Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 38

November 16, 2013

Highlights from the Jane Austen Festival in Bath

Two of our local JASNA Nova Scotia members, Lou Harrington and Anita Campbell, travelled to Bath, England in September to attend the Jane Austen Festival. Last Sunday, Lou and Anita entertained members of our Region with stories from their adventures at the Festival, and impressed us with the costumes they created to wear for the famous Promenade. Picture 600 people in Regency costume walking from the Royal Crescent to the Parade Gardens near Bath Abbey—or watch this four-minute video, and you can catch a glimpse of Lou at 1:19, and of Anita at 2:25.

Anita and Lou in their Regency finery

Here are some of the highlights they mentioned: tours of Chawton, Steventon, Winchester, and Stoneleigh Abbey; visits to The Royal Pump Rooms at Leamington Spa, The Holburne Museum, The Herschel Museum of Astronomy, The American Museum in Britain, and the newly restored No. 1 Royal Crescent; tea and breakfast in a private home, Kinwarton; and a book launch for A Carriage Ride in Queen Square: Easy-to-Play Piano Pieces for Jane Austen’s Bath, by Gwen Bevan (great-great-granddaughter of Austen’s niece Fanny Knight). Are you envious? I am!

Photo by Lou Harrington

Anita made her linen/cotton dress using a pattern drawn from a museum original dating from around 1800 (from Past Patterns), and her blue linen spencer from a Regency Wardrobe pattern from La Mode Bagatelle. She even made the Dorset buttons herself, using instructions she found online. And—incredibly (to me, at any rate)—she made the bonnet from scratch, using a Lynn McMasters pattern for an early nineteenth-century seaside bonnet. Joleen Gordon from the Nova Scotia Basketry Guild gave her the straw plait, and it took her all summer to sew the straw on by hand. Anita says that while she has no formal training in costume or sewing, she’s always had a personal interest in costume research and she loves historic clothing.

Detail of Anita’s amazing bonnet. Aren’t you tempted, like Austen’s Beautifull Cassandra, to place it on your gentle head and run off to seek your Fortune, or at least some ice cream and adventures?

Lou has a diploma in Costume Studies from Dalhousie University (and a Pharmacy degree, too, which she says feeds her bank account while the Costume Studies diploma feeds her soul). She writes:

My dress on Sunday was a cotton muslin day dress, about mid-Regency. Sleeves and hem trimmed with broiderie anglaise. The spencer is a la militaire, and was fashioned from a modern blazer that I cut off. Brass buttons from my mother’s button jar. The hat came from a charity shop. I imagine someone wore it once to a wedding and then got rid of it. With some careful cutting and stitching, it became a bonnet. A bag of muslin over the crown and some ribbon completed the look. No one but a costume girl would really notice, but the shape is a bit more Gaskell than Austen so I may pull it apart to rework it someday. Just as Lydia might!

This year was Lou’s fifth trip to the Festival. She’s attended every year since her first visit in 2009.

Now, it’s a little-known fact that after my M.A., I too considered Costume Studies at Dalhousie. You might not guess this, given that I don’t have a Regency dress and that the only Regency accessory I’ve ever made is a reticule — copied from one Lou made, and it took me a year to make it. But way back in 1996, the Costume Studies program recreated a beautiful eighteenth-century wedding at St. Paul’s Church in Halifax, and I found the costumes inspiring. Instead of going into Costume Studies, however, I wrote a book about St. Paul’s, and then decided on a Ph.D. in English so I could spend a lot of time reading Jane Austen and writing about her. So here I am, still writing, and not sewing. But I certainly appreciate the work that goes into recreations of historical costumes. (And if I had ever learnt, I should have been a great proficient, I’m sure.)

I’ve been to Bath and several other Jane Austen-related sites in England, but I’ve never been to the Jane Austen Festival. Have any of you been? If you have, what were your favourite events, talks, or tours? Lou and Anita and JASNA NS members: what would you add to my very short summary of the Festival? With nine days of Austen-inspired entertainments, it’s hard to keep track of everything!

November 15, 2013

L.M. Montgomery at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts

My recent trip to one of my favourite places in Boston, the Museum of Fine Arts, reminded me of L.M. Montgomery’s (brief) description of her first experience of the Museum during a trip to Boston to meet her publisher, L.C. Page, in November 1910: “Mrs. Page, the Marcones and I spent the day in the new Museum of Fine Arts. It was a wonderful day—but it should have been a week instead of a day. I had no time to study anything—I could only look and pass on.” I expect many people feel this way about the MFA, or indeed any great art museum—I certainly did a few years ago when I had only an hour and a half to see the brand new Art of the Americas wing at the MFA before leaving for Halifax.

