Chris Goff's Blog, page 60

October 7, 2016

Does the cat die?

S. Lee Manning: My Tonkinese cat, Xiao Mao - Chinese for little cat- ten pounds of sleek gray fur and energy, hates to be alone. He follows me from room to room, and when I sit down to write, read, or watch television, insists on crawling into my lap. If I dare to play the guitar, which means no lap, he climbs to the top of the cabinets and meows until I pay him the attention he thinks is his due.

If

I ignore him, he'll leap from the floor onto my shoulder, where he'll curl around the back of myneck and purr - until I've had enough - and I dump him.

He would be happy to divide his time between me and my husband, Jim, but Jim, smarter and tougher than me, goes into the living room where he works and closes the door. When I complain that leaves me the sole target of Xiao's affection, he notes that I have a door to my office.

Like I said - tougher than me.

The only thing that allows me to get anything done - and I mean anything - is that cats sleep sixteen hours a day. Once he's really sleepy, he's willing to doze on the bed or the couch, especially if I've got a fire going in the wood stove - until mid-afternoon and close to his dinner time - when he has a tendency to climb onto the keyboard.

He's incredibly annoying...and I adore him.

Most likely, though, he'll never be in one of my espionage thrillers, because then I might feel obligated to kill him. And I can't bring myself to kill an animal in a book. I can write scenes in which my protagonist is horribly tortured, a man with a pregnant wife is shot, a lovely young woman is impaled, but kill an animal? Can't do it.

I hate books or movies where animals are killed. I have been known to consult the website, Does the Dog Die?, before agreeing on an evening's entertainment. I get previews of Game of Thrones from my family so I know to rush from the room just before the inevitable happens, because George R.R. Martin or the show's producers do not shrink at killing anyone or anything. I was more upset at the death of the dire wolf at the Red Wedding than the murder of multiple members of the Stark family.

This gets back to why I don't feel I can put Xiao in one of my novels. Cozy mysteries often feature cats or dogs, and the cats and dogs are never harmed. It's a different genre and goes for a different effect. In an espionage thriller, everyone and everything has to be at risk. Nothing increases the villainy of the bad guys more than the deaths -or possible deaths - of innocents. Nothing gets our emotions more engaged. The writer has to be willing to at least consider killing any character - except the protagonist in a continuing series - to increase suspense and the overall atmosphere of danger.

This gets back to why I don't feel I can put Xiao in one of my novels. Cozy mysteries often feature cats or dogs, and the cats and dogs are never harmed. It's a different genre and goes for a different effect. In an espionage thriller, everyone and everything has to be at risk. Nothing increases the villainy of the bad guys more than the deaths -or possible deaths - of innocents. Nothing gets our emotions more engaged. The writer has to be willing to at least consider killing any character - except the protagonist in a continuing series - to increase suspense and the overall atmosphere of danger.That includes cats and dogs.

There's the trope about Chekhov's gun that every writer knows. According to Chekhov, don't put a loaded gun in a story unless you intend to use it. Think of the cat as the loaded gun. You put a cat in a novel - and you have to find the most effective way to use the cat to move the story forward. In a thriller, doesn't that mean killing the cat?

On the other hand, the skilled writer who knows the rule about Chekhov's gun can feel free to break the rule. Breaking rules sometimes works better than following the rules. Maybe the cat doesn't have to die. Maybe the cat can be used to humanize the villain or even the protagonist. Maybe risk to the cat can raise the tension level and then the reader can be relieved when the cat survives.

Uh-oh, writing time is over. It's an hour to his dinner time, and Xiao is awake, rubbing, meowing,

pawing at the keyboard. I can either feed him early, which means he's hungry earlier tomorrow morning, or I have to fend him off for another sixty minutes.

Then, again, I could kill the cat.

Published on October 07, 2016 05:00

October 4, 2016

SAM THE DOG, & HOW HE BECAME A SPY

Gayle Lynds: Samuel (“Sam”) Johnson was the best dog in the world. Half black Labrador retriever and half giant German shepherd, he had the sweet disposition and looks of a lab and the size and imposing appearance of a horse. Well, a miniature horse, but at 150 joyful pounds, he was an intense object of desire by the neighborhood children; they wanted to throw a saddle on him and yell “Giddyup!”

Gayle Lynds: Samuel (“Sam”) Johnson was the best dog in the world. Half black Labrador retriever and half giant German shepherd, he had the sweet disposition and looks of a lab and the size and imposing appearance of a horse. Well, a miniature horse, but at 150 joyful pounds, he was an intense object of desire by the neighborhood children; they wanted to throw a saddle on him and yell “Giddyup!” Sam came into our family before my children were born, long before I was able to follow my secret dream of writing fiction. His journey with us still lingers in my mind and is an example of how the past informs an author’s life.

In a moment, I’ll tell you about all of that, but first you should know with this blog I begin the Rogue Women’s next series of posts,"Animals — stories and/or whether they impact our writing." You won’t want to miss these wonderful tales. To get your personal subscription, just click HERE.

Now back to Sam. . . . He was not only outsize in physique, but in habits. He’d dig enormous dirt holes in the flower garden, and my toddler son, Paul, would drag the hose around after him, filling the holes with water.

It was a partnership. Sam would slosh and roll, while Paul played happily in the mud next to him, patting and smearing it into shape, then wiping his hands on his clothes. Sam had an unerring sense of direction. He always knew which way Paul would follow with the hose.

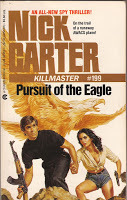

I called Sam “Wizard” in the first book in which he appeared. The novel, Pursuit of the Eagle, was pure male pulp adventure fiction. In it, Wizard’s directional sense was always accurate (no surprise there). Everyone marveled at him and expressed undying gratitude as he heroically led them out on a treacherous, muddy path winding through the mountains and to safety.

At a very early age, our dog Sam staked out his territory. If food fell onto the floor — usually because Paul and his little sister, Juli, were spilling, dropping, or throwing it — it was his. I had the cleanest floors in Santa Barbara. There was only one mishap. . . .

It was December, and I was grinding cranberries to make an old family recipe for cranberry relish. Three bright red cranberries landed on the floor. My faithful Sam had been sitting patiently, enjoying earlier mishaps — an orange slice, carrot shavings, and a piece of apple. Still starving, he lapped up one cranberry. His lips curled back. His muzzle wrinkled like an accordion. He shook his head, and spat. The cranberry flew across the room and stuck to the white refrigerator. He tried a second. Same result. And the third — he stared at it, turned, and walked out of the room. It was the only time I’d ever seen him defeated.

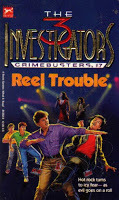

Sam’s second appearance in one of my books was in a Three Investigators mystery in the Crimebusters series. It was called Reel Trouble. Again I called him Wizard, and this time his dominant size kept everyone from approaching him, including the teenage investigators. Jupiter, the brains of the three, was a stout fellow who had decided to put himself on a strict (but ridiculous) diet of bananas and peanut butter, determined to lose some of his chubbiness.

As he stood studying Wizard, who was blocking a door so the boys couldn’t get inside to search, Jupiter realized the dog was eying his banana. He told his friends what he’d observed. “No way!” one objected. “Dogs don’t eat bananas!” said the other. Still, Jupiter chose an enticingly ripe banana, peeled it, and tossed it toward Wizard. By the time the dog had gulped it down, the boys were inside. Fortunately, Jupiter had several bananas in his backpack. And yes, Sam loved bananas.

Sam was a loyal and much loved member of our family. When I was pregnant, he went nuts, making sure I was safe not from people, but from dogs. Woe unto any four-legged creature who approached. Sam’s roaring barks peeled the limbs off trees.

Then as the children crawled, toddled, walked, and ran, Sam was with them, ushering them safely toward adulthood. He allowed them to roll on him, climb on him, and take the dog bones from his mouth. Admittedly he followed them around until they dropped the bones, but there was never a question that he would harm the children. He loved them. It didn’t take him long to learn to bury the bones though. Even for Sam, there were limits.

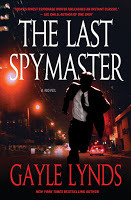

Sam’s final appearance was as another Wizard, this time in my award-winning The Last Spymaster . In it, he finally comes into his own. Partnered with one of the most important and fascinating characters, he’s a spy’s dog, fully trained in tradecraft, loyal, smart, and, of course, breath-takingly huge. Even though his master is given up for dead, he uses every trick he’s taught to save him — and succeeds. But that’s our remarkable Sam.

