Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 36

March 15, 2014

Point Pleasant Park as a Cure for Homesickness

L.M. Montgomery went for a walk in Point Pleasant Park in the early evening of Saturday, March 15, 1902, feeling miserable and lonely, and the pines and the spring air cured her of her terrible homesickness—at least temporarily. She was in Halifax for a year, working as a “newspaper woman” at the Daily Echo, and while there were parts of the job that she enjoyed, she disliked the city (“Halifax is the grimiest city in Canada—I know it is!”) and she missed the countryside around her home in Cavendish, PEI.

Point Pleasant Park on March 14, 2014

She writes of the contrast between the “fine and sunny” day, and her feeling of being “oh, so lonesome! There doesn’t seem to be any connection between the two ideas in that sentence and there isn’t. It just came so. There were hundreds of people in the park and I didn’t know one of them. For awhile I hated life!”

It wasn’t until she left the busy shore road and “fled up into a wilderness of pines and along the Serpentine [path] until at last I found myself alone—and then I was no longer lonesome!” She writes, “It was delicious there. The fresh, chill spring air was faintly charged with the aroma of pine balsam and the sky over me was clear and blue—a great inverted cup of blessing. How glorious it was to see the sky once more, undarkened by rows of grimy houses!”

Serpentine Road, March 14, 2014

Pines are her favourite of all trees, Montgomery writes here, and next to them, fir trees. “There is something in these trees—some indefinable charm—that is not found in deciduous trees, beautiful and lovable as these are, too.”

The land at Point Pleasant Park belongs to the British Crown, and the lease is one shilling a year. Many of the trees were destroyed in Hurricane Juan in 2003, but careful management has since revitalized the park and its beautiful forest. The park is one of my favourite places in Halifax — a great place to run, walk, or picnic.

Quotations are from The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The PEI Years, 1901-1911, ed. Mary Henley Rubio and Elizabeth Hillman Waterston (Oxford University Press, 2013).

Recent posts on L.M. Montgomery:

L.M. Montgomery’s Literary Pilgrimage to Concord, Mass.

L.M. Montgomery at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts

March 6, 2014

Jane Austen is as Cool as a Cream Cheese

Jane Austen rarely uses similes or metaphors, but when she does, they’re memorable ones. In Jane Austen and Food, Maggie Lane reminds us of one of the most famous lines in Emma – “it darted through her with the speed of an arrow, that Mr Knightley must marry nobody but herself” – and draws our attention to the two food-related similes in Lesley Castle. Charlotte Luttrell describes her sister’s face as “White as a Whipt Syllabub,” and maintains that she herself is “as cool as a Cream-cheese.”

Jane Austen rarely uses similes or metaphors, but when she does, they’re memorable ones. In Jane Austen and Food, Maggie Lane reminds us of one of the most famous lines in Emma – “it darted through her with the speed of an arrow, that Mr Knightley must marry nobody but herself” – and draws our attention to the two food-related similes in Lesley Castle. Charlotte Luttrell describes her sister’s face as “White as a Whipt Syllabub,” and maintains that she herself is “as cool as a Cream-cheese.”

Where else does Austen mention cream cheese? In Mansfield Park, of course: “There, Fanny,” says Mrs. Norris, “you shall carry that parcel for me; take great care of it: do not let it fall; it is a cream cheese, just like the excellent one we had at dinner. Nothing would satisfy that good old Mrs. Whitaker, but my taking one of the cheeses. I stood out as long as I could, till the tears almost came into her eyes, and I knew it was just the sort that my sister would be delighted with. That Mrs. Whitaker is a treasure!”

Jane Austen and Food was first published by The Hambledon Press in 1995 and is now available as an e-book from Endeavour Press. You can read my review of this fascinating book at Austenprose.com:

Is it easier or harder to write if you’re also responsible for feeding and looking after your family? “Composition seems to me impossible, with a head full of joints of mutton and doses of rhubarb,” Jane Austen wrote to her sister Cassandra in September 1816, after a period in which she managed the household at Chawton Cottage in Cassandra’s absence. Fortunately for Jane – and for us, as readers of her fiction – most of the time it was Cassandra who filled this role, freeing Jane to write.

Click here to read the rest of the review.

And if you ever happen to forget where to find these references to cream cheese, you can always find them again in Maggie Lane’s helpful and entertaining “Index of Food and Drink in Jane Austen’s Fiction.” A few of the other things you’ll find there: apple dumplings, arrowroot, curry, custard, gooseberry tart, pigeon-pie, turnip, and venison pasty. Tea appears more often than coffee, not surprisingly, and wine more often than beer. One of the many charming details Lane discusses is the fact that “the only friendly exchange of a recipe in any of the novels takes place between two men, when Mr Elton jots down (with the bit of pencil which Harriet later spirits away) instructions for making spruce beer given by Mr Knightley.”

And if you ever happen to forget where to find these references to cream cheese, you can always find them again in Maggie Lane’s helpful and entertaining “Index of Food and Drink in Jane Austen’s Fiction.” A few of the other things you’ll find there: apple dumplings, arrowroot, curry, custard, gooseberry tart, pigeon-pie, turnip, and venison pasty. Tea appears more often than coffee, not surprisingly, and wine more often than beer. One of the many charming details Lane discusses is the fact that “the only friendly exchange of a recipe in any of the novels takes place between two men, when Mr Elton jots down (with the bit of pencil which Harriet later spirits away) instructions for making spruce beer given by Mr Knightley.”

If you haven’t yet seen the hilarious reference to cream cheese in the comic strip advertisement from Jane Austen Books, you can see it here, in my interview with Amy Patterson.

