Exponent II's Blog

November 30, 2025

Guest Post: Disabilities at Church: Part Two

November 30, 2025 Guest Post

November 30, 2025 Guest PostGuest Post by Calleen Petersen

This is Part Two in a two part series. Part One was published yesterday.

Photo by Steven HWG on Unsplash

Photo by Steven HWG on UnsplashDid you know that the largest minority in the U.S. is the disabled? 1 in 4 Americans are disabled. Did you know that it is very likely that at some point in your life, you will join this group? Age, my friends, it’s not kind to any of us. And we struggle as a church to meet the needs of the disabled in our church community.

About a year ago, a family moved into our ward with children who experience autism that was more severe than our ward was used to. They struggled to know what to do. They reached out to the stake, with no result. Online resources didn’t help either. It made me think about how we need to make changes within our operations in church to make it accommodating to those who have all types of disabilities.

I posted on Facebook about a couple ideas I had. One was simply having mics brought to the members for fast and testimony meetings, like they used to in many wards. Some still offer them, but most don’t. A former member of a bishopric replied to my post that we shouldn’t do that. The person could just ask the member of the bishopric to have one that specific Sunday if it was really needed, and it could be provided then. I disagree, and here is why-

The person with a disability must ask for accommodation every single time. The person may be embarrassed about needing it, it makes them feel singled out and the odd person. Providing a mic that can be brought to everyone in the congregation normalizes it. Often, other people benefit in unexpected ways when we make accommodations for those who are disabled. That sister with severe anxiety, or phobia of speaking in public? She is more likely to bare her testimony because she can stay where she is and stare at the floor. That mother with small children whose husband is in the bishopric. She’s more likely to bare her testimony because she doesn’t have to leave her children. That terrified teen who is considering it for the first time? Breaking down barriers and making it easier benefits us all.

Once I got started, more ideas kept coming. Here’s a few more I feel should be standard in all wards and stakes.

Instead of an optional disabilities specialist, there should be disability specialists called in every ward and stake. In wards, multiple should be called as needed to work with specific people and auxiliaries, with a main person to oversee them at ward and stake levels. They should sit on ward and stake councils, informing the council of specific needs and changes that should be considered for local culture and policies. If we are not in the room where decisions are made, we are not heard or seen. The family in our ward with two kids with more severe autism? Disability specialists were eventually called. They work specifically with each child to help them regulate and participate while giving them breaks as needed so teachers can still teach, and their classmates understand that these children are wanted and valued, are not scary, and can develop love and friendship. It is beautiful to see.

A sensory room should be in every church building. A place where big feelings and big movements are okay and accepted. Growing up, there was an old church building that had a cry room at the back with one-way glass and the audio piped in. Parents could take their autistic, ADHD, or sometimes just wild kids to the room and not disturb others, and still be part of the service. It was amazing. I’ve never seen it in another one of our buildings. This should not be a room where parents are told to take their child by others, because their child is loud or misbehaving, but rather a space where they can go if THEY feel it would be beneficial. It should be open to the whole ward, normalizing this isn’t just where the “strange kids” go, and gladly welcome them back to sacrament, no matter how loud or disruptive they are.

We also have several young women in our ward with autism and other issues. I notice, they struggle to connect with what is going on in their class, feel a part of the group, and subsequently struggle to go to church because the church members are not meeting them where they are at. What about a class for these girls? Not to exclude them from the main group, but a class catered to their needs with a few other girls that cycle in and out every 6 months. Maybe it’s more basic gospel doctrine, helping in the nursery, or something more dynamic with lots of movement, games, and music, because that’s what they need. The messaging being, we see you, we know who YOU are, and we love you.

COVID made accessing church more accessible for some due to broadcasted sacrament meetings. This needs to be common practice with the links readily available. This enables those who are sick or disabled, or maybe those with a job on Sunday, but they have a free hour, to still participate. But we must be careful, is this the only interaction these members get with the church? Do they have active ministering brothers and sisters who regularly visit them and check on their needs? If my experience in 9 different wards across the nation is any indication, they likely do not.

All wards should have devices for the hearing impaired. Especially for Sunday school type meetings in which you have a teacher or speaker and comments by the congregation, in the chapel. Mics should always be used. None of us likes to use them, and think we talk loud enough for everyone to hear. Newsflash. Even those who aren’t hard of hearing are struggling to hear you, but don’t feel comfortable speaking up. This alienates people from the discussions going on, making them feel like they have nothing to contribute.

Many wards have spouses who care for an ailing spouse or parents who care for a child who medically, emotionally, or behaviorally is hard to care for. These members need a break. Can someone sit with their spouse or child once a week so they can get their hair done, go out with friends, and just take a break from the person that they love with their whole soul, but need a minute away?

These are families who don’t get invited to other people’s homes. People don’t know how to interact with their children, your home isn’t equipped for a wheelchair, food issues are a problem, etc. etc. Their lives are often very lonely, hard, and they need someone to hold space for them. Let’s get creative. Stay late after church for a shared meal with the family or bring the meal to their house to share (bring paper products so you aren’t creating a mess to clean up later). Arrange for the family to come over, but bring their own snacks, or really spend time understanding their dietary requirements. That will really mean a lot to them if you care enough to create space for them. Don’t know how to interact with their children? Ask questions, start slow, build rapport. It doesn’t have to happen overnight. We can find a way to help these families feel wanted, included, and meet their needs.

These were my thoughts. What are ways you feel we can do better?

Calleen is a mother of an adult with disabilities, a disability advocate, and therapist. She enjoys spending time with friends and curling up with a good book.

Calleen is a mother of an adult with disabilities, a disability advocate, and therapist. She enjoys spending time with friends and curling up with a good book.

November 29, 2025

Guest Post: Disabilities at Church: Part One

November 29, 2025 Guest Post

November 29, 2025 Guest PostGuest Post by Calleen Petersen

This is Part One of a two part series. Part Two will be published tomorrow morning.

Photo by marianne bos on Unsplash

Photo by marianne bos on UnsplashAs a mother of a child who has had physical, mental, behavioral issues, and disabilities, church has been hard for my family through the years. Actually, if I’m being honest, there were times it was downright hell.

Church is hard for many families like ours. We have kids who scream the entire sacrament. Church is not set up for kids who don’t sit quietly and behave. Our children are running up and down the aisles and blurting out inappropriate things. We are getting phone calls and bad reports. People do comment and sometimes say very hurtful things. It can be physically difficult to lug all the equipment our loved one requires just to be there. We are so exhausted from fighting with doctors, insurance companies, schools, spouses, our family member with the disability, and the family members without who don’t understand. We often wonder why we even come.

