Chris Chelser's Blog, page 16

March 9, 2016

Short Story: “The Hare and the Rose”

The Hare And The Rose

On a stalk in a rose bush, a silky red bud was about to bloom when along came a curious hare.

The hare sniffed the sweet perfume between the unfolding petals.

“You smell wonderful,” said the hare as it nuzzled the bud. “And you are so soft.”

“Watch how you go,” the rose warned. “I may be scented and soft, but I have weapons to defend myself if you harm me.”

“Why would I harm you?” asked the hare. “Are you that tasty?”

“Stay away or I will draw blood!” spat the rose.

The hare regarded the rose and its stalk more closely.

“Those thorns are your weapons?” it scoffed. “Sharp they may be, but they are no match for the edge of my teeth,” and with its big, chisel-like incisors, it chopped off blossom and stalk, and ate them.

The hare was best pleased with this unexpected meal. The bud was delicious, the victory sweet.

But when the hare swallowed, a small thorn stuck in its throat. A single cough and out came the blood, dark and glistening, like the petals of the rose had been.

So it came to pass that the broken stalk of the suspicious rose and the bloodied corpse of the prideful hare withered away side by side, until nothing remained of either.

The End

March 6, 2016

All “Cabin in the Woods”-references and…

This great video not only breaks down the long list of references to horror movies in the spoof/hommage horror film Cabin in the Woods, but it also puts the finger on exactly what is missing in horror stories these days.

Enjoy!

[Warning: this vid is best when you have seen the movie! If you haven't, go grab a copy or watch it on Netflix.]

March 4, 2016

March 1, 2016

Writer’s Woes: “Who am I writing for?”

Once a month I permit myself to discuss the dark side of being a (self-published) author. In this month’s post rants about…

“Who am I writing for?”

When it comes to this question, fiction writers are caught in a three-way split: the market, the readers, and themselves.

The market

This is the publishers, agents, editors, best-seller lists and booksellers, and all they care about in a book is marketability: “Can I sell this, and can I make money from it?” A book may be the pinnacle of good writing, but if the subject doesn’t appeal to a large enough audience, it’s a bad book.

The market is also keen on anything measurable: minimum word count, maximum word count, genre limits, and the number of ‘what is hot’ sales points. It’s a checklist. Measuring things is a virtue in a business model, but when it comes to stories, those benchmarks curb and even kill good stories.

“That subplot really gives the main character depth, but the story is 10k over the max word limit, so cut the subplot or we’re not accepting it.” “The story may be better off with a bitter ending, but bitter endings don’t sell, so… rewrite or be rejected.”

It’s true. I have read a trilogy where the plot evolves to an inevitable dark resolution, until an unforeseen twist forces a sappy ‘nothing hurts’ end. And people buy that? Well, yes, they do. That is the whole point, apparently.

The readers

So having navigated the shoals of market demands, a writer must also acknowledge his/her fan base, if they are lucky enough to have one, or else their potential readers. What are their expectations of the genre? Of your work as a writer? What do they want to read, since that is not always the same as what the publishers think will sell? Readers are individuals, not a demographic designation. Individuals grow, change, develop. They do not always want the same old thing time and time again. But what do they want?

A writer can try to anticipate on the answer to that question, but writers are not mind readers, so they will always be second guessing. Sometimes they will hit the spot, sometimes their guess will be miles off. The first option leads to praise and hopefully more readers, whereas the second option leads to scorn and likely means losing readers.

Seasoned writers can make an educated guess based on reader input like polls, reviews and fan letters. But readers are fundamentally readers. Not writers. Even if they love your books, only very few will leave a review. The other 99% remains silent, so deciphering what your readers want still remains a shot in the dark.

The writer themselves

After trying and inevitably failing to cater to the reader wishes, and after being forced into format writing by the market’s demands, many a writer wonders why they ever wanted to be published. They loved writing when they wrote the stories they wanted to write, and when they decided how a plot developed rather than juggling genre conventions.

Because writing is more than just planting letters on paper. Writing is about asking questions and finding answers, sometimes without knowing what the question was. If a writer is merely churning out words to please others, they ignore that which was their original incentive to write: their own need to tell a story.

Juggling?

