Theodora Goss's Blog, page 72

January 10, 2011

Death on the Nile

I was sick today, so after I got dressed this morning, I went back to bed, lay under the fuzzy blanket, and read Death on the Nile.

I'd read it before – I think I've read every Agatha Christie mystery. I like reading them again because I always notice new details, and they've become textbooks for me. Christie is so good at creating plots and leading readers through them. So I read her for lessons in plotting and in how to direct the reader's attention.

Today I noticed something that I've noticed before, which is how quickly she sketches characters. She does it by appealing to stereotypes we have. Her characters are all stereotypes in a way. In Death on the Nile, Linnet Ridgeway is the beautiful blond heiress. Christie sketches her quickly by having her wear a simple white dress that only certain other female characters realize is phenomenally expensive. When we are told that, most of us instinctively know exactly what Christie means. We've seen such dresses and know what sorts of women wear them. And if we haven't – well, in a sense Christie indoctrinates us into a world in which there are such women, and we begin to understand the code. We begin to understand that certain things mean certain other things. As Hercules Poirot points out, the fact that Mr. Fanthorp wears an Old Etonian tie means that he simply wouldn't interrupt a conversation taking place between people he doesn't know – and the fact that he does is therefore meaningful.

Characters in Christie fit into these stereotypes. And I was thinking, while I was reading, of the extent to which we use such stereotypes in real life. I don't mean simply to think about other people in stereotypical ways. I mean to project ourselves, our sense of who we are. It's as though appearance is a series of codes. We know the codes (although different people might know different codes), and we use them to create our public selves.

For example, when I was a lawyer working in Manhattan, it was obvious that the female lawyers and the (almost all female) secretaries dressed differently. The secretaries tended to wear dresses. The female lawyers tended to wear suits. The secretaries wore more and different jewelry, typically more expensive. The female lawyers wore fewer pieces of jewelry, smaller pieces, often pearls. (Did you know that there is a whole subset of the female population that is given pearls? Typically for a teenage birthday. I was given pearls for my sixteenth birthday. But Ophelia was given hers at her christening.) There were differences in hairstyle. Even the hands: secretaries often had painted nails. Lawyers never did. (My mother lectured me when I was a teenager and wanted to paint my nails. Professional women, she told me, do not paint their nails. In an Agatha Christie world, she would have been telling me that ladies never do.)

I've always been fascinated by these codes, probably because I was an immigrant, and therefore a social outsider. Social outsiders tend to notice the codes of the society they're in. With these codes, you can establish who you are, because people recognize and read them. (They tend not to acknowledge them, except in movies in which the secretary becomes a powerful businesswoman. Then you will see her transform, her hair and makeup change, her clothes change. With absolutely no discussion of how appearance is read, particularly as a marker of social and educational class. We don't like to talk about social class, as Americans.) And you can play with the codes. There are people who are more difficult to read because they're deliberately playing with the codes. They tend to be creative types, the CEO of the computer company who wears jeans. But probably a specific brand of jeans, because even people playing with the codes usually want to signal that they know the codes, they're just being rebellious and cool. Unless they are genuine eccentrics. Artist are genuine eccentrics. They will present themselves in ways that don't make sense in terms of any of the codes. They have a tendency not to care, or to create their own codes.

All of which has to do with how you can present your characters.

For Christie, the stereotypes are actual identities. That's part of the detective fiction genre. For Arthur Conan Doyle too, as well as for Dorothy Sayers, people tend to behave as they should according to type. If you know their type, you know how they will behave.

But for us, the stereotypes are about self-presentation. We can use them to talk about how a character thinks of herself. A character with a nose ring, for example, is presenting herself differently than a character wearing a string of pearls. They are both appealing to and using stereotypes to help create the identities they present to other people. It's not about who they are, but about who they think they are and want to be.

How am I dressed today? In what has become a virtual uniform this past year: jeans, a long-sleeved cotton t-shirt (navy blue), white Keds. Small silver earrings, a Timex watch. With my hair caught back in a silver clip. It's preppy, academic, Lexington. It says that I'm likely to read long books and watch independent films. If it's an indicator of social class, I would call the class "overeducated and underpaid." Of course, it's also comfortable. But that's part of the stereotype as well .

I wonder what sort of murder I would commit in an Agatha Christie mystery? I might murder another writer. Probably using some sort of poison, a classic like arsenic or digitalis from foxglove leaves. Or I might murder someone over a bad review. But I would certainly behave according to type.