My recent trip to one of my favourite places in Boston, the Museum of Fine Arts, reminded me of L.M. Montgomery’s (brief) description of her first experience of the Museum during a trip to Boston to meet her publisher, L.C. Page, in November 1910: “Mrs. Page, the Marcones and I spent the day in the new Museum of Fine Arts. It was a wonderful day—but it should have been a week instead of a day. I had no time to study anything—I could only look and pass on.” I expect many people feel this way about the MFA, or indeed any great art museum—I certainly did a few years ago when I had only an hour and a half to see the brand new Art of the Americas wing at the MFA before leaving for Halifax.

The Art of the Americas wing (the photo is reminiscent of my banner photo, isn’t it? You can tell that I like bare branches against water and/or sky. I visited again this past August, but I took the photo when I was there in March.)

“And there was so much to look at—I wanted to stand for an hour before everything and absorb it,” Montgomery continues. “The collection of Japanese pottery was marvelous—the amber room was a delight beyond words; the Egyptian department was wonderful and the Greek Statues were—Greek statues. And as for the paintings—but I cannot write about them. I had seen engravings of most of them but to see the pictures themselves was a revelation.”

When Montgomery visited, the MFA had just moved from its original location in Copley Square, where it had been since its founding in 1876, to its current location on Huntington Avenue. The Beaux Arts building was designed by Guy Lowell and opened in November 1909. The Fenway entrance, and the giant baby heads by Antonio Lopez Garcia, were far in the future. One can only imagine what Montgomery would have thought of the sculptures that now greet visitors to the MFA.

“Day and Night,” by Antonio Lopez Garcia (thanks to Elizabeth Baxter for these photos)

Quotations are from The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The PEI Years, 1901-1911, ed. Mary Henley Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston (Oxford University Press, 2013). You can read my review of the book on page 33 of the Fall 2013 edition of Atlantic Books Today.

November 13, 2013

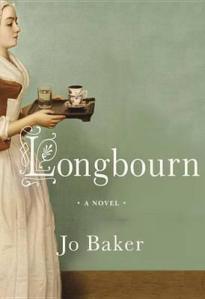

Longbourn – a review

“The very shoe-roses were got by proxy.” This line from Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice sparked Jo Baker’s fascinating exploration of the servants’ world at Longbourn, in a novel that highlights the inequalities and injustices of a system in which some young ladies are born to sew, read, talk, and dance, while others are born to scrub mud and blood from their mistresses’ clothes and underclothes, to cook and clean, and to brave miserable weather for the trivial errand of fetching decorative shoe-roses. Longbourn is not about Mr. and Mrs. Bennet and their five daughters, although the family and their friends and acquaintances do appear in the background, in the way that servants appear in Austen’s novel.

“The very shoe-roses were got by proxy.” This line from Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice sparked Jo Baker’s fascinating exploration of the servants’ world at Longbourn, in a novel that highlights the inequalities and injustices of a system in which some young ladies are born to sew, read, talk, and dance, while others are born to scrub mud and blood from their mistresses’ clothes and underclothes, to cook and clean, and to brave miserable weather for the trivial errand of fetching decorative shoe-roses. Longbourn is not about Mr. and Mrs. Bennet and their five daughters, although the family and their friends and acquaintances do appear in the background, in the way that servants appear in Austen’s novel.

A spirited maid named Sarah and the mysterious new footman at Longbourn, James, are the heroine and hero of this story, while Elizabeth Bennet appears only briefly and Mr. Darcy is hardly mentioned at all. The other servants are Mrs. Hill, the housekeeper; her husband, the butler; and Polly, another maid. Let me say right away that Baker’s Elizabeth is very different from Austen’s. Gentle Jane, wicked Wickham, and silly Kitty, Lydia, and Mrs. Bennet, for example, are all recognizable here, but in Longbourn, Elizabeth is generally thoughtless and even unkind. It’s she who says, with a “sorrowful glance” at the rain outside, that those shoe-roses will have to be got by proxy, meaning by Sarah. Utterly self-absorbed, she shows no interest in her maid beyond a vague and misguided assumption that Sarah will be keen to visit London and see more of the world. Austen’s Elizabeth is sharp, quick to judge, and slow to understand herself, but she is unkind only to those who have slighted her, such as Mr. Darcy or Miss Bingley – and we aren’t given any reason in Longbourn to believe Sarah has offended her.

There are a couple of ways of reading this new version of Elizabeth, depending on the degree to which you see fidelity to the original novel as essential in an adaptation. In Baker’s defense, she isn’t continuing Austen’s story, she’s creating a new story, and her Sarah and James are certainly capable of holding the reader’s attention and sympathy themselves, whether her Elizabeth does or not. (P.D. James’s Death Comes to Pemberley, on the other hand, also features an Elizabeth Bennet who lacks the wit and energy of Austen’s heroine, but while James’s Darcy and Wickham get all the attention in her sequel to Pride and Prejudice, neither one of them sparkles very much either, so there’s little compensation.)

