Tim Patrick's Blog, page 12

November 28, 2016

Should Donald Trump’s Sins be Forgiven?

The election of Donald Trump as president stirred up a fair bit of controversy. Part of the chatter stems from lewd comments he made back in 2005, as revealed in an October surprise video by The Washington Post. Detractors insist not only that the comments indicate a callous disregard by the president-elect toward women, but that they make him unfit to be our forty-fifth president.

There is little doubt that the inappropriate comments Trump made amounted to overt womanizing. And the condemnations of his behavior were not limited to Democratic sources. Republican Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell called the president-elect’s words “repugnant,” and insisted that Trump apologize. Others in the GOP, including Representative Mike Coffman of Colorado and former campaign rival Carly Fiorina, called for Trump to abandon his presidential run. Although candidate Trump issued a public apology soon after the video appeared, the ongoing denunciations were harsh and long-lasting. But should his behavior be forgiven? Should his statements from more than a decade ago be left in the past? Would Democrats and others who object to Trump in general just let his comments go?

I doubt it. It’s not because Donald Trump is unique among politicians in being overly male toward women. Ted Kennedy ran as a Democratic presidential contender in 1980, just a decade beyond his mysterious Chappaquiddick car accident that resulted in the death of a female passenger, Mary Jo Kopechne. Jimmy Carter admitted in an interview with Playboy that he had “committed adultery in my heart many times,” although at the time his willingness to sit down for that interview with a magazine that exploited women overshadowed anything he said. And of course, there’s Bill Clinton’s famous extramarital affair that took place right in the White House.

For the most part, Democrats have let bygones be bygones for those in their own fold. Sadly, that benevolence doesn’t extend to those who have differing political views. While Democrats were willing to overlook active philandering by members of their own party, I fully expect that the videotaped comments of Trump’s foul mouth will once again be a key anti-Republican campaign tactic four years from now. Prominent Democrats will never forgive Donald Trump for what he said, not because there is a core concern for individual targets of Trump’s lust, but because they love left-wing policies more than anything else.

If you require evidence for that blunt statement, consider the response to the death of former Cuban President Fidel Castro, someone who considered left-wing views to be a badge of honor. Since he first assumed power in 1959, Castro ran Cuba as a typical Communist dictatorship: collectivist in its policies, brutal to its perceived enemies, and unforgiving of dissenters. While his reign was not as violent as those in Russia and China, his government nonetheless adhered to harsh totalitarian dictates, with Human Rights Watch calling Cuba under Castro a “repressive system that punished virtually all forms of dissent,” one where “thousands of Cubans were incarcerated in abysmal prisons, thousands more were harassed and intimidated, and entire generations were denied basic political freedoms.” Castro tortured political prisoners, sent gays and religious minorities to reeducation camps, and declared that he would be a Marxist-Leninist “until the end of my life.”

None of these abuses came up during President Obama’s statement on Castro’s passing. While a message of condolence is not the best forum in which to detail past sins, Obama’s mention of “the countless ways in which Fidel Castro altered the course of individual lives, families, and of the Cuban nation” represents the harshest criticism you will find there for a man who disrupted or destroyed the lives of millions of his citizens. Jesse Jackson, himself a former Democratic presidential candidate, said of the Cuban dictator, “In many ways, after 1959, the oppressed the world over joined Castro’s cause of fighting for freedom and liberation—he changed the world.”

Democrats have forgiven Fidel Castro for all of his sins, not because they witnessed contrition, but because of political simpatico with the island dictator. For his penance, he raised the literacy level in Cuba and provided a semblance of universal healthcare. For these Democrats, absolution is just a single-payer program away, even from those who have caused untold human suffering.

Of course, Republicans are not immune to such double standards. The endless string of Ken Starr-led investigations into the minutia of Bill Clinton’s inner circle back in the 1990s represented a political proctology exam of embarrassing proportions. That the GOP was more than willing to reactivate that witch hunt through modern email-server technology shows that they, too, take a certain glee in withholding political forgiveness from their enemies.

Pardoning the sins of those you love while crucifying your opponents for those same transgressions is not only duplicitous, it is dangerous for the country. By tying political success to the downfall of specific officials, we delude ourselves into thinking that we have actually achieved a political victory, or buttressed the philosophical basis for our beliefs. In reality, we’ve only succeeded in making buffoons of ourselves, while simultaneously allowing those who crave political power to move us one step closer to tyranny.

