Tim Patrick's Blog, page 8

February 21, 2018

The Aggravation of Complicated Truths

What causes ordinary, caring people to use outright lies and deception to promote their political views? We naturally expect such behavior from our politicians or corrupt business leaders. But the act of using falsehoods and embellishment to persuade others is now the domain of the common man. How did this happen?

Let’s try to understand the issue by examining one of the most enduring fibs of our modern American experience: the gender wage gap. The standard narrative is that women earn about 79 cents for every dollar earned by a man. Fortunately, the comparison is completely false, with American women actually earning on average about 95 percent of what men make, given equivalent work situations. Not perfect, but not 79 percent. And yet the false value persists. Why do so many Americans cling to open error?

Meet Frank, a 19-year-old community college student living in Seattle. He dreams of becoming a computer engineer, designing the next breakthrough Internet of Things device. But for now, he studies English and calculus by day, and delivers pizza five nights each week in his seven-year-old Hyundai. His schedule allows for 35 weekly work hours, and thanks to minimum wage mandates in Seattle, he earns a sweet $15.45 per hour. Drivers also collect tips, amounting to hundreds of dollars per week. All told, Frank has an annual income of around $40,000, before taxes. It’s not an amazing salary, but since his parents pay for his tuition and basic college expenses, it provides plenty of money for his favorite hobby: skiing.

Meet Jenny, another Seattle resident, age 59. She won last November’s mayoral election, a change in jobs that brought with it a city-mandated hourly wage of $93.48. That equates to about $195,000 per year if you assume 40 hours per week, which is laughable given her packed schedule and the high-pressure environment. A corporate lawyer before the election, Jenny has an estimated net worth of $5.75 million, and she recently sold a home in north Seattle for $4.3 million (thank you, Amazon).

Is it fair that Frank only makes about 21 cents for every dollar earned by Jenny? Some hardcore communists would decry the disparity, but most Americans understand that an entry level pizza driver just starting out in the work force is going to earn much less than the mayor of one of America’s most progressive and active cities.

This example is obviously contrived. Salary comparisons between a career politician and an entry-level college student are clearly biased, because they don’t match up identical things. But if you accept the standard narrative that women in the United States make around 79 cents for every dollar earned by a man, you have fallen prey to precisely this type of false comparison.

The advertised wage gap is calculated by adding up all salaries from all working men in the United States—mayors, pizza drivers, and everyone else, regardless of age, experience, or job title—and then comparing that total to the salaries of all working women in America, using that same broad-brush approach. As a comparison of income disparity, it’s completely meaningless, just as meaningless as the Frank-Jenny comparison above, since it makes no allowances for type of job, education requirements, personal ambition, age, and other factors that influence salaries for noncontroversial reasons.

Despite the obvious emptiness of this wage-gap comparison, it continues to be accepted as gospel truth, and by people who should know better. Hillary Clinton used it as one of her major campaign planks during the 2016 election. An article in The New York Times during that timeframe discussed some of the assumptions that make the 79-cent calculation inaccurate, yet still used that same tortured math to visualize a “wage gap that women can’t escape at the bottom or the top of the pay scales.” Obviously, Jenny in Seattle was able to escape, but when you are only willing to look at salaries in the blandest aggregation possible, it comes as no surprise that you can’t get the right numbers.

What causes otherwise intelligent people to accept something so patently false? Or worse, what prompts them to spread the lie, even after they have been convinced that it is just a trick of statistics? One possible reason is nefarious intent. Some believe that this lie stems from leftists using whatever means possible to impose their failed worldview. It’s a comforting perspective for those on the right, but as an explanation, it’s no more useful than the wage-gap number, since it is based on false data. And I’m not cynical enough to think my Democratic friends have such malice in their hearts.

Perhaps it’s caused by ignorance, or by the influence of propaganda. That could explain some of the acceptance, but it’s a difficult sell when articles by major news sources, including those on the political left, admit that “the gap is often much smaller if you compare like to like.”

There is another reason, beyond malice and ignorance, why people accept falsehoods: the truth is just too hard to process or accept. This, it seems, is what is happening here. If the wage gap is only an outcome of poor statistical analysis, then you need to do the right analysis, bringing in the myriad reasons that researchers claim as the causes for the gap. And there are a lot of reasons, ranging from work choice differences between the genders, to the regional variations in job opportunities and wages across the country. Women work part-time jobs at twice the rate of men, and for those working full-time, they spend fewer hours per day on the job than men.

These adjustments are just the tip of the wage-gap calculation iceberg. Even researchers who agree on the general principles of how you assess the wage gap disagree on the results due to the complexity of the data and associated human interactions. My head hurts just thinking about how one might analyze hundreds of millions of salaries across millions of businesses in hundreds of industries. In short, the problem is hard, really hard. It’s no wonder, then, that the average person is attracted to a simpler one-cause explanation for the gap.

Few people are ready to admit that they can’t understand something as seemingly obvious as salary differences between men and women. And so they glom on to something they can understand: discrimination. It’s an easy catch-all answer that seems to address so many problems. But truth is seldom easy to comprehend or accept.

[Image Credits: pexels.com]

February 14, 2018

Review: The Bell Curve

Race seems to touch everything today. Although the United States, with its Melting Pot philosophy, is the most ethnically and racially integrated nation on the planet, doubts remain about whether we have overcome the prejudices that allowed slavery to endure for the first seven decades of our sovereignty.

