Theodora Goss's Blog, page 2

June 1, 2025

Making a Home in London Again

One of the greatest pleasures in the world is waking up to the sound of birdsong.

That’s what I wake up to each morning in my London flat. It’s not really my flat, of course. Someone else owns it, and I am only its temporary occupant, courtesy of the letting company that lets it out to short-term tenants and the university that pays for my stay here. This is the fourth flat I’ve had in London. The first was quite far from the central campus — I had to find it in a hurry when I was asked to replace a faculty member who could not come to London after all. It was in the north of London, on a charming street, and would have been perfect if not for the long commute. The second was in Kensington, within walking distance of campus, and quite posh — but several things went wrong with it. When I moved in, the refrigerator was already broken and needed to be replaced, for example. There was also the fact that it was close to a rather noisy pub, where a crowd would gather on Friday and Saturday evenings. The third flat was in a quiet back street several blocks from Sloan Square. It was a basement flat, which is perfect for July in London, where most flats have no air conditioning. I loved it and wanted to return this summer, but the university changed my schedule — I would be teaching in June, not July — and that flat was already reserved by someone coming for the Chelsea Flower Show.

So here I am in flat number four, and given that there are no perfect flats, this may be the best of all. This time it’s between High Street Kensington and Notting Hill Gate, in a row of white buildings from a previous century. It has the most important thing I need in a flat, which is a long table where I can work — because I’m not here to sightsee. I’m here to teach, and my weekends usually consist of commenting on proposals and first drafts, grading final drafts of essays . . . But as I sit here in the living room writing, I can look out the tall front window facing the street, and there is a tree, tall and leafy and green, keeping me company. There is also a bedroom facing the back, and through that smaller window I can see more trees, the ones in which the birds are chattering away — somewhere back there is Kensington Gardens. The flat also contains a bathroom and a narrow kitchen, too small for a regular refrigerator or stove. Instead, I have a sort of half-refrigerator, a cooktop with two convection burners that have convinced me never to get convection burners, and a microwave. I also have a combination washer and dryer that takes about three and a half hours to wash and dry a load of laundry, but it’s my very own washer and dryer, which is more than I have in Boston, where I’m dependent on the building laundry room. To me, it feels luxurious.

Each time I come to London to teach, I stay for at least six weeks, which means I’m really living here — I need to buy groceries, do laundry, commute to work. The experience makes me consider and sometimes reconsider what it takes to live somewhere, to make a home there. Of course this isn’t my home, really. But even for six weeks, I try to make it a home away from home. It has made me realize that for basic happiness, I need much less than I already have in Boston. For example, in Boston I have a closet full of clothes, and here I have only a suitcase worth–but that’s enough for six weeks of teaching and grading and going to museums.

What does it mean to feel at home? I suppose it means that you feel a sense of ease moving around a place. You know where to go for the things you need. For my basic groceries, I go to a small Sainsbury’s a few blocks away. That’s where I buy milk and orange juice and yogurt. For anything more elaborate, there’s the Marks & Spencer on Kensington High Street or a Waitrose near the university campus, where I can pick up groceries on my way home. Along the High Street are a Ryman’s for pens and paper and whiteout as well as a hardware store that also sells housewares of various sorts. Also close to me are a beautiful old church where one can quietly sit and contemplate (because this is England and the churches are open), as well as Kensington and Holland Parks to walk in. So food for the body and food for the soul are both within walking distance. I almost forgot to mention that there is a large Waterstones on the High Street — that’s a bookstore, so food for the mind is within walking distance as well.

And I suppose feeling at home also means that you have enough. It’s amazing how little is enough for six weeks. I planned carefully, so that every item of clothing I packed went with all the others — in shades of black and beige and burnt orange and olive green. I suppose it could be called a capsule wardrobe, but I prefer to think of it as a “suitcase wardrobe.” It was challenging to plan, because one never knows what one will get with London weather. So far we’ve had beautifully sunny days as well as cold, windy ones — and several days of serious rain. Of course I’ve bought a few things since I’ve been here, because one of my personal failings is buying clothes I fall in love with (“How pretty! I can imagine walking through a rose garden in that dress!”), even though I already have enough for all practical and impractical purposes. But I’ve been strict with myself — they need to match the items I already have. When I leave here, they will also need to fit into the suitcase.

But I want to dig a bit deeper into this idea of home — what makes this place feel homey? My basic needs are met, that’s certainly part of it. I can move easily around this space, both inside the apartment and outside in the city. But there is something else — something less tangible. This apartment is filled with light and air, and in the mornings with birdsong. There is a sense of peace. That’s it, I think — home is where you feel peaceful, where your spirit is light. Where you can find ordinary happiness in doing the laundry, cooking dinner, sitting down to finish grading a set of essays. Where there is a silence that is not complete silence, because you can hear the sounds of daily life around you — the sound of a neighbor moving around in the adjoining flat, the wind in the leaves of the tree outside the window, a distant car horn.

I know that I will often be in the middle of bustle and crowds — I will be in airports and tube stations. I will be in the middle of the political turmoil of our times (aren’t we all?). But finding a home, even away from home, is necessary for the soul. I think it’s what we all crave, in the end — that sense of peace and belonging. Of being at home, somewhere in this busy world.

(The image is my front window in Kensington.)

May 4, 2025

Imagining Fairytale Resistance

The title of this post comes from a book that will be published sometime this year: Women of the Fairy Tale Resistance by Jane Harrington. I have not read the book yet, but of course I will when it comes out. The book is subtitled The Forgotten Founding Mothers of the Fairy Tale and the Stories That They Spun, and it focuses on 17th century writers of fairy tales like Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy.

Hopefully I can write about that book once I’ve read it. But what I want to focus on now is the term “fairytale resistance,” which struck me as soon as I heard it. What would a fairytale resistance look like nowadays, rather than in the seventeenth century?

Let’s start with a story. It’s the story of a young woman who walks through the forest to her grandmother’s house, carrying a basket with bread and wine. Along the way, she meets a man who asks her what she is doing. She tells him that she is going to her grandmother’s house at the edge of the village. She doesn’t know (you probably didn’t know) that the man is a werewolf (a bzou in antique French). As soon as she’s out of sight along the path, the man turns into his wolf form and runs through the forest to grandmother’s house. He eats grandmother up and, in man form again, dresses himself in her clothes.

You know, more or less, the story I’m taking about. But this is a slightly different version in which the young woman does not have a red cap — Charles Perrault added the cap later. This young woman gets to grandmother’s house, and when the werewolf dressed as grandma tells her to get into bed with him, she quickly realizes what’s going on. She says she needs to go out to relieve herself. The werewolf says, “All right, as long as you tie a rope to your ankle. I will hold the end of the rope. That way, I can tell if you try to run away.” She ties the rope to her ankle, but when she gets outside, she unties the rope and ties it around the trunk of a plum tree. By the time the werewolf figures out what’s happened, she has run away. He runs after her, and she can see him chasing behind, perhaps catching up. Is he in wolf or man form at this point? The story does not say, but he can run more quickly in wolf form. Either way, I suspect she is frightened of being caught. The girl comes to a river and asks the washerwomen to help her. They raise the sheets they are washing so she can run over them. When the werewolf arrives and tries to run over the sheets as well, they lower their sheets and he drowns.

