Tim Patrick's Blog, page 13

October 31, 2016

Apple’s Escape from Reality

Last Thursday, Apple announced its updated MacBook Pro line of computers. The laptops are thinner and lighter than before, certainly “the thinnest MacBook Pros we’ve ever made.” The ten hours of battery life seems underwhelming given the sixteen-hour laptop that Microsoft announced the day before the Apple event. But it probably won’t catch fire, and the sleek, light update will sell like crazy.

During the presentation, Phil Schiller spent most of his time introducing the Touch Bar, a keyboard-wide Retina Display that lives where the function keys used to reside. This touch-sensitive region presents the standard F1, F2, etc., function keys, but can also adjust itself with different keys, sliders, images, and spell-check features based on your main-display activities. For those who find typing on the flat surface of an iPad tablet to be nothing short of a religious experience, the new Touch Bar will be the number one reason to upgrade to the new MacBook Pro.

It’s not for me. Sure, I’ll lament the loss of the function keys, even though during the four years that the MacBook Pro was my primary coffee shop device, my attachment to those keys came primarily through Microsoft Word activities. But Apple has also seen fit to eliminate the Escape key, and for me, that ruins what was already a flawed input surface.

If you’re not a programmer, you might have overlooked the Escape key. Perched in the upper-left corner, it was one of those lesser-used keys, like backslash (\), or the circumflex (^). But I used it constantly, especially when editing computer source code. I’m a fan of VI (“vee-eye”), a code editing tool introduced in the mid-1970s, back when “computer graphics” meant, well, pretty much nothing.

VI is keyboard-centric, a mouse-less tool from a mouse-less era, designed for fast text input for people who seldom communicated apart from the keyboard. The program sported three main “modes,” one for typing, one for moving around, and one for issuing special commands. The Escape key helped you navigate between these modes with minimal hand movement. With Escape’s static location in the far corner of the keyboard, VI users had at least one safe, known place they could depend on.

But not on the MacBook Pro. While Escape still remains as a Touch Bar feature during some text entry experiences, its lack of physicality will certainly have an impact on the fifteen percent or more of developers still using VI or one of its modern variants as their main code modification tool.

I left the MacBook Pro world for a Dell XPS 13 about two years ago, and one of the main reasons for returning to Windows had to do with keyboard issues. In Windows, the Alt+Tab keyboard combination lets you rotate through all of your active applications. It’s quick, and the position of the keys makes it an easy reach for such a common task. But on Apple laptops, you needed to alternate between an unhealthy set of key-pairs (Command-Tab and Command-Backquote) to accomplish the same thing. And pasting text with Command-V required that a mobster break your left thumb in the right place.

So it’s no surprise to me that Apple has, once again, opted to dispense with the past, evoking the same “courage” that allowed it to remove the ubiquitous headphone jack from its latest iPhone. Perhaps you are just fine with the late, great Escape key, or the upgrade of the function keys to a capacitive replacement. For me, it’s just one more opportunity to shed some tears over a bit of input device nostalgia, all from the comfort and safety of my Windows keyboard.

[Image Credits: pixabay.com/KaoruYamaoka]

October 28, 2016

VSM: Overcoming Escape Sequence Envy in Visual Basic and C#

My very first software job used the C programming language. It’s a quirky language in many ways, especially when it comes to things like double pointers. But when I compared it to the BASIC language used in my high school programming classes, I quickly came to appreciate C’s escape sequences, simple shortcuts that allowed you to insert special non-printable characters in the middle of ordinary text content.

C#, a direct descendant of the original C language, still includes those escape sequences. Visual Basic, Microsoft’s other key .NET language, has no intrinsic support for these sequences, and to be frank, it made building more complex strings exactly that: more complex. Adding tabs and line endings to a block of text became a process of keyboard dexterity as you tried to get all of the operators and quotation marks in the right places.

Fortunately, there are alternatives to the plain-Jane strings included in Visual Basic. To learn about the options, read my article, “Overcoming Escape Sequence Envy in Visual Basic and C#,” on the Visual Studio Magazine web site.

