Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 34

June 30, 2014

“A world where it is always June”

“What would it be like to live in a world where it is always June?” asks L.M. Montgomery in a journal entry on June 30, 1902. “Would we get tired of it? I daresay we would, but just now I feel that I could stand a good deal of it if it were as charming as today.” She had had a terrible night of sleeplessness and worry, and had recovered by walking in Lover’s Lane, one of her favourite places in Cavendish.

Forget-me-nots in Lover’s Lane

“This evening I went for a walk in Lover’s Lane to exorcise my evil spirit,” she writes. “It was efficacious as usual. Somewhere in me the soul of me rose up and said, ‘No matter for those troubles and problems that looked so big and black in the night. They are mortal and will pass. I am immortal and will remain.” Nature always had a powerful effect on her spirits, and while the woods and fields of Prince Edward Island were her favourite cure, even a city park, like Point Pleasant Park in Halifax, could work wonders.

When I reread Anne of the Island a few months ago, I discovered that Anne Shirley echoes these words from Montgomery’s journal, saying to Marilla and Mrs. Rachel Lynde, “I wonder what it would be like to live in a world where it was always June.” It’s Marilla who replies, “You’d get tired of it,” and Anne concedes that she would, “but just now I feel that it would take me a long time to get tired of it, if it were all as charming as today. Everything loves June.”

When I reread Anne of the Island a few months ago, I discovered that Anne Shirley echoes these words from Montgomery’s journal, saying to Marilla and Mrs. Rachel Lynde, “I wonder what it would be like to live in a world where it was always June.” It’s Marilla who replies, “You’d get tired of it,” and Anne concedes that she would, “but just now I feel that it would take me a long time to get tired of it, if it were all as charming as today. Everything loves June.”

Montgomery often drew on her journals for her fiction, and I’m always delighted to find these connections. The June 30th entry was omitted from The Selected Journals of L.M. Montgomery – one more reason to be glad that The Complete Journals are now being published. In the novel, it’s ten-year-old Davy Keith, not Anne, who is sad despite the beautiful weather. Anne asks why he has a “melancholy November face in blossomtime,” and he answers, “I’m just sick and tired of living.” While it sounds as if he too needs to exorcise an “evil spirit,” it turns out he’s simply discouraged about having too much homework (“ten sums”) that weekend.

In the midst of all the Mansfield Park celebrations here on my blog, I’ve been rereading some of Montgomery’s novels and journals, and last week I spent a few glorious days in Prince Edward Island with my family. I finally bought my own copy of Elizabeth Rollins Epperly’s beautiful book Imagining Anne, which I’ve had from the library many times, and you may hear more about it here soon.

In the meantime, here are a few of my other posts about L.M. Montgomery:

Anne of Green Gables Loves Point Pleasant Park

Point Pleasant Park as a Cure for Homesickness

Point Pleasant Park as a Cure for Homesickness

L.M. Montgomery’s Literary Pilgrimage to Concord, Mass.

Quotations are from The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The PEI Years, 1901-1911, ed. Mary Henley Rubio and Elizabeth Hillman Waterston (Oxford University Press, 2013), and from Anne of the Island, first published in 1915 (Bantam, 1976).

June 27, 2014

Rears and Vices

Eighth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

I first met Devoney Looser at the 2005 JASNA AGM in Milwaukee on “Jane Austen’s Letters in Fact and Fiction,” where she and her husband, George Justice, gave a wonderful plenary lecture entitled “Burn This Letter: Personal Correspondence and the Secrets of the Soul.” Today, I’m delighted to share with you her contribution to “An Invitation to Mansfield Park.” Mary Crawford’s joke about “Rears” and “Vices” has inspired many debates over the years, and I’m curious to hear what you think of Devoney’s analysis of this controversial passage.

Devoney is Professor of English at Arizona State University and the author of Women Writers and Old Age in Great Britain, 1750-1850, and British Women Writers and the Writing of History, 1670-1820, both published by Johns Hopkins University Press. She’s the editor of the essay collection Jane Austen and Discourses of Feminism. Her recent publications include a foreword to a special issue on Teaching Jane Austen Among Her Contemporaries (Persuasions On-Line, 2014) and a short piece on Austen as a feminist icon in the Los Angeles Review of Books.

When not reading, writing about, or teaching Jane Austen, Devoney plays roller derby as Stone Cold Jane Austen, an alter ego that landed her a place in Deborah Yaffe’s Among the Janeites (2013) and won her a theme song (“In the classroom it’s theory / On the track it’s pain”). Follow her on Twitter @devoneylooser and @stonecoldjane.

“Certainly, my home at my uncle’s brought me acquainted with a circle of admirals. Of Rears and Vices I saw enough. Now do not be suspecting me of a pun, I entreat.”

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 6 (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2006)

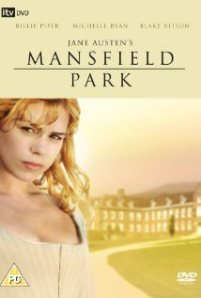

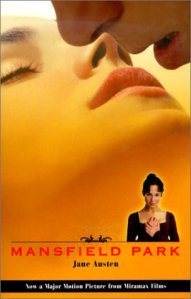

To suggest that there is sex in Mansfield Park – at least in the way that recent film and television adaptations tend to – is rubbish. Austen’s Fanny Price is no bosomy sexpot, à la Billie Piper in the 2007 BBC adaptation. The lurid book cover on the print edition of the novel sold as a tie-in with Patricia Rozema’s 1999 film might lead a first-time reader to mistakenly expect passionate kisses narrated on every other page.

To suggest that there is sex in Mansfield Park – at least in the way that recent film and television adaptations tend to – is rubbish. Austen’s Fanny Price is no bosomy sexpot, à la Billie Piper in the 2007 BBC adaptation. The lurid book cover on the print edition of the novel sold as a tie-in with Patricia Rozema’s 1999 film might lead a first-time reader to mistakenly expect passionate kisses narrated on every other page.

That said, there is sexuality (even dangerous, illicit sex) in Mansfield Park, albeit between the lines. The rehearsals for Lovers’ Vows lead to flirtation and forbidden physical contact, both on and off stage. At the visit to Sotherton, couples flout conventional propriety to sneak off together. By the time Maria Bertram Rushworth runs off temporarily with her lover, becoming fodder for newspaper gossip, we’ve had many hints that it could come to this.

Critics have written eloquently on Austen’s treatment of sex and sexuality, most notably Jillian Heydt-Stevenson and Jan Fergus. Disagreements abound, but one crucial line from Mansfield Park tends to get critics the most hot and bothered. The line is Mary Crawford’s, spoken in Chapter 6, in the hearing of many. It’s especially troubling to her suitor, Edmund Bertram.

Edmund, knowing that Mary formerly lived with her admiral uncle, asks about her knowledge of the British Navy. Mary answers him with jocularity, “Certainly, my home at my uncle’s brought me acquainted with a circle of admirals. Of Rears and Vices I saw enough. Now do not be suspecting me of a pun, I entreat.” Her attempt at wit isn’t met with laughter; we’re told that Edmund “felt grave” after she spoke.

There’s no doubt that she’s making fun of powerful naval men here. She’s already said that in her uncle’s home, she socialized only with highest-ranking of them. It’s clear by this point in the text that she’s willing to pillory these men for their faults. Just prior to this line, she describes them as invariably bickering and jealous.

It also seems obvious that Mary is indeed making a pun. She does not reference “Rear Admirals” and “Vice Admirals,” as she could have. She says “Rears and Vices,” with the italics serving to emphasize her punctuated, droll delivery and the double meaning of the words. Mary coyly invites her audience of listeners (just as Austen invites her audience of readers) to conclude precisely what she says she doesn’t want to be suspected of – that she’s uttering a pun.

The question for us as readers today is, “Precisely how off-color is her pun?” Is Mary making a joke about powerful old men’s big bums and bad habits (gambling, drinking, gluttony, avarice, and adultery), or is she making a ribald joke about the Navy’s associations with sodomy?