Sammy passed away when he was only seven years old, in 1977. I have many photos of him with us and the children, but none is digitized so I can’t present them here. So use your imagination — a classic black Labrador retriever so huge he has to be taken to a moving company to be weighed on its scale. So black that he could double as a furry ink blot. So sweet that when he grew too large to sit on my lap, he started turning around and backing up, centering his prodigious rear onto my lap. So tender that when I cried, he licked away my tears. That dog could smile. His mouth would open, his lips would curve up, and his eyes would dance. Thirty-nine years later, I still have his dog collar, and he still has my heart.

Do you have a story about a pet you’ve loved? Please tell us!

Published on October 04, 2016 21:22

October 2, 2016

LET'S BE REAL

by Chris Goff

One of the hardest tasks in writing an espionage thriller—AFTER you establish the rituals that get you into the chair and writing, learn the rules and conventions so you know when you can break them, develop your characters, plot the story (as I, too am a plotter) and establish pace—is imbuing your story with twists and turns and bigger than life events while making sure the readers BELIEVE it can happen.Easy? No!The mark of a great story, as KJ Howe pointed out, is writing so deftly that the readers lose themselves in the story. The key to getting them to suspend their beliefs and go along for the ride is to MAKE IT SEEM REAL. Researching ProfessionsFind out what's real and what's not real. You want your character to ring true. Take your average CIA agent. Not many of us have experience. Even Francine, our token Rogue Women CIA agent, wasn’t an operative. She trained to be an operative, as all agents do, but she was assigned as an analyst. As information came in, she read and quantified the value of the Intel. And if she ever did work in the field, she isn't telling. Analyst or asset defines a majority of CIA agents. These are people whose job is to gather, deliver and analyze Intelligence. So what is the real CIA spook—the field operative--like?

One of the hardest tasks in writing an espionage thriller—AFTER you establish the rituals that get you into the chair and writing, learn the rules and conventions so you know when you can break them, develop your characters, plot the story (as I, too am a plotter) and establish pace—is imbuing your story with twists and turns and bigger than life events while making sure the readers BELIEVE it can happen.Easy? No!The mark of a great story, as KJ Howe pointed out, is writing so deftly that the readers lose themselves in the story. The key to getting them to suspend their beliefs and go along for the ride is to MAKE IT SEEM REAL. Researching ProfessionsFind out what's real and what's not real. You want your character to ring true. Take your average CIA agent. Not many of us have experience. Even Francine, our token Rogue Women CIA agent, wasn’t an operative. She trained to be an operative, as all agents do, but she was assigned as an analyst. As information came in, she read and quantified the value of the Intel. And if she ever did work in the field, she isn't telling. Analyst or asset defines a majority of CIA agents. These are people whose job is to gather, deliver and analyze Intelligence. So what is the real CIA spook—the field operative--like?

First, there aren't many, and the ones we have are nothing like James Bond. Your typical spy doesn't jet around in a Gulfstream, doesn't always were Armani suits or tuxedos, doesn't order room service and have beautiful women lining up outside his hotel room door. The female version isn't always drop-dead gorgeous, drenched in jewels and better at Kung Fu than Jackie Chan. I recently attended a workshop given by an ex-CIA field operative and here are a few things I learned:

1. Spies dress just like you and I. The key is to blend in. A spy doesn't want to be noticed. Imagine how James would stand out if he showed up fly-fishing to get close to Vladimir Putin while wearing his tux.

2. Whenever possible, spies avoid killing people. Dead bodies tend to draw attention, and—remember—a spy doesn't want to be noticed.

3. When bugs are to be planted, most spies call in an "audio team" (so named before video cameras were popular), known to bug an enemy embassy or residence in under fifteen minutes. Fun fact: one of the best places to place a bug is on the back of a refrigerator. Makes sense! Have you ever thrown a dinner party where no one congregated in the kitchen?

Bottom line, if you get the small details right, your reader will go along with you on the bigger breaches of protocol and your work will carry an air of authenticity.Researching Locales photo by Dariusz SankowskiIt’s wonderful to be able to travel to the location of your story, but it’s not always necessary. In today’s world, you can gather a lot of information about foreign cities or countries, the way the people live, the issues the citizens are facing off the internet, in travel guides, in non-fiction books. A lot of writers fabricate the cities and towns, which makes it easier. But, if you use Moscow, you better know enough about Moscow to make it feel real to the readers. If you create a fictional town in Russia, you better get the feel of Russia on the page.

photo by Dariusz SankowskiIt’s wonderful to be able to travel to the location of your story, but it’s not always necessary. In today’s world, you can gather a lot of information about foreign cities or countries, the way the people live, the issues the citizens are facing off the internet, in travel guides, in non-fiction books. A lot of writers fabricate the cities and towns, which makes it easier. But, if you use Moscow, you better know enough about Moscow to make it feel real to the readers. If you create a fictional town in Russia, you better get the feel of Russia on the page.

One of the best compliments I received about my debut thriller, DARK WATERS, was how “real” it felt. A friend who had spent time in Tel Aviv, Bethlehem and the West Bank approached me after reading my novel and told me that the book transported her back to her time in Israel. The world came to life for her, which made my job of having her believe my story much easier.Creating the Action and Establishing PaceThis is where it gets dicier. To keep things tense and fast-paced, thriller authors often must condense the time it takes things for things to happen to an unrealistically short period of time. In real life, very few field operations happen in a couple of days, or even a couple of weeks. Remember, CIA agents mostly gather Intel. It takes time to prepare for a mission. But, in fiction, while the enemy has been preparing for two years to blow up the Hoover Dam, your operative will have all of two days to thwart the attack. Moscow

Moscow

How do you make it plausible? Make sure there's absolutely no other choice for your hero or heroine. If they don't act, Paris will burn, the President will be kidnapped and life as we know it will end. Ratcheting up the tension and increasing the urgency are what keeps readers plowing forward and legitimizes the protagonist's actions. Make sure your heroine has to act, that she's the only one who can act, and then throw every possible obstacle and problem in her way. Set the ticking clock, up the stakes, make it personal, exhaust all the options, and appeal to your readers' own fears and phobias. Use every available element of suspense. Your reader will have no choice but to hang on and go along with the action—as long as you keep it REAL.Bottom LineWriting is hard work. It's a lot of "butt in the chair" writing, reading, honing of craft, but there's nothing more satisfying than spinning a tale that a reader finds thrilling, believable and satisfying in the end.What makes you lose yourself in a story and just go along for the ride? This blog ends the series on "Writing Tips.” Next up, Gayle Lynds kicks off the Rogue Women series on "Animals - stories and/or do they impact your writing." To get your personal subscription to our blog, just click here.

One of the hardest tasks in writing an espionage thriller—AFTER you establish the rituals that get you into the chair and writing, learn the rules and conventions so you know when you can break them, develop your characters, plot the story (as I, too am a plotter) and establish pace—is imbuing your story with twists and turns and bigger than life events while making sure the readers BELIEVE it can happen.Easy? No!The mark of a great story, as KJ Howe pointed out, is writing so deftly that the readers lose themselves in the story. The key to getting them to suspend their beliefs and go along for the ride is to MAKE IT SEEM REAL. Researching ProfessionsFind out what's real and what's not real. You want your character to ring true. Take your average CIA agent. Not many of us have experience. Even Francine, our token Rogue Women CIA agent, wasn’t an operative. She trained to be an operative, as all agents do, but she was assigned as an analyst. As information came in, she read and quantified the value of the Intel. And if she ever did work in the field, she isn't telling. Analyst or asset defines a majority of CIA agents. These are people whose job is to gather, deliver and analyze Intelligence. So what is the real CIA spook—the field operative--like?

One of the hardest tasks in writing an espionage thriller—AFTER you establish the rituals that get you into the chair and writing, learn the rules and conventions so you know when you can break them, develop your characters, plot the story (as I, too am a plotter) and establish pace—is imbuing your story with twists and turns and bigger than life events while making sure the readers BELIEVE it can happen.Easy? No!The mark of a great story, as KJ Howe pointed out, is writing so deftly that the readers lose themselves in the story. The key to getting them to suspend their beliefs and go along for the ride is to MAKE IT SEEM REAL. Researching ProfessionsFind out what's real and what's not real. You want your character to ring true. Take your average CIA agent. Not many of us have experience. Even Francine, our token Rogue Women CIA agent, wasn’t an operative. She trained to be an operative, as all agents do, but she was assigned as an analyst. As information came in, she read and quantified the value of the Intel. And if she ever did work in the field, she isn't telling. Analyst or asset defines a majority of CIA agents. These are people whose job is to gather, deliver and analyze Intelligence. So what is the real CIA spook—the field operative--like?

