Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 24

July 18, 2016

“What are men to rocks and mountains?”

“What are men to rocks and mountains? Oh! what hours of transport we shall spend! And when we do return, it shall not be like other travellers, without being able to give one accurate idea of any thing. We will know where we have gone—we will recollect what we have seen. Lakes, mountains, and rivers shall not be jumbled together in our imaginations….”

—from Pride and Prejudice, Volume 2, Chapter 4

Cascade Ponds

Cascade Mountain

Last week I spent a couple of hours in Banff, Alberta, and naturally I thought of what Elizabeth Bennet says about mountains in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice when she accepts an invitation to travel with her uncle and aunt, Mr. and Mrs. Gardiner, possibly as far as the Lakes.

Bow Falls

Crossing the Bow River on the Banff Pedestrian Bridge

Today is the 199th anniversary of Jane Austen’s death. She died in Winchester, at the age of 41, on July 18, 1817.

Looking at Mount Rundle from the Bow Falls Trail

June 17, 2016

Of French Cooks and Hobs – A Pride and Prejudice Menu

I’m pleased to introduce a guest post from Erna Buffie on food in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. Erna’s first novel, Let Us Be True—“A story as starkly beautiful as a prairie landscape” (The Globe and Mail)—was published last fall by Coteau Books and it was shortlisted for the Margaret Laurence Award for Fiction and the Eileen McTavish Sykes Award for Best First Novel at the 2016 Manitoba Book Awards. My book club read the novel and I found it fascinating to learn about the central character, Pearl, from the perspective of several different members of her family. Her daughter Darlene, for example, thinks of her as “an irritant that had rolled itself into something hard and round and opaque but not smooth. More like a freshwater pearl: irregular and covered in ridges.” One of my favourite scenes in the book shows Pearl’s daughter Carol finding the diary she kept as a teenager and reading the note her mother has left in it for her. Of course I can’t reveal here what the note says! So that will have to remain a secret for the moment.

But then, Let Us Be True is all about secrets. Erna said in an interview that “we are all shaped by secrets we know nothing about.” Asked what inspired the book, she said, “I wanted to write a book about my mother’s generation of women. I think a lot of them experienced great loss and great hardship during the period in which they lived, whether it was the result of the Depression or the Second World War, and a lot of them kept it a secret from their kids. Just as men at the front kept their experiences there to themselves, a lot of these women didn’t share what happened to them.”

As a prairie girl myself—even though I’ve lived in the Maritimes for many years and I love it here, I expect I’ll always feel like an Albertan, a “Come-From-Away,” in Nova Scotia—I appreciated Erna’s descriptions of the “wild and wide-open beauty” and the “sudden cruelty” of the prairies. And as someone with an abiding interest in Victorian literature, I appreciated the way the poem that inspired the title echoes throughout the story of Pearl and her family:

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! For the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain….

From “Dover Beach,” by Matthew Arnold, 1867 (The Broadview Anthology of Victorian Poetry and Poetic Theory, ed. Thomas J. Collins and Vivienne J. Rundle [Broadview, 1999])

Erna’s short stories have appeared in Room of One’s Own, Pottersfield Portfolio, and The Vagrant Revue of New Fiction. In 2006, she won the Writers’ Federation of Nova Scotia Short Fiction Award for her short story “Pearl.” She tells me she’s returned to Jane Austen’s novels many times over the years, “not just for the pleasure of re-reading them but also for inspiration in my own writing.” The combination of her fascination with Austen and her longtime interest in the history of food inspired her to write this blog post. I know she’d be glad to discuss the topic further, so please do add your comments and questions below.

Erna has spent more than twenty-five years in the film industry, writing, directing, and producing award-winning films for the CBC and other national and international broadcasters. In 2012 she won a Canadian Screen Award for Best Direction in a Documentary for her work on Smarty Plants. She wrote and directed The Changing Sea, which aired around the world and won several awards, including The Save the Seas Foundation Award. Her many screen-writing credits include the award-winning NFB documentary By Woman’s Hand and the Genie award-winning documentary A Song for Tibet.

Among the many things I love, food, food history, and Jane Austen rank high on the list. So imagine my surprise when I discovered, on re-reading Pride and Prejudice, that the woman who penned some of my favorite novels seldom dwells on the culinary details of the Georgian table, and spends even less time talking about cooking and kitchen work. But while Pride and Prejudice may have little in the way of menus, there’s no doubt that the lives of Lizzie, Jane, and the rest of the Bennet clan are measured out in the rhythm of their daily meals. Breakfast took place as late as 10 a.m. because of the preparations required, and dinner, the next substantial meal of the day, was slowly moving from its midday slot closer to 5 or 6 p.m. in well-to-do homes. Dinner might be followed a few hours later by tea, or if one were very fortunate, a late night supper party after a vigorous round of bridge, or dancing.

And just as dancing and card parties were a welcome reprieve from endless hours spent at embroidery, reading, hat making, or strolling in the garden, regular meals also provided their own particular delights: good food, combined with news, gossip and the conversational distractions of the occasional guest. Small surprise, then, that some of Austen’s funniest and most wickedly satirical scenes occur around the dining table. Think of Mr. Collins’ hilarious first dinner with the Bennet family or Lizzie supping with the poisonous Lady Catherine de Bourgh at Rosings.

But if the table offered sustenance, diversion, and the occasional encounter with the prejudices associated with privilege, the Georgian dining room was also a battleground for proud hostesses. And few characters epitomize the preoccupation with one-upmanship associated with the dining table better than Mrs. Bennet herself.

Her duties as a hostess were to offer an excellent meal and put guests at their ease, but Mrs. Bennet is not above the occasional barbed comment, especially if it is aimed at Mr. Darcy. Neither does she hesitate to boast about the quality of the meal, and the compliments bestowed on her table, by the very guest she has just attempted to skewer: “The venison was roasted to a turn—and everybody said they never saw so fat a haunch. The soup was fifty times better than what we had at the Lucas’s last week; and even Mr. Darcy acknowledged that the partridges were remarkably well done; and I suppose he has two or three French cooks at least” (Chapter 54 [Penguin, 1983]). Mrs. Bennet’s triumphant summary of this particular dinner party is also one of the few times in Pride and Prejudice that Austen makes direct reference to what was actually on the table. Which brings us to the matter of food itself.

While methods for food production improved over the course of the 18th century, significant innovations in kitchen hardware, like cast iron ranges, were still a few decades away. In 1813, when Pride and Prejudice was published, most people were still cooking on open hearths, using raised grates, pots, cast iron pans, spits for roasting, cauldrons to heat water and metal stands for bread toasting. People with some means might also have had an indoor brick oven for baking bread and pastries. Those who couldn’t afford one would have relied on deliveries from the local baker or rented the use of his ovens to bake their own bread. (For more on bread making see Episode 1 of the BBC 2 series “Victorian Bakers.”)

Innovation remained the purview of the wealthy, whose kitchens featured not only wood stoked ovens and roasting spits for meats but also metal hobs. A Georgian hob was simply a flat iron pan used for heating pots, installed at the back or side of a fire over a grate. If you were wealthy, you might even have one installed on top of your brick oven. Whether the Bennet hearth had a hob is anybody’s guess, but we definitely know they had a cook, as Mrs. Bennet is quick to inform the obsequious Mr. Collins. After admiring all of the furniture he will one day inherit, he then turns his attention to the meal: “The dinner … was highly admired, and he begged to know which of his fair cousins, the excellence of the cooking was owing. But here he was set right by Mrs. Bennet, who assured him with some asperity that they were very well able to keep a good cook and that her daughters had nothing to do in the kitchen” (Chapter 13).

So what, exactly, might that cook and kitchen have produced? No doubt as excellent a plate of food as was humanly possible, if Mrs. Hill, the Bennet housekeeper, wanted to keep her job. According to Samuel and Sarah Adams’ book The Complete Servant, published in 1825, the ultimate responsibility for everything in the household from cleaning and cosmetics production to what the kitchen produced was the housekeeper’s. Although Hill wouldn’t have cooked the meals, she would have stocked the larder and stillroom and she may also have prepared essential and expensive ingredients like spices and sugar. Spices were commonly bought whole and had to be grated, pounded or ground, depending on the next day’s meals. The same was true for sugar, which was bought in cakes that had to be broken, pounded then rolled into fine grains. Pickling and preserving were also within a housekeeper’s purview, as were laying the table (in the absence of a butler), carving cold meats and bread, and ensuring the quality of each and every dish that emerged from the kitchen. And what is truly remarkable, given the rudimentary state of the kitchen, was the sheer volume and intricacy of the dishes the early 19th century cook was able to produce. (Read more about Samuel and Sarah Adams’ The Complete Servant at Austenonly.com.)