I remember one Sunday, things had been particularly bad, and someone asked, “How are you?” I know the correct response is “I’m great. How are you?” But those aren’t the words that came out of my mouth. Instead, a word vomit of trauma spewed out. I watched as the eyes of the person I was talking to got big, and unconsciously, their body physically recoiled from me. Bishops, Relief Society presidents, ministering sisters and brothers, often aren’t equipped to handle our level of trauma. They will often leave the conversation immediately and avoid us later.

Another time when my son was very young, a group of mothers in my ward decided that my son was not allowed around their children, and then, by extension, I was ostracized as well, due to behaviors I could not control, and did not yet understand the nature of, as he had not yet been diagnosed. This spread throughout the ward. It took a Bishop calling all the sisters into a room and calling them to repentance for it to stop. I was grateful, and yet heartsick that this had been the reaction of my fellow saints.

Generally, as a church, we are pretty good at showing up for someone who’s died. We make casseroles, we check in on them for a while, but are we as good when someone with mental health problems? What about someone going through a long, protracted, or lifelong illness? Do we still bring over the casseroles? Do we volunteer to help clean or sit with them? Sometimes. Some of our fellow saints are families in crisis due to medical or mental health problems that may never end. Their enduring to the end can be crushing. What are we doing for them? Are we bypassing them because we don’t know what to do or say? Are we saying, “I’ll pray for you and walking away? I believe Jesus calls us to spend time with the one.

When my son was in and out of psych wards for about 5 years, they were the hardest of my life. The experience brought me to my knees in a way nothing else has. We were active. We were at church every Sunday with our son putting on his show of behaviors, and me having to drag him out of the sacrament meeting with him screaming, violently kicking, and hitting me. Yet during that time, we only had two unsolicited offers of help in the 3 wards we lived in. I got help because what I was going through completely broke me, and I had little pride left to get in the way. I would ask, and sometimes beg for it, but usually when I was absolutely desperate. We never had ministering brothers or sisters who came or checked in.

Many of those in crisis are at the end of their rope. Mothers, fathers, spouses stretched beyond the max. But wards often don’t know what to do or recognize that there are any needs.

These parents and spouses struggle with self-care. These parents and spouses suffer from huge anxiety, TONS of grief, which will often hit again and again as their child reaches an age but doesn’t meet a milestone, or spouse faces yet another setback. Depression is rampant, along with feelings of helplessness. An occasional meal, someone who is willing to take the time to truly listen can help. If you are up to it, taking time to spend with the ailing spouse or difficult child so they can get a break can make a HUGE difference.

Children who have special needs siblings? They often feel overlooked, as, through no fault of theirs or their parent, a lot of their parents’ time and attention is focused on the disabled sibling. They need people to be second-parents, grandparents in their lives, people who see, hear, and know them. Including the non-disabled child with your family activities and taking them to church activities can help the child feel included and less like they miss out on everything when their sibling is having a meltdown or medical emergency, and their parent can’t make it, or they don’t have the stamina. A community of people who fill the gap, we can do that.

If I were the Bishopric, Relief Society or Elders Quorum President, after living this life of mine, I would be going down my list of members who are struggling like this, and meeting with them individually to learn of their strengths and needs. I’d have them think of callings, real or imagined (thank you, Susan Himkley from At Last She Said It!) that they might be able, willing, and excited to participate in. Because we need opportunities to be a part of things too. We need opportunities to serve and not feel like we are no longer needed or have anything to give. We need opportunities to minister and be ministered to. If you’re wondering how to help, ask us. We are your best sources of information.

To the many who are suffering in silence.

I see you, and I write today because I’ve been there, and I want to help.

Calleen is the mom to an adult with disabilities, a disability advocate, and therapist. She enjoys spending time with friends and curling up with a good book.

Calleen is the mom to an adult with disabilities, a disability advocate, and therapist. She enjoys spending time with friends and curling up with a good book.

November 28, 2025

The Power of Ritual in Community: The Time Candle Lights Brought Me to Tears

November 28, 2025 Bailey

November 28, 2025 BaileyWatching dozens of candle flames flicker around the altar, I caught my breath and held it in an effort to keep tears from streaming down my cheeks while standing next to my students. It was All Saints and All Souls mass at the Catholic high school where I teach. A part of this mass included remembering those who had died in the past year – grandparents, parents, siblings, and others in some way connected to the school community. Never before had I experienced a community ritual to process grief and loss. My thoughts turned to those I have lost; particularly my brother-in-law as this December marks ten years since his passing.

These dates in the liturgical calendar for All Saints and All Souls – November 1st and 2nd – are solemn days. I am new to teaching in a Catholic school and somewhat new to the liturgical calendar. The experience of gathering in remembrance surprised me in its simultaneous beauty and pain. I wasn’t used to having grief and loss acknowledged in a communal setting. After all, I belong to a church where grief is handled with phrases such as “Think Celestial.” While at times it can be helpful to zoom out to keep a larger perspective in mind, the approach of papering over emotion is not helpful in processing the grief and loss that are a part of life. The healing power of gathering in community to remember saints and souls proved unexpectedly beautiful in its bitter sweetness.

While many cultures throughout the world have rituals for grief and loss, I sadly feel a lack of ritual in my life and church experience. When my brother-in-law unexpectedly died a few days before Christmas, the viewing was held on Christmas Eve and the funeral the day after Christmas and that was that. As I slogged through those days, I wondered while picking up a pizza one night how many people around me were mourning. I did not find American funeral practices helpful. At the time, I didn’t even have the language to identify my feelings as grief and loss. I learned that years from a friend who was in graduate school to make a career change to be a therapist. Later I learned the value of rituals from my own therapist.

Rituals for grief and loss help us process emotions we experience in life. This summer my family was enjoying a few days in a lovely small town on the Mediterranean coast of France when my college-aged daughter received news that a high school classmate of hers died while hiking. While my daughter was not close friends with this classmate, she still knew this person and had been in dance classes with this person in a fairly tight-knit performing arts school. The reality of death hit my daughter hard. I talked with her about a variety of physical, tangible ways she could remember this classmate. My daughter decided to visit the small cathedral in town and light a candle in remembrance of her classmate.

A small moment of lighting a candle is a ritual that can help process grief and loss. Grief and loss is not limited to death and grieving can spring from a variety of situations. For me, I often feel grief and loss when there is a misalignment with the world as it is and the way I think the world can be. Grief and loss has also sprung from disappointment, from painful experiences, and knowledge of others’ pain such as the horrific suffering in Gaza and Ukraine.

