Tim Patrick's Blog, page 10

May 30, 2017

The Age of Guns on Campus

When it comes to school campuses today, the expression “Gun-Free Zone” says it all. From the violence brought on schools like Columbine and Sandy Hook, to the protests against military recruiters at some public colleges, the prevailing viewpoint is that the campus is not an appropriate environment for guns of any kind. This zero-tolerance perspective has even led to ludicrous decisions by school administrators to suspend elementary school students who make gun shapes out of Pop Tarts. A Maryland judge last year approved a local school’s policy against “brandishing partially consumed pastries.”

It wasn’t always like this. I recall my own elementary school experience, where parents routinely dropped their kids off in the morning in pickup trucks decked out with gun racks, weapons in tow. A friend told me that his rural college, as recently as fifteen years ago, allowed students to check their hunting rifles into a secure room in the school’s main office, allowing them to go after small game when a final exam wasn’t looming. And there was once a time in America when schools not only allowed guns, but made weapons and ammunition available to students.

I discovered this while reading an article on how World War I impacted one college in Southern California. The story appeared in the Spring 2017 issue of Occidental, the alumni magazine from Occidental College, a small liberal arts school located near Pasadena, California, recently famous as one of the schools attended by a young Barack Obama. In “Life During Wartime,” author Paul Robert Walker describes a time when gun access on campuses was not only a reality, but mundane. Granted, it was wartime, and the students on campus were not just thinking about guns, but also about cannons and bombs and military ranks, and anything else having to do with America’s entry into the European conflict.

Even before Woodrow Wilson—a former college president—brought the nation into The Great War, guns were apparently already a thing at the small California school. Chemistry professor Elbert E. Chandler had been working on a “pet project” of adding an indoor rifle range to the campus, one that “could accommodate seven shooters and was 25 yards long with a regulation steel-plate bulkhead.” The firing range opened in early 1918, just in time for the arrival of Maj. E. D. Neff as the school’s chief military training officer, “considered one of the best marksmen in the entire country.”

An on-campus shooting range meant access to guns. “Although heavy Ross rifles were available, the men,” that is, the male students, “had to buy ammunition at the bookstore, where it was sold at close to cost. Women were allowed to use the range and could obtain lighter .22 caliber rifles at the bookstore.” Think about that: guns and bullets were sold to students, some just out of high school, by school officials at the campus bookstore. Next to copies of Webster’s Dictionary, no doubt. Nobody seemed to fear violence from a wayward student. And while I am sure there were some safety protocols in place, the separation of the gun range from the place where gun supplies were sold means that, at least at some point, students were wandering the campus with rifles and ammo in their possession, and storing them in their dorm rooms.

Small private colleges weren’t the only schools open to military training. The University of California at Berkeley hosted a “College for Ordnance Training School” during that same timeframe, something its students today would certainly find abhorrent. Those were different times; although American didn’t enter the war until its final year, university students would have been fully aware of the ongoing threat on the European continent. But even in the post-war peace, guns were not cast out of schools completely, and a few high schools around the country continued to host rifle clubs long beyond passage of federal gun-free-zone legislation in 1990.

Do I want the kids in my life hanging around schools were guns are prevalent? To be honest, I’m not sure. But what I am sure about is that the level of hysteria we apply to guns on school grounds today was not always the norm.

[Image Credits: University of Connecticut History Archives]

May 23, 2017

National Fear

On a recent trip to Japan, I had the chance to engage in a nomikai with some friends. It’s the kind of small-group event where you drink and eat and drink and sing and drink. And the drinks have booze in them. Anyway, I’m not much of a lush, so I only had tea beyond the first kampai beer, while everyone else enjoyed continuous refills of whatever Japan was serving that night.

When I told the group that I would be driving back to where I was staying after the last karaoke song, there was a sudden clamor. “You can’t do that, Tim,” they said, but with a lot less actual English content. “The police are very strict about drunk driving. You’ll be in jail!” I did a quick check on my phone, and they were right about the police being strict. The Blood Alcohol Content limit for driving in Japan is 0.03, less than half the typical 0.08 limit set in most American states.

Still, I knew I would be under the limit. After I finished that smallish beer, I had five or six hours of eating and singing and walking and arguing over police procedures. By that point, my BAC was close to or at zero, and the rural part of Japan we were in seemed to have police officers at about that same zero level. But the impassioned pleas continued. “Don’t do it! Please! Onegai shimasu!” Finally, I was able to convince one member of the group to see the scientific soundness of my argument. I made it home that night with a sore singing voice, a happy stomach, and no time spent in jail.

This might all sound like a humorous anecdote, but the reaction of my friends is something I’ve seen in other aspects of Japanese society. In the wake of the March 11, 2011, Tohoku tsunami and the ensuing Fukushima nuclear power plant troubles, Japan shut down every nuclear reactor countrywide, and except for a handful of reactivated plants, including one that went active last week, they are still all idle. To meet its energy needs, Japan had to dramatically increase its imports of oil and other fossil fuels, with the share of power generation from petroleum sources nearly doubling between 2010 and 2012. Despite the financial burden this brings to residents, large segments of the population regularly protest any return to nuclear dependence because they fear another catastrophe.

There are also demonstrations over suggested changes to the Japanese constitution that would allow the country to place peacetime support troops in hotspots around the world, amid concerns that the nation could return to imperialism. And during my stay, TV stations fretted about the latest taunts from North Korea. Lesser fears occur in everyday life. A few years ago, I saw an episode of the Japanese TV panel show Dead or Alive that warned of how miso soup could explode when reheated in a copper pan.

