Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 25

March 2, 2016

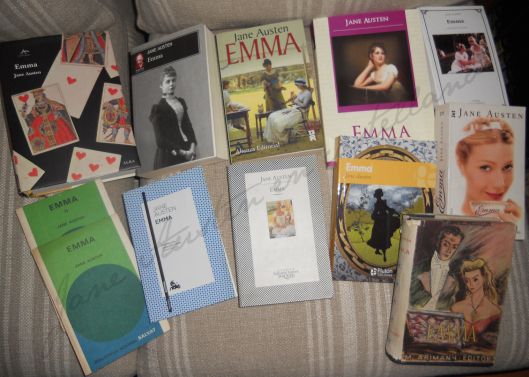

Jane Austen and her Emma in Spanish

Cinthia Garcia Soria is a freelance translator (from English to Spanish) and she’s working towards a Master’s degree in Applied Linguistics in Translation Studies at

the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México

. Her research focuses on the translation of irony in three novels by Jane Austen. She’s a long-time Janeite and in 1999 she co-founded JAcastellano

, a Jane Austen group for Spanish speakers. Here’s the link to the Yahoo Group. JAcastellano is also on Facebook and Twitter (@JAcastellano).

Cinthia Garcia Soria is a freelance translator (from English to Spanish) and she’s working towards a Master’s degree in Applied Linguistics in Translation Studies at

the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México

. Her research focuses on the translation of irony in three novels by Jane Austen. She’s a long-time Janeite and in 1999 she co-founded JAcastellano

, a Jane Austen group for Spanish speakers. Here’s the link to the Yahoo Group. JAcastellano is also on Facebook and Twitter (@JAcastellano).

Last month, Gillian Dow talked about the first French translation of Emma in her guest post for Emma in the Snow; today I’m pleased to introduce Cinthia’s guest post on Spanish translations of Austen’s novels, particularly of Emma.

She’s also sent a photo of two snow-covered volcanoes near Mexico City, where she lives. Here’s her description of them: “ The one in the left is the Iztaccihuatl (Nahuatl, from ‘White Woman,’ also called the ‘Sleeping Woman’ because of the shape it has, and because it’s considered a dormant volcano). On the right side is Popocatepetl (also Nahuatl, from ‘Smoking Mountain,’ and yes, it is an active volcano). The legend is that Iztaccihuatl was an Aztec princess who fell in love with one of her father’s warriors, Popocatepetl, and he was sent to war with the promise that on his return he could marry her. She was told he had fallen in battle, and the news caused her to die of grief. It was a lie—when he returned and found out he took her to the valley and stood beside her watching in eternity over her. The gods turned them into ‘mountains.’”

Jane Austen was almost unknown for most of the twentieth century in my part of the world. Those of us who discovered her before the big boom of adaptations in the mid-1990’s certainly struggled to find copies of her works in our language and only a few of us were adventurous enough to read her in English.

It was a little more than a century after Austen’s death that three of her novels were first translated into Spanish: Persuasion in 1919, followed by Northanger Abbey in 1921 and then Pride and Prejudice in 1924, issued by Calpe—later known as Espasa-Calpe. Twenty years later, in the wake of the interest created by the 1940 Pride and Prejudice film, more editions of that novel appeared and also the other three novels were at last translated into Spanish: Sense and Sensibility (which has been given at least five different titles in Spanish) in 1942, Mansfield Park in 1943 (with Chapters 11 through 20 omitted in that first translation), and Emma in 1945 (translated by Jaime Bofill y Ferro, in an edition published by M. Arimany). Yet for most of the 20th century, Jane Austen was almost unknown in the Spanish-speaking world, because only editions of the first three translated novels remained available.

It was a little more than a century after Austen’s death that three of her novels were first translated into Spanish: Persuasion in 1919, followed by Northanger Abbey in 1921 and then Pride and Prejudice in 1924, issued by Calpe—later known as Espasa-Calpe. Twenty years later, in the wake of the interest created by the 1940 Pride and Prejudice film, more editions of that novel appeared and also the other three novels were at last translated into Spanish: Sense and Sensibility (which has been given at least five different titles in Spanish) in 1942, Mansfield Park in 1943 (with Chapters 11 through 20 omitted in that first translation), and Emma in 1945 (translated by Jaime Bofill y Ferro, in an edition published by M. Arimany). Yet for most of the 20th century, Jane Austen was almost unknown in the Spanish-speaking world, because only editions of the first three translated novels remained available.

Things changed in those last five years of the past century, as they did almost everywhere else, and since then, we have tried to catch up. Of course Pride and Prejudice has remained popular. But the other novels became available again by the end of the last century, and even some of minor works were also at last translated. Then, in 2012, all the letters were translated. This edition of the Cartas (Letters) of Jane Austen, published by D’Época Editorial, is a real highlight, because no other Spanish translation of Austen’s writing has reached its level of quality.

Things changed in those last five years of the past century, as they did almost everywhere else, and since then, we have tried to catch up. Of course Pride and Prejudice has remained popular. But the other novels became available again by the end of the last century, and even some of minor works were also at last translated. Then, in 2012, all the letters were translated. This edition of the Cartas (Letters) of Jane Austen, published by D’Época Editorial, is a real highlight, because no other Spanish translation of Austen’s writing has reached its level of quality.

Although there are still Spanish-speaking countries and places where it isn’t possible to find translations of Austen’s novels, the number of editions in Spanish can easily reach two hundred. (Over 50% of these are translations of Pride and Prejudice.) Frankly, the problem Spanish-speaking Janeites face now is not the quantity but the quality of the translations and editions (and I admit we can be very fastidious readers).

Although the original English text of the works of Jane Austen has long been in the public domain, some people think, mistakenly, that Spanish translations are also free of copyright, but that is not so, since not even a century has passed since most of the translations were first published.

In addition, a single translation can be used for different editions, printed either by the same publishing house, or by a different publishing house. Sometimes the translator is not identified, and only when you compare texts can you discover who it was. There are translations credited to different individuals—yet some of these do seem to have been based on previous translations instead of the source text. Some translations are still credited to the first translator, even though someone else has since modernized the text (and such modernizations don’t always improve the translation). Some apparently new translations are identical—character by character and dot by dot—to a previous one. Or the syntax has been rearranged in order to conceal that the translation is based on a previous one. The number of translations is thus significantly lower in comparison with the number of editions.

It is difficult to answer which is the best translation as many factors are involved. There is no perfect translation of any author or any work. Inevitably, something is lost in translation, and even the most accomplished translator slips once in a while. To this we can add that Jane Austen is not easy to translate, partly because of her wit and irony, but also because of the differences between cultures and the 200-year gap between her time and our own.

For some of us, the many reference books published in English about Jane Austen’s life and times help to provide some context for her writing, but unfortunately none of them has been translated into Spanish. Introductions to the novels might help, but not many editions include one, and sometimes only a brief general biographical notice of the author is included. In the case of Emma, at least three of its translators have written introductions to the novel, but, unfortunately, two of these include big plot spoilers.

If Jane Austen’s contemporary readers—Maria Edgeworth included—found it difficult to understand Emma, it is not surprising people abroad nowadays may similarly dislike the novel because they think nothing happens in it. No aid is provided for readers to understand what is going on below the surface in the many editions and translations of the novel.

I could enter into details about other problems that could be found in the translations into Spanish, but for now I’ll just say that up to now it appears there are at least eleven translators of Emma into Spanish; however, only around six of them seem to have worked from the original text, some more successfully than others. Their translations continue to be in use, in some cases forty years (or more) after they first appeared in print.

One element of modern translations I dislike is the trend towards translations adapted for the reader’s environment, instead of translations that help readers to understand the world depicted in the original text. For example, English units are sometimes changed to their equivalents in the decimal measurement system, which is, I think, a controversial decision. It does not augur well for future translations or editions.

I wonder if something similar has happened in the translation of Jane Austen’s works into other languages.

For further reading:

Chryssofós, Iris (junio, 2014). Las traducciones argentinas de un par de novelas de Jane Austen: Northanger Abbey y Lady Susan. Paper presented at Jornadas internas en honor a Jane Austen de la Universidad Nacional de La Plata (UNLP). Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Crespo Allúe, María José (1981), La problemática de las versiones españolas de Persuasión de Jane Austen. Crítica de su traducción (doctoral thesis). Valladolid: Universidad de Valladolid.

Díaz Bild, Aída (2007). “Still the Great Forgotten? The Reception of Jane Austen in Spain” in Mandal, Anthony y Southam, Brian (eds.) (2007). The Reception of Jane Austen in Europe. London: Continuum; p. 188-204.

