Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 33

August 15, 2014

Jane Austen: Dramatist

Fifteenth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

This week’s guest post is by David Monaghan, Professor Emeritus at Mount Saint Vincent University in Halifax, Nova Scotia. He’s the author of Jane Austen: Structure and Social Vision, the editor of Jane Austen in a Social Context and New Casebooks: “Emma” (all published by Macmillan) and co-author with John Wiltshire and Ariane Hudelet of The Cinematic Jane Austen (McFarland). When I was a graduate student at Dalhousie I had the good fortune to audit his class on Austen and film, and I’m very happy to introduce his post on that “ranting young man,” Mr. Yates.

“Then poor Yates is all alone,” cried Tom. “I will go and fetch him. He will be no bad assistant when it all comes out.”

“Then poor Yates is all alone,” cried Tom. “I will go and fetch him. He will be no bad assistant when it all comes out.”

To the theatre he went, and reached it just in time to witness the first meeting of his father and his friend. Sir Thomas had been a good deal surprised to find candles burning in his room; and on casting his eye round it, to see other symptoms of recent habitation and a general air of confusion in the furniture. The removal of the bookcase from before the billiard-room door struck him especially, but he had scarcely more than time to feel astonished at all this, before there were sounds from the billiard-room to astonish him still farther. Some one was talking there in a very loud accent; he did not know the voice – more than talking – almost hallooing. He stept to the door, rejoicing at that moment in having the means of immediate communication, and opening it, found himself on the stage of a theatre, and opposed to a ranting young man, who appeared likely to knock him down backwards. At the very moment of Yates perceiving Sir Thomas, and giving perhaps the very best start he had ever given in the whole course of his rehearsals, Tom Bertram entered at the other end of the room; and never had he found greater difficulty in keeping his countenance. His father’s looks of solemnity and amazement on this his first appearance on any stage, and the gradual metamorphosis of the impassioned Baron Wildenheim into the well-bred and easy Mr. Yates, making his bow and apology to Sir Thomas Bertram, was such an exhibition, such a piece of true acting as he would not have lost upon any account. It would be the last – in all probability the last scene on that stage; but he was sure there could not be a finer. The house would close with the greatest eclat.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 19 (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003)

In order to properly explain my admiration for the paragraph that presents Sir Thomas Bertram’s on-stage encounter with Mr. Yates, I need to first go back a few pages and take a look at another theatrical moment. This occurs as the various dynamics that develop in the course of the amateur theatricals organized by the young people at Mansfield Park reach a point of crisis with Fanny Price’s capitulation to demands that she take a part in the play Lovers’ Vows. As rehearsals start up again and Fanny, stunned by the enormity of her moral compromise, experiences the “tremors of a most palpitating heart,” so Jane Austen saves the day with a deus ex machina in the form of Sir Thomas Bertram’s unexpected return from Antigua. Not only is Fanny spared but the theatricals and the dangerous relationships for which they have provided a cover are brought to a rapid conclusion.

In order to properly explain my admiration for the paragraph that presents Sir Thomas Bertram’s on-stage encounter with Mr. Yates, I need to first go back a few pages and take a look at another theatrical moment. This occurs as the various dynamics that develop in the course of the amateur theatricals organized by the young people at Mansfield Park reach a point of crisis with Fanny Price’s capitulation to demands that she take a part in the play Lovers’ Vows. As rehearsals start up again and Fanny, stunned by the enormity of her moral compromise, experiences the “tremors of a most palpitating heart,” so Jane Austen saves the day with a deus ex machina in the form of Sir Thomas Bertram’s unexpected return from Antigua. Not only is Fanny spared but the theatricals and the dangerous relationships for which they have provided a cover are brought to a rapid conclusion.

However, the decisiveness of the moment is illusory. Sudden interventions from outside are not the way things work in a Jane Austen novel. The role of deus ex machina is one that fits the patriarchal Sir Thomas’s self-image but Austen immediately calls its validity into question when, rather than follow theatrical convention and drop Sir Thomas into the centre of the action, she keeps him offstage, leaving it to the hysterical Julia to announce his arrival. Even more significant, we have only reached the end of the first volume and, beyond terminating the play, nothing of any real significance is resolved by Sir Thomas’s return.

In this instance, then, Austen is mocking theatrical convention and using it to point out the differences between her approach to story-telling – where resolutions are developed out of a gradual and complex process involving social interactions and decisions based on serious reflection – and one that relies on arbitrary and unexpected interventions from outside. How Austen might have actually used theatrical convention had she been writing plays rather than novels is indicated by the brief incident on which I mainly want to focus.

Even here, Austen never entirely strays from novelistic conventions and one of the delights of the scene is her decision, without precedent elsewhere in the novel, to filter the action through the consciousness of Tom, the character best qualified to see the funny side of his father’s discomfiture. Nevertheless, it is Austen’s exploitation of its theatrical possibilities that makes this scene, set appropriately on a stage, stand out.

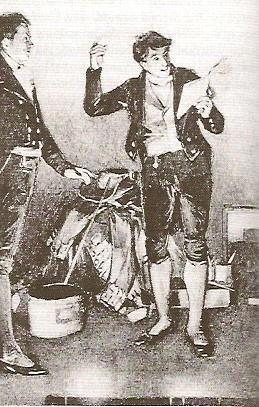

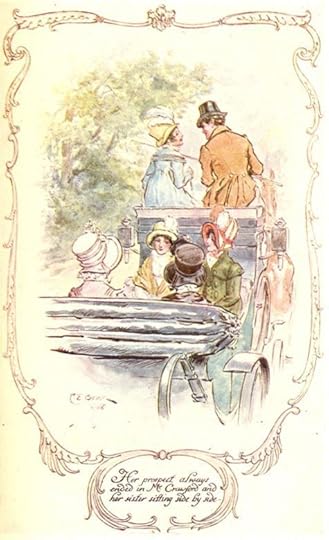

“Mr. Yates rehearsing,” from an 1892 edition of Mansfield Park

First, building on her earlier debunking of the deus ex machina trope, Austen creates a few moments of dramatic business that give a humorous but pointed visual expression to Sir Thomas’s limitations as an authority figure. Initially bewildered by the chaotic state of his own room and the “hallooing sounds” emanating from next door, Sir Thomas enters the billiard room only to find himself on a stage where he is “opposed to a ranting young man, who appeared likely to knock him down backwards.”

Second, she again demonstrates her powers of visual representation in describing the “gradual metamorphosis [from] the impassioned Baron Wildenhaim into the well-bred and easy Mr. Yates,” a performance which is for Tom, here serving as a surrogate audience, “such a piece of true acting as he would not have lost on any account.” Delightfully comic in themselves, these few words are also extremely effective in pointing up the broader social implications of the emphasis placed on role-playing during the theatricals.

For a few brief moments, then, we gain a real insight into the type of plays that Austen might have written had she chosen a different means of artistic expression. Not for Austen, the contrived effects and melodramatic emotions of a theatre based on the tired conventions of classical drama. On the contrary, hers would have been witty and profound social comedies that allied the brilliant dialogue frequently to be found in her novels to a keen visual sense. It is the sheer delight of seeing a great artist switch briefly but with great effect into a different register that makes the paragraph discussed above my favourite in Mansfield Park.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park. Coming soon: guest posts by Diana Birchall, Deborah Barnum, Laurel Ann Nattress, and Lorrie Clark. Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party!

August 11, 2014

A Summer (Reading) Marathon

“A girl came out of lawyer Royall’s house, at the end of one street of North Dormer, and stood on the doorstep.” This is the first line of Edith Wharton’s 1917 novel Summer, a line that suggests something new and interesting is about to happen to that girl who’s about to venture out into the world. She sees a young man, a stranger, whose straw hat is lifted by the wind and blown into the duck-pond, and it’s easy to guess her encounter with this young man will change her life.

“A girl came out of lawyer Royall’s house, at the end of one street of North Dormer, and stood on the doorstep.” This is the first line of Edith Wharton’s 1917 novel Summer, a line that suggests something new and interesting is about to happen to that girl who’s about to venture out into the world. She sees a young man, a stranger, whose straw hat is lifted by the wind and blown into the duck-pond, and it’s easy to guess her encounter with this young man will change her life.