There is no virtue in offering or withholding forgiveness for the sake of political expediency. If we’re honest with ourselves, we know that Bill Clinton’s 1990s marital affair and subsequent perjury was much worse than Trump’s decade-old libidinous braggadocio. If you found the spiritual fortitude to extend grace and forgiveness to Bill Clinton, then for the good of the country and for your own peace of mind, it’s time to forgive Donald Trump.

[Image Credits: NBC]

November 21, 2016

Deceptive Claims about Racism Mainly Hurt Minorities

If the post-election hubbub has taught us anything, it’s that making accusations about someone’s racial views, even if unfounded, has a devastating impact. If you’re like me, your Facebook feed over the past two weeks has included a sewer line of posts on how heartless, how bigoted, and ultimately how evil Trump voters are. In almost every case, such accusations are built upon nothing but lies, guilt by association, and innuendo.

According to recent numbers, around 61.2 million voters opted for Donald Trump, voters whom we are assured are among the most racist, backward, and vile people on the face of the planet. America as a whole has about 231.5 million eligible voters, which means that one out of four grown-ups in the United States voted for Trump, a number that includes twenty percent of Asian and Hispanic voters, and nearly a tenth of black voters. A quarter of your neighbors, your co-workers, and those you encounter in your everyday business dealings voted for him. Since around ninety million people didn’t bother to vote, you could perhaps extrapolate the percentage up to forty percent of Americans who are supposed bigots. And yet, you would be hard-pressed to identify even one percent of your acquaintances who exude even the tiniest hint of actual racist inclination.

The falsehoods surrounding the assumed hatred by Trump voters has certainly ruined a lot of personal relationships. But the harm that these kinds of lies bring to the African-American community is worse. Consider, as an example, the claim that incarceration rates for African-American men are out of proportion to the overall black population in America, primarily due to blatant racism. According to a report released earlier this year by The Sentencing Project, African-Americans are incarcerated at 5.1 times the rate of whites. The report’s conclusions listed racial bias and structural factors that work against blacks as some of the key reasons for the high rates of imprisonment.

If you think only about the raw numbers, it is true that African-Americans, especially young men, are sent to prison at much higher rates than you would expect just from the demographic makeup of the nation. Blacks—both African-Americans and those newly arrived from non-African nations—comprise just over twelve percent of the US population. But according to the Federal Bureau of Prisons, that group accounts for 37.8 percent of all inmates. That’s triple the national breakdown, and it’s only natural to think that racism must be the key factor in the disparity. But that’s not the case, something that we know from the dearth of incarcerated women.

At 50.9 percent of the population, females are the majority gender the United States. And yet, only 6.7 percent of prisoners are women. Despite this divergence, nobody is marching in the streets demanding that the criminal justice system end its vile sexist practices, or that the majority female population finally come to terms with its abusive prejudice.

We take it for granted that prisons will be filled mostly with men. It’s not because we are all closet misandrists. It’s because men commit crimes at higher rates than do women. Males are more likely than women to commit crimes of all types, especially violent crimes. Young men are particularly adept at engaging in criminal behavior, and the presence of such youth behind bars comes as a shock to nobody.

Perhaps we could adjust our criminal justice system so that the rate of male prisoners was more in line with the overall population. But that would be a moral wrong, because the rate of inmates is supposed to be a reflection of the population that commits crimes, not of the general population. If men commit ninety percent of all crimes, then the prison population should reflect that, even though men comprise only about half of the overall US population.

In the same way, if 38.7 percent of all crimes in America are committed by African-Americans, then a prison population that was 38.7 percent black would accurately reflect the nature of criminal behavior in the country. This would be the case even if blacks were only two percent of the country, or ninety-two percent. The racial makeup of the nation as a whole is not immediately relevant to calculations of prison populations.

To determine if blacks are properly represented in prisons, it is necessary to determine the percent of crimes that that particular racial group commits. Such numbers are hard to come by, as they would naturally exclude those who had not yet been apprehended, arrested, or convicted, and might be skewed by the incorrect perceptions of victims. The Bureau of Justice Statistics attempts to track such numbers through interviews with victims, but the most recent data they make available are from 2006. In that report, (“Percent distribution of multiple-offender victimizations, by type of crime and perceived race of offenders,” see Table 46), which is limited to violent crimes, victims indicated that the perceived offender was black thirty-three percent of the time. While that number is still somewhat different from the overall inmate rate, it is a lot closer than the twelve-percent national African-American population.

