Exponent II's Blog, page 31

April 18, 2025

I Used To Work The Streets

We got a call on the radio- “26 Alpha”, accompanied by the street address of the shelter holding the sick man who was in his 50’s. I put the ambulance in gear and we took off toward the location.

Alpha is the least severe, then there is Bravo, Charley, Delta, and Echo. Echo means they are dead. These are just a few of the terms used by EMS over the radio.

“Never underestimate an Alpha,” I would say. They never were what you expected…or they were exactly what you expected…you just didn’t know when it would turn on you and be much worse than you thought.

We arrived at one of the men’s shelters in Salt Lake City. Cold, dark, slushy, we pulled the stretcher out of the back of the ambulance. Navigated ourselves to a dip in the curb, and swerved around the sleeping bodies on the ground outside because there was no more room inside the shelter.

(Image-for I Used to Work The Streets)

The gate opened and we were guided to the heavy metal doors. They opened and the smell hit. Sweaty bodies, whose clothes were drenched then dried in the smell of urine and bile. Trying to hold the heavy door open as we pulled the stretcher in, the front wheel hit a foot.

“Sorry!” I whisper.

The lights were low and the massive cement room about the size of a Mormon church house gym, had men lying side by side filling the entirety of the floor space.

“Where is he?” We asked the young 20 year old watching over the sleeping men. We were directed to a man lying on the floor. I stepped over other bodies to get to him to check his vitals.

Fever, profuse sweating, vomit and diarrhea covered his clothes. “Are you able to stand and walk to my stretcher?” I asked. I help lift the 6 foot something man with my 5’4” self and similar sized partner next to me. We all wobble as we navigate the other men’s bodies and make our way back to the entrance and the stretcher.

Once in the ambulance, I grab sheets and blankets, adjust the heat and grab a blue emesis bag…in case he vomits during transport. Tattoos cover my patient’s neck leading up to his face which had several tiny teardrops tatted next to his eyes. “Doesn’t this mean this man has killed someone?” I think to myself.

“Do you want me to be in the back?” My partner asked. “Um, yeah I’ll take you up on that.” I then drove and my male partner was alone with our patient in the back.

My partner busied himself making the man comfortable and watched his condition to make sure it did not get worse. But he was sick and moaning and we couldn’t get to the University ER fast enough for him.

Once at the ER, I opened the back doors. Feces spilled out of the pant legs of our patient onto the stretcher, onto the ambulance floor and ran out the door. The ER staff welcomed us outside (not common in most ER ambulance exchanges, but based on the details we gave them over the phone, they know better than to let us inside right away.)

There was an outer shower room that the University ER EMT took our patient into. They started to spray hot water over him and his clothes as they gently stripped him down to give him a thorough cleaning. I grabbed an outside hose that sprayed hot water onto our stretcher and inside the back of the ambulance. We then bleached, wiped, sprayed everything off, and kept the ambulance doors open to air the space out for a bit.

*ERs in Salt Lake City take in a large amount of the unhoused (I am sure ERs all over the U.S. do as well). They will clean the clothes, wash the bodies, and feed the mouths of people in this community. Nurses, Police, Fire, and other EMS personnel are the defacto “parents” of these adults with needs they cannot meet themselves.*

The next call? A 26 Alpha, 90 year old female. We drove to a high rise penthouse in the heart of Salt Lake City…just a few blocks north east of the shelter we had been to.

This time the newly cleaned stretcher is pulled down large hallways, but obnoxiously tight elevators (architects did not think through emergency response situations in designing elevator spaces). We arrived at a beautiful wooden door with nice crown molding all around. As we entered, the smell hit. This time nice perfume, clean spacious interior, and the sent of expensive furniture fill my nostrils.

A nice older woman was talking on the phone with her son on one of four sets of couches that the apartment contained. Large expensive rings cover her skinny delicate fingers. Her hair, perfectly in place, moved with her as she turned her head.

Framed pictures of George Washing kneeling in prayer next to another of Moroni with the golden plates are on the walls. There are large pieces of Chinese porcelain throughout along with other country’s and culture’s arts, indicating a lifetime of world travel and by the looks of it, missionary work. We help her onto the same stretcher as before, cleaned and with a new sheet covering the top. I then sit in the back and we take the same ride up to the University ER, this time we roll right through the building’s entrance.

I couldn’t, at the time, formulate the thoughts in my head and the juxtaposition of the two experiences. I loved that we gave them the same treatment to an extent, I felt uneasy by the living conditions of both as well.

Rich, poor, past criminal, harmless old women. Their base emergent needs were met with the same speed, the same care, the same transportation, the same destination.

Same.

But that is where the same treatment ended. We saved their lives long enough to go back to their previous conditions.

And I am left with conflicting thoughts.

**

Related article: Does the Church Use Our Tithing Dollars Responsibly? I Don’t Think It Does!

April 17, 2025

Guest Post: Leading No One

photo by Thirdman via pexels.com

photo by Thirdman via pexels.comI currently serve as the sacrament meeting chorister. I am fully aware that what I do is probably not really even necessary. As I look out at the heads of the congregation (heads, mind you, not faces and eyes, because no one is looking at me) I sometimes do feel a bit useless. Even my 15 year old son comments that no one in the congregation follows me. So every week I just think about how this calling pretty much epitomizes what it means to be a woman in this church.

The congregation probably doesn’t even know how to follow me (does anyone really know how to follow a woman’s leadership in the church? Do they ever really have an opportunity?). They don’t realize that when my arm starts waving, it’s time to sing. (this should be obvious but the fact that the first measure or so is often silent leads me to think they don’t understand this).

They don’t know that they should watch me to see how long to hold the fermatas or if we will be singing extra verses. Or maybe they know, but they don’t care? I am sure the congregation thinks they are following me (even though they don’t look at me? How does that even work?).