This story was told, in slightly different forms, in late medieval France, and it’s the story that eventually became our “Little Red Riding Hood.” I’ve put details from slightly different versions together to create a narrative of my own — as a storyteller would have done at that time.

But this is what fairytale resistance looks like. When you realize that you’re unwittingly gotten in bed with werewolves (metaphorically, and I’m thinking about politics here), you need to get smart very quickly. And it’s very useful to find helpers and allies, like the laundresses in this story.

Fairytale resistance is what the peasantry spoke about, sang about. When you read the folk versions of fairy tales, they are filled with clever young women and men. In the folk version, Cinderella gets her dress from a hazel tree she has watered with her tears — a tree she planted on her mother’s grave. She is helped by birds, and when she goes to the ball (or church, in some versions), she is alone and clever. She gets no godmother to council her until, you guessed it, Perrault. He also came up with the impractical glass slippers. Vasilisa, whose Russian tale resembles Cinderella’s, survives the hut of Baba Yaga through her own cleverness and with the help of a doll given to her by her mother. She becomes Tsarina because she can weave linen so fine that the Tsar has never seen its like. The girl in “Frau Holle” is both clever and kind — she helps the laden apple tree and the oven filled with bread, and she serves Frau Holle so well that she is eventually rewarded.

Originally, fairytale resistance was a way for the peasantry to assert their power in a world that was often unfair and unkind. It meant telling stories about clever characters who defeated figures much stronger than themselves, like Jack and the giant, or Hansel and Gretel in the witch’s house. They did it through being smarter, smaller, quicker — and through helping others who would later help them — and usually through being kind. Even Jack, who is a sort of trickster, gave the gold to his mother. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, fairy tales would be taken up by tellers who were no longer peasants, but were generally not those in power either. Female tellers who might have been aristocrats, but had little control over their own lives in the France of Louis XIV. The poor (sometimes very poor) Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. The governess Madame de Beaumont, whose husband had left her destitute. Hans Christian Andersen. The tales changed form, but they remained sites of resistance against those in power. They remained little rebellions in words, little formulas for how you revolt against the ruling classes.

So what were these formulas? Each tale is different, of course. But I think fairytale resistance looks something like this:

You have to be clever. Know what a werewolf looks like. Gather pebbles to scatter behind you, to lead you home again. Figure out how to trick the witch or giant who wants to eat you — being clever can also include being tricky. Even the “simple” third sons in fairy tales are usually smarter than their intellectual brothers.You have to be kind, because we live in a community of washerwomen and apples trees and bread ovens and birds that live in a hazel tree and possible pre-Christian goddesses, and we all need to help each other. Fairy tale heroes and heroines seldom accomplish things completely on their own. They have helpers and allies.You have to be skillful. Fairytale heroes and heroines know how to do things. Spinning the finest linen, sewing shirts out of nettles, cleaning houses on chicken legs — your skills will come in handy, especially the lowly skills that people might not value. Snow White is not just the fairest in the land — she is also an excellent housekeeper.You have to be patient. One commonality among fairy tale heroes and heroines is that they had to wait and endure, whether at home or, as in “East of the Sun and West of the Moon,” through a long quest to find the husband you thought was a bear, but was really a prince in disguise, and has now been taken away to marry an ogress.These are all valuable attributes when you’re trying to resist a power structure intent on restricting or even crushing you. Cleverness, kindness, skillfulness, patience — possessing these attributes, but also valuing these attributes more than power and wealth. I think that’s what fairytale resistance looks like. We live in a society that worships power and wealth, but what fairy tales tell us again and again is that those things are illusory–they can be won or lost, and ultimately they are always lost. English fairy tales end with “happily ever after,” but most traditional tales end with a phrase like “and they are still celebrating, if they have not died yet.” In other words, what waits at the end of every fairy tale, acknowledged by the formula, is King Death, before whom wealth and power mean nothing. Ultimately, the important thing is how you lived.

What fairytale resistance also looks like is telling stories about these things, stories that say “Be clever, be kind, be skillful, be patient.” Resist the mighty, find your own destiny, find your community. Know how to tell a werewolf when you see one, even if it’s dressed as your grandmother — or a politician.

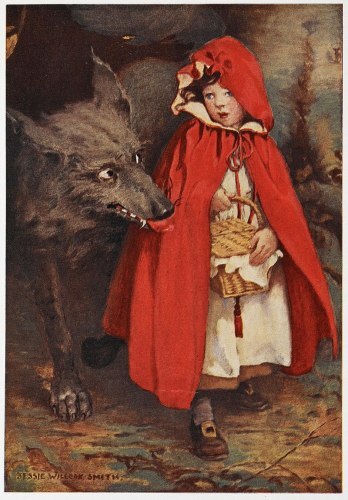

(The image is Little Red Riding Hood by Jessie Wilcox Smith.)

February 2, 2025

What Would Feminine Energy Look Like?

Recently, one of the billionaires who own the technical empires to which we are all subject — a situation I’ve heard referred to as technofeudalism, which would make him one of our techlords — argued that corporations need more “masculine energy.” It’s easy to mock that statement. The technology companies that increasingly control our information and lives are largely male, particularly in their upper echelons, and they are replete with bro culture. There’s a reason their workers are known as techbros.

But when he used the term “masculine energy,” I don’t think he meant biological men. I think he meant that ideas like diversity and work-life balance had “neutered” (his term) corporations. They had become too focused on making the workplace welcoming and comfortable, as opposed to emphasizing “aggression” (again, his term) and competition. It’s a simplistic argument, and predictably, I want to complicate it.

As he did, I want to separate the terms “masculine” and “feminine” from actual biological men and women, and think about them as cultural categories. What would a positive idea of “masculine energy” look like? I don’t think it would look like aggression and competition, unless that competition was with oneself, to achieve a kind of personal excellence. When I think of what “masculine energy” could be, at its best, I think of exploration, discovery, innovation. I think of sailors who wanted to see what was over the horizon, physicists who wanted to understand the fundamental properties of matter. I think of a painter like Van Gogh, who created a way of seeing that had never existed before. Ansel Adams, whose photographs showed us the American West. Political leaders who created new ways of organizing society. I think of strength in the face of adversity, of perseverance. Of intellectual curiosity. It is a kind of energy that looks outward and upward, that wants to get to the moon and then perhaps to Mars. That kind of energy is something both men and women can have. Joan of Arc had plenty of “masculine energy.” So did Georgia O’Keefe.

