Exponent II's Blog, page 35

March 21, 2025

Spirituality Without A Home

I used to read the illustrated children’s scriptures to my daughters. The LDS versions to be sure. I would tell my oldest, who was four years old at the time, that she couldn’t go out to play on the playground until she had. I was that committed.

We were reading the Old Testament version, Noah’s story, when my oldest got fixated on seeing a rainbow after reading that God had sent one to Noah after the flood receded.

“I want a rainbow!” She said

We lived in New Hampshire at the time, rain showers and rainbows were abundant.

“Sure, just wait a little bit, we are sure to get some rain and we can look for the rainbows.”

“I want to see a rainbow!” This was on repeat out of my daughter’s mouth all day for several days. “Just ask God to send you one!” I ended up responding.

Then, sure enough one day not too long after, I was looking out the window, saw a little rain shower and low and behold, there was a rainbow about four feet high and six or seven feet wide, right in our backyard.

I yelled for my daughter to come outside and see.

“God sent you a rainbow!”

We ran outside to get a closer look. My daughter danced in the rain and sang, “God sent me a rainbow!”

I stood there in front of it, staring. I was trying to figure out how on earth the small amount of rain and sunlight were producing this small rainbow, just in my backyard. The colors were incredibly bright. It was beautiful. I reached out to touch it, who could resist?

As I reached my hand out to touch the rainbow, it started to float slowly backward and up into the sky. As it did, it got bigger and bigger, until it filled the sky-massive and bright.

I stood there astounded.

Woah.

What did I just witness? Just me. My daughter was still dancing, oblivious to what I had just experienced. She later said to me as a teen that she never prayed for a rainbow, the experience holds no meaning for her.

I said out loud at the time, “well, I know God exists.”

[image error](free stock photo, I did not have a smart phone for another 5 years, back when we didn't always have cameras on us)How I view Diety now has completely shifted. But the experience holds true and I believe there is something there that is aware of us.

“Perhaps the most damaging thing organized religion can do, is take God away from people, and put it in the hands of the religion.” -Stephanie Brinkerhoff

This may sound harsh to some, but the idea that religion takes the spiritual experiences we have, then tells us that those experiences confirm that the “church is true” or that “Joseph was a Prophet” or that “the baptist church is true” or that “Mohamed was called of God.” Is robbing a spirituality that needs no claim on a religious home.

Spiritual experiences abound, whether products of the mind or seen with eyes wide open, and they don’t just happen to members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints-or who have the gift of the Holy Ghost.

I know people’s experiences can be very specific…there is no reason to argue over other people’s personal experiences.

But as I look back on the many impressions, feelings, insights, sights and wonders I have seen. I am left with only this:

There is something God or Godlike that exists and I am known by it.

I am okay with ambiguity.I have been taught to fear the unknown all my life- as in, not knowing the answers is so scary for others who don’t have them. I have been fed “perfect” answers to all of life’s questions of the here and now and the beyond to help me feel safe.

In fact, as a missionary 20 plus years ago, my missionary guidebook at the time told me to look for people to teach who had just lost a loved one or had bikes in the yard that indicated kids at the home. This was so that I could give them the perfect answers to ease anxiety or pains they had. An “easy fix”, if you will, to the feelings we all go through in life.

I’ve learned different ways to heal and find peace that feel similar to the ways I would call on Jesus for the atonement…but this time, it was me.

I have stripped away all that felt wrong and didn’t make sense and I am left with my own beautiful experiences that tell me I am loved, even if I do not know the how and why of it all. My spirituality does not need a religious home.

**

Other related articles: Here, Here, and Here- Spiritual, But Not Religious.

March 20, 2025

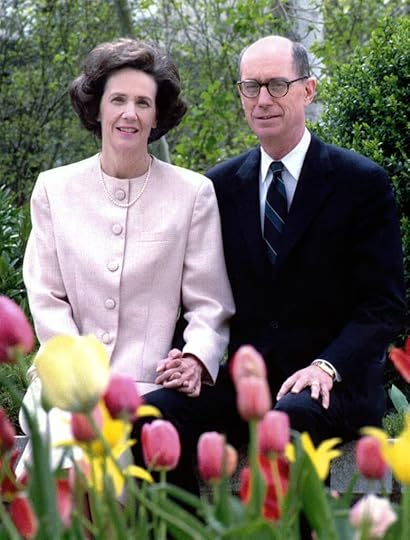

Guest Post: These Magnificent Men–And Their Wives

I don’t like attending Stake Conference.

It’s too itchy for me – a time when the patriarchal bureaucracy of our church is on full display. I’ve avoided it for years, but this time, I decided to show up. Something interesting was happening: the turnover of our stake presidency after a nine-year tenure.

I sat next to my husband on hard metal chairs. Although we had arrived at the stake center forty minutes early, it was still not early enough to claim the cushy chapel seats–those were all taken. Instead, we sat in the open cultural hall with basketball hoops above our heads, surrounded by chatty families.

I was uncomfortable, 30 weeks pregnant with our third daughter, wearing a pair of elastic pants that fit too tight. It was going to be a long couple of hours, but nevertheless, I was there, and I was curious.

A visiting authority from Utah took the stand to conduct. On assignment from the First Presidency, he was one of two men who had traveled into our area to call our new stake president. To open the meeting, he explained the process to us: over the course of two days, 36 men from the stake had been interviewed for the position. Afterward, the two interviewers–these visiting authorities–took time separately to pray about the candidates, and then come together to reach a consensus.

“The scriptures teach that ‘the Lord looketh on the heart,’” he said, “We didn’t look for the biggest, tallest, or best-looking man.” (Cue laughter from the audience.) “We looked for the man God had chosen.”

With that, the old stake presidency was officially released, and the new presidency was called. Three men popped up from different places in the congregation and joined the old presidency up on the stand, taking their places on either side of the pulpit.

Six men in suits smiled down at the us–pictures benevolent authority, products of unquestioned revelation.

For the next hour, they each got up to bear their testimonies, expressing similar messages of gratitude, love and humility. I was struck by their sincere, earnest hearts–by the real sacrifices they made to serve.

Afterward, the conducting authority once again addressed us. He gestured to the men sitting on either side of him and said, “We’d like to thank these magnificent men–and their wives–for their sacrifice and service. Now, let’s sing an intermediate hymn…”

Within minutes the building was filled with hundreds of voices singing together in unison. My husband looked over at me and took my hand. I was sitting there with a hand wrapped around my bulging stomach, tears streaming down my face.

I studied his worried expression and squeezed his fingers–I’m fine.

But in my head I was screaming, so loud I hoped, somehow, he could hear, “Something is very wrong. I am not, in fact, fine.”

……

In my experience, pregnancy is uncomfortable, all the time, everywhere. Your skin stretches and your feet swell and your lungs get squished, crowded by a growing fetus. But the discomfort is worth it. Giving birth to something new and precious is an incredible reward.

I have learned not to fear discomfort, or balk from it. Instead, I treat it like a crying child tugging at my sleeve. I pick it up, soothe it, ask it what’s wrong. Often, it has an important message to tell me.

I’ve come to think of discomfort as the Spirit in disguise–the catalyst to a better way.

