Theodora Goss's Blog, page 75

December 15, 2010

Just Before Modernism

Why is the period just before modernism so important to me? I was watching a show on PBS about Paris in the modernist period. When I turned the television on, it was already on the friendship between Braque and Picasso. I stopped watching at Duchamp.

The art, the poetry, the Paris scene, all were magnificent. But it was as though, despite its magnificence, or perhaps because of it, I had no use for modernism. It was already complete in and of itself, it had already achieved the highest it would achieve. And I could do nothing with it.

I think I keep going back to the period before modernism because it still feels incomplete, filled with possibility. It's still the beginning of something, rather than the fulfillment of it. I find more inspiration in an art nouveau fan than in Les Demoiselles d'Avignon.

I was looking through my photographs from the Museum of Fine Arts and found a few more paintings that I would put in Mother Night's house:

Compared to Picasso, these paintings are pleasant, painterly, tame. And yet they inspire me to write things, whereas Picasso stops me from writing. And in a way, they rather than Picasso are the precursors to an artist like Patrick Dougherty.

Perhaps they represent to me a world in which fantasy is still possible, whereas by the time we get to Picasso and Braque, that world seems to have passed away, as though World War I had killed all the fairies.

Miss Lavender's School

We all came to Miss Lavender's for different reasons, and in different ways.

Emma came because the Gaunts had always come to Miss Lavender's. Her mother had come, and her mother's mother, and her mother's mother's mother, all the way back to the Conquest, when Marguerite de Gaunt insisted on enrolling despite her father's opposition. Back then, Miss Lavender's was one of the few schools that accepted both Normans and Saxons. When I say the Gaunts are wealthy, I mean that they are very, very wealthy. We've all been to their house in Concord and their other house on Nantucket. They've made their fortune in every way possible: whaling and railroads and silicon chips. And don't they know it! Except for Emma, who is refreshingly normal. I mean, I was worried about sharing a room with a Gaunt.

Matilda came because she had to. Her father was a Tillinghast, and the Tillinghasts are almost as old a witch family as the Gaunts. But he decided that instead of managing the family business, he was going to be an artist. And then he married another artist. His parents had died when he was young, and he had been raised by his aunt, old Matilda Tillinghast, in a large house near Boston Common. She believed in duty to one's family, not in going off to North Carolina and painting what she considered ugly, muddy landscapes. So she cut him out of the will. That was all right, until he got sick with one of those illnesses that take all of your money if you haven't got health insurance, which he didn't. And so he died, and Matilda's mother had no money and piles and piles of hospital bills. And then one day she received a letter from old Aunt Matilda saying that she would pay to send young Matilda to Miss Lavender's, and if she did well, she would be written back into the will. No wonder Matilda was in a terrible mood the day she arrived.

Mouse came because she was hiding out. I've told her story elsewhere, in "Lessons with Miss Gray," but I left out a couple of things. Like that her father was a powerful warlock who had gone very, very wrong. Her mother was one of the Wild Women of the Forest, the ones who dress in white and wear shoes of bark. Miss Emily Gray rescued her and brought her to Miss Lavender's. She wasn't actually a witch – witches are always human, and she was only half that. She was more like her mother than her father anyway. But Miss Lavender's was the one place that Miss Gray could look after her and protect her.

And why did I go to Miss Lavender's? The Graves are an old witch family too, although nothing like the Gaunts or Tillinghasts, or even the Sitgreaves before the scandal. And my guardian sent me. "Thea," she said, "Mrs. Moth is willing to offer you a scholarship. It's Miss Lavender's or the public high school, and we both know what that's going to be like." Exactly like the public middle school: more eating lunch alone and "Hey, Graveyard. Seen any ghosts lately?" That's what it was going to be like. Being from a witch family doesn't exactly make you popular in rural Virginia. So I went.

And it's a good thing too. I don't know what Matilda, Emma, and Mouse would have done without me. (Just kidding. They would have saved the world just fine. But I'm glad I went. I would have missed out on so much, if I'd stayed in Stone Gap! And I wouldn't be here in Boston, writing about it for you.)

