Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 30

December 16, 2014

“Never had Fanny more wanted a cordial”: Comic Relief and Word Choice in Mansfield Park

Thirty-fourth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Today is Jane Austen’s birthday! How are you celebrating? I celebrated on December 7th at a birthday lunch with JASNA Nova Scotia, and this past weekend, I visited the fabulous new Halifax Central Library to look for books by and about Jane Austen. To celebrate my own birthday back in September, I made a donation to the library’s “Share the Wow” fundraising campaign, so they sent me some bookplates and invited me to place them in books from their collection. (For $25, you, too, could put your name in one of their books.)

The library, which CNN named “One of 10 eye-popping new buildings that you’ll see in 2014,” opened on Saturday (read more about opening day here), and it’s a fantastic present for the city of Halifax.

I was lucky to see inside the Halifax Central Library a couple of months before it opened

Of course I went back to our new library on opening day

Today, I’m excited to be celebrating Austen’s birthday by sharing this guest post by Karen Doornebos with you. Karen and I invite you to raise a glass in honour of both Jane Austen and Fanny Price.

To Jane Austen!

Karen Doornebos is the author of Undressing Mr. Darcy, published by Penguin, Random House. Her first novel, Definitely Not Mr. Darcy, has been published in three countries and was granted a starred review by Publishers Weekly. Both books are very clever and very funny. I really like the moment in Definitely Not Mr. Darcy when the heroine realizes that “Regency life was grim for women, very grim, and this, too, had been one of Austen’s messages, just not the one Chloe had wanted to acknowledge.”

And there are several highly entertaining cameo appearances in Undressing Mr. Darcy, including one by Cornel West, who gives a lecture on Jane Austen and power at a JASNA AGM, just as he did at the 2012 JASNA AGM in New York. (You can listen to the lecture here. It was one of the best AGM talks I’ve ever heard – he says that “Philosophers tend to be obsessed with the theory of flames, but Jane Austen is the fire” – and I can see why Karen was inspired to include it in her novel.)

Karen lived and worked in London for a short time, but she tells me she’s now happy “just being a lifelong member of the Jane Austen Society of North America and living in the Chicagoland area with [her] husband, two teenagers, and various pets—including a bird.” “Speaking of birds,” she says, you can follow her on Twitter and Facebook . She hopes to see you there and on her website, www.karendoornebos.com .

Dear Fanny—

You know our present wretchedness. May God support you under your share! We have been here two days, but there is nothing to be done. They cannot be traced. You may not have heard of the last blow—Julia’s elopement; she is gone to Scotland with Yates. At any other time, this would have been felt dreadfully. Now it seems nothing; yet it is an heavy aggravation. My father is not overpowered. More cannot be hoped. He is still able to think and act; and I write, by his desire, to propose your returning home. He is anxious to get you there for my mother’s sake. I shall be at Portsmouth the morning after you receive this, and hope to find you ready to set off for Mansfield. My father wishes you to invite Susan to go with you, for a few months. Settle it as you like; say what is proper; I am sure you will feel such an instance of his kindness at such a moment! Do justice to his meaning, however I may confuse it. You may imagine something of my present state. There is no end of the evil let loose upon us. You will see me early, by the mail.

Yours, &c.

Never had Fanny more wanted a cordial. Never had she felt such a one as this letter contained. Tomorrow! To leave Portsmouth tomorrow! She was, she felt she was, in the greatest danger of being exquisitely happy, while so many were miserable. The evil which brought such good to her! She dreaded lest she should learn to be insensible of it. To be going so soon, sent for so kindly, sent for as a comfort, and with leave to take Susan, was altogether such a combination of blessings as set her heart in a glow, and for a time, seemed to distance every pain, and make her incapable of suitably sharing the distress even of those whose distress she thought of most.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 46 (New York: Barnes & Noble, 2012)

Comic relief. That’s why many of us, at least, laugh at the line: “Never had Fanny more wanted a cordial.”

As in all great comedy, timing is almost everything—delivery is the rest. Here the timing is impeccable and the delivery both deadpan and swift. But, more than merely slaking our thirst for comic relief after this especially torturous part of the novel (namely Fanny’s three months in Portsmouth), the line brings us relief and a medicinal in every sense of the word. More importantly, it offers us a glimpse into the power of Jane Austen’s word choice and how deftly she moves us from pathos to punchline.

The first, most obvious, and striking thing about the line is the incongruous image of Fanny, of all characters in Mansfield Park, holding a cordial. It seems out of character, though we are told early on Fanny does drink. She drinks diluted wine that (of course none other than) Edmund mixes for her (Chapter 7). So to visualize her with a drink doesn’t shock us, really. What jolts us is a direct statement putting the words “Fanny” and “want” in the same sentence and so near the end of the novel, when—up to this late hour—neither Fanny nor the narrator has referred to Fanny overtly wanting anything. And what does she want? A drink! A medicinal drink, perhaps—but still.

Up until this moment, Fanny has suppressed her wants and needs to such an extreme that in Portsmouth she has not articulated her desire to go back to Mansfield, and at Mansfield, she managed to survive without a fire in her room, without a true family or home to call her own and without any reciprocation from the man she has so deeply loved her entire life.

And this is what she wants? This is all she wants? A cordial? A restorative? As readers we have to laugh. Austen intended us to laugh here. It’s a perfect pay-off to pages and pages of dingy, dirty, and depressing detainment in Portsmouth. After three months of penance, Fanny and the reader get a real break—a cordial.

Interesting and worth noting too, is Austen’s choice of the word “cordial.” She did not, as she did in other novels, specify a drink such as the Constantia wine that Mrs. Jennings brings to Marianne after learning of Willoughby’s engagement. She did not use the (expensive) “French wine” she associated with Mr. Darcy, and neither did she choose the “Madeira and water” Emma suggests that Frank Churchill should drink at the Box Hill picnic.

Austen opted for “cordial,” a very deliberate choice.

This single word, with so many meanings to unpack, strikes, dare I say, a chord. Derived from the Latin and French, “cordial,” according to the Oxford English Dictionary, “appears in its origin a word of medicine.”

This makes so much sense, considering Fanny throughout the novel is known to be on the weak side, and in need of exercise to keep up some semblance of fortitude and health.

Equally appropriate is the French “coeur” at the—(forgive me) heart of—“cordial.” The first meaning listed in the OED for cordial is: “of or belonging to the heart.”

What a wonderful word to choose to describe this crucial and long-awaited letter from Fanny’s beloved Edmund, announcing her liberation from Portsmouth and his coming to rescue her from it.

The second listed meaning in the OED is: “of medicine, food, or beverage: stimulating, comforting, or invigorating the heart; restorative, reviving, cheering.” It goes on to mention “as in cordial water.” Indeed, Edmund’s letter does serve as a restorative—it restores Fanny back to her life at Mansfield. Ah, that sly Austen!

The third meaning of cordial: “Hearty: coming from the heart, sincere, genuine, warm, warm and hearty as a course of action or on behalf of a cause.”

Yet, beyond the myriad of nuances behind the word cordial, something else is at work in these few lines. What may also have been intentional on Austen’s part is that we (especially with our modern sensibilities), feel a twinge of excitement at the possibility of our heroine finally getting in touch with her desires, and perhaps growing and changing as we often want our heroines to do.

Fanny has expressed a desire! Could she possibly … become a strong-willed Elizabeth Bennet?

Austen quashes these hopes in the next sentence. Fanny, rather than following up on her wish for a cordial in the literal sense, and helping herself to Mr. Price’s no doubt potent and ample liquor cabinet to pour herself a stiff one (or even ringing for Rebecca to fetch her a medicinal), placates herself with the idea that the letter itself provides all the cordial she needs:

“Never had she felt such a one [cordial] as this letter contained.”

And, yes, yes it is a cordial in and of itself, but how about that drink, Fanny?

In true Fanny fashion, she denies herself her drink, and, worse, denies herself even a moment of happiness to celebrate that she is sprung from the Portsmouth prison. Once again, Austen gives us cause to smile, when in the very same sentence, she artfully pairs the words “danger” and “happy”:

“She was, she felt she was, in the greatest danger of being exquisitely happy, while so many were miserable.”

Catholic and Jewish guilt have nothing on Fanny Price! It would be dangerous indeed for her to be happy—especially “exquisitely” happy.