I learned from my experience in mass that gathering in community can be a powerful way to process grief and loss. People in the Book of Mormon felt so strongly about mourning with those that mourn that it led them to make a covenant – an unbreakable familial bond with God. There is power in community; we need each other. I very much wish that in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints that we had days like All Saints and All Souls. I wish we were taught to be present; to simply sit by one another as we ride the waves of life. There is no need to bury emotions with positivity. We can simply be in the moment; we can simply acknowledge the presence of grief and loss. Just like ingredients for cookies (or your favorite dish) need to be mixed before being transformed in an oven, grief and loss need acknowledgement before they can be let go and given to God and/or transformed and transmuted into wisdom, healing, etc.

Life provides plenty of opportunities to become familiar with grief and loss. On 28 September 2025, a man in Grand Blanc, Michigan, USA, fired a gun inside an LDS meetinghouse killing one person and injuring many people. The risk of an open fire gun attack, however small, is one I live with daily as a teacher so while sad, this news wasn’t shocking to me. It was shocking for some people who were suddenly aware and affected in a way that they hadn’t been before that this happened in their community and could happen to them.

Because I live with this threat daily, I admit I was at first a bit annoyed that so many people can go about their days blissfully unaware of the dangers of mass shootings. As a teacher, I have annual intruder and active shooter training and my school holds mandated periodic drills with students. Every time I open my classroom door in the morning, I slide the LockBlok to the unengaged position. Every time I leave my classroom at lunch I slide the LockBlok and slide it again after lunch. I slide it again at the end of the day. It is a physical touchstone reminding me of the small yet constant potential danger. This school year I often think of the September shooting at the Catholic school in Minnesota. This is life for me; responding to an intruder or a person shooting is something I could likely do in my sleep. It is sometimes exhausting though. When I pause to think about the risk, my heart feels turbulent knowing that I would absolutely do what is required to protect my students even though such action would likely leave my own kids at risk of losing me, their mom.

For those who are new to the knowledge of this danger in the world, the events in Michigan seemed to hit like a gut punch. It took me a moment to remember that my covenant is to mourn with those that mourn. We so very much need each other. We need community. I grow more and more convinced that community is why we have church. Those of us in the LDS church can learn from the rituals our Catholic siblings have because we too need ways to mourn and process in community. Even a mention of the Michigan events over the pulpit would be a step forward from the silence that seems to prevail now. For more ideas about processing grief and loss in community, this article is a great place to start: The Growing Movement to Bring Back Community Grief and Ritual.

Bringing community back into the church would also be a great place to start moving towards community rituals for grief and loss. After all, we can’t process grief and loss as a community if there isn’t a community to begin with. Blogger Candice Wendt has pointed out how much we have lost community in the church in writing The Insidious Exchange of Community for Covenants. We can turn this around though. My daughter’s ward has a standing once-a-month potluck. I love when I get to visit her on potluck Sundays. This is one idea; I am confident that we are creative enough to think of ways to create what is needed in our particular circumstances with our particular resources.

Something else to consider is that while the church provides a structure, there is no need to depend on the church and wait for often overworked and under-resourced leaders to provide what is needed. I am adopting some of the habits of the liturgical calendar in my life and family because it is a structure that already exists; a structure that grounds me to the rhythm of changing seasons. Other resources include parent groups, making dinner groups with friends, finding resources available through meet-up groups, library groups, etc, etc. It does take effort. The beauty is that as adults, we can reach out to others in ways that align with our values and desires and are within reach of the capacity we have. Even a simple group text of friends can provide community. Right now, that is often all I am able to do and it is ok. I have grand dreams of Twelfth Night parties in January and of summer barbecues; of fall bonfires and cozy winter dinners. Right now, reality is that it took me a couple of weeks to get one brunch scheduled with my family and another family that we are friends with. And then two-thirds of my family got sick and we had to reschedule brunch.

In the meantime, I am grateful for the bloggers and readers of Exponent II. This is a place that prioritizes community over conformity. This is a group that stretches across time and place from whenever and wherever you are reading this to Boston in 1974 to Salt Lake City in the 1870s. Tonight I will light a candle in remembrance of all who gather here at Exponent II – whether virtually on the blog, in reading the magazine, or attending the annual retreat – in an effort to share each other’s stories as we journey together through life.

November 27, 2025

Give the Gift of Exponent II

November 27, 2025 EditorThis holiday season, give the gift of Exponent II.

November 27, 2025 EditorThis holiday season, give the gift of Exponent II. The first issue of Exponent II I ever read was gifted to me by a friend. Sitting on the floor of my laundry room, the words and art of Mormon women and gender minorities wrapped me up and held me for hours. And now, as the Exponent II managing editor, I am awed again and again by the brilliance, tenderness, and honesty of each prose, poem, and art piece we publish.

The love, work, and expertise that go into creating Exponent II—from the writers and artists to the editors and designers to the printers and shippers—make this quarterly magazine a gift of art, of community, and of history. This holiday season, we hope you will consider sharing the gift of Exponent II.

To gift a year’s subscription of Exponent II:Visit exponentii.org/gift and choose your subscription type:Print delivery: $50/year (or $45/year for a renewing subscription)Digital subscriptions: $23/year (or $20/year for a renewing subscription)At checkout, include the recipient’s name and address in the shipping sectionPrint or email our “Welcome to Exponent II” postcard so the recipient has everything they need—including how to set up an account for free online access to the magazine!What your recipient will receive in 2026:Four themed issues featuring art, prose, and poetry from a wide range of voices:

Winter: Contest issue – AgingSpring: Open-theme Summer: RitualFall: Borders

We wish you a magical holiday season—and hope Exponent II will be part of the joy you share.

My Exponent II Gratitude List

November 27, 2025 Rose

November 27, 2025 RoseToday on Thanksgiving, I am grateful for the following things (and many more):

All Exponent II writers, readers, and volunteers for creating a safe place where we can speak about women’s issues. We need a place to share their ideas and concerns since they are too often silenced at church. I honor all who sacrificed much of their time and energy to create the magazine and blog.

All who recognize the innate value of others, including women, LGBTQAI folks, refugees, and every marginalized group in the world. When all churches, institutions, government leaders, and people throughout the world see the true worth of others, wars will cease, strife will end, and our hearts and communities will begin to heal.

Every person who “forged the way for women to vote, own property, and receive equal pay for equal work.” LDS national leader Esther Peterson worked hard to advocate for working women nationally, and we celebrate her and all others who have helped in this cause. Esther said, “Women’s place is where they can do the most good.”

Relief Society when it was an autonomous organization with its own budget, curriculum, magazine, and control over the humanitarian donations and giving of the Church. Emma Smith, its first president said, “On the day Relief Society was organized, Emma Smith, declared: “We are going to do something extraordinary. … We expect extraordinary occasions and pressing calls.” May the Church restore Relief Society to the independence it once had.