Japan is an amazing country: culturally rich, a world power despite its need to import much of its manufacturing resources, and still strong economically even after decades of stagnation. But beyond the Yamato spirit that pushes it forward, there is something else that seems to hold it back: fear. Fear makes itself known in the small moments of daily life, and in major issues that affect national policy. From concerns over nuclear energy, to the impact of one alcoholic beverage consumed hours before, Japan is awash in fear.

It wasn’t always like this, of course. Before World War II, the fear went in the other direction. But sometime between 1945 and today, the country changed from an imperialistic world force to a kindly old grandmother. The reasons for this are certainly complex and decades long, but the change from fearless to fearful is real and noticeable. Fear over a drunk driving charge might be simple compassion for another person’s well-being. But fear that influences national policy can negatively impact an entire nation.

A similar change seems to be taking place now in the United States. While once our nation was known for its rugged individualism and can-do spirit, the general sense today is that without the significant infrastructure and management support provided by the federal bureaucracy, our society would cease to exist. The nightly news regularly announces the danger-of-the-day, especially anything that poses a threat to health and basic safety, from changes in the weather to poor quality children’s toys. Many Americans don’t just dislike Donald Trump and his policies; they fear him. They daily expect sudden death from a lack of health insurance, or deprivations from having to start out a career at the minimum wage, or imprisonment from supposedly fascist policies, or worse. All of these concerns stem from fear, and as with the concerns of my beer-drinking friends over my driving abilities, these recent American fears are founded on irrationality.

Decades ago, despite concerns over Russian aggression and nuclear war, the typical American still believed that the United States would eventually prevail over that “evil empire.” We went to the moon, and we told Mr. Gorbachev to Tear Down That Wall. Today, a mundane email hack has caused many to believe that permanent domination of our nation by Russia is imminent and lethal. We now cower were we once stood firm, and for little more than a few news reports of electronic malfeasance and the timing of conversations between American and Russian political functionaries.

While fear is a normal human reaction to extreme situations, its regular invocation from even humdrum news events is unhealthy for any society. Fear is a common tool of tyrants and bullies, and nations have been prone historically to making fatal choices, all because some leader or group claimed to be able to assuage their fears. Until we, as a nation, recover our backbone in dealing with the routine pressures of everyday life, we leave ourselves open to this same danger.

[Image Credits: Wikimedia Commons]

April 4, 2017

Fake News, Fake Conclusions

Fake news is all the rage these days. Whether the source is a tweet by Donald Trump, or the musings of some web site of questionable impartiality, anything that smacks of propaganda, or that includes outright lies, or that engages in what a previous generation would have called “spin,” is deemed to be fake.

Fake news is by no means a new phenomenon. In the days of the early Christian church, the Eucharistic terminology of “body” and “blood” quickly transformed into published accusations of cannibalism. The U.S. presidential campaign of 1800 is famous for the fraudulent nature of journalistic attacks on both Adams and Jefferson. The sensationalism of Pulitzer’s and Hearst’s yellow journalism, while perhaps not a direct catalyst for the Spanish-American War, at the very least cemented certain false ideas about the conflict in the minds of readers.

One key difference between the fake news of the late nineteenth century and today’s fake news is the now near-instantaneous ability to corroborate the underlying facts of the story. Don’t trust what you read on some web site, or in a White House press conference? A visit to Snopes, or PolitiFact, or FactCheck.org will right the wrong in no time—assuming that you trust the verifier.

Fake news is pernicious, but for those who take the voting franchise seriously, verification of official pronouncements is a vital step in understanding the state of the nation. And even if you fall for a false news story, some in-your-face social media acquaintance will correct the error of your ways within a day or two.

So, fake news, when corrected, isn’t really a large obstacle to a stable society. But fake conclusions—false ideas you will refuse to correct even when given correcting data—are much more troublesome. Sometimes, we hold fake conclusions out of sheer obstinacy or for political gain. The years that Trump carried the torch for the Birther Movement appears to have no other purpose. But even worse than intentional self-deception are those situations where we have given up completely on any desire to find the truth, when the comforting lies fall in line with our worldview.

I discovered one surprising bit of data related to fake conclusions in Basic Economics, the financial primer by economist Thomas Sowell. In Chapter 10 of the book’s Fifth Edition, which covers productivity and incomes, Sowell introduces the shocking fact that some of our highly touted income statistics are just plain wrong. In addressing incomes as distributed across the range of American households from poor to rich, he says, “A detailed analysis of U.S. Census data showed that there were 40 million people in the bottom 20 percent of households in 2002 but 69 million people in the top 20 percent of households.”

What does this truly boring statistic tell us? It says that when you hear income comparisons between the top X percent of households and the bottom X percent of households, the data is including vastly different counts of household individuals. But beyond this basic difference, Sowell submits a pile of studies and IRS data to show that the number of people working in each of those households also differs significantly between the upper and lower quintiles. “When it comes to working full-time the year-round, even the top 5 percent of households contained more heads of households who worked full-time for 50 or more weeks than did the bottom 20 percent. That is, there were more heads of households in absolute numbers—4.3 million versus 2.2 million—working full-time and year-round in the top 5 percent of households compared to the bottom 20 percent.”

Sowell isn’t making a judgment about who appears in each strata—though he does that elsewhere, when he shows that movement out of the lowest 20 percent of households is due to a much larger increase in incomes than what is experienced by those at the top. And this isn’t an issue of telling the poor to deal with it, since according to the data, they do deal with it, and rather successfully as they move up the economic ladder, in many cases joining the upper 20 percent.

Much of what passes for fact, including the idea that “the rich are getting richer and the poor are getting poorer,” is based on faulty statistics or a misreading of the core data. Poor households tend to be young, unmarried, low-skilled, entry-level individuals, whereas households in the upper income ranges usually have older working professionals whose incomes benefit from being in a career for decades, and who started out their adult lives as young, unmarried, low-skilled, entry-level individuals.

