Theodora Goss's Blog, page 16

July 25, 2015

Teaching at Stonecoast I

I’m recovering from the Stonecoast summer residency. What, you may ask, is Stonecoast? And what is a residency? Stonecoast is the MFA program in which I teach, and the residency is a ten-day period when all the students and faculty get together, twice a year, for workshops, seminars, and readings. It’s the most intense teaching I do, and I love it.

For those of you who are interested, I thought I would describe what it’s like teaching in one of the top low-residency programs in the country, and one of only a few that have a Popular Fiction track. That’s what I teach: Popular Fiction. My students write science fiction, fantasy, mystery . . . And of course they also write literary fiction, poetry, essays. Being on the Popular Fiction track doesn’t prevent you from writing, or taking workshops in, other modes or genres. But most of what I do in the program tends to focus on popular genres, in one way or another — or the places where genres intersect.

So what was I doing, exactly? Well, first I had to prepare for the residency. That meant reading and commenting on the stories from the two workshops I would be leading. The first half of the residency, I would be leading a workshop for the newly-admitted students, which would prepare them for workshopping at Stonecoast in general. It would be both workshop and orientation. I’d never done that before, so I was particularly looking forward to it. The second half, I would be co-leading a workshop focused specifically on writing short fiction with James Patrick Kelly. Now, Jim Kelly is a friend and mentor of mine — he was my own teacher at Clarion! So you can imagine how much I was looking forward to that. I would be co-teaching with my own teacher! Also, Jim is a fantastic writer of short fiction as well as a fantastic teacher in general, so I knew that I would be learning as much as I would be teaching. During the residency, I would also be giving a presentation called Magical Realism: Theory and Practice. So I created a PowerPoint, and a series of presentation notes for myself, and a reading list to hand out. Here you can see the slides from my PowerPoint presentation, which I printed out so I could proofread them:

The presentation took a lot of work, because I am not an expert on Magical Realism. As I told the students, there are things I am genuinely an expert on, because I’ve studied them intensively for years. But Magical Realism is not within my field of expertise. That’s what made doing a presentation so exciting: I had to learn about a whole new field! Of course I’d studied it a little, starting with a class on magical realist fiction in college. But I had a lot of reading to do before I could present on the topic in any coherent way. That took a couple of months! By the time I started preparing for the residency in earnest, I had enough of a background to put together my presentation — more or less confidently. So that was most of the preparatory work. I also knew I’d need to prepare a 20-minute reading, but I’d recently written a story that I wanted to read . . . so that was taken care of.

The residency took place on the campus of Bowdoin College, in Brunswick, Maine.

If you’ve never been on the campus of Bowdoin, I will tell you that it’s ridiculously beautiful. You can just take a look at the pictures here! It looks exactly the way you would expect a New England liberal arts college to look, all green campus and stone or brick buildings. First, of course, I had to get there. I’m lucky in that I live in the Northeast, where it’s easy to get around by train. I took the Amtrak Downeaster up to Brunswick and walked from the station to the inn where faculty members were staying. For ten days, my room at the inn would be my home. I unpacked, putting clothes away, hanging blouses and dresses from the hangers — if you move in, I’ve found, you feel much more at home, even in a hotel room. And then I went shopping for supplies. Of course I could have ordered breakfast at the inn, but I found it so much easier to buy cups of oatmeal and powered chai, so that, with only the coffee maker in my room, I could make myself oatmeal and chai in the mornings. Also cereal bars and chocolate, in case I got hungry during the day — because if I get hungry, I get cranky.

So there I was, with my clothes put away, my manuscripts ready, my supplies purchased. Time to start the residency.

The residency day starts at 8:15, with graduating student presentations. This summer, I had a graduating student whom I had mentored — I had been the first reader on her thesis, and had guided her through the thesis process. Her presentation was one of the first, and I was so pleased to see how well it went, how smart it was. For her third-semester project, she had researched the history of monsters, and in her presentation she explained how conceptions of monsters had changed, from the mythical monsters, to the medieval, to the modern (particularly post-World War II). Then, after student presentations, we have workshops for two and a half hours. With my first-semester students, we generally workshopped one story, took a break, workshopped a second story, and then went on to talk about particular writing issues. I had brought a handout that included a variety of passages — for example, I’d just started reading Patrick Süskind ‘s Perfume: The Story of a Murderer, and I included the first two paragraphs, in which he describes the stench of 18th century Paris. It’s a brilliant description, a brilliant and unconventional way to start a novel. We talked about the choice of words and images, the way the author directs our attention (always conscious of the fact that we were dealing with a translation from the German).

After workshop, we had lunch, all of us together in the Bowdoin cafeteria. And then in the afternoon there were faculty presentations. After those, there was other programming, typically graduating student readings but also orientations of various sorts, such as for students going to the Ireland residency (yes, Stonecoast has an optional Ireland residency! Send me to Ireland, Stonecoast . . .). Then it was time for dinner, and then faculty readings. So the days ended at around 8:15 p.m., unless there was something even after that, like student open-mic’s. Yes, I know, twelve-hours days! That’s what a residency is like . . .

I’ve written so much already, and I haven’t really even started to describe what I did at the residency! I’ll have to write another blog post on this subject. In the meantime, here is me, sitting in one of the rocking chairs on the inn porch, going over manuscripts . . .

July 24, 2015

Autumn’s Song

Autumn’s Song

by Theodora Goss

You are not alone.

If they could, the oaks would bend down to take your hands,

bowing and saying, Lady, come dance with us.

The elder bushes would offer their berries to hang

from your ears or around your neck.

The wild clematis known as Traveler’s Joy

would give you its star-shaped blossoms for your crown.

And the maples would offer their leaves,

russet and amber and gold,

for your ball gown.

The wild geese flying south would call to you, Lady,

we will tell your sister, Summer, that you are well.

You would reply, Yes, bring her this news —

the world is old, old, yet we have friends.

The squirrels gathering nuts, the garnet hips

of the wild roses, the birches with their white bark.

You would dress yourself in mist and early frost

to tread the autumn dances — the dance of fire

and fallen leaves, the expectation of snow.

And when your sister Winter pays a visit,

You would give her tea in a ceramic cup,

bread and honey on a wooden plate.

You would nod, as women do, and tell each other,

The world is more magical than we know.

