Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 28

September 8, 2015

Reading, Writing, Running

Today is my birthday, and I’m planning to celebrate by reading the last chapter of Jane Austen’s Emma early this morning (part of the preparations for my upcoming blog series celebrating 200 years of Emma), by running for about half an hour (part of my training for the half marathon I’m registered for on Saturday), and by writing for the rest of the day before celebrating with my family this evening. I haven’t decided yet what I’ll write about – probably I’ll wait until I’m running to make that decision. I make a lot of decisions when I’m running, and quite often they’re about which writing or editing projects I want to pursue, either that day or in the future, or about what to read next, or about details I’ve been puzzling over in a particular piece I’m working on. For example, I was inspired to start writing the first draft of this blog post while I was running indoors on a track on a rainy day. Do any of you come up with new ideas for reading and writing while you’re exercising? I’d be interested to hear about your experiences.

I didn’t discover running until I was in grad school, and sometimes I envy my sister, who discovered it when she was nine – and hasn’t looked back since. But I feel grateful that I discovered writing when I was very young, starting a diary when I was eight and deciding soon afterwards that I wanted to be a writer when I grew up, and that my parents helped me discover reading long before that.

My first two diaries

(It was fun to go back to my first two diaries and see what I was reading when I was eight: The Trumpet of the Swan, Superfudge, Deenie, The Secret Garden, Ballet Shoes, Anne of Green Gables, The Cuckoo Clock. One morning I woke up at four o’clock and couldn’t get back to sleep, so I read an abridged version of George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda, which I didn’t understand at all. I loved the book when I reread it – unabridged, of course – twenty years later.)

I’ve been thinking for several years about how important reading, writing, and running are to me, and two things I’ve read recently have helped me see the connections among them more clearly. The first is my friend Renée Hartleib’s meditation on the joy of running. In a blog post called “It is solved by running,” she notes that her “energy is at its highest” and her “mind is at its clearest” when she’s active, and she talks about running as a “revelation” and a “reawakening.” I love the way she describes her recurring dream about running so quickly and confidently that it’s almost as if she’s flying. I know exactly what she means about how running brings with it more energy and a clearer mind, both of which make it easier and more fun to write – and to live.

The second is Haruki Murakami’s book What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, in which he says, “Most of what I know about writing I’ve learned through running every day.” He asks:

The second is Haruki Murakami’s book What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, in which he says, “Most of what I know about writing I’ve learned through running every day.” He asks:

How much can I push myself? How much rest is appropriate – and how much is too much? How far can I take something and still keep it decent and consistent? When does it become narrow-minded and inflexible? How much should I be aware of the world outside, and how much should I focus on my inner world? To what extent should I be confident in my abilities, and when should I start doubting myself? (Chapter 4)

I’ve learned a great deal about running and writing from asking myself similar questions, always in search of the appropriate balance between effort and rest. I’ve also learned from Aristotle, whose writing about ethics teaches me the value of the process of becoming virtuous, of becoming better in some way, which can apply to physical strength as well as to moral character. And I’ve learned from Jane Austen (you knew that was coming, right?), whose novels illuminate for me this Aristotelian approach to virtue and vice. Years of writing about Austen and Aristotle have taught me the value of working towards strength – moral, intellectual, physical – while acknowledging that there will never be a point at which I can say, “I’ve got it exactly right this time, and I don’t need to do any more.” I will always need to keep moving, to keep running, to keep thinking, to keep writing and revising, and to do all of that, I need to read – widely, often, and with enthusiasm and curiosity.

I like what Matthew Arnold says in the preface to Culture and Anarchy (1869) about the importance of reading: “a man’s life of each day depends for its solidity and value on whether he reads during that day, and, far more still, on what he reads during it.”

like what Matthew Arnold says in the preface to Culture and Anarchy (1869) about the importance of reading: “a man’s life of each day depends for its solidity and value on whether he reads during that day, and, far more still, on what he reads during it.”

And I like what Mr. Darcy says in Pride and Prejudice about how he “cannot comprehend the neglect of a family library in such days as these” (Chapter 8). (Poor Miss Bingley, whose father has “left so small a collection of books.” My bookseller friends will attest to my efforts to follow Mr. Darcy’s advice and pay close attention to my family library. Quite often my days consist of reading, writing, running, and book-buying. Or library-going.)

The half marathon I plan to run on Saturday will be my third. The first one was in 2013 and the second was last year, all at this same race in Halifax, Maritime Race Weekend. I’m starting to think of it as my new birthday tradition, along with a tradition of making a donation to an institution or charity that supports literacy – because September 8th is International Literacy Day. (Now that’s the kind of “birthday coincidence” I really like! Although if you have birthdays in August or October, dear readers, I will, like Anne of Green Gables, happily celebrate that “coincidence” too.)

Maritime Race Weekend is held at Fisherman’s Cove. The ocean views on the half marathon route are stunning, and last year I was very tempted to take pictures along the way – something I love to do on training runs – but I resisted and took this picture after I had finished the race.