[Image Credits: Visual Studio Magazine]

October 26, 2016

Undecided Voters Plan Final Tour, Analysis of Yard Signs

With the election just days away, many Americans are realizing for the first time that, oh crap, I’m going to have to vote for one of these candidates. But which one? The grumpy one with the coiffed hair, or Trump? Short on alternatives, many voters are looking to the same time-tested source that those who already made up their mind used: yard signs.

High-color, professionally printed yard signs have moved into virtually every neighborhood in America. Adorned in modern red and blue saturation levels, and festooned with the candidates’ names—and if you’re lucky, a slogan—such placards are a welcome feature in what would otherwise be an election season without much to differentiate political contenders.

Despite this omnipresence, some voters insist that yard signs fall flat. “I’ve been driving around town for weeks, hoping to get some spark of inspiration about what to do in November,” said George Pepperidge, a mid-level manager working in San Diego, and who so far has found only disappointment in the candidates. “I think it’s the fonts they use.” Sally Weltz, a Dallas-area undecided, expressed consanguineous sentiments: “What a bunch of squares.”

In past election cycles, voters waiting until the last moment would often seek media-sourced input, such as thirty-second TV ads. But with dwindling television viewing habits and the popularity of ad-blocking technologies in web browsers, campaigns have been forced to up the yard-sign stakes. “It’s the best way of getting our message out to the American public,” said Donald Trump, whose name appears on a lot of signs. “And if you look at it, we have the best signs, and frankly the best yards, thanks to Mexico.”

A look back in electoral history reveals a dramatically different means of narrowing down the presidential options. “The internet didn’t always exist,” cautions Eleanor Wojohowski, a professor of Political Media Studies at Sausalito College in St. Louis, Missouri. “Voters used to consume policy documents and speeches put out by the major candidates, and form opinions based on an analysis of the political positions. The famous debates by Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas are classic examples, where voters would listen to the candidates discussing meaningful ideas for hours on end. Kind of silly by today’s standards.”

In a last-ditch effort to come to a decision before Election Tuesday, roving gangs of undecided voters are congregating in front of homes with especially nice sign displays. Yards with signs put at slight angles have proven to be especially influential. “I’ve been waiting for a sign,” said Randi Suzuki, loitering with six other unlikely voters in front of a four-bedroom, two-bathroom home in an upscale section of Boise, Idaho. “I mean, this voting stuff’s important, right?”

[Image Credits: kxro.com]

October 24, 2016

In Wikipedia We Trust

Of course you use Wikipedia. A decade or so ago, when the printed Encyclopædia Britannica was still a thing, everyone who wasn’t a high-school essay writer griped about how Wikipedia was the worst, couldn’t be trusted, and wasn’t a real encyclopedia anyway. Today, it’s the fifth most popular web site on the internet. It’s still not a real encyclopedia in the traditional sense of the word. But it is trusted. When you browse to any page on the site, you visit with the expectation that everything you read there will either be correct, will include links to the actual information, or will have a parallel argument happening on the “Talk” page about how the content needs to be made even more accurate.

Wikipedia is a crowd-sourced property, but so are public landfills, and we seldom visit them. Other popular sites like Facebook and YouTube are used with the understanding that you can’t believe everything you see online. But that’s not the case with Wikipedia. Sure, people say it can’t be trusted. But they use it anyway, as if it is fully trustworthy, and that’s strange. As humans who have been burned or spurned in the past, we are quick to withdraw our trust. It only takes about a week before I start sniffing the milk in the fridge. Some of the most popular movies and TV shows are based on deceit, mistrust, and suspicion. And then there’s the 2016 presidential election.