You are not alone.

Listen: the pines are whispering their love,

and the sky herself, gray and low, bends down

to kiss you on both cheeks. Daughter, she says,

I am always with you. Listen: my winds are singing

autumn’s song.

Above you will see a video based on my poem created by Belinda Farage. I thought it was so gorgeous that I wanted to share it here . . . This poem is in my poetry collection, Songs for Ophelia.

July 5, 2015

Ordinary Pleasures

Last summer, I spent a month in Budapest, taking a class in Hungarian. This summer, I organized my taxes.

I’m not kidding, I really did organize my taxes. It’s such a relief, having all that paperwork organized into individual folders, appropriately labeled. I know, it’s a lot less exotic than flying to Budapest. But this summer has been about trying to catch up on all the ordinary things that, to be honest, I’ve neglected. I’ve lived in my apartment for a year, and it’s still not entirely decorated. Granted, decorating takes a while, at least the way I do it, but still . . . I’d like to have a nice place to live in. And that takes putting in the time, doing the work. So this summer is about doing the ordinary things: working, organizing, catching up.

What I’ve found, staying in Boston this summer, is the pleasure of the ordinary. The pleasure, for example, of watching the procession of flowers. Luckily, I live in the midst of gardens: there are gardens in front of the brownstones all up and down my street, more formal gardens in city squares or close to children’s playgrounds, and even conservation areas where I can go for walks beside rivers or ponds, under tall trees. Just now the roses and clematis are almost over, although this week I still found some perfect roses in a formal rose garden not too far from me. This was one of them:

The lilies have started blooming, and the linden trees are in flower. I’m lucky to live on a street with linden trees, so I can smell the sweet odor every time I step outdoors. It seems to fall from the trees . . . Every time one type of flower fades, I feel sad because it means that summer is passing. But at the same time, it’s fascinating to see them, like the best fashion show ever. Nothing we create is as beautiful as the flowers. Mother Nature is, after all, the greatest artist. And I love walking around the city, looking at the old buildings with their beautiful details. Architecture lost both beauty and detail for a while — we were poorer for that, and are just starting to find those two things again.

What we really lost, I think, is the understanding that beauty and joy come from the small, the ordinary. Take those enormous contraptions of steel and glass created by the most famous contemporary architects. They are rarely beautiful, and they rarely give us joy. If we got rid of every single one of them, it would not impact our lives in a significant way. Compare them to a honeybee, so small and intricate. Isn’t the bee more beautiful? And if we got rid of every single one of them . . . well then, we’d be in trouble.

I don’t know what happened to our sense of the small and ordinary, but I think we need to get it back. Recently, I started watching a television show from the 1960s, and I was startled by how small things were: hotel rooms, women’s clothes, international crime syndicates. (All right, if you must know, it’s Mission Impossible. I love watching a show that is almost pure plot . . .) There are ways in which we live in a better world. No Cold War, for one. But I think as we progress, we always lose something. In this case, at least, I think we can get it back.

After I went to the rose garden, I walked to the conservancy I mentioned, which is a wetland. There is a path through the woods . . . (I thought this would be a good place for a metaphor.)

We can make a conscious decision to reclaim the small, the ordinary. We can care more about honeybees than skyscrapers. Knitting than international finance. (Don’t get me wrong: you should try to understand international finance. We need to understand what is being done to our world, if only because voting intelligently is one of those small things that make a large impact, like honeybees.) We can learn to cook or play an instrument. We can organize our taxes. Clean our bathrooms. (That’s on the agenda for today.) There is so much meaning in those small acts, and the truth is, when we do something large, the meaning of it usually comes from the small components anyway. If we write a novel, the meaning comes from all those hours we spent at our computer, trying to find the right word. From each edit. From the lessons we learned about ourselves while writing.

Aren’t the ferns gorgeous? I had to take a picture of them as I walked through the forest. It was like walking through a green world, made up of all the small things: beech leaves rustling overhead, white trunks of birches, ferns by the path, rabbits hopping under the bushes, looking at me as though wondering what I was doing in their living room, and the magnificent blue heron that was standing in the pond, with a blue heron reflected in the pond water beneath him. I thought, I’d like to have something like this, a connection of this sort, every day of my life.

Then I went home and did the small things there: made dinner, finished some sewing I’d been putting off for a while, intimidated as always by my sewing machine because tension is so complicated . . . but no, my Singer behaved perfect. And then I did something I’m really quite proud of: I figured out how to use my new mat cutting board and cut some mats. It took a while to get used to, but look:

That’s a small card by the artist Virginia Lee, of a weeping Onion Man. I found the square frame at Goodwill, and I thought, it will be too small. But with a one-inch mat, it fit the picture quite well. (I had to cut the mat twice. The trick, I found, is to use a real mat board under the mat board you’re cutting, rather than the cardboard included with your mat cutter.) Virginia gave me the card when I visited her village, in England. So I’m not saying don’t do the large things — I would not have missed my trip to England for the world. But remember to do the small ones, because those are where we mostly find meaning . . . and joy.

June 29, 2015

Snow White Learns Witchcraft

Snow White Learns Witchcraft

by Theodora Goss

One day she looked into her mother’s mirror.

The face looking back was unavoidably old,

with wrinkles around the eyes and mouth. I’ve smiled

a lot, she thought. Laughed less, and cried a little.

A decent life, considered altogether.

She’d never asked it the fatal question that leads

to a murderous heart and red-hot iron shoes.

But now, being curious, when it scarcely mattered,

she recited Mirror, mirror, and asked the question:

Who is the fairest? Would it be her daughter?

No, the mirror told her. Some peasant girl

in a mountain village she’d never even heard of.

Well, let her be fairest. It wasn’t so wonderful

being fairest. Sure, you got to marry the prince,

at least if you were royal, or become his mistress

if you weren’t, because princes don’t marry commoners,

whatever the stories tell you. It meant your mother,

whose skin was soft and smelled of parma violets,

who watched your father with a jealous eye,

might try to eat your heart, metaphorically —

or not. It meant the huntsman sent to kill you

would try to grab and kiss you before you ran

into the darkness of the sheltering forest.

How comfortable it was to live with dwarves

who didn’t find her particularly attractive.