First, there aren't many, and the ones we have are nothing like James Bond. Your typical spy doesn't jet around in a Gulfstream, doesn't always were Armani suits or tuxedos, doesn't order room service and have beautiful women lining up outside his hotel room door. The female version isn't always drop-dead gorgeous, drenched in jewels and better at Kung Fu than Jackie Chan. I recently attended a workshop given by an ex-CIA field operative and here are a few things I learned:

1. Spies dress just like you and I. The key is to blend in. A spy doesn't want to be noticed. Imagine how James would stand out if he showed up fly-fishing to get close to Vladimir Putin while wearing his tux.

2. Whenever possible, spies avoid killing people. Dead bodies tend to draw attention, and—remember—a spy doesn't want to be noticed.

3. When bugs are to be planted, most spies call in an "audio team" (so named before video cameras were popular), known to bug an enemy embassy or residence in under fifteen minutes. Fun fact: one of the best places to place a bug is on the back of a refrigerator. Makes sense! Have you ever thrown a dinner party where no one congregated in the kitchen?

Bottom line, if you get the small details right, your reader will go along with you on the bigger breaches of protocol and your work will carry an air of authenticity.Researching Locales

photo by Dariusz SankowskiIt’s wonderful to be able to travel to the location of your story, but it’s not always necessary. In today’s world, you can gather a lot of information about foreign cities or countries, the way the people live, the issues the citizens are facing off the internet, in travel guides, in non-fiction books. A lot of writers fabricate the cities and towns, which makes it easier. But, if you use Moscow, you better know enough about Moscow to make it feel real to the readers. If you create a fictional town in Russia, you better get the feel of Russia on the page.

photo by Dariusz SankowskiIt’s wonderful to be able to travel to the location of your story, but it’s not always necessary. In today’s world, you can gather a lot of information about foreign cities or countries, the way the people live, the issues the citizens are facing off the internet, in travel guides, in non-fiction books. A lot of writers fabricate the cities and towns, which makes it easier. But, if you use Moscow, you better know enough about Moscow to make it feel real to the readers. If you create a fictional town in Russia, you better get the feel of Russia on the page.One of the best compliments I received about my debut thriller, DARK WATERS, was how “real” it felt. A friend who had spent time in Tel Aviv, Bethlehem and the West Bank approached me after reading my novel and told me that the book transported her back to her time in Israel. The world came to life for her, which made my job of having her believe my story much easier.Creating the Action and Establishing PaceThis is where it gets dicier. To keep things tense and fast-paced, thriller authors often must condense the time it takes things for things to happen to an unrealistically short period of time. In real life, very few field operations happen in a couple of days, or even a couple of weeks. Remember, CIA agents mostly gather Intel. It takes time to prepare for a mission. But, in fiction, while the enemy has been preparing for two years to blow up the Hoover Dam, your operative will have all of two days to thwart the attack.

Moscow

MoscowHow do you make it plausible? Make sure there's absolutely no other choice for your hero or heroine. If they don't act, Paris will burn, the President will be kidnapped and life as we know it will end. Ratcheting up the tension and increasing the urgency are what keeps readers plowing forward and legitimizes the protagonist's actions. Make sure your heroine has to act, that she's the only one who can act, and then throw every possible obstacle and problem in her way. Set the ticking clock, up the stakes, make it personal, exhaust all the options, and appeal to your readers' own fears and phobias. Use every available element of suspense. Your reader will have no choice but to hang on and go along with the action—as long as you keep it REAL.Bottom LineWriting is hard work. It's a lot of "butt in the chair" writing, reading, honing of craft, but there's nothing more satisfying than spinning a tale that a reader finds thrilling, believable and satisfying in the end.What makes you lose yourself in a story and just go along for the ride? This blog ends the series on "Writing Tips.” Next up, Gayle Lynds kicks off the Rogue Women series on "Animals - stories and/or do they impact your writing." To get your personal subscription to our blog, just click here.

Published on October 02, 2016 21:00

October 1, 2016

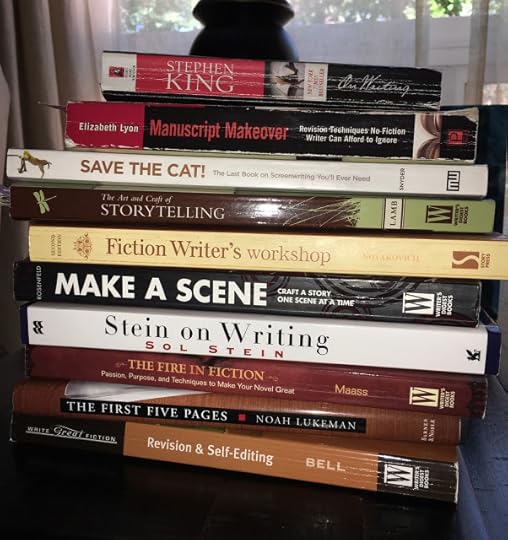

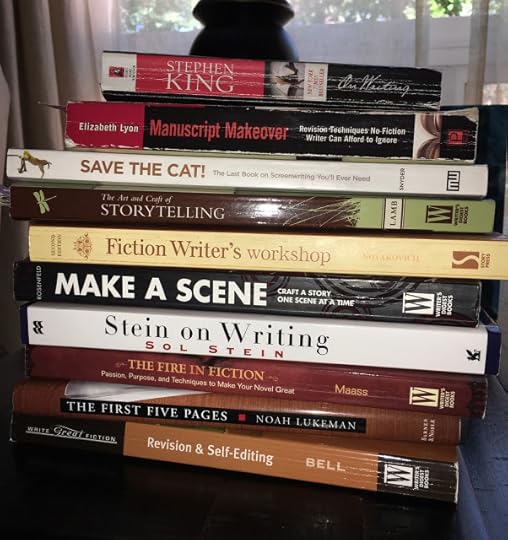

10 BOOKS TO MAKE YOU A BETTER WRITER TODAY

By Sonja StoneWRITING TIPS FROM THE EXPERTS (Not Me)

A few of my favorites

A few of my favorites

I feel horribly unqualified to offer writing advice. Not because I’m a bad writer; I don’t think that’s the case. But because A) I’m a terrible teacher, and B) I have no idea how people write books whilst maintaining any semblance of life balance.

THOSE WHO CAN’T TEACH… JUST SHOULDN’T

A) Fact: I am a terrible teacher.

I know, I know. This is the point in the conversation when you say, “Oh, I'm sure that's not true.”

Rest assured, it’s true.

HERE'S AN EXAMPLE OF HOW I TEACH:Me: One-fourth is equivalent to 25%.Unfortunate Victim (aka ‘student’): I don’t understand.Me: *shouts* ONE-FOURTH is EQUIVALENT or EQUAL TO TWENTY-FIVE PERCENT.Victim: Yes, I heard you the first time. But I don’t understand how you came up with that number.Me: *throws hands up* I can’t talk to you when you’re like this.

This is not a joke. I’m a published author and to this day my children will not ask me to proofread their papers. From the tender age of eight or nine, the scene followed a predictable pattern: violent slashes of red ink; harsh words exchanged; tear-stained faces as mother and child stormed from the room.

MAINTAINING BALANCE

B) Fact: I work obsessively. Or not at all.

For the second time, my editor has offered a deadline extension. Here’s what my day looks like: Wake at 4:30, start the coffee, sit at my desk. Open my manuscript. Work on the draft for ten solid hours (with occasional snack breaks). Stumble away from my office bleary eyed and frustrated, nuke dinner, go to bed by 9:00.

Wake, repeat.

As my deadline draws ever nearer, the chatter in my head roars to a deafening volume. My inner critics drown out my characters and clamor for attention.

The voice of the responsible employee says, “For the love of God, just get it done.”The perfectionist answers, “Tsk, tsk. Embracing mediocrity, are we?” The impatient child screams, “This isn’t fun anymore!”The impulsive teenager adds, “Let’s go catch a movie…”

PLOTTING VS. PANTSING

Friday’s post, I’M A PLOTTER, THANK YOU VERY MUCH, by Francine Matthews, raised a question writers are often asked: do you outline your story before you begin, or make it up as you go along? (For those of you unfamiliar with the term, ‘pantsing’ refers to writing without an outline, aka, flying-by-the-seat-of-your-pants.)

