Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 32

October 6, 2014

Mansfield Park in Montreal!

There are so many reasons to be excited about this year’s JASNA AGM. It focuses on Mansfield Park, which is a brilliant book, it’s in Montreal, which is a fabulous city, and, like all JASNA AGMs, it’s an opportunity to analyze and celebrate Austen’s writing with a wonderful group of very smart people.

Several of the contributors to “An Invitation to Mansfield Park” will be speaking at the AGM this weekend, including Juliet McMaster, Lynn Festa, Lorrie Clark, and Kathryn Davis (whose guest posts you can find listed here), Natasha Duquette (whose guest post will be published this Friday, October 10th), and Elisabeth Lenckos, Theresa Kenney, Sheryl Craig, and Sheila Johnson Kindred (whose guest posts will appear on the blog over the next few months). Sheila and I are presenting together on Saturday – our talk is called “Among the Proto-Janeites: Reading Mansfield Park for Consolation in Halifax, Nova Scotia in 1815.” Several other contributors are attending the AGM, too: Deborah Barnum, Karen Doornebos, Margaret Horwitz, Hugh Kindred, Cheryl Kinney, Amy Patterson, Julie Strong, Margaret C. Sullivan, Deborah Yaffe, and, of course, Elaine Bander, AGM Coordinator. (I hope I haven’t missed anyone – please let me know if I have.)

I’m delighted that I get to introduce Marcia McClintock Folsom’s talk on “Teaching Mansfield Park in the Twenty-First Century: New Contexts, Controversies, and Opportunities,” in which she’ll tell us about the brand new MLA volume Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Mansfield Park. (You can read about my contribution to the volume here.) And I’m delighted to be introducing the breakout session Natasha and her husband, Frederick Duquette, are doing on Saturday afternoon: “Fanny Price Amidst the Philosophers.” The details about the schedule are on the AGM website. It’s going to be a busy weekend, and I’ve mentioned only a few of the highlights here.

I’m delighted that I get to introduce Marcia McClintock Folsom’s talk on “Teaching Mansfield Park in the Twenty-First Century: New Contexts, Controversies, and Opportunities,” in which she’ll tell us about the brand new MLA volume Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Mansfield Park. (You can read about my contribution to the volume here.) And I’m delighted to be introducing the breakout session Natasha and her husband, Frederick Duquette, are doing on Saturday afternoon: “Fanny Price Amidst the Philosophers.” The details about the schedule are on the AGM website. It’s going to be a busy weekend, and I’ve mentioned only a few of the highlights here.

I want to tell you a little bit more about one of the exciting special events at the AGM. Diana Birchall and Syrie James, who are both contributors to “An Invitation to Mansfield Park,” have written a play called “A Dangerous Intimacy: Behind the Scenes at Mansfield Park,” which will be performed on Friday evening. Tickets are still available.

This is the second staged reading Diana and Syrie have collaborated on for a JASNA AGM – the first was the popular “Austen Assizes,” which was performed at the 2012 AGM in New York City. You can read more about the “Austen Assizes” and watch some of the highlights on Syrie’s website. Diana tells me the cast for “A Dangerous Intimacy” consists of “prominent Janeites with a turn for acting,” and Syrie promises the play will be very funny.

The cast of the “Austen Assizes” play. Thanks to Diana for the photo.

If you’ve been following “An Invitation to Mansfield Park” for a while, you’ll remember Diana’s guest post, the beginning of a short story called “The Scene-Painter,” and if you want to find out what happens next, you’ll want to read tomorrow’s blog post, which is Part Two of the story. Diana expands on the brief references Austen makes to the minor character who comes to Mansfield Park to paint scenes for the performance of Lovers’ Vows, and leaves having “spoilt only the floor of one room, ruined all the coachman’s sponges, and made five of the under-servants idle and dissatisfied” (Chapter 20). You can read (or reread) Part One here. Stay tuned for Part Two!

I know many of you who’ve been reading and commenting on these guest posts will be in Montreal for the AGM, too, and I’m looking forward to seeing you soon! Please come and talk to me at our breakout session or the authors’ signing event, or any time over the weekend. My secret plot to make the Mansfield Park celebrations extend well beyond the October long weekend is working, thanks to all of you, and I’m glad we get to continue the party even after the AGM ends on Sunday.

I’m also glad that the blog makes it possible for those of you who aren’t going to Montreal to participate in some of the celebrations of this amazing novel. Thank you for reading, for commenting, for sharing these posts with your friends, and for accepting the invitation to what is definitely the biggest – and longest-running – party I have ever hosted in my life.

October 3, 2014

How should we read the character of William Price?

Twenty-second in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Hugh Kindred is Emeritus Professor of Law at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, with special interests in international and maritime law. He has also conducted research on the naval career of Captain Charles Austen in Canada, Bermuda, and the United Kingdom. He’s a regular participant in JASNA Nova Scotia Regional meetings and he frequently attends the Jane Austen Society (UK) annual meetings at Chawton House and meetings of the JAS Kent Branch.

When our JASNA Nova Scotia group meets each December to celebrate Jane Austen’s birthday, it is Hugh who regularly proposes an eloquent birthday toast, which is always accompanied by a brief reading from Austen’s novels or letters. At the 2012 JASNA AGM in New York, Hugh and his wife Sheila Johnson Kindred presented a fascinating breakout session on “Naval Prize, Power, and Passion in Persuasion.” Today, it’s my pleasure to introduce his guest post on the character of William Price.

In this image from Master & Commander, you can clearly see the midshipmen’s uniforms.

William had obtained a ten days’ leave of absence to be given to Northamptonshire, and was coming, the happiest of lieutenants, because the latest made, to shew his happiness and describe his uniform.

He came; and he would have been delighted to shew his uniform there too, had not cruel custom prohibited its appearance except on duty. So the uniform remained at Portsmouth, and Edmund conjectured that before Fanny had any chance of seeing it, all its own freshness and all the freshness of its wearer’s feelings, must be worn away. It would be sunk into a badge of disgrace; for what can be more unbecoming, or more worthless, than the uniform of a lieutenant, who has been a lieutenant a year or two, and sees others made commanders before him? So reasoned Edmund, till his father made him the confidant of a scheme … .

This scheme was that [Fanny] should accompany her brother back to Portsmouth, and spend a little time with her own family. … Edmund considered it every way, and saw nothing but what was right … [and] good in itself … . This was enough to determine Sir Thomas; … [yet] his prime motive in sending her away, had very little to do with the propriety of her seeing her parents again, and nothing at all with any idea of making her happy. He certainly wished her to go willingly, but he as certainly wished her to be heartily sick of home before her visit ended; and that a little abstinence from the elegancies and luxuries of Mansfield Park would bring her mind into a sober state, and incline her to a juster estimate of the value of that home of greater permanence, and equal comfort, of which she had the offer.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 25 (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1988)

Joseph Morgan as William Price in the 2007 adaptation of Mansfield Park, directed by Iain B. MacDonald.

William Price is only a minor character in Mansfield Park, yet he is a significant one. Of the several places that he crops up in the novel, I have chosen this passage because it points to the most obvious of several ways to think about his role in Jane Austen’s creation. Why Austen formed him as she did is all speculation, of course, but Austen wrote with such care, finesse and deliberation that, even as I wonder at her prose, I constantly find myself wondering about the larger implications which lie beneath the surface of her stories.

So how should we read the character of William Price in Mansfield Park? First and foremost, he is a useful creation to advance the novel’s plot. Sir Thomas, in presenting his scheme in the passage above, rightly anticipates that Fanny will jump at the chance to travel with William to Portsmouth to see him dressed as a freshly minted lieutenant and to see him off to sea as an officer on HMS Thrush. Perhaps William’s part is not absolutely necessary, for Fanny might well have seized the opportunity to visit her family and her old home whether William was present or absent. But William’s presence makes Sir Thomas’ offer to Fanny that much more certain of acceptance as well as capable of execution. The latter consideration would have been important because Fanny could not have travelled to London and thence to Portsmouth except in the company of a suitable male, which William’s presence supplies.

Cartoon of midshipman supervising the daily slops.

It is made clear, of course, pace Edmund’s innocent approval, that Sir Thomas’ generosity is not altruistic. He wants Fanny to experience what he correctly supposes will be the relative misery of her family home in comparison with the civility and well-being of her adopted home at Mansfield Park and thus to appreciate fully the opportunity before her of attaining her own home of equal comfort by reversing her obstinate rejection of Henry Crawford’s offer of marriage. He wants her, in short, to make this visit in order to come to her senses, as he projects them. William is the very convenient yet unknowing agent of this scheme.

