Tim Patrick's Blog, page 16

July 6, 2015

Why Instant Societal Change Sucks

The recent Supreme Court decision concerning gay marriage came as a surprise to many on both sides of the debate. I myself had forgotten that such a case was still before the high court. But there it was, a five-four edict that brought with it instant societal change. The decision was a troubling one, not because of what it says about marriage or homosexual rights, but because of what it says about the childish, demanding ways of twenty-first century Americans.

Like most societies, America took the one-man, one-woman thing in marriage for granted. Some cultures are fine with polygamy, but until about fifteen years ago, I had not heard of any state-approved same-sex marriages. Yet even if history is on the side of traditional marriage, institutions, whether rightly or wrongly, do change over time. Interracial unions were frowned upon in the early decades of this nation, but demographics show that they are quickly becoming the standard for husbands and wives. That the definition of marriage would change can be shocking, but not completely unexpected. Women can vote, prohibition has come and gone, and cable TV is giving way to online methods of entertainment. Big changes happen all the time.

Such changes typically come with upheaval and conflict, with at least one side kicking and screaming the entire time. In dealing with the slavery issue, for example, America’s Founders understood that the elimination of that peculiar institution would bring with it economic, agricultural, relational, and political transformations, and perhaps even violent, bloody war. George Mason, a member of the 1787 Constitutional Convention and himself a slaveholder, warned of future trauma borne out of the slave trade and the push to eliminate it: “Providence punishes national sins by national calamities.” The association between wholesale change and societal disruption was no surprise to those who had just come through a decisive, even revolutionary, war with England.

But today’s society changers no longer speak of trauma. The current generation suffers from the delusion that massive societal change is by default trouble-free. “Fundamentally transforming the United States of America” is now declared at the highest levels as a right, and one that should not raise a single disagreeing eyebrow. An era of relative peace, financial comfort, and happy endings has dulled us to the reality that life is complex, and change is hard. Instead, when things we don’t like threaten to unnerve us, we impose solutions that maintain inner peace at the expense of reason.

Conflict avoidance stunts the intellect, preventing us from grappling with life’s most difficult challenges. This risk-averse stance is a major reason for the nation’s large financial debt; throwing borrowed money at a problem is less jarring than battling over no-win divisive issues. The Supreme Court’s action on gay marriage took away the need for Americans on either side of the issue to think deeply about the why of marriage equality, or to think at all. The saddest aspect of this is that many Americans find the elimination of intellectual rigor to be an overall benefit.

Those who supported the court’s decision do not believe in the core tenants of representative democracy and its need for an educated electorate. Instead, they support a representative dictatorship, an environment where difficult political and societal concerns always have one, simple, unchanging solution, and that solution is mandated by national leaders. Anyone who doubts the wisdom of a declaration is branded a bigot, or worse, stupid. It’s the reason that the White House was able to express its agreement with the high court decision so comfortably with a lighted neener-neener display of rainbow colors.

Gay marriage is a contentious issue, as it should be. It’s new, untried, challenging, and a little shocking for a large swath of the American public. That doesn’t automatically mean that it’s wrong. But it does mean that its introduction will—and should—come with some level of angst and turmoil. That arguments arise as to its validity should come as no surprise. But arguments are not harmful. Debating worldviews is healthy, and historically American. Fiat declarations that cheat us out of the growth and maturity that comes of conflict are not.

[Image Credits: The White House]

May 31, 2015

New C# / VB Book Now Available!

My latest book, the C#-Visual Basic Bilingual Dictionary, is now available for you to enjoy! This reference work documents all features of the C# and Visual Basic programming languages, and provides example source code showing how to use each feature in the other language. It’s like a French-English bilingual dictionary, but for .NET developers!

You can purchase the book today from Amazon.com and other online retailers. The text is available in a handsome 448-page paperback edition, or in equally handsome EPUB and MOBI ebook formats. To get a full list of stores, visit my new publishing web site, Owani Press. Or, enjoy this description from the book’s back cover.