January 9, 2011

Magical Places: The Garden

Of course, my favorite part of Morven was the garden. This is a view of the house from the front. It's a typical old Virginia house: red brick, white columns.

And here I am, sitting on the front steps:

I love stairs that are placed directly into the grass.

In one direction, the ground slopes down to orchards.

In the other direction, there are alleys that lead to various gardens.

Moss on the roots of a large tree. You could see this in a forest in the Other Country, couldn't you?

Two fountains. I particularly like the second one. Water comes out of the figure's mouth, and his chin is all covered with moss. It's actually a bit creepy.

I love alleys of various sorts. This trellis is covered with canes of roses, but they weren't blooming this late in the year.

And I love vistas.

And stairs of various sorts. Having to step down or up in a garden always makes walking through the garden a bit of an adventure. And walls. I got used to walled gardens at the University of Virginia, and I've always thought that a wall makes a garden mysterious. Perhaps because I remember reading The Secret Garden as a child?

This waterlily garden was my inspiration for a particular scene in the Other Country, the one where Thea is talking with Cordelia the cat. Of course, that garden is much larger. Remember that everything in the Shadowlands is a shadow of what it is in the Other Country. It's diminished, not as intense.

Finally, there were some perennial borders, although past their peak, because it was so late in the year.

And a garden of hydrangeas, just hydrangeas. Which I think is a rather interesting idea.

What do you think? Would a garden like this inspire you to write a story? What story could you set in a place like Morven?

There you go: I've just given you another exercise!

Magical Places: The House

Remember where I was standing in the last series of pictures, with the hills behind me? I was facing the back of the house. This is what it looks like:

When you go in, you see a series of rooms. A dining room, with wallpaper detail:

One parlor, with fireplace detail. This is actually a long double parlor.

Another smaller parlor, with tapestry detail:

Then we went upstairs. Here you can see various bedrooms:

I couldn't resist including a bathroom. Doesn't this look luxurious?

Two more bedrooms:

The view down the stairs from the third floor. This is the sort of thing I like to describe in a story.

And finally, a window on the third floor:

Magical Places: The Drive

Do you remember when I wrote about going to the museum, and how important that is for a writer? Well really, I think a writer has to go all sorts of places. In late summer, while I was in Virginia, I was given a tour of Morven, which is one of the old estates close to Charlottesville. It used to be a private estate, but has now been sold to the University of Virginia. Guests stay there, and there is a conference center.

I thought I would post some photographs, because places like these give me ideas for settings in stories. From Morven, I could create quite an ordinary house belonging to a wealthy family. Or, as you will see once we get to the garden, I could create a place in the Other Country.

Let's start with actually getting there. Here is the drive up the mountain:

Here is the carriage house that is now a conference center. Once upon a time, it used to house a collection of carriages. Inside, there are still photographs of prize-winning horses that were bred and trained at Morven.

The Morven pennant.

Aren't these strange? Sculptures in the shapes of horses' heads.

The view from the top of the mountain. We were surrounded by about six thousand acres.

And your photographer, read to go into the house.

January 8, 2011

Unicorn Apocalypse

If you remember, in my last post I wrote about a unicorn apocalypse. I described how it might happen, in an American suburb with ornamental pears in the front yards and swimming pools in the back, the azure that swimming pools are in the suburbs. You can imagine unicorns swimming in that azure water.

Well, I read the post again and realized that my unicorn apocalypse wasn't really mine. It wasn't in my voice, wasn't a story I would actually tell or be interested in telling. It was a unicorn apocalypse that anyone could create.

So I started thinking, what would my unicorn apocalypse look like? This may sound silly, but: how would Theodora Goss write a unicorn apocalypse, really?

And I realized that my unicorn apocalypse would take place in fourteenth-century France.

I'm making this up as I go along: my heroine would be Marguerite, the daughter of the local lord, Guillaume du Pré. She's thirteen and she needs a love interest, so let her have a crush on Henri, the falconer's son. He's fifteen and considers himself far too old to be bothered with her.

Where do the unicorns come from? Guillaume has accused Marguerite's mother, his second wife, of adultery. He married her when he was old and she was young. She bore him a child, but he suspected that she was in love with one of his knights. Guillaume sent him away, on an errand to the king's court, and now he has shut his wife in the dungeon and intends to have her burned in the middle of the village.