But people do trust Wikipedia, despite it being edited by millions of people you’ve never met, and likely wouldn’t immediately trust in person. In a 2006 presentation, Jimmy Wales, the founder of Wikipedia, discussed the nature of trust on the site, comparing it to the same trust inherent in restaurants that put steak knives on every table. What’s to stop customers from stabbing each other? What’s to stop people from mucking up the encyclopedia? For Wales, trust itself is the reason that Wikipedia remains a trustworthy resource, and that by entrusting the public with a resource, they voluntarily make it a good resource.

When you prevent people from doing bad things [by locking down a resource], there is often very direct and obvious side effects, that you prevent them from doing good things…. This kind of philosophy of trying to make sure that no one can hurt each other actually eliminates all the opportunities for trust.

— Jimmy Wales

I don’t know if I would extend Wales’ philosophy to all aspects of my life. Opening my bank account as a public, trusted resource would probably end up bad, at least for me. And for complex resources such as a hydroelectric dam, where high levels of expertise are required for key components, a fully open and public management system could put the project itself, or things downstream from the project, at risk. But for resources where the bar to entry is relatively low, and the risk is dissipated across the entire system, public management seems to work.

Each year, the Wikimedia Foundation, the parent organization of Wikipedia, does one of those NPR-style fundraising drives. There are naysayers who insist that the Foundation is stealing your money and doesn’t need all of that cash. Whatever. All I know is that the tiny amount I donate to them each year doesn’t come close to the value I get from the site. If you, like me, think of Wikipedia as your first step on your way to more advanced research opportunities, then you might want to consider your own donation to the group.

October 21, 2016

VSM: It’s All About Character in C# and Visual Basic

I’m continuing my series of articles for Visual Studio Magazine, and this time around the discussion deals with the character and string data types as used in C# and Visual Basic. Both languages defer to the core .NET data types when dealing with text content, so they behave identically in every way. Or do they?

Visual Basic, designed as it was for the entry-level software developer, includes some nice usability features that wrap up a lot of boilerplate code and safe data practices into single commands. C# lacks those features, so when you attempt to move logic from VB to C#, you can sometimes struggle to replicate the original logic. Sometimes, this can lead to outright errors.

I found this out the hard way, when developing a new C# project based partially on some Visual Basic code I had written earlier. The details of what I went through, including the successful and happy resolution, appear in my article, “It’s All About Character in C# and Visual Basic,” on the Visual Studio Magazine web site.

[Image Credits: Visual Studio Magazine]

October 19, 2016

Review: America’s Original Sin

The last few years have been a difficult time for race relations in the United States. Eight years ago, the general consensus was that the election of Barack Obama as president would prove once and for all that American had finally overcome the baggage of its “peculiar institution” of slavery. Two terms later, we are all struggling to understand the almost-daily news reports of race-based animosity and violence.

In the book America’s Original Sin, Jim Wallis, the editor of the progressive Christian magazine Sojourners, attempts to discover the root causes of our modern racial unrest. The whole “don’t judge a book by its cover” caution is something to consider in this case, with its catchy yet provocatively false title. Slavery—the racist “original sin” of which Wallis writes—is neither original with the United States, nor did the first Puritan migrants engage in the practice. As goes the cover, so goes the book, it turns out, with similarly catchy yet provocatively false statements peppering each of the book’s ten chapters.

Because Wallis is writing as a Christian, and with a message directed toward Christians, I tried to read the book as if it were an intentionally Christian book. Some of the book’s core points are fully secular in nature, but a big part of the author’s message is that Christians are both specifically to blame for America’s race woes, and uniquely tasked with correcting the problems.

Unfortunately, one of the main downfalls with the book is in its misapplication of the most basic tenants of the Christian faith, specifically those dealing with sin, guilt, and forgiveness. When looking at the book as a whole, I found two key areas of concern with Wallis’ message, the first secular, and the second religious.

The first of these concerns is with Wallis’ insistence that race touches everything. Wallis assumes that, because everyone has a race, everything can be tied to racism, or at least to the background that stems from one’s race. You could not, for instance, do this with the issues of homelessness or smoking, since not everyone has been homeless or has used tobacco. But everyone has a race, and for Wallis, this implies that there is always a tension between those of different races. Or to put it another way, he believes that when tensions do arise within a society, you can identify race as a key factor in that tension. In the context of America, this means that there is always a conflict between whites and blacks, and specifically, with the power that whites have over blacks.

