Geraldine DeRuiter's Blog, page 12

January 3, 2018

The World’s Oldest Bookstore: Livraria Bertrand, Lisbon, Portugal

Lisbon is full of bookstores. They are everywhere, tucked into odd-shaped nooks so that they almost blend in with the facades. Some were ancient, and so resembled museum exhibits that I simply stared at them from afar, not realizing that we could actually go inside.

This was my initial reaction to Livraria Bertrand – the oldest operating bookshop in the world, established in 1732. I looked at it from a distance, through glass, and thought “how remarkable”, the way one would any other work of art. You marvel at it, but you do not touch. You certainly don’t step inside. But Rand was not limited by such strange hangups, and seeing that he was able to walk in without being yelled at by some unseen authority figure, I quickly rushed in after him.

[image error]

Plus he’s super cute and his eyes are like, CRAZY twinkly.

[image error]

The Bertrand smells faintly of old wood and vanilla. Sloping archways connect room after room after room. The inner rooms look modern and recently renovated, but every now and then there is a pillar, or an exposed stone, or a strangely uneven piece of floor to remind you that when this shop opened, humans thought our solar system ended at Saturn.

[image error]

Pedro Faure – one of many French booksellers who began arriving in Portugal in the early 18th century – opened the shop in 1732, but it was destroyed in the earthquake of 1755 (which decimated much of the city). The shop was reopened not long afterward in its current location, and has remained in operation ever since, hosting poets, philosophers, Nobel prize nominees, artists, and, of course, writers.

[image error]

It was enough to wander through and simply breathe it in. It was as quiet as church, and for a lapsed Catholic like myself it offered even more of a religious experience that any of the cathedrals we visited. If there is a God, she is here, in the pages of a really good book.

[image error]

I’ve always enjoyed novels that are love letters to books themselves (Like Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore or The Borrower, which are both delightful reads), and Lisbon feels like the city equivalent of that – an entire town made of tiny shops piled high with dusty tomes. In this respect, Livraria Bertrand is not unique – it is one of many, many bookstores. But it is the oldest, and there is a sort of ancient magic in its walls. You feel like you might round a corner and find yourself someplace wondrous. And then you realize – that was true the second you stepped in the door.

January 1, 2018

Hello. Goodbye.

Hello.

I am back. At least, I’m telling myself that I am back. I am committing, under the binding oath of the internet (my hand firmly placed on a laptop open to reddit’s homepage as I swear this to you) to try to blog again this year. Do you hear that, internet? I AM GOING TO TRY.

(Please, no one point out that trying is like, the most non-committal of all the promises).

Ask me why I stopped blogging, and I’ll tell you I didn’t mean to, while simultaneously offering up a dozen excuses. I stopped because I was tired, because I was swamped with the book, because I missed my dad, because blogging literally hurts. The last two years have had me tweaking “my brain medicines”, trying to figure out what works and what doesn’t. Most things, I’ve found, don’t work. Sitting at my computer for more than a half an hour equates to a major headache.

But I miss writing. I miss this weird site and this weird community that we made together.

It’s strange to jump in again, to try and pick up the story where we left off. I don’t remember where we were. I don’t remember what trip I last told you about. So I will simply tell you about the day before yesterday. That was when I found out that Chad died.

I’d written about Chad before – both on this blog and in my book. Around the time I had brain surgery, Chad did as well, but his diagnosis was for glioblastoma multiforme – a nasty form of brain cancer that Chad discouraged people from Googling because (in his words) “all you’re going to find is depressing survival rates of 3 to 4 minutes.” (Chad was funnier than me.)

He went on to have five more brain surgeries, which he documented on his wonderful blog.

Chad was instrumental in helping me finish my manuscript for All Over the Place. I’d been feeling uninspired, so I’d hired a career coach. She told me that since I wasn’t internally motivated (I won’t change out of pajamas unless I’m going to see another human being, and even then I might not) I needed to enlist someone else who I was accountable to, to help me finish my book.

I enlisted Chad. Every month for a year, I sent him a chapter of my book. He joked that I’d asked him to do it because I was planning on him dying and that way I could procrastinate forever. Then he made a terrible pun about deadlines.

Our emails ebbed and flowed. Sometimes we’d send several back and forth in a day, sometimes one of us (almost always me) would fall off the planet for weeks or months.

He’d lived with glioblastoma for five years. During that time he wrote a musical about cancer, started a non-profit, and enjoyed himself to the point of “curing” his illness (if only for a little while).

The last email I sent him was in March of last year. Part of me figured I had the luxury that we have with so many relationships – to dip in and out of them over the span of a lifetime, assuming they’ll be there when we need them. Part of me was was easing myself out of our friendship, slowly backing away from a dying man, because it’s easier to lose an acquaintance than a friend. I know. I know. It’s a shitty thing to do.

Aware of how awful and cowardly I was being, I finally texted Chad a few days ago. A text came back, and just a few words in, I could tell it wasn’t him. A family member graciously apologized to me and broke the news, but by then I already knew he was gone. He’d had a severe seizure and died a few weeks earlier.

We didn’t spend that much time together. We’d hung out in person once, back in 2015. The only photos I have of the two of us are two ridiculous, grainy images taken with my cell phone during that trip down to L.A.

I had other pictures and texts from him, but I lost them when I got a new phone. So now I just have his emails, these two photos, and his blog, which I keep returning to.

I’m left with regret. I’m always left with regret. I should have written to Chad more. I should have written to my father more. I should write more. I should tell the people I love that I love them more.