The election of Donald Trump, and the fear by some that he is a closet white supremacist, has put the issue of race front and center. But such concerns are by no means new. Consider the publication of The Bell Curve back in 1994, a book that, while only marginally about race, touched off a bitter debate over perceived insults based on skin color.

In the text, researchers Richard J. Herrnstein and Charles Murray looked at the role of intelligence in areas of social concern, such as poverty, illegitimacy, and crime. Their conclusion: IQ impacts such things, and is borne out by the data. For example, the average IQ of those who are incarcerated for all types of crimes is between 84 and 92, far below the overall level of 100 for the nation at large. The authors also claim that “low intelligence is a stronger precursor of poverty than low socioeconomic background.” This view implies that government poverty programs may fail to meet their goals if they don’t take intelligence into consideration. Low IQ is also correlated with higher unemployment, greater health issues, illegitimacy, short-term welfare (long-term is more complicated), single-parenthood, low birth weight, and lack of participation in civic actions like voting.

This core idea isn’t really controversial. Despite all of the movies that pit the super-villain against the latest incarnation of Sherlock Holmes, we all understand that criminals are not that smart. Poverty is more complex, but the connection between low intelligence and limited access to high-paying jobs should be obvious. Not that such trends are true of every person. There are plenty of geniuses who live in penury, and even more people with below-average intelligence who become business leaders or superstars. But when we zoom out and look at the overall American or global population, such trends become apparent.

The real controversy arose when the authors began to address race. (They aren’t the only ones receiving a harsh response to such investigations. Just a few days ago, a high school student in Sacramento examined IQ and race for his science fair project. Some Californians were not amused.) With all the hoopla that surrounded the book back in the mid-nineties, you would assume that every page was dripping with fascist calls for daily lynchings. But the authors really don’t mention race or ethnicity until nearly 300 pages into the work. And when they do address race-based variations in intelligence tests in Chapter 13, they start out by cautioning—practically groveling—that people shouldn’t read too much into the analysis.

Still, what they say about the races is shocking: “There are differences [in IQ] between races, and they are the rule, not the exception.” The authors are quick to point out that this variation applies only in aggregate and not to any specific individual within a racial group. There are plenty of high-IQ African-Americans, and even larger numbers of dull whites. “If you were an employer looking for intellectual talent,” the authors insist, “an IQ of 120 is an IQ of 120, whether the face is black or white, let alone whether the mean difference in ethnic groups were genetic or environmental.” They also stress that intelligence tests are made up of subtest components, and that a group that scores lower on an overall test might nonetheless score high in specific subtests. For example, East Asians (Chinese, Korean, and Japanese populations) score about three points higher than whites overall, and higher in the visuospacial subtest, but whites outperform them in verbal tests.

African-Americans, as a group, produce lower IQ scores than Caucasians, a result that nobody wanted to hear. The very idea that blacks might not be as smart as whites is anathema to the American ideal of equality of opportunity. But the authors actually do not push such a view. Instead, they list survey after survey showing that blacks in the United States, especially those with higher intelligence, do far better than the typical white in obtaining good jobs and incomes. “After taking IQ into account, blacks have a better record of earning college degrees than either whites or Latinos…. Blacks are overrepresented in almost every occupation, but most of all for the high-status occupations like medicine, engineering, and teaching.”

Test scores show a divergence between the races, but Murray and Herrnstein admit to having incomplete answers as to why. There are long explanations about the potential for poor testing methods that favor white responders, but the analysis rejects that possibility. (The examination of reaction speed versus movement speed in visual response tests is particularly interesting.) They do say that IQ has a large environmental component (between twenty and sixty percent of the influence, with twenty being more likely), and that blacks in American have raised their scores significantly since the passage of the Civil Rights Act. Nutrition could also play a part, since it is one of the few methods by which IQ scores can be influenced intentionally.

Although the discussion of race is interesting, if controversial, it’s not the core focus of The Bell Curve. Instead, the authors wrote the book over concerns that “cognitive stratification at the top of the American labor market” will cause larger societal problems. In the past, those of high and low intelligence mixed freely. Most Americans were farmers, and they lived in the same small rural towns, worshiped at the same churches, sent their kids to the same small schools, and shopped at the same stores. Intelligent kids were more likely to attend college, but only in small numbers. Most highly intelligent Americans before the twentieth century topped out with a high-school education, just like their lesser-skilled peers. Their higher brainpower often led to better incomes or social status, but it was always in the context of a mixed-intelligence community.

That mixture changed in the twentieth century, with the economic rise of the middle class after World War II, the expansion of communities into the suburbs, and improvements in transportation and communication. The intelligent still achieve greater financial success than their lower-IQ counterparts, but now they have the ability to separate themselves into enclaves. Smart people now live together, shop together, and educate their kids together, all far away from those of lesser intelligence. While the government has placed restrictions on using IQ tests in hiring, the authors point out that “laws cannot make intelligence unimportant.” Smart people will rise to the top, unless you use totalitarian means to stop them.

The authors also worry about future job prospects for those less intellectually endowed, especially as technology begins to replace more entry-level and routine jobs. “People in the bottom quartile of intelligence are becoming not just increasingly expendable in economic terms; they will sometime in the not-too-distant future become a net drag…. Unchecked, these trends will lead the U.S. toward something resembling a caste society.” Recent research into self-driving cars and AI-based services has exacerbated such fears.

