Geraldine DeRuiter's Blog, page 9

November 29, 2018

Emergency Porchetta, Canelli, Italy

The emergency porchetta was my favorite part of the trip.

That is a strange thing to say for a lot of reasons. For one, I don’t know if the concept of emergency porchetta is widely known. A Google search for the term reveals four results, the most salient of which is someone looking for cooking advice. “Emergency porchetta question” they write. But the urgency seems to come from the nature of the query itself, and not the hunk of roast pork it pertains to.

For another, we had a great trip. Despite the endless rain and the grey skies and the hotel mishaps and the projectile vomiting on the side of the road in Genoa (my apologies to all who witnessed it), we had a wonderful week in the north of Italy. So many things happened that reminded me of why I love to travel.

But damn it, that porchetta was everything.

It could have ended differently – all travel stories can. That’s what travel is supposed to do – to open up a door to a thousand possibilities. And when I look back on the scene – the four of us wandering through a market in Canelli, the air chilly and damp, the sky that deep blue-grey that it always is in the early evenings of late fall, when the sun has never bothered coming out – it could have gone terribly awry. It was crowded and we were tired and Oli was hungry – that urgent hunger that comes on quick and catches you off guard.

Canelli from above.

And damn it, Oli is a picky eater. I mean picky. We passed bar after bar, but they only served pasta (which he doesn’t eat because he’s an alien), or no food at all, or weren’t open yet. And then we came across a stall where a man was selling all manner of salumi. A vegeterian nightmare of every sort of cured meat you could imagine. And there, at the center, a roast of pork, a giant thing the size of a not-insubstantial child.

“They have porchetta.” I offered. It seemed like a long shot.

“Yup,” Oli said, with zero hesitation. “That works.” Because Oli is picky, except when he isn’t at all.

I told the man behind the table that we wanted some, and he indicated with his knife the thickness of a cut.

No, I said, that’s too much.

No, Oli corrected me, that’s just fine.

Sometimes you don’t realize the scale of something until it is in your hands, and it was only when the man wrapped it up and we saw the price that we realized that Oli had just paid 20 Euros for half a kilo of porchetta. Not an unreasonable price, mind you. But you know, it was half a kilo of porchetta.

The face of man who has just purchased a pound of roast pork.

Oli stood in the middle of the crowd, and pulled off a chunk.

“Oh my god,” he said. “Have some.”

And we all stood with him, picking at it with our fingers in the twilight, dubbing it “emergency porchetta.” We returned to the phrase again and again – the accidental purchasing of a pound of roasted pork on a chilly night. The sort of thing that turns your evening from potentially disastrous to absurdly memorable. That sort of unpredictable, unrepeatable moment that will forever be grander than the sum of its parts.

November 28, 2018

When Online Harassment Shows Up on Your Doorstep

The letter arrived at my house at the end of October in a plain white envelope with no return address. My name – or some approximation of it (“Depruiter” it reads, because, in the words of my beloved, “The person who addressed it is an idiot”) has been printed out on a label and affixed to the front. The nondescript nature of it set off some sort of alarm in the back of my brain – something wasn’t quite right, though I couldn’t say what.

We get a lot of mail. I’ve tried to whittle it down as best I can, but towards the end of the calendar year there’s always uptick in it. I rummage through countless catalogs and requests for donations from specious sounding not-exactly-non-profits to pick out the things I want to keep – primarily a handful of holiday cards that I will display on our mantle until they’ve collected dust in February or -who am I kidding?- April.

I suppose for a brief moment I figured the card was the latter – someone had printed out an annual family newsletter and skipped a fancy envelope and return address. “Depruiter” in that context, wasn’t all that surprising – some of my own family members can’t spell my last name.

I torn into the envelope, and found my name spelled properly on the inside.

“Ms. DeRuiter,

After reading your story (on bullying) it never ceases to amaze me how weak some people are.”

The writer was referring to an article I wrote for The Washington Post earlier this year – a piece about having more empathy for bullies, and how I felt when I found out my own childhood bully had been murdered. How I grieved for the little boy who’d made my life hell.

I read on. The nature of the first sentence could have been taken either way – perhaps the writer was referring to my bully in that first sentence – perhaps he was misidentifying one child’s manifestation of pain as a weakness (and completely missed the point of my article in the process). But it soon became clear that he was talking about me. I was a victim of bullying because I was weak.

The rest of the letter included a shockingly graphic story of violence – one which he inflicted on his bully, ending his antagonist’s luminous high school football career (which sounded like a disproportionally severe punishment for the sort of antagonism that the bully inflicted, even by the victim’s own account). He rambled, incoherently at times, lauding his own career in the Air Force (from which he’d retired after 30 years).

“That’s how you deal with bullies,” he wrote at the end of his letter. There was no signature at the bottom, no name, nothing to indicate who’d written the garbled, violent nonsense that had appeared in my mailbox.

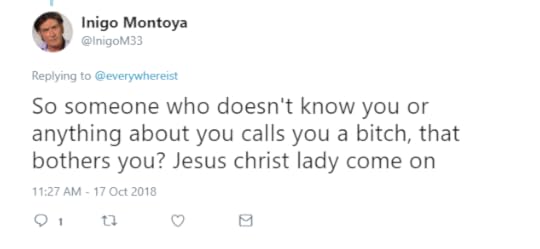

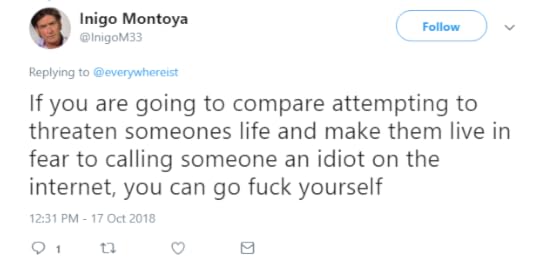

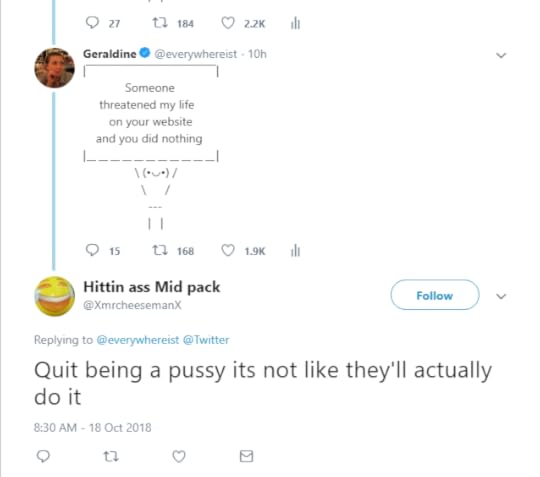

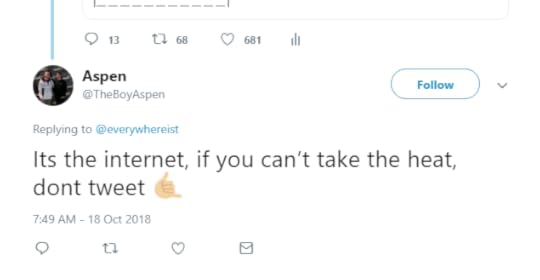

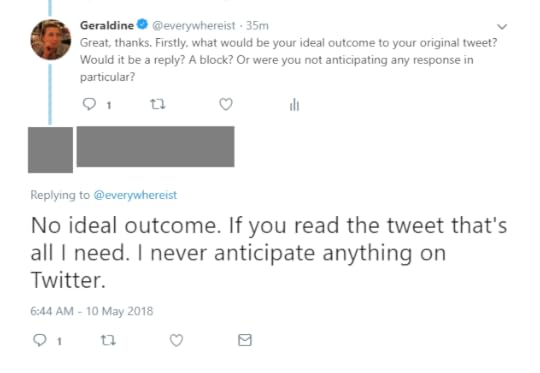

Those of you who follow the blog know that I get hate mail. And hate tweets. And hate comments. And hate Amazon reviews (which are rarer because they usually require a higher level of literacy and a credit card). If there is an anonymous medium in which to convey hate, I’ve received it. Some days, if there is more fight than judgement left in me, I will reply. I will ridicule them for their undoubtedly terrible grammar and awful punctuation. But more often than not, I delete and block. If a threat is incredibly egregious, I’ll screencap it for reference before reporting the person to a site or platform moderator (an entirely Sisyphean effort which yields nothing other than a fleeting sense of hope). And then I try to go back to my life as a -*checks notes*- “vile, man-hating cunt.” (Which is a pretty great life!)

