Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 31

November 7, 2014

Worn Out with Civility at Mansfield Park

Twenty-seventh in a series of guest posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Sarah Woodberry is a writer and editor who has contributed to various print and online publications, including Reuters, SKI Magazine, and More Intelligent Life. She tells me that it wasn’t until about the third time she read Mansfield Park that she really began to appreciate the novel’s complexity. When she’s not rereading Jane Austen’s novels, she enjoys reading essays about them and browsing Janeite blogs. She says she “credits the lively online community of Janeites as providing some comfort against the hard reality of the finite number of words written by Austen herself.” I agree, and I suspect many of you will, too. Today she’s contributing to that ongoing conversation with this post on the challenge of being civil in Mansfield Park. Sarah lives in Darien, Connecticut. You can find her blogging about reading and writing at WordHits, and you can also connect with her on Twitter @WordHits.

“I am worn out with civility,” said [Edmund]. “I have been talking incessantly all night, and with nothing to say. But with you, Fanny, there may be peace. You will not want to be talked to. Let us have the luxury of silence.” Fanny would hardly even speak her agreement. A weariness, arising probably, in great measure, from the same feelings which he had acknowledged in the morning, was peculiarly to be respected, and they went down their two dances together with such sober tranquillity as might satisfy any looker-on that Sir Thomas had been bringing up no wife for his younger son.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 28 (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003)

One of the great pleasures of reading Jane Austen is that while you are lured along by her refined and carefully measured prose, suddenly off the page jumps one of her distinctive zingers: “I am worn out with civility,” says Edmund Bertram in Mansfield Park.

So often when reading Austen’s novels, I catch myself laughing out with surprise. Her vibrant, teasing social commentary still rings true after 200 years. Who hasn’t felt a touch of misanthropic fatigue after a long night of socializing and small talk?

Civility, or the lack of it, is a recurring theme in Austen’s works. She plays with it to challenge and define her characters, fine-tuning a Goldilocks scale of decorum. On one end, haughty and unfriendly behavior is the mark of villainous characters. Mrs. Norris, who torments Fanny in Mansfield Park, leads a cast of colorful Austen adversaries, which includes the Bingley sisters, Elizabeth Elliot, “Mrs. E,” and Fanny Dashwood—who is never to be confused with Fanny Price. Pre-transformation Darcy is a noted exception to this rule, as is perhaps the crotchety Mr. Palmer. At the other extreme, characters who are overly keen with their friendship and “happy manners” also turn out to be somewhat scheming and nefarious: Lucy Steele, Frank Churchill, Mr. William Elliot, the infamous George Wickham, and of course Mary and Henry Crawford in Mansfield Park.

Jane Austen’s heroines, however, exhibit just the right amount of “artless” civility, in that they are decorous and friendly with no ulterior motive other than to act properly. Although Marianne Dashwood and Emma Woodhouse each stumble with immaturity and a touch of thoughtlessness, none of Austen’s heroines is deliberately rude or unkind. Furthermore, they consistently—and rather impressively—resist the urge to retaliate when provoked by incivility. When Austen does allow one heroine to fire off a jab—Emma’s unfortunate ridiculing of Miss Bates—Emma regrets it fervently. This incident and its repercussions become a pivotal plot point. Certainly, Jane Austen did not approve of mean girls … or mean boys, ahem, Mr. Elton.

Although Austen does not allow her heroines to issue severe retorts, as narrator she often pokes fun at characters for them. Here in Mansfield Park, she is taking aim at Edmund. He complains, boasts almost, that he is “worn out with civility,” while at the same time he treats poor Fanny in a very off-handed manner. He’s so myopically distracted by Mary Crawford that he does not even notice how difficult this coming-out ball is for introverted Fanny, who also shrinks from “the toils of civility.” To boot, Fanny’s being stalked by the rakish Henry Crawford, and her heart aches because her dear brother William will be leaving in the morning, perhaps for years. Instead of concerning himself with Fanny’s troubles or comporting himself with the same manners he offers mere acquaintances, Edmund demands “silence” from her.

The first time I read this, all I could think was, “sad, unrequited Fanny.” Despite the lack of “tender gallantry” from Edmund, “her happiness sprung from being the friend with whom [he] could find repose.” I thought her as delusional as Caroline Bingley. In a moment of literary bewilderment, I was actually rooting for Henry Crawford. After all, he was so solicitous of Fanny when Edmund was not. But this being Austen, things are not what they seem. (You might think I would have learned from Wickham and Willoughby!)

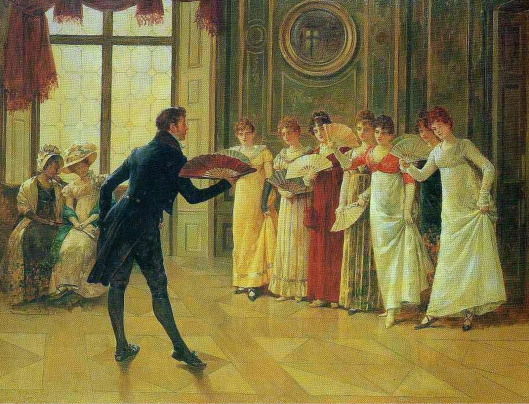

“Conducted by Mr. Crawford to the top of the room.” Illustration by C.E. Brock.

What I mistook as Fanny’s desperation is actually a sign from Austen that these two are perfectly suited. Edmund’s distress arises from Mary Crawford’s cruel, and repeated, belittling of his chosen vocation as a clergyman. He’s drawn to Mary but conflicted by a growing realization that she is not for him. “It was not her gaiety that could do him good: it rather sank than raised his comfort.” One can only imagine that if Austen had paired them off, Edmund would likely have retreated to his library for good like Mr. Bennet. Unlike the social-climbing Crawford siblings, Edmund and Fanny both seek a quieter path.

Still, I’ve always found it interesting that Austen gives this “worn out with civility” line to Edmund, in a moment of benign insensitivity. It would’ve had more brio (à la Lady Catherine de Bourgh) had it been delivered by the cruel Mrs. Norris or the callous Bertram sisters. Perhaps this is Austen’s way of indicting Edmund for standing by and letting his family treat Fanny so abominably for so long? Indeed, Fanny endures years of demeaning treatment from the Bertrams, and as a result, she is generally slighted by all her acquaintance.

But what makes the incivility so grueling in Mansfield Park, compared to other Austen novels, is that Fanny has no support system. Lizzie Bennet can confide in Jane, and, at a particularly low moment, her Aunt and Uncle Gardiner whisk her off to tour the countryside. Likewise, the Dashwood sisters have each other and their caring mother. Anne Elliot, though dismissed by her father and sister, has Lady Russell, Mrs. Smith, and the good opinion of her neighbors. Finally, Emma has her entourage. But Fanny is alone—a sort of Cinderella step-child, who for solace retreats to the abandoned attic schoolroom with its unlit fireplace. Nevertheless, Fanny’s good and gracious nature prevents her from growing bitter towards the Bertrams, or anyone. Instead, Fanny serves as a paragon of forbearance and civility. As such, she proves herself far superior to her cousins Maria and Julia Bertram despite the deliberate effort made to raise Fanny as their subordinate—another delicious Austen irony. Ultimately, Fanny comes to love and to bring out the good in the Bertrams.

While all turns right and perfectly happy for her, and for Edmund who sees the light, going through all this with Fanny quite puts one through the wringer. Indeed, Mansfield Park is best read with a restorative cup of tea in hand. Each time I close the book I cannot help but say, on Fanny’s behalf, “I am worn out with civility!”