Built on Microsoft’s powerful .NET Framework, C# and Visual Basic are complete equals in terms of coding power and application development possibilities. In today’s multi-platform environment, an understanding of both languages is a job requirement. The C#-Visual Basic Bilingual Dictionary unifies the languages by providing clear, functional equivalents for all syntax and grammar differences.

Complete coverage of all language keywords. Nearly 900 dictionary-like entries cover every Visual Basic and C# keyword and grammar feature, including VB’s “My” namespace.

Examples in both languages. Hundreds of code samples in both C# and Visual Basic make translations between the languages clear and easy to understand.

Full support for Roslyn. Each chapter covers the latest language features from Visual Studio 2015 and Microsoft’s “Roslyn” compiler.Whether you work on a team that uses both languages, or just need to understand a technical article written in that “other” language, the C#-Visual Basic Bilingual Dictionary is an essential resource for developers crafting Microsoft software solutions.

To jump to the Amazon.com page for the book right now, click here.

February 16, 2015

Poor Brian Williams. Poor America.

Top NBC news anchor Brian Williams lied in public, and now he has to spend the next six months in solitary news confinement. If his lies were an exercise in self-aggrandizement, as seems to be the buzz, then it’s hard to feel sorry for his plight.

Despite his troubles, Mr. Williams’ actions don’t really have much of an impact on how I experience the nightly news. His alleged lies were about his own actions on the sides of news stories. His false claim that Iraqi baddies shot at his helicopter didn’t alter the reality that War Is Hell, or change the fact that good soldiers are shot down with depressing frequency. An inaccurate quip on his arrival at the felling of the Berlin Wall puts him in a bad light, but it has no impact on the victory over tyranny that the Wall’s destruction meant to those behind the Iron Curtain.

Williams’ fibs are bad news for news, but there is a worse trend in modern reporting, one where a reporter’s lies stem not from self-interest, but from a clear break with reality. Consider one report from the 2014 election a few months back. In the online article, “GOP takeover: Republicans surge to Senate control,” AP reporters David Espo and Robert Furlow tried to explain the surprising electoral outcome that saw strong Republican victories across the nation. In a bit of predictable spin, the reporters opined that “a majority of those [voters responding to exit polls] supported several positions associated with Democrats or Obama rather than Republicans—saying immigrants in the country illegally should be able to work, backing U.S. military involvement against Islamic State fighters, and agreeing that climate change is a serious problem.” (Emphasis added.)

I get the parts about climate change and illegal aliens. Democratic officials frequently offer up these two issues as key planks in their legislative agenda. But “backing U.S. military involvement against Islamic State fighters”? That can’t be right. The current Democratic president ran for office in part on his promise to rid Iraq of its pesky American military presence. He has changed his tune a bit with the rise of ISIS. But even in his recent request to Congress concerning his plan for battling ISIS, President Obama went out of his way to state that his formal military request did not represent a return to troops on the ground. Military might in Iraq is not typically associated with the Democratic Party; it’s viewed as a Republican thing, and has been at least since Bush’s infamous “Mission Accomplished” message back in 2003.

The AP entrusted these two reporters with communicating one of the most important news stories of election week, and they blew it. The authors of the article were either woefully ignorant of party views on foreign affairs in this country over the past decade, or willfully deceptive in communicating the state of those same views. In either case, it does much more damage to news reporting than any of Brian Williams’ verbal escapades. Even if the AP story was an innocent mistake, it went unchallenged and uncorrected by that news organization, and their web site still includes the errant content.

The problem is not just with these reporters. It’s with readers who will pass by the statement with nary a thought as to its veracity. The polarization of this age has produced a generation of weak-willed news consumers who demand reporting that confirms their prejudices. Republicans (or Democrats, depending on one’s political bent) are evil, and news stories must confirm that. Obama (or Bush) is a hack and a sell-out, and any story that deviates from that narrative is verboten. There is a modern insistence that all the trouble in the world be personally trouble-free, that reporting not ruffle the feathers of news consumers lest they should have to react and turn the channel or click away from the web site.