Keeping all three goals in mind while I write is like a continuous juggling game. Every writing decision that slides into place at one end must be checked against a fit with the other two. No fit? More juggling, more shifting, more nudging until it is a three-way match.

Ideally, that is.

I can’t manage a three-way fit. I can make my stab in the dark to what people might like, and I know what I want to write and the stories I want to tell, but to squeeze that into the straightjacket of market format? No.

Deliberate misfit

Maybe I don’t want it to work. I have a deep resentment for decisions that sacrifice storytelling on the altar of marketability. Yes, I want to make a living of my writing, but I will not sell my soul for sales. For me, the stories come first. If that means self-publishing because my books do not ‘fit’ market demands of the genre, I will gladly go the extra mile to market my work and connect to my (potential) readers myself.

Of course I will need to find those potential readers first. But that is a rant for another time.

The Insecure Writer’s Support Group

A safe haven for insecure writers of all kinds!

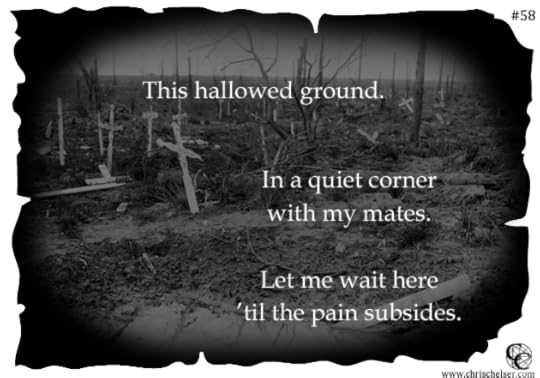

War Stories

Today I spent preparing a presentation I will be giving at my son’s school next week. If this was university, they’d call it a guest lecture, but since this is primary school, it’s just a mom coming over to tell stories for an hour.

Stories about normal people surviving World War II.

I was fortunate to have grandparents who were comfortable talking about their experiences during the war. Nothing horrifically traumatic, but being bombed or getting shot at by a fighter plane while cycling down a countryside road are scary and tense indeed!

So next week Monday I get to tell two dozen 9-year-olds about surviving bullets, forced labour, and a harsh winter with no heat, no light and no food:

My grandparents survived the Hunger Winter; the cat wasn’t that lucky. But thousands of people didn’t have a cat to fall back on…

Maybe I will write down some of their stories and post them here. To keep the memories alive.

February 25, 2016

Why discussing tragedy and death with children is essential

Parents should protect their children, but sometimes the best way to protect them from pain is by exploring stories of pain and hardship together.

When another tragedy hits the news and children catch on to it, too many adults will go out of their way to change the subject or gloss over what happened. This sends entirely the wrong message.

Children see and hear more than they are often given credit for. Even young children can sense tension in the adults around them and know that something is wrong. But without a context, they cannot understand why other people respond to news by getting angry or crying. Worse still: without context, children cannot understand what a tragic event means, and so they cannot learn to develop their own feelings, thoughts and response to such events.

If parents are not willing to provide that context, then children will try to find answers themselves. Without help, without guidance, that can be a truly traumatic experience for them. Once that happens, brushing off the subject as “that’s not for kids” only does more harm.

So, talk with them.

Talking with a child about pain, loss and tragedy when they are confronted with it gives a child confidence. Confidence that it is okay to feel sad or scared by what happened, and that other people feel the same way.

And, more importantly, discussing such subjects will give them the confidence that if they ever feel lost or scared, they can turn to their parents for comfort and understanding.

That confidence is the essence of safety to a child. This safety is much stronger than the false security created by avoiding unsettling subjects or pretending that they need not worry about it. Because they do worry.

Kids already know that bad things happen. What they need is to learn how to deal with the emotions that evokes. That will help them become more secure and more mentally stable throughout their lives.

Written in response to The Washington Post article “Why I let my children read books about upsetting things” by Suzanne Nelson.

February 23, 2016

Ask the Author: “Why dark fiction?”

Every last week of the month, I’m answering readers’ questions.

Want to ask me something? Click here.

“Why do you write dark fiction?”

To my own surprise, I had to think long and hard about a proper answer to this one.

