Theodora Goss's Blog, page 71

January 20, 2011

Writer Girl

When Writer Girl gets up in the morning, she brushes her teeth and takes a shower. Then she gets dressed and puts on makeup (not too much, not like some other superheroes – she wants people to take her seriously). Finally, she brushes her hair. And she's ready to go for the day.

You probably know what Writer Girl looks like. I'm sure you've seen her, at book signings or, you know, just generally fighting crime. The black spandex, sort of like a black turtleneck with leggings. (Did you expect Writer Girl to fight crime in something that looks like a swimsuit?) The black boots. The black utility belt, slung low on her hips, holding her tools: pens that are mightier than swords, erasers that really erase. Vials of poisonous ink that she throws like hand grenades. The glasses with thick black frames that she wears when she wants super insight. And the hair, pulled sensibly back, but flame red.

Writer Girl is really professor Sylvia Sutherland. Sylvia was ekeing out a miserable existence as an adjunct professor at Metropolis Community College, teaching composition courses for a couple of thousand dollars each and living mainly on canned soup, when she came into contact with a book that changed her life. It was hidden behind a copy of The Complete Poems of Edna St. Vincent Millay, and when she pulled it out, a green light shone on her, giving her the superpowers we're all familiar with. She does not know where the book came from, but she's hidden it in a safe in her apartment. She's still trying to find a way to decipher the alien writing that has had such a profound effect on her life.

First, she has a writing workshop to teach. She looks so sensible in jeans and a black turtleneck, with her hair pulled back. Her students adore her – who else at Wayne University has a perfect five on RateMyProfessors.com? But when class is over, she notices a message on her communicator. It's the police commissioner, who has a direct line to Writer Girl. The Editor is back, and he's wreaking havoc at the headquarters of The Daily Planet. Writer Girl slips into the bathroom. When she comes out, she's ready to fight crime, to – if you'll excuse the pun – write wrongs. Writer Girl knows that's a terrible pun, but what can you do? Crime fighters have to put up with clichés, you know?

I'm not going to write about her fight with The Editor in the newsroom. Who knows how he escaped from Arkham Asylum in nearby Gotham City. The important thing is that when Writer Girl gets done with him, he's going back there.

"Don't worry, Commissioner," she says. "He won't be changing commas for a while, where he's going."

The commissioner shakes her hand vigorously, and newsboy Jimmy Smithers sighs. He's got a poster of Writer Girl on the door of his closet. "Writer Girl! Over here!" yells Newt Newman, the photographer, and Writer Girl turns with a flip of her hair. The next day, there will be photographs of her all over the newspaper.

She's going to be late for a faculty meeting, so Writer Girl crosses the city by cab, riding on top of whichever one seems to be going her way. When people see her, they say things like, "Hey, look, it's Writer Girl! Ma, get a picture so we can show the folks back home!"

Writer Girl's most dangerous weapon is WiteOut. She keeps it in a pen on her belt. Today, she used it on The Editor. It wasn't pretty. Suddenly, he started babbling, not making sense. It was as though all the words in his head had been erased. Who knows how long he's going to be like that. WiteOut takes a long time to wear off.

Writer Girl makes her faculty meeting. Imagine if the other faculty members knew she was Writer Girl! But she keeps her identity carefully hidden. The writing program at Wayne University is very prestigious. Writer Girl has published three books of poetry, and she's a regular commentator on NPR. Still, there are parts of her life that need work. Like, she hasn't dated for a while. Who's she going to go out with? Batman? The Green Lantern? Superheroes are crazy, she says. But who else is going to understand her? So she goes home, foiling a heist at the Metropolis Library along the way, and sits down to watch Masterpiece Theater. Sometimes she wishes she lived in a Jane Austen movie. But don't we all?

Afterward, she posts on her blog. What, you think superheroes don't blog? Tonight she's blogging about a book she just read that she thought was really good. "Check out The Lighthouse, guys," she says. "You're going to like Virginia Woolf, I promise. And don't worry, The Editor's back in the asylum. Metropolis is safe for one more day! Signing off, Writer Girl."

She goes to bed with her large black cat, Shakespeare, curled beside her. Better get plenty of sleep, Writer Girl. You never know who's going to break out of the asylum tomorrow!

January 19, 2011

Two Responses

I recently noticed that two people had responded to blog posts of mine on their own blogs. I love it when that happens! The first was Hecate, who responded to my post "Courage" with her own post, "Who is Choosing to Lost the Fight?" In that post, she quoted from T. Thorn Coyle:

"And, where's the struggle? Is it a struggle of not believing in yourself? Is it a struggle of feeling like you don't have the resources you need? Is it a struggle of of lack of time, lack of energy? Is it a struggle of lack of support around you? Or lack of support from your daily practice? Is it the fear of success? The fear of failure? Where's that struggle?

