Chris Chelser's Blog, page 15

March 27, 2016

War Stories #3

“War Stories” is a series of my family’s personal experiences during World War II. Originally collected for and presented to my son’s class of 9-year-olds, this is where I share the non-sanitised versions.

Winter is coming!

In August 1944, my grandfather Jo was given a doctor’s statement that he should stay in the Netherlands, rather than be send back to perform forced labour in Germany.

In September 1944, the Allied forces liberated the southern provinces of the Netherlands. They marched to Nijmegen and wanted to cross the river Rhine into Arnhem. That proved “a bridge too far”. The Germans held their positions, and the people living in the northern parts of the Netherlands were cut off.

Those of us used to modern luxuries such as insulated houses, double glazing, central heating, hot water and electricity in abundance can barely imagine what it must have been like: by late October, there was a shortage of food, coal, and gas for lightning and heating. By December, winter had hit hard. By February, the situation was desperate.

My grandfather Jo and his wife Wil lived in Amsterdam at the time, sharing a flat with his parents. Together, they did what they could to keep the family alive.

No heating…

Gas had already run out, and soon what coal remained was confiscated for the army. Central heating didn’t exist yet, and without gas and coal, people could only burn wood to stay warm.

But firewood was not available, either. At least, not in the shops. Desperate for warmth, people took to the next best thing: felling the trees that lined the city streets.

The various city councils were – often pressured by the German officers in charge – not amused:

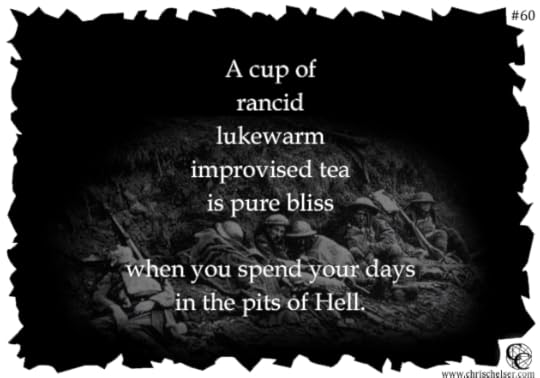

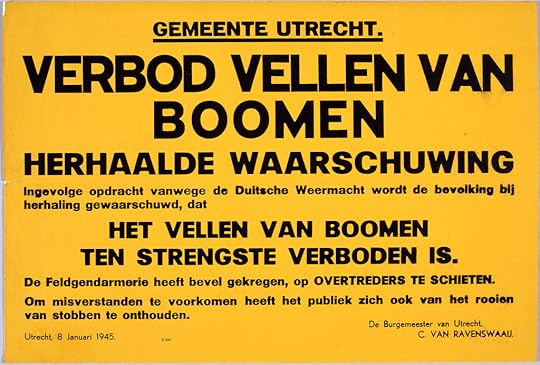

Notice prohibiting the felling of trees. “Trespassers will be shot by the police.”

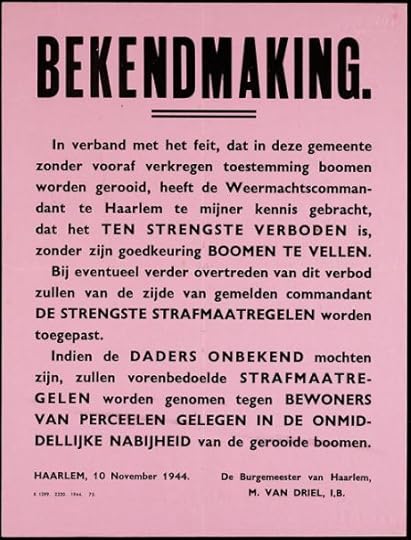

Similar notice from another city, declaring that “if the culprits remain unknown, the owners of the properties ajacent the felled trees will be punished in the most severe way [regardless of their culpability! - CC].”

Fortunately, not all cops were on the side of the occupants. Jo recalled that one day his father told the local policeman to take a night off: “That tree in the square? That’s going to come down tonight, but you will be elsewhere when my son and I chop it up.” Said policeman had no problem making himself scares for as long as they needed.

But trees were suspicious and not always in ample supply, especially in the cities.

In Amsterdam, Utrecht and various other cities had a network of tram rails for public transport.

In Amsterdam, Utrecht and various other cities had a network of tram rails for public transport.

Those rails were supported by small wooden beams, buried beneath the pavement.