And so military action in Iraq becomes a Democratic hallmark, because it jives with the sensibilities of a reporter or an audience who know in their hearts that this president, and only this president, has always had the right response to Islamic aggression. The facts are irrelevant; this is news! This isn’t a case of political disagreement. It’s a situation where disagreement doesn’t exist because a political viewpoint is deemed the only that that can ever be classified as real. Not just true or right, but real.

Poor Brian Williams. Despite his flaws, he seemed genuinely interested in being the best talking head in the industry. This charge might mean the end of his career, but probably not. In a world that values perceived reality above facts, Williams might be the new poster child for news reporting.

[Image Credits: NBC News]

February 9, 2015

Supply and Demand and Wishing and Hoping

Purchasing and maintaining a home has always been a major cost for American families. The “Great American Dream” is a dream precisely because the effort and funds needed to buy a home go beyond the mundane. But in recent years, two new expenses—healthcare costs and college tuition—have risen to Great American Dream levels thanks to politicians who think that wishes and hopes are more dependable than basic economics.

We’re only a month or so into 2015, and President Obama has already taken the prize for the biggest lack of understanding about how prices work. In his State of the Union speech on January 20, the President called for a new federal strategy that would “lower the cost of community college to zero.” His goal is admirable: increase job prospects for America’s high school graduates by providing more education without the burden of tuition. He even had an example young couple there in the audience, Rebekah and Ben, who were suffering under the heavy weight of student loans. The program, if enacted, would certainly benefit some anecdotal youths like Rebekah and Ben. But it would not “lower the cost of community college.” In fact, it would do the very opposite.

As you might recall from your free enterprise classes back in high school, prices are driven by supply and demand. When the supply of some item increases or demand decreases, the price goes down. Conversely, when an item is scarce or demand increases beyond current supply levels, prices go up. My college political science professor described price increases as “too many dollars chasing too few goods.” Monopolistic practices or a weekend sale can override a default price temporarily, but the overall ebb and flow of prices are still driven by the quantity of a product or service, and the number of buyers who want it.

The President’s plan to make community college free will increase costs because it will increase demand without adjusting supply. His goal, naturally, is to enhance the number of community college students. In economic terms, the goal is to increase the demand for community college courses. If the number of courses and professors rises to meet the demand, the price will remain stable. But without that increase in course supply, the price has nowhere to go but up. It’s true that individual students might not have to pay the fees to cover these price increases, but the price will increase nonetheless, because demand increased. As with any government program, the taxpayers will bear the costs. And not just current costs, but the new increased costs, plus the cost of the bureaucracy to manage the program. Supply-and-demand doubters might wish and hope that the cost of education will go down (to zero) under this program, but it won’t.

This isn’t the first time the President has depended on wishes and hopes. He did the same in pushing Obamacare, the “Affordable” Care Act. In a June 2009 address, President Obama famously stated, “If you like the plan you have, you can keep it. If you like the doctor you have, you can keep your doctor, too. The only changes you’ll see are falling costs as our reforms take hold.” Pundits glommed on to the first half of the quote, but it’s the last sentence that smacks of economic blindness. By expanding the total number of patients who can pay for expensive services using easy insurance dollars, and thereby increasing the demand for such services without at the same time increasing the supply of doctors, hospitals, or other providers, medical costs will go up, no matter how many bureaucrats crunch the numbers. That doesn’t automatically mean that Obamacare is a bad thing, and some Americans might agree with the President that it is a net benefit. But such a vote of confidence does not alter the false statement that the core aspects of Obamacare will reduce costs. (To be fair, some impacts of the ACA legislation might work to reduce demand and therefore costs, such as the move by more Americans to high-deductible HSA-based insurance plans. But these were not the primary intentions of the law, and it’s unlikely they can counteract the overall drive toward higher prices.)

