Tim Patrick's Blog, page 9

August 23, 2017

Why Healthcare Costs So Much – Part 6

(This is Part 6 in a continuing series on the cost of healthcare in the United States. Click here to start with Part 1, or click here for the previous installment.)

In the previous article in this series on healthcare costs, we examined the role that medical insurance plays in increasing demand for medical services, since the ready money made available through insurance chases a limited supply of doctors in a way that brings inflation to medical costs. In this, the last entry in the series, we will look at some things that impact the supply side of the supply-demand equation. This is just as important as the demand aspect, since all other things being equal, cost increases can come about through increases in demand, decreases in supply, or a combination of both.

As you might expect, there are many things that can affect the supply of physicians, medicines, and medical devices within the healthcare system. Consider the role of medical licensing of physicians and other providers by each state. To obtain a license in California, for example, “applicants must have received all of their medical school education from and graduated from a medical school recognized or approved by the Medical Board of California or must meet the requirements of Business and Professions Code section 2135.7.” They must also pass the United States Medical Licensing Exam (or its equivalent), and submit proof of passage to the state. I personally think these licensing requirements for doctors are great, but if such rules did not exist, a lot more people might consider opening their own “doctor” offices. The licensing requirements acts to reduce the supply of physicians, although for a public safety rationale.

The price of malpractice insurance premiums, the high cost of a medical education, and the rigors of residency and internship also work to limit the supply of doctors, since some candidates who might have succeeded in the medical profession may decide that these obstacles are not worth the eventual benefits.

One issue that must be addressed when crafting legislation that impacts healthcare, especially one that claims to lower the cost of healthcare, is how to increase the supply of healthcare providers, since their service fees are a large part of what is included in “medical costs.” If the new law encourages more people to enter the medical profession, makes it easier for those who seek that career path to succeed, or provides incentives for existing providers to remain active, it will help to lower medical costs long term, since an increase in the supply of medical providers tends to lower costs, assuming that supply exceeds demand for services.

There were a few regulatory items in the Affordable Care Act that could have provided incentives for new and existing physicians, especially those engaged in general practice. Beginning in 2013, states were required to pay out higher fees under Medicaid to providers of family medicine, general internal medicine or pediatric medicine services. While those adjustments aren’t big in the grand scheme of things, they might keep someone in the general provider pool who was considering entering a more lucrative specialty. At the state level, laws have been passed that expand opportunities for physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and medical technicians, providing ways to enlarge the total number of providers even if the total number of general practitioners does not increase.

Unfortunately, newer federal regulations like those in the ACA do little to encourage growth in the pool of healthcare providers. Instead, those laws have tended to increase the cost and regulatory obligations that physicians must meet in order to continue practicing. There are also new requirements for non-profit hospitals, and large penalties for those who fail to meet the regulatory demands. While the goal of such regulations may be to improve the level of healthcare in the country, they nonetheless have a limiting effect on the overall number of providers.

As long as the government imposes rules that limit the total supply of medical goods and services, no amount of jiggering of the insurance system will bring down healthcare costs. The only way to lower costs, no matter who is paying those costs, is to lower demand, increase supply, or both. When politicians promise to make something cheaper, but do so in a way that ignores the underlying rules of supply and demand, it imposes a type of illness on the nation that doctors and prescriptions cannot cure.

[Image Credits: public domain/US Navy]

August 1, 2017

Why Healthcare Costs So Much – Part 5

(This is Part 4 in a continuing series on the cost of healthcare in the United States. Click here to start with Part 1, or click here for the previous installment.)

The Affordable Care Act (ACA), passed in March 2010, had three major goals: (1) make affordable health insurance available to more people; (2) expand Medicaid to cover more low-income adults; and (3) lower the cost of healthcare in general. There was some success in the second goal, that of expanding Medicaid to more people, at least in the states that opted to participate in the expansion program. But the act was not as successful when it came to the other two goals.

More people did enroll in healthcare plans under the ACA, but the plans themselves have dramatically increased in price since the law took effect. And while some insured benefited from tax rebates to pay for the plans, that doesn’t change the underlying fact that the plans themselves are significantly more expensive than before. As for reducing overall medical costs: while the double-digit annual percentage increases for care in the US from decades ago is no more, the historically low annual price increases that were the norm leading up to ACA implementation have jumped higher since 2013. Even if costs were to rise on par with inflation, the current costs of physician services and medical goods are already higher than most people are comfortable paying.

So what happened? Why were the cost-related promises of the Affordable Care Act not realized, even with increased access to private and government-supported healthcare plans? It turns out that a big reason for price increases, not just now but over the last several decades, has been the very insurance that the ACA leaned on to make care affordable.

As we discovered in last week’s article, price increases on goods and services are driven by the interaction between the available supply of such products and services, and the demand for them. When there is ample supply to meet demand, prices remain low. But when demand increases beyond what can be supplied, prices go up.