This letter, despite the description of graphic violence, wasn’t unusual. It was milder in nature than many others I’d received but no less anonymous. It was in response to a piece that was higher profile but not particularly controversial – most of the replies I’d received for the article had been incredibly, effusively supportive and thoughtful. A lot of people told me that they’d started looking at their own childhood bullies differently. The entire experience of writing for the Post had been a positive one from the editing process down to most of the replies the article received. But this damn letter shook me to my core for one very significant reason.

The person who wrote it had sent it to my house.

After it arrived, I frantically searched online for any websites that had my address listed. Past threats mean that I’ve already done this, and requested it removed from numerous listing sites, but one or two had failed to honor the request. I sent them scathing follow-ups. A friend of mine who has dealt with extreme online harassment (doxxing, death and rape threats, stalking) told me that it’s largely a futile effort. My address is out there. So is yours, probably.

Being a woman with an online profile has strange ramifications. The barrage of harassment is so consistent, you start to forget what’s a reasonable reaction to something and what isn’t. We are told repeatedly that online harassment is simply words – an argument that ignores the fact that verbal abuse is abuse. Being called a cunt, being called stupid, or weak, or threatened with graphic accounts of rape or violence is no less terrifying because it’s being meted out to us 240 characters at a time.

We are told that the threats we receive are nothing to be concerned about – that they remain online, as though somehow there’s a line of demarcation between the internet and the rest of the world. (Spoiler: there isn’t. We do everything online. We buy plane tickets and clothing and groceries, we do work, we interact with friends and family, we watch TV shows and movies, we pay our bills and our taxes. The internet is real life. Those who pretend otherwise are simply trying to separate themselves from the consequences of their actions). That the horrible things that people say to us on the internet can never hurt us in real life.

That’s bullshit.

Besides just being psychologically taxing and stressful as hell, there are plenty of other real-world implications to online abuse. Astroturfing – concerted, fake, harmful reviews by hateful misogynists of female-fronted projects – can destroy careers. Doxxing can force victims from their own homes. The threats which begin online can be so intense that conferences stop inviting certain speakers because the security risk is too great.

And sometimes the bullshit that happens to you on the internet shows up at your doorstep.

When writer Jill Filipovic was in law school, she found hundreds of threads about her on an anonymous online platform designed for students at her university. The comments were a litany of graphic, sexual threats (“I want to brutally rape that Jill slut,” “I’m 98% sure that she should be raped,” “that nose ring is fucking money, rape her immediately”). She notes that what truly shook her was when one commenter said that they’d met her, and that she was extremely pretty in person. The comment wasn’t graphically violent – it was even kind. But for Filipovic, it broke down that barrier between the online and the so-called real world that so many of us pretend exists.

What followed was numerous people – in an online thread about how she deserved to be raped – chiming in about the times they’d met her in real life. The implications of that are terrifying.

“Well, they aren’t going to show up on your doorstep and do that in real life,” is the oft-heard refrain I hear from those who say that I take online abuse too seriously.

The onus on solving online abuse is placed on the victim – not on the person making the threats, not on the platform that enables it or the online culture that fosters it. The problem is that we, supposedly, need to toughen up. And so many of us have. I’ve seen how people change – how I’ve changed – from the constant barrage of insults and threats. You become a different version of yourself. You become hardened and numb. But that doesn’t address the problem. Being numb to rape threats isn’t a superpower.

Not-so-fun-fact: You can’t actually turn online harassment off. Even if you walk away from your computer, it stays with you.

And it doesn’t stop the harassment.

(None of this is new information, I realize. But it seems like until something changes, the only alternative is to repeat it until someone in power listens.)

After Filipovic graduated, one of the men from her forum showed up at her office hours, incoherently yelling at her about things that had appeared on the forum. She would later find out that he was in the middle of a psychotic break, one that he would later be hospitalized for. She managed to get out of the situation physically unharmed (and he would later be arrested for making death threats … to someone else). But the barrier between the online world and the offline one was forever broken for her.

The letter I received from the anonymous, ranting assaulter is nothing close to that terrifying. But it sits on my desk, and though there is no way I should be able to find it amidst the pile of papers and receipts that make up my workspace, I know exactly where it is. My hands go to it instantly – under a pile of paid bills I have yet to shred – drawn to it like a homing beacon. It makes me anxious, but I feel like if I throw it out or tear it up, I’ll unleash something worse – like I’ll somehow become possessed with the soul of an angry old misogynist and start screaming that the wage gap is a myth. At the very least, I’ll have destroyed the evidence. And that seems like a bad idea. So instead it just sits there.

I can turn off my computer. I can stop tweeting. I can stop working in a field that I’ve invested so much time and energy in. I can give up my career. It’s unfair to ask me to do any of those things – and besides, even if I did, it wouldn’t matter. Somewhere, that guy, and thousands of others like him exist. Odds are, he won’t do anything. But he still knows where I live. You can tell me that the harassment that happens online stays there. But this letter on my desk tells a different story.

November 2, 2018

Halloween 2018: Indiana Jones and Punching Nazis.

I don’t know when the idea for this year’s Halloween costume originated. Rand and I have been talking about it for years. It’s the sort of thing that stays simmering on the back burner for so long that you almost have to wonder if it’ll ever come to fruition, or if the idea will simply run its course without ever being realized, growing stale before it sees the light of day. I had fallen in love with the concept for these costumes years ago. Then I grew tired of it, and went on to more pressing, timely things.

And then the idea of punching Nazis became far too relevant and timely again.

And Rand continued to perfect his impression of Sean Connery.

And I went to the thrift store and found the perfect shirt. And the perfect jacket. And suddenly the pieces started to fall into place.

Sure, sure, Indiana was the dog’s name. And okay, he was a terrible, I mean absolutely terrible professor, if you really think about it. But also:

And:

What’s the old saying? Be the Halloween costume you’ve always wanted to fuck? Pretty sure that’s it.

So this Halloween, this happened:

Drs. Henry Jones, Jr. and Sr.

Which I think we nailed.

[image error]

[image error]

Oh, and then … our poor friend Rob. We enlisted him to dress up as The Grail Night. A character who is on screen for maybe 3 minutes total. And good sport that he is, Rob went along with it, wooly eyebrows and all.

I asked Rob if he had placed the fake eyebrows directly over his real ones (he had) and what was going to happen when he tried to take them off. “I’m punting that problem down the road.”

[image error]

If you haven’t seen Indiana Jones and The Last Crusade, this makes little sense. And a fair number of people hadn’t. But the few dear souls that got it … well, they really got it. One guy drunkenly shouted, “OHMYGOD I FEEL LIKE I’M IN THE MOVIE.” when he saw us. Which absolutely made my night.

And there was another unexpected side-effect of my costume: dressing up as one of my favorite fictional male protagonists left me feeling like a badass in a way that I could not have anticipated. I told Rand that I was tempted to dress like this all the damn time. After all, it was comfy as hell, strangers were screaming “INDY!” at me, and TWO PEOPLE GAVE ME THE GUY NOD.

Plus, we were adorable.

[image error]

[image error]

Even if this is, you know, profoundly weird, because we’re father and son.

Though it took us years to finally get around to it, I’m so happy these costumes eventually came to pass. Because they were so much fun. And it was nice to take a break from all the garbage in the world for a little bit … while still remembering one crucial thing:

Nazis? They’re the bad guys.