"My trainer, Carrie Rockland, with whom I do a trade that's very fruitful for both of us – we end up teaching each other, which I greatly appreciate . That's one of the ways I keep fire in my life is to seek out teaching from those who have skills or experiences that I don't have – but Carrie is coming up on a big competition in which she is having to fight someone that she fought many years ago in order to go up a level in the belt system in her martial art. And in talking about this, she wrote something that was so clear that I want to share it with you. Carrie wrote, 'More often than not, the truth is I am the one choosing to lose the fight.' I want us all to take that phrase in right now. 'More often than not, the truth is I am the one choosing to lose the fight.'

"We talk ourselves out of it before we even step on the mat, half the time. We talk ourselves out of it before we even gather the resources needed to see a project through. We talk ourselves out of it before we make that initial step or have that first conversation. We talk ourselves out of it before we even let ourselves brainstorm and dream."

I think that's such an important observation. And I think it's sometimes true of me too, that when I lose, I'm choosing to do so. Sometimes it's because I know in my heart that I'm not ready for that particular fight. If I won it, I wouldn't be ready for the consequences of victory. Sometimes it's just because I'm afraid that I'll lose, and so I put in a half-hearted effort. Because if I didn't really try that hard, it doesn't matter as much that I lost. But most of the time, I'm in whole-heartedly. And those are the times that if I win, I know I deserved to, and if I lose, I'm still proud of myself for having made the attempt.

If you want to win at things in general, or to succeed at things since winning is a strange word to use for most of the things we want to do, you have to be willing to lose as well. I think it's when you're not afraid of losing that you can put your whole heart into the fight in the first place.

The second response was by Duncan Long, to my post "On Beauty." Duncan's post is called "The Beautiful Face." About my post, he writes,

"This reminded me of some very different experiments using software to create 'beauty' by combining facial characteristics from a number of photos. The result was an 'average' of the various faces. And experimenting with such composite photos, researchers find that the more averaging is done, the more 'beautiful' the results are for most people looking at the photos.

"This suggests (to me at least) that most of us have a hardwired 'picture' or icon in our minds that we compare to any given real face. The closer the face to that hardwired icon, the more beautiful is our perception of it.

"This is also how the old trick of taking pictures of women through gauze or lens smeared with Vasoline works; their features become less pronounced – averaged – and they appear more attractive. Likewise digital artists now arm themselves with plugins that add a little light scatter to photos, blurring things in a special way to create a 'beauty shot.'"

While I think that's generally true, that we do tend to have a hardwired picture in our brains – or perhaps a hardwired series of mathematical relationships – one thing strikes me about Duncan's post and the research he cites.

The actual averaged faces I've seen have always struck me as somewhat bland. They are attractive rather than what I would call beautiful. In terms of the theory I set forth in my post, they have too much unity, not quite enough variety. They are not Julia Roberts, whose face has the general symmetry of the composite face but also something more, something unusual about it. I think it's what Edgar Allan Poe called a "strangeness in the proportion" in "Ligeia."

Although I do notice, as Duncan pointed out, that when I use a little light scatter on my photos, they generally look better.

I'm going to end by including something I think is beautiful: Madame X, by John Singer Sargent.

Notice the interplay of unity and variety. And notice the Hogarthian serpentine lines. Plus, I think she has a great nose!

January 18, 2011

Two Artists

You know I like to point out artists that I think are doing interesting work. Well today, I have two of them for you.

I can't post their work here, of course, because it's their work. But I hope you'll follow these links, although readers are often reluctant to follow links. I promise they will lead you to magical places.

The first is for an artist who identifies himself as Ryan A., although I think his name is Ryan Andrews. Under "About," Ryan just writes, "I've got a foot in California and Japan." His work really does seem to be a fusion of two artistic traditions, and it's quite beautiful. Here's what I want you to look at: "Nothing is Forgotten." This is part 1, but there are links to parts 2 through 7 at the bottom. You'll want to follow them; once you start looking, you won't want to stop. And it won't take you long.

"Nothing is Forgotten" is basically a short story in illustrations. It's about a boy who finds a magical creature in the forest close to his house. I won't tell you anything about it – you need to discover the story for yourself – but it reminds me just the tiniest bit of My Neighbor Totoro if it were drawn by Edward Gorey. I hope Ryan doesn't find that description insulting: his own drawing is so pure, so elegant (in the sense of the blog post I wrote on elegance a while back), that it pulls me right into the story, makes me feel the magic of it. And I love stories like that. I promise that you'll love it too.

The second artist is Lori Nix. Go to her website and click on the button "The City." What you'll see are dioramas of rooms in various states of decay. They're like wonderfully intricate dollhouses, but post-apocalypse. As though the dolls had blown up their world, and only these rooms are left, falling into ruin. I think this one, "The Library," is my favorite.

I think Walter Pater was fundamentally right, in his conclusion to The Renaissance, when he talked about the value that art adds to our lives, the way in which it allows us to live more deeply and broadly. For him, art added the highest value, and I'm not sure about that, although I do know that when I'm unhappy I go to the museum. It's as though in the museum, I can lose myself. I become an observer of wonderful things, and I get to set my self, which I spend the rest of my time carrying around with me, aside for a while. It offers an opportunity for self-forgetting or self-transcendence, I'm not sure which.

And then I get to go to the new American Wing:

And eat a banana split:

The fanciest banana split in the world. As I did yesterday.