She goes out into the world, but only as far as the town library where she works, and where she’ll meet the handsome stranger when he enters to look for books on the history of houses in the area. This library is not the gateway to knowledge about architecture or anything else, however, but a “prison-house,” a “vault-like room” with “rows of rusty bindings” and “tall cobwebby bindings” – and no card catalogue.

The library in North Dormer is in disrepair, but even so, it reminds me of the grand library in Undine Spragg’s hôtel in Paris at the end of The Custom of the Country, in which the bookcases are all locked because “the books were too valuable to be taken down.” I wrote a blog post about that passage a couple of years ago because I was fascinated by Wharton’s vision of hell as a library in which no one is able to read or write.

The library in North Dormer is in disrepair, but even so, it reminds me of the grand library in Undine Spragg’s hôtel in Paris at the end of The Custom of the Country, in which the bookcases are all locked because “the books were too valuable to be taken down.” I wrote a blog post about that passage a couple of years ago because I was fascinated by Wharton’s vision of hell as a library in which no one is able to read or write.

When the girl in Summer, Charity Royall, thinks about the founder of the “queer little brick temple” called “The Honorius Hatchard Memorial Library,” she wonders “if he felt any deader in his grave than she felt in his library.” Twice in the first few pages of the novel, Charity says to herself, “How I hate everything!” Yet she can’t help being interested in the stranger – and “The fact that, in discovering her, he lost the thread of his remark, did not escape her attention.”

Summer and Ethan Frome, the two short novels Wharton set in western Massachusetts, were both more controversial than any of her other books (according to Candace Waid in Edith Wharton’s Letters from the Underworld). Known as “the hot Ethan,” Summer is the story of a passionate love affair and its consequences. Wharton, says Marilyn French in her introduction to the Scribner edition, “has written a novel that is a clamorous and ecstatic affirmation of the joy of sexual love no matter what it costs.” And, she adds, “It does cost.”

Summer and Ethan Frome, the two short novels Wharton set in western Massachusetts, were both more controversial than any of her other books (according to Candace Waid in Edith Wharton’s Letters from the Underworld). Known as “the hot Ethan,” Summer is the story of a passionate love affair and its consequences. Wharton, says Marilyn French in her introduction to the Scribner edition, “has written a novel that is a clamorous and ecstatic affirmation of the joy of sexual love no matter what it costs.” And, she adds, “It does cost.”

The Mount, Edith Wharton’s home in Lenox, MA, is hosting a marathon reading of Summer tomorrow, August 12th, and I wish I could be there. “Summer afternoon – summer afternoon.” As Wharton’s good friend Henry James said, “those have always been the two most beautiful words in the English language” (quoted in Chapter 10 of Wharton’s autobiography A Backward Glance). Wouldn’t it be lovely to spend a summer afternoon reading Summer in the Berkshires?

The Mount, Edith Wharton’s home in Lenox, MA, is hosting a marathon reading of Summer tomorrow, August 12th, and I wish I could be there. “Summer afternoon – summer afternoon.” As Wharton’s good friend Henry James said, “those have always been the two most beautiful words in the English language” (quoted in Chapter 10 of Wharton’s autobiography A Backward Glance). Wouldn’t it be lovely to spend a summer afternoon reading Summer in the Berkshires?

Edith Wharton died on this date, August 11th, in 1937.

August 9, 2014

The First Three Months of the Mansfield Park Party!

With three months of guest posts on Mansfield Park, it’s possible that you might have missed a post or two. Maybe you missed the week where we looked at the link between a high fat diet and sudden death, or the weeks where we talked about whether Mary Crawford is “as bad as [her] brother,” or the weeks where we discussed whether Jane Austen could possibly have been talking about sodomy and whether she meant for us to understand those spikes at Sotherton literally or figuratively.

Maybe you’re just discovering the series, in which case — welcome! Or maybe you’ve been following along, but you’d like to go back to the first post on the opening paragraph and read everything in order.

Here’s a guide to everything that’s appeared so far in “An Invitation to Mansfield Park.”

Part 1: “Clarity and Complexity: Mansfield Park Begins,” by Lyn Bennett:

Far from famous, Mansfield Park’s first line doesn’t offer the memorable simplicity of “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.”

Part 2: “Adopting Affection,” by Judith Thompson:

Part 2: “Adopting Affection,” by Judith Thompson:

I have a secret to confess. I’ve always liked Fanny Price, even though she is generally agreed to be the most tight-ass heroine of the most conservative novelist of the romantic era, whereas I’m passionately in love with one of that era’s most kick-ass revolutionaries, the radical activist and atheist John Thelwall.

Part 3: “First Impressions of Fanny Price,” by Jennie Duke:

… with “nothing to disgust,” “no glow,” the description is largely about what she is not.

Part 4: “Why Tom Bertram is right that Dr. Grant will ‘soon pop off,’“ by Cheryl Kinney:

It would not be until the next century that the association between diet and sudden death was firmly and scientifically established. Jane Austen, without formal medical training, required no such length of time to come to the correct medical conclusion – that people who must have their “palate consulted in everything” (Chapter 11) and who indulge in “three great institutionary dinners in one week” (Chapter 48) would be at risk to suffer apoplexy and death.

Part 5: “Mary Crawford and the Mansfield ‘cure,’“ by Katie Davis:

This brief passage in Chapter 5 calls our attention to a few of the central questions of Austen’s novel: to what extent can the opinions and habits of fully-formed adults be changed – or “cured” – by entering into community with people whose opinions and habits are, in crucial ways, totally different? What is required for such a transformation?

Part 6: “Scattering Seeds of Kindness,” by Mary C.M. Phillips:

Part 6: “Scattering Seeds of Kindness,” by Mary C.M. Phillips:

Random acts of kindness may often come from the most unlikely of characters. An ambitious social climber might have a better eye for injustice than even the most sincere clergyman. To some, Mary Crawford, the charming antagonist of Mansfield Park, is considered shallow, immoral and unprincipled. But not to me.

Part 7: “A Gentleman’s Improvements: Mr. Rushworth, Humphry Repton, Fanny Price and Fashionable Landscaping,” by Jacqui Grainger:

Wealth and status, power and the responsible use of money are persistent themes in the work of Jane Austen. Austen uses the idea of improvement to reflect varying attitudes to money and its appropriate disposal.

Part 8: “Rears and Vices,” by Devoney Looser:

Part 8: “Rears and Vices,” by Devoney Looser:

To suggest that there is sex in Mansfield Park – at least in the way that recent film and television adaptations tend to – is rubbish. … That said, there is sexuality (even dangerous, illicit sex) in Mansfield Park, albeit between the lines.

Part 9: “Something from Nothing,” by Mary Lu Roffey Redden:

Mary Crawford’s reply to Edmund’s planned ordination may be cynical about the church – “A clergyman is nothing” – but she is also surprisingly insightful about issues that still resonate for clergy: what is the difference between a vocation that may mean relative poverty and social obscurity and a profession in which one seeks advancement, a good salary and some social standing?

Part 10: “The Fatal Mistake,” by Deborah Yaffe:

Part 10: “The Fatal Mistake,” by Deborah Yaffe:

How do we know that Maria’s unwillingness to wait for Rushworth to bring her the key to the gate prefigures her unwillingness to remain faithful to him within the fenced wilderness of marriage?

Partly, of course, we know all this because we are post-Freudian readers, primed to see keys and spikes and tears as sexual codes. How, then, do we know that the pre-Freudian Jane Austen had this metaphorical reading in mind?

Part 11: “Dr. Grant’s Green Goose,” by Julie Strong:

Dr. Grant is a grouchy gourmand whom Austen summari ly dispatches at the close of the novel.

ly dispatches at the close of the novel.

Part 12: “Is Edmund Bertram right about anything?” by Juliet McMaster:

… what interests me is the extent to which Edmund’s piece of wisdom may actually apply to himself. I have long believed that Edmund, even while he consciously courts Mary Crawford, is equally in love with Fanny – or indeed even more so.

Part 13: “Angry White Female: An Apology for Mrs. Norris,” by George Justice:

In a novel with unclear heroes and heroines, Mrs. Norris is—or would seem to be—an unambiguous villain. She is mean-spirited, self-serving, erroneous, obsequious: fully hideous.