In a desperate attempt to find wood to burn, people began to dig up the cobbles to remove those thin beams, just to have anything to keep warm that night.

However, Jo and his father had their mind set om something bigger: railway sleepers!

In those days, the railroad tracks were mounted on thick wooden beams (they use concrete ones now) that had been painted with creosote to keep them from rotting. For the younger readers: creosote is a poisonous chemical substance, now banned in most countries, that burns like a charm. In other words, those sleepers made for ideal firewood.

It was, however, also highly illegal to ‘harvest’ sleepers. Without those support beams, the railroad tracks would sink into the soil, causing trains to derail. So needless to say, both Dutch and German officials policed the tracks to prevent anyone stealing the sleepers.

Getting caught meant being arrested, which at that time of the war was synonymous with deportation to a camp.

Jo and his father went to the tracks twice. The first time, no one spotted them. The second time, they were not so lucky:

“We had just wrenched the wood from the tracks when we heard a patrol of the Grüne Polizei (German military police) approach. We dashed like mad behind the nearest bush and hid. Our bellies lay flat on the frozen ground as we waited, holding our breath and praying that they hadn’t seen us. We waited for agonizing minutes as the patrol came closer, closer, closer and… passed us by! They hadn’t seen us, or didn’t care. Either way, they didn’t check the tracks and they didn’t check the bushes. We waited in the cold for them to leave and then hightailed back home.”

…and no lights.

Lighting was a similar problem. The winter nights were long, boring and cold. Candles were in very short supply, but not far from where Jo and his family lived was a factory that sometimes had leftover carbide as a by-product. When placed in a special lamp like the one below, it would create a tiny flame:

“By that flame, we spent the nights reading books out loud. And ruined our eyes in the process.”

An alternative was driving a dynamo. Yes, the exact same dynamo that some of you may remember having on your bicycles. Not the one that turns easily, but the one that made you decide risking cycling without a light because the dynamo made it so much harder to peddle.

Carbide could make a flame, but it couldn’t power the clandestine radio that some people had in order to listen to the motivational speeches of the Queen and Prime Minister, who had fled to England. Or to listen for messages of the Resistance, if you dared.

One of the few ways of getting such a radio going was mounting a bicycle on a frame and… cycle. As fast as you could, taking turns because it was tiring. You could light an electrical lamp that way, too, but as my grandfather said, that was a waste of energy. Not electrical energy, but vital energy.

Because worse than the cold and the darkness, was the increasing shortage of even the most basic foodstuffs…

Next Monday, Jo’s story concludes.

March 26, 2016

Surrealistic portrait

Lovely time lapse video of art in the making:

March 22, 2016

Shopping links!

Occasionally I must remind both myself and you, my dear readers, that I write novels and short stories as well as blog posts

Here are a few:

Click to buy this book from Amazon or my Gumroad shop.

Click to buy this book from Amazon or my Gumroad shop.

March 21, 2016

War Stories #2

“War Stories” is a series of my family’s personal experiences during World War II. Originally collected for and presented to my son’s class of 9-year-olds, this is where I share the non-sanitised versions.

Arbeitseinsatz

During WWII, most of the German men in their prime were drafted into the army, taking them away from jobs in the country’s industry. To replace that workforce, Nazi Germany had a policy called ‘Arbeitseinsatz’: young men from the country Nazi Germany had occupied were forced to work all kinds of jobs in Germany.

My grandfather Jo (short for Johannes/John) was one of those men.

He had served in the Dutch army in the months preceding the capitulation, and had been working as a clerk for a company in Amsterdam since then. In early 1943, he married his girlfriend Wil and life was as good as it was going to be in wartime.

My grandparents at their wedding, 1943

However, barely six weeks after their marriage, Jo was deported to work in Germany. In Halberstadt, to be precise.

He was assigned as a clerk to a factory that produced all kinds of wooden items, such as plates, bowls and furniture. In the autobiography he left after his death, he said that his boss had assumed that all foreign workers were volunteers. Jo quickly dispelled that faulty presumption by saying that as a newlywed, he most certainly hadn’t come of his own volition.

His boss felt sorry for him, and made certain to arrange accommodations for him with a kind family who treated him well. And they did. Jo said that despite it being forced labour and letters being his only contact with his young wife, he led a fairly comfortable life.

But nevertheless, he was over 500 kilometres away from home. For almost a year. Understandably, he was terribly homesick.