Some argue that it’s unthinkable that Austen could ever have thought about – much less have any character joke about – sodomy. Others see Mary’s lines as unquestionably referencing sexual vices having to do with rear ends. They read them as a dirty joke about anal sex and as proof that Austen’s bawdy, wicked sense of humor – like Mary’s – roils beneath the surface of Mansfield Park. Critics have tried out all positions in between, where Mary’s lines are concerned. Most of us have our own strong opinions about how we ought, and ought not to, read this line. In forming our opinions, we must continue to investigate the larger textual and cultural contexts of Mary’s words.

As readers familiar with the hierarchy of the British Royal Navy in Austen’s era know well, vice admirals and rear admirals were the two ranks that fell just below admiral. Together, these were the three highest titles a naval officer could hold, the rest below consisting of various kinds of commodores, captains, and lieutenants. Rear admiral was usually a title belonging to an older man, often reserved to recognize a naval officer previously passed over for promotion, upon his retirement.

The crucial piece of textual information that we ought to remember in reading Mary’s line is what brings her to Mansfield Park in the first place: her admiral-uncle’s taking a mistress into his London home. His very public act – visible to family, servants, and friends, and therefore fodder for rumor-mongering among all parties beyond – means that Mary can no longer live under his roof. To stay there would be read as her tacit acceptance of his debauched choice. It would make her reputation morally besmirched.

In offering her irreverent pun, then, Mary expresses a jaunty skepticism about the Admiral’s profession, but she’s also taking a jab at his unconventional sexual (and romantic?) choices. She demonstrates a lack of filial piety toward Admiral Crawford that readers might forgive her for, given what we know about his dissolute ways. The Admiral is described by Austen’s narrator as “a man of vicious conduct,” one of the most cutting insults used in all of her novels. Vicious in this context means that he is depraved, immoral, and bad. He is vicious both for his open adultery and for his effectively washing his hands of the care of his unmarried, unprotected niece. He chooses to live in sin with his mistress over dutifully guiding Mary in polite society until she’s safely married off.

Wealthy, powerful men at this time certainly had plenty of adulterous affairs, but they were expected to hide their liaisons. The Admiral could easily have installed his mistress in a separate private residence and visited her there almost as often as he liked, without raising many eyebrows. Later in the novel, he’s described as a man who “hated marriage” and “thought it never pardonable in a young man of independent fortune” (Ch. 30). He flouts convention in relationships out of principle and inclination. Henry Crawford means to be different from his uncle, but he doesn’t manage to hold firm. It’s important to remember that Henry, too, could have carried on a secret affair with Maria, under the nose of her oblivious husband Rushworth. Henry and Maria are unwilling to let it stop there. The viciousness in the Crawford family tended toward the spectacular. This might seem to support a reading in which Mary’s joke should be read in the most outrageous way possible.

Wealthy, powerful men at this time certainly had plenty of adulterous affairs, but they were expected to hide their liaisons. The Admiral could easily have installed his mistress in a separate private residence and visited her there almost as often as he liked, without raising many eyebrows. Later in the novel, he’s described as a man who “hated marriage” and “thought it never pardonable in a young man of independent fortune” (Ch. 30). He flouts convention in relationships out of principle and inclination. Henry Crawford means to be different from his uncle, but he doesn’t manage to hold firm. It’s important to remember that Henry, too, could have carried on a secret affair with Maria, under the nose of her oblivious husband Rushworth. Henry and Maria are unwilling to let it stop there. The viciousness in the Crawford family tended toward the spectacular. This might seem to support a reading in which Mary’s joke should be read in the most outrageous way possible.

But there is one further piece of evidence we ought to consider in reading the “rears and vices” line. The word “vicious” is, of course, from the same etymological root as vice. That connection would probably not have been lost on Austen in writing the novel, using both of these words as she did at such crucial textual moments. The Admiral’s most visible and recent viciousness – that most centrally related to way the plot unfolds – is his illicit heterosexual activities.

The vices that Mary is most likely to have seen under her uncle’s roof (if we are really to believe that she’s seen them at all!) have to do with men’s and women’s sex acts. Men’s copulating with wanton women is the vice that anyone who knew her story – and knew the Admiral’s publicly preferred forms of viciousness – would assume she meant. It’s what Edmund would have believed Mary meant. It’s a dirty joke at the expense of her uncle that simultaneously reveals her own sexual knowingness, by association. Acknowledging that association in polite company would be more than enough to have Edmund feeling grave.

We’ll never know the extent to which Austen associated sodomy with the Navy men, but it seems to me very unlikely that she would have lost an opportunity in these lines to have Mary impugn the full range of vices in which the admiral and his peers indulged, while also making fun of their aging, and perhaps ungainly, rears. Given what the novel reveals – the adultery of the uncle and the attempted reform and adulterous repetition in the nephew – it seems clear that Mary (and Austen, in giving her voice) was making the most pointed reference in her pun to the heterosexual vices of powerful old Naval men, not to the illegal, punishable, same-sex vices of men’s rears. Even if it’s not about sodomy, Mary’s unsuccessful joke is a shocking moment of how forbidden sex undergirds this novel.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park. Coming soon: guest posts by Mary Lu Redden, Deborah Yaffe, Julie Strong, and Juliet McMaster. Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party!

June 20, 2014

A Gentleman’s Improvements: Mr. Rushworth, Humphry Repton, Fanny Price and Fashionable Landscaping

Seventh in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Maria Edgeworth, Image from Novels 1780-1920, Rare Books and Special Collections, University Library, University of Sydney

If you’ve been following “An Invitation to Mansfield Park” since the series began, you’ll remember that Jacqui Grainger contributed a post last month in which she reported on the fascinating symposium that explored “The Great Novels of 1814: Austen, Burney, Edgeworth and Scott.” Next month, she’ll tell us more about the Austen aspect of the exhibition on the “Great Novels of 1814” that she curated at the University of Sydney, where she is currently Manager of Rare Books and Special Collections. And today, I’m very pleased to share with you her analysis of the discussion in Chapter 6 of Mansfield Park about the proposed fate of the trees at Sotherton. Thank you, Jacqui, for all these contributions to the Mansfield Park celebrations!

Here’s Jacqui’s account of what inspired her to focus on this particular passage:

In the last few years I have found myself continually circling back to the section of Mansfield Park where Mr. Rushworth talks of his plans for ‘improvements’ at Sotherton. Whilst Librarian at Chawton House Library I curated an exhibition that complemented a talk I gave to the members of the Hampshire Gardens Trust; this became an article for one of their magazines. A version can be found here and I began with: ‘But the woods are fine, and there is a stream.’ In exploring the depth of materials on estates and gardens in both the Knight and the Main Collections at Chawton it seemed somewhat inevitable that I should begin with the first edition of Mansfield Park. Five years later in curating an exhibition on the ‘Great Novels of 1814: Austen, Burney, Edgeworth and Scott’ I seemed to be in very familiar territory because the collections here in Rare Books and Special Collections at the University of Sydney are predominantly those of eighteenth-century gentlemen: colonial legislators, officers of the navy and marines, naturalists, explorers, settlers and the more affluent transportees. There are sets of county antiquaries with ‘views of gentlemen’s seats,’ books by Humphrey Repton, John Loudon, Richard Payne Knight and William Cowper. This passage became central to the Austen section of the exhibition and led to a theme of place and identity throughout the exhibition.

Mr. Rushworth, however, though not usually a great talker, had still more to say on the subject next his heart. “Smith has not much above a hundred acres altogether in his grounds, which is little enough, and makes it more surprising that the place can have been so improved. Now at Sotherton, we have a good seven hundred, without reckoning the water meadows; so that I think, if so much can be done at Compton, we need not despair. There have been two or three fine old trees cut down, that grew too near the house, and it opens the prospect amazingly, which makes me think that Repton, or any body of that sort, would certainly have the avenue at Sotherton down; the avenue that leads from the west front to the top of the hill you know,” turning to Miss Bertram particularly as he spoke. But Miss Bertram thought it most becoming to reply:

“The avenue! Oh! I do not recollect it. I really know very little of Sotherton.”

“The avenue! Oh! I do not recollect it. I really know very little of Sotherton.”

Fanny, who was sitting on the other side of Edmund, exactly opposite Miss Crawford, and who had been attentively listening, now looked at him, and said in a low voice,

“Cut down an avenue! What a pity! Does it not make you think of Cowper? ‘Ye fallen avenues, once more I mourn your fate unmerited.’”