Sarah and James win our sympathy not only because they have difficult, unpleasant jobs – like scouring pans and scrubbing filthy petticoats or emptying sloshing chamberpots – but because of their tenacity and courage as they struggle to make a good life for themselves. They don’t give up, even when it seems fate is against them – and it almost always seems that fate is against them. I won’t give away too many details of what happens to them, but James, for example, holds fast to his belief that truth will win out: “he would not be punished for something he had not done.” And if Baker’s Elizabeth has lost her confidence and her kindness, Sarah has gained both. She speaks up fearlessly to James, sparring with him in the way Austen’s Elizabeth challenges Darcy, and she offers protection to Polly when Wickham gets too close.

It’s clever to foreground the servants’ lives, but Longbourn isn’t the story of just any early nineteenth century servants, and the debt the novel owes to Pride and Prejudice means we’re invited, even obliged, to read one in light of the other. I don’t mean that slavish imitation is required, but it shouldn’t be necessary to make readers dislike the Bennets and others of their class in order to increase our sympathy for their servants. Isn’t it possible to sympathize with both the maid who scrubs the petticoats and the woman who employs her?

Longbourn’s focus on the perceived plight of the minor characters extends not only to the servants, but also to Mr. Collins and Mary Bennet. All of them, according to this interpretation, have been wronged by the Bennets, chiefly Elizabeth. Baker’s determination to rehabilitate the characters Elizabeth criticizes leads to a brief section in which she gives us Mary Bennet’s point of view, which is jarring because it’s the one place we leave the minds of the servants. Mary has allowed herself to dream of marriage to Mr. Collins, “of the new importance that it would bring to her,” imagining that “on becoming Mr. Collins’s bride, she would have also become the means of her family’s salvation, and no longer just the plain, awkward, overlooked middle child.” This passage, along with passages that present Mr. Collins as well-meaning and misunderstood, suggests that Longbourn isn’t just “The Servants’ Story,” as the novel’s subtitle has it, but the story of the characters who in Pride and Prejudice are denied the sympathy of either Elizabeth or the narrator or both of them. I was almost surprised to find that Baker didn’t include a defense of Miss Bingley.

Longbourn is a moving love story that could almost stand on its own, as Baker gives us powerful new characters whose courage in the face of adversity makes for compelling reading. And its premise is intriguing: the novel offers a new way of looking at Austen’s world, reminding us in vivid and disturbing detail of the way elegant Regency lifestyles depended heavily on the labour of servants. Yet ultimately, Longbourn’s distortion of the very characters, especially the heroine, whose story inspired this one, means that it disappoints. The servants’ story would be more successful if the novel didn’t oversimplify tensions between the classes by demanding that readers learn to dislike, or even despise, Elizabeth Bennet.

For further reading:

Sarah Seltzer discusses Longbourn in “How to make a Jane Austen reboot that’s actually good,” Salon, November 11, 2013: “Often, though, Baker’s effort at ‘rewriting’ the characters to show their privilege feels didactic – we get it, they’re enabling the gears of oppression.”

Margaret C. Sullivan’s review of Longbourn at Austenblog, November 3, 2013: “We struggled through this book, constantly pulled out of it by this determination to dunk Austen’s work in a literary mud puddle. It seems to us a subversion of Pride and Prejudice, not a celebration of it.”

Syrie James’s review of Longbourn at Austenprose, October 16, 2013: “Jo Baker’s engrossing novel … takes Jane Austen’s famous work, turns it upside down, and shakes out a fully realized and utterly convincing tale of life and romance among the servants.”

“Pride, Prejudice, and Drudgery,” Diane Johnson’s review of Longbourn in the New York Times Sunday Book Review, October 11, 2013: “a work that’s both original and charming, even gripping, in its own right.”

November 7, 2013

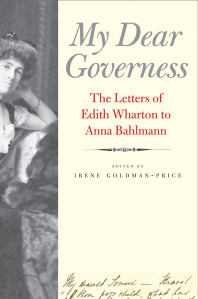

How Much Did Edith Wharton Revise The Custom of the Country?

Tenth and last in a series celebrating the 100th Anniversary of Edith Wharton’s novel The Custom of the Country.

“I have just received duplicate galleys of the last two chapters, & these are still so fresh in my mind that I have revised them & hurried them off to Scribner by this post, with a line to say that they are to be used for the book if not too late.” On August 29, 1913,  Edith Wharton was writing to her secretary, Anna Bahlmann about preparing the text of The Custom of the Country for publication that fall. The novel had been serialized in Scribner’s Magazine in monthly installments, beginning in January, and the first edition of the novel was to be published in October.

Edith Wharton was writing to her secretary, Anna Bahlmann about preparing the text of The Custom of the Country for publication that fall. The novel had been serialized in Scribner’s Magazine in monthly installments, beginning in January, and the first edition of the novel was to be published in October.

As I discovered when my sister Elizabeth Baxter and I compared the serialized version of the novel with the first edition, word by word, while Wharton made some changes to the last three chapters of the novel, in Book Five, she didn’t make as many there as she had in the Books One and Two. She made some revisions in Books Three and Four, but none at all in Chapters 37 through 43 of Book Five.