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by John Baxter, Sharon Hamilton, and Sara Malton.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

October 31, 2014

Fanny Price, Mind Reader

Twenty-sixth in a series of guest posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

I’m very happy to introduce Joyce Tarpley’s post on Mansfield Park. Joyce teaches composition and literature full-time at Mountain View College in Dallas, Texas. She holds a Ph.D. in literature from the University of Dallas and has published a book on Mansfield Park titled Constancy and the Ethics of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park (Catholic University of America Press, 2010). These two essays also reflect her continuing interest in themes relating to males in Austen’s novels: “Sonship, Liberty, and Promise-Keeping in Sense and Sensibility,” published in Renascence: Essays in Values and Literature 63.2 (2011), and “Playing With Genesis: Sonship, Liberty, and Primogeniture in Sense and Sensibility,” published in Persuasions 33 (2011).

The fact that Jane Austen uses the word “mind” more times in Mansfield Park than in her other novels suggests a particular preoccupation with the way her characters think. (According to a search of the “Modern English Collection” on the University of Virginia Text Center website, the word “mind” appears 160 times in Mansfield Park compared to 135 in Emma, 104 in Sense and Sensibility, 69 in Northanger Abbey and Persuasion, and 64 in Pride and Prejudice.) Every Jane Austen novel features a kind of mind reading, or “people reading,” because she portrays each heroine, to different degrees, in the act of (1) discerning the “thoughts, feelings, desires, and intentions,”* of other people and (2) discovering the same things about herself. The rhetorical situation for the heroine’s mind reading in a Jane Austen novel includes a subject, a purpose, and an audience. The subject is reality, or the truth, about herself, about someone else, and about the situation in which the two interact. The purpose is to choose, rightly, how to think and act in response to this subject. The audience is the heroine herself, or her consciousness, which is where the mind reading takes place.

Some commentators have a different name for this process. James Wood, for example, uses hermeneutics to describe this skill of the Austen heroine in his article titled “The Birth of Inwardness: The Heroic Consciousness of Jane Austen.” Citing theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher, a contemporary of Austen’s who popularized hermeneutics for Bible study, Wood argues that “[s]omeone who understood other people, who attended to their secret meanings, who read people properly, might have been called hermeneutical” (The New Republic, August 17 & 24, 1998). It should come as no surprise that Fanny Price is the most hermeneutical of Austen’s heroines. She is the best mind reader because of her humility and persistence in attending to her own “thoughts, feelings, desires, and intentions” in an attempt to know herself. This self-knowledge forms the foundation upon which she draws accurate conclusions about – or readings of – the minds of others.

Fanny’s mind reading represents a synthesis. She uses her constancy, or integrity – what might be called her Christian-ethical perspective – as a filter that allows her to make sense of the disparate and contradictory data received through her senses. Aided by an incredibly retentive and accurate memory, this continuous process of reflection allows Fanny to “read” people accurately and to choose rightly how to respond to them.

But Fanny is not the only adept mind reader in Mansfield Park. Austen gives us two more examples with the Crawford siblings, both of whom are skilled at guessing the thoughts and feelings of others. Unlike Fanny, however, they use their powers to manipulate people rather than to understand or to help them. For example, reading Rushworth’s mind during the excursion to Sotherton allows Fanny to assuage his jealousy; reading Julia’s mind during the theatricals allows her to warn Edmund about his sister – even though he does not listen. Reading Edmund’s mind about Mary distresses her, and she censures herself for the jealous feelings that cause this distress. Perhaps the best example of Fanny’s mind reading, or at least the most important one for her happiness, is exemplified in the passage wherein she tries to calculate the thoughts, feelings, and intentions of Henry and Mary Crawford regarding his sudden seeming interest in marrying her:

Fanny, meanwhile, speaking only when she could not help it, was very earnestly trying to understand what Mr. and Miss Crawford were at. There was every thing in the world against their being serious, but his words and manner. Every thing natural, probable, reasonable was against it; all their habits and ways of thinking, and all her own demerits. – How could she have excited serious attachment in a man, who had seen so many, and been admired by so many, and flirted with so many, infinitely her superiors – who seemed so little open to serious impressions, even where pains had been taken to please him – who thought so slightly, so carelessly, so unfeelingly on all such points – who was every thing to every body, and seemed to find no one essential to him? – And further, how could it be supposed that his sister, with all her high and worldly notions of matrimony, would be forwarding any thing of a serious nature in such a quarter? Nothing could be more unnatural in either. Fanny was ashamed of her own doubts. Every thing might be possible rather than a serious attachment or serious approbation of it toward her.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 31 (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1988)

Fanny seeks to “read” the information being presented to her, “the words and manner” of Mr. Crawford, by testing the source of that information – its reliability, its integrity, and its motive. Both Crawfords fail the reliability test based on Fanny’s memory of their past actions, including their trifling treatment of three Bertram siblings: Maria, Julia, and Edmund. Her knowledge of their character also causes her to doubt their integrity. Although she cannot fathom what their motive might be, her own humility makes it impossible for her to believe Mr. Crawford could have any serious interest in her. Such an interest is as “unnatural” to Fanny as it would have been to readers earlier in the novel. Fanny’s conclusion is categorical; despite Henry’s “words and manner” there is no doubt in her mind that neither a “serious attachment nor serious approbation of it” could be possible.

Subsequent events prove that Fanny knows Henry better than he knows himself. Despite a temporary softening toward him, brought on by living in the depressing Portsmouth home of her parents, and despite wishful thinking on the part of many readers – and even the narrator* – Fanny’s initial reading of Henry is correct. His love for her, genuine though it may be, cannot change his character. Mary herself provides the best evidence that her brother is incapable of a long-term (let alone lifetime) marital commitment: “I know that a wife you loved would be the happiest of women and that even when you ceased to love she would yet find in you the liberality and good breeding of a gentleman.” Mary knows that Henry will eventually grow bored with Fanny, cease to love her, and trifle with other women as cavalierly – albeit discreetly and politely – as he commits adultery with Maria. Fanny’s mind reading allows her to discern the “secret meanings” of the Crawfords’ words and actions, meanings of which even they themselves are not fully aware. By contrast, the Crawfords’ lack of self-knowledge leads to their failure to read accurately the mind – thoughts, feelings, desires, and intentions – of Fanny Price.

Notes:

* This phrase comes from Lisa Zunshine’s article titled “Why Jane Austen Was Different, And Why We May Need Cognitive Science to See It” (Style 41.3 [2007] 275-98), in which she explains mind reading by reference to “theory of mind,” a concept that cognitive scientists and philosophers of mind use “interchangeably” with the term.

* For discussion and analysis of the narrator’s “tacit approval” of the Fanny/Henry marriage that might have been, see “Constancy: A Reading” in Constancy and the Ethics of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park, 50.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Sarah Woodberry, John Baxter, and Sharon Hamilton.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

October 28, 2014

Tea with JASNA Nova Scotia

The next JASNA Nova Scotia meeting will be on Sunday, November 9th, at 2 p.m., when we’ll meet in Halifax for tea, a short business meeting, and conversations about the 2014 JASNA AGM in Montreal. Please let Anne, our Regional Coordinator, know if you’re interested, or tell me (either by email – semsley at gmail dot com – or by leaving a comment here) and we’ll give you details about the location.

I’ve been rereading The Jane Austen Cookbook, by Maggie Black and Deirdre Le Faye, and I’m trying to decide whether to make “Mrs. Perrot’s Heart or Pound Cake” (“If you chuse Currants ¾ of a pound well washd & pick’d to be strew’d over them just as they are put into your Tins”), “Martha’s Gingerbread ‘Cakes’” (which we’d call biscuits or cookies, made with black treacle, or molasses), or “Ratafia Cakes” (ground almonds, egg whites, sugar, and orange liqueur).