Obama and the Democrats are not alone in wishing and hoping for lower prices in major industries. In 1971, Richard Nixon instituted temporary wage and price controls in an attempt to curb inflation. Freezing the price of, say, chocolate bars might sound like a boon for consumers, since they will not pay any more than current prices for tasty chocolate. But the real impact of such controls is a reduction in the supply of chocolate bars at current prices, resulting in shortages when businesses are unwilling to sell their goods unprofitably at the government-mandated price. These controls, when combined with other protectionist (supply-constricting) policies and the Middle East crisis-of-the-week, resulted in a decade of financial turmoil that, though blamed on President Carter (who certainly didn’t help), was nonetheless caused by an environment of wishing and hoping by presidents and legislators alike. (Nixon reprised his error in 1973 when, in a tortured address to the nation, the former Communist-hunter both extolled the virtues of price controls and condemned them as the “straightjacket” of controlled economies.)

Unfortunately, we didn’t learn our lesson from the Nixon era. President Obama’s tuition announcement proves that politicians at the highest levels are still turning a blind eye to the economic truths of supply and demand. The President hopes that free education will save money and solve America’s employment difficulties, but it won’t. Perhaps even worse, he wishes that the American public would be just as dumbfounded about supply and demand as he is. In this regard, his wish might be coming true.

[Image Credits: freeimages.com, image #348402]

January 5, 2015

Sharing Instead of Insuring

About thirty years ago, a teenager in my church developed cancer around his knee. The doctors had no choice but to remove the diseased section, but they were able to leave him with a functioning limb by rotating the foot and turning his ankle into a knee, which is awesome. But that was the only awesome part. Eventually, the cancer spread, and young Jon died before reaching his twenties. His family suffered not only through his illness and death, but also through tremendous hospital bills from his extensive treatments.

Our pastor offered spiritual encouragement, but that didn’t pay the bills. Instead, the members of the congregation helped cover the costs through public fundraisers, and by writing personal checks directly to the family. By the time I left the church for college, I heard that all of the medical bills had been paid in full. It was a monetary fulfillment of what the church preaches through Galatians 6:2, “carry each other’s burdens.”

At some point, a few Christians with business savvy decided to institutionalize this carrying of burdens, which should throw up big red flags. And yet here I am, decades later, becoming a part of one such group. Starting in 2015, I am forgoing traditional medical insurance, and instead signing up for Medi-Share, a national organization designed to let people pay for each other’s medical bills somewhat directly, but in a way that has the look and feel of medical insurance.

A big reason for the change was cost. This weekend, I was tossing out some old bills and paperwork, and I saw that my monthly premiums had doubled in just four years. Obamacare (and the state-level regulations that preceded it) has not been kind to my family. But I’ve also never been comfortable with company-paid, low-deductible, cost-hiding insurance plans that we’ve taken for granted for decades. Medi-Share, with its focus on caring for “burdens” instead of on basic medical needs, is more in line with my expectations for medical insurance.

But it’s not insurance. Medi-Share’s web site states clearly that it “is not insurance…and is not guaranteed in any way.” It offers no coverage for routine preventative care, including annual checkups, mammograms for the womenfolk, and regular colonoscopy screenings for the older set, something I’ll need to think about in the approaching years. Also, because of the organization’s religious underpinnings, they only allow Christians in good standing with a church to join, and any medical costs that stem directly from intentional sin—injuries sustained from a car accident after an evening of heavy drinking, for example—are rejected from coverage. My biggest concern has to do with the group’s prescription program, as it only covers a given medicine for up to six months, even for chronic conditions like high blood pressure.