But seriously, do please click on the links and go see Ryan A. and Lori Nix. If you're here looking at my blog, I know they're exactly the sorts of artists you will like.

January 17, 2011

On Beauty

A few days ago, I had a long conversation with a friend about beauty. After that conversation, I realized that I have two incompatible views of beauty. And I don't know how to reconcile them.

The first view has to do with beauty in nature and art. It comes from two places. I took a class on eighteenth century aesthetic theory in which we talked about various definitions of the beautiful, and the one I found most convincing was a rather old one, and a fairly staid one actually. It was that beauty consists of variety in unity. That is, a variety of things (lines, shapes, colors) that nevertheless comes together as a unified whole. And the greatest beauty is the maximum amount of variety, still unified. I have a feeling that it comes from William Hogarth's Analysis of Beauty, but I'm not sure; I'd have to read it again. Perhaps it's my distillation of Hogarth and his "line of beauty" or serpentine line (the s-shaped double curve that he thought was the most beautiful shape).

And then I heard, on a television show, about a physicist named Richard Taylor who had analyzed Jackson Pollock's paintings and found that they were fractals. That is, there was self-similarity in them: the same mathematical relationships exist in the painting as a whole and in parts of the painting. You can read an article on Pollock's fractal patterns here: "Pollock's Fractals." A fractal demonstrates the same principle I found in Hogarth: variety within unity. If you look at fractal patterns like the leaves of a tree, they have a fundamental unity, but they also have an almost infinite variety. And we consider them beautiful.

If you read the article I linked to, you'll find that Taylor conducted a series of experiments to determine which sorts of patterns human beings find most pleasing. He determined that what we find most pleasing are fractals, but more than that, fractals with a specific relationship: the ones closest to the fractal dimensions we see in nature.

I'm going to include three quotations from the article:

"Studies have found that people prefer patterns that are neither too regular, like the test bars on a television channel, nor too random, like a snowy screen. They prefer the subtle variations on a recurring theme in, say, a Beethoven concerto, to the monotony of repeated scales or the cacophony of someone pounding on a keyboard."

"Artists, architects, writers, and musicians may instinctively appeal to their audiences by mimicking the fractal patterns found in nature."

"In a famous 1950 documentary by Hans Namuth, one can see Pollock circling his canvases on the floor, dripping and flinging paint in motions that seem both haphazard and perfectly controlled. He wasn't merely imitating nature, he was adopting its mechanism: chaos dynamics."

So that's my view of beauty in nature and art. I believe that beauty in the natural world and in an artistic work comes from variety within unity, and that a particular relationship between the two triggers something in us, a sense of recognition that makes us say, "Yes. That's it." I think my best stories have that, a particular relationship between variety and unity. It's something I was not aware of when I started writing, but that I'm more aware of now. I want my stories to be like Pollock's paintings: if you look at them closely, they should still be intricate. There should still be more to see, within a unified whole. And I believe we see beauty in that particular relationship because we're wired to do so. We've been wired that way by millions of years of evolution within a fractal environment. We think art is beautiful when it most closely resembles nature, not by representing it but by operating according to the same mathematical principles.

But that view is completely at odds with my view of personal beauty. Do you remember Merlin, the television miniseries? It features Helena Bonham Carter as Morgan le Fay, who is initially disfigured but who is made beautiful by magic. At the end, after she has been defeated, she becomes disfigured again. Merlin tells her that her beauty was only an illusion. She looks up at him and says, "Beauty is always only an illusion." That's what I believe about personal beauty, that it is always constructed. Think of the different looks of Helena Bonham Carter herself, all the different ways she can appear. Sometimes beautiful, sometimes plain, sometimes grotesque.

I find it fascinating to look at the women who have to be beautiful because it's a professional requirement: film actresses. When they start out, they are often not particularly beautiful. Think of Scarlet Johansson in Ghost World, and think of her now. She has been Hollywoodized. There is something Hollywood does to them. They lost some of their individuality. But they gain a sort of glow. They no longer look ordinary. They become luminescent. And then, when a film role requires, they can become quite ordinary again. Think of Kate Winslet as Iris Murdoch in Iris. And then, for appearing ordinary (which the film industry evidently sees as a significant feat), they often win Oscars.

In the course of this conversation, my friend commented on some pictures of me he had seen online, and I said, "You should see me with green goop on my face." And then I said, "I should post a picture of that." And then, "No, I shouldn't. It's going to be out there forever." And that was a failure of nerve.

So here is my argument that beauty is constructed. The green goop picture:

A picture with no green goop, posed and photoshopped:

And a drawing that Kendrick made of that picture. Here we circle back to the issue of art.

What bothers me is that I see beauty in nature as mathematical, while I see personal beauty as always constructed, always only an illusion. Perhaps the way to reconcile these two views is as follows: beauty itself is mathematical, a fractal relationship. That applies to trees and faces, as well as to works of art. How we get to that relationship, that variety within unity: in terms of personal beauty as well as art, that is always a construct, an illusion. It is something we create, as Pollock created his paintings.

