Tim Patrick's Blog, page 18

March 29, 2014

Read Real Microsoft Source Code!

Back in the mid-1990s, I attended an event on the Microsoft campus, and happened to overhear a conversation between two engineers who worked on the company’s popular Excel product. The more experienced programmer was offering advice and guidance to a new recruit, and part of the discussion included a warning not to modify certain portions of the internal Excel source code “because nobody knows how those parts work.” Having spent a lot of quality time on customer projects grappling with some long-gone programmer’s attempt at source code, I didn’t doubt the gist of the conversation. But I had no ability to examine any of the Microsoft Office source code to see for myself if there were in fact portions beyond the comprehension of mere mortals.

Until now, that is. This week, Microsoft announced the public release of the source code for an early version of its Word for Windows application, as well as for two initial releases of its MS-DOS operating system. Microsoft donated the code for Word version 1.1a (from 1990), and for MS-DOS versions 1.1 (from 1982) and 2.0 (from 1983), to the Computer History Museum (press release). The files are posted on the Museum’s web site, and either MS-DOS or Word can be yours for the price of a simple click on a license agreement button.

Be aware: the code is really, really old, at least in terms of geologic software time. Yet those were simpler times. The MS-DOS 1.1 release fit into just 12K of memory—try that with Windows 8.1—a feat accomplished by coding directly in assembly language. It’s compact and terse, and a perfect magnet for bloatware. By the 2.0 edition (included in the same download), the size of the source had grown more than tenfold.

The Word for Windows code is mostly a C-language endeavor. Programming in managed languages and client- and server-side script has dulled me to the former harsh realities of Windows development. I had forgotten that world of message loops, obsessive-compulsive memory management, and the need to draw almost everything on the screen by yourself, including the blinking cursor.

If assembly language and non-OOP C code aren’t your style, you might also consider Microsoft’s .NET Framework Reference Source web site. For years, Microsoft has made much of it’s .NET Framework source code available to developers as a debugging aid, but that access was limited to the Visual Studio environment or a brute-force download of the entire library. A few weeks ago, Microsoft simplified access to the source by webifying it. The updated Reference Source web site lets you browse through Framework source files, a mixture of C# and Visual Basic content.

Beyond these Microsoft sources, the Computer History Museum also offers glimpses of computer code for other historic systems, including Apple II DOS, MacPaint, and an early release of Adobe Photoshop. If you have any geek blood in you at all, take a moment to pull back the veil from these programs.

January 23, 2014

Review: Remembering the Kanji

Any journey through an East Asian language begins with a single brushstroke. That one line begets others, which eventually become a jumble of seemingly indecipherable marks on a page. When I first started my Japanese studies more than two decades ago, I depended on rote memorization for these complex characters, the kanji. I learned to reproduce each symbol by feel rather than thought, a failed strategy as it turns out.

Then I discovered James Heisig and his landmark book Remembering the Kanji. This nearly forty-year-old work brought order to what had been until then a losing game of pickup sticks. Heisig’s method involves telling stories, using one or two keywords for each character as the starting point for the imagination. For some of the earliest and simplest kanji, there’s not much of a story to tell. The character for “five,” 五, gets little more than the “just remember it already” treatment. But once you get a few glyphs under your belt, Heisig starts to combine them and weave tales that bring the kanji to life. “Bright” (明) is built from “day/sun” (日) and “month/moon” (月) components, and his story speaks of “nature’s bright lights,” the sun and the moon, being the source of not only “bright” light, but “bright” inspiration for poets and thinkers.

After 500 or so characters, Heisig lets you take control of story creation for most of the remaining 1,700 characters. Stories that are out of the ordinary or are tied to personal experiences make for the best memories. My story for “post” (職, made from the character for “ear”/耳 and a “primitive” invented by Heisig that means “kazoo”) references Star Wars: A New Hope, when Luke comes out of the Millennium Falcon wearing a stormtrooper’s uniform and a supervisor asks him through the kazoo-quality transmitter, “Why aren’t you at your post?” There’s no rule in Heisig’s book about not leaning on George Lucas’ imagination for your stories.