This year, I almost gave up on half marathon #3, because while I liked the idea of my new tradition very much, in the spring my hip was bothering me and I wasn’t running as much as I did last year or the year before when I prepared for longer distances. I considered deferring my registration to 2016, and wondered, with Murakami, “How much rest is appropriate – and how much is too much?” I didn’t want to push myself to the point at which I might get a serious injury, but I didn’t want to back out if I didn’t really need to. (As Henry Tilney says in Northanger Abbey, “When properly to relax is the trial of judgement” [Chapter 16].) At the beginning of July, with a new training plan from my sister and encouragement from family and friends, many of whom are experienced runners, I decided to train for this half marathon.

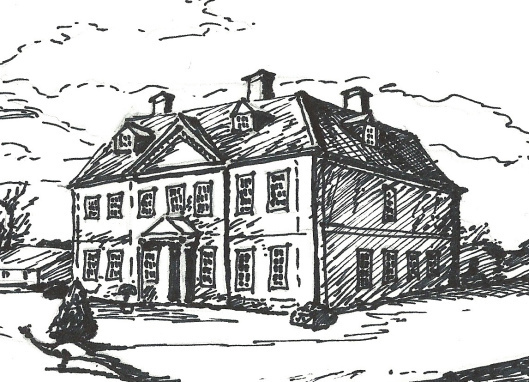

I’m glad I let go of the feeling that I ought to be able to run faster than I did last year or the year before. On training runs I paid more attention to what I was seeing and to how I was feeling than to how fast I was going. There are so many beautiful trails in Nova Scotia, and I enjoyed exploring some of them this summer, including the Old Post Road at Uniacke House.

Uniacke House

When it came time for the longest training run of the summer, I happened to be in southern Alberta, and I loved running for a couple of hours on a cool August morning down a prairie road that I’ve known since childhood.

I did have to add some extra hill training when I got back to Nova Scotia.

I’m now feeling very excited about celebrating my birthday by running for 13.1 miles. Someday, I might like to run a marathon, but even if I do reach that goal, I’ll know that I’ve celebrated the process all along the way.

And someday perhaps I’ll write more about running and setting goals in relation to my new favourite topic, ambition. My interest in L.M. Montgomery’s phrase “the bend in the road” is also linked to my passion for running. I have lots of ideas for future books and essays and blog posts, but even while I’m aiming for specific writing goals, I’m committed to enjoying the energy and clarity that I get from reading, writing, and running pretty much every day.

And on days when I don’t really feel like writing or running, when I don’t have that “almost-flying” feeling Renée describes – and there are plenty of them, as I expect there are for most writers and runners – I’m going to keep reminding myself of what Jane Austen says about being a reluctant writer: “I am not at all in a humour for writing; I must write on till I am” (from a letter to her sister Cassandra, October 26, 1813). If I am not in a humour for running, I must keep running until I am. I might even run mad as often as I choose, but I’ll take care not to faint.

August 28, 2015

Anne Shirley’s Ambitions

I’ve always loved the image of the “bend in the road” that appears in the final chapter of L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables. Anne’s plans for the future change, and while she can’t quite see what’s ahead of her on that road, she’s ready to move forward with confidence to embrace the unknown. I thought about this passage last summer when I found Montgomery had pasted into her Red Scrapbook a Notman Studio photograph of a bend in the road at Point Pleasant Park.

Warburton Road

Imagine my delight when I looked up the passage from that last chapter of Anne of Green Gables once again and discovered that in addition to talking about making peace with the mysteries of the future, Anne talks about her ambitions. She tells Marilla she’s decided to stay at home with her so they won’t have to give up Green Gables:

“Nothing could be worse than giving up Green Gables – nothing could hurt me more. We must keep the dear old place. My mind is quite made up, Marilla. I’m NOT going to Redmond; and I AM going to stay here and teach. Don’t you worry about me a bit.”

“But your ambitions – and – ”

“I’m just as ambitious as ever. Only, I’ve changed the object of my ambitions. I’m going to be a good teacher – and I’m going to save your eyesight. Besides, I mean to study at home here and take a little college course all by myself. Oh, I’ve dozens of plans, Marilla. I’ve been thinking them out for a week. I shall give life here my best, and I believe it will give its best to me in return. When I left Queen’s my future seemed to stretch out before me like a straight road. I thought I could see along it for many a milestone. Now there is a bend in it. I don’t know what lies around the bend, but I’m going to believe that the best does. It has a fascination of its own, that bend, Marilla. I wonder how the road beyond it goes – what there is of green glory and soft, checkered light and shadows – what new landscapes – what new beauties – what curves and hills and valleys further on.”

– From Chapter 38, “The Bend in the Road”

If you’ve been following my blog for a while, you’ll know that I’ve been getting more and more interested in the topic of ambition in relation to Jane Austen’s life and works. I had forgotten that Marilla and Anne use that term when Anne talks about the bend in the road. So now, of course, I’m inspired to explore what Montgomery says about ambition elsewhere in her novels, alongside my research on “Austen and Ambition.” I’d be interested to hear your thoughts on either of these writers – or my other favourite author, Edith Wharton – and the things they say about ambition in their fiction and letters. I’m curious to find out more about this topic and I’ll keep you posted as my “dozens of plans” take shape.