October 30, 2018

Tragedy, Antisemitism, and Being Not Quite Jewish

I have yet to call my in-laws (my husband’s grandparents) in the wake of . A few days have passed. For the collective American consciousness, the lifespan of a mass shooting is short. The newscycle has already moved on, as has everyone’s social media posts. (Even this post, written two days ago, feels a little outdated. The timeline for caring about gun violence is too brief in our country. It’s like that by design.) The moment to reach out to my in-laws may already have passed. Perhaps I shouldn’t remind them of the tragedy. They are in their early 90s. Besides, I do not know what condolences to offer, other than that I am sorry and that I love them. I am unsure what else there is to say.

I will likely fish the hamsa that my aunt gave my mother years ago – a gift from her travels – out of my jewelry box. Most people don’t notice the charm when I wear it. Those who do are usually Jewish or Israeli. I nod as though I understand the meaning, as though it is more than just a reminder of my now-deceased aunt.

But wearing these icons and loving these people does not make me Jewish.

I was not raised in the faith, though one of my closest friends growing up (a woman I am still close to now, a woman I will likely be close to until the day I die) was. Through her I quietly absorbed her family’s religious traditions, watched as they lit candles, and ate matzo ball soup for the very first time in her home (her mother’s abject shock when she found out that I had never had it remains indelible in my mind. She immediately served me up a bowl, and digging into the spongy little orbs – a texture unlike anything I’d ever known before – I declared them magic).

But none of this made me Jewish.

My father was almost sent to the gulags as a child. The day before they were supposed to be carted off in trains, the Nazis took Kiev, and the Russia soldiers fled. I don’t know which battle of Kiev it was – there were two. But my father was either four or six at the time. In either case, the gulags would have been a death sentence.

And so instead he ended up in a displaced person’s camp in Germany. A step up from a concentration camp, the sort of place that you could survive even if you were an underweight kid. You’d get out with cavities in your teeth and a dark spot in your heart where your childhood should have been, but you’d get out.

My father told me about how a young Nazi soldier once shared a liverwurst sandwich with him. He said he had never tasted anything like it. And I realized that this was, for my father, one of the closest things he had to a happy childhood memory.

But none of this made us Jewish.

I’ve scrolled through my lineage, looking for it. There are scraps, here and there, a tiny sliver of Semitic ancestry. When I told my husband this, with some measure of excitement, he laughed. I married a Jewish man with kind eyes who is non-practicing and eats pork on a regular basis and forgets about the high holidays right up until they are almost over. He’s the first person in his family to marry someone who isn’t Jewish. The entire line stretches back, unbroken, with observers of the faith, right up until us.

Rand during the holidays a few years ago, wearing his new Hanukkah present.

When a colleague of his called me a shiksa at a work event, Rand stared him dead in the eye and told him to never repeat those words again, before walking away. He’s refused to speak to him ever since.

When someone at a dinner we were invited to said that Rand didn’t look Jewish because he “didn’t even have a hook nose”, my husband gently placed his hand on my knee, ensuring that I wouldn’t leap across the table and stab him with my fork.

When I raged about it to my beloved later, he whispered gently, “I know.”

This was all new to me, but not to him.

Rand at Hanukkah a few years ago. He’s wearing a blanket draped over his shoulders, but it looks like a multi-color tallit.

I’ve been told the Holocaust never happened, and that Jews control the media and the banks and the government. Most people can’t tell if I am Jewish or not, so they simply assume that I am and lump me into the group. “You’ve done this,” they say. We each have been called the k-word. My husband has been threatened with the gas chamber. His maternal grandparents narrowly made it out of Europe during WWII as children.

That’s the patina of protection I get from having my Jewish ancestry be so far out. From knowing that the camp my father was in during WWII was one he could get out of. And so these comments don’t cut me as deeply as they could. They never can.

But they still cut.

Because though I’ve grown desensitized to the horrible things said about me, the horrible things said about the people I love still manage to hurt. And I don’t know if that is a good or a bad thing.

When news of the shooting broke, I checked on my husband’s cousins in Pittsburgh, to make sure they were safe. I wondered what I’d say to my grandparents-in-law. I hugged my husband.

I am not Jewish. I will never know the pain of this specific hate crime as acutely as those close to me do. But the line between the people we love and ourselves is a thin one. You do not need to be Jewish to be enraged by Antisemitism. And you do not need to be Jewish to be heartbroken.

September 18, 2018

The Women Who Write Letters

(Above: my student ID in 1999. Let’s just keep our comments to ourselves.)

There’s this pattern I keep seeing. It goes like this:

Woman accuses man of sexual assault. Man denies accusations.

Man’s PR team then releases numerous letters from women saying that he’s not a sexual harasser because, you know, he didn’t harass them.

It’s happened most recently with Judge Brett Kavanaugh, Trump’s Supreme Court nominee, after Dr. Christine Blasey Ford accused him of sexually assaulting her in the early 80s. But it’s happened with Al Franken, and Tom Brokaw and countless others, resulting in a mental puzzle that becomes increasing difficult to parse: a woman who accuses a man of sexual assault is immediately under suspect – but one who defends that same man often has her word heralded as gospel.

Whenever these letters come out, I cringe. I become enraged. I want to scream about how it’s very easy for people to be kind and awesome to one person and awful to someone else. How a lot of the time, that sort of cognitive dissonance is actually what enables people to do horrible things.

Look, I’m obviously not a bad person. I have lots of women who support me! I can’t be a misogynist/rapist/abuser because misogynists/rapists/abusers do not have female friends who come to their defense.

And a part of me wants to scream at the women who write letters defending men who’ve been accused of hurting women. I want to yell at them, and ask them what the hell they’re thinking. But part of me already knows. Because when I was 19, I wrote one of those letters.

My sophomore year of college, I had a summer job at a youth drug rehabilitation intake center. I was a house manager, which meant that I mostly kept an eye on the residents (they needed to be supervised at all times, unless they were in their rooms), who were scarcely younger than me. I was new, and young, and low on the whole pecking order – I deferred to the therapists (one of whom happened to be my mom, though our hours rarely overlapped), to the clinical supervisors, to the other house managers.

I lied and told the residents that I was 20, since I very nearly was, and I thought it might lend me a little more of the authority which I so sorely needed. Most everyone – coworkers and residents alike – saw me as one of the kids, and it was problematic to say the least. One patient developed what a coworker described as a “weird, hostile crush” on me, and it became impossible for me to work the halls alone. When I told his counselor about it, he said, “You kids are going to have your disagreements” and then made us shake hands. I still cringe at the memory.

I broke up fights, I was physically intimidated, I had horrible things said to me by the residents – and I accepted it all as part of the job because, well, they were kids. On one occasion, I retreated into our communal office because I was almost on the verge of tears and I’d been told that if they saw you cry, it was all over.

One day one of my fellow house managers – Kelly (yes, that is a fake name), a woman who had helped train me and who I looked to whenever I had questions, came to me with a request. One of the former female residents, a teenage girl, had made a sexual harassment complaint against a male therapist. Kelly wanted me to write a letter defending him and admonishing the resident.

“You know how she was,” Kelly said, referring to the resident. She explained that the patient was just saying these things to avoid further consequences – and possibly time in juvenile hall.

“I don’t,” I said. “I’ve never actually met her.” She’d left the facility long before I started working there.

Kelly explained to me that this was sort of thing the resident did – she was a liar. And then she told me that if I couldn’t write a letter condemning her, I needed to write one in support of the therapist.

I stammered, trying to get out of it. This all felt uncomfortable in a way I couldn’t quite pinpoint. Kelly ignored me, placed a pad of paper in front of me, and started dictating things I could say. She told me she’d be back later to pick up my letter.

I stared at the paper, unsure exactly what had happened. Kelly and I worked together almost daily and she had far more seniority than me. I wasn’t sure how I was supposed to say no. I decided that I would simply write about the therapist, who had been pretty nice to me. I mean, there was nothing wrong with that, right? I was just writing about him, and keeping the peace, and making Kelly – with whom I worked very closely – happy. This logic somehow worked for me, and I started writing.

When Kelly came back, I handed her the letter, and she read it over and told me how great it was, and thanked me.