Given the reality that some people are smarter than others, how do you organize a free society so that those with lesser thinking skills are able to keep up? The book offers several suggestions, most involving changes in governmental policies.

Stop dumbing down education, especially college education. “92% of federal funds that are for student assistance target those at the low end of intelligence. Gifted students get 0.1%.” While helping those in need is important, “in a universal education system, many students will not reach the level of education that most people view as basic,” and forcing everyone to the same supposedly life-enhancing level is misguided. The authors recommend redirecting some of the student support funds toward the intellectually gifted, in part to equip them to grapple with the changes happening in the nation. “Most gifted students are going to grow up segregated from the rest of society no matter what. They will then go to the elite colleges no matter what, move into successful careers no matter what, and eventually lead the institutions of this country no matter what. Therefore, the nation had better do its damnedest to make them as wise as it can.”

Welfare programs “that assist people should take IQ into account, so as not to misdirect the assistance.”

Simplify government by replacing complex criminal statutes with basic prohibitions, and reduce the regulatory demands for starting and running a business. “The same burden of complications that are only a nuisance to people who are smart are much more of a barrier to people who are not.”

Stop looking to the federal bureaucracy for solutions to every individual problem. Instead, a “wide range of social functions should be restored to the neighborhood when possible and otherwise to the municipality.”

This last point is especially relevant, since differences in intelligence matter most not in aggregate, but at the individual level. By concentrating on individual instead of group needs, those who are best able to offer support can join one-on-one with those who, through no fault of their own, are unable to comprehend a solution for their troubles.

Despite the controversial content that has garnered decades of negative press, the book is generally upbeat and hopeful for the future. “Now is the time to think hard about how a society in which a cognitive elite dominates and in which below-average cognitive ability is increasingly a handicap can also be a society that makes good on the fundamental promise of the American tradition: the opportunity for everyone, not just the lucky ones, to live a satisfying life.”

Instead of pretending that everyone is equally endowed intellectually, or that we can eradicate such differences, the authors encourage Americans to “once again to try living with inequality, as life is lived: understanding that each human being has strengths and weaknesses, qualities we admire and qualities we do not admire, competencies and incompetences, assets and debits; that the success of each human life is not measured externally but internally; that of all the rewards we can confer on each other, the most precious is a place as a valued fellow citizen.”

Use the following button to obtain a copy of the book, and become even more well-read.

January 30, 2018

Everyone Is Corruptible

This article is part of a series on “Optimal Conservatism,” an attempt to define and understand the conservative political mindset in America. Click here to read other articles in the series.

Conservatism, like all other political philosophies, deals with how people interact within a society. If you want to maintain peace and civility among millions or even billions of people, you have to understand some core things about those people. And for conservatives, one of the most important things to know is that people are corruptible.

All humans are a mix of altruism and selfishness, with some, like malevolent dictators, leaning toward the evil side of the morality spectrum, and most others, like the proverbial “little old lady,” tending toward the good.

No matter how pure a person may be, there is always the potential for bad behavior. Even when people try to do what’s right for themselves and for those they love, they may make choices that bring harm to others. Throw in incentives for greed and self-preservation, and most of us are ripe for corruption.

This corruption is closely tied to power and control, both over others and over ourselves. Consider the example of slavery. Masters beat their slaves as a demonstration of their control. But slavery in the American South was, at least in part, an admission that cotton farming before the advent of the cotton gin was a financially bad decision. The fear of financial ruin and starvation activated or augmented the temptation to succumb to corruption, in this case, the corruption of enslaving others.

Even for those of us who would never stoop to slavery, opportunities to give in to minor corruptions are all around. We all know this instinctively. None of us is surprised when we hear about a politician abusing power. And the recent revelations of sexual misconduct within Hollywood circles, while disturbing, are easy to believe. Most of us do not debase ourselves or others with that level of behavior, but we nonetheless understand that we all make selfish or hurtful choices.

For the conservative, this understanding of human frailty must be taken into account when organizing a society or its government. This is the main reason why the US Constitution separates governmental power into three, sometimes conflicting branches, and why the Bill of Rights declares that “the powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”

This dilution of power across multiple levels of government and, more broadly, to the citizenry is a recognition that power, if left in its concentrated form, will lead to corruption, because people are naturally corruptible. The only way to ensure that such corruption does not happen, or at least has a minimal impact, is to prevent the full level of power from being accessed by any individual, group, or cause.

There is another view, a utopian view, which is increasingly common in America today, especially among those on the political left. In this perspective, humans are a tabula rasa, a blank slate upon birth, and it is the influences of society that push people toward altruism or selfishness. If only we could craft a proper society, or provide appropriate education, or take away the unfair advantages that allow some to assert power over others, a time of peace and prosperity would reign.

Such a view is errant because it posits that mankind is not corruptible, but only temporarily corrupted. It believes that the core of humanity is good, and was only corrupted by external factors, factors that can be controlled by well-crafted systems and wise leaders. But there’s that word “control” again, which as we saw before, is a foundation of corruptibility.

