Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 23

February 17, 2017

“I am important to myself”: Emily of New Moon

“I am important to myself,” says Emily Byrd Starr when she’s told by her late father’s housekeeper that she ought to be “thankful to get a home anywhere” and to remember that she’s “not of much importance.” “This is an extraordinary assertion,” writes Mary Henley Rubio, “in an era when young girls were socialized into domesticity, subordinating their identity to their husbands and family” (Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings). Many girls “must have been amazed at Emily’s audacity, while tucking away the comment as an empowering idea,” says Benjamin Lefebvre (The L.M. Montgomery Reader, Volume Two: A Critical Heritage).

This month, I read L.M. Montgomery’s 1923 novel Emily of New Moon for the first time in many years, and while I remembered some aspects of Emily’s journey to become a writer—the diary she burns after her aunt reads part of it, the letters she writes to her father after his death, her ambition to become both a poet and a novelist—I had forgotten just how strict her Aunt Elizabeth is, how cruel her teacher is, and how much Emily has to fight to be taken seriously as a person.

After her father dies and she’s taken to New Moon to live with her relatives, she becomes friends with Cousin Jimmy, who tells her he’s “composed a thousand poems” and has never written any of them down. Emily discovers she, too, can write poetry. “Perhaps I could have written it long ago if I’d tried,” she thinks. Aunt Elizabeth won’t let her have any paper, but Emily finds she can compose in her head, just as Cousin Jimmy does. Sometimes she writes on her slate at school, “but these scribblings had to be rubbed off sooner or later—which left Emily with a sense of loss—and there was always the danger that Miss Brownell would see them.”

Eventually, Miss Brownell does catch her writing, and Emily endures humiliation from her teacher. “Really, children,” Miss Brownell says to her students, “we seem to have a budding poet among us. … It is a whole slateful of—poetry—think of that, children—poetry. We have a pupil in this school who can write—poetry. And she does not want us to read this—poetry. I am afraid Emily is selfish. I am sure we should all enjoy this—poetry.”

[image error]Once again, Emily feels she must destroy what she has written, just as she did even before she came to New Moon, when she saw Aunt Elizabeth reading her diary. She has nothing to wipe her slate clean, so she “gave the palm of her hand a fierce lick and one side of the slate was wiped off. Another lick—and the rest of the poem went.” But then when Miss Brownell threatens to burn the other poems Emily has been keeping in her desk, Emily snatches the pages back from her and, in a scene worthy of Elizabeth Bennet standing up to Lady Catherine de Bourgh in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, she refuses to give them back.

“I will not,” she insists. “They are mine. You have no right to them. I wrote them at recesses. I didn’t break any rules.” And then she adds, “You are an unjust, tyrannical person.” She knows she’ll be punished, but she is determined “they should not get her poems—not one of them, no matter what they did to her.” Near the end of the novel, when Aunt Elizabeth finds and reads Emily’s letters to her father, she again defends her work and refuses to allow it to be destroyed. “I’d sooner burn myself,” she declares. Her attitude toward her writing has changed a great deal since the early chapter in which she burned her diary to prevent her aunt from reading any more of it.

Forced by Aunt Elizabeth to apologize to her teacher, Emily says, “I am sorry for anything I did to-day that was wrong … and I ask your pardon for it.” Forbidden to speak to anyone until the following day, she asks her aunt, “But you won’t forbid me to think?” And, left alone in the pantry to eat only bread and milk for her supper, she begins to compose an epic poem in her mind.

On this reading of the novel, I found Emily’s meeting with Father Cassidy especially interesting. I had forgotten that he’s one of the few people who encourage her to write. She goes to see him to ask him to persuade her neighbour not to cut down the beautiful trees near New Moon. She confesses that she’s a “poetess,” and his initial reply is not very encouraging: “Holy Mike! That is serious,” he says. “I don’t know if I can do much for you. How long have you been that way?” (I’m not sure how I could have forgotten his distinctive voice. I certainly remember Mr. Carpenter’s voice, much later, in Emily’s Quest, telling Emily to “Beware—of—italics.” But I’m getting ahead of myself now, as that’s the novel I plan to read in April.) After she’s told Father Cassidy more about her writing, he tells her to “keep on writing poetry,” which no one else has ever told her, and he assures her that “The path of genius never did run smooth.”

After this conversation, Emily even begins to think she might write novels as well as poems. “But Aunt Elizabeth won’t let me read any novels so how can I find out how to write them?” she wonders, which is an excellent question. (Aunt Elizabeth says, “They are wicked books and have ruined many souls,” but Emily manages to read The Mysteries of Udolpho and The Romance of the Forest before she’s forbidden to read the books at her friend Ilse’s house.)

I love what Emily says when she begins to think of her future audience: “‘Another thing that worries me, if I do grow up and write a wonderful poem, perhaps people won’t see how wonderful it is.’”

I remembered reading about what happened when Mary Rubio gave Alice Munro a copy of Montgomery’s journals, so I looked up that passage again in Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings: Rubio says, “When I handed Alice Munro a gift copy of the first volume of The Selected Journals of L.M. Montgomery, Volume 1, at the Ginger Press Bookstore in Owen Sound, Ontario, in late 1985, she looked at it for only a second to see what it was, and then, without missing a beat or without making any reference to Emily of New Moon, she responded by quoting the end of the novel: ‘I am going to write a diary that it may be published when I die.’” In this short “Appreciation of Alice Munro,” Margaret Atwood and Lisa Dickler Awano talk about how Montgomery’s novels influenced Munro when she was growing up, at a time when “the idea of being a writer was so alien. Just to think you could do it was an act of major hubris.”

The Emily novels have served as an inspiration to many young women who dreamt of becoming writers, as Benjamin Lefebvre notes in The L.M. Montgomery Reader: Volume Two. He mentions, for example, Munro, Atwood, Margaret Lawrence, Astrid Lindgren, Rosemary Sutcliff, Jean Little, and Carol Shields. I know Munro wrote an afterword for Emily of New Moon, but I don’t (yet) have a copy of that edition. Have any of you read it?

In between chapters of Emily of New Moon, I’ve been reading Goodnight Stories for Rebel Girls (2016), a collection of short biographies of strong and inspiring women. L.M. Montgomery doesn’t make an appearance in the book, unfortunately, but I was happy to find that Jane Austen is included. Montgomery and her strong heroines, especially Emily, with her insistence that “I am important to myself,” and Anne Shirley, would fit right in.

[image error]Rebel Girls is intended to be both “heartwarming” and “thought-provoking,” and I’d say both of those terms apply to the collection, right from the dedication page. It’s dedicated “To the rebel girls of the world.” Heartwarming: “Dream bigger, Aim higher, Fight harder.” Thought-provoking: “And, when in doubt, remember, You are right.” I have to say, I think it’s dangerous for any girl, or boy, to grow up believing she or he is always right. There’s no room for education, something that was clearly important to the ambitious women featured in Rebel Girls, just as it was important to Montgomery, and to the fictional Emily Starr, who, for all her confidence in her own importance, is a great example of a heroine who knows she has much to learn, and is determined to get a good education.

This month, I’ve also been rereading Persuasion, because I’m writing a lecture on “Anne Elliot’s Ambitions” for the Jane Austen Society conference in Halifax in June. I was struck by the similarity between the opening of Emily of New Moon, in which Emily’s told she’s “not of much importance,” and the opening of Persuasion, in which the reader learns the Elliot family doesn’t think Anne is important: “She was nobody with either father or sister; her word had no weight. Her convenience was always to give way—she was only Anne.” (Miriam Rheingold Fuller talks about the influence of Persuasion on Montgomery’s Anne of the Island in her essay “Jane of Green Gables: L.M. Montgomery’s Reworking of Jane Austen’s Legacy.”)

Montgomery is most famous, of course, for Anne of Green Gables and its sequels, and, as many readers have noticed, Emily resembles Anne Shirley. Sometimes she even sounds just like her. “Oh, isn’t it good to be alive—like this?” Emily says to her friends Ilse and Teddy during one of the evenings when “they all three sat on the crazy veranda steps in the mystery and enchantment of the borderland ’tween light and dark” and “a great round yellow moon rose over the fields.” “Wouldn’t it be dreadful if one had never lived?” she asks them. This passage makes me think of Anne saying to Diana, in Anne of Green Gables, “It’s good to be alive and to be going home.”

Later in Emily of New Moon, when Emily believes she is going to die after eating an apple and then hearing from her neighbour that it was full of poison, she laments her lost happiness—“She had thought she was going to live for years and write great poems and be famous like Mrs. Hemans”—and then when she finds she hasn’t been poisoned after all, she is thrilled to be alive. “Oh, it was nice just to be alone and to be alive,” and to be able to write more: “Emily already saw a yard of verses entitled ‘Thoughts of One Doomed to Sudden Death.’”