I first discovered RTK more than fifteen years ago when a friend gave me his lightly used First Edition. I began in earnest, yet even with the great focus on stories, the need to come up with those narratives for hundreds of characters was daunting, and I aborted the process twice. Last year, I decided I would push through. As incentive, I purchased the latest Sixth Edition, a major update that adds the Japanese government’s newest additions to the official list of joyo kanji that all schoolchildren must learn. At about ten new characters/stories per day, I was able to complete the entire book in nine months.

I wouldn’t have made it without the support of an online community of Japanese-learners who cling to the Heisig method. Reviewing the Kanji is a place for mutual encouragement, and also a repository of user-submitted stories for every kanji character in the book. More than half of the stories I hand-wrote in my textbook sprang from the imaginations of other Heisig readers.

Remembering the Kanji is a fantastic resource, but not everyone finds it useful. The focus of the book is found in its subtitle: “How not to forget the meaning and writing of Japanese Characters.” It’s this focus that turns some language learners off. Heisig will not teach you how to pronounce any of the kanji, nor introduce you to meanings or combinations beyond a single, sometimes misleading keyword for each character. It’s all about writing. And yet, this focus on reproduction-from-keyword does bring reason and order to the Sino-Japanese characters, opening a world of language that includes writing, reading, and speaking Japanese.

July 29, 2013

Unity versus Independence

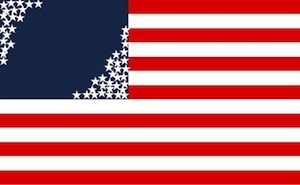

Given the option, government tends to increase its authority and power rather than reduce or distribute that same power. This reality is a major reason why the original American states insisted that the Constitution be ratified only with the addition of the Tenth Amendment: “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” This limitation was easier to visualize when each state desired to retain some of its independence from the others. When the states started to merge into one large unified bloc, that desire for local authority started to slip away.

The federal government does its best to incorporate into itself various “powers not delegated to the United States,” the National Security Agency’s PRISM system among the most recent. The founders knew from their European experience that this coalescence of power was always a risk. What’s surprising today is not that government continues to seek more central power, but that the American populace, from urban centers to the most rural community, has forgotten the key reasons why the states insisted on the Tenth Amendment in the first place, and how their regional diversity played a key role.

The states—the people—used to have more authority in how they ran their jurisdictions. For example, nine of the thirteen original colonies had official religions, and at the time of the Constitution’s implementation in 1789, at least three states—New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Connecticut—still funneled tax income to approved church organs. Massachusetts was the last state to fully disestablish the church in 1833, although some local governments, especially in Maryland, were still requiring political candidates to submit to religious oaths as late as 1961.

My point isn’t that states should have official religions. Even during the Revolutionary War, the colonies were already starting to shed their religious components, and the Fourteenth Amendment, especially as interpreted in the 1920s via the Incorporation doctrine, finally made that practice little more than an anecdote of American history. But these changes in religious practice are just one example of how state and local jurisdictions used to employ self-governance to distinguish themselves within the national Melting Pot. Nearly two centuries ago, states asserted their sovereign authority to the point of civil war. Today, states are slapped down or ridiculed in the public press for even suggesting that they act in a way that is at variance with the federal standard, and in many areas of legal import, they don’t even bother grappling with the state-federal divide.

Humans and organizations both seem to gravitate naturally toward unanimity. Back in the 1980s and 1990s, Apple promoted the ideas of independence and freethinking through its 1984 and Think Different advertising campaigns. Yet here we are in the twenty-first century, and it’s the iPhone rather than its Android or Windows Phone counterparts that now embodies the concept of uniformity, and Apple actively prevents both its users and partners from straying too far from its standard of what a computing life should be.

In Leviathan, Thomas Hobbes described the process by which the members of a commonwealth voluntarily transferred some of their authority to the sovereign, a personification of either an individual ruler or of a collection of national leaders and government structures. In my earlier review of that work, I summarized both the benefits and the risks of such concentrated authority.