Every attempt to reconstitute national power within the hands of enlightened leaders, or to make blanket calls for “bipartisan agreement” or “more efficient government” are anathema to the core principles of conservatives. Those on the right reject such utopian visions not because they are advocates of suffering, or oppose regulations, or want to be rich at the expense of the poor. Instead, it’s based on the understanding that the corruption of concentrated power is a far worse than the societal imperfections that make life difficult for some.

[Image Credits: Ollie Atkins, Official White House Photographer]

January 17, 2018

Optimal Conservatism – Introduction

The political philosophy known as conservatism has taken a beating in recent decades. Although those on the right enjoyed national popularity back in the 1980s, the years since Ronald Reagan left office have been marked by ideological trauma. Conservatives were once viewed as the family-friendly block of the political spectrum, even by those who eschewed their positions. But the typical self-identifying conservative today cowers under never-ending accusations of being greedy, hateful, and even fascistic.

The election of Donald Trump in 2016 didn’t do conservatives any favors. His quasi-conservative actions have muddied the right-wing waters, and made the most heartened advocates of Republican causes unsure as to what they should do. Victor Davis Hanson, writing in the conservative torchbearer National Review this week, speaks openly of this conflict, wherein “Never Trump Republicans still struggle to square the circle of quietly agreeing so far with most of his policies, as they loudly insist that his record is already nullified by its supposedly odious author.” The article is surprising not only because of its generally positive analysis of Trump’s first year—he calls Trump “perhaps more Reaganesque than Reagan himself”—but because it appears in the very magazine that dedicated an entire campaign-season issue to arguing “Against Trump.”

One difficulty with the conservative moniker is that it has been applied so loosely. George W. Bush was hardly a traditional conservative. His “No Child Left Behind” plan and his financial industry bailouts were borderline LBJ behavior, at least as understood by those Republicans still smarting from the Clinton-era ouster of Newt Gingrich. And yet, compared to liberal Al Gore, Bush was clearly the conservative candidate.

Another confusion comes from the standard pairing of conservative thought with the Republican Party. Like the Democratic Party, the GOP is a “big tent” organization, encompassing a range of thought that sometimes generates conflict within the organization. Many libertarians, while represented by an independent national body, still affiliate themselves with the Republicans for the pragmatics of winning elections. They must share space in the GOP with the moderates, the Rockefeller Republicans who are easily mistaken for centrist Democrats. While there are many conservatives who call themselves Republican, the groups are not the same, a fact easily exploited by those who abhor both.

Complicating the matter further is the ability to split one’s positions among the hemispheres of fiscal and social policy. Someone who aggressively pushes for low taxes and other conservative fiscal policies might still support progressive social causes, including gay marriage and environmental regulations. The reverse is also found in nature, where those holding very conservative social positions might be fine with the government invoking the fiscal power of John Maynard Keynes.

The true conservative position is not a clear point on the number line of political thought. Rather, it is a point on that line as viewed by someone in his fifties quickly losing the battle against presbyopia. You know there is a clear spot somewhere, yet all one sees is the blurry halo. But despite the lack of clarity, there is certainly value in establishing a vision of what conservatism entails, or should entail. Zealotry is always perilous, but reasonable people can still discuss and agree about how far the blurriness should extend from the ideal.

The current mishmash of so-called conservative thought has made it easy for those on the left to apply broad-brush straw-man arguments, condemning all conservatives for ideas held by a minority on the right, or by nobody at all. Most conservatives view themselves as compassionate, generally free of bias, willing to share with those in need, fascinated by other cultures, and open to reasonable compromise with those who disagree with them. Is it any surprise, then, that so many of them react with shock, and even anger, when they are labeled as bigots, corporatists, and Nazis?

Certainly those on the right have some blind spots concerning their own deficiencies. But progressives who view their conservative counterparts as evil are equally blind. Human beings, it seems, love discord. Yet some of the separation may come from a lack of clarity in how one defines conservatism.

In upcoming articles, we’ll examine key conservative ideas and positions, with the goal of identifying a healthy conservatism, one that I’ll call Optimal Conservatism. As we progress through these ideas, we’ll discover the core principles that best clarify what so many ordinary conservatives believe, principles that are worthy of admiration, not condemnation. This won’t be an easy road, since the target is jumping around. But if at the end we find understanding, the meandering trip will be well worth it.

[Image Credits: Wikipedia]

January 3, 2018

Chocolate is Safe from Killer Robots

A New Year’s Day headline in the UK’s Independent newspaper proclaimed, “Chocolate is on track to go extinct in 40 years.” That’s right cocoa-lovers, your ability to curl up with a tub of Rocky Road or a bar of 72% cacao with just a hint of chili pepper will be gone in two generations. It says so right in the article.

But wait, it doesn’t. Not only does the text by Erin Brodwin fail to list evidence for chocolate’s demise, the idea of extinction—or even the word—never appears in the article beyond the opening statement, which warns that “Cacao plants are slated to disappear by as early as 2050 thanks to warmer temperatures and dryer weather conditions.”

The bulk of the article is actually quite informative, discussing how the Mars candy company is investing $1 billion to help deal with the impact that climate change could have on current cacao crops. The company is working with University of California scientists to find genetic ways to strengthen the plant. Short of such interventions, the long-term solution, as the text points out, is to “push today’s chocolate-growing regions more than 1,000 feet uphill into mountainous terrain,” or grow the crops in other regions currently too cold for the plants to thrive.