Dow, Gillian (2013). “Translations” in Sabor, Peter (ed.) (2015). The Cambridge Companion to Emma. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 166-187.

García Soria, Cinthia (2013). ¿Lost in translation? La traducción de la obra de Jane Austen en el mundo de lengua española. Paper presented at Coloquio Interdisciplinario Jane Austen: Orgullos y Prejuicios en la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). Mexico City, Mexico.

Mandal, Anthony (2009). “Austen’s European Reception” in Johnson, Claudia L. and Tuite, Clara (eds.) (2009). A Companion to Jane Austen. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, UK, p. 422-433.

Smith, Ellen (1985). “Spanish Translations of Northanger Abbey” in Persuasions 7, Journal of the Jane Austen Society of North America, p. 21-27. http://www.jasna.org/persuasions/printed/number7/smith.html

Wright, Andrew y Alazraki, Jaime (1975). “Jane Austen Abroad – Mexico” in Halperin, John (ed.) (1975) Jane Austen Bicentenary essays. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 304-306.

Twenty-first in a series of blog posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Emma. To read more about all the posts in the series, visit Emma in the Snow. Coming soon: guest posts by Carol Chernega, Sarah Woodberry, and Deborah Yaffe.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the celebrations! And/or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook , Pinterest , or Twitter ( @Sarah_Emsley ).

February 26, 2016

Miss Bates in Fairy-land

Margaret C. Sullivan is the author of Jane Austen Cover to Cover and The Jane Austen Handbook. She wrote about “The Manipulations of Henry and Mary Crawford” for the celebration I hosted in honour of Mansfield Park, and I’m delighted to introduce her guest post for Emma in the Snow.

Maggie is the Editrix of AustenBlog.com, where she has been, in her words, “holding forth on Jane Austen and popular culture since 2004.” She recently flew across the United States in the teeth of a blizzard to see Love & Friendship, the upcoming adaptation of Austen’s Lady Susan, at the Sundance Film Festival. She says she didn’t meet anyone famous at the Festival, “not even Faux Bradley Cooper,” but she saw “lots of stunning snow-covered mountains, which was way better.” Love & Friendship received the Official AustenBlog Seal of Approval. Maggie blogs at This Delightful Habit of Journaling as well as at AustenBlog. Here’s a photo from her trip to Utah.

I came to Jane Austen later in life than many, in my late 20s—that is, seven or eight years older than Miss Woodhouse. The first Austen I read was Emma. I was in a mall drugstore, looking for something to read, when a remaindered copy of Emma caught my eye, marked down to $2. People had been telling me for years that I should read Jane Austen, and the price was right, so I bought the book.

Somehow I had it in my mind that Austen had been living and writing in the early 20th century about an earlier time period. When I reached the scene where the guests were arriving for the Westons’ ball at the Crown, in particular Miss Bates’ arrival and her monologue that filled several pages of the paperback, I was so taken with the scene I suddenly wanted to know more about the author. I flipped to the little author mini-bio at the front of the book, and was astonished to learn that Austen had lived in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The humor and the brutally honest portrayal of the various characters felt very modern to me.

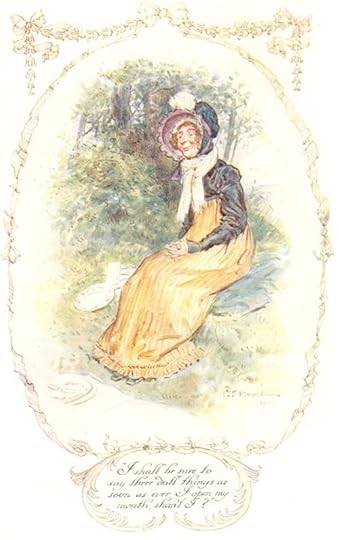

When Sarah asked me to participate in her “Emma in the Snow” event, that passage—Miss Bates’ monologue as she arrives at the ball—sprang to mind immediately, for lots of reasons. Because it was the first scene in Austen’s work that I remember absolutely loving as I read it; because it’s just darned funny; and maybe because I identify with Miss Bates a little bit, being a middle-aged spinster myself, and someone who, with the best of intentions, bores people at length about my odd interests like European royalty (and their tiaras … especially the tiaras) and tech devices and, oh yeah, Jane Austen. I suppose we’re all guilty, now and then, of saying “three things very dull indeed.”

“I shall be sure to say three dull things as soon as ever I open my mouth, shan’t I?” Illustration by C.E. Brock. (Source: Mollands.net)

But really there’s quite a lot going on in this short passage. On the surface it’s just hilarious, and the portrayal of Miss Bates as a garrulous middle-aged spinster is extremely fine, but there is more to it. Here is the passage, from Volume 3, Chapter 2 (Chapter 38), with apologies in advance for the length:

Miss Bates and Miss Fairfax, escorted by the two gentlemen, walked into the room; and Mrs. Elton seemed to think it as much her duty as Mrs. Weston’s to receive them. Her gestures and movements might be understood by any one who looked on like Emma, but her words, every body’s words, were soon lost under the incessant flow of Miss Bates, who came in talking, and had not finished her speech under many minutes after her being admitted into the circle at the fire. As the door opened she was heard,

“So very obliging of you!—No rain at all. Nothing to signify. I do not care for myself. Quite thick shoes. And Jane declares—Well!—(as soon as she was within the door) Well! This is brilliant indeed!—This is admirable!—Excellently contrived, upon my word. Nothing wanting. Could not have imagined it.—So well lighted up.—Jane, Jane, look—did you ever see any thing? Oh! Mr. Weston, you must really have had Aladdin’s lamp. Good Mrs. Stokes would not know her own room again. I saw her as I came in; she was standing in the entrance. ‘Oh! Mrs. Stokes,’ said I—but I had not time for more.”—She was now met by Mrs. Weston.—“Very well, I thank you ma’am. I hope you are quite well. Very happy to hear it. So afraid you might have a headache!—seeing you pass by so often, and knowing how much trouble you must have. Delighted to hear it indeed. Ah! dear Mrs. Elton, so obliged to you for the carriage!—excellent time.—Jane and I quite ready. Did not keep the horses a moment. Most comfortable carriage.—Oh! and I am sure our thanks are due to you, Mrs. Weston, on that score.—Mrs. Elton had most kindly sent Jane a note, or we should have been.—But two such offers in one day!—Never were such neighbours. I said to my mother, ‘Upon my word, ma’am⸺,’ Thank you, my mother is remarkably well. Gone to Mr. Woodhouse’s. I made her take her shawl—for the evenings are not warm—her large new shawl—Mrs. Dixon’s wedding-present.—So kind of her to think of my mother! Bought at Weymouth, you know—Mr. Dixon’s choice. There were three others, Jane says, which they hesitated about some time. Colonel Campbell rather preferred an olive. My dear Jane, are you sure you did not wet your feet?—It was but a drop or two, but I am so afraid:—but Mr. Frank Churchill was so extremely—and there was a mat to step upon—I shall never forget his extreme politeness.—Oh! Mr. Frank Churchill, I must tell you my mother’s spectacles have never been in fault since; the rivet never came out again. My mother often talks of your good-nature. Does not she, Jane?—Do not we often talk of Mr. Frank Churchill?—Ah! here’s Miss Woodhouse.—Dear Miss Woodhouse, how do you do?—Very well I thank you, quite well. This is meeting quite in fairy-land!—Such a transformation!—Must not compliment, I know (eyeing Emma most complacently)—that would be rude—but upon my word, Miss Woodhouse, you do look—how do you like Jane’s hair?—You are a judge.—She did it all herself. Quite wonderful how she does her hair!—No hairdresser from London I think could.—Ah! Dr. Hughes I declare—and Mrs. Hughes. Must go and speak to Dr. and Mrs. Hughes for a moment.—How do you do? How do you do?—Very well, I thank you. This is delightful, is not it?—Where’s dear Mr. Richard?—Oh! there he is. Don’t disturb him. Much better employed talking to the young ladies. How do you do, Mr. Richard?—I saw you the other day as you rode through the town—Mrs. Otway, I protest!—and good Mr. Otway, and Miss Otway and Miss Caroline.—Such a host of friends!—and Mr. George and Mr. Arthur!—How do you do? How do you all do?—Quite well, I am much obliged to you. Never better.—Don’t I hear another carriage?—Who can this be?—very likely the worthy Coles.—Upon my word, this is charming to be standing about among such friends!—And such a noble fire!—I am quite roasted. No coffee, I thank you, for me—never take coffee.—A little tea if you please, sir, by and bye,—no hurry—Oh! here it comes. Every thing so good!”