Wallis makes this point by repeating the “racism is prejudice plus power” bromide. In a generic context, this expression could be taken at face value, that when one group uses its power to push racial prejudice, racism occurs. But for Wallis, simply being in the majority is itself proof of power, and more than that, proof of prejudice with power. Because I am white, and whites are (for now) the majority, I am therefore empowered over my black neighbor, and therefore am racist. Of course, this jumps over the “prejudice” aspect of the equation. But Wallis assumes that as well, since he believes that whites are, by nature, racist. He starts out the book by saying that, “We are not now, nor will we ever be, a ‘postracial’ society,” because whites have been, are still, and likely will always be racist.

For Wallis, much of the problem stems from “white privilege,” which is the leftover residue from the eras of slavery and Jim Crow. Wallis says that many whites are unaware of their privilege, but then he uses this concept of privilege as the basis for proving that whites are, even today, consciously and actively racist. In Chapter 3, he says, “Whites in America must admit the realities of racism and begin to operate on the assumption that ours is still a racist society…. White people in the [US] have benefited from structures of racism, whether or not they have ever committed a racist act, uttered a racist word, or had a racist thought (as unlikely as that is).” I underlined that last part to show that, for Wallis, it is practically impossible that whites could ever be non-racist. Of course, the irony is that this very idea is, itself, racist.

We are not now, nor will we ever be, a ‘postracial’ society.

— Jim Wallis

What shocked me most about Wallis’ line of reasoning concerning pervasive racism is how far it is from the Christian understanding of humanity. The problems humans have with each other, from a biblical perspective, are spiritual and based on the sinful nature. Racism is certainly a part of this nature, but only a part. Stealing is also a part of this nature, but we know from everyday experience that not everyone steals. Not everyone kills. And not everyone engages in racism. We are all sinners, and if you break one of God’s commandments, it is as if you are guilty of breaking them all. But Wallis does not discuss racism in this spiritual context, but rather in a secular, societal context, where theological concerns over the pervasiveness of sin are not supposed to be the source for laws. Sin touches everything, but racism does not, and as a Christian leader, Wallis should understand this.

My second concern with the book, and the one that grieves me the most due to its implications for the Church, is Wallis’ tacit belief that guilt can be corporate, and that the way to assuage such guilt is through ongoing retribution. And he appears to believe this in spite of having an entire chapter that is specifically about replacing “retributive justice” with “restorative justice.”

In Christianity, guilt is not corporate, but individual. I sin. I am guilty before God. I deserve condemnation. But when salvation through Christ comes, I am declared righteous by God, even if others around me do not (yet) share in that declaration. Romans 8, a section of the New Testament that some Christians consider to be the heart of the Gospel message, begins by stating emphatically that “there is therefore now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus.” Whatever sins I may have committed are no longer held against me, although temporal consequences may remain. This is the Good News of the Gospel, and the center of Christian theology.

While I am hesitant to put words in Wallis’ mouth, from his writing it is clear that he does not hold to this view of Christianity, at least where racism is concerned. In the book, all American (white) Christians are guilty of racism, not because they engage in racism, but because America’s legacy of racism rests on them corporately. (He even says that whites who recently came to the US are equally guilty, because they equally benefit from white privilege made possible by whites who have ties back to the era of slavery.) The guilt remains, and is not washed away for such petty reasons as salvation in Christ. Worse, because Wallis sees the guilt as corporate—that the Church as an entity bears the historic guilt for slavery—and since corporate entities can never sufficiently confess, or repent, or assuage their guilt, there will never come a time when the accusations of racism will end, since the guilt persists eternally. Such a belief is at odds with the heart of the Christian message, and yet Wallis, as a Christian leader, uses such a belief as the foundation for his book.