How did the headline get the theme so wrong? Perhaps it was a mistake by an overworked editor. But given how common such eye-catching headlines are on social media sites, and even on primary-source sites like the Independent, their presence is more likely a response to how the public now consumes news.

These days, news exists not simply to inform, but to call readers to action, whether that action is justified or not. It’s clear from the article that chocolate is not in danger, even if the location of cacao croplands will need to change. But there’s no urgency in a story like that. Yet if the end of chocolate is drawing nigh, the time to act is now!

Consider another trend that will have a greater impact than the availability of chocolate: robots taking our jobs. A CNN article from last May warned that robots are coming to take cashier jobs, with the standard disclaimer that “these job losses will hit women particularly hard.”

Is the article correct? Will robots replace cashiers in upcoming years? Probably. But what the article fails to consider is the role that technology will play in bringing about new jobs to offset the losses, or the ingenuity of the human mind to invent new ways of being productive. The cacao article, or at least its headline, failed to take into account a change in situation, that croplands could be relocated. In the 1970s, a similar insistence that petroleum would soon be no more didn’t consider the roles of price and technology in finding new sources of fossil fuels.

Similarly, the hysteria over jobs lost to automation fails to consider how we’ve adjusted to dramatic advancements in technology before, and created entire new industries surrounding that technology. From mobile app development to electric car production, there are millions of new jobs that didn’t exist twenty years ago. And no matter how many robots you install in current job positions, there will be millions of new jobs two decades from now that we never dreamed of today.

By all means, enjoy a cup of cocoa before it disappears. But enjoy it in the knowledge that robots will not leave us all unemployed, but instead will assist us in enhancing of our beloved cacao crops.

December 5, 2017

New Book: Self-Evident

America’s Declaration of Independence is perhaps the most important statement on human freedom ever published by a government body. Despite having a laundry list of complaints against a ruling monarch as its foundation, the text still manages to lift the human spirit, with its eloquent claims that “all men are created equal,” and its insistence that all of us have an inherent right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

We laud Thomas Jefferson for penning the document’s flowing prose. While his talent for wordsmithing is obvious, most of the ideas contained in the Declaration did not spring anew from his mind. Instead, Jefferson relied on the powerful ideas evoked by the Enlightenment, on philosophical concepts from ancient Greek and Latin sources, and on what he called the “harmonizing sentiments of the day.”

There is much less harmonizing taking place in twenty-first century America. Despite being a gathering of “united” states, divisions abound, in part because we have forgotten the core messages written down in our founding document. Self-Evident, Tim Patrick’s new book on “America’s birth certificate,” returns the discussion to the foundational rights and Enlightenment beliefs of mankind’s place in history. It does this by examining the primary sources and key events that led up to the budding nation’s break with Great Britain, at that time the most powerful empire on the planet.

The lofty ideals embodied in the Declaration stem from centuries of deep political contemplation. And yet they are easy for anyone to grasp, in part because we all have been “endowed by our Creator” with the natural rights communicated in that work. In a world with instant access to endless entertainments and divisive arguments, Self-Evident will guide you back to the sources and ideas that centuries ago united a nation and spread freedom across the globe.

The book is part of the new Understand in One Afternoon series by Owani Press. In a world awash in nearly unlimited information, this series helps you discover the essentials of important subjects in a reasonable amount of time. Each book is designed to be consumed in about four hours—in one afternoon—and offers a core grounding in topics ranging from current events to technology, from philosophy to business.

Self-Evident is rolling out to online bookstores, in ebook and paperback formats, over the next few weeks. The Kindle, Apple iBooks, and Kobo editions are available now. Visit the publisher’s web site for the book to find the latest information on the book’s release, and on other upcoming books in the Understand in One Afternoon series.

November 15, 2017

Review of Nepal: Votes for Peace

If you close your eyes to the shock of the 24-hour news cycle, it turns out that life in America is pretty good. The grocery store shelves are filled with whatever food we desire. Stable roads allow our comfortable cars to get us from one place to another with few hazards. And while poverty exists, most of our poor are wealthy when compared to those found in many third-world nations.

With the safety and comfort we enjoy, it’s easy to take national stability for granted. Consider the experience of Nepal, as documented in the book Nepal: Votes for Peace, written by the former Chief Election Commissioner of Nepal Bhojraj Pokharel, and peace researcher Shrishti Rana. The book discusses the election of the Nepalese national Constituent Assembly that took place in April 2008, during Pokharel’s tenure.

Nepal in the early twenty-first century was a mess, what the authors sterilely identify as “post-conflict.” The restoration of multiparty democracy in 1990 gave way to the People’s War, pitting Maoist factions against the state army, with ordinary citizens caught in the crossfire. In June 2001, nine members of the royal family, including the king and queen, were assassinated, possibly by the crown prince, who committed suicide three days later. The new king (and brother of the late king) remained in power only five years before being forced to be resign in the face of further threats of civil war.

America was born in conflict, but the aggressor was an ocean away, and the people were generally unified in their cause. This book considers how to return a nation to stability in the midst of conflict between armed factions, masses of poor and disenfranchised minorities bitter at their treatment by the dominant society, interference by powerful neighboring countries, and no constitution or body of law to guide the process.