Unfortunately, we live in a time where the level of analysis that Sowell has done with the data is disregarded, not because it’s filled with fake news, but because it conflicts with deeply held fake conclusions. Such conclusions cause us to make extremely poor pronouncements about a wide range of public policy issues. Until we are willing to fess up to our distorted false conclusions, all the true news in the world might as well be fake.

[Image Credits: flickr/purdman1]

March 28, 2017

Surviving in a World of Partial Information

It seems we have overcome our most recent national nightmare concerning healthcare. Advocates of the Republican’s “American Health Care Act of 2017” are crying themselves gently to sleep, while those who opposed the bill are gaining significant muscle mass from all the fist-pumping. Support for the bill was admittedly low, with a recent poll identifying support among only 17% of Americans.

Before the GOP removed the bill from consideration, the internet nearly collapsed under the collective moaning concerning the damage it would bring. And while there were certainly a handful of policy wonks who could glean accurate information from the text of the initial bill, most prophecies of civilization’s end were based entirely on rough extrapolations and hearsay. Don’t believe me? Here’s a chunk of text from the first few pages of the proposed bill.

“Notwithstanding section 504(a), 1902(a)(23), 1903(a), 2002, 2005(a)(4), 2102(a)(7), or 2105(a)(1) of the Social Security Act (42 U.S.C. 704(a), 1396a(a)(23), 1396b(a), 1397a, 1397d(a)(4), 1397bb(a)(7), 1397ee(a)(1)), or the terms of any Medicaid waiver in effect on the date of enactment of this Act that is approved under section 1115 or 1915 of the Social Security Act (42 U.S.C. 1315, 1396n), for the 1-year period beginning on the date of the enactment of this Act, no Federal funds provided from a program referred to in this subsection that is considered direct spending for any year may be made available to a State for payments to a prohibited entity, whether made directly to the prohibited entity or through a managed care organization under contract with the State.”

If you tell me that you know what that means, or how it will impact your life, you’re lying. If you posted dire warnings on Facebook about the bill’s impact, you didn’t do it based on a reading of the bill itself. Nobody does. I read through parts of it, and even I would never make such a claim, having given up long before I reached the end.

Certainly, it’s not reasonable to expect that all Americans have the time or the legislative background to extract core truths from such a text, and it’s common to depend on policy experts for interpretations of law. But if we’re honest with ourselves, we know that’s not how we came to our decisions. Few people today, especially the most vocal, bother to delve into the minutiae of governmental policy, or take time to understand core concepts like the basic economics of supply and demand, how healthcare capitation works, or how regulations differ from law.

We live in a political world of partial information. Instead of taking time to understand key political arguments concerning public policy, we grab a few talking points from our one or two go-to web sites, wrap it up in a fact-free infographic, and embark on a shoot-first-ask-questions-never campaign of destroying those who disagree with us.

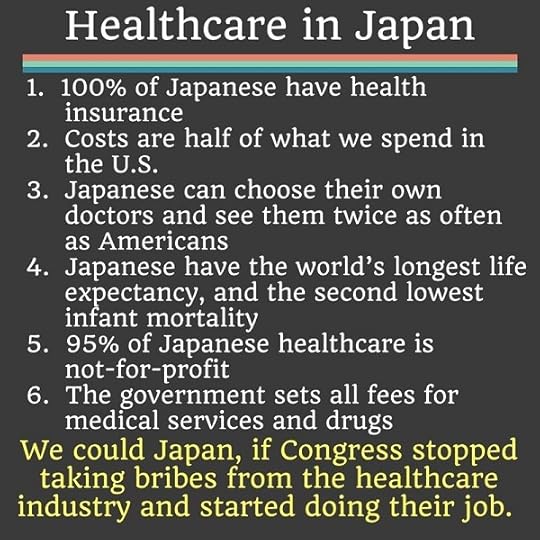

Consider the following healthcare-related image that popped up in my social media feed this weekend.

It’s taking every ounce of my being not to obsess on how the author turned Japan into a verb (“We could Japan…”). Four of the points are patently false—only items 4 (life expectancy) and 6 (fee schedules) appear accurate. But even overlooking these flaws, the chance that this image designer had any intimate understanding of the Japanese healthcare system is nil. Any details used to build the list came divorced from the realities of the Japanese medical system. While healthcare in Japan is certainly first-world, it differs from the US system in ways that make direct comparisons difficult. Japan and the US have variant outlooks on healthcare; make different end-of-life decisions; have a near-opposite mix of general practitioners and specialists (only 33% GPs in the US, closer to 55-60% in Japan); and have divergent family dynamics, work environments, social customs, diets, and priorities that all impact life expectancy and medical services.

Hospitals in Japan are nonprofit by mandate, and doctor fees are strictly limited. This may sound wonderful, but it impacts the system in ways that most Americans would find constraining. Without the profit motive, there is limited interest in building large hospitals outside of university settings, and most healthcare takes place in small, local clinics. It’s not uncommon in Japan to find a sole practitioner in a neighborhood clinic with a half-dozen overnight-stay beds. And those beds get used, since with the low reimbursements on procedures themselves, doctors must make up the costs by treating their clinics as hotels, requiring patients to stay multiple nights for procedures that would be considered outpatient in the US. Providers often see more patients than US doctors, naturally spending less time with each one. The limited number of large hospitals with active emergency rooms means that ambulances may need to travel to multiple clinics before finding a doctor willing to accept a patient with expensive, low-reimbursed needs. Health insurance is paid by a mix of company and government plans, but with the bursting of the Japanese bubble economy and fewer guarantees for lifetime employment, more people depend on the government systems. And with the current labor shortage and the rise in average citizen age, healthcare system costs as a percentage of Japanese GDP are expected to double between 2011 and 2035.