August 14, 2015

“It’s good to be alive and to be going home”

In Anne of Green Gables, after a trip to Charlottetown, Anne and Diana return home to Avonlea along the north shore of Prince Edward Island:

Anne and Diana found the drive home as pleasant as the drive in – pleasanter, indeed, since there was the delightful consciousness of home waiting at the end of it. It was sunset when they passed through White Sands and turned into the shore road. Beyond, the Avonlea hills came out darkly against the saffron sky. Behind them the moon was rising out of the sea that grew all radiant and transfigured in her light. Every little cove along the curving road was a marvel of dancing ripples. The waves broke with a soft swish on the rocks below them, and the tang of the sea was in the strong, fresh air.

“Oh, but it’s good to be alive and to be going home,” breathed Anne.

– From Chapter 29, “An Epoch in Anne’s Life”

A few weeks ago, when I visited the Island with my family, we drove from Charlottetown back to our friends’ cottage one evening after dinner, stopping at the beaches at Dalvay and Stanhope to admire and photograph the spectacular sunset. It was good to be alive.

Dalvay Beach

Stanhope Beach, a few minutes later.

July 29, 2015

Five Years!

Jane Austen’s letters, her novels Emma and Persuasion, the virtue of charity, the history of Nova Scotia, and the composition of Edith Wharton’s novel The Custom of the Country: these topics and other favourites appear right from the beginning, in the first few posts I wrote when I launched this blog in the summer of 2010. It’s hard to believe five years have gone by since then (and, given my later obsession with Mansfield Park, it’s hard to believe there was no mention of it at all in those early posts).

Thank you for reading the blog and for writing comments and guest posts. It’s been a real pleasure to create a place for “good company and a great deal of conversation” and I’m looking forward to future conversations with all of you!

To celebrate the five-year anniversary of my blog, I’ve put together a list of the first five posts, plus the five most popular posts and five of my own favourites. If you’d like to read each post in its entirety, click on the title.

The first five:

The first five:

“‘I do not mean to take any other exercise, for I feel a little tired after my long Jumble.’ Jane Austen was writing to her sister Cassandra after the journey to her brother Henry’s house in London. I love the idea of a long, tiring road trip as a ‘jumble’….”

French Fact and American Fiction

French Fact and American Fiction

“Edith Wharton was in the process of moving to France during the years she worked on The Custom of the Country, which makes me wonder if her increasing affection for France and her attempts to distance herself from her American life prompted her to fictionalize – and satirize – American places while implying that there was something more ‘real’ about France….”

“The other day, on a sunny summer afternoon when I was picking blueberries in the Annapolis Valley, I happened to overhear a conversation about Emma and Mr. Knightley. A couple of rows over (these were high bush blueberries), one woman was telling another about the scene on Box Hill, describing how Emma insults Miss Bates and how Mr. Knightley tells her that what she has said was ‘badly done.’ For a moment I felt like Anne Elliot in Persuasion, overhearing a conversation that interests her from behind the hedgerow….”

“The other day, on a sunny summer afternoon when I was picking blueberries in the Annapolis Valley, I happened to overhear a conversation about Emma and Mr. Knightley. A couple of rows over (these were high bush blueberries), one woman was telling another about the scene on Box Hill, describing how Emma insults Miss Bates and how Mr. Knightley tells her that what she has said was ‘badly done.’ For a moment I felt like Anne Elliot in Persuasion, overhearing a conversation that interests her from behind the hedgerow….”

Mr. Lushington and the Franfraddops

“I think one of the reasons Austen is so good in her novels at dramatizing the problem of how to speak and act in a charitable manner is that she knows all too well the very human temptation to speak ill of others….”

“The town of Annapolis Royal is celebrating its 300th anniversary this year, and when I was there I was thinking about how different the history of Nova Scotia would be if Annapolis Royal had remained the capital of the province, as it was from 1710 to 1749, before Halifax was founded….”

The five most popular:

Jane Austen’s “Darling Child” Meets the World

Jane Austen’s “Darling Child” Meets the World

“Jane writes to her sister Cassandra that she’s grateful for Cassandra’s praise of the novel because she has been having ‘some fits of disgust’ recently. She is at home in Chawton without Cassandra, keeping the secret of her authorship from her neighbours and enduring the irritation of listening to her mother’s interpretation of her characters….”

Your Invitation to Mansfield Park

“The party begins on Friday, May 9th, with Lyn Bennett’s thoughts on the first paragraph, followed in the next few weeks by Judith Thompson on Mrs. Norris and adoption, Jennie Duke on Fanny Price at age ten (‘though there might not be much in her first appearance to captivate, there was, at least, nothing to disgust her relations’), Cheryl Kinney on Tom Bertram’s assessment of Dr. Grant’s health (‘he was a short–necked, apoplectic sort of fellow, and, plied well with good things, would soon pop off’), and Katie Davis on Mrs. Grant’s promise to Mary and Henry Crawford that ‘Mansfield shall cure you both’….”

“The party begins on Friday, May 9th, with Lyn Bennett’s thoughts on the first paragraph, followed in the next few weeks by Judith Thompson on Mrs. Norris and adoption, Jennie Duke on Fanny Price at age ten (‘though there might not be much in her first appearance to captivate, there was, at least, nothing to disgust her relations’), Cheryl Kinney on Tom Bertram’s assessment of Dr. Grant’s health (‘he was a short–necked, apoplectic sort of fellow, and, plied well with good things, would soon pop off’), and Katie Davis on Mrs. Grant’s promise to Mary and Henry Crawford that ‘Mansfield shall cure you both’….”