Consider annual passes to Disneyland as an example. The price of the top-tier pass more than tripled in a decade, rising from $329 per person in 2004, up to a whopping $1,049 per pass holder in 2015. While Disneyland annual passes are not a perfect example, due to their pseudo-monopolistic traits, the price increases are nonetheless a product of supply and demand. Disneyland originally developed the passes as a way to increase attendance at the park during non-peak times. That is, the supply of spaces in the park was high, while demand was low, leading to a reduced cost for consumers. But with over a million pass holders now competing for entry even on popular weekends, Disneyland needed to find a way to limit overcrowding, and solve its low-supply, high-demand quandary. The result was an increase in prices, because prices always increase when demand exceeds supply.

This is the nature of inflation, what my political science professor in college summarized as, “Too many dollars chasing too few goods.” This phenomenon is even truer for national industries like healthcare, since the impacts of competition on the market are more pronounced. In the case of medical services, the supply comes in the form available service time slots that all physicians in the United States have at any given time. The demand is the number of appointments made by consumers who are injured or infirm. If people are staying relatively healthy and there is not much demand for medical services, prices remain constant or even go down. But if there is an increased demand for medical care, beyond the point at which the current supply of doctors can service, the way that providers prevent overcrowding is through price increases. It might seem unfair, but it’s how capitalist economy works. (It works that way under Communism as well, but the effects are absorbed into the economy through rationing and a reduced standard of living.)

As prices increase, some consumers who can’t afford the higher charges might seek alternatives, such as by using home remedies, or by finding nurses and physician assistants that charge less. This reduces demand on the primary market, keeping prices stable. But what if there was a way for all consumers to pay for the increased costs of medical care, no matter how high those costs went? That is what comprehensive medical insurance plans provide.

Normally, insurance is designed to cover high-price, low-frequency events, such as a car crash, or an unexpected early death. By pooling resources together, a group of insured are able to deal with such expensive events when they occur, but with a lower individual cost, thanks to the statistical unlikelihood of the event happening to many people in the pool.

But comprehensive healthcare coverage, the kind you currently have, is not that kind of insurance. Instead of paying for expensive but uncommon events, most policies cover routine expenses, after an initial deductible. This changes the core nature of that insurance, from something that is invoked on rare occasions, to something that is invoked on nearly every occasion, and with government-mandated payouts.

By providing ordinary consumers with a large pool of money dedicated for medical costs, minor increases in medical charges by physicians in response to a higher demand for services will no longer be met by lowered demand, because people now have the funds, through insurance, to pay the increases. But doctors still need to prevent overcrowding. Therefore, they increase costs up to a level beyond which insurance policies are willing to pay for routine services. Only then will demand quell enough to bring the supply-demand ratio back into balance.

Comprehensive medical insurance leads to increased costs, because it enables increased demand (in the form of insurance dollars) to chase after a limited supply of medical services. By requiring that every American have such coverage, the demand for services increases even more, prompting even higher prices. Of course, there are now calls to restrict the maximum price that providers can charge for services, and physician reimbursements from Medicare and Medicaid have gone down for just this reason. Unfortunately, as we will see in a future installment, this behavior only serves to reduce supply, and yet again increase prices.

[Image Credits: nyphotographic.com / Nick Youngson]

July 25, 2017

Why Healthcare Costs So Much – Part 4

(This is Part 4 in a continuing series on the cost of healthcare in the United States. Click here to start with Part 1, or click here for the previous installment.)

Healthcare is all about economics. That’s not a pleasant idea for some, especially those who strive to eliminate the influence of money from important life decisions. But while money often changes hands when a doctor cares for a patient, the fact that healthcare is all about economics is not a statement that concerns the dollars involved.

To really understand the cause of increased healthcare costs, you must—not should, but must—have a grasp of basic economics. And for English speakers, there is no better way to understand the core nature of economic systems than by reading Basic Economics, by noted economist Thomas Sowell. Now in its fifth edition, the thick tome (900+ pages!) communicates the essential facts that everyone needs to know about economics, without all the formulae, calculations, and Federal Reserve executives that tend to make economic discussions boring.

Sowell’s main thesis is surprisingly short: “Economics is the study of the use of scarce resources that have alternative uses.” Our earth has provided its seven billion inhabitants with abundant resources, and yet even those seemingly unlimited natural assets are scarce, not because they will run out at any minute, but because the finite supply of those resources at any given moment is at the mercy of competing demands for those resources.

As an example, Sowell discusses the uses of milk. Cows produce a finite amount of milk each day, and once processed, that resource is available for use in yogurt, ice cream, or to sell directly to consumers in bottle form. If cows produce a quantity of milk that fully meets the demands of yogurt, ice cream, and plain milk sellers, then everyone will be happy, getting their milk needs met for a price that is probably just a bit above what it takes to produce and deliver raw milk. But if the bovine version of the common cold puts a third of the population of dairy cows out of commission for a few days, things start to get interesting. How do you decide where the limited supply of milk goes? Should yogurt producers get first crack at it, or is ice cream a more important use? What if the various producers of milk-based products refuse to reduce their demands for the level of milk they have come to expect?