After providing a bit of historical background, most of the book deals with the minutiae of preparing for a nationwide election, including how to cope with nearly a year’s delay thanks to political infighting. There’s enough demographic analyses, quota lists, and overlapping timelines to keep a professional statistician happy for weeks. But the authors also discuss the inherent drama, such as how officials dealt with candidates killing each other.

The election eventually happened, with the Maoists, who had threatened to resume the war if they lost, taking first place. Perhaps that’s no surprise, but what was significant was that the aggressors put their guns away and made an attempt at parliamentary legislation. Unfortunately, by the book’s epilogue, the parties were unable to pass a new constitution, and the elected congress came to an end. In the years since publication, Nepal was able to transition into a constitutional democracy, and has had two relatively peaceful years under their new constitution.

In reading a book like this, you quickly realize that the left-right divide we experience in America is extremely tame. Where we sling mud, others sling live grenades. A hate crime in the United States often maxes out at fisticuffs and name-calling. In other countries, killing everyone in a neighborhood doesn’t even rise to the level of police reporting, assuming that the police weren’t in on the murders.

The book expresses some satisfaction that the election occurred at all, but one interesting discussion at the end deals with the failure of Nepal’s constitution. Although America crafted its own extremely terse constitution in under a year, it has led to one of the most stable countries on earth. It took seven years for Nepal to finally ratify its constitution, and the resulting document was over 200 pages long. The authors point to the difficulty of trying to “reconcile two distinct political philosophies—radical communist thoughts and liberal democratic values.” Despite the tremendous detail and care, the fear that the country will resume its internal conflicts is always real.

Nepal: Votes for Peace is not designed as a quaint afternoon read. The authors wrote the book primarily to assist other post-conflict countries with their own election preparations. But for comfortable Americans who fret and worry about the most minor of electoral infractions or political disagreements, reading a book like this can bring tremendous insight, and remind us, as Thomas Jefferson said, that “We are not to expect to be translated from despotism to liberty in a featherbed.”

Use the following button to obtain a copy of the book, and become even more well-read.

October 25, 2017

Healthcare is Not That Special

Perhaps you see things differently, but I like being healthy. When I get sick, sick enough to exhaust my own understanding of medical science, I’m glad that I can consult with a doctor or other healthcare provider, and (usually) get just the right solution to my problem. As a society, it’s important to have a stable system of medical care available to the general population.

I’m not the only one who thinks medicine is important. Two of my friends recently said to me that medical care is so important, it cannot be left up to mere economics transactions. This is especially true, they said, of any medical situation that touches on aspects of life and death. Instead of our current environment, they advocated a single-payer system, where the national government covers most or all fees for healthcare services and products. If you are dealing with terminal or chronic conditions, the thinking goes, you shouldn’t be asked to pay money for medical services.

Naturally, they are wrong, in part because of a core misunderstanding of economics. Economics, it turns out, is not about money, and economic transactions, though they typically involve the transfer of money, are not “economics” just because money is involved.

Economics is a science that studies human behavior; comments by economists on physical elements (widgets and cash) serve only to help clarify the primary behavioral subject matter. The early twentieth century economist Lionel Robbins perhaps said it best when he defined economics as “a science which studies human behaviour as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses.” Still-living economist Thomas Sowell simplified this a bit, calling economics a study of the “various way of allocating scarce resources which have alternative uses.”

If you read through those definitions, you won’t find words like “finance” or “money” or “cash.” When we discuss economics in public, the conversation often focuses on money, in part because the mathematical nature of money lends itself easily to discussions of an economic nature. That, and our native love of money. But economics is not about money, any more than it is about eating a meal, or telling a joke, or going on a vacation, or choosing a shirt from your closet. All of those are economic actions, but none of them are more economic than the others.

Let’s say that you have been asked to go to a wedding, and you need to choose from among the two neckties in your closet: one red, and one blue. This choice is an exercise in the allocation of scarce resources which have alternative uses. The scarce resource, in this case, is your neck. You have only one neck you can take to the wedding, and at this moment, there are multiple demands—the two ties—competing for that scarce resource. If you take time to ponder a new tie purchase just for this event, the demands go up even more without a comparable increase in supply.

How do you determine which tie will go on your neck? You might ask your wife, or try to match it to whatever socks you will wear, or try to switch ties halfway through the ceremony, or even close your eyes and grab one at random. Whatever method you use, that method is economic, because it concerns how a human (you) dealt with a scarce resource (your neck) that needed to be allocated (plied with a necktie).

Of course, choosing a tie is rarely as important as a discussion about some illness with your doctor. But in terms of economics, it is no different. Consider a true medical emergency situation, a war-time hospital setting, as popularized in the TV show M*A*S*H.

Imagine that a mobile army surgical hospital has five doctors, each of whom can perform a life-saving operation in thirty minutes. At a moment of relative calm, twenty wounded suddenly arrive at the camp. All of them have life-threatening injuries, and each will die within one hour without an operation.

Since there is time to save only ten of the twenty soldiers (five doctors at two operations each per hour), how do you decide which of the twenty wounded will receive medical care? Of course, the team will attempt to render as much care as they can, but even if extraordinary attempts are made to extend the life of each soldier, the fact is that there is a scarce resource (the doctors), and that more people (the wounded) are demanding access to that resource than can be accommodated.