(This passage is a lot of fun to read aloud. I once did so for a book group to which I used to belong, with many dramatic flourishes. I hope they enjoyed it as much as I did. I was gasping for air at the end, too!)

Throughout the book, it feels like we’re supposed to feel sorry for Miss Bates. Mr. Knightley certainly means Emma to feel sorry for her—or at least feel compassion for her. However, here she is at a ball, not stuck at Hartfield with Mr. Woodhouse and her mother and unable to enjoy the yummy treats. Miss Bates has come to the ball to enjoy herself, and the enjoying starts the second she walks in. Frank Churchill has already expressed that sentiment: “though he did not say much, his eyes declared that he meant to have a delightful evening.” Miss Bates does not need her eyes to do any declaring; her mouth is more than up to the job.

She passes through the room and speaks to several friends: first Mrs. Stokes, “standing in the entrance”; Mrs. Weston, Mrs. Elton, Frank Churchill, Emma herself, Dr. and Mrs. Hughes, Mr. and Mrs. Otway, their (presumably) two daughters and two sons, the Coles are heard coming in and no doubt will be greeted in their turn, and Mr. Richard Hughes even leaves the young ladies to come over and pay his compliments. Such a host of friends! Such a noble fire! Tea, almost the instant she asks for it, though she was in no hurry for it! No wonder she exclaims, “This is delightful, is not it?” and “Every thing so good!”

There is so much consideration for her comfort. Mrs. Weston sent a note, offering to have their carriage pick up Miss Bates and Jane Fairfax; Emma and Harriet stopped to offer them a ride; the Eltons forgot them at first, but the carriage is immediately sent for them. Frank Churchill knows Miss Bates (and her charge) should not be forgotten, and waits with an umbrella. Her friends gather around her, and tea is brought. Ladies’ gowns and hair are admired with true enjoyment. She is very well, she assures each friend who asks how she does; quite well; never better.

Miss Bates is determined to have a good time, and determined to not let her circumstances get her down, and we can all learn from that. At middle age, life has passed her by. Did she ever have a lover, one wonders? Perhaps someone like Robert Martin, a yeoman farmer, not considered eligible for the vicar’s daughter (and, one notes, not invited to the ball, nor are his sisters, apparently), but who could perhaps have given the former Hetty Bates a comfortable home at least, and her mother and niece as well? A home where she might not be obliged to depend upon gifts of a hind-quarter of pork or a bushel of apples from neighbors, or even rides in their carriages? That is likely a subject that Jane Austen had meditated upon, having passed up such a home offered by Harris Bigg-Wither.

But Mr. Bigg-Wither was certainly of a social standing to be invited to balls given by his neighbors. Miss Bates may have had to give that up, if she “married down,” as Harriet Smith will have had to give up being visited by Miss Woodhouse (though perhaps not by Mrs. Knightley, not completely) when she marries Robert Martin. I wonder which of those choices Miss Bates would pick with the benefit of hindsight. No matter what it was, she would have made the best of it, and maybe that’s the message we’re supposed to take away from this.

Carpe diem, says Miss Bates. Live in the moment, and you will be quite well; never better. Even a middle-aged spinster can enjoy herself at a ball, writes (almost) middle-aged spinster Jane Austen. In 1813, not long before she started writing Emma, Austen wrote in a letter to her sister, “By the bye, as I must leave off being young, I find many Douceurs in being a sort of Chaperon for I am put on the Sofa near the Fire & can drink as much wine as I like” (6 November 1813). Or tea, one presumes.

I’m thrilled for Miss Bates and her enjoyment at the ball. Her arrival and conversation provide fun for the reader, but Jane Austen’s characters come so vividly to life that one cannot help but sometimes think of them as real people, and wonder about their inner lives. This scene is hilarious, but it also provides a different kind of enjoyment: that of knowing that Hetty Bates had at least one night in fairy-land. Don’t we all deserve that?

Quotations are from the Penguin edition of Emma, edited and with an introduction by Juliette Wells (2015), and the Oxford edition of Jane Austen’s Letters, edited by Deirdre Le Faye (4th edition, 2011).

Twentieth in a series of blog posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Emma. To read more about all the posts in the series, visit Emma in the Snow. Coming soon: guest posts by Cinthia Garcia Soria, Carol Chernega, and Sarah Woodberry.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the celebrations! And/or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Pinterest, or Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley).

February 24, 2016

Why do readers object to the romance between Emma and Mr. Knightley?

Kirk Companion is a member of two Jane Austen book clubs in the Boston area, and for one of them, “Austen in Boston,” he also serves as one of the main organizers. The group has met in a variety of places, including Salem, Massachusetts—to discuss Northanger Abbey—and Georges Island in Boston Harbor. They sometimes read books by other writers, including Elizabeth Gaskell and, Kirk says, “Edith ‘I never met an unhappy ending I didn’t like’ Wharton.” I’m happy to introduce his guest post on the romance between Emma and Mr. Knightley. Welcome to Emma in the Snow, Kirk, and thank you to you and the members of Austen in Boston for sharing these beautiful photos with us. (Here’s the Facebook page for the group. You can also find them on Twitter: @AusteninBoston.)

Kirk often goes to JASNA Massachusetts meetings and sometimes travels further to attend JASNA Vermont events. In contrast to Austen in Boston, which holds meetings in public spaces, the other Jane Austen book club he belongs to tends to meet in members’ homes. Kirk tells me he has fond memories of visiting Box Hill on a trip to England a few years ago—he says that “even without the Austen connection it truly is lovely”—and he regrets that he has only a few photos from the trip. Here’s one of them.

He also sent me a recent photo of Boston in the snow.

And he sent a photo from an Austen in Boston meeting at Larz Anderson Park in Brookline, where the group talked about Gaskell’s North and South.

Photo by Rebecca Price

These last two photos are from an Austen in Boston picnic at World’s End, Hingham, which featured a discussion of Wharton’s novel The Age of Innocence.

Photo by Shirley Goh

Photo by Shirley Goh

And here’s Kirk’s contribution to the conversations about Emma and Mr. Knightley.

She was more disturbed by Mr. Knightley’s not dancing, than by any thing else.—There he was, among the standers-by, where he ought not to be; he ought to be dancing…. —so young as he looked!—He could not have appeared to greater advantage perhaps any where, than where he had placed himself…. His tall, firm, upright figure among the bulky forms and stooping shoulders of the elderly men, was such as Emma felt must draw every body’s eyes…. He moved a few steps nearer, and those few steps were enough to prove in how gentlemanlike a manner, with what natural grace, he must have danced, would he but take the trouble.

…

“Whom are you going to dance with?” asked Mr. Knightley.

She hesitated a moment, and then replied, “With you, if you will ask me.”

“Will you?” said he, offering his hand.

“Indeed I will. You have shown that you can dance, and you know we are not really so much brother and sister as to make it at all improper.”

“Brother and sister! no, indeed.”

(Chapter 38, from the Anchor Books edition of Emma, edited and annotated by David M. Shapard [2012])

Mr. Knightley is my favorite Austen hero. I wish I were more like him, so well able to tolerate the Mr. Woodhouses and Miss Bateses of the world. (Sadly, I’m more like his grumpy brother Mr. John Knightley—but enough about me). So, it was surprising to me to that several members of one of my two Austen bookclubs can’t stand the Emma/Mr. Knightley relationship. One person fixated on the fact that Mr. Knightley—being about 16 years older than Emma—has known her since she was an infant. Also, he’s acted as a mentor or surrogate relative throughout Emma’s formative years, especially since Emma hasn’t had a true active parent, given that Mr. Woodhouse has been too concerned with his own health, or guardian, given that Miss Taylor has always been too easy on her.

I was very curious about what others thought about the relationship between Emma and Mr. Knightley, so I discussed it at two different JASNA meetings and two different bookclubs. I had thought the reaction to them towards them was overwhelmingly positive. However, I was very surprised to find that it wasn’t. Some of the responses I heard: “I haven’t really thought about the prior relationship between Emma and Mr. Knightley”; “I don’t care about that”; and “I haven’t thought about it, but yeah … not thrilled by that.” In a group of five Janeites, the vote was 2½ for the romantic relationship between Emma and Mr Knightley and 2½ against, with one person arguing both in favour of and against the romance.

I’d be interested to know what all of you think of the romance. Does it bother you that Mr. Knightley is so much older than Emma? Do you think their marriage will be a happy one?

Nineteenth in a series of blog posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Emma. To read more about all the posts in the series, visit Emma in the Snow. Coming soon: guest posts by Margaret C. Sullivan, Cinthia Garcia Soria, and Carol Chernega.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the celebrations! And/or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook , Pinterest , or Twitter ( @Sarah_Emsley ).