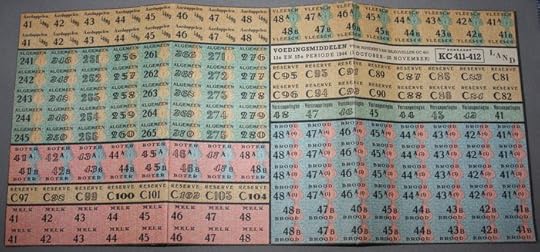

For as long as I can remember – which is all the way back before kindergarten – I have preferred weird and dramatic tales. However, looking back I suppose the graphic novels of the Belgian artist Eric lay at the root of that love. His fantastic, unsettling stories and at times surrealistic art first caught my attention at the tender age of six, and they have stayed with me ever since.

I wasn’t supposed to read them, of course, but I stumbled on them while sifting through my aunt’s bookcase in search of comics I knew. Then I saw Eric’s Tetfol [French: fool] and for some reason, it struck me. Maybe it was the wolf on the cover or simply a child’s curiosty, but I began to read.

Cover of the first Tetfol story.

Eric (Frédéric Delzant), 1981

As with many comics of the 1970s and ‘80s, the artwork was neither gruesome nor horrific by modern standards, but I was six. All I had known until then were sanctioned children’s books about cute animals. And in this comic, there was a human corpse on the very first page!

But in the end, it was the werewolf in that story which changed everything. Young and impressionable as I was, that creature etched itself into my mind. It haunted me well into adolescence, but it also gave me a glimpse of the reality that grown/ups often hide from children.

From a very young age, I had been aware of death and mortality. There was no particular cause or reason, but I understood instinctively that life isn’t always fair. Bad things did happen to good people and the world wasn’t always accommodating. By extension, I never considered myself immune to grief or loss. Such was life, nothing more.

Yet the children’s stories I grew up with were all innocence and smiles and imposed happiness. Death happened rarely, if at all, and the greatest adversity in life was not being able to play outside because it was raining…

It felt wrong. I didn’t know why or how, but those stories were wrong. Fake. They told lies. Pleasant lies, but lies nonetheless. Only I didn’t have the vocabulary to express that sentiment.

Discovering those dark graphic novels was my first encounter with another kind of story. Stories that had washed off the bright colours and shallow emotions to expose the dark reality I had always sensed lurking beneath my childish world.

Oh yes, the werewolf terrified little-six-year-old me, but at the same time, I was enthralled. Were it not for that chance encounter, I might never have fallen in love with dark fiction and horror stories.

In fact, without that werewolf, I might never have taken to writing stories of my own at all.

Have a question of you own? Click here.

February 22, 2016

Paris Catacombs: Them dry old bones

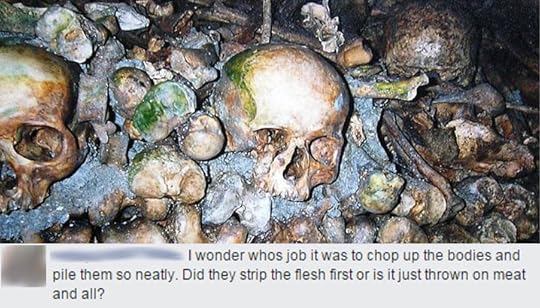

The other day I found this comment on a Facebook post about the Paris Catacombs:

Hilariously gruesome as this person’s wild imagination was, it did inspire me to revisit the background research I had done prior to my last trip to Paris. Much as I wanted to visit the famous ossuary, I never got the chance to actually go inside, but pouring over the many photos floating about the Internet provides a teeny bit of consolation.

So who did chop up the bodies to be put in these tunnels?

The answer is: no one. When those bones were stacked in the vaults beneath the city, time and decay had already stripped them of their flesh.

Photo (c) Richard Büttner: http://www.munichphotos.com/

But then who hacks a vast network of tunnels, just to store bones?

Again the answer is: no one. If anything, the ossuary was created when a dire need was resolved by putting an equally dire inconvenience to good use.

That dire need became apparent in the year 1780, when the owner of a building near the Parisian cemetery Les Innocents had the shock of his life: the wall of his basement collapsed and numerous decaying corpses tumbled into his cellar! Zombies? No, explanation was far simpler. On the other side of the cemetery wall was a mass grave, and brick and mortar had been knocked down by the sheer weight of the bodies buried there.