“There! – much good may such fine relations do you.” Illustration by C.E. Brock. (http://www.mollands.net/etexts/mansfieldpark/mpillus.html)

Austen follows this up with: “The evil which brought such good to her!” Yes, we admire Fanny for not popping champagne corks when her Mansfield Park “family” has suffered so much, but…. In this sixth sentence of the paragraph, Austen again chooses the word “evil,” and we have to laugh a little at Fanny’s overstatement of the problem, do we not? As if the plague or devil’s curse were upon them? “The evil” refers of course to the Crawfords (and Julia’s elopement), but when aligned with the “good” it brought Fanny, we detect Austen smirking somewhere behind Fanny’s hyperboles.

These subtleties are what make Mansfield Park so rich for controversy and contention. Neither the narrator nor Austen herself can be nailed down. Yet, few can argue against Austen’s more obviously humorous passages and the hilarious traits she gives to some of her characters. Lady Bertram’s ennui, Mary Crawford’s wit, and less memorable, but equally shining moments that nod to Austen’s command of humor. Who else but Austen could successfully end Chapter 33, a chapter devoted to our heroine’s success at a ball, with Lady Bertram doling out a reward to Fanny.

“And I will tell you what, Fanny—which is more than I did for Maria—the next time Pug has a litter you shall have a puppy.”

We get a rollicking laugh out of this, but it’s no surprise that Fanny never gets her puppy. Smile upon smile—Lady Bertram is so indolent she hasn’t even named her own pug dog.

As we all know, but may not always have top of mind, this layering effect of Austen’s writing is what makes her a joy to read and reread.

One of the most humorous passages that’s often overlooked is the passage in Chapter 38 devoted to the coveted “silver knife” that Betsey and Susan squabble over. Mrs. Price’s botched involvement only ratchets up the humor by mirroring her equally inept sister in the parenting department. Yet, the humor here with the silver knife is, as is so often the case in Mansfield Park, I have to say—tarnished—with sadness. It’s funny but tragic that the two sisters fight over a knife. They clearly have no other, more suitable object for two young girls to fight over, and, worse, Susan inherited the knife from their dead sister Mary.

Austen’s gift for humorous description, and her tremendous powers of observation arise again and again throughout Mansfield Park, but take a careful look at the following paragraph that helps set us up for the much-needed relief that comes with the “cordial” letter from Edmund announcing he will be there to whisk Fanny and Susan away to Mansfield Park. These paragraphs also set us up for the comic relief of the cordial line. Austen does a phenomenal, and I would argue, darkly humorous, job of description here that makes Fanny’s liberation even sweeter. Austen, efficiently and seemingly effortlessly, describes the Price home for the final time through Fanny’s eyes:

“She [Fanny] sat in a blaze of oppressive heat, in a cloud of moving dust; and her eyes could only wander from the walls, marked by her father’s head, to the table cut and notched by her brothers, where stood the tea-board never thoroughly cleaned, the cups and saucers wiped in streaks, the milk a mixture of motes floating in thin blue, and the bread and butter growing every minute more greasy than even Rebecca’s hands had first produced it….”

Talk about layering! This paragraph is funny, but ugh, so perfectly revolting! Here’s to Austen’s sense of humor and her ever-so-thoughtful word choice in Mansfield Park and every novel she wrote. Let’s ring for a cordial.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Lynn Shepherd, Elisabeth Lenckos, and Sheryl Craig. This week, in honour of Jane Austen’s birthday, there’s one post per day.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

December 15, 2014

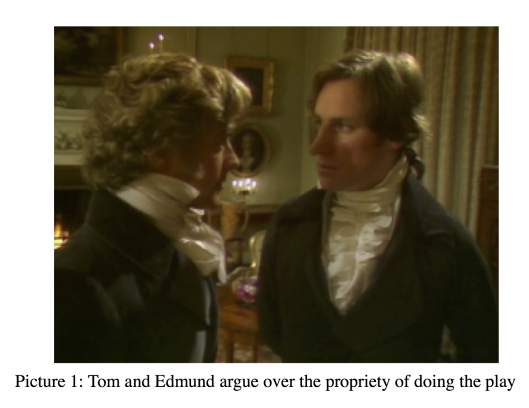

Why Tom Bertram Cannot Die

Thirty-third in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Tomorrow is Jane Austen’s birthday, and I’m celebrating all week long with guest posts on Mansfield Park every day. Please check back tomorrow when Karen Doornebos raises a glass to toast Jane Austen on her 239th birthday.

Today’s post is by Theresa Kenney. A member of JASNA and an Associate Professor of English at the University of Dallas, Theresa has written several essays for Persuasions. She has also published essays on Dante, Donne, Southwell, and Dickens. She edited and translated “Women Are Not Human”: An Anonymous Treatise and Responses, and co-edited and contributed to The Christ Child in Medieval Culture: Alpha es et O! At Stanford, her dissertation research focused on Medieval and Renaissance nativity lyrics, but she has frequently taught the 19th century novel, Early Modern literature, and Arthurian romance. Always missing her native Pennsylvania, she tells me, she and her Irish husband live in Texas with their two daughters – “and make frequent trips to cooler climes.”

Today’s post is by Theresa Kenney. A member of JASNA and an Associate Professor of English at the University of Dallas, Theresa has written several essays for Persuasions. She has also published essays on Dante, Donne, Southwell, and Dickens. She edited and translated “Women Are Not Human”: An Anonymous Treatise and Responses, and co-edited and contributed to The Christ Child in Medieval Culture: Alpha es et O! At Stanford, her dissertation research focused on Medieval and Renaissance nativity lyrics, but she has frequently taught the 19th century novel, Early Modern literature, and Arthurian romance. Always missing her native Pennsylvania, she tells me, she and her Irish husband live in Texas with their two daughters – “and make frequent trips to cooler climes.”

Theresa and I first met at the 2006 JASNA AGM in Tucson, one of my favourite AGMs because it focused on – what else! – Mansfield Park. (And because it was in Arizona, so I got to visit with some relatives who are very dear to me.) It’s a pleasure to introduce her guest post on “Why Tom Bertram Cannot Die,” and, before we get to that topic, to share with you her account of how she discovered Jane Austen.

I came late to Austen! While the regular 10th grade classes were reading Pride and Prejudice, the advanced placement students were afflicted with Malamud and Faulkner; if it hadn’t been for a heavy dose of Shakespeare and metaphysical poets that year, I would never have liked English at all. I was fully intending to major in Italian and Classics as a freshman at Penn State when my best friends, Nan Runde and her husband Joe, who were grad students and had sung in the church choir with me, steered me toward the English major, though I did double major in Classics. Some time later, these same friends influenced the course of my life again when they insisted that I read Pride and Prejudice while I was visiting them shortly after they had graduated and moved to Connecticut.

I came late to Austen! While the regular 10th grade classes were reading Pride and Prejudice, the advanced placement students were afflicted with Malamud and Faulkner; if it hadn’t been for a heavy dose of Shakespeare and metaphysical poets that year, I would never have liked English at all. I was fully intending to major in Italian and Classics as a freshman at Penn State when my best friends, Nan Runde and her husband Joe, who were grad students and had sung in the church choir with me, steered me toward the English major, though I did double major in Classics. Some time later, these same friends influenced the course of my life again when they insisted that I read Pride and Prejudice while I was visiting them shortly after they had graduated and moved to Connecticut.

I remember nothing about my reaction to the opening chapters, or even to Mr. Darcy, but when Mr. Wickham told Elizabeth that he had a warm, unguarded temperament I could not stop laughing. Every time I remembered that passage, I laughed. From then on I was in love, in love with Austen’s bad characters and their self-congratulatory way of speaking. It must have been 1980, the same year that the wonderful televised version with Elizabeth Garvie and David Rintoul came on, and my sisters and I lived for each episode. Elizabeth Bennet displaced Shakespeare’s Rosalind and Beatrice as my favorite female character in literature. I then tried reading Emma, but I disliked Mr. Knightley and his preachiness, and I could not figure out what Emma saw in him. Silly me! Now he is my favorite Austen hero.

