makes me crazy, or joyful, or outraged, or fascinated, and I just can't wait to immerse myself in the research, to pull it apart and turn it on its head, and make the best sense of it I can as I figure out the world right along with the rest of my fellow humans--that's when I know I want to write a book.

When I visit schools and talk to kids, I always make this point. If they are interested in something, their writing will be interesting. If they are passionate about something, their readers will be engaged. It's not about curriculum objectives. I leave that to the experts.

What was the post I deleted? It was basically about hating the label "informational text." And I do. Because that label steals all the passion from what I spend my life doing. I don't mind reposting that thought. But I deleted the post because I feared it came off as too snarky on a subject respected colleagues (on and off this blog) are writing about with grace.

So I re-read some of this month's CCSS posts and was impressed with all of them. There is valuable information here, which I do not want to tarnish. My original post had called my dear friend Deborah Heiligman's George Clooney and raised her a Robert Downey, Jr., and that part I'll keep! But it was Jim Murphy's post that I nodded my head to at every single sentence and said, yes, that's what I meant. What Jim said. What Jim Murphy said.

Published on October 17, 2013 04:54

October 15, 2013

Common Core: Main Points & Key Ideas

Since

reading standards can be such a drag, I’ve come up with some easy-to-read

tables that make them seem almost friendly. Here’s an example:

Key

Ideas and Details #1

Kindergarten

Grade 1

Grade 2

With

prompting and support, ask and answer questions about key details in a text.

Ask and

answer questions about key details in a text.

Ask and

answer such questions to demonstrate understanding of key details in a text.

Grade 3

Grade 4

Grade 5

Ask and

answer questions to demonstrate understanding of a text, referring explicitly

to the text as the basis for the answers.

Refer

to details and examples in a text when explaining what the text says

explicitly and when drawing inferences from the text.

Quote

accurately from a text when explaining what the text says explicitly and when

drawing inferences from the text.

Key

Ideas and Details #2

Kindergarten

Grade 1

Grade 2

With

prompting and support, identify the main topic and retell key details of a

text.

Identify

the main topic and retell key details of a text.

Identify

the main topic of a multi-paragraph text as well as the focus of specific

paragraphs within the text.

Grade 3

Grade 4

Grade 5

Determine

the main idea of a text; recount the key details and explain how they support

the main idea.

Determine

the main idea of a text and explain how it is supported by key details;

summarize the text.

Determine

two or more main ideas of a text and explain how they are supported by key

details; summarize the text.

You can find similar tables for the other K-5 Reading

Informational Text (RI) standards on my pinterest page . I like them because they show how skills scaffold from one

grade level to the next.

The

tables above highlight the first two Common Core for ELA RI standards.

Basically, they say that after reading a nonfiction book, your kiddos should be

able to identify the main topic and key details in of the text.

This

certainly isn’t a new idea. In fact, it’s pretty basic. What’s the point of reading

if you don’t understand or remember the content? But as we know, this isn’t

always easy for kids, especially beginning readers.

One

great way to help students build their fluency and comprehension is Reading

Buddies. You can find a comprehensive article about the benefits of programs with multi-age reading partners here , but here's my special twist: Instead of using books at the

younger child’s reading level, use books with layered text.

The simpler text is

perfect for the young child, and the more complex text will challenge the older

child. So both students are learning. And after they finish reading a spread, they can discuss the art and

content—a practice that will certainly address CCSS for ELA RI #1

and #2.

My new book No Monkeys, No Chocolate is perfect for this kind of Reading Buddies

program. Here are some other books with layered text. They are also good choices for a Reading Buddies program in which both students participate fully.

Actual Size by Steve Jenkins

Beaks by Sneed B. Collard (illus. by Robin Brickman)

The Bumblebee Queen by April Pulley Sayre (illus Patricia J. Wynne)

A Butterfly is

Patient by Diana Hutts Aston (illus. Sylvia Long)

An

Egg is Quiet by Diana Hutts Aston (illus.

Sylvia Long)

Here

Come the Humpbacks! by April Pulley Sayre (illus. Jamie Hogan)

Meet

the Howlers by April Pulley Sayre (illus. Woody Miller)

Move! by Steve Jenkins & Robin Page

My

First Day by Steve Jenkins & Robin Page

A

Place for Bats by Melissa Stewart (illus by

Higgins Bond)

A

Place for Birds by Melissa Stewart (illus by

Higgins Bond)

A

Place for Butterflies by Melissa

Stewart (illus by Higgins Bond)

A

Place for Fish by Melissa Stewart (illus by

Higgins Bond)

A

Place for Frogs by Melissa Stewart (illus by

Higgins Bond)

A

Place for Turtles by Melissa Stewart (illus by Higgins

Bond)

Prehistoric Actual Size by Steve Jenkins

A

Rock Is Lively by Diana Hutts Aston (illus.

Sylvia Long)

A

Seed is Sleepy by Diana Hutts Aston (illus.

Sylvia Long)

Snowflake Bentley by

Jacqueline Briggs Martin (illus. by Mary Azarian)

What

Do You Do with a Tail Like This? by

Steve Jenkins & Robin Page

When

the Wolves Returned by Dorothy Hinshaw

Patent (photos Dan and Cassie Hartman)

Wings by Sneed B. Collard (illus. by Robin Brickman)

reading standards can be such a drag, I’ve come up with some easy-to-read

tables that make them seem almost friendly. Here’s an example:

Key

Ideas and Details #1

Kindergarten

Grade 1

Grade 2

With

prompting and support, ask and answer questions about key details in a text.

Ask and

answer questions about key details in a text.

Ask and

answer such questions to demonstrate understanding of key details in a text.

Grade 3

Grade 4

Grade 5

Ask and

answer questions to demonstrate understanding of a text, referring explicitly

to the text as the basis for the answers.