December 14, 2010

Ask the Cats

"Ask the cats."

"That makes no sense," said Matilda Tillinghast.

"But that's what it says. Do you see a cat anywhere?" Matilda's mother started looking around them, at the sidewalks and the brownstone steps, into the alleys between the buildings.

"Mom, give me that." Matilda took the piece of paper from her and looked at it again. Directions to Beacon Street, right across from the Boston Common, and then to Hecate Lane. And below the directions, a final sentence: "If you can't find the entrance, ask the cats."

"It's supposed to be between these two house, but there's nothing. Just one building next to another. Tildie, look for a cat."

"Mom, that's so stupid. How's a cat going to help us?"

Mrs. Tillinghast stood up, looked back at Matilda, and said, "You're going to have a lot to learn at Miss Lavender's. I wish your father were still with us. I don't know enough to help you understand, but I do know enough to follow directions, no matter how strange they might seem. So make yourself useful and look for a cat, right now."

"Did you require some assistance?" It was a black cat, sitting on the steps of a brownstone, where Matilda could have sworn she had not seen one a minute ago.

"Yes, we're looking for Hecate Lane," said her mother. It had been such a strange day anyway, arriving in Boston by train after leaving North Carolina last night, sleeping dressed and upright in the train seats, and then taking the subway to the Common, dragging two suitcases with all her clothes, everything she would need for school – she was so tired and irritated at the strangeness of it all – that it took a moment for what had just happened to register. A cat had talked to her mother. And her mother had talked back.

"Follow me," said the cat. It climbed down off the steps and then led the way to – well, now there was an alley between the buildings, with a wrought-iron gate that had a small plaque on it saying Hecate Lane. The cat slipped through the bars at the bottom. Mrs. Tillinghast opened the gate and said, "Come on, Tildie."

Matilda looked back at the Common, at the green trees and the statues, at the swank brownstones that lined the streets, at the skyscrapers rising in the distance. This was nothing like Ashton, North Carolina. For the first time that day, she began to feel, not just tired and irritated, but also a little sick.

Dragging one of the suitcases, she followed her mother along the alley between the buildings. Brick pavement between brick walls, until the brick walls ended and then the brick pavement was walled only by hedges, over which she could see a grassy space with tall trees. It was like a small park in the middle of the city, hidden among the buildings. And in the middle, under some of those trees, there was a stone house.

The cat led them up the pavement and to the front door of the stone house. Then it turned and said, "I knew your husband, Mrs. Tillinghast, when he was doing his apprenticeship. He was a good student, although he once accidentally set my tail on fire. I'd like to offer my condolences."

"Thank you," said Matilda's mother. But the cat was already gone.

She knocked on the door while Matilda did her best to get the suitcase she had been dragging up the stairs. The door was opened by a girl with short blond hair, in a green dress. She was by far the prettiest girl Matilda had ever seen. Matilda disliked her already. "Mrs. Tillinghast? We've been waiting for you. And this must be Matilda. I'll show you to your room, and then you have an appointment with Mrs. Moth."

She could at least have offered us something to drink, thought Matilda as she climbed the stairs, the suitcase banging behind her. But when they reached the room, the girl said, "Lemonade and cookies." And there they were, lemonade in a pitcher and a plate of cookies, both on a table around which were sitting three girls.

"Hyacinth, which day is laundry day?" asked one of the girls. She had brown hair and was a little plump.

"Have your clothes in the baskets by Thursday, and they'll come back by Friday. Girls, I'd like you to meet Matilda Tillinghast. Matilda, this is Thea, Emma, and Mouse."

"Tillinghast?" said the plump girl, whom Hyacinth had introduced as Emma. "I know your aunt. Isn't your father the one who –"

"Nice to meet you," said Thea. She had red hair and freckles. "Cookie?"