The answer to these questions is, of course, economics. When the supply of milk drops below what is demanded by the marketplace, its identity as a scarce resource with alternative uses becomes obvious. In a capitalist system, the lower supply of milk will lead to a bidding process by those who demand milk, resulting in an increase in the price of each unit of milk, not just for those who win the auction, but for everyone. The reverse is also true: when the desire for ice cream goes down in the winter, lowered demand for raw milk by ice cream producers leads to a lowering of the unit price of milk, because the oversupply of that resource makes it less desirable, and therefore less valuable, to milk-centric businesses. It is still a scarce resource that has alternative uses, but the lower demand for those uses has an impact on the economics of the various parties involved.

The rules surrounding scarcity, supply, and demand are true even when capitalism is not the system used to resolve conflicting demands. If there is a limited supply of milk, no mandates by a central communist government will completely fulfill the production demands of the milk, yogurt, and ice cream factories. Either the supply of milk will need to be increased, or the demands for milk products will need to be reduced. That milk is provided at a nominal, fixed charge to consumers does not alter the underlying nature of supply and demand, nor the economics used to understand the situation. When milk products are sold at a government-mandated cost, the normal function of currency as an indication of the current price is unable to operate. Therefore, some other process must determine who will win the bidding process for scarce resources, and without the benefit of price indicators, that process typically appears in the form of rationing of goods and services. Even if consumers received milk products for free—that is, even if the government acted as a “single payer” for milk, ice cream, and yogurt—it would not change the economic reality of scare resources having alternative uses.

As it goes with milk, so it goes with healthcare. The resource in this case is not dairy products, but the amount of medicine and the number of doctors, nurses, and other medical providers available to meet the healthcare demands of the general population. The application of economics to this industry is independent of the money paid for prescriptions and services. Sowell describes this very case in the introduction to his book: “When a military medical team arrives on a battlefield where soldiers have a variety of wounds, they are confronted with the classic economic problem of allocated scarce resources which have alternative uses. Almost never are there enough doctors, nurses, or paramedics to go around, nor enough medications. Some of the wounded are near death and have little chance of being saved, while others have a fighting chance if they get immediate care, and still others are only slightly wounded and will probably recover whether they get immediate attention or not…. It is an economic problem, though not a dime changes hands.”

In a capitalist system, when the relationship between the supply of healthcare services and the demand for those services changes, the price of those services adjusts to indicate the current cost at which the scarce resource of such services is being provided. If the demand for such services increases without a comparable increase in doctors, the amount charged by doctors will rise. Doctors could keep their prices the same and arbitrarily decide which patients they will see and which ones they won’t. (This currently happens when a doctor’s office closes the practice to all new patients, or to patients using certain insurance plans.) But it is more common to use prices as the tool for determining how to prevent a rush of patients from overwhelming the stable of doctors. If demand increases consistently, and the amount charged for services goes up accordingly, more people may decide to enter the lucrative medical profession, thereby increasing supply and, over time, reducing costs.

This works fine, until something comes along that perturbs the level of supply and demand. As we will see in upcoming articles, there are several factors at work, some mandated by government, that both restrict the supply of doctors and medicines and simultaneously increase the demand for those services and goods. Decreased supply and increased demand: that combination leads to higher milk prices in the dairy industry, and it likewise leads to higher prices in the healthcare industry. In the next article, we’ll examine a major impact on the supply side of that relationship, the role of medical insurance in driving up medical costs.

[Image Credits: PublicDomainPictures.net/George Hodan]

July 18, 2017

America’s Love Affair with Corporate Welfare

If you ask Americans their opinions about corporate welfare, the responses are universally negative. Those on the right hate it because it is a blatant example of a bloated federal government wasting taxpayer dollars. For those on the left, the focus is on the evil corporations who have their greed and egos emboldened by government funds that could be better used for education. The Occupy Wall Street movement from back in 2011, a left-leaning event that sought to expose the power and influence of corporations, included public denunciations of corporate tax breaks, subsidies, and other public sponsorships of business. On the right, organizations that have no love for the Occupy protesters are nonetheless holding hands with them on the topic of corporate welfare, with national think tanks like The Heritage Foundation and The Cato Institute issuing policy papers on the evils of that government practice.

Despite the clamor against corporate welfare, we love it. We demand it in various manifestations from all levels of government, and we feel a certain excitement when our preferred business support program plays out. The popularity of such programs is partly a reflection of how much Americans want them to exist. One online subsidy tracking tool documents more than half a million corporate welfare events, including direct grants, loan guarantees, tax breaks, and reimbursements for expenses. And while some of these incidents are certainly money grabs by greedy corporations who care for nothing more than the bottom line, many of these subsidies are tied to programs and actions applauded by even the staunchest Occupy protester.

Don’t believe me? Consider some of the ways that government funds or perks benefit corporations, and see if any of them bring a smile to your face.

Large municipalities build sports stadiums and event arenas, ostensibly to bring in tax revenue through ticket sales and concession sales. But these capital projects typically benefit one corporate entity—a sports team—more than all others, an entity that will sometimes bully cities with the threat of departure as a way of getting the project started.

Enterprise zones and similar programs designed to encourage job creation in impoverished or disaster-impacted areas represent one of the most common uses of corporate welfare. If a company promises to move into an economically needy region, governments at various jurisdiction levels will provide tax breaks, loan guarantees, and even direct payments, all for the purpose of lowering the unemployment rate in those areas and encouraging natural economic growth.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) is the government entity that guarantees the funds your personal checking and savings account in the event of a bank failure. While this is not a direct subsidy to a business, it has a parallel impact, that of allowing a corporation (the bank) to reduce its own insurance expenses and employ riskier though lower-cost money management processes, knowing that the federal government will be there to clean up the mess should anything go wrong.