My first novel, Desert Dark , took about eight years from start to finish. I had no plan; each day I’d sit at my computer and type whatever came to mind. If you’ve read any of my blog posts you’ve probably noticed that my thoughts are often scattered, disjointed, and seemingly irrelevant to whatever came before. The same is true with novel writing; thus, the eight years.

I’m currently working on the sequel. As I’m under contract, my publishing house (reasonably) asked for an outline of book two. I found the process both helpful and excruciating. The spontaneous joy of an unfolding story is missing; however, I do anticipate that I will need substantially less time to finish. But it’s still taking longer than I think it should.

So is the problem lack of planning? Too much planning? Maybe the wrong kind of planning.

I solve problems one of two ways:

1) Immediately jump in, having very little information and no understanding of the magnitude of the issue, get three-quarters of the way through, realize I'm in over my head (or bored), and haul ass out; OR

2) Conduct EXHAUSTIVE research, studying all angles, issues, factors, and possible solutions, and then either:

A) Decide the problem is insurmountable and don't even try, OR

B) Get bored because I've already solved the problem in my head.

As you might imagine, this makes novel writing difficult.

ADVICE TO SELF: SEEK HELP

Now that I’ve convinced you of my lack of credentials, perhaps you’re wondering what I could possibly add to the plethora of helpful writing tips offered by my blog sisters in the last few weeks. Fear not: I won’t be teaching you anything at all. Instead, I’ve compiled a short list of my favorite writing books. This list is by no means all-inclusive, but the pages of the books listed here are highlighted, underlined, and lovingly dog-eared.

1. On Writing , by Stephen King2. Manuscript Makeover , by Elizabeth Lyon3. Save the Cat , by Blake Snyder4. The Art and Craft of Storytelling , by Nancy Lamb5. Fiction Writer’s Workshop , by Josip Novakovich6. Make A Scene , by Jordan E. Rosenfeld7. Stein on Writing , by Sol Stein8. The Fire in Fiction , by Donald Maass9. The First Five Pages , by Noah Lukeman10. Revision & Self-Editing , by James Scott Bell

This list reflects a fraction of my collection, but I’m always looking to add to my toolbox. If you have a favorite to recommend, please leave the title in the comment section!

A few of my favorites

A few of my favoritesI feel horribly unqualified to offer writing advice. Not because I’m a bad writer; I don’t think that’s the case. But because A) I’m a terrible teacher, and B) I have no idea how people write books whilst maintaining any semblance of life balance.

THOSE WHO CAN’T TEACH… JUST SHOULDN’T

A) Fact: I am a terrible teacher.

I know, I know. This is the point in the conversation when you say, “Oh, I'm sure that's not true.”

Rest assured, it’s true.

HERE'S AN EXAMPLE OF HOW I TEACH:Me: One-fourth is equivalent to 25%.Unfortunate Victim (aka ‘student’): I don’t understand.Me: *shouts* ONE-FOURTH is EQUIVALENT or EQUAL TO TWENTY-FIVE PERCENT.Victim: Yes, I heard you the first time. But I don’t understand how you came up with that number.Me: *throws hands up* I can’t talk to you when you’re like this.

This is not a joke. I’m a published author and to this day my children will not ask me to proofread their papers. From the tender age of eight or nine, the scene followed a predictable pattern: violent slashes of red ink; harsh words exchanged; tear-stained faces as mother and child stormed from the room.

MAINTAINING BALANCE

B) Fact: I work obsessively. Or not at all.

For the second time, my editor has offered a deadline extension. Here’s what my day looks like: Wake at 4:30, start the coffee, sit at my desk. Open my manuscript. Work on the draft for ten solid hours (with occasional snack breaks). Stumble away from my office bleary eyed and frustrated, nuke dinner, go to bed by 9:00.

Wake, repeat.

As my deadline draws ever nearer, the chatter in my head roars to a deafening volume. My inner critics drown out my characters and clamor for attention.

The voice of the responsible employee says, “For the love of God, just get it done.”The perfectionist answers, “Tsk, tsk. Embracing mediocrity, are we?” The impatient child screams, “This isn’t fun anymore!”The impulsive teenager adds, “Let’s go catch a movie…”

PLOTTING VS. PANTSING

Friday’s post, I’M A PLOTTER, THANK YOU VERY MUCH, by Francine Matthews, raised a question writers are often asked: do you outline your story before you begin, or make it up as you go along? (For those of you unfamiliar with the term, ‘pantsing’ refers to writing without an outline, aka, flying-by-the-seat-of-your-pants.)

My first novel, Desert Dark , took about eight years from start to finish. I had no plan; each day I’d sit at my computer and type whatever came to mind. If you’ve read any of my blog posts you’ve probably noticed that my thoughts are often scattered, disjointed, and seemingly irrelevant to whatever came before. The same is true with novel writing; thus, the eight years.

I’m currently working on the sequel. As I’m under contract, my publishing house (reasonably) asked for an outline of book two. I found the process both helpful and excruciating. The spontaneous joy of an unfolding story is missing; however, I do anticipate that I will need substantially less time to finish. But it’s still taking longer than I think it should.

So is the problem lack of planning? Too much planning? Maybe the wrong kind of planning.

I solve problems one of two ways:

1) Immediately jump in, having very little information and no understanding of the magnitude of the issue, get three-quarters of the way through, realize I'm in over my head (or bored), and haul ass out; OR

2) Conduct EXHAUSTIVE research, studying all angles, issues, factors, and possible solutions, and then either:

A) Decide the problem is insurmountable and don't even try, OR

B) Get bored because I've already solved the problem in my head.

As you might imagine, this makes novel writing difficult.

ADVICE TO SELF: SEEK HELP

Now that I’ve convinced you of my lack of credentials, perhaps you’re wondering what I could possibly add to the plethora of helpful writing tips offered by my blog sisters in the last few weeks. Fear not: I won’t be teaching you anything at all. Instead, I’ve compiled a short list of my favorite writing books. This list is by no means all-inclusive, but the pages of the books listed here are highlighted, underlined, and lovingly dog-eared.

1. On Writing , by Stephen King2. Manuscript Makeover , by Elizabeth Lyon3. Save the Cat , by Blake Snyder4. The Art and Craft of Storytelling , by Nancy Lamb5. Fiction Writer’s Workshop , by Josip Novakovich6. Make A Scene , by Jordan E. Rosenfeld7. Stein on Writing , by Sol Stein8. The Fire in Fiction , by Donald Maass9. The First Five Pages , by Noah Lukeman10. Revision & Self-Editing , by James Scott Bell

This list reflects a fraction of my collection, but I’m always looking to add to my toolbox. If you have a favorite to recommend, please leave the title in the comment section!

Published on October 01, 2016 21:01

September 29, 2016

I'M A PLOTTER, THANK YOU VERY MUCH

By Francine Mathews

During a panel at a writer's conference a few years back, the lovely and talented moderator, Catriona MacPherson, posed her final, devastating question to each of us:

"Plotter or Pantser?"This needed no explication for veterans of the conference scene. Plotters are the anal-retentive, overly-anxious types who have control issues about everything from the weight of the paper stock in their printers to the cover images forced on them by publishers. Their hapless characters move through a predetermined landscape to inevitably awful ends.

Pantsers are the creatives, who burn incense and scarf chocolate while awaiting the descent of the Muse. They follow the whims of their astrally-inspired synapses and are as astounded as their readers by their novels' conclusions. Endings, like life, should just...happen...somehow.

This is also known as writing organically. The theory being that things grow as they should, if you just throw enough shite at them.

I admire these writers.

I am not one of them.

Ask me to "pants" and I'd take to my bed with a hot toddy and acute vertigo. Without my cherished outlines, I'd never write a word. Easier by far to summit Everest in stilettos.

I wrote my first novel on a dare from my husband. He gave me a powerful incentive: If I could craft a beginning, middle and actual end of a book--not just, say, the first seventy pages that most of us find so exciting--we'd sit down and talk about me quitting my real job. I was tired of wearing stockings at eight a.m. I wanted to set my own schedule and work from home. I was motivated. I figured that if I were going to spend the next year mentally inhabiting a fictional world, it had better be one I enjoyed--so I wrote a classic detective novel set on Nantucket. It was purely an exercise, and like most first novels, it was far from perfect. But an agent accepted it and scored a two-book deal with a major publisher. I never went into an office again.