We don’t have an infinite amount of time on this planet. Chad was acutely aware of this. He spent his time creating – through headaches, through seizures, through cancer. He even helped me create. He reminded me to “stop and smell the fucking roses” and to appreciate just being alive. He reminded me that every damn day is a gift. Every damn day is chance to make something wonderful.

So I’m going to try to spend more time doing that.

Goodbye, my friend. I’ll miss you.

And hello, my friends. It’s nice to see you all again.

December 12, 2017

The Walker Art Center and Sculpture Garden, Minneapolis, Minnesota

I was in Minnesota for only a moment – I’d been invited to speak at the Rain Taxi book festival on a panel with some delightful people, and despite the brevity of the trip, I still found myself with an afternoon free to roam the city.

I asked the internet how I should spend my time, and the recommendations were all the same: go to the Walker Art Center and Sculpture Garden.

Endeavoring to write about art, I am met with the same hesitation that I always feel – it is, to paraphrase some brilliant uncredited soul, like dancing about architecture. I won’t dwell too much on the individual pieces at the Walker – by the time you visit, they will have changed, anyway. I will simply tell you to go, because the space is wonderful and the collection will make you feel alternately contemplative and sad and angry and joyous, and all sorts of permutations of those things.

[image error]

I must have been in a romantic mood on the day I visited, because everything was heartbreakingly beautiful to me. When I showed this photo to Rand, I commented on how sweet and sad the sentiment was.

[image error]

He nodded.

“You know it’s surrounded by butts, right?”

No. I did not.

Oops.

[image error]

If it is rainy or cold or snowing, then you might want to simply stay inside the Walker, but if the weather is slightly more amenable, then consider wandering around the sculpture garden.

The collection is a little more permanent, because it is much harder to move a giant blue chicken than it is to, say, move a painting.

[image error]

[image error]

Admission to the Walker is only $15, which feels modest compared to many galleries in the U.S., but the sculpture park is free, since it’s remarkably difficult to put giant things outside and then somehow demand that people pay to look at them.

[image error]

There were a few pieces that didn’t entirely resonate with me, though I’d like to think that I understood their message. For example, this sphere clearly has a vagina.

[image error]

(Right? I mean, that’s clearly what’s going on here.)

My favorite pieces were these paranoid stone benches. It’s like someone heard my thoughts and then engraved them onto a huge slab of granite.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

Minneapolis is underrated; a few short hours there won’t feel like enough. But even if your time there is fleeting, the Walker is worth it, if only so you can return home and say to your beloved, “I found a bench that understood me more than most people do.”

December 8, 2017

Bar Luce: A Wes Anderson Designed Cafe in Milan, Italy

I am not the first to discover Bar Luce. Designed by filmmaker Wes Anderson, it opened in 2015 and I did not learn of its existence until 2017, which is a lifetime in the world of the hip and the trendy. It sits on the outskirts of Milan, crowded with flawlessly beautiful and bored looking women and men who have already grown tired of things you have never heard of. By the time I went, it was old news, I suppose. But it was new to me.

I have simultaneous loved Anderson’s work and resented it; it resonates with me in a way that feels like I’m somehow being manipulated. When The Royal Tenenbaums came out, my brother called me and we had one of those sparse exchanges that can only take place between people who have known each other their entire lives. He asked if I had seen it. Yes, I told him.

“Royal,” he said.

“I know.”

“Dad,” he said.

“I know.”

2009. One of my all-time favorite photos of my father, in which he manages to look pissed off while eating ice cream.

Therein lies Anderson’s brilliance – he creates characters who are often miserable and yet they are fine. Things are simultaneously bad and okay. That is a world I know.

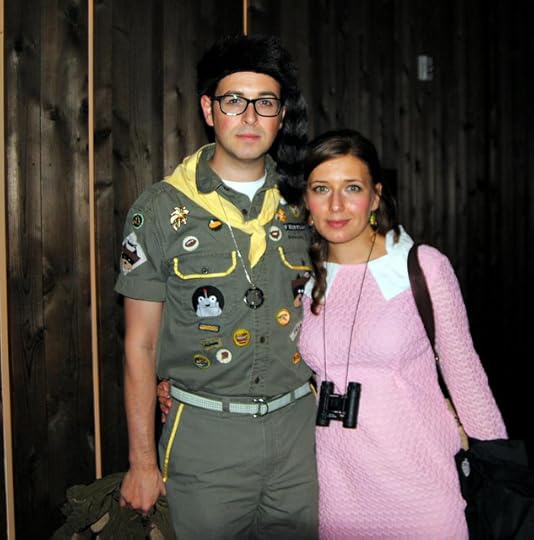

I was angry that Anderson could pinpoint me – and so many others – so well. I’d like to think I was less predictable than that. My response was reactionary – I tried to resist his work. As years of Halloween costumes attest, this endeavor has not been successful.

Sam and Suzy from Moonrise Kingdom.

–

Steve Zissou and Margot Tenenbaum.

Rand tried to keep our visit a surprise, but I eventually learned of it. He asked me if I want to see photos beforehand, but in the same way that I refuse to watch trailers for Anderson’s films before they are released, I shook my head.

“I want to see it for the first time in person,” I told him.

A small part of me didn’t want to go, scared it wouldn’t live up to my expectations. Or that it would, and that the world then would seem dull by comparison.

The bar was on the edge of town, a 15-minute drive even from the Duomo at Milan’s center. We took a cab, and found ourselves in a industrial district, full of long white buildings and factories. Bar Luce resides in one of these, the only indication of its existence is a small neon sign along the front that reads “BAR.”