Buying a new refrigerator? Make sure to get one that is energy efficient so that you can get a rebate check from your local utility or government. And don’t forget that this is yet another form of corporate welfare. Such individual rebates lower the perceived price of major appliances in the eyes of the consumer, allowing manufacturers to sell more, higher-priced units than they normally would, all promoted by government-sponsored energy efficiency programs. This doesn’t even include the $16 billion in direct subsidies and tax breaks (2013 numbers) that energy companies and similar corporations receive for offering “green” energy and other improvements in energy technologies.

“That’s a very nice home you have there, Mr. Jones,” says your state senator. “It would be a shame if anything were to happen to it.” Good thing they passed a law mandating that every dwelling have a specific number of smoke alarms and carbon monoxide detectors. That such laws provide a direct benefit to specific device manufacturers and industries is often overlooked in the wake of the elation over safer homes and protected children.

Government licensing of certain job categories—doctors, electricians, cosmetologists, and so on—provides an indirect support for companies hiring in those categories, since the specific regulations enabling people to work those jobs also restrict other types of jobs and business that might provide similar, though not licensable, products and services. If you come up with a new hair-cutting technique that does not fall under the umbrella of the licensing requirements enacted in many states, you won’t be setting up shop, or providing a competitive threat to existing beauty shops and salons. This reduction in potential competition increases profits for licensed businesses.

Student loans provide those at the lower end of the economic scale—and, it turns out, those at the higher end as well—with extra money to use on a college education. This enables lenders to provide government-guaranteed products to a population normally considered too risky for standard loans, thereby expanding the bottom line of those banks without all of the worry over defaults. But it also allows public and private educational institutions to increase their tuition rates, knowing that higher fees will be met with the increased resources made available to students through these loans.

Government grants for medical and engineering research reduce the financial burden on pharmaceutical and other biotech companies, allowing them to have the government in effect contribute to a part of their research and development budgets.

Although it is more controversial than other examples in this list, government support for the family planning services offered by providers like Planned Parenthood represents one of the clearest examples of subsidies that directly benefit a corporation or industry.

The examples above go beyond the traditional understanding of corporate welfare. And yet, they all have a similar impact on specific companies or sectors of the economy. Some of these programs are viewed positively by a large segment of the American population. Who doesn’t like the FDIC-supplied insurance on their bank accounts? It has given Americans a higher level of confidence in the banking system. Yet it, along with other programs that supported the “too big to fail” mentality, helped construct the 2008 recession.

Some corporate welfare programs are just plain awful, existing primarily to enrich some politician’s favorite business or industry. But others are a mix of despised and welcomed impacts, and it’s hard to call for their immediate elimination. You might hate corporate welfare programs, and that’s great. But don’t forget to examine your own beloved government programs to see if you might be part of the reason corporate welfare exists.

[Image Credits: flickr/Women’s eNews]

July 11, 2017

Why Healthcare Costs So Much – Part 3

(This is Part 3 in a continuing series on the cost of healthcare in the United States. Click here to start with Part 1, or click here for the previous installment.)

Today was the day this series was going to start delving into the raw economics of healthcare costs. But a comment in response to last week’s posting made me realize that there is one more common complaint we need to address before moving on to the core analysis. The issue is executive pay, specifically the salaries given to the CEOs of corporations that provide healthcare products and services.

Part 2 discussed the impact that the rich have on healthcare costs, and how most of the concerns are emotional and not based in economic reality. One reader objected to this idea by posting a list of salaries for twenty CEOs of healthcare corporations. I don’t know the source or accuracy of the data, and some people on the list no longer lead these companies. But in general, the list seemed fairly accurate as far as Fortune 500-level CEO compensation goes. The highest earner on the list was Leonard Schleifer, CEO of Regeneron, earning $41.97 million in annual salary, stock, and benefits to manage the New York biotechnology company. At the bottom of the list was Robert Bradway, head of Amgen, who earns a comparatively paltry $13.96 million.

Those are big numbers, to be sure, much more then I will ever expect to see in my annual compensation package. We live in the era where the “One Percent” are evil, and where the disparity between wealthy CEOs and their most underpaid employees is presented as proof of the downfall of the United States. It is reasonable to be concerned when the rich and powerful start throwing their weight around. But for our purposes, the question is not whether such salaries are fair, but whether they have any meaningful impact on healthcare costs.

I looked into the salary for one of these corporate executives, Alex Gorsky, CEO and Chairman of the Board for Johnson & Johnson, listed with a compensation amount of $25 million. I selected Gorsky because he falls more or less in the middle of the list I received, and is still active in the leadership of that corporation. I’m not sure what year the claimed amount is for. One source says that his income for 2016 was about $21.2 million, of which $1.6 million was his base salary, $4.6 million was a bonus, and the rest (outside of basic corporate benefits) came in the form of stock and stock options. While this total is lower than the amount mentioned in the list, let’s still stick with the $25 million figure, since it’s even bigger and scarier than $21.2 million.