Since the commonwealth—Leviathan—is a creature, it has rights just like man does, although these rights are passed on from those in the commonwealth. These rights culminate in a strong sovereign who acts on behalf of the citizens to define laws, enforce contracts, mediate justice, issue rewards and punishments, and carry out peace and war. Because of the need to enforce the rules of society, the power of the sovereign is absolute; he can do no wrong and he cannot be corrected or arrested. He has the power of life and death over his citizens, although he cannot take away an inalienable right from any citizen.

The American founders understood both the need for and the dangers of this Leviathan, and established limits—including the Tenth Amendment—to restrain this “power of life and death over his citizens.” As a nation, unity is a must, especially when dealing with external threats. But internal variations are equally important. Maintaining this balance is messy, and much of that messiness stemmed from each of the states acting in ways that were different and even offensive to the others. But there is nothing wrong with getting a little messy. It’s when we try to keep things unified, when we pay lip service to the idea of checks and balances between the federal and state levels, and when we assume that Leviathan acts only in our best interests, that we begin to lose the civic ideals of independence and variety that the individual colonies fought for.

[Image credits: elitedaily.com]

July 15, 2013

Presidents vs. Heroes

Let’s face it: Obama has blown it. Despite his reasonable desire to invoke the power of government to resolve the national economic situation, his domestic policy decisions have had little to no positive impact on the jobs outlook. Some acts, like the changes in the health insurance industry brought about by Obamacare, may have prolonged the pain. He’s being flogged publicly in the wake of an IRS scandal, and an American citizen sitting in an airport in Moscow is showing the world that the current president’s rhetoric about the overreaching powers of the Bush era was just a way to deflect scrutiny for his own overreaching programs.

I’m not surprised at his failures, since Obama is a lot like Bush before him. George W. Bush ruined any post-9/11 goodwill he built up by poorly managing a poorly explained war, and by engaging in spending behaviors far out of line with the sensibilities of most on the Republican side of the political spectrum. It’s kind of like Bill Clinton before him, whose political acumen meant nothing whenever a woman caught his eye. Or like Bush-41, who broke his number one promise on taxes. Or like Reagan, whose adroit handling of the massive Soviet Union was almost forgotten because he made a mess of a much smaller situation in Nicaragua. Or like Carter before him, who thought that symbolic acts with the National Christmas Tree could overcome his wrong decisions on energy and the economy, or atone for his bungling of the hostage situation in Iran. And don’t get me started on Richard Nixon, Warren Harding, or Zachary Taylor.

The president is our Commander in Chief, the head of America’s First Family, and the public face of the United States to a complex world. Each election season, we vote for a candidate not primarily because of the policies he or she espouses—though we should—but because we desire to put a hero in office. Hope and Change, the terms invoked by Obama during his first run for president, may as well have been Truth, Justice, and the American Way.

We like our presidents to be heroes, and in the majority of cases, a shiny new president seems to be the champion we were looking for. Most of those who have risen to the highest elected office in the land did so because they possessed a driving vision, a history of successful executive or legislative management, or obvious powers of persuasion, and were able to demonstrate those superpowers to an entire nation. Television, with its urgency and its red, white, and blue backgrounds, enhances the aura of strength and victory.

But it is all a façade. Whatever skills these presidents have in managing large bureaucratic hierarchies or speaking publicly on topics of national concern, they are fallible, imperfect, broken. Whether you believe in original sin or not, it’s clear that humans can’t maintain the image of perfection for very long. Something always goes wrong, and when it goes wrong with a hero, it can be demoralizing to the hero worshipers.

America’s founders understood the importance of having a president rather than a hero. The framers of the Constitution knew that they must enforce limits and checks on the power of the executive office, even when held by someone as collectively respected and honored as George Washington—especially because it would be held by a hero like Washington.

In our image-centric culture, we tend to extend one heroic act to the entire life of a person. But this is a mistake. People will disappoint, sometimes at the worst possible moment. That’s why we need clearly defined limits and boundaries on the power of the political branches. When we shrug off NSA-initiated privacy concerns or IRS abuses, we do so because we look to the heroism of the Oval Office. We should instead look to the humanity of the person in it.