The dark side of “masculine energy” is aggression, which is unhealthy competition — competition that seeks to break down the other rather than lifting up the self. At its unhealthiest, it’s war.

So then what would “feminine energy” look like? I think it would be a looking inward. Rather than trying to get to Mars, it would take care of the Earth. It would be an energy of care, of conservation, maybe even of restoration. It would be the energy of gardeners, of architects who create cities that are focused on the well-being of their inhabitants rather than a series of attention-grabbing skyscrapers. Of teachers, doctors and nurses, librarians. When I think about where we see this kind of “feminine energy,” I think of Mary Cassatt, but also W.B. Yeats, who tried to preserve and support Irish culture. It’s a kind of energy that does not get much credit, because it doesn’t look as spectacular as the other kind — it’s not as showy to teach a class of kindergarteners as to climb Mount Everest, but it’s arguably both harder and more necessary.

The drawback to talking about “masculine” and “feminine” energy is that those categories are based on cultural stereotypes. In a way, it might be easier to use terms that are more neutral, such as “red” and “green” energy — terms that are not so culturally loaded. But they would also not be as meaningful. They would not convey as much to a reader within this particular culture. I’m using them because I want to argue several things.

First, that these categories don’t map onto biological men and women. Virginia Woolf, creating a new kind of literature, could be seen as an example of “masculine energy.” A father taking care of his children could exemplify “feminine energy,” but so could a soldier defending his country from invasion (like a mother bear defending her cubs). Second, that a healthy person will have both kinds, the looking-outward and the looking-inward, the innovation and the preservation. So will a healthy society. Indeed, the entire profession of psychoanalysis could be seen as based on the “feminine energy” of searching deep inside oneself for answers. Freud might be upset to learn that his work has loads of “feminine energy,” but it does — as opposed to the more “masculine energy” of Plato imagining his ideal platonic forms in some hypothetical cave outside the realm of actual, situated human experience.

Finally, and this is why I wrote this whole argument: that our society (by which I mean 21st century America in particular) already overvalues “masculine energy” and undervalues “feminine energy,” which is why kindergarten teachers and librarians and firefighters and all the other professions that focus on care are underpaid (other than certain doctors, but even then, primary care physicians are paid less than surgeons). Our society rewards the disrupters and innovators. It does not reward the preservers.

We need to spend as much thought and energy on saving the Earth as on going to Mars. We need to pay as much attention to public parks as to skyscrapers. We need to focus on fiber artists and basket weavers and ceramicists as much as Pablo Picasso.

We are in a political moment when disruption is being prized — just this week, parts of the government were shut down. These were parts of the government that take care of people: children, low-income families, veterans. The goal was to disrupt the government in the name of greater efficiency, but in this process the value of care is being forgotten or ignored. There is a reason our society started to care about diversity: it came out of a realization that the institutions controlling our lives (the government, universities, corporations) were fundamentally unfair — that entire groups of people had been marginalized and excluded. And the push for work-life balance came out of a realization that people could not have a life outside of their work, an identify apart from their job descriptions. Both were problems with how our communities function — they can’t function properly when some people are left out, or when everyone is so tired they’d rather watch Netflix than spend time with their families or run for the local school board. We need more “feminine energy” in our political life as well.

I realize my categories and analysis are overly simplistic, and of course you should feel free to complicate them further, but I hope my central point makes sense. We need to take care of our environment, create parks and libraries, pay teachers and nurses, consider diversity and inclusion in our institutions, and make sure parents have time in the evening to play with their kids. That’s the kind of energy we need, whatever we call it.

(The image is Young Mother Sewing by Mary Cassatt.)

January 16, 2025

The Ocean and the Waves

When I was a child, we used to go to Ocean City, Maryland every summer. We used to drive in our old car, my brother and me in the back seat playing some game — usually “Infinite Questions,” which I had made up and which involved one person thinking of an object while the other asked as many questions as he or she wanted, in order to figure out what that object could be. Sometimes we sang “100 Bottles of Beer on the Wall.” There was no air conditioning, so we rolled the windows down, manually of course.

When we got to Ocean City, we always stayed at a small hotel — I would admire the big hotels where the wealthier people stayed, with their private beaches. But our small hotel was close to the public beach, so we would spend the day playing in the sand or swimming in the ocean, then go in the evening to have dinner at the crab shack, where they gave you a bunch of cooked crabs, a mallet, and some pieces of bread to go with the crab meat. The tables looked like picnic tables and were covered with brown paper, because you were doing to make a mess. Later, we might walk along the boardwalk. At the end of the boardwalk was a sort of fair, and one summer I remember there was a man who would guess various things about you, including your profession, and if he could not guess in three tries you would get a prize. My mother challenged him to guess her profession. He asked to look at her hands, then guessed that this short woman with two children and a Central European accent was a doctor on the second try.

It was a cheap summer vacation, and we went almost every summer — I think because my mother remembered her summers as a child at Lake Balaton, and she had a sense that getting children to water was simply what one did in the summer. We spent a lot of time in the ocean — that’s where I learned to swim among the waves.

All of this happened, but at the same time it’s part of a metaphor, because what I want to write about is the difference between the ocean and the waves.

When you swim in the ocean, you’re constantly bobbing up and down from the motion of the waves. But if you dive underneath, what you encounter is a sense of stillness — under the surface, the water does not appear to be moving. (Of course, there are such things as undertows, which are very dangerous. But most of the time, the water under the waves feels still.) Sometimes the waves are small, and they lap at you like a cat’s tongue. Sometimes they’re larger, and then they can be scary, especially when you’re a not-very-large girl treading water. It took me several summers to learn how to deal with those larger waves. What you do is, you dive under them. You dive into the stillness, and the wave passes over you. Then, you emerge on the other side.

Here comes the metaphor. We are all in the ocean, and there are so many waves! It may be an illusion that life seemed to be calmer when I was a child, back when telephones were securely anchored to the kitchen wall and could not follow you about everywhere you went. You could watch the news for an hour in the evening — you did not carry it around in your pocket. I don’t know, it certainly seems to me that we are swimming in a more turbulent ocean, and yet that turbulence may also be an illusion. All times are turbulent, after all. It’s just that we get so much information, more than we can really process. The waves come at us so quickly.

When I started teaching research techniques to my students, the difficult part was finding information. Now, the difficult part is sorting through all the information we have. That’s what we have to do in our daily lives as well — sort through it all and deal with it somehow. A quick look at social media immerses me in the waves: one friend has lost a parent, anther has a new pet, there are fires in Los Angles, new books coming out, the latest scandal or flavor of ice cream. The country is either collapsing or stronger than ever, depending on your point of view. We are inundated.