February 19, 2016

Highbury Heights; or, George and Emma Knightley, Suburban Developers

Kate Scarth considered becoming an urban planner, but eventually decided to combine her love of literature with her interest in cities and geography by doing a PhD at the University of Warwick on “how Romantic-period novels (including Austen’s), deal with London’s growing suburbs.” She’s currently developing this project into a book and she’s made the case for Jane Austen and Charlotte Smith as suburban writers. She’s also written about L.M. Montgomery, and her article “Anne of the Suburbs” (which analyzes the depiction of “Patty’s Place” in “Kingsport”/Halifax in Anne of the Island) will be published in Women’s Writing.

Kate is a SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellow in English here in Halifax at Dalhousie University. She says her postdoc project “builds on geo-lit interests and focuses on London’s green geographies in the Romantic period.” At the moment she’s spending some time in St. John’s, Newfoundland, so she sent me a few photos of St. John’s in the snow. Here’s her guest post for Emma in the Snow, on Highbury as a suburb. Thanks, Kate!

A suburb in the snow

Are Emma Woodhouse, Mrs. Elton, Isabella Knightley, Isabella Thorpe, Maria Crawford, and Maria Bertram Rushworth original “desperate housewives”? All of these Jane Austen characters either live in or have something to say about the well-heeled Regency suburbs, forerunners of the affluent suburbia of lavish homes and manicured lawns inhabited by the women of TV’s Desperate Housewives (2004-12). Desperate Housewives’ landscape embodies both reality (a detached or semi-detached home surrounded by a lawn is the standard middle-class British and North American residence) and aspiration, given the size and opulence of the show’s homes. Desperate Housewives’ setting is also the kind of space that often comes under fire: the suburbs can represent sprawl, vulgarity, conformity, and cultural vacuousness. The affluent suburban landscape and the twin impulses of aspiration and satire were also at play in Emma’s England.

Jane Austen had something to say about the suburbs, as she did about many other things in the world around her. References to Greater London abound. Isabella Thorpe reveals her true social climbing stripes when, pretending to want a retired, rural cottage, she is in fact imagining a villa in Richmond, a suburb considered fashionable enough for the grand Mrs. Churchill’s convalescence. Admiral Crawford extensively landscapes the grounds of his Twickenham cottage, and while Henry is staying there and Maria Rushworth is in nearby Richmond, they start their illicit affair. Isabella Knightley insists to her father, Mr. Woodhouse, that the air of Brunswick Square, Bloomsbury is salubrious, unlike the rest of polluted London, and it therefore meets their exacting parental and medical standards. And, of course, Maple Grove (near Bristol) is home to Mrs. Elton’s Suckling relatives and their barouche-landau. Austen shows that the Regency suburbs were bound up with sex and marriage, money and class, love and children, luxury and consumerism, home renovations and landscaping, all suitable fodder for a Desperate Housewives episode.

Kate says she chose this photo because Regency suburbs were so dependent on horses.

Highbury is Austen’s most sustained look at a suburb. Sixteen miles from London, Highbury is firmly within Greater London (as early as the 1720s, Epsom, fifteen miles from London and also in Surrey, was suburbanizing as a commuter town for City merchants, as Chris Miele points out). Thomas Hothem and Tara Ghoshal Wallace have both discussed the many ways Highbury is suburban (or is what I am calling “Highbury Heights”). Like Epsom, Highbury is also a commuter town. For “eighteen or twenty years,” Mr. Weston had divided his time and space in a suburban way: “useful occupation” is spent in the City, while “leisure” and “the pleasures of society” are found in his “small house in Highbury.” At the novel’s start, Mr. Weston and his fellow merchant Mr. Cole have only semi-retired to Highbury and are still involved in London business. Mr. Weston continues to commute to London (at least occasionally). In his retirement, Mr. Weston can afford a “little estate adjoining to Highbury, which he had always longed for,” thus realizing the suburban dream of house plus land (Volume 1, Chapter 2). Highbury is also a suburban bedroom community dependent on London’s goods and services. Highburians purchase a piano and order ribbons and a folding-screen from the city; they also visit a hairdresser, law firm, dentist, picture framer, and Aspley’s circus.

While landlords of London-adjacent land (such as the Russells in Bloomsbury) were the Regency-era land developers in the conventional sense, Mr. Knightley and Emma are developers of suburban space in a cultural sense. By controlling social relations in Highbury, Mr. Knightley and Emma manage the transformation of the village into a suburb in a way that keeps them on top of its social hierarchy but that flexibly accommodates new, urban, middle-class elements. In other words, they set the cultural tone for the new suburban version of Highbury.

A Newfoundland regiment memorial that commemorates the battle of Beaumont Hamel, where many Newfoundlanders died in 1916.

The Westons’ Christmas Eve dinner party, also discussed in this series by Nora Bartlett, is a good (snowy) example of Mr. Knightley and Emma’s management. While Mr. Weston, the host, acts with “the utmost good-will,” he fails to control this space (Volume 1, Chapter 15). When snow threatens to strand everyone, he does not relieve Mr. Woodhouse’s or Isabella’s anxiety and causes Mrs. Weston uneasiness by calling her “to agree with him, that, with a little contrivance, every body might be lodged, which she hardly knew how to do, from the consciousness of there being but two spare rooms in the house.” Mr. Knightley takes charge: he goes outside to inspect the roads and is able to reassure everyone that reports of snow have been greatly exaggerated. He is soon joined by Emma in managing this space and getting everyone home safely: “while the others were variously urging and recommending, Mr. Knightley and Emma settled it in a few brief sentences.” Meanwhile, Mr. and Mrs. Weston are the supporting managers. Earlier, Mrs. Weston and Emma had “tried earnestly to cheer [Mr. Woodhouse],” and later “the carriages came: and Mr. Woodhouse, always the first object on such occasions, was carefully attended to his own by Mr. Knightley and Mr. Weston.” Mr. Weston brings his good humour (and money) to Highbury, enriching the village socially and economically, but when his gregarious personality causes discomfort, he follows Mr. Knightley’s lead and attends to Mr. Woodhouse, who because of age, gender, and rank, is second in Highbury’s hierarchy. Ultimately then, Mr. Weston is not shaking up Highbury’s social hierarchies or ways of doing things.

When Mr. Knightley moves to the Woodhouses’ home, Hartfield, he and Emma (now the Knightleys) get their own suburban space to manage. Hartfield is surrounded by a “lawn and shrubberies” (Volume 1, Chapter 1), and like the newly arrived Highbury suburbanites, the Woodhouses’ money probably has urban ties. As an unlanded gentry family, their “fortune from other sources” (i.e., not the land, and thus rural, sources of wealth), likely comes from investments or government bonds held in London’s financial City (Volume 1, Chapter 16). Mr. Knightley and Emma already have a solid track record as Hartfield managers. Emma single-handedly runs Hartfield (and quite well since even the exacting Mr. Knightley compliments her hostessing skills), and he often takes Mr. Woodhouse’s place as host at the head of the table, writes his business letters, and is a conversational companion for Emma. However, Austen does not exactly let the newly minted Knightleys fade off into suburban bliss.

Mrs. Elton is an impediment to their Highbury-wide suburban development. The Sucklings and Maple Grove, not Mr. Knightley and Donwell Abbey, are Mrs. Elton’s models for suburban living. Mrs. Elton’s suburbia is one of display (via barouche-landau rides) and competition (she compares Maple Grove to Hartfield and the Churchills’ estate). She even tries to manage Mr. Knightley’s Donwell Abbey, as its “Lady Patroness” (Volume 3, Chapter 6). While Mr. Knightley limits her plans for her Donwell party (he puts a stop to eating outside and he invites the Woodhouses), Mrs. Elton’s party goes ahead in a way that undercuts Highburian etiquette: she makes fun of Mr. Woodhouse and bullies Jane Fairfax, she has the gypsy “parade” she disingenuously claims not to want to have, and she dominates verbally (prattling about strawberries and Maple Grove). Also, as the Knightleys are about to start their life together at suburban Hartfield, Mrs. Elton gets the last word on their wedding: using Maple Grove standards of “finery” and “parade” (Volume 3, Chapter 19), she finds the simple ceremony wanting.

Mrs. Elton thus challenges George and Emma Knightley, suburban developers. To conclude, I ask what kind of suburbanite you think Mrs. Elton is: does she represent the ascendency of vulgar, consumerist, and competitive upwardly mobile middle-class suburbanites? Or, given Diana Birchall’s defense, does she present a welcome challenge to an outdated rural, gentry, even patriarchal way of living?