Seven brothers to whom she was just a child, and then,

once she grew tall, an ungainly adolescent,

unlike the shy, delicate dwarf women

who lived deep in the forest. She was constantly tripping

over the child-sized furniture they carved

with patterns of hearts and flowers on winter evenings.

She remembers when the peddlar woman came

to her door with laces, a comb, and then an apple.

How pretty you are, my dear, the peddlar told her.

It was the first time anyone had said

that she was pretty since she left the castle.

She didn’t recognize her. And if she had?

Mother? She would have said. Mother, is that you?

How would her mother have answered? Sometimes she wishes

the prince had left her sleeping in the coffin.

He claimed he woke her up with true love’s kiss.

The dwarves said actually his footman tripped

and jogged the apple out. She prefers that version.

It feels less burdensome, less like she owes him.

Because she never forgave him for the shoes,

red-hot iron, and her mother dancing in them,

the smell of burning flesh. She still has nightmares.

It wasn’t supposed to be fatal, he insisted.

Just teach her a lesson. Give her blisters or boils,

make her repent her actions. No one dies

from dancing in iron shoes. She must have had

some sort of heart condition. And after all,

the woman did try to kill you. She didn’t answer.

And so she inherited her mother’s mirror,

but never consulted it, knowing too well

the price of coveting beauty. She watched her daughter

grow up, made sure the girl could run and fight,

because princesses need protecting, and sometimes princes

are worse than useless. When her husband died,

she went into mourning, secretly relieved

that it was over: a woman’s useful life,

nurturing, procreative. Now, she thinks,

I’ll go to the house by the seashore where in summer

we would take the children (really a small castle),

with maybe one servant. There, I will grow old,

wrinkled and whiskered. My hair as white as snow,

my lips thin and bloodless, my skin mottled.

I’ll walk along the shore collecting shells,

read all the books I’ve never had the time for,

and study witchcraft. What should women do

when they grow old and useless? Become witches.

It’s the only role you get to write yourself.

I’ll learn the words to spells out of old books,

grow poisonous herbs and practice curdling milk,

cast evil eyes. I’ll summon a familiar:

black cat or toad. I’ll tell my grandchildren

fairy tales in which princesses slay dragons

or wicked fairies live happily ever after.

I’ll talk to birds, and they’ll talk back to me.

Or snakes — the snakes might be more interesting.

This is the way the story ends, she thinks.

It ends. And then you get to write your own story.

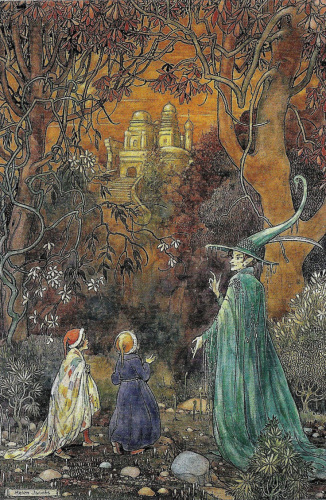

This image is The Enchanted Wood by Helen Jacobs.

I’ve decided to try something: uploading a new poem of mine every once in a while. I hope you like this one . . . And if you find that you like my poetry, you can read more in my poetry collection, Songs for Ophelia.

Poem: Snow White Learns Witchcraft

Snow White Learns Witchcraft

by Theodora Goss

One day she looked into her mother’s mirror.

The face looking back was unavoidably old,

with wrinkles around the eyes and mouth. I’ve smiled

a lot, she thought. Laughed less, and cried a little.

A decent life, considered altogether.

She’d never asked it the fatal question that leads

to a murderous heart and red-hot iron shoes.

But now, being curious, when it scarcely mattered,

she recited Mirror, mirror, and asked the question:

Who is the fairest? Would it be her daughter?

No, the mirror told her. Some peasant girl

in a mountain village she’d never even heard of.

Well, let her be fairest. It wasn’t so wonderful

being fairest. Sure, you got to marry the prince,

at least if you were royal, or become his mistress

if you weren’t, because princes don’t marry commoners,

whatever the stories tell you. It meant your mother,

whose skin was soft and smelled of parma violets,

who watched your father with a jealous eye,

might try to eat your heart, metaphorically —

or not. It meant the huntsman sent to kill you

would try to grab and kiss you before you ran

into the darkness of the sheltering forest.

How comfortable it was to live with dwarves

who didn’t find her particularly attractive.

Seven brothers to whom she was just a child, and then,

once she grew tall, an ungainly adolescent,

unlike the shy, delicate dwarf women

who lived deep in the forest. She was constantly tripping

over the child-sized furniture they carved

with patterns of hearts and flowers on winter evenings.

She remembers when the peddlar woman came

to her door with laces, a comb, and then an apple.

How pretty you are, my dear, the peddlar told her.

It was the first time anyone had said

that she was pretty since she left the castle.

She didn’t recognize her. And if she had?

Mother? She would have said. Mother, is that you?

How would her mother have answered? Sometimes she wishes

the prince had left her sleeping in the coffin.

He claimed he woke her up with true love’s kiss.

The dwarves said actually his footman tripped

and jogged the apple out. She prefers that version.

It feels less burdensome, less like she owes him.

Because she never forgave him for the shoes,

red-hot iron, and her mother dancing in them,

the smell of burning flesh. She still has nightmares.

It wasn’t supposed to be fatal, he insisted.

Just teach her a lesson. Give her blisters or boils,

make her repent her actions. No one dies

from dancing in iron shoes. She must have had

some sort of heart condition. And after all,

the woman did try to kill you. She didn’t answer.

And so she inherited her mother’s mirror,

but never consulted it, knowing too well

the price of coveting beauty. She watched her daughter

grow up, made sure the girl could run and fight,

because princesses need protecting, and sometimes princes

are worse than useless. When her husband died,

she went into mourning, secretly relieved

that it was over: a woman’s useful life,

nurturing, procreative. Now, she thinks,

I’ll go to the house by the seashore where in summer

we would take the children (really a small castle),

with maybe one servant. There, I will grow old,

wrinkled and whiskered. My hair as white as snow,

my lips thin and bloodless, my skin mottled.

I’ll walk along the shore collecting shells,

read all the books I’ve never had the time for,

and study witchcraft. What should women do

when they grow old and useless? Become witches.

It’s the only role you get to write yourself.