But if you put down your phone, unless you are in the middle of the turbulence — unless you are fleeing the fires — you return to the relative calm of ordinary life, where not a whole lot is happening at this particular moment. You return to still water. For example, I’m sitting here now, writing about the ocean and the waves, and after that I will need to make lunch, then work on a presentation for a faculty meeting, then continue planning for the semester. Outside it’s cold. The sky is white and there is snow on the ground, as there was last winter. The season moves on at its own pace, and in my own life, the waves do come, but they come much more slowly.

The point I want to make is, it’s so easy right now to feel as though we are swimming among the turbulence, where the waves are the information we receive from all over the world. At least some of the time, to keep from being overwhelmed — from getting salt water in our mouths and eyes — we need to dive down into the still water, let the waves move over us. We need to feel that the ocean is still there, supporting us.

It’s possible that a metaphor is not a good metaphor if it takes so long to explain. But what I want to say is that there are so many waves, but there is also still water underneath. I suggest you dive down into the still water. What is the still water? Well, the passing of seasons, for one. It’s winter now, and eventually spring will come, and that will happen over and over during our lifetimes. It’s a pattern we can hold on to. Another thing we can hold on to is good art. Fashions will come and go, and millionaires will buy fiberglass replicas of balloon dogs, but there will still be museums filled with beautiful paintings. You will still be able to go stand in front of a Monet. And good books will remain. There will be bestseller lists, and categories will have their day, but you will still be able to reach for Jane Austen or L.M. Montgomery. The best authors of my childhood — Ursula Le Guin, Patricia McKillip — are just becoming clear now. It takes a while to see what was truly worthwhile, what lasts.

In retrospect, it was a valuable lesson, learning to swim among the waves. But it’s only recently that I’ve appreciated its value as metaphor, as I’ve felt the turbulence of our times and tried to figure out how to live my own life without being overwhelmed by it. I just have to remember — if you dive down, there is always still water underneath.

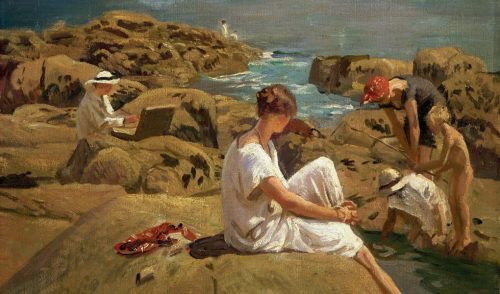

(The image is On the Rocks by Laura Knight.)

December 30, 2024

Nothing is Wasted

Sometimes I get mad at myself for wasting time.

I have wasted time in the most ridiculous ways. I’ve watched YouTube videos on the history of ballet pointe shoes. I’ve watched Saturday Night Live skits about bridesmaids, and motivational speakers who talk about the need for a bedtime routine, and kittens being rescued in various ways. Don’t get me wrong, it’s a good and worthwhile thing to rescue kittens and have a bedtime routine. But there’s no need to watch videos about those things. I’ve read articles on decorating cottages in the Cotswolds and opinions pieces about the latest political shenanigans in Congress.

None of these things have helped me in obvious ways, so it’s easy to say they are a waste of time. Why do I watch or read them? I tried to think about why — boredom? Addiction to my phone? But the most obvious answer seemed to be curiosity. I saw a kitten in a drainpipe, and I wanted to know what happened to it. The ballerina showed me a pair of pointe shoes, and I wanted to know why. I saw a picture of the cottage, and wanted to know who had moved into it and why it had been painted that particular shade of green.

I am addicted to something, but it’s not my phone, or social media, or the news. What I’m addicted to is stories. With equal attention, I will watch a kitten rescue video or read an article in The Atlantic or start on a novel. And I will turn from one to another, or intersperse them — yes, I can watch an SLN skit on bridesmaid karaoke and then turn to a novel by Isabel Allende. One is serious literature, the other is — well, it’s sort of mental fast food, like french fries for the mind. And yet, I want to make an argument here about what it means to waste time as a writer.

What I want to argue is that . . . nothing is really a waste of time. In “The Art of Fiction,” Henry James wrote, “Try to be one of the people on whom nothing is lost.” These are the things that should not be lost on you when you’re, for example, watching a kitten rescue video:

What kind of kitten is it? Is it a black kitten with a white nose? How large is it? How large is the drainpipe? How did the kitten and drainpipe come to inhabit contiguous spaces?Who is rescuing it? What sort of voice do they have? What are they videotaping? Can you see their hands? Their feet? What techniques are they using to lure the kitten — the tried and true tuna method? Something else?What will the subsequent story of the kitten be? Will they adopt it? Foster it? Is it going to a shelter? If there is a happy ending to this story (and there almost invariably is), what is that happy ending?What storytelling techniques is the videographer using? What is the beginning, middle, and end? Are you in suspense? Is there music added? How are your emotions being affected and possibly even manipulated?Who are you, lying on the sofa watching the kitten rescue video? Are you doing it because you’re tired? Bored? Desperately in need of reassurance that this is a world in which kittens are rescued?All of those things are elements of story. All of them are things you can learn from as a writer, a storyteller. You can learn from them consciously, but even if you’re just lying on the sofa, vegging out (what kind of vegetable are you? a carrot? a cauliflower? and why?), your subconscious mind is learning learning learning, because if you’re a writer, it never stops learning.

Now, this is not to say that you should spend your entire life watching YouTube videos, or even reading The Atlantic. Or even reading Isabel Allende. At some point, you need to do what you were made for and actually write. But as you write — as you try to capture your ideas in prose or verse — everything you ever watched or listened to or read will come to help you. It will form the mental material for you to work with. A joke you heard a comic tell on a Netflix special will suggest a way a character can say something, a turn of phrase. You will describe the utter mess a character makes of a bedtime routine, and that mess (“Lydia could not fall asleep. Had she meditated the wrong way? There was a right way and a wrong way, and surely she had done it the wrong way. She should get up and watch that YouTube video again. The woman with the soothing voice, who had tortoiseshell-framed glasses and some sort of PhD although it was not entirely clear what her doctorate was actually in, would tell her. And then she would mediate the right way, and be able to fall asleep. She checked her phone. It was 3:10 am.) becomes characterization.

I would expand this to more than YouTube videos or podcasts or magazine articles. Try to be one of those people on whom nothing, not the colors of the fall leaves, not the way to darn a sweater with a hole in it, not the various ways in which people speak when they are just starting to learn English, is lost. Watch and listen and learn. Notice and notice and notice. Be infinitely curious. Have a hundred tabs open in your brain.

Recently, for the novel I’m currently working on, I had to research Pop-Tarts. Did you know that there are now chocolate chip pancake Pop-Tarts? What strange, uncanny things they are, those toaster pastries: neither quite breakfast nor dessert. When does one eat them? As far as I can tell, they are almost always eaten as snacks. There is, in fact, no proper time to eat Pop-Tarts except in between meals, surreptitiously, hiding the crumbs afterward. In my novel, there is a fairy creature with an inordinate fondness for them. They seem like the sort of thing fairy creatures would like.