Paris of the 18th-century was large, but unplanned. The wide boulevards it is known for today did not exist yet. Instead, the whole city was a maze of streets and alleys. The population grew faster than the city boundaries, and so people crowded together in tightly packed houses. The quartiers (neighbourhoods) were littered with chapels and churches and countless cemeteries. Because where people live, people die. And where many people live, many people die. At Les Innocents, which had been in use for 600 years, more than 2 million bodies lay buried!

So it was no real surprise that by the late 18th century, the graveyards of Paris were literally overflowing with corpses.

In an effort to solve this mounting problem, it was decreed that the old cemeteries would be cleared, and that all further burials were to be contained to three new cemeteries located at what was then the outskirts of the city. Arguably the most famous of those three is Pere Lachaise (and it is enormous!).

But what to do with the remains were exhumed?

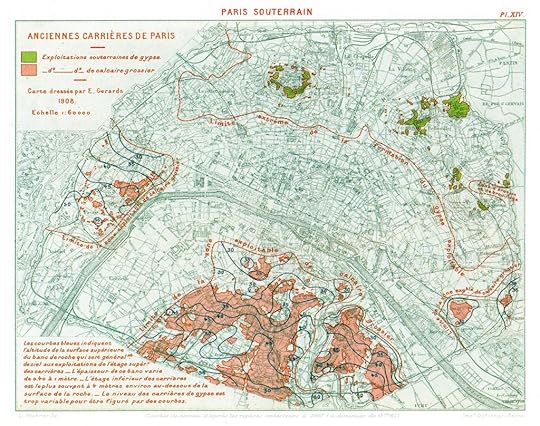

As it happened, a few years before that mass grave spilled into the adjacent cellar, the continuing growth of the city had exposed another problem: cave-ins.

Back in the Middle Ages, there had been many limestone mines outside the town’s perimeters. A considerable number of these had been illicit and were therefore never charted. People simply dug into the ground, tunnelled where they could, and abandoned the makeshift mines when they were depleted. The result was an largely unknown network of unsupported underground tunnels.

Map of Paris. Red and green patches show where limestone and gipsum was quarried. The Catacombs are in the middle of the largest red blob.

Plan: Émile Gérards (1859–1920) BnF Notice d’autorité personne. Digital copy: ThePromenader – Own work, Public Domain

Those tunnels weren’t bothering anyone, until the expansion of Paris began to include this undermined terrain. Sinkholes formed, houses collapsed: a highly unpleasant and unsafe situation. The city ordered police prefect Lenoir to oversee the renovation of those tunnels to prevent further damage to properties above ground.

These renovations were well underway when Lenoir was also charged with overseeing the exhumation of the old cemeteries. The police prefect must’ve been a pragmatic man, because it was he who suggested that the unearthed bones should be laid to rest in these otherwise useless tunnels.

This suggestion was made law, and moving the ancient remains could begin.

It took more than two years of nightly processions to clear the majority of the old cemeteries. Millions of bodies were brought to the renovated and blessed tunnels, where they were stored rather haphazardly. Then the French Revolution began, and it took another 25 years before anyone began to organise the ossuary into a proper mausoleum. It has drawn curious visitors since.

Today, a tour of the Catacombs takes you along only 2 km of the underground tunnels. The complete network is said to be at least 300 km long, divided over infinite turns, corners and passages. Not a good place to get lost! Well, you cannot wander too far, since the ossuary is closed off from the rest of the network.

But then again, not all bones in those tunnels are 200 years old…

February 19, 2016

February 17, 2016

The Bare Bones of… Magic Tricks (wait, what?)

“Presto” (c) Pixar

What: Magic tricks. Yes, sleight of hand, card tricks, sawing women in half, that sort of thing. With references to the films The Usual Suspects (1995) and The Prestige (2006).

Why: Good storytellers have a lot in common with magicians, and watching magicians can teach us a lot about how stories work, as well as why they work.

Spoiler Alert: Low | Medium | HIGH!

For both movies and magic in general, all of which are enjoyed best when you know as little as possible.

Summary:

Recently my husband has taken a liking to watching youtube vids of professional stage magicians and illusionists. Not because he studies to become one (or if so, he hasn’t told me yet), but for the sheer sense of wonder, curiosity and rewinding to try and work out how they did it. And yours truly loves to join him in the puzzle.