Part 14: “Austens Ands, Ors, and Buts,” by Lynn Festa:

Part 14: “Austens Ands, Ors, and Buts,” by Lynn Festa:

Conjunctions both join and sunder: they yoke individual words or the separate clauses of a sentence together, but they are also physically interposed between the parts they are supposed to unite. In this passage, conjunctions serve as barriers as much as bridges: “and” fails to conjoin; “or” fails to offer viable alternatives; and “but” fails to make an exception or mitigate the lack of connection it seeks to overcome.

All the contributions are also listed on this page, “An Invitation to Mansfield Park,” along with many other essays on the novel published elsewhere on the web. If you’re on Pinterest, you might be interested in my Mansfield Park board. And I also talk about the novel on Facebook and Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley).

Many thanks to everyone who has contributed to the series so far, by writing guest posts, by reading them, and by commenting on them. I’m learning so much about this brilliant but often under-appreciated novel, and I’m so glad you’re all joining me in celebrating the 200th anniversary.

Many thanks to everyone who has contributed to the series so far, by writing guest posts, by reading them, and by commenting on them. I’m learning so much about this brilliant but often under-appreciated novel, and I’m so glad you’re all joining me in celebrating the 200th anniversary.

You won’t want to miss the upcoming posts in the series, which runs to the end of December. Coming soon: David Monaghan, Diana Birchall, Deborah Barnum, Laurel Ann Nattress, Lorrie Clark, Elaine Bander, Maggie Arnold, Hugh Kindred, Natasha Duquette, Margaret Horwitz, Sarah Woodberry, Joyce Tarpley, Syrie James, John Baxter, Sharon Hamilton, Sara Malton, Maggie Sullivan, Amy Patterson, Karen Doornebos, Lynn Shepherd, Elisabeth Lenckos, Sheryl Craig, Ryder Kessler, and Sheila Johnson Kindred.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party!

P.S. The schedule for Mansfield Park guest posts is full – but if you’d like to write a guest post on Emma in 2016, let me know, as I’ll probably want to celebrate that bicentennial, too…. Write to me (semsley at gmail dot com) or leave a comment below if you think we should have a party here for Emma. I’m already excited about the JASNA 2016 AGM in Washington, DC: “Emma at 200: ‘No One But Herself.’”

P.S. The schedule for Mansfield Park guest posts is full – but if you’d like to write a guest post on Emma in 2016, let me know, as I’ll probably want to celebrate that bicentennial, too…. Write to me (semsley at gmail dot com) or leave a comment below if you think we should have a party here for Emma. I’m already excited about the JASNA 2016 AGM in Washington, DC: “Emma at 200: ‘No One But Herself.’”

August 8, 2014

Austen’s Ands, Ors, and Buts

Fourteenth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Lynn Festa teaches in the English department at Rutgers University. I first met her more than a decade ago, when she was teaching in the English department at Harvard University and I was teaching in Harvard’s writing program, and it was great to reconnect with her at the JASNA AGM in New York in 2012. I’m excited to hear her plenary lecture on “The Noise in Mansfield Park ” at this year’s AGM in Montreal.

(If you’re interested in noise, and its absence, in Mansfield Park, you may also be interested in the winning essays from this year’s JASNA essay contest – the topic was “Silence in Mansfield Park.”)

(If you’re interested in noise, and its absence, in Mansfield Park, you may also be interested in the winning essays from this year’s JASNA essay contest – the topic was “Silence in Mansfield Park.”)

A specialist in eighteenth-century British and French literature, Lynn is the author of a book on sentimental literature and empire, as well as essays on topics ranging from wigs (why did so many men shave their heads to wear someone else’s hair?) and cosmetics to early children’s literature featuring talking animals and the reasons behind a Parliamentary tax on dogs. She’s currently finishing a book on eighteenth-century definitions of humanity. I’m very pleased to introduce her guest post on conjunctions in Chapter 17 of Mansfield Park. Who knew there was so much to say about the words “and,” “or,” and “but”?

A specialist in eighteenth-century British and French literature, Lynn is the author of a book on sentimental literature and empire, as well as essays on topics ranging from wigs (why did so many men shave their heads to wear someone else’s hair?) and cosmetics to early children’s literature featuring talking animals and the reasons behind a Parliamentary tax on dogs. She’s currently finishing a book on eighteenth-century definitions of humanity. I’m very pleased to introduce her guest post on conjunctions in Chapter 17 of Mansfield Park. Who knew there was so much to say about the words “and,” “or,” and “but”?

Julia did suffer, however, though Mrs. Grant discerned it not, and though it escaped the notice of many of her own family likewise. She had loved, she did love still, and she had all the suffering which a warm temper and a high spirit were likely to endure under the disappointment of a dear, though irrational hope, with a strong sense of ill-usage. Her heart was sore and angry, and she was capable only of angry consolations. The sister with whom she was used to be on easy terms, was now become her greatest enemy; they were alienated from each other, and Julia was not superior to the hope of some distressing end to the attentions which were still carrying on there, some punishment to Maria for conduct so shameful towards herself, as well as towards Mr. Rushworth. With no material fault of temper, or difference of opinion, to prevent their being very good friends while their interests were the same, the sisters, under such a trial as this, had not affection or principle enough to make them merciful or just, to give them honour or compassion. Maria felt her triumph, and pursued her purpose careless of Julia; and Julia could never see Maria distinguished by Henry Crawford, without trusting that it would create jealousy, and bring a public disturbance at last.

Fanny saw and pitied much of this in Julia; but there was no outward fellowship between them. Julia made no communication, and Fanny took no liberties. They were two solitary sufferers, or connected only by Fanny’s consciousness.

Fanny saw and pitied much of this in Julia; but there was no outward fellowship between them. Julia made no communication, and Fanny took no liberties. They were two solitary sufferers, or connected only by Fanny’s consciousness.

The inattention of the two brothers and the aunt to Julia’s discomposure, and their blindness to its true cause, must be imputed to the fulness of their own minds. They were totally preoccupied. Tom was engrossed by the concerns of his theatre, and saw nothing that did not immediately relate to it. Edmund, between his theatrical and his real part, between Miss Crawford’s claims and his own conduct, between love and consistency, was equally unobservant; and Mrs. Norris was too busy in contriving and directing the general little matters of the company, superintending their various dresses with economical expedient, for which nobody thanked her, and saving, with delighted integrity, half-a-crown here and there to the absent Sir Thomas, to have leisure for watching the behaviour, or guarding the happiness of his daughters.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 17 (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2006)

In the three incisive paragraphs that close Chapter 17, Austen offers an anatomy of jealousy and its impact of the Bertram family, dissecting both the limited insight individual characters have into others and the ease with which sexual rivalry ruptures already-fragile familial bonds. The rage and hurt of Julia Bertram at witnessing her sister’s flirtation with Henry Crawford pass unperceived by almost all – the passage opens with the almost-universal failure to understand that “Julia did suffer” – but Austen’s omniscient narrator skillfully enters into minds that fail to understand other minds in order to help us sympathetically grasp the failure of sympathy.

It is striking that in a passage on the failure to connect Austen uses so many conjunctions: twenty-one “ands,” six “ors,” and one “but.” Conjunctions both join and sunder: they yoke individual words or the separate clauses of a sentence together, but they are also physically interposed between the parts they are supposed to unite. In this passage, conjunctions serve as barriers as much as bridges: “and” fails to conjoin; “or” fails to offer viable alternatives; and “but” fails to make an exception or mitigate the lack of connection it seeks to overcome.

“And” is an unstable bond in a world in which couples keep turning into triangles. As a result of Henry Crawford’s flirtation with Maria, the reciprocity of sympathy – the connection promised by “and,” the mutual interchange of “or” – becomes perverted into the reciprocity of revenge, a kind of arms-race of ill-will between two sisters now become each others’ “greatest enemy.” An exultant Maria gloats over Julia, while Julia wishes future ills to fall upon Maria’s head in anticipation of the novel’s ending. (It is perhaps worth noting how little of Julia’s rage is directed at Henry Crawford who, here as in the closing chapter, gets off more or less scot-free.) The “easy terms” on which the sisters had hitherto subsisted are dissolved with equal ease: they have not been fortified by the necessary labor that builds true bonds.

“Her prospect always ended in Mr. Crawford and her sister sitting side by side.” Illustration by C.E. Brock (www.mollands.net).