One nice thing about being a writer is that nothing is ever really wasted. As long as, afterward, you write about it . . .

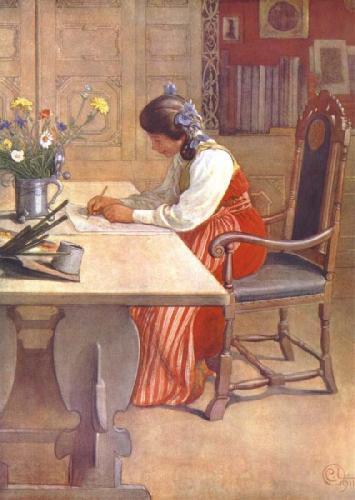

(The image is Hilda by Carl Larsson.)

December 3, 2024

Absolving Myself

There is a scene I have always liked in movies. It is when a priest administers absolution. He makes a particular gesture that means “I absolve you of your guilt, your sin, your transgression. You are forgiven. Go and do better.” There is always a sense of relief afterward, a sense that now the protagonist can start over. A sense of renaissance, new birth.

I was thinking about this recently because it seemed to me that after a period of intense productivity in which I published a novel every year, the last of them in 2019, I had a period of about five years in which I was much less productive. I wrote short stories, poems, and essays, and I even published some collections, but no novel. And of course I wondered what was wrong with me, what happened to derail the plans I had made for myself, which of course included writing more novels.

And then I looked back, and realized. The Sinister Mystery of the Mesmerizing Girl was published in 2019. At that point, I knew that I needed a break — my schedule for the second and third Athena Club books had been so tight that I was exhausted. But I had plans. I remember talking about them at the World Science Fiction Convention that year — it was in Dublin. And then, in January 2020, Covid happened. That semester, we started on campus and ended on Zoom. In the fall, I taught remotely. The next spring, I taught hybrid classes. The fall after, I was granted a Professional Development Leave of Absence to develop a curriculum that focused on creativity and innovation in writing pedagogy. The following spring, the spring of 2022, I taught on a Fulbright Fellowship in Budapest. The Covid pandemic was ending, so I started teaching on Zoom and ended on campus. That was also the year Russia invaded Ukraine, the year of refugees coming across the border. Right after the Fulbright, I taught a summer semester in the College of General Studies London program. The following year, I taught a full CGS curriculum for the first time. Which brings us to the fall of 2023.

In the fall of 2023, I applied for a permanent position at CGS. In the spring of 2024 I went through the interview process and got the teaching position I had applied for, which made me so glad and grateful. At the same time, I was going through the process of getting ultrasounds and biopsies for a lump on my neck that the doctors eventually decided might be cancerous. At the end of spring semester, I had surgery. Fortunately, there was no cancer, just some odd-looking but completely benign cells. That summer I taught in London. And then, in the fall, I went to Budapest and opened up the manuscript of the novel I had planned so long ago, which I had barely started before Covid hit. And now I’m working on it.

So there you go. Why wasn’t I as productive as I had planned to be in the past five years? Because in those five years, I have not had a single semester that has been the same, in which I’ve been able to say, “It’s fine, I know what I’m doing.” I’ve been working and learning, and I’ve loved most of it, except the Covid and the surgery. I really do love being a teacher, and it’s a joy to work with my students. But the truth is that writing is work, hard work, work that takes time. I love doing it, and I do it for the love of putting words on a page, but it’s not something I can do in bits of time between doing other things. Poetry, yes. A novel, no. That takes focus and concentration.

So I’m officially absolving myself. I’m making that priestly — in this case priestessly — gesture that means I am forgiven. And if you need absolution, if the last few years have not been as productive for you as you would have liked and you’re feeling guilty, then consider yourself absolved as well. You don’t even have to confess anything, and you don’t need to be particularly contrite. Believe me, I know you feel badly enough about it already. If you’re anything like me, you carry a load of guilt for all the things you did not do, or did not do well enough, as well as for the dishes in the sink and the fact that you haven’t vacuumed for a while.

Let’s start fresh, like pieces of laundry hanging on the line. Let’s figure out what we want to do now, and not worry about the past. It has flown away like a flock of swans, and we are left with a field of possibility that we can fill with more swans, or dancing princesses, or a carnival. If you’ve already started working on something, go you! If not, get out a fresh notebook, or a blank canvas, or whatever you’re going to start on. Figure out what you want to do, and go do it.

Of course, if you’re still in the middle of a great muddle, just hang in there and get through it. But I’m grateful that for the first time since my last novel was published, my life feels relatively stable. Of course, there are crazy things going on all over the world — our political situation is fraught, the climate is out of whack, and it’s entirely possible that humanity will destroy itself within the next few years. But in the meantime, I’m going to be writing.

(The image is Cloister Lilies by Marie Spartali Stillman.)

October 22, 2024

Writing a Poem

I was thinking about what is hardest to write, and I ranked the various things I write from easiest to hardest: essays, stories, poems.

In terms of word count, poems are definitely the hardest and most time-consuming. Yesterday, I spent an entire day working on a poem, one I had already spent several days working on. It just would not come right. When a poem does not come right, it feels as though you’ve been bitten by an insect, and the bite is itching and itching. You keep scratching, but it does not bring relief. Every time you think the itching has stopped, it starts up again. And then, when the poem does come right, it feels as though you’ve finally discovered Calamine lotion, and it’s actually working. There’s a sense, not of joy or fulfillment, but of relief. Finally, you think. The damn thing is done. At that point, you’re angry with the poem for even existing. What began with a sense of delight has become a source of annoyance. You tell the poem, if it weren’t for you taking up so much time, I could be writing a novel and becoming a famous novelist, or a great novelist, or a rich novelist — or all three, like Charles Dickens. But no, here I am working and working on a poem that probably ten people will read . . .

Poetry sucks.

On the other hand, I must love it or I would not write it. And I do. Poetry is the only thing I write that feels as though it could achieve a kind of artistic perfection. A completed vision. I often tell students, only poetry is capable of being perfect, and only one poem has ever actually been perfect (John Keats’s “Ode to Autumn”), so there is no point in trying to write a perfect story or a perfect novel. It’s just not going to happen.