Of course, if blacks are committing a disproportionate number of America’s crimes, it is important to ask why that is the case. It is certainly possible that racism plays a role in guiding these minorities into a life of crime, or in ensuring that they receive convictions. And that nearly six-percent gap between the rate of perceived offenders (33%) and actual prisoners (38.7%) is troubling. But by highlighting the disparity between prison populations and the overall population, and insisting that it’s almost entirely the result of white racism, advocates of minority rights have done little to alleviate the suffering of minority communities. Instead, their biggest impacts seem to be the fanning of race-based flames between whites and communities of color, and the scoring of points against their political opponents.

Crying “racist” every time anything happens that involves a minority is a great way to embitter the majority population, but it does nothing to identify or resolve the true causes of race-based disparities. Despite all of the accusations against whites, blacks continue to be the largest group proportionally of victims of crimes committed by African-American perpetrators. Issuing blanket condemnations of white privilege might make accusers feel good about their moral positions, but the only thing it provides to affected minority communities is a sense of rage, and rage is a useless skill when it comes to finding a job, raising a family, or solving societal problems.

America has had its share of racial disappointments, both at its founding, and more recently through acts such as Japanese Internment during World War II. The residue from that history is real. But it is possible to discuss and address that residue without resorting to statistical distortions and lies. Until we are willing to discuss our societal problems honestly, people will continue to get hurt, especially those in marginalized communities.

[Image Credits: State of New York Department of Corrections]

November 18, 2016

VSM: Tricks with Goto in Visual Basic and C#

The Goto statement is often accused of creating spaghetti code. If you are a fan of Italian food, that might not seem so bad. But the misuse of this otherwise low-impact statement can reduce the maintainability of your application.

Goto tells your code to jump immediately from Point A to Point B. But there are limits to where you can jump, and you would be jumping to conclusions if you expected C# and Visual Basic to have the same limits. To discover some of these differences, jump on over to my latest Visual Studio Magazine article, “Tricks with Goto in Visual Basic and C#.”

[Image Credits: Visual Studio Magazine]

November 16, 2016

The Pre-Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence has such a foundational place in American thought that it appears to have dropped, fully formed, directly from heaven, or at least from the mind of Thomas Jefferson. But most of its ideas drew upon earlier writings from Enlightenment authors, from other revolutionary thinkers, and even from a younger Thomas Jefferson.

The year was 1774, King George III was on the throne, and America was not happy. For most of the previous decade, Parliament had imposed an ever-expanding array of taxes and restrictions on colonial citizens, businesses, and regional legislatures. But the Intolerable Acts, passed throughout 1774 in direct response to the Boston Tea Party, proved too much for the Colonies to bear. In late 1774, they came together as the First Continental Congress in order to present a united appeal to King George himself. Jefferson, still a relatively unknown member of the Virginia House of Burgesses, crafted “A Summary View of the Rights of British America,” and provided it to the Continental Congress as a starting point for their written appeal.

Although it was written nearly two full years before the Declaration, “Summary View” includes many of the ideas and specific grievances that made their way into the later document, including the concept of rights granted by “the God who gave us life [and] liberty.” The language, though tame when compared to the text of the Declaration, is nonetheless clear, direct, and ultimately offensive to those in the king’s court.

Jefferson’s “Summary View” declares that the colonists, by right of their God and of their Saxon lineage, are the direct and ultimate owners of colonial lands, and are thereby empowered to manage their own legislative and international affairs without interference from the British parliament, or even from the king, who “is no more than the chief officer of the people.” Instead of respecting “those rights which God and the laws have given equally and independently to all,” Britain engaged in “unwarranted encroachments and usurpations” that violated the natural and constitutional rights of the American colonists. Although the words vary, expressions such as “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights,” “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness,” “consent of the governed,” and “a long train of abuses and usurpations” are only a hairsbreadth away from the ideas found in “Summary View.”

“The true ground on which we declare these acts void is, that the British parliament has no right to exercise authority over us.”