She appears to have debated whether or not to revise the chapters towards the end at all: a letter to Anna Bahlmann from August 26th says she “will try to revise the remaining chapters of the ‘Custom’ (for the book)” as “I feel less tired.” Had she been too tired to revise the earlier chapters in Book Five?

One interesting change is that in the last paragraph of the novel, the magazine text says of Undine Spragg that “There was something she could never get,” whereas the first edition text says “She had learned that there was something she could never get.” The revision suggests that for all her blindnesses, Undine is capable of learning something. Her divorce and remarriage in the last chapter take place in Sioux Falls, in the magazine text, but in Reno in the first edition. Sioux Falls, South Dakota, was where she went for her divorce from Ralph Marvell.

In Chapter 44 in the first edition, Mrs. Jim Driscoll and Bertha Shallum “received [Undine] with a touch of constraint; but it vanished when they remarked the cordiality of Moffatt’s greeting.” The magazine text refers to “the long-established intimacy of Moffatt’s greeting.” Undine knows how long she and Moffatt have been intimate, but the other women would see only that his manner is cordial, without knowing exactly why.

Some of the revisions soften the language somewhat: in Chapter 44, Moffatt’s “great gaudy sitting-room” in the Nouveau Luxe in the magazine text becomes simply a “big bright sitting-room.” In Chapter 45, Undine’s response to Moffatt’s request that she go home to America with him is quite different: in the first edition of the novel, she “picture[s] the consequences of what he exacted.” In the magazine text, on the other hand, she “picture[s] the consequences of the monstrous renunciation he exacted.” Here’s the next paragraph from the magazine text:

“You don’t know—you don’t understand—” she kept repeating; but she knew it was part of his terrible power that he didn’t: that his very ignorance of the coil of conventions she was trapped in turned their impenetrable net into a cobweb. It was hopeless to try to make him feel the value of what he was asking her to give up.”

And here’s what the paragraph looks like in the first edition, after Wharton’s revisions:

“You don’t know—you don’t understand—” she kept repeating; but she knew that his ignorance was part of his terrible power, and that it was hopeless to try to make him feel the value of what he was asking her to give up.

He still has a “terrible power,” but there’s no “coil of conventions,” “impenetrable net,” or “cobweb,” and she isn’t “trapped.” The barriers to serial divorce and serial marriage are not as strong in the revised version of the novel.

He still has a “terrible power,” but there’s no “coil of conventions,” “impenetrable net,” or “cobweb,” and she isn’t “trapped.” The barriers to serial divorce and serial marriage are not as strong in the revised version of the novel.

If you’re interested in the revisions Wharton made earlier in the novel, especially in Books One and Two, you can read more about them in the “Note on the Text” in my edition of The Custom of the Country.

Thanks for celebrating the 100th anniversary of this fabulous novel with me this year! Cheers to Edith Wharton—and to Undine Spragg—and here’s to their next century.

For further reading:

The Custom of the Country, by Edith Wharton, edited by Sarah Emsley (Peterborough, ON: Broadview, 2008).

My Dear Governess: The Letters of Edith Wharton to Anna Bahlmann, edited by Irene Goldman-Price (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012).

My other posts on The Custom of the Country:

Part One: How I Discovered The Custom of the Country

Part Three: “I’ll never try anything again till I try New York”

Part Four: Undine Spragg as the Empress Josephine

Part Five: Marriage, Divorce, and “diversified elements of misery”

Part Six: “Diamonds are a Girl’s Best Friend”

Part Eight: What Edith Wharton Tells Us About The Way We Live Now

Part Nine: Edith Wharton’s Portrait of a Lady—Mr. Popple’s portraits and Undine’s powers

That moment when you’re revising obsessively and it feels like “an attack of scrupulosis”…: On revising The Custom of the Country

Happy 100th Anniversary to Edith Wharton’s The Custom of the Country! The first installment of the novel was published in Scribner’s Magazine in January 1913.

Writing with “dogged obstinacy”: In the summer of 1911, Edith Wharton was “digging away” at her “Big Novel,” The Custom of the Country, wondering if “dogged obstinacy” could “replace freedom & inspiration.”

“The books were too valuable to be taken down”: On Undine Spragg’s treatment of her son Paul in the last chapter of The Custom of the Country, and Paul’s experience of nightmarish library in which the books can never be read, and no one ever writes.

French Fact and American Fiction: Wharton’s use of place names in The Custom of the Country.

November 5, 2013

Plan for JASNA 2014 and hear about the 2013 Jane Austen Festival

The next JASNA Nova Scotia meeting is at 2pm this Sunday, November 10th at Anne Thompson’s house. We’ll talk about our plans for next year’s AGM in Montréal, and hear from Lou Harrington and Anita Campbell about their experience at the Jane Austen Festival in Bath this past September. Both Anita and Lou are very accomplished seamstresses — as you can tell from their Regency costumes in the photos below — as well as devoted readers of Austen’s novels, and from what I’ve heard so far, it sounds as if they had a wonderful time in Bath.