Vote for your favourite in the comments below – even if you won’t be in Halifax on November 9th – and I’ll (attempt to!) make whichever recipe wins the popular vote.

October 24, 2014

On Turning Down Marriage Proposals

Twenty-seventh in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Syrie James, hailed as “the queen of nineteenth century re-imaginings” by Los Angeles Magazine, is the bestselling author of nine critically acclaimed novels, including Jane Austen’s First Love, The Missing Manuscript of Jane Austen, The Lost Memoirs of Jane Austen, The Secret Diaries of Charlotte Brontë, Dracula My Love, Nocturne, Forbidden, Songbird, and Propositions. Her books have been translated into eighteen languages, awarded the Audio Book Association Audie, designated as Editor’s Picks by Library Journal, named a Discover Great New Writers Selection by Barnes and Noble, a Great Group Read by the Women’s National Book Association, and Best Book of the Year by The Romance Reviews and Suspense Magazine.

Syrie James, hailed as “the queen of nineteenth century re-imaginings” by Los Angeles Magazine, is the bestselling author of nine critically acclaimed novels, including Jane Austen’s First Love, The Missing Manuscript of Jane Austen, The Lost Memoirs of Jane Austen, The Secret Diaries of Charlotte Brontë, Dracula My Love, Nocturne, Forbidden, Songbird, and Propositions. Her books have been translated into eighteen languages, awarded the Audio Book Association Audie, designated as Editor’s Picks by Library Journal, named a Discover Great New Writers Selection by Barnes and Noble, a Great Group Read by the Women’s National Book Association, and Best Book of the Year by The Romance Reviews and Suspense Magazine.

Syrie’s article “Jane’s First Love?” about Edward Taylor, a young man upon whom Jane Austen admittedly “fondly doated,” appeared in the July/August 2014 issue of Jane Austen’s Regency World Magazine. With Diana Birchall (whose guest post for “An Invitation to Mansfield Park” was called “The Scene-Painter”) Syrie co-wrote “The Austen Assizes” for the JASNA AGM in New York in 2012 and “A Dangerous Intimacy: Behind the Scenes at Mansfield Park” for the Montreal AGM last month. Syrie is a life member of the WGA and JASNA and lives in Los Angeles. You can find her on Facebook, Twitter, and at syriejames.com.

On their way to Montreal, Syrie and her husband took a cruise from Boston to Quebec City, and when they stopped in Halifax, I got to have the pleasure of showing them around the city on a glorious fall day. We started at the Public Gardens, where the dahlia garden was a highlight, and then toured the Citadel, from which we enjoyed the fantastic views of the city and the harbour. A couple of weeks later, we explored the Montreal Botanical Garden together on an equally beautiful fall day. Syrie and I share a fascination with the strength of character Fanny Price demonstrates when she resists the attempts of all her relatives and friends to persuade her to marry Henry Crawford.

Montreal Botanical Garden

“Am I to understand,” said Sir Thomas, after a few moments’ silence, “that you mean to refuse Mr. Crawford?”

“Refuse him?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Refuse Mr. Crawford! Upon what plea? For what reason?”

“I – I cannot like him, sir, well enough to marry him.”

“This is very strange!” said Sir Thomas, in a voice of calm displeasure. “There is something in this which my comprehension does not reach. Here is a young man wishing to pay his addresses to you, with everything to recommend him: not merely situation in life, fortune, and character, but with more than common agreeableness, with address and conversation pleasing to everybody. And he is not an acquaintance of to-day; you have now known him some time. His sister, moreover, is your intimate friend, and he has been doing that for your brother, which I should suppose would have been almost sufficient recommendation to you, had there been no other. It is very uncertain when my interest might have got William on. He has done it already.”

“Yes,” said Fanny, in a faint voice, and looking down with fresh shame; and she did feel almost ashamed of herself, after such a picture as her uncle had drawn, for not liking Mr. Crawford.

“You must have been aware,” continued Sir Thomas presently, “you must have been some time aware of a particularity in Mr. Crawford’s manners to you. This cannot have taken you by surprise. You must have observed his attentions; and though you always received them very properly (I have no accusation to make on that head), I never perceived them to be unpleasant to you. I am half inclined to think, Fanny, that you do not quite know your own feelings.”

“Oh yes, sir! indeed I do. His attentions were always – what I did not like.”

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 32 (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1892)

From the Little, Brown and Company edition of Mansfield Park, 1892.

I admire Fanny Price, and nowhere more than in this scene, where – although greatly distressed – she refuses to marry Henry Crawford, despite the angry disapproval of her uncle.

The hallmark of every Jane Austen novel is the contrast between superficial appearances and true character – the ultimate lessons being that first impressions can be misleading, surface qualities are not real, and a person’s deeds, not their words, are the true window to their moral character.

This theme is prevalent in every page of Mansfield Park, where everyone except Fanny seems to be blinded by appearances. Even we, the reader, are blinded on a first perusal of the novel. Fanny appears to be frustratingly mousy and timid, while Mary and Henry Crawford at first glance are far more charming and interesting. But when all is said and done, we realize that Fanny is not mousy at all.

Illustration by Hugh Thomson.

I love Fanny because she stands up for what she believes in and won’t let anyone persuade her to do otherwise. Most young ladies in her position, I think, would have accepted Henry Crawford in a heartbeat. Fanny is a poor relation, with apparently few if any marital prospects. Henry is handsome, rich, and charming, and he showers her with attention. Everyone at Mansfield Park wants Fanny to marry Henry – Sir Thomas is adamant, Mary expects it, and even Edmund thinks it’s a good idea – and I bet most readers are at first rooting for that connection. (I know I did on my first reading!) Jane’s sister Cassandra apparently campaigned to have Fanny marry Henry, a suggestion Jane thankfully did not follow.

But Fanny, unlike everyone else, is perceptive enough to see the real man beneath the charade. “I am so perfectly convinced that I could never make him happy, and that I should be miserable myself,” a weeping Fanny tells Sir Thomas. She, alone, knows Henry to be a callous flirt who finds “no one essential to him” and whose habits are such “that he could do nothing without a mixture of evil.” Henry calculatingly preys on Fanny’s feelings by arranging for her brother William’s promotion, immediately following this news with a marriage proposal. Fanny sees Henry’s romantic overtures “all as nonsense, as mere trifling and gallantry, which meant only to deceive for the hour” – and with good reason. When Henry’s personal challenge to win Fanny fails, he succumbs to his darker nature and runs off with Mrs. Rushworth.

Fanny refuses Henry Crawford’s proposal because she doesn’t love or respect him, and knows he cannot love her in return. No doubt, Jane Austen was drawing on her own personal experience when writing this sequence. As every Janeite knows, Jane famously accepted her one known marriage proposal from Harris Bigg-Wither, a wealthy, stuttering young man five years her junior who she’d known since childhood, only to recant the next morning.

There were many reasons why Jane might have felt compelled to marry Harris. The Austens were very close with the Bigg-Withers; Alethea and Catherine Bigg, Harris’s sisters, were two of Jane’s dearest friends. At age twenty-seven, Jane was already considered a spinster – and as Sir Thomas says to Fanny, you are “throwing away from you such an opportunity of being settled in life, eligibly, honourably, nobly settled, as will, probably, never occur to you again.” Indeed, by marrying Harris, Jane would have become the future mistress of Manydown Park, a large Hampshire house and estate in the neighborhood she loved, and where she had grown up. Marrying Harris would have given financial security to Jane and her parents and Cassandra for the rest of their lives.