February 27, 2014

Milk Fever – a review

“My head and heart informed me that mothering wasn’t contrary to learning, yet instead part of it. I can write and reflect and talk philosophy just as I can suckle a child. No one can tell me . . . that it is not a woman’s privilege to do both,” writes Armande Vivant in a diary entry in 1784 in Lissa M. Cowan’s debut novel, Milk Fever.

I was intrigued by the premise of Milk Fever, partly because I was reminded of Jane Austen’s famous breastfeeding metaphor (with its echo of the biblical passage from the book of Isaiah). “I can no more forget [Sense and Sensibility], than a mother can forget her sucking child,” Austen wrote to her sister Cassandra when she was reading the proofs for her first novel (25 April 1811). Early in Milk Fever, Armande’s friend Celeste realizes that “books were a kind of food, and that reading was what made Armande’s milk different.” I reviewed the novel for Publishers’ Weekly:

On the eve of the French Revolution, a well-educated wet nurse named Armande Vivant disappears, and the peasant girl she and her father adopted and educated resolves to find her because she believes Armande’s ‘extraordinary’ milk has the power not only to nourish babies, but also to educate and transform the people of France . . . .

Read the rest of the review here.

February 13, 2014

Planning the Mansfield Park Party

Friday, May 9th is the big day for the launch of my series of guest posts celebrating 200 years of Mansfield Park. I am absolutely delighted that Lyn Bennett is going to kick things off that day by writing about the opening paragraph of the novel. Lyn teaches in the Department of English at Dalhousie University and she’s the author of Women Writing of Divinest Things: Rhetoric and the Poetry of Pembroke, Wroth, and Lanyer (2004).

Friday, May 9th is the big day for the launch of my series of guest posts celebrating 200 years of Mansfield Park. I am absolutely delighted that Lyn Bennett is going to kick things off that day by writing about the opening paragraph of the novel. Lyn teaches in the Department of English at Dalhousie University and she’s the author of Women Writing of Divinest Things: Rhetoric and the Poetry of Pembroke, Wroth, and Lanyer (2004).

And I am very happy to tell you about all the wonderful people who’ve agreed to write for the series. In January I wrote about the first few contributors, and I’ve talked to several people since then. Here’s the full list (so far) of contributors: Elaine Bander, Deborah Barnum, Elizabeth Baxter, John Baxter, Lyn Bennett, Diana Birchall, Lorrie Clark, Jennie Duke, Natasha Duquette, Lynn Festa, Susan Allen Ford, Margaret Horwitz, Syrie James, Theresa Kenney, Ryder Kessler, Hugh Kindred, Sheila Johnson Kindred, Cheryl Kinney, Elisabeth Lenckos, Sara Malton, Juliet McMaster, Robert Miles, David Monaghan, Laurel Ann Nattress, Amy Patterson, Mary C.M. Phillips, Mary Lu Redden, Sarah M. Seltzer, Lynn Shepherd, Julie Strong, Margaret C. Sullivan, Judith Thompson, Deborah Yaffe, Juliette Wells, and Sarah Woodberry.

Here’s my plan for how things will unfold after Lyn’s first post: we’ll have one post per week until the end of the year, probably on Fridays, with extra posts around the time of Jane Austen’s birthday on December 16th. The posts will run in chronological order, and we’ll cover quite a bit of the novel, but I haven’t made any particular effort to make sure we talk about every single chapter.

Here’s my plan for how things will unfold after Lyn’s first post: we’ll have one post per week until the end of the year, probably on Fridays, with extra posts around the time of Jane Austen’s birthday on December 16th. The posts will run in chronological order, and we’ll cover quite a bit of the novel, but I haven’t made any particular effort to make sure we talk about every single chapter.

I have a question for all of you, readers and guest post contributors: what should we call the series? A party, a celebration, a book club or reading group? My goal is to host a conversation that focuses on what Jane Austen wrote, as a way of honouring Mansfield Park in its anniversary year. Do we need a snazzy title, or should I just call it something straightforward, like “200 Years of Mansfield Park”? Suggestions welcome! I’m calling on your creativity and cleverness to help me out as I organize this party/event/celebration/conversation. Remember what I did last year? “Pride and Prejudice at 200” and “The Custom of the Country at 100.” Informative, yes; dazzling, no. If you leave it with me, I’m sure to come up with a third thing that’s very dull indeed.

February 6, 2014

“The Watsons in Winter”: An Interview with Deborah Yaffe

Deborah Yaffe, author of Among the Janeites: A Journey Through the World of Jane Austen Fandom, is writing about “The Watsons in Winter” on her blog, exploring the fragment of the novel Jane Austen began when she was living in Bath, and the continuations and reworkings of the novel written by members of the Austen family and other writers. I’ve been reading her posts and I wanted to know more, so I asked if she’d answer a few questions here.

Deborah Yaffe, author of Among the Janeites: A Journey Through the World of Jane Austen Fandom, is writing about “The Watsons in Winter” on her blog, exploring the fragment of the novel Jane Austen began when she was living in Bath, and the continuations and reworkings of the novel written by members of the Austen family and other writers. I’ve been reading her posts and I wanted to know more, so I asked if she’d answer a few questions here.

Last fall, when I reviewed Among the Janeites, I hadn’t met Deborah, even though we’ve attended many of the same JASNA AGMs, and in fact we still haven’t met in person, though we’ve had email and Twitter conversations over the last few months. I’m very happy to say that she’s writing a guest post for my upcoming series celebrating 200 years of Mansfield Park.

(Deborah’s in great company – if you haven’t seen the line-up of contributors, you can read about some of them here. I’m absolutely delighted that so many clever people have said yes to my invitation. It’s going to be a wonderful conversation among people who enjoy reading Austen’s novels. Please join us when the series starts May 9th! Subscribe to the blog by email and follow me on Twitter @Sarah_Emsley for updates.)

