Theodora Goss's Blog, page 19

December 12, 2014

Making Clafoutis

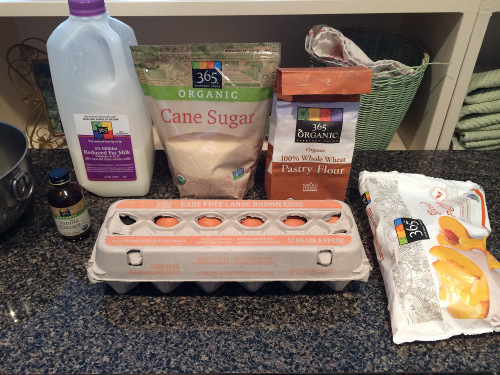

I posted a picture of my Peach Clafoutis on Facebook, and people asked me to share the recipe, so here it is! I’m interrupting my series of blog posts on fairy tale heroines and their journeys to bring you a little snack . . .

First you should know that I don’t use white flour or sugar, because I’m trying to eat more healthily, even when eating desserts! If you want a standard clafoutis recipe, there are many available on the internet. This is a slightly healthier version. I’ve found that you can use whole wheat pastry flour to substitute for white flour, but it is more absorbent, so you typically need less of it. I also use the brownish sugar that is usually labeled “organic sugar” and is a little less processed than the white variety. It can be used just like white sugar, but it has a flavor of its own, a bit more caramely than white sugar. So the flavor of whatever you make will be a bit stronger.

This is a good time to preheat the oven to 350 degrees.

Clafoutis, the way I make it, is basically a thickened custard over fruit. I’ve seen some recipes in which American cooks describe it as a baked pancake, but I think that means they’re using way too much four. It should taste like a custard.

Here are my ingredients for the clafoutis:

1/3 cut flour

3 tbsp. sugar

2 eggs

1 cup milk (I use 2%)

1/2 tsp. vanilla

For the fruit, cherries are traditional. I like peaches. You can also use strawberries, blackberries, and probably raspberries, although I’ve never tried the raspberries myself. In winter especially, when fruit are so expensive, I use frozen fruit, thawed and drained. (The juice will change the consistency of the clafoutis, so drain as much as possible.) When I’m using frozen fruit, I add a tablespoon of sugar to the fruit, because otherwise it tends not to be sweet enough.

Take a baking dish, preferably a pretty one (like the glass pie dish I used here) because you may serve the clafoutis in it. Butter it and then put the fruit on the bottom, arranged however you wish, but in a thin layer.

Assembling the clafoutis is incredibly easy. Just mix all the ingredients except the fruit, starting with the solids and then adding liquids while mixing so it’s not lumpy. I use a hand-held electric mixer.

Then you just pour the clafoutis mixture over the fruit.

Bake in a 350 degree oven until it’s done, which depends on your oven, so I won’t try to give you an exact time. If you’re used to baking, you know there’s a moment when it smells so good, and that’s just before it’s time to take the clafoutis out. Then there’s a moment when you think, I can’t smell it anymore, and that’s it, that’s usually the time. The clafoutis is done when the top is golden brown.

It’s best to let it cool a little bit, but warm clatoutis is a wonderful treat, and it’s just as good cold the next day. Some people sprinkle powdered sugar on top, but I think it’s quite sweet enough as is, so I would only do that if serving it at a party. And here you go, a bowl of Peach Clafoutis!

November 9, 2014

The Heroine’s Journey II

Almost a month ago now, I wrote a blog post called “The Heroine’s Journey,” in which I started mapping the journey I saw heroines going on, in the fairy tales I was teaching. Since then, I’ve gone through three fairy tales, “Snow White,” “Sleeping Beauty,” and “The Goose-Girl,” to see where my theory was right, and where it was wrong — or incomplete. I think that’s important, because I want my theory to use useful, to reflect what is actually there in the tales I’m talking about.

You see, I really care about good scholarship. And so much of what is written about the hero’s or heroine’s journey is not good scholarship.

So what am I actually claiming? That there is a certain set of fairy tales that have heroines, and a subset in which the heroine goes on a journey. And those journeys take a particular shape: they are metaphors for women’s lives. Not necessarily for women’s lives in general, at all times and everywhere. But at least in the societies in which the tales I’m looking at were told, which were generally European, from the 16th through the 19th centuries. So the Fairytale Heroine’s Journey is like a meta-tale type. (If you don’t know, the concept of a tale type was created by the Finnish folklorist Antti Aarne. Folktales are assigned to tale types by their narrative elements: for example, “Snow White” belongs to tale type 709, along with other tales that have similar plots, even if many of their details are different. The tale type is like the trunk of the tale, the details like its branches and leaves. Cinderella can have shoes of gold, or silver, or glass, but the important element will be the shoe that only fits one woman.) There are a number of different tale types that fit into this meta-type, The Fairytale Heroine’s Journey.

I also want to make another claim, one that isn’t meant to be scholarly: that this journey can teach us things about our own journeys, because our society isn’t as different as we sometimes think from the societies in which fairy tales were told or written. And women’s lives aren’t as different, either. The Fairytale Heroine’s Journey is not inherently conservative or liberating. It can be either, depending on how it’s handled: the Grimms give us a more liberating “Cinderella” than does Perrault, I think. And the women writers of the salons, like Madame d’Aulnoy, use this structure over and over again, in part for social critique. The Fairytale Heroine’s Journey is, however, always illuminating: it teaches us things about women’s lives, how they were lived and perceived. And it can teach us something about our own lives . . .

Here’s what I’m not claiming. That this particular Heroine’s Journey is a timeless mythic structure. I don’t think it is — I think it’s very much a product of particular cultures and time periods. (As I think Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey is as well. I adore and respect Campbell, but those sorts of claims ignore the extent to which stories are products of their particular societies. They focus on similarities and ignore differences. And the differences are very, very important.) I also don’t claim that what I’m describing is a psychological structure, embedded deep in the human mind. For one thing, I have no evidence for such a claim, and for another, I’m not particularly interested in it. What I do claim is that the Fairytale Heroine’s Journey is a narrative structure we return to over and over again, that we seem to find particularly useful or satisfying. It would be interesting, actually, to see where else I could find it — is there a way, for example, in which heroines in literary fiction go through a fairytale heroine’s journey? Does Tess of the d’Urbervilles? But that is so far beyond what I’m trying to do right now. Now, I’m just trying to understand it. And this post is about consolidating what I’ve learned from looking at three tales. (I told you, I’m trying to do careful scholarship, and that takes time. My goal is to go through twelve tales — and then, hopefully, I’ll have learned something.)

So, based on the stories I’ve read so far, and my general knowledge of fairy tales, here are the steps in the Fairytale Heroine’s Journey. Notice that I’ve refined this list from the one I started with, in my original post.

1. The heroine receives gifts. Sleeping Beauty receives gifts from the fairies. Donkeyskin receives three dresses from her father and a ring from her mother. Cinderella receives three dresses and magical shoes from the hazel tree.

2. The heroine leaves or loses her home. Donkeyskin leaves home to escape her father. The Goose-girl leaves home to be married. Cinderella loses her home when she is forced to live in the kitchen and sleep on the hearth.

3. The heroine enters the dark forest. Snow White runs away from the huntsman, though the dark forest. The dark forest grows up around Sleeping Beauty.

4. The heroine finds a temporary home. Snow White lives with the dwarves. Donkeyskin lives in the castle kitchen. Vasilisa lives in Baba Yaga’s hut.

5. The heroine finds friends and helpers. Snow White’s dwarves, Cinderella’s doves. The head of a dead horse, three old women by the roadside, the winds themselves — all sorts of people and things can be friends and helpers.

6. The heroine learns to work. Donkeyskin cooks, Snow White and Cinderella keep house. The Goose-girl tends geese. Vasilisa works for Baba Yaga.

7. The heroine endures temptations and trials. Snow White is tempted with lace, a comb, and an apple. Sleeping Beauty is tempted by the spinning wheel. The heroine of “East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon” must travel far to find her husband. In some stories, the trials involve climbing glass mountains or wearing through iron shoes.

8. The heroine dies or loses herself. Snow White dies, Sleeping Beauty falls into a death-like sleep. The Goose-girl is not recognized as a princess. Cinderella is not recognizes as herself (despite having danced with the prince for hours).