— Thomas Jefferson

Many of the specific indictments found in the Declaration of Independence appear first in “Summary View,” and in greater detail. In the earlier document, Jefferson mentions how “his majesty possesses the power of refusing to pass into a law any bill which has already passed the other two branches of the legislature.” The document expends much ink in describing the constitutional background from which the king derives this power, and the situations in which the king might enjoy this negative power, all before accusing the king of abusing the power “for the most trifling reasons, and sometimes for no conceivable reason at all.” Two years later, Jefferson condenses this lengthy explanation down into something blunter: “He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.”

The Declaration also documents how King George “has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness of his invasions on the rights of the people.” The “Summary View” expands on this complaint, listing the specific example of New York, and how “one free and independent legislature hereby takes upon itself to suspend the powers of another, free and independent as itself; thus exhibiting a phenomenon unknown in nature, the creator and creature of its own power.”

The overall number of abuses documented in “A Summary View” is limited by Declaration standards. But Jefferson says that they are sufficient, and that “single acts of tyranny may be ascribed to the accidental opinion of a day; but a series of oppressions, begun at a distinguished period, and pursued unalterably through every change of ministers, too plainly prove a deliberate and systematical plan of reducing us to slavery.” This appeal to slavery is significant, and Jefferson, though himself a slave owner, lays the blame for continued colonial slavery at the feet of King George: “The abolition of domestic slavery is the great object of desire in those colonies, where it was unhappily introduced in their infant state. But previous to the enfranchisement of the slaves we have, it is necessary to exclude all further importations from Africa; yet our repeated attempts to effect this by prohibitions, and by imposing duties which might amount to a prohibition, have been hitherto defeated by his majesty’s negative [ability to refuse his Assent to Laws].”

At nearly 7,000 words, “A Summary View of the Rights of British America” is a long read when compared Jefferson’s more well-known 1776 statement. But it nonetheless provides an essential background into the meanings and purposes of the ideas found in the Declaration of Independence. Here in our century, when so many have lost the ability to articulate or even understand the causes for which we felt compelled to invoke our right to independence, reading the primary thoughts of the founders is more important than ever.

You can obtain “A Summary View of the Rights of British America” from various online sources, including from history.org, the web site for The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

November 14, 2016

Is America a Racist Nation?

The inauguration of Barack Obama eight years ago, trumpeted as the final proof that our slave-embracing past had been put behind us, did not usher in a new era of racial harmony. Every month, it seems, the news media is awash with stories of racial discord, culminating in recent post-election stories of whites acting poorly toward non-whites. Many commentators insist that ours is still a racist country, and that the elevation of Donald Trump to president-elect has released pent-up bigotry. But is it true? If the United States still a racist nation?

To answer that question, we first need to define what it means to be a racist nation. While each viral video of racial hostility is disheartening, anecdotal examples of specific individuals behaving badly is not enough to prove a trend, especially in light of the competing experience of “Not My President” youth rioting in cities across America. The internet also serves up annual waves of shark-attack videos, but you would be hard-pressed to prove a disturbing trend of shark deaths. Even if you could pinpoint 100,000 rabid racists, they would be little more than a statistical blip in a country of 320 million souls.

In America’s Original Sin, a book which I reviewed a few weeks ago, author and Sojourners Magazine editor Jim Wallis says that, yes, America is still racist, and lists three key sources for its ongoing prejudice:

America’s history of outright racism, as exemplified by slavery, Jim Crow, and the territorial conquest of Native American lands;

America’s demographics that allows whites to achieve power over other groups; and

The institutionalization of racism, especially within the criminal justice system.

(Wallis also identifies “white privilege” as a key concern, but always as a residue from these other sources rather than as a source itself.) While Wallis does a good job at fleshing out these sources, proof that they are the foundation for current ongoing prejudice is lacking. A nation’s behavior from centuries before is not always indicative of its current state. Portugal achieved imperial dominance during the sixteenth century, but nobody today worries about it rising up and rebuilding its empire. Likewise, demographics alone cannot explain racism, since there are examples of countries, such as Singapore, where racial harmony appears to be the norm despite a heavy mix of races.

Wallis’s identification of institutional racism is more salient. If the American slave system from two centuries ago was anything, it was an institution, complete with backing from states, federal law, and the US Constitution. In the era of Jim Crow, long after the abolition of slavery, states and local jurisdictions enforced rigid race-based laws and codes that kept most African-Americans, and even some white minorities, from advancing in society. Individual acts of racism certainly played a part, but it was by the support of the government and other institutions that bigotry became a sanctioned activity.