As we walked in I imagined that I could see us from afar, moving in-slow motion as music played.

My biggest grievance about the worlds Wes Anderson created was that they existed only on the screen, and I could never step into them. Even when I paid a pilgrimage to the house from The Royal Tenenbaums (up in Harlem), I could only stand at the curb and stare, the delta between his work and reality feeling bigger than it ever had.

I thought Bar Luce would change that. Alas.

Every piece of it has been crafted by Anderson. It is perfect execution of his vision, but it is not perfect – his work never is. Pants hemmed too short, rusted out cars, a penciled in mustache – there is always something intentionally amiss.

Above a sea of terrazzo, there are islands of Formica the color of Easter eggs.

[image error]

The shelves behind the bar and the glass dessert cases look like they’re filled with props.

[image error]

[image error]

But the cake was real, and I couldn’t really ask for more than that.

The cafe was empty when we arrived, and the staff looked like they were suffering from a terminal case of ennui. We were unaware of the rush of people that would soon come through the doors, and so the sheer number of waiters and baristas looked excessive.

[image error]

We sat down and ordered. I scanned the menu for a butterscotch sundae, eager to placing my order in heavy, bored Italian, but there wasn’t one. Instead, I got The Royal, a sandwich made with culatello, and literally nothing else.

[image error]

This is the cafe’s signature cake – vanilla pan de spagna with a light chocolate cream and covered in pink fondant.

[image error]

[image error]

Supposedly Rand ordered it.

[image error]

[image error]

(He didn’t get to eat most of it.)

At some point I demanded that we abandon our lives back in Seattle and move to Milan and, specifically, to Bar Luce.

“We can’t; we just bought a house,” Rand said.

“Let’s sell our house.”

“No.”

“Please?”

“YOU ARE THE ONE WHO ASKED ME TO BUY YOU A HOUSE.”

“And now I’m asking you to sell it so we can move to Milan. Please?”

“No.”

“But it takes so little to make me happy.”

“That is patently untrue and you know it.”

He was right. But for a few fleeting moments, I was excessively happy, in a way that Wes Anderson’s characters never are. I endeavored to hide my delight from everyone because it felt thematically off.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

Once again, I was not successful.

[image error]

Along the back wall of the cafe sits a jukebox that mostly had Italian songs from the 1950s and 60s. It had a bunch of Rita Pavone, but no tracks that I was familiar with. So the songs were obscure even if you were familiar with the obscure genre.

[image error]

Next to the jukebox was a pair of pinball machines.

[image error]

Rand got up to play one of them, and came back to the table, his eyes wide.

“It only takes lira,” he said.

We laughed.

“I’m not kidding.” (100 lira coins are available from the counter – 4 for a Euro.)

[image error]

[image error]

This superfluous detail stuck was exactly what I had hoped I would find here. These little elements serve no other purpose than to you bring you into Anderson’s world. We met every little idiosyncrasy with, “Well, of course.”

[image error]

This pinball machines features Jason Schwartzman. The other one had Bill Murray on it. Because of course they do.

At times it became hard to shake a feeling that this wasn’t a cafe designed by Wes Anderson, but rather what fans imagine a cafe designed by Wes Anderson would look like. It gave me everything I wanted and more, right down to the meticulously designed bathrooms.

[image error]

[image error]

But in doing so, it almost felt as though it bordered on parody. In Shakespeare’s Cymbeline, which is often thought to be the bard poking fun at his own tropes, every single Shakespearean cliche is thrown at the audience: lost princesses disguising themselves as boys, buffoonish villains, an exodus into the forest. It’s an absolutely ridiculous play because it is so over-the-top Shakespearean.

Bar Luce had that same sort of feel. It feels like almost too much from a director who plays in subtlety and nuance (right up until somebody snaps and crashes their car into the house). Maybe that’s the problem. Bare Luce exists. And so it can never truly be a part of Wes Anderson’s world because it is a part of ours. We have cell phones and credit cards and top 40 songs that we all hate but still know the lyrics to. We do not walk in slow-motion. Alec Baldwin does not narrate our story.

I say this not to disparage Bar Luce – I loved it, and our visit. But as a devout Wes Anderson fan, it brought up a bit of an existential crisis: I’d always wanted to step into Anderson’s cinematic universe, not realizing that part of the magic lay in the fact that I couldn’t.

November 7, 2017

The Monkeys of Gibraltar

Note: We were in Spain last spring, but work on the book meant that I haven’t gotten around to blogging about a lot of the places we visited. In keeping with the better-late-than-never mindset that characterizes much of my life, I’m finally writing about some of the strange and wonderful things we saw. If you want to read more about this trip, check out the posts here that are from 2016.

There are many things that I should tell you about Gibraltar. It’s a strange place: it’s a territory of the U.K., but it’s literally attached to Spain. The Spanish want it back, but the Gibraltarians are pretty happy being subjects of Queen. In a recent vote, less than 1% of the population wanted to return to Spanish rule. It all goes back to the 1700s and the Treaty of Utrecht where the Spanish ceded Gibraltar to the British and I will get to all of that in another post BUT FIRST MONKEYS.

Yes, monkeys.

Another thing that’s all over Gibraltar? Signs telling you not to feed the monkeys. There are even drawings which illustrate, rather graphically, what will happen if you feed the monkeys. The food can be harmful to them, and it makes them both far too trusting of and aggressive towards humans. The point is, feeding the monkeys is bad for everyone.

So guess what a bunch of people do the second they see a monkey in Gibraltar?

THEY FEED THE DAMN THINGS.