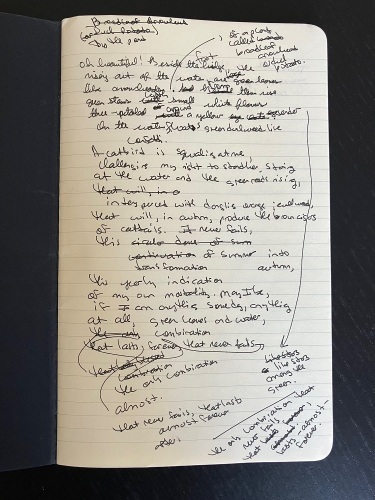

Would you like to see what my poetic process looks like? If not, you can stop reading now . . . But if you want to see, I’ll show you. Recently, I wrote a poem that annoyed me very much. I wrote the first draft back in September, with a pen in the notebook I carry around in my purse, standing on the footbridge described in the poem and looking at the leaves growing up from the water below. I didn’t know what the leaves were, so I did an internet search on my cell phone, and they turned out to be broadleaf arrowhead leaves. Then, I wrote a poem about them. It looked like this:

Then I did not do anything for a while. I was in Boston and there was just so much I needed to accomplish before I could come to Budapest. But of course I brought the notebook with me. Finally, after dealing with a plumbing problem in Budapest (a broken pipe in the apartment above mine), I had time to write. I typed up the poem, revising as I did so. At that point it looked like this:

The Broadleaf Arrowhead (or Duck Potato)

Oh beautiful! Beside the footbridge,

rising out of the water, are the large green leaves

like arrowheads, of a plant called broadleaf arrowhead

or duck potato. From among them rise

green stems with clusters of white flowers,

three-petaled around a yellow center, as though stars

were scattered among the green. And on the water floats

green duckweed like confetti. A catbird

is squawking at me, challenging my right to stand here,

staring at the water and the green reeds,

interspersed with dangling orange jewelweed,

of bulrushes rising behind the arrowheads,

with their own stems, taller and a darker green,

that will, in autumn, produce brown cigars of cattails.

It never fails, the yearly transformation

of summer into autumn, that annual reminder

of my own mortality. May I be,

if I am anything someday, anything at all,

green leaves and water, the only combination

that never fails, that lasts almost forever.

And I felt that terrible itching. I had words, even some of the right words, but they weren’t in the right order. They didn’t have the right rhythm. They hadn’t found their proper places yet, and I was missing some words — I was sure I was missing some words. I would need to learn more about the broadleaf arrowhead. So I did some research — yes, I did research for a poem. Honestly, this poem could come with a bibliography! At some point, I was going to include information about how the broadleaf arrowhead was also called the wapato, which is a word the native Chinook used to mean “potato” when speaking with French and English traders. It’s not a Chinook word, but a jargon word they used because the traders could not speak proper Chinook. (I learned that “jargon” is a linguistic term meaning an “occupation-specific language.”) That went into the poem and came out of the poem because it just didn’t fit. It made the poem sound like a middle school history report.

When I tried to describe the broadleaf arrowhead itself, I needed other words I didn’t know, words like “scape,” “raceme,” “inflorescence.” I needed to know that “whorl” is a technical term in botany. I put things in, took things out, moved things around. It all became rather complicated. Somewhere along the way, I realized that the poem was mostly in a sort of rough iambic pentameter, and I thought, why don’t I commit to the meter? At that point, I almost gave up and deleted the whole thing. This was about a week after I had initially typed it, and I had returned to it over and over, as I had time, obsessively trying to get it right.

Finally, it looked right to me, and I posted it. And then I thought, wait, there are just a few things I could fix . . . So I fixed them. Somewhere in that process, I realized the second stanza had eight lines and the first stanza had fifteen lines, which didn’t feel right. So I added a line to the first stanza. Eight and sixteen just felt better . . . It’s such a strange process, mostly of intuition. But at the same time, I was constructing something, and it needed to be structurally right. It needed to have sixteen lines, then eight lines, and to be in a kind of iambic pentameter (if you don’t look too closely).

And now the poem looks like this:

The Broadleaf Arrowhead (or Duck-Potato)

Oh beautiful! Beside the footbridge, growing

out of the water, are the large green leaves

of a plant called broadleaf arrowhead or duck-potato.

Among them, from the water, rise green stems

called scapes, along which grow its small white flowers,

each with three petals around the yellow stamens,

arranged in whorls along a central raceme

and clustered in a pattern called inflorescence,

like stars against the green. Beneath them float

lenticular leaves of duckweed, like confetti.

An angry catbird is squawking from its perch

among the bulrushes, as though to challenge

my presence in this tangle of summer foliage —

the arrowheads, the dangling orange jewelweed,

the rushes whose stalks, rising from tall green blades,

will, in autumn, produce brown cigars of cattails.

They remind me of the annual transformation

of summer into autumn, and of course,

inevitably, because I am only human,

my own mortality. May I become,

someday, if I am anything, anything at all,

this, right here, despite the annoying catbird —

green leaves and water, the only combination

that never fails, that lasts almost forever.

I don’t know if it’s any good, but it’s finally what it wanted to be, or I wanted it to be, or Erato, the muse of lyric poetry, wanted it to be. I don’t know who wanted the poem to be this way, but it finally feels finished. It finally feels like Calamine lotion . . .

So that’s it, that’s my poetic process. I honestly don’t know why I write poetry, except that it does something good to my brain — my brain feels right afterward. It feels as though it’s been used to do what it was designed for. That won’t make me a rich, famous writer, and it may never make me a great one, but it probably makes me a better one. I hope.

September 22, 2024

A Lament for the Stores

Once upon a time, there were stores.

From my apartment in Boston, I could walk to two grocery stores. Granted, they were a Whole Foods and a Trader Joe’s, so it felt like living in a posher, more expensive area than I would have liked. The Whole Foods had actually replaced a health food store that had replaced a Market Basket. For anyone who doesn’t live in Boston, Market Basket is a local chain, founded by a local family, that serves ordinary middle-class communities. The health food store did not last long, because the community could not afford its more expensive offerings. The Whole Foods lasted a few years, but about a year after Whole Foods was acquired by Amazon, it left. That spot was empty for two years.

While the Whole Foods was still there, that strip also had a hardware store where I could buy all the things I needed to hang pictures (hammers, nails, those little bent things that the nails go into), lamps, ladders, cleaning supplies, unfinished wooden shelves, garden equipment, plants, and in December, Christmas trees. The landlord who owned that strip evicted the hardware store and built a metal awning, hoping the space would be filled with restaurants. So far it has been filled with one takeout place and one bubble tea shop. The rest of the space stands empty.

In the other direction, there used to be a Walgreens and a Gap, as well as a gourmet food store. The Walgreens went away first, to be replaced by a bank. Now there are four different banks in that area. The only drug store left is a CVS, which used to be a good CVS until the management brought in two checkout machines and reduced the number of clerks. At that point, the store started having a problem with shoplifting. So it put much of the merchandise behind plastic panels that have to be opened by a clerk. Did I mention there are not enough clerks? I’ve waited half a hour for a clerk so I can buy toothpaste. The Gap went away, as did the gourmet food store. Some of those places now stand empty, although the Gap was replaced by a daycare center, which is surely a good use of the space.