What worked for me?

Having a road map.

Imagine you're setting out on a journey. Leaving Las Vegas, for the sake of argument. In a month or so, you have to be in New York for the next phase of your life. You could sleep anywhere in between--Columbus or Yuma, Oshkosh or Greenville--but you're traveling with the unswervable goal of reaching Manhattan. The road gives you freedom to explore, of course--you can take any exit that tantalizes and go down that street for a while--but if it proves a deadend, you may double back, take a shortcut, reroute and get on the right track. And a month later, there's the sign for New York--as you expected.

Imagine you're setting out on a journey. Leaving Las Vegas, for the sake of argument. In a month or so, you have to be in New York for the next phase of your life. You could sleep anywhere in between--Columbus or Yuma, Oshkosh or Greenville--but you're traveling with the unswervable goal of reaching Manhattan. The road gives you freedom to explore, of course--you can take any exit that tantalizes and go down that street for a while--but if it proves a deadend, you may double back, take a shortcut, reroute and get on the right track. And a month later, there's the sign for New York--as you expected.That's what a plot outline does for your writing.

I always begin a novel with a great idea--a simple notion that intrigues and compels me. Fact: Jack Kennedy took off half his junior year at Harvard and traveled alone, from London to Moscow, as Hitler prepared to invade Poland. Fiction: What if Jack were also spying for Roosevelt?

Then I do a ton of research. I educate myself on the time period and the circumstances so that I'm confident I can tell a good story. I figure out the arc--the personal growth my main character has to endure by struggling with the conflict I hand them. Most importantly, I start my plot outline with the story's end.

This is critical. This is New York. The point of every road trip: our destination.

In the case of JACK 1939, the book had to conclude with Hitler invading Poland--and Jack Kennedy returning to Harvard to write his senior thesis. But that's merely the obvious structure of a novel set in a specific life and time period, the constraint of historical fiction. I knew this was really a coming-of-age story about a chronically ill young man, the black sheep of his family, who felt he had failed at everything he'd tried to accomplish in life. He'd lived in the shadow of his far more successful older brother and was convinced he'd be dead by thirty. So the psychological conclusion of the book would be far more important than the historical end:

Jack proves FDR was right to trust him. And he was right to have

faith in himself. He has lost the woman he loves and some respect for his father, but he's learned to trust his own courage and intelligence. Despite the limitations of poor health and reckless impulses, he has confronted profound evil and survived atrocity. He has fought the Good Fight. What he's learned on his Hero's Journey is critical to the man--and President--he becomes.

faith in himself. He has lost the woman he loves and some respect for his father, but he's learned to trust his own courage and intelligence. Despite the limitations of poor health and reckless impulses, he has confronted profound evil and survived atrocity. He has fought the Good Fight. What he's learned on his Hero's Journey is critical to the man--and President--he becomes.It's fundamental to know how your story begins. But knowing how it ends allows you, as a writer, to step out confidently on the writing road. It may even allow you to dabble in "pantsing," as you follow your characters down uncertain streets, then haul them back onto the straight and narrow. You're less likely to end up with your wheels in a ditch, waiting for a tow.

So here's a question: Can you tell whether a writer is a plotter or pantser by reading their books? Does it matter?

Cheers--

Francine

Published on September 29, 2016 19:00

September 27, 2016

The Habit Makes The Character

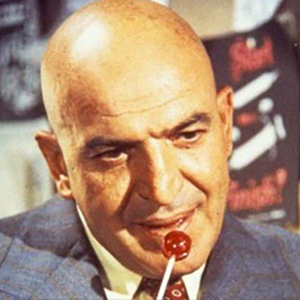

Kojak: "Who Loves 'Ya Baby?"

Kojak: "Who Loves 'Ya Baby?"by Jamie Freveletti

One of the toughest things to do in writing is to imbue your protagonist with some real traits that make them as unique as you hope them to be, and to do it in a way that isn’t obvious. As Karna mentioned in her post, showing, not telling, is a first step. We show the person sweating, rather than tell you that he’s scared. Well, with personality traits this works as well.

I’m going to rely here on a few from television and the movies, because actors bring a lot of personality quirks alive when they’re creating a character. I’ve often wished I could have a professional actor read my manuscript and then give me pointers on what they would do if they had to create the character on screen.

For example, in the television show Kojak, Telly Savalas imbues the character, a hard boiled police lieutenant, with a few quirks. The most loved one was his habit of sucking on lollipops. Kojak is tough, smart and mature, but he’s also trying to kick smoking and he reaches for a lollipop rather than a cigarette. This habit became ingrained in the character and made Kojak real.

Add something counter-intuitive to a character in your novel. It doesn’t have to be a big thing, but whatever it is, make it consistent. You’ll be surprised how this will help you, and your readers, connect to the character.

In my first Covert One novel, The Janus Reprisal, I thought about habits and decided to give Jon Smith, the Covert Operative protagonist, a habit of never accepting a hotel room above the third floor. Smith spends his life with risk and his genius is in the skills he uses to minimize it. He wants fire ladders to be able to reach the floor and he wants to be able to exit on his own if need be. He never wants to be trapped in a burning building or cornered by an attacker. In one scene he falls unconscious and wakes up in a room on the sixth floor of a high rise and his first thought is to flee to a lower elevation. The average person doesn’t have to worry about such things as a part of their daily lives, but a covert operator does. It’s a small part of Smith, but it helps to fill out the character. I'm glad I added it.

Once you’re onto this quirk- as- personality thing, it becomes almost a game to spot them. Monk’s obsessive compulsive behavior is obvious and endearing and Bond’s “shaken not stirred” drink preference is famous. And then there's Colombo’s last minute turn back to say, “Just one more thing…”

Give it a shot and let me know if it helps your work in progress!

Published on September 27, 2016 21:00

September 25, 2016

Breaking the Rules

by Karna Small Bodman

Whenever someone begins a new job, starts a business or even joins a club, she is usually told, "Here are the rules." She may even be given a handbook along with FAQ's and in some cases (for example taking certain government jobs) she is asked to sign a statement indicating she has actually "read the rules" and agrees to abide by them.

And then there's writing a novel! Yes, we authors go to many terrific conferences where we learn the writer's rules. One such meeting is the annual conference of the International Thriller Writers organization called "Thrillerfest" held at the Grand Hyatt in New York.

The Greeting at the Grand HyattClose to 1,000 come to New York to attend workshops, interviews and talks by some of the best published authors in the business who give us their version of the rules. One that is often drummed into us is the use of POV -- Point of View. We are told over and over again that we must have just one POV in a scene or chapter....the thoughts and reflections of the hero, the heroine, the villain or even a secondary character must be separated, because otherwise the reader can become confused about who's thinking what at a particular time. Editors call that "head-hopping."

The Greeting at the Grand HyattClose to 1,000 come to New York to attend workshops, interviews and talks by some of the best published authors in the business who give us their version of the rules. One that is often drummed into us is the use of POV -- Point of View. We are told over and over again that we must have just one POV in a scene or chapter....the thoughts and reflections of the hero, the heroine, the villain or even a secondary character must be separated, because otherwise the reader can become confused about who's thinking what at a particular time. Editors call that "head-hopping."

For example, you shouldn't write: "Steve had been devastated to hear that Emma was in an accident, but looking around, he was stunned to see her waltz into the ballroom wearing a slinky black dress and a big smile. As Emma gazed at the crowd in front of the bandstand, she wondered if Steve would be there." (See? You are hopping from his head into hers in the same scene). Big no-no.

Authors signing at Romance Writers Conference

Authors signing at Romance Writers Conference

Nora Roberts

Nora Roberts

However, at another popular conference in San Diego sponsored by Romance Writers of America, several bestselling authors were signing their books -- stories where they often break the POV rule....though they do it very skillfully. One author who's an expert is Nora Roberts. With over 500 million books in print (yes, you read that right - 500,000,000)...she can make her own rules!

Then there's the question of how you structure a novel. Many experts advise you to write an extensive chapter by chapter outline, or a complete synopsis, which for some authors can run anywhere from 5 to 90 pages (!) before sitting down and typing the words "Chapter One." Now here's another rule that can be broken.