Surrounded by singing saints, pregnant and crying, I wondered, what was my discomfort telling me now?

I decided to listen.

…..

“We looked for the man God had chosen.”

As a lifelong member of the church, I’ve been blessed by the leadership of good men, many times over.

I cannot deny that God works through our imperfect systems, through the very real sacrifices of our leadership. I have seen inspiration shine through the cracks–lives changed, people blessed.

But I truly, truly believe that God works despite these systems, not because of. We block our access to the greater fullness of God when we refuse to learn from our systemic imperfections and do better.

“These magnificent men–and their wives”

It’s no secret that our church is built for men, specifically married men, designed to serve their needs and reinforce their authority.

By contrast, the only way for a woman to have any semblance of power is to be power-adjacent. To be an influence, an auxiliary, a wife.

The church limits itself by holding onto patriarchy with tight, stubborn fists. The lack of diversity in our leadership creates an echo chamber of ideas and perspectives. Problems surrounding inequality–instead of being met with real solutions–become frustrated, circular.

Could this be what God wants? For an entire gender to remain stunted, voiceless?

…..

In his book Restoration, Patrick Mason reflects on what it could mean for Latter-day Saints to participate in the “ongoing restoration” of the gospel. He argues that every generation must “let go of old baggage” to discover the gospel anew, and bring all of God’s children closer to wholeness.

It seems to me that true restoration is not passive. It may require the courage to dissent, to imagine what could be.

What would it look like for the women in our church to not just be supportive side characters, but collaborative partners–true, autonomous leaders?

For a closed stake council meeting to have an equal number of women and men sitting around the table, each providing insight, making final decisions?

For a female Primary or Relief Society president to execute their own callings (like a bishop and elders quorum president can)? To sit on the stand in church meetings with full administrative authority? For their presence to not be a threat, but a norm?

What would it look like…for a female stake president to called? To grow with the opportunity to lead? To also become “magnificent”?

What would it look like for gender equality to not be considered radical, but common sense?

….

The intermediate hymn moved into the final verse.

I looked up at the row of suits on either side of the stand, considering the power that the church granted them: to administer, to lead with complete, unquestioned authority, to hold the “keys.”

And I considered my power–given by God: to carry the little life growing inside of me. To bring these daughters into the world and raise them, teach them, love them. To be the first voice of authority in their lives.

A realization dropped like a cold stone in my heart. If I did my job right–taught my daughters about who they were, and what they could be–they would eventually see the church’s sexism for what it was. They would likely not tolerate it, as I have been willing to for all these years.

The chapel organ thundered the final notes, and I was a mess of emotions–so grateful for this church that had blessed me throughout my life, and so sad for the real limitations I felt, but could not change.

I felt so alone, sitting in that metal chair. And yet…

I knew that I wasn’t. I was in the company of many, many women, who saw what I saw, who had fought for equality long before me and would fight long after.

Maybe the church’s insistence on patriarchy is part of an extinction burst; an increased intensity of old ideas, in the face of a growing threat of progress.

Maybe change will only come when a new generation–raised by these women–grows up and says, finally, enough is enough.

Like the daughter beneath my hands, maybe hope is gestating.

Waiting for the right time to be born.

March 19, 2025

The Lost History of Relief Society

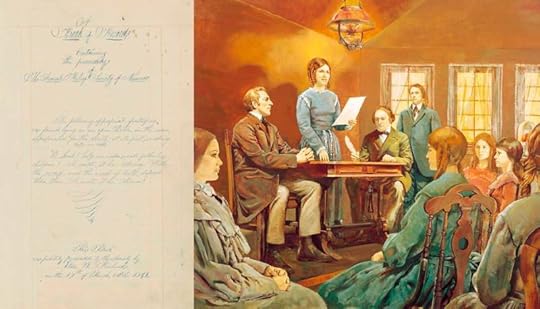

On March 17, 1842, twenty women gathered in the upstairs room of Joseph Smith’s red-brick store in Nauvoo to form a women’s society. These societies were common in antebellum America to root out society’s ills and for women to gain social power. Along with them in the upper room were three men: Joseph Smith, John Taylor, and Willard Richards. After hearing of the women’s intentions, Joseph insisted he had a better idea. “I will organize the women under the priesthood after the pattern of the Abrahamic Order,” he declared.

And so the Female Relief Society of Nauvoo was born—organized under the direction of men.

What women’s organization doesn’t have a man constantly overlooking it? Image from churchofjesuschrist.org

What women’s organization doesn’t have a man constantly overlooking it? Image from churchofjesuschrist.orgJoseph selected Emma Smith to be the first president and granted a level of autonomy and institutional priesthood power to these women. He saw the Relief Society as a way to harness women to do the moral cleansing that he wanted in his society. He especially hoped to use them to stomp out gossip about his growing secret of plural marriage. He also saw the opportunity to test out future temple rites.

The women, however, didn’t see their organization in the same way. They believed that priesthood keys had been given to them and they could function how they saw fit. Emma especially embraced this chance for power and influence. She grew the society to over 1,336 members within two years. She thought no sinner should be spared from the society’s purging, especially those engaging in polygamy. Many of the members of Relief Society were themselves secretly married to Joseph Smith. The organization soon became a battleground for Emma and Joseph as she tried to expose those marrying her husband and he tried to control her knowledge of the practice.

By the end of the Nauvoo period, Brigham Young hated Emma Smith and saw the Relief Society as one of the causes of Joseph’s martyrdom. Soon after Joseph’s death, he had the society shut down. In a meeting with Seventies nine months after Joseph’s death, he said, “When I want Sisters or the Wives of the members of this church to get up Relief Society I will summon them to my aid but until that time let them stay at home & if you see Females huddling together veto the concern.” He further stated, “I say I will curse every man that lets his wife or daughters meet again—until I tell them—What are relief societies for? To relieve us of our best men—They relieved us of Joseph and Hyrum.”

Not all historians agree that the Relief Society was unilaterally shut down by Brigham Young though. Katie Ludlow Rich argues it was more of a choice by the women in this chaotic time, and throughout the years they continued informal Relief Society work.

Either way, Relief Society stopped functioning officially as a church organization for two decades.

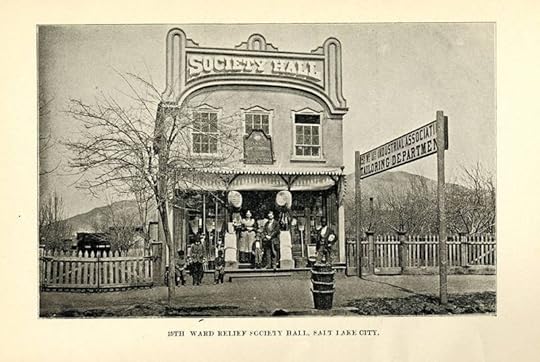

A Relief Society Hall in the 19th century. These building were fundraised, owned, and operated by women in the Relief Society.

A Relief Society Hall in the 19th century. These building were fundraised, owned, and operated by women in the Relief Society.In 1867, Brigham called for bishops to re-organize Relief Societies in Utah. He saw women as a vital tool for his self-sufficiency program to be independent of the outside world. Eliza R. Snow traveled throughout the territory with her original minutes book teaching women about Relief Society. In 1880, she became the President of the organization, although there wasn’t a strong central leadership yet. Women formed their Relief Societies locally and raised funds to build their own Society Halls to house both cooperative stores and meeting spaces. Most early Relief Society meetings met semi-monthly, dedicating one meeting a month to caring for the needs of the poor and the other to learning and instruction.

