Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 37

January 17, 2014

Mansfield Park is a Tragedy, Not a Comedy

I’m really excited about discussing Mansfield Park with all of you this year – so excited that I can’t wait until May 9th, when my series of guest posts on the novel launches, to start the conversation. I’m also far too impatient to begin at the beginning, so I’m writing today to tell you what I think of the ending. For anyone who hasn’t yet read Mansfield Park, here’s the obligatory spoiler alert. (Although I guess the title of this post already alluded to the ending….)

I think the key to understanding Mansfield Park is that it’s a tragedy, rather than a comedy. I mentioned a couple of weeks ago that not many people choose it as a favourite from among Austen’s novels. (Natasha Duquette, who’s writing a guest post on part of Chapter 27 – in which Fanny “had all the heroism of principle” – is an exception. Is there anyone else out there whose favourite Austen novel is Mansfield Park? I would love to hear from you! I’ve already confessed that Pride and Prejudice is my own favourite, although MP is a close second.) Many readers find the ending of Mansfield Park disappointing. I think that’s because most of us tend to approach Austen novels with the expectation that they will be romantic comedies. And most of them are. But not this one.

Reading Mansfield Park in light of Aristotle’s theory of tragedy in his Poetics shows that it’s a tragedy with a happy ending, or a “prosperous outcome.” I wrote about this idea in my essay “The Tragic Action of Mansfield Park” in Persuasions On-Line a few years ago.

Aristotle’s Poetics, translated by George Whalley, edited by John Baxter and Patrick Atherton

The essay was based on a talk I gave at the 2006 JASNA AGM in Tucson, and over the last few years I revised it again, developing the argument further for publication in the MLA collection of essays Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Mansfield Park, edited by Marcia McClintock Folsom and John Wiltshire. That version of the essay will be published soon (the book is at the copyediting stage, so publication can’t be too far away – I hope!).

But for now, if you’re interested in my argument, you can read the earlier version in Persuasions On-Line. This version includes comparisons between Mansfield Park and Edith Wharton’s novel The House of Mirth, and I was quite attached to those comparisons (as you can imagine, because I love talking about Austen and Wharton). I expanded the rest of the essay for the MLA volume, but I had to take Wharton out because of the focus on teaching Austen.

So here’s your chance to read the Austen and Wharton version:

The House of Mirth, by Edith Wharton, edited by Janet Beer and Elizabeth Nolan

In October 1906, a dramatization of Edith Wharton’s novel The House of Mirth opened in New York at the Savoy Theater. It was not a success, even though the novel had been very well-received the year before. The ending of The House of Mirth is melancholy: the beautiful heroine dies alone in a dreary New York boarding house, either by suicide or an accidental overdose of chloral, after a painful decline in her social and financial position and her marriage prospects. Like Fanny Price or Elizabeth Bennet, she has refused to marry a man she cannot love; unlike Elinor Dashwood, who marries Edward Ferrars on a small clerical income, Wharton’s heroine does not think she could ever be comfortable married to the man she does love, because he does not have enough money to support the life of luxury she craves. Edith Wharton later reflected on the judgment of her friend William Dean Howells, who, she said, commented to her after the performance that “[w]hat the American public always wants is a tragedy with a happy ending.”

Click here to read the rest of the essay in Persuasions On-Line.

January 8, 2014

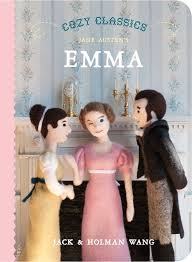

The Cozy Classics Emma – a review

The Cozy Classics board book adaptations of Jane Austen’s novels are handsome and clever (and reasonably priced, too). The new Emma is just as charming as the Cozy Classics Pride and Prejudice (here’s the link to my review of that book), with twelve key words chosen to highlight important moments from the plot, and beautiful felted figures photographed in appropriate settings, often in the natural world.

The Cozy Classics board book adaptations of Jane Austen’s novels are handsome and clever (and reasonably priced, too). The new Emma is just as charming as the Cozy Classics Pride and Prejudice (here’s the link to my review of that book), with twelve key words chosen to highlight important moments from the plot, and beautiful felted figures photographed in appropriate settings, often in the natural world.

The faces of these felted dolls, handmade by brothers Jack and Holman Wang, are simple but expressive. Emma winks at the reader when she introduces Harriet Smith to Mr. Elton (“hello”), and again when Harriet thanks Frank Churchill for rescuing her (“thanks”). She raises her eyebrows when Mr. Elton proposes (“surprise!”), and sets her mouth in a line when she takes Harriet’s hand to pull her away from Robert Martin. And poor Robert Martin! He tilts his head and furrows his brow when Harriet says “goodbye” (or rather, when Emma says goodbye for her).