I also liked Edmund Bertram more than your average Austenite even when I first read Mansfield Park some years later, and that takes some explaining. Edmund is no one’s favorite Austen hero, largely because he spends most of the novel in love with the wrong girl (if you like Fanny) or the right girl whom he does not deserve (if you like Mary Crawford). But I always like to be directed by Jane Austen on these matters, and she has chosen him and not Henry Crawford for her hero.

I teach college aged boys all the time, so Edmund’s infatuation with Mary seems to me the most natural thing in the world – and his unrecognized attachment to Fanny (I am convinced by Juliet McMaster on this subject, largely because I came to the same conclusion on my own) is just the sort of blindness I have seen in my own students and even a brother or two of my own. Moreover, Austen seemed to me to be showing that his struggles at the end of the novel were rewarded not only by gaining Fanny, but also by gaining his brother Tom, who had never really cared much for him at all. That happened instead of the Cinderella ending of Edmund’s inheriting Mansfield Park and elevating Fanny to be mistress of it. And so Tom’s illness, which I had discussed with my friend Dr. Cheryl Kinney, became for me a key to understanding both men’s roles in the novel.

[You can read Juliet’s argument in her post “Is Edmund Bertram right about anything?” and you can also read Cheryl’s discussion of “Why Tom Bertram is right that Dr. Grant will ‘soon pop off.’” – Sarah]

I have always been interested in the sibling relationships in Mansfield Park, which start out in an unpromising way with the initial twisted Cinderella story of the three Ward sisters, in which Aunt Norris and Mrs. Price seem to play the role of the ugly stepsisters. Sir Thomas and Aunt Norris’s discussion of the potential romantic relationships that could arise between the adopted Fanny and the two Bertram boys also makes us think about sibling relationships as much as romantic ones. When I ask my students if the boys’ relationship with Fanny is the same as that they have with their sisters, they start to realize that at least Edmund’s is not, and it also becomes apparent that the Bertram siblings are far from close. It is clear that Edmund and his sisters do not have much in common, just as it is clear that Tom and Edmund share very little in the way of values or interests. It does not seem that their mother was close enough to her siblings to care if she were separated forever from the youngest, Fanny’s mother, and the younger generation in both the Bertram and Price families have inherited a cold attitude toward relations.

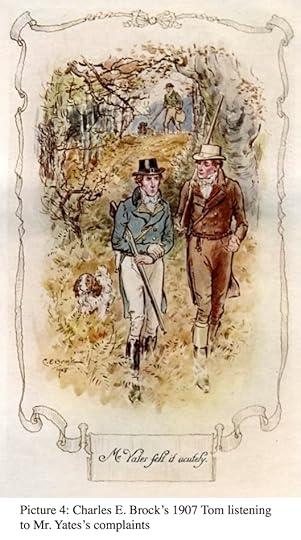

Edmund and Tom have a particularly important relationship in the novel, though Austen separates them and keeps Tom offstage a good deal of the time. Edmund often strikes readers as the elder of the two, and Mary Crawford even wishes for him to step into his elder brother’s place should Tom (as she hopes) die of the illness that afflicts him as part of the crisis and climax of the novel. However, though Edmund often arrogates authority to himself in conversations with his siblings and even with his mother and aunt, Edmund clearly has no wish to usurp Tom’s position as heir and future landowner. I would like to focus on significant communications that Edmund and Fanny share regarding Tom as the elder Bertram brother lies on his sickbed. Edmund’s notes to Fanny reveal an important change in Tom’s relationship with his younger brother:

. . . but when able to talk or be talked to, or read to, Edmund was the companion he preferred. His aunt worried him by her cares, and Sir Thomas knew not how to bring down his conversation or his voice to the level of irritation and feebleness. Edmund was all in all. Fanny would certainly believe him so at least, and must find that her estimation of him was higher than ever when he appeared as the attendant, supporter, cheerer of a suffering brother. There was not only the debility of recent illness to assist: there was also, as she now learnt, nerves much affected, spirits much depressed to calm and raise, and her own imagination added that there must be a mind to be properly guided.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 45 (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2005)

Yes, Fanny does make some of her own imaginative additions, but Edmund’s narrative of his services to Tom in his letters emphasizes Tom’s depression and agitation. That Edmund is “all in all” may not be Tom’s phrase but Fanny’s, but she is reading between the lines with more than just an admirer’s discernment. As Edmund reveals the difficulty Tom has with the presence of his parents, he also reveals, without meaning to do so, how much Tom wants him and only him in the sick room. Edmund “attends, supports” and “cheers” him, proving to Tom what real friendship is when he has just suffered from the negligence of the London friends whose company he had previously preferred. Moreover, the narrator briefly confirms Fanny’s perception of Tom’s new regard for Edmund when Edmund returns to Mansfield after having fetched Fanny from Portsmouth: “Edmund was almost as welcome to his brother, as Fanny to her aunt . . .” (Chapter 47).

Edmund appears to the reader as the superior of the two brothers, healthy and protective when Tom is suffering and weak – and all this when he is crushed by the severest, the only, romantic disappointment of his young life. However, Austen still does not want to confirm Mary Crawford’s hopes and transform him into the future Sir Edmund. If Edmund succeeds in his task he will himself, personally, prevent a gap from opening up that would allow the author to slip him into the seat of secular power. Edmund reveals his moral strength and humility in nursing the sick, preserving Tom to lead Mansfield Park after Sir Thomas. Austen resolutely refuses to join with Mary Crawford in wishing “wealth and consequence” to be conferred upon her hero.

Thus, a changed Tom receives as a gift at the end of the novel a new appreciation of the goods Edmund has always espoused, and a priest in his parish who is not only his most loyal supporter, but also a loving brother. His future sister-in-law is also not greedy for power or money that would come her way (unbeknownst to her) should Tom die. During Tom’s illness, she is “more inclined to hope than fear for her cousin, except when she thought of Miss Crawford; but Miss Crawford gave her the idea of being the child of good luck, and to her selfishness and vanity it would be good luck to have Edmund the only son.” Fanny has no such ambition for Edmund, although she values him so much more highly than Tom.

But Fanny need not worry, for no such good luck attends Miss Crawford; Jane Austen is the only fairy godmother of this book and her gift to siblings is that they love each other and live and enjoy that affection. If Tom Bertram were to die, Austen could not show the power brotherly love might have not only in the family but also in the political world where church and state vie for highest status. Tom undergoes illness not to make way for the more meritorious Edmund, but because, as moral writer, Anglican priest Thomas Gisborne writes in “The Duties of a Clergyman,” “Sickness naturally disposes the mind to seriousness and reflection; and, by withdrawing its attention and loosening its attachment from the objects of the present world, fits it for estimating according to their real importance the concerns of that which is to come” (An enquiry into the duties of men in the higher and middle classes of Society in Great Britain: Resulting from Their Respective Stations, Professions, and Employments [London: B & J White, 1795]).

Though critics have neglected Tom, his creator Jane Austen says, “Tom became what he ought to be, useful to his father, steady and quiet, and not living merely for himself” (Chapter 48). From the demanding Jane Austen, that is high praise indeed, and confirms that by the end of the novel, it is not only Edmund who deserves to be entrusted with a great responsibility.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Karen Doornebos, Lynn Shepherd, and Elisabeth Lenckos.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

December 12, 2014

Tantrums and Toasted Cheese: On Saying NO to Boys of All Ages

Thirty-second in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Amy Patterson is recognizable to many Janeites as one of the three fabulous women behind the Jane Austen Books tables at JASNA AGMs. When she’s not selling books in person or online, she writes for Jane Austen’s Regency World Magazine , and works on long-term writing projects. Amy says she’s currently in the “slow-but-steady process” of blogging her recent trip to England at her site amylpatterson.wordpress.com . Last week she wrote about her visit to the beautiful town and bookshops of Hay-on-Wye in Wales, where she bought a lot of books and forgot what century it is.

She tells me she enjoys “reading, baking, and life with the two craziest little boys around.” Since Amy knows a great deal about both Jane Austen and kids, I interviewed her last year about introducing children to Austen and her novels. I’m very happy to introduce her guest post on the toasted cheese in Portsmouth.