July 1, 2013

The Ninety-Five Percent Rule

It’s been a tough few weeks for race relations. The news media issues hourly reports from the trial of George Zimmerman, a Hispanic man, for his shooting of a black youth, Trayvon Martin. Paula Deen stepped away from some important butter-and-mayonnaise recipes to defend herself against the use of the “N” word and other racially demeaning remarks. And New York mayor Michael Bloomberg made headlines with a comment about how police stops of the city’s citizens should focus more on minorities.

For those who see in American society the racist foundation on which the country was built, these recent events should come a breath of fresh air. The day has arrived when the stupid old racist white men who dominate this nation are finally being exposed for the wretches they are, and the veil that hides their slavery-loving activities is being drawn back to reveal the true nature of this country.

What a crock of white racist bird droppings.

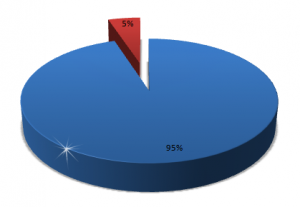

America—the post-Civil Rights Act America that I grew up in—is not racist. The nation has moved on from its Jim Crow days, and racial harmony and integration are the new normal. If you doubt what I’m saying, well, you are in the minority, part of a tiny cadre of people who can’t let go of their anger at the wrongs committed by people who died more than a century ago. For the rest of us, the Ninety-Five Percent Rule applies: ninety-five percent of the people exist and act in culturally normal ways ninety-five percent of the time.

I’m not saying that there aren’t any racists in America. Certainly there are some idiots who still judge people by the color of their skin instead of by Dr. King’s character-content standard. But these Neanderthals are in the minority, a paltry five percent according to the rule, and hopefully much less. I’m also not saying that the ninety-five percent is automatically holy and righteous. Sometimes “culturally normal” is tainted, as in the Deep South of the early nineteenth century, when even non-slaveholders derided their African-born brethren.

Despite these qualifications, the Ninety-Five Percent Rule is good news for those who bite their nails each time a news story reports how some famous chef or whatnot lets loose with a racial slur. Is Paula Dean one of the five percent, or is she part of the majority who slipped into one of those dark five-percent-of-the-time events? I don’t know enough details of her or the news story to answer that, but whichever it is, it has no impact on the ninety-five percent who live their lives never giving racial concerns a second thought.

The news media loves the five percent. Extreme statements are the stuff of which ad sales are made. Because of this exposure, some news consumers and commentators mistakenly believe that the sins of the five percent are a reflection of the overall population. The five percent can be noisy and troublesome, engaging in behaviors that sometimes warrant government intervention. But as long as they are recognized for the weak and tiny minority that they are, they will remain harmless.

Depending on the topic—racism, homophobia, poverty, employment, voting, or whatever—the exact number might range between ninety and ninety-nine percent, and outside influences, including natural disasters or government intrusion, may skew the numbers for a time. But anyone who tells you that vast populations within American society—races, genders, political parties, and so on—are racist or otherwise evil in significant numbers does so to dull the pain of their own place outside the ninety-five percent.

June 17, 2013

Review of Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy

Theologians who make an impact on society don’t really exist anymore. If you were forced to name any that were significant, you might need to reach back to the days of Augustine or Thomas Aquinas. But in our modern era there lived a theologian who had an impact, not just on church thought, but also on an entire nation. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the eponymous star of Eric Metaxas’ 2010 biography, impacted modern Germany both through his exegetical prowess and because of his willingness to assassinate Adolf Hitler.

Bonhoeffer relates the complete biography of the modern church reformer, from his birth in 1906, to his execution on the gallows at one of Nazi Germany’s most notorious concentration camps. And when I say complete, I really mean “complete.” The book is detailed to the point of irritation, right down to identifying the time of day that his parents left their hotel to see the college-aged Dietrich off at the docks for his first trip to America. (8:30am local time, in case you were interested.) This exhaustive coverage seems unnecessary, especially for Bonhoeffer’s younger days. But it does given important insights into a man who was transformed in parallel with his nation.