I’ll learn the words to spells out of old books,

grow poisonous herbs and practice curdling milk,

cast evil eyes. I’ll summon a familiar:

black cat or toad. I’ll tell my grandchildren

fairy tales in which princesses slay dragons

or wicked fairies live happily ever after.

I’ll talk to birds, and they’ll talk back to me.

Or snakes — the snakes might be more interesting.

This is the way the story ends, she thinks.

It ends. And then you get to write your own story.

This image is The Enchanted Wood by Helen Jacobs.

I’ve decided to try something: uploading a new poem of mine every once in a while. I hope you like this one . . . And if you find that you like my poetry, you can read more in my poetry collection, Songs for Ophelia.

June 27, 2015

Heroine’s Journey: Temptations and Trials

I was so busy last week that I didn’t have time to write a blog post. At the moment I’m trying to finish putting together a new short story collection, and also preparing for the Stonecoast residency, where I will be teaching for ten days. I’ve found that unless I sit down, first thing on Saturday morning, and write a blog post, I just won’t get it done. So here goes . . .

This week, I’m going to write about the temptations and trials of the fairy tale heroine. Just as a reminder, here are the steps on the fairy tale heroine’s journey:

1. The heroine receives gifts.

2. The heroine leaves or loses her home.

3. The heroine enters the dark forest.

4. The heroine finds a temporary home.

5. The heroine finds friends and helpers.

6. The heroine learns to work.

7. The heroine endures temptations and trials.

8. The heroine dies or is in disguise.

9. The heroine is revived or recognized.

10. The heroine finds her true partner.

11. The heroine enters her permanent home.

12. The heroine’s tormentors are punished.

You can see these steps in a variety of fairy tales focused on a heroine’s journey from childhood to adulthood — a distinct subset of tales. Obviously, not all tales about heroines follow this pattern — some are not journey tales at all. I’m talking about a specific type of fairy tale, which I’ve discussed before in my posts on this subject.

The temptations and trials are a distinct phase of the fairy tale heroine’s journey, and they are two separate things: temptations, trials. Cinderella undergoes a trial when she has to become a servant in her own home. Snow White gives in to temptation when she lets the old pedlar woman in, tempted by the stay laces, comb, and apple. Trials happen to you, and must be endured. Temptations are offered to you, and must be resisted.

I’m particularly interested in the temptations in “Snow White”: as a number of scholars have pointed out, they represent the sort of mature beauty that the Wicked Queen has and Snow White is just coming into. Stay laces will make her waist smaller, accentuating her womanly figure. A comb will make her hair, in the 19th century called a woman’s crowning glory, straighter, neater. It will also allow her to dress her hair. These items will allow Snow White to become what her society considers a woman. They are temptations to feminine vanity, but also the natural desire to grow up. The apple is an important symbol in Western art and literature in two ways: it’s the apple of Eve, but also the apple of Discord with the words “to the fairest” written on it. It’s the apple fought over by Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite, the apple that led to the Judgement of Paris and the Trojan War — which was of course about who gets the most beautiful woman in the world.

So Snow White’s temptations are important and symbolically freighted. The real temptation isn’t a set of laces, or a comb, or even an apple. The real temptation is becoming the Wicked Queen, with her desires and values. The fairy tale makes us wonder: how do you become a mature woman without being tempted by the image society wants you to fit, the role it wants you to fulfill? How does Snow White grow up without becoming the Wicked Queen? In her poem on the fairy tale, Anne Sexton implies that she really can’t — her world doesn’t offer her enough possibilities. She will always be trapped in the mirror, subject to its judgments. Two of my favorite scholars, Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar, who have written an important essay on this fairy tale, say the same thing: the tale is circular, with Snow White inevitably becoming either the Dead Queen (her own mother) or the Wicked Queen. Is there another way? The fairy tale implies there is, but at least in the Grimm version, it doesn’t give us a sense of what that other way might be.

There is another type of tale in which temptation becomes particularly important: the “lost husband” tale, such as “Cupid and Psyche,” said to be the origin of “Beauty and the Beast.” In tales of that type, the heroine is tempted to see her husband’s true form, for during the day he appears as snake or bear, or some other loathsome beast, but during the night he is a man. She gives in to temptation, and that is when her trials begin: the husband disappears, and she must go on a quest to find him again.

Trials appear even more frequently in fairy tales than temptations. There is the trial of endurance: Cinderella, Donkeyskin, and Vasilisa must all endure being treated like servants. Sleeping Beauty, after giving in to the temptation of touching the spindle, endures her long sleep. The heroine of “Six Swans” endures the trial of making shirts for her swan brothers, while resisting the temptation of speaking to save herself. And there are trials that are quests: in “East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon,” the heroine must go on a quest to save her bear-husband from trolls. Heroines must wear out pairs of iron shoes, walk up glass mountains, outwit ogres . . . Gerda’s temptation is staying in the old woman’s flower garden, and one of her trials is facing the robbers, including the fierce little robber girl. She walks all the the way to the Snow Queen’s castle to save Kai. We can call what Andersen was writing fairy tales, even when his tales have no oral predecessor, because they honor these old templates, these paths of story. They do not always follow them, but they are always cognizant of them.

So what does this mean for us, heroines of our own fairy tales? It means that we will endure temptations and trials. I think that’s a useful acknowledgement to make. First, it allows us to anticipate them: yes, this is a temptation; yes, now I am undergoing a trial. It’s not that the universe has gone off its rails, it’s not that everything is wrong at its core. Temptations and trials are part of the pattern. It allows us to identify them: yes, I’m tempted to buy a new dress, but I need to save money; yes, I’m not happy at work, but at least for now I’ll need to endure it, because it’s helping me through school . . . that sort of thing. It allows us to formulate responses: why am I enduring temptations and trials? Well, because I’m the heroine of my own tale, and this is what happens to heroines.

Just remember that the temptations and trials are integral to the story. They are also integral to your growth. Your temptations can teach you a lot about yourself: what particularly tempts you? And why? Remember that Snow White’s temptations were also warnings: something in you wants to be like the Wicked Queen. I should point out here that temptations are not always wrong. Snow White wants and needs to grow up: her temptations are at least partly about that process of growth. Only after biting the apple can she become an adult. Sleeping Beauty is tempted by the spindle, and giving in to that temptation leads to her long sleep, necessary to her maturation. Rapunzel is tempted by the prince, and gives in rather easily! She is punished, but her punishment is also her liberation. She needs to be banished from the tower of childhood, to make her own way in the world.