Again, none of this means that healthcare in Japan is poor. But it does mean that the person who sought to use Japan as an exemplar of healthcare perfection had no clue about the in-country realities. The information input was partial, and the output was worse. But today this passes for in-depth analysis.

Americans seem to have a compelling need to boil every problem down to a single control, a lone knob that, if spun to the correct setting, will eliminate all suffering. Government programs live for this type of one-size-fits-all solution, but we extend this methodology into other life areas as well. We engage in an unending quest to find that one dietary change that will allow us to lose weight, live longer, and stay wrinkle-free, all without the need to alter our general eating or exercise habits.

Got a problem in the inner city? The key is racism. Issues with your income? Your excessively rich boss is probably a sexist. Imperfect schools? Better get on board with Common Core. No matter the problem, we boil the issue down to a single idea, and if possible, a single word that simultaneously states the problem and the solution.

Despite this madness for easy answers, we still have poverty, and healthcare woes, and international conflicts, and religious squabbles, and loathsome politicians. We will always have these things, because humans are messy and complex. Every time we tell ourselves that people aren’t that complicated, and that the right leaders or the right healthcare system or the right government program will bring us relief, we fall for the lie that a little knowledge is a beautiful thing.

[Image Credits: pixabay/Mediamodifier]

March 21, 2017

The Patriot Who Could Have Replaced Jefferson

Beyond their import in moving the colonies towards liberty, the words of Thomas Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence remain, even today, a zenith of American prose. Phrases like, “When in the course of human events,” and, “we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor,” not only explain the situation in a terse collection of well-chosen words, they trigger something within the human heart beyond what a news article on the same subject would provide. John Adams rightly praised Jefferson for his “peculiar felicity of expression,” but Jefferson wasn’t alone in his ability to crank out a lovely sentence.

Had he lived to attend the Second Continental Congress, Joseph Warren of Massachusetts might well have replaced Jefferson as the key architect of the Declaration of Independence, at least based on his ability to craft elegant yet persuasive statements. A well-respected Boston physician and a direct descendant of Mayflower luminary Richard Warren, Joseph Warren was a rising star in the liberty movement. He was a leader in the Sons of Liberty, and numbered John Hancock and Paul Revere among his closest associates.

Warren is best remembered for his participation and subsequent death in the Battle of Bunker Hill, in June of 1775. Although the cause of his death was from a single musket shot, accounts of how far the British went to mutilate his body after death are excruciating. His family was able to identify his body only through the presence of a fake tooth he obtained earlier in life. General Warren’s death was a troubling military loss for the patriots in their cause, but the loss of Warren’s writings and influence were likely greater.

Less than a year before his death, and in response to Parliament’s 1774 Intolerable Acts, Warren drafted The Suffolk Resolves. The document advocated resistance against the Acts, what he called “attempts of a wicked administration to enslave America.” Between the passage of the Stamp Act in 1765 and America’s official break with Britain in 1776, indignant Americans generated a regular stream of anti-Parliament statements, some blunt and violent, some polite and reasoned. Among these writings The Suffolk Resolves stands out as a striking example of emphatic yet grand rhetoric.

I came across Warren’s Resolves while researching materials for my upcoming book on the Declaration of Independence, and it was a refreshing break from the standard lists of colonial complaints against Parliament. Crafted as an official political statement by the cities and towns of Suffolk County, Massachusetts—such bureaucratic gatherings are normally meat grinders of bland lawyerly pronouncements—Warren’s plea begins by pitting the self-reliant and oppressed Americans against their unjust and sinful British overlords.

“Whereas the power but not the justice, the vengeance but not the wisdom of Great-Britain, which of old persecuted, scourged, and exiled our fugitive parents from their native shores, now pursues us, their guiltless children, with unrelenting severity:

“And whereas, this, then savage and uncultivated desart [sic], was purchased by the toil and treasure, or acquired by the blood and valor of those our venerable progenitors; to us they bequeathed the dearbought inheritance, to our care and protection they consigned it, and the most sacred obligations are upon us to transmit the glorious purchase, unfettered by power, unclogged with shackles, to our innocent and beloved offspring.

“On the fortitude, on the wisdom and on the exertions of this important day, is suspended the fate of this new world, and of unborn millions. If a boundless extent of continent, swarming with millions, will tamely submit to live, move and have their being at the arbitrary will of a licentious minister, they basely yield to voluntary slavery, and future generations shall load their memories with incessant execrations.”

Writers like Jefferson and Warren drew upon the styles and themes of the masters who came before them. American historian Stephen Lucas documents how “Jefferson systematically analyzed the patterns of accentuation in a wide range of English writers, including Milton, Pope, Shakespeare, Addison, Gray, and Garth.” These same forms and appeals appear in Warren’s text. You can see this in the stair-step repetition of “on the fortitude, on the wisdom and on the exertions,” and in the opening contrasting couplets: “the power but not the justice, the vengeance but not the wisdom.” Warren also invokes biblical themes, asking if the colonists would “tamely submit to live, move and have their being at the arbitrary will of a licentious minister.” Here, he negatively compares the British leadership to the righteous Creator mentioned in Acts 28, the “God that made the world and all things therein,” and in whom “we live, and move, and have our being.”

It’s mere speculation to assume that Warren would have replaced Jefferson on the Committee of Five that drafted the Declaration. But the selection of Warren’s good friend John Hancock as President of the Continental Congress, just a month before Warren’s death, does prompt one to consider the rhetorical possibilities.

[Image Credits: Portrait of Joseph Warren, by John Singleton Copley, 1765, from the collection of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, image in the public domain]

March 14, 2017

The National Endowment for the Arts Must Die

Art is important. As a natural expression of human creativity, artistic endeavors enrich our lives, brighten our neighborhoods, and in some cases, even raise our property values. Art is all around us: in homes, in businesses, in seemingly random places. I can’t imagine a world without art.