The cooks’ larders at both Longbourn and Pemberley would probably be equal in their array of British staples, if not their volume, but Mr. Darcy’s dinner table would likely feature more “novel” recipes brought back from continental tours. As Mrs. Bennet’s comment on the possible ethnicity of his cooks suggests, French cuisine was all the rage during the late Georgian period. Thus the reaction of the inevitably intoxicated, Mr. Hurst, who decides he has “nothing further to say” to Lizzie, when she states her preference for plain cooking, over a French “ragout” (Chapter 8).

But the “plain cooking” featured at the Bennet table would probably be a good deal tastier and more complex than Lizzie suggests. After all, Mrs. Bennet has appearances to keep up. So her family and guests are likely beneficiaries of the ginger, cinnamon, curries and other spices being shipped into England by the East India Company. Hannah Glasse, for example, included a recipe for a mild curry in her cookbook, published in 1751. And like all good dinner tables, Mrs. Bennet’s would have featured the four courses mentioned in her menu.

The first course was a soup: in summer, perhaps a delicate potage of sorrel leaves cooked in butter and minced onions, then finely chopped, simmered in chicken broth, and served with buttery croutons. Dorothy Hartley’s wonderful book Food in England (1954) features this traditional soup recipe and many others like it, scattered throughout her chapter on vegetables. The second course was placed on the table with the first, and unfortunately, often wound up tepid rather than hot. It usually featured roasted meat like beef, mutton or Mrs. Bennet’s prized venison, plus numerous side dishes from gravies and creams to jellies and vegetables. The second course was followed by a lighter—and I use that term loosely—third serving of poultry, or fish. Mrs. Bennet has her perfectly cooked partridges, but on another occasion, she might have presented this red mullet recipe, from Hartley’s book, which suggests that each fish be cooked whole, “in oiled paper, with a nub of butter, steamed in its own juices and finished with a little white wine.” This too would have been accompanied by at least half a dozen side dishes. (See Dorothy Hartley, Food In England: A Complete Guide To The Food That Makes Us Who We Are [Piatkus, 2012].)

Feeling full yet? I hope not, because there’s still another course to go—dessert.

In her book Jane Austen and Food (1995), Maggie Lane says a traditional dessert of the period generally featured a display of finger foods: fresh or dried fruit depending on the season, small confections, cheese and perhaps a handful of walnuts. It’s difficult to say whether a larger, sugar-rich dessert, such as a spoon-eaten pudding or syllabub, would have been placed on the Bennet table, despite the fact that these desserts were becoming increasingly popular and cheaper to make by the beginning of the 19th century. In World History: A New Perspective (2001), historian Clive Ponting indicates that by 1770 Britons were already consuming five times the amount of sugar eaten in 1710, thanks to the horrors of a slave-fueled, sugar trade. So while the Bennet household may have cleaved to tradition, a larger, richer desert is certainly a possibility.

Hartley describes a number of these desserts. Few are more enticing, I think, than this one, called “Damask Cream,” a “junket” or set pudding that purportedly originated in Bath: “Cook cream gently with mace and cinnamon til delicately flavored. Add sugar and rosewater and set with a fine rennet (used to make both clotted cream and cheese). When cold, flood over it soft cream flavored with rosewater and lightly strewn with powdered sugar. Serve surrounded by deep damask rose petals.” Decisions about exactly how much sugar and cream and what measure of spice and rosewater were presumably left to the palate of the cook, as standardized kitchen measurements were still some way off.

Hartley’s Food in England is peppered with countless recipes like this one, many of which originated in Bath, a fashionable destination for so many of Austen’s characters. And that’s because Bath, in Hartley’s opinion, was the center for the “best of everything in England,” especially when it came to food. Situated on the Roman road that marked the route north to Ireland, Bath was also on the drover roads that brought “the finest meat from the Welsh grazing grounds” to city markets further south. But meats were not the only goods that made their way through the ancient spa town of Bath, as Hartley explains: “The apples of Glastonbury brought great flagons of cider, and from the warm yellow Cotswold walls came apricots, hot from the sun, and cherries and plums. Up from Devon and Somerset came the finest creams, bowls of fermentry (yeast) and junket rennets … (and) from Bristol way came scents and spices and fine imported wines—brought by cargo boat from overseas.”

So whether drawn by the “urge to mate” that sent so many matrons and their daughters migrating to the city for the season, or by matters of ill health, taking the waters at Bath may also have provided an excellent antidote to what Hartley describes as “the drunkenness and overeating of the period.” But getting to Bath, or any other destination further than a few miles away, meant, for women at least, the discomfort of coach travel. This kind of travel included stopovers at inns, like the one in Lambton where Lizzie holidays with her aunt and uncle.

So what might have been on the menu at the Lambton inn? Once again Hartley provides insight through the diary of a certain Mr. Young, who is also “travelling in the north.” Like all travellers, Young seems focused on finding the best food at the best prices and recording it all for future reference. At Rotherham he notes that the inn is “Very disagreeable and dirty,” with a less than stellar menu of “hashed venison, potted mackerel, cold ham, cheese and melon.” Castle Howard is described as “An excellent House but dear and with a saucy landlady,” which may explain why, in this case, he fails to mention the menu! A few towns later, Mr. Young seems to have struck gold at the inn in Carlisle which is pronounced “good,” with a dinner that included “broiled chicken and mushrooms, plover, a plate of sturgeon, tart, mince pies and jellies.” I like to think that the inn at Lambton would offer similar good food and service to Lizzie and her charming aunt and uncle, the Gardiners.

And yet hidden behind the idyllic rhythms of the Bennet’s substantial meals, the coming and goings of their domestic, financial and romantic concerns, lies something very different. Slowly, but surely, the broader rhythms of a rural life that had endured for 100s of years were changing. Enclosure, which gobbled up small landholdings and reorganized them into large farms, was well underway by 1813. And an industrial revolution that would transform both country and town, and displace countless rural craftsmen from weavers to bakers, was proceeding apace. So while the Bennets sipped at their soup, small hold farmers and farm laborers were leaving the country and moving into cities, to join the growing legions of urban poor. Instead of producing their own food, they were now forced to buy it. And what they bought was often substandard. According to The Royal Society of Chemists, the fight against food adulteration had not yet begun, so buyers were often subjected to bread made from flour rendered cheaper and whiter by the addition of chalk or alum. In her article “The Working Classes and The Poor,” Liza Picard also makes reference to the sometimes dubious offerings of costermongers, street vendors who sold everything from “oysters, hot-eels, pea soup and fried fish to pies, puddings, sheep’s trotters, pickled whelks, gingerbread, baked potatoes and crumpets.” Assuming, of course, that you could afford to buy them.

Austen’s witty mocking of the privileged classes gave way to a new kind of novel later in the 19th century. The “social novel” focused its attention on the lot of the poor, those exploited by the very classes at which Austen had aimed her pen and by a new class of urban industrialists. Among these novels are Elizabeth Gaskell’s Mary Barton, Charlotte Brontë’s Shirley, and the novels of Charles Dickens. But whatever their focus, and whatever the century, the subject of food—whether its absence, benefits, or evil associations—would remain as integral a part of the fictional world as the real.

May 11, 2016

Spring in Rainbow Valley

I spent last weekend in Prince Edward Island and one of the books I read was L.M. Montgomery’s Rainbow Valley, the seventh book in the “Anne” series. I am slowly—very slowly!—working my way through the series, inspired by the Green Gables Readalong that happened last year from January to August.

French River on Friday evening

I didn’t get to Anne’s House of Dreams until September, and then I wrote about Anne of Ingleside in October after a trip to PEI—and then I spent the whole winter focusing on Jane Austen’s Emma. I’m still reading and writing about Emma Woodhouse because I’m working on a presentation for the JASNA AGM in October. But it was a pleasure to return to Montgomery for a few days and to take pictures in PEI.

I decided to focus on passages that describe what spring looks like on the Island. The novel opens on “a clear, apple-green evening in May,” when “Four Winds Harbour was mirroring back the clouds of the golden west between its softly dark shores.” Anne tells her friend Miss Cornelia her children have “rushed down” to Rainbow Valley for the evening because “They love it above every spot on earth,” and her housekeeper Susan Baker says the children “love it too well”: “Little Jem said once he would rather go to Rainbow Valley than heaven when he died, and that was not a proper remark” (Chapter 2).