The next day, Kelly came back with a typed version of my letter, and told me to sign it. I figured my obligations to her were over, so this caught me off guard, and something about the letter being typed – and more than just a note I’d jotted down – panicked me. It would have been my last chance to object, and I tried to, feebly, but when Kelly ignored my protestations and simply held out a pen to me, I signed the letter. I winced as I glanced up and saw a typo, and wondered what other changes had been made. But Kelly was near frantic to get my letter out, and snatched it from me quickly. That, nearly 20 years later, is what I remember: the urgency with which everything needed to be done.

My mother was upset when she found out, but she was clear that blame rested on me and no one else.

“Why on earth would you would do that?” she asked me.

“I thought I had to,” I said quietly. I told her that the statement of a 19-year-old wouldn’t make a difference, and my mother warned me about underestimating my own role in the situation.

I don’t know what became of my letter. I don’t know what happened to the therapist, or to the resident. But to this day, I feel a wave of panic whenever I think about what happened. I wouldn’t have written the letter if I’d thought I’d had a choice in the matter.

But I genuinely didn’t think I’d had a choice.

We obviously shouldn’t blindly believe any allegation without investigating it – but we should know that a group of women writing letters to admonish a man doesn’t prove his innocence, either. They’re irrelevant, even if those letters are written under the best of circumstances. And a lot of times, they aren’t written under the best of circumstances.

I don’t mean to broadly excuse every woman who writes a treatise defending a male harasser. It’s done for myriad of reasons. Some women simply can’t reconcile the cognitive dissonance between someone being kind to them and being awful to someone else. Some women need to embrace some sort of just-world phenomenon in order to make themselves feel safe, and that means turning a blind eye to the suffering of other women and pretending that everything is just fine. Some women just want to help out a friend who’s been accused of something awful. Some women are assholes.

And I don’t want to remove agency or accountability from women in positions of privilege who do that willingly. But we also need to acknowledge that a culture that allows women to be harassed or assaulted can also easily allow women to be intimidated and coerced (yes, even by other women). After Tom Brokaw was accused of inappropriate behavior, a large number of women staffers have noted that they felt pressured to sign the letter defending him. Many felt that if they didn’t, there would be repercussions down the line.

When someone in a position of authority tells you to do something, a lot of times you just do as you’re told. Even if ends up haunting you for decades. People who resist are often the ones who have the privilege of resisting. Or maybe they just have an amazing strength of character and empowerment – something that I certainly did not have when I was a teenager.

I’m not 19 anymore. I’m self-employed, and have been for a decade. I work in my PJs, I take breaks to do laundry, free of any sort of office dynamic that makes me feel forced to vouch for the character of someone who may or may not deserve it. Every time I read a letter from a woman defending a colleague who’s been accused of harassment, I remember that her experience can be entirely true and it still doesn’t change anything. And then I wonder what role pressure and fear might have played in writing that letter. Because for me, at 19, it was a big one.

September 4, 2018

I Quit Twitter for a Month.

I quit Twitter for a month.

This should not sound like a profound thing, but for someone for whom the social media platform was essentially an extension of my psyche, the act has felt monumental. I have said, again and again (usually when talking of internet abuse and responding to people who tell me that if I don’t like I “can just leave”) that for me, and many writers like me, social media, and Twitter, its enfant terrible, are not optional. If you are trying to sell a book, the first thing a publisher wants to know is “What is your social media following?” Because more important than the book you are writing is the audience of people you can market it to. This is not cynicism and I say it without judgement. It’s simply how it works. If you want to write, you need an audience. And unless you are a literary luminary – like Ta-Nehisi Coates or Lindy West, both of whom have quit the platform – you need to be on Twitter.

The month off came in the wake of an exhausting summer – the sort of summer designed to break your heart in a thousand ways. I watched the impervious fall into grief, saw women made of iron cry so much I wondered if they’d rust, witnessed men I thought were carved from stone start to crack. The circumstances of the last few months have left the skies filled with smoke, and people I love filled with sadness, and in all of this there was no room for anything else, certainly not for the hoards of faceless strangers lining up to call me a cunt on a micro-blogging platform.

I’d promised this hiatus a while ago – when I was working on my presentation for World Domination Summit, and wading further into the cesspool of my hateful replies, I vowed that I would take a break when it was all over, throw my phone into the proverbial ocean and just breathe for a while. I spent the remainder of that month still fused to my phone, still clicking onto a new window to open Twitter every time I sat down at my computer, instead of blogging or working on that new book proposal I owed – and still owe – my agent.

Any time my mind started to wander, I’d click over to my feed (a perfect word to describe the endless stream of information that poured from the social media sites I visited. I felt like a chicken, pecking repeatedly at things that offered sustenance but no joy). Sometimes I’d diversify – I’d manage to stop checking Twitter for a few minutes only to hop over to Instagram or Facebook for a while, before returning to work. No, that’s a lie. I didn’t return to work. I went right back to Twitter. I don’t know when things because untenable for me, when my attention span became so terrible that only a few minutes (if that) could pass before my mind would wander to a place where I could find easily digestible bites of information delivered in chunks of 240 characters – or less – at a time. I’d stopped reading articles and instead only consumed headlines, I’d stopped being able to follow conversations with friends. My body would be having dinner somewhere but my brain would still be scrolling through my feed, wondering when I could get back to it.

And for what? For the occasional thrill of knowing that a tweet had gotten a few hundred (or perhaps even – gasp – thousand) retweets? For the constant stream of abuse and name-calling that accompanied any such attention? Because praise and success don’t exist in the online world – at least not for a woman – without hostility and abuse and threats. And the model of not knowing what tweets would succeed and which would fail followed the same model of unpredictable rewards that I knew kept gamblers addicted. You never knew when you were going to strike it big, so you kept going in hopes of getting that little rush and maybe having an editor reach out to you offering you a column where you could string a whole bunch of pithy thoughts together and get paid for it.

August 1st became day 1, and I told no one, convinced that I would fail. The first few days I found myself checking Twitter – not as a willful digression but completely out of muscle memory.

“What the hell am I doing?” I’d say when I caught myself, immediately closing the window.

Three days in, I found myself reading Rand’s Twitter feed over his shoulder, so starved for it that it didn’t matter that I was reading about tech and marketing news. Six days in, I realize that I had no idea where to get news from. Do I just … go to the news sites? Can you do that? That first week it felt like the power had just gone out and I was wandering around in the dark, trying to figure out what the hell to do next. I found myself drifting over to Facebook and realized that I could easily swap one platform for another, so I decided that I wouldn’t check any social media for the entire month (though I occasionally scrolled through Instagram while waiting at the doctor’s office).

I had so much time.

(Don’t worry, I didn’t accomplish anything with that time.)

Ten days in, I met Dana Schwartz, patron saint of saying clever things on the internet, and it felt like a cruel joke that I couldn’t tweet about it. But around that time the ties that bound also started to loosen. I stopped walking with my head down into my phone. I was able to follow conversations better. I started responding to email in a timely manner.

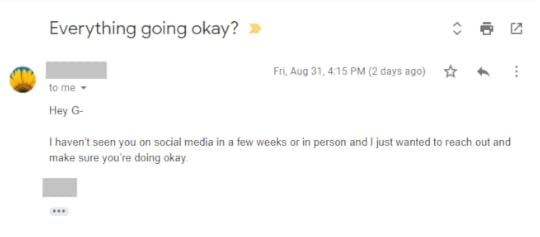

I finally told Rand about the project almost two weeks in, worried that his excessive encouragement might actually have the opposite effect. Perhaps he sensed this too, because he simply smiled and said, “I think that’s a great idea,” but his eyes betrayed him. They were bright and shiny and so, so relieved. A few days later he told me that friends had started emailing him, concerned about me.

“Geraldine hasn’t tweeted in a while,” they wrote, “Is everything okay?”

Eventually people started reaching out to me as well, inquiring about my well-being.

“Yes,” I said, “I’m fine. I’m just taking a break.”