As you walk around Gibraltar (which is, as the Prudential logo promises, a giant monolith extending out from the sea) you will see a lot of monkeys. There are about 160 Barbary Macaques living on the rock. They are sometimes called “Barbary Apes” because they don’t have tails (they are still monkeys, though). They greet you almost immediately upon your arrival, and the entire experience is a bit startling – you are high up on the rock of Gibraltar, the views are dizzying, and there are monkeys.

[image error]

They are fat and seem quite content provided you don’t get too close to them. That’s usually pretty easy except sometimes you’ll be walking down a path and there’s just a monkey just sitting there.

[image error]

[image error]

You suddenly hear the Clint Eastwood western showdown music in your head. Conceptually monkeys are like the coolest thing ever but when you actually see a live, wild one in close proximity to you, it’s quite unsettling. They have sharp teeth and are profoundly strong, yet there is something uncannily human about their appearance, and all of that is just a little bit terrifying.

Our friend Rob, and the monkey that wasn’t quite on his back.

Given enough time, though, and things cease to seem all that strange. This massive rock, sticking straight out of the ocean doesn’t seem that odd. The views cease to be so dizzying.

And the locals become a little less scary.

[image error]

(But you still shouldn’t feed them.)

October 25, 2017

Yellow Invisalign, Floor M&Ms, and Why the Neighbors Hate Us.

After 7 years of living in the same quirky little corner of Seattle, Rand and I moved across town to a bigger place in a smaller neighborhood. One would think, after literally years spent at careers that requires us to constantly move from one place to another, we would be pretty good at it.

We are not.

At one point, Rand found a Tupperware of cooked chicken in a cabinet. Because that is where I had put it. But the cabinet is right next to the fridge, so I think I get points for proximity. Rand disagrees.

Yesterday, I’d decided to organize the kitchen. I bought adorable plastic containers to display my baking ingredients, and poured a bunch of M&Ms into one. I’d put the lid on top, but I’d apparently failed to dry it properly, because a few drops of water leaked onto the M&Ms. Panicked, I isolated the wet M&Ms, and found another container to pour the dry ones into. But because the entire process was noisy and Rand was on a call, so I went outside to transfer the M&Ms and a bunch fell on the deck. But the deck is pretty clean, so I started picking them up and eating them without realizing it.

It was 9am. I was in my pjs. I’m pretty sure the neighbors saw.

And while my offenses resulted in me having to throw out chicken and eat floor M&Ms, I feel like his crime – which involved him taking my alphabetized books and re-organizing them by color – was grounds for divorce. I came home to this.

[image error]

WHERE DO THE BOOKS WITH WHITE SPINES, GO, HUH, RAND?

This is so many levels of bullshit I don’t even know where to begin. I stared at it, mouth agape, before finally whispering, “Why would you do this? Why would anyone do this?” And Rand said, “Oh, I’m not done yet” and I screamed “NO YOU ARE SO DONE.”

It’s been a week. The books are still arranged by color. I now avoid that room. And speaking of color, I somehow dyed the inside of my purse neon yellow.

I don’t know how this happened. Over the last few days, I’d noticed that my hands would occasionally be stained yellow, but I’m the sort of person who puts chicken in the cabinet, so I just sort of rolled with the yellow hands thing.

And then the yellow started to spread, and I couldn’t find the source, and it was everywhere, and I started to panic, because what if it was jaundice? Which I know doesn’t work like that, but it is hard to be reasonable when your husband organizes your fucking home library by color.

So then I reached into my purse to pull out my Invisalign tray and the whole goddamn thing was highlighter yellow. It’s my last tray, which means that instead of getting a new one in a few days, I have to wear it for a month.

[image error]

Everything I do is terrible.

This, combined with the fact that we’re using cardboard to cover our bedroom windows until our blinds come in, and the whole eating M&Ms off the back deck mean that the neighbors have stopped talking to us entirely. Rand is delighted about this development.

[image error]

Here he is thanking me for alienating the neighbors. The pile of papers behind me is my inbox or something.

[image error]

This photo becomes decidedly less cute when you see my teeth.

Anyway, I called my orthodontist and they can’t stop laughing. I look deranged.

[image error]

The moral of the story: don’t dye your invisalign yellow and don’t put chicken in the cabinet and don’t organize your books by color and never move.

Floor M&Ms are fine.

October 5, 2017

I Have Written About Currywurst, My Love.

“You never wrote about the curry plane.”

“The … the curry plane?”

He nods, pouting. I am confused.

“Like, a plane of existence that consists of … curry?” I ask, hoping for clarification.

He is annoyed.

“The curry plane.”

“The curry plain,” I say, nodding, having no idea to what he is referring. “… a spacious expanse filled with curry.”

“The plane in Munich airport.”

“Yes. There are many planes in Munich Airport.”

“There is one that serves curry.”

I finally understand what he’s talking about.

“You’re mad at me because – ”

“You never wrote about the curry.”

There is more to it, of course. The curry post – or lack thereof – was the line of demarcation for Rand. For him, it marked where I stopped blogging regularly about our travels. He is wrong – not about my failure to blog regularly (that is a fact I can’t dispute) but that there is a clear line as to when that began. They are stories I failed to tell that took place before the curry plane, there are plenty that I’ve written about that happened after. But when life changes, we often attach meaning to an event or to a place. Here, we say. All that is different in our world began here.

I do this, too. The line I drew before and after my brain surgery, before and after my father’s death. The world hurls us all forward, and the space between me and those moments becomes bigger. I cannot change those things. But I can tell you about the curry plane. Maybe, for a little while, I can stop time.