Quotations are from the Oxford edition of Emma, edited by R.W. Chapman (1988).

Eighteenth in a series of blog posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Emma. To read more about all the posts in the series, visit Emma in the Snow. Coming soon: guest posts by Kirk Companion, Margaret C. Sullivan, and Cinthia Garcia Soria.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the celebrations! And/or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook , Pinterest , or Twitter ( @Sarah_Emsley ).

February 17, 2016

Friendship, Transformation, and the Hope of Reconciliation

In 2014, when we were celebrating 200 years of Mansfield Park, Margaret Horwitz wrote about “The Comfort of Friendship” for my blog. Today I’m happy to introduce her contribution to Emma in the Snow, a guest post on the friendship between Emma and Mr. Knightley.

In 2014, when we were celebrating 200 years of Mansfield Park, Margaret Horwitz wrote about “The Comfort of Friendship” for my blog. Today I’m happy to introduce her contribution to Emma in the Snow, a guest post on the friendship between Emma and Mr. Knightley.

Margaret has a Ph.D. in Film Studies from UCLA, and she’s a visiting professor of literature at New College Berkeley, an institute of the Graduate Theological Union. She’s a Life Member of JASNA and she’s given many talks on Jane Austen’s novels and their film and television adaptations, as well as on the prayers Austen composed. She presented at the 2004 JASNA AGM in Los Angeles and at the 2008 AGM in Chicago, and in 2008-2009 she was a travelling lecturer for JASNA’s western region.

A few of the recent posts for this series have included photos showing what the weather looks like between December and March in places other than Emma’s Highbury (or my Halifax). In keeping with that pattern, here’s the Golden Gate Bridge, photographed in December by Margaret’s husband, Arnie Horwitz. Thank you for sharing this stunning view with us, Margaret and Arnie, and thank you, Diana Birchall, for your midsummer-themed guest post on “Mrs. Elton’s Donkey” and your photo of a winter sunset in Santa Monica, which prompted me to invite contributors to send photos of scenes that complement or contrast with that half inch of snow in Highbury.

(I wish I’d thought of this idea back in December—I missed the chance to see glimpses of, for example, December in Scotland, where Nora Bartlett lives, or January in Australia, where Susannah Fullerton lives. Ah, well—we’re making it up as we go along, and that’s part of the fun of doing this as a blog series rather than as a formal collection of essays.)

Emma could not bear to give him pain. He was wishing to confide in her—perhaps to consult her;—cost her what it would, she would listen. She might assist his resolution, or reconcile him to it; she might give just praise to Harriet, or, by representing to him his own independence, relieve him from that state of indecision, which must be more intolerable than any alternative to such a mind as his.—They had reached the house.

“You are going in, I suppose,” said he.

“No”—replied Emma—quite confirmed by the depressed manner in which he still spoke—”I should like to take another turn. Mr. Perry is not gone.” And, after proceeding a few steps, she added—”I stopped you ungraciously, just now, Mr. Knightley, and, I am afraid, gave you pain.—But if you have any wish to speak openly to me as a friend, or to ask my opinion of any thing that you may have in contemplation—as a friend, indeed, you may command me.—I will hear whatever you like. I will tell you exactly what I think.”

(Volume 3, Chapter 13, from the Oxford World’s Classics edition of Emma [2008].)

I find this passage one of the most crucial and rewarding moments in Emma. The recurring play on the word “friend” in the novel, and the increasingly significant stages of Emma’s self-awareness, converge in her conversation with Mr. Knightley, who has just returned from London. Harriet Smith’s recent revelation of an attachment to Mr. Knightley, which Harriet feels is reciprocated, has left Emma with the realization of her own love for him, but with little “hope.” In this scene set in the garden at Hartfield, Emma allays Mr. Knightley’s concerns about her response to news of Frank Churchill’s engagement to Jane Fairfax. Emma then progresses through three stages in fulfilling her “resolution,” made the prior evening, to have “better conduct.”

First of all, having noticed Mr. Knightley’s “mortification” at her refusal to let him continue speaking, Emma feels that she “could not bear to give him pain.” She imagines he wishes to “confide in her—perhaps to consult her,” and is afraid she will hear his declaration of love for her young friend and protégée, Harriet. The alliteration in “confide” and “consult” continues and strengthens the word “cost” in her commitment that, “cost her what it would, she would listen,” for the benefit of her lifelong friend, Mr. Knightley. [My italics.]

A pattern of alliteration in the next stage emphasizes Emma’s intent to “assist his resolution” to marry Harriet, or even “reconcile him to it,” in order to “relieve him,” if Mr. Knightley is hesitating because of Harriet’s low social status. Though apprehensive and making assumptions, Emma understands the character of her old friend, recognizing that a “state of indecision” would be “intolerable … to such a mind as his.” She makes a second determination in which she is “quite confirmed,” after noting, but misunderstanding, the “depressed manner” of Mr. Knightley’s comment, “You are going in, I suppose.”

In the third stage, Emma carries out her plan, reminiscent of other points in the novel where recognition of fault causes her to repent. She admits to Mr. Knightley that, “I stopped you ungraciously just now.” Her adding, “and, I am afraid, gave you pain,” returns us to her earlier response that she “could not bear to give him pain.” The repetition of this phrase discloses a movement from inner contrition to verbal confession. Emma courageously invites Mr. Knightley to say what she believes will give her the greatest pain, representing a milestone in her growth.

In fact, she encourages him to “speak openly … as a friend,” and to ask her “opinion of any thing” that he “may have in contemplation,” and repeats the phrase “as a friend,” in an acknowledgment of his privilege as a trusted confidant. Emma’s promise to “hear whatever you like,” and then to “tell you exactly what I think” suggests an increased willingness to confront a truth which she is convinced is unpleasant. Her description of the nature of their conversation indicates a new level of parity in a friendship with overtones of “sister” and older “brother,” given the marriage of their siblings and the difference in their ages.

Emma’s readiness in this passage to “give just praise to Harriet” recalls a much earlier conversation with Mr. Knightley, when she campaigns for Mr. Elton as a suitor for Harriet. In Volume 1, Chapter 8, she “playfully” argues that “such a girl as Harriet is exactly what every man delights in.” She even remarks, “Were you, yourself, ever to marry, she is the very woman for you”—the excruciating possibility Emma believes she is now facing here in Volume 3, Chapter 13, and one she feels would be the consequence of her own misguided behavior.

Though Emma often defends Harriet, both out of affection and a desire to wield influence, her assessment is not “just,” and lacks good judgment, a quality she struggles to gain in the course of the novel. Emma’s willingness to be an advocate is at this point a much costlier act of friendship with regard to both Harriet and Mr. Knightley, since she prepares to set aside her own hopes. It is gratifying to see Emma respond sensitively during (rather than after) what is perhaps the greatest test of her integrity, a demonstration of her advancement in maturity.

Of course, just after this passage, we learn that Mr. Knightley wants to be more than a “friend” to Emma, that she will not be crushed by listening to him, nor need to say anything in support of Harriet’s claims (while having compassion for her). However, as Emma does not yet know this, her meditations and then spoken words mark an admirable resolve, and also indicate a high point in the two characters’ journey toward an even deeper and more balanced friendship in their joint humility.

While one sees a greater emphasis on Emma’s transformation as the title character, Mr. Knightley’s jealousy of Frank Churchill clouds his thinking; he misunderstands Emma’s actions, as she misconstrues those of others. In this novel, no character, however admirable, can really know the mind of another. As readers, we may infer that no human being is omniscient.

Mr. Knightley is afraid he is not the first for Emma, in the same way she fears not being first to him. Yet at this moment, they each approach the other to give solace in reference to a perceived rival. They both meet the challenge of this test by offering comfort, in place of making a claim to be the “first” to the other.

Instead of Emma having to “reconcile” Mr. Knightley to marrying Harriet, he and Emma experience a reconciliation, which began with her repentant action and his forgiving look over the events at Box Hill. These characters resume a primacy in each other’s lives, which they felt was at risk. Though Emma ultimately gives Mr. Knightley an affirmative response to his profession of love for her, the mettle they show in this passage reveals that they can now genuinely be the “friends” they have long called each other, with renewed hope from their transformation.

Seventeenth in a series of blog posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Emma. To read more about all the posts in the series, visit Emma in the Snow. Coming soon: guest posts by Kate Scarth, Kirk Companion, and Margaret C. Sullivan.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the celebrations! And/or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook , Pinterest , or Twitter ( @Sarah_Emsley ).