You can read The Watsons at Molland’s, and you can find the introduction and complete list of posts for “The Watsons in Winter” on Deborah’s website.

In Among the Janeites, you focus mainly on contemporary fans of Jane Austen. For “The Watsons in Winter” you’ve gone further back in time: you write that Catherine Hubback’s 1850 novel The Younger Sister is “the first published Austen fan fiction, the founding mother of a genre whose exemplars now fill groaning shelves in bookstores everywhere.” How did you get started on your journey through the world of these earlier Austen fans – what inspired you to research the ten continuations of The Watsons that you talk about in your series?

Although I’ve read Austen’s fragments a couple of times, I’ve never known them as well as I know the completed novels. Last spring, when the creators of “The Lizzie Bennet Diaries” announced they were going to follow up with a contemporary web series based on Sanditon, I had a good excuse to go back to that unfinished novel and remember how very good it is. That inspired me to do a blog series on Sanditon continuations, which I called “Sanditon Summer.” (Seaside resort = beach = summer.) I wanted an excuse to re-read The Watsons, too! The bleakness of the book itself, plus the alliterative possibilities of the season, led me to “The Watsons in Winter.”

Although I’ve read Austen’s fragments a couple of times, I’ve never known them as well as I know the completed novels. Last spring, when the creators of “The Lizzie Bennet Diaries” announced they were going to follow up with a contemporary web series based on Sanditon, I had a good excuse to go back to that unfinished novel and remember how very good it is. That inspired me to do a blog series on Sanditon continuations, which I called “Sanditon Summer.” (Seaside resort = beach = summer.) I wanted an excuse to re-read The Watsons, too! The bleakness of the book itself, plus the alliterative possibilities of the season, led me to “The Watsons in Winter.”

There’s a saying that every translation is an interpretation, and I think every fan fiction is also an interpretation; that’s why I’m interested in Austen fan fic. Even when the books are not very good as novels, they may illuminate the many ways in which Austen can be read.

In your first post on The Watsons, you write that “In places, the fragment reads like the first romantic comedy written by Hobbes.” Tell us about the composition of The Watsons, and the speculation by Austen critics about why she abandoned the manuscript.

My understanding – and I hasten to point out that I’m not a literary scholar, just a common reader who loves Austen – is that most critics think The Watsons was written towards the end of Austen’s Bath years, perhaps around 1804. The Bath period doesn’t seem to have been a happy time in Austen’s life, which might account for the wintry quality of her story: it’s about a young woman who has been turned out of the home in which she was raised and, returning to the family she barely knows, finds she’s not really at home there, either.

The Watsons was published for the first time in the second edition of J.E. Austen-Leigh’s 1870 Memoir of his aunt, and Austen-Leigh reports a family tradition about Austen’s plans for the further development of the story. Apparently, things were going to get even worse: Emma’s clergyman father was going to die, and she and her unmarried sisters were going to find themselves dependent on their vulgar and unkind brother and sister-in-law.

The Watsons: Jane Austen’s Fragment Continued and Completed, by John Coates (1958)

And then, in 1805, Jane Austen’s clergyman father died, and she, her mother, and her unmarried sister found themselves dependent on her brothers and their wives. It was the beginning of a very unsettled and difficult time in Austen’s life, which didn’t end until the move to her brother Edward’s cottage at Chawton in 1809. (A move which, biographers have noted, occurred only after the untimely death of Edward’s wife, who does not seem to have been the president of Jane Austen’s fan club.) So critics have speculated that it was too painful for Jane Austen to keep going with a story that so eerily mirrored the circumstances of her own life. It’s a plausible speculation, although – as with so much about Austen’s life and work – we don’t really have solid evidence to confirm it.

One of the passages from The Watsons that I’ve always found memorable is the discussion between Emma Watson and her sister about which fate is worse, marrying someone you don’t like, or becoming a teacher. “Poverty is a great evil; but to a woman of education and feeling it ought not, it cannot be the greatest. I would rather be teacher at a school (and I can think of nothing worse) than marry a man I did not like,” says Emma, and her sister retorts: “I would rather do anything than be teacher at a school…. I have been at school, Emma, and know what a life they lead; you never have.” To what extent do the continuations of The Watsons by other writers pick up on this debate about things that are worse than poverty?

I think that’s a striking passage too. It reminds me of the indelible girls’ school sections in some of the great Victorian novels, like Jane Eyre or Villette or Vanity Fair. (Teacher in an early nineteenth-century school: yet another job I’m glad I didn’t have.) And doesn’t it whet your appetite for the book Jane Austen never finished? Maybe we would have seen a full working-out of this debate between Emma Watson, whose high-mindedness is tinged with naiveté, and her sister Elizabeth, who has led a tougher life and is more realistic about the choices they face. I could see Elizabeth ending up making a Charlotte Lucas-like marriage of convenience, while Emma holds out for something better.

But back to your question. One of the things I found most interesting about the Watsons continuations is the extent to which many of them sidestep the darkness and desperation that seem to me to lie at the heart of Austen’s fragment. Emma Watson has been raised by an aunt and uncle who implicitly promised they would give her a home and a dowry. Then the uncle dies, the aunt remarries, and Emma is out on her ear – no money, no prospects, a burden on her impoverished father and siblings. It’s a harsh reminder of how precarious life in Jane Austen’s world could be for a woman without money, always dependent on the easily revoked kindness of some man or other.