It is not clear whether Sir Thomas has anything to do with Henry Crawford’s subsequent arrival in Portsmouth to importune Fanny. His “dignified musings” are not said to have included any intention of reporting Fanny’s presence in Portsmouth to Crawford, who, in any case, could readily have been informed by others at Mansfield Park. Absent any evidence, Sir Thomas cannot be accused of the further infamy of deliberately putting Fanny in the way of Crawford in even more traumatic circumstances for her than at Mansfield Park. In this passage Sir Thomas appears controlling but well-meaning, by his lights, and not callous. And, though the scheme does not work out as Sir Thomas, at the time, desired, it serves Jane Austen very well to move her story forward.

A second way to consider how William Price appears in the novel involves the personal attributes that Austen ascribes to him. Compared to all the “gentlemen” at Mansfield Park, who are all tarnished products to varying degrees, though they are supposed by their breeding to know and do better, William Price is the only unblemished male. He is young and so has had less time than the others to learn or practise errant ways, but I also suggest that the personality and character given to him by Austen might be regarded as a standard of the ideal male in development, against which we readers may compare all the rest of them.

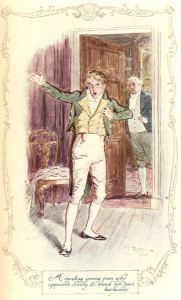

“William was often called on by his uncle to be the talker.” Illustration by C.E. Brock.

The novel’s narrator appears to imply approvingly that William Price is a young man who is going about life the right way to make something of himself, despite his lowly starting place, and doing it with a cheerful spirit and an open heart. Jane Austen seems to suggest there is virtue in hard work and endurance in the face of difficulties and hardship, for which there should be recognition and reward by society as readily as their attainment by idle inheritance. At the same time, she intimates that work and struggle are not by themselves sufficient without opportunity for education and refinement of mind and conduct, of the kind that Mansfield Park can offer.

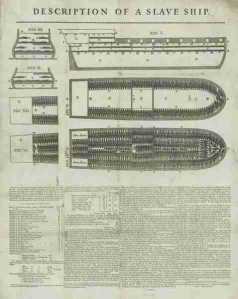

There is ambivalence in these sentiments. The real world when Jane Austen was writing Mansfield Park was changing very rapidly, as she knew. The slave trade had been outlawed in England and the returns from slave based sugar plantations in the Americas, which were sources of sustenance for estates like Mansfield Park, were beginning to decline. (See the seventeenth post in this series, by Deborah Barnum – “Jane Austen’s ‘dead silence,’ or, How Guilty is Sir Thomas Bertram?” – and the ensuing online discussion.) The Napoleonic wars by sea and by land threatened the whole population and imposed an enormous economic and social burden on the country. A new cash-based economy centred on the cities and towns was challenging the ancient rural values of landed estates and family settlements. In this larger context, William Price may, perhaps, be viewed as the hopeful new man for the new conditions, even as Jane Austen approves the civility of the passing era of Mansfield Park.

“Complete in his lieutenant’s uniform.” Illustration by H.M. Brock

But will William Price succeed, as he deserves to? Here is a possible third consideration in thinking about Austen’s construction of this character. Being an efficient and effective midshipman or an outstanding leader as a lieutenant, and thus deserving to be “made up” to higher rank and income, may not have been enough for advancement. Promotion depended partly and inevitably on the varying national need for warships and officers, which was diminished after Nelson won the battle of Trafalgar in 1805 and British ascendancy over the seas was assured. It was also significantly influenced by a system of patronage, which was jealously controlled and applied by the upper classes. Jane Austen knew all about this system too, as she lets her characters tell us most directly.

First, Midshipman Price himself speaks despondently of ever becoming a Lieutenant: “I begin to think I shall never be a lieutenant, Fanny. Everybody gets made but me” (Chapter 25). William does become a lieutenant, to his great satisfaction and the delight and pride of Fanny, but only through the intervention of Henry Crawford. Hoping to advance himself in Fanny’s affections, Crawford applies to his uncle, who happens to be an Admiral, and persuades him to exercise his influence within the Admiralty. William benefits from this act of patronage by being appointed second lieutenant on HMS Thrush.

“Looked at him for a moment in speechless admiration.” Fanny sees William dressed as a Lieutenant just before he leaves the Price home to board his ship. Illustration by C.E. Brock.

Will Lieutenant Price rise further? Certainly not at the bidding of Crawford: his intervention was a once-only act of patronage out of his own selfish objectives, not a deed of generosity for the advancement of a young man of whom he cared or approved. Edmund shows that he understands the situation when he makes the second despondent comment about William’s future. In the second paragraph quoted at the head of this post, Edmund foretells that William’s prized new uniform as a lieutenant will, in a year or two, become a “badge of disgrace” as he sees others promoted to commanders before him.

Jane Austen clearly understood the chequered chances for advancement of a naval career by an aspiring and estimable candidate who was but a poor cousin of the upper class. But is she accepting of the part played by patronage or is she espousing the claims of merit in the way she presents the character of William Price in Mansfield Park? It is intriguing to think about William Price as the new man of the age who should rise more by ability than entitlement. We will never know whether Jane Austen had any such views in mind, and we are at liberty to read the character of William Price as we wish. But Jane Austen does give a possible hint of her opinions on the last page of the novel in making note, in passing, of “William’s continued good conduct, and rising fame” (Chapter 48).

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Natasha Duquette, Margaret Horwitz, Sarah Woodberry, and Joyce Tarpley.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

September 26, 2014

Discerning a Vocation in Mansfield Park – But Whose?

Twenty-first in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

The Rev. Dr. Maggie Arnold is currently serving as Assistant Rector at Grace Episcopal Church in Medford, Massachusetts. Many years ago, she and I read Pride and Prejudice together in a high school English class in our hometown, Halifax, Nova Scotia, and I’m very pleased to introduce her post on the important topic of “ordination” in Mansfield Park. I’m also grateful to her for the lovely illustration of a country house she contributed to “An Invitation to Mansfield Park.”

Maggie holds degrees in Fine Arts from NSCAD University in Halifax and The University of the Arts in Philadelphia, a Master of Divinity from Boston University’s School of Theology, and a PhD in Religious and Theological Studies from Boston University. Her dissertation, “Mary Magdalene in the Era of Reformation,” compares Protestant and Catholic interpretations of the Magdalene in the Early Modern Period, especially as they related to the question of women’s public ministry.

“We shall be the losers,” continued Sir Thomas. “His going, though only eight miles, will be an unwelcome contraction of our family circle; but I should have been deeply mortified if any son of mine could reconcile himself to doing less. It is perfectly natural that you should not have thought much on the subject, Mr. Crawford. But a parish has wants and claims which can be known only by a clergyman constantly resident, and which no proxy can be capable of satisfying to the same extent. Edmund might, in the common phrase, do the duty of Thornton, that is, he might read prayers and preach, without giving up Mansfield Park; he might ride over every Sunday, to a house nominally inhabited, and go through divine service; he might be the clergyman of Thornton Lacey every seventh day, for three or four hours, if that would content him. But it will not. He knows that human nature needs more lessons than a weekly sermon can convey; and that if he does not live among his parishioners, and prove himself, by constant attention, their well-wisher and friend, he does very little either for their good or his own.”

“We shall be the losers,” continued Sir Thomas. “His going, though only eight miles, will be an unwelcome contraction of our family circle; but I should have been deeply mortified if any son of mine could reconcile himself to doing less. It is perfectly natural that you should not have thought much on the subject, Mr. Crawford. But a parish has wants and claims which can be known only by a clergyman constantly resident, and which no proxy can be capable of satisfying to the same extent. Edmund might, in the common phrase, do the duty of Thornton, that is, he might read prayers and preach, without giving up Mansfield Park; he might ride over every Sunday, to a house nominally inhabited, and go through divine service; he might be the clergyman of Thornton Lacey every seventh day, for three or four hours, if that would content him. But it will not. He knows that human nature needs more lessons than a weekly sermon can convey; and that if he does not live among his parishioners, and prove himself, by constant attention, their well-wisher and friend, he does very little either for their good or his own.”