Germany between the wars was a mess. Gone was the glorious empire of Wilhelm II and Otto von Bismarck; the Treaty of Versailles made sure of that. In this time of financial collapse and national embarrassment, Hitler rose with the promise of a new, powerful Fatherland based on the superiority of the Aryan peoples, the scapegoating of the Jews and the Communists, and—most important from Bonhoeffer’s perspective—the acquiescence a church that had redefined God as a local, manageable deity. Bonhoeffer insisted instead that the Christian church was universal. God didn’t belong to Germany; Germany belonged to God—at His instigation—as did Rome and even the Jews, an idea that the state church was soon legally required to reject.

The book follows both Bonhoeffer’s and Hitler’s progression from bit players to major forces on a world stage. Bonhoeffer was not the yang for Hitler’s yin, but he was as Type-A as the Führer, and his actions delayed the complete domination of all German Christendom for a while. Yet Hitler had the power of the state, and as his plans for the extermination of both the Jews and the weak became evident, Bonhoeffer realized that obedience to God meant getting your hands dirty, “sinning boldly” in the Lutheran vernacular. In his case, dirty hands meant pretending to be a Nazi intelligence agent, engaging in traitorous communications with associates of Churchill and the Allies, and plotting the murder of Hitler.

Bonhoeffer helped perpetrate Operation Flash, a plot to blow up Hitler’s plane. A faulty detonator foiled that plan, and when Hitler survived the July 1944 “Valkyrie” briefcase bomb assassination attempt, Bonhoeffer was identified, arrested, and imprisoned as one of the conspirators. The last years leading up to his execution play out like a suspense movie, with his near escape and eventual hanging on Hitler’s personal directive carried out just two weeks before American troops liberated the death camp, and three weeks before Hitler’s own suicide.

Bonhoeffer is more than a biography. It’s also a call to worship, something that can’t be avoided given the lengthy excerpts from Bonhoeffer’s books and letters. Metaxas is clearly enamored with the church leader, especially in the first quarter of the book where, frankly, not much of interest has yet happened in Bonhoeffer’s short life. But this fan-boy approach gives the text a rich depth that a mere documentarian might miss. And his presentation of Nazi Germany from the perspective of the breakaway Confessional Church provides details only briefly touched on in William Shirer’s otherwise comprehensive Rise and Fall of the Third Reich.

Despite his strong ethics, Bonhoeffer was willing to pursue the destruction of Hitler because he foresaw a Germany ruined and millions killed by the evils of the Third Reich. Hitler outlived the theologian, but Bonhoeffer would not have seen this as a failure. He knew that God sought not success, but obedience from his followers. “One must completely abandon any attempt to make something of oneself, whether it be a saint, or a converted sinner, or a churchman.” As Metaxas communicates quite well, in giving up his own success in obedience to his God, Bonhoeffer managed to succeed far beyond Germany’s maniacal dictator.

June 10, 2013

There’s a Government Spy App for That

It’s been a tough few weeks for the Obama administration, and a tough few weeks for you as well if you’ve ever made a phone call, sent an email, or filed your taxes. Fresh on the heels of reports that the IRS overstepped its authority in investigating certain political groups, news broke last week that the National Security Agency had ordered Verizon to turn over information on every domestic and international call placed through its network. This means that every phone call you made to anyone living in a Verizon coverage area was included in an ongoing investigation, even if you were not part of a suspect Tea Party group.

The NSA-Verizon surveillance order is part of the larger PRISM program, an intelligence system that went online in 2007, with similar efforts going back to the start of anti-terror activities after the September 2011 attacks. News of the program, while shocking, is just one of many uncomfortable disagreements between American citizens and the government that seeks to protect them from harm.

I’m glad that the IRS has standards that determine which groups should receive an exemption from taxation. I’m also heartened to know that there are agencies that take seriously the need to prevent baddies from bringing mayhem and harm to the American populace. But in these two instances, what the government did was indecent.