The Relief Society was an organization for social reform, including pursuing women’s rights. Thanks to the efforts of suffragists in the Relief Society—and the federal government’s desire to stamp out polygamy—women gained the right to vote in Utah territory in 1870, becoming the first in the nation to exercise this right.

Relief Society women started the Woman’s Exponent newspaper to both fight for equal rights and defend the church and polygamy. It remained the biggest publication of the Relief Society for decades.

Relief Society suffragist women meeting with Senator Reed Smoot at Hotel Utah in 1915. Image from National Parks Service.

Relief Society suffragist women meeting with Senator Reed Smoot at Hotel Utah in 1915. Image from National Parks Service.During this time period, women also held onto their priesthood rights. They practiced healings, blessings, anointing and laying on hands the same as men. Joseph Smith taught the Relief Society in an early meeting that “there could be no evil in it, if God gave his sanction by healing… there could be no more sin in any female laying hands on the sick than in wetting the face with water.” He further stated, “If the sisters should have faith to heal, let all hold their tongues.” Women would bless their fellow sisters before childbirth and their own children. Women also prepared the sacrament during this time.

The Relief Society at the end of the 19th century wasn’t, of course, equal to the male organizations of priesthood within the church, but it did exercise autonomy. The Relief Society fundraised their own budget, built their own buildings, created their own curriculum, ran their own newspaper, and elected their own leadership. But in the 20th century, the men would change all that.

In 1907, President Joseph F. Smith oversaw the first big overhaul of church consolidation and correlation. Members’ standing in the church became dependent on their participation in their local wards, and organizations fell directly under ward leadership. Relief Society stopped building separate halls for their activities and all church business shifted to the ward building.

When Amy Lyman became president in 1909, she was the last of a progressive generation. Institutional pressure forced the Relief Society to lose some of its broad autonomy as the church took over all the properties they owned. Male leaders spoke out against women performing healing blessings. But President Lyman was determined to continue the Relief Society’s legacy as an organization for social reform. She replaced the Woman’s Exponent with The Relief Society Magazine, and focused more on temporal reform and inspiring young women to became leaders. She also reworked the organization of the Relief Society into one central organization. The Relief Society’s focus for the next few decades was helping the poor and sick, providing education and welfare, teaching work skills, and providing resources for women. It was an organization focused on the secular more than the spiritual, aiding in war efforts and cross-organizational programs such as the Red Cross.

Relief Society magazine from 1930.

Relief Society magazine from 1930.In the 1920s, President Heber J. Grant oversaw more bureaucratization of the church. Male leaders curtailed women’s ability to perform priesthood blessings and the priesthood became solidly associated with worthy, white, male members only. In the 1940s, the Relief Society’s independently-raised budget was rolled into the general church fund controlled by the male priesthood. President Lyman’s social work was officially cut off by J. Reuben Clark of the First Presidency, and the Relief Society had to focus solely on the faith and testimony of women. Clark stated in General Conference that the Relief Society was to be “the handmaid to the priesthood.” (The definition of a handmaid is a “subservient partner.”)

In 1945, President Lyman resigned from her position and the male leadership chose Belle Spafford as the next president. Much more conservative, President Spafford took Clark’s explicit command to make the Relief Society “a companion organization to the priesthood” seriously. She focused on aligning with church (i.e. male) priorities and the traditional gender roles emerging from the end of WW2. The Relief Society officially rebranded as the Relief Society of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

President Spafford taught, “one of the Relief Society’s first concerns is the task of guiding, directing, and training its members in their vital role of mother and homemaker.” Long gone were the days of promoting female rights, leadership, and social reform. These efforts went hand in hand with the cultural retrenchment of the church during the 1950s and 60s, as the church married itself to the postwar conservative patriarchy. Male leaders became obsessed with conservative politics, fighting communism, and the nuclear family as the bedrock of the church.

Relief Society women in the 1950s. Image from reliefsocietywomen.com

Relief Society women in the 1950s. Image from reliefsocietywomen.comCorrelation in the 1960s was the death knell of any remaining independence for the Relief Society. It streamlined all aspects of the church into one unified organization held exclusively by the male church hierarchy. The Relief Society was firmly placed under the umbrella of the priesthood. They lost the ability to create their own monthly lessons, all finances went to the control of the bishop, and the Relief Society Magazine was discontinued for the church’s Ensign Magazine. The loss of tangible power was very real. Relief Society continued to focus on compassionate service and aid, but only on an individual and local ward level.

This list of losses goes on:

-In 1978, after blacks were finally given temple and priesthood rights some local leaders started experimenting with more progressive views of women in leadership. The church hierarchy amended the handbook to ensure that everyone understood that women were not to receive further leadership positions.

-When Leonard Arrington (the church historian) wanted to pursue writing a history of the Relief Society, Alice Smith, a member of the Relief Society board, talked him out of it, stating: “This would be too damaging to the testimonies of LDS women who would read it… if it tells the truth, it will relate the deterioration of the power and position of women in the Church and will be very depressing to women who care.”

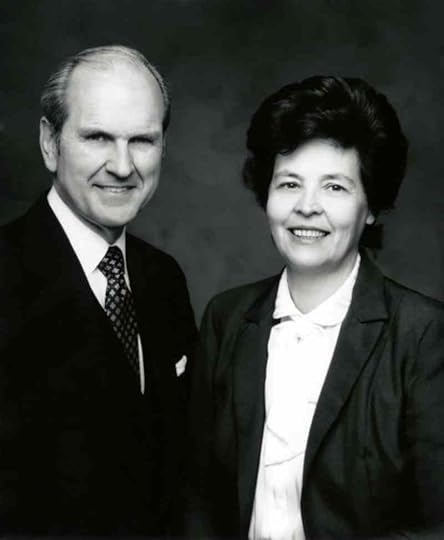

-In 1994, the church released “The Family: A Proclamation to the World.” It was created as part of a legal brief against Hawaii’s case for same-sex marriage and first presented in the Relief Society broadcast of General Conference. However, no women had any say or input in its writing. The Relief Society Presidency hadn’t even heard of it until right before it was announced. Chieko Okazaki, counselor in the presidency, spoke about how they had no say in what went into the document, although it directly concerns women and women’s roles, stating, “as I read it I thought that we could have made a few changes in it.”

The Relief Society Presidency when The Family Proclamation was written and announced in their meeting without their consent or input. Image from Religious Studies Center.

The Relief Society Presidency when The Family Proclamation was written and announced in their meeting without their consent or input. Image from Religious Studies Center.-The tenure of Relief Society presidents changed from lifetime to a 4-5 year tenure. The ever-rotating female leadership means that no woman will ever achieve the same status of importance as Eliza R. Snow or Amy Lyman.

-Relief Society presidencies are not paid, despite working full-time for the church during their tenure. Full-time male general authorities, however, are paid for their work.

-The Relief Society is called a “general auxiliary,” as opposed to a “general authority.”