Therefore, it’s fair to say that if a nation’s official institutions exist in part to enforce racist policies, then that nation is, in fact, a racist one. Using this definition, it should be fairly straightforward to determine if America meets that standard or not. To help make that determination, we need look no further than to the words of our current president, Barack Obama.

In 2008, then candidate Obama gave a speech on race following inflammatory comments by his pastor, the Reverend Jeremiah Wright. In that speech, Senator Obama rejected Wright’s view of America as a static, racist country. Instead, he spoke of a country that allowed him, the child of a black father and a white mother, to seek the highest office in the land. “For as long as I live,” Obama said, “I will never forget that in no other country on Earth is my story even possible.” The speech included concern for some struggles that still existed, stemming as they did from the “brutal legacy of slavery and Jim Crow.” But overall, his speech was one of hope for a country that had achieved so much, and that would achieve much more in the future.

So at least as recently as eight years ago, things looked pretty good from the perspective of the country’s first African-American president. While acknowledging some residual difficulties, he communicated in no uncertain terms that America had achieved much because it had discarded the shame of its “brutal legacy.”

The same candidate who spoke those comforting words has presided over the nation’s central institution—its government—for the past eight years. It seems unlikely that, under his watch, he would have advanced the cause of prejudice. It seems unlikely because it is. Despite this, many Americans are resurrecting Jeremiah Wright’s errant claim, the claim that this country is defined by pervasive racism. They offer up as proof a handful of shocking Facebook images, and brash comments by the president-elect. But as we have already determined, isolated outbursts of racial insult are insufficient on their own to prove that the nation as a whole is racist.

Why do so many Americans, in light of President Obama’s earlier claim of hope for this nation, now insist that racism runs deep, especially through the white community? For the answer, we return once again to the president’s 2008 speech, where he lays out his understanding of what he expects for America: “This union may never be perfect, but generation after generation has shown that it can always be perfected.”

This drive toward cultural perfection motivates many Trump detractors. It is a religious quest for perfection that is derived not from sacred texts or the voice of God, but from a self-confident set of self-derived beliefs, primarily left-leaning political beliefs. As with all religious crusades, there are saints and sinners, and the sinners must be chastised. The election of a minority as president is insufficient penance when even one American who rejects the core tenants of the religion of perfection remains. As saints for the cause, those who label Trump supporters as racist feel justified in passing judgment on all who vary from the faith. They have traveled far along the road to moral perfection, and thus are holy enough to call sinners to repentance, or perdition.

Consider, as an example, a recent article by Mark Joseph Stern, writing for Slate. In “The Electoral College Is an Instrument of White Supremacy—and Sexism,” Stern attempts to prove that the Electoral College and other “systems and structures were designed to preserve white supremacy.” He ends the essay with a call to abolish the racist and sexist Electoral College, the constitutional instrument that thrust Barack Obama into the presidency, and that nearly gave us President-Elect Hillary Clinton:

States are a collection of human people, not electors, and the president they choose represents all of them. Abolishing the Electoral College would be a good way to recognize this basic fact of a modern constitutional democracy.

—Mark Joseph Stern (underlining added)

By “modern” constitutional democracy—forgetting for the moment that America is a republic, not a democracy—Stern implies a nation of “human people” like him, more enlightened and more perfect than the founders who acquiesced to their slavish passions. This understanding of self-perfection provides all the justification they need to whitewash as racist the lesser among their fellow citizens, those who fail to heed the righteous demands of this modern political faith. If only people like Stern had lived among the nation’s founders, they would have had the moral fortitude and insight to right the wrongs of slavery before they had a chance to infect the American soul.

Of course, Stern would have done no such thing. He would not have been any more enlightened in those days than the learned founders. He would have treated blacks with the same institutional disdain as those around him, because it was the cultural norm. Had Stern lived in that era, he would have joined with his fellow white males in codifying this into law, and enshrining it in the text of the Constitution, confident that the long-term vision of a unified continent outweighed the temporary matter of racial violence. He would have done this because, at its founding, this country was racist. But he wouldn’t and couldn’t do that today, because the institutional support is not there, because America is no longer a racist nation.

[Image Credits: flickr.com/Lorie Shaull]

November 11, 2016

VSM: Cool Case Clauses in Visual Basic and C#

Visual Basic is normally thought of as the more simplistic language when compared to its sibling, C#. But in the area of conditional case blocks, Visual Basic wins on the complexity front. Whereas C# allows you to take action based on simple numeric selection, Visual Basic adds numeric ranges, lists, comparison operators, and even function calls to your selection criteria.