But several of the continuation authors find a way to dispatch the troublesome new uncle, reintroduce the loving aunt, and make Emma an heiress again. And this often happens well before the happy ending. It’s as if these writers can’t really stomach a Jane Austen who isn’t as sunny as the sunniest pages of Pride and Prejudice, so they quickly restore everyone to Happyland. To me, this seems like an evasion of Austen’s theme.

The Watsons, by Merryn Williams (2005)

But of course The Watsons isn’t all doom and gloom – there are some very funny secondary characters and a charming scene in which our heroine rescues a little boy from humiliation by dancing with him at a ball – and fan fic writers are entitled to pick the keynote they find most compelling. This goes to something that I found in researching Among the Janeites: every fan has his/her own vision of what Jane Austen is. My Austen is astringent, ethical, clear-eyed, sometimes ruthless; but many other Janeites see an Austen who is fundamentally kind, comforting, warm-hearted. I don’t think one of these visions is necessarily more correct than the other: it’s a matter of whether you focus more on the rightness of the happy ending or the darkness that lingers around the edges of the story. For me, though, it feels rather incongruous to turn The Watsons, of all books, into a cheery, reassuring tale.

How hard was it to track down copies of the continuations? I know, for example, that you weren’t able to get ahold of Volume III of The Younger Sister – can you give us an update on your efforts to find a digital copy?

I searched Google, Wikipedia, the Republic of Pemberley, WorldCat and Amazon to compile a list of all published Watsons continuations (although, given the speed with which fan fic proliferates, I can’t be absolutely certain I got them all). Once I had the list, it was quite easy to find most of them: three are available in e-book form, two were on the shelves of my local public library, two I got from a university library via interlibrary loan, and two (both self-published) I bought in hard copy online.

The Watsons Revisited: A Continuation of Austen’s The Watsons, by Eucharista Ward (2012)

Catherine Hubback’s The Younger Sister is the frustrating exception, especially since it is, in some ways, the most interesting of the lot – the first published Austen continuation, the work of a close relative, and the basis for two of the other nine Watsons reboots. As I explain in my blog, the first two of Hubback’s three volumes were digitized years ago by the Bodleian Library, and I couldn’t figure out why the third volume was nowhere to be found. (An Amazon offering purporting to be Volume III actually isn’t, according to customer reviews.) Eventually, I emailed the Bod to ask what was up, and they told me their third volume had turned out to be too fragile to scan. Meanwhile, my interlibrary loan request was rejected because the sole loanable copy – in all of the United States! – was checked out and not due back for months. I emailed the library that holds that copy, the University of Iowa, and explained a bit about the historical importance of this book and the missing digital version of Volume III. They responded promptly and very positively, saying they would recall their copy and digitize it; I’m hoping they follow through. (And meanwhile, the grad student who was counting on having it out till June is cursing my name.)

Why do you think some of the writers of these continuations either hide under a pseudonym or hide the degree of their indebtedness to Jane Austen? Edith Hubback Brown is an exception, I know. I laughed when I read the lines you quote from the preface to her novel – “I will not apologise. I like my great-aunt Jane, and she would have liked me” – and your comment on her tone: you say she writes “with an absolute certainty that will sound familiar to other Janeites equally convinced that only an accident of history prevented them from becoming Austen’s closest confidant.” (Even Brown is unclear about who wrote what. As you point out, her husband Francis Brown is credited on the title page as a collaborator, but only Edith Brown signed the dedication and preface.) Why is it so difficult to say, “Jane Austen wrote the first several pages, and I wrote the rest”?

I think only Catherine Hubback hides her indebtedness to Austen: she dedicates her book to her aunt’s memory but never mentions that the original story is Austen’s. But since The Watsons was unpublished at that point, Hubback probably saw no need or reason to advertise the connection. And she had heard the story at her Aunt Cassandra’s knee for years, almost like a fairy tale that you learn by heart. Maybe she felt that Austen’s unfinished work was communal family property. Since Jane Austen in 1850 was nothing like the international phenomenon she’s become in our time, Hubback presumably didn’t see much commercial value in advertising her book’s Austen link.

The later Watsons writers do acknowledge an Austen link – though Hubback’s two descendants tend to underplay their debt to Hubback. (One of these, Hubback’s great-great-nephew-by-marriage, David Hopkinson, is the sole pseudonym-user, as far as I know. I’d speculate that he used a pseudonym because he had published non-fiction under his own name and didn’t want to associate those books with an arguably more frivolous enterprise. But that’s just a guess.) For the people who are writing in the post-Colin-Firth, all-Jane-all-the-time world, it obviously makes strategic sense to go for the Austen market. A couple of the writers do meddle with Austen’s prose, which I think shows more chutzpah than wisdom.

Is “The Watsons in Winter” series part of a larger project?

I don’t anticipate either this series or “Sanditon in Summer” being part of a larger project – they were just fun ways to reacquaint myself with some lesser-known corners of Austen’s work. I’m looking forward to reading Marina Caño Lopez’s work on Watsons continuations when she publishes her St. Andrew’s dissertation (currently not available online, alas).

And I can’t resist asking – are you at all tempted to write your own continuation of The Watsons, or will you leave that to other pens?

Never! I would be far too intimidated to put my minor-league prose and storytelling skills up against Austen’s towering genius. These fan fic writers are much braver than I am.

Do any of you have questions for Deborah about The Watsons, or about Among the Janeites? You can read the first eight posts in “The Watsons in Winter” on her blog, and follow her on Twitter @DeborahYaffe for links to new posts.

If you missed last week’s interview with Amy Patterson of Jane Austen Books (@AustenBooks), you can find it here.