Why is Mr. Darcy So Attractive? (and of course the reasons for the popularity of this post are totally mysterious to me)

Why is Mr. Darcy So Attractive? (and of course the reasons for the popularity of this post are totally mysterious to me)

“We now live in a world that relies heavily on visual images, which is part of why ‘Colin Firth in a wet shirt’ signifies passion and desire in Pride and Prejudice. Yet in the novel, Austen makes clear that this moment is significant not because Elizabeth is looking at Darcy and admiring his handsome face or figure, but because there is such a strong connection between the two of them already that ‘their eyes instantly met,’ and they simultaneously blush at meeting in such circumstances. They’re looking at each other. It isn’t that the heroine and readers or audience are gazing at Darcy….”

Attending Redmond College with Anne Shirley

Attending Redmond College with Anne Shirley

“Redmond College is based on Dalhousie University and the ‘quaint old town’ of Kingsport described in Anne of the Island is based on Halifax….”

Clarity and Complexity: Mansfield Park Begins

“Happy 200th anniversary to Mansfield Park, published on this day in 1814. Mansfield Park is not as famous as Jane Austen’s ‘darling child’ Pride and Prejudice, but it’s still beloved, and the celebrations are just beginning. … I’m very happy to introduce Lyn Bennett’s guest post on the opening paragraph of Mansfield Park….”

Five of my own favourites:

“Jane Austen thought of her books as her children. Pride and Prejudice, which she called ‘my own darling Child,’ was sold to Thomas Egerton in November 1812. Two hundred years ago today, Jane wrote to her friend Martha Lloyd that ‘P. & P. is sold.—Egerton gives £110 for it.—I would rather have had £150, but we could not both be pleased, & I am not at all surprised that he should not chuse to hazard, so much’….”

Mansfield Park is a Tragedy, Not a Comedy

“Many readers find the ending of Mansfield Park disappointing. I think that’s because most of us tend to approach Austen novels with the expectation that they will be romantic comedies. And most of them are. But not this one….”

“Many readers find the ending of Mansfield Park disappointing. I think that’s because most of us tend to approach Austen novels with the expectation that they will be romantic comedies. And most of them are. But not this one….”

What Edith Wharton Tells Us About the Way We Live Now

“Wharton’s criticism of materialism, cultural ignorance, and the dangers of extreme versions of Emersonian self-reliance is more relevant than ever….”

L.M. Montgomery’s Literary Pilgrimage to Concord, Mass.

L.M. Montgomery’s Literary Pilgrimage to Concord, Mass.

“Given how many fans of L.M. Montgomery visit ‘Green Gables’ in Cavendish, PEI each year, I find it fascinating to read about Montgomery’s own literary pilgrimage to Concord, Massachusetts, when she was visiting her publisher, L.C. Page in Boston in November of 1910. ‘Concord is the only place I saw when I was away where I would like to live,’ she writes….”

“‘Happy for all her maternal feelings was the day on which Mrs. Bennet got rid of her two most deserving daughters.’ The opening line of the last chapter of Pride and Prejudice is my favourite line in the novel because it’s the only mention of the wedding day for Elizabeth and Darcy, and Jane and Bingley. I like it because the focus on Mrs. Bennet’s attitude toward weddings ties the ending of the novel to the beginning, because the sentence is short and snappy, and because this line challenges the expectations of readers who come to the novel expecting a big wedding as the culmination of the courtship plot. There’s no question that Pride and Prejudice has a happy ending — but the wedding day isn’t the most important part of the happy ending….”

Thanks again to all of you for being part of the conversations and celebrations here!

July 18, 2015

“We must think the best”

“We must think the best & hope the best & do the best.” Jane Austen wrote this line in a letter to her sister Cassandra on November 26, 1815, when their brother Henry was very ill, and I’ve returned to it many times over the years that I’ve been studying her life and letters. Henry has been hoping he’ll be able to travel to Oxford for a few days, but although he “gets out in his Garden every day … at present his inclination for doing more seems over” and “his feelings are for continuing where he is, through the next two months.” “One knows the uncertainty of all this,” Jane acknowledges, “but should it be so, we must think the best & hope the best & do the best.”

This is not the “syringa, iv’ry pure” of Cowper’s line, but I thought it was pretty anyway. “I could not do without a Syringa, for the sake of Cowper’s Line” (Jane to Cassandra, February 8 and 9, 1807)

She tells Cassandra that “Henry calls himself stronger every day & Mr. H. keeps on approving his Pulse – which seems generally better than ever – but still they will not let him be well. – The fever is not yet quite removed. – The Medicine he takes (the same as before you went) is cheifly to improve his Stomach, & only a little aperient. He is so well, that I cannot think why he is not perfectly well.”

She was determined to be optimistic in the face of death, just as she was eighteen months later after Henry had recovered and she herself was ill. She wrote to her friend Anne Sharp on May 22, 1817 that while “inspite of my hopes & promises when I wrote to you I have since been very ill indeed,” “Now, I am getting well again, & indeed have been gradually tho’ slowly recovering my strength for the last three weeks. I can sit up in my bed & employ myself, … & really am equal to being out of bed, but that the posture is thought good for me.” She was so well, it seems, that she could not think why she was not perfectly well.