This is Summerside Harbour in the afternoon, not “Four Winds Harbour” in the evening, but I like the way the harbour mirrors back the clouds.

In June, the valley is “an entirely delightful place,” when the wind is “laughing and whistling,” the white cherry trees are “mistily white,” and the “blossoming orchards” are “sweet and mystical and wonderful, veiled in dusk” (Chapter 29). It isn’t always a happy place, however. Not for the children on the evening when “Mary Vance froze their blood with the story of Henry Warren’s ghost” (Chapter 29), not for Rosemary West, when she thinks of her lost love (Chapter 32), not for the girls who shiver when Anne’s son Jem talks about longing to be a soldier and her son Walter talks about the Pied Piper coming to summon the young men of Glen St. Mary to follow “round and round the world” (Chapter 35). From the section on Rainbow Valley in Mary Henley Rubio’s biography Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings (2008) I learned that while the novel is set before the Great War, Montgomery finished writing it about six weeks after the war had ended.

My family and I went for a walk on Saturday morning at Cavendish Grove, which is just up the road from Green Gables. There was an amusement park called “Rainbow Valley” on this spot years ago. I visited it once, when I was eight, and I don’t remember any of the rides, but I do remember the pond and the pedal boats.

Cavendish Grove. The pond is still there, but the pedal boats are long gone.

We followed the Cavendish Grove trails until we got to Cavendish Beach.

I also took pictures of “The Lake of Shining Waters” in Park Corner, near the Anne of Green Gables Museum. Seeing the lake and the site of the “Rainbow Valley” amusement park prompted me to revisit an essay I read a few weeks ago in Anne’s World: A New Century of Anne of Green Gables (2010). In “On the Road from Bright River,” Alexander MacLeod talks about Anne’s “power to remake and imaginatively transform the world that surrounds her” as she christens the “Avenue” “The White Way of Delight” and renames “Barry’s Pond” “The Lake of Shining Waters.” He says “The same process repeats itself outside the novel. Just as Anne, the character, rewrites Avonlea to make the landscape correspond with her pre-existing romantic ideals, so her story initiates an identical and equally problematic cycle of geographical transformations that continue, literally, to ‘take place’ in the real world of contemporary Cavendish.”

He points out that “it is important to remember that Matthew does possess his own way of understanding and caring for his local social space.” Anne confidently replaces existing place names, and MacLeod asks, “Where does Barry’s Pond go after Anne is finished with it? Does her innocent power actually give her an inherent right to this landscape? What kind of world is she erasing and replacing? What is being cast away as Matthew silently acquiesces to his talkative companion? And are we, as readers, required to come along for this ride?”

“The Lake of Shining Waters.” I don’t know what it was called before it was renamed in honour of the lake/pond in Montgomery’s novel.

In Rainbow Valley, Anne’s children know and are fond of “all the spots their mother had loved so well in her girlhood at old Green Gables,” including Lover’s Lane, the Dryad’s Bubble, the Lake of Shining Waters, and Willowmere, but her daughter Nan insists that “none of the Avonlea places are quite as nice as Rainbow Valley.” It’s Walter who named the valley, after the children saw “the beloved spot arched by a glorious rainbow, one end of which seemed to dip straight down to where a corner of the pond ran up into the lower end of the valley” (Chapter 3). The valley doesn’t seem to have had a name before Walter chose this one. Susan Baker is afraid “that boy is going to be a poet,” and she tells Anne, “I never knew any good to come of writing poetry, and I hope and pray that blessed boy will outgrow the tendency. If he does not—we must see what cod-liver oil will do” (Chapter 7).

Speaking of naming and renaming and reimagining places, I found it interesting to learn from Rubio’s biography that while the setting of Rainbow Valley is “‘Glen St. Mary,’ not far from ‘Avonlea,’ … the people of Leaskdale still point to the Ontario valley that they believe was the basis for Rainbow Valley.” One of the books I’m planning to read soon is L.M. Montgomery’s Rainbow Valleys, edited by Rita Bode and Lesley Clement, which focuses on Montgomery as an Ontario writer. It was published last fall and I’ve been meaning to read it but haven’t got to it yet. I must get a copy. Have any of you read it?

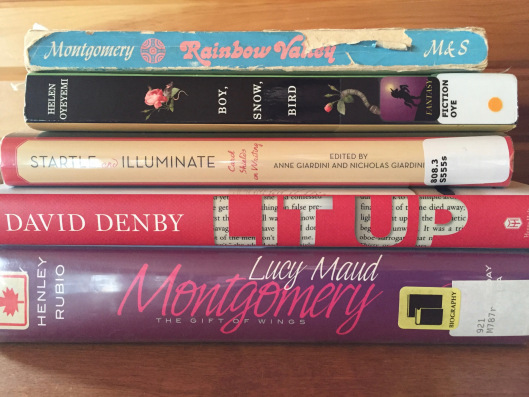

Here are the other books I started to read while my family and I were in PEI. I couldn’t choose one or two so I just took all of them. (My excuse is that it was raining when we left, and I thought it was possible we might spend the whole weekend inside, reading.) Rainbow Valley is the only one I finished while we were there.

This is what the weather looked like when we crossed the bridge to PEI on Friday. (We were really happy to see that bright blue sky on Saturday.)

Helen Oyeyemi’s novel Boy, Snow, Bird had me hooked from the first page. “Nobody ever warned me about mirrors, so for many years I was fond of them, and believed them to be trustworthy.”

David Denby spoke in Halifax last week and I bought his new book, Lit Up: One Reporter. Three Schools. Twenty-Four Books That Can Change Lives. It was a wonderful talk and I love what he says in the introduction about how “A child held, read to and talked to, undergoes an initiation into a useful life; she may also undergo an initiation into happiness.” If I were adding to the reading lists provided by the teachers at the three high schools he visited when he was working on this book, I’d include Pride and Prejudice, Anne of Green Gables, and Jane Eyre, and several more works by women. I don’t think there were nearly enough women writers on any of the three lists, and all three of those novels certainly have the power to change lives. I really like Denby’s New Yorker essay on the pleasures of listening to Austen’s Emma. (There’s another novel that can change lives, with its focus on the importance of self-knowledge.)

I also started reading Startle and Illuminate: Carol Shields on Writing, edited by Anne Giardini and Nicholas Giardini, which I’ve been looking forward to for months because I’m a longtime fan of Carol Shields, particularly her novels The Republic of Love and The Stone Diaries. It was published a couple of weeks ago, and although I’m reading a library copy, I can tell already that this is a book I’ll want to buy for my own collection. Here are a few lines that I’ll want to underline as soon as I get my own copy.

“Most of us end up seeing our lives not as an ascending line of achievement but as a series of highly interesting chapters.”

“I knew very early that writing was my vocation because everything else I tried—music, handicrafts, sports—went badly. Only when I was writing did the awkwardness diminish.”

“I saw that I could become a writer if I paid attention, if I was careful, if I observed the rules, and then, just as carefully, broke them.”

On the way to Cavendish Beach

So I have lots of reading ahead of me this month! What are you reading these days? I’m looking for suggestions for the summer. Rereading The Republic of Love is at the top of my list and I’d love to hear your recommendations. And I’d better put Rilla of Ingleside on my list as well, now that I’ve finally finished reading Rainbow Valley. It’s set during the First World War, and while I remember some of the things that happen to the Blythe family during the war, there’s a good deal that I’ve forgotten. I’m also keen to read about Rilla’s ambition, or apparent lack thereof, now that I’ve written a little bit about Anne and ambition.

That reminds me that I also intended to say (somewhere in what’s turned out to be quite a long blog post!) that I’m speaking at a JASNA Nova Scotia meeting this weekend. My talk is “Austen and Ambition,” which I presented in Philadelphia last year. If you’ll be in Halifax on Sunday afternoon and you’d like to attend, please let me know—by commenting here or sending me an email (semsley at gmail dot com)—and I’ll send you the details.

Oh, and I wanted to mention that this month marks the 202nd anniversary of the publication of Mansfield Park; if you missed the blog series I hosted in 2014 for the 200th anniversary, or if you want to revisit some of the guest posts, you can find everything listed here: An Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Malpeque, Friday evening

April 15, 2016

A Man of Genius: Q&A with Janet Todd

After Janet Todd wrote about “English verdure” for Emma in the Snow, I wanted to know more about her new novel A Man of Genius and the connections between her career as a scholar and critic and her career as a fiction writer. Today I’m pleased to share with you the conversation Janet and I had recently about her work. The US launch for A Man of Genius is in New York on Thursday, May 5th at Book Culture (536 West 112th Street).