-From the 1970s to 2013, women held a general meeting every September that was broadcast throughout the world. In 2014, the meeting was changed to include all women ages 8 and up. In 2021, those meetings were removed entirely, and now only occur as the First Presidency directs.

-Women weren’t allowed to pray in General Conference until 2013. Women speakers in conference are still greatly outnumbered by male speakers. Most conferences average only 2-3 women speakers total.

Women on the stand at General Conference. Image from Salt Lake Tribune, standing for the entrance of the prophet and his counselors. (This is already running long, so we don’t have time to go into that wild tradition.)

Women on the stand at General Conference. Image from Salt Lake Tribune, standing for the entrance of the prophet and his counselors. (This is already running long, so we don’t have time to go into that wild tradition.)Today, the Relief Society continues to focus on strengthening its members and serving others. All women over the age of 18 are automatically members of the Relief Society and there are no fees or dues associated with the organization as in the early days. The organization thrives through ministering sisters, compassionate service, and activities. The Relief Society motto is simple and beautiful: Charity Never Faileth.

I appreciate and love my fellow Relief Society sisters. I work towards a safe space for more open and honest dialogue within our Relief Society walls. I do truly believe in the great potential of Relief Society. The things I have seen LDS women organize and do are amazing. The way they always manage to get stuff done, even in the face of patriarchy and roadblocks, is continually inspiring. I know that we are all trying our best and working towards greater unity and influence for good in the world.

But we’ve been duped about our own history. To contemplate all the Relief Society had and how it disappeared, siphoned away by men, breaks my heart. From the beginning, the Relief Society ran under the purview of men, but it functioned with greater autonomy. Women gave blessings and came together to support reform causes and women’s rights. They organized themselves, voted for their leaders, and built their own buildings with their own finances. They cared for the poor, sick, and broader community as a true relief society. And then, they were nothing by a subservient appendage to the men. They lost their financial independence, their mission for reform and aid, and their ability to function with autonomy.

I mourn this loss. I mourn this history of encroaching patriarchy. I mourn for what we had, imperfect as it was, and the scraps we are now offered. We brag that the Relief Society is the oldest female organization in the world. That may be true, but then we’re also the oldest female organization in the world run by men. The Relief Society is a men’s organization for women.

Now in 2025, I see a vibrant, passionate, worldwide organization of sisters. Sisters who want, need, love, cry, support, and struggle. I see sisters living beneath their privileges. I see a woman’s organization under the complete control of men that’s lost its roots. I see a diverse organization that could be an empowered force for greater good in the world, but its chained to men with small minds and a small God.

Our Heavenly Mother must weep for us. Emma, Emmeline, Amy, and many more women didn’t run so we could lie down and accept table scraps. They lived in a different time, under the thumb of a patriarchal society. We live in a world where we can in so many more ways break free of that oppression.

I want more for LDS women. We deserve more. We’re kept from the truth because many of us don’t know where to find it. We must fight back for what is rightfully ours. We need to leave the comments on IG when they try to gaslight us. We should speak up in meetings when false narratives are perpetuated. We could use our collective power to demand more from the male leadership. We can reclaim our right to give healing blessings and prepare the sacrament, to operate independently, and to reform society through group action.

Heavenly Mother is cheering us on, now, forever, and always.

March 18, 2025

From the Backlist: Mormon Feminists Respond to Church Leaders Summoning Valerie and Nathan Hamaker for Excommunication

Yesterday, Exponent II bloggers discussed thoughts and feelings in response to Church authorities summoning Valerie and Nathan Hamaker to a Church disciplinary court with the intention to excommunicate them. The Hamakers considered this Church discipline “exploitative and spiritually abusive” and chose to resign their membership instead of attending the disciplinary court.

Linda Hamilton:

I’m really struggling with this news. Valerie’s work has helped me personally so much and helped me feel comfortable staying in the church. Listening to their podcast announcement it’s clear this was a failure of male leadership and an obsession with hierarchy. I’m honestly disgusted.

Candice Wendt:

I’m feeling a lot of grief about this today too. Valerie’s voice helped me understand and reframe my faith transition and understand what a positive thing it was. Also gave me confidence to reject certain things I used to believe in that harmed me, and to appreciate how interfaith perspectives could strengthen my spirituality instead of threaten it. I love how Valerie and Nathan do episodes together and include both of their perspectives, with Valerie taking the lead. I found it very painful to listen to part of their new episode about what happened. It’s hard to believe any sound-minded leader could read the testimonials they gathered from people who stayed in the Church thanks to their support and still pursue excommunication. I’m especially struck by how much the Hamakers have done to heal family relationships among members through helping us mature and face our fears, love unconditionally, and appreciate rather than be fearful of ways loved ones are different from us. I see this as their greatest achievement.

Listening to this same episode, “Not Willing to be Burned at the Stake Center,” left me with a strong sense of something we’ve mentioned on the blog before: we’re not actually struggling. We’re developing and growing. It’s the institution that is broken, wounded and struggling. It bothers me when members refer to their own doubts and such like “an issue of blood,” like a disease or personal flaw. The doubts and irritations and concerns are because things with the church are awry and messed up, not because these poor members are unhealthy spiritually or otherwise.

Nancy Ross:

It is the institution that is broken. This is something we’ve known for a long time in Mormon feminist spaces. The work we do to help people make their own choices (including stay) is pathologized and then we’re accused of not having enough faith in the men who harmed us. It is a pattern that keeps repeating. Holding a church court was supposed to scare people away from the Hamakers. Certainly, threatening church courts and excommunicating people was an effective strategy in the past. But in the present? It just kinda makes LDS Church leaders look like the big dicks (the bad kind) that they are.

And we really wanted them to be decent people and for church to be a reasonable place.

Kara Stevenson:

I am heartbroken and so devastated. Valerie helped me so much and gave me positive guidance when I had none. The way they were treated sends the message to anyone who is nuanced that they are not welcome.

The institution cares far more about conformity than about healthy individual spirituality. I can imagine a church where everyone is welcome and free to express their beliefs in a safe and respectful environment. But unfortunately that doesn’t exist. Keeping the status quo matters more.

Candice Wendt:

Excommunications of public voices never inspire faith, righteousness, unity, or any fruits of the spirit. They foster fear, distrust, control, separators, disbelonging, and grief.

Maybe some excommunications have scared some people to hiding things or doing things in public more in line with leaders’ preferences, but even if this is happening, it’s not a healthy or desirable outcome. It’s just control and suppression.

It’s an exercise of arbitrary authority in many ways: members are subject to leadership roulette, the presiding leader at Church court meetings has way too much power and basically serves as both jury and judge–even if they appeal the decisions, members are still just at the mercy of what usually very biased leaders decide without having proper recourse options, representation, or advocacy options.

Valerie and Nathan being forced to give up their membership is just another incident in which the Church’s administrators are choosing to drive a wedge between themselves and me. I used to think they were well-intended and cared about members. Events like this communicate to me that they obviously care much more about dogma and retaining authority and traditions than members’ growth and well-being or the truth. The fact this can happen so easily and haphazardly is just evidence to me that the institution is deeply broken and that my membership is not actually truly safe if I choose to share openly and honestly about the problems and corruption I see.