(Which makes me think, if I just dripped paint on my face . . . Well, perhaps that will be the next photograph!)

January 16, 2011

Three Things

Three very nice things happened in the last few days.

The first thing was that I received the page proofs for "Pug," which is going to be in Asimov's Science Fiction. It was the first time I had absolutely no corrections to make to page proofs. But the very nice thing was just seeing the story as it's going to appear in the magazine. As I read through it again, I realized that I liked it – there was nothing I cringed at, nothing I thought I could have done better. There was even a paragraph that made me cry. I write all this knowing that readers may well not understand the story, may look at me and go, "What?" It's a sort of literary gamble.

And guess what? I'm not going to explain it to you. You're just going to have to read it and figure it out for yourself!

The second nice thing was that Jo Walton mentioned me in her list of recommended writers on the Tor.com blog. Here she is, working on the letter G: "OK, where do I start with that? G." Jo wrote, "Theodora Goss is one of the best short story writers and poets working today in fantasy," which I mention only because that's the sort of thing that keeps you going, you know? The sort of thing that makes you sit at your desk and write, even on the days when all you want to do is crawl under the fuzzy blanket and read Murder in Mesopotamia. That someone like Jo Walton not only mentioned me, but thought my writing good enough to praise.

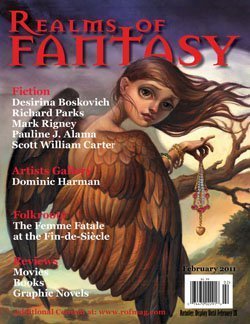

The third nice thing was that I saw not only the cover for the February issue of Realms of Fantasy, but also how my Folkroots column is going to look online, on the Realms of Fantasy website. This particular column is going to be online because the February issue will be the first one under the new publishers. Future columns won't be. But I think you're going to enjoy this one, which is also my first for the magazine. I can't show you the column, although I'll link to it when it comes out in a few days. But here is the cover:

Doesn't it look great? And look: the Folkroots column is prominently mentioned. I've been told that under the previous editors (Terri Windling, Ari Berk, and Kristen McDermott), it was a part of the magazine that readers loved most. I know that when I read my copy of Realms of Fantasy, I always went to Folkroots first, and then to the art column and reviews, before starting on the stories. I really, really hope that I can make it as interesting and engaging as they did.

(And just so you know, I'm thinking of writing my next column, for the June issue, on fairies. That sounds like fun, don't you think?)

January 15, 2011

What Llosa Said

I'm going to quote from Mario Vargas Llosa's Nobel Prize lecture, because I think some of the things he said might interest you. They certainly interest me. If, afterward, you want to read the entire lecture, you can do so here: "In Praise of Reading and Fiction." Llosa said,

"I learned to read at the age of five, in Brother Justiniano's class at the De la Salle Academy in Cochabamba, Bolivia. It is the most important thing that has ever happened to me. Almost seventy years later I remember clearly how the magic of translating the words in books into images enriched my life, breaking the barriers of time and space and allowing me to travel with Captain Nemo twenty thousand leagues under the sea, fight with d'Artagnan, Athos, Portos, and Aramis against the intrigues threatening the Queen in the days of the secretive Richelieu, or stumble through the sewers of Paris, transformed into Jean Valjean carrying Marius's inert body on my back.

"Reading changed dreams into life and life into dreams and placed the universe of literature within reach of the boy I once was. My mother told me the first things I wrote were continuations of the stories I read because it made me sad when they concluded or because I wanted to change their endings. And perhaps this is what I have spent my life doing without realizing it: prolonging in time, as I grew, matured, and aged, the stories that filled my childhood with exaltation and adventures."

Today I spent an hour or so going through the galleys for my story "Pug." In case you don't know, galleys are the final glimpse I get of a story before it's published. I get the galleys, I make any final corrections, and then the story comes out in a magazine (in this case, Asimov's). This time, for the first time, I didn't need to make any corrections. The story looked perfect. "Pug" is a story about a character from another novel, a minor character that I turned into the main character of my story. In writing it, I think I was doing a little of what Llosa talks about here, prolonging a story I loved, but also entering into a dialog with that writer, saying to her: look, here is my interpretation. I wish I could say to her, tell me what you think. Talk back to me. But of course she can never do that. (Requiescat in pacem, Jane Austen.)

But Llosa's description of what stories did for him, when he was a child – that's what they did for me too.

"Writing stories was not easy. When they were turned into words, projects withered on the paper and ideas and images failed. How to reanimate them? Fortunately, the masters were there, teachers to learn from and examples to follow. Flaubert taught me that talent is unyielding discipline and long patience. Faulkner, that form – writing and structure – elevates or impoverishes subjects. Martorell, Cervantes, Dickens, Balzac, Tolstoy, Conrad, Thomas Mann, that scope and ambition are as important in a novel as stylistic dexterity and narrative strategy. Sartre, that words are acts, that a novel, a play, or an essay, engaged with the present moment and better options, can change the course of history. Camus and Orwell, that a literature stripped of morality is inhuman, and Malraux that heroism and the epic are as possible in the present as is the time of the Argonauts, the Odyssey, and the Iliad.