In a wide courtyard in Munich Airport – my husband’s favorite in perhaps all the world – sits a WWII-era American bomber that bears a smiling pilot logo and the name “Smokey Joe’s.” This seems an odd era for the Germans to fetishize.

But the plane is not a plane. It is a food truck. It serves only one thing, a dish that is decidedly non-American in origins: currywurst.

The name of this food repulses me. I react to it viscerally, the way I do when men on the street tell me to smile, because I’d be so much prettier if I did. Wurst should not be part of the lexicon. I will not make a pun here. It doesn’t deserve it.

But despite the name, despite the appearance, despite its raw components … currywurst is not bad. Indeed, given the right circumstances, currywurst might be great. When you are drunk and hungry, it is there. When you are tired, and jetlagged, and you’ve just left Italy after perhaps committing rental car fraud, currywurst is perfect.

It is ubiquitous across Germany, tracing its origins back to a post-war Berlin, where a resourceful housewife supposedly traded booze to British soldiers in exchange for ketchup. She poured it over sliced pork sausage and sprinkled curry powder over the top. It spread like wildsausage over the country. It transcended social strata. It is said to be beloved by construction workers and Angela Merkel alike.

It became the quintessential German fast food without ever truly becoming fast food. Out of a WWII era bomber in the middle of Munich Airport, it is served in a paper boat with tiny wooden forks.

For years, I resisted this snack. Rand would threaten me with it and I would scream. I don’t like sauces, or messy foods, or meals that make you feel like you need a shower afterwards. Currywurst seemed a trifecta of evil. I was horrified. I swore I’d never try it. I eventually gave in. Those damn eyes of his, compelling me to historical feats.

There, in the middle of the night, in the middle of the airport, we ate currywurst together. You should, too, if the occasion arises. The pork sausage is oily and slightly sweet, cut by the sharpness of the sauce which is tart and should be repulsive but, bafflingly, is not. The layer of fries underneath is crisp, and you need to eat them quickly before the sauce makes them untenable. The spices are gentle and warm. It all sounds awful, but it is not.

I did not write about currywurst, because it did not seem of note. I did not write about it, because it was in Germany, and in the past, and if I dove back into my memory then I would have to sit, for a little while, in a world where my father was still alive. That is a hard thing to do.

If I write about the trip when we ate the currywurst, then I will inevitably see pictures of him.

If I write about the currywurst, I have to step into the past. And then I am crying, and I have written currywurst so many times and I hate that word, and if my father read any of this he would say in his stilted way, “What … the hell … is the matter with you?”

And the thought of that makes me laugh, just for a second.

You get upset when I don’t write about things, dearest, but you never ask me why I don’t want to. Sometimes, it sheer laziness – I won’t deny it. But sometimes, it is because I know it will make me sad.

Your mustache is gone now, and so is my father.

One night, not that long ago, you convinced me to eat currywurst out of a truck that looked like a plane. My father was alive, and we were young.

You asked me to write about it, my love, and I have kept my promise. Now keep yours: live forever.

October 4, 2017

The Faded Glory of Route 66

My immigrant parents, while bestowing upon me the gift of worldliness, with their accents and many passports and the ease with which they code-switched, yelling at one another in English, German, Italian, and Russian, left a glaring omission in my childhood: there was no Americana.

It was not that America itself was absent from my formative years – indeed, it couldn’t be. I was an American, and my home was here. But my parents’ version of this country always had a European slant: my father telling me to go to Katz’s delicatessen, my mother’s knowledge of strange pieces of American pop culture that somehow had made their way across the pond. There was always something missing, some element of the heartland that wasn’t present.

Westward expansion fascinated me, but did not run in my veins.

When my husband first mentioned that we visit part of Route 66 while we were in New Mexico, I was confused. I couldn’t remember if it was real, like The Enchantment Under The Sea dance that I keep thinking is part of historical record and not simply a plot point from Back to the Future.

Later in our trip, at the National Museum of Nuclear Science and History in Albequerque.

But that road exists – like Marty McFly it may have faded at bit over the course of its adventures, but it never fully disappeared. It is not what it once was. Then again, none of us are. Roads, at least, can be repaired.

When I first saw this iconic strip of land, one that had been immortalized again and again in song and film, it was under repair, choked with traffic. The businesses along it had signs from the road’s heyday that now expressed disapproval of an impending rapid transit system.

There were nods to the people who lived here before a belt of asphalt ran through it.

There were signs that hearkened to the atomic age, which shaped New Mexico’s past.

Later, as the sun set and the sky grew dark, I went to a diner with the most handsome man in the world, and he regaled me with stories that I don’t remember under neon lights.

I think we were talking about Back to the Future. We are almost always talking about Back to the Future.

Later, I tried to take a photo of the two of us and failed.

Twice.

Some of us are Americans, but we feel excluded from our country’s history for a variety of reasons. I’m lucky enough and privileged enough that I can try and reclaim it. I interject myself into settings that are foreign to my family, and I make them part of my history. It’s a gift. There, on Route 66, with him and those damn eyes of his, I unwrapped it slowly.

October 3, 2017

I Visited The Birthplace of the Atom Bomb. Los Alamos National Laboratory and the Bradbury Science Museum, New Mexico.

Rand’s work had brought us to New Mexico for the very first time, and in a few weeks, we’d be in Japan. The timing was unintentional but it felt like my path was already set. If I was going to walk through Hiroshima, now long rebuilt, I couldn’t do so without considering the consequences of the bomb we dropped. And I couldn’t do that without visiting Los Alamos.