Nancy Ross:

Candice wrote “Excommunications of public voices never inspire faith, righteousness, unity, or any fruits of the spirit. They foster fear, distrust, control, separators, disbelonging, and grief.”

LDS Church leaders know this and know that such actions produce a kind of fear that they can turn into real power for themselves. It is gross.

Beelee:

I was blinking back tears as I read the statements.

It doesn’t hurt because I expected anything else from the leadership. They did exactly what I would have expected. I am not in any way shocked that at whatever level this decision was made, someone decided that Valerie and Nathan don’t belong and that people like them don’t belong. That’s par for the course as well. I expect nothing from the institutional church, so they delivered yet again.

What hurts about this one is I look at the long line of people who have had to sacrifice their church for their integrity to do the right thing and I wonder when it will end, how it can end. How many good people genuinely trying to help and make the church inclusive will it take for the church to actually do better? It’s the same cycle over and over again.

I look at this as one more senseless “spiritual death” inflicted by a church that could choose to lay down their weapons, but never, ever do. A church that has every reason to build peace, but always chooses this instead.

Mic drop Candice: “we’re not actually struggling. We’re developing and growing. It’s the institution that is broken, wounded and struggling.”

Anonymous Blogger:

My blogging has stressed out my parents. I heard through the grapevine they were scared of me getting excommunicated. I tried to reassure my family I wasn’t scared of that. But when I look at Valerie and Nathan, part of me knows that I’m exactly the kind of person that the Church considers optimal and ideal to be rid of even if they aren’t going to bother. This doesn’t feel good. But at the same time, I’ve gotten comfortable and am finding joy in being an independent voice and thinker, and like Valerie, I know our writing here helps many people with all kinds of areas of their lives. Being different and dealing with the discomfort of not belonging fully anymore are proving great ways for me to develop myself during the intense transitions of mid-life spiritual growth. I care so much more about my growth and my personal spiritual practices and experiences than I do about my technical status in relation to the Church at this point. I have already partly detached from my membership in favor of the pursuit of truth and well-being.

Melissa Tyler:

As I was listening to Val and Nathan’s recent podcast (not finished yet), I was thinking of the first excommunications in our church’s history. They are so asinine…ego trips of Joseph’s…ways to assert authority over another…nothing to do with following Christ and re-aligning with God.

To say it more precisely- Excommunication, at least from the beginning of our church’s history, has always been about establishing power.

The “courts” have nothing to do with justice, but with humiliation. A forced humbling of those seeking to do right.

Val has helped me as well. I have a healthy relationship with my family members who are active because of her work.

Linda Hamilton:

I keep wondering, who’s next? The other blogs or podcasts that sit in nuanced space and bring me so much peace? My feminist friends? Me? The concept of excommunication is one created by humans not Jesus. He calls ALL to come into Him. His ministry was to sit with the marginalized and outcast.

It’s also discouraging to listen to their story and realize we have a chain of men in church leadership that are each more scared of offending the man above them than to step out and help the one like Christ would. It sounds like a group of Pharisees that are too busy enforcing exactness on each other and their people to care for individuals. I highly doubt Jesus would approve. It seems to me the church worships hierarchy and power much more than God.

The feature image comes from https://valeriehamaker.com/

The Very Elect Shall be Deceived. But Maybe Not in the Way That We Think

Today is a day of sadness. The church has lost two of its best and brightest. Valerie and Nathan Hamaker from the Latter-day Struggles Podcast have formally resigned from the church, not because they wanted to, but because they refused to face excommunication.

Everyone should listen to their newest podcast episode “Not Willing to be Burned at the Stake Center” to understand the ordeal they have been through, and to see how terribly misunderstood they have been.

Their content has been instrumental in my own healing journey, and I know they have had an immense positive impact on so many in the church.

To Valerie and Nathan, we here at Exponent II stand with you.

I mourn the message that this sends to nuanced members all across the church; you are not welcome here. Your beliefs, your hopes, your dreams of contributing to an inclusive and love filled church do not belong here. If you do not conform, you will not find a place here. If you speak out too loudly, you’ll either be excommunicated or forced to resign.

And this breaks my heart.

I’d like to remind everyone of the story of the blind man who received the gift of sight from the Savior. The leaders of his own religion asked him repeatedly how this miracle occurred. When he told them, they didn’t believe him. Perhaps it was too threatening to their prescribed religion, or maybe it was too difficult for them to understand.

In the end, the man refused to deny the truth of what happened, and his leaders cast him out. It is my understanding that this would have lead to serious social consequences for this man; a man who stood with integrity and honesty in the face of severe punishment from the hands of his ecclesiastical leaders.

In the wake of his apparent excommunication, who was there for him? The Savior Himself.

You see, He didn’t stand beside the leaders of his day, condoning the disfellowships and the excommunications

Jesus Christ stood with the outcast, the downtrodden, the isolated and the afraid. He even embraced them.

We perceive the saying “even the very elect shall be deceived” to mean that even the most faithful among us will leave the church, finding themselves deceived by anti-Mormons or by Satan himself.

The Hamakers leaving is proof that the very elect are leaving the church, but not in the way that we assume.

They are not leaving because they have been deceived; they are leaving because the perceived “elect” among us, those who hold power and authority both locally and generally, are the ones who have been deceived.

They have been deceived by the false belief that conformity is mandatory in the church.

They have been deceived by the notion that defending the church is more important than loving those who may believe differently.

They have been deceived by their own fears; convinced that those who think differently must be silenced and cast aside.

They have been deceived by pharisaical traits that encourage the exclusion and excommunication of their own people; an action that Jesus opposed.

So yes, perhaps the very elect shall be deceived. But maybe not in the way that we think.

Maybe lacking institutional conformity isn’t a legitimate marker for a person’s righteousness, faithfulness, goodness, or spirituality.

Maybe leaving the church doesn’t mean you are lost and have gone astray.

But perhaps excluding those who think and believe differently from you, and casting them from your midst, is an action done by those who have lost their way.

To the leaders of the church who abuse their power and who refuse to hear the very real spiritual experiences of others, maybe it’s time to consider that the “very elect being deceived” might just be referring to you.

Author’s Note:

It felt odd to find myself feeling such emotion over this news. I had thought that maybe I was the only one to be feeling such heaviness drag myself down throughout the course of the day. But I quickly learned, as fellow bloggers emailed one another and as the comments came through on social media, that I was not alone.

We are not alone.

It may feel isolating at times to find ourselves standing alone in our congregations or even within our own families. Moments like this remind us that we do have a community out there, even if we can’t always see it in our day to day lives.

This may be the greatest thing that the Hamakers have accomplished: bringing like-minded souls together.

Maybe something good can be salvaged from all of this. The outpouring of love from supporters has been heartwarming to witness. I have also appreciated the comments that remind us of the amazing Christlike example that the Hamakers have shown. They have actively chosen to forgive, empathize with, and extend love to those who have wronged them.

The Hamakers have also chosen to not let this shake their resolve. They remain committed to fulfilling their mission of offering wisdom, love, and support to those who find themselves along the fringes of the Latter-day Saint community.