But really they are following the organist (who, conveniently enough for this analogy, is a man) because aside from starting when I give the first downbeat, the organist rarely follows me. So it doesn’t matter what I do, they sing what the organist plays. If I were in any of the few leadership positions I’m allowed to be in in the church, people would think they were following me, it would kind of look like it after all, but considering a man could potentially override any decision I would make, even in a leadership position, would I truly be leading anyone?

I am thanked a lot for doing this calling, more than I have been for any other calling I’ve ever had even if you don’t count the times I’m thanked over the pulpit. I’ve had people come up to me after sacrament meeting to thank me. I’ve received text messages telling me that they appreciate what I do. So I guess it’s important? Once someone even mailed me a handwritten note.

Once the bishop said he was so grateful for what I was doing because if he had to do it, he wouldn’t know how and he would just spell his name in the air. But here’s the thing, for all he knows that’s exactly what I am doing. He can’t even see me because, like in every sacrament meeting I’ve ever witnessed, I stand behind the bishopric. They have their backs to me. Those in the highest leadership positions in the ward have their backs to me. If what I am doing is so important and everyone is so grateful for it, why don’t those men make an effort to follow me?

Alison lives in the Midwest with her husband and four children. She teaches elementary school but wishes she was a world famous orchestra conductor.

Leading No One

photo by Thirdman via pexels.com

photo by Thirdman via pexels.comI currently serve as the sacrament meeting chorister. I am fully aware that what I do is probably not really even necessary. As I look out at the heads of the congregation (heads, mind you, not faces and eyes, because no one is looking at me) I sometimes do feel a bit useless. Even my 15 year old son comments that no one in the congregation follows me. So every week I just think about how this calling pretty much epitomizes what it means to be a woman in this church.

The congregation probably doesn’t even know how to follow me (does anyone really know how to follow a woman’s leadership in the church? Do they ever really have an opportunity?). They don’t realize that when my arm starts waving, it’s time to sing. (this should be obvious but the fact that the first measure or so is often silent leads me to think they don’t understand this).

They don’t know that they should watch me to see how long to hold the fermatas or if we will be singing extra verses. Or maybe they know, but they don’t care? I am sure the congregation thinks they are following me (even though they don’t look at me? How does that even work?).

But really they are following the organist (who, conveniently enough for this analogy, is a man) because aside from starting when I give the first downbeat, the organist rarely follows me. So it doesn’t matter what I do, they sing what the organist plays. If I were in any of the few leadership positions I’m allowed to be in in the church, people would think they were following me, it would kind of look like it after all, but considering a man could potentially override any decision I would make, even in a leadership position, would I truly be leading anyone?

I am thanked a lot for doing this calling, more than I have been for any other calling I’ve ever had even if you don’t count the times I’m thanked over the pulpit. I’ve had people come up to me after sacrament meeting to thank me. I’ve received text messages telling me that they appreciate what I do. So I guess it’s important? Once someone even mailed me a handwritten note.

Once the bishop said he was so grateful for what I was doing because if he had to do it, he wouldn’t know how and he would just spell his name in the air. But here’s the thing, for all he knows that’s exactly what I am doing. He can’t even see me because, like in every sacrament meeting I’ve ever witnessed, I stand behind the bishopric. They have their backs to me. Those in the highest leadership positions in the ward have their backs to me. If what I am doing is so important and everyone is so grateful for it, why don’t those men make an effort to follow me?

Alison lives in the Midwest with her husband and four children. She teaches elementary school but wishes she was a world famous orchestra conductor.

No, President Kimball. Priesthood holders don’t preside. They rule.

In 1974, Spencer W. Kimball, president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS), shared an ancient scripture about men ruling over women that sounds a lot like nails on a chalkboard to modern ears.

Unto the woman he said, …thy desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall rule over thee.

Genesis 3:16

Apparently, President Kimball didn’t like the sound of that either, so he suggested a revision.

I like the term preside over thee.

—Spencer W. Kimball, Sept. 17, 1974, Be Ye Therefore Perfect

Like President Kimball, most modern Latter-day Saints prefer the word preside over the word rule. Most LDS men I know respect women and don’t want to rule over them.

Preside is a friendlier term than rule, but is it accurate? Does the LDS Church treat men like presidents or rulers?

Presidents:

Are elected by their constituents Serve terms that eventually expire, creating an opening for different leadershipRulers:

Are assigned to the throne by birthright Their terms don’t expire, and there is no opportunity for other leaders to rotate in during their lifetimeLDS church leaders say men preside, but they mandate that men rule.

The nicer-sounding term preside has taken on a life of its own in the LDS church in the decades since the Kimball administration, with church leaders encouraging men to “preside” over women in increasingly benevolent ways. A church article published in 1973 about how men should rule over their wives—er, preside over them—now carries a disclaimer acknowledging that it reflects “practices and language of an earlier time.” (See Barlow, Brent A., Feb. 1973, Strengthening the Patriarchal Order in the Home)

I documented the history of the evolving Mormon definition of preside here.

The Evolving Mormon Definition of Preside

By the time LDS Church President Gordon B. Hinckley published the Proclamation on the Family in 1995, presiding sounded so benevolent that Hinckley saw no contradiction in assigning men to simultaneously “preside over” and be “equal partners” with their wives.

But some things never changed. Priesthood holders are still selected by birth (the boys) and permanently maintain their authority over non-priesthood holders (all women). These are the characteristics of rulers, not presidents.

Benevolence does not convert a ruler to a president. Both rulers and presidents can be benevolent; both can be tyrants.

In 2019, current church president Russell M. Nelson elevated the word preside to eternal significance and backed it with covenant-enforced strength by inserting the word into a temple ordinance. His administration replaced the script of the temple sealing ceremony with new marital vows mandating that the husband, not the wife, will preside in their marriage.