January 31, 2014

Mr. Collins, Mansfield Park, and Jane Austen for Kids: An Interview with Amy Patterson

Amy Patterson runs the fantastic bookstore Jane Austen Books, along with her mother Jennifer Weinbrecht and her sister Beth Dean, and she blogs about Jane Austen at amylpatterson.wordpress.com. She’s writing a guest post on Fanny Price in Portsmouth for my series celebrating 200 years of Mansfield Park. The most recent Jane Austen Books Catalog features Austen-related books for children – and if you’ve been reading my blog recently you know I’m very interested in this topic – so I asked Amy if she’d be willing to answer a few questions about Jane Austen for kids and about her own interest in Austen.

Jane Austen Books at the JASNA 2013 AGM, from left to right: Amy Romero, Beth Dean, and Amy Patterson’s “giant selfie head” (her words, not mine!)

When did you discover Jane Austen’s books? Did you love them right away, or did that develop over time?

Her books were discovered for me! My mother became a fan in her early teen years, and wanted to pass her love for Austen’s writing on to her daughters. She read us many books when we were young, including most of the classics by authors like Twain, Alcott, and Tolkien. But something about P&P stuck with me when she started reading it to us. I would have been somewhere between four and six years old. She did all of the voices, and she used context and vocal cues to sort of flesh the basic story out of Austen’s complex narrative. I think what stuck the most for me was Elizabeth’s way of speaking up for herself. Even as a young

Her books were discovered for me! My mother became a fan in her early teen years, and wanted to pass her love for Austen’s writing on to her daughters. She read us many books when we were young, including most of the classics by authors like Twain, Alcott, and Tolkien. But something about P&P stuck with me when she started reading it to us. I would have been somewhere between four and six years old. She did all of the voices, and she used context and vocal cues to sort of flesh the basic story out of Austen’s complex narrative. I think what stuck the most for me was Elizabeth’s way of speaking up for herself. Even as a young  child I admired the fact that she was strong, and she became as “cool” for me as Galadriel and Princess Leia. I can’t remember a time in my life that I didn’t love at least P&P, and as I grew up and read the rest of her novels they became favorites as well. She has always been a part of my life, and even as young girls my sister and mother and I shared a special Austen “language.” On our trips to the art museum we would pick out which portraits looked like our favorite characters, and Beth and I vigorously applied ourselves to whatever sonatinas we could get our little fingers on.

child I admired the fact that she was strong, and she became as “cool” for me as Galadriel and Princess Leia. I can’t remember a time in my life that I didn’t love at least P&P, and as I grew up and read the rest of her novels they became favorites as well. She has always been a part of my life, and even as young girls my sister and mother and I shared a special Austen “language.” On our trips to the art museum we would pick out which portraits looked like our favorite characters, and Beth and I vigorously applied ourselves to whatever sonatinas we could get our little fingers on.

Is anyone ever too young to read Jane Austen? What do you think of the many adaptations of Austen novels designed for young readers, including the recent appearance of Austen-inspired board books for babies and toddlers?

I think it’s quite possible for a child to be too young for Austen. We had already had some experience with “chapter books” by the time we had P&P read aloud to us, so we were pretty experienced at listening for the important bits of action and dialogue. Being able to distinguish between background information and important action is a very important skill for children to develop at an early age. And practicing on Austen is (in my opinion) essential, because her cues are so much more subtle than, say, Dickens or Tolkien. You really have to understand what people want – Mrs. Bennet wants her daughters married, Mr. Collins wants a wife, etc. – to be able to pick out the critical moments in the story, because they’re not spelled out in huge battle scenes or violent arguments.

I think the board books are a cute idea for the precocious Austen completist. I don’t know that they should or could replace knowing the full story, but they’re not intended to. In my opinion, they’re valuable for introducing a sense of setting and tone of the novels. The Wang board book [Cozy Classics: Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice], for example, shows the characters in Regency costume and some of the rooms in Regency décor. And the Adams board book [Little Miss Austen: Pride and Prejudice] conveys some information about the class differences between Darcy and Elizabeth.

I think the board books are a cute idea for the precocious Austen completist. I don’t know that they should or could replace knowing the full story, but they’re not intended to. In my opinion, they’re valuable for introducing a sense of setting and tone of the novels. The Wang board book [Cozy Classics: Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice], for example, shows the characters in Regency costume and some of the rooms in Regency décor. And the Adams board book [Little Miss Austen: Pride and Prejudice] conveys some information about the class differences between Darcy and Elizabeth.

I’m less comfortable with the YA/teen adaptations of her novels, even though most of the ones we’ve come across have been very well done. I suppose I feel that if a child is old enough to understand the words on the page, or at least knows how to look up the ones he doesn’t understand, then there shouldn’t be much of a reason not to read the originals, even if it means supplementing them with watching a film version, or watching the film first. And I don’t think her novels can be “ruined” by the film adaptations, simply because each of them has left out so much that there is still endless treasure to be found in the words on the page.

I’m less comfortable with the YA/teen adaptations of her novels, even though most of the ones we’ve come across have been very well done. I suppose I feel that if a child is old enough to understand the words on the page, or at least knows how to look up the ones he doesn’t understand, then there shouldn’t be much of a reason not to read the originals, even if it means supplementing them with watching a film version, or watching the film first. And I don’t think her novels can be “ruined” by the film adaptations, simply because each of them has left out so much that there is still endless treasure to be found in the words on the page.

My own sons are three and five, and although they answer their toy phones “Jane Austen Books, can I help you?” they don’t yet know more about her than that she was a lady who lived a long time ago and wrote books that mommy loves and grandma has in her house. Colin (my oldest) has had a few Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth stories, but we’re still just getting started with big books. I will probably get them through Roald Dahl before I jump to Jane!