He smiled as he answered, “I am afraid the avenue stands a bad chance, Fanny.”

“I should like to see Sotherton before it is cut down, to see the place as it is now, in its old state; but I do not suppose I shall.”

“Have you never been there? No, you never can; and unluckily it is out of distance for a ride. I wish we could contrive it.”

“Oh! it does not signify. Whenever I do see it, you will tell me how it has been altered.”

“I collect,” said Miss Crawford, “that Sotherton is an old place, and a place of some grandeur. In any particular style of building?”

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 6 (Peterborough, ON: Broadview, 2001)

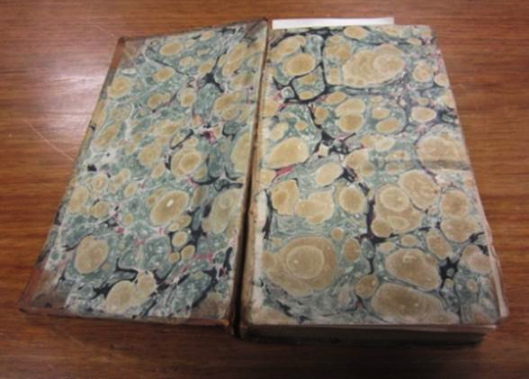

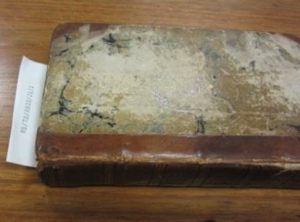

Photo of the first edition of Mansfield Park held at the University of Sydney, taken by the conservators. As you can see the volumes require some tender loving care and in the next few weeks conservation work will begin on them. The Jane Austen Society of Australia has pledged a contribution to their conservation along with the Friends of the Library and several individual donors. Image courtesy of Rare Books and Special Collections, University of Sydney Libraries.

Wealth and status, power and the responsible use of money are persistent themes in the work of Jane Austen. Austen uses the idea of improvement to reflect varying attitudes to money and its appropriate disposal.

Mr. Rushworth illustrates an extravagant readiness to dispose of his money in a demonstration of his wealth and status. A most fashionable young man, he plans to “improve” his estate according to the latest obsession in landscape design and the employment of Mr. Repton. Humphry Repton (1752-1818) refashioned the estates of the wealthy with dramatic scenic improvements like the example Rushworth gives: “two or three fine old trees cut down . . . and it opens up the prospect amazingly.”

As Rushworth’s estate is so much larger than the friend’s he is describing his expectation seems to be that anything Repton could do at Sotherton will be even more impressive. Simultaneously he displays his ignorance of Repton’s writing on the principles of landscape design in his treatises, Sketches and Hints on Landscape Gardening (1794), Observation on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1803), and An Inquiry into the Changes of Taste in Landscape Gardening (1806). Repton’s ideas were more subtle than Rushworth’s speculations and dealt with locations’ unique character.

In Rushworth’s speculations Austen ironically presents us with some of the criticism Repton had faced from Richard Payne Knight in The Landscape: a Didactic Poem (1794) and Uvedale Price in Essay on the Picturesque (1794). Both Knight and Price had opposed the ideas of Capability Brown (1716-1783) and other landscape designers, such as Repton, for being standardized and erasing the picturesque qualities of parks and gardens.

In Rushworth’s speculations Austen ironically presents us with some of the criticism Repton had faced from Richard Payne Knight in The Landscape: a Didactic Poem (1794) and Uvedale Price in Essay on the Picturesque (1794). Both Knight and Price had opposed the ideas of Capability Brown (1716-1783) and other landscape designers, such as Repton, for being standardized and erasing the picturesque qualities of parks and gardens.

Fanny’s whispered exclamation, “Cut down an avenue!”, mirrors the contemporary controversy on the picturesque and it is Cowper Fanny refers to, not Repton. Fanny’s concerns are Romantic – she longs to see it “in its old state.” She quotes from The Task: a Poem, in Six Books published by William Cowper in 1785; a poem in blank verse, The Task was extremely influential on Robert Burns, William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Charles Lamb, as well as Austen, with its writing of every day English life and the consolations of nature.

Miss Crawford’s interjection into the conversation brings it back from Fanny’s meagre consolations to the “grandeur” of Sotherton, Rushworth’s status as a wealthy landowner and what his plans to dispose of his money say about his character.

First edition of Mansfield Park. Image courtesy of Rare Books and Special Collections, University of Sydney Libraries.

Further reading:

Brooke, Christopher. Jane Austen: Illusion and Reality. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1999.

Butler, Marilyn. Jane Austen and the War of Ideas. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975.

Duckworth, Alistair. The Improvement of the Estate: a study of Jane Austen’s Novels. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins, 1971.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park .

June 13, 2014

Scattering Seeds of Kindness

Sixth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Mary C.M. Phillips writes about works by her favourite authors, Jane Austen and Edith Wharton, at Caffeine Epiphanies, and she recently co-hosted a discussion of Wharton’s life and works – including my own favourite, The Custom of the Country – at the Malverne Public Library in Malverne, New York. Her short stories and essays have appeared in numerous anthologies, such as Chicken Soup for the Soul, A Cup of Comfort, and Bad Austen: The Worst Stories Jane Never Wrote. Follow her on Twitter @MarycmPhil. I met Mary at the 2012 JASNA AGM in New York and have enjoyed many conversations with her about both Austen and Wharton since then. I’m very happy to introduce her guest post on Mary Crawford’s famous question about Fanny Price, “Pray, is she out, or is she not?”

“I begin now to understand you all, except Miss Price,” said Miss Crawford, as she was walking with the Mr. Bertrams. “Pray, is she out, or is she not? – I am puzzled. – She dined at the Parsonage, with the rest of you, which seemed like being out; and yet she says so little, that I can hardly suppose she is.”

Edmund, to whom this was chiefly addressed, replied, “I believe I know what you mean – but I will not undertake to answer the question. My cousin is grown up. She has the age and sense of a woman, but the outs and not outs are beyond me.”

“And yet, in general, nothing can be more easily ascertained. The distinction is so broad. Manners as well as appearance are, generally speaking, so totally different. Till now, I could not have supposed it possible to be mistaken as to a girl’s being out or not. A girl not out has always the same sort of dress; a close bonnet, for instance, looks very demure, and never says a word. You may smile – but it is so I assure you – and except that it is sometimes carried a little too far, it is all very proper. Girls should be quiet and modest. The most objectionable part is, that the alteration of manners on being introduced into company is frequently too sudden. They sometimes pass in such very little time from reserve to quite the opposite – to confidence! That is the faulty part of the present system. One does not like to see a girl of eighteen or nineteen so immediately up to every thing – and perhaps when one has seen her hardly able to speak the year before. Mr. Bertram, I dare say you have sometimes met with such changes.”

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 5 (London: Penguin, 1985)

Let us gather up the sunbeams,

Let us gather up the sunbeams,

Lying all around our path;

Let us keep the wheat and roses,

Casting out the thorns and chaff;

Let us find our sweetest comfort

In the blessings of today,

With a patient hand removing

All the briers from the way.

Then scatter seeds of kindness,

Then scatter seeds of kindness,

For our reaping by and by.

– May Riley Smith

Random acts of kindness may often come from the most unlikely of characters. An ambitious social climber might have a better eye for injustice than even the most sincere clergyman. To some, Mary Crawford, the charming antagonist of Mansfield Park, is considered shallow, immoral and unprincipled. But not to me. In my opinion, Mary Crawford is the radiant beacon that the Bertram family so desperately needs, shining a light on the character of Fanny Price.

“Pray, is she out, or is she not?” asks Mary in Chapter 5. “I am puzzled. She dined at the Parsonage, with the rest of you, which seemed like being out; and yet she says so little, that I can hardly suppose she is.”

Oh those heavenly words! I vividly remember my reaction to Mary’s words when I first read Mansfield Park. “Finally,” I rejoiced. “Someone has at long last taken notice of our poor Fanny. Someone has cast a warm light onto our pathetic heroine who continues to endure in an environment of insensitive frost.” Because, truth-be-told, that entire lot of Bertrams have blinded themselves to their own acts of injustice (and one has to wonder if Sir Thomas’s mysterious Antigua connection has somehow infected the entire family psyche).