Fanny, fatigued and fatigued again, was thankful to accept the first invitation of going to bed; and before Betsey had finished her cry at being allowed to sit up only one hour extraordinary in honour of sister, she was off, leaving all below in confusion and noise again; the boys begging for toasted cheese, her father calling out for his rum and water, and Rebecca never where she ought to be.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 38 (www.pemberley.com)

Oh, those boys. I feel for Mrs. Price. Boys certainly do beg for toasted cheese. And they certainly do ride around on earth in a clamor of “confusion and noise.” They are like little gods descending from the sky on clouds of chaos, demanding fealty from anyone in the house who can reach the refrigerator. My youngest, Charlie, once famously commanded me: “Mom! Get back in yours kitchen and make mine dinner!” I smiled patiently, and informed him that he would have to wait just like the rest of us.

Little boys are hardly the perfect companions for one in Fanny’s state of mind at the end of Chapter 38. Her punishment, the annihilation of peace and solitude, is a fitting representation of the future annihilation of such comforts that will take place if she submits to Sir Thomas’s will and marries Henry Crawford. The wilds of a low-rent Portsmouth establishment are as true a test as any given to an Austen heroine. Fanny of course passes the test through moral strength and spiritual fortitude, but after seeing her family up close it’s hard for the reader, and for Fanny herself, to figure out where these qualities come from.

Through Fanny’s eyes, we see Mrs. Price as a woman without the capacity to do much at all to help her children other than pet and hover over her favorite one. Mrs. Norris complains on her sister Price’s behalf that her inability as a parent is due to the multitude of children she’s had, but evidence suggests that Mrs. Price would probably not make a great mother to a smaller number of children, regardless of her wealth or status.

As Fanny’s stay in Portsmouth lengthens, she discovers that there is not much difference between Lady Bertram and her own mother, both listless personalities. Fanny, blinded by the bit of affection she’s received from Lady Bertram, perhaps doesn’t make the connection that her benefactress is just as neglectful a parent as Mrs. Price – only Lady Bertram has Aunt Norris for assistance, while Mrs. Price has poor, useless Rebecca.

In Chapter 39, the narrator laments that Fanny “must and did feel that her mother was a partial, ill-judging parent, a dawdle, a slattern, who neither taught nor restrained her children, whose house was the scene of mismanagement and discomfort from beginning to end.” Lady Bertram’s house would be the same if not for her income and status – in other words, without a hanger-on like Aunt Norris, whose zeal overcomes any mismanagement by Lady Bertram. It’s hard to imagine a young Edmund creating havoc and demanding food and treats, but as for the rest of the Bertram children, it’s not a leap to believe that their demands were constant, and most likely fulfilled only by their overbearing Aunt, instead of ignored by a dawdle of a mother or achieved half-heartedly by a lazy maid.

But somehow a few of the adult children of both mothers manage to make it into adulthood with their moral fortitude intact. Susan – even though she has spent her life with a disengaged, unaffectionate, ineffective mother and an alcoholic father – still knows what is right and wrong, and still works exasperatedly on her little brothers to behave themselves. Fanny is thoroughly good, as we see throughout the book, and William is an ambitious and bright young man eager to be of service to crown and country. As for their cousins – after Tom’s illness, he is almost as willing to be an upstanding heir as his brother Edmund. How can successful children come from such ineffective mothers? Is it as simple as the idea that “nature” is stronger than “nurture?”

Nature is pretty strong in little boys, and some of them never grow out of their need for physical fulfillment through food, play, or more worldly activities. The rambunctious little brothers at Portsmouth are a physical shock to Fanny’s system, but they are also a vivid reminder that there are men in the world whose nature has been combined with a profound lack of nurture, and that clamoring little boys who are spoiled by their mothers may be destined to grow into men who can’t take no for an answer. They are, in effect, miniature Henry Crawfords, unable to understand how their noise and their needs are unwelcome impositions on a mind seeking simple solitude.

As a mom of two such boys, the eldest of whom I just chased out of my office in tears because – I’m not kidding – he wants grilled cheese and it’s not dinner time yet, I hope all my nurturing will give me the right kind of Henry. (The Tilney kind, not the Crawford kind.) But I should probably get back in the kitchen and make some dinner before I think too hard about it.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Theresa Kenney, Karen Doornebos, Lynn Shepherd, and Elisabeth Lenckos. Next week, in honour of Jane Austen’s birthday, there will be one post per day, beginning on Monday.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

December 5, 2014

The Manipulations of Henry and Mary Crawford

Thirty-first in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Margaret C. Sullivan is the author of Jane Austen Cover to Cover: 200 Years of Classic Covers (Quirk Books, November 2014), which includes the two cover images of Mansfield Park shown below, plus dozens more covers of all of Jane Austen’s novels and juvenilia, encompassing two centuries of publication. You can see a few of the covers in these recent articles she wrote for The Guardian and The Huffington Post. I’m especially interested in the cover of Emma that features Mr. Elton instead of Mr. Knightley, and the cover of Pride and Prejudice that shows Lydia Bennet “tenderly flirting” with soldiers at Brighton.  Margaret is also the author of The Jane Austen Handbook (Quirk Books, 2007) and There Must Be Murder, a novella sequel to Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey. She’s the founder of AustenBlog.com and loves to write metafiction about Jane Austen’s characters, such as the absolutely hilarious “League of Jane Austen’s Extraordinary Gentlemen” series – if you haven’t read it yet, I encourage you to do so, as soon as you finish reading her guest post on Henry and Mary Crawford. And then after that, you’ll want to read the dialogues she wrote to accompany some of the most absurd Austen covers ever produced.

Margaret is also the author of The Jane Austen Handbook (Quirk Books, 2007) and There Must Be Murder, a novella sequel to Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey. She’s the founder of AustenBlog.com and loves to write metafiction about Jane Austen’s characters, such as the absolutely hilarious “League of Jane Austen’s Extraordinary Gentlemen” series – if you haven’t read it yet, I encourage you to do so, as soon as you finish reading her guest post on Henry and Mary Crawford. And then after that, you’ll want to read the dialogues she wrote to accompany some of the most absurd Austen covers ever produced.

A few days ago, I ordered my copy of Jane Austen Cover to Cover from my friends at Jane Austen Books – Amy Patterson of JA Books is writing next week’s guest post on Mansfield Park – only to find, about an hour later, a message from my friends at Bookmark Halifax, one of my other favourite independent bookstores, saying they had just received a copy of the book and it made them think of me. I guess it’s obvious that the book is irresistible for Austen fans. I’m tempted to buy that copy at Bookmark, too, as I’m sure I could find a good home for it.  In Jane Austen’s time, it was considered improper for unrelated young persons of the opposite sex to correspond unless they were engaged. This social convention seems pretty strong; for instance, in Sense and Sensibility, when Marianne Dashwood corresponds openly with Willoughby, Elinor Dashwood takes it as a sign that Marianne and Willoughby are engaged, and is hurt that Marianne has not confided in her about the engagement. In Emma (do we need spoiler alerts? If so, spoiler alert!), Jane Fairfax takes great pains to hide her correspondence with Frank Churchill, because if the fact of their correspondence became public, so would their engagement. In Mansfield Park, although Fanny Price and Edmund Bertram are cousins, they don’t seem to correspond when he is away from Mansfield. Fanny treasures the unfinished note Edmund meant to leave for her with the chain for her cross as “the only thing approaching to a letter which she had ever received from him” (Chapter 27).

In Jane Austen’s time, it was considered improper for unrelated young persons of the opposite sex to correspond unless they were engaged. This social convention seems pretty strong; for instance, in Sense and Sensibility, when Marianne Dashwood corresponds openly with Willoughby, Elinor Dashwood takes it as a sign that Marianne and Willoughby are engaged, and is hurt that Marianne has not confided in her about the engagement. In Emma (do we need spoiler alerts? If so, spoiler alert!), Jane Fairfax takes great pains to hide her correspondence with Frank Churchill, because if the fact of their correspondence became public, so would their engagement. In Mansfield Park, although Fanny Price and Edmund Bertram are cousins, they don’t seem to correspond when he is away from Mansfield. Fanny treasures the unfinished note Edmund meant to leave for her with the chain for her cross as “the only thing approaching to a letter which she had ever received from him” (Chapter 27).