As someone who has found themselves among this crowd, I owe a great deal of thanks to the Hamakers. Valerie’s words assured me that there was nothing wrong with me, even though the church’s negative rhetoric toward those who stray had overwhelmed my mind for months. She assured me that I was growing, and that I was right on track with where I needed to be. She gave me hope and a light at the end of the tunnel when all I saw was darkness.

Their work has literally saved lives. I’m certain that this work will continue to roll forth and impact the lives of many more to come, as the stone cut out of the mountain without hands, if you will.

A few men who feign power and deign to abuse it will never be able to stop it.

And they won’t be able to stop all of us from uniting and growing along our own personal spiritual journeys.

I’m saddened that the Hamakers had to be the collateral damage, but I am grateful for their example, their bravery, and their unwavering commitment to integrity and truth.

This event did not break them. So we will not let it break us.

This will not weaken us or drag us down. It will do more to bring us together with purpose and renewed resolve than ever before.

Yesterday felt like a loss, but today feels like a new day. Let’s make it a good one.

March 17, 2025

Apostles’ Wives Aren’t Allowed in the Meeting When Their Husband is Called

There’s a troubling pattern I accidentally stumbled across while reading stories of LDS apostles being extended (and accepting) their callings into the Quorum of the Twelve. I was unable to find a single incident where the wife of the man being called was included in the process. In every story I read, the wife was not asked her opinion, she was purposefully excluded from the meeting where the calling was extended, and she was only informed of the calling after it had already been accepted by her spouse.

This is unexpected, because husbands and wives are routinely brought in for callings of a much smaller scale, such as temporary ward and stake positions. The calling to be an apostle only ends upon the man’s death, and it will impact his wife significantly more than a five- or ten-year stint as wife of the bishop or stake president will.

This isn’t an occasional occurrence or something that used to happen in the past – details of Patrick Kearon’s call just last year include telling his wife only after he’d accepted the call from President Nelson.

Is it really such a given to the men in leadership that their wives will accept whatever life altering calling they’re given so much that they don’t even invite the women into the room? As you’ll see in the examples to follow, even when the wife travels from out of state with her husband for the meeting, they make her wait elsewhere alone.

For a grandmother looking forward to retirement and spending her golden years with grandchildren, going on cruises, relaxing at home, maybe serving a mission or two for the church and staying out of the limelight – having her husband called as an apostle changes every part of her life forever. I’m aware these women are highly unlikely to object to their husbands taking on this mutual lifetime commitment – but is it policy to not even ask them?

Here are some of the stories I found. They’re all terrible. Enjoy!

Elder David A. Bednar and his wife Susan Image from East Idaho News

Image from East Idaho NewsElder Bednar accepted the calling to the Quorum of the Twelve without Susan present. President Hinckley requested to meet with him (and only him) in September of 2004. The couple drove to Salt Lake City from Rexburg, Idaho together and Susan waited in the Joseph Smith Memorial Building nearby while he went to meet with the prophet. It wasn’t like she wasn’t available to be in the meeting. She’d traveled from out of state to be there and was still excluded.

“We visited for an hour and he extended the call to serve,” Elder Bednar remembers. “He asked how I felt, and I said, ‘President Hinckley, I’m stunned.’ He said, ‘Good, you should be.’”

After accepting the calling, David Bednar walked over and broke the news to Susan. On the drive there they’d guessed it would be a release from his position as president of BYUI after eight years. Neither were expecting the call he’d received. She wanted badly to tell their sons, so they could be in attendance at the general conference announcement the next morning.

“I said, ‘Surely we can tell our sons. This is the most important day of your whole life,’” Susan told Elder Bednar.

“I kept asking and he kept saying no,” Susan says with a smile. “Finally I asked him one more time and he looked at me and said, ‘Martin!’”

Elder Bednar was referring to Martin Harris, of course – who asked repeatedly for something from the prophet Joseph Smith after being told no and caused all kinds of problems in church history.

I hate that Susan Bednar was not even invited to the meeting where the outlook for the rest of her entire life was changed, but then was called “Martin” condescendingly by her husband for wanting to share the news a few hours early with their own children. I also hate that they tell it like a cute joke rather than the total disregard for her feelings that it was.

(Details in this Idaho news story.)

Elder Dale G. Renlund and his wife Ruth

Ruth was also excluded from her husband’s calling to be apostle in 2015. Nothing had changed in the decade since Bednar was called.

Out of the blue one day, Elder Renlund received a call from the Office of the First Presidency and was asked to come to the North Board Room in the Church Administration Building. “I didn’t know where the North Board Room was,” he laughed. He was welcomed there by President Thomas S. Monson and his two counselors. What followed was a very brief meeting in which President Monson said, “Brother Renlund, we extend to you the call to serve as a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.”

After accepting the call, he then reached out to his wife and gave her the news.

(Details at the Church Newsroom.)

Elder Patrick Kearon and his wife Jennifer:

Nothing changed in the process with the newest apostle called last year. This is from journalist Peggy Fletcher Stack in the Salt Lake Tribune:

“Imagine being unexpectedly summoned by your boss for what you believe is a routine check-in about your work and he asks you to commit immediately to the job – until you die.

That was exactly what happened in December to Patrick Kearon, an adult British convert to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. On an average Thursday, Kearon, who was serving as a full-time general authority for the faith, got a call to meet church President Russell M. Nelson “within seven to ten minutes.’

The modest leader had no idea what was coming, so it was “deeply shocking,” Kearon told The Salt Lake Tribune in an interview Tuesday, when the 99-year-old Nelson asked him to join the faith’s Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, the second top tier – after the three-member First Presidency – in the 17 million-member church.

It is a lifetime position.

And, as the church’s prophet-president, Nelson expected an immediate answer.

“I actually gave him some other names,” Kearon recalled. “You just don’t see yourself in…that role.” But Nelson assured the convert that the “call didn’t come from him but from God. And so he – gulp – said yes.

There was no time to consider how his future had just been upended or confer with his wife, Jennifer.

By that afternoon, 62-year-old Kearon was ordained by Nelson and others in the top quorums. “It’s a humdinger of an adjustment,” Kearon said.”

But what about Jennifer? Was it an adjustment for her, too?

President Russell M. Nelson and his first wife, Dantzel:

President Nelson was attending a regional representatives seminar in 1984 when he was tapped on the shoulder and told that President Hinckley, second counselor in the First Presidency, wanted to meet with him.

President Hickley asked him “if everything in his life was in order.”

“Yes,” President Nelson said. “Good!” President Hinckley said. “Tomorrow we will sustain you as a new member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles!”

President Nelson was stunned, but he accepted. After discussing some dilemmas in regards to his professional commitments, President Hinckley suggested he excuse himself from the seminar and go home to share the news with his wife, Dantzel, which he did. (President Nelson was more wrapped up worrying about how his work would be affected than telling his wife.)

From his biography:

“Russell M. Nelson: Father, Surgeon, Apostle,” by Spencer J. Condie.

In 1984 Utah resident President Oaks was out of town on judicial business in Tuscon, Arizona the Friday night before General Conference. While eating dinner at a Mexican restaurant with colleagues, President Hinckley called the establishment and spoke to him over the noise of a mariachi band. President Hinckley asked him to call him back when he was in the privacy of his hotel room later, which he did. At that time, he was extended the calling to the apostleship over the phone.