I looked through the 2015 Annual Report for Johnson & Johnson to better understand what impact this level of compensation has on the total business. But I ran into a problem right away: I don’t know how to read an annual report. But I was able to glean two key numbers from the document. The first is the total worldwide income for Johnson & Johnson during 2015, which comes to $70.074 billion. The second interesting number is 127,100, which is the total number of corporate employees during that same year.

Employees come in a wide range of salary levels. You would expect a medical company to have lots of highly paid engineering and research types, with comfortable six-figure salaries. But there are also janitors and cafeteria workers with entry-level salaries. To make our calculations easier, we’ll use median US income, which in 2015 was $56,516. (This is household income, not individual salary. While this number is perhaps a bit high, it isn’t different enough to impact the final conclusions determined below.)

Beyond base salaries, employers pay out 6.2 percent in Social Security taxes for each employee (in addition to what the employee pays), 1.45 percent for Medicare, a few hundred dollars in unemployment taxes, 1.85 percent for administrative overhead and other expenses, and additional payouts for benefits like healthcare plans. The exact amount varies by location and job, but one source advised adding 20 percent to the base pay to determine the additional per-employee cost to a corporation.

If we take this adjusted amount of $67,387.20 (median household salary, plus the 20 percent overhead) and multiply it by the 127,100 employees who worked for Johnson & Johnson in 2015, the total comes out to about $8.565 billion, a little over 12 percent of the company’s gross income for the year. Alex Gorsky’s compensation package of $25 million represents 0.29 percent of all employee compensation, and 0.04 percent of gross income. That is, if you were to spend $100 on Band-Aid adhesive bandages (ignoring for the moment the amounts that your pharmacy and other distributors will take from that amount), 4 cents of that purchase would be used to pay for Gorsky’s lavish lifestyle.

Is it wrong that 4 cents of every $100 purchase for healthcare products is being used to pay for a single corporate executive? It’s a difficult philosophical question that, fortunately, has almost no bearing on our present discussion. I’m more shocked by the 30.3 percent of the company’s income, as noted in the annual report, that is consumed by “selling, marketing, and administrative expenses.”

Since total US spending for all healthcare in 2015 was $3.2 trillion, the reality is that Gorsky’s salary has no real impact on overall costs, nor does the total compensation of all twenty of the listed CEOs. So while it is certain that executive pay is not driving the large increases in healthcare costs, something is, and we will discover what that is in upcoming articles. What is clear for now is that you are buying a lot of Band-Aids.

[Image Credits: pexels.com/energepic.com]

July 5, 2017

Why Healthcare Costs So Much – Part 2

(This is Part 2 in a continuing series on the cost of healthcare in the United States. Click here to read Part 1 in the series.)

Before we attempt to isolate the sources of high medical care costs, we first need to identify exactly what we mean by medical care. As it turns out, “healthcare” means different things to different people. Some focus on the actual act of medical care itself, where a doctor provides treatment options for someone afflicted with an injury or illness. But for others, the term has come to cover as large swath of socioeconomic issues, including standard medicine, mental health services, medical insurance, regulations that govern employer-sponsored plans, long-term care, the development of new medicines and technologies, government-funded studies of medical concern, Medicare and Medicaid, tax policy related to healthcare, and so on.

Unfortunately, having healthcare defined so loosely makes it difficult to isolate the different elements. Over the past week, as Republicans in the Congress were rolling out their proposed adjustments to the Obama-era Affordable Care Act (the proposed bill is known as H.R. 1628, the “American Health Care Act of 2017“), the general consensus among those who disagree with the suggested changes is that it will take away healthcare for millions of Americans. When the term “healthcare” covers so many things, it’s hard to know exactly what such claims refer to, or whether all such claims are relevant to the core discussion of healthcare costs for individual Americans.

For example, consider the objective of the Obamacare legislation: making healthcare affordable. That goal, at least in the popular media, was never focused on the cost of medical procedures, but on the cost of the insurance coverage that would pay for such procedures. This is a confusion in terminology. Medical insurance and medical care are not the same things, but because “healthcare” often includes them both, the dialog gets derailed. The desire to conflate them ensures endless adjustments to government regulations and never-ending political arguments, but the core truth is that they are different things, and should be treated as distinct in any discussion about medical costs.

When you buy groceries, you would never lump the intricacies of debit card processing under the general title of “grocery shopping.” Your bank account has only a tangential association with the grocery industry, in that it is a common tool for making food purchases. But it is not itself “grocery shopping.” The same goes for car insurance, something more akin to healthcare coverage. While all states mandate automobile insurance, changes in laws related to that coverage are never met with screams of, “they are taking away car travel for millions of Americans.” That’s because transportation and automobile insurance are two distinct realms of the economy and of our daily lives.