In my re-read of Mansfield Park earlier this year, the ways that other characters used and manipulated Fanny—and they are legion—seemed to catch my attention more than in previous reads. While I’m not especially fond of Fanny, I do feel sorry for her, and these incidents made me grind my teeth in anger. (It’s amazing how a book written 200 years ago can play on one’s emotions so strongly, isn’t it?) One incident in particular stood out for me: Mary Crawford’s letters to Fanny that are sent not in affection or even in friendship but with the sole intention of manipulating Fanny and imposing upon her.

[Fanny] had reason to suppose herself not yet forgotten by Mr. Crawford. She had heard repeatedly from his sister within the three weeks which had passed since their leaving Mansfield, and in each letter there had been a few lines from himself, warm and determined like his speeches. It was a correspondence which Fanny found quite as unpleasant as she had feared. Miss Crawford’s style of writing, lively and affectionate, was itself an evil, independent of what she was thus forced into reading from the brother’s pen, for Edmund would never rest till she had read the chief of the letter to him; and then she had to listen to his admiration of her language, and the warmth of her attachments. There had, in fact, been so much of message, of allusion, of recollection, so much of Mansfield in every letter, that Fanny could not but suppose it meant for him to hear; and to find herself forced into a purpose of that kind, compelled into a correspondence which was bringing her the addresses of the man she did not love, and obliging her to administer to the adverse passion of the man she did, was cruelly mortifying. Here, too, her present removal promised advantage. When no longer under the same roof with Edmund, she trusted that Miss Crawford would have no motive for writing strong enough to overcome the trouble, and that at Portsmouth their correspondence would dwindle into nothing.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 38 (www.mollands.net)

While Marianne Dashwood might not worry too much about how her letters to Willoughby are perceived by others, it is highly unlikely that Fanny Price or Edmund Bertram would agree to engage in anything clandestine, and both the Crawfords know it. Henry Crawford could not correspond with Fanny Price, but Mary Crawford could, and Henry could then add a few lines to it; Mary could not correspond with Edmund Bertram, but she could correspond with Fanny, who could be expected to read the letter to Edmund; both Crawfords use this unwelcome correspondence to engage in a socially forbidden activity.

It’s not surprising that Fanny understands exactly what the Crawfords were up to, and finds the situation unpleasant. It is, however, surprising that Edmund doesn’t seem to have rumbled to it—or worse yet, is okay with it. It is just like Mary Crawford to take advantage of the situation. To outside observers, she is obeying all the rules, and also bestowing a kind, condescending attention on poor little Fanny Price by bestowing upon her such charming, witty correspondence, but Mary’s real intentions are more insidious—manipulating Fanny once again to gain her ends and her brother’s.

Henry Crawford’s relationship with Fanny began with pure manipulation, which even he does not attempt to rationalize: he seeks to entertain himself by “making a small hole in Fanny Price’s heart.” Henry ends up falling in love with Fanny, or at least he thinks he is, and is so blinded by self-delusion that he fails to recognize Fanny’s gift of observation, or realize that she knows exactly how he had treated Maria Bertram and is able to guard herself against him.

Henry Crawford’s relationship with Fanny began with pure manipulation, which even he does not attempt to rationalize: he seeks to entertain himself by “making a small hole in Fanny Price’s heart.” Henry ends up falling in love with Fanny, or at least he thinks he is, and is so blinded by self-delusion that he fails to recognize Fanny’s gift of observation, or realize that she knows exactly how he had treated Maria Bertram and is able to guard herself against him.

Henry learns what is most important to Fanny—her brother William and his naval career—and performs the ultimate act of manipulation: he gets William his promotion to lieutenant. It’s such an important thing for William, and so easy for Henry to bestow almost on a whim, and for his own ends. How can Fanny Price, he thinks, loving sister that she is, be anything other than grateful; and how can she turn down a marriage proposal from the author of this all-important act? And yet, she does; nonetheless, he follows her to Portsmouth. Today, some might see Henry’s behavior as a form of stalking. Certainly his complete refusal to take “no” for an answer is troublesome in a modern context. (I won’t go down the rabbit hole of rape culture, but there might be a dissertation in there for some smart graduate student.) Even in the context of the time, it seems ungentlemanly at best to continue to pester a lady when she’s made her opinion very clear. In fact, it seems most . . . Mr. Collinsish. Not a very romantic comparison!

Another surprising aspect of that passage is the rather weary cynicism of it—one does not think of Fanny Price in that way, but in this re-read I noticed several incidents where Fanny, in her inner monologues, expresses feelings of active resentment, especially towards Mary Crawford. I find I like her the better for it. Jane Austen wrote that she did not like her heroines to be “pictures of perfection,” and Fanny would be a revoltingly saintly picture of perfection indeed if she did not at least occasionally despise the people who use and manipulate her just because they can.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Amy Patterson, Theresa Kenney, Karen Doornebos, and Lynn Shepherd.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

November 28, 2014

Refashioning Memory

Thirtieth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Sara Malton is Associate Professor of English at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, where she specializes in nineteenth-century literature, especially the intersection of fiction, finance, and law. After receiving her Ph.D. from the University of Toronto in 2004, she went on to a Postdoctoral Fellowship at Cornell University and after that she joined Saint Mary’s in 2005. Sara and I first met at a conference when we were both in grad school, and we reconnected a few years ago, after I moved back to Halifax. We’ve had many conversations about Austen, Dickens, Gaskell, and other nineteenth-century writers, and about our own writing projects, too. I’m very happy that she’s joining the Mansfield Park party on my blog with her guest post on memory.

Sara’s book, Forgery in Nineteenth-Century Literature and Culture: Fictions of Finance from Dickens to Wilde, was published by Palgrave in 2009. Her work has also appeared in such journals as Studies in the Novel, Victorian Literature and Culture, the European Romantic Review, and English Studies in Canada, and she’s currently working on a book on naval impressment and nineteenth-century culture. She’s a Trustee of the Dickens Society, and she’s going to host the Annual Dickens Society Symposium in Halifax in July 2015.

William had obtained a ten days’ leave of absence to be given to Northamptonshire, and was coming, the happiest of lieutenants, because the latest made, to shew his happiness and describe his uniform.

He came; and he would have been delighted to shew his uniform there too, had not cruel custom prohibited its appearance except on duty. So the uniform remained at Portsmouth, and Edmund conjectured that before Fanny had any chance of seeing it, all its own freshness and all the freshness of its wearer’s feelings must be worn away. It would be sunk into a badge of disgrace; for what can be more unbecoming, or more worthless, than the uniform of a lieutenant, who has been a lieutenant a year or two, and sees others made commanders before him? So reasoned Edmund, till his father made him the confidant of a scheme which placed Fanny’s chance of seeing the 2d lieutenant of H.M.S. Thrush, in all his glory, in another light.

This scheme was that she should accompany her brother back to Portsmouth, and spend a little time with her own family. It had occurred to Sir Thomas, in one of his dignified musings, as a right and desirable measure; but before he absolutely made up his mind, he consulted his son. Edmund considered it every way, and saw nothing but what was right. The thing was good in itself, and could not be done at a better time; and he had no doubt of it being highly agreeable to Fanny. This was enough to determine Sir Thomas; and a decisive “then so it shall be” closed that stage of the business; Sir Thomas retiring from it with some feelings of satisfaction, and views of good over and above what he had communicated to his son; for his prime motive in sending her away had very little to do with the propriety of her seeing her parents again, and nothing at all with any idea of making her happy. He certainly wished her to go willingly, but he as certainly wished her to be heartily sick of home before her visit ended; and that a little abstinence from the elegancies and luxuries of Mansfield Park would bring her mind into a sober state, and incline her to a juster estimate of the value of that home of greater permanence, and equal comfort, of which she had the offer.

It was a medicinal project upon his niece’s understanding, which he must consider as at present diseased. A residence of eight or nine years in the abode of wealth and plenty had a little disordered her powers of comparing and judging. Her father’s house would, in all probability, teach her the value of a good income; and he trusted that she would be the wiser and happier woman, all her life, for the experiment he had devised.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 37 (London: Penguin, 1966)

“‘Am I to understand,’ said Sir Thomas, ‘that you wish to refuse Mr. Crawford?’” Illustration by C. E. Brock. (http://mollands.net/etexts/images/mpillus/mpbrockwc19.jpg)

The desire for Mansfield that Sir Thomas wishes to induce in Fanny renders him in many ways a forebear of later nineteenth-century novelists: with some assistance from Edmund, he essentially becomes the author of the whole piece, and the strategies involved in his “medicinal project” lead to the central character’s crucial confrontation with her origins. Over the course of the century, such a confrontation will come to shape the contours of the Victorian novel. Yet here, of course, the home that Sir Thomas desires Fanny to long for is not her originary one, but her adopted place.