On the positive side, the monthly costs are lower due to the plan’s limitations on coverage. Medi-Share’s PPO network is much larger than the one I had before, and is accessible nationwide (except in Montana!). Plus, once you’ve fulfilled the fairly reasonable annual deductible, approved medical costs are covered 100 percent. I will need to shell out $200 to talk to my doctor each year about routine stuff, but a $60,000 hospital charge for a heart attack isn’t going to lead to a second stress-triggered infarction.

I must admit that I’m a little uneasy about giving up familiar insurance for a no-guarantee program. And the plan itself might anger some, with its religious tests and its indifference to daily medical concerns. I’d love to see other groups spring up that target different audiences or that offer expanded coverage, but that can’t happen for now. The same Obamacare legislation that includes an exception for Health Care Sharing Ministries (section 1501 of the ACA, pages 147-148, “Religious Conscience Exemption”) also restricts the practice to religious groups, and only those that have offered pseudo-insurance services since December 31, 1999.

Despite my qualms about this change, I’m optimistic about what Medi-Share has to offer. Replacing traditional coverage with “sharing” is certainly a risk, but not necessarily more than I had before. It’s a confusing time for medical care in America, but the idea of freely donating money to others in need has never been confusing.

December 7, 2014

Japanese Language Proficiency Test

When my son signed up to take the SAT test, one of my first thoughts was, “I glad I don’t have to go through that nightmare again.” And yet here I am on December 7, taking the N3 level of the 日本語能力試験 (nihongo noryoku shiken, the Japanese Language Proficiency Test). N3 is the middle of five levels, inconveniently arranged from 5 to 1 based on the difficulty level of the test. This handy list shows you the expectations for each level.

N5 — You enjoy the taste of sushi.

N4 — You took one semester of college-level Japanese, or nailed that Japanese for Wandering Americans book on the flight east.

N3 — You took two or three years of college Japanese.

N2 — You spent two or three years running a college in Japan.

N1 — You play go with Emperor Akihito.

Clearly, I’m going to stop with N3. I started Japanese studies 25 years ago, but found myself stuck at the same second-college-year level. Taking the JLPT, I hoped, would spur me to study with more rigor. It worked in part. I finally made it through my kanji book with its 2,200 glyphs, and I probably added 1,000 to 2,000 new words to my vocabulary. But I skimped on new grammar points, which is of course the only thing covered by the test.

This year, the test takes place on the campus of California State University Los Angeles (“Motto: No, you want UCLA. Let me get you a map.”) I’ve scheduled this post to appear at the apex of my stress level, just as I sit down to begin the test. If you’re reading this right when it comes out, then you missed your chance to take the once-per-year exam. But if you enjoy Japanese food or are looking for a challenge beyond your weekly go games with the emperor, then this might be the test for you.

October 23, 2014

It’s Just Not Fair

In a free society, there is no such thing as a “fair share.” The freedom that individuals have to create or squander their wealth and resources ensures that no two people will have a completely equal and fair proportion of a nation’s riches. Even for those in Communist regimes, fairness quickly gives way to power and graft. Fairness, though desirable, is elusive.

During a recent campaign and fundraising tour, Vice President Joe Biden attempted to force a false sense of fairness on the American public. “I think we should make them start to pay their fair share,” Biden said of America’s richest citizens, expressing a desire by many to “take the burden off the middle class.” Since he didn’t come right out and state an amount that the rich should pay, we will have to make an educated guess as to what he meant.

Ever since the Sixteenth Amendment made possible a national income tax, the rich have always paid more than their fair share. Just months after ratification of the amendment, Woodrow Wilson signed the Revenue Act of 1913, imposing a 1% tax on households earning $4,000 or more per year (equivalent to $96,000 in 2014 dollars), rising to a top rate of 7% for those making more than $500,000 (about $12 million today). Democrats controlled both houses of Congress in those days, so it seems likely that even a Progressive like Wilson found the tax rate he signed into law “fair.”