In light of our constitutional freedoms, it is morally wrong for the IRS to single out groups for added scrutiny simply because they espouse strong opinions on federal fiscal policies. It is ethically offensive for the NSA to collect private data on ordinary citizens without due process or reasonable suspicions of guilt. We know these things are wrong. Raised on a steady diet of First Amendment freedoms and unalienable rights that no government deserves to take away, Americans have been trained to instinctively recognize violations of our liberties. Yet here we are, reading about decisions by American leaders that violate American rights here on American soil.

Some claim that these encroachments on freedom are needed for security reasons. An anonymous senior intelligence officer credited the PRISM program with preventing a 2009 New York City subway bombing, a claim later disputed by court records. So we have a program scouring phone records of everyone in the United States for who knows how long, and the only confirmed benefit is in providing ancillary support in tracking down an already-known terror suspect. I think “overkill” is the word I’m looking for.

Safety is an important consideration in federal actions, but it has to be balanced by freedoms and common sense. We could prevent 3,500 accidental drowning deaths in the United States every year by filling every swimming pool with cement. Even better, we could eliminate the tens of thousands of annual traffic fatalities by locking everyone in their homes. Such actions are naturally repugnant, and we know they are wrong without even having to think about them.

Why do the IRS and NSA violate both the letter and the spirit of the constitution by taking actions that are in clear confrontation to our established freedoms? What pushes elected officials and other bureaucrats to enact morally reprehensible policies that treat every single citizen as a suspected felon? Money. It’s all about money.

Let’s say it was you, instead of an 84-year-old Florida woman, who had won the recent $590 million Powerball lottery. It’s a lot of money, and I bet you’d test out a few reckless activities or investments that you wouldn’t dare try on a standard middle-class salary. It’s the same with government. With access to nearly unlimited funds through taxation and deficit spending, the federal government has the resources to try out things it couldn’t do with more frugal means. And if things go wrong, it simply dips its hand back into that same money pool and tries something else. When there’s virtually no limit on what you can try, it’s pretty easy to toss aside pesky things like moral obligations.

Take a government that has easy access to deep pockets, combine it with a lack of authority figures who will say “no” to questionable decisions, and you have an environment that is ripe for the abuse of power. The American public has both the authority and the obligation to hold leaders accountable for their public actions. If we instead defer all responsibility to leaders with suspect morals and ample ready cash, we shouldn’t be surprised to find ourselves at the wrong end of a monitored phone call.

June 3, 2013

Rock Paper Scissors Marriage

Besides being a gateway to same-sex divorce, gay marriage is turning out to be the abortion-debate-drama of the twenty-first century. Although such unions directly benefit only a small percentage of the population, advocates have pushed same-sex marriage to the front of the political action queue, with nearly a dozen states now sanctioning the practice. Still, the decisions by these states are meaningless unless the owners of marriage follow along.

The three “owners” of marriage are the church, the wider culture, and government, or as I like to call them: rock, paper, scissors. Religion, of course, is the institution most closely associated with matrimony. All of the world’s major faiths establish marital standards, with some slight variations by region. Christianity, America’s favorite religion, views marriage as instituted by God, with Jesus himself identifying it as something “God has joined together.” Religions own marriage, and anyone who expresses shock when a church balks at deviations to its established religious practices isn’t taking that ownership seriously.

Even when a nation has a strong religious community, the culture takes partial ownership of marriage. Traditions such as throwing the bouquet and kissing the bride are de rigueur, and not easily changed. I should know. We let someone talk us into replacing Here Comes the Bride at our wedding with some other upbeat march, and decades later I’m still regretting it.

And then there’s Uncle Sam, the third partner in this joint ownership of wedded bliss, at least in this country. Stable marriages are a breeding ground—no pun intended—for raising the next generation of orderly, obedient, and culturally normalized middle-class taxpayers. By providing its official imprimatur to marriages and offering taxation benefits to lawfully wedded couples, the state helps keep itself safe and secure from societal discord.

If you want to alter the core of what marriage is, you have to get all three institutions to play along. Religion, it turns out, is the simplest place to start in our pluralistic society, but success can be difficult. Consider the early Mormons and their “plural marriages.” Joseph Smith and other top church leaders jumped right into the multiple-wives thing, and even today there may be as many as 10,000 Mormon fundamentalist adherents that still live in polygamous homes. The government and society—paper and scissors for those keeping track—didn’t agree with this plan, opting to pass laws and even take up arms to prevent the change in marriage norms.