The book is not completely without merit, and some aspects were worthy of the publishing effort. I found much to ponder in Wallis’ concerns over the War on Drugs and the criminal justice system in general. I am not cynical enough to think that drug laws were created with racism in mind, as Wallis at least in part seems to think. But I can’t deny that African-Americans appear to have been impacted by such laws disproportionately. Even if those laws came about in an entirely bias-free manner without any desire for a racist outcome, the social history of blacks in America has linked them to these laws at higher rates than one would normally expect, given the nation’s demographics.

Of course, that disparity is not automatically a sign of racism. Wallis, as a political progressive, glosses over the role that left-leaning policies have played in the situation of both blacks and whites in America. Except for his concerns over the criminal justice system, he never really mentions government, academia, or other societal institutions, at least not in any causative sense. Instead, he directs his largest weapons toward the church, or toward a caricature of the church that serves the book’s purposes. Most churches in America are small, apolitical, and harmless as far as race is concerned. Martin Luther King, Jr’s, statement that Sunday morning is the most segregated hour of the week (which Wallis quotes with glee) is more or less accurate. But Wallis confuses correlation with causation in identifying racism as the source of that segregation.

America’s Original Sin is a useful book in understanding the progressive mindset on issues of race. But it is lacking in any solutions, other than in asking whites to listen to the stories of blacks. As a leader within the Christian community, Wallis has a valuable position from which he could steer America’s national conversation on race. But instead, he uses his pulpit to apply old-time Puritan chastisements that veer Americans far away from the hopeful message of the Gospel.

October 17, 2016

No More 98-Pound Supreme Court Weakling

Fear is a big motivator. One chunk of the American electorate fears Donald Trump because of the choices he might make to the Supreme Court. Another swath of Americans has that same fear, but stemming from Hillary Clinton being in the judicial driver’s seat. Or to put it another way, there are a whole bunch of voters who fear the Supreme Court vicariously through the Democratic and Republican presidential candidates.

It was not supposed to be this way. Although the Judicial Branch is one of the three co-equal arms of our national government, it was assumed to be the weakest of the three. Certainly, the Court is authoritative, with its power to adjudicate extending over all laws of the United States, over treaties, over cases involving ambassadors, public ministers, and consuls, and over all controversies “between two or more States;—between a State and Citizens of another State;—between Citizens of different States;—between Citizens of the same State claiming Lands under Grants of different States, and between a State, or the Citizens thereof, and foreign States, Citizens or Subjects.” That’s a lot of controversy.

Despite all of that power, the Judicial Branch was assumed to be the weakest in its temptation to impose tyranny on citizens. This can be implied by the lack of direct checks and balances on the judiciary. Such limits exist for the other two branches. The Executive Branch has veto power over laws passed by the Legislative Branch. And the reverse is also true, with Congress free to enact a vetoed law through a supermajority vote. The separation of powers into three branches is itself a limit on each branch’s authority, but there is no named check on the Supreme Court beyond impeachment of individual judges, and the overkill move of amending the Constitution.

The Founders worried about tyranny, perhaps even feared it. Having recently released themselves from Great Britain, they had no desire to return to a system where individual rights could be discarded without due process. Therefore, they took the advice of Montesquieu and imposed a separation of powers with established limits and checks that would prevent the consolidation of authority into a single person or governmental body. Presidents could take the nation to war. Congress could tax the people heavily. But the court? All it could do was break up fights between citizens and states. The Founders used a light touch when constraining the Court, because they expected little in the way of trouble from the relatively limited powers vested with that branch.

Trouble came soon enough. In 1803, when the country was still a relative infant, Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall implied the power of judicial review in the famous case of Maybury v. Madison. This decision allowed the Court to strike down any law it found to be in conflict with the Constitution itself. In effect, the Court granted itself a “super-veto” power, better than the one officially granted to the President since Congress could not overturn it. While Maybury added a new check on the Legislature, it found no such new check on the increased power of the Judicial Branch.