In this series, we will treat insurance and medical care separately, because it’s the proper thing to do. We will also dispense with emotional appeals that pretend to be about medicine. One of the biggest gripes in matters of public policy is the role of the rich. “Republicans want to eliminate coverage to benefit rich Wall Street fat cats,” goes the storyline. Besides being ancillary to the discussion of medical costs, it’s a complete fabrication. Oh, I don’t doubt that there is some politician somewhere making a backroom deal with some high-level medical business leader, in a way that sticks it to the taxpayer and middle-class Americans. These actions, when identified, should be exposed and condemned. But such shenanigans went on long before medical care became a national concern. Political corruption is an important topic, but it should not be housed under the umbrella of healthcare. And as we will see in upcoming articles, even if this concern were true, it would have little impact on overall costs.

Another supposed healthcare concern is the disparity of access between the wealthy and the poor, that the rich have easy access to costly, life-saving medicines and procedures not available to those with limited resources. This, of course, is true. The rich have always had access to products and services that the poor and even the middle class could only dream about, whether the focus is on housing, food, cars, or entertainment. It doesn’t feel right, and as a not-rich person myself, I have some sympathy with this complaint. But it is not, in itself, a healthcare issue, because the same financial objection could be made in most industries that offer products at varying price points.

As we delve into the actual causes of high healthcare costs, we’ll run into some of these side issues that are not real healthcare concerns. Because medical care often involves emotion experiences—the illness or even death of a loved one—it’s not always easy to rationally isolate the issues. But fortunately for us, the analysis of public policy is not the stuff of emotion, but a dispassionate though important activity that, when done well, can bring benefits to everyone.

[Image Credits: flickr/Images Money]

June 27, 2017

Why Healthcare Costs So Much

Healthcare is perhaps the most visible domestic policy concern for Americans here in 2017. Whether it’s the president and Congress arguing over the fate of Obamacare, or the constant stream of TV commercials for old-people drugs, our daily experience includes an endless concern over medical care.

Part of this has to do with the increasing costs associated with health insurance and provider care. Not that most people pay the full costs themselves. In 2015, for example, 84% of Americans had at least part, and often most, of their healthcare premiums covered by an employer or government program. But those premium payments don’t manifest out of thin air. The money to pay them has to come from somewhere, leading to lower base incomes for employees with health policies, or higher taxes that cover government-sponsored or reimbursed plans.

Beyond the subsidization of insurance premiums, there are also significant out-of-pocket costs. Thanks to inflation, prices for most things are constantly on the rise, but healthcare regularly outpaces the basic inflation rate (see table 1).

Table 1. Healthcare Increases by Year

Year

Inflation Rate

Healthcare Increase

2006

2.5%

6.5%

2007

4.1%

6.5%

2008

0.1%

4.5%

2009

2.7%

4.0%

2010

1.5%

4.1%

2011

3.0%

3.5%

2012

1.7%

4.0%

2013

1.5%

2.9%

2014

0.8%

5.3%

2015

0.7%

5.8%

Source for Healthcare Increases: “National Health Expenditures Summary Including Share of GDP, CY 1960-2015,” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Source for Inflation: BLS Inflation Rate.

These higher healthcare costs do not even take into account increased premiums paid by individuals or families who must fund their own policies, or the higher deductibles that nearly everyone is seeing. Healthcare costs seem to be skyrocketing, well beyond other sectors of the economy. The question, of course, is why.

The general perception is that greedy insurance companies, drug companies, and doctors are driving the increases. One can always find examples of corporations behaving badly with profits or regulations, but anecdotes are not the same as institutional trends. If medical insurance is such a lucrative business with record profits just a greedy boardroom decision away, why are so many insurers exiting local markets? There is also the question of why those working in medical industries would be any more inclined to greediness then, say, those who run grocery stores.

A friend recently told me that healthcare is too important to leave in the hands of ordinary businesses. If we look at the industry as a place where the ill and infirm are drained of their life savings for pure ego and profit, then it’s understandable that someone would balk at for-profit companies doling out healthcare for money. And yet, most of us have a heartfelt respect for doctors, and we depend on hospitals to support us in a crisis. How can we praise providers one minute, and condemn them as thieves and charlatans the next? What is the big deal with the medical profession, and why are we pumping all our money into it?

We’ll look at these questions and more in upcoming articles. And we’ll try to do it all without resorting to hysteria and anger, feelings that, like healthcare costs, appear to be on the rise across the nation. If you’ve been confused by the battle over the cost of healthcare, or even a little angered, then let’s take some time together to thoughtfully find out why this industry is consuming all of our thoughts and bank accounts.

[Image Credits: pixabay/Unsplash]

June 20, 2017

Today’s Breaking News: It’s Not All Bad News

The last twenty years have been tough for the news industry. Although I still subscribe to a daily newspaper (“Now available five days per week!”), the service is a bit of a dying art, as well as a decreasing source of income for media companies. As people look elsewhere for their information, news organizations are doing all they can to grab more eyeballs, and more advertising-generated income based on those views. And since “news” often means “bad news,” it’s no surprise that major newspapers push the misery in an attempt to reach a broader audience.