Manydown Park

But Jane didn’t love Harris – perhaps didn’t even like him very much. And as Jane wrote in her unfinished novel The Watsons, “To pursue a man merely for the sake of situation, is a sort of thing that shocks me; I cannot understand it. Poverty is a great evil; but to a woman of education and feeling it ought not, it cannot be the greatest. I would rather be teacher at a school (and I can think of nothing worse) than marry a man I did not like.”

Illustration by Hugh Thomson

Only imagine what Jane must have felt – the deep emotional struggle she must have endured during that long, sleepless night after Harris’s proposal, as she agonized over her decision – and the pain and mortification of announcing that she could not marry Harris after all. Did Jane’s mother and father sharply criticize her decision when she rushed back to Bath? Were they as unfeeling as Sir Thomas was to Fanny? We do not know.

One thing is certain: Jane didn’t listen to what anyone else wanted. She followed her own heart and conscience, and demonstrated great inner strength and courage when she turned down Harris’s proposal, just as Fanny does when she refuses Henry Crawford. I admire them both for the choice they made. In this scene in Mansfield Park, Jane Austen is telling us something important: that she admires Fanny Price, because she possesses the moral conviction, good sense, and strength of character required of a true heroine.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Joyce Tarpley, Sarah Woodberry, and John Baxter.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

October 21, 2014

Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Mansfield Park

I was so excited when my copies of the new MLA (Modern Language Association) volume Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Mansfield Park arrived at my house yesterday. I’ve mentioned the book and my essay on “The Tragic Action of Mansfield Park” here before, and I did get to see it for the first time at the JASNA AGM in Montreal, but I now have my very own copies. The paperback cover features a painting called “Fond Memories,” by Charles Haigh Wood, and the cloth edition is a very pleasing dark purple. (That looks very much like Mary Crawford and Fanny Price to me – what do you think? Mary gazing at her own reflection in a pocket mirror, while Fanny sits with her hands clasped, looking up at Mary and figuring out what to make of her character.)

It was more than nine years ago that I first started to write about why Mansfield Park is a tragedy. I presented the first version of my essay at the 2006 JASNA AGM in Tucson, Arizona, after which it was published in Persuasions On-Line (you can still read that early version here). Later, I was delighted when it was accepted for publication in the volume of essays Marcia McClintock Folsom and John Wiltshire were editing for the MLA series. I had long been an admirer of Marcia’s previous books, Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Pride and Prejudice and Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Emma, and of John Wiltshire’s work on Austen, especially his books Jane Austen and the Body and Recreating Jane Austen and his Cambridge edition of Mansfield Park.

If you’re interested, you can read more about Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Mansfield Park and the topics covered by the editors and contributors on the MLA website.

And if you’d like to know more about my essay, you might be interested in this blog post I wrote earlier this year, on why “Mansfield Park is a Tragedy, Not a Comedy.”

I’m looking forward to reading the essays by Marcia and John and all the other contributors. I’m particularly intrigued by the titles of the essays by Pamela Bromberg – “Mansfield Park: Austen’s Most Teachable Novel” – and Peter Graham – “Ambiguities of the Crawfords.” Back when I taught classes on Jane Austen in the Writing Program at Harvard College, I enjoyed moving from the “light, and bright, and sparkling” world of Pride and Prejudice to the sometimes shocking world of Lady Susan and then, at the end of the semester, to the dark and complicated world of Mansfield Park.

I’m already persuaded that this one is the most “teachable” of the novels, and I’m keen to learn new approaches to understanding Mansfield Park, even though I’m not currently teaching in an academic institution. As Jennifer Weinbrecht of Jane Austen Books mentioned on Facebook when I posted the news about the book last night, “One doesn’t need to be a teacher to enjoy reading these books,” because “It’s always fun to gain new insights and discover new ways to think about our favorite works.” Well said, Jennifer!

October 18, 2014

The Custom of the Country Turns 101 Today

Today is the 101st anniversary of the publication of Edith Wharton’s novel The Custom of the Country. She called it her “Big Novel,” and her biographer Hermione Lee calls it her “greatest book.”

First edition of The Custom of the Country

Last year, to celebrate the 100th anniversary, I wrote a series of ten blog posts about the novel, its unforgettable (anti-)heroine Undine Spragg, and the changes Wharton made to the text between the version that was serialized in Scribner’s Magazine and the publication of the first edition on October 18, 1913.

On my page “The Custom of the Country at 100,” you can find links to all the posts in my series, plus links to several other essays on The Custom of the Country published elsewhere on the web – including one by Margaret Drabble, who calls the novel “one of the most enjoyable great novels ever written.” (And of course you can find out more about the edition of the novel that I prepared for the Broadview Literary Texts series.)

My Broadview edition of The Custom of the Country

I wrote, for example, about how my interest in local history, and a trip to the Halifax Citadel, led to my discovery of this fantastic novel. I talked about the source of , and traced connections from Undine to Lorelei Lee, Marilyn Monroe, and Madonna (“diamonds are a girl’s best friend”). I also explored Wharton’s influence on Candace Bushnell and Julian Fellowes. And there are several more posts – I hope you enjoy reading (or rereading) them.

Undine’s restless ambition is endlessly fascinating. I’ve always thought the best line in the novel is this one: “There was something still better beyond, then – more luxurious, more exciting, more worthy of her!” She’s never, ever satisfied, no matter how much money or power she has.

It was great to hear the news last week that Scarlett Johansson will star as Undine in a new television adaptation of the novel. I do think being a movie star might well be “the one part [Undine] was really made for” (to quote a line from the novel out of context).

I had such a great time putting together this celebration of The Custom of the Country last year that I decided to do something similar to celebrate the 200th anniversary of Mansfield Park – and we all know how that turned out! Instead of writing ten posts myself, I’m hosting a huge party for Mansfield Park, and now there are more than forty contributors writing guest posts. (Here’s your “Invitation to Mansfield Park,” for anyone who hasn’t received it yet.) I think Undine Spragg would be quite jealous that Fanny Price’s party is bigger than hers was. But then, Undine was celebrating only 100 years last year, not 200.

Happy 101st birthday to Undine Spragg and The Custom of the Country!

October 17, 2014

The Comfort of Friendship

Twenty-fourth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Margaret Horwitz specializes in Film Studies, and has given many talks on Jane Austen’s novels and their film and television adaptations. She spoke at the JASNA AGMs in Los Angeles (2004) and Chicago (2008), and was JASNA’s Traveling Lecturer for the western part of North America in 2008-2009. She has a Ph.D. in Film Studies from UCLA and is a visiting professor of literature for New College Berkeley, an institute of the Graduate Theological Union. She’s a Life Member of JASNA and has been active in JASNA circles since the mid-1990s, first in Southern and then Northern California.

I met Margaret at the 2005 AGM in Milwaukee, where we discovered that we share an interest in the prayers Jane Austen wrote, and in questions about ethics in Austen’s novels. It was wonderful to see her in Montreal last weekend at the Mansfield Park AGM, and I’m very pleased to introduce her guest post on Fanny Price’s feelings about the two necklaces given to her by Mary Crawford and Edmund Bertram.

“Oh, this is beautiful, indeed!” Illustration by C.E. Brock.