No money is changing hands in this situation; the government truly is paying the entire medical bill for each patient. And yet, economics is still the driving factor in determining who gets care. In a triage situation, typically those most likely to survive will be given priority. But what if one of the wounded is the nephew of President Truman? What if one is a young and brilliant scientists who was just days away from curing cancer before he was drafted into the war? What if one of the injured slips a nurse $200 to be moved to the head of the line?

Whatever method is used, even if that method is considered immoral by a society, the behavior supporting that decision-making process is economic, money or no money. The decision to bring one patient in for surgery is an economic choice, as is the general decision trends employed over the course of the long war.

My friends insist that a single-payer system is better because it removes economics from the picture. But as we see in the army hospital example, economics never exits the decision process. It’s nice to think that medical care free of the burden of payment will somehow magically be better than what we have now. But even when nobody sees a dime change hands, economics is still happening because a limited supply of medical practitioners is offering services to a certain level of people demanding healthcare.

In this way, medical care is identical to restaurants, where a limited supply of cooks and servers must allocate themselves in order to meet the hunger needs of everyone going out to eat. And yet we don’t demand a single-payer system for something as important as eating. Well, Americans don’t, but other counties have tried it under the guise of communism, and the overall result was food shortages, persistent hunger, and an overall lack of goods. But at least they didn’t have to stress over which necktie to wear.

[Image Credits: CBS via wikia.com]

October 3, 2017

That Time I Agreed with Bernie Sanders

Last week, I found myself in complete agreement with Senator Bernie Sanders. As a political conservative, it left me with a sense of unease and disquiet. And yet, I couldn’t deny that what he said was correct and appropriate. His quasi-disturbing statement came in the form of a tweet on September 22, 2017:

This is a disgrace and a disservice to everyone who has worked to address sexual violence. Congress must act to undo this terrible decision.

— Bernie Sanders (@SenSanders)

Sanders was referring to an announcement by Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, reversing a set of policies instituted by that same department during the Obama administration. To understand what Bernie Sanders really said, and why it mattered, we need to look back in history, to the days of Flower Power.

In 1972, the Congress passed the Education Amendments of 1972, a set of legal enhancements to the Higher Education Act of 1965. One portion of the 1972 updates, known today as Title IX, attempted to distribute educational resources equitably between male and female students. While most of the law’s text included standard legal mumbo jumbo and constituent-specific exceptions, the core verbiage of the law was surprisingly straightforward:

“No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

That statement seems fairly clear. But you should never underestimate the power of a government agency to transform a good idea into a 5,000-page experiment in micromanagement. Since its creation during the Carter era, the Department of Education has tweaked the implementation of the law to meet the varying expectations of each presidential administration, and the American public.

Fast forward to 2011, when Obama’s Education Secretary, Arne Duncan, issued a set of guidelines for schools attempting to comprehend the basic 1972 law. Known as the “Dear Colleague” letter, the missive and its accompanying Q&A documentation provided guidance for colleges dealing with sexual misconduct on campus. As you follow the controversy, keep in mind that the letter was written by and issued from the Department of Education. While the content certainly reflected the views of President Obama, the content itself was sourced from bureaucrats from within that department.

Betsy DeVos, the current Secretary of Education, does not agree with some elements of that 2011 guidance. And so she directed the Department to issue revised guidelines, currently classified as interim, that make adjustments to the Obama-era instructions. Once again, this revised content was written by bureaucrats within the Department of Education, just as the 2011 content had been.

Therein lies the problem. Because the instructions issue by the Obama administration were little more than suggested interpretations of a rather broad statement from a 1972 law, there was nothing to prevent a later administration from sending out new guidelines that were equally interpretative. While you might disagree with one or the other of those interpretations, the fact that decision makers within the Department of Education found those interpretations within the underlying legal text was sufficient for them (in their minds) to issue written clarifications of that basic law.

Former Secretary Duncan had a different viewpoint concerning the law than does Secretary DeVos. The Department back in 2011 said one set of guidelines was the right interpretation; that same department from today sees another set as correct. Who’s to say which understanding is right?

I am. And so is Bernie Sanders. And you, too. We get to say what the correct understanding is, through laws passed by our representatives. The problem with the instructions issued by the Department of Education is not (primarily) that they said one thing in 2011, and something else in 2017. Rather, the issue is that the guidelines for both of those years were nothing more than guesses about what Congress wanted to set down as law back in 1972. The 2011 Dear Colleague letter says that “sexual harassment of students, including sexual violence, interferes with students’ right to receive an education free from discrimination.” Even if this is true—and the flexibility with which the document employs the term “discrimination” makes it difficult to prove—the expression of that interpretation through an agency guideline leaves it open to revocation by subsequent administrations.

In short, guidelines are not law. Law is law, but governmental agency guidelines are temporary interpretations of the underlying laws, interpretations that might vary with society. If you want a law, you need to pass a law. That is the core of Bernie Sanders’ statement, though I doubt that was his focus. And yet, he managed to state correctly that it is the job of our elected legislators, and not a group of civil rights bureaucrats in the Executive Branch, to issue laws.