And trials . . . it’s useful to remember that trials make you stronger, and smarter. Sometimes you have to endure, but sometimes you have to act, and it’s important to know the difference. Cinderella can endure, but Donkeyskin must leave her situation — her father’s incestuous desires make her home uninhabitable. Beauty must live with the Beast before she can meet her prince. During trials, you learn skills and principles that can serve you well in both fairy tales and life. The Goose Girl learns to herd geese, but more importantly learns what it’s like to be a servant. Hopefully, that will make her a better queen. Fairy tale heroines on quests learn to follow directions, be kind, keep going. These are all useful principles. And you can only really learn them the hard way . . .

(This illustration is “The Faery Prince” by Adolf Adolf Münzer.)

Here are my previous posts on the fairy tale heroine’s journey:

The Heroine’s Journey

Heroine’s Journey: Snow White

Heroine’s Journey: Sleeping Beauty

Heroine’s Journey: Receiving Gifts

Heroine’s Journey: The Goose-Girl

The Heroine’s Journey II

Heroine’s Journey: The Dark Forest

Heroine’s Journey: Learning to Work

Heroine’s Journey: A Temporary Home

Heroine’s Journey: Leaving Home

June 13, 2015

Heroine’s Journey: Leaving Home

I’m going back a bit. As you may remember, the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey looks like this:

1. The heroine receives gifts.

2. The heroine leaves or loses her home.

3. The heroine enters the dark forest.

4. The heroine finds a temporary home.

5. The heroine finds friends and helpers.

6. The heroine learns to work.

7. The heroine endures temptations and trials.

8. The heroine dies or is in disguise.

9. The heroine is revived or recognized.

10. The heroine finds her true partner.

11. The heroine enters her permanent home.

12. The heroine’s tormentors are punished.

So far I’ve covered receiving gits, entering the dark forest, finding a temporary home, and learning to work. But I never dealt with that initial leaving or loss of home. Perhaps it’s too personal? This month, I’m putting together my second short story collection: gathering all the stories to be included, editing them, and writing a new one. That new one is probably the most autobiographical story I’ve ever written. And I’m finding it very hard to write, in part because it’s about loss. My childhood was a series of losses: when we left Hungary (I was five), I lost both my country and most of my family. Then we left Belgium, so I lost that country as well. Two languages lost: Hungarian and French. Even in the United States, we kept moving, so I don’t have a childhood friend I still keep in touch with. I lost them all.

I left my home and I lost my home, which may be one reason why fairy tales resonate with me. They are so much about leaving or losing home. Consider: Snow White leaves her home for the dark forest and loses it when she realizes the Wicked Queen is trying to kill her. Donkeyskin must leave her home because it is no longer a safe place: her father wants to marry her. The heroine of “Six Swans” is threatened by an evil stepmother, so she leaves too, for the dark forest. There are heroines who leave to be married, only to find out that marriage isn’t what they thought it would be: the Goose Girl leaves her home to be married to a king, but loses her identity in the dark forest and becomes a servant, for a while. The heroine of “East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon” also leaves, to marry a bear. And that leaving is also a loss — when she does come home to visit, her mother advises her to spy on her bear husband, which leads to his disappearance and her long quest. Beauty loses her home when her father becomes bankrupt, then leaves her second temporary home to go to the Beast’s castle. Her return home is also dangerous, because she almost forgets him, almost loses him forever.

There are heroines who never leave home, but nevertheless lose it: Sleeping Beauty stays at home, but when she falls asleep and time passes, it transforms into the dark forest. When she wakes up, it is no longer the home she had: for one thing, in the Charles Perrault version, her parents did not fall asleep with her. They died long ago. She is now an adult and must fend for herself. Cinderella is famous for staying at home, but the home she knew is nevertheless lost to her when her stepmother reduces her to a servant in her own house.

Fairy tales heroines are always leaving or losing their homes. I suppose they have to: you can’t have an adventure if you’re still at home, safe, comfortable. In my class on fairy tales, I ask my students what Cinderella’s story would be like without the cruelty of her stepmother and stepsisters. Once upon a time, Ella’s father married a woman who was as good as she was beautiful, who became like a second mother to Ella. She had two daughters, also good and beautiful, and they loved Ella just as though they were her true sisters. The three girls grew up together, and when they were invited to the ball, her stepmother took her shopping and her stepsisters helped her get dressed. The prince fell in love with her, but her stepsisters were not jealous. Ella married the prince and invited her sisters to live with her in the palace. They all lived happily ever after. The End. My students laugh and are dismayed — we don’t like that story, they say. It’s boring. We can’t relate to it. No one is happy all the time.

They are asking for a heroine who suffers, because we all do, in our own ways. We can’t relate to a heroine who doesn’t. And if she doesn’t, the end becomes meaningless. Who cares if she eventually marries the prince, if she didn’t have to experience oppression and poverty for a while?

There’s a more important reason for leaving and loss in fairy tales, I think. We learn and grow through them. When Vasilisa is sent to Baba Yaga’s hut, she must learn how to fend for herself, respond to Baba Yaga’s anger, use her resources (including the magical doll her mother gave her). She shows her cleverness and also her worthiness — like Donkeyskin or the heroine of “Six Swans.” Donkeyskin responds to adversity by being clever, the heroine of “Six Swans” responds by being virtuous, self-sacrificing. That is how they earn their happy endings. Happy endings that just happen, without loss or distress, feel unearned. I think even in our own lives, we want that sense of having earned something, of having created or participated in our good outcomes. It feels hollow just to be handed “happily ever after.”

That doesn’t negate how horrible it can feel, leaving or losing home, in the real world. But one comfort fairy tales provide is the realization that only afterward can you learn and grow. That’s when the adventure begins. In “The Snow Queen,” Gerda’s quest for Kai is a journey during which she learns about the world, saves what she loves, and proves herself. That’s what we all do on our journeys, I think. Or what we should do . . . Gerda couldn’t do those things without leaving home, venturing out into a strange and dangerous world.