"Sure," said Matilda. Mouse held out the plate. One more strange thing on this strange day: Mouse was the palest person Matilda had ever seen, and her hair was as white as snow. Her eyes were a startling light gray.

"We're supposed to see Mrs. Moth, right?" said her mother. "Bring some cookies with you. We haven't had time for breakfast," she explained to Hyacinth.

"Thanks," said Mathilda, trying not to stare at Mouse. So this was her room. This was going to be her room for the entire school year, with three girls she didn't know and already didn't particularly like. Unless of course she decided to run away, which was a distinct possibility. As she followed her mother down the stairs, finally without the weight of the suitcase behind her, she felt sicker than ever.

December 13, 2010

Writing Poetry

I had an interesting, writerly sort of day today. It wasn't supposed to be a writerly day, actually. I started the day by grading final portfolios for my classes, and then went into the university to meet with a student and pick up a few portfolios that were coming in late. But before I sat down to grade this morning, while I was eating breakfast, I fiddled with a poetry collection that I'm supposed to be working on, trying to figure out how to get the poems in the right order within their sections. Trying to find a logical flow from poem to poem.

And then, after meeting with the student, I drove to Harvard Square and went into my favorite stationary shop, Bob Slate, which makes the notebooks I use for writing. Spiral bound, narrow ruled, with Bob Slate Stationer written on the cover. And I bought some notebooks, also Bob Slate, small enough so they will fit into my purse. I still remember being in the museum and having nothing to write on. That's not going to happen to me again.

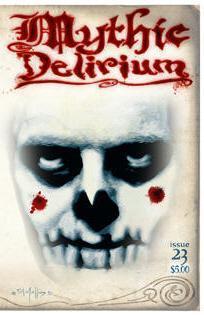

Then I drove home and found a couple of things in the mailbox: the new Locus, a Locus subscription renewal form (which I will of course fill out, because I cannot live without Locus), and Mythic Delirium 23, which you can order through the Mythic Delirium website. Here's what it looks like:

I particularly like this cover because it goes with one of the two poems I have in the issue, "Death." The other poems is called "As I Was Walking." "Death" is a love poem that begins,

The night has gathered around me. I think of Death,

Who breathes so softly beside my ear, like a lover.

Softly he whispers, "This will soon be over.

You will lay those bones and heavy body down."

All my poems about death are personifications, and all of them are love poems. Not because I'm a particularly grim person, I think, but because of all the bad boys out there, Death is the baddest of them all. Don't you think?

Why do I write poetry? For the fame and fortune, of course. (Are you laughing?) But seriously, I write poetry because it's in me, and if I don't get out the things that are in me, I become sick. I think I'm sick now because I have so many stories inside my head, and they're making my head hurt. And I have poems in there too, although fewer than I used to. But I would like to write more.

Yes, I did mention that I'm trying to put together a poetry collection. (Did you pick up on that?) I don't know how it will turn out, and although I have confidence in my prose, I don't have the same confidence in my poetry, primarily because of some negative experiences in undergraduate poetry classes. (Evidently it's fine to write about a Buddhist monk wandering around a hardware store, but not about a woman who, one day, discovers that dragons have moved into her apartment. Small ones. "They got tangled in the hangers." I still remember that line.)

So I'm fiddling and worrying, worrying and fiddling, wondering if I can be excused from writing Significant Modern Poetry if I come out and say, "Look, this is in the tradition of Walter de la Mare, not T.S. Eliot." After all, Jane Yolen and Neil Gaiman write poetry that has a mythic dimension, that has in fact appeared in Mythic Delirium. I'll just go sit at their table, thank you. Where we write poems about witches and ogres, and how to survive fairy tales, and all that sort of stuff.

December 12, 2010

Pollock's Drawings

When we were at the Museum of Fine Arts, I took some pictures of drawings by Jackson Pollock. It was only later that Kendrick, who had read the signs underneath them, explained to me what they actually were.