“Dearest Fanny!” cried Edmund, pressing her hand to his lips with almost as much warmth as if it had been Miss Crawford’s, “you are all considerate thought! But it is unnecessary here. The time will never come. No such time as you allude to will ever come. I begin to think it most improbable: the chances grow less and less; and even if it should, there will be nothing to be remembered by either you or me that we need be afraid of, for I can never be ashamed of my own scruples; and if they are removed, it must be by changes that will only raise her character the more by the recollection of the faults she once had. You are the only being upon earth to whom I should say what I have said; but you have always known my opinion of her; you can bear me witness, Fanny, that I have never been blinded. How many a time have we talked over her little errors! You need not fear me; I have almost given up every serious idea of her; but I must be a blockhead indeed, if, whatever befell me, I could think of your kindness and sympathy without the sincerest gratitude.”

He had said enough to shake the experience of eighteen. He had said enough to give Fanny some happier feelings than she had lately known, and with a brighter look, she answered, “Yes, cousin, I am convinced that you would be incapable of anything else, though perhaps some might not. I cannot be afraid of hearing anything you wish to say. Do not check yourself. Tell me whatever you like.”

They were now on the second floor, and the appearance of a housemaid prevented any farther conversation. For Fanny’s present comfort it was concluded, perhaps, at the happiest moment: had he been able to talk another five minutes, there is no saying that he might not have talked away all Miss Crawford’s faults and his own despondence. But as it was, they parted with looks on his side of grateful affection, and with some very precious sensations on hers. She had felt nothing like it for hours. Since the first joy from Mr. Crawford’s note to William had worn away, she had been in a state absolutely the reverse; there had been no comfort around, no hope within her. Now everything was smiling. William’s good fortune returned again upon her mind, and seemed of greater value than at first. The ball, too – such an evening of pleasure before her! It was now a real animation; and she began to dress for it with much of the happy flutter which belongs to a ball. All went well: she did not dislike her own looks; and when she came to the necklaces again, her good fortune seemed complete, for upon trial the one given her by Miss Crawford would by no means go through the ring of the cross. She had, to oblige Edmund, resolved to wear it; but it was too large for the purpose. His, therefore, must be worn; and having, with delightful feelings, joined the chain and the cross – those memorials of the two most beloved of her heart, those dearest tokens so formed for each other by everything real and imaginary – and put them round her neck, and seen and felt how full of William and Edmund they were, she was able, without an effort, to resolve on wearing Miss Crawford’s necklace too. She acknowledged it to be right. Miss Crawford had a claim; and when it was no longer to encroach on, to interfere with the stronger claims, the truer kindness of another, she could do her justice even with pleasure to herself. The necklace really looked very well; and Fanny left her room at last, comfortably satisfied with herself and all about her.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 27 (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003)

This passage from Chapter 27 of Mansfield Park intrigues me because it illustrates the power and comfort of friendship, and includes one of the most compelling moments in the novel. The setting of the passage begins near a staircase, and recalls a scene in Chapter 2 where Edmund Bertram notices the “despondence” of his ten-year-old cousin Fanny Price, shortly after her arrival at Mansfield Park. Edmund, who is six years older than Fanny, comforts her, while sitting next to her on the attic stairs. He then helps her write a letter to her brother William, who had been her advocate at home in Portsmouth. From the first recorded conversation between Fanny and Edmund, he and William are linked in their friendship with her.

This passage from Chapter 27 of Mansfield Park intrigues me because it illustrates the power and comfort of friendship, and includes one of the most compelling moments in the novel. The setting of the passage begins near a staircase, and recalls a scene in Chapter 2 where Edmund Bertram notices the “despondence” of his ten-year-old cousin Fanny Price, shortly after her arrival at Mansfield Park. Edmund, who is six years older than Fanny, comforts her, while sitting next to her on the attic stairs. He then helps her write a letter to her brother William, who had been her advocate at home in Portsmouth. From the first recorded conversation between Fanny and Edmund, he and William are linked in their friendship with her.

In Chapter 27, Fanny is now eighteen, and on the afternoon of the ball in her honor, a role reversal occurs in her friendship with Edmund. Though having cautioned him that she would not be an “adviser,” Fanny has agreed to be a “listener” as he struggles with uncertainty over the question of marriage to Mary Crawford. Edmund asserts, “I can never be ashamed of my own scruples,” in other words, the principles he has taught Fanny and which they now share. Edmund believes that “if they are removed” it must be by changes “in Miss Crawford’s conduct.” Yet his scruples have been to an extent diminished, since Edmund refers to Mary Crawford’s errors as “little,” though she has tried to convince him to renounce his calling as a clergyman.

Edmund acknowledges the unique place Fanny has in his life by saying, “You are the only being upon earth to whom I should say what I have said.” In spite of his many material advantages, she is the one person in whom he can confide. Fanny is then able to reply to Edmund with a “brighter look,” that she is convinced he would “be incapable of anything else” (adhering to his principles) though “some might not,” an indirect reference to Mary Crawford. This praise shows Fanny’s mettle as a friend to Edmund, since she expresses her faith in the strength of his character, though he is in love with and confused by her (unacknowledged) rival. In this way, Fanny also predicts the behavior of both Edmund and Mary Crawford.

Their conversation concludes before Edmund might “talk away all Miss Crawford’s faults” and his own “despondence,” the same word used for Fanny’s state of mind in Chapter 2. The role reversal in this passage continues because Edmund is now the recipient of Fanny’s kindness as they part ways, “with looks on his side of grateful affection,” in contrast to the pattern of his being kind and Fanny responding with gratitude. He also has affirmed her. From a place of “no comfort around” and “no hope within her,” Fanny can anticipate the ball that night as an “evening of pleasure,” instead of anxiety.

One of the most satisfying moments in the novel takes place when Fanny goes into her room to dress for the ball. Her “good fortune seemed complete,” when the ornate necklace Mary Crawford has given her cannot go through “the ring of the cross,” a gift to Fanny from William. The “plain gold chain” Edmund had just given her the prior evening “must be worn,” though he has urged her to wear the more elaborate necklace, in order to please Miss Crawford. The necklace, originally a gift to Mary from her brother, Henry Crawford, was imposed on Fanny with the injunction that she remember both of them in wearing it. In this instance, Fanny successfully navigates a series of competing claims. She is able to have her preference, “and with delightful feelings” to join “the chain and the cross, those memorials of the two most beloved of her heart, those dearest tokens.”

One of the most satisfying moments in the novel takes place when Fanny goes into her room to dress for the ball. Her “good fortune seemed complete,” when the ornate necklace Mary Crawford has given her cannot go through “the ring of the cross,” a gift to Fanny from William. The “plain gold chain” Edmund had just given her the prior evening “must be worn,” though he has urged her to wear the more elaborate necklace, in order to please Miss Crawford. The necklace, originally a gift to Mary from her brother, Henry Crawford, was imposed on Fanny with the injunction that she remember both of them in wearing it. In this instance, Fanny successfully navigates a series of competing claims. She is able to have her preference, “and with delightful feelings” to join “the chain and the cross, those memorials of the two most beloved of her heart, those dearest tokens.”

It makes sense that William and Edmund, Fanny’s closest friends as well as family members, honor her character and her taste, so that the chain and cross seem “formed for each other.” The chain’s simplicity is appropriate for Fanny’s integrity. The cross represents love and sacrifice in William’s purchasing a costly present, one which also recognizes Fanny as a person of faith.

Finally, unlike Mary Crawford’s necklace, Edmund’s gold chain is not given to her in the service of another relationship. He remembers what would be helpful to Fanny, something important to her comfort. Edmund has indeed shown himself to have a “truer kindness” than Mary Crawford, who has forced a gift on her. In addition to the chain and cross, Fanny makes the decision to wear Miss Crawford’s necklace, and even thinks it “really looked very well.” She leaves her room for the ball, “comfortably satisfied with herself and all about her.” Edmund’s friendship, and his response to her friendship, result in a rare moment of comfort for Fanny, who is undervalued and forgotten throughout much of the novel.