Mary’s curious (and innocent) question plants a seed that will one day bear much fruit. Random acts of kindness are rooted in love and love is not meant to wither but to grow and spread and multiply. Mary’s act is one of compassion, like Miss Temple in Charlotte Brontë’s novel Jane Eyre, giving the poor orphan Jane Eyre a meal after a long trip. Miss Temple, unlike others, distinctly recognizes Jane’s suffering and takes immediate action. Just as Jesus cleanses the blind beggar’s eyes (Mark 10:46-52), Mary’s Crawford’s words have a profound cleansing effect on Edmund’s eyes. Until this moment, Edmund has not been able to see clearly. He has seen Fanny as a child. He has seen her as a quasi-family member. He has not, however, seen Fanny as a woman.

Mary’s question, “Pray, is she out, or is she not?”, results in Edmund’s acknowledgment that Fanny must be treated differently. As an adult. With compassion and kindness. Soon after this revelation, Edmund announces that Fanny must also be included in the visit to Sotherton – even if it means he will have to stay behind.

He then helps to arrange Fanny’s coming-out ball – a ball her dearly-loved brother attends, and at which this heroic brother puts all the other men in attendance to shame. This shame, I believe, is what leads Henry Crawford to feel his first pang of inferiority – a feeling that only Fanny’s respect and adoration would be able to cure.

From Mary’s one small seed of kindness (even if planted unintentionally), she awakens an entire family (excluding Mrs. Norris, of course, who is pure evil) and allows Fanny Price to grow into the woman she was always meant to be.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park .

June 6, 2014

Mary Crawford and the Mansfield “cure”

Fifth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

In Volume 3 of Mansfield Park, Sir Thomas decides to try a “medicinal project upon his niece’s understanding, which he must consider as at present diseased.” Living at Mansfield has, he believes, “disordered” Fanny Price’s “powers of comparing and judging,” and he sends her “home” to Portsmouth to be cured. This fall, Sara Malton is going to write about that passage – but today, Katie Davis explores a different “medicinal project” earlier in the novel, when Mrs. Grant proposes to Mary Crawford that Mansfield Park is the “cure,” rather than the cause of disease.

Katie is a Postdoctoral Fellow in Western Heritage at Carthage College in Kenosha, Wisconsin. She earned her Ph.D. in Literature from the University of Dallas in 2013, where she wrote a dissertation on Jane Austen’s Persuasion under the direction of Theresa Kenney (who’s writing about Tom and Edmund for my “Invitation to Mansfield Park” series). Katie is looking forward to celebrating the 200th anniversary of the publication of Mansfield Park with fellow Janeites at the JASNA AGM in Montreal this coming October, and I am, too. Registration opened yesterday, and Elaine Bander says more than 500 people have registered so far! Katie’s conference paper is entitled “Charles Pasley’s Essay and the ‘Governing Winds’ of Mansfield Park.” If you’re a JASNA member, you may have seen her essay on “Austen’s ‘Providence’ in Persuasion” in Persuasions 35, which arrived in my mailbox last week.

Katie is a Postdoctoral Fellow in Western Heritage at Carthage College in Kenosha, Wisconsin. She earned her Ph.D. in Literature from the University of Dallas in 2013, where she wrote a dissertation on Jane Austen’s Persuasion under the direction of Theresa Kenney (who’s writing about Tom and Edmund for my “Invitation to Mansfield Park” series). Katie is looking forward to celebrating the 200th anniversary of the publication of Mansfield Park with fellow Janeites at the JASNA AGM in Montreal this coming October, and I am, too. Registration opened yesterday, and Elaine Bander says more than 500 people have registered so far! Katie’s conference paper is entitled “Charles Pasley’s Essay and the ‘Governing Winds’ of Mansfield Park.” If you’re a JASNA member, you may have seen her essay on “Austen’s ‘Providence’ in Persuasion” in Persuasions 35, which arrived in my mailbox last week.

[Mrs. Grant to Mary Crawford] “You are as bad as your brother, Mary; but we will cure you both. Mansfield shall cure you both – and without any taking in. Stay with us and we will cure you.”

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 5 (New York: Norton, 1998)

Arthur Barbosa’s cover image for The Unknown Ajax, by Georgette Heyer, reminds Katie of Edmund Bertram and Mary Crawford http://www.lesleyannemcleod.com/rw_art.html#barbosa

When Mrs. Grant tells Mary and Henry Crawford that Mansfield might cure them, she suggests that their view of marriage is faulty. Mary has argued that all marriages involve one or the other of the spouses being “taken in.” Mrs. Grant rightly identifies the problem with Mary’s point of view: she has a corrupt imagination, and this imagination is leading her to form a one-sided, “evil” (meaning something like cynical in this case) opinion about marriage.

Mrs. Grant’s suggestion that Henry might be “cured” ultimately by marrying Julia Bertram (Chapter 4) shows that she does not know as much as we do – thanks to the narrator – about the imperfections of the Mansfield Park family. Julia is not as bad as Maria, but neither sister is equipped to bring about the “cure” Mrs. Grant hopes for.

Mrs. Grant’s suggestion that Henry might be “cured” ultimately by marrying Julia Bertram (Chapter 4) shows that she does not know as much as we do – thanks to the narrator – about the imperfections of the Mansfield Park family. Julia is not as bad as Maria, but neither sister is equipped to bring about the “cure” Mrs. Grant hopes for.

More importantly, neither Mary nor Henry is interested in what Mrs. Grant proposes: “The Crawfords, without wanting to be cured, were very willing to stay. Mary was satisfied with the parsonage as a present home, and Henry equally ready to lengthen his visit” (Chapter 5).

This brief passage in Chapter 5 calls our attention to a few of the central questions of Austen’s novel: to what extent can the opinions and habits of fully-formed adults be changed – or “cured” – by entering into community with people whose opinions and habits are, in crucial ways, totally different? What is required for such a transformation? Through this little exchange between Mrs. Grant and the Crawfords, Austen proposes that the will – corrupt or wholesome – is very real and extremely powerful. If Henry and Mary do not wish to be moved by their new friends, no amount of hoping on Mrs. Grant’s part will bring about the “cure.”

In the end, Mansfield does for Mary what Mrs. Grant wanted it to do: Mary’s time there does eventually “cure” her, but not in the way that Mrs. Grant had expected:

Arthur Barbosa, “A Riding Habit,” from Georgette Heyer’s Regency England, by Teresa Chris (London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1989).

Mrs. Grant, with a temper to love and be loved, must have gone [from Mansfield to London for Dr. Grant’s new position] with some regret, from the scenes and people she had been used to; but the same happiness of disposition must in any place and any society, secure her a great deal to enjoy, and she had again a home to offer Mary; and Mary had had enough of her own friends, enough of vanity, ambition, love, and disappointment in the course of the last half year, to be in need of the true kindness of her sister’s heart, and the rational tranquility of her ways. . . . Mary, though perfectly resolved against ever attaching herself to a younger brother again, was long in finding . . . any one who could satisfy the better taste she had acquired at Mansfield, whose character and manners could authorise a hope of the domestic happiness she had there learnt to estimate, or put Edmund Bertram sufficiently out of her head. (Chapter 48; Vol. 3, Ch. 17)

“[L]ong in finding” is better than the turn Persuasion’s narrator gives Elizabeth Elliot, to whom “no one of proper condition has since presented himself” (Vol. II, Ch. 24). Ultimately, it is love – Mrs. Grant’s enduring love and affection for Mary, and belatedly, Edmund’s good-hearted, thorny, thwarted love for Mary – that effects the change in Mary. Mary will never be satisfied with anything less once she has encountered this type of love at Mansfield. Austen enacts the theme of felix culpa here: Mary’s “evil” imagination could only be transformed by something as powerful as a broken heart, but thanks to that heartache, she has hope, eventually, of the “domestic happiness” that Mrs. Grant wanted for her all along.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park .