You can already see the French countryside, the castle in the middle of its fields, the forest in the distance. The village close to the castle, its church, its smithy, the dusty streets between houses. Boys leading cows to pasture, chickens pecking whatever they can find. Wives sitting by their front doors, spinning or sewing. The villagers are frightened of Guillaume. He is a hard master, and Marguerite's mother, whose name should be Lille, is loved in the village.

When she came to the castle, she brought with her, as part of her dowry, a unicorn tapestry. The unicorn is part of her family's crest. The motto on the crest is "I will come." (I would have to look that up in French. I think it's something like "Je viendrai," but it would have to be in medieval French, of course.)

Unicorns start appearing. They trample the cabbages. (It is fall, I think. I always have to be careful about details, think about when the cabbages will be large enough to pick. Because we live in a society in which there are always cabbages in the stores, and of course that isn't the case in fourteenth-century France. The loss of cabbages is an important thing, in fourteenth-century France. It means you may not make it through the winter. But when I write, I have to remember, at least approximately, what grows together. And of course, not to put in any vegetables that aren't grown in Europe until after the discovery of American! But you're always safe with cabbages.)

There are, of course, attempts to eradicate the unicorns. Marguerite is called into service as virginal unicorn-bait. There are arguments as to who is and is not a virgin. (Some things don't change in six hundred years.)

The unicorns are dangerous, and they can't be captured. And they cause a lot of damage. The villagers are caught in the middle of this situation, as they always are: affected by it even though they're generally sympathetic to Lille. Finally Guillaume decides that he's simply going to burn her, which should get rid of the problem.

There has to be some sort of dramatic final confrontation, where Lille's knight rides back and the unicorns appear and Guillaume is speared in the chest with a unicorn horn. But the main story has to do with Marguerite's experience of this conflict between a father who frightens her and a mother who is beautiful, but whom she barely knows. She herself has been raised mostly by a nurse, and I think I will make her nurse an important character, someone who can tell Marguerite what is happening in the village, how this conflict between nobles is affecting the lives of ordinary people.

That is how I would write a unicorn apocalypse. (How does it end? I'm certainly not going to tell you. Wait for the story, although this one will need a lot of research. Because when I write about fourteenth-century France, I want to get everything right.)

Note: I just found, and had to link to, John Ginsberg-Stevens' unicorn apocalypse. If anyone else writes a unicorn apocalypse, let me know and I'll link to it as well!

January 7, 2011

Writing Exercises

Charles Vess is one of my favorite contemporary illustrators. If you're not familiar with his work, do click on the link and take a look at his website. He did the gorgeous illustrations for Stardust, by Neil Gaiman, which are so much better than the movie. Charles also did the cover illustration for my chapbook The Rose in Twelve Petals and Other Stories, which came out many years ago from Small Beer Press (and sold out very quickly, mostly I think because of Charles' illustration). You can imagine how excited I was when I learned he was doing the cover!

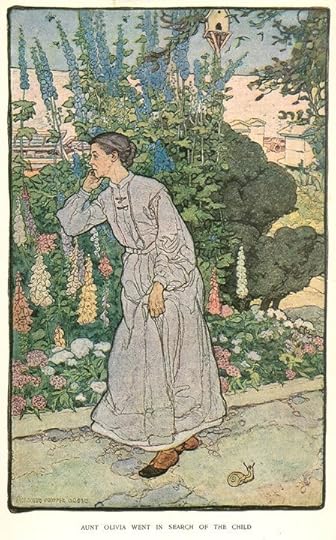

Well, recently Charles has been posting a series of illustrations by his favorite illustrators, mostly from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They're on Facebook, so you'll have to become Charles' Facebook friend to see them. But one of them in particular gave me an idea for a writing exercise. Here it is:

This illustration is by Elizabeth Shippen Greene, who was a prolific magazine and children's book illustrator at the turn of the century. What caught my attention about the illustration is that it's clearly telling a story. Aunt Olivia went in search of the child, but what child? Where did the child go? And how did Aunt Olivia manage to lose him?