The same could be said of roofs. Or cars. Or cell phones. Or ice cream cones. There are myriad things that enrich our lives, add to our culture, and in general make life more pleasant. But we don’t create federal government support organizations for each of them. Nor should we. Just because an industry strikes our fancy or benefits our lives doesn’t mean it deserves its own official conduit for national approval or taxpayer dollars.

The National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) came into existence through the National Foundation for the Arts and Humanities Act of 1965. The stated purpose of the overall Foundation was to “develop and promote a broadly conceived national policy of support for the humanities and the arts in the United States.” Under nebulous rationales like, “The arts and the humanities belong to all the people of the United States,” and, “Democracy demands wisdom and vision in its citizens,” the enabling legislation decided that “it is necessary and appropriate for the Federal Government to complement, assist, and add to programs for the advancement of the humanities and the arts by local, State, regional, and private agencies and their organizations.”

The question to ask is whether any of this is true or appropriate. One way of answering this is to substitute “art” with other ideas or items that Americans value. Would it be acceptable to create a government agency that broadly conceived a national policy of support for flat-screen TVs, or youth soccer programs, or queen-size fitted sheets, or Dockers khaki pants, or lawn care products, or anything else normally purchased and enjoyed by individuals and businesses? Some might argue that art is categorically different, and that without a unified national voice, the country and its art expression would suffer. But that’s highly doubtful, especially since the National Endowment for the Arts came about as a response to the already vibrant artistic activity found across the nation, in “local, State, regional, and private agencies and their organizations.” The NEA didn’t create art; art led to the NEA.

Art is important, but is it an appropriate job for the federal government to validate or support that art? Hardly. While a society is free to direct taxpayer funds to any purpose it deems important, the collective sponsorship of the arts is not a necessary function of a society. According to British jurist William Blackstone, “the principal aim of a society is to protect individuals in the enjoyment of [their] absolute rights.” He breaks those absolute rights down into the three distinct categories of personal security, personal liberty, and private property, providing the overall right to do what you want, when you want, and where you want, with your own stuff, all without worrying about getting maimed or killed for doing so.

These rights, when not constrained by government, provide artists with the full freedom to create, promote, distribute, and even destroy their own works. While this freedom is guaranteed when not limited by law, there is nothing in these rights that guarantees success or income or affirmation for an artist. Your rights allow you to create art; they don’t require that anyone will like it.

But that’s what the National Endowment for the Arts does: it set up a government body that likes specific works of art. Of course, that’s not the official purpose, and the enabling legislation warns that “the Government must be sensitive to the nature of public sponsorship.” But given its limited budget (less than fifty cents per American per year) and its wide sphere of duties, it will naturally assess and approve some works as being more in line with the policies of the agency than are other works. The law is sometimes very specific about the types of works and artists that the Endowment deems important, including artists from “underserved populations.” It also, for example, prioritizes jazz music over other forms, with its inclusion of the American Jazz Masters Fellowship. Why aren’t blue grass, disco, funk, and baroque musical forms afforded the same level of recognition?

What government approves it can also disapprove. The 1965 legislation has specific language prohibiting financial assistance for “obscene” art. The Endowment garnered much controversy over the years by welcoming artists such as Andres Serrano and Robert Mapplethorpe, but also had sponsorship of questionable art forced upon it through the “NEA Four” lawsuit in 1990. Public standards of decency have changed dramatically in recent decades, but the fact that relatively mundane works by Marcel Duchamp and other Dadaists a century ago were labeled as “obscene” makes nationwide agreement on the merits of a given work of art a dubious practice, even when an “average person, applying contemporary community standards” is questioned.

Donald Trump isn’t the first president to propose elimination of the NEA, but it’s finally time to do it. And that quote from the previous paragraph on how obscenity is defined holds the key: “applying contemporary community standards.” Like education, food preferences, and job markets, art is a local concern. Things that pass for art in New York City may be unacceptable to those in a small Midwest rural township, and vice versa. Beyond community standards, the focus on art at the local level can have an impact on the economy and on education in ways that an NEA grant can never hope to achieve.

Consider Leavenworth, a small town of about 2,000 people nestled in the mountains of central Washington State, about a three-hour drive from Seattle. The town thrives on tourism, driven by the city-mandated use of Bavarian architecture and art in its central business district. For instance, its municipal Sign Code for national franchises says that, “logos of chain or franchised businesses are prohibited, but shall be allowed if modified to incorporate graphics, colors, and Bavarian lettering styles and modified to utilize the Old World Bavarian Alpine theme as approved by the design review board.”

Through outdated European themes, an annual community production of The Sound of Music, and other kitschy programs and presentations that would make a grown New Yorker cry, the former logging town was able to rescue itself from financial ruin. Bill Wadlington, the principal of the city’s Cascade High School several years ago, insisted that “the biggest change agent for arts education in our high school was our community. We have a large number of organized people and local artists who value the arts. I think that when you have a group of artists in a community and they start talking with their feet and hands, parents follow suit.”

Does Leavenworth’s Bavarian business center represent the height of artistry? No way. But it is still ars gratia artis, and has a tremendous impact on the lives of those in that town. It’s all done locally, and all without the need to be approved, supported, or nudged by a federal agency.

[Image Credits: pixabay/skeeze]

March 7, 2017

How to be Created Equal

Equality is a defining American value. Based on the Declaration of Independence’s core statement that “all men are created equal,” Americans today expect conformity with a growing laundry list of egalitarian must-haves: equal pay for equal work, racial equality, marriage equality, and now equal rights for undocumented immigrants. As a nation, we’re awash in calls for equality. And while many of these demands are well-intentioned and even worthwhile, they have little to do with Jefferson’s “created equal” reference.