9. The heroine finds her true partner. Sometimes this is an entire subplot, in which the heroine must first lose and then find her true partner. I’m still working on this one, but in some stories the finding just happens (“Snow White,” “Sleeping Beauty”), while in others it involves losing and a long search (“East o’ the Sun” being one example).

10. The heroine is revived or recognized. Dead heroines are revived (Snow White, Sleeping Beauty), lost heroines are recognized (Donkeyskin, Cinderella).

11. The heroine enters her true home. Usually, the true home is a castle.

12. The heroine’s tormentor is punished. She is made to dance in red-hot iron shoes, or her eyes are pecked out. Or she is turned into a living statue. Or rolled down the hill in a barrel filled with nails. The punishment is usually, actually or metaphorically, created by the tormentor herself.

That’s what it looks like right now, but I’m going to keep working through stories, trying to figure this out. It’s like a tale type: there are all sorts of variations, and yet you can see — or at least I can see — an underlying pattern in these tales. And that pattern is of a woman’s life.

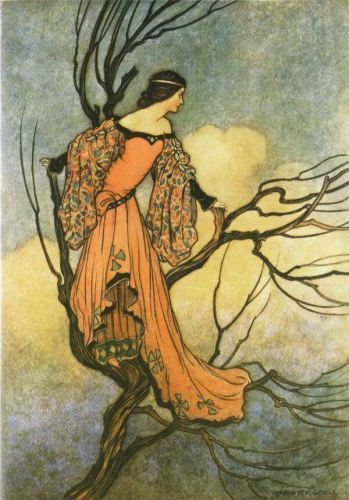

The illustration is by Arthur Rackham.

October 31, 2014

Heroine’s Journey: The Goose-Girl

The next step on our fairytale heroine’s journey is “The Goose-Girl,” from the Brothers Grimm (as translated by Margaret Hunt, 1884). You remember the steps, right?

1. The heroine receives gifts.

2. The heroine leaves or loses her home.

3. The heroine enters the dark forest.

4. The heroine finds a temporary home.

5. The heroine finds friends and helpers.

6. The heroine learns to work.

7. The heroine endures temptations and trials.

8. The heroine dies or visits the dead.

9. The heroine finds her true partner.

10. The heroine is revived or revives another.

11. The heroine enters her true home.

12. The heroine’s tormentor is punished.

Something like that. So what happens to our heroine, the goose-girl?

There was once upon a time an old Queen whose husband had been dead for many years, and she had a beautiful daughter. When the princess grew up she was betrothed to a prince who lived at a great distance. When the time came for her to be married, and she had to journey forth into the distant kingdom, the aged Queen packed up for her many costly vessels of silver and gold, and trinkets also of gold and silver; and cups and jewels, in short, everything which appertained to a royal dowry, for she loved her child with all her heart. She likewise sent her maid in waiting, who was to ride with her, and hand her over to the bridegroom, and each had a horse for the journey, but the horse of the King’s daughter was called Falada, and could speak. So when the hour of parting had come, the aged mother went into her bedroom, took a small knife and cut her finger with it until it bled, then she held a white handkerchief to it into which she let three drops of blood fall, gave it to her daughter and said, “Dear child, preserve this carefully, it will be of service to you on your way.”

And there are Steps 1 and 2: the heroine receives gifts, and she leaves her home. The gifts are the talking horse Falada and the handkerchief with her mother’s blood. If your mother gives you a handkerchief with drops of her blood on it, don’t lose it. Just don’t.

So they took a sorrowful leave of each other; the princess put the piece of cloth in her bosom, mounted her horse, and then went away to her bridegroom. After she had ridden for a while she felt a burning thirst, and said to her waiting-maid, “Dismount, and take my cup which thou hast brought with thee for me, and get me some water from the stream, for I should like to drink.” “If you are thirsty,” said the waiting-maid, “get off your horse yourself, and lie down and drink out of the water, I don’t choose to be your servant.” So in her great thirst the princess alighted, bent down over the water in the stream and drank, and was not allowed to drink out of the golden cup. Then she said, “Ah, Heaven!” and the three drops of blood answered, “If thy mother knew, her heart would break.” But the King’s daughter was humble, said nothing, and mounted her horse again.

This happens a second time, with the maid refusing to serve the princess and the drops of blood opining that her mother’s heart would break.

And as she was thus drinking and leaning right over the stream, the handkerchief with the three drops of blood fell out of her bosom, and floated away with the water without her observing it, so great was her trouble. The waiting-maid, however, had seen it, and she rejoiced to think that she had now power over the bride, for since the princess had lost the drops of blood, she had become weak and powerless.

And there you go: I told you not to lose the handkerchief with the drops of blood, didn’t I? Without the drops of blood, the princess has lost a source of possible help, and is now in the maid’s power. Notice that we are in the middle of Step 3: we have been riding through the dark forest. The dark forest is where the princess loses her power, and more than that.

So now when she wanted to mount her horse again, the one that was called Falada, the waiting-maid said, “Falada is more suitable for me, and my nag will do for thee” and the princess had to be content with that. Then the waiting-maid, with many hard words, bade the princess exchange her royal apparel for her own shabby clothes; and at length she was compelled to swear by the clear sky above her, that she would not say one word of this to any one at the royal court, and if she had not taken this oath she would have been killed on the spot. But Falada saw all this, and observed it well.

She also loses her identity. The dark forest is where you lose who you are: Snow White loses her identity as princess when she runs away into the forest. Instead, she becomes the dwarves’ housekeeper. The other day, I had a revelation which I’ll write about more later. I thought about friends of mine who were going through metaphorical dark forests of their own, and suddenly it came to me: the heroine never dies in the dark forest. Seriously, never. The dark forest may be where she feels most alone and afraid. But she doesn’t die until later in the story. The dark forest is where she loses herself in a process of transformation. The princess is no longer herself, which is confusing and scary.

Here, the maid pretends to be the princess, and the princess has to act as maid. They come to the royal palace, and the maid is greeted as the prince’s bride.

Then the old King looked out of the window and saw her standing in the courtyard, and how dainty and delicate and beautiful she was, and instantly went to the royal apartment, and asked the bride about the girl she had with her who was standing down below in the courtyard, and who she was? “I picked her up on my way for a companion; give the girl something to work at, that she may not stand idle.” But the old King had no work for her, and knew of none, so he said, “I have a little boy who tends the geese, she may help him.”

So the princess becomes the goose-girl. And here we are at Steps 4 and 6: the heroine finds a temporary home, and she learns to work. The princess lives in the castle, but not in the right way, not in the way she should. The temporary home sometimes takes that form: it’s the true home, but not inhabited in the right way. And the princess learns to tend geese. Learning to work often involves menial work. I think this is an important step in the heroin’s journey, but one I could not see until I started this project. I did not realize how important it was, how many heroines have to clean (Cinderella), cook (Donkeyskin), tend geese. I think there’s something quite positive about it. We have a sense that princesses sit around waiting for princes to rescue them, but that’s not what happens in fairytales. No, princesses sit around tending geese. In other words, they get jobs.

The maid realizes that Falada poses a danger to her, so she orders the horse killed. Perhaps I should have called Falada a friend and helper? Yes, I think that’s what we see here: Step 5, the heroine finds friends and helpers. That’s where Falada fits. And she has to work for him, too: the princess promises the knacker a piece of gold if he will do her a favor.

There was a great dark-looking gateway in the town, through which morning and evening she had to pass with the geese: would he be so good as to nail up Falada’s head on it, so that she might see him again, more than once. The knacker’s man promised to do that, and cut off the head, and nailed it fast beneath the dark gateway.

Notice that she has her own money: did she earn it herself? The maid took everything she had, so there’s a chance that it’s her own money, earned by her own work. Which is also important, the possibility that she is saving herself through her own labor.

Early in the morning, when she and Conrad drove out their flock beneath this gateway, she said in passing,

“Alas, Falada, hanging there!”

Then the head answered,

“Alas, young Queen, how ill you fare!

If this your tender mother knew,

Her heart would surely break in two.”

So you see, Falada sounds a lot like the drops of blood. The princess made a mistake: she lost the handkerchief, which was a gift. But she can rectify that loss: she gave the gold coin for Falada’s head, and it will help her, speaking with the voice of the gift, speaking for her mother. Now the princess is about to endure Step 7, the temptations and trials. The greatest trial is having to be goose-girl. The lesser trial is having to deal with Conrad.