In an exquisitely crafted sentence, Austen describes a sisterly relation that flourishes only in the absence of impediment, ordering the words in such a way that the reader must reverse the seeming meaning as she progresses through the sentence. The sentence begins with the appearance of harmony – “With no material fault of temper, or difference of opinion,” – before reversing the affirmation midway through by presenting positive traits as negative barriers – “ to prevent their being very good friends while their interests were the same.”

Austen recasts friendship as a coalescence of interests, whose dissolution produces war: “the sisters, under such a trial as this, had not affection or principle enough to make them merciful or just, to give them honour or compassion.” The “or” which typically creates alternatives – “affection or principle” – here instead forecloses options: the Bertram girls possess neither the tender virtue of “mercy” nor the stern principle of “justice,” neither the noble merit of “honour” nor the sentimental relenting of “compassion.” They lack, in other words, the qualities associated both with an older aristocratic order and with the new age of sensibility. In offering an exhaustive array of possible compensating traits (“or,” “or,” “or”), the narrator exposes the lack of redemptive values in the girls.

Likewise in the final paragraph, utter disregard for others is the inevitable by-product of self-absorption: for Tom, Edmund, and Mrs. Norris, the “fullness of their own minds” leaves no room for anything beside themselves. Here too the conjunction “and” fails to conjoin, as Edmund finds himself caught between “his theatrical and his real part, between Miss Crawford’s claims and his own conduct, between love and consistency” – a split subject in every sense of the word. No different from Tom and Mrs. Norris (at least in this instance), Edmund is revealed to be so full of himself (or his selves) that he cannot register the feelings of his sister.

Interposed between Julia’s and Maria’s malevolent insight into each other’s minds and the self-absorbed obliviousness of Tom, Edmund, and Mrs. Norris is a brief three-sentence paragraph about Fanny, representing the possibility of compassionate understanding. Although Mansfield Park often exploits free indirect discourse to present ironic critique of Fanny and other characters, this passage presents a peculiar moment of complicity between the narrator and the heroine. After the reader has been given privileged insight into the relations between Julia and Maria, the narrator describes what Fanny has perceived. “Fanny saw and pitied much of this in Julia; but there was no outward fellowship between them.”

Even Fanny’s insight and compassion cannot overcome the abyss that separates the two women. The presence of the word “outward” in the sentence suggests the possibility of a form of inward fellowship, and of course Julia and Fanny share a common experience, for Fanny is afflicted with a jealousy every bit as all-consuming as that which devours Julia. Yet the parallels in experience do not produce commonality: “Julia made no communication, and Fanny took no liberties. They were two solitary sufferers, or connected only by Fanny’s consciousness.” The balance of clauses of the two sentences tips first on the fulcrum of and and then on an or. If the “and” here serves as a conjunction that fails to conjoin, the “or” performs the non-reciprocity of an empathy which fails to connect.

Yet Fanny’s delicate and tactful refusal to overreach into another’s consciousness is countered by the narrator’s relentless incursion: the shared consciousness is not only Fanny’s, but also the narrator’s and the reader’s. Austen, in her masterful yet merciless dissection of the Bertram family, relentingly proffers to her reader the possibility of another form of conjunction: the one that enables us, like Fanny, to enter into minds that are unable to enter into the minds of those around them.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park. Coming soon: guest posts by David Monaghan, Diana Birchall, Deborah Barnum, and Laurel Ann Nattress. Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party!

Tomorrow marks the three-month anniversary of this celebration of Mansfield Park — watch for a special blog post listing all the guest posts that have appeared so far in the series. Just in case you need to catch up on your reading…. I wouldn’t want anyone to miss out on the fascinating conversations that have been happening here over the last three months.

August 1, 2014

Angry White Female: An Apology for Mrs. Norris

Thirteenth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

“I said, ‘Mansfield Park is my least favorite, and I dislike it because I dislike Fanny Price. She’s too much like me. She’s boring.”

This is the person I’m going to marry, George thought.

If you’ve read Deborah Yaffe’s book Among the Janeites, you’ll recognize this description of the first time Devoney Looser and George Justice met. They’ve now been married for eighteen years, during which time they’ve given many joint presentations on Jane Austen. This past spring they also taught a class on Austen together at Arizona State University. Devoney wrote a guest post for my Mansfield Park series on “Rears and Vices” a few weeks ago, which prompted “a great deal of conversation” (to borrow Anne Elliot’s phrase), and today I’m happy to introduce George’s post on Mrs. Norris.

If you’ve read Deborah Yaffe’s book Among the Janeites, you’ll recognize this description of the first time Devoney Looser and George Justice met. They’ve now been married for eighteen years, during which time they’ve given many joint presentations on Jane Austen. This past spring they also taught a class on Austen together at Arizona State University. Devoney wrote a guest post for my Mansfield Park series on “Rears and Vices” a few weeks ago, which prompted “a great deal of conversation” (to borrow Anne Elliot’s phrase), and today I’m happy to introduce George’s post on Mrs. Norris.

It had never occurred to me to defend Mrs. Norris, one of the Austen characters readers love to hate. Adelle Waldman recently voted for her as the “greatest fictional character of all time,” because “What makes her so brilliant – and so chilling – is that her brand of malevolence is so ordinary; she really has no idea that she’s a monster.”

But when I mentioned to George the other day that we haven’t talked about Mrs. Norris very much so far in “An Invitation to Mansfield Park ,” he immediately started writing about her. I’m very interested to hear what you think about his analysis of her character.

George Justice is Dean of Humanities in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and Associate Vice President for Humanities and Arts in the Office of Knowledge Enterprise Development at Arizona State University. A specialist in eighteenth-century British literature, he’s the author and editor of scholarship on the literary marketplace, authorship, and women’s writing. Most recently, he edited Jane Austen’s

Emma

for the Norton Critical Editions series. Prior to going to ASU, he taught at the University of Pennsylvania, Marquette University, Louisiana State University, and the University of Missouri, where he also served as Vice Provost for Advanced Studies and Dean of the Graduate School.

George Justice is Dean of Humanities in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and Associate Vice President for Humanities and Arts in the Office of Knowledge Enterprise Development at Arizona State University. A specialist in eighteenth-century British literature, he’s the author and editor of scholarship on the literary marketplace, authorship, and women’s writing. Most recently, he edited Jane Austen’s

Emma

for the Norton Critical Editions series. Prior to going to ASU, he taught at the University of Pennsylvania, Marquette University, Louisiana State University, and the University of Missouri, where he also served as Vice Provost for Advanced Studies and Dean of the Graduate School.

In a recent blog entry in The Paris Review, Tara Isabella Burton “defends” the heroine of Mansfield Park by declaring her a victim of an unjust system: “Fanny isn’t moral or upright because she wants to be, but because the role—along with a whole host of so-called middle-class values—is forced upon her. For all we know, she may well wish to be as carefree, as filled with dynamic sprezzatura, as [Emma] Woodhouse or Elizabeth Bennet, Austen’s more fortunate heroines….”

With a “defense” like that, who needs enemies? I would happily praise Fanny Price on grounds familiar to those of us who really understand, but I’d be preaching to the converted. We lovers of Fanny Price don’t need it. We already know we love her, we know why we love her, and we share contempt for those too stupid to understand.

Instead, I here take on a more difficult task: defending Mrs. Norris. A quick Google search reveals a paucity of champions for Mrs. Norris, who is perhaps the most hated of any of Austen’s characters. (Hated, but enjoyed from the novel’s first publication as Austen’s notes on her friends’ and family’s responses make clear.) In a novel with unclear heroes and heroines, Mrs. Norris is—or would seem to be—an unambiguous villain. She is mean-spirited, self-serving, erroneous, obsequious: fully hideous.