One friend told me that he’d seen me in the middle of all of this and so he knew that I was okay – otherwise he’d have been concerned.

“Still,” he said of my hiatus, “It’s strange. You are Twitter.”

Some postulated that the abusers had gotten to me, and so my hiatus was understandable, and I was left wondering if that was the case. Yes, there were days that I didn’t want to deal with Twitter’s endless stream of abuse and vitriol … but the scope of what I dealt with didn’t seem that big a deal in relation to what other women I knew put up with to have their voices heard. I hadn’t been abused off of Twitter … had I been annoyed off of it?

I paid my bills, I cleaned my desk, I did the sewing and the laundry, I visited news sites (that part’s still weird to me), I worked out, I made eye contact and smiled at people when I encountered them in elevators and on the street. I kept my head up. After nearly four weeks, my attention span became something it hadn’t been in ages, something iron and concrete and unlike the fluttering moth that it had been in recent years. And that was when I started doing something I hadn’t done in ages: I started writing again.

I missed a lot, too. I didn’t realize that John McCain had died until my beloved told me, because I hadn’t read the news that day. I missed the announcement of the birth of several of my friends’ babies. I missed notification after notification. My brain felt like a new and limber thing, but I also felt strangely disconnected, and I wondered if the two things were inherently related.

On Saturday, the social media-free month complete, I went back to Twitter with trepidation.

“I’m afraid of going back to exactly where I was,” I told my husband. Back to being unproductive and unable to write and the moth-like-attention-span. He suggested I set a timer and give myself ten minutes on the site. I did so, but made it through only a few days’ worth of my replies, amazed at how the time sped by.

Nice to see that things hadn’t changed while I was away.

After some deliberation, I kept going for another 15 minutes, caught up with all my replies, and sent a few tweets out.

I left the site. But then I felt the tug again, wondering who’d replied, wondering who’d retweeted me. That’s the problem – the nature of social media is a call and response, one that never offers a last word. Today, just 24 hours after my hiatus has ended, I found myself ready to pen a series of tweets about how online abuse is real abuse to someone who told me that I had never experienced the real thing. I stopped. Instead, I wrote it all down in a document that I’ll send to my agent.

July 30, 2018

What Happened When I Tried Talking to Twitter Abusers

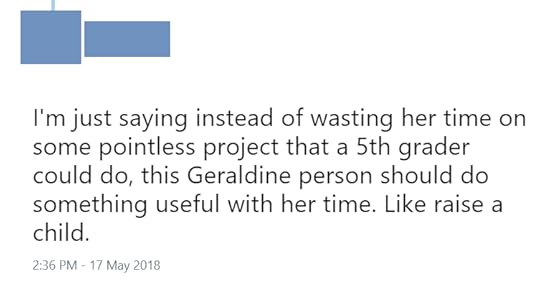

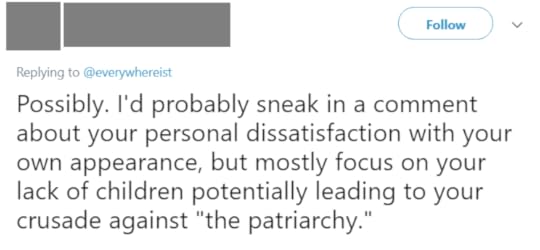

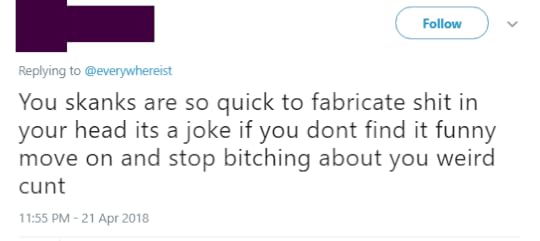

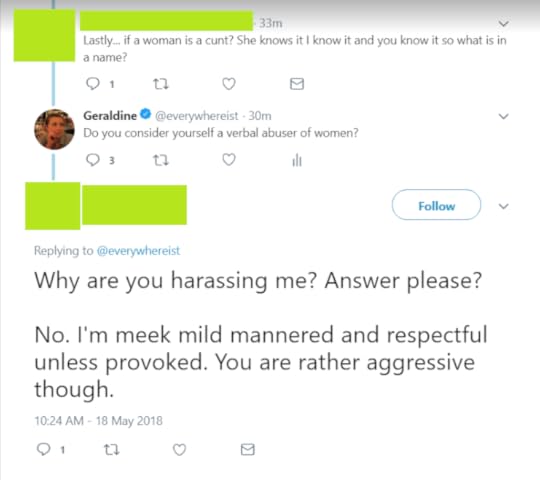

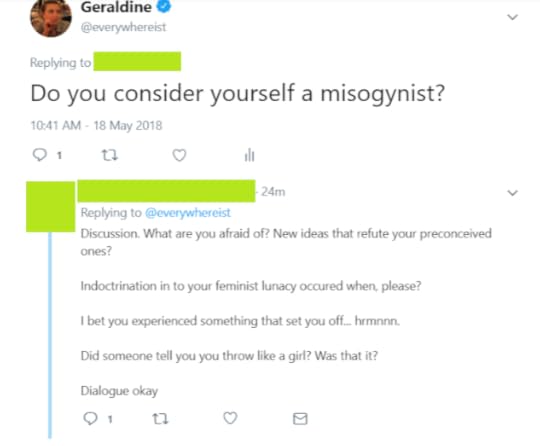

Trigger warning: please note that this is a blog post about online abuse, and includes screen caps of tweets sent to me. Graphic threats and abusive, hateful language toward women appear therein.

A few weeks ago, I gave a keynote talk at World Domination Summit in Portland. The thesis: while we regard online misogyny and abuse of women as something wholly separate and different from its so-called “real-world” counterparts, these are all components of the same system. We dismiss sexual harassment that happens on the internet in the exact same way that we dismiss sexual harassment that happens face-to-face, even though these experiences are often just as bad – if not worse – for the victim, often due to the mechanics of the anonymity of the internet.

Women – both online and off – are told that we are overreacting, that we brought this abuse upon ourselves, that we can just leave the platform or get a new job, that the threats aren’t real, and a litany of other arguments meant to cause us to question our own realities and experiences. Teach a woman that she can’t trust herself and she becomes infinitely easier to abuse. Those of us who do speak up are labeled difficult, humorless, shrill, caustic; not only are women mistreated, but a system is in place to ensure that they can’t call out that abuse without doing more damage to themselves.

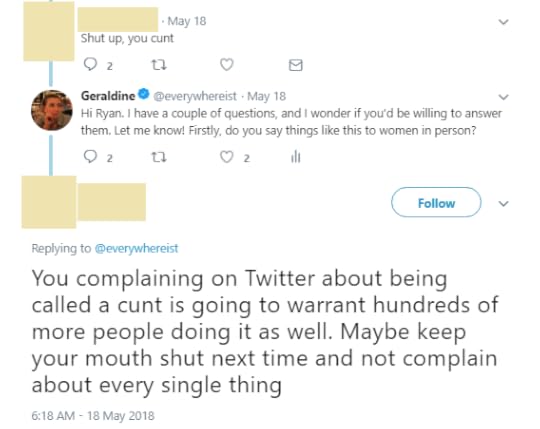

I can give talks to large crowds – I just spend way too much time preparing for them; this was no exception. For months leading up to the talk, I frantically worked on slides, I created and scrapped outline after outline, I poured through academic journals, and – most harrowing of all – I spent time talking to online abusers on Twitter.

It was illuminating, though perhaps not for the reasons one would think. There was no common ground reached, no epiphanies that we were all just people with different views. Quite the opposite, really: I realized that these individuals did not and would not care about my feelings, no matter how long we talked.

As I told the audience of WDS, I do not recommend this exercise. “Don’t feed the trolls” is an oft-quoted refrain whenever online abuse comes up, but it is far too simple, and as the (anonymous) writer of this brilliant piece notes, it is hardly effective. We now are so disinclined to feed “trolls” (a term that I reject in this instance – these are abusers, pure and simple, not trolls) that we’ve created a strange system where we don’t even acknowledge the pain of their victims, or, if we are the victims, where we fail to acknowledge the pain that they have caused us. But the root of the argument holds true: online abusers feed off attention and the knowledge that they’ve caused their victims pain.