A brief disclaimer: neither of us claims to actually know how the tricks we see are done. When a guy in a big parka makes white doves appear in his hands, odds are that those birds were hidden in his coat. You can’t see him pulling them out, but since live doves do not ‘poof’ into existence, the possible explanations are limited.

That said, I have no idea how he, after he has put the birds in a big cage, then makes the cage disappear birds and all and have a scantily clad lady appear in its stead!

Actually, The Prestige gives a rather morbid explanation of how to disappear a cage containing one canary, but I don’t think that method would work as well on six doves. At least I hope not…

In The Prestige, two young magicians living in the late 19th century spiral into a deadly rivalry as they race one another to perform the ultimate disappearance-reappearance act with a human. Both make great sacrifices in their search, and both end up paying a horrible price for their success. However, the most important scene – both to the film’s plot and to this Bare Bones’ subject – is the following:

When the two magicians are still on friendly terms, they go to see an old Chinese magician performing. On stage, this small, crooked old man in traditional Chinese robes makes a bowl full of water disappear at one end of the stage. He then waggles, as he does, to the other end of the stage, where he reappears the bowl of water. The only explanation, one of the young magicians argues with his friend, is that the old man carried the heavy bowl across the stage between his knees.

“But it is an old man,” the other counters as they watch the old Chinese guy waggle slowly out of the theatre and into a coach. “He is never strong enough to do that.”

“He is. He just gives the impression of being weak and makes us believe that. The feeble waggle is an act. But for such an illusion to work, you have to keep up the act outside the theatre as well!”

And this is exactly what the character Verbal Kint does in The Usual Suspects.

Kint is the only survivor of a band of five criminals after what the police believe is a drugs raid gone bad. Kint is also bald, emotional and both his left hand and left foot are crippled, causing him to walk with a distinct limp. By all appearances, he is the runt of the gang, only alive because the rest of his mates didn’t trust him with any important tasks during the raid.

All through his questioning by the police and the visuals of the story he tells, both the audience and the police only ever see him like that. Only at the very end, when the police have let him go and Kint limps off down the street, does the camera focus on his crooked foot straightening out and the so far useless hand being flexed. The man’s whole stance changes, and the audience realises – moments before the police receive a facial sketch confirming the audience’s suspicion – that not only is Kint the mastermind behind the raid (which was not about drugs, but about revenge), he is also the elusive master criminal known as Keyser Soze.

Kint ‘lived the act’. By posing as someone who would be physically and mentally incapable of doing the things he did, no one ever suspected him of being a crime lord. He fooled everyone on both sides of the silver screen.

Story Skeleton:

A good magician can subtly divert his audience’s attention, so they don’t notice what he is doing. His actions happen faster than expected or they happen elsewhere or at an unexpected moment. As a result, the moment when the proverbial or literal rabbit is pulled out of the hat, the audience is surprised and confounded.

A good storyteller can subtly drop a phrase, a reference, a hint, without drawing the reader’s attention to it. It fits the narrative or dialogue and seems unremarkable, being neither important nor suspiciously unimportant. Until later in the story. Then this little titbit turns out to be important after all and twists the plot with the impact of a ten-ton explosive.

But where a magician must only convince the audience that he has truly sawed his assistant in half, a storyteller must convince not only the reader, but the story’s cast as well!

The writer knows the trick – the plot device – because she devised it. But she must present the plot device in such a way that it is convincing, yet doesn’t give away too much. This is the performance.

The characters partake in that performance, but what each character knows and understands of it depends on how they interpret the performance. It is the writer’s job to see to it that all characters respond to the plot device according to their individual knowledge and understanding.

Finally, plot device, performance and character responses must come together as a whole to convince the reader of that which the writer wants him to be convinced. Which may or may not be ambiguous: remember how J.K. Rowling had her readers second-guessing Professor Snape’s loyalties for seven books? Now that is an amazing performance of cups-and-balls!

Lesson learnt:

A good story contains plot developments that gives the reader the same feeling of astonishment as a well-performed card trick. That comparison is not accidental: storytelling and stage magic have a great deal in common.

The trick of storytelling is how to make your audience think what you want them to when you want them to. This is exactly what magicians do. Understanding the basics of stage magic can help storytellers give their stories that little pinch of fairy dust!