Janet is the author and editor of many books on Jane Austen and other writers, including biographies of women writers from Aphra Behn to Mary Wollstonecraft. She spent her teaching career mainly in the US and the UK and in her retirement she’s focusing on writing fiction. Her last two academic positions were as Professor of English in the University of Aberdeen and President of Lucy Cavendish College, Cambridge.

Here’s the description of A Man of Genius, published by Bitter Lemon Press:

A Man of Genius portrays a psychological journey from safety into obsession and secrecy. It mirrors a physical journey from flamboyant Regency England through a defeated Europe struggling to create a new order after the upheavals of the Napoleonic conquests.

Ann, an author of cheap Gothic novels, becomes obsessed with Robert James, regarded by many, including himself, as a genius; she is captivated by his Romantic ideas, his talk, and his band of male followers. The pair leaves London for occupied Venice, where Ann tries to cope with the monstrous ego of her lover. The relationship grows tortuous as Robert descends into near madness. Forced to flee with a stranger, she delves into her past, to be jolted by a series of revelations—about her lover, her parentage, the stranger and herself.

What inspired you to write A Man of Genius?

All my life I’ve been inventing stories. From as young as I can remember I wanted to be a writer of some sort, first an epic poet like Milton, then a lyricist in Wordsworthian mode, then later a novelist on the scale of War and Peace. After that came reality and the day job.

From time to time I started novels, still where my heart lay, but other duties were always there, always demanding. I never made time to finish and polish the fiction I’d started. And of course it was far easier to write with a firm contract from a university press than to take a leap in the dark by seeking a publisher for a first novel. A Man of Genius touches on many topics that have long concerned me, the power of memory and the confusion of memory—what is one’s own, what the culture’s, what other people’s—and how difficult it is to know the difference between faithful love and addiction to a harmful relationship.

I’m always interested in human complexities and eccentricity, and both are, for me, best explored in fiction.

You’re the author and editor of several scholarly books. What are some of the connections, and contrasts, between your work as a critic and scholar and your work as a novelist?

I arrived in the USA in 1968 after working for some years in Africa. I rather fell into academics.

Fortunately it was the beginning of the feminist movement in universities, and there was much to do: much to fight for and much to investigate within the academy, which at that time was patriarchal through and through. So I found that research was perhaps what I wanted to do just then; novel-writing had to be put on hold.

I realised how many wonderful women writers were out there in the centuries that most interested me—the late seventeenth to the early nineteenth: “Dryden to Byron” as it was termed then—or, as I increasingly saw it, “Aphra Behn to Mary Shelley.” Women had largely dropped from the canon and were unread.

So in the greater intellectual freedom I found in the US compared with Britain, I began teaching and doing research into women writers and in men’s depiction of women. I started the first journal in English devoted to female authors, published a book about women’s relationships, then moved on to large-scale editing projects of important authors, including Jane Austen, and finally to biographies.

A Man of Genius is dear to my heart since, although the story and characters are entirely fictional, its background and setting relate to the period and writers I have been studying and teaching. And the central relationship between a male “genius” and a female hack writer, although, as I repeat, entirely fictional, draws a little on the fraught relationships I have described in my biographies.

For instance, Death and the Maidens portrays the effect of a real and haunted “genius,” Percy Bysshe Shelley, on Fanny, eldest daughter of the great feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft, as well as on her half sister Mary Shelley and on his first wife Harriet. In A Man of Genius I ask what occurs when the assumed genius begins to doubt his superior powers and when his lover fears her idol may have clay feet. I wanted to investigate not simply a relationship where one person abuses another but also where both feel for a time exhilarated, then are both simultaneously damaged. I also wanted to portray a woman whose head is filled with stories, a woman who never plays safe, who makes mistakes, but who has the resilience always to go on and try again.

You describe A Man of Genius as your “first original novel”—how is it different from Lady Susan Plays the Game, which you published in 2013?

Lady Susan Plays the Game was a spin off from Jane Austen. As you know, there’s an enormous industry of Austen prequels, sequels, retellings, transformations, mashup etc. I wrote about some of these for my edited Cambridge Introduction to Pride and Prejudice. Although “Lady Susan” has come into the public arena with the recent film, it was little known among general readers, even those who much admired Jane Austen. It’s a skilful work, like everything Austen penned, but it’s in letters and can only do certain things. It gives voice to the letter writers but doesn’t describe the inner life of other characters. So I thought I would—primarily for enjoyment—take the skeleton of the tale and flesh it out, and also give a back story to the rather hapless daughter. In short, the plot and characters are Jane Austen’s, but I added some sexual shenanigans and new voices, while suggesting reasons for Lady Susan’s character and debts. However I didn’t deviate from the plot Jane Austen created.

A Man of Genius is entirely my own imaginative work, so is very different. It’s also much darker, more Gothic. It’s set in the Regency period, now so associated with Jane Austen, but it upfronts the more violent, oppressive side of this troubled post-war time. It’s a world of the working middle class in London, not of the rural gentry.

I then take my characters outside England to Venice for a large part of the story, a Venice that fascinates then as now, but which never gives up all its secrets. In this watery city my characters find much about themselves, feel the allure of the magical place, but never quite get to the source of the mysteries that surround them.

What’s some of the best advice you’ve received about writing, for fiction or non-fiction (or both)?

I was an only child and we moved often, so as a young girl I had very little chance of mentors—I changed school on 13 occasions and in different countries!

As I said, I’ve been writing most of my life. I don’t find writing therapeutic in the sense of being confessional and cathartic. I just find it all-consuming, pleasant when life is going well and hugely useful when it’s not!

The only direct advice I have had about fiction-writing has come from two crime writers I met recently while president of Lucy Cavendish College: P.D. James, now sadly no longer with us—though her wonderful novels are still much read—and Sophie Hannah. Phyllis said that you should have a body in the first chapter and Sophie told me to grab the reader on the first page. Both good ideas.

The Romantic poets declared they wrote from sudden inspiration, though there’s proof that they often corrected. Jane Austen was honest about her revising: she honed Pride and Prejudice over fifteen years and corrected her later novels as well, as you can see from the cancelled pages of Persuasion. For me revising is of the essence—and something I greatly enjoy. I recommend it.

Now I think of it, I suspect that Jane Austen herself indirectly gave me as good advice as any. She told her novel-writing niece to convey her sense “in fewer words,” get details of time and place correct, and realise that what might be true in life doesn’t necessarily work in fiction. Finally, if you don’t know what happens in Ireland, keep your characters in England!

Janet has kindly agreed to answer further questions, so please do comment here if you’d like to ask her about her work. I enjoyed Lady Susan Plays the Game and I’m looking forward to reading A Man of Genius. Thanks very much, Janet, for visiting the blog today—and congratulations on what sounds like a fascinating novel!

April 1, 2016

The Art of Photography

During the winter, when I was hosting Emma in the Snow and taking pictures of snow in Alberta and Nova Scotia to accompany some of the blog posts in the series, I was also taking an online photography class from Joy Sussman. Last fall I signed up for my first ever photography class, and it was such a wonderful experience—both inspiring and challenging—that I registered for a second class with Joy in the winter.

The first class was called “Take Better Photos of Nature and the World Around You” and the second was “The Art of Photography.” Joy also teaches a class called “The Charm of Children: How to Take Better Photos of Babies and Kids,” and there’s more information about all three of her classes at her blog, Joyfully Green.

Joy included my photo of the view from Luckett Vineyards (above) in the Annapolis Valley in her online gallery of student work from the nature class; it also includes photos by Lisa Epstein, Margaret Strafaci, Lindy Warner, Jerri DeCarolis, Mary O’Brien, Jo Anne Dobis, Connie Lissner, Debbie Bagley, Shelley DuPont, and Kathy Stinson. I chose that same photo for the new “Events” page I created on my website a few weeks ago, because I’ll be speaking at the Jane Austen Society of the UK conference in Halifax in June of 2017, and lunch at Luckett’s is part of the conference programme.