Los Alamos sits on a mesa, surrounded by the burnt umber of the Jemez mountains, under blazing blue skies. The drive up is lonely, and as the elevation rises the air grows cooler while the sun seems to grow more intense.

[image error]

[image error]

There is a single road that runs through town, and on either side there are a few sparse strip malls that house cafes and shops with names that suggest Los Alamos’ past: Bathtub Row Brewing C0-op, The Manhattan Project Restaurant (recently shuttered), and a half dozen others with the word “atomic” in their name.

In the early 1900s, the only thing here was a well-regarded ranch school for boys, which boasted graduates like William S. Burroughs and Gore Vidal. At a time when illnesses were treated with exposure to fresh air and sunshine, wealthy parents sent their sickly young heirs to the New Mexican mountains to enjoy a rigorous curriculum of study and outdoor activities. In 1942 the government took over the site, purchasing it from owners who had little say in the matter (who had, in turn, taken the land from indigenous people who had little say in the matter), and rushing a final graduating class of students out the door.

The U.S. government had been scouting for a site for The Manhattan Project, and Los Alamos met their exacting specifications – it needed to be 200 miles from an international boundary, isolated from the general population, with easy access to water and plenty of sunshine (this latter point wasn’t simply an indulgence – researchers needed clear skies so they could see the bomb’s detonation). The school’s location would prove an ideal site – high on a mesa, all entrances to the facility could be secured, and the dormitories could be repurposed as shelters for scientists and staff (though others would be built to accommodate Los Alamos’s growing population). The more well-appointed dorms had bathtubs and became known as Bathtub Row.

As physicists and military personnel poured into Los Alamos, the town began to grow. People who were assigned there brought their families. A school was built. Because there were so many single men working at the facility, young women were hired to perform clerical work in order to build a better social dynamic while people were working on the atom bomb.

That’s the thing about Los Alamos – there is this strange mix of the mundane and the extraordinarily terrifying. The deaths of more than 200,000 people resulted from this place. And they also held dance parties.

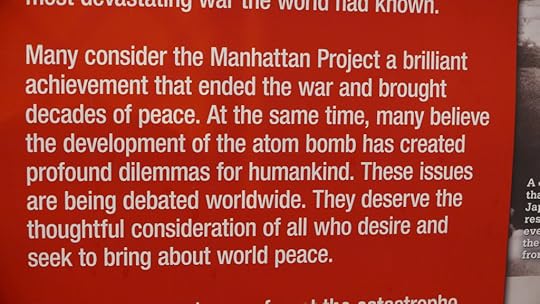

The Los Alamos National Laboratory now functions as a museum (The Bradbury Science Museum), one that largely skirts around the implications of the dropping the bomb. In their attempts to offend no one, the placards are shockingly dissatisfying.

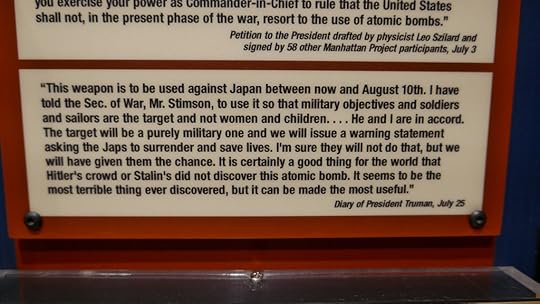

There are questions that remain unanswered – like how Truman’s directives that the bomb not be dropped on civilians, and that the Japanese be warned of the impending bombs – were ultimately cast aside.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki had some military importance – but as I noted in a previous post, they were largely chosen due to the fact that they hadn’t been bombed yet – and so they could showcase the weapon’s destructive capabilities more clearly. The result was heavy civilian casualties.

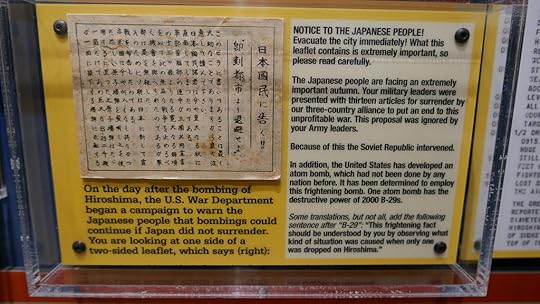

Some flyers were dropped on Japan, warning of additional bombs *after* Hiroshima had already been destroyed.

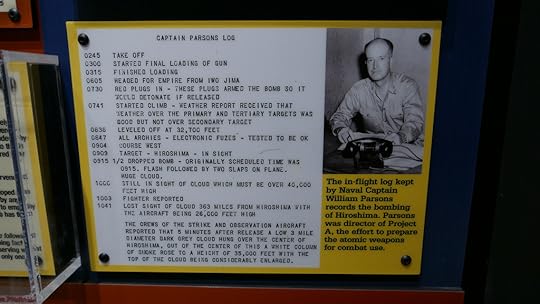

I found the flight log from the bomb drop on Hiroshima to be particularly startling in how clinical it is.

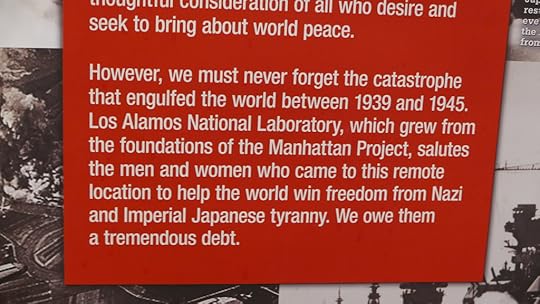

The museum itself doesn’t shy away from taking a distinct position about the bombs – it describes the women and men who worked on The Manhattan Project as heroes.