In recent years, legislation and courts have been used to add new gender combinations to the definition of marriage. The appeal to rights, while an interesting argument, is simplistic, since it assumes that the government—the enforcer of rights in society—is the only owner of marriage. It’s not. The core understanding of marriage in the United States can never change unless all three owners consent.

The current trend seems to be moving toward widespread acceptance of same-sex unions. If critics of gay marriage have any hope of maintaining the status quo, they will need to keep one—and probably two at this point—marriage owners on board. Those on both sides can scream all they want about rights and tradition, but once all three owners reach a tipping point in favor of marriage redefinition—for better or for worse—the change will occur.

[Image credits: Artist "r8r" on toolpool.com]

May 27, 2013

The Retirement Gamble

In the PBS Frontline episode “The Retirement Gamble,” broadcast on PBS stations on April 26, 2013, episode writers Marcela Gaviria and Martin Smith present scenes of misery and woe in the American retirement landscape. Baby boomers are unprepared for the financial realities of their post-employment years, the show says, and those of the younger generation won’t fare much better thanks to a lack of investment knowledge by the typical worker, complex investment options, rampant fees by financial services companies, and a Congress bribed to inaction by industry lobbyists.

It’s scary stuff. Scary and false. The part about investments being complex is certainly true. But it doesn’t take much research to come to that conclusion. It’s the other parts of the program, the portions that require actual journalism, that are filled with distortions. Narrator Martin Smith paints a picture of financial fear and desperation, but the paint he uses is tinted with distracting anecdotal evidence and outright untruths.

A good example is when the program discusses fees charged by companies that help consumers invest their retirement funds. Depending on the investment, fees typically range from about 0.5 percent to as much as five percent per year, with the average cost at around 1.3 percent, according to the program. Smith provides an illustration to show how companies are gouging customers with outrageous costs, an example proposed by John Bogle, former CEO of The Vanguard Group.

Assume you’re invested in a fund that is earning a gross annual return of seven percent. They charge you a two percent annual fee. Over fifty years, the difference between your net of five percent and what you would have made without fees is staggering. Bogle says you’ve lost almost two thirds of what you would have had.

Two-thirds sounds like a lot, and being a reporter, Smith seeks confirmation from Michael Falcon, a retirement executive with J.P. Morgan Asset Management, who calls Bogle’s numbers into question. But Smith is persistent, and whips out his handy calculator to confirm that on a $100,000 investment, a two-percent annual fee would, after fifty years, leave the poor investor with only about $36,000. The company that is supposed to invest and protect this hypothetical person’s retirement has absconded with the other $64,000.

It’s here where Smith (and Bogle, the supposed expert) is either lying outright, or is just inept at math. He forgot the most important part of the investment calculation: the return on the investment. In this case, he didn’t bother including the seven percent return. If you run the numbers correctly, the consumer is not left with a measly $36,000 after fifty years, but with a little over $1 million, even with no further contributions to the account. The fees not included in this total do amount to over $400,000—still a shocking twenty-eight percent or so of the total account potential—but nowhere near the two-thirds suggested by the report. The typical consumer actually ends up paying much less in fees—Smith confesses later—$155,000 on average over their lifetimes.

The investigation also plays up the trauma associated with ordinary people needing to make plans for their future without a pension-providing company doing all the work for them. The program shows Mark Featherston, an typical working American with a company-supplied retirement plan, fretting over his options. “They showed you the plan. You either had your choices between an aggressive investment, moderate, or conservative. You know, there was nobody there managing my money. It was all up to me.” Another one of the sixty million Americans with a 401(k), Debbie Skocyznski, mirrors the fear: “I had no idea. I was so confused. I came out of that meeting, and I was, like, ‘Oh, my God.’ It was just— it was overwhelming for me, the knowledge that you had to have in order to invest.”