There are ways to increase the complexity in C#. They aren’t the most efficient, and probably aren’t the way you should do things in that language. But if you are a C# programmer who wants to understand the rich features available to Visual Basic developers, check out my latest Visual Studio Magazine article, “Cool Case Clauses in Visual Basic and C#.”

[Image Credits: Visual Studio Magazine]

November 9, 2016

Samsung Issues Recall of Faulty “Hillary” Product

Still reeling from the literal explosion of its Galaxy Note 7 cell phone series, Samsung issued an immediate recall early Wednesday morning for its “Hillary” leadership product. Samsung Electronics America president and CEO Yangkyu Kim said in a statement that the sudden recall was primarily due to the product’s “failure to catch fire.”

The Hillary, available only in the US market—though some claimed it could be obtained overseas for a substantial markup—was the first female device of its kind to reach nationwide coverage. The Korean device manufacturer made the “woman” feature a cornerstone of its marketing campaign. “American consumers have been clamoring for a leadership device just like this,” said John Podesta, marketing manager for the product line. In an ironic twist that heralded the end of the Hillary, Podesta’s own internal memos were leaked in recent weeks, leading some to suspect that the downfall was orchestrated by Samsung’s rivals. Or Russians.

One of those rivals, Trump Industries, expects to dominate the market for the several years thanks to the removal of the Hillary. Its titular “Donald Trump” product, universally panned by critics, was nonetheless thrust into prominence in part due to rumors of Hillary’s failures. “This is a great day, not only for Trump, but for all of America,” said Donald Trump, head of Trump Industries and designer of the Donald Trump.

The cancellation of the Hillary brings to a momentary halt the bitter device war that had monopolized US media, and the interest of the entire world, for the past two years. But some commentators believe it is only the beginning of renewed infighting within the industry. Angry protests cropped up quickly after Samsung’s announcement, including among UCLA students in southern California. Screams of “Not My Device” could be heard from the crowds, who expressed repeated anger over perceived flaws in the Trump product. “Who wants such a huge device in their pocket?” quipped freshman Chanterelle Rivera.

The Democratic National Committee, the political arm of Samsung’s US operations, said it was not giving up. “This is a time when we must carefully examine the problems that brought us to this point,” said interim committee chairperson Donna Brazile. “Or, we could just destroy the Donald Trump. That’s probably easier.”

[Image Credits: Wikipedia]

November 7, 2016

Blame the Electoral College Yet Again

With just one day remaining in the 2016 Election Season from Hell, anticipatory angst over which candidate will win the presidency is leading many, yet again, to demand that the Electoral College disappear. As you might recall from the bitterness that has erupted every quadrennial since the 1990s, American voters choose a president only indirectly, through the votes of the Electoral College. Small variations in the popular vote can generate wide Electoral College spreads, and in some cases, the winner of the popular vote has still lost the Oval Office.

Even if Hillary Clinton wins tomorrow’s vote, the Electoral College might hand the election to Donald Trump. It’s all thanks to a possible “faithless elector” out of Washington State. Robert Satiacum, an elector who favored Bernie Sanders during the Democratic Primary, has announced that he will not, as an elector, cast his official vote for Hillary Clinton should she win on Tuesday night. “I will not vote for Hillary Clinton,” he told ABC News last Friday. “I will not write her name. I will not. I will not.”

Faithless electors have appeared in the past, but they have never made a difference, because a large enough point spread in the final Electoral College count made the modification of a single vote meaningless. But with the Clinton-Trump race tightening up, it could have an impact this time around.

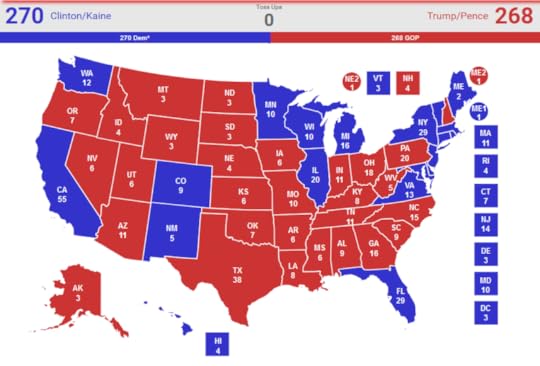

As I write this post on the Saturday before the election, the latest Real Clear Politics “No Toss Ups” electoral map shows Clinton winning, 297 electoral votes to Trump’s 241. If 27 votes were to swing away from Clinton and toward Trump, that would still leave her victorious, 270 votes to 268. This could happen if both Pennsylvania (a possibility) and Oregon (fairly unlikely) made the switch, as shown in the updated map below.