Following this exchange, he was given permission to call his wife June and let her know what was happening.

I’m not clear why permission was needed to inform someone of a lifelong calling she is also being asked to undertake. Was the other idea to surprise her during conference to see if she was paying attention?

From his biography:

In the Hands of the Lord: The Life of Dallin H. Oaks, by Richard E. Turley, Jr.

In 1995 President Eyring was called to the office of President Gordon B. Hinckley, who began by asking him about his service as commissioner of education. This launched a 30-minute conversation about challenges facing the church educational system.

At the end of this discussion, “President Hinckley concluded that Hal could continue to play that role and take on an additional assignment. Making reference to the vacancy to be filled the next day, he said, ‘Well, I think we’ll have you continue as commissioner as you join the Twelve.’”.

President Eyring returned to his office and immediately began working on the general conference talk he would deliver the next day after being sustained as a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. He titled it, “Always Remember Him.”

There’s no mention of his wife Kathleen in his story at all. (I guess he told her when he got home from work that day?)

From his biography:

“I Will Lead You Along: The Life of Henry B. Eyring,” by Henry J. Eyring and Robert I. Eaton.

Elder Holland was called to meet with President Howard W. Hunter on a random Thursday morning at 7:30 am in 1994.

In his general conference address, “Miracles of the Restoration”, Elder Holland explains being called and ordained within a matter of hours, with absolutely no mention of his wife’s involvement at any point:

“In a rapid sequence of events that Thursday morning, President Hunter interviewed me at length, extended to me my call, formally introduced me to the First Presidency and the Twelve gathered in their temple meeting, gave me my apostolic charge and outline of duties, ordained me an apostle, set me apart as a member of the Quorum of the Twelve, added a magnificent and beautiful personal blessing of considerable length, then went on to conduct the sacred business of that first of my temple meetings, lasting another two or three hours!” Elder Holland said.”

Their son Matt Holland did say once, “My mother gives her full, unreserved allegiance to my father’s priesthood leadership”. It doesn’t sound like he would have felt it necessary to ask for her support.

In 2009, he was surprised by a phone call instructing him to go straight to President Monson’s office, where he was called to be an apostle. He speaks highly of that experience with President Monson in his April 2009 general conference talk, “Come Unto Him”, but he never mentions his wife. She wasn’t in the room, only those two men were.

******

I can’t tell the stories of every apostle ever called – partly because this would get too long, and partly because I haven’t been able to find all of their stories. But in all of my reading, I have not been able to find a single incident that ruins my hypothesis that wives are purposefully not invited to the meetings where callings for apostles are extended and accepted. This is not okay. Why is the calling of apostle so sacred to top priesthood leaders that the women most affected by it aren’t allowed in the room when it happens?

March 16, 2025

Why Women Leave the Church

My Area President asked why it’s now more common for a wife to leave the church before her husband. This was my response.

Why are women leaving the church and taking their families with them? The short answer is that women within the church are not treated as fully capable human beings. The sons of God lead and direct the church, but the daughters of God find that their spiritual authority is not valued within church walls. Many daughters of God have tried (and failed) to change this, but women lack the necessary institutional authority. Women and gender minorities are currently dependent on men in leadership positions to modify the structure of church administration so that the spiritual authority of every child of God can be honored.

What do I mean when I say women’s spiritual authority is not valued? Women’s talks make up a minuscule percentage of speaking time at General Conference. Women who speak at stake and regional conferences are often married to a man in a leadership position. They are given a voice not because of their gift for spiritual insight, but because of their relationship to a man in power. Women’s stories, whether from the scriptures or church history, are left out of church curriculum.

The hardest day I’ve ever had at church wasn’t because of anything outrageous anybody said or did. The talks all covered familiar ground. A sister missionary talked about prophets in the Old Testament. I wondered if she had ever heard the stories in the bible that tell about female prophets. Later, the visiting seventy told us how all the general authorities and female officers of the church sustain President Nelson as the prophet, seer, and revelator. His words made it clear to me that he did not understand that women also have the spiritual capacity to act as prophets, seers, and revelators. Women have deep relationships with God; they too are God’s children. Women are capable of communicating their God-given knowledge to those around them. They have done so since ancient times. A church that values women’s spiritual authority would also grant women institutional authority, so that the church can be led by women with godly insight.

In the last decade or so it has become much easier for women to see that they lack any institutional authority. Eight-year-old girls saw that men had the final words at Women’s Sessions of conference. The online handbook makes it easy to verify that men have the final say in everything that happens within the church. Men control the budget. Men control the curriculum. Men judge a woman’s temple worthiness by how she wears her underwear (men approved the sewing patterns). Men decide which women get to be leaders, although women do not actually lead any church organizations. A woman can be ‘president’ in name only—there is always a man who presides over the organization. If a female leader has a great idea, there’s always a man with authority who can prevent her from implementing her idea. So women learn to censor themselves. They learn to act in ways they believe will be acceptable to the men in charge. Or they get tired and angry at the necessity of making their goddess-in-embryo selves small, and they leave.

I’m going to make an analogy. Let’s say a husband controlled all the money within a marriage. He controls the media his wife uses. He decides how and what she will teach their children. He decides what the wife can and cannot wear. He makes all the final decisions about what the family will do and how they will do it. This is not a marriage of equals. The husband is abusing his wife, even if he has never physically harmed her. He is limiting her agency to act and make decisions with her own judgment. It can be difficult for a woman in this kind of situation to recognize it as abuse, especially if this behavior is normalized within her surrounding culture. A woman who understands her situation will work to change her situation. If her efforts to change behaviors within the marriage end up failing, she would want to leave the marriage as soon as she can find a safe way to do so. This can be incredibly challenging, especially for an unemployed woman who was taught that her greatest calling in life was to stay home and take care of the children.

Women who leave the church often see parallels between the way the church treats women and how an abusive husband may treat his wife. I’ve heard stories of women who leave the church, not for themselves, but for their daughters. They want their daughters to learn to think and act with their own wisdom and agency. I’ve heard stories of women who leave the church because they don’t want their sons to perpetuate harmful ways the church treats women. Women leave the church because the lives of their LGBTQIA+ loved ones are at stake. When a wife struggles with the church, the husband is affected as well. A husband who sees and understands his wife’s pain may try to fix her problems using whatever influence he has in his ward and stake, but the vast majority of men are powerless to change patterns of church administration. Men in leadership positions can do many things to champion the talents of the women under his stewardship. However, not even a Stake President has the institutional authority to make the changes necessary for women’s spiritual authority to be placed on par with that of men. It is hard to stay involved with an institution that you feel causes more harm than good and that you are powerless to change.

I know church leaders are concerned and care about the women and families who leave the church. Most of the people I know who have left did not want to leave. They wanted to make the church better and safer and more empowering and more inclusive and more loving. But they couldn’t. They didn’t have a way to make the voice of their spiritual authority heard. Second Nephi 26 teaches that all are alike unto God: Jew and Gentile, black and white, bond and free, male and female. God spoke to Joseph Smith when he was a young, inexperienced boy. God can speak to all of His children. Church ought to be a place where all “are privileged one like unto the other”. We don’t currently have that church. Systemic changes are required. Only those in the highest levels of church administration can make the changes that will enable all children of God to fully use their talents to benefit the welfare of Zion.