Later in that same letter to Miss Sharp there’s another example of her “thinking the best.” She’s grateful for the kindness of those who are caring for her, and she concludes, “In short, if I live to be an old Woman I must expect to wish I had died now, blessed in the tenderness of such a family, & before I had survived either them or their affection.”

Jane Austen died 198 years ago today, on July 18, 1817.

I mentioned a few weeks ago that I was entertained by the only line in her letters in which she explicitly mentions her ambition: “I wore my Aunt’s gown & handkercheif, & my hair was at least tidy, which was all my ambition” (from a letter she wrote to Cassandra on November 20 and 21, 1800). I like the idea of putting this ironic line together with her more serious ambition to “think the best & hope the best & do the best.” What should we aim for, in ordinary life or under extraordinary duress? “The best.”

Quotations are from the fourth edition of Jane Austen’s Letters, edited by Deirdre Le Faye (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

July 3, 2015

Imagining Jane Austen’s Childhood

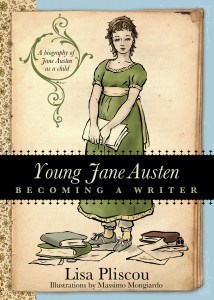

“But history, real solemn history, I cannot be interested in … a great deal of it must be invention,” says Catherine Morland in Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey. In Young Jane Austen: Becoming a Writer, Lisa Pliscou cites Catherine’s words as inspiration for her “speculative biography” of the period from Austen’s birth to the age of twelve, when she began to focus on writing stories. Lisa knows about my interest in introducing Jane Austen to children, so she sent me a copy of her new book, and I’m glad she did because I had heard about it and I was curious to read her version of Austen’s early years. Noting that few facts are known about this period and acknowledging that she risks satisfying “neither the most stringent biographer nor the reader anticipating a great deal of dialogue and description,” Lisa offers an imaginative recreation of Jane Austen’s childhood.

A series of brief meditations on such topics as “Home,” “Play,” “Evening,” “Leaving Home,” “School,” and “Cousin Eliza” illuminate crucial moments in Austen’s childhood – such as the transitions from the Austen family home to her foster home in the village of Steventon and, later, to Mrs. Cawley’s school in Oxford and the Abbey School in Reading – and highlight important aspects of daily life in the Austen family, including helping with chores, listening to others read books and newspapers aloud, attending church services, and playing outdoors.

The thread that connects all the pieces of the story is a question Jane Austen must have returned to again and again: what opportunities are open to girls? This was an excellent question in the late eighteenth century and it’s an excellent question now. Lisa draws attention to possible answers throughout her book. In the section on “Play” she writes, “You could go to the big barn and pretend you were a king or a monster or a sailor or a tossing ship, and be as loud as you liked – even if you were a girl.” She imagines young Jane watching as her brothers’ lives took shape – James studying, Edward travelling, George being sent away because he had fits and could not speak or hear – and coming to the realization that “Home was not a place where you stayed forever.”

Jane’s older brother James was known as “the writer in the family,” after Mrs. Austen’s assessment of his talents, and Lisa explores what Jane might have thought about that label. It’s easy to imagine her wondering whether there could be more than one writer in a family, especially given that Mrs. Austen wrote letters and verses and Mr. Austen wrote letters and sermons. Young Jane – Lisa calls her Jenny, the nickname her father gave her when she was born – is a reader, and she interprets the world around her as if it is a story. When her sophisticated cousin Eliza comes to visit, Lisa says, “To Jenny it seemed as if Eliza had stepped straight from the pages of a book.” Jane is fascinated by books about people, especially “awful old Queen Elizabeth,” “poor Mary Stuart,” and heroines whose “saintly goodness” is amusing, and she is curious about books that tell young ladies how they ought to behave. “What could a girl do?”

Lisa suggests that the questions Jane Austen asked as a young child led her to the realization that she could do something exciting with words and stories. At the end of Young Jane Austen, “Jenny – Jane – picked up her pen, and began to write.”

This moment is only the beginning of Jane Austen’s development as a writer, of course, and in fact it isn’t the end of this biography either. The book doesn’t take up the question of what Austen wrote as a child; instead, the second half of the book repeats the story from birth to age twelve, this time with annotations instead of illustrations. The first half of the book will be especially appealing to young readers, with Massimo Mongiardo’s delightful sketches of Jane, her family, and her home. The second half of the book will be of interest to older readers who want to know about the sources Lisa has drawn on in imagining Jane’s early years.

At first I was somewhat surprised at the way the book is organized – the second part repeats the text of the first part, in addition to providing notes. But I think the division and repetition are quite helpful. Younger readers can ignore the second half if they wish, while those who want to read the details in that section won’t find themselves flipping back and forth between text and endnotes.