Please join us for tea, and please tell Anne if you’re able to be there (or let me know in the comments below, and I can give you directions if needed).

Anita and Lou and friends at the Jane Austen Festival

Anita and the Pulteney Bridge

November 4, 2013

What’s the best way to introduce kids to Jane Austen?

I want to hear your ideas! I’ve put together a list of Jane Austen-related books for children that includes the Cozy Classics and BabyLit board books, the Real Reads abridged versions of Austen’s novels, and Juliet McMaster’s wonderful illustrated edition  of Austen’s story “The Beautifull Cassandra.” This list is a work-in-progress and I hope you’ll help me add to it, with suggestions for books I may have overlooked and film adaptations that are appropriate for watching with young children, along with any other ideas you have for introducing kids to the works of Jane Austen.

of Austen’s story “The Beautifull Cassandra.” This list is a work-in-progress and I hope you’ll help me add to it, with suggestions for books I may have overlooked and film adaptations that are appropriate for watching with young children, along with any other ideas you have for introducing kids to the works of Jane Austen.

I haven’t listed any of the movies yet, though off the top of my head I think the 1995 Pride and Prejudice belongs on the list, while the 1999 Mansfield Park does not. What do you think? I’d cut the first scene from the 2007 Sense and Sensibility for obvious reasons, but I’m trying to remember if the rest of it would be okay to watch with children.

Please add your comments and suggestions either here or on my “Jane Austen for Kids” page. Thank you!

October 30, 2013

The Real Reads Sense and Sensibility – a review

Gill Tavner’s abridged version of Sense and Sensibility makes radical, and successful, changes to Jane Austen’s novel. The key to her adaptation is the choice to tell the story of Elinor and Marianne Dashwood in the first person, from the perspective of their younger sister Margaret. A minor character in Austen’s novel, Margaret is close enough to her sisters to watch their romances unfold, and understandably interested to see what her own future as an eligible young woman might be. Emma Thompson’s screenplay for the 1995 film of Sense and Sensibility expanded Margaret’s role, making her a more lively character who enjoys joking with Edward Ferrars, but here Tavner makes Margaret even more central, as she becomes the main reader of her sisters’ lives and the choices they make about romance and marriage.

Gill Tavner’s abridged version of Sense and Sensibility makes radical, and successful, changes to Jane Austen’s novel. The key to her adaptation is the choice to tell the story of Elinor and Marianne Dashwood in the first person, from the perspective of their younger sister Margaret. A minor character in Austen’s novel, Margaret is close enough to her sisters to watch their romances unfold, and understandably interested to see what her own future as an eligible young woman might be. Emma Thompson’s screenplay for the 1995 film of Sense and Sensibility expanded Margaret’s role, making her a more lively character who enjoys joking with Edward Ferrars, but here Tavner makes Margaret even more central, as she becomes the main reader of her sisters’ lives and the choices they make about romance and marriage.

Any writer who creates an abridged version of a classic novel faces difficult choices about what to leave out and what parts of the plot and characters must remain for the story to be comprehensible. One of the greatest strengths of the Real Reads series of abridged novels (and other classic works) is that at the end of the book, there’s a section called “Taking Things Further” that advises interested readers to seek out “the full novel in all its original splendour,” explains the “sad but necessary” process of omitting subplots and details, and gives additional information designed to “fill in some of the gaps,” while acknowledging that “nothing can beat the original.”

This edition includes a brief essay about the social context in which Austen wrote Sense and Sensibility, and while many readers would argue with the assertion that “Jane  Austen does not include politics in her novels,” the essay is otherwise helpful in explaining the importance of marriage and the moral code by which courtships were judged in Austen’s time, along with an introduction to the contrast between the “age of reason” and the “age of feeling.” A bibliography, a list of Austen-related websites, and a few discussion questions about characters, themes, and style complete the volume. Carol Shields’s short biography of Austen would be an excellent addition to this bibliography that’s designed to introduce readers to Austen’s life and work.

Austen does not include politics in her novels,” the essay is otherwise helpful in explaining the importance of marriage and the moral code by which courtships were judged in Austen’s time, along with an introduction to the contrast between the “age of reason” and the “age of feeling.” A bibliography, a list of Austen-related websites, and a few discussion questions about characters, themes, and style complete the volume. Carol Shields’s short biography of Austen would be an excellent addition to this bibliography that’s designed to introduce readers to Austen’s life and work.