Fanny’s “transplantation” (something also worth considering in relation to Sir Thomas’ connection to slavery) looks forward to the shifting notions of home, which will more thoroughly inform Austen’s next novel, Persuasion. There, when Anne Elliot first finds herself facing a removal from Kellynch Hall to her sister’s home, she finds that “it was highly incumbent on her to clothe her imagination, her memory, and all her ideas in as much of Uppercross as possible.” How we dress ourselves, our ideas, and our nation is indeed key here as well: it is, after all, the opportunity for Fanny to view her brother William in the uniform of a lieutenant that presents, to Sir Thomas’ delight, the occasion for her journey to Portsmouth. Persuasion also registers at length Austen’s interest in and connection to the naval realm; appropriately, then, Fanny’s most overt confrontation with the contingencies of memory and home takes place at Portsmouth and in the context of William’s promotion and imminent voyage.

“William was often called on by his uncle to be the talker.” Illustration by C. E. Brock. (http://mollands.net/etexts/images/mpillus/mpbrockwc14.jpg)

The flaws of Sir Thomas’ aims and method are underscored by the fact that in seeking a “cure” for Fanny’s “diseased” mind, he threatens her infection with yet another. The plots of Fanny and William converge again in this respect, for each is dispatched on a mission associated with similar effects on the psyche. The very “cure” that Sir Thomas imagines will convince Fanny to accept Henry Crawford’s proposal – homesickness – was in fact a disease of mind especially associated with the military man’s plight: in the eighteenth-century “nostalgia” was the medical term assigned to the illness brought on by the enforced removal from home, something typically experienced by the sailor or soldier while in service.

In the end, Sir Thomas’ plot is all the more successful given that Fanny finds at Portsmouth that she has been essentially forgotten. Her visit seems to pull her backward, into the realm of incivility and forgetfulness – a world, in short, of so much noise and so little thought. Yet it ultimately propels her forward, though not as Sir Thomas had anticipated: Fanny’s marriage to Edmund moves us away, however slightly, from a wholly traditional social model that insists upon the determinacy of home and origins. Instead, as William’s progress shows, inwardness may carry its own reward, and take us some way toward the real “cure” necessary for a nation of diseased morality, figured elsewhere by Henry and Mary Crawford on land and Admiral Crawford at sea.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Margaret C. Sullivan, Amy Patterson, Theresa Kenney, and Karen Doornebos.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

November 25, 2014

Your Invitation to Jane Austen’s Birthday Celebration in Halifax

You’re invited to celebrate Jane Austen’s 239th birthday with us in Halifax.

We’re celebrating nine days early, on Sunday, December 7th, at 12:00 p.m. at The Arms, the restaurant at The Lord Nelson Hotel (across the street from the Public Gardens), 1515 South Park Street, Halifax, Nova Scotia.

I expect there will be plenty of conversation about the 200th anniversary of Mansfield Park (and if there isn’t, you can be sure I’ll do my best to change that…), and Hugh Kindred will give his annual toast to Jane. (If you missed Hugh’s guest post for “An Invitation to Mansfield Park,” on William Price, you can find it here.)

I expect there will be plenty of conversation about the 200th anniversary of Mansfield Park (and if there isn’t, you can be sure I’ll do my best to change that…), and Hugh Kindred will give his annual toast to Jane. (If you missed Hugh’s guest post for “An Invitation to Mansfield Park,” on William Price, you can find it here.)

For the celebration, let’s “eat Ice [cream] & drink French wine,” as Jane Austen wrote to her sister Cassandra in an 1808 letter. Or — I’ve just checked the menu — we could eat French toast with whipped cream and Nova Scotia maple syrup, and drink Nova Scotia wine.

Please let our Regional Coordinator, Anne Thompson, know by December 4th if you’d like to join us, or leave a comment here so I can pass on the information to her.

P.S. The ratafia cakes I made for our November JASNA NS meeting, from The Jane Austen Cookbook, were delicious. Thanks to everyone who voted! For those who weren’t here to taste them — I wish I could send you some. The recipe is very easy to make (ground almonds, caster sugar, orange liqueur, and egg whites) and I’m glad to have discovered it. I’d still like to try making Mrs. Perrot’s Pound Cake and Martha’s Gingerbread Cakes sometime.

November 21, 2014

Austen’s Sirens

Twenty-ninth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

I first met Sharon Hamilton at the University of Alberta when I was an undergraduate, and later connected with her again at Dalhousie University, where she was working on her Ph.D. in English when I began my master’s degree. I remember the exact moment at which we discovered our shared love of Jane Austen – at a dinner celebrating the birthday of a mutual friend – and Sharon exclaimed, “You’re a Janeite, too!” Sharon and I also share a love of Prince Edward Island’s landscape and beaches as well as its literature.

Dalvay Beach, PEI

Sharon is a writer and researcher who divides her time between Ottawa, Ontario and Spring Brook, PEI. She specializes in American literature and she has published and given lectures on the work of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, H.L. Mencken, Emily Dickinson, Willa Cather, and many other writers. Her essay “Teaching Hemingway’s Modernism in Cultural Context: Helping Students Connect His Time to Ours” will be published next year in Teaching Hemingway and Modernism, edited by Joseph Fruscione (Kent State University Press). Her guest post on Mansfield Park is partly inspired by her response to the post Juliet McMaster wrote in the summer for this series, “Is Edmund Bertram right about anything?”

“His reading was capital.” Illustration by C.E. Brock. (http://www.mollands.net/etexts/mansfieldpark/mpillus.html)

Edmund watched the progress of her attention, and was amused and gratified by seeing how she gradually slackened in the needlework, which at the beginning seemed to occupy her totally: how it fell from her hand while she sat motionless over it, and at last, how the eyes which had appeared so studiously to avoid him throughout the day were turned and fixed on Crawford – fixed on him for minutes, fixed on him, in short, till the attraction drew Crawford’s upon her, and the book was closed, and the charm was broken. Then she was shrinking again into herself, and blushing and working as hard as ever; but it had been enough to give Edmund encouragement for his friend, and as he cordially thanked him, he hoped to be expressing Fanny’s secret feelings too.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 34 (London: Penguin, 1966)

It is no surprise that such an interesting, thought-provoking entry should come from Juliet McMaster, who I have had the great pleasure of knowing as a teacher. (Here’s the link to her guest post.) Also not surprising, given Jane Austen’s Shakespeare-like ability to write a text that operates on so many levels, is the realization that all the entries in the conversation about this post (see the comments section here), however apparently contradictory, are I think, equally true.

What I would wish to add to this conversation is the question (lifted from Tina Turner), “What’s love got to do with it?” In other words, I believe that what Edmund ultimately feels for Mary Crawford (and what the young female characters in the novel generally feel for Henry) isn’t love, it’s lust. It is, as we know, very common for Austen to place in her novels characters with extraordinary sexual magnetism: think of Wickham and Willoughby. Even in her juvenilia, in Jack and Alice, Austen describes Charles Adams as “so dazzling a beauty that none but eagles could look him in the face.” The interesting thing about Mansfield Park, is that while Austen often places male figures of extreme physical attractiveness in her works, in this novel the snake in the garden, who exercises the common Austen-novel function of tempting others to lust (not love), is both male and female: Mary and Henry.

Thanks to Homer, we generally associate the destructive (and implicitly sexual) call of the siren with women, owing to the female sirens in The Odyssey whose song lures sailors onto the rocks, where their ships are destroyed. It is nevertheless the case that in Greek tradition – as I believe Austen was well aware – sirens were both male and female, just as they are in this novel. In the Greece-obsessed Regency world Austen lived in (think of the female hair and clothing designed to look like Greek statues), there would have been many occasions to view actual Greek vases, and as classicists explain (see Jessika Akmenkalns, “Sirens,” review of “Wining, Dining, and Dying in Ancient Greece,” CU Art Museum, University of Colorado), many of these vases pictured male sirens. (You can find a good picture of a male siren in the collections of the J. Paul Getty Museum.)