This passage reveals Edmund’s need for Fanny to listen to his conflicting feelings, as his sole confidante. Fanny is a steadfast friend in encouraging him to hold fast to his principles. Edmund’s ability to do so in the long run derives at least in part from their friendship as an important touchstone in his life. His unalloyed kindness to Fanny, in realizing her need for a chain to support William’s cross, is rewarded by these gifts complementing each other. The gift of a cross, itself a symbol of sacrificial love, also reveals William’s faithfulness in remembering Fanny as a sibling and friend during her eight years of separation from their childhood home. Though she still has much pain to endure, including Edmund’s wavering, I find this scene a high point in the novel. For once, Fanny “must” do what she most wishes, to unite these objects, “full of William and Edmund,” and by implication the two persons “dearest” to her comfort.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Sarah Woodberry, Joyce Tarpley, Syrie James, and John Baxter.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

October 16, 2014

Listening to Mansfield Park

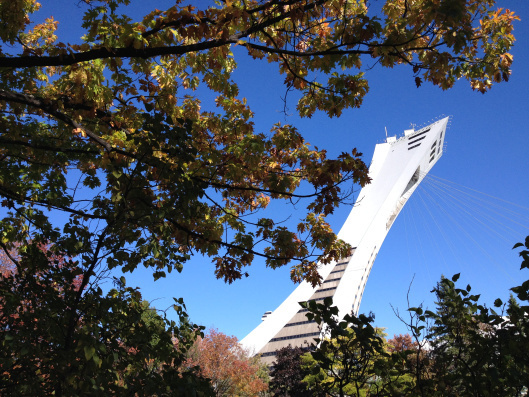

One of the many highlights of this year’s JASNA AGM in Montreal was definitely Lynn Festa’s plenary session on “The Noise in Mansfield Park,” in which she showed us why this novel is Jane Austen’s “noisiest book.” Fanny Price may appear to be a quiet heroine, but both her interior life and her exterior surroundings are anything but peaceful. Lynn talked about how “it’s very difficult to quote noise” because it’s something we hear, but don’t really listen to. In Mansfield Park, she suggested, Austen asks us to pay close attention to noise, to listen carefully.

The view from Mount Royal

It really was a fabulous weekend of listening to people talk about Mansfield Park, just as I expected it to be. (Here’s last week’s blog post on “Mansfield Park in Montreal,” with details about things I was looking forward to.) It was great to meet up with several of the contributors to “An Invitation to Mansfield Park,” some of whom I met in person for the first time, after many conversations on-line. Many of our JASNA Nova Scotia members went to this year’s AGM, too.

It was a pleasure to attend talks by so many excellent speakers, including Juliet McMaster on “Female Difficulties: Austen’s Fanny and Burney’s Juliet,” Lorrie Clark on “Giving Mr. Rushworth a Brain: Austen Re-Minds Modernity,” Peter Graham on “‘Every generation has its improvements’: The Aesthetics and Ethics of Domestic Space,” Natasha and Frederick Duquette on “Fanny Price Amidst the Philosophers,” and Marcia Folsom, who introduced the new MLA volume Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Mansfield Park.

I’m very excited about this new book (and not just because it includes my essay on Mansfield Park and tragedy).

The food at the banquet (including an apricot tart for dessert, because “a good apricot is eatable”) was excellent and it was a delight, as always, to see people in period costume at the Regency Ball.

St George’s Anglican Church

Many of us went to Morning Prayer at St. George’s Anglican Church on Sunday morning (“A whole family assembling regularly for the purpose of prayer is fine!”), which was followed by brunch and a very entertaining talk on the Georgian Royal Navy by Patrick Stokes, former Chairman of the Jane Austen Society (UK) and a direct descendant of Jane Austen’s “own particular little brother,” Rear-Admiral Charles Austen.

Patrick Stokes

“A Dangerous Intimacy: Behind the Scenes at Mansfield Park,” the play by Diana Birchall and Syrie James, was hilarious, and included not one but two surprise appearances at the end – the first by Bill James as Sir Thomas Bertram, and the second by Patrick Stokes as the Prince Regent. In her role as Mrs. Norris, Diana not only brought out the infamous green baize fabric, but also wore it, complete with a curtain rod.

The cast of “A Dangerous Intimacy: Behind the Scenes at Mansfield Park.” Thanks to Erna Arnesen and Diana Birchall for the photo.

I’m very grateful to Elaine Bander and her team for welcoming us to Montreal to celebrate Jane Austen and Mansfield Park. It was a wonderful weekend of good company and a great deal of conversation. I love that the beautiful tote bags for this AGM were handmade in India by women whose work is supported by April Cornell’s The Giving World Foundation.

The AGM tote bags came in a variety of cotton prints, and I was very pleased with mine.

And, after spending so much time inside at the conference hotel, I really enjoyed the chance to explore Montreal, especially the Botanical Garden and Mount Royal.

The Chinese Garden at the Montreal Botanical Garden

I’m glad that the celebrations of two hundred years of Mansfield Park aren’t over quite yet, and that I can look forward to reading several more contributions to my blog post series “An Invitation to Mansfield Park” this fall. (Coming soon: guest posts by Margaret Horwitz – tomorrow – and by Sarah Woodberry, Joyce Tarpley, Syrie James, John Baxter, Sharon Hamilton, Sara Malton, and many more. Please do subscribe to the blog, if you haven’t already, so you don’t miss any of their posts.)

I’m going to keep listening to Juliet Stevenson reading Mansfield Park over the coming weeks, too – listening to audiobooks always helps me slow down and attend to the details of Austen’s language. I’m also keen to read conference papers from this year’s AGM when they’re published in Persuasions and Persuasions On-Line.

The Olympic Park Tower

And there are future AGMs to look forward to: “Living in Jane Austen’s World” in Louisville, Kentucky, with Inger Brodey, Rachel M. Brownstein, and Amanda Vickery as plenary speakers (October 9-11, 2015), and “Emma at 200: ‘No One But Herself’” in Washington, DC (October 21-23, 2016). Thanks, JASNA. It’s a pleasure to listen to, and participate in, conversations about Jane Austen.

October 10, 2014

Fanny Price’s Prayers

Twenty-third in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Today is the first official day of the JASNA AGM in Montreal, where seven hundred of us are gathering to discuss and celebrate Mansfield Park. This weekend I get to have the pleasure of introducing Natasha Duquette and her work on Austen on two occasions. Tomorrow I’m introducing the AGM breakout session she and her husband Frederick Duquette are presenting on “Fanny Price Amidst the Philosophers,” and right now I get to introduce her guest post on Fanny’s “fervent prayers.”

Natasha and I attended the University of Alberta as undergraduates at the same time, but somehow we didn’t meet until several years later (at a conference in London, Ontario, even though – as we recently figured out – we took the same Chaucer class together at the U of A). It’s been a delight to reconnect with her and to discuss Mansfield Park.

Natasha and I attended the University of Alberta as undergraduates at the same time, but somehow we didn’t meet until several years later (at a conference in London, Ontario, even though – as we recently figured out – we took the same Chaucer class together at the U of A). It’s been a delight to reconnect with her and to discuss Mansfield Park.