May 30, 2014

Why Tom Bertram is right that Dr. Grant will “soon pop off”

Fourth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Tom Bertram predicts the death of Dr. Grant in the third chapter of Mansfield Park. His death would be convenient in that it would allow Edmund Bertram to become the clergyman at Mansfield, but how does Tom know that this “hearty man of forty-five” won’t live long – and how does Jane Austen know? Dr. Cheryl Kinney, who is one of the “Best Doctors in America” (she’s made the list annually since 2001) and a Board Member of the Jane Austen Society of North America, answers this question in today’s guest post.

Dr. Kinney is a gynecologist in Dallas, Texas, and she was one of the coordinators of the 2011 JASNA AGM in Fort Worth, “200 Years of Sense and Sensibility.” In addition to her private practice, she has volunteered with Project Access, providing care to uninsured and financially marginalized women throughout the Dallas area. She’s been named by the Consumers’ Research Council as one of “America’s Top Obstetricians and Gynecologists” yearly since 2002, and has been named a “Texas Super Doctor” by her peers for the last ten years. Cheryl has lectured extensively to various groups in the Dallas/Fort Worth area on issues relating to gynaecology, including menopause, sexual dysfunction, endometriosis, and pelvic surgery, and she has also lectured all over the United States, Canada, and England on women’s health in the novels of Jane Austen and other 18th and 19th century British authors. It’s my pleasure to introduce her post on Dr. Grant and the risk factors for sudden death.

Dr. Kinney is a gynecologist in Dallas, Texas, and she was one of the coordinators of the 2011 JASNA AGM in Fort Worth, “200 Years of Sense and Sensibility.” In addition to her private practice, she has volunteered with Project Access, providing care to uninsured and financially marginalized women throughout the Dallas area. She’s been named by the Consumers’ Research Council as one of “America’s Top Obstetricians and Gynecologists” yearly since 2002, and has been named a “Texas Super Doctor” by her peers for the last ten years. Cheryl has lectured extensively to various groups in the Dallas/Fort Worth area on issues relating to gynaecology, including menopause, sexual dysfunction, endometriosis, and pelvic surgery, and she has also lectured all over the United States, Canada, and England on women’s health in the novels of Jane Austen and other 18th and 19th century British authors. It’s my pleasure to introduce her post on Dr. Grant and the risk factors for sudden death.

Tom listened with some shame and some sorrow; but escaping as quickly as possible, could soon with cheerful selfishness reflect, firstly, that he had not been half so much in debt as some of his friends; secondly, that his father had made a most tiresome piece of work of it; and, thirdly, that the future incumbent, whoever he might be, would, in all probability, die very soon.

On Mr. Norris’s death the presentation became the right of a Dr. Grant, who came consequently to reside at Mansfield; and on proving to be a hearty man of forty-five, seemed likely to disappoint Mr. Bertram’s calculations. But “no, he was a short-necked, apoplectic sort of fellow, and, plied well with good things, would soon pop off.”

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 3 (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2005)

The English Parsonage in the Early Nineteenth Century, by Timothy Brittain-Catlin

In Jane Austen’s time sickness and suffering were part of everyday life and because Jane Austen wrote about everyday life, illness and injury permeate her novels. Perhaps better than anyone, she made use of these bodily events to develop her characters and drive her plots. In Chapter 3 of Mansfield Park, Austen uses Mr. Norris’ death to not only move Mrs. Norris to Mansfield proper, but to move the Grants into Mansfield Parsonage, to position the Crawfords to their advantage, and to disclose Tom’s culpability (and lack of remorse) in robbing Edmund of a portion of his living.

But to regard Jane Austen’s use of illness, injury, and death as mere plot mechanics is to deny the extraordinary precision with which she constructed her stories. She brilliantly used fictive ills metaphorically to expose strengths and weaknesses of human nature, as well as thematically to reinforce the maxim that permeates all of her novels: if we do not behave ourselves properly, something bad is bound to happen. Allowing her to accomplish these artistic goals was a remarkable understanding of the human body.

When Tom Bertram is confronted with his responsibility in the loss of the parsonage living for Edmund, he responds that Dr. Grant “plied well with good things, would soon pop off.” Despite being “a hearty man of forty-five,” Dr. Grant does indeed die a sudden death from gluttony.

Today, we are all aware of the association between a high fat diet and heart attack and stroke. In Regency England, however, most doctors had no idea what caused sudden death. Review of the medical literature from 1708 until 1919 reveals suspected etiologies that included cold weather, a thick neck, tight clothing, constipation, long stooping, warm baths, debauchery and “the venereal act.” A high fat diet was rarely included on the list of possible causes.

One of Dr. Quain’s drawings of a fatty heart

Although Hippocrates stated that very fat persons were apt to die earlier than those who were slender, it wasn’t until 1850, when Sir Richard Quain described the possible association between deposition of fat around the heart and sudden death, that high fat diets were seriously implicated. Quain’s fatty heart became a commonplace diagnosis in Victorian England – in George Eliot’s Middlemarch, young Dr. Lydgate diagnoses fatty degeneration of the heart in a patient who becomes short of breath – and firmly established Dr. Quain’s reputation as the leading authority on heart disease.

Dr. Quain’s paper is still consider a major milestone in the study of heart and blood vessel pathology, but is recognized as having a serious error in that it failed to identify the essential causes of the condition. In the entire paper (seventy-five pages) there is only one paragraph that remarks on the part a high fat diet might play on the formation of the disorder. The paragraph ends with the disclaimer “Beyond these general principles I fear we cannot go, and even to these there are exceptions.”

Another of Dr. Quain’s drawings of a fatty heart

It would not be until the next century that the association between diet and sudden death was firmly and scientifically established. Jane Austen, without formal medical training, required no such length of time to come to the correct medical conclusion – that people who must have their “palate consulted in everything” (Chapter 11) and who indulge in “three great institutionary dinners in one week” (Chapter 48) would be at risk to suffer apoplexy and death.

In the ending paragraphs of the novel, Jane Austen uses Dr. Grant’s death to expose Sir Thomas’ and Edmund’s hypocritical defense of the clergy with their stance on multiple incumbencies. The death also reveals that both Fanny and Edmund could fall prey to the very mercenary motives that they found so reprehensible in Mary Crawford: a larger income and a bigger house – “. . . the acquisition of Mansfield living, by the death of Dr. Grant, occurred just after they had been married long enough to begin to want an increase of income, and feel their distance from the paternal abode an inconvenience.” There is the genius of Jane Austen.

It is a testament to her greatness that Jane Austen was able to accomplish so many artistic and thematic goals while remaining faithful to the properties of an actual disease process that would not be clearly understood until the next century.

References:

Barie, E (1912) Traie Pratique des Maladies du Coeur et de l’Aorte, 3rd edition, p. 1125, Paris, Vigot frères.

Bedford, E (1972) The story of fatty heart: A disease of Victorian times, British Heart Journal, 34: 23-28.

Buchan, W (1772) Domestic Medicine: or, a Treatise on the Prevention and Cure of Disease by Regimen and Simple Medicines, London.

Cheyne, J (1812) Causes of Apoplexy and Lethargy: with observations upon the comatose disease, London, Thomas Underwood.

Corvisart, J (1806) Essai sur les Maladies et les Lesions Organiques du Coeur et des Gros Vaisseaux, Paris, Migneret.

Fothergill, J (1879) The Heart and its Diseases, 2nd edition, London, Lewis.

Hayden, T (1875) The Diseases of the Heart and Aorta, Dublin, Fannin & Company.

Herrick, J (1919) Thrombosis of the coronary arteries, Journal of the American Medical Association, 72: 387.

Ljunggren B, Fodstad H (1991) History of stroke, Neurosurgery, 28: 482.

Morgan, A. (1968) Some forms of undiagnosed coronary disease in nineteenth-century England, Medical History, 12: 344-356.

Paget, J (1847) Lectures on nutrition, hypertrophy, and atrophy, London Medical Gazette, 5: 227.

Porter, R and D (1988) In Sickness and in Health: The British Experience 1650-1850, London, Fourth Estate.

Pound P, Bury M, Ebrahim S (1997) From apoplexy to stroke, Age and Aging, 26: 331-337.

Quain, R (1850) Fatty diseases of the heart, Medico-Chirurgical Transactions, 33: 121-196.

Quain, R (1850) Fatty diseases of the heart, Medico-Chirurgical Transactions, 33: 121-196.

Robinson, N (1732), A Discourse upon the Nature and Cause of Sudden Death, London, T. Warner.