I know the answer to the question, “who’s your favourite Mr. Darcy on film?” (David Rintoul – Amy wrote about the actors who’ve played Darcy in the January/February 2013 issue of Jane Austen’s Regency World Magazine.) But I also know that you’re interested in Mr. Collins and the way Austen describes his upbringing and behaviour in Pride and Prejudice. (See Amy’s blog post “Do You Take this Man? Part II.”) Which of the actors who’ve played Mr. Collins on screen does the best job of getting at his character as Austen wrote it?

I think there have been a lot of near misses for Mr. Collins. But the 1995 Mr. Collins, played by David Bamber, is actually quite a wide miss. He is far too creepy, and is obviously the inspiration for the extremely creepy Mr. Collins in the Lost in Austen series. But the 1980 Mr. Collins goes a little too far the other way – he’s not quite mercenary enough. (Or perhaps his goofy theme song disarms us too much?) I think the 2005 Collins was surprisingly better than I expected, but it’s overall such a poor adaptation that I may have simply been cheering for the one thing that was close to correct.

Mr. Kohli, in Bride and Prejudice

Honestly, I like Mr. Kohli in Bride and Prejudice quite a bit. He’s embarrassingly enthusiastic and just barely pleasant enough to spend the mandatory five minutes with every morning before retiring to one’s rear-facing sitting room. But he’s also repulsively greedy enough, without crossing the line too far into simply personally repulsive, that it’s easy to see why Elizabeth (or in this case Lalita) is so turned off by him.

You were at last year’s JASNA AGM in Minneapolis with Jane Austen Books, celebrating 200 years of Pride and Prejudice. What were some of the highlights of the AGM for you?

For me, the highlight of the 2013 AGM was John Mullan’s talk on silences in Austen’s novels. As someone who developed a complex vocabulary very early in life, and someone who also has a bit of an OCD nature, I felt like he was inside my head, or perhaps that he had stolen my marked up copy of Emma and read all the crazy things I’ve written in the margins. It was a highlight because it also reinforced the idea that there is always something new to discuss regarding Austen’s books.

For me, the highlight of the 2013 AGM was John Mullan’s talk on silences in Austen’s novels. As someone who developed a complex vocabulary very early in life, and someone who also has a bit of an OCD nature, I felt like he was inside my head, or perhaps that he had stolen my marked up copy of Emma and read all the crazy things I’ve written in the margins. It was a highlight because it also reinforced the idea that there is always something new to discuss regarding Austen’s books.

How are you planning to celebrate 200 years of Mansfield Park in 2014? Will you celebrate with your kids? I haven’t yet seen a Mansfield Park board book – do you know if there are any in the works?

I will be re-reading MP, which isn’t really a celebration, because I read each novel at least once or twice a year. My boys have already attended a few balls at our local JASNA meetings and at AGMs, and they really enjoy them, so I may take them down to the Jane Austen Festival in Louisville this year.

I will be re-reading MP, which isn’t really a celebration, because I read each novel at least once or twice a year. My boys have already attended a few balls at our local JASNA meetings and at AGMs, and they really enjoy them, so I may take them down to the Jane Austen Festival in Louisville this year.

I have not seen any MP board books, but as it’s (un)fairly unpopular with adult readers I’d imagine children’s authors would start with the more popular titles. We already have P&P and S&S, and I’m betting the next will be Persuasion. After all, nothing is more exciting to kids than a good old-fashioned head injury.

We are also making plans for the 2014 AGM in Montreal. We have already spoken to a customs agent about the border crossing, and my sister is studying the cash register manual so that we can set it up to take two forms of currency. We generally start planning several months ahead of time, but this will be our first time across the border as the owners of Jane Austen Books, and we don’t want to make any mistakes!

Celebrating Mansfield Park in 2014: Amy says, “Our advertisement in the Jan/Feb issue of Jane Austen’s Regency World Magazine is an MP joke.”

My very first AGM was the 2006 Tucson AGM, before we had the bookstore, and its theme was Mansfield Park as well. To use a cliché, I thought I’d died and gone to heaven! A whole session on Henry’s black heart! As hard as it is to pick a favorite of Austen’s novels, MP is tied with Emma at the very top of my list of books that keep me coming back. There are just so many details, subplots, and esoteric references. It’s not a book you can ever put down and feel as if you’ve seen the whole picture, and that’s incredibly satisfying for those of us who need more than one plot at a time in our novels.

Thanks, Amy! I’m happy to have found one more person who lists Mansfield Park as a favourite, and I’m looking forward to celebrating with you and our JASNA friends in Montreal in October.

Since I first asked you about Mansfield Park board books, I’ve learned from Cozy Classics, via Twitter, that all of Austen’s novels are on their to do list, so someday we’ll be able to read the twelve-word version of MP. I wonder which twelve words they’ll choose….

Do any of you have things you’d like to ask Amy, dear readers? She’s kindly agreed to answer your questions here as well.

January 29, 2014

Mr. Darcy and L.M. Montgomery

Two of my blog posts have recently been reprinted on The Literary Ladies’ Guide to the Writing Life. One of them is “Why is Mr. Darcy So Attractive?” – which is the second most popular post ever on my blog. (Second only to “Jane Austen’s ‘Darling Child’ Meets the World,” which I mentioned in yesterday’s post. Yes, Pride and Prejudice gets a great deal of attention, and that attention is well deserved! But this year we’re also going to give Mansfield Park its share of attention, too – right? Right?? I hope you’re all with me on this!)

Here’s the beginning of my Mr. Darcy post:

“Darcy is still the ultimate sex symbol” is the title of a recent article by Katy Brand in The Telegraph. The article features a photograph of Colin Firth and his famous wet shirt from the 1995 A&E/BBC Pride and Prejudice series. I can’t reproduce the image here, because I’ve promised to try very hard not to talk about the “white noise” of popular culture that surrounds Pride and Prejudice. … Read more at The Literary Ladies’ Guide to the Writing Life.