So when March 1944 rolled around and he told his boss that it was Wil’s birthday soon, his boss permitted him a two-week leave, including permission to travel to Amsterdam an back! That was a big deal: travel was restricted and unless you had the proper papers, you were arrested. And by this time in the war, anyone who was arrested ended up in a concentration camp.

Jo rushed to get his travel permit properly validated and ran to the train station to broad the night-train heading West.

But while his papers were in order, he had taken a big risk: wanting to bring a present for his wife, he had smuggled a wooden plate in his luggage. Ridiculous as it may sound, Jo risked his life by taking that plate!

The use of wood was restricted. The transportation of wood was permitted only to Germany companies. Reason for this was that wood – like steel, copper and rubber – were reserved for army equipment and weapons. The wood was used for the handles of hand grenades:

Unlike US or UK hand grenades, the hand grenades used by the German army had a handle. You threw them like you would a knife, and the spinning motion the handle created made for increased range and accuracy of the throw.

So any foreigner caught with restricted materials would be arrested and send to a camp.

Jo held his breath at every stop. Papers were checked and he saw people taken off the train by the German military police, but no one asked him for his. Luggage was searched multiple times, but never his bag…

Throughout that long train ride, he wasn’t caught. But that didn’t mean he was out of danger!

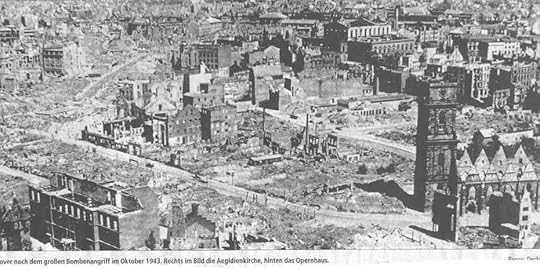

It was already late when the train passed through Hannover. That city had been reduced to ruins by a bombardment a few months earlier, and Jo recalled explicitly how the sight – what he could see of it in the dark – had struck him. Unbeknownst to him, daytime reality was worse:

What was left of the centre of the city of Hannover after the bombing of October 1943.

And still, every day and every night, the Allied bombers flew over Germany to bomb cities, industries… and railroads.

Sometime past midnight, the train had stopped again to take on water and coal for its steam engine. To make the cities and towns less visible to the bombers at night, all windows were blacked out, so it was very dark outside.

And then the air raid siren went off!

Train stations were among the bombers’ primary targets, so as soon as this horrendous mechanical howling started, the train driver threw as much coal in the engine as it would take in order to pull the train out of the station as quickly as possible. Working without safety, the smoke from the locomotive’s chimney glowed red from the fire. They risked the steam engine exploding, but the falling bombs would do the same. Jo was terrified!

After anxious moments, the train started moving, faster and faster, and finally cleared the station – without taking a hit.

And thus, Jo arrived back in Amsterdam, shaken but in one piece. And with the wooden plate he had brought as a gift for his wife. My family still has it. It is a very simple slab of wood with minimal decorative carving and a little sticker on the back stating the name of the wood factory where my grandfather was forced to work. It is amazing to imagine that this unremarkable object might have cost him his life.

But, in his own words, he was a very lucky man. He had known hardships and loss all through his life, but more than once he made a miraculous escape. Avoiding being searched or blow up while on the train was only part of his luck that day: about a week after his departure, Halberstadt was bombed…

Needless to say, he didn’t go back to Germany.

His luck seemed to have abandoned him, though, when in May 1944, Jo contracted meningitis. He was hospitalised, but with no medication, his wife was told that it was only a matter of time before he died.

Yet he didn’t. It took months, but he recovered. Months in which his wife brought him food because the hospital had begun to run out, but he recovered. Completely! The doctors had no explanation: “You should be blind, mute, lame, deaf or dead, but you are none of the above. It shouldn’t be possible, but here you are.”

So the illness let no mark on him. However, what it did get him was exemption from further deportation: an official statement saying that he was unfit for work in Germany and only could perform light duties in the Netherlands.

That was autumn 1944. Weeks later, the south of the Netherlands was liberated.

But not Amsterdam. That city, along with the northern half of the Netherlands, would be in for one of the harshest winters ever.

Next Monday, Jo’s story continues.

March 20, 2016

Witches through the ages

Beautiful dark artwork of witches and witchcraft

Click here for more images:

http://chrissy-24601.tumblr.com/post/141363406391/vixensandmonsters-häxan-witchcraft-through-the

March 18, 2016

The Bare Bones of…”Death Note” (anime)

What: Death Note (anime)

What: Death Note (anime)

Why: Actually I was going to do another story for this month’s “Bare Bones”, but the celebrated manga-turned-anime series Death Note made such an unforgiveable screw-up in character development that I just have to rant.