I thought I’d share a few of my photos from “The Art of Photography” here. If you’d like to see some of my dahlia photos from the first class, you can find them in my blog post “L.M. Montgomery and the Halifax Public Gardens.” I’ve learned so much from Joy and from my fellow classmates and—while I did enjoy taking photos of snow—I’m delighted that spring is here, because I’m looking forward to taking more photos of flowers (especially now that I have a macro lens).

Minimalism:

Looking for shapes and patterns:

Experimenting with filters (not my favourite, as I almost always prefer a minimalist approach to editing, but it was good to try something new). This is the MacDonald Bridge in Halifax:

Here are some of my Mary Pratt-inspired photos of jelly jars, pears, and apples. I saw the Mary Pratt exhibition at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia in 2014 and I loved both her paintings and the book that accompanied the exhibition. One of her jelly jar paintings appears on the cover of the book, which you can see here, and Kerry Clare wrote a wonderful blog post in which she compares still life paintings and blog posts: “Like Pratt,” she says, bloggers are “crafting something permanent out of the whirl of the ephemeral,” with “each individual post its own still-life.”

Sarah Fillmore writes that Pratt’s “painting of the jelly jar is really about the way the light shines through the glass, the way that light is preserved, like the jelly, for all time” (“Vanitas,” in Mary Pratt [Goose Lane Editions, 2013]). This is my own attempt at preserving light.

If you’ve seen Pratt’s paintings “Pears #1” and “Pears #2,” you’ll know why I chose this particular dish for my still life photos of pears and apples.

Here’s my favourite of all the photos I took for this class. No filter, just some perfect late afternoon light in my dining room. You can probably tell that I had a lot of fun taking this class!

March 18, 2016

Frank Churchill Gets a Haircut

Paul Savidge is a life member of JASNA and the Regional Coordinator of the Eastern Pennsylvania Region. He’s passionate about “Jane Austen, modern architecture and baseball (in that order).” Two years ago on the JASNA tour, he travelled to London, but, he tells me, he didn’t get a haircut. I forgot to ask if he bought a piano while he was there.

Paul Savidge is a life member of JASNA and the Regional Coordinator of the Eastern Pennsylvania Region. He’s passionate about “Jane Austen, modern architecture and baseball (in that order).” Two years ago on the JASNA tour, he travelled to London, but, he tells me, he didn’t get a haircut. I forgot to ask if he bought a piano while he was there.

When he’s not thinking of Jane Austen, Paul works as a lawyer for a gene therapy company in Philadelphia. He’d like to invite everyone to Jane Austen Day in Philadelphia on April 16th to celebrate “Emma: 200 Years of Perfection” with guest speakers Claudia Johnson, John Mullan, Michael Gamer, and William Galperin. Registration information and more details about the event are available on the JASNA Eastern Pennsylvania website.

On the last day of Emma in the Snow, it’s my pleasure to introduce Paul’s guest post on Frank Churchill’s haircut. The photos of Paul and of the Esherick House in the snow were both taken by Dan Macey (who, many of you will remember, wrote a guest post on mutton earlier in this series).

Esherick House, Philadelphia

The great irony of Emma is that its heroine who “had lived nearly twenty-one years in the world with very little to distress or vex her” is repeatedly vexed by her misunderstanding of situations she not only believes she comprehends, but believes are under her control (Volume 1, Chapter 1). It is Mr. Elton who perhaps first seriously vexes Emma Woodhouse when he suddenly makes “violent love to her” in the carriage on the way home from dinner at the Westons’ (Volume 1, Chapter 15). The scene is hard to read without feeling some embarrassment for Emma, who may be the only person on earth to suppose that Elton would prefer Harriet Smith, “the natural daughter of nobody knows whom” (Volume 1, Chapter 8) to herself, “handsome, clever, and rich” (Volume 1, Chapter 1). But this confusion is just a warm-up for the real vexation that awaits Emma at the hands of Frank Churchill, who finally arrives in Highbury in Volume Two after a big build up in the first volume.

Things between Emma and Frank get off to a good start and Emma “felt immediately that she would like him” (Volume 2, Chapter 5). Almost as quickly, Emma’s very good opinion of Frank is “a little shaken” when he announces that he will travel sixteen miles (and back) to London on a very personal errand. “A sudden freak seemed to have seized him at breakfast, and he had sent for a chaise and set off, intending to return to dinner, but with no more important view that appeared than having his hair cut” (Volume 2, Chapter 7). There has been ongoing speculation on what really motivated Frank’s sudden trip to London with the consensus being that he went primarily to purchase the pianoforte for Jane Fairfax that shows up mysteriously later in the novel (and causes more vexation for Emma). Other theories for the trip focus on hidden meanings in the words “hair cut,” as Regency era slang for an illicit assignation or, more imaginatively, as a play on the word “hair” and its near homophone “heir,” thereby suggesting that Frank may have been in London to plan the demise of Mrs. Churchill who stood in way of his happiness and his “heir cut.” Whatever actually drives Frank’s quick departure for London, he in fact comes back that evening with a trim. “He came back, had had his hair cut, and laughed at himself with a very good grace, but without seeming really at all ashamed of what he had done” (Volume 2, Chapter 8).

Emma is very disconcerted by Frank’s trip. Although she finds no particular harm in such an errand, Emma feels that “there was an air of foppery and nonsense in it which she could not approve.” To Emma, Frank’s haircut is an unbecoming and vain extravagance: “it did not accord with the rationality of plan, the moderation in expense, or even the unselfish warmth of heart which she believed herself to discern in him yesterday.” While Mr. and Mrs. Weston each excuse Frank’s trip to London as “a very good story” or as evidence that “all young people would have their little whims,” Mr. Knightley is not as forgiving and says under his breath (but loud enough for Emma to hear) that Frank is “just the trifling, silly fellow I took him for” (Volume 2, Chapter 7). Mr. Knightley’s unwitting support of Emma’s growing suspicion of the impropriety of the matter troubles her further. The scene is important to the maturation of the heroine as she begins to see that people are more complicated than she had presumed. Could Frank be both selfless and vain, both rational and trivial? And why wasn’t the Highbury barber good enough for him anyway?

Frank’s trip to London for a haircut undoubtedly resonated with many Regency era readers of Emma. During Austen’s lifetime, men’s fashions and grooming habits underwent a dramatic change and gentlemen became more interested in their appearances. When Knightley calls Frank a “silly fellow” for spending the time and money to get a haircut in London, he may be implying that Frank is a dandy or, worse, a fop (and this is precisely what Emma fears.) The dandy first appeared in London in the 1790s and is distinguishable from a fop in that a dandy’s clothes were considered more refined and sober.

The revolution in men’s hairstyles was also seismic. According to an excellent article on men’s hairstyles of the 19th century on the Jane Austen’s World blog, by the end of the 18th century, fashionable gentleman no longer wore the wigs that had been popularized by the balding Louis XIII. (The blog post includes images of several different hairstyles.) Wigs faded from fashion as men of fashion “began to wear short and more natural hair … sporting cropped curls and long sideburns in a classical manner much like Grecian warriors and Roman senators.” The death knell of the wig was the one guinea tax on hair powder instituted by William Pitt in 1795, which gave men who were perhaps more fiscally conservative than fashion-conscious a reason to abandon wigs. In Eavesdropping on Jane Austen’s England (2014), Roy and Lesley Adkins recount that instead of paying the tax, “the Whigs cut their hair short, in a style called a la guillotine, after those forced to have their hair cropped before being executed during the French Revolution. Those Tories who paid the tax were called guinea pigs.” When the tax was finally abandoned in 1869, reportedly less than a thousand people in England were still wearing wigs. In 1816, the young Frank Churchill certainly did not wear a wig, although Mr. Weston and Mr. Woodhouse might have been holdovers.

The leading dandy of the day, George Bryan “Beau” Brummel (1778 – 1840) was highly influential in all matters of grooming and men’s fashion. Brummel meticulously kept his hair shorter and his face clean-shaven. “Every morning [Brummel] examined his face in a dentist mirror and plucked any remaining stray hairs with tweezers.” By the time Emma was published, almost all gentlemen sported sideburns of various lengths, but other types of facial hair such as mustaches or beards were decidedly unfashionable. Brummel sported the so-called Brutus hair cut, which had a disheveled look that ironically took a great deal of effort to achieve and maintain. “Men used an oil or pomade made of bear fat to achieve a natural tamed wildness. Since hair was rarely washed, night caps were worn to prevent soiling pillows and doilies protected the backs of chairs.” Another popular hairstyle of the day was the Titus, which was cropped short all around with curls combed forward to resemble the hairstyle of Roman Emperor Titus.