Sprengell, C (1708) The Aphorisms of Hippocrates and the Sentences of Celsus, London, R. Botwick.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park .

May 23, 2014

First Impressions of Fanny Price

Third in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Jennie Duke and I share a fascination with the way Jane Austen introduces Fanny Price as a child in the second chapter of Mansfield Park. We get a glimpse of Catherine Morland’s infancy and girlhood (though by the second paragraph of Northanger Abbey she’s fifteen), and we get to hear about the many reading lists Emma Woodhouse draws up for herself as a teenager, but we don’t get to read longer scenes from their childhoods or those of Austen’s other heroines. (What do you think Lady Susan would have been like at the age of ten – has anyone written that prequel yet?)

Jennie and I are also both interested in the so-called “Jane-a-Day” five-year journal (“With 365 Witticisms by Jane Austen”), which provides a few blank lines for each day of the year so that if you write something every day, you’ll be able to look back and compare what you were doing every year on May 23rd, say, over the past five years. Jennie is doing a much better job than I am of keeping up this “delightful habit of journaling” (Northanger Abbey, Chapter 3) and she tells me she often records quotations relevant to what’s happening in her life. My own approach is more haphazard, and while I’ve sometimes made entries for a few weeks at a time over the last couple of years since my dear friend Lisa Doucet gave me this lovely journal, I’m sorry to report that I haven’t yet recorded anything for May 23rd.

Jennie and I are also both interested in the so-called “Jane-a-Day” five-year journal (“With 365 Witticisms by Jane Austen”), which provides a few blank lines for each day of the year so that if you write something every day, you’ll be able to look back and compare what you were doing every year on May 23rd, say, over the past five years. Jennie is doing a much better job than I am of keeping up this “delightful habit of journaling” (Northanger Abbey, Chapter 3) and she tells me she often records quotations relevant to what’s happening in her life. My own approach is more haphazard, and while I’ve sometimes made entries for a few weeks at a time over the last couple of years since my dear friend Lisa Doucet gave me this lovely journal, I’m sorry to report that I haven’t yet recorded anything for May 23rd.

Today, however, I can record that Jennie has written about Fanny Price’s childhood for “An Invitation to Mansfield Park,” so that I can look back on this day in the next few years as we celebrate 200 years of Emma, Persuasion, and Northanger Abbey. Jennie writes about Pride and Prejudice at The Bennet Sisters (for love) and is editor of Property Observer (for work and love). She’s based in Melbourne, Australia, and I’m happy to introduce her post on Fanny Price at age ten.

Fanny Price was at this time just ten years old, and though there might not be much in her first appearance to captivate, there was, at least, nothing to disgust her relations. She was small of her age, with no glow of complexion, nor any other striking beauty; exceedingly timid and shy, and shrinking from notice; but her air, though awkward, was not vulgar, her voice was sweet, and when she spoke her countenance was pretty.

- From Mansfield Park, Chapter 2 (London: Vintage, 2008)

Joan Hassall’s illustration of Edmund comforting young Fanny (from http://www.pemberley.com/janeinfo/jabrokil.html)

I can’t help but feel that this description of Fanny Price is very insulting – with “nothing to disgust,” “no glow,” the description is largely about what she is not. To be deficient in either “striking beauty” or captivating appearance clearly points out what other people value and suggests that she falls below some socially valued benchmark. For a heroine at the age of ten, this is some fairly hefty judgment indeed.

It’s a fascinating description because of everything it lacks, particularly when you compare it with the treatment of Austen’s other heroines. Emma Woodhouse, “handsome, clever and rich,” is clearly defined, with strong words. On the other hand, Fanny Price has no glow of complexion and is exceedingly timid and shy, and she shrinks from notice, but is able to be steadfast and strict about her ethics and beliefs in a way few other heroines are.

Austen’s decision to focus on Fanny at such a young age, ten years old, at a point when she has had little opportunity to learn or grow, is a bold one that she does not force upon her other heroines. Emma is brought to our notice during her twenties, fully formed and strong – although we later learn that she has been given responsibility from age twelve as mistress of the house. We also learn of Emma that “At ten years old she had the misfortune of being able to answer questions which puzzled her sister at seventeen.”

Other Austen heroines are usually described in relation to others and their family situations, and introduced with far less fanfare. Sarah has written about the way Austen introduces Elizabeth and other Pride and Prejudice characters, and she shows how slowly some of the information is revealed in that novel.

Which brings me back to Emma and Fanny, as they are described using the same technique, but to vastly different effect. Emma and Fanny are stark opposites in character, and yet Fanny, much like Emma, is largely alone. While Emma’s solitude is based on her higher position in life and independence from her father in his home, Fanny’s solitude is due to her entirely opposite situation and reliance on a household she has no place in.

Which brings me back to Emma and Fanny, as they are described using the same technique, but to vastly different effect. Emma and Fanny are stark opposites in character, and yet Fanny, much like Emma, is largely alone. While Emma’s solitude is based on her higher position in life and independence from her father in his home, Fanny’s solitude is due to her entirely opposite situation and reliance on a household she has no place in.

In the end, we are left wondering why she wasn’t described as Catherine Morland is, in Northanger Abbey: “No one who had ever seen Catherine Morland in her infancy would have supposed her born to be an heroine.” Jane Austen often suggests we shouldn’t judge anything at its first appearance. Where Emma appears confident and vibrant, we see her needing to take the longest journey of all the heroines, and where Fanny appears to be the most wilting and unattractive of all, she takes a shorter journey. She’s much stronger than Emma, even though that certainly isn’t apparent at first.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park .

May 16, 2014

Adopting Affection

Second in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

You’ll soon notice that many of the contributors to this series are from Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, where I was a graduate student. Lyn Bennett, who wrote last week’s post on the opening paragraph of Mansfield Park, was in the PhD program with me, for example. The other contributors with connections to Dalhousie and/or its near neighbour, the University of King’s College, are Maggie Arnold, John Baxter, Elizabeth Baxter, Hugh Kindred, and the author of today’s post, Judith Thompson. It was in one of Judith’s classes that I first fell in love with Jane Austen’s novels. I had read Pride and Prejudice and Northanger Abbey as a teenager, but it wasn’t until I read Sense and Sensibility and discussed it in this class that I saw just how brilliant Austen’s fiction is. Thanks, Judith!

You’ll soon notice that many of the contributors to this series are from Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, where I was a graduate student. Lyn Bennett, who wrote last week’s post on the opening paragraph of Mansfield Park, was in the PhD program with me, for example. The other contributors with connections to Dalhousie and/or its near neighbour, the University of King’s College, are Maggie Arnold, John Baxter, Elizabeth Baxter, Hugh Kindred, and the author of today’s post, Judith Thompson. It was in one of Judith’s classes that I first fell in love with Jane Austen’s novels. I had read Pride and Prejudice and Northanger Abbey as a teenager, but it wasn’t until I read Sense and Sensibility and discussed it in this class that I saw just how brilliant Austen’s fiction is. Thanks, Judith!

Judith Thompson is a professor of English Romantic Literature at Dalhousie, official archivist of the John Thelwall Society, and a leader in the rapidly-growing field of Thelwall Studies. She’s the author of John Thelwall in the Wordsworth Circle: The Silenced Partner (Palgrave, 2012), (co) editor of Thelwall’s The Peripatetic (Wayne State, 2001) and The Daughter of Adoption (Broadview, 2013) and she’s currently editing the first modern edition of Thelwall’s Selected Poetry and Poetics. She says that while she’s devoted her research career to reviving the legacy of this radical romantic, “acquitted felon” and eccentric polymath, she also has a strong teaching interest in Romantic women’s writing, and offers classes in everything from poetic voice to postmodern fiction.

Judith Thompson is a professor of English Romantic Literature at Dalhousie, official archivist of the John Thelwall Society, and a leader in the rapidly-growing field of Thelwall Studies. She’s the author of John Thelwall in the Wordsworth Circle: The Silenced Partner (Palgrave, 2012), (co) editor of Thelwall’s The Peripatetic (Wayne State, 2001) and The Daughter of Adoption (Broadview, 2013) and she’s currently editing the first modern edition of Thelwall’s Selected Poetry and Poetics. She says that while she’s devoted her research career to reviving the legacy of this radical romantic, “acquitted felon” and eccentric polymath, she also has a strong teaching interest in Romantic women’s writing, and offers classes in everything from poetic voice to postmodern fiction.