"If in this address I were to summon all the writers to whom I owe a few things or a great deal, their shadows would plunge us into darkness. They are innumerable. In addition to revealing the secrets of the storytelling craft, they obliged me to explore the bottomless depths of humanity, admire its heroic deeds, and feel horror at its savagery. They were my most obliging friends, the ones who vitalized my calling and in whose books I discovered that there is hope even in the worst of circumstances, that living is worth the effort if only because without life we could not read or imagine stories."

You understand this, right? This is how we learn as writers. We read other writers and we learn from them. We are uniquely privileged in our ability to do that, to learn from our masters. I can study with Austen, Woolf, Tolkien. They teach me about craft and style, but as Llosa said, they also teach me about humanity, and about myself, because ultimately whatever I write about humanity is also a statement about myself. I cannot write about a killer without finding the impulse to kill in myself. I cannot write about a martyr without finding what, in myself, would send me to my death for a cause.

"At times I wondered whether writing was not a solipsistic luxury in countries like mine, where there were scant readers, so many people who were poor and illiterate, so much injustice, and where culture was a privilege of the few. These doubts, however, never stifled my calling, and I always kept writing even during those periods when earning a living absorbed most of my time. I believe I did the right thing, since if, for literature to flourish, it was first necessary for a society to achieve high culture, freedom, prosperity, and justice, it never would have existed. But thanks to literature, to the consciousness it shapes, the desires and longings it inspires, and our disenchantment with reality when we return from the journey to a beautiful fantasy, civilization is now less cruel than when storytellers began to humanize life with their fables. We would be worse than we are without the good books we have read, more conformist, not as restless, more submissive, and the critical spirit, the engine of progress, would not even exist. Like writing, reading is a protest against the insufficiencies of life. When we look in fiction for what is missing in life, we are saying, with no need to say it or even to know it, that life as it is does not satisfy our thirst for the absolute – the foundation of the human condition – and should be better. We invent fictions in order to live somehow the many lives we would like to lead when we barely have one at our disposal."

Writing is a protest against the insufficiencies of life. We look at life and we see how it fails us, how people are not as we wish they were, society is not as we would like it to be. And so we write about Elizabeth Bennett and Middle Earth, so we can show a lively and inventive mind, a place of unearthly beauty. So we can experience those things, even when things around us seem dull, ugly. Literature makes us discontented with our lots. And great literature makes us change them. It shows us who we can be, how we can think, what we can become.

"Without fictions we would be less aware of the importance of freedom for life to be livable, the hell it turns into when it is trampled underfoot by a tyrant, an ideology, or a religion. Let those who doubt that literature not only submerges us in the dream of beauty and happiness but alerts us to every kind of oppression, ask themselves why all regimes determined to control the behavior of citizens from cradle to grave fear it so much they establish systems of censorship to repress it and keep so wary an eye on independent writers. They do this because they know the risk of allowing the imagination to wander free in books, know how seditious fictions become when the reader compares the freedom that makes them possible and is exercised in them with the obscurantism and fear lying in wait in the real world. Whether they want it or not, know it or not, when they invent stories the writers of tales propagate dissatisfaction, demonstrating that the world is badly made and the life of fantasy richer than the life of our daily routine. This fact, if it takes root in their sensibility and consciousness, makes citizens more difficult to manipulate, less willing to accept the lies of the interrogators and jailers who would like to make them believe that behind bars they lead more secure and better lives."

You may argue that great literature does this, but some literature is merely escapist, and escapism supports the status quo. I would argue that all literature is escapist, and that escape, for even a little while, allows us to look back at where we were, and if it is a jail, say: "I am not a prisoner." Because if you were not a prisoner for an hour, while you read, perhaps you are not a prisoner at all, or ought not to be a prisoner. Perhaps you ought to be as free as you were in the pages of a book.

"The paradise of childhood is not a literary myth for me but a reality I lived and enjoyed in the large family house with three courtyards in Cochabamba, where with my cousins and school friends we could reproduce the stories of Tarzan and Salgari, and in the prefecture of Piura, where bats nested in the lofts, silent shadows that filled the starry nights of that hot land with mystery. During those years, writing was playing a game my family celebrated, something charming that earned applause for me, the grandson, the nephew, the son without a papa because my father had died and gone to heaven. He was a tall, good-looking man in a navy uniform whose photo adorned my night table, which I prayed to and then kissed before going to sleep. One Piuran morning – I do not think I have recovered from it yet – my mother revealed that the gentleman was, in fact, alive. And on that very day we were going to live with him in Lima. I was eleven years old, and from that moment everything changed. I lost my innocence and discovered loneliness, authority, adult life, and fear. My salvation was reading, reading good books, taking refuge in those worlds where life was glorious, intense, one adventure after another, where I could feel free and be happy again. And it was writing, in secret, like someone giving himself up to an unspeakable vice, a forbidden passion. Literature stopped being a game. It became a way of resisting adversity, protesting, rebelling, escaping the intolerable, my reason for living. From then until now, in every circumstance when I have felt disheartened or beaten down, on the edge of despair, giving myself body and soul to my work as a storyteller has been the light at the end of the tunnel, the plank that carries the shipwrecked man to shore."