Then they went still further out of the town, and drove their geese into the country. And when they had come to the meadow, she sat down and unbound her hair which was like pure gold, and Conrad saw it and delighted in its brightness, and wanted to pluck out a few hairs. Then she said,

“Blow, blow, thou gentle wind, I say,

Blow Conrad’s little hat away,

And make him chase it here and there,

Until I have braided all my hair,

And bound it up again.”

The wind blows Conrad’s hat away, so that he has to run after it. I’m not sure why this is such an important part of the narrative? I think it reveals a sort of danger to the princess: the danger that a rough servant boy, like Conrad, could become enamored of her. Could perhaps insult or assault her? The golden hair is also important: it signifies her value, her purity. Conrad is attracted to it, but it has to be preserved for someone else, for the true partner, which Conrad most definitely is not. This scene happens again the next day, and Conrad starts to complain.

But in the evening after they had got home, Conrad went to the old King, and said, “I won’t tend the geese with that girl any longer!” “Why not?” inquired the aged King. “Oh, because she vexes me the whole day long.” Then the aged King commanded him to relate what it was that she did to him. And Conrad said, “In the morning when we pass beneath the dark gateway with the flock, there is a sorry horse’s head on the wall, and she says to it,

“Alas, Falada, hanging there!”

And the head replies,

“Alas, young Queen how ill you fare!

If this your tender mother knew,

Her heart would surely break in two.”

And Conrad went on to relate what happened on the goose pasture, and how when there he had to chase his hat.

Hearing this, the king decides to spy on the goose-girl. He sees everything that happens, and in the evening, he calls the goose-girl to him, asking her why she speaks to Falada in that way.

“I may not tell you that, and I dare not lament my sorrows to any human being, for I have sworn not to do so by the heaven which is above me; if I had not done that, I should have lost my life.” He urged her and left her no peace, but he could draw nothing from her. Then said he, “If thou wilt not tell me anything, tell thy sorrows to the iron-stove there,” and he went away. Then she crept into the iron-stove, and began to weep and lament, and emptied her whole heart, and said, “Here am I deserted by the whole world, and yet I am a King’s daughter, and a false waiting-maid has by force brought me to such a pass that I have been compelled to put off my royal apparel, and she has taken my place with my bridegroom, and I have to perform menial service as a goose-girl. If my mother did but know that, her heart would break.”

This is a step I’m not quite sure about: Step 8, in which the heroine dies. You see, the goose-girl does not die, in any ordinary sense. Snow White dies, and Sleeping Beauty sleeps for a hundred years, which is the next best (or worst) thing to death. But the goose-girl just crawls into the iron-stove. Isn’t that strange? It reminds me of Cinderella sleeping on the hearth, among the ashes. And that, for me, is an image of death, because we associate ashes with the dead. So perhaps there is a whisper of death here: a whisper of crawling into a small space, a space like a tomb or womb, like the belly of the wolf in “Little Red Riding Hood.” This is the only space in which the princess can whisper her secret, reveal her true identity. Over and over again, in fairy tale journeys, we see this crawling into or lying in a small space: a coffin, a tower room. The heroine has to go in, and when she comes out, it’s to transform into her true self. Like a caterpillar becoming a chrysalis becoming a butterfly.

The aged King, however, was standing outside by the pipe of the stove, and was listening to what she said, and heard it. Then he came back again, and bade her come out of the stove. And royal garments were placed on her, and it was marvellous how beautiful she was!

So there she is: her true identity is revealed. Again we have two steps: Step 10, the heroine is revived, and Step 9, she finds her true partner.

The aged King summoned his son, and revealed to him that he had got the false bride who was only a waiting-maid, but that the true one was standing there, as the sometime goose-girl. The young King rejoiced with all his heart when he saw her beauty and youth, and a great feast was made ready to which all the people and all good friends were invited. At the head of the table sat the bridegroom with the King’s daughter at one side of him, and the waiting-maid on the other, but the waiting-maid was blinded, and did not recognize the princess in her dazzling array.

Step 11 is the heroine enters her true home, and here the princess has entered her true home, which is the same home, but she now enters it through a different door and as a different person. She is no longer in the kitchen but in the banquet-hall. And finally we see Step 12: the heroine’s tormentor is punished.

When they had eaten and drunk, and were merry, the aged King asked the waiting-maid as a riddle, what a person deserved who had behaved in such and such a way to her master, and at the same time related the whole story, and asked what sentence such an one merited? Then the false bride said, “She deserves no better fate than to be stripped entirely naked, and put in a barrel which is studded inside with pointed nails, and two white horses should be harnessed to it, which will drag her along through one street after another, till she is dead.” “It is thou,” said the aged King, “and thou hast pronounced thine own sentence, and thus shall it be done unto thee.” And when the sentence had been carried out, the young King married his true bride, and both of them reigned over their kingdom in peace and happiness.

We even have the words “true bride” here: the princess is the true bride, as the prince is her true partner.

What can we learn from “The Goose-Girl”? First, that you should not lose your gifts, but if you do, all is not lost. You may still have friends and helpers, and they will save you when your gifts cannot. Second, that even if you have to work as a goose-girl for a while, you are still a princess. You still retain your value, even if you have to hide it away from the Conrads of the world. Third, that you must reveal your secret self in order to become it, even if it’s only to an iron-stove pipe. And then somehow, the secret will out. Your true self will be revealed. You can’t find your true home, your true partner, without revealing it.

I think there’s a final lesson here, which has to do with the violent ending of some of these tales. The maid dies a horrible death, and yet she created it herself. It reminds me of Madame de Beaumont’s “Beauty and the Beast,” in which the selfish sisters are turned to stone statues. They have the power to save themselves: all they have to do is become unselfish. Their final state is a literalization of what they were all along: statutes, cold and lifeless. In “Snow White,” the wicked queen dances to death in red-hot iron shoes, but she has been burning up all along. Her jealously is what ultimately kills her. So perhaps there’s a reason that the violent ends of the antagonists are often determined by their own words, or described as though they were acts of Fate even though someone had to heat up the iron shoes. There’s a sense in which the ends are always created by the antagonists themselves.

What shall I talk about next? Probably the need to leave home and venture into the dark forest . . .

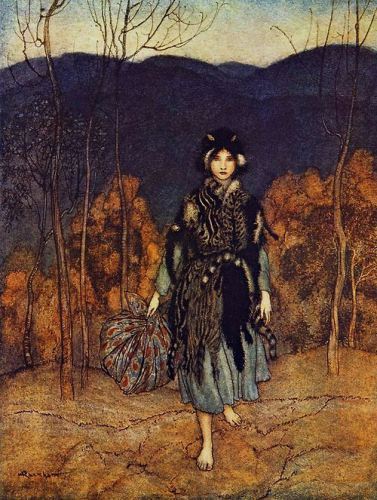

This image is “The Goose-Girl” by Jessie Wilcox Smith.

October 25, 2014

Heroine’s Journey: Receiving Gifts

As you know, I’m taking a sort of journey: that is, I’m following along the heroine’s journey in fairy tales and trying to map its steps or stages. I call this project Mapping the Fairytale Heroine’s Journey. I started by trying to define the journey I saw in many popular fairy tales focused on heroines, and then I tested my theory by looking at two fairy tales specifically: “Snow White” and “Sleeping Beauty.” I want to keep going through fairy tales, until I’ve done twelve (which is a magical number), to document the steps. But in the meantime, I also want to look at the steps individually. So today, I’m going to write about “The heroine receives gifts.”

This seems to happen in almost all the tales I’m looking at, and the gifts seem to take two forms: attributes or physical objects. The attributes determine how the heroine lives her life and how people respond to her. The physical gifts help on her journey — as long as she keeps hold of them and uses them correctly.

Fairy tales in which the heroines are given gifts that are also attributes include “Snow White” and “Sleeping Beauty.” “Sleeping Beauty” is the best example of this sort of gift: in the Perrault version, the fairies literally come to her christening and give her beauty, wit, grace, the ability to dance and sing, even the ability to play musical instruments. Basically, everything that the perfect aristocratic girl would need at the court of Louis XIV. (Remember that literary fairy tales always reflect the time in which they were written. They may retain the common elements that make a “tale type,” but the details will differ. And details are important.) We see these sorts of gifts in a simpler form in “Snow White” as well: before she is born, her mother wishes to have a child with skin as white as snow, lips as red as blood, hair as black as ebony wood. Snow’s beauty is created by magic, by wishing: it is her mother’s gift. (How ironic, then, that her mother later wishes to kill her for that beauty — the Grimms substituted a stepmother, but in their first edition, it was Snow’s own mother who wanted her dead.)