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 25 (New York: Modern Library, 1933)

In re-reading Mansfield Park at a distance of some twenty years from my first acquaintance with the novel, I am now struck, as I was not then, by the repeated discussions of the role and nature of religion and the clergy. Edmund Bertram is to be ordained, and one strand of the story’s plot involves his working out of just what claims that profession will make upon him and how he will live up to them.

“Interior of a Church” (1819), by J.M.W. Turner

Early in the story, when the party from Mansfield Park visits Sotherton and sees the chapel, Fanny describes her image of a space for domestic piety: “melancholy” and “grand.” The topic of faith leads to Mary Crawford’s discovery that Edmund is himself to take orders, and to his defense of that vocation. In a later conversation with Mary Crawford, Dr. Grant, the holder of the Mansfield living, is revealed to be a bad clergyman because of his gluttony and selfish temperament.

Other posts in this series have explored some of these passages and what they may demonstrate about the values and virtues advanced by Austen. (See “Why Tom Bertram is right that Dr. Grant will ‘soon pop off,’” by Cheryl Kinney, “Something from Nothing,” by Mary Lu Roffey Redden, and “Dr. Grant’s Green Goose,” by Julie Strong.)

In my text, an exchange between Sir Thomas Bertram and Henry Crawford, Sir Thomas lays out his reasons for believing that a pastor ought to live within his parish. A good pastor must know the affairs of the community intimately, caring about them as his own, and he must provide a present example of Christian discipleship to his congregation.

Taken together, these discussions serve to show a sympathy of mind and spiritual commitment that unites Fanny and Edmund. This agreement makes their ultimate marriage the right one, after the mistaken attachment Edmund forms for the frivolous Mary Crawford, and the danger of Henry Crawford’s proposal to Fanny. Fanny and Edmund share a high ideal of the church’s place in society and of ordained vocations as a call to servant ministry. Many of the concerns the author gives to Edmund and Fanny would be animating principles of the Oxford Movement, which began less than twenty years after Mansfield Park’s publication. The Tractarians were likewise preoccupied with a reform and renewal of local parish life and with the spiritual formation of the clergy.

Of the young couple, however, it is Fanny more than Edmund who possesses the character of a Christ-like servant. She displays this character in her relations with family and friends, ministering patiently and with quiet humility in the household. Her nature does not permit her to forget even the needs of the officious and ungrateful Mrs. Norris, or the indolent and narcissistic Lady Bertram.

But beyond being an angel in the house, Fanny is also a more public apologist for Christianity. She is passionate and articulate in advocating a righteous church, joining heartily in theological discussions with Edmund and even initiating them, as in the conversation in the Sotherton chapel. Indeed, her description of the chapel she would rather have found there resembles an Oxford Movement church, with moody, neo-Gothic decorations and literary references. It is surely not insignificant that in her most visible moment before Mansfield society, at her coming-out ball, her only desired ornament is a cross.

But beyond being an angel in the house, Fanny is also a more public apologist for Christianity. She is passionate and articulate in advocating a righteous church, joining heartily in theological discussions with Edmund and even initiating them, as in the conversation in the Sotherton chapel. Indeed, her description of the chapel she would rather have found there resembles an Oxford Movement church, with moody, neo-Gothic decorations and literary references. It is surely not insignificant that in her most visible moment before Mansfield society, at her coming-out ball, her only desired ornament is a cross.

Fanny is finally able to fulfill her own religious vocation as the wife of a clergyman, a prominent role that had evolved in Protestant culture since the innovation of a married clergy in the Reformation. Pastors’ wives were models of faith as well as of its application in marriage, the raising of children, the running of the household, and charitable work in the parish. Though this was the happy ending of Mansfield Park’s early nineteenth-century context, among the tragic elements of the novel for twenty-first century readers must be the limitation placed on the career of a woman so faithful in her ministry to her neighbours and so eloquent in her vision of what the church could be.

Born two hundred years later, would Fanny have succeeded naturally to the living at Mansfield Park and overcome her shyness to preach redemption for latter-day Bertrams and Crawfords?

Katharine Jefferts Schori, Presiding Bishop of the E.C.U.S.A. (from The Grand Island Independent)

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Hugh Kindred, Natasha Duquette, Margaret Horwitz, and Syrie James.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

September 23, 2014

An Evening with Patrick Stokes in Halifax

Patrick Stokes, former Chairman of the Jane Austen Society (UK), will be visiting Halifax in the week before the JASNA AGM in Montreal. At the AGM, he’ll give a plenary lecture on October 12th on “‘Rears and Vices’: The Georgian Royal Navy.”

You’re invited to our next JASNA Nova Scotia meeting, in Halifax, on Tuesday, October 7th at 7:30 p.m. for an informal conversation with Patrick about the Royal Navy. Let me know if you’re interested, either by email (semsley at gmail dot com) or by leaving a comment here, and I’ll pass on details about the location.

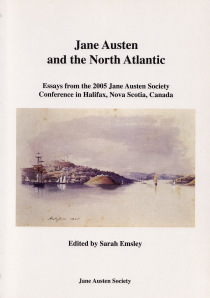

What a wonderful time we had here in Halifax in September of 2005, when Patrick organized the JAS conference “Jane Austen and the North Atlantic.” Sheila Johnson Kindred gave a talk on “Charles and Francis Austen in Halifax, Canada,” Brian Southam spoke about fact and fiction in a lecture on “Jane Austen and North America,” Peter W. Graham analyzed “Insular Austen, Oceanic Austen: ‘Bits of Ivory’ and Beyond,” Brian Cuthbertson gave an overview of Halifax history, and I talked about Canadian and American readers of Austen’s happy endings.

What a wonderful time we had here in Halifax in September of 2005, when Patrick organized the JAS conference “Jane Austen and the North Atlantic.” Sheila Johnson Kindred gave a talk on “Charles and Francis Austen in Halifax, Canada,” Brian Southam spoke about fact and fiction in a lecture on “Jane Austen and North America,” Peter W. Graham analyzed “Insular Austen, Oceanic Austen: ‘Bits of Ivory’ and Beyond,” Brian Cuthbertson gave an overview of Halifax history, and I talked about Canadian and American readers of Austen’s happy endings.

We all enjoyed touring Uniacke House, the Maritime Command Museum, Government House, and other local highlights. At the time I was still teaching in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and it was a real pleasure to come home to Halifax to participate in such an inspiring conference.

You can read more about the conference in Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, the volume of essays I edited for the Jane Austen Society.

JASNA Nova Scotia members are very much looking forward to welcoming Patrick Stokes back to Halifax. Please join us on October 7th!

Uniacke House, Mount Uniacke, Nova Scotia

September 19, 2014

Mary Crawford: The Black Cloud of Mansfield Park

Twentieth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

One of the things I like best about hosting this party for Mansfield Park is that I can bring together so many of Jane Austen’s readers. Among the contributors to the series are writers of Austen-inspired fiction, bloggers, booksellers, journalists, librarians, and academics. There’s even one priest, one doctor, and one lawyer – let’s see what happens if the three of them walk into a bar at the JASNA AGM in Montreal next month. I like that there’s diversity even among those of us trained as academics – several study Austen and her contemporaries, of course, but there are also scholars of Early Modern literature and of Modernist literature. All of us share an interest in this complex and endlessly fascinating novel, and all of us are grateful to you for reading and participating in the conversations. It wouldn’t be much of a party without you!

It’s a pleasure today to introduce a guest post on Mary Crawford by Laurel Ann Nattress, who hosts the well-known blog Austenprose.com. I’ve followed Laurel Ann’s blog for a long time, and have also enjoyed writing reviews for Austenprose. Laurel Ann calls herself “a life-long acolyte of Jane Austen,” and says her blog is “devoted to the oeuvre of my favorite author and the many books and movies that she has inspired.” A Life Member of the Jane Austen Society of North America and a regular contributor to the Jane Austen Centre Online Magazine, Laurel Ann is also the editor of the very entertaining short story collection Jane Austen Made Me Do It (2011), which includes stories by Stephanie Barron, Carrie Bebris, Laurie Viera Rigler, and many others, including three writers who are also contributors to “An Invitation to Mansfield Park” – Diana Birchall, Syrie James, and Margaret C. Sullivan.