Today, the top rate for upper-income Americans sits close to 40%, although after deductions, the richest 10% of taxpayers pay about 19% of their incomes to the IRS. That’s still nearly triple the top rate from a century ago, and significantly more than the typical 3% rate currently paid by the bottom half of all income earners. (All data is from 2011 IRS statistics, and conveniently summarized here.)

The top 10% of taxpayers earn about 45% of all incomes in America, and yet they pay more than 68% of all income taxes. If life were truly fair, they would only pay 45% of all income taxes, in line with their incomes. But things aren’t fair, and in general, everyone is OK with that. Even the rich understand that a progressive tax system that charges them about six times the rate paid by the poor, while not actually fair, is acceptable.

When Mr. Biden called for the rich to pay their fair share, he certainly wasn’t demanding that their tax rates be lowered to match their incomes. He may have instead wanted marginal tax rates raised, but it’s hard to explain how an extra 5%—or even 20%—in addition to the current 39.6% top rate is inherently more fair. Would 100% be the ultimate in fairness?

The Vice President, as an elected official with a top-secret security clearance, has access to the same Internal Revenue Service statistics that I do. He has no excuse for tossing out the “fair share” misstatement, unless he meant something else by it. If his intent was to drive tax policy, he could have stated a number instead. But it seems more likely that his goal was to stir up emotional animosity in a way that will motivate voters this coming November. “Fair share,” it seems, really means, “Vote for Democrats.” It’s a propagandizing form of politics that is, at its heart, extremely unfair.

[Image Credits: Microsoft Office clip art]

October 14, 2014

The Forgotten Language of My Youth

I took four years of high school French, primarily because it wasn’t German. German was mach-uber-scarrrry, with its hundred-character words and its link to some of history’s greatest wrongs, like lederhosen. But French was soft and lyric. In my classes, I loved saying the French word for “garbage,” which is “garbage.” Only better.

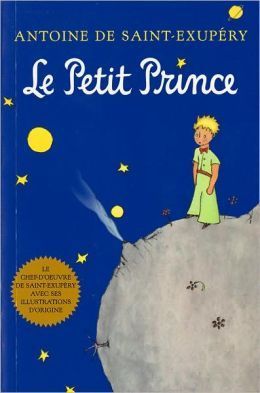

By my senior year, only about a half-dozen students had stuck with the language, and as a reward, Madame Virgillo had us read two French classics that we had no hope of understanding, even in English: Voltaire’s Candide and the subject of today’s musings, Le Petit Prince, by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. She also had us watch a truly bizarre French movie called L’Argent de poche, which included young kids telling dirty jokes and a scene where a toddler falls out of a third-floor window only to jump up and play gleefully. Between the surreal movies and Voltaire’s scathing political satire, it’s surprising that we didn’t switch to the German classes and invade.

The Little Prince is one of the most published and beloved novels in all of human history, having been printed more than 140 million times in over 250 languages, including a Latin version that my son has for his own high school foreign language travails. And it is so French, filled with liberté, fraternité, and snakes that swallow whole elephants. In the story, a pilot crash-lands in the Sahara Desert—something that did in fact happen to the author—where he meets up with a diminutive prince, recently arrived from his asteroid homeland. Through their conversations, the two explore the strangeness of being an adult—at least up until the childlike prince tries to commit suicide. Bread and Jam for Frances never had a suicide scene, even with “France” in the title.

It’s been many years since I read this work, but I still recall the opening words: “Lorsque j’avais six ans j’ai vu, une fois, une magnifique image…” (“When I was six years old I saw a beautiful picture….”). It’s a simple opening for a book that is deeply philosophical and at times political. The baobab trees that try to take over the prince’s asteroid, for example, represent Nazi aggression. Naturally. It’s not a straightforward book. But if you can catch the subtle allegories, an adult can get a lot out of the text. And a child will get even more. Especially if they can read French.