That’s not how presidents are selected.

King Oscar II of Sweden and Norway at the Throne of Sweden by Emil Österman, from the book Oscar II En Lefvandsteckning by Andreas Hasselgren, Fröleen, Stockholm, 1908

King Oscar II of Sweden and Norway at the Throne of Sweden by Emil Österman, from the book Oscar II En Lefvandsteckning by Andreas Hasselgren, Fröleen, Stockholm, 1908

Our Bloggers Recommend: Recognizing Arab American Heritage Month by listening to Breaking Down Patriarchy Episode 19: Palestinian Feminism – with Dr. Randa Tawil

Amy McPhee Allebest, an Advocate and Podcaster from Breaking Down Patriarchy, interviewed Dr. Randa Tawil “to discuss the history of Palestine, how the ongoing atrocities in Gaza are a feminist issue, and the most effective ways for everyday people to take action for peace.”

Click the link below!April 16, 2025

We need to talk about Paul, part 2

When I began studying Paul years ago, it was with the intention to learn more about the actual person and his actual writings. My initial New Testament class introduced so much uncertainty in the conversation about the Bible, which was always too certain about Paul (and everything).

So I was unprepared for the question posed, and answered, by Cavan Concannon. His book, “Profaning Paul,” an irreverent look at the man who is the founder of Christianity, almost immediately asked this question:

“Can Paul be redeemed? Can an archive of texts that supported slavery, demonized Jews, propped up dictators, naturalized the submission of women, and endorsed a whole host of other atrocities be welcomed into the struggle against racism, capitalism, fascism, and other ills? I argue no” (6).

That changed the nature of my study and led to other questions: Should Paul be redeemed? Is it worth the effort when so many other sacred texts exist? How can I approach all ancient scripture, which can generously be termed problematic, and find what’s good and valuable and beautiful while coping with what else is there: genocide, murder, human sacrifice, destruction, the utter unfairness and coldness of the God inscribed therein? How to make sense of the contradictions contained within the pages of scripture? How do I even find myself on those pages, amid words written by and for men, using male pronouns, proclaiming a male god, when I have to search for stories about women? When I have to search for women who had who were real humans, not unnamed or silenced or one-dimensional characters needed to tell a man’s story?

Read We need to talk about Paul, Part 1.

Paul: Take him or leave him?More than any of the facts and theories I’ve learned about Paul the Apostle and Paul the human man who walked, ate, slept, got sick and got cranky, these two things about the biblical Paul stood out. First, a lot of what is attributed to Paul is just not from him. They’re pseudonymous letters to which the author attached Paul’s name to give the writings legitimacy. There’s evidence that even in his legitimate letters, some of the worst pieces were inserted later by editors and revisors aiming for a prevailing narrative that men led and women followed, quiet and submissive. There’s ample proof, in the words of the New Testament and the historical context of the time, that Paul worked with women to start and support house churches and worked with missionaries who were women. A lot of signs point to the fact that Paul is not the problem.

The second, vital point—the actual problem—is this: In the 2,000 years since Paul, men of the church have used his words, or the words assigned to him, to oppress women, to treat us as lesser, to keep us away from pulpits and priesthood and power, to justify gender roles that give men visibility and authority and respect and keep women silent and submissive and invisible.

Is that Paul’s responsibility? Maybe, maybe not. In my mind, it doesn’t matter. The words with Paul’s name on them are dangerous, whether or not they are Paul’s words. In his book, “Liberating Paul,” Neil Elliott—who I think decidedly did want to liberate Paul from the weight of 2,000 years of oppressing the marginalized—wrote:

“The usefulness of the Pauline letters to systems of domination and oppression is nevertheless clear and palpable. This observation must be our starting point. It is not enough to protest that one or another remark in Paul’s letters has been torn out of context to justify acts or horror. Such distortions are too widespread and consistent in the history of Christendom to allow such easy dismissal. These distortions also rest too easily on generally accepted perceptions of who Paul was and what he was about” (9).

The damage has been done, over and over and over again. What’s worse is it continues to be done—these words continue to be weaponized against marginalized groups. I would argue that an apostle who testified of the grace of Jesus Christ and the need for unconditional love would advocate that such damaging messages be thrown out—that the focus of the church should be helping people feel the love of Christ, not clinging to outdated rules.

Approaching Paul todayThere is also the argument that Paul’s writings simply aren’t relevant. Throw out the letters that he didn’t write, and we’re still left with rules, admonitions, observations and chastisements for specific people at a specific time in specific circumstances. He never meant for them to be applied broadly to all sorts of problems. It’s irresponsible bordering on dangerous to slap his words onto today’s church.

And you know what? Church leaders know this. Look around at any church that believes in the New Testament. Imagine 1 Cor. 7: 8 being read over the pulpit: “To the unmarried and the widows I say that it is well for them to remain unmarried as I am.”

Let me tell you—as an unmarried woman, that was never the message I got in the pews of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The singles wards, the dances, the mixers, the—was it semiannual? quarterly? monthly?—talks and lessons reminding me to get married all made it clear that these particular words from Paul didn’t hold any weight. Those verses require context, or maybe they were a poor translation, or perhaps Paul just didn’t mean what it sounds like he said—all arguments made by Bruce R. McConkie. So church leaders routinely adapt the words of Paul, or the words attributed to Paul, for their needs.

Can Paul be redeemed?In defiance of that subhead, let’s forget about Paul for a minute. Let’s return to Dr. Concannon. More important than repairing Paul is repairing the lives of readers and hearers who have been hurt by Paul’s teachings.