It’s a pleasure today to introduce a guest post on Mary Crawford by Laurel Ann Nattress, who hosts the well-known blog Austenprose.com. I’ve followed Laurel Ann’s blog for a long time, and have also enjoyed writing reviews for Austenprose. Laurel Ann calls herself “a life-long acolyte of Jane Austen,” and says her blog is “devoted to the oeuvre of my favorite author and the many books and movies that she has inspired.” A Life Member of the Jane Austen Society of North America and a regular contributor to the Jane Austen Centre Online Magazine, Laurel Ann is also the editor of the very entertaining short story collection Jane Austen Made Me Do It (2011), which includes stories by Stephanie Barron, Carrie Bebris, Laurie Viera Rigler, and many others, including three writers who are also contributors to “An Invitation to Mansfield Park” – Diana Birchall, Syrie James, and Margaret C. Sullivan.

Classically trained as a landscape designer at California Polytechnic State University at San Luis Obispo, Laurel Ann has also worked in marketing for a Grand Opera company, and at present, she says, she “delights in introducing neophytes to the charms of Miss Austen’s prose as a bookseller at Barnes & Noble.” An expatriate of southern California, Laurel Ann lives in a country cottage near Snohomish, Washington where, she tells me, “it rains a lot.” (Sounds like Nova Scotia to me.) Visit Laurel Ann at her blog Austenprose – A Jane Austen Blog, on Twitter as @Austenprose, and on Facebook as Laurel Ann Nattress.

I was amazed and humbled when Sarah Emsley asked me to contribute a blog post for “An Invitation to Mansfield Park.” Not being a scholar of her caliber, or her readers, what could I possibly offer to this collection of essays? So, I take up this assignment, hat in hand, from the perspective of a Janeite, offering a reader’s opinion on my favorite line and chapter from Jane Austen’s most complex and thought-provoking novel.

I remember my first encounter with Mansfield Park. It was the third Austen novel I read after Pride and Prejudice and Emma. I had no idea what to expect, since this was 1986, long before I even knew there was a Jane Austen Society of North America and ten years before the creation of the Internet website The Republic of Pemberley to enlighten me on what was ahead. Looking back now, those were indeed the wilderness years when Jane Austen enthusiasts read and worshiped in silence.

My first impression of Mansfield Park was not what I expected. It was dark and brooding. The characters seemed to be at continual odds with each other. It was unsettling. Contemplative. Puzzling. It was not anything like the sparkling, witty and romantic Pride and Prejudice that she was so famous for. I was miserable, and totally engrossed at the same time — a Jane Austen bus accident that defied explanation. With no one to talk it over with, I read it again. Still puzzled, I put it aside. Ten years later, and then twenty, I read it again. It became my holy grail of literature. After years of Austen study, and with the benefit of discussing characters and plot points with other Janeites I had met on the Internet, Mansfield Park had evolved, for me, into the hardest-won literary battle of my life — the struggle had made the victory all the sweeter.

My first impression of Mansfield Park was not what I expected. It was dark and brooding. The characters seemed to be at continual odds with each other. It was unsettling. Contemplative. Puzzling. It was not anything like the sparkling, witty and romantic Pride and Prejudice that she was so famous for. I was miserable, and totally engrossed at the same time — a Jane Austen bus accident that defied explanation. With no one to talk it over with, I read it again. Still puzzled, I put it aside. Ten years later, and then twenty, I read it again. It became my holy grail of literature. After years of Austen study, and with the benefit of discussing characters and plot points with other Janeites I had met on the Internet, Mansfield Park had evolved, for me, into the hardest-won literary battle of my life — the struggle had made the victory all the sweeter.

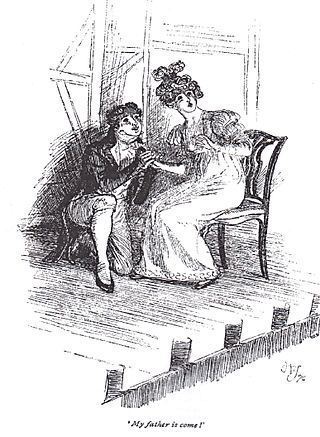

During this thirty-year sojourn with Austen’s dark horse I connected with a particular chapter that was my ah-ha moment — that epiphany of illumination when I finally got it — or at least I thought so. Chapter 22 was my magic key. It revealed so much and answered many of my questions. Our heroine Fanny Price has been sent on an errand to the village by Mrs. Norris and been caught in a downpour without an umbrella. Huddled under a sparse oak tree outside of Mansfield parsonage, one of its residents Mary Crawford spies her shivering in the rain and sees an opportunity for her own entertainment, sending Dr. Grant out with an umbrella to fetch her inside. At this point, the sophisticated Miss Crawford is bored without the female companionship of the Bertram sisters and has cast her net for Fanny as her new friend. Mary and Mrs. Grant mollify Fanny’s objections to staying with dry clothes and attention. Mary plays the harp, entreating Fanny to stay longer than she wants:

“Another quarter of an hour,” said Miss Crawford, “and we shall see how [the weather] will be. Do not run away the first moment of its holding up. Those clouds look alarming.”

“But they are passed over,” said Fanny. — “I have been watching them. — This weather is all from the south.”

“South or north, I know a black cloud when I see it; and you must not set forward while it is so threatening. And besides, I want to play something more to you — a very pretty piece — and your cousin Edmund’s prime favourite. You must stay and hear your cousin’s favourite.”

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 22 (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1988)

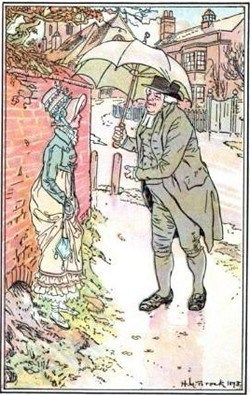

“Dr Grant himself went out with an umbrella.” Illustration by H.M. Brock.

This short passage is so telling for me. Mary Crawford is bending Fanny’s will, as she does to so many in the novel. She speaks authoratively, decisively and officiously to Fanny, dismissing her observation of the rain having let up.

“South or north, I know a black cloud when I see it; and you must not set forward while it is so threatening.”

Like a spider to the fly, Mary has drawn poor Fanny into her web and made her stay longer than she wants to. When Fanny, the keen observer of nature, and the moral compass of the novel, expresses her opinion of the weather clearing as an exit cue to her hostess, she is dismissed by Miss Crawford, a character who reveals her controlling, selfish, and arrogant nature by stating that she knows a black cloud when she sees one, yet has not looked out the window. Screeching halt! Giant red flag! Austen has cleverly revealed that manipulative Mary and gentle Fanny are as opposite as black and white in their view of the world. Mary knows a black cloud when she sees one, because she is one. Her presence and opposing opinions will continue to dampen her encounters throughout the novel, and Fanny, who sees only the truth before her, will remain true to her own principles and our hearts.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Maggie Arnold, Hugh Kindred, Natasha Duquette, and Margaret Horwitz.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

September 12, 2014

Henry Crawford and Moral Taste

Nineteenth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Elaine Bander was the first person I asked to contribute a guest post to this series celebrating Mansfield Park. Last fall, when JASNA Nova Scotia was fortunate to have Elaine visit us to give a talk on “Jane Austen’s Fanny Price and Lord Nelson: Rethinking the National Hero(ine),” I mentioned that I had been thinking about putting something together on my blog to honour Mansfield Park. At the time, I imagined inviting a few people to write guest posts, but the party kept getting bigger and I am so pleased to be celebrating with all of you. Thank you, Elaine, for being the first to sign on!

Elaine says she’s been pondering Mansfield Park since she began writing her dissertation on Austen nearly forty years ago. Now retired from teaching at Dawson College in Montreal, she is Coordinator of JASNA’s 2014 AGM: “Mansfield Park in Montréal: Contexts, Conventions & Controversies” (October 10-12, 2014) and serves on the editorial board of JASNA’s journal, Persuasions.

I interviewed her last fall about her experience in JASNA’s International Visitor Program, her longstanding connections with The Burney Society, and her experience of discovering Jane Austen’s novels. You can read the interview here, and you can read about Elaine’s visit to Halifax and her talk on Fanny Price’s courage here. I know the AGM is going to be wonderful and I can’t wait to spend the weekend talking about Mansfield Park in person with so many of you!