We get a strong hint that this is exactly what Austen had in mind though her depiction of Henry Crawford reading Shakespeare, during which he pulls Fanny in completely (siren-like) through the seductive sound of his voice, which draws Fanny’s attention until her eyes are completely “fixed” on him and she cannot drop them away until he stops reading, and the “charm was broken.”

The siren-like sexual pull exerted by both Mary and Henry is why I believe all the comments made in response to “Is Edmund Bertram right about anything?” make sense. Whereas, especially in a novel written in a Regency world, we can actually appreciate a woman who permits herself to experience sexual attraction without love as, for example, in the case of Elizabeth and Wickham – because isn’t this, in a way, something we can embrace as a kind of proto-feminism? – we cannot appreciate in the same way (or, on some levels, even respect) a male character who allows himself to be so seduced. I think the comments about our difficulties in embracing Edmund as a hero relate both to his poor judgment (as noted here) and to the fact that there is nothing progressive, only disappointing – and, let’s face it, historically rather common – about a male figure who falls into lust.

Dr. McMaster’s defenses of Edmund too, though, also make sense: especially the theory that this novel keeps presenting us with evidence that, at some level, in his heart, he always knows he is in love with Fanny, even as he is lured by the siren sound of Mary. His various cares of Fanny are the novel’s way of showing us that siren sounds, while powerfully seductive, are always being countered by that still small voice that tries (in spite of all) to protect us from ourselves – the moral love in the universe that will always attempt – if only we will listen! – to keep us away from the rocks.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Sara Malton, Margaret C. Sullivan, Amy Patterson, and Theresa Kenney.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

November 19, 2014

The Real Reads Mansfield Park – a review

My friend Rose is thirteen and she loves to read, so I asked for her opinion of the Real Reads adaptation of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. I’ve written about the Real Reads adaptations of Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice, but this time around I wanted to hear from someone in the target audience for these abridged versions of Austen’s novels – someone who hasn’t yet read Mansfield Park itself. The Real Reads Austen books are retold by Gill Tavner and illustrated by Ann Kronheimer.

I’m very happy to share Rose’s guest post with you, as part of the ongoing celebrations of 200 years of Mansfield Park. Rose lives in Massachusetts, and her favourite books include Harry Potter, by J.K. Rowling, Percy Jackson and the Olympians, by Rick Riordan, The Mortal Instruments series, by Cassandra Clare, Will Grayson, Will Grayson, by John Green, and Cornelia and the Audacious Escapades of the Somerset Sisters, by Lesley M. Blume. This last one, she says, is “the sweetest, saddest, happiest, book I will ever read in my entire life,” and she tells me her favourite word from that book is “defenestrate.” I hope you enjoy reading her review.

Can I first say that it has got to be tough to fit such a giant book into this tiny, cute, little illustrated thing. I read Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice and it was big and complicated, mainly because the characters were too. This adaptation was really interesting to read and I haven’t read the full Mansfield Park so I knew nothing about what was supposed to or not supposed to happen. Just after I finished reading I was disappointed. The characters were a little boring and Fanny just annoyed me.

I thought it over more and realized that of course the characters are flat; this thing was a little over 50 pages. Fanny wasn’t annoying, she was human. A lot of characters I see are brave and strong and smart, their only flaw being their pride and overconfidence. It is rare and kind of neat to see someone uncomfortable and weak who does turn out to be the hero of the story.

Something else I was uncomfortable with was how unclear it was whether or not Edmund loves Fanny back. The point of view we saw made it seem one-sided. The short amount of space we had to let this happen made it seem like he wasn’t over Mary but he “needed” a wife. This made me feel almost like Fanny was being taken advantage of because she was so adoring. I was and still am curious to see what really happened.

These ideas, although simplified, need more explanation and depth for me to get them. This adaptation made me want to read the original book and hopefully will do the same for other young people. I honestly can’t wait until I see the characters as they really are and watch them grow. I am glad I read this to help me understand and grab my interest but it isn’t all that great on its own. My conclusion: read Mansfield Park in its entirety.

Read more about introducing Austen’s novels to younger readers on my page “Jane Austen for Kids.”

November 14, 2014

Fanny Price as a Student of Shakespeare

Twenty-eighth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

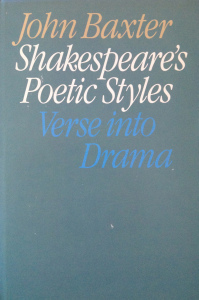

John Baxter is Professor of English at Dalhousie University, where he teaches classes on Early Modern literature, Elizabethan and Jacobean drama, rhetoric, and religion and literature. He’s the author of Shakespeare’s Poetic Styles: Verse Into Drama (Routledge) and many essays on Shakespeare, as well as on several other writers, including Ben Jonson, J.V. Cunningham, Janet Lewis, Yvor Winters, Helen Pinkerton, and George Elliott Clarke. With Gordon Harvey, he edited a collection of essays by C.Q. Drummond called In Defense of Adam: Essays on Bunyan, Milton, and Others (Brynmill Press/Edgeways Books), and with J. Patrick Atherton, he edited George Whalley’s groundbreaking translation of Aristotle’s Poetics (McGill-Queen’s University Press).

John Baxter is Professor of English at Dalhousie University, where he teaches classes on Early Modern literature, Elizabethan and Jacobean drama, rhetoric, and religion and literature. He’s the author of Shakespeare’s Poetic Styles: Verse Into Drama (Routledge) and many essays on Shakespeare, as well as on several other writers, including Ben Jonson, J.V. Cunningham, Janet Lewis, Yvor Winters, Helen Pinkerton, and George Elliott Clarke. With Gordon Harvey, he edited a collection of essays by C.Q. Drummond called In Defense of Adam: Essays on Bunyan, Milton, and Others (Brynmill Press/Edgeways Books), and with J. Patrick Atherton, he edited George Whalley’s groundbreaking translation of Aristotle’s Poetics (McGill-Queen’s University Press).

He’s also my father, and I’m absolutely delighted to introduce his guest post on Fanny Price and Shakespeare for my “Invitation to Mansfield Park” series.

The oral reading of Shakespeare in Mansfield Park summons up a number of contrasts. Theatrical skills are seen in a positive light rather than the negative light of Lovers’ Vows. The disreputable Henry Crawford gives a command performance that is admired by the characters – and surely by the author too. And the ever-vigilant Fanny Price is caught off-guard. But what, exactly, captures her attention? And why is the play Henry VIII?

In spite of her best intentions, Fanny cannot resist the performance:

She could not abstract her mind for five minutes; she was forced to listen; his reading was capital, and her pleasure in good reading extreme. To good reading, however, she had been long used; her uncle read well – her cousins all – Edmund very well; but in Mr. Crawford’s reading there was a variety of excellence beyond what she had ever met with. The King, the Queen, Buckingham, Wolsey, Cromwell, all were given in turn; for with the happiest knack, the happiest power of jumping and guessing, he could always light, at will, on the best scene, or the best speeches of each; and whether it were dignity or pride, or tenderness or remorse, or whatever were to be expressed, he could do it with equal beauty. – It was truly dramatic. – His acting had first taught Fanny what pleasure a play might give, and his reading brought all his acting before her again; nay, perhaps with greater enjoyment, for it came unexpectedly, and with no such drawback as she had been used to suffer in seeing him on the stage with Miss Bertram.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 34 (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2005)

Edmund notices that she is enraptured, that her eyes are “fixed on Crawford, fixed on him for minutes, fixed on him in short till the attraction drew Crawford’s upon her,” and with a jealously acute memory (which is perhaps more than fraternal), he later recalls this moment and imagines it as proof of an erotic attachment: “who that heard him read, and saw you listen to Shakespeare the other night, will think you unfitted as companions?”

That the reading of Shakespeare in this context is erotic there is little doubt, even if it is not quite as Edmund imagines it. But if Fanny’s enjoyment of Henry’s acting is rather different from Maria Bertram’s enjoyment, what does it consist of? And who knew that Henry’s acting in Lovers’ Vows “had first taught Fanny what pleasure a play might give”? The rehearsal scenes for that play seemed to have occasioned mostly pain for Fanny, so that “pleasure” here comes as a surprise, and “first taught” implies that reading Shakespeare offers a second lesson similar to the first. How could the pleasures of Lovers’ Vows conceivably be aligned with the pleasures of Henry VIII?