As wigs gave way to natural hairstyles, the role of barbers also changed. In his seminal work Georgian England (1931; reprinted 2008), Albert Edward Richardson notes that in the beginning of the Georgian period, “we find the hairdressers combing, shaving and blood-letting, together with hair-cutting, and the making of wigs [for men] and braids [for women].” Later, during the Regency period, a gentleman would go to a men’s barber for a shave and to have his hair washed and cut and perhaps dyed. With the rise of a generation of young men who paid more attention to their hair came luxury barbers such as William Truefitt, who opened his barbershop in the Mayfair section of London in 1805. Truefitt styled himself the barber to the English court and his shop became extremely popular among fashionable men. At barbershops, the Regency gentleman also could purchase cologne, which, as Roy and Lesley Adkins note, was “probably used more for hiding smells than creating a pleasing impression.”

When Frank returns with his hair freshly cut, he laughs at himself but he does not show any shame. Emma finds Frank’s attitude agreeable and her faith in him is restored: “I do not know whether it ought to be so, but certainly silly things do cease to be silly if they are done by sensible people in impudent ways. Wickedness is always wickedness, but folly in not always folly.—It depends upon the character of those who handle it. Mr. Knightley, he is not a trifling, silly young man. If he were, he would have done this differently. He would either have gloried in the achievement, or been ashamed of it. There would have been either the ostentation of a coxcomb, or the evasions of a mind too weak to defend its own vanities.—No, I am perfectly sure that he is not trifling or silly” (Volume 2, Chapter 8). Of course, for those of us who know that Frank is being somewhat deceitful, Emma’s certainty about his good character is amusingly vexing. Yes, Frank did get a haircut on his trip to London, but he also purchased a pianoforte for his secret fiancée.

Quotations are from the Everyman’s edition of Emma, edited by Marilyn Butler (1991).

Twenty-sixth in a series of blog posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Emma. To read more about all the posts in this series, visit Emma in the Snow. I’m so sad that we’re at the very end of the series! But I’m tremendously grateful to all of you for celebrating Emma with me, by reading along with us, writing guest posts and comments, contributing photos, and sharing links to the series with other readers.

I had thought we might have a “flurry” of posts this week, but illness or other commitments prevented a few people from writing for the series, and as it turns out, we’ve ended up with exactly two posts every week, from the launch on December 23rd with Nora’s contribution to Paul’s guest post today. (I did see a few snow flurries here in Halifax yesterday morning, and then we got quite a bit more snow before it was washed away by rain last night.)

The snow was just starting when I visited Horseshoe Island Park yesterday

Late afternoon snow

The last post for my Mansfield Park series in December 2014 coincided with the end of the novel’s anniversary year; in this case, however, the celebrations for Emma’s 200th anniversary will continue long after the end of “Emma in the Snow.” I’m excited to read more about the “Emma at 200” exhibition at Chawton House Library, for example, and I wish I could make the trip to England this year to see it, and I also wish I could go to Philadelphia for the Jane Austen Day that Paul is coordinating. I’m really looking forward to attending (and speaking at) this year’s JASNA AGM in Washington, D.C., Emma at 200: “No One But Herself.”

Since “Emma in the Snow” is an on-line party, I won’t have to take down any decorations or wash any dishes afterwards, so I’m thinking that the first thing I’ll do after the party is reread Emma all over again. “Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable home and happy disposition, seemed to unite some of the best blessings of existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in the world with very little to distress or vex her….”

Thanks again to all of you for coming to the party, and for participating through reading and rereading and writing and talking about Jane Austen and her Emma.

March 16, 2016

Emma’s Accomplishments and Mrs. Elton’s Resources

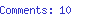

Kim Wilson is a writer, speaker, editor, tea lover, and gardening enthusiast, and a life member of JASNA. She’s the award-winning author of At Home with Jane Austen, Tea with Jane Austen, and In the Garden with Jane Austen. She lives in Waukesha, Wisconsin, and often travels to speak about Jane Austen and her world. This year, she’ll be giving lectures for a Jane Austen series hosted by the Road Scholar organization. Beginning next year, she’ll be the Regional Coordinator for JASNA Wisconsin. Her website is KimWilsonAuthor.com, and she’s on Twitter (@KimWilsonAuthor). At Home with Jane Austen, “an enchanting biographical sketch” (Library Journal), was named the #1 Non-Fiction Austen-Inspired Title of 2014 by Austenprose.

Kim Wilson is a writer, speaker, editor, tea lover, and gardening enthusiast, and a life member of JASNA. She’s the award-winning author of At Home with Jane Austen, Tea with Jane Austen, and In the Garden with Jane Austen. She lives in Waukesha, Wisconsin, and often travels to speak about Jane Austen and her world. This year, she’ll be giving lectures for a Jane Austen series hosted by the Road Scholar organization. Beginning next year, she’ll be the Regional Coordinator for JASNA Wisconsin. Her website is KimWilsonAuthor.com, and she’s on Twitter (@KimWilsonAuthor). At Home with Jane Austen, “an enchanting biographical sketch” (Library Journal), was named the #1 Non-Fiction Austen-Inspired Title of 2014 by Austenprose.

Kim tells me that while she was born in Seattle, which has a climate similar to England’s, she loves living in Wisconsin and has “even learned to love the snow and winters” in her adopted home state. I had a feeling that she’d have some lovely garden photos to share with us for Emma in the Snow, and I was right. Here’s a snowdrop photo from last week, plus a glimpse of what her garden will look like in April. I’m very happy to introduce her guest post on accomplishments in Emma.

Daffodils, scilla, and bloodroot in Kim’s garden last April

Jane Austen’s novels are filled with “accomplished” young women. The Miss Dashwoods in Sense and Sensibility are (according to the Miss Steeles) “beautiful, elegant, accomplished, and agreeable”; the Miss Musgroves in Persuasion have “all the usual stock of accomplishments”; in Mansfield Park, Julia Bertram is “a nice, handsome, good‑humoured, accomplished girl”; and in Pride and Prejudice, Georgiana Darcy is (according to her housekeeper) “the handsomest young lady that ever was seen; and so accomplished!” and Anne de Bourgh is (according to Mr. Collins) prevented only by her sickly constitution from being very accomplished indeed. In Emma, Austen crafts three young women, Jane Fairfax, Harriet Smith, and Augusta Elton, as foils to Emma Woodhouse, their accomplishments, or lack thereof, highlighting Emma’s own talents and flaws.

What constituted an “accomplished” woman in Jane Austen’s day? In Pride and Prejudice, Bingley supposes that skill in traditional female handicrafts suffices and that all young ladies are therefore accomplished: “They all paint tables, cover skreens, and net purses. I scarcely know any one who cannot do all this, and I am sure I never heard a young lady spoken of for the first time, without being informed that she was very accomplished.” Certainly many of the women in the novels are accomplished in this sense: Elinor Dashwood paints screens, Georgiana Darcy designs tables, and Elizabeth Bennet, Mrs. Grant, and Lady Bertram all embroider (as did Jane Austen herself). But Miss Bingley stipulates for more: “a thorough knowledge of music, singing, drawing, dancing, and the modern languages … and … a certain something in her air and manner of walking, the tone of her voice, her address and expressions.” And Darcy, famously, insists that “to all this she must yet add something more substantial, in the improvement of her mind by extensive reading.” Here we come closer to Emma’s own accomplishments. She plays the pianoforte, sings, draws, dances, occasionally begins, at least, what Mr. Knightley calls a “course of steady reading,” and is a remarkably elegant young woman.

The problem, of course, is that Emma, “the cleverest of her family,” is a classic underachiever, a trait sometimes seen in gifted and talented people. Her superior natural talents bring her a “reputation for accomplishment often higher than it deserved,” but because “she will never submit to any thing requiring industry and patience,” she does not come close to “the degree of excellence which she would have been glad to command, and ought not to have failed of.” Poor Mary Bennet in Pride and Prejudice works long and assiduously, proud to be known as “the most accomplished girl in the neighbourhood,” but there is no helping her inherent lack of taste and style; Emma garners praise that she knows she does not deserve without even trying.