It was a picture which Henry Crawford had moral taste enough to value. Fanny’s attractions increased – increased two-fold – for the sensibility which beautified her complexion and illuminated her countenance, was an attraction in itself. He was no longer in doubt of the capabilities of her heart. She had feeling, genuine feeling. It would be something to be loved by such a girl, to excite the first ardours of her young, unsophisticated mind! She interested him more than he had foreseen. A fortnight was not enough. His stay became indefinite.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 24 (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2006)

Henry Crawford, a disengaged, charming, compulsive flirt, begins to fall in love with Fanny Price when he perceives the warmth and depth of her feeling for her brother William. It helps that he’s bored, that Maria and Julia are gone, and that restless, gifted, undisciplined Henry, coming to the end of his duty visit to his sisters, is looking for a new project or challenge. His original “wicked project” (Mary’s words) was to make a small hole in Fanny’s heart, to woo her lightly for the sport of the hunt. Her obvious “sensibility,” however, intrigues and attracts him.

Taught by his uncle to despise marriage and to think all women venial, Henry imagines exciting “the first ardours of her young, unsophisticated mind!” He already perceives that Fanny is not like her cousins, and he will soon tell her that she has something of the angel about her. So Henry postpones his departure.

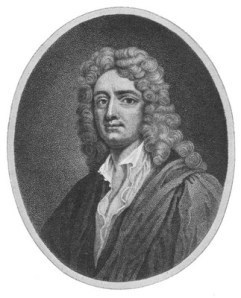

Neither a stock despoiler of virgins nor a Lovelace-like rake, Henry has “moral taste.” This expression has a history going back to the philosophical writings of Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury (1671-1713) and was current in the general popular culture of Austen’s time, underpinning much of the literature of sensibility and posing a philosophical opposition to more traditional morality (like Fanny’s) founded upon firm moral principles and the duty of reflection.

Anthony Ashley Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury

Meanwhile Fanny’s own aesthetic taste is powerfully attracted to Henry’s considerable acting talent, albeit without seriously affecting her moral judgment of him. During the rehearsals, she “believed herself to derive as much innocent enjoyment from the play as any of them; – Henry Crawford acted well, and it was a pleasure to her to creep into the theatre, and attend the rehearsal of the first act” of Lovers’ Vows.

When later Henry reads from King Henry VIII, Fanny responds involuntarily, against her conscious, rational judgment and will, against her very “principles,” to his acting skill: her needle falls from her hand, and “the eyes which had appeared so studiously to avoid him throughout the day, were turned and fixed on Crawford, fixed on him for minutes . . . until the book was closed, and the charm was broken.” With Henry’s charm broken, Fanny’s rational judgment reasserts itself. She resists equating aesthetic good with moral good.

Lovers’ Vows

Shaftesbury had claimed that just as we are naturally attracted to the beautiful, so too we have an innate sense or attraction to the good. Marianne Dashwood references a form of this belief when she defends her transgressive visit to Allenham with Willoughby: “for if there had been any real impropriety in what I did, I should have been sensible of it at the time, for we always know when we are acting wrong, and with such a conviction I could have had no pleasure.” After some reflection, Marianne admits, “Perhaps, Elinor, it was rather ill-judged in me to go to Allenham.”

Henry, however, like the rest of the characters in Mansfield Park with the exception of Fanny, does not reflect. He feels and desires. When he rhapsodizes about Fanny’s beauty, grace and gentleness of temper to Mary, the narrator tells us:

Henry Crawford had too much sense not to feel the worth of good principles in a wife, though he was too little accustomed to serious reflection to know them by their proper name; but when he talked of her having such a steadiness and regularity of conduct, such a high notion of honour, and such an observance of decorum as might warrant any man in the fullest dependence on her faith and integrity, he expressed what was inspired by the knowledge of her being well principled and religious. (Chapter 30)

Henry Crawford had too much sense not to feel the worth of good principles in a wife, though he was too little accustomed to serious reflection to know them by their proper name; but when he talked of her having such a steadiness and regularity of conduct, such a high notion of honour, and such an observance of decorum as might warrant any man in the fullest dependence on her faith and integrity, he expressed what was inspired by the knowledge of her being well principled and religious. (Chapter 30)

Henry cannot even name the qualities he admires in Fanny. As a sensible man and a gifted actor who envies Edmund and William their professional commitments, he values Fanny aesthetically and morally, but without serious reflection. Characteristically, he rejoices in the role of chivalrous lover and protector of friendless Fanny.

Then why does he elope with Maria Rushworth? I don’t think he has fallen out of love with Fanny, or into love with Maria, whom he rather despises. Nor do I think he is simply a compulsive seducer of women. I have always imagined that his conceit-driven, casual flirtation with Maria leads to some exciting, secret, physical fondling, which prompts desperate Maria to show up on Henry’s doorstep one evening declaring that she has left Mr. Rushworth and has put herself under Henry’s protection. Henry, too much of a gentleman to turn her away, must then accept the consequences of his own unreflective behaviour: the loss of Fanny, whom he had had the moral taste to appreciate.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Laurel Ann Nattress, Maggie Arnold, Hugh Kindred, and Natasha Duquette.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

September 9, 2014

Halifax, Nova Scotia in L.M. Montgomery’s Island Scrapbooks

L.M. Montgomery included many references to her time in Halifax, Nova Scotia in the “Island Scrapbooks” she created. I read Elizabeth Rollins Epperly’s book Imagining Anne: The Island Scrapbooks of L.M. Montgomery not long after it was published in 2008, but when I bought my own copy on a recent trip to Prince Edward Island, I decided to reread it in light of my new interest in the Nova Scotia connections in Montgomery’s life and work.

Lilacs at Village Pottery, New London, PEI, June 2014

Montgomery spent a year studying English at Dalhousie University, from 1895 to 1896, and she included an image of the main building with the caption “Dalhousie College, Halifax, the doors of which are wide open to women.” She received little encouragement from her family and friends when she chose to study at Dalhousie, and she must have been pleased to know that from the time it was founded in 1818, the university had never excluded women.

There are pieces of Dalhousie’s black and gold striped ribbon in two places in the Blue Scrapbook, on page 20 and tucked between pages 70 and 71, as well as a bit of ribbon on page 51 with the purple and gold colours of the Halifax Ladies’ College (and its successor, Armbrae Academy), where Montgomery boarded. The Red Scrapbook includes images of the interior and exterior of the Ladies’ College.

The Blue Scrapbook includes a card commemorating a New Year’s party held on Brunswick Street and a poem by Dalhousie English professor Archibald MacMechan entitled “My Lady of Dreams,” with this intriguing scrap of paper pasted beneath it: “What was the matter with the P.E.I. girl when she chased her room-mate through the window?” The juxtaposition between the poem and the question is intriguing. The poem is a meditation on lost love, dated “Saint’s Day, ’95,” written in a mood very different from the unanswered question, and the contrast is somewhat jarring. But that’s exactly the sort of effect Montgomery achieves in other places in the scrapbooks as she mixes “bright fragments” to “suggest metaphors and layers of story and feeling,” as Epperly says in her prefatory essay on “The Island Scrapbooks.”

The Blue Scrapbook includes a card commemorating a New Year’s party held on Brunswick Street and a poem by Dalhousie English professor Archibald MacMechan entitled “My Lady of Dreams,” with this intriguing scrap of paper pasted beneath it: “What was the matter with the P.E.I. girl when she chased her room-mate through the window?” The juxtaposition between the poem and the question is intriguing. The poem is a meditation on lost love, dated “Saint’s Day, ’95,” written in a mood very different from the unanswered question, and the contrast is somewhat jarring. But that’s exactly the sort of effect Montgomery achieves in other places in the scrapbooks as she mixes “bright fragments” to “suggest metaphors and layers of story and feeling,” as Epperly says in her prefatory essay on “The Island Scrapbooks.”

Montgomery’s “last examination,” written on April 17, 1896, is represented in the Blue Scrapbook – among the requirements were instructions to “Write a note on the use of the chorus in Henry IV,” “Justify the introduction of the comic characters in Henry IV Pts I & II,” and “Contrast the ‘rake’s progress’ of Falstaff and Prince Hal.” Dalhousie’s Convocation was held privately that year, Epperly says, “out of respect for the death of George Munro, a chief Dalhousie donor” (whose legacy is still commemorated each year in February when the University observes the Munro Day holiday).