I recall one bestselling author saying that there are two kinds of writers: First is The Tour Bus Driver. This one knows exactly where she's going. She knows where the tour starts and where it ends. She has the plot firmly in her mind. On her tour, she may pick up a few extraneous characters on the way, but she definitely knows her destination. Now she just has to sit down, follow the outline and create great scenes to get from point A to point B.

I recall one bestselling author saying that there are two kinds of writers: First is The Tour Bus Driver. This one knows exactly where she's going. She knows where the tour starts and where it ends. She has the plot firmly in her mind. On her tour, she may pick up a few extraneous characters on the way, but she definitely knows her destination. Now she just has to sit down, follow the outline and create great scenes to get from point A to point B.

The second type of writer is the Hitchhiker. This one has a general idea of where he'd like to go but has no clue how he's actually going to get there. He gathers his courage and hopes to meet characters who will take him to his destination. He's not sure what they will look like or how old they will be. But he's excited because it will be an adventure to meet them along the way. This author "lets" his characters tell their stories as the trip moves along.

The "most important rule" that is usually drummed into any writer from the get-go is "Show, Don't tell." In other words, don't tell the reader: "Jack was scared and wondered what he would find at the end of the hallway." Instead show the reader:" Jack wiped beads of perspiration off his forehead. With his heart racing, he crept to the end of the darkened hallway."

However, this is another rule that can be broken and in fact, IS broken in the final chapter of a famous novel. (I was reminded of this when I happened to read an essay on the subject by Robert Repino.) The novel is George Orwell's 1984. The concluding paragraph (with the exception of one sentence regarding tears) gives us a perfect example of how TELLING (not SHOWING) can be incredibly effective.

"He gazed up at the enormous face. Forty years it had taken him to learn what kind of smile was hidden beneath the dark mustache. O cruel, needless misunderstanding! O stubborn, self-willed exile from the loving beast! Two gin-scented tears trickled down the sides of his nose. But it was all right, everything was all right, the struggle was finished. He had won the victory over himself. He loved Big Brother."

And so, if you are writing the Great American Novel -- sit down, be creative, and if you really want to -- go ahead and BREAK THE RULES.

....by Karna Small Bodman

Whenever someone begins a new job, starts a business or even joins a club, she is usually told, "Here are the rules." She may even be given a handbook along with FAQ's and in some cases (for example taking certain government jobs) she is asked to sign a statement indicating she has actually "read the rules" and agrees to abide by them.

And then there's writing a novel! Yes, we authors go to many terrific conferences where we learn the writer's rules. One such meeting is the annual conference of the International Thriller Writers organization called "Thrillerfest" held at the Grand Hyatt in New York.

The Greeting at the Grand HyattClose to 1,000 come to New York to attend workshops, interviews and talks by some of the best published authors in the business who give us their version of the rules. One that is often drummed into us is the use of POV -- Point of View. We are told over and over again that we must have just one POV in a scene or chapter....the thoughts and reflections of the hero, the heroine, the villain or even a secondary character must be separated, because otherwise the reader can become confused about who's thinking what at a particular time. Editors call that "head-hopping."

The Greeting at the Grand HyattClose to 1,000 come to New York to attend workshops, interviews and talks by some of the best published authors in the business who give us their version of the rules. One that is often drummed into us is the use of POV -- Point of View. We are told over and over again that we must have just one POV in a scene or chapter....the thoughts and reflections of the hero, the heroine, the villain or even a secondary character must be separated, because otherwise the reader can become confused about who's thinking what at a particular time. Editors call that "head-hopping." For example, you shouldn't write: "Steve had been devastated to hear that Emma was in an accident, but looking around, he was stunned to see her waltz into the ballroom wearing a slinky black dress and a big smile. As Emma gazed at the crowd in front of the bandstand, she wondered if Steve would be there." (See? You are hopping from his head into hers in the same scene). Big no-no.

Authors signing at Romance Writers Conference

Authors signing at Romance Writers Conference

Nora Roberts

Nora RobertsHowever, at another popular conference in San Diego sponsored by Romance Writers of America, several bestselling authors were signing their books -- stories where they often break the POV rule....though they do it very skillfully. One author who's an expert is Nora Roberts. With over 500 million books in print (yes, you read that right - 500,000,000)...she can make her own rules!

Then there's the question of how you structure a novel. Many experts advise you to write an extensive chapter by chapter outline, or a complete synopsis, which for some authors can run anywhere from 5 to 90 pages (!) before sitting down and typing the words "Chapter One." Now here's another rule that can be broken.

I recall one bestselling author saying that there are two kinds of writers: First is The Tour Bus Driver. This one knows exactly where she's going. She knows where the tour starts and where it ends. She has the plot firmly in her mind. On her tour, she may pick up a few extraneous characters on the way, but she definitely knows her destination. Now she just has to sit down, follow the outline and create great scenes to get from point A to point B.

I recall one bestselling author saying that there are two kinds of writers: First is The Tour Bus Driver. This one knows exactly where she's going. She knows where the tour starts and where it ends. She has the plot firmly in her mind. On her tour, she may pick up a few extraneous characters on the way, but she definitely knows her destination. Now she just has to sit down, follow the outline and create great scenes to get from point A to point B.

The second type of writer is the Hitchhiker. This one has a general idea of where he'd like to go but has no clue how he's actually going to get there. He gathers his courage and hopes to meet characters who will take him to his destination. He's not sure what they will look like or how old they will be. But he's excited because it will be an adventure to meet them along the way. This author "lets" his characters tell their stories as the trip moves along.

The "most important rule" that is usually drummed into any writer from the get-go is "Show, Don't tell." In other words, don't tell the reader: "Jack was scared and wondered what he would find at the end of the hallway." Instead show the reader:" Jack wiped beads of perspiration off his forehead. With his heart racing, he crept to the end of the darkened hallway."

However, this is another rule that can be broken and in fact, IS broken in the final chapter of a famous novel. (I was reminded of this when I happened to read an essay on the subject by Robert Repino.) The novel is George Orwell's 1984. The concluding paragraph (with the exception of one sentence regarding tears) gives us a perfect example of how TELLING (not SHOWING) can be incredibly effective.

"He gazed up at the enormous face. Forty years it had taken him to learn what kind of smile was hidden beneath the dark mustache. O cruel, needless misunderstanding! O stubborn, self-willed exile from the loving beast! Two gin-scented tears trickled down the sides of his nose. But it was all right, everything was all right, the struggle was finished. He had won the victory over himself. He loved Big Brother."

And so, if you are writing the Great American Novel -- sit down, be creative, and if you really want to -- go ahead and BREAK THE RULES.

....by Karna Small Bodman

Published on September 25, 2016 21:30

September 24, 2016

GIVE YOUR READERS A WHIPLASH SMILE

by KJ Howe

The craft of writing is fascinating, at times unfathomable, but when writers hone their skills, the story shines through with no distractions. Readers lose themselves in the fascinating web the writer spins, soaking in page after page in an alternate world. Think of quality craft as freshly cleaned glass that showcases the scenery and action on the other side of a window. And consider poor craft as smudges, cracks, and fingerprints all over that glass, distracting from what readers want to enjoy--your characters and story.

Given the Rogue Women Writers write international thrillers, one of the key elements of craft is pacing. The story must churn at an exciting pace that grabs readers. When you drill down, what exactly does pacing mean?

Given the Rogue Women Writers write international thrillers, one of the key elements of craft is pacing. The story must churn at an exciting pace that grabs readers. When you drill down, what exactly does pacing mean?

*The rhythm or underlying beat of your story.

*The rate at which your novel unfolds--talented writers can manipulate time in readers' minds.

*The way writers structure their novels to engage reader's feelings, eliciting different emotions at different times.

Pacing is a nebulous concept that requires intuition and a keen sense of perception. There is no surefire formula to determine the perfect pace. A combination of a natural ear and plenty of practice at conveying what that nature ear "hears" is necessary in developing your writing voice. And faster isn't always better. Vary the pace and give readers time to develop their emotional response. Pacing is not measured in how many events you can cram into a novel. Rather, it is measured in the reader's emotional involvement in your characters.

If you'd like to analyze your pacing, try doing the following:

*Check the left margin of your text. Do yo have a variety of paragraph lengths? Is there enough white space or is the page smattered in ink? If your narrative is too dense, break up paragraphs or add in dialogue.

*Be sure you don't have repetitive sentence structures. A quick way to breathe life into your story is to vary your sentences lengths.