I have a secret to confess. I’ve always liked Fanny Price, even though she is generally agreed to be the most tight-ass heroine of the most conservative novelist of the romantic era, whereas I’m passionately in love with one of that era’s most kick-ass revolutionaries, the radical activist and atheist John Thelwall. But I’m not really betraying him by writing this blog post, because I’ve always suspected that there’s more to Fanny, and her creator, than there appears. One need not turn Austen’s mousy heroine into a cheeky ironist (a la Patricia Rozema) or a sullen rebel (a la Billie Piper), to find something appealing in her introverted independence, unshakeable integrity and undemonstrative opposition to the follies of her cousins. One need only recognize that, like her author, she takes in a lot more than she lets on.

Recently I had occasion to revisit the adopted daughter of the Bertram family, in order to help me contextualize an edition of Thelwall’s novel The Daughter of Adoption, published 13 years before Mansfield Park. And strangely I found much to compare between the two narratives. Though Thelwall’s Seraphina is an outspoken Wollstonecraftian Creole who challenges and overturns the slaveowning patriarchal system, and Austen’s Fanny is a cowering English country-mouse who seems content to submit to classbound hierarchies and traditional moral codes, both novels share several plot elements and even some characters with the same names and natures. Perhaps this is because both draw from a common source in Burney’s Evelina, though it is not impossible that Austen had read Thelwall’s Daughter: it was published under a pseudonym, and she read a lot more than she let on, too.

Recently I had occasion to revisit the adopted daughter of the Bertram family, in order to help me contextualize an edition of Thelwall’s novel The Daughter of Adoption, published 13 years before Mansfield Park. And strangely I found much to compare between the two narratives. Though Thelwall’s Seraphina is an outspoken Wollstonecraftian Creole who challenges and overturns the slaveowning patriarchal system, and Austen’s Fanny is a cowering English country-mouse who seems content to submit to classbound hierarchies and traditional moral codes, both novels share several plot elements and even some characters with the same names and natures. Perhaps this is because both draw from a common source in Burney’s Evelina, though it is not impossible that Austen had read Thelwall’s Daughter: it was published under a pseudonym, and she read a lot more than she let on, too.

But I’m getting ahead of myself; the purpose of this post is not to undertake a comparison, and far less to promote my edition of Thelwall (though of course you should all read The Daughter of Adoption, available in an accessible Broadview edition here). Instead it is to say a few words about my chosen passage, which provides the main impetus for the adoption plot of Mansfield Park, taking up the middle of Chapter 1. Here Mrs. Norris proposes that they do something to help her poor sister, “reliev[ing her] from the charge and expense of one child entirely out of her great number” by “undertak[ing] the care of her eldest daughter.” It is not easily excerpted, because it extends over several pages, in a debate (ever so proper but full of Austen’s ironies) that also introduces stiff Sir Thomas and his busybody sister-in-law. Here is the core of it:

Sir Thomas could not give so instantaneous and unqualified a consent. He debated and hesitated; — it was a serious charge; — a girl so brought up must be adequately provided for, or there would be cruelty instead of kindness in taking her from her family. He thought of his own four children, of his two sons, of cousins in love, etc.; — but no sooner had he deliberately begun to state his objections, than Mrs. Norris interrupted him with a reply to them all, whether stated or not.

“My dear Sir Thomas, I perfectly comprehend you, and do justice to the generosity and delicacy of your notions, which indeed are quite of a piece with your general conduct; and I entirely agree with you in the main as to the propriety of doing everything one could by way of providing for a child one had in a manner taken into one’s own hands; and I am sure I should be the last person in the world to withhold my mite upon such an occasion. Having no children of my own, who should I look to in any little matter I may ever have to bestow, but the children of my sisters? – and I am sure Mr. Norris is too just – but you know I am a woman of few words and professions. Do not let us be frightened from a good deed by a trifle. Give a girl an education, and introduce her properly into the world, and ten to one but she has the means of settling well, without farther expense to anybody. A niece of ours, Sir Thomas, I may say, or at least of yours, would not grow up in this neighbourhood without many advantages. I don’t say she would be so handsome as her cousins. I dare say she would not; but she would be introduced into the society of this country under such very favourable circumstances as, in all human probability, would get her a creditable establishment. You are thinking of your sons – but do not you know that, of all things upon earth, that is the least likely to happen, brought up as they would be, always together like brothers and sisters? It is morally impossible. I never knew an instance of it. It is, in fact, the only sure way of providing against the connexion. Suppose her a pretty girl, and seen by Tom or Edmund for the first time seven years hence, and I dare say there would be mischief. The very idea of her having been suffered to grow up at a distance from us all in poverty and neglect, would be enough to make either of the dear, sweet-tempered boys in love with her. But breed her up with them from this time, and suppose her even to have the beauty of an angel, and she will never be more to either than a sister.”

“My dear Sir Thomas, I perfectly comprehend you, and do justice to the generosity and delicacy of your notions, which indeed are quite of a piece with your general conduct; and I entirely agree with you in the main as to the propriety of doing everything one could by way of providing for a child one had in a manner taken into one’s own hands; and I am sure I should be the last person in the world to withhold my mite upon such an occasion. Having no children of my own, who should I look to in any little matter I may ever have to bestow, but the children of my sisters? – and I am sure Mr. Norris is too just – but you know I am a woman of few words and professions. Do not let us be frightened from a good deed by a trifle. Give a girl an education, and introduce her properly into the world, and ten to one but she has the means of settling well, without farther expense to anybody. A niece of ours, Sir Thomas, I may say, or at least of yours, would not grow up in this neighbourhood without many advantages. I don’t say she would be so handsome as her cousins. I dare say she would not; but she would be introduced into the society of this country under such very favourable circumstances as, in all human probability, would get her a creditable establishment. You are thinking of your sons – but do not you know that, of all things upon earth, that is the least likely to happen, brought up as they would be, always together like brothers and sisters? It is morally impossible. I never knew an instance of it. It is, in fact, the only sure way of providing against the connexion. Suppose her a pretty girl, and seen by Tom or Edmund for the first time seven years hence, and I dare say there would be mischief. The very idea of her having been suffered to grow up at a distance from us all in poverty and neglect, would be enough to make either of the dear, sweet-tempered boys in love with her. But breed her up with them from this time, and suppose her even to have the beauty of an angel, and she will never be more to either than a sister.”

“There is a great deal of truth in what you say,” replied Sir Thomas, “and far be it from me to throw any fanciful impediment in the way of a plan which would be so consistent with the relative situations of each. I only meant to observe that it ought not to be lightly engaged in, and that to make it really serviceable to Mrs. Price, and creditable to ourselves, we must secure to the child, or consider ourselves engaged to secure to her hereafter, as circumstances may arise, the provision of a gentlewoman, if no such establishment should offer as you are so sanguine in expecting.”

“There is a great deal of truth in what you say,” replied Sir Thomas, “and far be it from me to throw any fanciful impediment in the way of a plan which would be so consistent with the relative situations of each. I only meant to observe that it ought not to be lightly engaged in, and that to make it really serviceable to Mrs. Price, and creditable to ourselves, we must secure to the child, or consider ourselves engaged to secure to her hereafter, as circumstances may arise, the provision of a gentlewoman, if no such establishment should offer as you are so sanguine in expecting.”

“I thoroughly understand you,” cried Mrs. Norris, “you are everything that is generous and considerate, and I am sure we shall never disagree on this point. Whatever I can do, as you well know, I am always ready enough to do for the good of those I love; and, though I could never feel for this little girl the hundredth part of the regard I bear your own dear children, nor consider her, in any respect, so much my own, I should hate myself if I were capable of neglecting her. Is not she a sister’s child? and could I bear to see her want while I had a bit of bread to give her? My dear Sir Thomas, with all my faults I have a warm heart; and, poor as I am, would rather deny myself the necessaries of life than do an ungenerous thing. So, if you are not against it, I will write to my poor sister tomorrow, and make the proposal; and, as soon as matters are settled, I will engage to get the child to Mansfield; you shall have no trouble about it. My own trouble, you know, I never regard. I will send Nanny to London on purpose, and she may have a bed at her cousin the saddler’s, and the child be appointed to meet her there. They may easily get her from Portsmouth to town by the coach, under the care of any creditable person that may chance to be going. I dare say there is always some reputable tradesman’s wife or other going up.”