“I don’t think there is an easy path to making Paul safe. In fact, it is probably an impossible task. What we can do, I think, is sit in the place of hesitancy and resist, for now, the inexorable scripturalizing drive to redeem Paul, to create yet another (useful) Pauline fiction to obscure who gets to control the Bible. To return to the metaphor that drives this book: Paul is shit. Don’t make him into fertilizer just yet” (12).

Can that be done if we keep Paul? Maybe. I can’t answer that. We can take what we like and leave the rest. It is not hypocritical to feel the love of God when reading Paul’s testimonies of Christ and also to reject what he says about slavery or women or how Christ wants us to follow bad governments. It is not all or nothing. Paul’s words can be right in some instances and wrong in others. They can apply in certain instances and not in others. None of us are bound to accept every word in the Bible as gospel truth. Arguably, we are bound to not accept every word as gospel but to study and consider and think critically and determine for ourselves, seeking personal revelation if that is our thing.

Where does that leave churches? It’s a hypothetical; I don’t know of a single Christian church that has opted to reject the writings of Paul in their entirety because he has and continues to do too much harm. Although there are some churches who are actively rejecting some of his teachings, including by having women be pastors and actively working for social justice, liberation theology and equality, they remain dwarfed among larger (white, American) Christianity. (I do not know enough about Christianity in other churches or about black churches in the United States to speak to them.)

I can’t make this decision—I haven’t even made it for myself yet. I still see good in Paul. But that doesn’t mean I should keep him. I will return once again to Dr. Concannon, who leaves a door to begin healing the wounds left by the apostle: “Paul can’t be redeemed; however, paying attention both to why he can’t and to what happens when interpreters try opens up space to hear new perspectives and forge new alliances that are necessary in the face of human futures that look increasingly polluted, authoritarian, and unequal” (6).

Top photo: Female statues of Sophia (Wisdom), Arete (Virtue), Ennoia (Insight) and Episteme (Knowledge) in the Library of Celsus at Ephesus.

Bibliography

Concannon, Cavan W. “Profaning Paul.” The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 2021.Elliot, Neil. “Liberating Paul: The Justice of God and the Politics of the Apostle.” Orbis Books, Maryknoll, NY 1994.A note about sourcing that highlights the problem: In my yearlong study on Paul, I read 12 books about Paul. Two were written or edited by women. I had a hard time finding sources from women, which leads me to wonder if women biblical scholars don’t even bother with Paul—if they’ve already decided he’s not worth redeeming.

What to the Mormon is Holy Week?

What to the Mormon is Holy Week? To the Mormon girl who grew up succored on a Christian superiority complex. Who listened to leaders and lectures from high pulpits on why we were a better church, a more advanced Christianity that didn’t dwell on the misery of death or the chains of old traditions. Who cut her teeth on stories of apostasy and great and abominable churches that clung to crosses and liturgies, while we had fulness and restoration.

Mormonism didn’t need . It had transcended it.

What was Palm Sunday but a well-known image of Christ’s triumphal entry discussed every four years when the New Testament happened to be the curriculum? Lent a joke. Holy Monday and Tuesday without notice. Spy Wednesday unheard of. Maundy Thursday a funny name. Good Friday a disgrace. Black Saturday unspoken of.

What to the Mormon were the traditions of millions of Christians around the world but background noise or something to turn up our noses at? After all, only the living Christ mattered. Crosses were symbols of death, of worldly priests and kings. Wearing one was unacceptable, a sign of active rebellion ripe for judgment. We side-eyed the extremes of those who acted out the stages of the cross. Laughed at testimony meetings at those who threw parades or processions. Shook our heads at those who went to special services on weekdays. Didn’t they get it? Didn’t they know that Jesus was alive and all their silly remembrances of His death were an abomination? Didn’t they know that they were only playing church? Not like us Mormons, those who really got it. Who really knew how to celebrate Easter. How to ignore Holy Week in the name of holiness.

Palm leaves. Suppers. Passion plays. Crosses.

Symbols we know but also do not. Symbols we claim but also reject.

And then Mormons became Latter-day Saints. Overnight.

What to the Latter-day Saints is Holy Week? Suddenly we want it. We hold it dear. We try to make it our own. Prophets speak on it as if we always knew it, as if they never spoke of it with derision. As if we never pointed our fingers from our great and spacious building in mocking at the other faithful servants of Christ.

Will we one day hold palm leaves? Or conduct Passion plays? Will we hold Good Friday services and nail our sins to a wooden cross laid across the altar? Will little children sticker foam crosses from Hobby Lobby and sing Jesus Loves Me? Will old women shuffle into the pews with gold and silver crosses dangling from their necks?

Do our Mormon pioneer ancestors, who pulled handcarts and shared beds with multiple wives, look down at us and wonder what we’ve done with their names? Do we reject them every time we pretend we’ve been Christian all along?

Then what to the Latter-day Saint is a Mormon? Why does my neck hurt from whiplash and my stomach ache from the pretending? The collective gaslighting. The changes with no grace and no apology for our past.

Where must I dig into my sinews to find Holy Week, the one I was taught to scorn or ignore, but apparently also to worship and love? How should I join in Palm Sunday, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday––names that sound foreign on my tongue? What to me is Holy Week, a tradition I was never given and a place I was never planted? How many times must I rewrite myself so an ever-changing Mormon Latter-day Saint God will be pleased?

What to the Mormon is Holy Week? Quite a lot and nothing at all.

April 15, 2025

Keys

Guest Post by Keely Richins

Unlocked

The men had the court, they didn’t have to say “please.”

After all, all worthy men have the keys.

Three days a week, the Stake President opened the door,

Early morning pickup ball, ‘Should we pray? What the hell for?’

What about the sisters? What about our ball?

But there’s no room on the schedule, no time at all.

Blocked.

Calls to the male scheduler, ‘This will take weeks!’