The first item I saw was not a drawing but a ceramic plate decorated by Pollock:

How strange, I thought, that a serious artist would decorate a plate. But then, at one point Picasso had painted jugs. Perhaps those sorts of things, decorator items, paid well. No, Kendrick said. When he painted that plate, Pollock already had serious mental problems, as well as problems with alcoholism, and a friend told him to try painting on ceramic. So that plate was an attempt to deal with his problems, to get better.

And the drawings, well, they were actually made after he entered a mental institution and started Jungian psychotherapy. They were a part of his therapy. Here they are:

I'm not entirely sure why these struck me so much. I suppose because they made me think about what it's like being an artist of a certain sort. (I make no claim that every artist is like this, only that some are.) There are certain artists whose underlying sensitivity, vulnerability, instability allow them to access certain ideas in a particularly direct way. I think of Van Gogh and Lovecraft, different as they are, as both being in this category. Paradoxically, it's the art that also helps them deal with those particular aspects of their personality. So the temperament of the artist poses a problem that the art itself helps with. There is something in Van Gogh, Lovecraft, Pollock: their work seems to expose an underlying darkness, and a dark order, at the center of the universe. Even Van Gogh's sunflowers are touched by that darkness. It's as though these artists intuited something. In Lovecraft it comes out as shuggoths, which can seem silly. But the sense he has of the universe, of the way it works, the way it's founded on a sort of chaotic order – I relate that to Pollock's paintings.

Again, not all artists are like this. Many of them are perfectly sensible, cheerful, productive people. But there is a place, for certain artists I think, where art both causes the pain and is a rescue from pain. It's profoundly paradoxical, and difficult to deal with I would imagine. Because I can only imagine myself a little way into Pollock's world, or Van Gogh's world. I can imagine myself better into Lovecraft's, perhaps because I'm a writer myself. But Pollock's plate and drawings really struck me, and I thought about them long after we left the museum.

December 11, 2010

Cat's Reading

This afternoon, I went to a reading by Catherynne M. Valente at Pandemonium, the Boston science fiction and fantasy bookstore. I don't usually go to readings, I suppose because what I enjoy is the reading experience itself and what I want are the writer's words inside my head, not echoing in a room at a convention somewhere. But Cat is one of my favorite readers. And she does something that I have always admired, which is incorporate other forms of performance into her readings. The last time I saw her, she was touring with S.J. Tucker. This time, between two of her readings, there was dancing by Katie Lennon. Cat doesn't just read: she puts on a show. I think more writers should do that.

Here are two photographs, one of Cat reading and one of her signing books:

Cat read two sections from The Habitation of the Blessed, which were both gorgeous, as her prose always is. I'm reading the book now, and so far I think it's my favorite of her books.

Afterward, a group of us went out for ice cream, to one of those independent ice cream parlors that have unusual flavors. I ended up with spiced chestnut, which was quite good. And for a couple of hours, we talked shop. Writer's shop is like any other shop. We talk about what we're working on, what we're going to be working on. We talk about publishers, editors, agents. Sales and marketing. What we thought about the carnivorous giraffes in Un Lun Dun. Why no one deals with the fact that Ozma of Oz is transgender, and what we would do with it.

I think it's important to have conversations like these. They give me a sense that I belong to a community, but perhaps more importantly, they give me different ways of thinking about the industry I'm in, which is the writing and publishing industry. There are writers in my field who have done truly innovative things, both in terms of their writing and in the marketing of their work. Cat is one of those, and I've learned so much not only from reading her work but also from watching her approach to her career over the years. She reminds me to be courageous in writing the stories I want to write, and creative in how I get them to my readers. Not a bad lesson to remember, I think, on a Saturday night over ice cream.

The Serial

If you're an observant sort of person, you may have noticed that I have a new button on this website. It's labeled "Serial," and if you click on it, you will see the first thirteen of my posts about the Shadowlands and the Other Country. Enough of you said you were interested in those posts and wanted to hear more of the story that I thought I would put it all together for you. That way, if you just came in, you can go all the way back to the beginning. And you won't miss anything, because after posting on my blog, I'll repost under the Serial button. (It may take a while, but it will eventually appear under Serial.)