Near the university, the same sort of thing has happened. Once, in Kenmore Square, Boston University had a big, beautiful Barnes & Noble. It was three floors, filled with the most wonderful books, and on the first floor it had a café. I used to go there to meet graduate students and colleagues. Across the square was a Starbucks. The Starbucks left first, I don’t know why because it was quite heavily used by students. The building with the Barnes and Noble in it was sold, and now it’s some sort of office building advertising retail space on the first floor. No one has moved into it, so it’s just empty storefront. The new building next to it, which replaced a rather pretty although delapidated early 20th century structure, is the most boring building I have ever seen, made of prefabricated material that went up quickly. It has a sign on top that says WHOOP, so it must be the headquarters of the “wearable technology company” (I got that from the Internet) of that name. Honestly, I think they left off the final S — the building deserves a big sign that says WHOOPS. It also has empty storefront on the first level, with big fancy windows that look like dead eyes. The post office where I used to pick up packages and the corner convenience store where I used to buy chocolate no longer exist.

Kenmore square still has a bar and a few restaurants, but I don’t go there anymore. Why would I? There is nowhere to meet, sit down, have a cup of coffee. Nowhere to browse, nowhere to buy anything.

So many of the stores have gone. I lament the hardware store especially. Now, if I need the sort of thing that can only be bought in a hardware store, I must take the metro to Target or order from Amazon. I order from Amazon a lot more than I used to, not because I want to, but because I don’t have time to wait in CVS until a clerk can get away from watching the checkout machines to liberate a jar of face cream from its plastic prison.

It’s not a consistent phenomenon, of course, but it seems as though we’re losing the stores. I’m lamenting this for several reasons. First, I generally don’t want to buy something online. I want to see it, to make sure I like it, that it fits or that the proportions work. When I order something online, there’s a chance that, although I used measuring tape to make sure the lamp would be the right size, it is not, somehow, the right size after all. It doesn’t fit, and then I need to go through the further step of returning it. Second, I want to walk to the store. I want to walk and browse and get out of my apartment, see other people, listen to random conversations. I want to pick out my own apples and peaches.

I don’t know if this is a particularly American phenomenon, but in both Budapest and London, I was surrounded by stores. Budapest is the best, in that way — within a fifteen minute walk of my apartment there are about five different grocery stores. There are cafés, places to buy ice cream, a place to buy flavored cheesecake in little glass jars, a hummus bar, restaurants of all sorts, shops for both new and used clothing, stationery stores, book stores that sell Hungarian and German and English books, stores for ceramic flowers . . . And of course there is the Great Market Hall, where you can buy vegetables and meat and cheese from stalls. In some ways, except for the height of the buildings, Budapest is more like New York than Boston. In London last summer, I was in quite a posh area near Sloan Square, and many of the stores were expensive boutiques. Still, I could walk to three grocery stores and there was a Waterstones nearby. There were hardware stores and stationery stores in the general neighborhood.

The one good thing about my Boston neighborhood is that we do have an independent bookstore. It recently expanded, and it seems to be doing very well. But I lament the passing of the other stores. Whether they were chains like Gap or small boutiques, they gave us somewhere to go. I’m particularly sad that Kenmore Square has become a kind of corporate desert. The students deserve better. They chose to come to an urban university, and they deserve what a city should give everyone — a lively street culture. Cities need life and soul. Bostonians will remember the old Harvard Square, before it too became a kind of corporate desert. I still go there sometimes to buy office supplies from Bob Slate, but otherwise, why bother?

I don’t have any words of wisdom here — I’m just sad to see the city change, and I think it’s a bigger issue than one city, one neighborhood. I’m always glad when the trend reverses itself — after two years, the empty Whole Foods was replaced by an H Mart that seems to be doing a lively business. But if I’m living in a city, I want to live in a neighborhood with a grocery store, a pharmacy, and a hardware store that I can walk to. In a really ideal location, I also want a café and a bookstore. That does seem to be the minimum for good urban living?

I’m very lucky to live where I live and work where I work. But I miss the stores . . .

(The image is The Shop Girl by James Tissot.)

September 15, 2024

Writing My Stories

In the last few months, I’ve written three stories.

Two were stories I was asked to write. One is a retelling of “Sleeping Beauty” from the ogress’s perspective. (You don’t remember an ogress in “Sleeping Beauty”? Read the Charles Perrault version, originally published in 1697. There’s an ogress . . .) Another is the secret history of Mina Harker, whom you may remember from Dracula. The fairy tale retelling is for an anthology; the Dracula retelling is for my next short story collection, coming out in 2025 from Tachyon Publications. The third story, which I finished just yesterday, is one I wrote for myself, although of course I’ll try to publish it somewhere. It comes from an incident I saw in Budapest — an older woman who, to my surprise, stopped by the planter in front of my apartment building, pulled up a plant, put it in a plastic bag, and walked away. She stole a plant! I stood and stared, astonished. And of course it gave me the idea for a story.

People sometimes ask me how I get ideas for stories, or whether I have trouble coming up with ideas, and I say no — the ideas are the easy part. There are ideas quite literally everywhere. They fall out of the air like rain. A woman steals flowers, I read a poem or hear a song, I read a book and think That’s a great plot but I would do it differently, I visit a beautiful place and it gives me a story. There are stories everywhere I go. The hard part is writing them down, and the even harder part is finding time — that is literally the hardest part for me, because I so often have very little time. And the most difficult thing about writing, for me, is prioritizing my writing time.

I don’t know if you have this problem, but it’s very difficult for me to prioritize what I would most like to do over my obligations to other people. I’m very lucky to have a job that I love, which is teaching. But I have obligations to many other people — my students, my department, my university. And then there are obligations to family and friends, which are important as well. Sometimes, writing feels like an obligation only to myself — if I don’t write, it will affect only me, whereas if I don’t grade essays or write letters of recommendation or participate on the assessment committee, it will affect other people. It’s easier to let myself down than to let other people down.

And yet, it seems to me that there is another perspective: if I don’t write them, I let the stories down. And I let down anyone who may want to read those stories, who might find some benefit from them, even if it’s the ability to get away from our difficult world for a while. And I do know this about myself as a writer — I have a power to take people away from this world and transport them somewhere else. That is one thing I know I can do. Beyond that, there is something more difficult to describe — I let down wherever those stories came from. I’m not arrogant enough to think those stories came solely from me. I don’t just think them up. Parts of them come from me, certainly. But when I’m writing, it feels as though the story is being told through me, in collaboration with me. The source of stories is pouring through me like a river, and I am both channeling it and riding it on some sort of writing kayak. It’s as though I’ve been given a job by the university, which is to teach students — and I hope I do that job well, but I’ve also been given a job by the universe, which is to tell whatever stories are out there to be told.