October 6, 2014

Big-People Dictionary

It was back in fifth or sixth grade that someone gifted me Merriam-Webster’s Vest Pocket Dictionary, a blue, smallish reference book of very few words, marginal utility, and if memory serves, much excitement. It was such a desirable book that, even though my mother purged it from my shelves in the Great Garage Sale of 1980, I was able to pick up a replacement used copy about a decade ago.

What drew me to this work wasn’t its depth of content. Most of the definitions top out at five or six words. It certainly wasn’t the number of entries since even with the elderly-offending font, its 370 pages leave little room for variety. (The X, Y, and Z sections together utilize all of two-and-a-half pages.) And it definitely wasn’t the pedagogical import, since I doubt I looked up more than one hundred words total while it was in my possession.

What made it a significant book can be summed up in one short definition.

grown-up \’grôn‚əp\ n: adult —grown-up adj

This small dictionary wasn’t one of those grand library editions, nor was it a childish “beginner’s” dictionary common for the younger set. This was a dictionary that mimicked the look and feel of a big people’s dictionary—each entry even included one of those incomprehensible pronunciation guides—but was still small enough to travel around with a juvenile. This book declared to an elementary school student: “You are grown up, and deserve grown-up things.”

With the advent of dictionary apps and Wikipedia, small reference books like this don’t carry the same emotional charge as they did decades ago. I asked my teenage son what he thought of the book, and his first response was, “It’s bigger than my phone.” Sigh. Kids today, once I chase them off my lawn, have ready electronic access to the wealth of human knowledge. Perhaps that makes them more grown-up than I was at that age. Yet I wonder if putting such power in their hands so early removes opportunities for simple, joyful discovery made possible through things like vest-pocket dictionaries.

September 17, 2014

Review: Darwin’s Doubt

I start this review with an obligatory disclaimer: I am not one of those science-hating creationists. It’s a testament to the state of public discourse in this country that I have to include that preface. But admitting openly that I read a book with a title like Darwin’s Doubt carries certain risks. It’s the kind of publication that you have to wrap in a copy of Lady Chatterley’s Lover if you want to read it on the subway.

And yet, it’s not that bad. In fact, Darwin’s Doubt is a surprising book, one of those works that stirs in you those feelings and ideas that you had all along, but didn’t know how to articulate or even whether you should.

The book’s title comes from portions of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species where he discusses possible problems and setbacks with his overall theory of descent from a common ancestor. Darwin was familiar with the Cambrian Explosion, a ten-million-year block of time approximately 540 million years ago that saw a rapid increase in the number and complexity of biological forms. The geologically sudden appearance of such diversity differed from Darwin’s view of gradual transition. In light of this apparent conflict, Darwin sought to assure his readers: “If my theory be true, it is indisputable that before the lowest Silurian [Cambrian] stratum was deposited, long periods elapsed, as long as, or probably far longer than, the whole interval from the Silurian age to the present day; and that during these vast, yet quite unknown, periods of time, the world swarmed with living creatures.”

Darwin, it turns out, was wrong. While the world did swarm with creatures before the Cambrian era, they weren’t that varied. More than a century of research has shown that the Cambrian Explosion is what it is: a blink of an eye that produced creatures at a rate that far exceeds Darwin’s estimates. How did life appear so rapidly? In the absence of a powerful deity, what would be needed to make this happen?

What is needed is information. According to Stephen C. Meyer, the book’s author, advancements in life are in reality advancements in digital information in the form of DNA and epigenetic content. “Building a fundamentally new form of life from a simpler form of life requires an immense amount of new information.” It’s as if a room full of monkeys started banging on typewriters and produced, not works of Shakespeare, but complex computer algorithms. Randomly generating this level of quality DNA seems unrealistic to Meyer. The heart of Darwin’s Doubt is an exploration of why an increase in functional DNA-based information could not come about through neo-Darwinian evolution alone.