Poor Miss Bates, too. She clasps her hands and looks down, frowning, when Emma and Frank Churchill laugh and point at her at the Box Hill picnic. She has a furrowed brow that’s even more anxious than Mr. Martin’s. Mr. Knightley frowns and raises his hands when he asks Emma “why?” she has separated Harriet from Robert Martin, but he is positively fierce (okay, as fierce as a small felted doll can be) when he confronts Emma after she makes her infamous joke at Miss Bates’s expense (“angry”). In the earlier confrontation, we see his angry face in profile, and Emma looks away from him, arms crossed. In the Box Hill scene, he faces the reader and Emma with his glare and his frown. “Badly done, indeed!” Emma’s back is to us, and this time her hands appear to be clasped in front of her. The slight angle at which she tilts her head makes it clear she’s not meeting Mr. Knightley’s eyes. It’s astonishing just how much emotion is packed into this tiny book.

why?

Writers sometimes say that composing sentences in 140 characters to post on Twitter is a good way to learn how to be concise. Before I discovered the Cozy Classics books, I would never have imagined that condensing a Jane Austen novel into twelve words could be a useful exercise. I’m often disappointed when two-hour film adaptations leave out crucial scenes from the novels, so it’s surprising to find that a board book adaptation can be so effective at conveying the highlights of an Austen novel. Obviously, there are all kinds of important people, things, and scenes missing from this board book: Mr. Woodhouse, Jane Fairfax, gruel, the piano, and the ball at the Crown, for example. But the Wang brothers’ choice of words tells children a great deal about the story, even if they read on their own, without an adult to fill in more details and names.

I missed the details of Austen’s novel most at the end. The story moves quickly from Mr. Knightley being “angry” to Emma being “sorry” to the two of them being “happy” on the last page. (Harriet and Robert Martin are in the background, happily reunited.) It just isn’t that simple. When Jane Austen shows how Emma responds to Mr. Knightley’s rebuke, we learn about her examining her conscience and discovering that in her attitude toward Miss Bates, “She had been often remiss … ; remiss, perhaps, more in thought than fact; scornful, ungracious.” She judges herself more harshly than Mr. Knightley does, and I’ve long been fascinated by the way she reflects on her mistakes. There’s no doubt that she learns from Mr. Knightley, but she doesn’t learn only from him, and simplifying the plot of Emma will nearly always suggest that his judgement is her rule of right (to paraphrase Henry Crawford’s words to Fanny Price in Mansfield Park). Emma eventually learns to attend to the “better guide” in herself (to paraphrase Fanny’s reply to Henry).

There is of course no substitute for the complexities of an Austen novel. But for very young readers, the Cozy Classics Emma is an excellent place to begin learning about the emotional world of some of Austen’s most memorable characters.

Read more about Jane Austen for Kids here.

January 1, 2014

200 Years of Mansfield Park!

“About thirty years ago, Miss Maria Ward of Huntingdon, with only seven thousand pounds, had the good luck to captivate Sir Thomas Bertram, of Mansfield Park, in the county of Northamptonshire, and to be thereby raised to the rank of a baronet’s lady, with all the comforts and consequences of an handsome house and large income.”

The first sentence of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park is nowhere near as famous as the first line of Pride and Prejudice. The heroine of Mansfield Park is nowhere near as beloved as Elizabeth Bennet. The novel is rarely chosen as anyone’s favourite Austen novel – I recently heard it described (by a Janeite who shall remain nameless!) as “my 6th favorite Austen.” But even though it doesn’t have the same kind of sparkle as Pride and Prejudice, it’s a complex, fascinating, brilliant book.

The first sentence of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park is nowhere near as famous as the first line of Pride and Prejudice. The heroine of Mansfield Park is nowhere near as beloved as Elizabeth Bennet. The novel is rarely chosen as anyone’s favourite Austen novel – I recently heard it described (by a Janeite who shall remain nameless!) as “my 6th favorite Austen.” But even though it doesn’t have the same kind of sparkle as Pride and Prejudice, it’s a complex, fascinating, brilliant book.

This year marks the two hundredth anniversary of the publication of Mansfield Park, and I hope you’ll join me in celebrating by reading and discussing the novel here with the wonderful people who’ve agreed to write guest posts on short passages.