A lot of Americans today are confused about this fact. It was just a few weeks ago that the entire nation had a fit over changes to the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). President Obama established that immigration policy back in 2012, after the Congress failed to pass the DREAM Act, which would have codified similar policies in law. In the absence of such legislation, Obama chose to implement the core intent of the law through selective enforcement and policy interpretations of existing immigration laws. Even through the American people (through their elected representatives) had not authorized such a law, the sitting president decided to implement a law-like policy. But DACA was not true law. As with the Title IX guidelines, these policies were little more than administration-specific interpretations of laws. That made them ripe for alteration by future administrations.

While a lot of people were upset at Donald Trump for reversing Obama-era policies, the revised guidelines issued under his name were just as authoritative as those produced under Obama. By which I mean that they weren’t really that authoritative at all, since they were not law. And they will be just as easy to reverse by the next president.

The Dear Colleague letter and the DACA policy are indications of laziness and impatience on the part of the Executive Branch. Laws require congressional action. If an administration, Republican or Democratic, isn’t happy with a Congress that failed to pass its hoped-for legislation, that still doesn’t give it the right to craft a policy and treat it as law. If you want something to have the force of law, you need to make it a law. Otherwise, you’re just putting your hopes on unenforceable promises.

[Image Credits: Gage Skidmore]

September 13, 2017

We are All Confused about Race

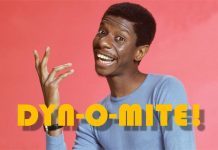

I grew up after passage of the Civil Rights Act, in an era when (we thought) the immoral behavior of the Jim Crow era had been pushed aside. Good Times and The Jeffersons were popular sitcoms on TV. I was too young to understand the nuanced messages on race. I just thought it was funny when Jimmie Walker said, “Dyn-o-mite!”

My parents never taught me to be racist. For a few years, our next-door neighbors were black, to use the terminology of that era. I wasn’t told that I should treat them any differently than our other neighbors, or that they were different at all. To me, they were just neighbors. They didn’t have any kids, and since I was still a youth, I didn’t interact with them much. But if there had been kids my age in that family, I would have hung out with them, and nobody would have made a big ideal out of it.

This nonchalant attitude concerning race followed me into adulthood. Many of my friends at college were minorities, not because I sought them out, but because I had some minority friends, and they introduced me to their friends, and so on. I married a minority, and more than that, an immigrant. Because of my marriage situation, most of my adult church life has been spent in non-white congregations, ones where less than ten percent of the church body looked like me. When I used to run my own company and needed to hire workers, I ended up hiring more minorities than whites, not because I was prejudiced, but because the slate of qualified candidates that came my way just happened to be of that mix.

This mini-biography appears here not to impress you with my racial blindness, but to make it clear that in my life, as with so many others my age in America, race was never a big deal. I knew about racial differences, of course, and I was not ignorant of America’s past racial problems. But in my own life, and among my own friends and colleagues, race was just never a thing.

But it seems that I was deceiving myself. If media reports and memes on Facebook are to be believed, I am a terrible racist, and the horrors of my white privilege are surpassed only by my indifference to the plight of non-whites.

I have a friend, an African-American woman in her early thirties, who works for a non-profit organization that advances the cause of minorities in America. Some would deride her as a “social justice warrior,” but she is confident enough in her role to own that name as a badge of honor. We attended the same church—a mostly non-white church—and chatted from time to time. Of course, we meandered into the topic of race, where she proceeded to inveigh against the benefits of my white privilege. When I balked at the suggestion, and regaled her with a bit of my bias-free history, she threw Martin Luther King, Jr., in my face: “History will have to record that the greatest tragedy of this period of social transition was not the strident clamor of the bad people, but the appalling silence of the good people.”

Now, that confused me. I didn’t understand how living a life where I treated minorities with the exact same respect and concern as I did whites qualified as “appalling silence.” I didn’t work full-time for a social justice organization like she did. But is such employment now the minimum standard that the champions of civil rights expect from the white majority?

The big race-related thing I remember from my youth was King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. We listened to it regularly in school, memorized some of the more impassioned portions by osmosis, and to the extent possible, we lived it out. The highlight of the speech, as it was imparted to me and my fellow students, was King’s vision for his kids: “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” While nobody told us outright to do this, the idea that we should stop obsessing on skin color and start focusing on character was clear. And so we did, at least among the people in my sphere of acquaintance.

If I take King’s words seriously, the color of someone’s skin should be of no more importance than the color of their eyes, or of their hair, or how much hair they have, or the situation they grew up in, or the amount of money in their bank account. The key, I was led to believe, is character. I have met people of varying races who possessed very poor characters, and it would pain me to deal with them for any length of time. But I have also met myriad people of all colors who possess some of the greatest characters. It is my honor to spend time with them.

But that’s not the America we live in today, at least according to my social justice acquaintance. My friendship with minorities, my history of good relations with those of all backgrounds, my indifference to skin color; these are all a sham, I’m told, and so typical of those benefiting from white privilege. Instead, the lesson for today is that I must keep skin color first and foremost in my mind, and that as a white, it is in my best interest to be reminded regularly of this nation’s history of abuse against minorities. Treating people in a race-neutral manner is now an affront. Commenting casually on the color of someone’s eyes is still permitted in our society. Try complementing someone on their skin tone and see what happens.

For now, I will live my life as if Dr. King’s plea to treat his family based on character is the way to go, and that I should not take skin color into account. But so many today are telling me something different. Either King was right when he lifted character above race, or he was wrong. I think he was right, but sometimes, one can only dream.

[Image Credits: Match Game]