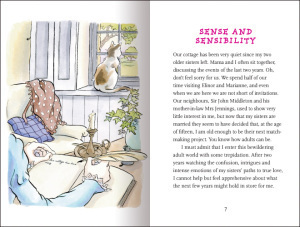

As in her abridged Pride and Prejudice, where she immediately takes the reader to the heart of the conflict between Elizabeth and Darcy by dramatizing Darcy’s first proposal, Tavner’s choice of opening lines is very different from Austen’s. Instead of rehearsing the family history of the Dashwoods, the Real Reads version of Sense and Sensibility gives us Margaret’s voice and her reflections on what’s happened to her sisters and  what’s next for her own prospects for love and marriage. “I must admit,” she says, “that I enter this bewildering adult world with some trepidation. After two years watching the confusion, intrigues and intense emotions of my sisters’ paths to true love, I cannot help but feel apprehensive about what the next few years might hold in store for me.” It’s clear right away that Margaret is someone a younger reader can identify with, an observer of the strangeness of the adult world. Left in Barton Cottage with her mother after her sisters marry, she has plenty of free time and she decides to fill it with the project of writing down the story of Elinor and Marianne. She’s well aware, however, that her neighbour Sir John Middleton and his mother-in-law are thinking of her as “their next matchmaking project.”

what’s next for her own prospects for love and marriage. “I must admit,” she says, “that I enter this bewildering adult world with some trepidation. After two years watching the confusion, intrigues and intense emotions of my sisters’ paths to true love, I cannot help but feel apprehensive about what the next few years might hold in store for me.” It’s clear right away that Margaret is someone a younger reader can identify with, an observer of the strangeness of the adult world. Left in Barton Cottage with her mother after her sisters marry, she has plenty of free time and she decides to fill it with the project of writing down the story of Elinor and Marianne. She’s well aware, however, that her neighbour Sir John Middleton and his mother-in-law are thinking of her as “their next matchmaking project.”

Margaret’s tone can be informal at times, as when she adds here, speaking of Sir John and Mrs. Jennings, “You know how adults can be.” Most of the time, the informal tone is appropriate and conversational, although at one point it’s jarringly modern. When she tells Elinor that she saw Willoughby cut off a lock of Marianne’s hair, she says Elinor “told her off for not respecting their privacy.”

If Margaret is to narrate the full story, she has to be present in more of the scenes than she is in Austen’s novel, and thus Tavner has her accompany her sisters to London when they stay with Mrs. Jennings. This is a bit of a stretch, as she would be considered too young for a London visit to be of any use to her social career, but it allows Tavner to have her witness important scenes, and the fact that Austen doesn’t send her to London is the very first thing pointed out in the section at the end on “filling in gaps.” It’s believable that Margaret would watch Marianne’s impatience for a letter or a visit from Willoughby, and even that she would happen to overhear Colonel Brandon telling Elinor about how Willoughby abandoned his ward, Eliza. And Tavner thankfully stops short of showing Margaret at the party where Marianne at last sees Willoughby. Margaret explains that she’s “Too young for a London party,” and she waits impatiently to find out what’s happening.

Whether I’m reading an abridged version of an Austen novel or watching a film adaptation of one of them, I always think about the brilliance of the original, and sometimes I wonder why we seek out these reinterpretations of her work instead of just reading and rereading what she wrote. I confess there are moments at which I feel that I’m an Austen purist at heart—and I do think it’s very important to keep returning to the novels themselves, to focus on the characters and plots she created, to appreciate the subtleties of her style and her moral vision. There are now so many stories, novels, films, games, board books, t-shirts, coffee mugs, and so on, that are linked in some way to Austen’s life and fiction that it would be easy to fill a lifetime with Austen ephemera and to lose sight of the original works entirely.

At the same time, I definitely appreciate the richness of the range of ways in which writers have been inspired to offer new perspectives on the originals, many (though certainly not all) of which are entertaining and wonderful in their own right. This version of Sense and Sensibility makes me think afresh about what it meant to be a young girl in Austen’s time, wondering what the future would bring. It’s an excellent introduction to the novel for young readers. Respectful, smart, and playful, Gill Tavner’s Real Reads adaptations belong with the very best of the many reinterpretations of Austen’s novels.

Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility was published 202 years ago today, on October 30, 1811.

October 28, 2013

Elaine Bander in Halifax; Mansfield Park in Montréal

Well, what a great weekend we’ve just had here in Halifax, with Elaine Bander, President of JASNA Canada, in town. She gave a wonderful talk on Friday afternoon in the Dalhousie University Department of English Seminar Series. Members of JASNA Nova Scotia gathered with faculty and students from Dal and other local universities, along with members of the general public, to hear Elaine speak on “Jane Austen’s Fanny Price and Lord Nelson: Rethinking the National Hero(ine).”

Well, what a great weekend we’ve just had here in Halifax, with Elaine Bander, President of JASNA Canada, in town. She gave a wonderful talk on Friday afternoon in the Dalhousie University Department of English Seminar Series. Members of JASNA Nova Scotia gathered with faculty and students from Dal and other local universities, along with members of the general public, to hear Elaine speak on “Jane Austen’s Fanny Price and Lord Nelson: Rethinking the National Hero(ine).”