All feminists who speak up for truth, justice, and love, who ask for collaboration—not authority over, and who ask for respect and equal voices where decisions are made. Sojourner Truth wrote, “I raise up my voice—not so that I can shout, but so that those without a voice can be heard… We cannot all succeed when half of us are held back.”

All who reach out with love to help the hungry, unhoused, refugees, sick, suffering, and lonely, and for all who share the gifts of life, love, learning, and listening, who speak with kindness and who listen with empathy. Former General Relief Society president, Linda Burton, speaking about serving those in need– especially refugees–said, “As we consider the ‘pressing calls’ of those who need our help, let’s ask ourselves, ‘What if their story were my story?'” Empathy matters. Kindness matters.

My foremothers who served as ward clerks, gave healing blessings, and ran ward Relief Societies with autonomy and grace. May the LDS Church allow women to reclaim their innate authority. Outstanding LDS feminist writer and professor, Dr. Joanna Brooks writes, “Many, many administrative responsibilities within the institutional culture of the LDS Church that have nothing to do with priesthood at all have been customarily restricted by gender, and this sends a powerful message about the value of women’s experience and authority within the Mormon world.”

My faithful feminist mother who taught me to follow my heart, finish my education, live my authentic life, and speak truth to power. I didn’t fully understand what she was teaching me until after she died, but I do now.

Beautiful Mother Earth with her glory, wonder, and majesty. May we treat Her with the care and respect that She deserves. May we find ways to protect Her air, water, soil, and vegetation with wisdom and healing work. Wangari Kuria is doing that in Kenya, where she is devoted to social justice, environmentalism, and empowering female farmers. She said, “ In our local language, Kiswahili, global warming literally translates to: ‘Alarm, alarm! The world is on fire.’ This is something the whole world needs to hear.”

Prophesses in the Bible, including Anna, Miriam, Deborah, Huldah, and apostles, including Mary Magdelene and Junia, who exemplify the power of female religious leaders. A writer, perhaps Hippolytus, a Christian leader in Rome around 200 CE. wrote “that Jesus first appeared to the women at the tomb and instructed them to tell the disciples that he had been raised. He then appeared to the male disciples, upbraiding them for not believing the women’s report.” Hippolytus wrote: “Christ showed himself to the (male) apostles and said to them, ‘It is I who appeared to these women and I who wanted to send them to you as apostles.'”

On this day of thanksgiving, may we celebrate the strength, courage, and resilience of women past and present. May we honor the trailblazers who challenged norms and fought for equality. Let us be grateful for the sisters who lift each other up, creating a world where every voice is heard and valued. On this day of gratitude, may we also commit to justice, respect, and empowerment for all genders. Together, may we nurture compassion and stand united against oppression. Here’s to progress, persistence, and the power of community—today and every day.

Melody Beattie wrote, “Gratitude unlocks the fullness of life. It turns what we have into enough, and more. It turns denial into acceptance, chaos to order, confusion to clarity. It can turn a meal into a feast, a house into a home, a stranger into a friend.”

Happy Thanksgiving, friends.

Thanks to Unsplash and Pexels for the photos.

November 26, 2025

Does Jesus Love White Men More than Child Victims?

November 27, 2025 Linda Hamilton

November 27, 2025 Linda HamiltonD. Todd Christofferson’s brother, Wade Christofferson, was arrested for alleged child sexual abuse this week. The LDS church knew for decades and it was never reported to civil authorities.

Wade Christofferson, Image from Floodlit.org

Wade Christofferson, Image from Floodlit.orgLet’s imagine you have a child in the local elementary school. You’re shocked to find out that one of the teachers has been arrested for sexual abuse of a child. Rightfully, all the parents are horrified and worried for the victims. You demand justice and to know how this could have happened so you can help prevent in the future.

Then you find you that same teacher used to work in another elementary school across the district. It turns out a decade ago he was caught abusing several children. But the principal felt it was best to handle this issue internally. So he fired the teacher and told the school he was let go for a personal issue in their marriage that was affecting their work. No one involved with this original case called the police or let other schools know what the teacher had really done. Again, parents rightfully demand answers for why that teacher was never brought to the attention of authorities and why so many other men covered it up with a lie.

Now you find out the teacher is actually the brother of the school superintendent. There’s no suggestion the superintendent did horrible things like his brother, but he’s been in positions of power at the school district for decades. He also know his brother’s family and marriage situation. The odds that the superintendent did not know about abuse is exceptionally low. But he never called the police on his brother or helped the victims.

Parents are angry. They demand for the superintendent to resign. If power will protect power, as it usually does, they will express their disgust by voting him out next election. This story will be in local news cycles for years. Parents will demand new protocols be put in place to make sure this never happens again to another child. The victims will find strength knowing that they are supported by the community.

If this is how we would reasonable react to such a horrible situation in our school district, why should this same thing happening in our church be any different?

Because that’s exactly what happened. Wade Christofferson, brother of D. Todd Christofferson the second counselor in the First Presidency, has been arrested for alleged child sexual abuse. Please read this important reporting that shows the timeline of the alleged abuse.

Around 1996, Wade was excommunicated from the LDS church for alleged child abuse. The story circulated is that he was ex’ed for having a romantic affair with an another adult, according to survivors and relatives. Between 1998 and 2006, Wade was re-baptized into the LDS church. The annotation on his record forbidding access to children was also removed. After 2006, he served in numerous leadership positions that put him in positions of trust in the ward and in contact with children. In 2008, his brother Todd was made an LDS apostle, the highest level of leadership. According to floodlit.org, the organization that identifies child abuse stories in the LDS church and originally broke this story, D. Todd Christofferson knew about his brother’s child abuse as early as 2018. He is now sitting in the highest presidency of the entire church, one that members are told following literally equates to following Jesus and God.

This case is evidence of a system-wide failure of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to protect children and stop abuse. We already know this is a huge problem, despite what the church tries to say or sue over. Now there’s a case involving the highest office of the church and we need to reckon with that, not brush it aside or give excuses.

Wade Christofferson was directly enabled by his local church leaders when they did not report the alleged abuse. Whether that came from a higher authority or not, those men chose to allow a man who had alleged sexually abused children to walk away from the full legal consequences of his actions. This immediately opens up opportunities for him to find new victims. Local male leaders further allowed (or possibly started) rumors around Wade’s excommunication that obscured the truth, again leaving him openings to continue his abuse without families knowing he was a danger to their children.

Excommunication does not stop abusers. Maybe in the most perfect of situations it gets them to stop, but evidence shows that abusers are likely to reoffend. They should be reported to law enforcement. Maybe they will never be convicted but at least the church will have done the right thing. And even if the abuser did stop completely after being ex’ed, have they actually truly repented if they don’t make restitution for their sins? I’m so sick of being taught supposed eternal gospel principles in Sunday School lessons, only for the church as a whole to wildly ignore it’s own teachings whenever it serves them.