*Read your novel out loud. Does it sound slow, heavy, and overly description to your ear, or is the description so light that you aren't sure where the characters are? Adjust as necessary.

Once you decide whether you need to slow down or speed up your pace, you're ready to tackle rewrites.

Slowing Down

Too many fast-paced scenes will leave your reader breathless, exhausted. You need to build in breaks to create a different mood. Transition readers to a calmer place so they can regroup for the next tense scene.

Another reason to slow down is to intensify the emotional impact of a scene. Fight scenes are a great example. Time dilates as the antagonist launches his first punch. The actual moment before the punch isn't longer or shorter than any other moment, but it seems to go on forever because your character is so focused on waiting for the impact. This is the time to use your senses, including details about what your character is smelling, feeling, and tasting during these dramatic moments. Milk every ounce of tension. Need to slow things down? Try these tips:

*Use longer sentences and paragraphs.

*Include a dash of passive tense. Warning: do not overdo.

*Focus on flow and rhythm, rather than speed.

*Add descriptions steeped in sensory input, rich in texture and sound. Create a powerful setting where readers can lose themselves.

*Choose soft-sounding, mellow verbs like saunter, undulate, meander to create tranquility for the reader.

*Switch to a new viewpoint. This slows the pacing because readers are faced with a new set of possibilities and a fresh situation through new eyes.

Creating Whiplash

Thrillers are known for their page-turning prose. If you feel your novel needs a kick-start, here are a few techniques to try:

Thrillers are known for their page-turning prose. If you feel your novel needs a kick-start, here are a few techniques to try:

*Increase the amount of dialogue, as this creates white space on the page.

*Write lean, sparse prose. Avoid adjectives, adverbs, and long sentences. Short words convey tension.

*Add in harsh words to create a staccato rhythm.

*Use sentence fragments to create a sense of urgency. Focus on the mood you want to create.

*Give your character tunnel vision, shutting out everything but the imminent threat.

You can also increase the pacing of your novel through plot devices: using red herrings to create false leads, supporting the main threat with a number of smaller threats that can be resolved, including a time constraint (two minutes to diffuse a bomb), increasing your protagonist's obstacles, raising the stakes, killing off secondary characters.

Pacing issues are systemic, meaning they affect the entire book, so take your time and focus on fixing them. Readers won't continue turning pages if the pacing is off, whether too fast or too slow. Too fast, and you lose emotional connectivity with the reader. Too slow, and you might bore them, make them restless. One of the best ways to develop an ear for pacing is to read voraciously with a keen eye as to your reaction to other books' pacing. Then internalize what you have learned and apply it to your book.

Talented author Lee Child shares the following advice on pacing: make the fast parts slow and the slow parts fast. Advice from a pro that we should all live by. Thanks for joining us today. Would love to hear how a book's pacing affecting your impression of the read.

The craft of writing is fascinating, at times unfathomable, but when writers hone their skills, the story shines through with no distractions. Readers lose themselves in the fascinating web the writer spins, soaking in page after page in an alternate world. Think of quality craft as freshly cleaned glass that showcases the scenery and action on the other side of a window. And consider poor craft as smudges, cracks, and fingerprints all over that glass, distracting from what readers want to enjoy--your characters and story.

Given the Rogue Women Writers write international thrillers, one of the key elements of craft is pacing. The story must churn at an exciting pace that grabs readers. When you drill down, what exactly does pacing mean?

Given the Rogue Women Writers write international thrillers, one of the key elements of craft is pacing. The story must churn at an exciting pace that grabs readers. When you drill down, what exactly does pacing mean?*The rhythm or underlying beat of your story.

*The rate at which your novel unfolds--talented writers can manipulate time in readers' minds.

*The way writers structure their novels to engage reader's feelings, eliciting different emotions at different times.

Pacing is a nebulous concept that requires intuition and a keen sense of perception. There is no surefire formula to determine the perfect pace. A combination of a natural ear and plenty of practice at conveying what that nature ear "hears" is necessary in developing your writing voice. And faster isn't always better. Vary the pace and give readers time to develop their emotional response. Pacing is not measured in how many events you can cram into a novel. Rather, it is measured in the reader's emotional involvement in your characters.

If you'd like to analyze your pacing, try doing the following:

*Check the left margin of your text. Do yo have a variety of paragraph lengths? Is there enough white space or is the page smattered in ink? If your narrative is too dense, break up paragraphs or add in dialogue.

*Be sure you don't have repetitive sentence structures. A quick way to breathe life into your story is to vary your sentences lengths.

*Read your novel out loud. Does it sound slow, heavy, and overly description to your ear, or is the description so light that you aren't sure where the characters are? Adjust as necessary.

Once you decide whether you need to slow down or speed up your pace, you're ready to tackle rewrites.

Slowing Down

Too many fast-paced scenes will leave your reader breathless, exhausted. You need to build in breaks to create a different mood. Transition readers to a calmer place so they can regroup for the next tense scene.

Another reason to slow down is to intensify the emotional impact of a scene. Fight scenes are a great example. Time dilates as the antagonist launches his first punch. The actual moment before the punch isn't longer or shorter than any other moment, but it seems to go on forever because your character is so focused on waiting for the impact. This is the time to use your senses, including details about what your character is smelling, feeling, and tasting during these dramatic moments. Milk every ounce of tension. Need to slow things down? Try these tips:

*Use longer sentences and paragraphs.

*Include a dash of passive tense. Warning: do not overdo.

*Focus on flow and rhythm, rather than speed.

*Add descriptions steeped in sensory input, rich in texture and sound. Create a powerful setting where readers can lose themselves.

*Choose soft-sounding, mellow verbs like saunter, undulate, meander to create tranquility for the reader.

*Switch to a new viewpoint. This slows the pacing because readers are faced with a new set of possibilities and a fresh situation through new eyes.

Creating Whiplash

Thrillers are known for their page-turning prose. If you feel your novel needs a kick-start, here are a few techniques to try:

Thrillers are known for their page-turning prose. If you feel your novel needs a kick-start, here are a few techniques to try:*Increase the amount of dialogue, as this creates white space on the page.

*Write lean, sparse prose. Avoid adjectives, adverbs, and long sentences. Short words convey tension.

*Add in harsh words to create a staccato rhythm.

*Use sentence fragments to create a sense of urgency. Focus on the mood you want to create.

*Give your character tunnel vision, shutting out everything but the imminent threat.

You can also increase the pacing of your novel through plot devices: using red herrings to create false leads, supporting the main threat with a number of smaller threats that can be resolved, including a time constraint (two minutes to diffuse a bomb), increasing your protagonist's obstacles, raising the stakes, killing off secondary characters.

Pacing issues are systemic, meaning they affect the entire book, so take your time and focus on fixing them. Readers won't continue turning pages if the pacing is off, whether too fast or too slow. Too fast, and you lose emotional connectivity with the reader. Too slow, and you might bore them, make them restless. One of the best ways to develop an ear for pacing is to read voraciously with a keen eye as to your reaction to other books' pacing. Then internalize what you have learned and apply it to your book.

Talented author Lee Child shares the following advice on pacing: make the fast parts slow and the slow parts fast. Advice from a pro that we should all live by. Thanks for joining us today. Would love to hear how a book's pacing affecting your impression of the read.

Published on September 24, 2016 17:30

September 22, 2016

FIRST, POUR THE COFFEE

S. Lee Manning: I’m starting a blog on writing tips by telling you to pour yourself a cup of coffee. You may think it’s because I’m a coffee addict. (I am.) Or that I’m suggesting I need coffee to get my brain working in the morning. (I do.) But there’s also a more important reason.

I pour the coffee first because this is the first step in my morning routine, because it’s what for want of a better word, I would call a habit. And habits and routines are important – in life, and in writing.

I pour the coffee first because this is the first step in my morning routine, because it’s what for want of a better word, I would call a habit. And habits and routines are important – in life, and in writing.

As Gayle Lynds noted in her blog on writing tips, writing a novel is ten percent inspiration and ninety percent perspiration. I’ve read other writers who emphasize the importance of just getting your butt in the chair and writing. Sounds so simple. Why is it so hard?

I don’t know why. But it is hard. There’s days when that butt just doesn’t want to go in that chair. There’s days when I want to go out shopping and then check out the cheese grits for lunch at the new little restaurant in Montpelier. Or take a long bike ride. Or read a new book. Or watch the latest in the political spectacle that’s happening this year. Or, I don’t know, try baking French baguettes that resemble the bread I bought in Nice and Avignon at 10 p.m. each night. (Yeah, I know, don’t even bother on this one.)