I think Young Jane Austen is a charming book, of interest to readers of all ages in its imaginative retelling of central events in Austen’s life and its exploration of questions over which she must have puzzled. I have two main criticisms to offer. One is the overuse of italics – I think L.M. Montgomery’s Mr. Carpenter is right when on his deathbed he advises Emily Starr to “Beware – of – italics” in her writing (in Emily’s Quest). The other is that I wish the book continued beyond the point at which Austen began to write. I would have liked to hear more commentary on the development of Austen’s juvenilia.

But that is a separate topic, and one Juliet McMaster addresses in her own new book, Jane Austen, Young Writer, forthcoming later this year from Ashgate. Juliet’s book is based on her years of research on the juvenilia: she founded the Juvenilia Press and has edited many of Jane Austen’s youthful writings, including The Beautifull Cassandra, which is one of my favourites. (She also wrote a guest post for my Mansfield Park celebrations last year.) Young Jane Austen and Jane Austen, Young Writer are very different, but for many readers – admittedly not the younger readers for whom Lisa’s book will be an introduction to Austen’s early life – they will be complementary.

But that is a separate topic, and one Juliet McMaster addresses in her own new book, Jane Austen, Young Writer, forthcoming later this year from Ashgate. Juliet’s book is based on her years of research on the juvenilia: she founded the Juvenilia Press and has edited many of Jane Austen’s youthful writings, including The Beautifull Cassandra, which is one of my favourites. (She also wrote a guest post for my Mansfield Park celebrations last year.) Young Jane Austen and Jane Austen, Young Writer are very different, but for many readers – admittedly not the younger readers for whom Lisa’s book will be an introduction to Austen’s early life – they will be complementary.

Read more about introducing children to Jane Austen’s life and works on my page “Jane Austen for Kids.”

June 23, 2015

Birthday “Coincidences” in Emma and Anne of Green Gables

Harriet Smith is delighted by the idea that Robert Martin’s birthday is just two weeks and a day before her own. In Chapter 4 of Jane Austen’s Emma, she tells Emma that “He was four-and-twenty the 8th of last June, and my birth-day is the 23d – just a fortnight and a day’s difference! which is very odd!”

Emma was published on December 25, 1815, and I’m rereading it in honour of the 200th anniversary. Soon I’ll be able to tell you more about the exciting series of guest blog posts I’m planning – kind of like “An Invitation to Mansfield Park,” the series I hosted in 2014, but shorter. The new series will begin in December of this year.

For now, I want tell you about something that occurred to me when I read about the “coincidence” that both Harriet Smith and Robert Martin were born in June.

In Anne of Green Gables, when Anne Shirley meets Diana Barry for the first time, Marilla asks if she found Diana a “kindred spirit,” and Anne launches into a rapturous monologue about her new friend. Among the many delightful things she has discovered is the fact that “Diana’s birthday is in February and mine is in March. Don’t you think that is a very strange coincidence?”

So here’s my question for you – do you think L.M. Montgomery is consciously echoing Austen here? I love the idea that having birthdays in the same month, or in consecutive months, is a meaningful coincidence.

I visited Prince Edward Island again last week and I have some new photos to share with you. What a difference a few weeks can make! (Scroll down to the bottom of this post on “Anne and Gilbert After the Happy Ending” to see photos of snow and grey skies, from my visit at the end of April).

L.M. Montgomery’s birthplace, New London

In the distance you can just see the famous sand dunes of New London Bay.

Dalvay Beach

French River. One of the most photographed places in PEI.

Springbrook

Happy birthday to Harriet Smith today, and happy birthday to anyone else who happens to have a birthday in June (or May, or July, or February, or March).

June 12, 2015

Austen and Ambition

I went to Philadelphia last weekend to speak on Jane Austen and ambition at a JASNA Eastern Pennsylvania meeting, and my favourite part of the trip was the lively discussion after my talk about whether Austen saw ambition as a vice or a virtue. It was wonderful to discuss this controversial question with so many smart people who know Austen’s novels and letters so well.

The conversation inspired me to consider what I want to do next with this topic. Blog posts? A new essay on ambition, focusing on a specific novel? (Or perhaps, someday, a book on Austen and ambition?) I’ll have to spend some more time thinking about these questions. For now, if you’d like to know more about my talk, you might be interested in reading what Deborah Yaffe (author of Among the Janeites) wrote on her blog about the event: “Austen, ambition and Emsley.” It was such fun to see Deborah and other JASNA friends both old and new, and to explore this exciting topic with them.

Here are two of of my favourite passages about ambition in Austen’s novels:

Mrs. Dashwood and Edward Ferrars discuss ambition in Sense and Sensibility, Chapter 17:

“You have no ambition, I well know. Your wishes are all moderate.”

“As moderate as those of the rest of the world, I believe. I wish as well as every body else to be perfectly happy; but like every body else it must be in my own way. Greatness will not make me so.”

I love how Mrs. Dashwood tells, rather than asks, Edward about his ambition. She’s trying to reassure him it’s all right that he lacks professional ambition. But in fact he has very high ambitions of a different kind.

Lady Catherine to Elizabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice, Chapter 56:

“Do not imagine, Miss Bennet, that your ambition will ever be gratified.”

If Elizabeth had been ambitious about “marrying up,” she could have accepted Darcy’s first proposal.

And then in Austen’s letters, the best line about ambition is “I wore my Aunt’s gown & handkercheif, & my hair was at least tidy, which was all my ambition” (20 November 1800).