Consider, for example, an article from the Los Angeles Times, uploaded to the newspaper’s website on June 16, 2017. Coming on the heels of an announcement by President Trump that America will withdraw from the Paris Climate Agreement, the article, titled “‘Very unhealthy’ smog levels expected during heat wave, SoCal regulators warn,” raises environmental concerns stemming from a short-term confluence of pollution and high temperatures. The headline itself is accurate: officials at South Coast Air Quality Management District did issue a warning of “unhealthy to very unhealthy” air in tandem with a heatwave expected over the Los Angeles Basin in the upcoming days. But beyond that meaningful notification for those who may suffer from lung ailments, the story goes on to pontificate about the dire consequences of the AQMD’s statement.

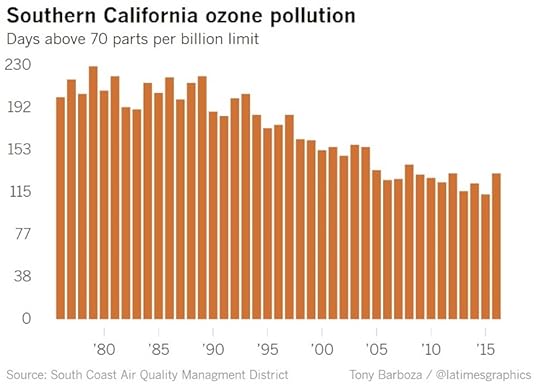

The high point of the article is a graph showing levels of lung-damaging ozone in Southern California since the mid-1970s:

The article provides this conclusion immediately following the graph:

“The health warnings come as Southern California has experienced an increase in bad air days following decades of improving air quality.”

Using data from the AQMD’s web site, the article author buttresses this ominous caution by pointing out how “last year the region experienced its worst smog season in years, logging 132 bad air days and ozone concentrations not seen since 2009.”

Again, all of this information is accurate, and yet, instead of being a simple story about a short-term air alert, the article inserts forty years of pollution history, leading to a dire warning about “the worst smog season in years.” In other words: “We’re all gonna die!” Well, perhaps I’m reading a bit too much into the text, but the article nonetheless alters the true meaning of the data in a way that changes mundane news into the biggest news story you’ve heard about pollution this week. That ought to sell some papers.

The article exaggerates the impact of the core story by ignoring or misrepresenting three important aspects of the reported data. The first deals with “an increase in bad air days following decades of improving air quality.” That statement is based on a lone data point, the 2016 number, which shows 132 total bad-air days, compared to the 2015 number of 113 such days. But this higher 2016 data point comes in the midst of a downward trend in the data, one that includes localized ups and downs. Although the 2016 numbers are up, concluding that there is an overall increase “following decades of improving air quality” is a hasty generalization, since a lone data point is insufficient to indicate a reversing trend.

Secondly, the graph included in the article, while meaningful, hides the fact that the standard by which air quality is measured in the Los Angeles area has been tweaked repeatedly since the 1970s. The plotted data uses the current federal standard, established in 2015, that defines unhealthy levels of ozone as anything beyond 70 parts per billion (PPB). But this new level represents the third adjustment to the standard over the years. The previous adjustments came in at 75 PPB in 2008, 80 PPB in 1997, and 120 PPB before that. As technology has brought a dramatic improvement in air quality, the standard has improved with it, but with the side effect that an errant use of this standard can indicate bad news when no such news exists. If the article had charted the number of bad-air days under the original 120 PPB standard, it would have shown a significant decrease between 1975 and 2016, from 194 bad-air days decades ago, down to just 17 such days last year. By adjusting the standard, the opportunity for panic remains high.

Finally, the article fails to take into account changes in population and technology that occurred over the 40 years covered by the chart. Population in the Greater Los Angeles region has nearly doubled over that timeframe, from around ten million in the mid-1970s, to near 19 million today. Despite this increase in residential numbers, and the parallel increase in automobiles, air quality in Southern California has continued to improve. And with the advent of hybrid and all-electric cars, there is every reason to expect this trend to continue unabated.

The article does not make any direct claim that calamity is coming. But by using a single data point to skew long-term conclusions, and by glossing over the history of improvement in the area, the text communicates an undertone of future death and destruction in the very air you breathe. This reporting style shows up across the spectrum of news topics. From healthcare to national politics, and from race relations to climate change, the trends as reported in national and local news sources paint a ghastly image of a doomed world.

Certainly there are truly bad-news stories, and it is entirely appropriate to understand current events and take action based on the latest information. But by turning anecdotes and even dull news into potential calamities, we run the risk of making choices that are even more harmful than the core data could ever predict.

[Image Credits: flickr/traveljunction]

June 13, 2017

Review: Johnny Carson

On a recent flight back from Japan, I decided to read something light and carefree, since we were traveling in an extremely heavy metal tube six miles above the ocean, without any strings to hold us up. Not that I was worried. The book was the slightly dated Johnny Carson, written by the late entertainer’s long-time lawyer, Henry Bushkin.

Younger readers have perhaps have heard of Carson, though the name-dropping throughout the text might pass them by without interest. Even I barely remember Rich Little and Joyce DeWitt, the latter of whom dated the book’s author for a few years. More than just a lawyer, Bushkin was the late-night talk show host’s business partner, drinking buddy, and confidant, and perhaps even a friend, at least to the extent that Carson had friends. While Americans saw a talented and witty conversationalist on their TV screens most weeknights, the true Carson was short-tempered and petulant, a complicated man made miserable by a mother who found nothing but disappointment in her offspring.