[image error]

I took this photo last winter for a class on The Art of Photography, and I just realized it could work here as an illustration. There was no rat poison in this apple, either. Obviously.

Like Anne, Emily is interested in roads and paths. (I’ve written before about Anne’s love of “The Bend in the Road,” the title of the last chapter of Anne of Green Gables.) Emily talks about three paths through the bush: “the To-day Road, the Yesterday Road, and the To-morrow Road.” One is “lovely now,” one is “out in the stumps” and “used to be lovely,” and the third “is going to be lovely some day, when the maples are bigger.”

[image error]

I’m always glad of an excuse to include a photo of “The Bend in the Road.” This is Warburton Road, in Fredericton, PEI.

With all these similarities between Anne and Emily, it’s fascinating to learn that Montgomery preferred writing about Emily. “It is the best book I have ever written,” she wrote in her journal, “—and I have had more intense pleasure in writing it than any of the others—not even excepting Green Gables. I have lived it, and I hated to pen the last line and write finis. Of course, I’ll have to write several sequels but they will be more or less hackwork I fear. They cannot be to me what this book has been” (February 15, 1922).

As I mentioned in last month’s blog post, Naomi at Consumed By Ink is hosting this Emily Readalong, and the idea is to read Emily Climbs next month and then Emily’s Quest in April. Do those two novels seem like “hackwork”? I don’t remember. Feel free to join us in reading these three novels, by commenting on blog posts or writing your own, or by discussing the books on social media (#ReadingEmily).

In her February post on Emily of New Moon, Naomi talks about the similarities between Anne and Emily and she raises excellent questions about some of the other characters in the novel, particularly Mrs. Kent (controlling?) and Dean Priest (creepy?). She also includes images of many different covers for Emily, noting that in general, the Emily covers are “not as bright and cheery” as the covers of the Anne novels.

One last thought about—or at least tangentially related to!—Emily of New Moon: when I read about Aunt Laura rubbing mutton tallow on Emily’s chapped hands in the winter, I couldn’t help thinking of Dan Macey’s blog post from last winter’s “Emma in the Snow” celebration, because he wrote about “Discovering Mutton in Emma: The Quest to Please the Principals’ Palates.” The word “mutton” always reminds me of the line from Jane Austen’s letter to her sister Cassandra about how “Composition seems to me Impossible, with a head full of Joints of Mutton and doses of rhubarb” (September 8, 1816). And now, the word also reminds me of Dan’s research and the recipes he created for the characters in Austen’s Emma. As it happened, the day after I read the passage about mutton tallow in Emily of New Moon, I learned that Dan’s blog post on mutton has been shortlisted for an International Association of Culinary Professionals Food Writing award. Congratulations, Dan!

(Emily writes, “It is hard to write poetry with chapped hands. I wonder if Mrs. Hemans ever had chapped hands. It does not mention anything like that in her biograffy.”)

This past week in Nova Scotia, we’ve had several snow days, so I’ve been thinking about this Readalong as “Emily in the Snow.” I’ll spare you the photos of the snow mountains in my neighbourhood—I posted plenty of photos of snow last winter during the “Emma in the Snow” celebrations. There’s far more snow this winter; in fact, right now, it looks pretty much the way it did in March of 2015, when I was participating in the Anne of Green Gables Readalong and I included a snow photo in this post on “Attending Redmond College with Anne Shirley.” Just as I did that month, I’m dreaming of a summer visit to PEI (and of raspberry cordial at the Blue Winds Tea Room in New London).

Okay, I think this blog post is long enough. Probably too long. I’m going to stop writing about Emily of New Moon for now, and start reading Emily Climbs. Or maybe I’ll read Felicia Hemans’s poem “Kindred Hearts”….

[image error]

My McClelland and Stewart “Canadian Favourites” edition of Emily of New Moon

January 30, 2017

Rereading L.M. Montgomery’s “Emily” Novels

I’m planning to reread L.M. Montgomery’s “Emily” novels this year, along with Naomi of Consumed by Ink and other bloggers. Anyone want to join us? We’d love to have company.

[image error]

From a short holiday in PEI a few weeks ago

Here’s Naomi’s invitation to participate: “An Emily Readalong.”

February: Emily of New Moon (1923)

March: Emily Climbs (1925)

April: Emily’s Quest (1927)

My “L.M. Montgomery in Nova Scotia” page.

December 16, 2016

Jane Austen and Grandparents

In honour of Jane Austen’s 241st birthday, I’m posting an essay by Nora Bartlett on “Jane Austen and Grandparents.” Nora wrote the first guest post for the blog series on Austen’s Emma that I hosted last winter, and she kindly gave me permission to use the title of her contribution, “Emma in the Snow,” as the title of the whole series.

Nora died of cancer on August 14, 2016, and will be much missed by her family and her friends and colleagues around the world. She taught part-time for more than twenty years at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, she worked with adults in various lifelong learning programs, and she often wrote and lectured on Jane Austen and her novels. I never met Nora in person, but I thought of her as a dear friend, and I miss hearing her voice in the lively letters she sent me. I will treasure the memory of our correspondence about Austen and other writers. We also had several conversations about snow—not enough in Scotland, Nora said, for someone born in upstate New York, as she was, and accustomed to white winters; too much in Nova Scotia, I complained to her during the infamous storms of March, 2015.

It’s a pleasure and an honour to share with you Nora’s essay on grandparents, which she sent to me a few days before she died. I wanted to save it for a special occasion and Jane Austen’s birthday seemed like a good choice. For an author photo, Nora sent me this picture of her with her horse Bert, jumping in the paddock by the sea. She told me he was named after Bert from Sesame Street “and resembles him in rectitude and in looking embarrassed rather than conspiratorial when anyone says or does anything funny.”

You could not, with any confidence, expect to see your grandchildren in the world we have lost. —Peter Laslett, The World We Have Lost

[image error]When Jane Austen was born in 1775, she had no grandparents living, her father having been orphaned young and her mother left parentless by 1768. From her teens, though, she lived with parents who were also grandparents, and her own talents as an aunt are testified to very convincingly in her nephew’s Memoir and elsewhere. For this essay, the question I began with, given the availability of the grandparent-grandchild relationship to her everyday experience, was why so few of her mature novels explore this relationship very fully. There are absurd grandparents in her juvenilia, like the mysterious stranger who comes and goes in a trice in “Love and Freindship”: after finding that he is grandfather to a mounting number of distinctly dodgy young people, he dispenses £50 notes and vanishes. And there are the longsuffering, letter-writing grandparents who battle with dignity against the threat posed to their children and grandchildren by the insidious charms of Lady Susan in that savage, anti-filial little work. But Pride and Prejudice is without depicted grandparents, and Mansfield Park with its disastrous marriage and its many thwarted marriages, almost seems—but only almost, as we’ll see—designed to disappoint all hopes of parents to become grandparents.

In thinking Jane Austen gave little attention to realistic grandparental hopes, wishes, and experiences, however, I was wrong—both from lack of alertness to the novels and from failing at first to realize that, though the Austens were a multi-generation family, such a lucky experience, in a time of high infant mortality, late marriage and early death, was rare. As figures in Peter Laslett’s The World We Have Lost (1965) show, before the economic transformations of the early 19th century, less than 25% of the population of England was ever over 40—in Laslett’s telling phrase, “conversation across the generations must have been rare, much rarer than it is today.” Although the conversation in Emma between Emma and Harriet about Robert Martin’s prospects for marriage mimics the tone of an older, wiser woman advising a very young one and is not a reflection of Emma’s serious thinking—indeed, like much of Emma’s talk, it reflects no thought at all—it does show some knowledge of how her social and economic inferiors made decisions about marriage. Only at the more prosperous level, which Jane Austen usually concentrates on, could a Mrs. Bennet be aiming at the prospect of a marriage for one of her daughters “since Jane was sixteen” (Volume 3, Chapter 8).

The Austens themselves were a long-lived family. Even Jane survived her 40th birthday, and her brothers were able to marry early, and to marry young women, some of whom had their first children while still in their teens. The brothers’ marital experience also reflected the high rate of early death of first wife and husband remarriage, a phenomenon also noted by Laslett. With young children needing a mother’s care, there would often be a remarriage. Of the five Austen brothers who married, four were married twice. The extensive grandparental experience testified to in the Memoir rested on these then-natural developments of family life, but even more it rested on the senior Austens’ long and healthy—despite Mrs. Austen’s claims to invalidism—lives, which were somewhat exceptional, since though the privileged could marry early they could not—despite their greater access to medical care—depend on that care to guarantee better health than lack of such care gave to the poor. Neither the richest of her brothers, nor the poorest, could keep his first wife alive, an experience perhaps reflected in the persistent family myth that Emma’s Jane Fairfax, married into one of the richest families Jane Austen deals with, is to die in childbirth. It might be possible to see the novels as reflecting both the general experience, with not many grandparents about, and her own, with grandparents taking an active role in the upbringing of their grandchildren.