February 12, 2016

Emma Abroad

Gillian Dow is curating an exhibition focusing on “Jane Austen’s Emma at 200: From English Village to Global Appeal,” which will be open to the public at Chawton House Library from March 21st to September 25th. She’s an Associate Professor at the University of Southampton, and Executive Director of Chawton House Library, where she has worked in a variety of positions since 2005. She has published essays on translations of Austen in the Cambridge University Press Companions to Pride and Prejudice (2013) and Emma (2015), and she and Clare Hanson edited Uses of Austen: Jane’s Afterlives (2012), which “shows how Austen’s life and work is being re-framed and re-imagined in twentieth- and twenty-first-century literature and culture.” Feminisms, Fictions, Futures: Women’s Writing 1660–1830, a collection Gillian edited with Jennie Batchelor, will be published this year by Palgrave.

I’ve been following the updates about the “Emma at 200″ exhibition on Twitter (@ChawtonHouse) and the Chawton House Library Facebook page, and it’s been fascinating to learn about what will be on display. For example, thanks to a collaboration between the Library and the Lady’s Magazine Project “Stitch Off,” visitors will be able to see examples of embroidery based on patterns published in the Lady’s Magazine in 1775 and 1796. In fact, there’s even an opportunity to contribute to the exhibition, which might be of interest to those of you who are skilled in embroidery. (See “The Great Stitch Off Goes to Chawton House Library” for details.) I wish I could make the trip to Chawton this year, but for now I’ll have to content myself with reading about all the wonderful things that will be on display, including first editions, the first French translation, and Charlotte Brontë’s letter about Emma. (I’ve also sent a donation to help support the exhibition, and I’ll include the link to the donation page here in case some of you feel inclined to do so as well.)

I’m delighted to introduce Gillian’s guest post for “Emma in the Snow”—and the fabulous images that accompany it. So far in this series, we’ve had pictures of editions of Emma, and pictures of snow (and pictures of palm trees and flowers…), but we haven’t seen Emma in the snow. Until now. Thanks, Gillian!

This image is courtesy of Goucher College, Baltimore.

When Sarah contacted me to invite me to take part in her “Emma in the Snow” series, I had only the roughest of outlines of what I wanted to say. But I knew at once what image I would use to accompany my post. Here, in a walking outfit, is a 1951 Finnish Emma in the Snow—complete with muff, and a delightful bustle. A transposition of language and, of course, period. This Emma might have walked out of the fashion pages of the 1880s or 1890s. And so might the figures walking away from her in the background—Jane Fairfax and Frank Churchill? Harriet Smith and Mr. Elton? Was claret the winter colour for 1888? Is this Emma inspired by the New Woman in literature of the 1880s—by Ibsen, Henry James or indeed Olive Schreiner? So many questions to ask the Finnish publishing house, the designer, and the translator.

In recent years, my own work on Jane Austen—and indeed my place of work—has led me to think about the importance of understanding place and period in an understanding of the novels. It’s a historicist argument, of course. The late great Marilyn Butler wrote, forty years ago in Jane Austen and the War of Ideas, that “No book is improved by being taken out of its context.” And I’m well placed to consider context and authentic setting: my office overlooks the kind of landscape described by Emma in Emma on her visit to Mr. Knightley’s seat. Donwell Abbey—with “its abundance of timber in rows and avenues”—and rambling and irregular Chawton House—with “many comfortable, and one or two handsome rooms”—have a great deal in common.

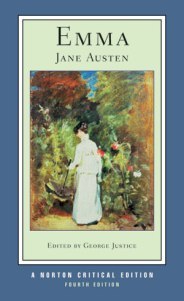

Certainly, literary tourism would not exist if generations of readers did not feel that much was to be gained from a visit to authors’ homes, and the places that inspired their work. And yet an immersive fictive experience—which I am sure most readers of this blog will agree Austen’s Emma is—cannot, must not, depend on where one is when one reads a book. Whether sitting under an English Oak, next to a cactus, or up a brutalist skyscraper in the centre of a metropolis, one creates the world of a novel oneself. I reread George Justice’s edition of Emma in the snow myself this January, when I had the good fortune to spend a few days in the French Alps. The Alpine setting neither enhanced, nor detracted from, Austen’s characters and their world.

Emma in the Alps

This has some implications for the popularity of Austen’s Emma in the global literary marketplace—something I explored in an essay for Peter Sabor’s Companion to the novel (The Cambridge Companion to Emma [2015]). I was very taken by Janet Todd’s recent post for this series on the English nationalism apparent in Emma. I quite agree. But the continent of course impinges—and not only through Emma’s own reading (remember it’s Stéphanie-Félicité de Genlis’s Adelaide and Theodore that Emma brings to mind when she reflects on the birth of a daughter to Mrs. Weston). I’m still struck, when looking at the fate of Emma abroad, how little the English setting of three or four families in a country village mattered to foreign publishers and translators. They have always reworked the novel to suit the tastes of their original readers.

Take the first French translation, published as La Nouvelle Emma in 1816, just a few short months after the original English was brought out by John Murray, himself a publisher with a finger in many continental pies (he had published Germaine de Staël’s De l’Allemagne in both French and in English translation just two years previously). Nearly all the names for Austen’s characters in this first French translation are made more appealing to the first readers. Emma Woodhouse remains “Emma,” and Augusta Hawkins is still Augusta, but Frank Churchill becomes “Franck,” and other names are turned into their French equivalents: “Jeanne” and “Jean” for Jane Fairfax and John Knightley, “Georges” for Mr. Knightley himself, and in the case of plain Harriet Smith, the Frenchified “Henriette.” Some passages are shortened: Miss Bates’s monologues seem to have tried the patience of the first French translator much as they did Emma herself. And by the third volume, the translator seems to have been running out of steam—more small cuts are apparent in this volume than in others.

There is also one very notable change in the text that cannot have been due to exasperation or fatigue. The passage in which Mr. Knightley comments on Frank Churchill’s character is very well known:

No, Emma, your amiable young man can be amiable only in French, not in English. He may be very “aimable,” have very good manners, and be very agreeable; but he can have no English delicacy towards the feelings of other people: nothing really amiable about him. (Volume 1, Chapter 18)

A contrast between the French and English characters, to the detriment of the French, is commonplace in British Romantic-period fiction, and of course has its roots much further back in literary history. Michèle Cohen has demonstrated convincingly that during the eighteenth century “sprightly conversation,” paying of compliments, and verbosity began to represent “the shallow and inferior intellect of English women and the French” (Fashioning Masculinity: National Identity and Language in the Eighteenth Century [1996]). In Emma, French manners represent a genuine threat to the English social order and customs: the threat is embodied in Frank Churchill himself, with his appetite for “abroad” fuelled by perusing “views in Swisserland” (Volume 3, Chapter 6). Here is how the translator of La Nouvelle Emma renders Georges Knightley’s discussion of Franck Churchill:

Non, Emma, votre amiable jeune homme ne peut l’être qu’en italien et non en anglais. Il peut etre très-agréable, tres-bien élevé, tres poli, mais il n’a pas cette delicatesse anglaise qui porte a compatir aux sensations d’autrui.

There is elision here, certainly: Mr. Knightley’s “nothing really amiable about him” is completely lost in translation. More striking, however, is the replacement of the counterfoil to true English delicacy with not a lesser French “amiability,” but an inferior Italian sense of the word. The translator must have felt that this slight to the French character would be too much for the intended readers in the French-speaking world.

It’s perhaps a testament to her broad appeal and her durability that Austen’s novels have crossed borders and settings—in print and on screen—since their first appearance. This Emma Abroad is perhaps not exactly the Emma we Anglo-American readers know and love. But she has countless admirers of her own.

Sixteenth in a series of blog posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Emma. To read more about all the posts in the series, visit Emma in the Snow. Coming soon: guest posts by Margaret Horwitz, Kate Scarth, and Kirk Companion.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the celebrations! And/or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Pinterest, or Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley).

February 10, 2016

Mrs. Woodhouse

George Justice is the editor of the Norton Critical Edition of Jane Austen’s Emma (2011). He specializes in eighteenth-century literature and has written and edited books and essays on the literary marketplace, authorship, and women’s writing. He’s Dean of Humanities in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and Associate Vice President for Humanities and Arts in the Office of Knowledge Enterprise Development at Arizona State University.

George Justice is the editor of the Norton Critical Edition of Jane Austen’s Emma (2011). He specializes in eighteenth-century literature and has written and edited books and essays on the literary marketplace, authorship, and women’s writing. He’s Dean of Humanities in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and Associate Vice President for Humanities and Arts in the Office of Knowledge Enterprise Development at Arizona State University.