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 1 (New York: Oxford, 2008)

What no doubt strikes the modern reader is how little concern is shown for the emotional needs of the adoptee, as either a child or an individual (note, for instance, that her name is never mentioned). Sir Thomas at least begins by thinking about kindness to her, but this is undercut by self-interest and social propriety (what would be “consistent with the relative situations of each”). The word “love” is used only in relation to his immediate family, and betrays his intense class anxiety: one of his boys might violate social hierarchies by falling in love with his lowly cousin.

Mrs. Norris, on the other hand, despite her longwinded protestations, is motivated by nothing but financial self-interest; any words of emotion she uses (“generosity,” kind heart,” repeating Sir Thomas’ fear of “love”) are entirely insincere and calculated to flatter either him or herself. Although she may seem progressive in suggesting that it is important to “give a girl an education,” the only female independence she really cares about is her own freedom from responsibility. Her true attitude to her niece is neatly revealed, with typical Austen irony, at the end of each of her speeches. In the first of these she equates the unnamed child with an animal (“breed her up with them” is a devastating comment on Sir Thomas’ anxiety about good breeding). In the second she treats her like a package to be sent from Portsmouth “with any creditable person that may chance to be going” (here again the repetition of a word initially used by Sir Thomas reveals the bottom-line mentality that lies beneath the aristocratic facade).

Although such unfeeling calculation may be shocking to us, it is entirely consistent with what we know the history of adoption, which, surprisingly, was not actually legal in England until the 1920s. Before that, like Sir Thomas, English common law insisted upon the primacy of bloodlines, property and primogeniture. While informal adoptions and wardships like the ones being negotiated here had always existed, adoption was primarily a mechanism to gain advantage (whether cheap labour or moral credit) for the adopter, rather than a way of ensuring the adoptee’s well-being.

As Marianne Novy, chief historian of the English adoption novel, points out, the slow move towards more humanitarian adoption in England began with the institution of the London Foundling Hospital in the mid 18th century, closely connected to the development of the novel through the work of Henry Fielding, one of its sponsors. Fielding’s Tom Jones is of course the classic English adoption novel, whereby a foundling is taken in by a noble family, but always suspected of “bad blood” and ultimately cast out, until, after overcoming many obstacles (including various surrogate parents) he discovers that he really IS related by blood to his Allworthy father. In the case of the female bildungsroman, for example Fanny Burney’s Evelina, the adopted daughter is typically more timid and trammeled by social convention, but she endures and overcomes similar stigmas and surrogates before the novel ends with her aristocratic father “owning” her (a word whose dual meanings Burney exploits to highlight the tension between bonds of affection and mere financial obligations).

As Marianne Novy, chief historian of the English adoption novel, points out, the slow move towards more humanitarian adoption in England began with the institution of the London Foundling Hospital in the mid 18th century, closely connected to the development of the novel through the work of Henry Fielding, one of its sponsors. Fielding’s Tom Jones is of course the classic English adoption novel, whereby a foundling is taken in by a noble family, but always suspected of “bad blood” and ultimately cast out, until, after overcoming many obstacles (including various surrogate parents) he discovers that he really IS related by blood to his Allworthy father. In the case of the female bildungsroman, for example Fanny Burney’s Evelina, the adopted daughter is typically more timid and trammeled by social convention, but she endures and overcomes similar stigmas and surrogates before the novel ends with her aristocratic father “owning” her (a word whose dual meanings Burney exploits to highlight the tension between bonds of affection and mere financial obligations).

It is that same tension between affection, economic self-interest and “noblesse oblige” that lies at the heart of the (heartless) exchange between Sir Thomas and Mrs. Norris, and defines the adoption plot of Mansfield Park. Fanny is a lot like Evelina: intimidated by the false, fashionable world of her adopted family, she is unable to assert herself even though she recognizes and resists its pretense. Yet ultimately, even more than Burney’s heroine, Fanny prevails: the great irony of the novel is that the lowly adopted daughter is more loyal to Sir Thomas than his dishonoured birth daughters, and he not only recognizes this but reorients his family around her.

It is that same tension between affection, economic self-interest and “noblesse oblige” that lies at the heart of the (heartless) exchange between Sir Thomas and Mrs. Norris, and defines the adoption plot of Mansfield Park. Fanny is a lot like Evelina: intimidated by the false, fashionable world of her adopted family, she is unable to assert herself even though she recognizes and resists its pretense. Yet ultimately, even more than Burney’s heroine, Fanny prevails: the great irony of the novel is that the lowly adopted daughter is more loyal to Sir Thomas than his dishonoured birth daughters, and he not only recognizes this but reorients his family around her.

Of course the meaning of that irony has been a matter of much debate. Does Austen use adoption to challenge and reform the aristocratic patriarchal family from below (as Easton suggests), or does it serve as a kind of organic Burkean grafting that strengthens the bloodline, thereby retrenching aristocratic privilege and power (as Tuite maintains)?

This is not the place to engage such debate. I’ll simply end by returning to the importance of affection in this novel of adoption. Ultimately, all of Fanny’s inflexible integrity adds up to a strong preference for the one person (Edmund) who gives her what is so lacking in that opening passage. She simply, single-mindedly stands firm and waits until her affection can be reciprocated. Mutual love is her moral law, and by the end of the novel, the family adopts that law as its own.

This is not the place to engage such debate. I’ll simply end by returning to the importance of affection in this novel of adoption. Ultimately, all of Fanny’s inflexible integrity adds up to a strong preference for the one person (Edmund) who gives her what is so lacking in that opening passage. She simply, single-mindedly stands firm and waits until her affection can be reciprocated. Mutual love is her moral law, and by the end of the novel, the family adopts that law as its own.

Which brings me back to Thelwall. For it is here that Fanny is most like Thelwall’s heroine, Seraphina, who for all her independence and assertiveness, also withdraws from the deceptive, soul-destroying world of fashion, and holds firm, forcing another dysfunctional, slave-owning aristocratic family to reshape itself according to her unshakeable values, of which the chief is mutual affection. At the end of the novel she asserts the moral of the story: “they build a family indeed, good doctor, who bring them up in social equality and reciprocal love.” Austen might or might not agree with the social equality part, but when it comes to daughters of adoption, the demure conservative and the fiery radical come together under the banner of reciprocal love.

Sources:

Austen, Jane. Mansfield Park. New York: Oxford UP, 2008.

Easton, Fraser. “The Political Economy of Mansfield Park: Fanny Price and the Atlantic Working Class,” Textual Practice 12.3 (1998): 459-488.

Novy, Marianne. Reading Adoption: Family and Difference in Fiction and Drama. Ann Arbor: U Michigan P, 2004.

Thelwall, John. The Daughter of Adoption. Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview, 2012.

Tuite, Clara. Romantic Austen: Sexual Politics and the Literary Canon. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2002.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park .

May 9, 2014

Clarity and Complexity: Mansfield Park Begins

Happy 200th anniversary to Mansfield Park, published on this day in 1814. Mansfield Park is not as famous as Jane Austen’s “darling child” Pride and Prejudice, but it’s still beloved, and the celebrations are just beginning. Please join us here every Friday this year as we read the novel together – open “Your Invitation to Mansfield Park” for more details.

I’m very happy to introduce Lyn Bennett’s guest post on the opening paragraph of Mansfield Park. Lyn is an Associate Professor at Dalhousie University, where she teaches classes in rhetoric, writing, and close reading. As well as Women Writing of Divinest Things (Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 2004), she has published numerous articles on topics rhetorical and literary, from public discourse in Interregnum England, to interdisciplinarity in literary studies, to the critical reception of Edith Wharton. (Hooray for Edith Wharton!) Her current research focuses on medicine, illness, and the 17th-century writer, considering the work of non-medical writers as well as the physicians who gave discursive shape to the profession that would come to dominate medicine by century’s end. She is also an avid gardener who likes the country almost as much as Jane Austen.