The series launches May 9th, on the anniversary of the publication date, with Lyn Bennett’s analysis of the opening paragraph, and it continues through the summer and  fall with posts by many excellent writers. Here are the ones confirmed so far: Elaine Bander, Deborah Barnum, Lorrie Clark, Natasha Duquette, Susan Allen Ford, Margaret Horwitz, Theresa Kenney, Ryder Kessler, Hugh Kindred, Cheryl Kinney, Sara Malton, David Monaghan, Laurel Ann Nattress, Amy Patterson, Mary C. M. Phillips, Maggie Sullivan, Judith Thompson, and Sarah Woodberry. Sheila Johnson Kindred will write about the concluding paragraphs towards the end of the year.

fall with posts by many excellent writers. Here are the ones confirmed so far: Elaine Bander, Deborah Barnum, Lorrie Clark, Natasha Duquette, Susan Allen Ford, Margaret Horwitz, Theresa Kenney, Ryder Kessler, Hugh Kindred, Cheryl Kinney, Sara Malton, David Monaghan, Laurel Ann Nattress, Amy Patterson, Mary C. M. Phillips, Maggie Sullivan, Judith Thompson, and Sarah Woodberry. Sheila Johnson Kindred will write about the concluding paragraphs towards the end of the year.

I can’t wait to read their posts and share them with you as we pay tribute to the third of the four novels Austen published in her lifetime. I love Pride and Prejudice as much as any devoted Janeite, but Mansfield Park is a close second for me. I’m happy to be celebrating with all of you online through the year, and with many of you in person at the JASNA AGM in Montreal in October.

Happy New Year, and Happy 200th Anniversary to Mansfield Park!

December 25, 2013

Christmas Company and Celebrations

I sincerely hope your Christmas … may abound in the gaieties which that season generally brings.

- Pride and Prejudice

Yes, I know I’m quoting Caroline Bingley here, just as the Bank of England quotes her saying, “I declare there is no enjoyment like reading” on the mock up of the new £10 note. (I recommend John Mullan’s analysis of “Why that Jane Austen quotation on the new £10 note is a major blunder” and Janine Barchas’s post “Jane Austen on the Tenner — great idea, bad execution.”) No matter how hard you search the texts of Austen’s novels and letters, it can be a challenge to find quotations that fit special occasions such as holidays and weddings.

My wishes really are sincere, however. I hope you all have a wonderful time over the holidays. May you all enjoy good food (syllabub, perhaps?), good books, and good company – or, if you’re very fortunate (and I hope you are), the best company: “the company of clever, well-informed people, who have a great deal of conversation” (Persuasion). There – that’s a Jane Austen quotation that fits the occasion, and it’s Anne Elliot this time, instead of Miss Bingley.

Merry Christmas, and I’ll see you in the New Year. Let’s celebrate 200 years of Mansfield Park!

December 16, 2013

Happy Birthday to Jane Austen!

Jane Austen was born 238 years ago today, on December 16, 1775. Claire Tomalin imagines what must have been happening at Steventon in the first days after the birth: “Inside the parsonage, Mrs. Austen lay upstairs in the four-poster, warmly bundled under her feather-beds, the baby in her cradle beside her, while someone else—very likely her sister-in-law Philadelphia Hancock—supervised the household, all the cleaning and cooking necessary where there were many small children, together with the extra washing for the newly delivered mother.” She says Mrs. Austen wouldn’t have left her bed for at least two weeks, and wouldn’t have left the house for at least a month. It was a cold, hard winter.

Jane Austen was born 238 years ago today, on December 16, 1775. Claire Tomalin imagines what must have been happening at Steventon in the first days after the birth: “Inside the parsonage, Mrs. Austen lay upstairs in the four-poster, warmly bundled under her feather-beds, the baby in her cradle beside her, while someone else—very likely her sister-in-law Philadelphia Hancock—supervised the household, all the cleaning and cooking necessary where there were many small children, together with the extra washing for the newly delivered mother.” She says Mrs. Austen wouldn’t have left her bed for at least two weeks, and wouldn’t have left the house for at least a month. It was a cold, hard winter.

On December 7th, JASNA Nova Scotia enjoyed a lovely celebration of Austen’s birthday at The Cellar Bar and Grill in Halifax, with a record turnout of seventeen people. Christina told us about tours and talks at the 2013 JASNA AGM in Minneapolis, and Hugh gave an eloquent toast to Jane Austen, quoting a passage from a letter to Cassandra in November 1798 in which she talks, briefly, about her own feelings. Austen’s reflections, he said, “are full of her customary ironic humour, only in this instance it’s directed towards herself.”