“Darcy is still the ultimate sex symbol” is the title of a recent article by Katy Brand in The Telegraph. The article features a photograph of Colin Firth and his famous wet shirt from the 1995 A&E/BBC Pride and Prejudice series. I can’t reproduce the image here, because I’ve promised to try very hard not to talk about the “white noise” of popular culture that surrounds Pride and Prejudice. … Read more at The Literary Ladies’ Guide to the Writing Life.

The second is “L.M. Montgomery’s Literary Pilgrimage to Concord, Mass.,” which I posted last fall on Montgomery’s birthday:

Given how many fans of L.M. Montgomery visit “Green Gables” in Cavendish, PEI each year, I find it fascinating to read about Montgomery’s own literary pilgrimage to Concord, Massachusetts, when she was visiting her publisher, L.C. Page, in Boston in November of 1910.

Given how many fans of L.M. Montgomery visit “Green Gables” in Cavendish, PEI each year, I find it fascinating to read about Montgomery’s own literary pilgrimage to Concord, Massachusetts, when she was visiting her publisher, L.C. Page, in Boston in November of 1910.

“Concord is the only place I saw when I was away where I would like to live,” she writes. “It is a most charming spot and I shall never forget the delightful drive we had around it.” … Read more at The Literary Ladies’ Guide to the Writing Life.

Many thanks to Nava Atlas for sharing these posts on her Literary Ladies blog.

January 28, 2014

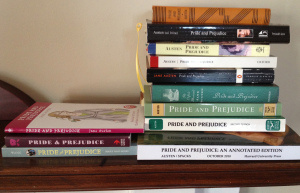

201 Years of Pride and Prejudice

JASNA Nova Scotia members are meeting on Sunday, February 23rd in Halifax to discuss essays published in the most recent issue of Persuasions On-Line, which includes conference papers on Pride and Prejudice from the 2013 AGM in Minneapolis. The celebrations for Mansfield Park have begun, and the celebrations for Pride and Prejudice aren’t over yet!

Our plan is for each person to choose an essay to focus on. We’ll take turns giving a brief overview (maximum 5 minutes each) of the essays we’ve chosen, with discussion to follow. Sheila and Hugh Kindred are hosting the event. Please let them know if you’re able to attend, and which essay you’d like to talk about. (Or leave a comment here, and I’ll pass on the information to them, and directions to you, as needed.)

Today, January 28th, marks the 201st anniversary of the day Pride and Prejudice was published. Here’s what I wrote last year to celebrate the 200th anniversary, in my post “Jane Austen’s ‘Darling Child’ Meets the World”:

Jane Austen didn’t like the way her mother read Pride and Prejudice aloud. Mrs. Austen read too quickly, “—& tho’ she perfectly understands the Characters herself, she cannot speak as they ought” (Letters, 4 February 1813). Jane writes to her sister Cassandra that she’s grateful for Cassandra’s praise of the novel because she has been having “some fits of disgust” recently. She is at home in Chawton without Cassandra, keeping the secret of her authorship from her neighbours and enduring the irritation of listening to her mother’s interpretation of her characters. She can’t control what other people do with the language of her characters, and she can’t control the errors in the printing: “The greatest blunder in the Printing that I have met with is in page 220—Vol. 3. where two speeches are made into one.” She’s just written one of the greatest books in English literature, and she must know she’s accomplished something very important, but the fact that the book is now out in the world being judged and interpreted by others is making her restless.

Click here to read the rest of “Jane Austen’s ‘Darling Child’ Meets the World.” (This piece was, and still is, the most popular post on my blog.) And here’s the link to the series of blog posts I wrote after that one, about the experience of rereading Pride and Prejudice. Happy 201st anniversary to Austen’s darling child!

January 24, 2014

Edith Wharton’s Passion for Order

It was Helen Pinkerton who introduced me to Edith Wharton, and in honour of Wharton’s birthday today I’d like to share with you one of my favourite poems, Helen’s meditation “On Gari Melchers’s ‘Writing’ (1905) in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art,” which makes reference to Wharton and her passion for order in art and architecture.

The poem is part of a series called “Bright Fictions,” poems on works of art, and it appears in Helen’s 2002 collection Taken in Faith: Poems. It’s reproduced here by permission. I hope you’ll be inspired to read the other poems in the collection as well. You can see the Gari Melchers painting at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art website, and on my Edith Wharton board on Pinterest.

On Gari Melchers’s ‘Writing’ (1905) in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

By Helen Pinkerton

The house was quiet and the world was calm. - Wallace Stevens

How often did she make such quiet, one wonders,

This woman writing at a covered table—

Full summer light warming the roseate hues,

Mauve, red, and pink of dress and cloth and room.

A Wedgwood pier glass shows three Roman figures

In ritual dance—cool neoclassic Graces—

Beside a clay pot of geraniums.

Her taste eclectic—like our modern lives—

Loving the past but settled in the living,

She seems meticulous—even, perhaps,

Like Edith Wharton, passionate for order,

Feeling, as she did, that in house and novel,

“Order, the beauty even of Beauty is.”

Stevens, though you sought order in the sea

And grander heavens, the threat of nothingness

Unmanned you. Most women have no time for such,

For fate constrains them to immediate means,

The quiet art of keeping calm the house.