Wade should have been reported to police by someone in the long chain of church hierarchical authorities when the abuse first came to light. Their failure is a systemic issue that continues to place white men, their “repentance” and “good name,” above child victims. This failure teaches that stopping abuse is about protecting the church’s image and authority, not finding justice and healing for victims.

I also find it extremely hard to believe that D. Todd Christofferson didn’t know about his brother’s actions. Even if it wasn’t until 2018 that he found out, he should have been on the phone with the police right then. And what about the priesthood men who called him to be an apostle in the first place? This is the highest level of public attention in the church. Is it really possibly in today’s world that potential apostles aren’t thoroughly investigated for potential scandals? Even if Christofferson himself did not know about Wade’s sexual abuse when he was called as an apostle, the brethren who called him certainly did. They have access to every record in the entire church. I find it impossible to believe that a church that actively spies on its own members would not have at least glanced at the official records of family members of a possible apostle, including past notations on records.

The prophets and apostles failed the victims of Wade’s alleged abuse. They could have stopped this at any time and chose not to. Should D. Todd Christofferson be held personally responsible for not reporting his brother’s actions? Should he resign? And what does this say about priesthood church leaders’ supposed powers of discernment? If God speaks directly to prophets and apostles, he never once bothered to let them know that one of their own was directly linked to an alleged sexual abuser and that could cause future issues? God never showed up tell a single man in the priesthood chain that abuse should be reported, not covered up? Not a single priesthood man that’s supposed to be getting callings directly from God ever got a prompting that the man the wanted to call was an alleged sexual offender? Jesus must really love white men.

Members of the LDS church should be openly and loudly calling for reform with this breaking news. We should be demanding worldwide background checks on members who work with kids and for “asterisks” on members’ records to never be removed in cases of alleged child abuse. Most of all, we should be screaming from the rooftops for the church to adopt the policy of reporting each and every confession of alleged abuse. Choosing not to do only enables abusers and further harms victims.

The LDS church claims to speak directly for Jesus. If the church is literally Jesus and this is how abuse is handled systemically throughout the church, then Jesus cares more about white men, their reputations and souls, than he does about children and victims. I feel like there’s a scripture about this in the New Testament, right from Christ’s mouth… but gotta protect that patriarchy, I guess.

A Really Great Company For Women

November 26, 2025 Josie Grover

November 26, 2025 Josie GroverA thought experiment where we apply religious patriarchy to a secular setting.

The scene as follows is a hypothetical job interview between a male interviewer and a female job candidate. A woman named Susie who works for the company is later introduced.

Photo by charlesdeluvio on Unsplash

Interviewer (I): Hi. Thanks for meeting me today. It looks like you are here to interview for a sales position. We really have a great sales team. So shoot. What can you tell me about yourself?

Job Candidate (JC): Thank you. I left my last job so we could move here for my husband’s masters program. I was a team lead in my past sales department and consistently oversaw a successful increase in numbers. And recently I finished an online course in accounting, so I am hoping to make the jump into the financial division of business in the future.

I: (shifting uncomfortably in his seat) That is all amazing , you sound like a great asset to a sales team. I do have to tell you though, we don’t have women in finance in this company.

JC: Oh! May I ask why?

I: It’s written into the company handbook. We don’t know all the reasons the handbook was written the way it was, but we trust it. But nonetheless, we value women. Women are considered equal to men. And changes to the handbook could theoretically happen.

JC: I could hold out for change. ( forcing a warm smile)

I: Men here take on a lot more of the real intense responsibilities so women don’t have to be under pressure at work. And for working mothers we have in house childcare and a room for nursing mothers.

JC: um OK, I do plan on having children in the next few years, so part of what you said is promising information.

I: I myself am a dad of two daughters who I adore, so I carry that love into the workplace. That’s just how I am personally and all the guys really. Some of our ladies here put together a monthly meet and eat and we all love them for it. Anyways, tell me what you think you could personally bring to this company?

JC: Well, given my past leadership success, I consider myself to be an asset in that regard. I would love to continue to build my portfolio with other leadership opportunities.

I: Excellent. We have a lot of leadership positions for women. Women are really considered as equals here. Let’s see … the childcare director is a female only position. The head of design is a woman. There is a CEO of women’s associates. She has two assistants.

JC: Oh, so if I understand, you have a CEO over women and a CEO over men?

I: No the main CEO is over the whole company. Men and women.

JC: I have to admit it is unique to have a female specific CEO on the board.

I: Actually there are no women in our board meetings. The top leadership positions are men only. But we have a board member who is assigned as a consultant to the women’s CEO team. They do check ins with those women and bring their concerns and ideas to our board meetings because we value the voices of women. Women are equal in this company.

JC: Yes. You did mention that earlier. But what I am hearing is that women are not given supervisory roles over men nor are they directly involved with company wide oversight and development. This is just a big change from my last job where our CFO was a woman.

I: (nose twitching) I see what you are saying but we empower women more broadly here. The higher ups are the best. They hold multiple trainings a year on life balance and self actualization. Those trainings are open to men and women free of charge. We have seen the way this has really benefited the company, as well as individuals in the company. Women the same as men. At the end of the day, I don’t know of any other company that gives so much encouraging power to women.

JC: (sits quietly pondering on how this interview happened to become all about gender. She had been hoping to share some her past positive performance reviews)

I: What other questions do you have for me?

JC: (She takes a deep breath before continuing) I wasn’t going to mention it but I was recently informed by a friend of one of your former employees that there was some serious misconduct allegations from a male supervisor toward a female intern he was mentoring. Maybe you can dispel that rumor for me or clarify what safety measures you have in place going forward. I have to be honest. My misgivings here are in the concern that unbalanced gender dynamics in the workplace often gives rise to these sort of problems.

Susie (S): ( pops her head out from behind the open door) I’m sorry to interject but I just overheard as I was walking by and have to tell you that I love being a woman in this company. I have never ever felt harassed or less than a man working here.

JC: Umm ok, thank you for that?

I: Let’s be clear. We do not tolerate workplace improprieties. And really this does not reflect on the company as a whole. These types of things happen in every kind of company. But we also believe in forgiveness and making amends, so the supervisor in question will remain anonymous. He was given administrative leave to attend some professional relations workshops.

There is a few seconds of awkward silence.

I: Well thanks for coming in. Hey Susie! Will you give this young lady a little tour on her way out? And we will be in touch.

As the women are walking down the hall toward the exit, Susie opens the door to a spacious room with art on the walls and leather chairs.

S: This is the board room.

She opens the door to the next room which is small with a second hand rocking chair and a full diaper pail in the corner.