Natasha is Associate Dean at Tyndale University College in Toronto, Ontario, where she also teaches in the Philosophy and English departments. Her research on Jane Austen has appeared in Jane Austen Sings the Blues (University of Alberta Press, 2009), Persuasions On-Line, and English Studies in Canada, and she co-edited – with Elisabeth Lenckos, whose guest post on Mansfield Park will appear in this series in December – Jane Austen and the Arts: Elegance, Propriety, and Harmony (Lehigh University Press, 2013). Natasha’s monograph Veiled Intent: Dissenting Women’s Theological Aesthetics is forthcoming with Pickwick.

He would marry Miss Crawford. It was a stab, in spite of every longstanding expectation; and she was obliged to repeat again and again that she was one of his dearest, before the words gave her any sensation. Could she believe Miss Crawford to deserve him, it would be – Oh, how different it would be – how far more tolerable! But he was deceived in her: he gave her merits which she had not; her faults were what they had ever been, but he saw them no longer. Till she had shed many tears over this deception, Fanny could not subdue her agitation; and the dejection which followed could only be relieved by fervent prayers for his happiness.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 27 (Peterborough, ON: Broadview, 2003)

Fanny Price is the only heroine who Jane Austen depicts in an act of private prayer. This small window into Fanny’s spiritual life is in accord with Austen’s general depiction of her as a contemplative. In her excellent study Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues (Palgrave, 2005), Sarah Emsley presents Fanny as a deep thinker engaged in “philosophical contemplation” (108), and I have argued Fanny’s observation of the starry sky over dark woods is a moment of contemplative sublimity (“Sublime Repose”: The Spiritual Aesthetics of Landscape in Austen” in Jane Austen Sings the Blues, 2009).

Like contemplative women through history – such as scientist and theologian Hildegaard of Bingen and phenomenologist Edith Stein – Fanny Price blends intellectual, philosophical, and spiritual contemplation in her figurative convent cell, the East Room of Mansfield Park. But unlike the idealized sisters of Williams Wordsworth’s sonnet “Nuns Fret Not,” the very human Fanny does balk at the limitations of a solitary, celibate future.

“Nun from Lavater,” an illustration in Mary Anne Schimmelpenninck’s Theory on the Classification of Beauty and Deformity (London: John & Arthur Arch, 1815). Thanks to Chawton House Librarian Charlotte Falconer for capturing this image.

Edmund Bertram’s apparent choice of Mary Crawford frustrates Fanny, and in response, she redirects her passion in spontaneous, almost Psalmic, cries of the heart. Like the biblical psalmist, Fanny wonders at the “prosperity of the wicked” (Psalm 73.3, KJV), and her fervent prayers are anguished and ardent petitions. Within the narrative framework of Mansfield Park, Fanny cannot initially accept the reality of Edmund’s attraction to Mary, despite the evidence she sees.

However, when Edmund tells Fanny that she and Mary are his “dearest objects,” Fanny quickly jumps to the conclusion that Edmund will wed Mary. Edmund’s statement breaks through any remaining layers of denial in her consciousness, and Fanny experiences harsh reality physically – “it was a stab.” Austen avoids simile and uses a powerful direct metaphor. It is not as if Fanny has been stabbed. She was stabbed. She feels it acutely. Stages of grief appear in rapid succession: shocked numbness marked by absence of “any sensation,” outrage emphasized with an exclamation mark, bafflement, weeping, and finally “dejection.” Paradoxically, this final stage functions as a turning point for Fanny, a pivot upwards towards faith and hope for “happiness” (Edmund’s, at least, if not her own). Fanny’s Psalmic descent will turn out to be a felix culpa or “happy fall.” It is a journey into the darkest aspects of her self – envy, judgment, rage, & doubt – with a redemptive twist at the end.

Upon re-visiting Mansfield Park for a second or third time, the reader may bring dramatic irony to Fanny’s impassioned prayers. They have a comic aspect in their very fervency. Fanny is far from perfect herself and very much a character in process of dynamic development. Her interpretation of Edmund’s statement as definitely indicating “he would marry Miss Crawford” is lacking in epistemological humility. Fanny is not omniscient, nor is the narrator, and her fatalistic, certain prediction of Edmund’s matrimonial future appears in a moment of free indirect discourse. Thankfully, the narrator is unreliable and fallible, the future is still open, and Fanny’s prayers will be answered in ways beyond anything she could ask or imagine.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Margaret Horwitz, Sarah Woodberry, Joyce Tarpley, and Syrie James.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

October 7, 2014

The Scene-Painter, Part Two

As I promised in yesterday’s blog post, “Mansfield Park in Montreal,” I’m posting the second part of Diana Birchall’s “The Scene-Painter,” in which she imagines the details of the story that lies behind Jane Austen’s brief reference in Chapter 20 of Mansfield Park to the man who leaves the house having “spoilt only the floor of one room, ruined all the coachman’s sponges, and made five of the under-servants idle and dissatisfied.” You can find Part One of “The Scene-Painter” here.

And if you’re going to be in Montreal this weekend for the JASNA AGM, you’ll be able to see another of Diana’s explorations of what’s “behind the scenes” at Mansfield Park, if you come to the play she and Syrie James co-wrote and are co-producing, “A Dangerous Intimacy.”

It did not appear, in succeeding days, that Edmund had influenced Tom in the slightest. The scene-painter spent hours in his chamber, and as Edmund had prophesied, it became a place where the maids and men of the house congregated, joined at all hours by Tom and Yates. Drinking went on and laughter was heard late at night, much to Fanny’s alarm, but as her cousin Tom was at the center of the revelry, she would not be afraid for her own safety, and did not like to speak of the matter. She was aware that any complaint would bring the wrath of Edmund, and she shrank from being the occasion for any high words between the brothers.

Sometimes the doings in Sharp’s rooms went on very late indeed, and then he slept much of the next day, so that the painting was going on very slowly. Perhaps, as he was being paid by the day, that was his intent; but it was the only aspect of the scene-painter’s residence that at all troubled Tom.

“If we don’t get forwarder with the scenes, our theater never will be complete,” he fretted. “Can’t you hurry it up a bit, Sharp?”

“Oh, art takes time to develop,” he said easily. “Never you fear, Tom, we will have a brilliant production. We cannot fail.”

Sharp was, like Tom, a talker, but his topics ranged farther than Tom’s usual gossip about people in town and the horses he was racing. Sharp professed to be interested in ideas, and finding a receptive audience among the maids and men, he was soon lecturing Sarah and Ellen, as well as the three young menservants who were moths to his candle, and loved to hear about the revolutionary new social currents and their spread in enlightened London circles.

“Only think, the shops and the picture-galleries, and going to the theatre every day. How grand London must be!” exclaimed Sarah, a fair-haired eighteen-year-old with round cheeks.

“And all the fine talking, the salons and coffee-houses Mr. Sharp speaks of. Oh, how I do long to see it all!” sighed pretty Ellen, her bright brown eyes aglow.

“Oh, quite. You must go there. It is only in these slow country places that people are so hidebound and old-fashioned. Quite intolerable. Buried here, you have no idea what freedom really is.”

“But if things are so very free, don’t the girls get into – trouble, Mr. Sharp?” Ellen asked hesitatingly.

“To be sure they do, sometimes, but that happens everywhere, in the country as well as the city, and thinking people don’t pay any heed. They know that women have as good minds, and capacities, as men, and ought not to be only mothers, but valued for their work. Have you never read Mary Wollstonecraft, Ellen?”

“No; who is she?”

“Why, she is one of the finest women writers and thinkers that ever lived. Wrote a book called A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, and you ought to read it, and learn all about your natural rights. Every woman should. She didn’t bother with marriage, when having her children, I can tell you, but thought and acted like a man.”

“What happened to her, Mr. Sharp?” Ellen asked breathlessly.