In one quick decision more than 200 years ago, the Court found a way to consolidate additional authority not previously granted to it through the Constitution, exactly the type of action that the Framers sought to avoid. Today, the effective power of the Court has increased even more, with some recent activist decisions having the power of laws, laws that were supposed to be constructed only through the other two branches.

And so we arrive at the situation where power is consolidated even more, in that the Court—or more correctly, the fear of the Court—impacts the presidential election. While the Executive and the Judicial are still legally distinct, this perceived overlap lets them act as one, and reduces the effect of the separation of powers.

One partial solution to this increase in extraconstitutional authority would be to impose a check on the Judicial Branch. Robert Bork, the Reagan-era Supreme Court nominee who was famously “borked” by Congress, offered up just such a remedy. In Slouching Towards Gomorrah, Bork recommended a constitutional amendment that would grant state legislatures veto power over lower-level federal court decisions in constitutional matters. Because Article Three provides the Supreme Court with “appellate jurisdiction” rather than “original jurisdiction” over most cases of constitutional import, checking such decisions at the state level would reduce the number of these cases reaching the highest court, and therefore reduce the temptation and ability for the Court to legislate from the bench.

Since this solution would need to come in the form of a constitutional amendment, such a prospect seems unlikely. If history is any indication, the consolidation of power seen so far will continue. When that happens, fear of the Court will no longer need to be done vicariously.

October 14, 2016

VSM: A Lifetime of Data in C# and Visual Basic

In both Visual Basic and C#, every data value has a lifetime. Each value comes into existence, lives a good, middle-class life, and eventually fades into the emptiness of the garbage collection process.

Because both languages use the underlying .NET Framework for data management, they generally treat each data value identically. But when it comes to lifetimes, there are situations where the languages treat data differently, and in ways that can impact your source code.

To find out exactly how the languages differ, read my new article, “A Lifetime of Data in C# and Visual Basic,” on the Visual Studio Magazine web site.

[Image Credits: Visual Studio Magazine]

October 12, 2016

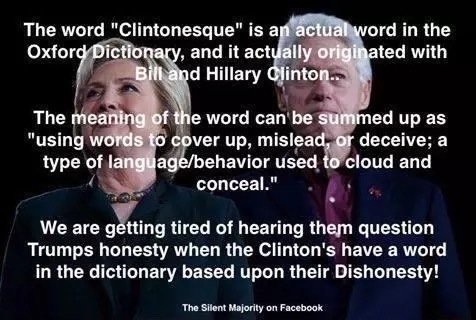

Meme Clarity: The Very Definition of Clintonesque

This week’s meme reaches deep into the dark cave of irony by using deceptive behavior to claim that Hillary Clinton engages in deceptive behavior. The image appeared on my Facebook page last week, and invoked the definition of “Clintonesque” as found in the Oxford English Dictionary.

The word ‘Clintonesque’ is an actual word in the Oxford Dictionary, and it actually originated with Bill and Hillary Clinton…

The meaning of the word can be summed up as ‘using words to cover up, mislead, or deceive; a type of language/behavior used to cloud and conceal.’

We are getting tired of hearing them question Trumps [sic] honesty when the Clinton’s [sic] have a word in the dictionary based on their Dishonesty!

— The Silent Majority on Facebook

It’s a good thing that the “Silent Majority on Facebook” actually summed up the meaning of the actual word Clintonesque for me, because the definition they provide is something I actually would never have extracted from the actual dictionary entry, actually.

In case you were curious, the definition of Clintonesque, as published in the Oxford English Dictionary, reads as follows: “Originally: relating to or characteristic of Bill Clinton or his policies. Later also: relating to or characteristic of Hillary Clinton, or Bill and Hillary Clinton as a couple.” That’s the entire definition. There is nothing about deception, or using misleading language or behavior to cloud or conceal anything. The OED does include example sentences, one of which refers to Bill Clinton’s history of fudging the truth. But another example in that same block also attributes Clintonesque characteristics to Bob Dole.