Fairy tales in which the heroines are given physical gifts are perhaps more common. In “The Goose Girl,” the princess is given two gifts: the handkerchief with her mother’s blood on it, and the talking horse Falada. She loses the first gift, and so can’t rely on her mother’s help or protection — which is often deadly in fairy tales. If you go on a journey without your mother’s blessing, watch out! But in the end, Falada saves her. In “East o’the Sun and West o’the Moon,” the heroine is given a golden apple, a golden carding comb, and a golden spindle. She later gives these items to the troll princess in exchange for spending three nights with her lover. On the third night, he hears the story she is trying to tell him, and they can act together to save themselves as well as the other prisoners in the trolls’ castle. In “Cinderella,” the heroine receives dresses to go to the ball from, depending on the version, either her fairy godmother (Perrault) or the spirit of her dead mother in a hazel tree (Grimm). In an ancient Chinese Cinderella story, the dress and shoes come from a magical fish. “Donkeyskin” has an interesting and important variation on the gifts: in that story, the queen dies and the king decides to marry his daughter, since she’s the only one as beautiful as his dead wife. In order to put him off, she asks for three dresses: the colors of the sun, moon, and stars (although again the details — sometimes one of the dresses is the color of the sky). When he manages to provide those dresses, she asks for the skin of a magical donkey, or the fur of a hundred cats, or the skin of a hundred different animals. He provides that as well. Since he can’t be put off any longer, she disguises herself in the ugly skins and runs away, with the dresses. She later wears those dresses, in some versions to a ball like Cinderella. The prince sees her and falls in love with her. So she uses gifts gotten under terrible circumstances to save herself. Even terrible gifts can save you, if you use them correctly, the fairy tale tells us. The fairy tale heroine can use trauma in a positive way.

At the center of my theory is the idea that this structure, the fairytale heroine’s journey, is a deep narrative structure — and that it comes in part from women’s actual lives. So, let’s think about this: how does the idea of receiving gifts apply to a woman’s life? I don’t know about you, but I feel as though I’ve received a lot of gifts. Some of them are attributes: intelligence, talent, grace (although dance classes helped). Even beauty, although it took about forty years for me to feel that! Health, certainly. I have to cultivate and work on those gifts: my writing talent doesn’t do me any good unless I actually sit down and write. And don’t we also receive gifts that are objects? Maybe not golden apples, but for me, the gift of a college education. From friends, the gift of books. From my family, the gift of my grandmother’s jewelry, which came to me and connects me to the past.

What do fairy tales tell us about these kinds of gifts? First, do not lose them. Fairy tales tell us that all gifts, including attributes like beauty, can be lost. Second, use them wisely, and that means use them on your journey. Sometimes you have to give them away, to get something more valuable. Your gifts can help you. Often they are given to you by the friends and helpers that constitute another step of the journey (The heroine finds friends and helpers). You never know who these friends and helpers may be, so be kind to animals and old women who just happen to be spinning by the roadside. Third, even when you are in serious trouble, you may receive gifts that will eventually help you, as Donkeyskin does. Sometimes, they may not look like gifts–who wants a bunch of catskins? And yet the heroine uses them to save herself. Fourth and finally, even a curse may turn out to be a gift. I don’t think it’s coincidental that Sleeping Beauty is cursed at the same christening where she receives her gifts: it makes deep narrative sense that the curse would turn out to be what sets the princess on her journey, and what eventually gets her to the right place. The curse turns out to be what gives her the happy ending. So curses may be gifts in disguise . . .

(The illustration, by Arthur Rackham, is from a version of “Catskin.”)

Here are the previous blog posts I’ve written on the Fairytale Heroine’s Journey. If you want to follow along, go take a look!

The Heroine’s Journey

Heroine’s Journey: Snow White

Heroine’s Journey: Sleeping Beauty

October 22, 2014

Heroine’s Journey: Sleeping Beauty

This is my second attempt to map the fairytale heroine’s journey in a specific tale. I’m calling this project Mapping the Fairytale Heroine’s Journey. As you may know if you’re following along, I started with a blog post called “The Heroine’s Journey,” in which I listed ten steps or stages the fairytale heroine goes through. Then, I took a look at “Snow White” to see if I could find those steps. In that blog post, “Heroine’s Journey: Snow White,” I refined the list of steps. So right now it looks like this:

1. The heroine receives gifts.

2. The heroine leaves or loses her home.

3. The heroine goes into the dark forest.

4. The heroine finds a temporary home.

5. The heroine finds friends and helpers.

6. The heroine learns to work.

7. The heroine endures temptations and trials.

8. The heroine dies or visits the dead.

9. The heroine finds her true partner.

10. The heroine is revived or revives another.

11. The heroine enters her true home.

12. The heroine’s tormentor is punished.

My hypothesis is that certain fairy tales, specifically tales about a heroine’s maturation process, follow a series of steps that can occur in different order but have an overall trajectory. Where does this journey come from? Parts of it remind me of myth, parts remind me of ritual (such as rites of passage), but what it reminds me of most is women’s lives: the lives of friends of mine, who go through dark forests and find friends and helpers, who endure temptations and trials. What interests me is narrative structure: the way we tell stories about women’s lives.

So, on to my second fairy tale: “Sleeping Beauty.” Let’s see if the structure works . . . This is the version by Charles Perrault, translated by Andrew Lang (or his wife, who did a lot of the translating, uncredited). It was published in The Blue Fairy Book (1889).

1. The heroine receives gifts.

We know this one, right? This is the gift-giving scene par excellence. If any fairy tale emphasizes the gifts, it is “Sleeping Beauty.”

There were formerly a king and a queen, who were so sorry that they had no children; so sorry that it cannot be expressed. They went to all the waters in the world; vows, pilgrimages, all ways were tried, and all to no purpose.

At last, however, the Queen had a daughter. There was a very fine christening; and the Princess had for her godmothers all the fairies they could find in the whole kingdom (they found seven), that every one of them might give her a gift, as was the custom of fairies in those days. By this means the Princess had all the perfections imaginable.

After the ceremonies of the christening were over, all the company returned to the King’s palace, where was prepared a great feast for the fairies. There was placed before every one of them a magnificent cover with a case of massive gold, wherein were a spoon, knife, and fork, all of pure gold set with diamonds and rubies. But as they were all sitting down at table they saw come into the hall a very old fairy, whom they had not invited, because it was above fifty years since she had been out of a certain tower, and she was believed to be either dead or enchanted.

The King ordered her a cover, but could not furnish her with a case of gold as the others, because they had only seven made for the seven fairies. The old Fairy fancied she was slighted, and muttered some threats between her teeth. One of the young fairies who sat by her overheard how she grumbled; and, judging that she might give the little Princess some unlucky gift, went, as soon as they rose from table, and hid herself behind the hangings, that she might speak last, and repair, as much as she could, the evil which the old Fairy might intend.

In the meanwhile all the fairies began to give their gifts to the Princess. The youngest gave her for gift that she should be the most beautiful person in the world; the next, that she should have the wit of an angel; the third, that she should have a wonderful grace in everything she did; the fourth, that she should dance perfectly well; the fifth, that she should sing like a nightingale; and the sixth, that she should play all kinds of music to the utmost perfection.

Of course, the princess is then cursed, and that curse is mitigated by the seventh fairy.

The old Fairy’s turn coming next, with a head shaking more with spite than age, she said that the Princess should have her hand pierced with a spindle and die of the wound. This terrible gift made the whole company tremble, and everybody fell a-crying.

At this very instant the young Fairy came out from behind the hangings, and spake these words aloud:

“Assure yourselves, O King and Queen, that your daughter shall not die of this disaster. It is true, I have no power to undo entirely what my elder has done. The Princess shall indeed pierce her hand with a spindle; but, instead of dying, she shall only fall into a profound sleep, which shall last a hundred years, at the expiration of which a king’s son shall come and awake her.”