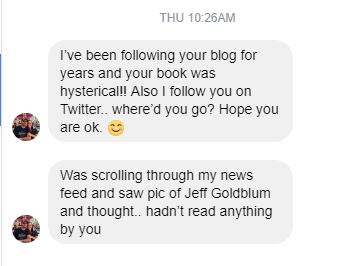

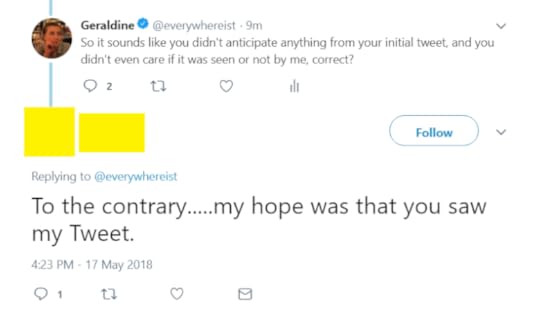

This individual noted that they had no ideal outcome in mind for their tweet – they just wanted to be sure I saw it.

One tactic I’ve often seen people take (which I’ve also tried) is to reason with online attackers, to make them acutely aware of the fact that there is a human at the other end of their attacks to whom they are causing pain. This rarely works because, as one study found, individuals who were more likely to engage in “trolling” behaviors were more likely to have psychopathic and sadistic traits. By telling them about the pain they were experiencing, their victims had given the trolls precisely what they wanted.

I realized I had to tread carefully – I needed to not get upset by their words (or if I did, not let it show), and not give them any kind of reaction they might find gratifying. Fighting back, making arguments, disagreeing – all of this would simply feed into their goals or incite their wrath. Instead I found myself almost numbly engaging them, in the way I do with volatile people I’ve encountered in real life. Anyone who argues that online abuse feels different than in-person abuse is kidding themselves.

The vast majority of my interactions were frustrating. Some didn’t reply at all, or disappeared instantly the moment I engaged them – blocking me, even though they were the ones who had attacked me initially.

With others, it was like trying to converse with a piercing alarm. Once they realized a live human being had seen their initial tweet, they unleashed a torrent of insults, in a sort of frenzied, rapid-fire slew of hate and misogyny. This wasn’t about conversation. This wasn’t about intelligent debate. This wasn’t even really about me. This was about unleashing all of the hate they’d accrued for women over the years.

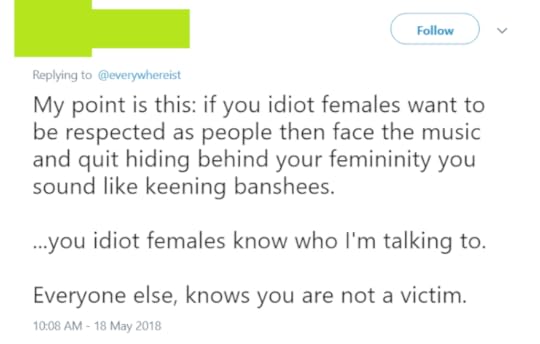

Like, what is this guy even talking about? WHO IS HE TALKING TO? Because I don’t think this had to do with me.

I also learned – rather quickly, though not quickly enough – to only engage people in my mentions. I had started trying to talk to people who were harassing my friends or prominent women, but soon found that my engagement galvanized their hate against their initial target. The safer option was to talk to my own abusers, ensuring that I would be the recipient of such a reaction. (I’m a white, able-bodied, cis-gendered woman. There’s a lot of privilege that comes with that.)

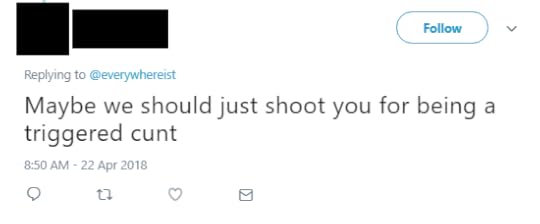

It should be noted that the people I chose to speak to were not the authors of the most vitriolic hate in my mentions. At the request of several people who care about my well-being, I didn’t speak to anyone who’d threatened anything too graphic or terrifying. For example, per Rand’s request, I didn’t talk to this guy:

I reported this to Twitter. They made him delete the tweet but his account is still active.

–

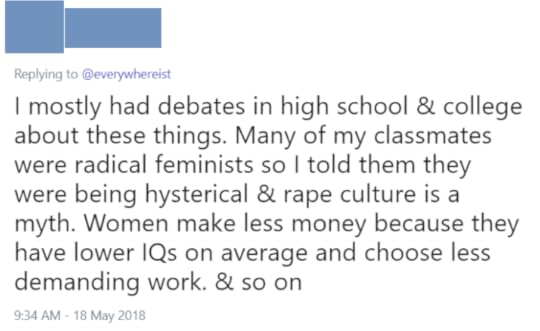

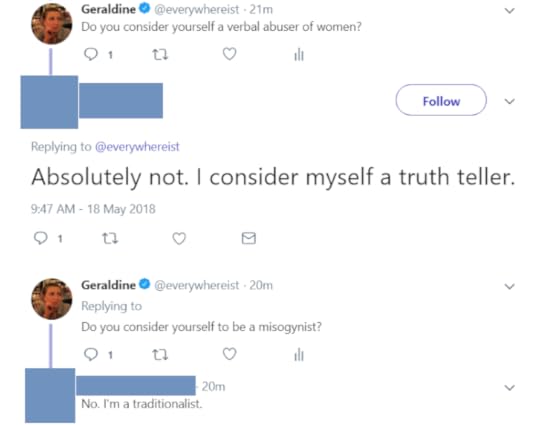

And after more than a dozen of these conversations, I found some commonalities with the individuals I spoke to.

None of these people considered themselves misogynists. I asked them directly, and the responses to this (and to whether or not they considered themselves to be abusers) was a resounding “no.” Many of them made arguments that they treated men and women equally (something that they repeated to me ad nauseum, along with, rather inexplicably, their military service, and the fact that they were fathers). One guy told me that he wasn’t a misogynist or an abuser of women, and literally three minutes later he tweeted this to a woman (in purple below) who called him out:

–

–While this level of cognitive dissonance is jarring, it’s not that unusual when it comes to how people regard their own hateful beliefs. Think about many times someone has been caught on video verbally abusing a person of color, only to immediately release a statement saying, “I am not a racist.” Because the sort of self-scrutiny that allows a person to see their own capacity for hate usually also means they are working on that hate.

–

They later doubled-down on the sexist insults. When I asked them about their behavior, almost all of these individuals immediately got defensive, tried to obfuscate the issue, and when none of that worked, they doubled down on their attacks. And the way in which they did so revealed that their initial sexist or misogynist tweet to me was probably not a fluke. I was told that I’d turned to feminism because of some pitiful insult that I couldn’t handle (like someone had told me that I “threw like a girl” – thereby mitigating the scope of sexism that women deal with every day and framing feminism as something reactionary and vengeful), that I was profoundly unhappy with how I looked, that I was angry at men and if only I’d had a couple of children, all of that would change.

–

– And lest anyone forget, they are not misogynists:

And lest anyone forget, they are not misogynists: –

–According to them, all of this was my fault. I was told repeatedly that my choice to be vocal on issues of politics and feminism opened me up to the bevy of insults that I’d received, and if I hadn’t chosen to talk about those issues, then this wouldn’t have happened. I’d expressed my views in a public forum, and now I couldn’t handle a little criticism that resulted from that.

This guy has called women the c-word and the b-word, sent a photo of a crack pipe to a black woman whose views he disagreed with, regularly threatens people on Twitter, and has since blocked me. But apparently he is not abusive and I am thin-skinned.

–

The thing is, as a writer, I can handle criticism. Most writers can, because (and many of us will tell you this) even the most scathing Kirkus review isn’t quite as awful as what goes on in our heads.