I counseled myself, ‘be basic, molded, meek.’

No time for you. Who will lock up?

Who will supervise? Who will clean up?

More weeks pass, call my Sister Presidents,

Talk to my Bishop, talk to my friends.

Alas, we got on the schedule, we put in the work!

I would have a calling, “Let no one shirk!”

Women had a Sports Coordinator, several days a week!

Success was felt-we did it-with almost no cheek!

“Let’s play!” I shout, the ball ready to serve,

‘Not so fast!’ Women must be organized,

a prayer had to be observed.

Then what did I learn, the next week after this hustle?

Men were awarded an additional day, without lifting a single muscle.

Well, we got what we wanted, isn’t that right?

Then why, oh why, was it such a fight?

I think it came down to who held the keys,

‘Oh you don’t want those, women, don’t be such a tease.’

Keely is a reader, runner, proud Utah native, Idaho backpacker, nightgown wearing millennial, friend, and rabbit-owner. She loves to laugh, be outside, and push herself outside of her comfort zone. She lives a thrilling life with a CPA and three kids in a home with a red door.

Into the Woods—Exponent II Retreat

Consider attending this year’s Exponent II Retreat on September 19-21, 2025, at the Barbara C. Harris Center in Greenfield, New Hampshire! Registrations opens May 3. Learn more here.

This essay was originally published in the Fall 2024 issue of Exponent II magazine.

On clear, chilly evenings at my home in Las Vegas, I sometimes revisit the memory of a late September night in the New Hampshire woods. I sense the moonlight like silver on my skin and, eyes closed, can almost feel the warmth of my friends flanking me. I breathe in deeply as my lungs recall our laughter, sharing of confidences, and releasing rage with collective feral screams at the stars.

That night was part of how I made peace with one of my biggest fears when I decided to step away from the Church: if I disentangle myself from Mormonism, will there be anything left of me?

* * *

I first encountered Exponent II around 2010. I read the Exponent blog for years as a budding feminist before daring to submit my first posts to both the blog and the magazine nearly simultaneously. Months later, I received my first issue of the magazine and experienced the thrill of seeing my name in physical print for the first time. Not long after, I became a permablogger and wrote for the blog monthly, eventually serving on the Exponent II Board as a blog rep and now as VP/secretary.

The first time I attended an Exponent retreat, I had never met any attendees in person. Always anxious to commit, I’d waffled back and forth for months before finally purchasing a slot from someone who could no longer attend and buying a last-minute plane ticket just two weeks beforehand.

The best cure for my social anxiety is to give it a job: if I can reframe my role as helper or leader rather than directionless attendee, I’m much more comfortable. So for each of the three years I’ve attended the retreat, I have led a small group discussion. The theme each time has been some version of how to create community and reclaim ritual outside of the Church. I brought no answers to our discussion groups because the questions are the very ones I’m currently grappling with. How can I establish meaningful rituals of my own without scaffolding from the Church? Where can I find community for my family if not in a ward?

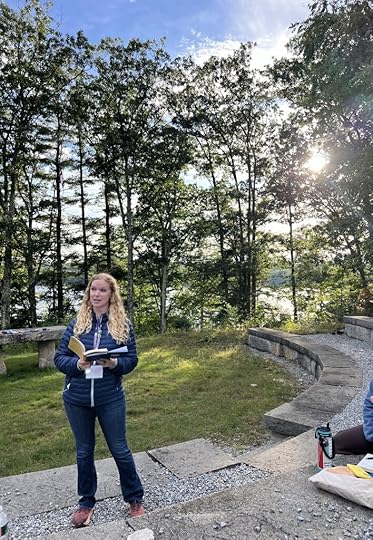

Leading a small group discussion at the Exponent II Retreat, 2023

Leading a small group discussion at the Exponent II Retreat, 2023My second year at the retreat, at the end of our small group discussion, there was a communal hunger for participating in ritual in a way that felt meaningful to us. Someone had described a burning ritual for letting go, and all ten of us sat with the idea of it, feeling a thrill at the thought of doing something primal and a bit witchy, wild, and freeing. Someone else looked around at the group and said, “We should do it.” And then, in a more timid voice, “Can we do it?” Ten pairs of eyes fell on me, and though I had no more authority than what they gave me, I said yes.

We arranged to meet up late that night, after the scheduled retreat events, by the stone table in the amphitheater. It felt like an auspicious beginning as we set off down the trail, armed with permission and borrowed matches from the retreat center. We chatted as we walked along the path by the lake, our phone flashlights illuminating the ground immediately ahead, surrounded by trees painted in muted shades of charcoal by the watery light of the quarter moon. We laughed so hard that a couple of us had to stop and crouch to the ground, our legs crossed tightly to keep from peeing our pants.

Fire licked the pine needle-kindling in the firepit, and we warmed our hands as the flames grew stronger. Each of us took a pen and a ripped half sheet of paper and wrote something we wanted to let go of. We spoke one by one and shared the burdens that were holding us back. Tossing the crumpled papers into the flames, we watched them flare brightly for just a moment, then turn to ash on the breeze. We stated our collective intention — to move forward and open ourselves to love and curiosity—then sang songs in a circle around the fire. I couldn’t help but hold back a little when we howled—literally howled—our feminine wildness and pain at the stars, but I loosened the strictures of my own innate prudishness when someone expressed a desire to disrobe in the dark. A few of us left the warm firelight, stripped and stood naked on the shore of the moon-dappled lake, reclaiming our bodies and feeling alive and completely present in the chill autumn air. I lifted my arms and reached to the sky, bathed in light from far-flung galaxies, unashamed.

* * *

When I stopped regular church attendance, my social circle shrank considerably and then disappeared almost entirely a couple years later when the pandemic hit. My world and connections felt so much smaller without the friendly acquaintances of convenience I saw and chatted superficially with at church. I found myself wondering, if I died, where on earth would they hold the funeral, and who, apart from my family and handful of close friends, would even come?