Epperly remarks on the significance for Montgomery of the phrase “The Bend of the Road” (from the poem by Grace Denio Lichfield, reproduced in the Red Scrapbook), which she used as the title of the last chapter of Anne of Green Gables. She apparently shared Anne’s optimism about the future and what lies beyond that mysterious bend. Epperly says “many of Montgomery’s photographs were organized around a similar bend or curve: Montgomery’s and Anne’s beloved Lover’s Lane is frequently photographed and described with that provocative bend.”

Given my own interest in Montgomery and Point Pleasant Park, I was interested to find that the Notman Studio image of “A pretty bit of scenery in Point Pleasant Park, Halifax” in the Red Scrapbook also highlights a bend in the road along the shore.

A bend in the road at Point Pleasant Park, July 2014

You can read more about the images and poetry in the Island scrapbooks – and you can see a colour postcard of the bend in the road at Point Pleasant Park – in Christy Woster’s article in The Shining Scroll, “Clippings and Cuttings: Sources of Some of the Images and Poetry in L.M. Montgomery’s Island Scrapbooks.”

Melanie J. Fishbane is writing a YA novel based on the life of L.M. Montgomery, and she recently wrote a blog post about how she created a journal inspired by Montgomery’s scrapbooks.

I’ve finally put together a brand new page here on “L.M. Montgomery in Nova Scotia,” which lists all my blog posts on Montgomery, along with the books and essays I’ve been reading as I explore the connections between LMM and NS.

September 5, 2014

Forming Minds: Mind and Memory in Mansfield Park

Eighteenth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Lorrie Clark is an Associate Professor of English at Trent University in Peterborough, Ontario, where she teaches courses on Milton, eighteenth-century literature, Romanticism, history of the novel, tragedy, Jane Austen, and Joseph Conrad. She has published a book on William Blake, and she says initially she was especially interested in Jane Austen’s relation to Romanticism in Persuasion. I’m very happy to introduce her guest post on the “garden-gazing” scene in Mansfield Park.

“Mansfield Park has made me realize,” Lorrie says, “the extent to which Austen vigorously, consciously engaged in the eighteenth-century ‘Quarrel Between the Ancients and the Moderns’ about Aristotelian vs. modern scientific ideas of ‘nature,’ a quarrel with profound implications for understanding the foundation of morals in her novels. My blog post here attempts a small part of a much fuller argument on that subject published recently in Eighteenth-Century Fiction titled ‘Remembering Nature . . . in Mansfield Park’ (ECF 24:2, 2012).”

“Mansfield Park has made me realize,” Lorrie says, “the extent to which Austen vigorously, consciously engaged in the eighteenth-century ‘Quarrel Between the Ancients and the Moderns’ about Aristotelian vs. modern scientific ideas of ‘nature,’ a quarrel with profound implications for understanding the foundation of morals in her novels. My blog post here attempts a small part of a much fuller argument on that subject published recently in Eighteenth-Century Fiction titled ‘Remembering Nature . . . in Mansfield Park’ (ECF 24:2, 2012).”

Lorrie has reviewed numerous books on Austen (including my own Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues, in The Dalhousie Review), and she has given talks at several JASNA AGMs and Toronto JASNA chapter meetings. She says she’s really looking forward to the upcoming AGM in Montreal, “on what is certainly, because of its extraordinary depths, my favourite Austen novel.”

“This is pretty – very pretty,” said Fanny, looking around her as they were thus sitting together one day: “Every time I come into this shrubbery I am more struck with its growth and beauty. Three years ago, this was nothing but a rough hedgerow along the upper side of the field, never thought of as any thing, or capable of becoming any thing; and now it is converted into a walk, and it would be difficult to say whether most valuable as a convenience or as an ornament; and perhaps in another three years we may be forgetting – almost forgetting what it was before. How wonderful, how very wonderful the operations of time, and the changes of the human mind!” And following the latter train of thought, she soon afterwards added: “If any one faculty of our nature may be called more wonderful than the rest, I do think it is memory. There seems something more speakingly incomprehensible in the powers, the failures, the inequalities of memory, than in any other of our intelligences. The memory is sometimes so retentive, so serviceable, so obedient – at others, so bewildered and so weak – and at others again, so tyrannic, so beyond control! – We are to be sure a miracle every way – but our powers of recollecting and of forgetting, do seem peculiarly past finding out.”

Miss Crawford, untouched and inattentive, had nothing to say; and Fanny, perceiving it, brought back her own mind to what she thought must interest.

“It may seem impertinent in me to praise, but I must admire the taste Mrs. Grant has shown in all this. There is such a quiet simplicity in the plan of the walk! – not too much attempted!”

“Yes,” replied Miss Crawford carelessly, “it does very well for a place of this sort. One does not think of extent here – and between ourselves, until I came to Mansfield, I had not imagined a country parson ever aspired to a shrubbery or any thing of the kind.”

“I am so glad to see the evergreens thrive!” said Fanny in reply. “My uncle’s gardener always says the soil here is better than his own, and so it appears from the growth of the laurels and evergreens in general. – The evergreen! – How beautiful, how welcome, how wonderful the evergreen! – When one thinks of it, how astonishing the variety of nature! – In some countries we know the tree that sheds its leaf is the variety, but that does not make it the less amazing that the same soil and the same sun should nurture plants differing in the first rule and law of their existence. You will think me rhapsodizing, but when I am out of doors, especially when I am sitting out of doors, I am very apt to get into this sort of wondering strain. One cannot fix one’s eyes on the commonest natural production without finding food for a rambling fancy.”

“I am so glad to see the evergreens thrive!” said Fanny in reply. “My uncle’s gardener always says the soil here is better than his own, and so it appears from the growth of the laurels and evergreens in general. – The evergreen! – How beautiful, how welcome, how wonderful the evergreen! – When one thinks of it, how astonishing the variety of nature! – In some countries we know the tree that sheds its leaf is the variety, but that does not make it the less amazing that the same soil and the same sun should nurture plants differing in the first rule and law of their existence. You will think me rhapsodizing, but when I am out of doors, especially when I am sitting out of doors, I am very apt to get into this sort of wondering strain. One cannot fix one’s eyes on the commonest natural production without finding food for a rambling fancy.”

“To say the truth,” replied Miss Crawford, “I am something like the famous Doge at the court of Lewis XIV; and may declare that I see no wonder in this shrubbery equal to seeing myself in it.…”

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 22 (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1990)

Jane Austen’s novels are so exquisitely designed that we can see the whole novel in any given part. This makes it an almost overwhelming task to discuss this passage in a short blog post, but I’ll do my best!

This is one of only two “metaphysical” passages in all of Austen’s fiction. Both are in Mansfield Park: the celebrated “star-gazing” scene in which Fanny and Edmund reflect upon the beauty, order, and harmony of the night sky (Chapter 11); and this “garden-gazing” scene where Fanny reflects upon nature, including human nature, specifically, the human mind. I call these scenes “metaphysical” because through Fanny’s meditations Austen rises quite uncharacteristically to express her understanding of the universe and our place within it in ways that remain implicit in her other novels. This makes Mansfield Park the most explicit expression of Austen’s credo as an Aristotelian Christian, marking her “coming out” as an author as much as it marks Fanny’s coming out in society and Edmund’s ordination as a clergyman.

Fanny engages here in her most characteristic activity: reflecting aloud on nature and human nature. And while she often does this in solitude – alone on a garden bench at Sotherton (Chapters 9 and 10), or in her East room – she “converses” also with others, especially Edmund, and here, Mary Crawford. This scene in which, sitting with Mary, she gazes at Mrs. Grant’s garden and attempts to engage Mary in her “rhapsodizing” and “wondering” reflections on the beauties and mysteries of nature and human nature, contrasts greatly with the earlier star-gazing scene with Edmund. There, we experience with Fanny and Edmund a sense of profound harmony, tranquillity, and beauty, elevated to a shared sense of transcendence by “the sublimities of nature” understood as an ordered cosmic whole, one “Mind.”

Fanny engages here in her most characteristic activity: reflecting aloud on nature and human nature. And while she often does this in solitude – alone on a garden bench at Sotherton (Chapters 9 and 10), or in her East room – she “converses” also with others, especially Edmund, and here, Mary Crawford. This scene in which, sitting with Mary, she gazes at Mrs. Grant’s garden and attempts to engage Mary in her “rhapsodizing” and “wondering” reflections on the beauties and mysteries of nature and human nature, contrasts greatly with the earlier star-gazing scene with Edmund. There, we experience with Fanny and Edmund a sense of profound harmony, tranquillity, and beauty, elevated to a shared sense of transcendence by “the sublimities of nature” understood as an ordered cosmic whole, one “Mind.”