–

But this isn’t criticism:

Telling a woman that she’s ugly and repellent and that she holds her beliefs because she’s angry that she’s barren doesn’t actually indict or refute her arguments in any way. It doesn’t create a dialogue. It’s just designed to silence women they disagree with, and doing that doesn’t mean that they’ve won the debate or proved their point. That isn’t criticism or debate. It’s just abuse.

–

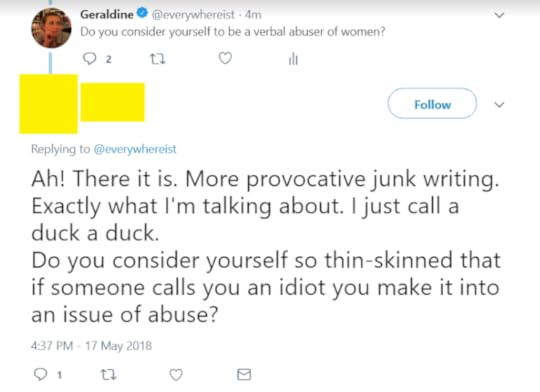

This wasn’t harassment; I’m just too sensitive. As I noted above, women who call out harassment are often told that their situation isn’t abusive or problematic – they’re just perceiving it the wrong way. It’s gaslighting at it’s finest, because it means that victims often don’t even realize that we’re victims – we’re just left feeling terrible, and wondering how or why we provoked the reaction that we did. Because women are so often blamed for their own harassment, and those that speak out against it are often vilified more than their harassers, most of this abuse goes unreported. What’s amazing is to be told that we’re fabricating sexism and abuse by people who, in that very same breath, abuse us. –

–

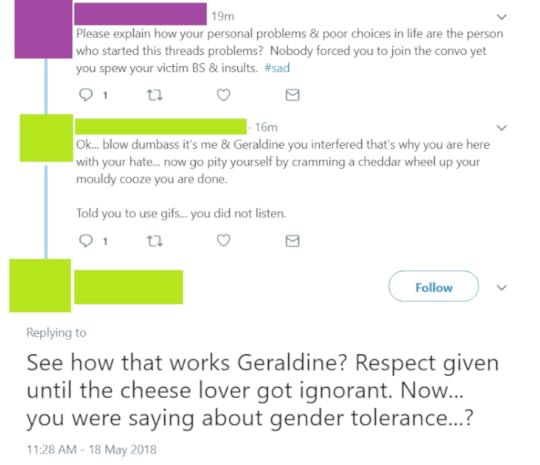

They accused me of harassing them. As I noted above, I didn’t fight back or disagree once the individuals agreed to talk to me. But when they strayed from the questions, or failed to answer them, I steered them back to my initial query, and I suspect that even that sort of minimal pushback was new to them (most abusers aren’t used to any sort of resistance). They’d agreed to answer a couple of questions from me, but once those questions made them uncomfortable, they became really, really angry. They asked me why I wasn’t answering their questions (more on that below), and became hostile.

This dude used the c-word repeatedly (claiming it wasn’t a bigger insult than calling a woman “a smelly bag of potatoes”, told a woman to violate herself with a cheese wheel (see above) and then said I was harassing him for asking this question.

–

This was about power. I suppose I should have realized from the start that anyone who appears in your Twitter mentions to tell you that you’re fat, ugly, old and barren (“Who among us is NOT?” is my unanswerable reply) isn’t trying to have a conversation. They are simply trying to chase you off the platform, so your voice won’t be heard anymore. This dynamic became so apparent that I was actually able to predict when they would double-down on their insults, based on when I felt the power dynamic shift. A large number of them, perhaps in some effort to save face and regain a semblance of control, told me how excited they were about the project. Others tried to turn the tables on me, and tried asking me questions (most of them of the same insulting nature – asking who radicalized me to feminism, etc.).

(This was the same guy who accused me of harassing him above.)

Because their attempts to push me out of the space had failed, they were trying to gain control in another way. And when that, too, failed, they either turned to more insults, dismissed me, or blocked me.

—————

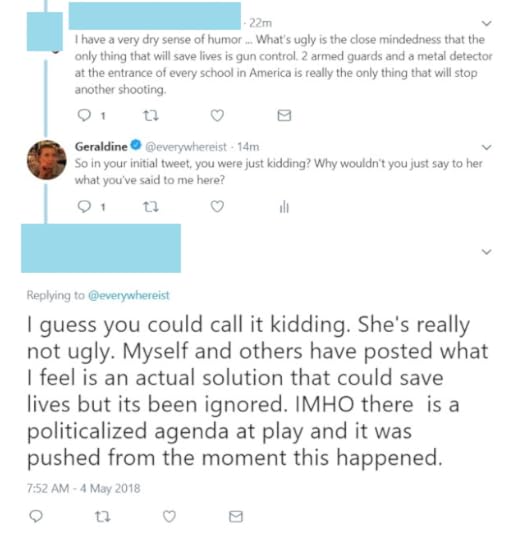

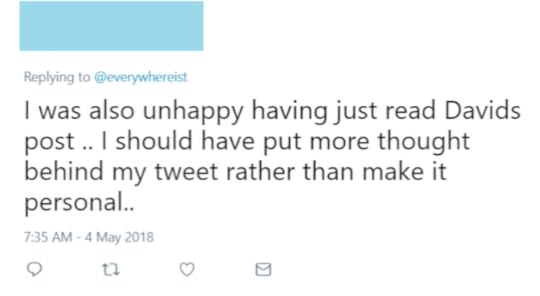

Since this experiment took place, many of the accounts I interacted with have been permanently suspended. Most of the others have blocked me after the fact (remember: I was simply asking them questions which they agreed to answer after they had initially insulted me. But that sort of thing can be scary, I guess.) Of all the conversations I had, exactly one left me feeling a modicum of hope. It was short lived. The individual I was talking to had been leaving insulting replies in Emma Gonzalez’s Twitter feed (this was before I realized I should probably only be engaging my own haters). Many of his comments included references to how ugly she was, and when I asked him about it, he seemed pretty embarrassed. He noted that she wasn’t actually ugly.

–

And that his personal attacks were not the best approach.

–

–

And while we disagree hugely on the gun control issue, I felt like our discussion made him realize that attacking a young woman who’d survived a mass shooting while at school was perhaps not conducive to his goals. I left our exchange feeling a little … optimistic?

Today, I checked his Twitter feed.

It’s a bunch of personal, vicious attacks about her appearance directed at her.

So, yeah.

–

There’s a lot of discussion about how we need to reach out and talk to people who disagree with us – how we need to extend an olive branch and find common ground – and that’s a lovely sentiment, but in order for that to work, the other party needs to be … well, not a raging asshole. Insisting that people continue to reach out to their abusers in hopes that they will change suggests that the abuse is somehow in the victim’s hands to control. This puts a ridiculously unfair onus on marginalized groups – in particular, women of color, who are the group most likely to be harassed online. (For more on this topic, read about how Ijeoma Oluo spent a day replying to the racists in her feed with MLK quotes – and after enduring hideous insults and threats, she finally got exactly one apology from a 14-year-old kid. People later pointed to the exercise as proof that victims of racism just need to try harder to get white people to like them. Which is some serious bullshit.)

I spent days trying to talk to the people in my mentions who insulted and attacked me. I’d have been better off just remembering that when someone shows you who they are, believe them the first tweet.

July 19, 2018

Lost And Founder.

My beloved wrote a book.

How it came to be was radically different from my own path. When I wrote a book, it became a job, it became the thing I was doing because on a daily basis, there’s not that much else that is asked of me. But there are always things asked of Rand, and I watched him write this book in stolen moments between a thousand other obligations.

I would ask him if he had plans for the weekend, and he’d reply that he had to get two chapters done by Sunday evening. I stared at him, mouth agape. I didn’t understand. I still don’t. But that is the nature of my husband. Give him any measure of time – a scrap of it, a spare moment, a half hour uninterrupted and left to his computer, and he will make something great. Give him several measures of time, and that great thing will be a book.