“Well, she did marry in the end, to Godwin, the enlightened philosopher. Perhaps you have heard of him? No? – and then, well, she died,” he said. “But surely you girls don’t want to be kept down, in service. In the city, you can always find something to do, and a clever woman can make or marry a fortune.”

“What about men?” asked Rufus, the second footman, a strapping young fellow who spent his days arranging Lady Bertram’s shawls and walking her Pug. “I have sometimes thought I might do better in London, than in service.”

“No doubt of that,” Sharp assured him, “there are so many more chances in town. And after all, man, service is degrading! There’s no reason at all, you know, why one set of people should be masters, and others slaves.”

“Slaves!” exclaimed Tom jovially. “We pay all our people very well, I’ll have you know, Sharp.”

The men fell silent, but Sarah said thoughtfully, “But Mr. Sharp, isn’t it in the Bible, that we are to be content, in whatever state of life we have been called?”

“My dear Sarah, we are living in the nineteenth century,” he said kindly. “There has been a revolution in America, and in France. All men are created equal, you know. Have you not read Tom Paine and his Rights of Man? It is the right of every man, and woman too, to seek happiness, and do the best for himself he possibly can, without knocking under to other people.”

“That sounds fine to me,” said Samuel, the boot-blacking boy, his eyes glowing. “Do you think I might get a job in the theatre in London, and be an actor?”

“Why not? You’re a good-looking lad, and you are welcome to stay in my quarters whenever you do make your way to London.”

“See here, Tom, he’s going to have all your servants departing your employ at once,” laughed Yates.

Tom scoffed at that. “Phoo, phoo. Our people know when they’re well off. We don’t oppress any body at Mansfield Park, I can tell you, Sharp.”

“No, of course not. But servants are not always so fortunate in their masters as yours are. When you consider political justice, Bertram, you must admit that aristocratic privilege is a pernicious thing.”

“I agree that society must be changed,” drawled Yates, “certain sure. Nobody ever has enough money, that I can see. I know I have not.”

“If we don’t change our institutions voluntarily, they must be completely overthrown. Peaceably, of course; there’s no need for a Reign of Terror as there was in France. We are not that sort of a people, here in England. We are rational, and can see the merits of equality without violence.”

“I see the merits in a drink,” said Tom, “here, open another bottle of port, will you, Atkins,” he addressed the second coachman, who had been drinking in Sharp’s words eagerly.

Ellen had been following another line of thought. “What did you say that lady’s name was – how did she take care of her natural children, then? How did she live?”

“Mary Wollstonecraft? Oh, she was a governess or something of the sort, and lived with several gentlemen before marrying Godwin. She was none the worse for all that, and she was very well respected, because of being so clever. There’s nothing shameful in having a lover or two, you know. People of sense don’t think any thing of it, nowadays.”

“But the children,” murmured Ellen, blushing.

“The sins of the father, or mother for that matter, aren’t the fault of the sons,” said Tom airily.

“But see here, bastards are still disgraced in society, you know they are,” protested Yates.

“Not so much, any more. Look at Agatha in our play, isn’t she a heroine despite having a natural son?”

“I would not wish the life of Agatha on any young woman!” protested Rufus the footman, “from what I have seen of the play.”

“Perhaps not; but the real point is, that you have seen the play. It has been shown dozens of times. The subject of love without marriage, and of natural children, is growing everywhere more acceptable. And at any rate, one does not have to have children. There are ways to prevent….”

He looked down at Ellen, and she moved closer to him. “Are there, Mr. Sharp?”

Samuel was thinking hard. “I vow, I will start saving my pay at once, and hope to go to London one day, and go on the stage,” he declared, with a glance at Tom. But Tom was playing with Sarah’s hair, and not listening.

“All this talk is making me tired. Another drink, Sharp?” asked Yates, and passed the port.

Fanny lay awake long that night, trying not to heed the sounds coming from next door. They were such as she had never heard before, and filled her with the utmost horror and shame. She tried to decide what she must do in the morning; there was only Edmund to consult, but she knew she could not speak to him on such a subject, for the world. It might, however, be possible to make some slight hint, and for many hours Fanny feverishly turned over, in her agitated mind, what she must say. Dawn found her still awake, though the sounds through the wall had diminished to heavy snores. Trembling with agitation and sleeplessness, she dressed herself, and went down stairs.

Fanny might bravely resolve to speak to Edmund, come what might, but opportunity was lacking. There was to be a rehearsal of the first three acts entire. To her misery about the shameful revelry she had heard in the night, was added her pain at being forced to see Edmund and Mary Crawford acting together for the first time, and rehearsing a scene of love. At mid-morning she was able to get away from her aunts, and she sought her refuge in the East Room. Unluckily, peace was not to be hers. First Miss Crawford, and then Edmund himself, came to her sanctum for purposes of rehearsing, an exercise that was nothing but torment to Fanny; and then after dinner there was the much-dreaded rehearsal.

Her cousins had been importuning her to read the part of Cottager’s wife, in the absence of Mrs. Grant, and Fanny was, with the greatest reluctance, ceasing to demur, almost more from sheer exhaustion than any thing else; when Julia entered the theatre all in affright, and announced that her father had come.

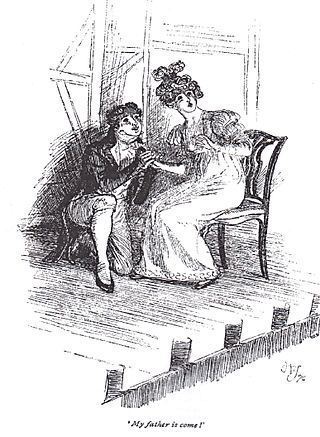

“My father is come!” Illustration by Hugh Thomson.

It could not have been at a worse moment. Henry Crawford was holding Maria’s hand, and Sharp, who had got oiled paints on the floor, was unsuccessfully trying to wipe up the mess with sponges provided by Atkins the under coachman, who was badly hung over.

Mrs. Norris, with great presence of mind, whisked Mr. Rushworth’s pink satin cloak away.

“Damn it all. We must get rid of these filthy sponges,” exclaimed Sharp.

“But what will we do about the floor, sir? That parquet is ruined.”

“Ellen, throw me that piece of green baize, will you? We can toss it over the spill.”

“It belongs to Mrs. Norris, sir, I don’t think she would like – .”

“Bother the old lady. Look here, Ellen, I suspect this job is up. Did you really mean that about wanting to come to London?”

“I did, that is, if you – .” She stopped.

“Of course, of course. So, if you ever get there, just make your way to Covent Garden and anybody can tell you my direction, will you do that?”

“Oh, yes, sir,” she breathed.

The young coachman carried off the sponges, and the company scattered, some to welcome Sir Thomas, others to leave the family to itself at this important moment. Only Yates continued rehearsing, oblivious to any impending unpleasantness.

Who can be in doubt as to what followed? When he heard the whole story of the theatre, Sir Thomas’s anger and disapprobation were very great. He said enough to make his displeasure felt, and then went about, destroying every trace of the theatre, and restoring his house to what it used to be, and ought to be.

Active and methodical, he had not only done all this before he resumed his seat as master of the house at dinner, he had also set the carpenter to work in pulling down what had been so lately put up in the billiard room, and given the scene painter his dismissal, long enough to justify the pleasing belief of his being then at least as far off as Northampton. The scene-painter was gone, having spoilt only the floor of one room, ruined all the coachman’s sponges, and made five of the under-servants idle and dissatisfied.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Natasha Duquette, Margaret Horwitz, Sarah Woodberry, and Joyce Tarpley.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.