Much of what passes for equality today is based on circumstance. Recent calls for economic justice pit the haves against the have-nots, all predicated on the belief that if you can put people in the same circumstance, they will be equal. But the Declaration’s mention of equality is not based on circumstance. Jefferson, of all people, understood that the situations of individuals varied widely, and often in unjust ways. As a member of the Virginia gentry and a slaveholder, he saw firsthand the differences between the upper classes and those who were bought and sold as property. Jefferson also viewed the role of women as inferior when it came to things like the public sphere, glad to see that they were “contented to soothe and calm the minds of their husbands returning from political debate.”

Despite his acceptance of circumstantial inequality, Jefferson and others of that era still insisted that all men—rich, poor, male, female, slave, free—were created equal. To understand this disconnect, we must look at the words that Jefferson used in the Declaration, and the philosophy behind them. One of the most important words used in that phrase is one that is often overlooked: the word “are.” Men “are” created equal.

Jefferson didn’t say that he hoped people would be equal, or even that they deserved to be equal. They are equal. It’s a declaratory statement, one not made by a mere mortal like Jefferson, but by the divine Creator, who also established inalienable rights to go along with that equality. Society doesn’t make people equal; they already are equal, and each possesses some innate qualities that makes them that way. William Blackstone, the great British legal scholar, called these inborn elements the “absolute rights of individuals,” facets of our humanity that “every man is entitled to enjoy whether out of society or in it.”

John Locke in his Second Treatise of Government, expounded on these absolute rights as they existed in a “state of nature,” that is, when there is no government in place to manage or restrict them. For Locke and others of the Enlightenment era, all men were equal “in respect of jurisdiction or dominion one over another.” In that state, all humans possessed the God-given right to control their “natural freedoms”—freedoms of life, liberty, and property—as they desired, “without being subjected to the will or authority of any other man.” In such a state of equality:

“all the power and jurisdiction is reciprocal, no one having more [power and jurisdiction] than another; there being nothing more evident, than that creatures of the same species and rank, promiscuously born to all the same advantages of nature, and the use of the same faculties, should also be equal one amongst another without subordination or subjection.”

The equality we are created with is one focused on freedom, the freedom to enjoy the liberties that we possess in the absence of any authority, relationship, or society. Governments exist to constrain that liberty, because men in a state of nature are apt to use their liberties in ways that encroach upon the liberties of others. The American system was designed to constrain liberty to the minimum extent possible, allowing individuals to enjoy as much of their innate freedom as society might endure.

At least, that was the plan. Back in Colonial America, the hunger for absolute rights outweighed any call for circumstantial equality. In the Boston Pamphlet of 1772, Samuel Adams and his associates invoked this preference when they declared, “We are not afraid of Poverty, but disdain Slavery.” Today, that sense of inborn equality has been increasingly replaced with a radical egalitarianism, a demand for situational equality that encroaches on every liberty. Each time the government adds a new regulation, or defines new legal rights, or passes federal laws that override state and local equivalents, we move a little bit further from the Enlightenment understanding of equality.

That’s not to say that all of these government actions are wrong. A society is free to choose the level of constraint that it finds most comfortable. But we should not delude ourselves into thinking that such limitations are done in a vacuum, or that they are exclusively positive. The closer we get to the ideal of America’s founders, that of finding the sweet spot of minimum interference and maximum freedom, the closer we come to our God-given equality. But if we drift too far the other way, we may utter the cry of Adams and other colonial Bostonians: “The Iron Hand of Oppression is daily tearing the choicest Fruit from the fair Tree of Liberty.”

[Image Credits: pixabay/Aenigmatis-3D]

February 28, 2017

Power: It’s Not Just for Monarchs Anymore

During a recent political discussion on—where else?—Facebook, a friend of a friend made the following shocking claim: When America’s founders warned about the concentration of power in government, they were speaking only of monarchs. The framers of our constitution, she insisted, did not appreciate King George III abusing his power, and so they set up a constitutional democracy where there was no need to fear such tyranny. For her, having no king meant having no tyranny. Additionally, she insisted that big government was the blessing of all blessings, since in its might it would be able to tear down those evil corporations that manipulate and destroy us day in and day out.

While she was the first person I have ever encountered who espoused this monarch-only view of power, a large segment of the American public loves big government. Some problems are too big for anything other than national public governance, they believe. For some—see above—the problem stems from corporations of any size. For others, the issue is healthcare, or failing banks, or the War on Drugs, or international terrorism, or safety in the workplace, or poverty, or a quality education.

Those who clamor for a national public solution insist that no effort by private entities, the marketplace, or local governments will suffice. And like my second-tier Facebook friend, they put their full faith in the government, believing that it will in all ways act for the benefit of its citizens. Such faith is rooted in three core ideas about government.

If you can structure the government just right, and choose a wise leader, things will eventually work out.

Activities done in the public sphere are purer than those done by private enterprise, because the motives of elected officials are purer than those of business owners.

A central government is the ideal source for protecting rights and issuing meaningful leadership.

The concept of an ideal state led by a wise, caring leader comes straight from Plato and his classic work, The Republic. In that book, Plato invokes Socrates to describe a Utopian state, one where a wise philosopher-king oversees the highly managed lives of the citizenry. Plato believed that such a government would not only ensure justice, it would also provide the highest level of national happiness—even if individual citizens were miserable. As with those who advocate large governments today, Plato believed his state provided the best defense against tyranny and the whims of the masses.

The second ideal, that public works are more noble than private, has a similar root, one of distrust of the common man. Self-interest runs strong in the human animal, and an authoritative government is seen as a bulwark against the tumults of powerful men, especially corporatists. To that end, the government must provide strong leadership over its citizens, protecting the weak from all harm, and ensuring a nation of safety where dignity and equality reign.