Most were oblivious to what they were building. They understood it was some sort of government project as part of the war effort, and when they were asked by outsiders what kind of work was “going on up there” their answers were vague or flippant. One woman who was only 16 when she worked at the post office of Los Alamos told people that they were installing windshield wipers on submarines.

As for the physicists, few, if any, considered their work heroic – for most, it was simply necessary, a request from the government to which they could not say no. Einstein said that if he’d known the Germans would fail in their endeavor to build the bomb, he’d never have advised the President to start building one. Oppenheimer, who was the lead on the Manhattan Project, claimed that “I carry no weight on my conscience”, but seemed to go through his remaining years a haunted man. While witnessing the explosion of the Trinity Test, which preceded the bombings, he quoted the Hindu scripture of the Bhagavad Gita, saying, “I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

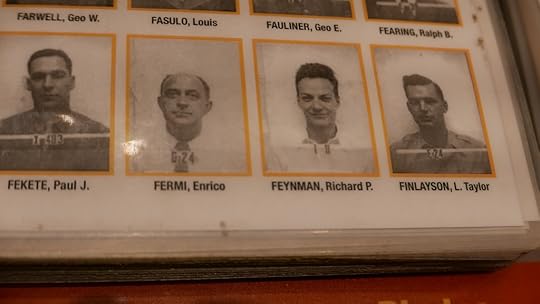

Of the many physicists mentioned in the museum, it was Richard Feynman who stood out to me more than the others, perhaps because of his age. Feynman was 27 in 1945; during his time working on the Manhattan Project, his wife suffered from tuberculosis (she would die a few weeks before Japan was bombed). He wrote about his time in Los Alamos with a sort of light-hearted detachment, and his later years would be characterized by an over-the-top personality. Many suggest that this was a facade – his contributions to the creation of the atomic bomb and his regrets surrounding it were profound. They claim his quirky persona was an affectation born from a man mired in grief, one who could not handle what he’d done.

He was charming; he had been madly in love with his wife. He was a chauvinistic asshole and a misogynist. Remember: People are not simply all good or all bad. They are murky and strange and complicated.

It’s not that I think the museum at Los Alamos is willfully misleading visitors – I simply think they have a particular narrative that they wish to tell, and it is one among very, very many. To this day, the ground underneath Los Alamos’ vivid blue sky remains toxic from nuclear waste. Like everything else here, the truth is far more complicated that what we can see. It’s a much harder to story to tell.

September 26, 2017

The History of the Atom Bomb, WWII, and A Case of Infinite Hindsight

When things go badly, I often look back and retrace the steps that were taken – by me, by my loved ones, by the electorate of Wisconsin, to see where things went awry. I do this with tragedies small and large, historical and current day, tracing the path back to what life was like before things were awful, if there ever was a before.

The noble claim would be that I do it out of obligation to those who have suffered, but the truth is probably closer to this: if I ever travel back in time, I’ll know who to stab.

This train of thought is handy; it absolves me of guilt and it makes me feel righteous. I can look at the status quo and pretend that I had no part in it. I can eschew the responsibility that I inherited the day I was born, the day I became something that neither my mother nor my father nor my brother was: a natural-born American. Wading into history lets me run from culpability while under the guise that I am embracing it. It is all very convenient.

And so I insisted that we go to Los Alamos to see The National Laboratory, where the U.S. developed the atom bomb during WWII, high in the mountains outside of Santa Fe, New Mexico. I say that “the U.S. did these things,” so you will understand that I alone am not responsible for them. I say that “the U.S. did these things” so you will understand that I understand that in some way, I am responsible.

I run from culpability. I embrace it. I knew six weeks later, I’d be in Hiroshima.

Later, in some other post, I will tell you about those visits (this is, after a travel blog, or so I claim), about two places tied together by war. But first, I must first retrace the path of history to a time before these weapons existed. Our current news cycle which makes it sound as though nuclear conflict with North Korea is inevitable; I felt like understanding how these weapons came about might help me make sense of that.

And while it didn’t exactly do that, my research did help explain how the U.S. can overlook civilian casualties in the name of some sort of “greater good”. A tendency which makes it much easier for us to contemplate the use of nuclear weapons, where there are inevitably civilian casualties, because radiation and fire are not discretionary.

Let me begin with indisputable facts: since their invention, nuclear bombs have been used twice in warfare. Both times were during WWII. The targets were Japanese cities full of civilians. The U.S. dropped both of the bombs.

The creation of these bombs – part of an Allied project known as the Manhattan Project (largely led by the U.S. with support from the U.K. and Canada, I say out of historical accuracy and also because I think that if I spread around the blame, it will be easier for me) – began in 1942, on a site in the mountains of New Mexico known as Los Alamos. Three years before, Einstein had written to FDR, warning him that recent developments in physics – primarily the splitting of a uranium atom – could be applied to the creation of bombs of unprecedented force. Einstein believed that the Germans were already working on such a bomb – and the fear of them unilaterally creating it was what prompted FDR to launch The Manhattan Project.

It was said that the country’s top physicists disappeared overnight as they were called from their work in academia and brought to Los Alamos. Einstein himself did not work on the bomb (he was perceived as a security threat because he was German), though his letter was the catalyst. But many of his colleagues – including Leo Szilard (co-author of the letter Einstein sent to FDR), Enrico Fermi, and J. Robert Oppenheimer (who was in charge of The Manhattan Project) did.