I was talking to a friend recently and we agreed that literature was like this for us. When we feel disheartened, beaten down, and on the edge of despair, we start writing. That saves us. I think because when we write, we create alternatives on the page, and that allows us to create alternatives for ourselves as well. We write about living on Mars for a couple of hours, and then we can think about how we might live, in a different way, here on Earth.

"Literature is a false representation of life that nevertheless helps us to understand life better, to orient ourselves in the labyrinth where we are born, pass by, and die. It compensates for the reverses and frustrations real life inflicts on us, and because of it we can decipher, at least partially, the hieroglyphic that existence tends to be for the great majority of human beings, principally those of us who generate more doubts than certainties and confess our perplexity before subjects like transcendence, individual and collective destiny, the soul, the sense or senselessness of history, the to and fro of rational knowledge."

I think that's an excellent way to end, although Llosa does not end that way. To see how he ends (magnificently), read his speech. But I want to end here because I feel as though I'm part of that contingent: generating more doubts than certainties and confessing my perplexity before all sorts of things: who I am, where I am going, what my purpose is in the large, large world (so much larger than my understanding of it). It's because of those doubts and perplexity that I write stories, that I attempt to find or create meaning, that I attempt to find or create myself through words.

As I am doing here.

January 14, 2011

Courage

I was thinking about the quality of courage today.

I suppose I was thinking about it because I'd seen some things recently that were not at all courageous. That were cowardly. I'm not thinking in terms of physical courage or cowardice. I'm thinking about how we all deal with our lives. The problem is that courage is a sort of muscle. If you don't use it, the muscle becomes weaker, eventually atrophies. And then you can't use it, you can't lift what you need to, or even bend where you need to because it has become stiffer, less flexible.

Courage needs to be exercised.

I remember when I first started going to conventions. I was nervous, partly because everyone else had been going to conventions for a while, knew each other, had written books. I felt so new in that world. And I was particularly nervous being on panels. So I volunteered to moderate them. Moderating a panel is not an easy task. You have to be more aware, pay more attention than if you're simply on the panel. And I was moderating people who were much, much better known than I am. Samuel R. Delaney, John Clute, Barry Malzberg. And not all of them were particularly easy to moderate! But moderating panels gave me a reason for being on the panel: I wasn't just the author that no one knew. I was the moderator.

I noticed, when I was in college, that often the classes that were supposed to be harder ended up being easier than the supposedly easy classes. Often, it seems to me, when you do something that requires more courage, it ends up being easier than the thing that requires less. Like moderating rather than simply being on a panel.

Each time you put yourself out there in some way, each time you do something that takes courage, you're exercising that muscle so the next thing becomes easier. I've spoken so often in public now that it's no longer frightening, no longer something I need to be anxious about. I just do it.

On the other hand, if you routinely avoid what you fear, you start to believe that you really can't do whatever it is. And you shrink from other things as well, thinking you can't do them either.

You know where this is going, right? It takes an enormous amount of courage to be a writer. Perhaps not as much as to be an arctic explorer or a lion tamer. But being a writer means working in solitude, accepting rejection, and attempting to publicize your work, all of which are things that frighten people. Publicizing your work in particular is not easy. Many writers can sit at their desks, typing stories. They can open and file the rejection slips, send out the next story. But going to a convention, being on panels, doing readings – those can be more difficult for writers. We tend to be introverts anyway.

I think those things are absolutely necessary. You need to get out there, present your work to the public. Among other things, it's a gesture of faith in your work. If you don't believe in its importance, its relevance, its beauty, why should anyone else?

And then there's the whole other level of having an online presence, of using a website and various social media effectively. So people know who you are, so they recognize your name. That takes a particular kind of courage as well, because again you're putting yourself in front of an audience, and this time the audience is potentially world-wide. Twenty to fifty people might come to a reading I do, but at least two hundred people come to this blog every day. (And thank you for coming, by the way!)

All of this needs courage. And how, you may ask, do you build courage, if it really is a muscle, as I claim?

1. Find something you're afraid of.

2. Do it.

3. Repeat steps 1 and 2, as many times as necessary.

That was the thought I had today, because what I saw instead was cowardice, which led to weakness, which led to more cowardice and weakness in a feedback loop. And none of us wants to be there, dying a thousand times before our death. Among other things, it's no way to be a writer.

January 13, 2011

The Forger

Yesterday, I read this story in the New York Times: "Elusive Forger, Giving but Never Stealing."

It's about an art forger named Mark Landis, who paints pictures in various styles and then donates them to museums.

He's a con artist of sorts, except that the con is to give the museum something rather than to take something away. He assumes various identities: a priest, a philanthropist. He goes to the museum, offers to donate a picture he has painted. He often imitates painters that are less well known, but has painted a Daumier, a Watteau, a Picasso. (How would you forge a Picasso? Surely all the Picassos are known. Would he really dare approach a museum with a newly discovered Picasso? Imagine the publicity!)