When I hosted a party for Mansfield Park a couple of years ago, George contributed a defense of Mrs. Norris. For Emma in the Snow, he’s written a guest post on Emma’s late mother, Mrs. Woodhouse. He’s also sent this beautiful photo of Phoenix, Arizona in winter.

I’m realizing I know quite a few Austen scholars who live in places where it’s warm all winter—or at least not as cold and snowy as it is in my corner of Canada. In case you missed the recent guest posts by Diana Birchall, Elisabeth Lenckos, and Cheryl Kinney, you can find their photos here: winter in Santa Monica, London, and Texas. Meanwhile, we’ve just had two snow days in a row here in Halifax….

I’m thinking of the contrast with Highbury, where “the snow was nowhere above half an inch deep—in many places hardly enough to whiten the ground.” Instead of taking pictures of the snowbanks in front of my house, however, I decided to show you my photo of the view from Point Pleasant Park yesterday afternoon, after the blizzard had ended.

Okay, now that I’ve finished my weather report, let’s move on to more important things. It’s a real pleasure to introduce George’s contribution to the Emma celebrations.

At what age would memories of a mother’s caresses be “indistinct”? For Emma, twenty years old, that must have been a long time ago. The narrator of Emma does not specify exactly when Emma’s mother had died, but from my own experience of losing a mother in childhood, and comparing my own memories with those of my brothers, Emma must have been seven or younger when her mother died.

It has always seemed strange to me that the narrator of Emma proclaims that little had vexed her heroine up until the time of the events of the novel. My own mother died when I was nine, and although I, like Emma, lived a relatively calm and peaceful childhood, with the “place” of my mother taken by a loving, Miss Taylor-like step-mother, I would have to say that my mother’s death from cancer was indeed highly vexing, not only to me but to my entire family.

And so I must project vexation onto Mr. Woodhouse, who never remarried and apparently made a rapid transition from husband to valetudinarian, depending on Miss Taylor and his two daughters for female guidance and upon Mr. Knightley, Miss Taylor, and Emma to keep the business side of Hartfield going.

Most marriages in Jane Austen’s novels are pretty bad, and it’s easy to project a severe level of dysfunction onto the marriage of Emma’s parents. Was Mrs. Woodhouse, like Pride and Prejudice’s Mr. Bennet, the victim of a certain passion (in this case for money?) that led her into an intellectually unequal match? She seems to have had no connections in Highbury—at least there are no parents or siblings on display, or even mentioned, in the pages of Emma. Perhaps, like one Augusta Hawkins of Maple Grove, Mrs. Woodhouse married a narcissist husband to escape from an unfortunate situation?

Let’s look at the text to glean what we might about Emma’s mother. There is very little: evidence comes directly only from Mr. Knightley’s lament that a lack of her strong mother’s guidance has led Emma astray; instead of an accomplished, disciplined perfect woman of her day, he implies, we have a flawed, headstrong, occasionally self-involved young woman. (Would the novel’s readers want her any other way?)

The less direct evidence I want to consider comes from the case of Emma’s older sister Isabella, who was not presumably too young to forget her mother’s caresses. Most critics and readers look at Isabella as her father’s daughter, whereas Emma might take after her mother. And the comparisons with Mr. Woodhouse and Isabella are too strong to overlook. Obsessions with food, health, and a smothering sense of familial affection; perhaps the character most like Mrs. Woodhouse would be Mr. John Knightley!

In Volume 1, Chapter 5, Mr. Knightley says, “At ten years old, [Emma] had the misfortune of being able to answer questions which puzzled her sister at seventeen. She was always quick and assured: Isabella slow and diffident. And ever since she was twelve, Emma has been mistress of the house and of you all. In her mother she lost the only person able to cope with her. She inherits her mother’s talents, and must have been under subjection to her.” It’s unclear to me (at least) why inheriting her mother’s talents would have resulted in Emma being under subjection to her—except in the vacuum left by the vapidity of Isabella and Mr. Woodhouse. And, in any case, why should such strong talents require “subjection”?

Mr. Knightley here is wrong: it is no misfortune for Emma to be able, at ten, to answer questions that puzzled her seven-year-older sister. This is an example of the novel’s requiring Mr. Knightley to change as much as Emma must change. Especially since the words “mother” and “motherly” are often used in the novel in relation to gentleness and warmth—overwhelmingly both in direct reference and in qualitative judgment to old Mrs. Bates, Miss Bates’s oft-referred to mother.

Other characters lost their mothers at an early age, including Frank Churchill (for whom Mrs. Weston serves as a surrogate “mother,” just as she had for Emma) and Jane Fairfax, who does not seem to have suffered from want of a mother in the way that Mr. Knightley associates with Emma. And even Mrs. Elton had lost her mother (as well as her father) sometime before marrying her “cara sposo.”

Mrs. Woodhouse’s death was certainly a misfortune to herself, to Mr. Woodhouse, to Isabella, to Emma, and to others in Highbury. But if Mrs. Bates is the ideal of motherhood in the novel, perhaps the strength of character and independence attributed to Mrs. Woodhouse had even less space in her pre-Wollstonecraftian world than Emma will have in post-revolutionary Britain. The inanities of the various mothers in Emma therefore might serve as commentary on the world that threatens to hold Emma down.

There are two moments of hope for mothers at the end of the novel. First, Mrs. Weston, motherly in a positive sense, gives birth to a daughter. But more generally, Emma married to Mr. Knightley and Jane Fairfax to Frank Churchill provide a sense that future generations will be raised by relatively egalitarian parents in modern marriages. Death may or may not intervene (we wouldn’t wish it for Mrs. Weston, Emma, or Jane Fairfax), but all three women have had a profound and positive impact on their husbands, not to manage them (as Mrs. Woodhouse must have done) but to rationalize them. We don’t believe that little Henry will inherit Donwell Abbey, even if he seems to be the heartier of Isabella’s two boys. Instead, we can’t help but believe that the happy ending of Emma will be as much about what happens in the future to Highbury as what has happened in the past, including the death of Mrs. Woodhouse and others of the novel’s absent mothers.

Fifteenth in a series of blog posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Emma. To read more about all the posts in the series, visit Emma in the Snow. Coming soon: guest posts by Gillian Dow, Margaret Horwitz, and Kate Scarth.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the celebrations! And/or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook , Pinterest , or Twitter ( @Sarah_Emsley ).

February 5, 2016

Mr. Woodhouse and What Matters in the End

Dr. Cheryl Kinney is a gynecologist in Dallas, Texas, and she has given lectures in the United States, Canada, and England on women’s health in the novels of Jane Austen and other eighteenth and nineteenth century British authors. I’m looking forward to hearing her speak at the Jane Austen Society (UK) conference here in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in June of 2017. (You can find out more about that conference on the JAS website; John Mullan, Peter Sabor, Sheila Kindred, and I are the other speakers.)

Dr. Cheryl Kinney is a gynecologist in Dallas, Texas, and she has given lectures in the United States, Canada, and England on women’s health in the novels of Jane Austen and other eighteenth and nineteenth century British authors. I’m looking forward to hearing her speak at the Jane Austen Society (UK) conference here in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in June of 2017. (You can find out more about that conference on the JAS website; John Mullan, Peter Sabor, Sheila Kindred, and I are the other speakers.)

Cheryl has also lectured extensively to various groups on issues relating to gynecology including menopause, sexual dysfunction, endometriosis, and pelvic surgery. She received her M.D. from Indiana University, and she serves on the National Advisory Board for the Laura W. Bush Institute of Women’s Health and the Executive Dean’s Advisory Board for the College of Arts and Sciences at Indiana University. She’s been listed in “Best Doctors in America” since 2001, she’s been named by the Consumers’ Research Council as one of “America’s Top Obstetricians and Gynecologists” every year since 2002, and for the past ten years, she’s been named a “Texas Super Doctor” by her peers. She served on the national board of the Jane Austen Society of North America from 2010 to 2015, and she’s secretary of the board of the Jane Bozart Foundation.

When I hosted a party for Mansfield Park a couple of years ago, she wrote about “Why Tom Bertram is right that Dr. Grant will ‘soon pop off.’” I’m delighted to welcome her back to my blog to celebrate Emma. For her contribution to Emma in the Snow, Cheryl has sent this guest post on Mr. Woodhouse, along with a photo of Texas in winter.

Photo by Wallis Kinney

Mr. Woodhouse came in, and very soon led to the subject again, by the recurrence of his very frequent inquiry of “Well, my dears, how does your book go on? Have you got any thing fresh?”

“Yes, papa, we have something to read you, something quite fresh. A piece of paper was found on the table this morning—(dropt, we suppose, by a fairy)—containing a very pretty charade, and we have just copied it in.”