The Cellar Bar and Grill

In the letter, she’s writing about Tom Lefroy (the “Irish friend” with whom she had danced and flirted in the past) and she says, “I was too proud to make any enquiries”  about him. “It will all go on exceedingly well, and decline away in a very reasonable manner. There seems no likelihood of his coming into Hampshire this Christmas, and it is therefore most probable that our indifference will soon be mutual, unless his regard, which appeared to spring from knowing nothing of me at first, is best supported by never seeing me.”

about him. “It will all go on exceedingly well, and decline away in a very reasonable manner. There seems no likelihood of his coming into Hampshire this Christmas, and it is therefore most probable that our indifference will soon be mutual, unless his regard, which appeared to spring from knowing nothing of me at first, is best supported by never seeing me.”

Hugh wonders what she thought of Tom Lefroy in his absence. “Was she disappointed or dissembling? Was her existence a life less for a love lost, or a literary life released by a love let go?” What do you think of this passage, dear readers? Does her humour conceal disappointment, or is she ready for “mutual indifference”? Can you think of other passages in the letters where she makes reference to her feelings?

The new issue of Persuasions On-Line is published today, including papers from the AGM in Minneapolis. This year’s celebration of 200 years of Pride and Prejudice continues. Pretty soon, however, it will be the Year of Fanny Price – 200 years since the publication of Mansfield Park – and JASNA members can look forward to the 2014 AGM: “Mansfield Park in Montréal: Contexts, Conventions & Controversies.”

I’m working on an exciting project that will celebrate Mansfield Park here on my blog. As with the 200th anniversary of Pride and Prejudice and the 100th anniversary of The Custom of the Country, I’m planning a series of posts that focus on the novel—but this  time, you’ll get to hear from several different writers talking about Mansfield Park. Please stay tuned for more information about the contributors to this new series!

time, you’ll get to hear from several different writers talking about Mansfield Park. Please stay tuned for more information about the contributors to this new series!

Quotations from the letters are from the fourth edition of Jane Austen’s Letters, ed. Deirdre Le Faye (Oxford University Press, 2011). The passage about Jane Austen’s birth is from Jane Austen: A Life, by Claire Tomalin (Vintage, 1999).

December 15, 2013

Run or walk the Sole Sisters 5K with JASNA Nova Scotia!

Come out and run or walk the Sole Sisters 5K in June with the women of JASNA Nova Scotia! 2014 is the third year for this fun event, organized by the inspiring Stacy Juckett Chesnutt. Leave your watch at home, because no one’s keeping track of times at this race. Sole Sisters celebrates “the strength of female runners and the lifelong friendships developed on and off the running roads.” We hope the men of JASNA NS will consider cheering us on.

Run or walk with your friends, stop for water (and chocolate!) along the way, and support the Sole Sisters charity partners, including Girls Gone Gazelle, a not-for-profit, all-girls running club for pre-teens, whose slogan is “I don’t chase boys, I pass them!”

Please join us Saturday, June 7, 2014 in Dartmouth, NS. Click here to register — and “make haste,” as Mrs. Bennet would say. The event sells out quickly.

“Run mad as often as you chuse; but do not faint.” - Jane Austen, “Love and Freindship”

December 6, 2013

“Tar and blood and needles of glass”

Ninety-six years ago today, at 9:05 a.m., the French cargo and munitions ship Mont Blanc collided with the Norwegian supply ship Imo in the Narrows leading to Halifax Harbour, and the resulting explosion was the largest man-made explosion in the years before nuclear weapons. The North End of Halifax was flattened, and at least 2,000 people were killed while thousands more were injured.

Carol Bruneau writes vividly about the Halifax Explosion and its aftermath in her novel Glass Voices. Her heroine, Lucy Caines, gives birth to her son in a tent at the base of Citadel Hill on the night after the explosion, “the wind yowling like a cat as she’d laboured.” The hill and the tent village are covered in snow, “but that was as far as whiteness went,” because “the sky had rained tar earlier, what, a morning before? A lifetime? Tar and blood and needles of glass. It’d wept chunks of earth and flaming metal.” Immediately after the explosion Lucy finds herself on the smaller hill of Fort Needham, “arse over teakettle, limbs splayed,” “toes facing uphill, hands and feet the points of a compass rose. Blood drummed her ears as a mushroom grew in the sky, a giant, spreading fungus that crowded out the sun. The spiky grass grazed her cheek: an inch from her eye a bedspring, and something else, unspeakable, purple, with suckers trailing from it like a jellyfish’s. A hand?”