What interested me about this article was the man himself. Who is Landis? What motivates him to do what he does? I would imagine that most forgers are motivated by money, but that doesn't seem to be his motivation at all. He's not selling the paintings. Does he find satisfaction in the con itself? Surely there are better and easier cons that would give him as much satisfaction. No, he sits in a studio painting, creating pictures good enough to fool a museum curator. And then he attempts to give them to the museums. Is it a pleasure having imitated an artist so well that he can fool people into thinking the painting is an original? That must be part of it. A sort of pleasure in the craft, and in having put one over on both the experts and the museum visitors.

But I really don't know. If I were writing about a man like Landis, I would have to create a story for him, one that provides him with motivations for doing what he does. They would be motivations I don't have myself, because I'm a writer, not a forger. I'm the real thing. I can't imagine trying to pass my work off as someone else's. But in creating him as a character, I would have to understand his motivations – to see the world as he does.

When I read a story like this one, I'm always fascinated. By a man who forges paintings and donates them to museums, by a writing prodigy who disappears before her thirtieth birthday, even by a woman who writes letters to imprisoned serial killers. (All of these stories are true, and the last one is particularly disturbing and dark, but because I am a writer, they all catch my interest. I think, who was this person? What motivations did he or she have? And how would I write a character like this?)

Writers aren't always interested in people. But I think that's the sort of writer I am. And I'm particularly interested in people who are odd or eccentric. I suppose that's because I feel a certain affinity. After all, what I do is odd and eccentric as well. I put words on paper and they create worlds, and characters to inhabit those worlds. I make things up (not exactly for a living, but for at least five cents a word).

It's not fair to Mark Landis, what I'm doing here – turning him into an object of speculation, and ultimately perhaps into a literary character. But what we do as writers isn't fair, is it? We take our experiences, the people we've known or people we've simply glimpsed on a bus, and we turn them all into material for our writing. Perhaps in a way the art of the forger is kinder, more generous. He only imitates art. We capture life.

January 12, 2011

Believe

"This may sound too simple, but is great in consequence. Until one is committed, there is hesitancy, the chance to draw back, always ineffectiveness. Concerning all acts of initiative (and creation), there is one elementary truth the ignorance of which kills countless ideas and splendid plans: that the moment one definitely commits oneself, then fate moves too. A whole stream of events issues from the decision, raising in one's favor all manner of unforeseen incidents, meetings and material assistance, which no man could have dreamt would have come his way."

– William Hutchinson Murray

I believe this. I believe that when one definitely commits to an enterprise, fate moves too, and all sorts of unforeseen things begin to happen.

I've seen it happen in my own life. It took me a long time to definitely commit to a writing career. I hesitated, not because I had any hesitation about writing – I had wanted to write since I was twelve years old. But because I had all sorts of doubts about myself, about whether I would be good enough. There were times when I definitely thought I would not be – I mean, I thought I would be good enough for publication, and even to have a career, but that wasn't good enough for me, if you see what I mean. Because I wanted to be great, to be one of the writers that people remember. Virginia Woolf with fairies. It took me a long time to believe I had that potential. (Not that I'm anywhere close to realizing it, of course. But I had to believe the potential was there.) Partly, it was other people telling me I had it that convinced me. (So thank you, Dan Simmons and Jim Kelly and everyone else who told me I could do it.) And partly I had to just put in the work, start to feel the power of it flowing through my hands. I can feel that now – I can feel the skill, the ability to put words together the way I want to, so they express what I want to. Like a dancer aware of her own body, aware that it can do what she needs it to so she can produce certain shapes, create certain patterns. Express what is in her.

At some point, I did commit myself. And around that point, things started to happen. I was offered opportunities I would not have expected, to teach and edit, to write for certain publications. I was in the right places at the right times, with the right qualifications. And fate moved for me.

So I would say, if you want something in your life, you need to do the following:

1. Commit to it, and announce your commitment to it. But the commitment has to be genuine. There can be no hesitancy. And show your commitment by working on it, whatever it is. If you can work on it every day, all the better.

2. But realize that commitment is magical. It's like a spell. Don't talk about how much you would like to go to Nepal (to use an example that came up recently in a conversation with a friend) unless you really want to go to Nepal, and intend to someday. Because fate will get confused and start wondering about your intentions. Do you really want to go to Nepal? Or do you want to go to England to research your first novel? Focus on what you actually intend, what you have committed to, and articulate that.

3. Believe that once you've worked on it long enough, fate will move for you. Fate will help you, it will become your friend, because fate is like that. It favors the brave, the committed. On my desk, I keep only necessities: a desk lamp, my computer, papers I need for various projects, a mesh jar filled with pens. But I also have one thing that is not absolutely necessary. This:

It's a rock with the word BELIEVE carved into it. I bought it years ago, in some sort of gift shop. Sometimes I find myself playing with it, and I realize that the impulse is almost unconscious. It's when I most need to BELIEVE that I reach for it. It's a small spell, of sorts.

I know there are people who will say, do not trust to fate. Put your trust in hard work. But if you believe that hard work alone will get you where you need to go in a career like writing, well – that in itself is wishful thinking. You're going to need luck too, except I call luck fate, because it's not random. It favors the prepared. In other words, the committed.