And fairy tales remind you that if you’re feeling a sense of loss, if you’re lost in the dark forest, if you’re surrounded by Wicked Queens or Kings who force you to spin straw into gold, it’s because you’re the heroine, and it’s a journey, and it will get better. And you’ll learn things along the way. Maybe even how to talk to animals . . .

The illustration is attributed to Florence Mary Anderson. Here are my previous posts on the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey:

The Heroine’s Journey

Heroine’s Journey: Snow White

Heroine’s Journey: Sleeping Beauty

Heroine’s Journey: Receiving Gifts

Heroine’s Journey: The Goose-Girl

The Heroine’s Journey II

Heroine’s Journey: The Dark Forest

Heroine’s Journey: Learning to Work

Heroine’s Journey: A Temporary Home

June 6, 2015

Heroine’s Journey: A Temporary Home

I was thinking just yesterday about how much I love my apartment. It’s not large: a one-bedroom in an old brownstone in Boston. But it has four closets plus a storage space, and ten-foot ceilings. I’ve furnished it with pieces I collected over the years, some from thrift or antiques shops that I’ve repainted or refinished, some from unfinished furniture places that I finished myself. The art on the walls was painted by my grandmother or bought by me in galleries or at conventions. Nothing in it is just as it came to me: I’ve changed the drawer pulls on furniture, put new shades on the lamps. Everything in it is very much mine.

Still, it’s a temporary home. I know that I won’t live in it forever. I know there’s another home at some point in the future, already waiting for me. I hope it will be a house with a garden . . .

We all go through a series of temporary homes, which is probably why the temporary home appears in fairy tales as well. Remember the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey, which I’ve been writing about? Here are the steps:

1. The heroine receives gifts.

2. The heroine leaves or loses her home.

3. The heroine enters the dark forest.

4. The heroine finds a temporary home.

5. The heroine finds friends and helpers.

6. The heroine learns to work.

7. The heroine endures temptations and trials.

8. The heroine dies or is in disguise.

9. The heroine is revived or recognized.

10. The heroine finds her true partner.

11. The heroine enters her permanent home.

12. The heroine’s tormentors are punished.

I’ve already written about the heroine receiving gifts, entering the dark forest, and learning to work. Now I want to think a bit about that temporary home. Remember the dwarves’ cottage in “Snow White”: that’s a quintessential temporary home. So what does Snow White do there? Well, first she finds refuge. It’s a safe place to stay for a while, a place she can find another family, a place she can learn to work. But it’s not a refuge for long, because eventually the Wicked Queen does find her, and then she has to endure temptations there, in her temporary home. The temporary home is important in part because it’s not the final home, the place of rest. It’s not where happily ever after happens. It’s still part of the story.

The temporary home does not always look the same in fairy tales. In “Vasilisa the Beautiful,” the temporary home is Baba Yaga’s hut, where Vasilisa must learn to outwit the old witch. It’s a place of work and trials, but also the place where Vasilisa learns what she needs to know, becomes the person who will eventually marry the Tsar. In “Donkeyskin” the temporary home is also the place of trials: Donkeyskin or Catskin or Thousandfurs must travel to a house or castle where she works in the kitchen, performing the most menial tasks. That house or castle is her temporary home, but also the place where she meets the prince. In “East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon,” the heroine marries a bear and goes to his castle, which she thinks will be her permanent home — after all, she’s married and with her husband, right? But when she tries to discover who he truly is, she loses that home. He goes away to marry a troll princess, and she is left in the dark forest. The place she thought was her home disappears around her. The opposite happens in “Beauty and the Beast,” where the castle Beauty comes to, initially so forbidding — the place she’s convinced she’s going to die — ends up being her permanent home. But it can only become the permanent home once she accepts the Beast for who he is. She has to leave it first, go back to her family, almost abandon the Beast, and learn about generosity and love before the castle can become what it’s meant to be.

These are all different ways that the temporary home appears, aren’t they? You’ve reached the place you think is home, where you learn to do productive work and find a place to rest, but then your past catches up with you (“Snow White”). You learn to work in what you think is only a temporary home, but it turns into the permanent home when who you truly are is recognized and appreciated (“Donkeyskin”). You think you’ve found a permanent home, but then you mess up and lose it, and there you are in the dark forest again (“East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon”). You find a home, and leave it, and come back to it after having learned important lessons — only then can it become your permanent home, only then can you recognize it as yours (“Beauty and the Beast”). I think we recognize these patterns in our own lives. We go through them, usually a number of times. Fairy tales are, as I’ve pointed out, reflections of human experience.

The temporary home can also be a prison, as in “Rapunzel.” It can be the place where you’re in stasis, where you can’t grow. The place you have to run away from. In “Cinderella,” the heroine’s first home actually becomes a temporary home when she’s reduced to a servant in it. It’s no longer a home for her–she has lost it without moving out of it.

Do you recognize any of these patterns in your own life? I bet you do . . .

So what lesson can we take from this part of the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey? Throughout our lives, we will go through a series of temporary homes. They may be actual houses or apartments, or metaphorical homes of one kind of another. The important thing is to recognize them as temporary. To not get stuck, or fall into despair at being in a situation when it can end. To know there is a permanent home, although it may be more metaphorical than actual. I think that permanent home is found when we feel at home, when we’re at peace. The permanent home has to be found in us, before it can be found elsewhere. And yes, we can lose it, because this is life and not a fairy tale. Our happily ever afters are always for a while. But I have friends who have found houses or careers they love, where they feel at peace, fulfilled. Where they can say, truly and with conviction, “I have come home.”

As for me? I know this is temporary, but I’m still going to hang paintings, make my apartment as beautiful as possible. I’m still going to enjoy being here, even though I know it’s only part of the journey. My temporary home is where I’m learning, building a career for myself. At the end of the day, I love coming home to my furniture, my books. It may as well be a castle, as far as I’m concerned (though a small one). It may be temporary, but it’s still a home, and I’m going to inhabit it fully.

(The illustration is by William Timlin. I’m not sure what it’s for, but it reminds me of a Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale called “The Shadow.” I just wrote a fairy tale of my own inspired by “The Shadow” for an anthology . . .)