Original posts will still appear on my blog, because this is a story I'm telling in real time, as I think and feel it. Or it's a story that Thea is telling, and perhaps all of my posts are really her posts, and Dora is just a character she's creating. I'm not sure which would be the best option, really.

The first part of the serial, made up of those thirteen posts, is called "Into the Other Country," and it's about how Thea traveled to Mrs. Moth's house, and then told the story of the last time she had been there, when she accidentally found herself in the Other Country. She visited Mother Night's house, had several conversations, including with Cordelia the cat (who is as obnoxious in real life as she is in the story), danced with Merlin for the first time, and then returned to the Shadowlands having learned something about herself and her purpose in life. I wasn't thinking about these posts as part of a story when I wrote them. I just wrote them when I was in a particularly dark place and needed somewhere else to go, and the Other Country looked so enticing, with its house of stones and dragon bones, and its trees with leaves and flowers that never fall, and Mother Night herself, who knows the pattern we are all part of, even if we don't know it ourselves.

But I think the next part of the story will have to do with Thea's adventures in the Shadowlands, because as I think I've mentioned, she and her friends, Matilda, Emma, and Mouse, have saved the world several times. And I still need to figure out how.

It's been a new and interesting experience for me, committing to writing on this blog every day. It means that I have to write, no matter how I feel that day. And how I feel seems to find its way into these posts, whether through a story or simply an account of me looking at myself in the mirror and thinking about the future I want to create. Being a writer, or at least the kind of writer I am, anyway means living with one fewer layer of skin than other people seem to have, experiencing the world more directly – sometimes more joyfully, sometimes more painfully. And it means writing out of that, transforming personal experience into stories. So I don't know where these posts about the Shadowlands and the Other Country will go. There is no larger plan, just what I think about on any particular day. I hope you enjoy the journey.

December 10, 2010

The Horrible Year

Today, at the university, I looked at myself in the bathroom mirror. There was Anxiety at my left shoulder, and Depression at my right. Insomnia was at home, taking a nap so she could keep me up later.

And a thought came to me. It was, "You will never do anything harder than this."

I've done some difficult things in my life. I've gone to Harvard Law School. I've passed the New York and Massachusetts bar exams. I've worked for four years as a corporate lawyer, in Manhattan and Boston. One memorable day, I billed twenty-three hours (out of a possible twenty-four). But I haven't done anything as difficult as my doctoral dissertation. This is as hard as it gets.

The Horrible Year is not a specific year, but a concept. It refers to the fact that, any time I have tried to change my life in a significant way, it has taken me a year longer than I anticipated. The first time I applied to graduate school, desperate to leave the law and study literature, I did not get in. Although I had a perfect score on my subject GRE, my essay was all wrong, not at all the sort of essay the schools were looking for. I had to wait and apply again. But the second time, I not only got into almost all the schools I applied to, I also received a full scholarship and a stipend high enough that I was able to attend Odyssey one year, and Clarion the next. And because I spent that extra year, that incredibly depressing extra year, working as a lawyer, I was able to pay off all my law school loans. So in the end, the Horrible Year was good for me, as thoroughly unpleasant things sometimes are.

I'm in the middle of a Horrible Year, teaching full-time and revising my dissertation and yet at the same time trying not to let my writing career, which matters to me more than almost anything in the world, slip altogether. But I keep reminding myself that the Horrible Year ends, and although this is the most difficult thing I will ever do, it's also the foundation on which I will build all the wonderful things, all the things that will become the life I want for myself. With a Witch's Cottage, and books that people will want to read, and the freedom to pursue all the projects that I've wanted to pursue for so long. And contentment, adventure, and perhaps, yes perhaps, even joy.

Take that, Anxiety and Depression and Insomnia.