At the retreat one year, Julie Hemming Savage said, “When I go into hard situations, I can visualize my sisters flanking behind me in silent strength and support.” The mental image this produced for me was powerful and comforting; at the risk of sounding macabre, I pictured my Exponent community at my funeral. I could imagine the bloggers on our email backlists making note of my death and my life. I could imagine them saying, “she was here” and “she was part of this” and “we will not forget her.”

My friends Amy, Katie, Natasha, and I at Walden Pond on our way to the Exponent II Retreat, 2024

My friends Amy, Katie, Natasha, and I at Walden Pond on our way to the Exponent II Retreat, 2024I lost the bulk of my church community, but I gained a new community. While none of my Exponent friends live in my city, we connect in other ways and see each other when we can. We chat on Facebook, we comment on each others’ posts on the blog, we see each other at retreats, we touch base at virtual board meetings, we meet up on vacations, we monologue on the video app Marco Polo. When I go to Utah and have shows or concerts, my Exponent friends show up and support me. Once or twice a year, we sneak in a girls’ weekend and laugh and cry and confide and get way too little sleep. This community was the torch that lit the path through the darkest parts of my faith crisis.

Exponent II used to be based in Boston. Proximity was necessary for the work of publishing. But now, we’re spread throughout the country and the world, connected by the gossamer threads of Mormon feminism, advocacy, and friendship.

The questions I have brought with me to the retreat about meaningful ritual and community have largely been answered by my involvement with Exponent II. As I figure out who I am outside of the institutional Church, I feel the collective support of this community of friends and sisters buoying me up with their silent strength.

Sign up for the Exponent II monthly newsletter to stay updated with announcements and retreat registration information. As this blog series develops, read more blog posts about the Exponent II retreat.

April 14, 2025

We need to talk about Paul, part 1

The Sunday after I graduated from high school, I absconded from my youth Sunday school class and went to gospel doctrine. My father was the teacher, and as someone who loved studying and didn’t love manuals, it was a refreshing change from the rote lessons of youth classes.

Except for that one guy.

You know the guy: the one who is almost salivating to blame Eve in the Genesis discussions. The one who cannot wait to point out that Paul says that women aren’t supposed to speak in church.

Unfortunately, the words of the New Testament attributed to Paul do sound an awful lot like that “that guy.” And I hated “that guy”—justifiably, I still believe, since a lot of animosity toward women lives in those words. It’s taken more than 20 years, reading from three or four different Bible translations and getting a degree in religious studies to actually learn about Paul and realize that he wasn’t “that guy,” but rather, he was a guy whose words have been commodified and weaponized by the patriarchy, the ruling class, slaveholders and governments to give their deadly actions a sheen of “approved by God” instead of “done so I can grab and keep as much wealth and power as possible.”

I thought about this post for a while last month while on vacation in Turkey. Much of Paul’s missionary teachings run through Turkey, and I was especially eager to spend a day in Ephesus, where he spent time teaching and was the society to which the letter to the Ephesians is addressed. As I walked the marble streets and imagined the people of Roman times selling wares, exchanging information, worshipping their various gods, I thought about Paul—what I’d like to ask him, what I’d like to tell him, if he knows how sucker punched so many feel when they read his letters.

So. Let’s talk about Paul: Jew, Roman, possible Pharisee, founder of Christianity and overall complicated fellow—who probably didn’t even write the letter with his name on it that we now know as Ephesians.

Note: All scriptures are from the New Revised Standard Version of the New Testament.

Paul: What I didn’t know I didn’t know—an incomplete list1. Only about half of the letters attributed to him were likely written by him, according to most scholars: Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, Philemon and 1 Thessalonians. A couple of others (2 Thessalonians and Colossians) are up in the air. The rest almost certainly, or certainly, are not.

2. Paul never intended his letters to be compiled into book form. They were written to specific groups of people at specific times to address specific instances. Genuine letters shouldn’t be read as missionary tracts or general lessons: “A letter is one half of a dialogue or a substitute for an actual dialogue, in which the writer speaks to a person or persons as though they were present. … Letters are addressed to individuals or groups from whom the sender is separated by physical or social distance. One will misunderstand letters if one focuses only upon the ideas within them” (Pervo, 24, emphasis mine).

3. Paul is one of only two New Testament writers whose existence we know for sure. The mystic John of Patmos, who wrote Revelation, which is about the fall of the Roman Empire, is the other.

4. Paul had an ongoing feud with Peter and James. The latter two preached about law, while Paul taught grace. Paul believed that the law would become its own god and would supplant Jesus—that men would replace grace and faith with obedience to the law (Murphy-O’Connor, 153-4).

5. His name was almost certainly always Paul. Acts is the only place where “Saul” is found, and Acts is not a credible source on Paul. (It frequently contradicts his letters.) If both names were used, it was likely a difference of language: Saul is a Semitic name, where Paulus was Latin (Murphy-O’Connor, 42)

Paul: He-Man Woman Hater? It’s complicated.I’m not going to include a list of things the Bible attributes to Paul that are intended to keep women silent, subservient and without agency. Those words don’t deserve to be aired in this space. We all know them. We’ve all been hurt by them.

The main street of Ephesus. Top photo: The library of Celsus in Ephesus, one of the best preserved Roman ruins in the world. Photos: Heidi Toth

The main street of Ephesus. Top photo: The library of Celsus in Ephesus, one of the best preserved Roman ruins in the world. Photos: Heidi TothIn his book “Liberating Paul,” Neil Elliott tackles this question in depth. His first conclusion is that the worst of Paul’s words aren’t really Paul’s words; critical scholars by and large do not believe Colossians, Ephesians, 1 Timothy and Titus are authentic writings but instead are pseudonymous. Those letters include the “most offensively patriarchal texts in the Pauline collection” (52).