S: This room is for moms to pump or nurse their babies.

JC: Lovely.

S: I hope you join us. We have had a few women leave us lately so we are a little short staffed.

JC: I hope you don’t mind me asking but do you not find it contradictory that there is so much talk about equality but women can’t hold so many important positions?

S: Not at all. It’s a company mantra that governance in business is equal to motherhood in society. They want to make sure women are not torn between work and home. They tell us in meetings that they think moms are better for civilization than men in suits are. So I feel honored.

JC: I’m sorry, but what does one’s domestic life outside work have to do with what happens in this building? And not all women are moms. I assume there are men running the company that have kids. Are we actually thinking men are better at the balance between work and home? Are fathers not also valuable to society? (She could feel herself getting frustrated. and wondering if she was the one out of touch here?’)

S: Wow! You sound a little like one of those angry feminists who want women to be like men.

JC: I think I’m done here.

End Scene

November 25, 2025

LDS Garments Throughout Your Life

November 25, 2025 Kate Baxter

November 25, 2025 Kate BaxterThis is my truth. Your mileage may vary.

I was one of the many people rushing to a Church Distribution Center in Utah on the Tuesday when the newest styles of garments were released. I’d been watching the calendar since they were announced—not because I wanted more clothing options or to feel relief in sweltering heat, but because I needed to find out if I’d ever wear garments regularly again.

Like many things about Church, my relationship with garments is complicated.

LDS Women’s Sleeveless Garment Top

LDS Women’s Sleeveless Garment TopWhen I received my endowment in the 1980s, the temple matron was crystal clear. Gs were to be worn ALL the time and failure to do so would result in me being booted out of the Celestial Kingdom, my family broken and lost, and God so disappointed.

Nothing was to come between me and my garments, not my bra, nylons, or anything. She said one-piece styles had crotches that could be pulled aside to allow access to a pad stuck to regular underwear worn over garment bottoms. G tops always had to be tucked into G bottoms, fully and tightly.

While I could take my Gs off to bathe and have sex, they had to be put back on immediately after, and—by the way—one-piece styles make it possible to only remove them for quick showers. A double blessing since I was getting married in a couple of days.

When I blinked, the matron told me that suffering was the lot of women—see Eve—and that murmuring was of the devil. Suffering was holy and purified you, so suck it up, Buttercup, and get with the program. God will bless you in the end if only you are faithful enough. Oh, and Gs must be spotlessly white at all times. Stains on your garments were like sins on your soul.

The first rule about temple? We don’t talk about temple. Zip it.

Really. All true. But with less sarcasm, Buttercup, and more fear.

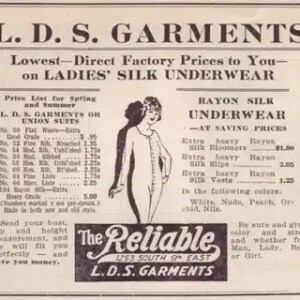

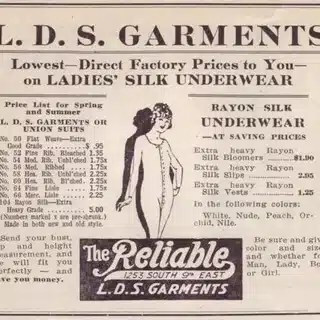

Historic Newspaper Ad for LDS Garments

Historic Newspaper Ad for LDS GarmentsIt’s worth mentioning that this was in the era before temple prep classes and that I was alone with the Temple Matron when she told me all this. I had no close female relatives or friends who wore garments. I had no one to ask even if I thought I could, so like anyone wanting to follow Christ and looking for the path, I went in the direction I was pointed. Over the years I escorted many women receiving their endowments who didn’t get the same instruction manual I did, but my original factory settings stuck.

1980s Women’s Office Attire

1980s Women’s Office AttireIt’s funny/not funny when I think of all the things career women did in the ‘80s and ‘90s to make garments work for us. This was the era of power suits, and the professional world insisted on pantyhose in the office, at least when wearing dresses and skirts. We battled keeping pantyhose worn over Gs around our waists and not our knees. When thigh-high stockings came along, we wondered how much it mattered that the top edges of the stockings were technically under our G legs. It ended up being a distinction without a difference because thigh-highs weren’t any better than pantyhose for getting through a workday without a wardrobe malfunction. We all carried safety pins.

Pants worn with knee-high nylons were an easier option, but the bottom edges of our Gs showed through our work slacks and bunched along our thighs, looking worse than the dreaded panty lines on TV ads. The mid-calf length Gs were better for work but had their own challenges. Fabrics sometimes didn’t play well together which made walking up and down stairs sketchy as pants tended to fall off hips as long G bottoms pulled at the knees and slithered against the silky tucked tops. Belts only helped a little.

Itchy lace edges always found ways to peek out along the modest necklines of my shirts. Bras worn over DriSilque had to be cinched very tight and made with underwire cups or they’d slip and strangle if I raised my arms too quickly or too high.

I was constantly twitchy, never at ease, always checking to make sure things were where they were supposed to be and usually discovering to my horror they weren’t. I had to weigh what I was going to do and say in business meetings because of fear of my garments showing or pants falling down.

Mostly, I remember the looks from the LDS men I worked with as I yet again adjusted my garments as discretely as possible. It was especially tough as the boss lady who led team discussions and diagramed constantly on white boards. I’d catch men rolling their eyes. Their wives didn’t have these issues. But their wives weren’t in the boardrooms either.

It wasn’t a matter of buying the right size or type. I really did try them all.

Garments never, ever fit me like they were supposed to. I have extra-long arms and legs attached to a petite torso with big boobs, bread dough belly, and no booty. Tucked G tops often came to mid-thigh. Gs slipped off my shoulders and knotted around me when I turned in my sleep—my knickers were constantly in a twist. Sometimes I woke up with a torniquet tingle in an arm or leg.

Whenever I tried to sleep naked I had horrific nightmares, my subconscious certain I was damning myself and my family with my faithlessness. After intimacy, I redressed as quickly as possible. You can imagine how that unexplained behavior was interpreted by my husband, who didn’t live under the directions I felt I had to. On vacation when it really was too hot for all those layers, he simply did what made sense without any angst.

Unfathomable.

And also unspeakable.

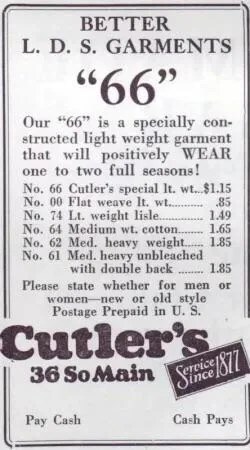

Historic Newspaper Ad for LDS Garments

Historic Newspaper Ad for LDS GarmentsAs terrible and burdensome as these experiences were, it wasn’t until a couple of years ago when my personal suffering hit an all-time high that I began to question my assumed obligations. Ironically, the straw that broke the camel’s back was the announcement of the new styles along with comments from apostles that exposed biases and beliefs that did not resonate with my lived experiences. In the April 2024 General Conference, President Oaks said, “Because covenants do not take a day off, to remove one’s garments can be understood as a disclaimer of the covenant responsibilities and blessings to which they relate.”