That’s where the coffee comes in for me.

Every morning, I get up around 7 a.m, feed the cats, pour myself a cup of coffee, and watch the news for twenty minutes until the morning caffeine deprivation headache goes away (I already admitted that I’m an addict). Then I pour myself another cup of coffee and head for my desk and my computer.

I do a quick skim of my e-mails and Facebook, maybe write a post or two, and then I get into the writing. I start with reviewing what I wrote the previous day. I delete a little, add a little, and then I move on to a new scene.

I’m allowed to peek at Facebook now and then, but I’ve had to break the habit of spending too much time there – presenting arguments that will change no one’s mind and just waste my time. This was a tough one to break – I’m a lawyer by training – and I like to argue. But, I’ve stopped this habit. For the most part. Sort of.

Except for a few excursions to the kitchen for more coffee and occasionally food to keep my stomach from rotting (all the coffee), I stay at my desk until close to noon. Then I break for lunch with my husband and consider the possibility of an afternoon excursion. I may or may not write through the afternoon – but it’s an extra, not part of the routine. Sometimes, I do get so engrossed by the writing that I don’t want to stop. But it’s not something I can count on every day. For every day, I have the routine.

Sounds like work, huh? Because it is.

When I was an editor on Law Enforcement Communications, a magazine for police officers, doing what I had always wanted to do – there were days I didn’t want to write an article – no matter how interesting. I had to force myself. I complained about my occasional lack of enthusiasm to my father, who was a wise man. He told me that anything you have to do everyday, even if you think you love what you do, will sometimes just feel like work. That’s why it’s called work.

To get through work, I created routines and habits. It’s the same with writing – which is now my work.

Research suggests that creating a new habit can take anywhere from twenty-one days to eight months. It requires persistence and consistency. Create the routine and stick to it. Every day – or every work day, if you want to take weekends off. You can have the occasional sick day or vacation day, as with any other job, otherwise follow the program. Pour the coffee and sit down at the desk. Start. And while there will be times when the writing comes easily and inspirationally, there will be other days – days when it feels forced or painful. There are days when I hate what I’ve written. Still I know that the next day, I will pour a cup of coffee, sit down, and rework it – until I have a scene and then a chapter and then fifty chapters that I love. It will take days and weeks and months of following the routine to get there, but when I do, it’s worth all the work.

Coffee anyone?

I pour the coffee first because this is the first step in my morning routine, because it’s what for want of a better word, I would call a habit. And habits and routines are important – in life, and in writing.

I pour the coffee first because this is the first step in my morning routine, because it’s what for want of a better word, I would call a habit. And habits and routines are important – in life, and in writing.As Gayle Lynds noted in her blog on writing tips, writing a novel is ten percent inspiration and ninety percent perspiration. I’ve read other writers who emphasize the importance of just getting your butt in the chair and writing. Sounds so simple. Why is it so hard?

I don’t know why. But it is hard. There’s days when that butt just doesn’t want to go in that chair. There’s days when I want to go out shopping and then check out the cheese grits for lunch at the new little restaurant in Montpelier. Or take a long bike ride. Or read a new book. Or watch the latest in the political spectacle that’s happening this year. Or, I don’t know, try baking French baguettes that resemble the bread I bought in Nice and Avignon at 10 p.m. each night. (Yeah, I know, don’t even bother on this one.)

That’s where the coffee comes in for me.

Every morning, I get up around 7 a.m, feed the cats, pour myself a cup of coffee, and watch the news for twenty minutes until the morning caffeine deprivation headache goes away (I already admitted that I’m an addict). Then I pour myself another cup of coffee and head for my desk and my computer.

I do a quick skim of my e-mails and Facebook, maybe write a post or two, and then I get into the writing. I start with reviewing what I wrote the previous day. I delete a little, add a little, and then I move on to a new scene.

I’m allowed to peek at Facebook now and then, but I’ve had to break the habit of spending too much time there – presenting arguments that will change no one’s mind and just waste my time. This was a tough one to break – I’m a lawyer by training – and I like to argue. But, I’ve stopped this habit. For the most part. Sort of.

Except for a few excursions to the kitchen for more coffee and occasionally food to keep my stomach from rotting (all the coffee), I stay at my desk until close to noon. Then I break for lunch with my husband and consider the possibility of an afternoon excursion. I may or may not write through the afternoon – but it’s an extra, not part of the routine. Sometimes, I do get so engrossed by the writing that I don’t want to stop. But it’s not something I can count on every day. For every day, I have the routine.

Sounds like work, huh? Because it is.

When I was an editor on Law Enforcement Communications, a magazine for police officers, doing what I had always wanted to do – there were days I didn’t want to write an article – no matter how interesting. I had to force myself. I complained about my occasional lack of enthusiasm to my father, who was a wise man. He told me that anything you have to do everyday, even if you think you love what you do, will sometimes just feel like work. That’s why it’s called work.

To get through work, I created routines and habits. It’s the same with writing – which is now my work.

Research suggests that creating a new habit can take anywhere from twenty-one days to eight months. It requires persistence and consistency. Create the routine and stick to it. Every day – or every work day, if you want to take weekends off. You can have the occasional sick day or vacation day, as with any other job, otherwise follow the program. Pour the coffee and sit down at the desk. Start. And while there will be times when the writing comes easily and inspirationally, there will be other days – days when it feels forced or painful. There are days when I hate what I’ve written. Still I know that the next day, I will pour a cup of coffee, sit down, and rework it – until I have a scene and then a chapter and then fifty chapters that I love. It will take days and weeks and months of following the routine to get there, but when I do, it’s worth all the work.

Coffee anyone?

Published on September 22, 2016 21:30

September 20, 2016

WANT TO WRITE A NOVEL?

Me in my book-filled Santa Barbara office.By Gayle Lynds. Years ago a brain surgeon whom I met at a party told me in all seriousness that when he retired he was going to be a novelist. My reply? “When I retire, I’m going to be a brain surgeon.” Oh, dear. Did I really say that?

Me in my book-filled Santa Barbara office.By Gayle Lynds. Years ago a brain surgeon whom I met at a party told me in all seriousness that when he retired he was going to be a novelist. My reply? “When I retire, I’m going to be a brain surgeon.” Oh, dear. Did I really say that?As it turns out, I have a long-time friend who’s a brain surgeon and who also writes engrossing medical thrillers. When he finished his latest, he said to me, “I’d rather operate on brains. Writing books is too damn hard.” But still he does it. Why? He laughs: “I think I should have my head examined.”

With this blog, I begin the next series of Rogue Women posts – “Writing Tips.” You won’t want to miss these insightful stories. To get your personal subscription to our blog, just click here.

We’re a peculiar breed, we writers. We work alone. We dream day and night. We come to it in our youth — or perhaps not until our old age. Unlike NFL players, we can have careers that stop only when we die — and maybe not even then if we end up being a Robert Ludlum or a Tom Clancy.

There’s a joke in our trade: “If writing novels were easy, everyone would do it.” That’s how we remind ourselves that the work is not only a great deal of fun and challenging, it’s also relentless. If we’re to be good at it, we never stop teaching ourselves. But then, that’s part of the joy. My friend who is both a surgeon and a novelist has spent his life studying and working at both, switching back and forth between periods when he writes, and those in which he’s in the hospital operating.

I like to comfort beginning novelists with a couple of statistics: On the average, from the time a person commits himself or herself to becoming good enough to be traditionally published — figure ten years. On the average, a writer writes four full-length novels before one is finally good enough to be traditionally published. More brain surgeons in this country make a living than do novelists.

Are you depressed? Don’t be. As a beginner, I was relieved to know the hill was long and challenging. The reason was that as I was growing up, I’d believed the books and movies that told us that all you had to do was write a book and it’d automatically be published and you’d be rich, famous, and have a long career ahead of you. But then, we’re a highly literate society (thank goodness), and that sometimes makes us believe that if we can read books, we ought to be able to write them. The truth is, that’s mostly true — but it also takes a lot of talent and work.

If you’re thinking about writing, or perhaps you’ve already started to write stories, keep going. You don’t have to publish. You’re also entitled to the joy and satisfaction of writing simply for yourself or for your family and friends. If you write, you’re a writer.

But if you want to be published, here are two tips:

● Books aren’t written, they’re rewritten.

● Writing is 10 percent inspiration and 90 percent perspiration.