Carol Bruneau writes vividly about the Halifax Explosion and its aftermath in her novel Glass Voices. Her heroine, Lucy Caines, gives birth to her son in a tent at the base of Citadel Hill on the night after the explosion, “the wind yowling like a cat as she’d laboured.” The hill and the tent village are covered in snow, “but that was as far as whiteness went,” because “the sky had rained tar earlier, what, a morning before? A lifetime? Tar and blood and needles of glass. It’d wept chunks of earth and flaming metal.” Immediately after the explosion Lucy finds herself on the smaller hill of Fort Needham, “arse over teakettle, limbs splayed,” “toes facing uphill, hands and feet the points of a compass rose. Blood drummed her ears as a mushroom grew in the sky, a giant, spreading fungus that crowded out the sun. The spiky grass grazed her cheek: an inch from her eye a bedspring, and something else, unspeakable, purple, with suckers trailing from it like a jellyfish’s. A hand?”

I reviewed Glass Voices for The Diocesan Times when it was published in 2007. The paper’s online archive only goes back a couple of years, but I reproduced the review on my website in 2010 and you can read it here. You can learn more about the Explosion at this CBC website.

There’s a memorial service at the Halifax Explosion Memorial Bell Tower at Fort Needham Park this morning at 8:45, followed by a reception in United Memorial Church, 5375 Kaye Street.

Halifax Explosion Memorial Bell Tower, Fort Needham Park

November 30, 2013

L.M. Montgomery’s Literary Pilgrimage to Concord, Mass.

Given how many fans of L.M. Montgomery visit “Green Gables” in Cavendish, PEI each year, I find it fascinating to read about Montgomery’s own literary pilgrimage to Concord, Massachusetts, when she was visiting her publisher, L.C. Page in Boston in November of 1910. “Concord is the only place I saw when I was away where I would like to live,” she writes. “It is a most charming spot and I shall never forget the delightful drive we had around it. We saw the ‘Old Manse’ where Hawthorne lived during his honeymoon and where he wrote ‘Mosses from an Old Manse,’ the ‘Wayside’ where he also lived, the ‘Orchard House’ where Louisa Alcott wrote, and Emerson’s house. It gave a strange reality to the books of theirs which I have read to see those places where they once lived and labored.”

Orchard House (thanks to Edie Baxter for the photo)

I wonder how many visitors to “Green Gables” feel that “strange reality” when they tour the house and grounds. Of course, Montgomery herself didn’t “live and labor” in that house, and the nearby house where she wrote Anne of Green Gables no longer exists (although you can visit the site and see the foundation of her grandparents’ house, and with the help of quotations on the plaques there you can try to picture her at the window of her old room upstairs).

L.M. Montgomery’s grandparents’ homestead

It’s interesting to think of Montgomery’s feeling that seeing the places where Hawthorne, Alcott, and Emerson wrote somehow makes their books more “real.” It must be the same feeling that motivates so many readers of the “Anne” books to make the pilgrimage to Prince Edward Island.

I guess they do need some hired help, to paint Green Gables

Montgomery almost felt that Anne herself was real. A couple of months after her trip to Boston and Concord, she writes that “When I am asked if Anne herself is a ‘real person’ I always answer ‘no’ with an odd reluctance and an uncomfortable feeling of not telling the truth. For she is and always has been, from the moment I first thought of her, so real to me that I feel I am doing violence to something when I deny her an existence anywhere save in Dreamland” (27 January 1911).

Sunset at Cavendish Beach

On the same day that she visited Concord, Montgomery went to see the “Ware Collection of Glass Flowers” at the Agassiz Museum in Cambridge (now in the Harvard Museum of Natural History). Her comments here on what is real and what isn’t are interesting, too. “I wasn’t feeling very anxious to see them for the sound of ‘glass flowers’ didn’t please me. But I am glad I didn’t miss that wonderful collection. Yes they are indeed wonderful—so wonderful that they don’t seem wonderful at all—they seem to be absolutely real flowers and you have to keep reminding yourself that they are made of glass—of glass—to realize how wonderful they are.”