What? Understood by whom? You? Because God knows exactly why I’m not wearing my Gs at any moment, and it’s not for any of the reasons you cite.

Bubble officially and permanently popped.

Prior to this talk, I had health challenges that made wearing garments painful and unhealthful. I should’ve stopped then, but women suffer was still loud in my head. I persisted and things got worse. Eventually, it became too difficult to manage all the layers as quickly as I sometimes needed to. I was in constant pain that made everyday life way too hard, with or without Gs.

The good news is that surgery and sleeping with my neither regions in the buff brought things near normal. The best news is that my relationship with garments is no longer one of coercion, but of choice.

Honestly, it should’ve been that way from the start.

When I first told my husband I was going to experiment with garment wearing and that it had nothing to do with how I felt about the commitments we made to each other, he simply nodded and held his breath. Over the last year I discovered I’m the same person without garments, just far less twitchy and no longer worried about my pants falling down when I approach stairs. There’s an ease in my body that’d been missing for far too long. I still wear all the same clothes and styles I used to—there’s no new outward reflection of an inner lack of commitment that anyone can see. There’s also no way I’m going back to wearing Gs 24/7.

But.

Back in the ‘80s, I covenanted to wear them throughout my life, something very different from what the Church says now. Despite my personal revelation that much of the to do about Gs is man-inspired, not God-required, I still feel there is something significant to giving my word.

LDS Women’s Full Slip Garment

LDS Women’s Full Slip GarmentSo that’s why on a Tuesday afternoon I was at the main distribution center in Salt Lake City purchasing a couple of the very last full slips in my size. It had nothing to do with fashion and everything to do with figuring out how to go forward.

And for me, full slips make pretty good nightgowns. They’re also the best option under Sunday dresses when worn over regular underwear. I take that for the tiny win that it is.

As I said, this is my truth. Your milage may vary.

Final Doctrine & Covenants Lesson – You Don’t Have To Believe God Is A Jerk

November 25, 2025 Jody England Hansen

November 25, 2025 Jody England HansenThe final “Come Follow Me” lesson for the D & C study this year covers Official Declarations 1 and 2, and the Proclamation on the Family. My husband mentioned the theme seems to be spiritual trauma.

A few weeks ago, during Gospel Doctrine class, section 132 and the subject of polygamy was not mentioned until the last few minutes of class. The pain in the room was palpable. There was an acknowledgement by the teacher that Section 132 and polygamy was very difficult, even painful for many. There was also an attempt to fix that problem by showing part of a talk by a general authority. The speaker said that if you can answer the big questions such as “Is there a God?”, “Was Joseph Smith a Prophet?”, etc. then all the questions about polygamy, the priesthood ban, gay marriage, women’s ordination became secondary to that, and no longer an issue.

It didn’t help. Any attempt to dismiss pain and trauma with a quick fix never does.

For the final lesson next month, polygamy will come up again because of The Manifesto, or Official Declaration 1, which declared an end to the practice of polygamy (even though it didn’t actually end). I hope anyone who teaches or attends understands the importance of sitting with pain and trauma, and acknowledging that it is real. If that is the only thing that happens, people will feel they are not alone in their pain. That brings comfort and lightens burdens. There is nothing to fix, and there is nothing wrong with feeling pain about polygamy, or section 132, or the priesthood ban, or exclusion policies impacting women and LGBTQ+ persons. It is okay to not be okay about this. It is important to get why this is especially traumatic.

The lesson before section 132 included section 121. I think this is one of the most inspiring scriptures we have. One view of it is this – Joseph is feeling hopeless and hurting. He turns to God and asks for revenge and destruction of his enemies. He is asking God to be vengeful, and wipe out people who make Joseph’s life harder, because Joseph is sure he is right, and God would be on his side and against anyone who doesn’t support him. In other words, Joseph is asking God to set aside Their love for all, sever oneness with all, use Their power to deny agency and use force in order to fix Joseph’s problem.

God says We don’t work that way. We can’t work that way. If We tried, We would not be God. There is a warning about how susceptible “almost all men, as soon as they get a little authority, as they suppose” are prone to abusing that authority and exercising unrighteous dominion. The rights and powers of the priesthood are inseparable from powers of God. The moment they are used to cover sin, feed pride, or ambition, or exercise control or dominion or compulsion on anyone in any degree, in that moment there is no authority, no priesthood, no spirit of heaven, no God. And then They give a very concise, challenging, clear description of the qualities that apply to God and godlike power, referred to as priesthood power. This is the greater eternal priesthood because none of the qualities or actions are gender specific. God, and any person exercising any degree of any authority to act in any way in connection with God can only do so with “persuasion, by long suffering, by gentleness and meekness, and by love unfeigned; by kindness, and pure knowledge, which shall greatly enlarge the soul without hypocrisy, and without guile…Let thy bowels also be full of charity towards all men, and to the household of faith, and let virtue garnish they thoughts unceasingly.”

This is one of the clearest, most challenging and confronting litmus tests for how to recognize when words or actions of anyone, including spiritual promptings, and especially people in all levels of leadership and authority, are in line with the God of love, the God emulated by Christ and his teachings, the God of At-One-ment, the God that sits with me in woundedness and sorrow as well as joy, the God that inspires me to follow that example.

In summary, section 121 reveals that God is Love, God will never impede agency, God is not a jerk, and the moment anyone is not following this example, no matter what authority they claim, they have no power or authority from God.

This requires us to pay attention, and not automatically connect God to anything said or done by leaders, even if they claim prophetic authority, if it is not in line with qualities outlined in section 121.

Compare this to section 132. This section has a messy history and controversial provenance. Several recent Dialogue Sunday School lessons by Benjamin Park and Maxine Hanks offer some of the complex issues of this section. Countless writings, blogs, podcasts, and discussions wrestle with the issue of polygamy in connection with this section.