This rather staid Oxford definition hides a rich history of new dictionary words based on presidential names. “Clintonian” shows up in the OED as well, alongside examples that stem from Bill Clinton’s time in office. But the word traces all the way back to 1792, when it was used in reference to George Clinton, the first governor of New York, and Vice President under both Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. In that context, the word identifies associates or supporters of George Clinton, as well as anti-Federalist behaviors that were also attributed to Clinton. That it is no longer used to refer to the man who replaced Aaron Burr as VP (or to his nephew, DeWitt Clinton, for whom the term was also popular a generation later) shows the shallowness of adhering political truths to such ephemeral name-based words.

There are sixteen distinct words in the OED based on presidents that go back to the Reagan error, including Bushism, Clintonista, and Reaganomics. My favorite is Reaganaut. Carter doesn’t get his own term, although the word “carter” is more than four centuries old, back when it referred to a chariot driver or to anyone who managed a cart. It also acquired the meaning of a clown, or someone of low breeding, although the word embodied those definitions long before Jimmy Carter was born.

George Washington was the earliest president to have his own dictionary entry. Like the Clinton-specific term, the word “Washingtonian” refers to aspects of President Washington—often in his association with Federalism—without regard to whether those aspects are positive or negative.

None of this means that Hillary Clinton is actually honest. The feelings conveyed by the meme do stem from a pattern of truth games played out over the past few decades by Bill and Hillary. As with things Nixonian, anything labeled as Clintonesque is bound to produce trust issues in the hearer. Not that Donald Trump gains any advantage in this area. If Trump wins the election, be on the lookout for Oxford’s announcement adding Trumpist to their reference work.

Both of the major party candidates this time around seem to have no qualms about using a wide range of true and false statements to achieve electoral victory. But invoking outright false statements in a meme to point out political or personal deceit in a major presidential candidate is, itself, a key example of deceptive behavior.

October 10, 2016

An Ode to Soundtracks

Neville Marriner, the founder and conductor of the Academy of St Martins in the Fields, passed away on October 2, 2016, at the age of 92. I first heard his music back in the late 1980s, on a road trip across the western United States. I needed tunes for the long drive, but as a poor college student, I had funds for only a single album. I chose one that provided the most minutes of music play per dollar: the two-cassette motion picture soundtrack from Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus, conducted by Marriner.

Amadeus is an outstanding soundtrack, and the first one I ever owned, unless you count the Sound of Music eight-track tape I inherited from my parents. That soundtrack is classic, but with the exception of “Climb Every Mountain,” the album generally conveys a single idyllic feeling.

The Amadeus soundtrack was different. While the music is primarily by a lone composer—Mozart—the tone ranges from dramatic to playful, from foreboding to silly, following the ups and downs of the genius composer and his nemesis in the story, Antonio Salieri.

I must have listened to the entire soundtrack ten times during that trip, and enough times in the years that followed so that the warping of the tape in the cassette became obvious. From a classical composer from 250 years ago, through the gifted conducting of Neville Marriner, I learned to love movie soundtracks and scores.

I now own around four dozen soundtracks on CD, plus a few dozen others in my Spotify album list. In memory of the work of Marriner, I provide here some of my favorite soundtrack albums. After scanning this list, you might also enjoy this commentary on what modern soundtracks do for us, and how they often fail.

Musicals: Musicals are an easy choice for soundtrack love, since the entire movie revolves around the compositions. Classic Hollywood musicals from the likes of Rogers and Hammerstein (including the aforementioned Sound of Music), the Sherman Brothers (Mary Poppins) and Irving Berlin (White Christmas) still stand strong alongside those from traditional stage performances like Grease, My Fair Lady, and Fiddler on the Roof. A more recent delight is Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog, with the voice stylings of Neal Patrick Harris. The equally enjoyable Hail, Caesar! is an outright attempt to bring back the era of musicals. While I am tempted to give my top choice to The Blues Brothers, I find that the soundtrack from the 2007 movie Hairspray repeatedly brings a smile to my face. Despite being a modern tale in why not to be a racist, the tone is nonetheless upbeat. And with lyrics like “Can’t tell a verb from a noun / They’re the nicest kids in town,” you can’t help but sing along.