“Given the evidence in the remaining genuine letters that Paul held a number of women church leaders in high esteem as his peers in apostolic ministry, the way seems open to regarding Paul as far more sympathetic with the experience and leadership of women than the canonical picture of Paul has suggested” (Elliott, 52).

Remaining in actual Paul letters is 1 Cor. 14:34-35: “… women should be silent in the churches. For they are not permitted to speak, but should be subordinate, as the law also says. If there is anything they desire to know, let them ask their husbands at home. For it is shameful for a woman to speak in church.” And, yikes. That’s not good.

It also might not be Paul. The oldest manuscripts of what we call the New Testament are copies of copies of copies of copies, and revisers and editors and translators added and subtracted things to stick to the overall script. According to Elliott, many scholars suspect these verses were added in later by someone who was not Paul; there is “textual disturbance” in the manuscript tradition that point to those verses not being original (52-54).

But what about 1 Corinthians 7, which says some weird things about women and marriage—none exactly demeaning; right after he says a husband has authority over his wife’s body, he proclaims that a wife has authority over her husband’s body (v. 4). (He also says, “each man should have his own wife and each woman her own husband.” One. Not more. Just the one.)

And then there’s 1 Cor. 11:2-16, in which Paul writes that the husband is the head of his wife (v. 3) and that a woman should not pray or prophecy with her head uncovered (v. 5). On the plus side, that verse suggests it’s fine for women to both pray and prophecy, seemingly in public because how would anyone know if she’s prophesying with bare hair in private? On the negative side—well, many of us have veiled our hair while approaching God, and many of us likely have strong feelings about that. I do. I shouldn’t have to cover my authentic self to approach the sacred.

There’s more in 1 Corinthians 11, including that woman was created from and for man (v. 8-9). It’s not great, no matter how generous I try to be. Elliott also tried to be generous: “Both these passages are notoriously difficult to interpret, particularly given their character as one half of a conversation … But aspects of 1 Corinthians 7 can be described as a ‘frontal assault on the patriarchal ethos of the age (Elizabeth Schüssler Fiorenza); and whatever else the discussion of head coverings in 11:2-16 is meant to accomplish, at any rate it clearly recognizes the authority (exousia) of charismatic women to lead the congregation in prayer and prophecy. If not a ‘feminist,’ Paul was clearly not the misogynist the Pauline tradition quickly made him” (203).

What else is authentic Pauline scripture?

Phoebe is named as a deacon of the church at Cenchrae, and Paul tells the Romans to “welcome here in the Lord as is fitting for the saints, and help her in whatever she may require from you, for she has been a benefactor of many and of myself as well” (Romans 16:1)Prisca, or Priscilla: She and her husband, Aquila—her name comes first—work with Paul in his missionary efforts, and they “risked their necks for my life” (Romans 16:3)

Junia: She was in prison with Paul and was “prominent among the apostles” (Romans 16:7). I’ve heard attempts to read that as “apostles knew who she was.” Fine. I’m a writer and reader and I spend a lot of time with the English language, and the simplest, most logical way to read that statement is that Junia was not just an apostle, but she was in fact a well-known apostle among the apostles.

Apphia: She is greeted alongside two men in the opening verses of Philemon; the greeting includes “to the church in your house,” which presumes the house church is equally Apphia’s as the two men (Philemon 1:2).

Euodia and Syntyche: Two leaders in Philippian house-churches were having a disagreement; Paul urges the people to whom he is writing to “help these women, for they have struggled beside me in the work of the gospel, together with Clement and the rest of my coworkers” (Phil. 4:2-3).

Of course, far more men are named and addressed these letters. Paul wasn’t a feminist—certainly by our standards today, but not even in the way the scriptures portray Jesus to be. But there’s scriptural evidence that he worked with women, that he appointed women to be leaders, that he valued their opinions and efforts and contributions. Why would a man who relied on a woman missionary turn around and tell her to ask her husband? Why would a man founding a church that was upheld by wealthy women tell them not to speak in church—churches that were held in those women’s homes?

But there are things that being in Ephesus brought up. First, let’s talk about all of the other groups who have been harmed in the last 2,000 years because of words on a page that have been attributed to Paul.

Slavery, antisemitism and governmental abuseIn his 2021 book “Profaning Paul,” Cavan Concannon spends 200 pages examining in detail what wrongs Paul has been foundational to. Here’s a start: In 1740, evangelist George Whitefield used Christian teachings, including the writings of, or attributed to, Paul, to advance the cause of slavery. Other Christian missionaries helped forge the discourse of Protestant white supremacy that adapted with the slave system in the Americas (23).

Today, white Christian nationalists similarly wield the Bible against Black people, Christian and non-Christian alike. Concannon wrote: “As European colonizers invaded what for them were vast new territories, they brought missionaries and Bibles with them. These played the double role of justifying colonialism and explaining the peoples, practices, and cultures that the Europeans ‘discovered.’ … As Christian theologians confronted the new diversity of their colonial conquests, they reworked earlier epistemological and hermeneutical frameworks to invent ‘biblical’ histories for non-European peoples; undercut, demonize, and eradicate local textual and ritual traditions; and justify Europe’s national and religious superiority and its concomitant right to rule over new ‘barbarous’ Others” (35).

Today, white Christian nationalists similarly wield the Bible against Black people, Christian and non-Christian alike. Concannon wrote: “As European colonizers invaded what for them were vast new territories, they brought missionaries and Bibles with them. These played the double role of justifying colonialism and explaining the peoples, practices, and cultures that the Europeans ‘discovered.’ … As Christian theologians confronted the new diversity of their colonial conquests, they reworked earlier epistemological and hermeneutical frameworks to invent ‘biblical’ histories for non-European peoples; undercut, demonize, and eradicate local textual and ritual traditions; and justify Europe’s national and religious superiority and its concomitant right to rule over new ‘barbarous’ Others” (35).