December 9, 2010

Teaching and Writing

I'm tired today, so tired that I can barely put two sentences together. In a way that makes sense, that does not seem completely random, I mean. Which is, of course, a skill I teach my students: I call it flow. To make sentences flow, you pick up a bit of what you said in the last sentence and then add something new to it. I would say it's like doing a chain stitch, but most of them have no idea what a chain stitch is.

Tomorrow is the last day of the semester. I get like this toward the end of the semester, when there's so much work to do that I'm not getting much sleep. Today I held office hours for four extra hours, just in case any of my students needed help with their final papers. I'm not giving them any excuses: if a paper doesn't work, it's not because I wasn't available to tell them why. Teaching takes energy and dedication and a judicious use of similes.

(At the beginning of the semester, I tell my students that writing is a system of black squiggles that we use to conveying meaning. In other words, writing is itself, ab initio, an insane enterprise. And we go on from there.)

But what I really wanted to write about was how teaching has affected my writing. Those of you who are teachers may be able to relate to my experience.

I spend hours and hours every semester correcting student writing. I have been trained to do it, I have also trained myself a great deal. In order to do it well, I have to know all the rules, why commas go where they go, why a paragraph lacks unity, why a sentence does not make sense. ("What is your sentence about?" I ask. "Well, is that also the grammatical subject? If not, why not?") Teaching writing has taught me so much about writing. Perhaps what teaches me most, however, is seeing the terrific paper, the automatic, don't-have-to-think-about-it A paper. With apologies to Tolstoy, all A papers are A papers in their own way. They don't just lack mistakes. They have something extraordinary about them, a level of engagement with the texts, a felicitous style. They grab and keep your attention, and it's interesting to think about what does that. Usually, I think, it's the student's voice. The student already has an individual voice. The student is already thinking, and writing, in his or her own way. There's an enormous pleasure in seeing something like that.

I wouldn't be the writer I am, if I weren't the teacher I am, I think. I wouldn't construct sentences the way I do, I wouldn't think so often about technique or have a certain facility with it. I wouldn't be able to write in so many genres, poetry and short story and essay.

At the end of the semester, when all I want to do is sleep, it's useful to remind myself of this.

December 8, 2010

Impressions of Sargent

This title is a pun.

Not a very good one, I'm afraid. It comes from an article I read in the New York Times about John Singer Sargent. Apparently, after the scandal following his showing of Madame X, Sargent was so disheartened that he began to paint like an impressionist. He even studied with Monet. I suppose he thought that he would try the artistic style of the moment.

The problem is, the paintings are dreadful. Sargent was a very bad impressionist, a second-rate imitator of Monet. The only one of them that is even passable is his painting of his friend, the artist Paul Helleu. Most of the paintings mentioned in the article and included in the slide show are flat, boring. The light is harsh. He lacks the delicate touch, the vibrancy, of the real impressionists. (The worst of them, I think, is this painting of trees on a riverbank. I mean, seriously?)

It is when he incorporates impressionistic techniques into his own style that he becomes interesting again, as in the paintings below. I took these photographs at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, in the Sargent room:

I particularly like this last one, a watercolor of light on a wall:

My apologies, once again, for the blurriness. There are better examples of all of these paintings online. But what I take away from these paintings is the importance of finding your artistic self. Imagine, after painting Madame X, which is one of his masterpieces, Sargent painted the garish impressionist landscapes featured in the New York Times article. It's as though he lost confidence in himself, and so he tried to be someone else. That doesn't work. As you experiment with technique, and you should always experiment, you have to remember who you are, incorporate what you have learned into yourself. You have to have confidence in your particular vision and style.

Of course that is easier said than done, isn't it? And I should say, of style, that it's not something you choose, arbitrarily or in an artificial way. You don't write in a style. You write as you, as yourself, in your own voice. And that becomes your style. I've mentioned several writers who have their own distinctive styles. I know some of them personally, and those styles are extensions of who they are, of their personalities, the way they view the world. So finding your style – it really is finding yourself, discovering who you are. (Which may be different than who you think you are. Writing is surprising like that. I know that I'm a much more realistic writer than I ever thought I would be – and more literary.)