“I was just going to say the very same thing,” said Mrs. Norris. “If every play is to be objected to, you will act nothing—and the preparations will be all so much money thrown away—and I am sure that would be a discredit to us all. I do not know the play; but, as Maria says, if there is any thing a little too warm (and it is so with most of them) it can be easily left out.—We must not be over precise Edmund. As Mr. Rushworth is to act too, there can be no harm.—I only wish Tom had known his own mind when the carpenters began, for there was the loss of a half a day’s work about those side-doors.—The curtain will be a good job, however. The maids do their work very well, and I think we shall be able to send back some dozens of the rings.—There is no occasion to put them so very close together. I am of some use I hope in preventing waste and making the most of things. There should always be one steady head to superintend so many young ones. I forgot to tell Tom of something that happened to me this very day.—I had been looking about me in the poultry yard, and was just coming out, when who should I see but Dick Jackson making up to the servants’ hall door with two bits of deal board in his hand, bringing them to father, you may be sure; mother had chanced to send him of a message to father, and then father had bid him bring up them two bits of board, for he could not no how do without them. I knew what all this meant, for the servants’ dinner bell was ringing at the very moment over our heads, and as I hate such encroaching people, (the Jacksons are very encroaching, I have always said so,—just the sort of people to get all they can.) I said to the boy directly—(a great lubberly fellow of ten years old you know, who ought to be ashamed of himself,) I’ll take the boards to your father Dick; so get you home again as fast as you can.—The boy looked very silly and turned away without offering a word, for I believe I might speak up pretty sharp; and I dare say it will cure him of coming marauding around the house for one while,—I hate such greediness—so good as your father is to the family, employing the man all year round!”

“I was just going to say the very same thing,” said Mrs. Norris. “If every play is to be objected to, you will act nothing—and the preparations will be all so much money thrown away—and I am sure that would be a discredit to us all. I do not know the play; but, as Maria says, if there is any thing a little too warm (and it is so with most of them) it can be easily left out.—We must not be over precise Edmund. As Mr. Rushworth is to act too, there can be no harm.—I only wish Tom had known his own mind when the carpenters began, for there was the loss of a half a day’s work about those side-doors.—The curtain will be a good job, however. The maids do their work very well, and I think we shall be able to send back some dozens of the rings.—There is no occasion to put them so very close together. I am of some use I hope in preventing waste and making the most of things. There should always be one steady head to superintend so many young ones. I forgot to tell Tom of something that happened to me this very day.—I had been looking about me in the poultry yard, and was just coming out, when who should I see but Dick Jackson making up to the servants’ hall door with two bits of deal board in his hand, bringing them to father, you may be sure; mother had chanced to send him of a message to father, and then father had bid him bring up them two bits of board, for he could not no how do without them. I knew what all this meant, for the servants’ dinner bell was ringing at the very moment over our heads, and as I hate such encroaching people, (the Jacksons are very encroaching, I have always said so,—just the sort of people to get all they can.) I said to the boy directly—(a great lubberly fellow of ten years old you know, who ought to be ashamed of himself,) I’ll take the boards to your father Dick; so get you home again as fast as you can.—The boy looked very silly and turned away without offering a word, for I believe I might speak up pretty sharp; and I dare say it will cure him of coming marauding around the house for one while,—I hate such greediness—so good as your father is to the family, employing the man all year round!”

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 15 (New York: Norton, 1998)

This passage exemplifies a number of Mrs. Norris’s traits, most notably her self-identified frugality, the small-mindedness of which interferes with her professed identification with the family’s real interest. Calling a halt to the theatrical proceedings would result in “so much money thrown away.” She moves from a self-aggrandizing declaration that she would be the “steady hand to superintend so many young ones” to exemplifying that steadiness with a hypocritical anecdote about a local family whose greediness and encroaching nature must be stopped by the selfless hard work of Mrs. Norris herself, whose “triumph” over the ten-year-old Dick Jackson was important enough to her for her to relate it again over dinner. (Contrast this to the “triumph” over Mrs. Norris that Fanny avoids projecting when Sir Thomas orders her a carriage to take her to dinner at the Grants’ over Mrs. Norris’s objections).

Was Mrs. Norris born bad? Made bad by circumstances? Taking morality out of our assessment (something required by the critics who profess to disdain Fanny Price) what can we say in favor of Mrs. Norris?

Mrs. Norris and Fanny Price

We learn in the first paragraph of the novel that Mrs. Norris was the older sister of Lady Bertram and, subject to the marriage market of her time, had to watch her younger sister marry first (and marry well) and eventually find “herself obliged to be attached to the Rev. Mr. Norris, a friend of her brother-in-law.” The double passive of “found herself obliged” and “to be attached” signals the novel’s latent sympathy with the character. Mrs. Norris is characterized both explicitly and in the action of the novel as having a “spirit of activity.” Therefore, being put in the position of being acted upon in the single most important life moment that society imposed on young women of her social class—marriage—is not a punishment of her but the signal moment shaping the narrative of Mrs. Norris’s life. Mrs. Norris is female activity repressed by patriarchal society.

There would have been plenty of work to do for the active spouse of a clergyman in the Church of England, the most important of which, perhaps, would have been raising children. Mrs. Norris is dealt another blow by life:

Having married on a narrower income than she had been used to look forward to, she had, from the first, fancied a very strict line of economy necessary; and what was begun as a matter of prudence, soon grew into a matter of choice, as an object of that needful solicitude, which there were no children to supply. Had there been a family to provide for, Mrs. Norris might never have saved her money; but having no care of that kind, there was nothing to impede her frugality…. (Chapter 1)

So when we get to Mrs. Norris’s ill-judged encouragement of Lovers’ Vows we have been prepared to understand that she has clawed her way to significance through assuming a role in the economy of Mansfield Park. Mrs. Norris is a middle manager, a factory floor shift supervisor despised by both the owner (Sir Thomas) and the workers (Dick Jackson and his family). But in the chaos of the household absent Sir Thomas, she is doing the best she can. Like many middle managers (I am one myself) she can only act on her best understanding of the intentions of her superiors in relation to those she is managing—who are, at best, resentful, and at worse filled with enmity and contempt.

Mrs. Norris, like Tara Isabella Burton’s Fanny Price, is a victim of an unjust society: widowed, ill-educated, and requiring patronage to maintain her human dignity. If we would prefer that she be Miss Bates, powerless and ridiculed, existing solely on the basis of charity, what does that say about us? Mrs. Norris, given her limited opportunities, is as hard-working as any of Austen’s female characters.

Anyway, we can’t enjoy Mansfield Park without Mrs. Norris, as the earliest readers of the novel recognized. The distinguished literary critic and essayist Paul Fussell once told me that he’d “rather see people in fistfights than holding hands: it’s boring.” Mrs. Norris, may she rest in peace, provides us with the best fistfights of Mansfield Park, defending the indefensible, attacking the just, interfering when interference was least required—and, ultimately, left behind when both her superiors and her inferiors move along to the rest of their lives. Like a retired boxer with nothing left to do, poor Mrs. Norris is condemned by the novel that needs her to close confinement with her surrogate daughter Maria Rushworth. Used, tossed away. Don’t we all deserve better?

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park. Coming soon: guest posts by Lynn Festa, David Monaghan, Diana Birchall, and Deborah Barnum. Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party!

July 28, 2014

The Trouble with Flirting – a review

In her YA novel The Trouble with Flirting, Claire LaZebnik draws on Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park for inspiration for both characters and plot, while making plenty of changes to keep her readers guessing what happens next. Her Franny Pearson gets to go to the Mansfield Theater Program in Portland, Oregon in the summer of her junior year in high school, except that instead of studying in the program, she has a job working for her aunt, sewing costumes for performances of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Twelfth Night, and Measure for Measure. Franny, like Austen’s Fanny Price, seems destined to be always in the wings, never on stage, and when the “super cute” Harry Cartwright appears on the scene, it seems obvious that, like Henry Crawford, he believes women will always find him irresistible.

In her YA novel The Trouble with Flirting, Claire LaZebnik draws on Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park for inspiration for both characters and plot, while making plenty of changes to keep her readers guessing what happens next. Her Franny Pearson gets to go to the Mansfield Theater Program in Portland, Oregon in the summer of her junior year in high school, except that instead of studying in the program, she has a job working for her aunt, sewing costumes for performances of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Twelfth Night, and Measure for Measure. Franny, like Austen’s Fanny Price, seems destined to be always in the wings, never on stage, and when the “super cute” Harry Cartwright appears on the scene, it seems obvious that, like Henry Crawford, he believes women will always find him irresistible.

Harry does try to defend himself when Julia Braverman tells him he assumes he’s irresistible, asking the girl next to him, “Marie, help me out here. Do I act like I expect all the girls are going to fall at my feet?” Julia and Marie, of course, both fall for Harry, just as Julia and Maria Bertram both fall for Henry Crawford’s charms. Franny admires Harry’s “gray-green eyes and thick dark blond hair,” and his imperfect but still very attractive features, but she’s also cynical about him from the very beginning: “Harry is lounging over by the drinks dispenser, and I do mean lounging: he’s kind of leaning his hip on the counter as he’s filling his cup, like he’s too cool to stand upright. I bet he practices that pose in his room at night.”

