Theodora Goss's Blog, page 9

June 16, 2017

Trying to Recover

I’m still trying to recover from this academic year.

It’s been the hardest academic year I’ve had since the one in which I finished my doctoral dissertation (when I went to see a therapist every Thursday, like clockwork). The strange thing is, I’m not sure why it’s been so hard — this time, there’s no particular reason, no single thing that has made the year difficult. It’s just been the workload. Somehow, I’ve felt like a machine, producing producing producing, always for other people. Producing lesson plans, assignment sheets, comments on finished work. Even the work I love to do, whether writing a paper about fairy-tale heroines or a book on girl monsters, has often felt like a chore, something I needed to complete. There has been very little joy this year.

I should not complain, because I’m incredibly lucky. I have a job I mostly love and that gives me a lot of freedom. I have a lovely apartment in a city I like living in. I’m healthy, and when I’m not, I have healthcare. I have a book coming out, which is of course a dream come true. I have a smart, creative, wonderful daughter. I’m deeply, truly grateful for all those things.

At the same time, there is an underlying problem. I can see it when I look at my files: this year, I’ve written one very short story and eight poems. Granted, I’ve been writing the sequel to my first book, and at the moment that’s 200K words long. When I sent it to my editor, months late and much longer than it was supposed to be, my only comment was, “Is this actually two books?” But this is a year in which I’ve written very little for the sheer joy of it, simply because I wanted to. (I love that second book, but I’m not naturally a writer who goes to that length — my comfort zone for a novel is 80K to 120K words.) And perhaps most importantly, I’ve been consistently, persistently tired. I never get enough sleep — that’s partly a function of having so much to do that I keep pushing myself, staying up late and getting up early, and partly being so anxious about all the deadlines and obligations that I don’t sleep well.

Not getting enough sleep is the worst. It’s the thing that throws everything else off. Last night I didn’t mean to stay up until 4 a.m. finishing some work, and yet there I was, yet again. I was awake by 8:30 this morning. I don’t care what CEO boasts about getting four hours of sleep a night — it’s not enough, not for me, not anyone, and yet all year I’ve been getting by on four to six hours a night. No wonder I feel sick . . .

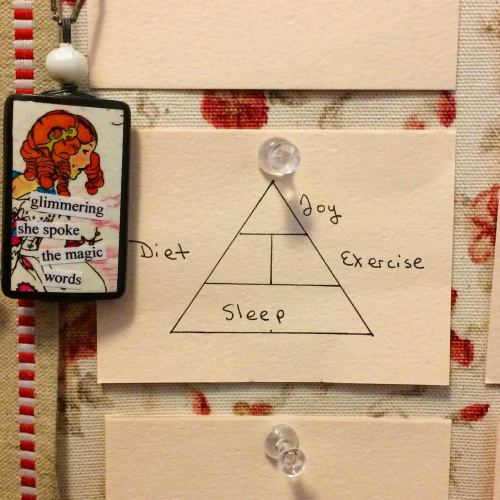

So I need to recover. The question is, how? Get more sleep, obviously, but that’s also a symptom of deeper problems. Eat well, exercise. I’m actively working on those. Above my desk, tacked to my corkboard, I have inspirational quotations, because that’s who I am, inspirational-quotation-girl. Well, some of them are admonitory, there to remind me of things I tend to forget. Among them is a picture I drew of a pyramid with three levels. The bottom level is sleep, the next one up is diet and exercise in equal measure, and the top of the pyramid, the peaky hat, is joy. You need the things in the bottom two layers, but you need joy as well: it filters down from that top layer and affects whether you can keep up with the things we assume are more basic. I, too, tend to assume that joy is a sort of extra, something you can get once you fulfill the duties (sleep, diet, exercise). But that’s wrong. if you attend to the joy, it makes everything else easier.

(The pendant to the side was given to me by a graduate student of mine whose book is coming out this year. I’m so proud of her!)

So, where to find joy? Or how to create it? I think different people find or create joy differently. For me, it comes easily as long as I have time to do things that are of no use at all. That have no monetary value, that are not attempts to learn anything, gain anything, accomplish anything of value. That are just messing around. Writing this blog post gives me joy. (Blog posts have been pretty sparse lately, as you may have noticed.) Walking around in a garden or park gives me joy. Reading purely for pleasure. Watching movies in which people in a small English village murder each other. (That sounds gruesome, but a good murder mystery makes me intensely happy.) Learning about things when I don’t have to (like poisons or bird species). Anything that does not involve duty or obligation or deadlines. In other words, I’m one of the people for whom joy is easy — I just need to get out of my own way.