Looking at Aunt Olivia in the illustration, I get a clear sense of who she is, of her life probably with her brother's family, where she has a small room in the back of the house and helps out in various ways, including by looking after her brother's children. But one particular child, a young boy I think, in a sailor suit and with curling hair that's often rumpled by the wind, is a handful. He wanders off the moment you turn your back, and when you find him again, he's eaten all the jam or is covered with bees, or crying up a tree because he can't get down. But this time – I think he's gone somewhere different, because haven't goblins been seen in the neighborhood? And maybe the goblins took him. Aunt Olivia was supposed to be looking after him, and now she doesn't know where he is, and she's just going to have to go after the goblins to get him back.

Aunt Olivia looks as though she's a gentlewoman, as though she's behaved properly all her life. But honestly, I'm putting my money on her. I think the encounter with the goblins will teach her exactly what she's made of, which is stronger metal than she thought. And at the end of it, she may decide to leave her brother's house and set out on her own, because she realizes that she's reached the age when it's time for adventures.

I also wonder what the snail thinks about it all. If I were to write this story, I think I would need to have a sentence or two in which I go into the point of view of the snail, just as J.R.R. Tolkien goes into the point of view of a fox, just for a moment, as the hobbits are leaving the Shire in Lord of the Rings.

So here is my suggestion for a writing exercise. Find an old illustration. Don't read the story it's illustrating. Instead, write a story of your own that goes with the illustration. See what you can come up with. (Then you can read the story.)

I did call this post writing exercises, so I should include more than one, and I do have another one for you. This one is inspired by Holly Black's list of Ten Reasons Why Unicorns are Better Than Zombies. Here's reason number four:

"As a kid in Baltimore once wisely pointed out, there's a lot of speculation about what a zombie apocalypse might be like, but imagine how much more awesome a unicorn apocalypse would be."

The exercise is to imagine a unicorn apocalypse, and then write about it. What would a unicorn apocalypse look like? The point of this exercise is to imagine something completely incongruous, to the point that it sounds silly, and treat it with complete seriousness. Yes, you must take the unicorn apocalypse seriously.

My unicorn apocalypse? In a suburb, the sort where people drive the girls to soccer in minivans, people begin seeing unicorns. A unicorn standing in the front yard, beneath an ornamental pear. Two unicorns splashing in the swimming pool. A small herd galloping down Poplar Street in the early morning. More and more unicorns, until the residents don't know what to do with themselves, don't know how to handle this sudden invasion. And the unicorns are beautiful. They lie on the laps of virgins. (Imagine the comments that causes, in a suburban neighborhood!) But once the residents try to get rid of them, they become violent. The unicorn is a savage beast, not a horse but a creature that can fight a lion. My point of view character would be a teenage girl, the kind who has unicorn posters on her walls. What will she do in the unicorn apocalypse? Which side will she choose? You'll have to wait for the story.

January 6, 2011

A Gill of Pickled Shrimp

Do you know what I'm referring to? In one of the Agatha Christie mysteries, Miss Marple mentions a gill of pickled shrimp. I think it went missing from someone's string bag, and she figured out where it went. For me, the words "gill of pickled shrimp" refer to a mystery that you solve the way Miss Marple solves mysteries, by noticing small details that allow her to reconstruct a sequence of events.

I'm pretty good at that. There are plenty of things I'm not good at, but I'm actually pretty good at inductive reasoning, which is the sort of reasoning that Miss Marple uses, and Auguste Dupin, and Sherlock Holmes. And I'm usually right. I'm also pretty good at understanding people, what they're thinking at any particular time, what motivates them, what they're likely to do.

I hope all this allows me to write good detective stories, because I'd like to write detective stories one day. I already have a detective. And a lovely series of murders all planned out.

I was thinking today about what I had learned from Agatha Christie, and I've actually learned a great deal from her about creating characters, not so much from how she creates characters, but from what Hercules Poirot and Miss Marple tell me about characters. For example, here are some things they've told me:

1. Everybody lies. That's true, isn't it? It's a sad thing to realize, but if you pay attention to human interactions, and if you want to be a writer, you need to pay attention to human interactions, you'll realize that everybody lies. All the time. Most often, people lie to themselves. So when you're writing a character, you need to ask yourself a couple of questions. Who is my character lying to? And why?

2. Everybody is motivated by self-interest. Again, sad if you consider it from the perspective that we're usually taught to. We're all supposed to be honest and altruistic, aren't we? But we're not. Honest and altruistic characters are interesting to write because they're so unusual, you almost need to make something wrong with them, like being aliens or something. Otherwise, readers won't believe in them. They will read as false.