Franny has her heart set instead on Alex Braverman, the Edmund Bertram-like character, someone she had a crush on in eighth grade. Even his name suggests he’s the better man. Unlike Harry, Alex seems like the nice guy, the thoughtful one, the one who buys Franny books as a present, even when he’s dating Harry’s best friend Isabella. Harry doesn’t buy books – he buys Franny a cupcake. Franny doesn’t let go of her first impressions of him, but she does begin to acknowledge “he’s funnier and smarter than I’ve given him credit for.” Still, she concludes, “I guess guys like Harry can be good company so long as you don’t forget that they’re, you know … guys like Harry.”

Claire LaZebnik’s take on Mansfield Park is very funny and very smart, both familiar and surprising. Austen’s Mr. Rushworth makes an appearance, as the socially awkward but very rich James Rushport, owner of a silver Porsche convertible; Franny’s Aunt Amelia, like Austen’s Mrs. Norris, seems to derive pleasure from making her niece work hard; and the whole group goes on an expedition to the beach that resembles the Sotherton expedition in Mansfield Park. It’s a pleasure to recognize elements from Austen’s novel, and it’s entertaining to watch as LaZebnik remakes the characters and plot for her own purposes.

Not every author can pull this off in a way that simultaneously honors the original novel and delights the reader with new twists. Claire LaZebnik is that rare exception, and The Trouble with Flirting is an excellent homage to Mansfield Park – a delight for Austen readers, and for readers who have yet to discover any of Austen’s novels. I’ll resist the temptation to tell you many more details about the complexities of LaZebnik’s indebtedness to Austen, but I will say that her Franny Pearson desperately wants to study acting, and in that desire she could not be more different from Fanny Price….

I’m very happy to have discovered The Trouble with Flirting in the year of Mansfield Park’s 200th anniversary and I can’t wait to read Claire LaZebnik’s novel Epic Fail (inspired by Pride and Prejudice) and her newest book, The Last Best Kiss (inspired by Persuasion).

July 25, 2014

Is Edmund Bertram right about anything?

Twelfth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

I lived in Edmonton near the University of Alberta in the 1970s, but I was too young to attend the conference Juliet McMaster organized at the university to mark the 200th anniversary of Jane Austen’s birth. Fortunately, Juliet edited a collection of the papers presented at the conference, Jane Austen’s Achievement, and thus when I grew up I was able to read this wonderful book. If you’ve been following my blog for a while, you already know that I think very highly of the paper George Whalley presented, “Jane Austen: Poet,” which inspired me to explore the idea that Mansfield Park is a tragedy. (He suggests it’s a tragedy, but doesn’t follow up on the idea, so I wrote “The Tragic Action of Mansfield Park” as my attempt to show why it makes sense to think of this “problem novel” as a tragedy, rather than as a failed comedy.)

I lived in Edmonton near the University of Alberta in the 1970s, but I was too young to attend the conference Juliet McMaster organized at the university to mark the 200th anniversary of Jane Austen’s birth. Fortunately, Juliet edited a collection of the papers presented at the conference, Jane Austen’s Achievement, and thus when I grew up I was able to read this wonderful book. If you’ve been following my blog for a while, you already know that I think very highly of the paper George Whalley presented, “Jane Austen: Poet,” which inspired me to explore the idea that Mansfield Park is a tragedy. (He suggests it’s a tragedy, but doesn’t follow up on the idea, so I wrote “The Tragic Action of Mansfield Park” as my attempt to show why it makes sense to think of this “problem novel” as a tragedy, rather than as a failed comedy.)

Fortunately, too, I’ve been able to read and reread Juliet’s many books and essays on Jane Austen over the years (including, a couple of weeks ago, her excellent essay “Sex and the Senses” in Persuasions 34), to hear her present at many other conferences, and to benefit from her advice about my dissertation on Austen and the classical and theological virtues (she was the external examiner for my Ph.D.). I was delighted that she accepted the invitation to contribute a guest post for this series celebrating Mansfield Park.

Juliet is Distinguished Professor Emerita at the University of Alberta, and a frequent speaker at JASNA occasions. Author of books on Thackeray, Trollope, and Dickens, and of Jane Austen on Love and Jane Austen the Novelist, she is also the co-editor of The Cambridge Companion to Jane Austen and illustrator-editor of Austen’s The Beautifull Cassandra. I adore The Beautifull Cassandra, and Juliet’s edition, with its playful illustrations and helpful introduction to Jane Austen’s life and works, is at the top of my list of Jane Austen books for kids. I often give copies of this book and the Cozy Classics Pride and Prejudice to the young people in my life.

Juliet is Distinguished Professor Emerita at the University of Alberta, and a frequent speaker at JASNA occasions. Author of books on Thackeray, Trollope, and Dickens, and of Jane Austen on Love and Jane Austen the Novelist, she is also the co-editor of The Cambridge Companion to Jane Austen and illustrator-editor of Austen’s The Beautifull Cassandra. I adore The Beautifull Cassandra, and Juliet’s edition, with its playful illustrations and helpful introduction to Jane Austen’s life and works, is at the top of my list of Jane Austen books for kids. I often give copies of this book and the Cozy Classics Pride and Prejudice to the young people in my life.

Juliet is giving a talk on “Female Difficulties: Austen’s Fanny and Burney’s Juliet” at the JASNA AGM in Montreal this fall, and I hear she will also be performing in “A Dangerous Intimacy,” the play by Diana Birchall and Syrie James that was commissioned for the AGM.

Fanny was the only one of the party who found any thing to dislike [in the return of Henry Crawford after only two weeks away]; but since the day at Sotherton, she could never see Mr. Crawford with either sister without observation, and seldom without wonder or censure; and had her confidence in her own judgment been equal to her exercise of it in every other respect, had she been sure that she was seeing clearly, and judging candidly, she would probably have made some important communications to her usual confidant. As it was, however, she only hazarded a hint, and the hint was lost. “I am rather surprised,” said she, “that Mr. Crawford should come back again so soon, after being here so long before, full seven weeks; for I had understood he was so very fond of change and moving about, that I thought something would certainly occur when he was gone, to take him elsewhere. He is used to much gayer places than Mansfield.”

“It is to his credit,” was Edmund’s answer, “and I dare say it gives his sister pleasure. She does not like his unsettled habits.”

“What a favourite he is with my cousins!”

“Yes, his manners to women are such as must please. Mrs. Grant, I believe, suspects him of a preference for Julia; I have never seen much symptom of it, but I wish it may be so. He has no faults but what a serious attachment would remove.”

“If Miss Bertram were not engaged,” said Fanny, cautiously, “I could sometimes almost think that he admired her more than Julia.”

“Which is, perhaps, more in favour of his liking Julia best, than you, Fanny, may be aware: for I believe it often happens, that a man, before he has quite made up his own mind, will distinguish the sister or intimate friend of the woman he is really thinking of, more than the woman herself. Crawford has too much sense to stay here if he found himself in any danger from Maria; and I am not at all afraid for her, after such proof as she has given, that her feelings are not strong.”

Fanny supposed she must have been mistaken, and meant to think differently in future; but with all that submission to Edmund could do, and all the help of the coinciding looks and hints which she occasionally noticed in some of the others and which seemed to say that Julia was Mr. Crawford’s choice, she knew not always what to think.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 12 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988)

This brief exchange between Edmund and Fanny occurs after Henry Crawford has returned to Mansfield after only two weeks’ absence at his own estate of Everingham. And it is interesting in showing how Fanny, the pupil, with strong powers of observation and judgement, is desperately short of confidence in her own judgement; whereas Edmund, the tutor – (and their relation has been very much that of pupil and teacher) has full confidence in his own judgement, but with much less reason.

Fanny has had the benefit of observing Henry’s flirtatious behaviour with Julia and especially Maria during the trip to Sotherton. Edmund was there too, but he didn’t see what Fanny observed, and his powers of observation are clearly inferior to hers. He is pretty thoroughly wrong about several things:

Fanny has had the benefit of observing Henry’s flirtatious behaviour with Julia and especially Maria during the trip to Sotherton. Edmund was there too, but he didn’t see what Fanny observed, and his powers of observation are clearly inferior to hers. He is pretty thoroughly wrong about several things:

* For instance, that Henry Crawford “has too much sense to stay here if he found himself in danger from Maria” – Wrong! In fact we know that Henry finds Maria more attractive for her engagement, presumably on the “forbidden fruit” principle.