So recovery is going to take more than getting a bit of sleep. It’s going to take me thinking about what sort of work I take on. I do need to take on a lot of work: I have a job, and a job on top of that, and then there’s the writing. None of that works without my doing a lot. But somehow, I have to carve out spaces for myself. I have to not get overwhelmed with the amount I need to do. I have to fit in time for goofing off, because that goofing is actually healthy. It’s joyful.

I’m going to be working on it. Meanwhile, I have things to do, but sometime today I’m going to start reading that book on poisons . . .

(This is me, looking tired, as I have all semester. But it’s summer, and there are roses . . .)

April 16, 2017

Writing Girl Monsters

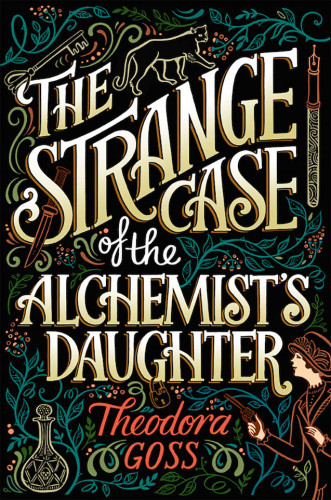

I have a novel coming out this summer. It’s called The Strange Case of the Alchemist’s Daughter, and it’s about Mary Jekyll, daughter of the infamous Dr. Jekyll, who discovers that her father belonged to a secret society of alchemists . . . a society whose members were creating girl monsters. As the novel progresses, she meets Diana Hyde, Beatrice Rappaccini, Catherine Moreau, and Justine Frankenstein, all created through strange experimentation. I’m not giving you any spoilers, by the way. All of this is right on the book jacket!

Since the book is coming out this summer, I’ve started to see some mentions of it online, on various blogs or websites. There was one in particular that made me smile: a blogger listed books she would never, ever read, and mine was on it. Why would she never read it? Because I was rewriting stories written by others, rather than creating stories that were uniquely my own. You know what I would say to that blogger? You’re doing it exactly right. You know what you do and don’t want to read, and you’re not going to read books that don’t interest you. That’s exactly what readers should do. Read what you’re interested in — what makes you laugh, and cry, and happy to be alive. That’s what really matters. That’s what I would tell her.

But I do want to say something, to anyone else who might be interested in this book, about why I’ve written it — why, specifically, I’ve written a book about girl monsters, or in some cases monstrous young women (they range in age from fourteen to twenty-one). Let me tell you their stories, as they originally appeared:

Mary Jekyll: Of course, Mary does not appear in The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. I made her up entirely. But I made her up for a reason. Stevenson’s book has almost no women in it — a couple of maids, a little girl who is trampled, that’s about all. This semester, I’m teaching a course called The Modern Monster, and we’ve talked about why there is a dearth of female characters in the novella. (If you’ve seen the stage or musical versions, you’ll know they both add female characters — predictably, a fiancée and a prostitute.) My hypothesis is that the book is specifically about late Victorian masculinity. Several times, Hyde is presented as symbolically female: he is in part, although not entirely, the female traits inside Jekyll that have to be suppressed for Jekyll to be a proper Victorian man.

Diana Hyde: Diana is entirely made up as well, and for the same reason. Mary and Diana both come out of what is not there, what does not appear, in The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. I’m adding women where there were none — and not a fiancée and prostitute!

Justine Frankenstein: There is no Bride of Frankenstein, not in the novel. Frankenstein never creates a female monster because he’s afraid she would mate with his male monster and their offspring would outcompete humanity. He gathers body parts to create her, starts the process of making a second monster, then disassembles her and throws her body parts into the sea.

Catherine Moreau: Dr. Moreau does create a female monster in The Island of Dr. Moreau. He makes a woman by vivisecting a puma. Guess how many speaking lines she gets? Zero. She does exactly one thing: she kills Moreau. And then she, herself, is killed. Are you starting to see a pattern?

Beatrice Rappaccini: Beatrice is made, and she does get to speak! And then she dies. You can read all about it in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “Rappaccini’s Daughter.” By the way, calling my novel The Strange Case of the Alchemist’s Daughter incorporates two references: to Stevenson’s novel, of course, but also to all the “X’s Daughter” novels. So you see, the references are deliberate, and they’re meant to be at least partly ironic. Although in this case, it really does matter whose daughter Mary is, and the whole issue of being a daughter, what it means to be a daughter, who is a daughter . . . well, the novel should raise some questions about that. But the thing is, all the characters I’m writing about, either they don’t exist or they die. Because that’s what female monsters do, in late nineteenth-century fiction.