If you want to read the other blog posts in this series, here they are:

The Heroine’s Journey

Heroine’s Journey: Snow White

Heroine’s Journey: Sleeping Beauty

Heroine’s Journey: Receiving Gifts

Heroine’s Journey: The Goose-Girl

The Heroine’s Journey II

Heroine’s Journey: The Dark Forest

Heroine’s Journey: Learning to Work

May 31, 2015

A Forgotten Poet

I’ve been working on a project of mine: Poems of the Fantastic and Macabre. It’s an online anthology of poetry with fantastical elements, from as far back as poetry has been written in what is identifiably “English.” It goes all the way from medieval ballads of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries to modern poetry, by which I mean poetry of the early 20th century. Since the semester ended and I’ve had a little more time, I’ve been adding poetry, and I’ve also updated the design of the site. I’m going to keep working on it, because this is very much a long-term project. I’ll keep adding poets and poems when I can.

Recently I added a poet that particularly interested me. Her name is Ruth Mather Skidmore, and she wrote this poem:

Fantasy

I think if I should wait some night in an enchanted forest

With tall dim hemlocks and moss-covered branches,

And quiet, shadowy aisles between the tall blue-lichened trees;

With low shrubs forming grotesque outlines in the moonlight,

And the ground covered with a thick carpet of pine needles

So that my footsteps made no sound, —

They would not be afraid to glide silently from their hiding places

To the white patch of moonlight on the pine needles,

And dance to the moon and the stars and the wind.

Their arms would gleam white in the moonlight

And a thousand dewdrops sparkle in the dimness of their hair;

But I should not dare to look at their wildly beautiful faces.

Isn’t it beautiful? I found it in an anthology called Poems of Magic and Spells, which sent me back to Walter de la Mare’s anthology Come Hither: A Collection of Rhymes and Poems for the Young of All Ages, which send me back even farther: to an anthology called Off to Arcady : Adventures in Poetry, published in 1933. I very much wanted to include it, but I knew nothing about the poet. And at a minimum, I needed to know when she had been born and when she had died. I needed those dates for the table of contents.

So I went to the internet, expecting to find something. Not necessarily a biographical entry, but something . . . after all, the poem is accomplished. She was obviously a talented poet — surely she had published something else. But for the first time, researching poets for my online anthology, I drew an almost complete blank. She had not published anything else. And she, herself, appeared almost nowhere. I found exactly one reference: in a photocopy of the June 13, 1934 Vassar Miscellany News, I learned that she had graduated from Vassar that spring. Was it the same Ruth Mather Skidmore? There could not be two — the name was too unusual. So I had one small piece of information. I searched again, using various forms of her name, and came across another photocopy. This time it was a page from a local newspaper paper published in Castile, New York called The Castilian, which recorded the social activities of prominent residents. A Mrs. Ruth Mather Skidmore Remsen had visited her mother, Mrs. Ida Mather Skidmore. This must be the same Ruth? And Remsen must be her married name. I couldn’t find the exact date of the newspaper, but it had been printed sometime between 1942 and 1945. On the same page was a list of the specials at Hubbard’s Clover Farm Store: five pounds of cane sugar for 34 cents, a pint of Leadway Floor Wax for 29 cents . . . An advertisement reminded you to Buy War Bonds and Stamps. I was beginning to build a history.

So I searched again, this time for Ida Mather Skidmore, thinking that if I could finedinformation on the previous generation, I might be able to find Ruth’s birthdate. Under her mother’s name, I found an obituary for Ruth’s brother, which told me that he had been predeceased by a sister, Ruth Remsen. So I had been right, that must been her married name. I tried Ruth Remsen as a search term, but there were too many women under that name. I did find an obituary for a Ruth S. Remsen in 2002, but could it be her? I didn’t know. And then I got lucky: I found a wedding announcement for Remsen-Skidmore in The Daily Brooklyn Eagle for July 16th, 1939 — again, a photocopy. That announcement gave me the most information I had found on Ruth Mather Skidmore. Her father had been a Harry B. Skidmore of Elizabeth, New Jersey, and he was described as “the late.” She was a graduate of Vassar Collage, and had spent her Junior year at the Sorbonne. After college, she had gone on to get a Master’s degree at Teachers College, Columbia University. The day before, July 15th, she had married a man named Alfred Soule Remsen, Jr., the son of a Mr. and Mrs. Remsen who lived in Jamaica. He had graduated from the University of Michigan. There was a whole story there, one I wasn’t going to learn more about. Because there was nothing else, at least not online.

I had enough information to call the Vassar Alumni Association, which confirmed that Ruth Skidmore Remsen had been born in 1913 and had died in 2002. And that’s all I know about Ruth Mather Skidmore, the college student whose poem “Fantasy” was published the year before she graduated from college. Who was she, this girl who dreamed of the fair folk in a forest glade? Who wrote at least one fantastical poem, and then . . . nothing else? I have no idea. Perhaps there are more poems somewhere that were not published. Girls who write poetry tend to write more than one, and “Fantasy” is the product of a talented hand and mind.

As far as I can determine, given the confusing state of copyright for poems published around that time, the poem is out of copyright. (If I find that it’s not, I’ll have to remove it or find a descendant who can give me permission.) I’m glad I can reprint it, and that is after all the point of the anthology — to bring attention to poets and poems who may have been forgotten, who may not be getting the attention they deserve. And of course to highlight the long history of fantastical images and themes in poetry.

I’m pretty sure part of what I’m here for is to bring attention to the literature and writers I love. It’s not just about writing — it’s about allowing people to see the world in a different way, whether that is by writing my own poetry or researching and publishing one forgotten poet who wrote at least one wonderful poem.

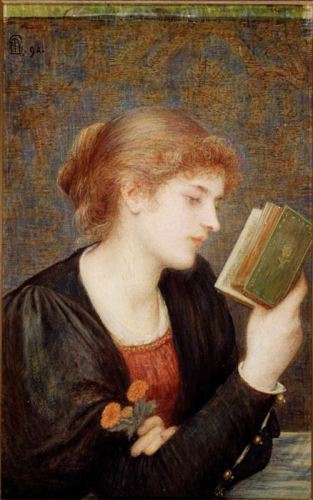

I chose this painting to represent the woman poet. It’s by Marie Spartali Stillman (1844-1927), who would have been alive at the same time as Ruth Mather Skidmore. It’s important to remember the woman artists too . . .