3. Everybody acts within character. What I mean is that people are mostly consistent. They think and act in the ways they're used to, out of habit. If someone acts out of character, there is usually something going on, something unusual prompting that act. This is not to say that people can't change, but that they usually need significant motivation to do so, and once they have changed, they settle into a new set of habits. Motivational speakers know this. That's how they make so much money.

These are probably not very nice things to say about people, but as Miss Marple says, murder is not very nice. In a way, neither is writing. If you want to write realistic characters, you need to make them lie, act out of self-interest, and act within character unless there is a significant motivating force making them act differently.

In other words, you need to know people and represent them realistically.

Sitting here writing this, it occurs to me that knowing people is really the key to writing a murder mystery. It's not about the clues or the crime, about the mystery you've created. It's about the people involved in that mystery, what motivates them. How they respond.

I have to confess: sometimes I watch 48 Hours Mystery, which is always ridiculously melodramatic, and in which you can always guess whodunnit. (They're not interviewing the wife, so it's her. They don't want to show her in the prison jumpsuit too early in the show.) Just as you can always guess on the CSI shows. (It's the woman who used to be on that other show, you know, the famous actress.) And that's what I'm interested in, the motivations. Why do people do the things they do? More than the specifics: how does arsenic actually affect someone? Although even those details are useful and give me ideas for plots.

I hope that someday you'll get to meet my detective. Her name is Darcy Chase, and her father used to write murder mysteries. But she's the real thing. And she's very good at inductive reasoning. She could tell you who took the gill of pickled shrimp, just like Miss Marple.

January 5, 2011

Agony and Ecstasy

Did you think, reading the title, that this post was going to be about completing projects? Well, it is.

I completed a project today: I sent off my Folkroots column. I had been working on it on and off for a couple of weeks now. It takes me about two weeks to write a column like this, because there are all sorts of steps, like the going to the library step. And most of my time is taken up by the dissertation.

Today was the deadline, and I had about another 300 words to write. But I started by reading over the entire column from the beginning. It's in three sections: a short introductory section, a section on the vampire in folklore, and a section on the literary vampire. I had finished the introduction and folklore section. There was just the literary section to finish. I had to say something more about "Carmilla," and then something about Dracula.

So I started by reading it over from the beginning, making sure the first two sections sounded good. And they did. Then I wrote the paragraphs I needed in the second section. That took a couple of hours. If I were writing a story, three or four paragraphs would not take a couple of hours. But I was looking for quotations, checking my facts, even checking dates. And I was thinking, to what extend does folklore come into "Carmilla"? Isn't it really in Dracula that we get the vampire of folklore, which is bound by rules? And doesn't that come from the fact that Bram Stoker read Emily Gerard's The Land Beyond the Forest, about the beliefs and customs of Transylvania? So there I was, writing the last few paragraphs. I got to the point where I knew I needed just one more. And I thought, I'm almost done!

When you think this, as you're completing a project, know: you're not. The agony is coming.

It was time to make sure my endnotes were all in Chicago format, and that took at least an hour. And then I had to make my list of suggested readings. That wasn't particularly difficult. But when I was done and I looked at the word count, I realized I was already close to my limit (even the limit over the limit that I'm allowed when I really, really need it: 4000 words is the limit, but I can go to 4500).

So I wrote that last paragraph, and I thought it was pretty good. But sure enough, when I checked the word count, I was over by at least 150 words. What to cut?

So I printed out the manuscript and read it over. I could see some things to cut in the column itself. And I could cut some of my suggested readings. So I cut, and then I checked the word count again. And realized that my current program calculates in the endnotes. I don't need to do it myself. My word count was off by about 200 words.

Which meant that I hadn't needed to cut anything after all. I went back and looked at whether there was anything I wanted to add back in. And I added the suggested readings back in. About 4100 words. Perfect.

I was also responsible for providing the images to accompany the column. I already had copies of most of the images I wanted. But one of them I simply could not get into the proper format, and it wasn't that vivid or informative anyway. And I wanted a better image of Vlad the Impaler. And was there perhaps an image of Carmilla out there? Well, there was. Finally I had the five images I wanted, all out of copyright, all formatted correctly (as .jpgs).