I have also wrestled with this issue in different ways. Learning of the history as a student and helping research primary sources when working at the Church History Department was confronting, and I owe a great deal to the historians there who understood and honored that experience. I spoke with my grandmother about her lived experience with polygamy. She shared journals which enabled me to learn how devastating it was for her parents when they felt required to practice polygamy. It was heartbreaking reading about how women taught each other ways to survive the heartbreak of sharing their husbands by never allowing themselves to completely love him, withholding complete loyalty to all except their children. I experienced it myself when men I dated suggested that if I were righteous enough, I would learn to be fine with it, and that a man could learn to love multiple wives enough just as they could learn to love multiple children (and they couldn’t understand why this would be horrible for a woman to hear). I experienced the terrible ongoing presence of so-called spiritual polygamy when a man I was dating told me he planned on being sealed to his deceased girlfriend who had died in an accident before they were engaged. He intended her for his first wife. He expected me to be his second wife, and wanted me to be aware of and agree to that lesser station in this polygamous marriage. That was when I made it clear we were no longer dating, and that I had no belief in polygamy being from God. From then on I would ask anyone I dated more than once what their thoughts on polygamy were, and it became a deal breaker depending on the answer.

But none of these experiences compare to the appalling language in section 132 which describes a god that imposes a different law upon his daughters than that of his sons. The worst examples of Old Testament prophet figures using women as property and breeding machines are used as justification, contradictory to the warnings and teachings from the Book of Mormon, and the former section 101 which condemn this very behavior. The actions and words of this god directly contradict the qualities outlined in section 121. Women become figures that promote the abuse of power and authority that section 121 warns us about, making it clear that God who is love, who honors agency, who is not a jerk, would never sanction any of this. And yet, the overwhelming demand for people in 19th century Mormonism to accept and practice this as coming from god was often linked to being able to survive in community, at great cost. And also the pressure on 20th century Mormons to accept this as coming from god, and to allow it to exist as a possible condition of living in the presence of god in the next life, kind of like horrible greenish storm clouds hovering over the distant horizon. Not to mention the trauma of hearing rhetoric that minimizes any Divine Feminine figure to one of countless polygamous wives in constant pregnant state supplying eternal increase to one heavenly father.

There is nothing about that god that inspires me, or calls on me to worship or follow. I want no part of that eternity. That god, and those he justifies, have no love, do not honor agency. That god is a jerk.

The same process is what guides me concerning the racist justification of the priesthood ban. It guides me when policies are imposed that exclude entire groups of people because of their gender or non-binary existence. The God of love did not inspire those.

Since the Doctrine & Covenants is our most recent scriptural text in our very young religion, and since we now have access to the extraordinary work of the historians with the Joseph Smith Papers Project, we can be aware of the very human lives of those who created this scripture.

We can learn when they were trying to cover their sins, or claiming authority for authority’s sake, or gratifying pride and ambition, or aspiring to the honors of men (including church callings), or exercising control or dominion. We can look for ways they blame god for their failures.

We can be aware of when they owned their mistakes, and acknowledged their humanity. We can see when they were sharing their experiences of seeking and listening for the God who is love, who honors agency, who inspires compassion and transformation. And we can look for when God answered with love, encouraging agency, inspiring transformative connection that leads us to Them.

It is interesting that the final lesson for the year covers declarations that overturned policies and temporary doctrine that was and continues to be incredibly harmful. Without the 1890 Manifesto, and the 1978 lifting of the priesthood ban, I don’t think the church would exist as any kind of worldwide organization. Both came about because enough people realized something about the organization did not align with God, or the Gospel of Christ. Something about the organization required repentance on an institutional level, which had to begin with individuals.

A large part of the study of the Doctrine & Covenants is a study of history. I hope that study it will lead to more than an automatic acceptance that all sections came directly from God. I hope the more valuable lesson will be taking on the practice of looking for the different ways the leaders and members of the church struggled with their own trauma, and humanity, and questions. When did they seek to justify the worst qualities of Old Testament figures with the language of an Old Testament deity? When did they earnestly ask questions that invited expansive possibility and listen for the God of Love?

For me, the most important lesson of this study is learning that I can practice recognizing when a prophet is speaking as a prophet, and when they are not. I can acknowledge the danger of idolizing leaders, because that is as dehumanizing as is demonizing them. I can learn to recognize God’s voice when it honors agency and inspires love and connection.

And I don’t ever have to believe that God is a jerk.

November 24, 2025

Guest Post: The Girl in the Bubble

November 24, 2025 Guest Post

November 24, 2025 Guest PostGuest Post by Anonymous

Tears streamed down my face as I listened to Ariana Grande sing Glinda’s song “The Girl in the Bubble.” Wicked has been bringing up a lot of emotions for me lately. There are many themes that I related to last year when part one came out, such as unrequited love, perfectionism, and challenging the idea of institutional infallibility that Elphaba struggled with in school.

This year, the feelings were different. As much as I can see parallels to my life story and Elphaba’s struggles, Glinda’s story really resonated with me last night in the theater. At first, she really believes that the institution can be fixed. That it’s doing better. That it will change if left to its own devices. She then begins to realize the sacrifices that are being made by those she truly cares about as they are made out to be scapegoats. She sees how truly expendable everyone is to the Wizard and Madame Morrible.

I saw her struggle to stay or go, to try to change Oz from the inside or abandon it altogether. All her life she has dreamed of being loved and magical. And she finally is. But it is nothing like she could’ve ever imagined.

There’s that beautiful girl

With a beautiful life

Such a beautiful life built on lies

‘Cause all that’s required

To live in a dream

Is endlessly closing your eyes

…

Ah, but the truth has a way

Of seeping on in

Beneath the surface and sheen

And blind as you try to be

Eventually

It’s hard to unsee what you’ve seen

And so that beautiful girl

With a beautiful life

Has a question that haunts her somehow

If she comes down from the sky

Gives the real world a try

Who in the world is she now?

And though so much of her wishes

That she could float on

And the beautiful lies never stop

For the girl in the bubble

The pink shiny bubble

It’s time for her bubble to pop

For so long, I was the girl in the bubble. I memorized the articles of faith, went to the temple regularly, served a mission, went to church every single week without fail, fulfilled my callings, prayed with her whole heart. But I couldn’t close my eyes to the lies anymore.

Right now, I feel like Glinda. Trapped, used, scared, resentful. Coming down from the sky and wondering who in the world I am has been one of the most difficult things.

Leaving the church takes so many different people on so many different paths. Some people can be like Elphaba, leaving and using their voices to spark change. But there are so many Glindas out there, trapped between living authentically and losing the life that they love.

So although my bubble has popped, I’m still living in Oz, and probably always will. But I have hope that just as Glinda was able to make real change in Oz, there can continue to be real change in the church and it can continue to be made better for all those involved. And this will unfortunately always be built off of the sacrifices of the Elphabas of the world who are shunned, excommunicated, and forced into exile for standing up for their beliefs. So now while I have no more faith in the organizational church, I believe in the good of its members, past and present, and the change that they can make.

The author is a current college student going through a faith transition. She loves music, theater, and the great outdoors.