You can already see two later steps implied by this scene: the heroine will metaphorically die (by falling into a death-like sleep) and will find her true partner, identified as the one who can wake her.

2. The heroine dies or visits the dead.

Wait, that’s supposed to come later, right? But I mentioned that the steps don’t always happen in the same order. Here the heroine dies first, and then all sorts of other things happen.

About fifteen or sixteen years after, the King and Queen being gone to one of their houses of pleasure, the young Princess happened one day to divert herself in running up and down the palace; when going up from one apartment to another, she came into a little room on the top of the tower, where a good old woman, alone, was spinning with her spindle. This good woman had never heard of the King’s proclamation against spindles.

“What are you doing there, goody?” said the Princess.

“I am spinning, my pretty child,” said the old woman, who did not know who she was.

“Ha!” said the Princess, “this is very pretty; how do you do it? Give it to me, that I may see if I can do so.”

3. The heroine endures temptations and trials.

I think of this as the princess’s first temptation: she is drawn to the spindle and touches it, even though it is not hers, she has no permission to do so. And, of course, she has no idea what it is.

She had no sooner taken it into her hand than, whether being very hasty at it, somewhat unhandy, or that the decree of the Fairy had so ordained it, it ran into her hand, and she fell down in a swoon.

They try to revive the princess, but nothing works: she is fast asleep. As though she were dead.

4. The heroine finds friends and helpers.

This actually happens twice. The first helper is the seventh fairy, who has already mitigated the curse. Now she causes everyone else in the palace to fall asleep.

The good Fairy who had saved her life by condemning her to sleep a hundred years was in the kingdom of Matakin, twelve thousand leagues off, when this accident befell the Princess; but she was instantly informed of it by a little dwarf, who had boots of seven leagues, that is, boots with which he could tread over seven leagues of ground in one stride. The Fairy came away immediately, and she arrived, about an hour after, in a fiery chariot drawn by dragons.

The King handed her out of the chariot, and she approved everything he had done, but as she had very great foresight, she thought when the Princess should awake she might not know what to do with herself, being all alone in this old palace; and this was what she did: she touched with her wand everything in the palace (except the King and Queen) — governesses, maids of honor, ladies of the bedchamber, gentlemen, officers, stewards, cooks, undercooks, scullions, guards, with their beefeaters, pages, footmen; she likewise touched all the horses which were in the stables, pads as well as others, the great dogs in the outward court and pretty little Mopsey too, the Princess’s little spaniel, which lay by her on the bed.

Notice that she turns the princess’s castle into a land of the dead. If sleep is a metaphorical death, then all in the castle are also dead: the princess is surrounded by them. This is the land that the prince will eventually enter.

5. The heroine leaves or loses her home.

And now the King and the Queen, having kissed their dear child without waking her, went out of the palace and put forth a proclamation that nobody should dare to come near it.

The princess does not lose her physical home, but she loses her parents. Without leaving the castle, she ventures into the dark forest, alone — except for sleeping servants who cannot help her.

6. The heroine goes into the dark forest.

And that’s the next step, except that in this case, the dark forest grows up around her.

This, however, was not necessary, for in a quarter of an hour’s time there grew up all round about the park such a vast number of trees, great and small, bushes and brambles, twining one within another, that neither man nor beast could pass through; so that nothing could be seen but the very top of the towers of the palace; and that, too, not unless it was a good way off.

The prince, intrigued by what he has heard about the beautiful princess sleeping in the dark forest, goes in quest of her. We know he is her true partner because the forest gives way in from of him. Then he comes to the castle itself. Notice the language:

He came into a spacious outward court, where everything he saw might have frozen the most fearless person with horror. There reigned all over a most frightful silence; the image of death everywhere showed itself, and there was nothing to be seen but stretched-out bodies of men and animals, all seeming to be dead.

You see, it’s a metaphorical land of the dead.

7. The heroine is revived or revives another.

8. The heroine finds her true partner.

These two steps happen at the same time.

And now, as the enchantment was at an end, the Princess awaked, and looking on him with eyes more tender than the first view might seem to admit of:

“Is it you, my Prince?” said she to him. “You have waited a long while.”

The Prince, charmed with these words, and much more with the manner in which they were spoken, knew not how to show his joy and gratitude; he assured her that he loved her better than he did himself; their discourse was not well connected, they did weep more than talk — little eloquence, a great deal of love.

This is where modern versions of the story end, with the prince carrying the princess back to his castle, where they live happily ever after. But it’s not where the Perrault version ends: it’s not where older versions ended either. Notice that some steps of the journey have been left out, so it’s not over yet.

(I should add here that Perrault’s is already a cleaned-up version. In at least one earlier version, the prince has two children with the princess while she is still asleep, and it’s only when one of those children sucks a splinter out of her finger that she wakes up.)

So what happens in the Perrault version? Well, the prince doesn’t want to tell his father that he is married. I’m not sure why? Probably because children of kings were political chess-pieces, and he thinks his father would not approve. So he leaves the princess in her castle for two years, while she bears him two children, Morning and Day. His father believes him when he claims that he’s just out hunting — for days at a time. But his mother becomes increasingly suspicious. The prince is also worried about her, because she’s an Ogress and has a taste for little children. Then, the king dies.

9. The heroine enters her true home.

But when the King was dead, which happened about two years afterward, and he saw himself lord and master, he openly declared his marriage; and he went in great ceremony to conduct his Queen to the palace. They made a magnificent entry into the capital city, she riding between her two children.

The princess’s true home is the prince’s castle, where she will take her rightful place as queen. But there are complications still to come. Remember: Ogress. (In the older versions, the prince has not yet married the princess, because he is already married, and it is his wife, rather than an Ogress mother, who causes trouble for her.)

10. The heroine finds a temporary home.

Here, she is sent to her temporary home, and it is not a refuge for her . . . (So the temporary home functions very differently than in “Snow White”). The prince departs to fight a war in a neighboring kingdom and leaves his mother in power. You know, the Ogress.

He left the government of the kingdom to the Queen his mother, and earnestly recommended to her care his wife and children. He was obliged to continue his expedition all the summer, and as soon as he departed the Queen-mother sent her daughter-in-law to a country house among the woods, that she might with the more ease gratify her horrible longing.

Although the princess has entered her true home, she almost immediately has to leave it again: she enters a temporary home in the dark forest. Notice that she is repeating an earlier step. First the dark forest grew around her initial home, and how she must ride into it to her temporary home. She’s back in the dark forest. What the Ogress wants is, of course, the children.

Some few days afterward she went thither herself, and said to her clerk of the kitchen:

“I have a mind to eat little Morning for my dinner to- morrow.”

“Ah! madam,” cried the clerk of the kitchen.

“I will have it so,” replied the Queen (and this she spoke in the tone of an Ogress who had a strong desire to eat fresh meat), “and will eat her with a sauce Robert.”

I think the sauce Robert is important.

This is when the princess finds another set of friends and helpers: human, this time, rather than fairy.

The poor man, knowing very well that he must not play tricks with Ogresses, took his great knife and went up into little Morning’s chamber. She was then four years old, and came up to him jumping and laughing, to take him about the neck, and ask him for some sugar-candy. Upon which he began to weep, the great knife fell out of his hand, and he went into the back yard, and killed a little lamb, and dressed it with such good sauce that his mistress assured him that she had never eaten anything so good in her life. He had at the same time taken up little Morning, and carried her to his wife, to conceal her in the lodging he had at the bottom of the courtyard.

The clerk of the kitchen saves Morning, and then, and then the princess herself (now queen) through a series of similar subterfuges.

I said that the spindle was her temptation: this is her trial. She must endure the fear and sorrow of losing her children, and then fear of the Ogress queen. The queen, of course, finds out.

One evening, as she was, according to her custom, rambling round about the courts and yards of the palace to see if she could smell any fresh meat, she heard, in a ground room, little Day crying, for his mamma was going to whip him, because he had been naughty; and she heard, at the same time, little Morning begging pardon for her brother.

The Ogress presently knew the voice of the Queen and her children, and being quite mad that she had been thus deceived, she commanded next morning, by break of day (with a most horrible voice, which made everybody tremble), that they should bring into the middle of the great court a large tub, which she caused to be filled with toads, vipers, snakes, and all sorts of serpents, in order to have thrown into it the Queen and her children, the clerk of the kitchen, his wife and maid; all whom she had given orders should be brought thither with their hands tied behind them.