Here, by contrast, we experience not harmony but dissonance: Fanny’s reveries do not lift Mary into equally wondering, enthusiastic appreciation of nature as a universal whole or Mind. Mary is “untouched and inattentive”; she is distracted, absent-minded; her mind is wandering, much as she earlier jokes that young people’s minds “wander” when they are sitting in church (Chapter 9). She at first has “nothing to say” because she sees “no wonder in this shrubbery equal to seeing myself in it.” “Incurably selfish,” as she earlier cheerfully boasts about herself (Chapter 7), Mary is distracted by a vision of “self” that obscures any sense of a larger cosmic whole or “other” external to it.

Fanny, sensing this, first “[brings] back her own mind” from its reveries, and then attempts to bring Mary’s “mind” and attention out of its distractedness and inattentiveness by appealing to “what she thought must interest”: Mrs. Grant’s aesthetic “taste” in designing her garden walk. Fanny knows that both Mary and Henry Crawford are “aesthetes,” acutely attuned to the beauties of language and acting (Henry) and of music (Mary). The Crawfords appreciate all the “arts” – theatre, music, landscape gardening, architecture, fashionable dress – and are themselves “theatrical,” public performers as Fanny in her natural modesty, privacy, and humility is not.

Fanny’s ploy works: Mary is brought to respond, albeit “carelessly,” commenting that indeed she would never have expected a clergyman, a “mere nothing,” after all, to “aspire” “to a shrubbery or any thing of the kind.” She assumes clergymen are so humble, impoverished, and severely morally “virtuous” that they would never rise – or would that be, “fall”? – to the vanity and expense of an ornamental shrubbery in their gardens. (Edmund endorses such clerical severity in several places when he admits he’s too “plain-spoken” to be witty and amusing, his sermons aren’t delivered with sufficient “theatricality” of the sort that Henry has mastered, and he wants less “ornament” and more “utility” at Thornton Lacey.)

Yet Fanny takes equal if not even greater pleasure than the Crawfords in “prettiness” and “beauty,” that is, “aesthetics.” Her idea of “taste” however is not limited to merely aesthetic taste, the pleasures of the senses. For Fanny, the truly “beautiful” must have a kind of moral beauty about it: the moral beauty of “mind” that went into forming it with certain moral ends, intentions, or purposes behind it. She takes pleasure in Mrs. Grant’s moral character as expressed in the design of her garden: “There is such a quiet simplicity in the plan of the walk! – not too much attempted!” Most significantly, Mrs. Grant has recognized the inherent potential for “improvement” in something that may not have seemed to have much potential at all (“nothing but a rough hedgerow, … never thought of as anything, or capable of becoming anything”). Out of this apparent “nothing” she has made a garden walk that is both useful and beautiful: “it would be difficult to say whether most valuable as a convenience or as an ornament.”

This is of course an exact analogy of what Edmund’s tutelage in the Bertram household, together with her own reflections, have done for Fanny. Like Mrs. Grant, Edmund recognizes the inherent potential of what seemed a mere forgotten “nothing,” “a rough hedgerow,” to become “something,” “assisting the improvement of her mind, and extending its pleasures” (Chapter 2) such that she is now a young woman of whom it would be difficult to say whether she is most valuable for her usefulness or her newly emerging prettiness and graceful manners. Flourishing in her transplanted soil, she has blossomed into both: neither the merely useful “servant” Mrs. Norris wished to confine her to, nor just another polished but vacuously “ornamental” Bertram woman. Fanny has become that most morally beautiful and useful of human beings, a rationally critical yet also affectionately comforting “friend.”

The passage thus emphasizes the centrality of landscape gardening as one of several metaphors for education or “improvement” throughout the novel (the others being the Pulpit and the Theatre, extremes of severely moral vs. indulgently aesthetic education Austen rejects as such). Fanny notes that a certain species, the evergreen, flourishes better in Mrs. Grant’s garden than in her uncle’s because the soil there is better, like her own better flourishing when transplanted from Portsmouth to Mansfield Park. She also notes with wonder how plants “differing in the first rule and law of their existence” (deciduous vs. evergreen varieties) can nonetheless be nurtured by “the same soil and the same sun,” acknowledging by analogy the enormous “variety” of human nature, a natural inequality of potential that is perhaps shocking to our modern, egalitarian sensibilities. What is this “first rule and law of [our] existence” by which we “differ” both from other species and within our own?

Quite simply, our capacities of “mind” or memory, the faculty that Aristotle calls “nous.” In his view, as human beings, our highest capacity, our highest potential for human flourishing, health, and happiness – our highest pleasure, both moral and aesthetic – lies in the exercise of our minds, the activities of both practical and contemplative wisdom that Fanny so quietly yet strenuously “exercises” here and throughout the novel. Her own habits of mind, reflection, and memory are what she tries to instil in all the characters, attempting to give all of them, not merely Mr. Rushworth, a memory, a “brain,” a mind. This is the greatest force for “improvement” and “cure” in Mansfield Park; and what all of Austen’s novels are about: forming minds.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Laurel Ann Nattress, Elaine Bander, Maggie Arnold, and Hugh Kindred.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

August 29, 2014

Jane Austen’s “dead silence,” or, How Guilty is Sir Thomas Bertram?

Seventeenth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

This is Deborah Barnum’s second post for “An Invitation to Mansfield Park.” In the first, back in May, she surveyed the publishing history of the novel: “‘I have something in hand…’ – The Publishing of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park.”

Deborah is a former law librarian, now owner of Bygone Books, a closed shop of fine and collectible books in Burlington, Vermont. She is currently the regional coordinator for the JASNA Vermont Region, author of the Jane Austen in Vermont blog, and compiler of the annual “Jane Austen Bibliography” for the JASNA journal Persuasions On-Line .

Mansfield Park cover (2012)

She says she’s “a firm believer that Mansfield Park is Austen’s greatest work, that Austen felt that way herself, and that because the comedy is overshadowed by the weight of tragedy, it is too often on the bottom of everyone’s favorites list.” And she adds that she’s happy to see my efforts to correct this! I’m grateful to her for lending her support to the cause, too. I trust you all like and appreciate Mansfield Park more than you did, say, this time last year, when we were all wrapped up in celebrating Pride and Prejudice and hardly had time to spare a thought for Fanny Price. I know my own appreciation for the complexities of the novel has been increasing over these last few months, as I’ve been learning so much from all of you. Thank you all for participating in this celebration by reading, writing guest posts, and commenting, and thank you, Deborah, for taking on the daunting task of analyzing the “dead silence” that follows Fanny’s question about the slave trade.

Please visit Deborah’s blog Jane Austen in Vermont, where she has compiled all the passages from Mansfield Park that relate to the slave trade or the West Indies/Antigua. She has also posted a bibliography for further reading on the topic of Mansfield Park and slavery, in which you can find more details about all the sources mentioned in this post.

[Edmund to Fanny] “Your uncle is disposed to be pleased with you in every respect; and I only wish you would talk to him more. – You are one of those who are too silent in the evening circle.”

[Fanny] “But I do talk to him more that I used. I am sure I do. Did not you hear me ask him about the slave trade last night?”

“I did – and was in hopes the question would be followed up by others. It would have pleased your uncle to be inquired of farther.”

“And I longed to do it – but there was such a dead silence! And while my cousins were sitting by without speaking a word, or seeming at all interested in the subject, I did not like – I thought it would appear as if I wanted to set myself off at their expense, by shewing a curiosity and pleasure in his information which he must wish his own daughters to feel.”

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 21 (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1988)

Why I chose this passage, I have no idea! In these two words, “dead silence,” lies the crux of Mansfield Park – they are more analyzed as to the author’s intent than perhaps any other passage in all of Jane Austen. To understand this passage we need a thorough study of the slave trade and the history of the abolition movement in England; knowledge of the conditions of life for the owners and slaves in the West Indies, Antigua in particular; an in-depth view of Jane Austen’s personal connections to this slave-owning culture; some analysis of Austen’s political beliefs with thoughts that her allusions to the slave trade equal the condition of women in the early 19th century; and the generations of controversial critical analysis of this short passage. A heady task for a blog post!