What Johnny lacked in friendships, he more than made up for with riches. Through his various business ventures, some organized by Bushkin, Johnny Carson became one of the wealthiest men in Hollywood. While he did not crave money, it became a useful tool with which he could fill the emotional cavern dug by his mother. And there were also the women. In addition to his multiple wives, Carson went through women like they were $100 bills in his wallet.

The Johnny Carson painted by Bushkin is vastly talented, but equally miserable. In Carson’s world, there was only Johnny Carson, and he was not opposed to complicating the lives of others if it meant getting his way. Carson encouraged the author to join him in his frequent revelry, leading to Bushkin’s own bitter divorce. In later years, Carson and Bushkin had a falling out over a business misunderstanding. Despite the troubles that came from the author’s relationship with Carson, the book is not a hit piece, but an attempt to describe a complicated friendship with a wealthy, intelligent, dysfunctional celebrity who might have been incapable of true friendship.

The womanizing as described in the book was perhaps the most shocking aspect. But even more shocking is how it was swept under the rug throughout his lifetime. Johnny’s divorces were no secret; I recall him making angry jokes about them in his nightly monologues. And it was common knowledge, especially in the era of Carson’s Tonight Show tenure, that among the actors, star athletes, politicians, and others who had attained Carson’s level, some were committing adultery on a nightly basis. And yet, you never hear of anyone being upset at Carson’s lifestyle, then or now.

Not that Carson’s behavior should have been tolerated, no matter how cruel his mother had been to him. But it’s a curious part of our society that the indiscretions of some celebrities are ignored or accepted, while they are made a point of condemnation for others. Carson, JFK, and even Bill Clinton are accepted as they are, flaws and all, despite regular womanizing. Donald Trump and Bill Cosby, on the other hand, receive public censure from even the slightest hint of immorality. Perhaps it’s because the former group entertained us, or are remembered primarily for the level of entertainment, amusement, or acclaim they imparted in our minds. Or maybe it’s politics. Or possibly, it’s just random.

Bushkin makes no attempt to address or answer such questions in his book, although he does lament, years later, the things he lost by acquiescing to the temptations inherent in Carson’s environment. The book is entertaining, though not happy. You get a well-rounded account of one of the country’s most well-known personalities. And if you find yourself on an airplane, tempting the forces of gravity, and just want to avoid the deep thought of why society’s moral compass seems to fluctuate with surprising regularity, Johnny Carson will give you the right amount of entertainment for a few hours. And that’s precisely what Johnny wanted for the viewing public.

June 6, 2017

The Worldwide Threat against Enlightenment Ideals

Since the election of Donald Trump last November, our social media and public news sources have streamed a never-ending wave of fear and concern over how Trump, as president, might use or abuse his power. While I think many of the commentaries are overblown, I agree with the core principle of being vigilant against potential or realized forms of tyranny. Such vigilance is especially important anytime a nation’s citizens are unaware of what the telltale signs of tyranny actually are.

I was reminded of this truth while watching a recent video by the media organization Vox, which discussed the April 16, 2017, Turkish referendum. That national vote, by a narrow margin, approved sweeping changes to Turkey’s governmental structure. I don’t know that much about the political situation in Turkey, but one section of video was very familiar, since it covered questions of government policy that America dealt with more than two centuries ago.

According to the video, the referendum increased the powers available to Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, and it provided examples of five specific grants of executive authority.

Increased control of the federal budget

Increased control over the military

Ability to appoint judges without needing additional legislative approval

Ability to dissolve parliament “anytime he wants”

Authority to extend his own term limit up through 2029

Two of these points, the unbridled abilities to appoint judges and dissolve parliament, were very familiar, since they parallel two of the grievances that the American colonists issued against King George III in the Declaration of Independence. Thomas Jefferson, the primary author of the Declaration, accused the king of usurping powers granted to Americans and their local legislatures, and included a list of twenty-seven specific complaints. The fifth complaint addresses the king’s unwarranted control of colonial legislatures:

“He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people.”

The English Bill of Rights of 1689 limited the control that the king had over the English Parliament, but through his colonial governors, he still exercised the power to unilaterally prorogue or dissolve a regional legislature. The colonists viewed this as a clear violation of their rights as granted by Nature’s God, and as guaranteed by British Common Law.

Similarly, the Turkish referendum allows the president to install judges at will. The ninth grievance in the Declaration of Independence rejects this broad power:

“He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.”

As with the legislative power, the colonists rejected the king’s ability to make judges “dependent on his Will alone” because it had “in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny” over the colonies. Thanks to the work done by Enlightenment thinkers before them, America’s founders were able to recognize the threat, and act to thwart it, though not without some loss of life.

If the Vox video is accurate, then the people of Turkey, albeit by an extremely small margin, have either knowingly or ignorantly granted their leader at least two powers that the Americans considered violations of their rights as humans and as citizens. If so, the hope is that they will recognize their error before tyranny takes hold. Otherwise, if they value their rights, they may have to travel the same, violent path that the American colonists wandered in the late eighteenth century.

[Image Credits: Maurice Flesier / Wikimedia Commons]