This is the worst that the princess has endured: the hundred year’s sleep was much easier, wasn’t it? I think that’s partly why this section of the story is left out, nowadays. But the prince comes home just in time and asks, as well he might, what in the world is going on.

11. The heroine’s tormentor is punished.

No one dared to tell him, when the Ogress, all enraged to see what had happened, threw herself head foremost into the tub, and was instantly devoured by the ugly creatures she had ordered to be thrown into it for others. The King could not but be very sorry, for she was his mother; but he soon comforted himself with his beautiful wife and his pretty children.

And they lived happily ever after. With no Ogresses.

Notice that there’s something missing, a step I added last time and that I thought was important. And yet it’s not here!

12. The heroine learns to work.

No, she doesn’t. In fact, something quite different happens: the princess is menaced by the very things she might have learned to do in another fairy tale, the things that fairy tale heroines do. Spinning and cooking. The spindle puts her to sleep, and then the Ogress threatens to cook her. In a sauce Robert! I’m not sure what’s going on here yet, but I suspect it’s a reference to, and commentary on, typical seventeenth- and eighteenth-century women’s work. Somehow, in this context, it’s deadly. Or perhaps not having mastered them is deadly? Perhaps if the princess had known how to spin and cook, she would not have been menaced in the same way. After all, it was her father who forbade any spinning in the kingdom . . . Perhaps in trying to protect her, he doomed her?

The step is missing, and yet it’s still there by reference and implication.

So that’s “Sleeping Beauty.” Which fairy tale shall I do next? I’m not sure . . .

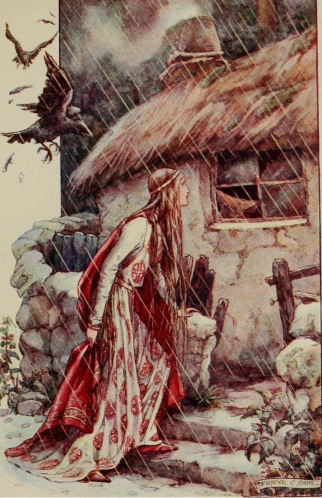

This is the Sleeping Beauty with her son, little Day, by Karl Larson.

October 20, 2014

Heroine’s Journey: Snow White

Earlier this week, I posted a blog post called The Heroine’s Journey. In it, I talked about the journey I had seen fairy tale heroines take in the stories I was teaching, and listed the steps of that journey. I think the journey is real: I think it’s an underlying structure of many fairy tale journeys taken by female characters. But the only way to test that intuition is against the stories themselves. So over the next few weeks, as I have time, I’ll be talking about how that journey looks in various fairy tales. Today’s tale is “Snow White.” As I do this, I’ll be refining the original steps; I already think there are a few more than I originally noticed.

Once again, the steps can happen out of order, although they have a general trajectory. “Snow White” has them in a slightly different order than I first described. What I’ll do is list the steps and then show how they appear in the story. When studying fairy tales, it’s always important to specify which version you’re quoting from. The quotations below come from Grimm’s Household Tales, a translation of the Grimms’ collection by Margaret Hunt (London: George Bell, 1884).

1. The heroine receives gifts and attributes.

This is one of the first things that happens in “Snow White”:

Once upon a time in the middle of winter, when the flakes of snow were falling like feathers from the sky, a queen sat at a window sewing, and the frame of the window was made of black ebony. And whilst she was sewing and looking out of the window at the snow, she pricked her finger with the needle, and three drops of blood fell upon the snow. And the red looked pretty upon the white snow, and she thought to herself, “Would that I had a child as white as snow, as red as blood, and as black as the wood of the window-frame.”

Snow White’s beauty comes from her mother’s wishes; like Sleeping Beauty receiving the gifts of the fairies, she is formed by magic. Her beauty is one of her most important attributes, and will drive the plot of the tale.

2. The heroine leaves or loses her home.

After a year had passed the King took to himself another wife. She was a beautiful woman, but proud and haughty, and she could not bear that any one else should surpass her in beauty.

Either the heroine has to leave home, or her safe and comfortable home is destabilized, often by a parent’s remarriage. Both happen to Snow White: first she loses her family structure, and then she is actually sent away from her home. It’s important to note that in the first edition of 1812, Snow White’s mother does not die: instead, she herself turns against Snow White. But in either case we have a destabilization of the home.

She called a huntsman, and said, “Take the child away into the forest; I will no longer have her in my sight. Kill her, and bring me back her heart as a token.” The huntsman obeyed, and took her away; but when he had drawn his knife, and was about to pierce Snow-white’s innocent heart, she began to weep, and said, “Ah, dear huntsman, leave me my life! I will run away into the wild forest, and never come home again.”

And so, like many other fairy tale heroines, Snow White is thrust out into the world.

3. The heroine goes into the dark forest.

But now the poor child was all alone in the great forest, and so terrified that she looked at every leaf of every tree, and did not know what to do. Then she began to run, and ran over sharp stones and through thorns, and the wild beasts ran past her, but did her no harm.

This happens exactly the way I described, and in the same order: there goes Snow White, running through the trees . . .

4. The heroine finds a temporary home.

She ran as long as her feet would go until it was almost evening; then she saw a little cottage and went into it to rest herself. Everything in the cottage was small, but neater and cleaner than can be told. There was a table on which was a white cover, and seven little plates, and on each plate a little spoon; moreover, there were seven little knives and forks, and seven little mugs. Against the wall stood seven little beds side by side, and covered with snow-white counterpanes.

The dwarves’ cottage is Snow White’s temporary home, where she can rest for a while. She will eventually have to leave, of course. The temporary home is always a place that the heroine has to eventually leave.

5. The heroine finds friends and helpers.

These are of course the seven dwarves.

When it was quite dark the owners of the cottage came back; they were seven dwarfs who dug and delved in the mountains for ore. They lit their seven candles, and as it was now light within the cottage they saw that some one had been there, for everything was not in the same order in which they had left it.

They will help and protect her while she goes through the most difficult part of her journey.

6. The heroine learns to work.

I added this step to the list when I realized that often, the fairy tale heroine has to learn to work. That work is usually housework or servants’ work: she learns to clean or cook. I’m not sure why this step is important? Perhaps it has to do with a heroine needing to learn women’s work, because after all these tales come out of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. But I think there’s more to it than that. Even helpless princesses have to learn how to take care of themselves and others — how to make a living and a life.

The dwarfs said, “If you will take care of our house, cook, make the beds, wash, sew, and knit, and if you will keep everything neat and clean, you can stay with us and you shall want for nothing.” “Yes,” said Snow-white, “with all my heart,” and she stayed with them. She kept the house in order for them; in the mornings they went to the mountains and looked for copper and gold, in the evenings they came back, and then their supper had to be ready.

7. The heroine endures temptations and trials.

Snow White’s temptations and trials are the three visits from her stepmother, during which her stepmother sells her corset laces, a comb, and the apple. She fails the tests, and each time she dies. But each time her friends and helpers rescue her. Granted, this makes Snow White seem a little weak, even a little stupid. But she’s a human heroine: she gives in to her vanity. The story reinforces that she’s not perfect, that she is subject to temptation. Sleeping Beauty gives in to temptation as well, when she touches the spindle. And the help Snow White gets is earned — she’s earned it by her work.

8. The heroine dies or visits the dead.

The last temptation proves so deadly that Snow White can’t be revived.

“Are you afraid of poison?” said the old woman; “look, I will cut the apple in two pieces; you eat the red cheek, and I will eat the white.” The apple was so cunningly made that only the red cheek was poisoned. Snow-white longed for the fine apple, and when she saw that the woman ate part of it she could resist no longer, and stretched out her hand and took the poisonous half. But hardly had she a bit of it in her mouth than she fell down dead. Then the Queen looked at her with a dreadful look, and laughed aloud and said, “White as snow, red as blood, black as ebony-wood! this time the dwarfs cannot wake you up again.”

And sure enough, they can’t. She’s not completely dead, of course. She still looks as though she were alive, so they put her in the glass coffin.

Then they were going to bury her, but she still looked as if she were living, and still had her pretty red cheeks. They said, “We could not bury her in the dark ground,” and they had a transparent coffin of glass made, so that she could be seen from all sides, and they laid her in it, and wrote her name upon it in golden letters, and that she was a king’s daughter.