For, as we’ll see, Sense and Sensibility, Emma, and Persuasion on careful examination turn out to be looking quite hard at grandparents and grandchildren. And Persuasion uses the experience of the grandparent and the treatment of grandchildren, rather as some of the other novels use behavior with money, to enable us to see deeply—though often in a quick, deft, sketch-fashion—into the moral and imaginative lives of Austen’s characters. So the question I started with—“why so few grandparents and grandchildren?”—has turned into “why so many”!

[image error]If we run briskly through the novels in order of publication, and jettison Northanger Abbey, that late-published, early-written novel, as of no interest to the discussion because there is not a grandparent in sight, we see that Sense and Sensibility gives us two widowed grandmothers, Mrs. Jennings and Mrs. Ferrars, and one very funny scene in Volume 2, Chapter 12 of these two nearly coming to blows over the relative heights of two of their grandchildren, only one of whom is present. For Mrs. Jennings, the affectionate grandmother, the novel also provides a new baby, “a son and heir” for the daughter to whom she is closer, Mrs. Palmer (Volume 2, Chapter 14). At the novel’s end, there is also an almost coy nudge to the reader, an arch bit of indirection about Elinor’s pregnancy, hinted at via their need for “rather better pasturage for their cows” (Volume 3, Chapter 14). This child will have both Mrs. Dashwood and Mrs. Ferrars as grandmothers, and both women are widows. Thus, like the Middleton children and Harry Dashwood, Edward and Elinor’s baby will have no living grandfather.

[image error]In Pride and Prejudice we are spared seeing how either of the Bennets would anticipate either a Bingley, or a Darcy—or, horrors, a Wickham—baby. That is outside the book’s scope. But there is the “young olive branch” of Charlotte and Mr. Collins. One has great hopes for the humor and good sense with which any child of Charlotte’s will be brought up; and that baby will have two grandparents, in the Lucases, presumably spending more time than ever calculating how long Mr. Bennet is likely to live.

Mansfield Park, as I’ve suggested, operates almost actively against a parent’s natural wish for grandchildren: the wedding we see ends in bitterness and shame, and two prospective marriages between Bertrams (if Fanny here counts as a Bertram, as she seems to when her uncle is pressing for the marriage) and Crawfords fail to come off, and though the marriage between Mr. Yates and Julia turns out to be less catastrophic than circumstances suggested it might, one feels they both need to grow up themselves before any children would be a blessing.

[image error]But with the same coyness—or is it archness?—the sly indirection, the faint nudge, as in Sense and Sensibility, closes the novel as Fanny and Edmund “had been married long enough to begin to want an increase of income, and feel their distance from the paternal abode an inconvenience” (Volume 3, Chapter 12). The plot—Dr. Grant’s bathetic death from over-eating, and the expectation of a grandchild, never made explicit—moves them to Mansfield parsonage, so much easier for the new grandparents. Here is another living pair—this baby will have both grandfather and grandmother. We might note that the move closer to Mansfield is not a move closer to Portsmouth, where there will be another grandparental pair. It seems likely that Mrs. Price will content herself with a note saying she will knit something when she can find some time, and that the Bertrams, deprived of other grandchildren by their parental failings, will reap the grandparental benefits of their generosity in adopting Fanny.

Emma, on the other hand, could almost be thought to have been devised with the grandparental relationship in mind, as Mr. Woodhouse has five grandchildren. Unlike the other young mother of a large family whom we see in the novels, Mrs. Gardiner, who is calm and confident, Isabella Knightley is forever anxious about her own and her family’s health and takes them with her everywhere. Thus Hartfield at Christmas, unlike Longbourn, is full of children. And then in the early summer Emma and her father are left in charge of the two eldest Knightley boys. We see Mr. Woodhouse in action as a grandfather—as much as we see him in action in anything!—mostly fretting about that holiday at the seaside and its threats, then fussing over Mr. Knightley’s tossing the little boys high up into the air, but also enjoying the little word game Emma has made for them, at which he is probably pretty much at their skill level, or not so much below them that it is no fun for anyone but him. Just as he was an anxious father he is an anxious grandfather, although he is a devoted, attentive one. Sadly, we see no scenes of his supervising their eating, which must require much sleight of hand on Emma’s part to get the requisite calories into a pair of hungry boys.

[image error]Like so many of Jane Austen’s grandparents, Mr. Woodhouse is widowed, as is the novel’s other grandparent, his “worthy old friend” Mrs. Bates (Volume 3, Chapter 9). The household over the shop in Highbury is therefore all female, and includes three generations. I think we need to take some time to think about Jane Fairfax’s difficult situation in that too-small house with the endlessly talking and thoroughly well-meaning Miss Bates. Mrs. Bates’s deafness may be a trial to her daughter, though she does not complain, only describes (“I say one thing, and then I say another,” says Miss Bates, which the reader has no difficulty believing [Volume 2, Chapter 9]). But surely Mrs. Bates’s great age and her extreme deafness may sometimes produce the blessed effect of total silence. Mrs. Bates seems quite content to be left out of things, and there must be times when Miss Bates is out, or talking to Patty in the kitchen, and then one imagines Jane pressing her aching head, silently, to some cushion and neither having to speak nor to listen. At times the deaf old lady may have been her best friend and a desperately needed resource.

There is, of course, no sly allusion at the end of Emma to possible babies—who, with Emma, would dare? Beyond the seaside honeymoon all else is outside the novel’s scope; that is, all but perfect happiness. Perfect happiness is in store for the rather more deserving Anne Elliot, too, at the end of Persuasion, but, like Emma, Persuasion is a book about grandparents and grandchildren. The warm, unaffected Musgroves offer the reader the opportunity to observe a grandparent’s trials, perhaps more than a grandparent’s rewards. Parents themselves almost beyond count, the older Musgroves have not been prepared by their own (mostly) happy and contented children for dealing with the consequences of Mary’s sulky, erratic mothering, as Anne learns on arrival at Uppercross: “Oh! Miss Anne, I cannot help wishing Mrs. Charles had a little of your method with those children. . . —Bless me! how troublesome they are sometimes” (Volume 1, Chapter 6). “Troublesomeness”—which the reader sees again and again, which steadily advances the plot and helps control the novel’s action as it slowly turns and turns, returning Anne and Captain Wentworth to a right knowledge of their own feelings.

Many readers have been struck by the physical intensity of the scene in which the toddler is clinging stickily to Anne’s neck until a whirling moment in which “she found herself in the state of being released . . . someone was taking him from her . . . Captain Wentworth had done it” (Volume 1, Chapter 9). Maria Edgeworth, for example, wrote to a friend in 1818, “Don’t you see Captain Wentworth taking the boisterous toddler off her back as she bends over the sick boy on the sofa? Or rather don’t you feel it?” (quoted in Marilyn Butler, Jane Austen and the War of Ideas [1988]).

Persuasion is the novel in which Jane Austen risks more of these high-intensity, shatter-the-surface moments. The last one at the White Hart inn in Bath will leave Anne, in Charles’s Musgrove’s honest, affectionate words, “rather done for” (Volume 2, Chapter 11), as the moment of Anne’s release from her nephew leaves most readers.

Another exceptionally rich moment that focuses on grandchildren is the Christmas scene at Uppercross Hall. This time, the grandparents are securely in control, and the scene has no role in the plot except to demonstrate to the reader how Anne has learnt, in the months at Uppercross, to relax and enjoy herself. The scene bears comparison, lean and concise though it is in style, with the glorious hyperbolic Christmas at old Fezziwig’s that haunts Scrooge in Dickens’s A Christmas Carol:

[image error]There were more dances, and there were forfeits, and more dances, and there was cake, and there was negus, and there was a great piece of Cold Roast, and there was a great piece of Cold Boiled, and there were mince-pies, and plenty of beer. But the great effect of the evening came . . . when the fiddler . . . struck up “Sir Roger de Coverley.” Then old Fezziwig stood out to dance with Mrs. Fezziwig. Top couple too; with a good stiff piece of work cut out for them; three or four and twenty pair of partners; people who were not to be trifled with; people who would dance, and had no notion of walking.

This section is about a page long; Uppercross Christmas, so trim it is easy to miss, is a paragraph in Chapter 2 of Volume 2, and depicts the visiting Harville children, the Musgrove children home from school. The girls gather around the table, “chattering” and “cutting up silk and gold paper,” while at a host of other tables “bending under the weight of brawn and cold pies . . . riotous boys were holding high revel,” and the scene is “completed by a roaring Christmas fire.”