Spoiler Alert: Low | Medium | HIGH!

Summary:

Death Note starts with an intriguing premise: Light Yagami, a diligent Japanese student, finds an apparently ordinary notebook. However, according to the instructions written on the cover, should anyone write down the name of a person in the notebook while imagining that person’s face, said person will die of heart failure.

Intelligent, inquisitive and emotionally detached as Light is by nature, he conducts a few experiments with criminals he sees in a news broadcast. It works. Exactly forty seconds after he has written their names in the notebook, the criminals die.

Light realises that he holds the power to change the world in his hand, which he is not afraid to use. He goes on a killing spree, and before long the media report about the mysterious ‘Kira’ (Japanese verbalisation of ‘killer’).

An interesting complication is that Light’s father is the police officer charged with finding and arresting Kira. But Light is neither impressed nor worried and merrily continues killing criminals, until the police receive help from the equally mysterious ‘L’, a master detective, and a deadly cat-and-mouse game ensues.

…much to the amusement of Ryuku, the demonic shinigami (Japanese god of death) who planted the notebook for Light to find.

Story Skeleton:

The characterisation and dynamics are what drew me into the story. Light is manipulative and has psychopathic tendencies from the start, which makes for a nice change from the average protagonist. The Death Note doesn’t change him into a murderer, but rather enables him to be the murderer that he already had the potential to become.

Both Light and L are highly intelligent. They are rivals in all the best ways, constantly analysing what move they should make in order to manipulate a particular response from the other. A beautiful pas-de-deux that is only enhanced by the fact that L is weird in his own way: strange eyes, always sloughed, always bare-footed, always eating sweets but never gaining weight, and he moves in a very peculiar way…

… the same way in which the shinigami Ryuku moves!

L seems to understand the process ‘Kira’ uses very quickly. Even though he doesn’t have all the answers, everything about L screams ‘shinigami’. The questions that raised were endless: does L know that he is a shinigami? Why is he posing as a human, and how? What is his story?

I watched episode after episode with great anticipation!

But 20 episodes later, L was merely human. And the character that succeeded him behaved in a nearly identical fashion. No reason, no explanation.

As you can imagine, the disappointment was immense.

Lesson learnt:

Russian writer Anton Chekhov said: “If you show a gun hanging on the wall in Chapter One, it has to be fired in Chapter Four.” The timing between introduction and conclusion aside, ‘Chekhov’s Gun’ is considered a basic rule of storytelling. If you drop a specific hint, that hint must be significant to the story!

Death Note broke this rule. That may be due to the fact that Japanese tend to have other rules of storytelling than Western cultures. This difference can be a blessing in terms of unexpected plot twists, but in this case, I lost all interest in the rest of the series after being stood up like that.

Pumping a well-rounded character so full of potential and then not paying off on that promise is more than bad manners toward the audience: anticlimactic character development doesn’t only degenerate the character, but also their story arc, and potentially dragging a considerable part of the overall plot down with them.

And for me, that is unforgiveable.

March 15, 2016

Mercedes’ Paris

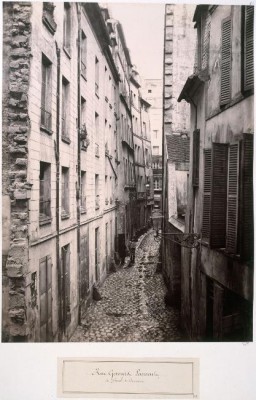

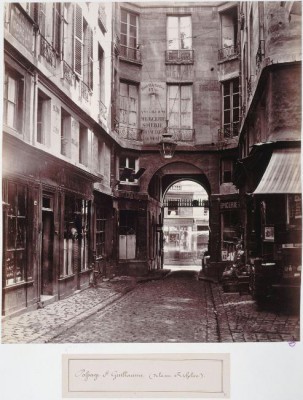

As I was preparing to upload Part 20 of The Devourer, I found these beauties hidden in the vaults of my photo collection. They give a good idea of Mercedes’ world and the places she sees during the story.

Source: vergue.com

Rue Gervais Laurent, where Anne lives.

Passage Saint Guillaume, taken from rue de Richelieu, a few steps down from where Mercedes and Eric live.