“Harmony Before Matrimony,” by James Gillray, 1805 (Library of Congress)

“Matrimonal Harmonics,” by James Gillray, 1805 (Library of Congress)

In Jane Austen’s time, a young woman was expected to apply herself to the acquisition of accomplishments because they enhanced her chances that she would marry well. “Give a girl an education, and introduce her properly into the world,” says Mrs. Norris in Mansfield Park, “and ten to one but she has the means of settling well.” Beauty, accomplishments, and money were a surefire combination. In the same novel, Mrs. Grant expects that her sister, Mary Crawford, will marry well: “The eldest son of a Baronet was not too good for a girl of twenty thousand pounds, with all [her] elegance and accomplishments.” Emma Woodhouse, “handsome, clever, and rich,” can expect the same if she desires it.

Musical accomplishments were especially valued because a young woman, at home or visiting, could provide entertainment for her family and friends and display her charms at the same time. She might sing or play an instrument such as the harp, as Mary Crawford does in Mansfield Park, or the pianoforte, as Elizabeth Bennet does in Pride and Prejudice. Jane Austen sang and played the pianoforte herself, but only performed for family. She did enjoy listening to such performances, however: “Miss H. is an elegant, pleasing, pretty looking girl … with flowers in her head, & Music at her fingers ends.—She plays very well indeed. I have seldom heard anybody with more pleasure” (Letters, 29 May 1811). In Emma, both Miss Fairfax and Emma play the pianoforte and sing for their friends’ entertainment, much to Mr. Knightley’s enjoyment: “I do not know a more luxurious state, sir,” he tells Mr. Woodhouse, “than sitting at one’s ease to be entertained a whole evening by two such young women; sometimes with music and sometimes with conversation.”

In Emma, Jane Fairfax stands as the model for the truly accomplished young woman. Trained to be a governess, she has applied herself where Emma will not, and is, as Isabella Knightley calls her, “very accomplished and superior.” Emma has never made a friend of Jane Fairfax, and though she acknowledges her to be “one of the most lovely and accomplished young women in England,” in fact she is “sick of the very name of Jane Fairfax,” echoing Jane Austen’s own feelings about perfect heroines: “pictures of perfection as you know make me sick & wicked” (Letters, 23 March 1817). Emma does not admit to herself why she does not like this paragon of virtues, but Mr. Knightley knows it is “because she saw in her the really accomplished young woman, which she wanted to be thought herself.”

A detail from “Sweet Lullaby,” by Thomas Rowlandson, 1803 (Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University)

Harriet Smith, by contrast, is remarkably lacking in accomplishments. She is a goodhearted goose of a girl, but her education at Mrs. Goddard’s school in Highbury was simply inadequate, as Mr. Knightley tells Emma: “She is not a sensible girl, nor a girl of any information. She has been taught nothing useful, and is too young and too simple to have acquired any thing herself. … She is pretty, and she is good tempered, and that is all.” We hear of none of the usual accomplishments of young ladies; it appears that Harriet does not play the pianoforte well, does not sing or draw, and heaven knows she doesn’t read extensively. She has no doubt, though, been taught to sew and embroider nicely, creating the sort of “fancy work” that Mrs. Goddard has hanging in her parlor. Harriet provides Emma with a useful contrast—she is the unaccomplished friend who stands next to Emma to make her look good. In fact, her inferiority may fuel Emma’s self-complacency, Mr. Knightley warns Mrs. Weston: “Her ignorance is hourly flattery. How can Emma imagine she has any thing to learn herself, while Harriet is presenting such a delightful inferiority?”

In Augusta Elton, the Reverend Mr. Elton’s new bride, Jane Austen provides a representation of a sort of pseudo-accomplished woman. Mrs. Elton combines stunning vulgarity with a self-satisfied pretension that is based on nothing in particular. “Self‑important, presuming, familiar, ignorant, and ill‑bred,” with only “a little beauty and a little accomplishment,” Mrs. Elton has “so little judgment” that she thinks she is “coming with superior knowledge of the world, to enliven and improve a country neighbourhood.” Highbury society, to Emma’s chagrin, takes Mrs. Elton—the former Miss Hawkins—at face value: “A week had not passed since Miss Hawkins’s name was first mentioned in Highbury, before she was, by some means or other, discovered to have every recommendation of person and mind; to be handsome, elegant, highly accomplished, and perfectly amiable: and when Mr. Elton himself arrived to triumph in his happy prospects, and circulate the fame of her merits, there was very little more for him to do, than to tell her Christian name, and say whose music she principally played.”

“The Accomplish’d Maid,” by M. Darly, 1778 (Library of Congress)

Music, Mrs. Elton claims, is one of her chief “resources,” or accomplishments and personal qualities, that will enable her to endure the quiet village life of Highbury: “I absolutely cannot do without music. It is a necessary of life to me; and having always been used to a very musical society, both at Maple Grove and in Bath, it would have been a most serious sacrifice…. I honestly said that the world I could give up—parties, balls, plays—for I had no fear of retirement. Blessed with so many resources within myself, the world was not necessary to me. I could do very well without it. To those who had no resources it was a different thing; but my resources made me quite independent.” She never stays home long enough, though, for her resources to be tested: “From Monday next to Saturday, I assure you we have not a disengaged day!—A woman with fewer resources than I have, need not have been at a loss.” Yet in spite of being “doatingly fond of music—passionately fond,” Mrs. Elton, having married, seems to feel that the days of needing accomplishments for display are over: “For married women, you know,” she tells Emma, “there is a sad story against them, in general. They are but too apt to give up music.” She cites the example of her sister, three friends, and other women, “more than [she] can enumerate,” who have all given up playing music after marriage. Emma, “finding her so determined upon neglecting her music, had nothing more to say.”

With three such contrasts, it is no wonder that we appreciate Jane Austen’s depiction of Emma as an accomplished but nevertheless realistically flawed young woman, loved by Mr. Knightley as the “sweetest and best of all creatures, faultless in spite of all her faults.”

A final note: Among the many opinions of Emma collected by Jane Austen is that of Mrs. Cage, who wrote, “Miss Bates is incomparable, but I was nearly killed with those precious treasures!” For my part, I am nearly killed by Mrs. Elton’s resources. I treasure the little throwaway line when the Eltons’ horse is lamed and the party of pleasure must be postponed: “Mrs. Elton’s resources were inadequate to such an attack.”

Quotations are from the Oxford edition of The Novels of Jane Austen, edited by R.W. Chapman (1934) and from the fourth edition of Jane Austen’s Letters, edited by Deirdre Le Faye (Oxford, 2011). (The Library of Congress and the Lewis Walpole Library place no restrictions on the use of their out-of-copyright images.)

Twenty-fifth in a series of blog posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Emma. To read more about all the posts in the series, visit Emma in the Snow. Coming soon: the last post, entitled “Frank Churchill Gets a Haircut,” by Paul Savidge.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss the rest of this party for Emma! And/or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Pinterest, or Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley).

March 11, 2016

Emma the Imaginist

Deborah Yaffe is the author of Among the Janeites: A Journey Through the World of Jane Austen Fandom (2013). She’s an award-winning newspaper journalist and author and she’s been a passionate Jane Austen fan since first reading Pride and Prejudice at age ten. She has a bachelor’s degree in humanities from Yale University and a master’s degree in politics, philosophy, and economics from Oxford University, which she attended on a Marshall Scholarship. She works as a freelance writer and lives in central New Jersey with her husband, her two children, and her Jane Austen action figure.

Deborah Yaffe is the author of Among the Janeites: A Journey Through the World of Jane Austen Fandom (2013). She’s an award-winning newspaper journalist and author and she’s been a passionate Jane Austen fan since first reading Pride and Prejudice at age ten. She has a bachelor’s degree in humanities from Yale University and a master’s degree in politics, philosophy, and economics from Oxford University, which she attended on a Marshall Scholarship. She works as a freelance writer and lives in central New Jersey with her husband, her two children, and her Jane Austen action figure.

Deborah writes about Austen on her blog, and a couple of years ago I interviewed her about her blog series “The Watsons in Winter.” When I hosted a celebration in honour of Mansfield Park, she wrote a guest post called “The Fatal Mistake.”

For Emma in the Snow, she asked her daughter, Rachel Yaffe-Bellany, to take this photo of snow in New Jersey after last week’s snowfall. I’m delighted to introduce Deborah’s guest post on “Emma the Imaginist.”

Deborah says this is “The Last Gasp of Winter (or so we hope, at least).” (I’m hoping the snow that’s falling this morning is the last gasp of winter in Nova Scotia as well.)