Without the sensory overload—the “more” and “more” of the Fezziwig scene—there is nevertheless a quality of perfectly judged sensory delight here: one hears the “chatter,” and almost hears the scissors snipping, sees the pleasurable flimsiness and flash of gold and silk, smells those pies, and all is brought together with care by the solidity of the tables and trestles, and the sound of the fire, which gives the reader gratifyingly more than just enough, but never too much.

But we would want to note that even in the midst of this idyll there is grandparental labor to be done, the “sedulous guarding” of the well-brought up young Harvilles “from the tyranny of the two children from the Cottage, expressly arrived to amuse them.” As with the list of pleasures, every word here describing the pains of family life is placed with care, and the irony of “tyranny”/“amuse” speaks very clearly to the reader who has paid attention to those unruly young boys. Affection and fun—Mr. Musgrove shouting into Lady Russell’s ear while small children clamor on his knees—but “guarding,” too. This “fine family-piece,” as the paragraph concludes, is also a fine grandparental piece.

If this is an almost symbolic moment, renewing the early admiring tones about the elder Musgroves being formed in “the old English style” (Volume 1, Chapter 5), the famous picture with which the novel opens, of Sir Walter Elliot reading his own entry in the Baronetage, has its symbolic aspect, too. From the image of Sir Walter reading we are moved right into looking over his shoulder to read exactly what he is reading, and also to see what, in the past, he has written into this moveable feast of a book. And if we see the Musgroves through their commonplace everyday pleasures, we see Sir Walter through his—and through the pleasures and pains he has avoided.

[image error]Sir Walter has amended the entry—“improved it by adding, for the information of himself and his family, these words, after the date of Mary’s birth—‘Married, December 16, 1810, Charles, son and heir of Charles Musgrove, Esq. of Uppercross, in the country of Somerset,’ and by inserting most accurately the day of the month on which he had lost his wife.” One feels intuitively that Sir Walter would have beautiful penmanship. There are no blots or splodges there. And well-known though it is, the paragraph—the corrected paragraph in particular—gives us much to think about. He has not added the births of his grandsons, who, of course, do not carry the Elliot name. They are not in line to inherit the baronetcy, or Kellynch Hall. Neither will they be dependent on the now-shaky Elliot finances for their own start in life. Whatever of “pride—the Elliot pride” (Volume 1, Chapter 10) Mary manages to pump into them will not be enhanced by their grandpapa’s efforts.

His total silence here about the grandchildren is echoed throughout the novel, as Sir Walter nowhere—nowhere—acknowledges that he is a grandfather. Can it be his vanity, his unwillingness to consider himself old enough for the grandfather role? Possibly. But possibly it is something even less active, and more repellent: Sir Walter does not seem to remember that his grandsons exist. The messages sent to Mary by Sir Walter and Elizabeth do not mention the boys—something which the narrative highlights by contrasting Mrs. Clay’s “more decent attention, in an inquiry after Mrs. Charles Musgrove, and her fine little boys” (Volume 2, Chapter 6). In every inquiry after the Cottage household it is only Mary—the Elliot—who is mentioned, though even there neither father nor sister waits to hear the answer. When Mary and Charles arrive in Bath the boys are not mentioned. Since we have no quoted or reported speech from the two little Cottage boys—or any other child—it isn’t really possible to estimate the importance the Elliot side of the family has in their imaginations. It feels as if Sir Walter may have as little presence in their lives as they have in his.

Neither side could have the role the cultivated Austens played in their grandchildren’s lives, of inspiring reading and writing. The male Musgroves cheerfully accept their limitations, to “sport; . . . without benefit from books or anything else” (Volume 1, Chapter 6), while the ladies focus on household matters, dress, a little light music. But despite all the pride, we are assured that Sir Walter never reads anything but the Baronetage, and every time we see Elizabeth with a book she is closing it. And I think we can feel reasonably sure that Mary’s delight with the Lyme circulating library is not caused by her finally being able to get hold of Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Women! Where the depiction of grandparents may reflect Jane Austen’s own experience, though, is in the Musgroves, however commonplace and rough-hewn they are, because they are shown, as the Austens are in the letters and the family Memoir, in loving connection with their grandchildren, not just at Christmas, but every day. The chilly blank of Sir Walter’s lack of connection thus has in the Musgroves a moral yardstick—but also something more.

For one thing of which Sir Walter is not accused by the world who would call him a “foolish, spendthrift baronet” (Volume 2, Chapter 12) is a lack of family pride. Yet, just as the novel shows from the outset that his pride in Kellynch Hall is something of a delusion (as he deserts it at the first opportunity), it also shows him—and it is in the treatment of his living descendants that it shows him—essentially without the real family pride that keeps the Baronetage going.

The “book of books” is steeped in dynastic drive. Those marriages to “Marys” and “Elizabeths” that made and marred fortunes and futures, the “exertions of loyalty” “mentioned in Dugdale,” though set in the past, were made by men and women who thought not only of their family name but about the future of that name—about their legacy, their descendants (Volume 1, Chapter 1). Some of the Elliots of the past must have been violent men and determined women, carving out a dynasty, not a race of courtiers and fops gazing into an endless series of mirrors. Sir Walter cannot be blamed for—like Mr. Bennet—failing to produce a male heir. (The reader feels sure poor Lady Elliot, leaving three daughters, bore the brunt of that blame.) But he can be blamed, and is, in the novel, both by his own grandparental blanks and the Musgroves’ steady exertions: their undemonstrative energy—they are an old county family that is rising in the world, not falling—is contrasted with Sir Walter’s and Elizabeth’s stasis.

In the White Hart scene which gives so much warmth and bustle, chatter and action to the second volume of the novel, there is the unforgettable eruption—missile-like—of Sir Walter and Elizabeth which effects a physical drop in temperature, “a general chill . . . an instant oppression” of the happy group spirit which shames Anne (Volume 2, Chapter 10). Throughout the novel we see her, though a dutiful and loyal, uncomplaining daughter and sister to these worthless people, shamed by their callousness and irresponsibility. That Anne, thoughtful Anne—and like Jane Austen Anne is a loving aunt, who even in her darkest hours can take some pleasure in having been of use in caring for the little boys—does not reflect, as far as the reader knows, on her father’s shortcomings as a grandparent. She is aware of his failings in upholding the values of “an ancient family,” and sadly certain the Elliot tenants and other dependents will be better looked after by the incoming Crofts: she “felt the parish to be so sure of a good example, and the poor of the best attention and relief, that however sorry and ashamed for the necessity of the removal, she could not but in conscience feel that they were gone who deserved not to stay, and that Kellynch Hall had passed into better hands than its owners’” (Volume 2, Chapter 1). And of course the childless Admiral Croft, in a scene with the little boys, behaves much more like an indulgent grandfather with them, than even Mr. Musgrove does (Volume 1, Chapter 6).

At the opening of Volume 2, “the little boys at the cottage”—left to the care of servants as the family from the big house leave to support Louisa at Lyme—are presented in an almost symbolic way, an analogue to Anne’s own neglect. In reality, of course, elements are already in motion which will transform her condition, and in a few months she will be “a sailor’s wife” who “glorie[s]” in her situation (Volume 2, Chapter 12). And the boys at the Cottage—one imagines them stuffed with cake while the servants gossip and flirt—probably enjoy the license of their temporary situation, which Christmas, as we’ve seen, will transform. It doesn’t seem likely that they suffer from the temporary neglect here any more than from the steady neglect by their maternal grandfather. But, like the one-book reading list and the mirrored dressing room and the reduction of meaningful connections to the family member who most resembles that dressing room, this grandparental inertia defines Sir Walter’s character, and shows him failing not only as a paterfamilias—that would mean nothing to him—but as an Elliot. And that would shame even Sir Walter.

Quotations from Austen’s novels are from Mollands.net.

Here are the links to the other guest posts Nora wrote for my blog:

“. . . the snow in Emma is one of those events which provides everyone present with the opportunity to act intensely in character. . . .”

“Pauses: Moments in Jane Austen When Nothing and Everything Gets Said”:

“. . . the ‘pause’ is often a moment when a character is suppressing a laugh, or an angry reply: it stands for a rebellion that does not take place, or takes place only internally.”

[image error]

This is the photo I used last year for the “Emma in the Snow” blog series. I’m including it again here not only because it was the illustration for Nora’s guest post on snow, but because it’s a view of Lake Newell, Alberta, from the spot where my own grandparents built a summer cabin for their family in the 1950s, and thus it seems to me that it’s equally appropriate for a post on grandparents.