March 14, 2016

War Stories #1

“War Stories” is a series of my family’s personal experiences during World War II. Originally collected for and presented to my son’s class of 9-year-olds, this is where I share the non-sanitised versions.

Of Jews, grenades and bullet holes

After only a few days of combat in May 1940, the Netherlands were occupied by the German army. The effort to stay neutral – as the Dutch had during WWI – had failed, but life went on. Initially, anyway.

[image error]

It was not a secret that the Nazi soldiers had orders to round up all Jewish citizens. They were loaded on board

trains like cattle and transported eastwards, to the Third Reich. Where to? Work camps, as far as most people knew. Men, women and children. Those who resisted were taken by force. Those who had the chance went into hiding.

The most famous story of a Jewish family in hiding is no doubt Anne Frank’s Diary. But she was only one of countless. Not everyone had the courage to harbour Jewish fugitives, considering being found out often resulted in being deported to the camps as well.

Grandma Maas, the grandmother of my husband, did have the courage to do so.

The Maas family owned a farm just outside the village of Deurne, in the south-east of the Netherlands. Deurne was large enough to have a train station, and the railroad from the west of the country to the eastern border with Germany led through the village. And so many a train with Jewish deportees passed the Maas’ farmland.

Because of the station, all trains had to reduce speed when approaching the village. Even if they didn’t stop there, they couldn’t thunder through regardless.

Sometimes a train of deportees slowed enough that a few people dared to jump. They risked getting shot on sight by the soldiers if they were caught, but that was a risk worth taking. The Jewish community had survived centuries of persecution already, so most of them knew that it would be even more dangerous to find out what waited for them at the end of the train ride.

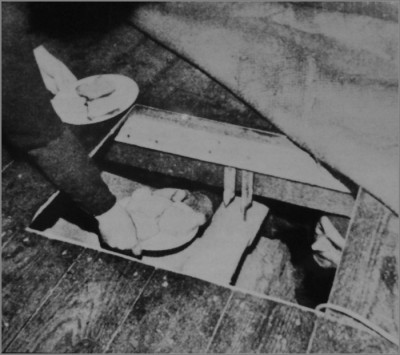

Those who managed to jump and get away from the train without being seen – or at least without being hit – ran for the first house in sight: the Maas’ family farm. And so it happened that Grandma Maas had as much as several dozen Jews hiding in her basement.

In hiding under the floor (not the Maas’ farm)

Source: dedokwerker.nl

The escape hotspot nearby Deurne was of course well known to the German troops, and so all houses and farmsteads were searched from time to time. So far the Maas family and their guests had avoided detection, but in the summer of 1944, their luck was up.

During another raid on the farm, a young German soldier discovered the over 40 people hiding in the basement. He had his orders, and so he took out a hand grenade, armed it, and raised his arm to throw the grenade amongst the huddled refugees.

But he hesitated. For the longest time, he simply stood on the narrow wooden steps leading into the basement, the grenade in his hand ready to explode after mere instants if he should let it go.

Behind him stood Grandma Maas. She didn’t speak German and the young soldier didn’t speak the local dialect, but sometimes, words don’t need translating.

“Think carefully, my boy, about what you’re about to do,” she said.

For long moments, the soldier stood still. Then he disarmed the hand grenade, put it away, and stomped off without another word.

The refugees sighed in relief, but both they and Grandma Maas knew it wasn’t over yet. The soldier might well come back with reinforcements to finish the job!

Minutes turned into hours, hours into days, but they never saw the soldier again. Weeks later, the allied troops arrived in the Netherlands and liberated the south, the little village of Deurne included. And so the Jews hiding in Grandma’s basement survived the war.

The same could not be said of Grandma Maas’ wardrobe!

Indeed, casualties of war aren’t always people and animals, but the overall destruction was immense. To this day, older houses along the route from Eindhoven to Arnhem (which turned out to be “A Bridge Too Far”) show bullet holes left by the fighting that took place in the autumn of 1944.

One of those bullets didn’t hit the brickwork of the Maas’ farm, but flew in through the window, punctured the side of the wardrobe in the room, went through it, and came out on the other side. No one was injured, except… Grandma’s clothes!

All her clothes had two holes, one at the back and one at the front, where the bullet had tore through them. Years after the war had ended, it was still too expensive to replace clothes, so she patched them. Her daughter (my mother-in-law) recalls that Grandma always had two patches on her shoulder, one at the front and one at the back…

More stories next week Monday!

Click here to read Strip Poker

Click here to read Strip Poker