Deep sleep counts as a metaphorical death, in fairy tales. Sleeping Beauty’s sleep also counts as being dead.

9. The heroine finds her true partner.

This is the prince.

It happened, however, that a king’s son came into the forest, and went to the dwarfs’ house to spend the night. He saw the coffin on the mountain, and the beautiful Snow-white within it, and read what was written upon it in golden letters. Then he said to the dwarfs, “Let me have the coffin, I will give you whatever you want for it.”

Yes, I know, it’s a little strange: what does he want with a dead girl? But fairy tales speak in metaphor: in that language, this is true love, and even death cannot separate you from your true love. Also, you recognize your true love at once. Even if she’s dead.

10. The heroine is revived or revives another.

Here Snow White is the one revived, as Sleeping Beauty is revived. In other tales, the heroine is the one who must revive her true partner, who is in a sort of death.

And now the King’s son had it carried away by his servants on their shoulders. And it happened that they stumbled over a tree-stump, and with the shock the poisonous piece of apple which Snow-white had bitten off came out of her throat. And before long she opened her eyes, lifted up the lid of the coffin, sat up, and was once more alive.

11. The heroine enters her true home.

This is the final home, from which she will no longer need to travel.

“Oh, heavens, where am I?” she cried. The King’s son, full of joy, said, “You are with me,” and told her what had happened, and said, “I love you more than everything in the world; come with me to my father’s palace, you shall be my wife.”

And Snow-white was willing, and went with him, and their wedding was held with great show and splendour.

Here the heroine has claimed her place in the world: she is with her true partner, in her true home. I originally thought the story ended here. But I think there’s another step, one I’m not sure I like!

12. The heroine’s tormentor is punished.

Notice that this final step is in passive voice: the heroine is rarely the one who does the punishing. The punishment comes from somewhere else, and seems almost like an act of fate, although in this case we can wonder if that’s really so.

But Snow-white’s wicked step-mother was also bidden to the feast.

Who bade her, I wonder? She’s the one who decides to go — she need not have gone. Her curiosity about this beautiful queen gets the better of her.

Then the wicked woman uttered a curse, and was so wretched, so utterly wretched, that she knew not what to do. At first she would not go to the wedding at all, but she had no peace, and must go to see the young Queen. And when she went in she knew Snow-white; and she stood still with rage and fear, and could not stir. But iron slippers had already been put upon the fire, and they were brought in with tongs, and set before her. Then she was forced to put on the red-hot shoes, and dance until she dropped down dead.

Who heated the iron shoes? Who forced her to wear them? We don’t know. It’s a cruel ending, but fairy tales tell us that there are cruel endings out there.

I do think this final step is important: it completes the story, makes sure that the good and wicked get what are coming to them. But I have to think some more about how I feel about it!

So, “Snow White” seems to work with the structure I’m developing. The next thing to do is test another tale. Only when I have enough examples will I feel confident that I’m on to something . . .

(The illustration is by Arthur Rackham.)

October 17, 2014

The Heroine’s Journey

This post is prompted by two things:

First, I heard Elizabeth Gilbert say, in an interview, that according to Joseph Campbell there was no such thing as a heroine’s journey, because the heroine did not need to go on a journey: she was the home to which the hero returned. I can imagine Campbell making such a statement, but the evidence in his own book, The Hero With a Thousand Faces, contradicts it: he repeatedly describes heroines on journeys, including Ishtar descending into the underworld. Some heroines have gone on journeys; therefore, the heroine’s journey must exist.

Second, I tried to do some research on the heroine’s journey, and what I found seemed too complicated: it didn’t match up with the journeys I was seeing in the fairy tales I teach.

So I decided to write out a heroine’s journey based on the fairy tales I’m most familiar with. Here’s what I came up with. I describe each step, but sometimes the steps occur in a different order, so the chronology may differ from tale to tale. And not every tale has every step. And not every tale is a journey tale! But when the heroine is on a journey of some sort, this is basically what it looks like:

1. The heroine lives in the initial home. This can be Snow White’s Castle, Cinderella’s house, or the poor cottage where we first encounter the lassie in “East o’the Sun and West o’the Moon.” It’s a place of stability, where the heroine is happy and safe. Usually, it’s the place she spends her childhood.

2. The heroine receives gifts. Sleeping Beauty receives gifts from the fairies, Cinderella from her fairy godmother or alternatively the spirit of her dead mother in a hazel tree. Donkeyskin receives dresses from her father. Sometimes receiving gifts comes before she leaves the initial home, and sometimes after. The lassie receives the golden apple, comb, and spinning wheel after she has lost the temporary home and been left in the dark forest, so rather late in the tale. These gifts will later help the heroine.

3. The heroine leaves her initial home. Sometimes she has to leave because she is fleeing her father, as in Donkeyskin. Sometimes she is given away, like Rapunzel. Sometimes she chooses to leave, like Beauty, to save her father and family. If the heroine stays in her home, the home itself is somehow destroyed: Cinderella’s sense of home disappears when her stepmother arrives and she is made to work as a servant.

4. The heroine enters the dark forest. Snow White and Donkeyskin go directly from their initial homes into the dark forest. The lassie enters the dark forest after losing her temporary home: when her bear husband disappears, she is left alone among the trees. In “Sleeping Beauty,” the dark forest actually grows up around the sleeping princess. Rapunzel enters the dark forest after being expelled from her tower.

5. The heroine finds a temporary home. This can be Snow White’s home with the dwarves, or Psyche’s home with Eros in the old, mythic precursor to “Beauty and the Beast.” It can even be the Beast’s castle. In Donkeyskin, it’s the castle where the heroine serves as kitchenmaid, and in Rapunzel it’s the tower. The important thing is that it’s temporary: the heroine may think she can stay there, but she will eventually have to leave again. Sometimes, in the temporary home, she finds her true partner, but not in the right form or at the right time. Rapunzel meets her prince in the temporary home, but loses him again.

6. The heroine finds friends and helpers. These are dwarves, birds, snakes . . . The heroine finds them and enlists their aid by being kind to them, giving them what they need. And they will help her later on, when she is forced to leave the temporary home and set out on her journey once again.

7. The heroine is tested. Snow White is tempted with the ribbons, comb, and apple. Sleeping Beauty’s test is brief: can she resist touching the spindle? But some heroines go through long, agonizing periods of testing. The princess in “Six Swans” can’t speak for years, and must sew shirts for her swan-brothers. Tests can involve climbing glass mountains, wearing iron shoes, and dealing with ogres. Even Cinderella must get home by midnight.

8. The heroine dies. The tests and trials that the heroine endures include a journey into death. This is perhaps clearest in Psyche’s descent into Hades, but Snow White in her glass coffin, Sleeping Beauty in her hundred years’ sleep, are all versions of the dead heroine.

9. The heroine finds her true partner. This time, he is in his right form: the bear has been transformed into a prince, the Beast is now a man. He recognizes her, just as she recognizes him. It may not seem like much of a love story (the prince dances with her three times, and that’s it), but that’s because fairy tales are told in a kind of shorthand. It’s a convention of the fairy tale that recognition of the true partner is immediate, if he is in his true form. If he is in his false or temporary form, the heroine must learn to see him correctly first. And sometimes he must learn to see her correctly, because she may be in disguise as well.

10. The heroine finds her true home. She had to leave her initial home and find her true partner before she could enter her true home. Now Cinderella can live in the castle, Beauty can live with her Beast, and it’s time for happily ever after.

If you’re uncomfortable with the idea of the heroine finding her true partner (does she really need a man to be her partner?), you can think of it as a metaphor. The true partner is also the other side of herself, so the story shows us the integration of the feminine and masculine, human and animal, sides of the personality. I don’t know, really: I just know that the partner is usually there, that the heroine is eventually united to a prince. Perhaps it means that a union with the right other is one of the highest things we can achieve in this life, perhaps it’s about unity within the self. Either way, it seems to be part of the story.

I do think, looking over this list, that it’s an interesting model for looking at a woman’s life. I know that I’ve been into the dark forest, and through times of trial. I’ve found friends and helpers, as well as temporary homes. But I’ll have to think some more about whether and how this model is useful . . .

This image from the 1920s shows Snow White entering her temporary home (the dwarves’ cottage).