* He considers Maria quite free of attachment to Crawford, since by engaging herself to Rushworth she has proved “her feelings are not strong.” Wrong! Her feelings are in fact so strong that that despite her engagement to Rushworth (for mercenary reasons, of course) she is ready to upset the whole applecart for Crawford, as eventually she does.

Is Edmund right about anything? His comment that Crawford “has no faults but what a serious attachment will remove” could be right – and Mary Crawford too believes that if he had married Fanny he would have settled down to being a good husband and landlord. That belief is pretty questionable, of course, but it is never tested, and since it is only a might-have-been, the answer must depend on the individual judgements of readers.

Then what about his general comment on human behaviour, that “it often happens that a man, before he has quite made up his own mind, will distinguish the sister or intimate friend of the woman he is really thinking of more than the woman herself”? Wrong again, so far as Julia and Maria are concerned! From this bit of general wisdom he intends to prove that Crawford’s attentions to Maria are really because he prefers Julia – which again is arrant nonsense (as Fanny knows, but daren’t say, because of her disastrous lack of confidence in her own judgment).

But what interests me is the extent to which Edmund’s piece of wisdom may actually apply to himself. I have long believed that Edmund, even while he consciously courts Mary Crawford, is equally in love with Fanny – or indeed even more so. (Note: I argued this in Jane Austen on Love, back in 1978, but I have sometimes been challenged on it.) Certainly Edmund believes himself in love with Mary, and – through his ignorance of Fanny’s feelings – he often puts Fanny through the pain of being his confidante in his courtship of Mary. But there are many signs of his equal love for Fanny. He calls her “Dearest Fanny!” (note the superlative!), and kisses her hand “with almost as much warmth as if it had been Mary Crawford’s” (269). “Almost”? But that is Fanny’s perception more than the narrator’s pronouncement, isn’t it? He tells Fanny fervently, “I have no pleasure in the world superior to that of contributing to yours … no pleasure so complete, so unalloyed” (262).

I should concede the points against me. I have to admit that Edmund’s encouraging Fanny to accept Henry Crawford, as he certainly does, is not very lover-like. After all, the most visible sign that Mr. Knightley is in love with Emma is his jealousy of Frank Churchill. Indeed, it seems he doesn’t wake up to his own love himself until he understands his own jealousy (and the same applies to Emma, who doesn’t know she loves Knightley until she thinks he may marry Harriet). But then Mr. Knightley is certainly more knowledgeable about himself and his feelings than Edmund is about his. Edmund thinks he is in love with Mary, says he could never marry anyone else. But then why doesn’t he get on and propose to her? Should he propose in person, he wonders, or in a letter? (422). He is forever dithering. Even Fanny gets impatient at his prolonged shilly-shallying, and exclaims, “There is no good in this delay … Why is it not settled?” (424).

I should concede the points against me. I have to admit that Edmund’s encouraging Fanny to accept Henry Crawford, as he certainly does, is not very lover-like. After all, the most visible sign that Mr. Knightley is in love with Emma is his jealousy of Frank Churchill. Indeed, it seems he doesn’t wake up to his own love himself until he understands his own jealousy (and the same applies to Emma, who doesn’t know she loves Knightley until she thinks he may marry Harriet). But then Mr. Knightley is certainly more knowledgeable about himself and his feelings than Edmund is about his. Edmund thinks he is in love with Mary, says he could never marry anyone else. But then why doesn’t he get on and propose to her? Should he propose in person, he wonders, or in a letter? (422). He is forever dithering. Even Fanny gets impatient at his prolonged shilly-shallying, and exclaims, “There is no good in this delay … Why is it not settled?” (424).

But to return to Edmund and my chosen passage: “A man … will distinguish the sister or intimate friend of the woman he is really thinking of, more than the woman herself.” As a general rule, this is one more place where Edmund is wrong. But as applying to himself – the rule is true and correct. Edmund does distinguish Mary, the intimate friend (as he thinks) of Fanny, more than Fanny herself. But whom does he really mean to marry, even if he doesn’t know it himself? Right! Fanny!

Dare I conclude, Q.E.D.?!

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park. Coming soon: guest posts by Lynn Festa, David Monaghan, Diana Birchall, and Deborah Barnum. Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party!

July 18, 2014

Dr. Grant’s Green Goose

Before I introduce today’s guest post, I want to note that this is the anniversary of Jane Austen’s death. She died in Winchester on July 18, 1817, at the age of 41. Here’s the link to a post I wrote two years ago to commemorate the anniversary of her death: “Never was human being more sincerely mourned.” Deborah Yaffe wrote a lovely blog post yesterday to mark the occasion: “The sun of our lives.”

Before I introduce today’s guest post, I want to note that this is the anniversary of Jane Austen’s death. She died in Winchester on July 18, 1817, at the age of 41. Here’s the link to a post I wrote two years ago to commemorate the anniversary of her death: “Never was human being more sincerely mourned.” Deborah Yaffe wrote a lovely blog post yesterday to mark the occasion: “The sun of our lives.”

This guest post is the eleventh in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Today’s contributor to “An Invitation to Mansfield Park” is Dr. Julie Strong, a member of JASNA Nova Scotia who has practised medicine in Nova Scotia for thirty years. She has an MD from Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland and a BA in Classics from Dalhousie University. Julie has had several articles appear in medical publications. Her queer tragic-comedy “Athena in Love” won the Best Playwright’s Award in the 2012 Atlantic Fringe Festival. She has presented in the United States and Europe on “Madness in Ancient Greece” and “The Shamanic Roots of Western Medicine.”

In Chapter 11, Mary Crawford visits Edmund Bertram and Fanny Price at Mansfield Park. Mary has become increasingly attached to Edmund, and, much to Fanny’s consternation, he has become increasingly attached to her. However, Mary wishes to marry a man of ambition and, dismayed at Edmund’s intention to take holy orders, hopes to dissuade him by describing the petty veniality of a clergyman’s life.

“I have been so little addicted to take my own opinions from my uncle,” said Miss Crawford, “that I can hardly suppose; – and since you push me so hard, I must observe, that I am not entirely without the means of seeing what clergymen are, being at this time the guest of my own brother, Dr Grant. And though Dr Grant is most kind and obliging to me, and though he is really a gentleman, and I dare say a good scholar and clever, and often preaches good sermons, and is very respectable, I see him to be an indolent, selfish bon vivant, who must have his palate consulted in every thing, who will not stir a finger for the convenience of any one, and who, moreover, if the cook makes a blunder, is out of humour with his excellent wife. To own the truth, Henry and I were partly driven out this very evening, by a disappointment about a green goose which he could not get the better of. My poor sister was forced to stay and bear it.”

“I have been so little addicted to take my own opinions from my uncle,” said Miss Crawford, “that I can hardly suppose; – and since you push me so hard, I must observe, that I am not entirely without the means of seeing what clergymen are, being at this time the guest of my own brother, Dr Grant. And though Dr Grant is most kind and obliging to me, and though he is really a gentleman, and I dare say a good scholar and clever, and often preaches good sermons, and is very respectable, I see him to be an indolent, selfish bon vivant, who must have his palate consulted in every thing, who will not stir a finger for the convenience of any one, and who, moreover, if the cook makes a blunder, is out of humour with his excellent wife. To own the truth, Henry and I were partly driven out this very evening, by a disappointment about a green goose which he could not get the better of. My poor sister was forced to stay and bear it.”

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 11 (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003)

Jane Stabler, editor of the Oxford World’s Classics edition of the novel, explains that “a green goose” is one “killed at three or four months old, as opposed to one fattened on stubble for eating at Michaelmas. Green goose was traditionally eaten around Whitsuntide, which may explain why Dr. Grant finds it less than satisfactory in late summer. It also indicates that for him the observance of the calendar of church festivals is less important than the possibility of a gourmet treat.”

Edmund agrees with Mary that Dr. Grant should not indulge in bad humour merely for being denied a succulent roast; however, he insists that it is insufficient cause for condemning the entire profession.