So, I leave others to discuss these complex histories as I focus just on the “dead silence” passage and what Austen might be telling us about Sir Thomas and his connections to the slave trade, knowing full well it is a danger to take Jane Austen out of context – all is connected, each word essential to the whole, a tale told straight-forward but always with clues and nods to deeper meanings. I am doing Austen a disservice here, especially with this overcharged sentence, but I provide you here with a few questions to ponder the wider context of the novel and a bibliography for further reading.

Lord Mansfield, by Jean Baptiste van Loo, National Portrait Gallery (Source: Wikipedia)

Is Mansfield Park named after Lord Mansfield?

(You have perhaps all seen Belle, or read Paula Byrne’s book about the true story behind the movie?) William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield (1705-1793), and the Lord Chief Justice from 1756-1788, raised his two great nieces (see portrait below) Elizabeth Murray (whom Austen met a number of times, as noted in her letters) and Dido Belle, the daughter of Mansfield’s nephew John Lindsay and a slave named Maria Belle. In 1772, Mansfield ruled in the James Somerset case (also spelled Somersett) that no former slave could be removed from Britain and sold back into slavery. This and his ruling in the Zong case (the case portrayed in the movie) that human beings were not “property” were viewed as the beginning of the end of slavery on British soil.

Austen surely knew of Mansfield’s rulings, as we know from her letters that she read Thomas Clarkson’s History of the Rise, Progress and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade (1808) (see Letter 24, January 1813), and very likely chose this name for the house in Mansfield Park to make a clear statement of her slavery sentiments. (However, it is useful to look to John Wiltshire in his “Decolonizing Mansfield Park” where he gives us these two other options for the title: there is a Lady Mansfield who stays in Mansfield House in Austen’s favorite novel, Richardson’s Sir Charles Grandison (1753); and a book titled Amelie Mansfield, a French novel by Sophie Cottin, was first published in 1802.)

Elizabeth Murray and Dido Belle (Source: NPR)

Is Austen equating the slave trade to the condition of women in English society?

Jane Austen must have known of Hannah More’s 1805 pamphlet The White Slave Trade: Hints toward Framing a Bill for the Abolition of the White Female Slave Trade, in the Cities of London and Westminster, about young women “coming out” into society. The introduction of the “slave trade” into the text of Emma (see quotes on my blog) is even more telling here, equating the life of a slave with that of a governess, each really no more than property and badly treated.

Can the reader apply the metaphor of Mansfield Park = the State of the Nation, as many domestic novels of the time did? Fanny as slave, Sir Thomas as landlord/plantation owner, Mrs. Norris as his cruel agent – all fails when the Master is absent.

Was Austen a colonialist, an abolitionist, or both?

Edward Said’s interpretation of Mansfield Park (see bibliography) is the starting point for all discussion of this topic: he posits that Jane Austen was a product of her time, and the true daughter of an England that colonized and brutalized, and that she made only this off-hand nod to the slave trade to underscore her own lack of interest in it. That is, by returning her characters at tale’s end to the “tolerable comfort” of a restored Mansfield Park, Austen seems to condone the way of life it represents. We can read what she read, know what the sentiments were to slavery among her family and close connections, but we can only conjecture what she was intending in Mansfield Park. Is this novel a book about slavery? Or is this passage nothing more than a brief reference to the realities of life in England at the time Austen was writing?

Broadside: Description of a Slave Ship (from Clarkson’s book)

The Scene of the “dead silence”

Edmund and Fanny are discussing the change in the atmosphere at Mansfield Park since Sir Thomas’ return: all is “sameness and gloom,” and Edmund is lamenting the loss of the Parsonage company and their liveliness. Fanny (who we know to be happier without the Crawfords!), responds by saying

“the evenings do not appear long to me. I love to hear my uncle talk of the West Indies. I could listen to him for an hour together. It entertains me more than many other things have done….”

(Recall Fanny’s feelings of “dreadful duty” when first appearing before her uncle on his return.)

Edmund continues in response with the rather creepy chat about Fanny’s personal charms – her face, her figure – relating what his father has said of Fanny to him, and then we arrive at the “slave trade” comment (which is a tad ironic after the description of Fanny as a commodity – something to look at, appraise, and perhaps buy and sell?).

Then we have Fanny’s “dead silence” (such a strong phrase isn’t it?), followed by Edmund’s “it would have pleased your uncle to be inquired of further.” Fanny explains her reluctance to question further because she was afraid of slighting her cousins in their indifference to their father: “ – I thought it would appear as if I wanted to set myself off at their expense, by shewing a curiosity and pleasure in his information which he must wish his own daughters to feel.”

And then I find this very telling: Edmund goes on to talk of Mary Crawford, as uninterested in the slave trade as they all were the night before. (I am always rather appalled at Edmund. He might offer Fanny her only kindnesses, but he often forgets her quite easily, just as Tom Bertram does. Early on he finds her an “interesting object” [my emphasis]; he gives her horse to Mary without a thought; he never seems to stand up for her when she is constantly badgered by Mrs. Norris; he wishes her to marry Henry as much for himself to have a closer connection to Mary; and why, oh why, does he never insist on a fire in her room?? – but alas! This is a topic for another post….)

Who is Sir Thomas?

Harold Pinter as Sir Thomas (Patricia Rozema’s MP film, 1999)

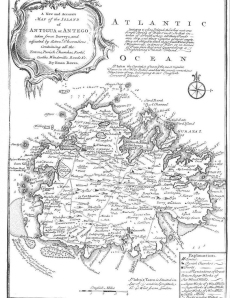

The lack of response, the “dead silence,” to Fanny’s question has sent critics off into such contradictory analysis, one wonders if we have all read the same book. Jane Austen gives us very little to go on. We are told only that Mansfield is a “modern built house,” that Sir Thomas is a member of Parliament (but we don’t know if he is part of the established landed gentry or newly wealthy – he is awfully eager to marry off Maria to Mr. Rushworth with his money and connections), and that he has an estate in Antigua. We don’t know how long he has owned the estate, or whether indeed it is a sugar plantation dependent upon the slave economy (most critics assume that it is), or how dependent Mansfield Park is on the income from this estate (Mrs. Norris: “Sir Thomas’s means will be rather straitened, if the Antigua estate is to make such poor returns”). We don’t know exactly the dating of the action, which would help us understand the historical context of the tale.

All we do know is that Sir Thomas needs to go to Antigua to deal with issues that are causing “such poor returns.” He expects to be gone a year. Has he gone before, we might wonder? We only hear of his being gone to Town. He is, in the event, gone for two years, this fact often missed in the reading – he returns a changed man, physically and emotionally, and seems to enjoy talking about his time there (recall his comments later in the novel on the “balls of Antigua”). There was a life there among the colonial gentry and Fanny, unlike the rest of the family, enjoys hearing him talk of it.

So how do we look at Sir Thomas? He is the Master of Mansfield Park; he reigns over all, not unlike the Master on a slave-hold. The major issue of the West Indies plantations was the absentee landlord. The agent or overseer was often the abuser of the slaves and the money-matters and this was where many troubles began: sickness and loss of workers, slave rebellions, etc. Recall here Sir Thomas’s own words on the clergyman needing to live among his parishioners: “… if he does not live among his parishioners and prove himself by constant attention their well-wisher and friend, he does very little for their good or his own.”

Sir Thomas goes to Antigua to solve whatever problems are going on, and in so doing ironically leaves his English home in the hands of a cruel overseer, Mrs. Norris. Why she is so named is another of the Mansfield Park speculations: is she named for the anti-abolitionist slave trader John Norris of Liverpool (referred to by Clarkson), or as Wiltshire points out, is this name a satirical turn on “nourrice” / “norrice,” the French / English word for “to nourish” – certainly not our Mrs. Norris!

Why Antigua?

Map of Antigua (source: Gregson Davis article)

Having Sir Thomas absent from Mansfield for two years is of course a plot device. Austen could have used other storylines to send him away, but she does not – she sends him to Antigua. In Sir Thomas’s absence, all manner of ills beset Mansfield Park: the ridiculous Rushworth; the interloping Crawfords who disturb the peace of the “goodly heritage” (though we all are really glad they showed up!); the sexual undercurrents of the theatricals; Mrs. Norris’s cruel (though often funny) antics; Edmund’s obsession with Mary; Tom’s freedom from his father and his duties as elder son; and Henry’s harassing manipulation of Fanny – and the absentee Landlord/Master returns to find all in disarray.