It is called Lost And Founder and it is part-memoir, part-cautionary entrepreneurial tale, part-startup guidebook.

It’s been fun to be on the other side of things, to sit in the crowd and listen as Rand reads from his book, to see friends as well as strangers stand in line, waiting for him to sign their copies. To hear him answer the questions his moderators and the audience asked of him. To finally – after being the recipient of so much good advice from the love of my life – be able to offer a small measure of it in return.

“Read every excerpt beforehand to yourself,” I said.

“But I’ve already done that. I recorded the audiobook.”

“Trust me,” I told him. And as we sat at the dining room table, Rand read a few paragraphs about when he found out about my brain tumor. And even though it was years ago – firmly cemented in the past so that months go by and we don’t even think about it – he broke down. He looked up at me, stunned, as if I had an answer to what was happening.

I shrugged.

“It’s just what happens when you read something aloud in front of someone else,” I explained. I had learned this when preparing for my own reading: a couple of lines into certain chapters about loss and love, and I found myself crying. But after reading it a few times, the tears exorcised themselves.

The read-through technique worked much the same for Rand. By the time he read for the crowd in Seattle, he was fine. Actually, he was great.

[image error]

Was he heckled by an audience member for his excessive handsomeness? Yes, yes he was. (I regret nothing.)

I kept telling him this is way too much to write in anyone’s book and he keeps ignoring me.

[image error]

“Rand, first question: are those leather pants?” – our friend Glenn, who is a ruthless interviewer. (No, no they are not.)

For his New York reading, we had a car pick up his grandparents in Jersey and drive them into the city. The room was packed. The bookstore supplying copies for the event sold out of Rand’s book.

My photos are blurry because I sat high atop some bleachers with some dear friends in the back. Both Rand and Mike, our friend who moderated, were brilliant, and yes, I am biased, but it’s still true, damn it.

[image error]

Afterwards, my husband’s grandparents, now firmly in their 90s, walked through the streets of New York with us – streets where they had grown up – and told my husband how proud they were of him.

Later, I would ask him if getting a book published was the realization of a lifelong goal.

“No,” he said, “it’s the realization of a two-year long goal.”

I love him dearly. And so I resisted the urge to hurl a hardcover copy of his 2-year-long-goal at him. But that, I realize, is how he operates – these accomplishments of his – these things which I think are unquestionably incredible – are not the apotheosis of his career. He’s still searching for what that is. In the meantime, he finishes projects in those spare pockets of time he has. And sometimes, those projects are a really wonderful book.

June 22, 2018

Scenes From a Bookstore

“Why do they have so many copies of my book? Is that a bad sign? Does that mean no one’s buying it?”

“No. Your book has been out for a year, and they have a lot of copies. That’s a good sign. That means they keep it in stock.”

“Are you sure? Because doesn’t it mean that no one’s buy them-”

“No. It’s a good sign. They restocked them. They’re selling for full price. This is good.”

“Yeah?”

“Yeah.”

It’s still a surreal thing to see my book in bookstores. I don’t really process it as something I’ve written. It’s more like when you see something that you own that you haven’t made – like a shirt or a mug or a lamp – in a store, and you think, “Hey! I have that at home!” It’s just a neat little coincidence. It’s certainly not enough affirmation of your career to counteract the lifetime of self-doubt that you’ve managed to accumulate.

Ahem.

And now recently, I’ve had the added privilege of seeing my beloved’s book on bookstore shelves, too:

But this deserves its own post.

While down in Portland last week, Rand and I stopped into Powell’s, where I had the slightly-less-awkward-now-than-it-was-the-first-dozen-times-I-did-it privilege of explaining to the staff that I wrote this particular book and would it be okay if I signed a couple copies? I’ve found that the people who work in bookstores – both independent ones and big chains – are always incredibly grateful and obliging when you ask this. And you know those “Autographed” stickers that you see on the cover of signed books? They always have those on hand, and as soon as you’re done signing your book, they slap one of those on the cover. It’s … well, it’s really fun. I need to remind myself of that, because sometimes I forget to take the time and really enjoy those moments.

[image error]

At some point, as I was signing books at Powell’s, I looked up and caught Rand taking photos of me.

[image error]

He captured the exact moment I realized what he was doing.

[image error]

Until I spotted him with his phone out, I hadn’t considered that what was happening might be a photo-worthy event.

I mean, it was just me standing there.

In one of my favorite bookstores.

Signing copies of my memoir.

Of which they had plenty in stock.

It’s really easy for me to lose perspective on how great my life is. Luckily, I have someone who is always reminding me.

June 21, 2018

782 Words About Writer’s Block

I don’t know what writer’s block looks like for other people. I’ve never discussed it with my friends who write professionally, perhaps because it seems like a silly, self-indulgent think to talk about.

“Hello, friends who also make a living making sentences. Do you know how sometimes the sentences are hard to make? How putting words together … don’t happen good?”

How do you talk about not being able to express ideas? It always feels like you’re cursing yourself – like writer’s block wasn’t really writer’s block if you didn’t give it a name, but once you utter those words it’s like an incantation to the heavens to turn your brain into pudding and suddenly make you want to click on all those spammy links at the end of an article.

“Why, yes, I do want to know what the cast of Head of The Class looks like now! Thank you for asking!”

And just like that, you’ve been sitting at your computer for a thousand years and you’ve written three words.

(Those three words aren’t good.)

TV and movies would have you think that writer’s block involves you endeavoring to write but being unable to do so. That’s never been the case for me. For me, writer’s block means I don’t even endeavor to write. It’s not writer’s block. It’s writer’s … distraction. I know the discomfort of staring at a blank screen, trying to will words out, and so I avoid it altogether. I buy shoes. I spend endless hours on Twitter. I have such terrible posture that I give myself the sort of headache that could fell a lion because I’m sitting back and clicking a mouse and physically trying to move as far away from my keyboard as possible while still sitting at my desk.

I’ve always had spates of this – days or weeks where I had the attention span of a moth, publishing nothing save for the occasional insipid, boring post. But insipid and boring is better than nothing. Because at least I was writing. For the last few months – arguably for the last few years – I haven’t really been doing much of that.

I try to pinpoint the cause of things. I wonder if it was my dad dying. I wonder if it’s just the malaise that surrounds publishing your first book – a sort of strange career crisis that has you wondering what they hell you are going to do next. How do you follow up the realization of a lifelong goal? How do you explain to people that the realization of that goal, while wonderful, never erased that constant gnawing feeling that you have in the pit of your stomach every time you think about your writing career?

Or maybe I don’t feel like writing because the weight of the never-ending dystopian nightmare that is our news cycle is starting to – I don’t know – kill my soul? That excuse feels equal parts reasonable and overly indulgent.

I’m too distressed to write! sounds like the pinnacle of privilege.

And it’s a pointless realization, anyway. Once you’ve identified why you are unable to write, the problem doesn’t magically go away. You’re just left with a problem, and its suspected cause. That doesn’t mean you can solve it.

I can’t write. Because I’m sad. And distracted. And I miss my dad. And the news is awful. And I don’t feel like writing.

See? There’s no real solution there.

The tipping point for me is this: eventually, the discomfort of not writing exceeds the discomfort of writing. And when that happens, I come back to it. But it’s like working out a muscle: the longer you’ve been away, the harder it is. And I’ve been away for a very long time.

Right now, the act of writing makes me deeply uncomfortable. My leg hurts from sitting at my computer for too long. My left butt cheek is asleep. But writing is also a gift.

I wonder what it means to have to your child taken from you when you are simply trying to come to America to make a better life for yourself. I think about how my grandmother did that when she fled Ukraine with my dad and uncle (and then got stuck in Nazi Germany for a while) before she made it to the states.

My grandmother with my uncle (left) and my dad (right) circa 1950 in New York.

I constantly feel like I’m going to cry. I don’t know what to do with myself.

So I sit down in my safe little office in my safe little corner of the world, and I start typing. It’s deeply uncomfortable. But I just hit the point where not writing is even worse.