I read over the column one more time, made sure I had caught all the typos I could possibly catch, and then sent it both as a Word document and a PDF. There are some tricky accents in there, and I want to make sure they appear correctly. The PDF will help if anything in the Word document is confusing. (Have I already explained the extent to which I despise Word? Well, I do.) Just before sending the column, I realized that I had saved the Word document as .docx, not .doc, and that had been a problem last time. So I saved it again, attached it again. And sent it. And sent the images separately, in case there were file size problems. Everything was sent.

Ecstasy.

For about five minutes, until I realized that the column would read better if I added a sentence just before the final paragraph. So I'm going to look at it one more time tonight, to see if that sentence is actually necessary. (I think it will be. How annoying.)

And that's where I was, three hours after I had thought I was almost done. With a throbbing headache and an aching back.

The agony and ecstasy of finishing a project. I must say, it does help to be able to complain about it.

January 4, 2011

Elegance

One of my favorite bloggers, Hecate, wrote a blog post called "Elegant," about the concept of elegance.

Here are a couple of quotations.

She quotes from Matthew E. May, the author of Elegance and the Art of Less: Why the Best Ideas Have Something Missing:

"Something is elegant if it is two things at once: unusually simple and surprisingly powerful. One without the other leaves you short of elegant. And sometimes the 'unusual simplicity' isn't about what's there, it's about what isn't. At first glance, elegant things seem to be missing something."

And then she herself says:

"Elegance, I want to say, matters. And, although life is messy, an elegant life is unusually simple and surprisingly powerful. Like good legal writing, like good magic, an elegant life takes two things. The first is a blindingly clear objective. And the second is ruthless editing. Like good real estate, which is location, location, location or like getting to Carnegie Hall, which takes practice, practice, practice – elegance takes editing, editing, editing. Take things out. Remove the extraneous (which requires you to know the essential). Get down (as we do in Winter in the garden) to the bones."

These quotations struck me in particular because I think they have to do, not only with how I try to live my life, but also with how I try to write. In a recent interview for Clarkesworld Magazine, I said that I do not try to write beautiful prose, and that's true. I don't try for beauty. But I think I do try for elegance. And Hecate is exactly right, it takes ruthless editing.

Even writing this blog, I find that I'm continually editing my sentences, trying to make them simpler and more powerful.

How to be elegant?

I look around this room, and it seems elegant to me. The furniture, all of oak and ash, the cream-colored carpet and walls, the green bedspread and cushions. I have edited the colors so that nothing jars, nothing clashes. The paintings on the walls are like windows, looking out at lakes or flowers or fantastical scenes. There is, alas, currently an excess of paper on the desks. I could clean up, but instead I think I'll make the room more elegant – same thing, but doesn't the latter sound finer? And of course books, the books I love most, and so already carefully edited, perfectly elegant.

And sitting here writing, I feel elegant. Black turtleneck, slim jeans, a thick black leather belt. Marcasite earrings in the shapes of dangling flowers. Perfume, of course, light and gingery.

Are my words elegant? I try to make them simple and powerful, and perhaps that achieves elegance. At least I hope it does.

If this blog post were truly elegant, it would have ended with the sentences above. Don't they end the post almost abruptly, leaving you wondering if perhaps there is more? If I meant to write another sentence? That, at least, is what I was aiming for. But today I want to end with one other quotation.

So many of you have read the post I wrote yesterday, "Write Every Day"! I hope it helped you, as much as writing it helped me. I think all of us need that sort of encouragement, that sort of reminder sometimes. I particularly liked something that Nathan Ballingrud wrote about my post, in a post of his own called "The Beautiful Grind." So I'm quoting part of it here:

"Theodora Goss wrote on the subject of writing every day on her own blog yesterday, comparing it to keeping the body in dancing shape. It's a terrific analogy, because it illuminates the fact that what we're training ourselves to do is more than just stay in shape, whether as writers or dancers or what have you. I'm a good enough writer that I can not write for several months and still sit down and compose a solid and well-written draft. What we're training to do, though, is to be better than in shape. We want to be remarkable. We want to be like nothing else anyone has yet seen.

"I'm getting an object lesson in the consequences of neglecting that exercise. Language moves around in unexpected, disorienting ways. There are days on which it seems that I've forgotten how to make sentences work. Words are strange and unwieldy. English is a sluggish, petulant beast."

We do want to be remarkable, don't we? We do want to be like nothing anyone else has yet seen. And I think part of that is elegance, because elegance is individual. Editing implies choice, and choice is always individual, because it's based on our objectives. Hecate says that the first component of elegance is a blindingly clear objective, and that's the first thing we must define: the objectives of our lives, of a room, of a story.