Meyer addresses this possible impediment to materialistic evolution by looking at four key issues: (1) the likelihood of random processes generating beneficial and usable genetic material, (2) the time needed to generate this digital genetic information, (3) the window of time in a species’ development when DNA-generating mutations must occur, and (4) whether DNA alone is sufficient to build new life forms.

Darwin himself was not aware of DNA or of how genetics worked at the cellular level. In today’s neo-Darwinian world, it is well understood that genetic mutations must drive speciation. Cellular mutations are common, but generally deleterious; we call some of them “birth defects.” Even if a mutation could be considered neutral or beneficial, Meyer explains that there need to be enough coordinated mutations present to generate a new protein fold. “New protein folds represent the smallest unit of structural innovation that natural selection can select…. Therefore, mutations must generate new protein folds for natural selection to have an opportunity to preserve and accumulate structural innovations,” an action that is unlikely by Meyer’s calculations.

Meyer’s second point deals with the study of population genetics. Given the size of a population, its reproduction rate, its overall mutation rates, and the tendency for natural selection to weed out members with diminished genetic fitness, how much time is needed to generate new genetic information that would result in the transition to a new type of creature? Quite a lot, it turns out. “For the standard neo-Darwinian mechanism to generate just two coordinated mutations, it typically needed unreasonably long waiting times, times that exceeded the duration of life on earth, or it needed unreasonably large population sizes, populations exceeding the number of multicellular organisms that have ever lived.” Since the majority of genetic advancements would require more than two coordinated mutations, the numbers quickly become more severe.

Timing also plays a key role in genetic transmission. To have a development impact, Meyer notes that mutations must come early in the evolutionary lifetime of a species, when populations are still small and morphological changes have the best chance of taking hold. However, mutations at this stage also have the biggest probability of imparting damage, and similar changes in larger populations are more likely to be removed by natural selection.

Finally, Meyer discusses epigenetic information, the instructional content stored in cell structures but not in DNA sequences themselves. This information is essential in driving the overall body plan of an animal as it develops from a single cell to its full adult size. What is not clear is how it could be altered through genetic mutation, since specific epigenetic pressures are not coded directly by the DNA base pairs. There is also the issue of “junk DNA,” those coding blocks of the genome that were once thought to be useless castoffs of evolution, but are now understood to drive biological processes in living creatures.

In its more than 500 very accessible pages and its 100-plus pages of footnotes and bibliographical references, Darwin’s Doubt does at good job at expressing Meyer’s own doubts that “wholly blind and undirected” evolution could produce the variety of life we see on earth. As the director of the Discovery Institute’s Center for Science and Culture, Meyer is a strong advocate for Intelligent Design. “Our uniform experience of cause and effect shows that intelligent design is the only known cause of the origin of large amounts of functionally specified digital information. It follows that the great infusion of such information in the Cambrian explosion points decisively to an intelligent cause.” His book makes a strong case, although the appeal to non-materialistic explanations will always turn off some readers. As proof of the struggle, Meyer quotes Scott Todd, a biologist writing in Nature: “Even if all the data point to an intelligent designer, such a hypothesis is excluded from science because it is not naturalistic.”

So here you have the conundrum. Despite what you read in the news, the science surrounding biological evolution is still somewhat fluid, in part due to the issues raised in Darwin’s Doubt. Yet for those who have reasonable struggles with the evolution-is-settled narrative, it’s hard to shake the baggage carried by those on the religious fringe who insist that any non-literal interpretation of the creation story is blasphemy. Another book on my reading list is Mind and Cosmos, by Thomas Nagel, an atheist who rejects the standard neo-Darwinian view for some the same reasons as expressed by Meyer. (Anthony Flew, once known as “the world’s most notorious atheist,” later came to believe in a deity because of similar issues surrounding evolution.) A book like Darwin’s Doubt requires vigorous analysis to confirm that it is scientifically sound. But if it is, then the neo-Darwinian evolution model itself might turn out to be little more than an intelligently designed idea.