In short, it’s everything the Founders feared most. They rejected the idea of a trustworthy government. Jefferson summed up these rejections in the Declaration of Independence: “Whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends [to secure the rights of citizens], it is the Right of the People to alter or abolish it.” Governments exist to secure our rights, but the Founders were not foolish enough to expect that they would continue to do so without vigilance.

While the Founders paid homage to Plato, they ultimately rejected his ideal state for one based on natural law, a law in which all men equally possess the authority to craft their own systems of social governance. Under this structure, proposed by Cicero, the government does not grant rights, but secures pre-existing rights, and does so not to guard against the injustices of the common man, but by the authority of those common men.

Large central governments are no more trustworthy than small, weak governments. All can devolve into tyranny in the wrong hands. What is most surprising among big-government advocates is their recent horror at Donald Trump’s rise to power, the power that they had carefully and meticulously prepared for a benevolent like-minded leader, the kind of power that it takes to “fundamentally transform” a nation like the United States. Until they come to realize that a government is only just to the extent that it secures the rights of its citizens, they might as well be living under a dictatorship.

[Image Credits: pixabay/ErikaWittlieb]

February 21, 2017

Succumbing to our Fears

In his first inaugural address, while America was still plunged in the depths of the Great Depression, President Franklin Roosevelt declared, “The only thing we have to fear, is fear itself.” It was a bright message for a dark time.

When the speech took place in 1933, unemployment was close to twenty-five percent, and almost half of the nation’s banks had failed. The global war and the influenza pandemic from two decades earlier were still fresh in people’s minds, and the future seemed equally bleak. Hitler would be appointed chancellor of Germany ten days after FDR’s speech, and the Dust Bowl droughts would start a year later, quickly followed by a second world war that would kill more than fifty million. Technical advancements in communication and manufacturing gave us cheaper goods and easier access to the wonders of the globe. But they also enabled swift, efficient death. Dour nineteenth-century German philosophies reminded us of how wretched people could be, and the political systems that stemmed from those beliefs did not disappoint, with communist and fascist leaders summarily executing millions of innocents under their control.

It was a sad time, filled with violence, starvation, oppression, pestilence, and turmoil. Despite all of this carnage, we survived. Humans are an indefatigable race, rising again after every beating and injustice. And America is no exception. The charters of our freedom came about in response to oppression and tyranny. While the experiences varied from colony to colony, the impact of that tyranny was felt across the region. British soldiers marched through the streets, entering colonial homes by force, pillaging at will. The government was no help, with Parliament and the king routinely shutting down local legislatures, and arresting those who pointed out the constitutional violations. As Jefferson said so eloquently, the king “has plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.” Eventually we regained our freedoms, but at great human cost.

Americans today are the beneficiaries of those valiant struggles. The tired, the poor, the huddle masses yearning to breathe free rushed to our shores, knowing that blessings awaited. Through blood, sweat, and tears, they gained access to those blessings. By any historical measure, we are the richest, freest, safest, and most powerful nation that has ever been. It’s not Utopia, but life for the average citizen in this country can honestly be described as good.

Despite all this, we as a nation are drowning in fear. Our incomes are up, but we fear economic collapse. Our life expectancy is double what it was at our founding, but we fear sudden death and suffering from the latest food additives. Through the phones in their pockets, our kids have instant access to the totality of human knowledge, but we fear the smallest cuts to school funding. We’ve overcome epidemics like polio and smallpox, but fear the very vaccines that made those victories possible. Even the poor among us have ready access to cheap transportation, entertainments galore, and nutrition to the point of obesity, yet we fear the injustice of a mediocre income. We ridicule our leaders, march in the streets by the millions, burn our flags, and mock our institutions, all without even a hint of concern from police and politicians, yet we fear being locked up and silenced by a fascist regime. Blacks fear whites. Whites fear Muslims. Muslims fear Trump.

The presence of social media seems to have ramped up the level of fear. Here are just a few of the fears I witnessed this past week (with edits for readability).

“Our new Fuehrer [Trump] and his KKK and American Nazi supporters want to destroy our beloved Constitution and silence the media and all who dare to condemn his racism and hatred of women, all Mexicans, and all Muslims.”

“The intolerant traitor Republicans want to replace democracy with a tyranny that will shut up anyone who dares to disagree with them, want to kick out millions of hard-working immigrants with children in college, want to kill almost anyone who is not pure white, want to force more abortions by making any type of birth control a crime, and want to cozy up to Russia so they can make even more billions.”

“People who complain about government only want to take away our Social Security and Medicare.”

“The current Republican philosophy is to protect businesses so that they can work you as hard as they can, and drain your elderly bodies and assets. If the government does not regulate working conditions, workers could die…then you have NO liberty…you are dead!”

“Without the TSA, anyone will board a plane with a gun anytime they want.”

“Without government regulations, chemical companies would inflict poisons, cancer, and toxic waste on citizens, auto companies would make cars that blow up, airlines would let flyers board dangerous aircraft, food companies would serve us carcinogens, and factories would install equipment that could chop off the hands of workers.”

“If you think we shouldn’t have universal healthcare coverage, it means you are OK with people dying in the streets. Americans would get into auto accidents and have no place to go. They would literally die in the streets.”

“If a company has a choice to either dump toxic waste in the nearby stream late at night FOR FREE, or travel 100 miles to dump it at a safe site, what do you think that business owner is going to do? Are you OK with having thousands die of cancer?”

Americans in the early 1930s had ample reasons to fear. There was a fairly good chance you wouldn’t eat on any given day, or find a job, or recover from a high fever, or see your sons return from war. None of those widespread dangers exist today. And yet, we fear. America in the twenty-first century is awash in panic and hysteria. I worry about what will happen to us when something arrives that actually should be feared.