That's what I need to do in my own life, define my objective so that it is blindingly clear, so that I know the essential and can remove the extraneous. My objective has to do with writing, and once I began to understand that, I could begin to define what was essential, like writing here every day. Because Nathan is right, language has a mind of its own, and writing is a sort of compromise between the writer and language. The more I write, the more I learn how to move in language, as a dancer moves elegantly across a floor. The more language and I move together. So that it's not a sluggish, petulant beast, but my partner.

January 3, 2011

Write Every Day

Once upon a time, I worked at a law firm in Boston, in the financial district.

I went into the law firm in the morning, and I came out in the morning, usually about 2 a.m. When I came out, I got into a car that drove me home. Law firms of that size pay for a car to drive you home, if you're there past a certain hour. I was often there past that hour. And they pay for dinner as well, if you're there at dinner time, which I almost always was. So I drafted documents, and ate take-out, and didn't get enough sleep.

I was in terrible shape.

That was when I started taking dance classes. And since I'm me, I started taking dance classes at the Boston Ballet School. I had taken ballet as a child, but I had not danced for years, so it took me several months to learn the steps and positions again. And it took me that long to get back into the shape I needed to be in, to dance.

One of the interesting but also intimidating things about the Boston Ballet School is that you're among the professional dancers. They pass you on the stairs, but also they sometimes take the beginning or intermediate classes, particularly after they've been injured and need something easier to do. Because they, of course, dance every day.

I danced for several years after that, both while I was a lawyer and after I started graduate school, and I've never been in such good shape in my life. Ballet reshaped my body, made me stand and move differently. You can see it if you look at the pictures of me in my Resolutions post. If you look at the first picture, you'll see that I have ballet hands.

I have not taken dance classes for a while. It's difficult to, living here in Lexington. Commuting, teaching, and writing the dissertation take all my time. There's no time left over for dance. But I try to stay in shape by exercising the way a dancer would (you know, pilades, yoga, that sort of thing).

You're wondering what all this has to do with writing, and here it is: I have to do it every day.

I realized this particularly over the last semester, which was one of the most difficult periods of my life. Among other things, I stopped trying to stay in shape. When you've been exercising as long as I have, you don't immediately turn into mush. It takes a while. But I haven't been feeling well. So recently, a couple of weeks ago, I decided to start exercising again, specifically so that, once my dissertation is over, I can go back to taking dance classes. I miss dance, the discipline of it, feeling as though I'm pushing myself to my physical limit.

But again, I have to do it every day. Oh, I suppose I don't have to. But when I don't, even for a day, I feel the weakness in my core, or my shoulders. I feel that I'm not as strong or flexible as I was the day before. When I do it every day, I feel tight, together, as though I can move effectively and efficiently. Flexibility is particularly important. You lose that overnight. Every morning I wake and start to stretch, start to gain flexibility again. And if you do that every day, it's easier the next day, and the next.

(Last night was particularly bad. I haven't had a nightmare for a while, several weeks, but I had one again last night. At first I couldn't get to sleep at all. I lay awake for what felt like hours. But when I finally did get to sleep, I dreamed that my lover was being pursued by the police. He had run into the forest, up into the hills. Then finally they caught up with him and shot him. I was not there, I only heard about it. And then I dreamed the terrible feeling of having lost someone you love, the permanent absence of it. The blankness of knowing that person was gone and would never come again, not on this earth. Mike Allen once wrote that he enjoyed his nightmares and would turn them into stories. Not me. My nightmares are horrible. And – this was my point – I woke stiff all over, barely able to turn my neck.)

I think writing is like that. The brain is a muscle that needs to be exercised every day, and whichever part of it writes, that needs to be exercised in particular.

What did I write today? I wrote part of the first chapter of my dissertation. Well, really I revised it, because it had been written some time ago, but I'm trying to revise both the first and second chapters to make my argument clear. And then I wrote this blog post.

I think both of those count as writing, and later today I will need to work on my Folkroots column, which will count as writing too.

Writing every day, whatever I'm writing, makes me stronger and more flexible as a writer. If I didn't write for one day, I think I would feel it. I think parts of my brain would feel – well, mushy.

I will end with two photographs. This is a picture of me exercising my writing muscles:

And this is a book I saw in the YA section of Barnes and Noble. I include it for your amusement!