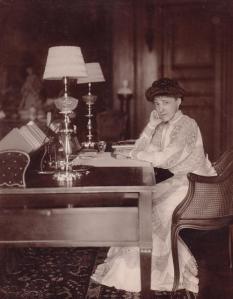

Edith Wharton in 1905

I love the image of Wharton as the woman in the painting, writing in the quiet house, in the calm world, keeping life in order by writing. There’s a clear visual parallel between the Melchers painting and the 1905 publicity photo of Wharton at her desk at The Mount, taken in the year she published her best-selling novel The House of Mirth, which happens to be the same year as the Melchers painting. Yet while Wharton sometimes posed for photographs at her desk, the real work of her writing life happened as she wrote in bed each morning. I wonder what that would have looked like, either in a photograph or a painting.

Irene Goldman-Price describes the scene in her introduction to My Dear Governess: The Letters of Edith Wharton to Anna Bahlmann: “Most mornings Wharton would remain in bed with a light breakfast and a small dog or two beside her, writing, on blue stationery, long stories and short about the characters who inhabited her mind. Anna Bahlmann collected these pages—or was handed them by Wharton’s maid—and saw to it that they became manuscripts. Only glimpses of this work appear in Wharton’s letters.”

The curator’s notes for “Writing” say that Melchers’s wife Corinne often posed as his model, and that the painting is set in Holland, in Schuylenburg, the former home of the American painter George Hitchcock. I wonder what Mrs. Melchers is writing? Probably a letter; probably not a novel. The house is quiet and the world is calm. The summer light shines on the red geraniums, the red cloth-covered writing table, the woman’s white dress. Like Eleanor Tilney in Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey, who “always wears white” (Chapter 12), this writing woman wears a colour that signals to the reader she can afford to wear a dress that’s unlikely to get dirty. She has money, comfort, a beautiful room, and the luxury of time to write on a summer afternoon. It’s likely that she has enough money to hire other women to help her keep her house calm. Does she have enough time to contemplate existential questions about the sea and the heavens? Maybe not. As Helen asks in the first line of her poem, “How often did she make such quiet”?

Patrick Kurp comments on the “revisionist reading of Stevens”—“the threat of nothingness / Unmanned you”—and says it makes him laugh: “There is an overdramatized quality to some of Stevens’ angst, all that ‘poetry is god’ business.” There’s no threat of nothingness in “Writing”: the scene is comfortable, even cosy, with its warm colours, its bright light, the cheerful geraniums in the clay pot. And yet, it’s impossible to know what the woman is writing. Just because the scene is beautiful doesn’t mean that the writing is calm or quiet. She could be, like Wharton, writing about the despair of Lily Bart in The House of Mirth, or the agony of Ralph Marvell in The Custom of the Country.

The line “Order the beauty even of beauty is” comes from “The Vision,” by the 17th century poet Thomas Traherne, and Wharton chose it as the epigraph to her book The Writing of Fiction (1924)—although for some reason, the epigraph is omitted from the 1997 Touchstone edition that I keep by my own writing desk. Wharton was intensely interested in the well-ordered, well-organized life. As Melanie Dawson writes in a chapter on “Biography” in Edith Wharton in Context (2012), edited by Laura Rattray, Wharton’s “passions for gardening, decorating, and traveling were formidable and served as outlets for her energies when she was not writing. As with her compositions, these projects demanded long-term commitments and a broad, comprehensive vision, or the exercise of what she described [in her autobiography, A Backward Glance] as her ‘irresistible tendency to improve and organize.’”

The line “Order the beauty even of beauty is” comes from “The Vision,” by the 17th century poet Thomas Traherne, and Wharton chose it as the epigraph to her book The Writing of Fiction (1924)—although for some reason, the epigraph is omitted from the 1997 Touchstone edition that I keep by my own writing desk. Wharton was intensely interested in the well-ordered, well-organized life. As Melanie Dawson writes in a chapter on “Biography” in Edith Wharton in Context (2012), edited by Laura Rattray, Wharton’s “passions for gardening, decorating, and traveling were formidable and served as outlets for her energies when she was not writing. As with her compositions, these projects demanded long-term commitments and a broad, comprehensive vision, or the exercise of what she described [in her autobiography, A Backward Glance] as her ‘irresistible tendency to improve and organize.’”

For further reading:

Edith Wharton in Context, ed. Laura Rattray (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

My Dear Governess: The Letters of Edith Wharton to Anna Bahlmann, edited by Irene Goldman-Price (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012).

Taken in Faith: Poems, by Helen Pinkerton (Athens, OH: Swallow Press, 2002).

Related posts:

On writing with “dogged obstinacy”: Edith Wharton’s 151st birthday, 2013

“Satisfied! What a beggary state! Who would be satisfied with being satisfied?” Edith Wharton’s 150th birthday, 2012

Helen Pinkerton introduced me to Edith Wharton and The Custom of the Country

January 22, 2014

“At Home with the Georgians” and JASNA Nova Scotia

The next meeting of JASNA Nova Scotia is this Sunday, January 26th, and members are gathering to watch “At Home with the Georgians” (2010), presented by Amanda Vickery and based on her book Behind Closed Doors: At Home in Georgian England (Yale University Press, 2009).

The next meeting of JASNA Nova Scotia is this Sunday, January 26th, and members are gathering to watch “At Home with the Georgians” (2010), presented by Amanda Vickery and based on her book Behind Closed Doors: At Home in Georgian England (Yale University Press, 2009).

“Amanda Vickery is a naughty, clever, humourous eavesdropper on the past… She has the Georgians in her sights like no one since Jane Austen.” – Sunday Telegraph

The meeting is at 2pm in Halifax, and if you’re interested in attending, please let our Regional Coordinator, Anne Thompson, know, and she can give you details and directions. (Or you can leave a comment here.)

Reviews of “At Home with the Georgians” from The Guardian, The Telegraph, Austenonly, and Jane Austen’s World.