[Image Credits: pixabay/ErikaWittlieb]

February 14, 2017

Understanding Fascism

Donald Trump’s electoral victory has bought with it a heightened level of vitriol and name-calling. Democrats, and even a few Republicans, have issued blanket accusations against Trump, his cabinet, and anyone who either voted for him or wore a dress to the Grammy’s with the words “Great Again” incorporated into the design.

Along with the traditional left-wing taunts of “racist” and “homophobe,” there is a new charge against Republicans in general, and the president in particular: “Fascist.” This denouncement isn’t limited to a few crackpot accusations tossed into the comments section of YouTube videos. It’s now a mainstream cry from those on the Left. Vanity Fair columnist Michael Kinsley, writing an op-ed in the Washington Post a few weeks after the election, began without equivocation: “Donald Trump is a fascist.”

Fascist, of course, means Hitler. The invocation of Godwin’s Law even before Trump took office seems extreme, but those who oppose The Donald believe they are speaking truth. But are they? Is Donald Trump a fascist?

That question, it turns out, is not so easy to answer. Unlike the terms “capitalist” and “communist,” with their relatively clear-cut econo-centric definitions, “fascist” as a concept is hard to nail down. Part of the problem is that the societies traditionally associated with fascism—Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and Italy under Mussolini—imposed different governmental and cultural standards. But political theorists have had decades to analyze the movement, and have come to some conclusions about what makes fascism tick.

At its core, fascism is a power-hungry move toward centralized, unchecked control of national interests, and against those political, social, and economic systems that would distract from that goal. Fascists tend to be anti-democratic, anti-Marxist, anti-Establishment, and yet they are not opposed to using any elements from those opposing worldviews to advance their agenda.

Roger Eatwell, a professor of politics at the University of Bath and author of Fascism: A History, defines a “fascist minimum” as having four distinct elements:

Nationalism, an overarching ideal of national identity that is not necessarily tied to any specific ethnic group or geopolitical boundary;

Holism, the placement of collective interests above those of the individual, though in a way that rejects classical liberalism and the democratic concepts it engenders;

Radicalism, an ends-justifies-the-means view of establishing a “new political culture” that is distinct from populist ideas of a mythical past; and

The Third Way, a middle-road between individualism and socialism that attempts to draw on elements of each.

For the fascist, an all-encompassing national identity dictated by a central authority is key. Fascists tend to prefer a mixed economy, where some industries are owned by the government, while others are held in private hands, with the caveat that private control exists to build up the authority of the state. Fascists are violent, partly as a temperament, and partly due to an openness to using any means necessary to achieve their goals, unconstrained by things like morality and law. In a fascist system, all loyalty belongs to the state as an ideal, and to the leader who runs that state. It is a cult of leadership, propelled by violence, with the end-game being the enhancement of Utopian nationalism.

This litany of fascist elements is not perfect or even universally accepted. Some academics, including Israeli historian Zeev Sternhell, place Hitler’s Nazism outside of fascism proper, due to its focus on a pure race that takes precedence over concerns of a central state. But despite these quibbles, fascism as a political ideology is a violent, all-controlling, nasty system that is worthy of condemnation.

The core question, though, is whether Donald Trump and his supporters adhere to the pattern of fascism. Certainly, there are some aspects of Trumpism that could be shoehorned into the above definitions. His “drain the swamp” call is classic anti-Establishment. He sings the song of national patriotism with his “only America first” policy. And his economic protectionism, which evokes the self-sufficiency of past fascist states, raises all kinds of concerns that go beyond mere political ideals.

But similar fascist sentiments could be linked to Barack Obama. As president, he was not opposed to bringing an entire industry under the collective umbrella of government if it served the national interest. He was flexible in his view of sovereign borders, perhaps promoting an idealized nation that transcended official state boundaries. And while he claimed to reject outright socialism, he also eschewed the rich-poor divide that always comes from a culture of individualism.

Obama was no fascist. Attempting to place him in that camp by hyperbolizing edge cases is dishonest. Using such tactics against the current president is just as dishonest, and makes a serious discussion of his policies impossible. When applying the label of fascist to a leader, you must take into account the most disturbing elements of that system, and determine whether the target of those accusations falls in line with those elements. While Trump’s boorish temperament and his ease in using Executive Orders are troubling, an honest comparison of key ideas shows that his actions to date are far from fascist.

Fascism rejects individualism, since it does not serve the purposes of the state. Trump is all about individualism, and a key accusation against him is that he makes the rich richer and more powerful, out of the reach of state interests.

Fascism seeks a central authority, free of checks, and heavy on the regulations that allow the state to oversee all aspects of a society. Trump’s anti-regulation and small-government perspectives make a drive for such concentrations of power difficult to achieve.

Fascism demands that societal institutions enhance the state. Republicans—and now Trump under the Republican banner—have long insisted that family, church, and private enterprise are superior to the state, especially at the national level.

Fascism employs radicalism and violence to advance its goals. A quick look at any TV screen will show that the radicalism and violence are tools of the Trump opposition.

Today’s charges of fascism look a lot like the warnings of an impending theocracy during the 1980s, back when Evangelicalism was a rising political faction. Leftists never explained how a shrunken federal government with more diffused control would accomplish the imposition of Christian dictates by force. The same is true with the current bout of mudslinging. Fascism requires a strong central authority. But by covering himself in the cloak of Republican populism, Trump is advocating, and even implementing, a state with a reduced footprint, one that will increasingly have trouble imposing its will on states and communities.

Calling the current administration “fascist” sounds scary. But the core “We don’t trust the government” principle advocated by Republicans is anathema to everything fascism stands for. If Trump’s detractors are serious about tying him to fascist principles, they will need to come up with a lot more than his bad attitude, or anger over an already-paused Executive Order.

[Image Credits: flickr/Johnny Silvercloud]