Fanny suggests that it is just as well Dr. Grant became a clergyman. She reasons that an army or navy position would only have increased his power to injure his inferiors. This would be Austen’s fine sense of irony at play: a profession whose manifest aim is the elevation of the human soul is reduced to a means of defanging an unpleasant man.

Nevertheless, there is a brief episode in Chapter 22 in which Dr. Grant rouses himself. He takes an umbrella to Fanny who is sheltering from a downpour under a tree just near the parsonage grounds. She has already refused a servant with an umbrella, but unable to withstand Dr. Grant, accompanies him back to the parsonage where she changes into dry clothes. The rector thus saves our heroine from a good chance of contracting consumption, albeit against her will.

Nevertheless, there is a brief episode in Chapter 22 in which Dr. Grant rouses himself. He takes an umbrella to Fanny who is sheltering from a downpour under a tree just near the parsonage grounds. She has already refused a servant with an umbrella, but unable to withstand Dr. Grant, accompanies him back to the parsonage where she changes into dry clothes. The rector thus saves our heroine from a good chance of contracting consumption, albeit against her will.

However, this lapse into civility passes and Dr. Grant soon returns to form. Edmund and Fanny are visiting the Grants and Dr. Grant invites Edmund, alone, to dinner the following day. It no more occurs to him to include Fanny than to include his housemaid. However, “Fanny had barely time for an unpleasant feeling on the occasion,” because Mrs. Grant quickly invites her, and so mitigates her husband’s rudeness. When Mrs. Grant informs him that it will be a fine turkey for dinner, he feigns lack of interest or even annoyance: “A friendly meeting and not a fine dinner is all we have in view. A Goose or a leg of mutton or whatever you and cook chuse to give us.” He affects that indifference to matters of the flesh becoming to a clergyman and so adds hypocrisy to his existing list of vices.

Dr. Grant is a grouchy gourmand whom Austen summarily dispatches at the close of the novel. He dies, having “brought on apoplexy and death, by three great institutionary dinners in one week” (Chapter 48). As Cheryl Kinney discussed in her post for “An Invitation to Mansfield Park,” Tom Bertram was right that Dr. Grant would “soon pop off.” The living of Mansfield then falls to Edmund, when he and Fanny “had been married just long enough to begin to feel a want an increase of income.” And so Dr. Grant redeems, through death, some part of his life of vice, by contributing to the happiness of the novel’s hero and heroine.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park. Coming soon: guest posts by Juliet McMaster, Lynn Festa, David Monaghan, and Diana Birchall. Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party!

July 11, 2014

The Fatal Mistake

Tenth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Deborah Yaffe, an award-winning newspaper journalist and author, has been a passionate Jane Austen fan since first reading Pride and Prejudice at age ten. Her second book, Among the Janeites: A Journey Through the World of Jane Austen Fandom, was published in August 2013. I was fascinated by the book and reviewed it here last fall, and then in January I interviewed Deborah about the series of blog posts she wrote on continuations of Austen’s unfinished novel The Watsons.

Deborah Yaffe, an award-winning newspaper journalist and author, has been a passionate Jane Austen fan since first reading Pride and Prejudice at age ten. Her second book, Among the Janeites: A Journey Through the World of Jane Austen Fandom, was published in August 2013. I was fascinated by the book and reviewed it here last fall, and then in January I interviewed Deborah about the series of blog posts she wrote on continuations of Austen’s unfinished novel The Watsons.

Deborah holds a bachelor’s degree in humanities from Yale University and a master’s degree in politics, philosophy, and economics from Oxford University in England, which she attended on a Marshall Scholarship. She works as a freelance writer and lives in central New Jersey with her husband, her two children, and her Jane Austen action figure. I hope you enjoy reading her post on the well-known scene at Sotherton in which Maria Bertram and Henry Crawford slip past the locked iron gate.

[Henry to Maria:] “Your prospects, however, are too fair to justify want of spirits. You have a very smiling scene before you.”

“Do you mean literally or figuratively? Literally I conclude. Yes, certainly, the sun shines and the park looks very cheerful. But unluckily that iron gate, that ha-ha, gives me a feeling of restraint and hardship. ‘I cannot get out,’ as the starling said.” As she spoke, and it was with expression, she walked to the gate; he followed her. “Mr. Rushworth is so long fetching this key!”

“Do you mean literally or figuratively? Literally I conclude. Yes, certainly, the sun shines and the park looks very cheerful. But unluckily that iron gate, that ha-ha, gives me a feeling of restraint and hardship. ‘I cannot get out,’ as the starling said.” As she spoke, and it was with expression, she walked to the gate; he followed her. “Mr. Rushworth is so long fetching this key!”

“And for the world you would not get out without the key and without Mr. Rushworth’s authority and protection, or I think you might with little difficulty pass round the edge of the gate, here, with my assistance; I think it might be done, if you really wished to be more at large, and could allow yourself to think it not prohibited.”

“Prohibited! nonsense! I certainly can get out that way, and I will. Mr. Rushworth will be here in a moment, you know; we shall not be out of sight.”

“Or if we are, Miss Price will be so good as to tell him that he will find us near that knoll: the grove of oak on the knoll.”

Fanny, feeling all this to be wrong, could not help making an effort to prevent it. “You will hurt yourself, Miss Bertram,” she cried, “you will certainly hurt yourself against those spikes – you will tear your gown – you will be in danger of slipping into the ha-ha. You had better not go.”

Her cousin was safe on the other side, while these words were spoken, and smiling with all the good-humour of success, she said, “Thank you, my dear Fanny, but I and my gown are alive and well, and so good-bye.”

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 10 (London: Penguin, 1985)

In every Jane Austen novel, a young woman successfully navigates the perilous journey from the home of her parents to the home of a loving and responsible husband. We know this journey is perilous because, in every Austen novel, this ultimately happy story has its shadowy, minor-key counterpart: the story of a young woman who makes a terrible mistake about men, marriage and sex, and pays the price.

Sometimes this counter-story exists largely in the heroine’s fantasies, like Mrs. Tilney’s Gothic imprisonment in Northanger Abbey or Jane Fairfax’s guilty love for Mr. Dixon in Emma. Sometimes it is real but wholly offstage, like the tragedy of the two Elizas in Sense and Sensibility or the unlucky marriage of Mrs. Smith in Persuasion. And sometimes it remains largely offstage but still plays an important role in the plot, like Wickham’s seduction of Lydia in Pride and Prejudice.

Sometimes this counter-story exists largely in the heroine’s fantasies, like Mrs. Tilney’s Gothic imprisonment in Northanger Abbey or Jane Fairfax’s guilty love for Mr. Dixon in Emma. Sometimes it is real but wholly offstage, like the tragedy of the two Elizas in Sense and Sensibility or the unlucky marriage of Mrs. Smith in Persuasion. And sometimes it remains largely offstage but still plays an important role in the plot, like Wickham’s seduction of Lydia in Pride and Prejudice.

Only in Mansfield Park does Jane Austen allow us to watch the counter-story – the seduction, the fatal mistake, the fall – unfolding in real time. And the scene from Chapter 10 quoted above, in which Henry Crawford persuades Maria Bertram to slip past the locked gate at Sotherton, is the epicenter of the counter-story, the emblematic moment that contains and anticipates the whole.

As Henry, snake-like, tempts Maria into leaving her fiancé behind and accompanying him out of the Edenic wilderness, we know that this literal transgression of geographic boundaries foreshadows the transgression of social boundaries they will soon commit together. We know that Fanny’s alarmed warning – “You will certainly hurt yourself against those spikes; you will tear your gown; you will be in danger of slipping into the ha–ha” – is a coded reference to the illicit sexual penetration, and the accompanying social calamity, that will eventually occur.

And yet nothing really illicit happens here. We don’t overhear an explicit sexual proposition, witness a stolen kiss, or even notice a semi-accidental brushing of fingertips. All we see is a man and a woman slipping past an iron gate.

How, then, do we know that the stakes are so high? How do we know that Maria’s unwillingness to wait for Rushworth to bring her the key to the gate prefigures her unwillingness to remain faithful to him within the fenced wilderness of marriage?

Partly, of course, we know all this because we are post-Freudian readers, primed to see keys and spikes and tears as sexual codes. How, then, do we know that the pre-Freudian Jane Austen had this metaphorical reading in mind?