If Mr. Satiacum switched his vote from Hillary to Trump, that would lead to an electoral tie, with each candidate earning 269 votes. (Satiacum has actually suggested that Mickey Mouse would receive his vote, not Trump, but let’s maintain the fantasy a little longer.) In the event of a tie, the decision would be left in the hands of the House of Representatives, where each state delegation gets a single vote. When you group representatives by state, Republicans control between 33 and 36 of the 50 available votes, although the exact number might change a little before such a vote occurred in January.

A Trump presidency would be the likely outcome in this scenario. And if the bitterness that arose from the Bush-Gore election is any indication, calls for the end of the Electoral College (and the end of a Donald Trump administration) would be deafening. Of course, it wouldn’t be the fault of the entire college of electors, just of the sole disruptor from Washington. But with his penalty limited to a $1,000 civil fine, he might be willing to swing the election, assuming that his dislike for Hillary is sufficient.

This wouldn’t be the first time that the Electoral College threatened to mess up the election. In 1800, with Thomas Jefferson pitted against the incumbent John Adams, a quirk in how the Electoral College worked at that time resulted in a tie between Jefferson and Aaron Burr. It took the House a full thirty-six separate votes, and a change of heart from Alexander Hamilton, to break the tie and put Jefferson into the Oval Office.

Despite the frustrations of that early election, the Founders chose to adjust the Electoral College (via the Twelfth Amendment) rather than to abolish it completely, because it offered a semblance of balance between “strong” and “weak” states. Under a popular-vote system, large urban populations in cities like Philadelphia and New York tend to overwhelm less populace states, making votes from those “weak” states somewhat irrelevant. The College enhances the role of the smaller states, and because we are a United States, and not a United Citizens of the Various States, such a buttressing of those states made sense.

Thanks to increased urbanization, and a reduction in the rural population, this strong-weak state divide is even more pronounced today. With the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868, and as interpreted through Bolling v. Sharpe in 1954, Americans today tend to view the United States as a single entity, instead of as fifty closely knit states. And yet the states still exist today, as do the foundational reasons for their existence. Until such a time as the citizens of this country see fit to eliminate state distinctions through a constitutional amendment procedure, the need to balance the relative strengths of the states through the Electoral College will continue to be important.

[Image Credits: Joe Madruga; RealClearPolitics.com]

November 4, 2016

VSM: Local Static Variables in Visual Basic and C#

Programming language variables are a lot like fruit flies; they live for a lot less time than you think. This is especially true of local procedure-level variables. The C language included a feature called static variables that extended the lifetimes of local variables well beyond those of their peers.

C#, the direct descendant of C, lacks this feature, but it lives on—and for much longer than you might expect—in Visual Basic. Despite its absence from C#, there are workarounds that may allow those migrating from Visual Basic to keep enjoying this feature. Read all about it in my latest article from Visual Studio Magazine, “Local Static Variables in Visual Basic and C#.” Long live static variables!

[Image Credits: Visual Studio Magazine]

November 2, 2016

Can a Christian Vote for Trump?

Donald Trump certainly isn’t making the 2016 election easy for American Christians. While the more conservative Evangelical population favors some of his rhetoric on fiscal and social policies (especially compared to the alternatives offered by Hillary Clinton), when it comes to his personal affairs—take that any way you want—the news is troubling.

Prominent religious leaders have lined up on both sides of the Trump issue, and few have considered a vow of silence as an option. Evangelicalism’s favorite son Franklin Graham, as well as commentator and author Eric Metaxas, have taken the “at least he’s not Hillary” approach, defending Trump’s public statements as secondary to his policies or court appointments. On the other side of the pew, popular Christian author Philip Yancey said he is “staggered that so many conservative or evangelical Christians would see [Trump, with his moral failings] as a hero.” Beyond these national voices, many believers are asking if it is appropriate for a Christian to vote for someone as odious as Trump.