She read it to him, just as he liked to have any thing read, slowly and distinctly, and two or three times over, with explanations of every part as she proceeded—and he was very much pleased, and, as she had foreseen, especially struck with the complimentary conclusion.

“Aye, that’s very just, indeed, that’s very properly said. Very true. ‘Woman, lovely woman.’ It is such a pretty charade, my dear, that I can easily guess what fairy brought it. Nobody could have written so prettily, but you, Emma.”

Emma only nodded, and smiled. After a little thinking, and a very tender sigh, he added—

“Ah! it is no difficulty to see who you take after! Your dear mother was so clever at all those things! If I had but her memory! But I can remember nothing.”

(Volume 1, Chapter 9, from the Cambridge edition of Emma [2005], edited by Richard Cronin and Dorothy McMillan)

Average human life expectancy at the time of the birth of Jesus was thirty-two years. By the time Jane Austen was writing Emma it was forty-one years. Growing old was not a reasonable expectation for most of the population then. That Jane Austen was aware of this actuality is evidenced by the number of parentless young people in her novels. Modern scientific advances have profoundly altered our lifespan by mitigating the dangers of childbirth, disease, and injury, resulting in a current life expectancy of approximately eighty years. But all of this medical progress has left us vulnerable to the physical and cognitive declines that accompany old age and to the challenges aging presents. In Emma, Jane Austen reveals her remarkable insight into this aspect of human existence with her depiction of Mr. Woodhouse.

Although we are not provided with Mr. Woodhouse’s exact age, he is described by the author as a “kind-hearted, polite old man” (Volume 2, Chapter 16). Yet we soon notice that he is not old in the manner of the hard-of-hearing, blind without her glasses old Mrs. Bates. Mr. Woodhouse has memory lapses, repeats himself, is unable to understand a joke, is unequal to his conversation partners, has to have his business affairs explained to him, and becomes anxious about going out or being left alone. If presented to a doctor today, Mr. Woodhouse would almost certainly be diagnosed with some degree of cognitive impairment.

In order that Mr. Woodhouse will be endeared to readers, Jane Austen constructs his limitations to leave other parts of his personality unblemished—his courtesy, his politeness, his paternal love and devotion. Recent research has shown that memory loss much more profound than Mr. Woodhouse exhibits may leave intact other notable human traits. Doctors have just reached this conclusion within the last decade. Jane Austen obviously understood it 200 years ago.

Despite Mr. Woodhouse’s good qualities, there is little question that we are supposed to understand how difficult it would be to live with him. Mrs. Weston wonders at the end of the novel who besides Mr. Knightley might ever have wanted to marry Emma if a condition for doing so was to move in with Mr. Woodhouse. When Emma accepts Mr. Knightley, she is filled with joyful gratitude and relief. She reveals how acutely aware of her father’s mental and physical decline she is when she considers that Mr. Knightley will be “such a companion for herself in the periods of anxiety and cheerlessness before her!” (Volume 3, Chapter 15) To the 29% of us who provide unpaid caregiving to a relative or friend, no explanation of Emma’s expression is necessary.

For Jane Austen a character’s response to the plight of others often defines their morality. Throughout the novel Emma shelters and soothes her father, entertains him, arranges his social engagements, compensates for his misjudgments and eccentricities, and protects him (with assistance from the author) from becoming an object of pity or ridicule. There are so many instances of Emma manipulating the “environment” for the comfort of her father and they are arranged so cleverly in the story that we barely notice them as claims on Emma.

Other characters in the novel are measured morally by whether they are able to follow Emma’s lead—Frank Churchill obviously is not. Mr. Knightley clearly does. With the relentless demands on Emma, her patience and assiduities are truly remarkable and in this light her imaginings may be better understood as a coping mechanism for her day-to-day stresses. Usually in a Jane Austen novel, the heroine becomes a heroine when she learns from her mistakes, but in this novel we come to understand that it is Emma’s virtuous heart that makes her a heroine, not her recovery from some minor social blunders.

Today, studies show that for most elderly patients a loss of independence is more dreaded than a diagnosis of cancer. In Emma, Jane Austen illustrates how in the pre-modern world a “kind-hearted, polite old man” is allowed to live life as he wants and she shows us the manner in which his dutiful, loving daughter makes it possible. In doing so Jane Austen presents an awareness that though infirmity comes to all, there are lessons to be learned as your loved ones experience such afflictions. The ultimate focus should be a good life for those we love and care for … all the way to the end. A lesson Emma has clearly already mastered.

Cheryl also sent me her daughter Wallis’s photo of bluebonnets, not because they’re in bloom in February, but because they’re the state flower of Texas.

Excellent authors on this aspect of the novel:

Adams, Carol. “Jane Austen’s Guide To Alzheimer’s.” NY Times Op-Ed (12/19/2015).

Basting, Anne Davis. Forget Memory. Johns Hopkins University Press (2009).

Folsom, Marcia McClintock. Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Emma. MLA (2004).

Lane, Maggie. Growing Old With Jane Austen. Hale (2014).

Selwyn, David. Jane Austen and Leisure. The Hambledon Press (1999).

Weinsheimer, Joel C. “In Praise of Mr. Woodhouse: Duty and Desire in Emma.” ARIEL: A Review of International English Literature 6.1 (1975).

Fourteenth in a series of blog posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Emma. To read more about all the posts in the series, visit Emma in the Snow. Coming soon: guest posts by George Justice, Gillian Dow, and Margaret Horwitz.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the celebrations! And/or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook , Pinterest , or Twitter ( @Sarah_Emsley ).

February 3, 2016

The Many Matches of Emma

Sophie Andrews is an ambassador for the Jane Austen Literacy Foundation, which was founded by Caroline Jane Knight, Jane Austen’s 5th great-niece. The Foundation works to provide free books, writing materials, and writing programs to communities in need. Sophie discovered Austen at the age of nine, when she first watched the 2005 film adaptation of Pride and Prejudice, and she tells me she became “a true Jane Austen fan” a few years later when one of her teachers encouraged her to read the novels. She was immediately drawn to the “elegance and eloquence” of Austen’s world, and she’s immersed herself in that world ever since, studying the novels, film and television adaptations, fan fiction, biographies, and literary criticism, and writing for her blog, Laughing with Lizzie.

Sophie Andrews is an ambassador for the Jane Austen Literacy Foundation, which was founded by Caroline Jane Knight, Jane Austen’s 5th great-niece. The Foundation works to provide free books, writing materials, and writing programs to communities in need. Sophie discovered Austen at the age of nine, when she first watched the 2005 film adaptation of Pride and Prejudice, and she tells me she became “a true Jane Austen fan” a few years later when one of her teachers encouraged her to read the novels. She was immediately drawn to the “elegance and eloquence” of Austen’s world, and she’s immersed herself in that world ever since, studying the novels, film and television adaptations, fan fiction, biographies, and literary criticism, and writing for her blog, Laughing with Lizzie.

I’m happy to introduce her contribution to Emma in the Snow, a guest post on the many matches, both real and hypothetical, in Emma. I’ve also enjoyed looking at the photos she sent to accompany the post, and I hope you will, too. Sophie is passionate about sharing her love of Jane Austen and she says she hopes to “encourage people of all ages everywhere to discover the real pleasure of reading.” If you’re interested in talking with her about Jane Austen and the Jane Austen Literacy Foundation, you might want to look her up on Facebook and/or Twitter (@laughingwithliz).

I’m happy to introduce her contribution to Emma in the Snow, a guest post on the many matches, both real and hypothetical, in Emma. I’ve also enjoyed looking at the photos she sent to accompany the post, and I hope you will, too. Sophie is passionate about sharing her love of Jane Austen and she says she hopes to “encourage people of all ages everywhere to discover the real pleasure of reading.” If you’re interested in talking with her about Jane Austen and the Jane Austen Literacy Foundation, you might want to look her up on Facebook and/or Twitter (@laughingwithliz).

Throughout the novel Emma, many different pairings of people are hinted at or hoped for—the book is centred on Emma and her match-making, after all. Now, you’re probably thinking, “yes, I know that,” but I still chose to write about this because it wasn’t until I sat down and remembered each one that I realised just how many matches there are. So, I hope some of you reading this will be just as surprised as I was when I actually thought about it—you’ll have to read to the end to get the final tally. (Or you could count up for yourself and see if your number matches mine at the end.)

First, we have John Knightley and Isabella Woodhouse. This is the first match, and the one that sets Emma off on her match-making schemes, as she believes she was very instrumental in bringing about the marriage of her sister and Mr. Knightley’s brother. This is one of my favourite matches; I do like relationships in which friendship develops into love (not to mention the way this one is linked to the most important match of the novel).