November 1, 2016

The Republic of Love Bookmark and the Carol Shields Memorial Labyrinth

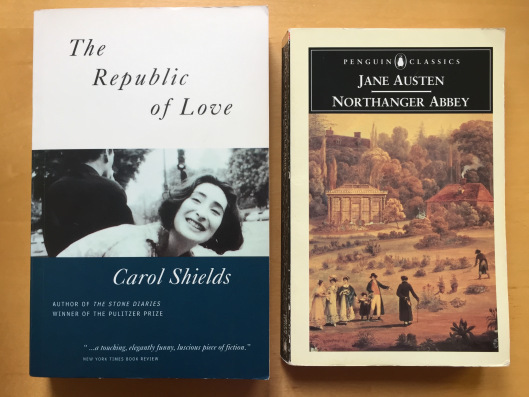

“Just a love story, people say about a book they happen to be reading, to be caught reading. They smirk or roll their eyes at the mention of love…. It’s possible to speak ironically about romance, but no adult with any sense talks about love’s richness and transcendence, that it actually happens, that it’s happening right now, in the last years of our long, hard, lean, bitter, and promiscuous century. Even here it’s happening, in this flat, midcontinental city with its half million people and its traffic and weather and asphalt parking lots and languishing flower borders and yellow-leafed trees—right here, the miracle of it.” This passage is from The Republic of Love, by Carol Shields, and I expect it probably sounds somewhat familiar to readers of Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey:

“Oh! it is only a novel!” replies the young lady; while she lays down her book with affected indifference, or momentary shame.—“It is only Cecilia, or Camilla, or Belinda;” or, in short, only some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language.

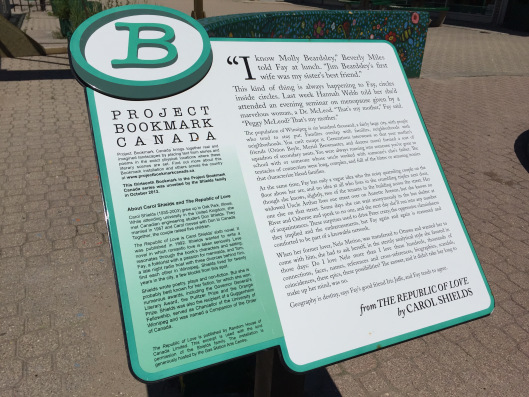

“Just a love story”; “only a novel!” The Republic of Love is one of my favourite Carol Shields novels, partly because of the Austen connection, and I was delighted to have the opportunity to visit the Project Bookmark Canada marker for the novel when my family and I spent a day in Winnipeg, Manitoba this past summer (during our road trip “From Halifax to Vancouver and Home Again”). My book club is reading The Republic of Love this month, so I decided this would be a good time to share these photos in a blog post.

The Bookmark is at the corner of River and Osborne, where the heroine, Fay McLeod, often waits in the bus shelter. One of the things Fay loves about Winnipeg is that “You were always running into someone you’d gone to school with or someone whose uncle worked with someone else’s father…. Fay again and again is reassured and comforted to be part of a knowable network.” (Read more about The Republic of Love Bookmark on the Project Bookmark Canada website.)

I love the idea of a “literary TransCanada highway,” as Kristen Den Hartog has described these Bookmarks that stretch from Vancouver, BC to Woody Point, Newfoundland.

We now have one in Nova Scotia: the Bookmark honouring Alistair MacLeod’s novel No Great Mischief was unveiled just over a year ago, in Port Hastings, Cape Breton, and it features a passage from the end of the novel, including the famous last line: “All of us are better when we’re loved.”

I haven’t been to see the No Great Mischief Bookmark yet, even though I live in Nova Scotia—but I’ll get there! That day in Winnipeg, we also visited the Carol Shields Memorial Labyrinth.

Thinking about connections between The Republic of Love and Northanger Abbey prompted me to revisit Shields’s biography of Jane Austen this past weekend, and I was pleasantly surprised to find a description of the 1996 Jane Austen Society of North America AGM on the first page. I read the book when it was published in 2001, and while I remember liking the way Shields defends Austen against the charge that she ignored history and politics in her work and the way she analyzes what it meant for Austen to have “a public self after a life that had been austerely private,” I had forgotten many details, including the descriptions of JASNA and, for example, the fact that she refers to Austen’s Mr. Knightley as a “cold potato.” I wonder if that assessment of him has anything to do with the fact that she gave the name “Peter Knightly” to the man her heroine Fay McLeod no longer loves.

If you read last week’s blog post, you’ll know I attended this year’s JASNA AGM in Washington, DC. I started going to JASNA AGMs in 1999, so I wasn’t in Richmond, Virginia to hear the paper Carol Shields and Anne Giardini gave at the 1996 conference. But I think Shields’s description would apply equally to this year’s AGM: she says there is “no attempt to trivialize Jane Austen’s pronouncements and mockingly bring her into our contemporary midst. The gatherings are both gentle in approach and rigorous in scholarship.”

Back in May, I read Startle and Illuminate: Carol Shields on Writing, edited by Anne Giardini and Nicholas Giardini, and I was thinking of that book as well as The Republic of Love while I walked the paths of the labyrinth in the summer. “I saw that I could become a writer if I paid attention, if I was careful, if I observed the rules, and then, just as carefully, broke them,” Shields says. I like that advice a lot, and I like what she says about ignoring trends: “Think instead of the stories you like to read, or better yet, the story you would like to read but can’t find.”

I’ve been working on a novel for several years now, writing a story that I’d like to read but couldn’t find, and for the next month or so I’m planning to take a break from social media and blogging so I can focus on revisions. The manuscript is at about 125,000 words right now—I need to write some more and then cut quite a bit. For inspiration, I’m going to turn to Jane Austen, who gave her niece Anna this advice about revising her novel: “I hope when you have written a great deal more you will be equal to scratching out some of the past” (9 September 1814).

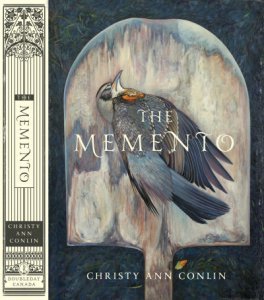

I’ll also be thinking of Shields’s words about how “creativity flourishes in tranquil settings,” and of advice from another Canadian novelist I admire, Christy Ann Conlin, who wrote a guest post here a few weeks ago about “The Sweet Exhilaration of Solitude” and the value of “slipp[ing] away from screens and social media.” I hear November is a good month for writing novels. See you again in December.

October 28, 2016

Jane Austen’s Emma in Washington, DC

The JASNA AGM in Washington, DC last weekend was absolutely wonderful. I enjoyed spending several days with JASNA members listening to presentations and participating in conversations about Jane Austen and her Emma. I’m grateful to everyone who helped organize “Emma at 200: ‘No One But Herself,’” especially Debra Roush and Linda Slothouber, Conference Coordinators.

On Thursday, Louise West and Mary Guyatt spoke about plans for “The 1817 Bicentenary in England” (Louise West, on the importance of Steventon and Chawton: “it was Hampshire that made Jane”); Sue Dell described the creation and preservation of the quilt sewn by Jane and Cassandra Austen and their mother; Deborah Charlton talked about the archaeological excavation of Steventon Rectory in a session on “Jane Austen’s Birthplace” and quoted James Edward Austen-Leigh, who said that “The most ordinary articles of domestic life are looked on with some interest, if they are brought to light after being long buried”; Gillian Dow gave a virtual tour of “Jane Austen’s Emma at 200: From English Village to Global Appeal” and spoke of Austen’s connections with the wider world through her brothers’ experiences (“although she didn’t travel much herself, she travelled through them”); and Jack Wang offered a behind-the-scenes look at the Cozy Classics board book adaptation of Emma and showed pictures of the felted figures he and his brother Holman created (“This strange alien creature is Mr. Elton before he got his head put on,” he said at one point. I wish I’d taken a picture of Mr. E.). At a luncheon/lecture/performance called “‘I must leave off being young’: Jane Austen in 1816,” Angela Barlow and Hazel Jones (presenting on behalf of Maggie Lane, who was unable to attend the AGM) highlighted the fact that Emma, unlike other Austen heroines, looks forward to what her life will be like when she reaches the age of 40 or 50.

On Thursday, Louise West and Mary Guyatt spoke about plans for “The 1817 Bicentenary in England” (Louise West, on the importance of Steventon and Chawton: “it was Hampshire that made Jane”); Sue Dell described the creation and preservation of the quilt sewn by Jane and Cassandra Austen and their mother; Deborah Charlton talked about the archaeological excavation of Steventon Rectory in a session on “Jane Austen’s Birthplace” and quoted James Edward Austen-Leigh, who said that “The most ordinary articles of domestic life are looked on with some interest, if they are brought to light after being long buried”; Gillian Dow gave a virtual tour of “Jane Austen’s Emma at 200: From English Village to Global Appeal” and spoke of Austen’s connections with the wider world through her brothers’ experiences (“although she didn’t travel much herself, she travelled through them”); and Jack Wang offered a behind-the-scenes look at the Cozy Classics board book adaptation of Emma and showed pictures of the felted figures he and his brother Holman created (“This strange alien creature is Mr. Elton before he got his head put on,” he said at one point. I wish I’d taken a picture of Mr. E.). At a luncheon/lecture/performance called “‘I must leave off being young’: Jane Austen in 1816,” Angela Barlow and Hazel Jones (presenting on behalf of Maggie Lane, who was unable to attend the AGM) highlighted the fact that Emma, unlike other Austen heroines, looks forward to what her life will be like when she reaches the age of 40 or 50.