Do glass flowers help us appreciate real flowers even more? Do visits to literary sites make us better, more attentive readers? Maybe. Maybe not. But Montgomery’s belief in what’s real in fiction is apparent in her further comments about her famous heroine Anne Shirley: “She is so real that, although I’ve never met her, I feel quite sure I shall do so someday—perhaps in a stroll through Lover’s Lane in the twilight—or in the moonlit Birch Path—I shall lift my eyes and find her, child or maiden, by my side. And I shall not be in the least surprised because I have always known she was somewhere.” Thus hundreds of thousands of people continue to visit Green Gables every year, many of them in search of “Anne” and that “strange reality.”

L.M. Montgomery was born on this day, November 30, in 1874. Louisa May Alcott was born 181 years ago yesterday, on November 29, 1832.

Quotations are from The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The PEI Years, 1901-1911, ed. Mary Henley Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston (Oxford University Press, 2013). You can read my review of the book on page 33 of the Fall 2013 edition of Atlantic Books Today.

Quotations are from The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The PEI Years, 1901-1911, ed. Mary Henley Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston (Oxford University Press, 2013). You can read my review of the book on page 33 of the Fall 2013 edition of Atlantic Books Today.

November 27, 2013

JASNA Nova Scotia celebrates Jane Austen’s 238th birthday

Would you like to join us for lunch and a toast to Jane Austen in honour of her birthday? We’re celebrating nine days early, on Saturday, December 7th, at 12:30pm at The Cellar Wine Bar & Grill, 5677 Brenton St., Halifax. Christina Simpson will tell us about her experience of this year’s JASNA AGM in Minneapolis, which celebrated 200 years of Pride and Prejudice, and Hugh Kindred will give his annual toast to Jane.

Please let our Regional Coordinator, Anne Thompson, know by December 1st if you’d like to join us, or leave a comment here so I can pass on the information to her. Do come and celebrate with us!

November 19, 2013

3 or 4 Families in an Italian Village

Remembering a happy childhood can bring sadness, says the narrator of Connie Guzzo-McParland’s debut novel The Girls of Piazza d’Amore, because of the “persistent ache of yearning, like the grief for a lost love.” The novel focuses on three or four families in a village in southern Italy at a moment in the 1950s when many people were leaving for a new life in North America: “‘Here, there is no avvenire’”; “‘We must leave for the sake of the children’”; “‘Four houses and four cats’—that is how we spoke about [the village of Mulirena] after we left.” Looking back, the narrator, Caterina, is certain that “I and the village women I’ve known all carry a history and worlds of stories within us.”

Remembering a happy childhood can bring sadness, says the narrator of Connie Guzzo-McParland’s debut novel The Girls of Piazza d’Amore, because of the “persistent ache of yearning, like the grief for a lost love.” The novel focuses on three or four families in a village in southern Italy at a moment in the 1950s when many people were leaving for a new life in North America: “‘Here, there is no avvenire’”; “‘We must leave for the sake of the children’”; “‘Four houses and four cats’—that is how we spoke about [the village of Mulirena] after we left.” Looking back, the narrator, Caterina, is certain that “I and the village women I’ve known all carry a history and worlds of stories within us.”

I reviewed the novel for Publishers Weekly, and you can read my review here. I loved Guzzo-McParland’s descriptions of special treats for the village children, “homemade cullarielli, hard doughnut-shaped cookies glazed with white sugar” and tied to the Palm Sunday olive branches with ribbon, or scirubetta on a December day: “A light blanket of snow covered the rooftops. Mother reached over Comare Rosaria’s rooftop from our kitchen window and filled a bowl with snow. She sprinkled sugar and cold coffee over it to make scirubetta for me, Luigi, and my desk-friend, Bettina, who came over every afternoon to do homework with me.”

My favourite character isn’t one of the village girls whose love stories Caterina recounts, but Professore Nucci, her father’s friend, who “wasn’t really a professor; he just liked to be called Professore,” and therefore introduces himself as one. A bachelor living with his two sisters, “He received a small stipend from the village for doing minor secretarial work, but he spent most of the day walking up and down the main street in a pensive mood, his arms behind his back, a baton in one hand. Sometimes he would stop, look up into the air, and move his head as though he were reviewing a musical score.” Not surprisingly, he also likes it when people call him Maestro.

“‘I wouldn’t go to Canada if they paid me in gold,’” he says, but another villager retorts, “‘Don’t worry, professò. They only pay for professors like you in Mulirena. Everywhere else you have to work.’”

The Girls of Piazza d’Amore, by Connie Guzzo-McParland, is published by Linda Leith Publishing, and you can find the author on Facebook. The novel has been shortlisted for the Quebec Writers’ Federation’s Concordia University First Book Award. Congratulations!