This isn’t just words being misused either; Paul is not innocent. I’ll talk more on this in the next section, but he set out to destroy the religions that were native to the areas where he preached. And he called it missionary work. Millennia later, his spiritual descendants used his words to destroy the native religions of what is now North and South America.

His words were also preached to enslaved people in the Americas, who were told that God “expected them to be obedient to the slavers and honest and hardworking in their labors. This god also expected them to stay slaves and not seek their own liberation “(Concannon, 82).

A short list of other instances of abuse, according to the author of “Liberating Paul,” include:

1 Thess. 2:14-15 was used to justify violence against Jews (4).In 1637 in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Anne Hutchinson was charged for violating 1 Tim. 2:12, which says that women shouldn’t preach in church (4).

Romans 13:1, which says to obey the government, was used in the Guatemalan civil war in the 1980s (verify) to convince the people to accept the military despite its myriad abuses, particularly of Indigenous Guatemalans (9). It was also used by the United States to justify its attacks on liberation theologists in Guatemalan churches, as Reagan-era leaders believed the appropriate use of the Christian church was to defend “private property and productive capitalism” (15-16).

That same verse in Romans stifled Christian opposition to Nazism and was used to promote enthusiasm for Hitler in ecclesiastical councils (13).

Oh wait, there’s more from Romans 13. Verses 1-7 were used in South Africa to defend apartheid; it was read as giving absolute, possibly even divine authority to the state (14).

Puritans relied on 1 Cor. 7:17 and 24, which says to be satisfied with one’s calling, and the commands of subordination in 1 Timothy and Ephesians to wives, slaves and children (11).

That’s … a lot. It’s one reason why context makes all the difference. Paul was preaching in Roman territory and trying to convert Romans and trying to not get into much trouble with the Roman government. He didn’t want to be seen as preaching the overthrow of the government. We shouldn’t read that two millennia later as a commandment to submit ourselves to an abusive, overreaching government. Nor should anyone has used the words of Paul—who not only was Jewish but was a Pharisee—to condemn Jews. His writings did not do that.

But someone’s writings could be read that way. That’s why we have to understand the origins the Bible better. This isn’t a book that God wrote, that’s perfect and untouched and holds the answers. It’s a series of dozens of writings, put down over the course of hundreds of years, copied and translated and revised and altered, then voted on at the Council of Nicaea, all by men in power. We need to understand the context and history. We need to understand the process of translation—that every translation is really the interpretation of the translator[s], who are fallible.

Paul—and Heidi—in EphesusLet’s return to Turkey. Ephesus, which is one of the best-preserved Roman heritage sites of its time, was home to one of the original Seven Wonders of the World: the temple of Artemis, the goddess who was protector of this once-great city. According to legend, the city was founded by the Amazons, the legendary race of woman warriors, and named for their queen, Ephasia. As other societies moved into the Artemis and the Amazon queen merged into Artemis Ephasia, a powerful, venerated goddess.

A statue of Artemis Ephasia in the Ephesus Archaeological Museum. She is not a mother–she famously swore off men, in fact–but she is often referred to as mother of the city because she is its protector. “Mother” was a title of respect in many cultures in the millennia before the New Testament.

A statue of Artemis Ephasia in the Ephesus Archaeological Museum. She is not a mother–she famously swore off men, in fact–but she is often referred to as mother of the city because she is its protector. “Mother” was a title of respect in many cultures in the millennia before the New Testament.

Even before that—millennia before, in fact—the Mother Goddess was worshipped in the Ephesus area. Archaeologists have found statuettes of this goddess. Cybele of Anatolia was also worshipped in this area. This was a city and a region with a history of strong women and female leaders.

Ironically, Paul didn’t entirely or immediately destroy this legacy. Prisca and Aquila were the real founders of the church in Ephesus; Paul accompanied them initially but then left. The married couple spent years in Ephesus doing missionary work before he returned (Murphy-O’Connor, 171).

But Christianity, as a patriarchal religion, could not allow this goddess veneration to stand. It undercut the one true god narrative. There is a virtual reality experience at Ephesus; in the second room we are introduced to Paul, who is arguing with a disciple of Artemis. Paul chastises the other man, saying (according to my memory), “you worship a manmade God.” I stood there, stunned at the hubris. Maybe I would have felt differently had I lived in first-century CE Ephesus, but standing there in 2025, all I could think was, “And what is the Christian god if not a manmade god—a male god literally created by and for men to give them power over others, to fight their wars, to carry their prejudices and hatred?” I’ve come to believe that everyone on earth who believes worships a god of their own creation—one who looks like them, speaks like them, sees the world and others in it through their own eyes. It’s not always malicious; it’s just that God is too big for us to understand. So we make God small. We make God familiar. Comfortable.

But what do we do with Paul—writer of beautiful sermons on love and grace and writer of words that have been used to enslave, capture, demean, silence and kill? I’ll discuss that in Part 2 on Wednesday. In the meantime, this 2022 post on Heavenly Mother offers insight into Mormonism’s Mother Goddess, how she got lost and how we can find her again.

Bibliography

Concannon, Cavan W. “Profaning Paul.” The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 2021.Elliot, Neil. “Liberating Paul: The Justice of God and the Politics of the Apostle.” Orbis Books, Maryknoll, NY 1994.

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome. “Paul: A Critical Life.” Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1996.

Pervo, Richard I. “The Making of Paul: Constructions of the Apostle in Early Christianity.” Fortress Press, Minneapolis: 2010.