And all of those sessions took place before the conference officially began on Friday afternoon, with Bharat Tandon’s plenary lecture on things that are hidden in plain sight in Emma. “Austen’s astonishing achievement in this novel,” he suggested, “is that fiction and reality each become the other’s visible world.” Susan Allen Ford paid close attention to Robert Martin and Harriet Smith in her plenary session on Saturday, and talked about how Mr. Martin’s “reading allows us to imagine an interior life for him.” At the closing session on Sunday, Juliette Wells described her research on the six surviving copies of the 1816 American edition of Emma (and talked about the annotations in the New York Society library copy, including “Mr. Knightley—tolerable,” “Emma—intolerable,” “Harriet—very pleasant,” and “El[ton]—d____d sneak”).

And all of those sessions took place before the conference officially began on Friday afternoon, with Bharat Tandon’s plenary lecture on things that are hidden in plain sight in Emma. “Austen’s astonishing achievement in this novel,” he suggested, “is that fiction and reality each become the other’s visible world.” Susan Allen Ford paid close attention to Robert Martin and Harriet Smith in her plenary session on Saturday, and talked about how Mr. Martin’s “reading allows us to imagine an interior life for him.” At the closing session on Sunday, Juliette Wells described her research on the six surviving copies of the 1816 American edition of Emma (and talked about the annotations in the New York Society library copy, including “Mr. Knightley—tolerable,” “Emma—intolerable,” “Harriet—very pleasant,” and “El[ton]—d____d sneak”).

The view from our hotel room

The top of the Washington Monument, as seen from our hotel room

I loved learning from Cheryl Kinney, Theresa Kenney, and Liz Philosophos Cooper about “Fictive Ills, Invalids, and Healers” in Emma and from Elaine Bander about “‘Liking’ Emma Woodhouse.” (Jane Austen famously said of Emma that she was going to take a heroine “whom no one but myself will much like.”) In my own session, I explored what it means that Emma is described as “faultless in spite of all her faults.” As always, with several breakout sessions scheduled at the same time, it was impossible to hear all of them, and I’m looking forward to reading about sessions I missed when JASNA’s journals Persuasions and Persuasions On-Line are published.

Perhaps some of you who were in Washington last weekend would be willing to comment on this post to share your experiences of the AGM. I missed out on several tours and events as well as breakout sessions. I found myself wishing I had bought a ticket for the candlelight tour of Mount Vernon, for example, and the “Illuminated Washington” tour, and I heard from several people that Friday’s “Salon Concert at Hartfield” by Ensemble Musica Humana was fabulous. (I didn’t have a ticket to the concert and that evening I watched the PBS documentary “Hamilton’s America,” which was also fabulous. No direct connection with Jane Austen—although the musical “Hamilton” is definitely about what it means to be ambitious, and, as many of you know, I’m very interested in the topic of Austen and ambition.)

I enjoyed catching up with the contributors to “Emma in the Snow” who attended the AGM, including Deborah Barnum, Carol Chernega, Gillian Dow, Susannah Fullerton, Theresa Kenney, Cheryl Kinney, Deborah Knuth Klenck, Dan Macey, Paul Savidge, Maggie Sullivan, Kim Wilson, and Deborah Yaffe, and several of us sat together at the banquet on Saturday. Mutton was not on the menu, but we did talk about the recipes Dan included in his wonderful guest post, “Discovering Mutton in Emma.”

I enjoyed catching up with the contributors to “Emma in the Snow” who attended the AGM, including Deborah Barnum, Carol Chernega, Gillian Dow, Susannah Fullerton, Theresa Kenney, Cheryl Kinney, Deborah Knuth Klenck, Dan Macey, Paul Savidge, Maggie Sullivan, Kim Wilson, and Deborah Yaffe, and several of us sat together at the banquet on Saturday. Mutton was not on the menu, but we did talk about the recipes Dan included in his wonderful guest post, “Discovering Mutton in Emma.”

I spent most of the weekend in the hotel, but I did get a few photos of Washington. Here’s what I saw on my early morning run on Thursday:

And here’s what I saw on the way back to the hotel after I visited “Will & Jane” at the Folger Shakespeare Library. I missed the curators’ talk by Janine Barchas and Kristina Straub on Wednesday evening, unfortunately, and it was great to have the chance to tour the exhibit on Friday morning (and then catch a ride on this shuttle bus).

The Folger Shakespeare Library

The United States Capitol

The Embassy of Canada

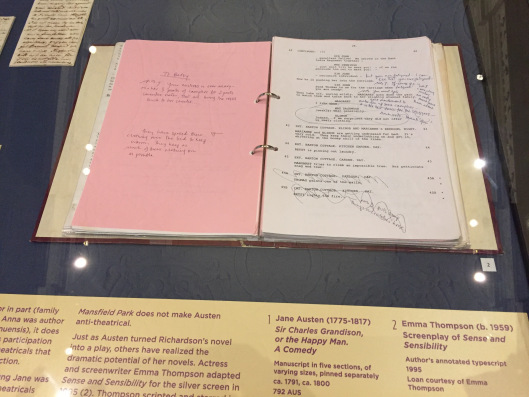

The exhibit includes the famous white shirt worn by Colin Firth as Mr. Darcy in the 1995 Pride and Prejudice mini-series—but that wasn’t my favourite part. (If you’re interested, you can read my thoughts on Mr. Darcy here: “Why is Mr. Darcy So Attractive?”) What I liked best about “Will & Jane” was the opportunity to think of Jane Austen as a playwright and/or an actor, and as the author of novels that continue to inspire others to write plays and screenplays and other creative works. The manuscript of the play “Sir Charles Grandison” was displayed alongside Emma Thompson’s screenplay for the 1995 film adaptation of Sense and Sensibility.

Screenplay of Sense and Sensibility

The manuscript of “Sir Charles Grandison,” on loan from Chawton House Library. “No manuscript of a complete Shakespeare play in his handwriting survives, but a play in Austen’s hand does…. While it remains uncertain whether Austen authored this adaptation in whole or in part … it does give us evidence of Austen’s participation in just the type of amateur theatricals that she seems to critique in her fiction.”

This year’s AGM has inspired me to read more about the Austen family’s interest in attending, writing, and performing in plays, to explore the various journeys undertaken by Jane and her siblings, to reread Emma yet again (this time paying more attention to what characters are reading and to what’s visible or invisible), and to continue to think about the ways in which Jane Austen’s life and writings inspire readers to create new works of their own, whether they—or rather, we—are writing essays or fiction or picture books or plays and screenplays, or designing and sewing quilts or period costumes. (I took a few photos of Janeites in costume at the Regency ball on Saturday evening, but they’re a bit blurry, so I won’t include them here. Someday I’ll stop relying on my iPhone for everything and invest in a camera so I can take better photos indoors.)

Reading about Austen’s legacy will be excellent preparation for next year’s JASNA AGM, “Jane Austen in Paradise,” in Huntington Beach, California, which focuses on “how Jane Austen has influenced literary and popular culture, and how she has been reimagined by succeeding generations of Austen scholars and enthusiasts in the 200 years of her ‘afterlife.’”

Reading about Austen’s legacy will be excellent preparation for next year’s JASNA AGM, “Jane Austen in Paradise,” in Huntington Beach, California, which focuses on “how Jane Austen has influenced literary and popular culture, and how she has been reimagined by succeeding generations of Austen scholars and enthusiasts in the 200 years of her ‘afterlife.’”

Next on my reading (and rereading) list, then: Jane Austen and the Theatre, by Paula Byrne; Jane Austen’s Journeys, by Hazel Jones; the Penguin edition of Emma, edited by Juliette Wells (I read Bharat Tandon’s beautifully illustrated Harvard University Press edition when I was preparing my talk for the AGM, but I haven’t read the new Penguin edition yet); The Joy of Jane: Thoughts on the First 200 Years of Austen’s Legacy (essays by Maggie Lane, Deirdre Le Faye, Susannah Fullerton, Ruth Williamson, Carrie Bebris, Emily Brand, Penelope Friday, Amy Patterson, Nigel Starck, Margaret Sullivan, and Kim Wilson), and Among the Janeites, by Deborah Yaffe, because I remember that Deborah talks about the ways in which Jane Austen inspires creativity in her readers.