Such an adventure as this,—a fine young man and a lovely young woman thrown together in such a way, could hardly fail of suggesting certain ideas to the coldest heart and the steadiest brain. So Emma thought, at least. Could a linguist, could a grammarian, could even a mathematician have seen what she did, have witnessed their appearance together, and heard their history of it, without feeling that circumstances had been at work to make them peculiarly interesting to each other?—How much more must an imaginist, like herself, be on fire with speculation and foresight!—especially with such a ground-work of anticipation as her mind had already made.

(Volume 3, Chapter 3, from the Norton Critical Edition of Emma, edited by George Justice [2012])

From David Copperfield and Jo March to T.S. Garp and Harriet the Spy, fiction is filled with writer-characters, semi-autobiographical outgrowths of their creators’ self-perceptions. At first blush, however, Jane Austen doesn’t seem to fit this pattern: Patricia Rozema’s 1999 film of Mansfield Park may transform Fanny Price into a stand-in for the scribbling young Austen, exhorting her younger sister, “Run mad as often as you chuse, but do not faint!” but Austen herself created no writer-characters.

Except, perhaps, for Emma Woodhouse.

Emma is in love with narrative. In the novel’s very first scene, we find her telling her anxious father a comforting bedtime story about their future visits to Randalls—down to the stabling for the horses and the reactions of coachman James. Most of the stories Emma tells, however, are of a different, very specific kind: they are courtship stories, whether about the Westons’ marriage and her own (possibly exaggerated) role in furthering it, or about Jane Fairfax’s illicit Dixon romance, or, as in the passage above, about Frank and Harriet’s future together. Inside her own head, Emma is a would-be Jane Austen, obsessed with the marriage plot. So strong is her narrative impulse that she experiences people she doesn’t yet know as mental creations of her own—“according to my idea of Mrs. Churchill … ” (Volume 1, Chapter 14); “My idea of [Frank] is … ” (Volume 1, Chapter 18)—and flattens those she does know into recognizable dramatic types (“a fine young man and a lovely young woman”).

More dangerously, of course, Emma moves from narration to creation—from telling stories about others’ lives to attempting to mold reality into the narrative shape she has chosen. And the deeper she gets into this effort—re-forming the malleable Harriet into a more polished version of ladyhood, scotching Robert Martin’s proposal, promoting the match with Mr. Elton—the harder it becomes for her to experience these people as separate beings with their own inner lives, rather than as the characters she has created. “Mr. Elton was proving himself, in many respects, the very reverse of what she had meant and believed him,” Emma thinks in mortified vexation, as if her own beliefs and intentions about his personality should somehow have compelled his conformity. She reassures herself with the “great consolation … that Harriet’s nature should not be of that superior sort in which the feelings are most acute and retentive”—and then is startled to find that, in fact, it takes months for Harriet to recover from her heartbreak (Volume 1, Chapter 16). She is even surprised to discover that Harriet’s rejection has wounded the Martins—so surprised that she must quickly tell herself a new, self-exculpatory story about their motivations (“Ambition, as well as love, had probably been mortified” [Volume 2, Chapter 3]).

In fact, although Emma thinks of herself as “an imaginist,” her imaginative repertoire is fatally impoverished, for she is unable to imagine the feelings of other people. Like her father, who assumes that everyone must feel as he does, and therefore prefer gruel and quiet to cake and company, Emma makes herself the measure of all things. The humbling journey on which Jane Austen takes her is an education not only in her own feelings for Mr. Knightley but also in the irreducibly separate reality of other people’s experience, and the respect that this irreducible separateness demands. Essentially, this is what Mr. Knightley calls to her attention in the scolding he administers after the Box Hill picnic: Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich, must think herself into the life of a woman who is none of those things, and behave accordingly. Only in the final chapters of the novel, when Emma schools herself to endure suffering out of “a strong sense of justice by Harriet” (Volume 3, Chapter 11) and an unselfish desire to help Mr. Knightley (“Emma could not bear to give him pain” [Volume 3, Chapter 13]) does she fully imagine the feelings of others and resolve to put them ahead of her own.

Along the way, Emma—and by extension, we, the readers—also get a quiet education in storytelling. For Emma, the drama of courtship grows, ideally, out of melodrama: she is captivated by Jane Fairfax’s rescue from near-drowning and Harriet’s disturbing encounter with the gypsies. Even for the Westons’ uneventful middle-aged romance, Emma proposes a semi-dramatic starting-point: the protagonists’ chance encounter during a convenient rainstorm. No wonder she assumes Harriet must have fallen for the man who rescued her from the gypsies. Such an adventure! So peculiarly interesting! It turns out, however, that for Harriet, the adventure lies somewhere else entirely—in the “much more precious circumstance” (Volume 3, Chapter 11) of dancing with Mr. Knightley after the Eltons’ snub. True drama, Emma learns from Harriet, lies not in the extraordinary but in the everyday. And, of course, this is the great truth that all Austen’s work teaches us, and that is lost on critics who berate her for leaving out the Corn Laws and the Napoleonic Wars: the small tragedies and accomplishments of private life matter as much as the great dramas of war and politics. Emma, the would-be courtship novelist, must learn to appreciate the dramatic substance of her own unremarkable life.

But if Emma is Austen’s only writer-character, she is a strange version of the type, for she never writes a line. Her stories remain locked inside her imaginist’s mind, or, at most, imperfectly realized in the world around her. She is less a writer than a writer manqué, her creative impulses left unexpressed, thwarted by her own limitations and by the messiness of real life. Will the adventure of marriage and child-rearing provide the creative outlet she needs—an outlet that, we Austen readers cannot help noticing, Emma’s creator found wholly inadequate for her own creative impulses? In the final line of the novel, Austen assures us of Emma’s future “perfect happiness” (Volume 3, Chapter 19), but it’s hard not to imagine a very different outcome.

Twenty-fourth in a series of blog posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Emma. To read more about all the posts in the series, visit Emma in the Snow. Coming soon: guest posts by Kim Wilson and Paul Savidge.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the celebrations! And/or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook , Pinterest , or Twitter ( @Sarah_Emsley ).

March 9, 2016

My Heart Belongs to Mr. Knightley

Sarah Woodberry is a writer, editor, and creative writing instructor who loves to reread Jane Austen. She’s a member of JASNA’s New York Metropolitan Region and she teaches at Norwalk Community College in Connecticut. She says while she subscribes to the theory that “whichever Austen novel one is reading is the favorite,” she has a soft spot for Emma: “Every time I read the final line, I want to flip back to page one and start Emma again.” She first read the novel as a teenager and she’s reread it many times since then because she finds it “the sunniest and happiest” of Austen’s novels. It’s the book she turns to—and recommends to friends—“in tough or stressful times.”

Sarah Woodberry is a writer, editor, and creative writing instructor who loves to reread Jane Austen. She’s a member of JASNA’s New York Metropolitan Region and she teaches at Norwalk Community College in Connecticut. She says while she subscribes to the theory that “whichever Austen novel one is reading is the favorite,” she has a soft spot for Emma: “Every time I read the final line, I want to flip back to page one and start Emma again.” She first read the novel as a teenager and she’s reread it many times since then because she finds it “the sunniest and happiest” of Austen’s novels. It’s the book she turns to—and recommends to friends—“in tough or stressful times.”

Sarah wrote a guest post called “Worn Out with Civility at Mansfield Park” for my Mansfield Park series, and she wrote about Mr. Knightley in today’s guest post for Emma in the Snow. She blogs about reading and writing at Word Hits and you can find her on Twitter as well: @WordHits. It’s a pleasure to introduce her post on why Mr. Knightley is her favourite Austen hero.

Sarah’s photo of snowdrops in the snow

I don’t have an “I Heart Darcy” t-shirt. To be sure, when reading Pride and Prejudice, one cannot help but be enamored of Mr. Darcy. But really, when it comes to Jane Austen’s heroes, my heart belongs to Mr. George Knightley. He has all the advantages of Darcy—land, position, looks—but “with a real liberality of mind” (Volume 1, Chapter 18).

Despite his status as the most prominent landowner around, Mr. Knightley is not a snob. He has “a delicacy towards the feelings of other people” (Volume 1, Chapter 18). He shows attention to those less fortunate, like the Bateses and the orphaned Jane Fairfax. He’s happy to visit the “only moderately genteel” Coles (Volume 2, Chapter 7). When Harriet Smith is snubbed so publicly by Mr. Elton at the ball, Mr. Knightley makes a point of leading her onto the floor. Emma calls him “benevolent” (Volume 2, Chapter 8), and Harriet notices his “noble benevolence” (Volume 3, Chapter 11).