On my run on Sunday morning I stopped at Independence Hall to take a picture and to read about the Liberty Bell.

I had a fabulous weekend in Philadelphia and I’m grateful to Paul Savidge, Regional Coordinator, and members of the Board and Region for inviting me to visit. It was a weekend of good books and good conversations, and that made me very happy. (Good food, too….)

It was great to visit the Rodin Museum on Sunday.

May 15, 2015

Reading Austen’s Emma with Sherlock Holmes, Dr. Watson, and Deborah Knuth Klenck

I’m excited to share the news that Deborah Knuth Klenck is coming to Halifax later this month and she’ll speak on “Learning to Read with Emma” at a JASNA Nova Scotia event on Sunday, May 31st at 2pm. Please email me (semsley at gmail dot com) or leave a comment here if you’re interested in attending and I can send you more details.

The following weekend, I’ll be in Philadelphia to give a talk on “Austen and Ambition,” and I can’t wait to meet up with friends both old and new from JASNA’s Eastern Pennsylvania Region. The luncheon and talk will be held at the Sheraton Society Hill Hotel on Saturday, June 6th at 11:30am. Details and registration information are available here.

I’m having such fun writing about ambition in Austen’s life and works—and the fascinating question of whether ambition is a virtue or a vice—and it would be very easy for me to write several blog posts about this topic. But I’ll save that for another time, because right now I want to tell you about Deborah’s talk on Emma.

The talk she’s going to give in Halifax is a version of one she’ll give in June at the Jane Austen Summer Program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She tells me “it’s about how much more we understand the novel as we re-re-read it. It’s the debut of my theory of reading based on the detective stories of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle: first readers are clueless Watsons who think they’re Holmeses—Emma thinks she’s Holmes and takes a LONG time to see that she’s been Watson all along. Both authors mislead the reader the first time through, and the talk goes through some examples.” Deborah says, “I’ve probably read the novel thirty times or so, but I’m still ‘getting’ stuff I should have seen earlier.”

The talk she’s going to give in Halifax is a version of one she’ll give in June at the Jane Austen Summer Program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She tells me “it’s about how much more we understand the novel as we re-re-read it. It’s the debut of my theory of reading based on the detective stories of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle: first readers are clueless Watsons who think they’re Holmeses—Emma thinks she’s Holmes and takes a LONG time to see that she’s been Watson all along. Both authors mislead the reader the first time through, and the talk goes through some examples.” Deborah says, “I’ve probably read the novel thirty times or so, but I’m still ‘getting’ stuff I should have seen earlier.”

Deborah was trained at Smith College and Yale University and is Professor of English at Colgate University, where she teaches classes on Shakespeare and Milton as well as on eighteenth-century writers and, of course, Jane Austen. She says her love of Austen was “of such long-standing unabashedness that, at first, it hardly seemed to be a sufficiently ‘academic’ field for research. Fortunately, between Colgate students clamoring for a Jane Austen course and the enthusiasm of J. David ‘Jack’ Grey, a co-founder of the Jane Austen Society of North America,” she says, she was encouraged to begin writing and teaching about Austen’s work.

Her first JASNA AGM talk was on female friendship in the Juvenilia, in Manhattan in 1987. She has since spoken at AGMs in Santa Fe, Lake Louise, Milwaukee, Philadelphia, and, she adds, “almost Minneapolis, where my son, an Austenite Ph.D. candidate in his own right, delivered my talk in my stead, after I broke my leg.” She has also been a guest speaker at many regional JASNA meetings. Deborah tells me she is delighted to have a chance to meet some of the members of JASNA Nova Scotia. I know we are equally delighted to have the opportunity to hear her speak.

Today, in anticipation of Deborah’s talk, I’m pleased to share with you a short piece she wrote introducing her idea about reading and rereading Emma with Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson.

I have taught British literature at Colgate University since 1978. I began with courses in the field of my graduate work: Restoration and eighteenth-century literature, predominantly satire. Over time, partly owing to student demand, I have taught more and more courses on fiction—and the shift in my teaching led to my writing on Jane Austen—now a much more important subject of my scholarship than the works of Pope, Swift, or Congreve. My Jane Austen seminar became a frequent offering. Nevertheless, I am always acutely aware that a fiction course presents a special challenge to undergraduate readers and hence to their professor: the problem? In contrast with a course where drama or poetry prevails, a fiction course is rather unforgiving: if one falls behind on the reading, how can one ever catch up with what rapidly becomes a runaway train?

It’s true that a senior seminar on Jane Austen requires a lot of reading, but many students who elect such a course are already familiar with (and love) at least some texts on the syllabus. The first time I taught English 388, Colgate’s “Survey of the British Novel,” on the other hand, I couldn’t count on well-prepared “fans” of the books. I tried to envision how I would “get” the class “through” the texts (one of which was Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa).

I explained my dilemma in a kind of cry for help on the first day of class. I passed out a famous 1912 photograph of Robert Falcon Scott and his four compatriots at the South Pole. I told the class the story of Scott’s doomed expedition, and pointed to the harnesses the men wear in the picture: they were hauling their own sledges, I explained. In contrast, Roald Amundsen, who beat the British to the Pole and brought his men back alive, used sled dogs on the journey. (The dogs were, of course, used in more ways than one: some became, as planned, a food source for men and dogs along the way and on the way back, but this was not the aspect of the contrast I wanted to emphasize.)