Elaine discussed passages in Jane Austen’s letters that suggest she was thinking about “models of principled resistance” in several books, including Thomas Clarkson’s History of the Abolition of the Slave Trade (1808), while she was writing Mansfield Park. Austen’s characterization of Fanny Price may have been influenced by her readings of masculine  heroism. Fanny looks like a frail heroine, but her principled and steady resistance to her family’s attempts to persuade her to marry Henry Crawford shows that she is far more powerful than she appears. Elaine drew our attention to yet another model of heroism that may have influenced Austen, Robert Southey’s Life of Lord Nelson (1813). Without claiming that Southey’s book was a direct influence, Elaine suggested that the idea of Nelson’s heroism may have prompted Austen to explore what happens when a timid young woman decides to be courageous. I like the idea of Fanny saying to herself, as Nelson did, “Well then, … I will be a hero.” Elaine pointed out that the “scale of her endeavor” is different, “but not her courage.”

heroism. Fanny looks like a frail heroine, but her principled and steady resistance to her family’s attempts to persuade her to marry Henry Crawford shows that she is far more powerful than she appears. Elaine drew our attention to yet another model of heroism that may have influenced Austen, Robert Southey’s Life of Lord Nelson (1813). Without claiming that Southey’s book was a direct influence, Elaine suggested that the idea of Nelson’s heroism may have prompted Austen to explore what happens when a timid young woman decides to be courageous. I like the idea of Fanny saying to herself, as Nelson did, “Well then, … I will be a hero.” Elaine pointed out that the “scale of her endeavor” is different, “but not her courage.”

The talk was followed by a wine and cheese reception, courtesy of the Dal English Department. Here’s a photo of Elaine in conversation with Sheila Johnson Kindred, a JASNA NS member who teaches Philosophy at Saint Mary’s University, and John Baxter, Professor of English at Dalhousie, who introduced Elaine’s talk. Sara Malton, who teaches 19th Century literature at Saint Mary’s, and David Monaghan, who is retired from the English Department at Mount Saint Vincent University, interrupted their conversation to smile for the camera.

Sara Malton, Elaine Bander, Sheila Johnson Kindred, John Baxter, David Monaghan

JASNA Nova Scotia members enjoyed talking with Elaine over a dinner hosted by Anita Campbell on Friday night, and on Saturday, several members met again to take the ferry from Halifax to Dartmouth for lunch with Elaine at a favourite local restaurant with a fabulous view of Halifax harbour, The Wooden Monkey.

Sheila Kindred, Elaine Bander, Lou Harrington, Anne Thompson, Carole Thompson

Dartmouth, from the ferry

It was another glorious October day in Nova Scotia – the perfect day for a trip across the water – and we enjoyed hearing Elaine’s description of her plans for the 2014 JASNA AGM: “Mansfield Park in Montréal: Contexts, Conventions & Controversies.” Members of our Region are looking forward to attending the AGM and offered support for the event.

It’s sure to be a great weekend: the combination of Mansfield Park and Montréal is irresistible. The museums! The cafés and restaurants! The bicycles! The controversial and brilliant Mansfield Park! And what a line-up of plenary speakers: Robert Miles (University of Victoria) on “Mansfield Park and Moral Luck,” Lynn Festa (Rutgers University) on “Mansfield Park and Noise,” and Patrick Stokes (former chairman of the Jane Austen Society, UK – and a direct descendant of Jane Austen’s brother Charles) on “‘Rears and Vices’: The Georgian Royal Navy.” And, of course, there will be many breakout sessions, workshops, and other activities (I’m really hoping for a Sunday morning run, as I loved the one we did at the Philadelphia AGM) – and a Regency Ball. October 10-12, 2014 at Le Centre Sheraton Montréal Hotel. Book your hotel room now, join JASNA if you aren’t already a member, and register for the conference next May.

Many thanks, once again, to Elaine for coming to Halifax, and to JASNA Canada, the Department of English at Dalhousie University, especially Len Diepeveen, David Evans, Mary Beth MacIsaac, and John Baxter, and the members of JASNA Nova Scotia, especially Anita Campbell, Carole Thompson, Sheila and Hugh Kindred, and our Regional Coordinator Anne Thompson, for making this weekend possible.

October 24, 2013

Edith Wharton’s Portrait of a Lady

Part Nine in a series celebrating the 100th Anniversary of Edith Wharton’s novel The Custom of the Country.

During her New York years, Undine Spragg—now Mrs. Ralph Marvell—hires Claud Walsingham Popple to paint her portrait. In society’s view, it’s one of Popple’s “merits that he always subordinated art to elegance, in life as well as in his portraits. The ‘messy’ element of production was no more visible in his expensively screened and tapestried studio than its results were perceptible in his painting; and it was often said, in praise of his work, that he was the only artist who kept his studio tidy enough for a lady to sit to him in a new dress” (Chapter 14).