As with many money-centric documentaries, the program includes the obligatory nods to Enron and to the anger over Wall Street investors collecting billions of dollars in bonuses. But overall the focus stays fixed on the supposed suffering caused by having a 401(k) account. While calling retirement planning “a bewildering and frightening challenge for millions of Americans,” the report doesn’t bother delving into the true difficulties of saving for the future—information everyone could use from a public television program. Instead, it celebrates the dumbing down of the nation, and yearns for a risk-free environment where ordinary people are liberated from important financial decisions, or even the need to ask questions about their own money.

Retirement planning isn’t easy. As the Frontline voiceover reminds us, “Half of all Americans say they can’t afford to save for retirement. One third have next to no retirement savings at all.” Medical emergencies, the high cost of education, and the on-going recession do represent difficult obstacles to saving, especially for those most in need of long-term financial stability. But we used to be an agrarian society where people worked well past their prime, dying with their hands still at the plow. This modern world, with all its conveniences and toys, has deceived us into thinking that retirement is our right, that we deserve ease, free from the burden of having to care for ourselves. When we leave the hard thinking to others, we run the risk of having documentaries like “The Retirement Gamble” dupe us into seeing misery where opportunity actually exist, and blaming others for the problems that stem from our own inaction.

To watch the episode for yourself, visit the Frontline web page for “The Retirement Gamble.” A full transcript of the program is also available.

[Image credits: PBS / Frontline]

May 20, 2013

Military-Industrial Distraction

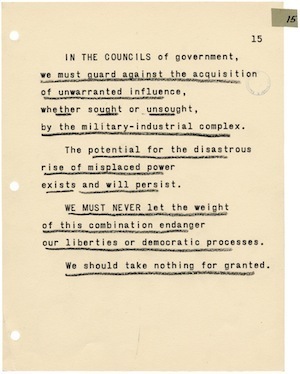

During his 1961 presidential farewell address, Dwight Eisenhower warned the American people to beware of the “military-industrial complex,” the close relationship forged between the nation’s armed forces with their munitions requirements, the policymakers and legislators who manage the political and financial aspects of the military, and the private businesses that supply weapons and related tools and services. The specific caution came about halfway through the televised speech.

This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence—economic, political, even spiritual—is felt in every city, every statehouse, every office of the federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society. In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists, and will persist.

It’s wise counsel, coming as it does from someone who not only fought in the theater of war over several decades, but who acted as Commander in Chief during a time of growing Communist tensions in Europe and Asia. Five decades later, our military might is scattered across the globe and engaged in regular skirmishes. There are strong voices everywhere trying to invoke the spirit of Ike’s words, demanding that the United States reduce its military stance and give peace a fighting chance. They’ve missed the point.

As Supreme Command of the Allied Forces during World War II, Eisenhower understood that there was a time for war and a time for peace. His caution was not about guns and soldiers, although it’s understandable that some may think so. “Military-industrial complex” does begin with a word of war, to be sure. But “military” is not the key term; instead, it’s “complex.” The post-war president warned of a “conjunction” between an arms industry and a military establishment, making possible the “acquisition of unwarranted influence” by both government agencies and private industry.

Recent events have put the fear of guns back into the hearts of Americans, but what they should dread more—the thing that does even greater societal harm that gun violence—is the intricate entanglement of government and industry in all sectors of the economy, not just weaponry. Whether it’s the healthcare-industrial complex, the agriculture-industrial complex, or the Internet-industrial complex, anytime you tie government and private businesses together, provide them with the financial resources that come with mandatory taxation, and shield their activities with industry-specific regulations, regulation waivers, and tax breaks, you create yet one more seat of power of the type that Eisenhower feared more than Nazi Germany.

There is a place for public-private partnerships, especially at the county and municipal level. But anytime that association rises to the state and federal realms, there is always the risk that the “total influence—economic, political, even spiritual,” associated with the joint venture will prove too tempting for everyone involved.

Image Credits: Farewell address by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, January 17, 1961; Final TV Talk 1/17/61 (Page 15), Box 38, Speech Series, Papers of Dwight D. Eisenhower as President, 1953-61, Eisenhower Library; National Archives and Records Administration.