January 11, 2011

Vampires!

Lately, I've been thinking about vampires.

Last year, I wrote a vampire story for the Sycamore Hill writing workshop. While I was writing it, I was thinking specifically about how one could write a vampire story now, after all the vampire stories we've been inundated with. In my story, vampirism was a purely medical condition. In a way, the story was really about a laboratory, the research that went on in it, the problems that could occur. It was inspired by what I know about laboratory work from all the scientists in my family.

I didn't do anything with that story. It's still sitting on my computer, the only story I've written that I haven't sold. It's long, and I haven't had time to work on it so that I can sent it out anywhere. It's called "Life, With Vampires," but that needs to change. Talk about an uninspired title!

Then, I talked to Nathan Ballingrud about a vampire story he wrote recently, called "Sunbleached." It's going to be in Teeth, a YA vampire anthology edited by Ellen Datlow. Nathan sent me his story, which is of course very good indeed, and definitely a different take on the vampire.

And then I wrote my Folkroots column on vampires. I sent it off to Doug Cohen, the editor of Realms of Fantasy, several days ago. I did quite a lot of research for it, mostly on vampire folklore. I also talked a lot about the literary vampire, since the vampire as we know it really is a creature of literature. I included Lord Ruthven, Sir Frances Varney, Carmilla, Count Dracula, and of course mentioned more modern vampires as well.

The question I kept asking myself, as I was writing it, was whether there is anything more we can do with vampires. Particularly after Twilight, which I have to admit rather destroyed vampires for me. I read the book because I felt as though I had to, and I found it compulsively readable. But I've never encountered such boring vampires in my life. After Lord Ruthven, Carmilla, Dracula, Lestat, Angel and Spike – we get Edward? That's sad.

I don't know if we can make the vampire interesting again. Oh, granted, there's still a lot of interest in vampires. They're all over YA fiction. But can we make the vampire interesting again as a literary creation?

The answer is that I don't know. I do have a vampire story I've always wanted to tell, which is very much the sort of story I do tell – a story on the margin of another story, which is something I realize I do frequently. I've always wanted to retell Dracula from Mina's perspective. But to tell the story of her life, and to show that the story Bram Stoker told is only part of a larger story. In other words, I've always wanted to write The Secret Diary of Mina Harker. That would be a fun project, I think.

If I were to write a vampire story, I would strip away much of what has been added to the vampire: the fear of garlic, daylight, religious symbols. I would take the vampire back to where it was in "Carmilla," as a sort of top predator. That's what Carmilla really is, a predator who both seduces and feeds off her prey. She is a biological creature with a life cycle that is different from ours.

In face, Carmilla tells us that herself. I didn't quote this in my Folkroots column, but I've always found it a fascinating passage. Carmilla says to Laura,

"Girls are caterpillars while they live in the world, to be finally butterflies when the summer comes; but in the meantime there are grubs and larvae, don't you see – each with their peculiar propensities, necessities, and structure. So says Monsieur Buffon, in his big book, in the next room."

Monsieur Buffon is Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, who wrote Histoire Naturelle, Générale et Particulière, which was essentially the biology textbook of the eighteenth century. (This is where my fiction and my scholarship touch, because I mention Buffon in my dissertation, which actually has a section on "Carmilla.") What Carmilla is claiming here is that vampires are a natural species, as natural as any included in Buffon's book. She is also claiming that vampires have a natural life-cycle, like the life-cycle of the butterfly, in which a girl is the caterpillar who is transformed into the butterfly-vampire. Recall that the butterfly is the reproductive form of the caterpillar. The purpose of the vampire girl, then, is to reproduce, to create new vampire girls. And, of course, to be beautiful.

Come to think of it, that actually is a novel idea for a vampire story. Maybe I'll write that one as well.

All I need is time. Which I would have a lot more of, if I were a vampire.

Because of our conversation, Nathan is also blogging about vampires today. Go look at his post, "Vampires in the Sun." About "Sunbleached," Nathan writes,

"When I was asked to write a story about vampires for Teeth I saw it as a chance to reclaim – for myself if for no one else; for that terrified, deliriously excited little boy I used to be – the terror of a vampire. My vampire would burn in the sun. My vampire ached to open your veins. My vampire would beautiful, but not in the way we had come to expect them to be. My vampire would be beautiful the way a great white shark is beautiful.

"I wanted to acknowledge, in a small way, what the vampire has become. I thought that if a vampire would be forced to live in our world it would have to rely on seduction as a means to snare prey. But there are so many modes of seduction beyond the sexual. I also wanted to show how psychologically dangerous they were. That no matter how they looked or what their circumstance, they were predators to the end. Finally, my vampire had to be scary. A thing that haunts the darkness and breathes fear."

That sounds a bit like what I was saying above: the vampire as top predator. Sharks, wolves, eagles. They're beautiful, deadly, and terrifying when you're the prey. That's one way, and a very good way, to go forward with vampires. If indeed we want to go forward with vampires. But they never seem to go away, do they? The pesky creatures.