Next on my reading (and rereading) list, then: Jane Austen and the Theatre, by Paula Byrne; Jane Austen’s Journeys, by Hazel Jones; the Penguin edition of Emma, edited by Juliette Wells (I read Bharat Tandon’s beautifully illustrated Harvard University Press edition when I was preparing my talk for the AGM, but I haven’t read the new Penguin edition yet); The Joy of Jane: Thoughts on the First 200 Years of Austen’s Legacy (essays by Maggie Lane, Deirdre Le Faye, Susannah Fullerton, Ruth Williamson, Carrie Bebris, Emily Brand, Penelope Friday, Amy Patterson, Nigel Starck, Margaret Sullivan, and Kim Wilson), and Among the Janeites, by Deborah Yaffe, because I remember that Deborah talks about the ways in which Jane Austen inspires creativity in her readers.

I’m also partway through rereading Jane Austen’s Letters, edited by Deirdre Le Faye, and I’m planning to read Persuasion again soon—along with Brian Southam’s Jane Austen and the Navy and Sheila Kindred’s essays on Charles and Francis Austen and the time they spent in Halifax, Nova Scotia—as I prepare to write two lectures for the June 2017 Jane Austen Society (UK) conference in Halifax. (Sheila and I will be giving a joint lecture on “Charles and Francis: Jane Austen’s Sailor Brothers on the Royal Navy’s North American Station” and I’ll also be speaking on “Anne Elliot’s Ambitions.”)

I suppose it shouldn’t surprise me that attending a conference devoted to Emma Woodhouse has inspired me to draw up an ambitious reading list….

I think I’ll begin by rereading the Cozy Classics Emma, which is just twelve words long.

October 21, 2016

A New Set of Caps

“You cannot let me go, my babies need me.” Kerry Sinanan has written a guest post about her experience of re-reading Jane Austen’s Emma a few months after she almost died after giving birth to her second daughter. She describes her return to consciousness, her recovery from this traumatic experience, and the connections she began to see between her own life and her research on maternal and newborn health in the eighteenth century. Reading Emma last December, she found herself focusing on Emma as a girl who had lost her mother, and she discovered a new appreciation for the chapter in which Mrs. Weston safely gives birth to baby Anna.

Kerry is currently a Visiting Fellow at the Moore Institute, National University of Ireland, Galway. She specializes in the literature and culture of the long eighteenth century and she has published on slavery and abolition and gender in the period. Her current projects include completing a book on slave masters and editing a collection of commissioned essays on Jane Austen to celebrate the bicentenaries of her novels.

On this opening day of the JASNA conference devoted to Emma (“Emma at 200: ‘No One But Herself’”), I’m pleased and honoured to introduce Kerry’s very moving guest post on the novel. Here’s a photo of her with her daughters in Galway.

For December 2015 I had organized two Jane Austen treats for myself: one was to attend a conference at Chawton House to celebrate the work of Marilyn Butler, “Marilyn Butler and the War of Ideas.” The other, which I’m sure many of you also planned, was to re-read Emma in the month of its bicentenary. I could not have foreseen how much my life context would inflect the experience of both of these when I planned them. I gave birth on 16th September, 2015 to a beautiful baby girl. As she was my second baby I had known that trying to write and present a conference paper during the first twelve weeks of a baby’s life was going to be a challenge! But the challenge turned out to be far greater than I imagined for, after having a relatively smooth home birth, I suffered a sudden and almost fatal postpartum haemorrhage, losing 3.2 litres of blood in less than an hour. Even in the midst of it I remember thinking that this was a very eighteenth-century thing for my body to do! I had not realized that this is, in fact, a terrifyingly common event today and the leading cause of maternal death worldwide. The World Health Organization states that “In Africa and Asia, where most maternal deaths occur, PPH accounts for more than 30% of all maternal deaths. The proportions of maternal deaths attributable to PPH vary considerably between developed and developing countries, suggesting that deaths from PPH are preventable.”

I am one of the lucky ones and was saved by rapid response paramedics, a large emergency team at the Central Delivery Suite of my local hospital, and the blood donors who supplied the blood for my transfusion. After returning to consciousness I looked into the eyes of the female paramedic who had brought me back. We recognized each other as she had been an English student of mine ten years ago! I said, “You cannot let me go, my babies need me”: it was my one thought. I was reunited with my newborn, held safely by her dad in my absence, just hours after the haemorrhage and we were able to breastfeed successfully (this is not always the case after PPH). We remained pretty much glued to each other for weeks after and she did not lose a single ounce from her birth weight. I wrote my paper for the conference with my baby sleeping in her stretchy sling. Her breathing and heart-beat, right beside my own, helped me to recover from the trauma of what had happened. Alongside the relief at our outcome was deep sorrow for the 127,000 mothers a year who die and for their children left behind because of postpartum haemorrhage. Two million deaths among mothers and newborns occur at the time of birth. Birth is still a high risk event in developing countries, and October is Infant Loss Awareness month. (Care #StealTheseStats).

After the birth, writing my conference paper on Pride and Prejudice and the research I was doing on maternal and newborn health were entirely separate areas for me until I went to Professor Isobel Armstrong’s paper, “Illegitimacy and the Haunting of Jane Austen’s Novels.” She began with a reading of the first paragraphs of the novel and paid particular attention to the wonderful last sentence that upsets the apparently blithe tone:

Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable home and happy disposition, seemed to unite some of the best blessings of existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in the world with very little to distress or vex her.

She was the youngest of the two daughters of a most affectionate, indulgent father, and had, in consequence of her sister’s marriage, been mistress of his house from a very early period. Her mother had died too long ago for her to have more than an indistinct remembrance of her caresses, and her place had been supplied by an excellent woman as governess, who had fallen little short of a mother in affection. (Emma, Volume 1, Chapter 1)

Professor Armstrong asked us whose voice this was and emphasized the sibilant “s” sounds running throughout the last sentence. The word “caresses” brings to our imagination the tender and intimate whispers, breaths and touches between mother and child, sounds that had been part of my life for the last twelve weeks. As I listened I felt that Emma’s “indistinct remembrance” of this intimacy would make it something to be yearned for because of its bare tangibility. I imagined Emma as having a trace of a memory of irreplaceable love. In my barely-recovered state, it was all I could do not to burst into tears at the thought of my own little ones almost losing me. George Justice, in his blog post for the series Emma in the Snow, has written movingly about this sentence and, based on his own memory of losing his mother in childhood, concludes, “Emma must have been seven or younger when her mother died” (“Mrs. Woodhouse”). Put in this way, we see Emma’s loss as an enormous trauma for a very young child to have suffered, one with lasting effects.

After the conference I returned to my Christmas re-reading of Emma with a new perspective; given that I had almost left my own newborn and her sister motherless, my over-riding view of Emma now was of a child who had lost her mother. Like my own baby, she was “the youngest of two daughters” and I kept pondering how the opening sentences in fact emphasize this motherlessness, and how Emma is put in a position of responsibility from a young age. This mother is replaced, we are told, by a swift shift in tone created by the clichéd description of Miss Taylor as an “excellent woman.” This is sharp and brisk, halting any moment of indulgence for Emma. The irony of the last words became freshly apparent to me for Miss Taylor falls “little short of a mother in affection.” Emma should not complain! My sense of Emma now was of a young girl who has not been permitted to grieve for she has so many “blessings.” It is true that she and Miss Taylor do love each other but, crucially, with “the intimacy of sisters” (Volume 1, Chapter 1). Emma has a memory of a lost mother who can never be replaced but is obedient to the community around her in feeling herself blessed.

And so, when I came to the account of Mrs. Weston’s own maternity—“Mrs. Weston’s friends were all made happy by her safety” (Emma, Volume 3, Chapter 53)—I felt, anew, the power of Austen’s under-statement. This simple sentence glides over the reality that giving birth is a serious risk and the predominant feeling of Mrs. Weston’s family and friends is anxiety, for she and her baby may not survive. Maternal deaths, as we know, were part of life in the period with approximately 90 out of 10,000 women dying in childbirth (Robert Woods, Death before Birth: Fetal Health and Mortality in Historical Perspective). Infant mortality rates were even higher but evidence shows that fewer babies died as mothers were encouraged to breastfeed in the eighteenth century. The commonplace way in which Emma and her circle must bear with their fears for Mrs. Weston and her baby was shared by Austen and her family. Upon the birth of her nephew, Austen writes to Cassandra, “I have just received a note from James to say that Mary was brought to bed last night, at eleven o’clock, of a fine little boy, and that everything is going on very well. My mother had desired to know nothing of it before it should be all over . . .” (18 November 1798). Austen’s mother indeed knew the risks and could not bear the anxiety of waiting through the birth.