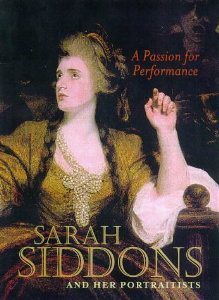

The Cambridge editor John Wiltshire remarks that Henry VIII was in vogue during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, particularly with Sarah Siddons in the role of Queen Katherine, and he notes as well that “the play’s many ‘fine speeches’ by male characters, together with the absence of bawdy passages, probably also contributed to its popularity and its choice by JA for Fanny’s reading aloud.” One of the virtues of this note is in drawing attention to the fact that it is Fanny who first selects Henry VIII for reading aloud (to Lady Bertram), even if Henry Crawford takes over the performing of it, but the emphasis on the negative principle of an absence of bawdy language and the miscellaneous feel of many fine speeches tends to suggest a principle of selection (on the part of both author and character) that is rather more adventitious than artistically or psychologically purposeful.

The Cambridge editor John Wiltshire remarks that Henry VIII was in vogue during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, particularly with Sarah Siddons in the role of Queen Katherine, and he notes as well that “the play’s many ‘fine speeches’ by male characters, together with the absence of bawdy passages, probably also contributed to its popularity and its choice by JA for Fanny’s reading aloud.” One of the virtues of this note is in drawing attention to the fact that it is Fanny who first selects Henry VIII for reading aloud (to Lady Bertram), even if Henry Crawford takes over the performing of it, but the emphasis on the negative principle of an absence of bawdy language and the miscellaneous feel of many fine speeches tends to suggest a principle of selection (on the part of both author and character) that is rather more adventitious than artistically or psychologically purposeful.

Jane Austen herself also conspires to make the choice of play seem serendipitous when she has Henry exclaim, “I do not think I have had a volume of Shakespeare in my hand before, since I was fifteen. – I once saw Henry the 8th acted. – or I have heard of it from somebody who did – I am not certain which. But Shakespeare one gets acquainted with without knowing how. It is part of an Englishman’s constitution.” Perhaps Austen, too, once saw Henry VIII acted or heard of it from somebody who did, though she is much less likely than Crawford to be uncertain which. In any case, it is worth considering more closely the versions she is likely to have known and the central role of Sarah Siddons that Wiltshire highlights.

A modern Shakespeare editor, Jay L. Halio, explains that “John Philip Kemble revived the play in 1788 after a twenty-year lapse, casting his sister, Sarah Siddons, in the role [of Queen Katherine] on Dr. Johnson’s recommendation” and that she was responsible for “a revolution in the representation of King Henry VIII, restoring the balance among principal characters that earlier eighteenth-century productions had lost in their emphasis upon the male leads.” Another critic, Hugh Richmond, argues that she “required of her fellow actors a shift in performance style toward the less ‘macho’ mode of interpreting Henry” that remains influential to this day.

If this is the performance style that Jane Austen knew, it seems plausible to assume that she deliberately chose the play because of a fundamental kinship between its heroine and the heroine of Mansfield Park. Both are women who may seem passive or inert from an external point of view, but who in reality are passionately devoted to their own deepest instincts and loyalties and who thus challenge the perspectives of the males in their circle.

At a general level, too, the play recommends itself because of its relentless investigation into the uses and abuses of power. Like Henry VIII, Mansfield Park presents a world in which love is hemmed in by a daunting array of powerful forces. Henry Crawford begins his pursuit of Fanny as a demonstration of his prowess, and when he becomes genuinely attracted to her, his sister represents that not as love but as triumph, celebrating “the glory of fixing one who has been shot at by so many; of having it in one’s power to pay off the debts of one’s sex.”

Fanny, of course, is not so interested in paying off the debts of her sex, but she is interested in a woman’s having the power to make her own choices, whatever forces of paternal and fraternal persuasion are arrayed against her.

“I should have thought,” said Fanny, after a pause of recollection and exertion, “that every woman must have felt the possibility of a man’s not being approved, not being loved by someone of her own sex, at least, let him be ever so generally agreeable. Let him have all the perfections in the world, I think it ought not to be set down as certain, that a man must be acceptable to every woman he may happen to like himself.” (Chapter 35)

Fanny and Katherine are admittedly faced with very different dilemmas, but they are alike in strongly resisting male pressure to alter their feelings in accordance with the putative advantages of a social or political order.

Yet Henry VIII, unlike Lovers’ Vows, does not provide the individual characters of Mansfield Park with quite the same chance to act out or project their own peculiar wishes and desires; what really counts in the oral reading of Shakespeare is the opportunity to see things steadily and to see them whole. In Lovers’ Vows, too, while the other characters are preoccupied with their isolated parts, the lesson Fanny draws comes from the perspective that the acting of that play gives into the structure of her whole little world.

Her second lesson, from Shakespeare, is similar, and the pleasure Fanny takes from Henry’s acting is the vision it gives of a complete world: “The King, the Queen, Buckingham, Wolsey, Cromwell, all were given in turn.” Conspicuously, “the Queen” is included in Fanny’s list of characters; Shakespeare’s enchanting voices are not restricted to males who deliver many fine speeches. In the revolutionary representation of Queen Katherine by Sarah Siddons that Jane Austen is likely to have known lies a model of a female passion or desire which is capable of restoring a balance and which is put to surprising and creative use in Mansfield Park. Edmund is right to intuit that listening to Shakespeare is an erotic experience, though he doesn’t yet see how it all fits together, and he fails to understand, at this point, that it is he and not the masterful actor who is the ultimate target of that eroticism. It is all truly dramatic.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park. Coming soon: guest posts by Sharon Hamilton, Sara Malton, Margaret C. Sullivan, and Amy Patterson.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

November 10, 2014

Tell, by Frances Itani

The Halifax Giller Light Bash is happening tonight at the Atlantica Hotel at 8pm, and I’m delighted to be one of the six panelists who are defending the books shortlisted for the Scotiabank Giller Prize. I’ll be championing Frances Itani’s beautiful and powerful novel Tell, which is set in the small town of Deseronto, Ontario, not long after the end of the Great War.

After we each make the case for why our chosen books ought to win the Giller ($100,000), everyone at the Halifax event (and at similar Giller Light Bashes in Vancouver, Calgary, Regina, Winnipeg, and Toronto) will watch the live announcement of this year’s winner. The event is a fundraiser for Frontier College, “Canada’s original literacy organization.” If you happen to be in Halifax this evening, I hope you’ll join us! Tickets are $8 for students, $12 in advance, and $15 at the door. Come out, have fun, and support a good cause.

After I agreed to defend Tell, I decided to go back and read Itani’s 2003 novel Deafening, because there are many links between the two books. In Tell, she focuses on four characters who appeared in the earlier novel, but weren’t central to the story. Deafening (which won a Commonwealth Writers’ Prize and was shortlisted for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award) takes place in Deseronto before and during the war, and the central character is Grania O’Neill, a young deaf woman who falls in love with a man who can hear, and who loves to sing. Deafening was Itani’s debut novel, and it received tremendous – and well-deserved – accolades for its depiction of silence, noise, and the challenges of communicating in Grania’s world.

As a critic and book reviewer, I have to say that I found it a little odd to sign on to praise and defend a book I hadn’t read yet – but I’m happy to say that I can recommend both of these novels highly, and that it will be very easy to cheer for Frances Itani and Tell tonight.

One of the things I found most moving about both Deafening and Tell is the way Itani draws connections between the experience of those at the front and the experience of those left behind. In Deafening, she traces the path of a stretcher bearer serving in Europe while she also follows the fortunes of his relatives in Deseronto during the influenza pandemic of 1918. In Tell, Kenan, a soldier who’s returned home disfigured and psychologically unable to leave his house, links his wife’s unfulfilled desire for a child with his own experience of the landscapes of war. The word “barren” startles him. “We’re barren, the two of us,” he thinks. “He had seen barren. Charred landscapes where nothing would grow. Trees without leaves, branches without birds. Razed earth that supported no life. Villages without people. Oh, yes, he had seen barren. He had known it intimately.”