“Why did I show you this picture?” I asked the class. “Because when I was offered the opportunity to teach this course, I immediately conceived that getting through these novels in a single term would require that I pull you bodily through the texts.”

“I have a bad back,” I continued, “and therefore, in this course, you have to be the dogs.” (The point was about speed and economy of effort—not about any plans to experiment with recipes for cannibal stew. Luckily, the class seemed to appreciate the analogy in the way I meant it.)

By and large, such pep talks have worked, over the years.

But on the eve of the two-hundredth birthday of Charles Dickens, I undertook to revive a senior seminar on his work. The course had been taught by my late colleague, the novelist Frederick Busch, but had languished in the Catalogue since his death. My bold plan was in honor of Fred as much as Dickens, but it filled me with dread—how does one arrange a course in which there will be almost 4,000 pages of reading?

Having wrung all the significance I could out of the dog-sledding metaphor, I came up with another, almost contemporaneous British touchstone for reading: the “Sherlock Holmes method.”

The Arthur Conan Doyle short stories and novels are told to us by Dr. Watson, a rather clueless if amiable chap. But at the end of every adventure, Holmes reviews everything that has contributed to the solution of the mystery—clues and plot elements that he has understood from the start—finally letting Watson and the reader know what’s actually been going on. In the late spring before the fall seminar, I sent all the students pre-registered for the course (there were 17 of them) the full syllabus, including the titles and specific editions we were to use. I enjoined them to “pre-read” all of the novels—so that we could be re-reading them together throughout the fall. “On our first readings of a novel,” I explained—or perhaps warned, “we think we understand things—we like to fancy ourselves Holmes. But it often turns out that we’re more like Watson.” I hoped that our second readings during the fall term would be much more useful if everyone got the Watson work out of the way over the summer.

It worked! During the fall term, everyone found their way around the texts with the ease that comes with familiarity. Our class discussions were especially satisfying because everyone entered into them, at every class.

What happens when we apply Sherlock Holmes’s methods to another two-hundredth-birthday subject: Emma? What do we learn when we re-read Emma? And how long does it take Emma herself before she realizes that she’s been “reading” her own surroundings and neighbors as if she is a clueless Watson, not, as she assumes, a clever Holmes?

That’s the subject of my talk, originally titled “‘Elementary, my Dear Harriet?’: Misreadings and Missed Readings in Emma” and now titled, more simply, “Learning to Read with Emma.”

May 9, 2015

Rose Reads Mansfield Park

My fourteen-year-old friend Rose is reading Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park for the first time. Last fall she reviewed the Real Reads version of the novel adapted by Gill Tavner, and after she read your comments encouraging her to read the original—thank you, dear readers!—she decided to try it. In honour of the 201st anniversary of Mansfield Park, which was published on May 9, 1814, here is the first instalment of Rose’s commentary.

After reading the abridged version I was expecting most of the things I saw. One thing that did surprise me was Fanny. She is really relatable, which I didn’t find in the shorter version. She is sweet—probably funny when she knows you well and quiet when she doesn’t. As far as I know this might be one of Jane Austen’s more normal characters. Not everyone can be as sassy as Lizzy Bennet and I think I like that the books show that.

It’s way more apparent here how the adults think they are doing Fanny a favor and how wrong they really are. It also highlights how bad they are at communicating their feelings. Fanny is too scared to share how she feels about being away from home and the truly sad bit about this is that she has every right to be. Nobody is going to care if she complains. In fact they’ve said they will send her away or punish her if she isn’t happy. It’s so awful for them to force these expectations on her! In the abridged version of the book the author made her seem like a wimp. She just couldn’t manage a new environment or even adapt. That’s so wrong! She’s being bullied, shamed, and criticized, all while being as polite and cheerful as she can.

I find this book to be very similar to a lot of modern books about the new girl in school. Someone used to be the best student, tragedy strikes, she moves to a better school, her grades drop, she’s bullied…. She falls for the popular boy, the rival mean girl appears, the main character is good and sweet, she wins, she lives happily ever after…. Reading this book makes you realize how influential Jane Austen was.

The Fanny and Edmund thing can be a bit weird to read about, especially knowing the end. If a modern author were writing this it would turn out that there was some kind of scandal and they weren’t actually cousins. I would feel very safe supporting (read: adoring) that relationship if they weren’t blood relatives. But it seems as if Jane wants me to like the cousins thing. The fact that they are cousins is mentioned every other page and Sir Thomas seems worried that later in life they will like each other. I don’t know if… I’m just not sure how I feel about it yet.

I was astonished at how some characters that seemed in the right in the shorter version of the book were really stuck up, rich idiots in the larger one. The girls, the adults—everyone is holding Fanny’s social standing against her. Overall I ended up liking Fanny way more than I expected. My favorite parts were all mentions of the pug. I am hoping to see him (or is it her?) develop into his true role as the leading character.

If you missed some (or all) of the guest posts from the series I hosted last year in honour of the 200th anniversary, you can read them here: An Invitation to Mansfield Park.