The project remained so secretive, that many of the physicists working on it didn’t understand what the final objective was. A select few knew that they were creating an atomic bomb, but there’s speculation that many of them thought the weapon would function solely as a deterrent. Physicists are not usually asked to contemplate wartime killing; best to have death exist only as a theoretical. And so America assembled the world’s greatest scientists to work on a weapon many of them believed would never be used.

On August 6th, 1945, the first atom bomb ever used in warfare was dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Three days later, the second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki.

Replicas of Fat Man and Little Boy – the bombs dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima – at the National Museum of Nuclear Science and History in Albuquerque.

By the time Hiroshima and Nagasaki were bombed, Germany had already surrendered. Hitler’s scientists hadn’t succeeded in creating their own nuclear weapon as Einstein had predicted (Einstein later said that had he known that Germany would fail in their endeavor, he’d never have written to FDR). The bombs were no longer deterrents because there was no one to deter. Rather than exist as some sort of theoretical safeguard against Germany’s use of the bomb, they had now became an active part of the U.S. arsenal.

Why Hiroshima and Nagasaki?

Unlike Tokyo, neither Hiroshima or Nagasaki had been bombed yet – they were pristine targets, and were compact – each one encompassing just a few square miles. The U.S. chose these cities because they felt they would showcase the absolute devastation that could be done by an atom bomb. (This isn’t speculative – this is by the U.S.’s own admission.)

In a sort of distorted moral reasoning, the target committee hoped doing so would mean that the bombs would not be used in future wars.

So, they decided this bomb would not just kill — it would do something biblical: One bomb, from one plane, would wipe a city off the map. It would be horrible. But they wanted it to be horrible, to end the war and to try to stop the future use of nuclear bombs.

Though each was hit with a fission bomb (in which an atom is split, unleashing a force wave that does initial devastation, followed by radiation), the weapons themselves were slightly different owing to the materials used and the method of detonation.

I’ve always found these details profoundly disturbing, because it seemed like the U.S. was dropping different bombs in part just to see what would happen. Would plants be able to grow on irradiated land? Would generations be affected by the fallout? Would water be drinkable? There were myriad questions about the aftermath of dropping a nuclear weapon, and the U.S. turned Japanese civilians into unwilling experiment subjects (and victims) in order to find out an answer. Hundreds of thousands of people died, and their lives hinged on a panel of men who were fighting over which cities to bomb. Kyoto was spared because the U.S. Secretary of War had honeymooned there.

Were the bombs necessary?

The story I’ve been told, time and time again, was that the U.S. had to drop the bombs, because they helped expedite Japan’s surrender, ostensibly saving more lives than were lost. I’ve heard this during history classes throughout high school and college, I saw it reiterated on the placards in the museums at Los Alamos and Hiroshima. The prevailing narrative is this: the bombs brought about the end of the war.

Most of us accept this rationale – for most of us, it’s the only story we’ve ever been told. The more research I did on the topic, the more this narrative became problematic.

From The American Conservative:

The myth, the one kneaded into public consciousness, is that the bombs were dropped out of grudging military necessity, to hasten the end of the war, to avoid a land invasion of Japan, maybe to give the Soviets a good pre-Cold War scare. Nasty work, but such is war. As a result, the attacks need not provoke anything akin to introspection or national reflection. The possibility, however remote, that the bombs were tools of revenge or malice, immoral acts, was defined away. They were merely necessary.

In giving the bombs credit for ending the war, we do not need to analyze the morality of their use. We do not need to second-guess America’s actions. And we’ve created precedent for subsequent U.S. military decisions to deserve less scrutiny. Civilian casualties are now a common result of U.S. military policy, all under the guise of being “necessary” – a train of logic that can be traced back to dropping the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

More than just creating this alarming legacy, there’s another problem with saying that the bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima brought about the end of the war: it may be patently untrue. In the immediate aftermath of the bombings, the global community did not entertain any such belief that the destruction of Hiroshima persuaded Japan to surrender.

Some historians argue that Nagasaki, in particular, played no strategic part in Japan’s surrender – the country’s Security Council had already completed discussion of surrender before they heard of the second atomic attack.

So why did Japan surrender?

The growing reason – one that is touted by Japanese and American historians alike – is that the Soviet Union’s entry into the war was the deciding factor in Japan surrendering. Stalin’s proximity to Japan meant that they could invade the country in a matter of days with troops, and incur far fewer casualties than a U.S. invasion, which would takes months and be far less effective. Russia entering the war meant that it was unwinnable for Japan – and some argue that it was that realization, and not the bombings – that led to Japan’s surrender.

Why do both countries embrace the myth?

Saying that the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people played no role in ending the war is a tough story to swallow – it makes neither the U.S. nor Japan look terribly good. And there was plenty of incentive for both countries to embrace the narrative that the bombs ended the war. The U.S. now had some sort of moral justification (specious though it may be) for using a weapon of unprecedented force on two largely civilian cities. For Japan, it allowed a similar reprieve from consequence. If Japan’s reason for surrender was the Soviet Union’s entry, then the leaders of the country become fallible – a significant problem, because it meant that the Emperor (who was considered divine) was an imperfect agent. But if a nuclear weapon were the reason for their surrender, then culpability is removed from Japan’s leaders. They couldn’t have known or expected the U.S. to have a weapon of such unprecedented force.

So both countries had incentive to buy into the story that the bombs ended the war. Now, decades removed from the events, it’s impossible to say what the truth is. The bombings may have ignited the Cold War and given the U.S. a blueprint for ignoring civilian casualties in the future.

One thing can be said, definitively: hundreds of thousands of civilians died. And that, absent of all speculation, is enough to grapple with.