I suppose thinking about it this way may also help with the other problem, when you’re a writer, of feeling as though there are already so many stories out there. Walk into a bookstore or library — you will be overwhelmed (or at least I am). And then there are all the shows on Netflix, all the videos on YouTube. There are already so many stories, most of them more spectacular than mine. I mean, how could what I write compete with a Netflix series?

And yet. You never know what will be important. There was that guy, the one you would probably have avoided if you had seen him in a café, because he was, admit it, kind of weird. And he painted these weird paintings which you probably wouldn’t have bought, because no one was buying them. There he was, in the small town of Arles, and almost no one was paying attention to him, and he was painting and painting and painting. And now one of his paintings is on my umbrella, which is as close as I will ever get to owning a Van Gogh. So you never know.

All you can do, as a writer, is try to let go of your ego as much as possible, and write the stories that are given to you, as best you can. Like painting and acting and dance, it’s one of the great humbling professions. You will fail again and again and again, because failure is the essence of trying to create anything. And whenever you walk into a bookstore or library, you can see all the great writers, right there on the shelves — you can see that Virginia Woolf is already there, and F. Scott Fitzgerald is already there, and you’re not going to be as great as they are, because no writer can be another writer. You’re going to have to figure out how to be great, or even pretty good, or maybe even not very good, in your own way.

This is, perhaps, why AI will in the end not be very helpful for writers of anything more complicated than undergraduate essays (and not even in those, I would argue). You need to have your own failures before you can have your own successes. AI isn’t telling the stories the universe gave you to tell. It’s telling bits and pieces of stories that other writers told, patched together like the Patchwork Girl of Oz. Using AI to create a story makes you, not a writer, but an editor, which is a different job altogether. I’m sure there are people who will disagree with me, but for me, writing is in the direct engagement with the words on the page. It’s in the intersection between what comes to me from somewhere outside myself, and the skill and thought I put into capturing it, structuring it. It’s dancing with the universe, not with a machine.

So, what will I do with my flower thief story? Well, I have a few ideas. Right now, all three stories still need some revisions, so next week I will be a reviser rather than a writer. But my goal for this year, especially for the next few months, is to create space and time for writing. After all, I have an obligation to the universe. And the rest of it — whether my stories are published, whether they find an audience, whether they eventually appear on umbrellas (all right, here I’m kidding — a little), all of that is ultimately up to the Fates, who always have their own agenda.

(The image is Old Woman Watering Flowers by Gerard Dou.)

September 8, 2024

Collecting Scars

I think life is a process of collecting scars.

Mine are inconsequential, all things considered. The oldest ones are the marks from immunizations: smallpox on one arm, tuberculosis on the other. If you were born in the United States, you won’t have these. But when I was a child, in socialist Hungary, we were still being immunized against Victorian-era diseases. So I have a round scar on one arm the size of a five-forint piece, a smaller round scar on the other. There is the small round scar near one eye from having chicken pox, and the small straight scar near the other eye from a rowdy-boys-during-gym accident in high school. After I got that one, I was wheeled through the school in a wheelchair with blood flowing down my face. I felt quite injured and fancy! When my mother looked at it, she said, “Oh, that’s nothing. Wounds like that always bleed a lot.” Then she put a few butterfly steri-strips over it, and that was that.

Then there are my two appendectomy scars from graduate school. I suppose they mark where the video camera and surgical tools went in. I can barely see them now. And then there is the scar from the thyroid lobectomy in May. That’s the largest and most prominent, of course. I still don’t know how I feel about it. Perhaps I will feel differently when the internal scar tissue is not so palpable. Right now, four months after the surgery, it still feels like I have a rubber eraser in my neck. I’m still using scar gel and SPF 50, still doing scar massage, the way they demonstrate in the YouTube videos. I feel very lucky that there have only been two serious problems with my health so far — appendicitis and recurring nodules on my thyroid — and that they are very common problems to have. All in all, I’ve spent very little time in hospitals.

Nevertheless, I think life is a process of collecting scars. They don’t go away, not fully — they are like marks on the map of your body, showing where you’ve been, what you’ve experienced. Time writes your history on your skin, just as you might write it in a journal. Except, of course, that time’s journal is public. You can see the scar on my neck, although it’s slowly fading. And when you see it, you might ask yourself (if you’re too polite to ask me), What happened there?

But I was thinking too of the scars that are not written on our skin, the scars that are inside, that affect our hearts and minds. Life is a process of being wounded, healing, but then feeling the scar left behind — because I think there is always a scar left behind. From each hurt, each loss, each failure. And then it’s a process of waiting as we heal, of trying to help the healing process. The first medicine for my surgical scar was oxycodone. For heartbreak, the first medicine might be hours of watching Netflix, which would have a similarly numbing effect. Instead of applying scar gel, you might apply ice cream where it hurts. Or music. Or long walks. Or, of course, therapy.

I suppose it depends on the depth of the wound, the extent of the scar. For some wounds, the process of healing is long, and the resulting scar can limit your mobility, your flexibility — this is as true for mental and emotional scars as physical ones. I don’t know what the process of scar massage might feel like for these internal scars. I’m not a therapist. But there must be one — there must be a way of dealing with them so they hurt more in the short term, but less in the long term. Hopefully, if I’m diligent about the massage part of my therapy, the rubber eraser in my neck will eventually go away, and I won’t feel it each time I swallow.

So I guess I don’t really have any wisdom here, because scars aren’t exactly beautiful, and saying that everyone becomes scarred is not an optimistic statement. The scars fade, but never completely. But I’m not trying to say something wise or optimistic. Rather, I’m trying to say something about how I’m experiencing life right now, which is as a relentless march of time that marks you as it passes. And yet, and yet, we also write on paper, and that is as valid as what time writes on our bodies.

Perhaps it is the way we respond to how time scars us. Perhaps the marks we make on paper are the way we take time’s power into our own hands, make our marks against time. We say, “You may scar my body, but look — these words will outlast me.” Whether on clay or papyrus or parchment, we have been doing this since writing began. And now here I am, doing it on a computer screen, writing, “I think life is a process of collecting scars.” And perhaps, just perhaps, if these words are shared and copied and remembered, they may outlast my physical body. Or other words of mine may be the ones that last, who knows? And so, I continue to collect scars and make my marks on the computer screen, as I am doing now.

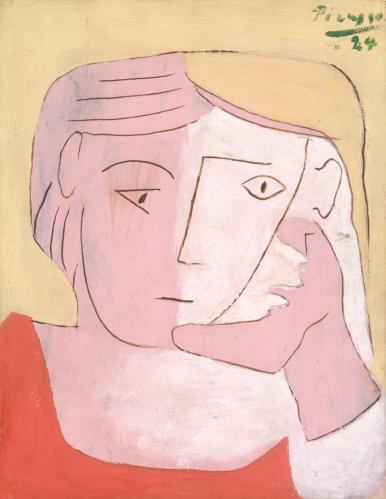

(The image is Head of a Woman by Pablo Picasso.)