Our narrator subtly tells us that the birth of this baby girl gives Emma an opportunity to heal from grief for her lost mother as she happily imagines the life the child will have with its mother, one without separation. “She had been decided in wishing for a Miss Weston” for a daughter is “never banished from home; and Mrs Weston—no one could doubt that a daughter would be most to her” (Volume 3, Chapter 53). And as the news of Emma’s engagement to Mr. Knightley is made known, the chapter stresses the togetherness and unity of family:

It was a union of the highest promise of felicity in itself, and without one real, rational difficulty to oppose or delay it.

Mrs. Weston, with her baby on her knee, indulging in such reflections as these, was one of the happiest women in the world. If any thing could increase her delight, it was perceiving that the baby would soon have outgrown its first set of caps. (Volume 3, Chapter 53)

I see mother and child nursing here with Mrs. Weston cradling her baby’s head as she supports her. The beauty of this everyday moment belies the seriousness that gives rise to it: Mrs. Weston can see that her baby is growing and thriving and will indeed need its next set of caps. She is there to fit them on her.

Quotations are from the Penguin edition of Emma, edited and with an introduction by Juliette Wells (2015), and the Oxford edition of Jane Austen’s Letters, edited by Deirdre Le Faye (4th edition, 2011).

October 14, 2016

Listening Carefully and Watching Intently

I spent part of the Canadian Thanksgiving weekend in Mahone Bay and Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, reading, writing, and taking pictures. (And buying books, at two wonderful independent bookstores, The Biscuit Eater in Mahone Bay and Lexicon Books in Lunenburg….) Here’s what Mahone Bay looked like on Sunday afternoon.

I hadn’t been there since last December, when I took this picture of the calm water and the pale pink sky.

When I got home, I read Sandra Barry’s poem “Thanksgiving,” which is a meditation on grief and hope, and I was struck by the beauty and simplicity of these lines in the last stanza:

I promise I will listen

carefully; I will watch

intently.

All through 2016, Sandra has been sending a poem a week to her subscribers via email, and I always look forward to reading her work. She’s the author of Elizabeth Bishop: Nova Scotia’s “Home-Made” Poet, and she writes about Bishop at the Elizabeth Bishop Centenary blog. (If you’re interested in subscribing to Sandra’s Monday morning poems, let me know in the comments below and I’ll put you in touch with her.)

Sandra’s words about listening and watching have echoed in my mind ever since I first read them, and I know I’ll continue to think of her poem as I listen and read and watch and attempt to capture what I’m thinking about or looking at, whether through writing or photography.

A few photos of Lunenburg:

And I’ll conclude by quoting Sandra again, this time from one of her emails: “We so desperately need to see, capture, express the beauty of this deeply troubled world—it is one important way to keep active the good energy, to balance out the darker stuff that seems legion.”

All photos © Sarah Emsley, 2016.

October 7, 2016

On Not Skipping from September to November

Inspired by Christy Ann Conlin’s guest post on “The Sweet Exhilaration of Solitude,” I spent some time in the Halifax Public Gardens on Wednesday morning, admiring the flowers and the sunlight and shadows and taking a few photos. Inspired by the first post at Shawna Lemay’s new blog, “Transactions with Beauty,” in which she says, “As often as I find beauty, I want to send beauty out into the world, too,” I’d like to share these beautiful dahlias here.

Last October, I took hundreds of dahlia photos, some of which I included in this blog post I wrote about “L.M. Montgomery and the Halifax Public Gardens” (“She’ll feel awful bad if her flowers get frosted, especially them dahlias. Octavia sets such store by her dahlias.” From Montgomery’s 1914 short story “Bessie’s Doll.”)

This year, partly because of Christy Ann’s words about the value of “slipp[ing] away from screens and social media,” I decided not to write a long blog post about dahlias. Instead, after I share these photos with you, I’m going to return to the two main writing projects I’m working on this fall: the first is a novel (which I started several years ago and am currently revising), and the second is a lecture on Jane Austen’s Emma Woodhouse, “faultless in spite of all her faults,” for the Jane Austen Society of North America AGM in Washington, DC, later this month.

The bandstand in the Public Gardens

Another view of the bandstand in the Public Gardens. From this perspective, you can see that the gardeners are in the process of getting ready to plant spring bulbs.

Nova Scotia is lovely at this time of year. So is Prince Edward Island, which I visited in early October last year, when I was reading Montgomery’s Anne of Ingleside. Like Anne Shirley, I’m “so glad I live in a world where there are Octobers,” and I agree that “It would be terrible if we just skipped from September to November” (Anne of Green Gables, Chapter 16).

I’m going to slip away from the screen today, and go outside to walk or run and appreciate the glorious October weather while it lasts. And when I come back in, instead of checking email or working on the computer, I’m going to pick up a stack of manuscript pages and a pen and revise what I wrote yesterday.

All photos © Sarah Emsley, 2016.

September 30, 2016

The Sweet Exhilaration of Solitude

It’s a pleasure to share this guest post from Christy Ann Conlin, who drew inspiration from two of Nova Scotia’s most beautiful museums, Prescott House and Uniacke House, when she created a grand estate named “Petal’s End” in her new novel, The Memento . For a long time, Petal’s End has been “just a big empty house and sprawling grounds, waiting for a party that never started, for guests that never arrived, a family who was missing,” but at the beginning of the novel Fancy Mosher, the twelve-year-old narrator who has a summer job at the estate, says “There is much to do, what with the rumour Lady Marigold Parker is finally coming back.”

Fancy and the other members of the household staff know little about what to expect that summer—though they do know that the Parker women are fighting with each other—but Fancy and her friend Art are excited about the idea that “Petal’s End might come back to life, alive again with all them stories we’d grown up on, the parties and the exotic visitors from all over creation.” Lynn Coady calls The Memento “Lovely and sinister … a gorgeous unveiling of the relentless darkness that awaits beneath the pristine, orderly beauties we so painstakingly impose.”

Christy Ann’s first novel, Heave, was a Globe and Mail “Top 100” book and a finalist for the Amazon.ca First Novel Award in 2003. She teaches in the University of Toronto School of Continuing Studies online Creative Writing program and she lives in Wolfville, Nova Scotia, not far from Prescott House. She’s currently working on two novels and a short fiction collection, and this weekend she’ll be at the Cabot Trail Writers Festival in Cape Breton to read from The Memento and teach a writing workshop. Later this fall, she’s doing two graveyard readings by candlelight, one at the Annapolis Royal Ghost Town Festival on October 21st and one at the Anglican church in Wolfville on All Souls’ Day, November 2nd.

A couple of weeks ago, Christy Ann and I spent an afternoon in the Prescott House garden, talking about books and writing and our shared interest in novels by Jane Austen and Edith Wharton. It was the perfect way to spend one of the last days of the summer. Here’s one of the photos I took that afternoon.

I wrote a little bit about the history of Prescott House a few years ago, after our local Jane Austen Society of North America group gathered there for iced tea and a discussion of Kim Wilson’s book In the Garden with Jane Austen. (For more photos of the house, including a postcard from the 1980s, when the house was covered in ivy and looked very different, see “Flowers are great, but frogs are even better…”). And I wrote a short post about Uniacke House and Lake Martha six years ago, not long after I started this blog.

While I’m on the topic of JASNA Nova Scotia meetings, I also want to mention—for those of you in the Halifax area—that Claire Bellanti, President of JASNA, is in town this weekend and she’ll be giving a talk at Dalhousie University this afternoon, entitled “‘You Can Get a Parasol at Whitby’s’: Circulating Libraries in Jane Austen’s Time” (3:45pm at the McCain Arts and Social Sciences Building, Room 1198). She’ll also be speaking at our wonderful new Central Library on Sunday at 2pm in Room 301, and the title of her talk is “Who Is Jane Austen?”

I’m delighted to introduce Christy Ann’s guest post on the value of solitude and stillness, beautifully illustrated by photos from her visits to both Prescott House and Uniacke House earlier in the summer.

Barefoot on the verandah of Uniacke House Estate in Mount Uniacke, Nova Scotia. This country home, with parkland and lake, is a provincial museum. I’ve visited here since I was a child and this Georgian manor was part of the inspiration for Petal’s End in The Memento. When the province bought the estate (1000 acres of land, much of it open to the public with walking trails) it came complete with the all the original furnishings, artwork, books, and china!

We are in such a hectic century. This summer was dizzying one for me, and even when I was on a beach or some such place, work never seemed to end. The outside world was always creeping in as it does for so many of us, through a phone screen. So quite suddenly, I slipped away from screens and social media.

It has been a sweet elixir for my soul, I have to say, stepping back into a quieter and more old-fashioned pace. I swam in the river and read books and strolled through gardens, and visited some of my favourite old manor homes.

Vintage hair comb at Uniacke House

Fainting couch in lady’s bedroom at Uniacke House

Looking through to the nursery at Uniacke House

Walking through the windy meadow… Is that Heathcliff calling? My “Cathy” moment.

And back to the 21st century, facing my darling husband/photographer!