May 17, 2015

Heroine’s Journey: Learning to Work

You may remember that a while ago, I wrote a series of posts about the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey. I was teaching a class on fairy tales (I just finished teaching that class last month), and I realized that there was an underlying pattern to many of the fairy tales I was teaching. I called it The Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey, and in a series of blog posts I starting trying to define it. Based on those posts, I was asked to write about it for Faerie Magazine, and an article of mine called “Into the Dark Forest: The Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey,” was published in the Spring 2015 issue.

Here are the steps in the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey, as I defined them:

1. The heroine receives gifts.

2. The heroine leaves or loses her home.

3. The heroine enters the dark forest.

4. The heroine finds a temporary home.

5. The heroine finds friends and helpers.

6. The heroine learns to work.

7. The heroine endures temptations and trials.

8. The heroine dies or is in disguise.

9. The heroine is revived or recognized.

10. The heroine finds her true partner.

11. The heroine enters her permanent home.

12. The heroine’s tormentors are punished.

Now that classes are over and I have an entire summer to . . . well, catch up on my other work, I thought I would return to defining the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey. I want to map out the entire journey and relate it to a set of fairy tales, probably about twelve total. So this will take a while. Today, while it’s on my mind, I want to write about work.

Learning to work is a central part of many fairy tales that share this pattern. Of course we have the “Cinderella”-type tales, in which Cinderella has to cook and clean. She essentially becomes the housekeeper for her stepmother and stepsisters. In the Grimm version “Aschenputtel,” her stepmother specifically asks her to sort bowls of lentils out of the ashes before she can go to the ball. She is helped by the birds that represent her mother’s spirit, so there is an aspect of work that is passed on from mother to daughter: the mother helps the daughter out. The same thing happens in “Vasilisa the Beautiful,” where Vasilisa is helped by the doll her mother gave her. But in that story, too, Vasilisa must do housework for Baba Yaga as well as for her stepmother and stepsisters. Snow White keeps house for the dwarves. Donkeyskin works as the lowest maidservant in a kitchen. Even Beauty, who does not need to work in the Beast’s castle, works as a servant — this time voluntarily — in her own home after her father loses his fortune, rising at four in the morning to do her chores. (Madame de Beaumont had a pretty strict idea of virtue!) In “Six Swans,” the heroine needs to sew the shirts that will save her brothers and return them to their human forms.

There are some important exceptions: in “Sleeping Beauty,” work actually kills the princess, or at least puts her to sleep for a hundred years. As soon as she touches the spindle, she falls asleep. Work happens off-screen in”Rapunzel.” We are told that Rapunzel lives alone for several years with her children, which means she must be supporting them somehow, but we are not told how. Notice, however, that in the Disney version of “Sleeping Beauty,” Princess Aurora must live in a cottage in the forest with the three fairies, where she does housework. The Disney versions tend to standardize fairy tales, using parts of one to fill in narrative gaps in another. Aurora in the fairies’ cottage echoes Snow White with the dwarves. Notice also that in The Wizard of Oz, which incorporates so many of the old fairy tale structures, Dorothy must work for the Wicked Witch of the West.

Often, in these fairy tales, it is exactly the heroine’s work that leads to her final reward. Dorothy kills the witch with the water she was using to wash the floor. Donkeyskin drops her ring into the dish she is preparing for the prince, which allows him to identify her. Vasilisa wins the hand of the Tsar because she makes linen shirts so fine that he must see who wove and sewed them, and then falls in love with her beauty. When she is told that she must sew the shirts, she even says, “I knew all the time . . . that I would have to do this work.” Of course the heroine in “Six Swans” saves her brothers and proves her virtue through her sewing. In “East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon,” the heroine proves her worth by washing the tallow from her husband’s shirt, winning him back from the trolls.

There’s a reason for this emphasis on work, I think. Most of these fairy tales came out of the folk tradition, and peasant women worked. They were proud of their work, and their work was seen as a mark of their worth. It proved that they were good potential wives and mothers. A good woman was also an industrious spinner and weaver, a good needlewoman. So in fairy tales, even princesses need to learn how to work. Sleeping Beauty may be an exception because she comes to us out of the romance tradition: one of the earliest versions of the story appears in the prose romance Perceforest, composed in France around the 1340s. It is the tale of Troilus and Zellandine, and in it Zellandine wakes up not when her beloved kisses her, but when one of the children she has borne while still asleep sucks a piece of flax out of her finger. Whereas folk tales were the literature of the folk, romances were often associated with the aristocracy. Perceforest is written in six books: the tale of Troilus and Zellandine came from and belonged to those who had books and could read them — those, in other words, who did not have to work. Still, there is something thematically important about the fact that Sleeping Beauty falls into her deathly sleep when she takes up what was considered women’s work — in other words, when she reaches maturity. We are still looking, here, at a woman’s journey toward adulthood and marriage.

I think the emphasis on work is an important part of these tales. Which brings us back to ourselves: our own journeys so often involve learning to work. There’s a sense in which work was written out of women’s stories around the time of the Industrial Revolution. If you look at the novels of Jane Austen, they ask the fundamental question: “Whom shall the heroine marry?” There is no interval of work in the journey from the father’s to the husband’s house. By that time, work was a class issue: working meant losing your status as a lady. Only lower-class women worked, and they were largely not the province of the novel. Jane Eyre is so revolutionary in part because it gives us a woman who learns to work before she finds her proper mate, and because she finds sustenance and self-respect in her work. It is only after going through an interval of serious work as a teacher in a poor village that Jane can come back to Rochester. But then, Jane Eyre has a deep fairy tale structure: it starts as “Cinderella,” goes on to become a “Bluebeard” story, and ends as “Beauty and the Beast.” We do, I think, both find and prove ourselves through work. Work is a fundamental part of fairy tales, as it was a fundamental part of the lives of the people who told them. So once again fairy tales can reveal an important truth:

If you want a happy ending, learn to work.

(The image of Sleeping Beauty at the spinning wheel is by Anne Anderson.)

Previous posts in this series:

The Heroine’s Journey

Heroine’s Journey: Snow White

Heroine’s Journey: Sleeping Beauty

Heroine’s Journey: Receiving Gifts

Heroine’s Journey: The Goose-Girl

The Heroine’s Journey II

Heroine’s Journey: The Dark Forest