Americans have long attributed our safety and prosperity to God, or to his Enlightenment-era moniker of Providence. We look to verses like Romans 8:28 (“All things work together for good”) and Psalm 33:12 (“Blessed is the nation whose God is the Lord”) to describe our international success. While these verses, as biblical promises, are true, the security and comfort we have enjoyed as a nation has caused us to misapply such truths so that they say more about us than they do about God.

For many American believers, God is a micromanager, and he exerts his control over every picky detail of our lives, politics included. Our assent to his management style becomes the catalyst for national peace and power. You hear this belief in our daily prayers, each time we ask God to “bless this food to our bodies,” providing the Creator one last chance to eliminate microscopic pathogens from our fast food, no matter how carelessly it was cooked. When things do go wrong, we dredge up the ghost of Joseph from the final chapter of Genesis, insisting that “God intended it for good,” like an eternal member of the Illuminati secretly pulling the strings. Those who work against his plan, like Joseph’s brothers, “meant it for evil,” and become the villains.

With this view of scripture, each decision we make becomes a litmus test for our trust in God and in the minutiae of his plans. Every blessing is evidence of God’s provision and love; every failure is proof of our faithlessness and rejection of his promises. Blessings and curses, good and evil, black and white; either we’re for God, or against him, to blindly paraphrase Jesus in Matthew 12.

And so it goes with voting. When I pull the lever for a candidate, I am not simply making a decision about legislative policies or America’s standing in world affairs. I am an extension of God’s hand, working the election and all other things together for good. If I fail to cast my vote in line with the will of God, the blessings of the Almighty will be withdrawn, and we will suffer the fate of all those who reject his kingdom and his righteousness.

That’s a lot of pressure, and it’s completely unnecessary, since such a view of American politics has no biblical support. Like it or not, America is not God’s kingdom, we are not his chosen people, and our leaders are not the means of his grace.

Voting is an exercise in secular authority, not a participation in a holy sacrament. Certainly, everything a Christian does is supposed to be informed by godly dictates. “In everything you do, whether in word or deed, do it in the love of Christ” (Colossians 3:17). But it turns out that the love of Christ is surprisingly broad, and isn’t limited to whether the targets of our actions are perfect human beings.

When we buy milk at the store, we don’t ask ourselves if it’s God’s will that we consume dairy products, nor do we seek his guidance on the question of national brands versus locally sourced products. We buy milk based on our understanding of its nutritional value, its utility to our daily sustenance, and our preference for creamy beverages. We can pray that God would bless this milk to our bodies, but if we leave it out on the counter all day long, we will still get a sour stomach.

This attitude toward milk consumption works for Christians and pagans, since drinking milk is not the means by which God achieves his goals. In the same way, our electoral choices should be driven by our understanding of each candidate’s “nutritional” value for the nation, his or her utility in our daily sustenance, and our preference for leaders who are the cream of the crop. No miracles required.

This outlook on our civic duty demands that we understand the role and responsibilities of the president, and how a particular candidate will best carry out those duties. Sadly, a lot of voters do not understand the fundamentals of our constitutional republic, and so they toss the ball into God’s court, or they list out a candidate’s sins as a substitute for determining qualifications, since they lack an understanding of what those qualifications should be.

Naturally, the moral turpitude of a politician should weigh on our decisions, because a candidate who is inclined toward bad behavior will likely engage in bad behavior once power is achieved. But such considerations can be made using good old fashioned research. Praying that God would provide us wisdom in our voting choices is a good thing, but it does not excuse us from carrying out our commonwealth responsibilities. And the very idea that a political candidate will help us act justly and love mercy and walk humbly with our God is laughable.

The questions we should be asking ourselves about Donald Trump this November shouldn’t be based on whether he is a loudmouth, or a jerk to women, or whether he was a model of business acumen. Our questions instead should be based on his alignment with the responsibilities of the Executive. Which candidate will carry out those policies that are the best for the nation as a whole? Which candidate will best perform the duties of Commander in Chief when required? Which candidate will best preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States?

These questions are not tests of your deeply held Christian beliefs. You can vote for Donald Trump, or Hillary Clinton for that matter, and still be a child of God. Moving the election out of the heavenly ether and into our daily lives will require more than a two-minute prayer, or a knee-jerk reaction to some ten-second soundbite on the nightly news. We still ask God to bless the United States of America. But when we take seriously the civic, and even secular, truths of what makes a good president, it becomes yet another source of blessing for the country.

[Image Credits: Wikipedia]