When several guests are invited to tea to see the portrait for the first time, they’re greeted by the “full-length portrait of Mrs. Ralph Marvell, who, from her lofty easel and her heavily garlanded frame, faced the doorway with the air of having been invited to ‘receive’ for Mr. Popple.” As Emily J. Orlando writes in Edith Wharton in Context, “Undine Spragg typifies the women of Wharton’s later fiction who manage to draw pleasure and power from a culture of display by overseeing their own representation and making

Mrs. Ralph Curtis, by John Singer Sargent

compromises that ensure their survival.” Suggesting that Popple is “a veiled John Singer Sargent,” Orlando says “Wharton may have had in mind Sargent’s ‘Mrs. Ralph Curtis’ when she unveiled Undine’s full-length portrait.” Both Undine and Lisa Colt Curtis have “rosy gold” hair and “shimmering” dresses. Orlando writes that “Both portraits suggest the subject’s self-possession as well as her confidence in the power her beauty might purchase.”

Undine is beginning to feel that she made a mistake in marrying into the Marvell family—“that she had given herself to the exclusive and the dowdy when the future belonged to the showy and the promiscuous; that she was in the case of those who have cast in their lot with a fallen cause, or—to use an analogy more within her range—who have hired an opera box on the wrong night.”

But when the portrait is revealed, “the success of the picture obscured all other impressions. She saw herself throning in a central panel at the spring exhibition, with the crowd pushing about the picture, repeating her name; and she decided to stop on the way home and telephone her press-agent to do a paragraph about Popple’s tea.” Seeing the portrait of herself enhances her sense of her own beauty and importance, and gives her further confidence about the successes she’ll enjoy in the future.

For further reading:

“Visual Arts,” by Emily J. Orlando, in Edith Wharton in Context, ed. Laura Rattray (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

Next in this series: Part Ten: How Much Did Edith Wharton Revise The Custom of the Country?—revisions between the serialized text published in Scribner’s Magazine and the text of the first edition

My other posts on The Custom of the Country:

Part One: How I Discovered The Custom of the Country

Part Three: “I’ll never try anything again till I try New York”

Part Four: Undine Spragg as the Empress Josephine

Part Five: Marriage, Divorce, and “diversified elements of misery”

Part Six: “Diamonds are a Girl’s Best Friend”

Part Eight: What Edith Wharton Tells Us About The Way We Live Now

That moment when you’re revising obsessively and it feels like “an attack of scrupulosis”…: On revising The Custom of the Country

Happy 100th Anniversary to Edith Wharton’s The Custom of the Country! The first installment of the novel was published in Scribner’s Magazine in January 1913.

Writing with “dogged obstinacy”: In the summer of 1911, Edith Wharton was “digging away” at her “Big Novel,” The Custom of the Country, wondering if “dogged obstinacy” could “replace freedom & inspiration.”

“The books were too valuable to be taken down”: On Undine Spragg’s treatment of her son Paul in the last chapter of The Custom of the Country, and Paul’s experience of nightmarish library in which the books can never be read, and no one ever writes.

French Fact and American Fiction: Wharton’s use of place names in The Custom of the Country.

October 20, 2013

Elaine Bander’s talk on Mansfield Park – this Friday!

How wonderful for Halifax that Elaine Bander is coming here to give a talk on Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park at Dalhousie University on Friday. Please join us in the English Department (Rm. 1198, McCain Arts and Social Sciences Building, 6135 University Avenue) at 3:45pm to listen to Elaine talk about “Jane Austen’s Fanny Price and Lord Nelson: Rethinking the National Hero(ine).”

Elaine is warm, witty, and wonderful, and I’m so glad she’s coming to visit us. She’s coordinating the 2014 Jane Austen Society of North America AGM on Mansfield Park, next October in Montréal, and she’s the President of JASNA Canada. If you missed my  interview with her a couple of weeks ago, you can find it here. She talks about her work on Austen and Frances Burney, her experience as the JASNA International Visitor in 2011, and why she thinks Austen is so popular these days. And, of course, she gives us a glimpse of some of the exciting things we can look forward to at next year’s AGM.

interview with her a couple of weeks ago, you can find it here. She talks about her work on Austen and Frances Burney, her experience as the JASNA International Visitor in 2011, and why she thinks Austen is so popular these days. And, of course, she gives us a glimpse of some of the exciting things we can look forward to at next year’s AGM.

We’re getting close to the end of the Year of Pride and Prejudice, and that means the Year of Mansfield Park is almost here. Mansfield Park is darker and more controversial than light, bright, and sparkling P & P, but it’s a powerful, richly rewarding novel. 200 years of Mary  Crawford’s charms and games of speculation. 200 years of Fanny Price and her heroic resistance to the overbearing men and women in her life. Let’s start the celebrations on Friday! If you’re in (or near) Halifax, I hope you’ll join us for Elaine’s talk and a reception afterwards.

Crawford’s charms and games of speculation. 200 years of Fanny Price and her heroic resistance to the overbearing men and women in her life. Let’s start the celebrations on Friday! If you’re in (or near) Halifax, I hope you’ll join us for Elaine’s talk and a reception afterwards.

On behalf of JASNA Nova Scotia, I’d like to say thanks to JASNA and Dalhousie’s Department of English for making this event possible.