Pop Soundtracks: While many movies hire a single conductor to score the majority of the background music, some opt instead to use current or retro popular music to help drive the story along. The films of Nora Ephron are key examples, and her films Sleepless in Seattle and You’ve Got Mail (with a score sold separately) are memorable in part because Jimmy Durante and Harry Nilsson are there to support Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan. Some of these soundtracks, including Fame and the wildly popular The Bodyguard, outshine the films where they appear, although some like Tootsie and Arthur seem dated by today’s standards. But one pop soundtrack from the 1970s that continues to hold its own today is Saturday Night Fever. Yeah, it’s disco, but even disco can be worthwhile.

Epic Scores: My collection of dramatic scores runs heavy with the music of John Williams, and why not? Williams is a master at taking a simple theme and expanding it into two hours of content that invokes a complete set of emotions. These bombastic scores pair nicely with laser beams and fisticuffs, although soundtracks like The Mission and Superman include gentle and romantic moments among the adrenaline. The fun, even campy, soundtrack to Back to the Future shows that you can be epic without a lot of bloodshed. But if I have to choose, it must be Williams’ always fantastic score for Star Wars: A New Hope. It was a tough decision, since by passing up The Empire Strikes Back, I had to omit “The Imperial March” that follows Darth Vader everywhere he goes. But that first Star Wars album helped established the entire soundtrack craze, and therefore deserves top billing.

Cartoons and Children’s Films: I swear I bought these when my son was still young. Really. And yet, there are a few kids’ soundtracks that I would likely buy even without a family, especially Hook, The Incredibles, and Mary Poppins. The Prince of Egypt is one such album. Crafted primarily by Stephen Schwarz (who also did Wicked, plus Disney’s Enchanted, another great youth score) and backed up by pop stars like Mariah Carey and Boyz II Men, the songs are an essential component to this specific version of the Moses story.

Jazzy Scores: A lot of films reach for a jazz-based score to lighten the mood, even when the film is already as light as it can be. Mancini’s The Pink Panther is a great example of such mood music, custom designed for the film setting. Others movies string together jazz standards with marvelous effect, including Midnight in Paris and When Harry Met Sally. I recently discovered the smooth soundtrack to Good Night, and Good Luck, with the silky voice of Dianne Reeves invoking her inner Ella Fitzgerald. My choice for this section is a bit campy, and not really classic in the jazz sense. But I can’t help enjoying the score to Dirty Rotten Scoundrels (the film, not the musical). It includes one of the best versions of “Puttin’ on the Ritz” I’ve ever heard.

Classical and Period Pieces: Movies set in an older time period frequently provide music to match. Scores for films like Somewhere in Time, Sense and Sensibility, and The King’s Speech transport you back in time, the time that the film documents. In celebration of Neville Marriner’s life, I was tempted to choose the Amadeus soundtrack for this category. But as my collection has grown, my preferences have changed. Randy Newman’s Ragtime score (again, the film version, not the one from the musical) recreates the era of Joplin, and even though I have not yet seen the movie, the soundtrack is enough to carry me back to that time.

Comedies: If you’re looking for something lighter, a soundtrack from a romantic comedy or an outright comedy might be just the thing. The score to the silly farce Airplane! is surprisingly good, composed and conducted in part by the great Elmer Bernstein, who also crafted classics like The Ten Commandments and the score elements for Ghostbusters. Some of these scores can be quite moving and mainstream; the main theme from The American President, and the patriotic feelings it invokes, can be heard while waiting in line for Soarin’ Over California at Disneyland’s California Adventure theme park, along with other high-flying movie selections. The soundtrack for My Big Fat Greek Wedding provides an international flavor to this lighter category. But my favorite comes from the presidential comedy Dave. It includes a good mix of happy and heartfelt.

[Image Credits: Milken Family Foundation]