Bloggers had a great discussion of this Area President’s question. You can read highlights here.

March 15, 2025

I’m Cutting Out the Middleman to God

The day you walk into a Bishop’s office and the man sitting across from you is your peer is a bit disorienting. As a child, teen, or even young adult, age held a certain sway over me. It indicated authority and wisdom. I wasn’t used to being alone/allowed to be alone with men, so I felt the power imbalance acutely. Generally, these men had one role in my life that matched their church title, immediately giving them authority and intimidating me.

Fast forward a few years and a shift began as I walked into that office. These men are my peers, dudes I play games with, men who spout political nonsense, husbands wives complain about or praise, best friends of my husband, okay guys, pretty great guys, and sometimes even men I wouldn’t associate with if we didn’t have church in common.

Even men who are still my seniors, who would be my Dad’s age, appear more human to me. They are businessmen in the community – sometimes famously ruthless ones, lawyers, painters, my friend’s amazing dads and overbearing father-in-laws, local politicians, and my old schoolteachers. Some of them are even famous for their “We couldn’t believe he was called to be Bishop because he drank and smoked and… and then being Bishop changed him and now we hang on every word he says as if it’s straight from God’s lips.”

I’m obviously being a bit tongue-in-cheek here, but I remember looking at them and thinking, “They are just men.” Yet, I’d allowed their judgment, their limitations, their sexism, and patronizing to gatekeep my relationship with God for far too long. All the things I truly valued about my faith told me that God could and would speak directly to me. I knew that God gave me a conscience to guide me and a passionate desire to good. My heart told me that these middlemen, who kept trying to humble, settle, break, and reprimand me weren’t speaking for God.

I don’t need a middleman. God doesn’t need a middleman. These men need to be middlemen to feel important, worthy, and purposeful. But it is no longer my job to provide that for them. God doesn’t need me to continue waiting for men to be ready; for their fragility to become strength; for their weakness to be buoyed by leading/controlling me.

This does not mean that I’m always right or that God never says anything I don’t want to hear. It certainly does not mean my life goes exactly as I plan. But it does mean I can begin to let go of the hurt and shame these men heaped upon me when I trusted them repeatedly, with a wild, restless hope, even as the curtains began to fall away and reveal the truth of who they were and what little they could offer.

March 14, 2025

Apply for our BIPOC Artist Scholarship!

*Art by Rocio Vasquez Cisneros, 2022 BIPOC Scholarship recipient and current Exponent II Magazine Art Editor.

What is the mission of this scholarship?We wish to amplify the voices of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) artists and writers in the LDS community by lending needed support to continue developing their work. Applicants should identify with the mission of Exponent II. This scholarship is for women and gender-minority artists and writers along the LDS/Mormon spectrum and community. Citizenship status does not affect eligibility to apply.

How can I apply for the scholarship?Please fill out this survey , where we will ask:

Your name, contact information, and confirmation that you align with the award identitiesA brief cover letter (around 500 words) about how you will use this scholarship to support your work and the amount of money you are requesting (see below for award amounts) Attach examples of your work through pictures of your art or relevant links to your portfolio (website, Instagram, etc.).Fill out the survey and upload materials by April 15, 2025. Recipients will be announced on May 23, 2025, and will be featured or promoted in a future magazine issue. We look forward to seeing the art the scholarship helped produce.

Note: Priority will be given to applicants who have not won an Exponent scholarship in the past.

Is there an age requirement?Applicants should be at least 18 years old.

What can the money be used for?We want these funds to meet artists and writers wherever they are in their careers. The money can be used for professional development, education, art supplies, childcare, or to compensate you for your time creating. The goal is simply to help artists of color work successfully in the artistic world.

How much money is available?Most awards will be $200-$500 per award. We are accepting applications requesting additional funds depending on the scope of the project. Please specify in your application how much you are requesting. We currently have $2,500 in total to award. Many thanks to past contributors who generously donated their stipend to this BIPOC artist and writer community fund, as well as other generous donors who support this work. If you would like to donate or know of others who are able to contribute, follow this link and note that the donation is for the BIPOC Artist & Writer Scholarship.

Who decides how the money will be distributed?A big thanks to Rocio Vasquez Cisneros, our Exponent II Art Editor, who will be a panelist and is gathering additional BIPOC panelists who will review this year’s applications.

Past Scholarship Award Recipients Include:

2019

Elizabeth SanchezK DawnKwani Povi WinderEsther CandariMarlena WildingHanna ChoiGifty Annan-MensahKaryn DudleydeTiare Leifi2022

Marlene WildingCrystal PowellRocio Vasquez CisnerosPahola Alejandra RamosSiwa AllredSusana I. SilvaQuestions?Email Rocio Vasquez Cisneros at art@exponentii.org.

BIPOC Artist Scholarship Application

*Art by Rocio Vasquez Cisneros, 2022 BIPOC Scholarship recipient and current Exponent II Magazine Art Editor.

What is the mission of this scholarship?We wish to amplify the voices of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) artists and writers in the LDS community by lending needed support to continue developing their work. Applicants should identify with the mission of Exponent II. This scholarship is for women and gender-minority artists and writers along the LDS/Mormon spectrum and community. Citizenship status does not affect eligibility to apply.

How can I apply for the scholarship?Please fill out this survey , where we will ask:

Your name, contact information, and confirmation that you align with the award identitiesA brief cover letter (around 500 words) about how you will use this scholarship to support your work and the amount of money you are requesting (see below for award amounts) Attach examples of your work through pictures of your art or relevant links to your portfolio (website, Instagram, etc.).Fill out the survey and upload materials by April 15, 2025. Recipients will be announced on May 23, 2025, and will be featured or promoted in a future magazine issue. We look forward to seeing the art the scholarship helped produce.

Note: Priority will be given to applicants who have not won an Exponent scholarship in the past.

Is there an age requirement?Applicants should be at least 18 years old.

What can the money be used for?We want these funds to meet artists and writers wherever they are in their careers. The money can be used for professional development, education, art supplies, childcare, or to compensate you for your time creating. The goal is simply to help artists of color work successfully in the artistic world.

How much money is available?Most awards will be $200-$500 per award. We are accepting applications requesting additional funds depending on the scope of the project. Please specify in your application how much you are requesting. We currently have $2,500 in total to award. Many thanks to past contributors who generously donated their stipend to this BIPOC artist and writer community fund, as well as other generous donors who support this work. If you would like to donate or know of others who are able to contribute, follow this link and note that the donation is for the BIPOC Artist & Writer Scholarship.

Who decides how the money will be distributed?A big thanks to Rocio Vasquez Cisneros, our Exponent II Art Editor, who will be a panelist and is gathering additional BIPOC panelists who will review this year’s applications.

Past Scholarship Award Recipients Include:

2019

Elizabeth SanchezK DawnKwani Povi WinderEsther CandariMarlena WildingHanna ChoiGifty Annan-MensahKaryn DudleydeTiare Leifi2022

Marlene WildingCrystal PowellRocio Vasquez CisnerosPahola Alejandra RamosSiwa AllredSusana I. SilvaQuestions?Contact art at exponentii.org