October 13, 2014

Tried and True

Life is uncertain, we know that. We know that we’re on a small blue globe spinning through the darkness of space. We’ve seen maps of galaxies with the little arrow pointing: “You are here.” We know that in a moment, life can change, or end. Our planet can be hit by an asteroid. We can be hit by a bus. We know all that: the uncertainty, instability, unreliability of it all.

Which is why I like finding things that are tried and true. Things I know I can rely on. They’re always small things, because the larger things you can’t rely on: home, love, peace. Those things change and slip away. Come back and slip away again. So I hold on to small things, even silly things, the way a child clutches a favorite blanket or toy. But the small things matter in life: raindrops, fireflies, minutes all matter. If you experience it in the right way, a minute can last an eternity. In the same way, small things can keep you grounded, safely on this spinning globe. They can fill you with happiness.

So I’m going to list some of the things I rely on, and I think you should make a list of your own. What is your tried and true, no matter how small or silly? What do you know will not let you down?

1. Revlon lipstick. The cosmetics company Revlon has been around since 1932, and they’ve figured out how to make lipstick by now. The colors are rich and varied, the lipsticks are moisturizing. And they are cheap. When I wear my favorite color (Fig Jam), I feel adventurous and as though I could conquer the world. Happiness in a tube of lipstick: that’s like a small miracle, really.

2. My rice cooker. I put in dry rice and water, and an hour later I have cooked rice. How perfectly brilliant! Would that other things in life were so reliable.

3. Cotton cardigans. Is there anything better for fall in New England than a cotton cardigan? (I can’t wear wool because it’s too itchy.) You can put it on, button it or not, take it off, depending on the temperature — which, in fall in New England, is unpredictable. The cotton cardigan: an ingenious device that allows you to regular and respond to unpredictability. And it comes in pretty colors . . .

4. Alstroemeria lilies. I know, they’re not the most beautiful flowers. But the most beautiful flowers are delicate — if I bring them home and put them in a vase, they last a day or two. Alstroemeria lilies last, reliably, for a week. And over that week, I can see them open up, pink or yellow or crimson, with green veins. They bring something living and beautiful into my apartment.

5. Cetaphil face wash. If you have sensitive skin, your skin itself, the thing you live in, can be unpredictable. Will we break out into a red rash today? We never know . . . This is the gentlest and most reliable way to clean my face, the face I present the the world and that tells people what I’m thinking or feeling. Considering how much work my face does, I think it deserves to be well taken care of!

6. Agatha Christie mysteries. When I can’t read anything else, when I’m exhausted or despairing, I can always read her mysteries: the gruesome death, the labyrinthine case, the logical deductions. I think it’s because they tell me that in an uncertain world, there’s always an underlying logic, if we can just see it.

7. The sea. All right, this isn’t a small one. But the sea . . . it moves, it has moods, it gets angry sometimes. Sometimes it breaks things. You could say that it’s the principle of uncertainty itself. And that’s why it’s so reassuring. The sea is always different, yet always there. Whatever changes on the surface, underneath the sea is the same. Until our planet itself dries up, it will be with us, in constant motion. By the time the sea goes away, we will be long gone.

8. Ballet flats. You can squash them flat and pack them into a suitcase, and when you arrive in London, they’ll be ready for you. They’ll carry you through cities and down country roads. Sure, there are places where ballet flats are impractical, but I wouldn’t travel without them. With a pair of ballet flats and a pair of Keds, I can go almost anywhere . . .

9. The English language. All right, this is another big one. But it’s like the sea: it’s so uncertain, such a mishmash of other languages, always changing, and yet always the same underneath. It’s reliably unreliable. Cough? Dough? Plough? I mean, really, it’s crazy . . . And yet I love it. (Hungarian, which I also love, is also crazy, in a completely different way.)

10. Timex watches. Time slips away, but a Timex watch will at least tell you what time it is, reliably. Mine don’t even need to be wound. I have two, in case I lose one or the battery stops working and I need another watch to wear while I get it replaced. They are comparatively cheap, and they do what they’re supposed to — tell the time — perfectly. How many things in life can do that?

All things fall, all things change. Which is why we hold on to what we can, whether it’s a favorite shade of lipstick, or a dogeared book, or a walk by the seashore . . .

(This is a photo I took recently, in the park by the Boston Common. That’s the swan lake . . .)

October 9, 2014

Making Mistakes

I’ve been decorating, so I’ve been making lots of mistakes.

The latest is the Mistake of the Bedroom Curtains. Yes, they have names, like Sherlock Holmes cases. The mistake was that I bought the wrong curtains, but it actually all started with the bed.

When I first started decorating the bedroom, I put the bed in a perfectly logical place, close to the window. I added the bedside tables and hung pictures above them. I thought, that’s it: one corner of the bedroom done. And then I realized that late at night, through the wall, I could hear the low buzz of conversation from the building next door. Not words, but the buzz that lets you know a conversation is taking place, like bees in the walls. I don’t know how, since the buildings are a hundred years old and the walls are a foot thick. But then, I have very good hearing. So I had to turn the bed around, which actually ended up being a much better place for it. And the bedside tables had to move. And the bookshelves. So now I had a window with a bookshelf beneath it, which meant rehanging the paintings. I will have to find spackle and paint to cover the initial holes — to hide my mistakes.

But what about the curtains? The first set of curtains I put on the window were dark red cotton, to match the curtains in the living room. But the window in the bedroom is tall and narrow: those curtains blocked out too much light. The second set of curtains were cream, with flowers on them (one of my favorite patterns, Waverly’s Norfolk Rose). They were perfect, but always meant to be temporary because they will eventually be the bed curtains (by which I mean the ones that go over the bed — a bed doesn’t feel finished to me, without curtains). So I bought a third set of curtains, with dark red and cream stripes. I thought, that will match everything else in the room, right? And they did. They matched perfectly, and would have worked, except . . . the room was too dark again. And then I thought, why not get plain cream cotton curtains, just like the dark red curtains I started with — except, you know, not dark or red. By now you’re thinking, I never ever want to decorate with this woman . . . Because yes, I had gone through three different sets of curtains for the bedroom, although the only one I couldn’t reuse elsewhere was the striped set. But I had actually learned something from the experience. Not that I’m incredibly picky when decorating my living space — that I knew. But that the most important thing, for me, was light.

You see, the bedroom is where I have my writing desk, and sometimes I write during the day, although right now I do most of my writing at night. It’s important to me that the room get as much light as possible during the day, although at night I need to close the curtains. The mistake — buying the wrong curtains — led to the realization. So now I have plain cream cotton curtains. If I could, I would have a pattern, because I like patterns. But the most important thing is the light. Without buying the wrong curtains, I would not have realized what I actually valued the most.

And that’s why I’m writing a blog post about curtains: because they led to a revelation. I blame myself for mistakes, beat myself up mentally for them. But the mistakes are actually part of the learning process. They aren’t wrong turns, but how I get to the right place. We’re told to forgive ourselves for our mistakes, but what I’m saying goes deeper than that: our mistakes are necessary. We could not succeed without them. Often, it’s just after doing something wrong that I suddenly realize how to do it right. If you’re not making mistakes, it’s probably because you’re not trying to do anything particularly complicated. Anything at all complicated (in which I include hanging curtains) takes time, and finding the right way to do it — and that usually involves starting with wrong ways.

So what I’m saying is, don’t blame yourself for mistakes. Don’t forgive yourself for them. Thank yourself for them . . . maybe even, if you can, celebrate them. Because without them, you can’t get wherever you’re going.

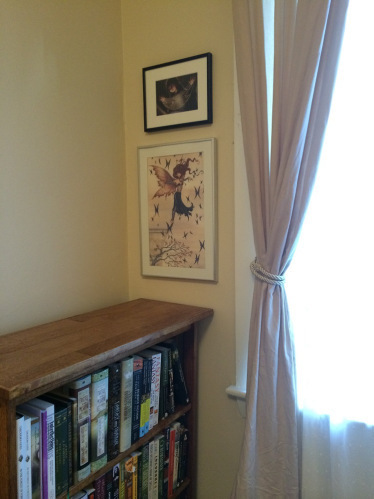

This is the window, and the shelf, and the pictures rehung. And the curtains . . .

October 1, 2014

Pacing Yourself

You can’t do everything.

You can do a lot of things, but you have to pace yourself.