That’s why I wrote this book, and that’s why it’s structured the way it is. Some readers aren’t going to like that structure — I already know that. It makes the book a little harder to read, because the central narrative is continually being interrupted. But what is it being interrupted by? Women’s voices. This is a book that, if I’ve done my job right, or at least accomplished what I meant to do, is filled with women’s voices, telling their own stories.

That’s why I rewrote the stories. Because they had no, or little, place in them for female characters. So I decided the stories were wrong, had been told incorrectly. I decided the women had their own stories to tell, their own perspectives. And I wanted to let them speak.

I don’t know how people will respond to what I’ve done — the book is totally out of my hands now. For months, I’ve been working on the sequel, which will take Mary, Diana, Beatrice, Catherine, and Justine deep into the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It’s so much fun to write about late nineteenth-century Vienna and Budapest! Although you have to know pesky things like how to get a passport, the timetables for various trains on the European continent, the exchange rate from pounds to francs to krone — all in the late 1800s! I can’t tell you what the sequel will be called yet, because we haven’t made a final decision about the title, but in my mind I think of it as Monsters Abroad. (No, it definitely won’t be called that.)

So why am I rewriting stories? Because the original versions killed and/or silenced women. I think stories need to be rewritten, just as social institutions like the university, the church, and the workplace need to be reconfigured, to include women and their voices. I listened to the original stories — I read them, I taught them, for goodness’ sake I wrote a whole doctoral dissertation on them. And I heard voices that were not on the page. So I told the stories those voices were telling me . . .

I think that’s pretty such always the way writing happens, whether the voices come from other works of fiction, history, the writer’s own family . . . You hear voices, and then you write down what they’re saying.

(Here is the book cover! Isn’t it beautiful? I can say that because I had nothing to do with its beauty . . . All the credit goes to the artist, Kate Forrester, and the art director, Krista Vossen.)

April 9, 2017

Template Stories

There are certain stories that are written over and over again. I call them “template stories.”

“Snow White” is a template story. So is Dracula. There are many, many versions of “Snow White”: there’s the Grimms’ fairy tale, of course, but also book versions, movie versions . . . And each version is a reinterpretation of earlier versions, a conversation with those versions. Each version can be very different from the others. It’s the same with Dracula. How is this different from non-template stories? Well, take for instance a novel by Edith Wharton. There may be a movie version, but it will be a version of that particular novel–it will attempt to represent that novel, its plot and characters, in their time period. Same with novels by Henry James, Virginia Woolf, most other novelists . . . But “Snow White” gets turned into Snow White and the Huntsman, which is almost nothing like the original fairy tale. Dracula becomes Count von Count from Sesame Street.

Template stories are a little like vampires, in that they live on and on . . . And they keep transforming themselves. Most myths are template stories. So are many fairy tales, but certain modern stories have taken on this particular quality of fairy tales. They have become modern myths. Hamlet is a template story, as is Murder on the Orient Express. Jane Austen novels are not quite template stories, but are in the process of becoming so as we keep rewriting them — Clueless is one example of how an Austen novel can function as a template. Interestingly, Emma is the novel of hers most often turned to other uses.

I’ve been trying to figure out what turns a story into a template story. I think character is central: you need something that serves as a still point around which the rest of the story can pivot. That’s usually a character: Snow White, Dracula, Hamlet, Hercules Poirot, Emma Woodhouse, Sherlock Holmes, Batman. But the still point can also be something else: the House of Usher or Wonderland, for example. The story needs to have something that lives outside the story, and I think also something that reaches deep into our minds, below the level of consciousness. There’s something in these stories that resonates deeply with us — the stories stay with us, or at least certain components of them do. And if we are creative, we feel the compulsion to engage with them, reimagine them. So we get more stories set in Oz, or stories about Tarzan . . .

I don’t think you can know ahead of time what will become a template story. I don’t think you can set out to write one. Although it does, I suspect, take thinking about story a little differently. Instead of thinking about what issue you want to tackle, what style you want to write in, how you want to engage with the contemporary literary world (and yes, there are writers who think about all those things), you want to pursue your subject a little differently. You want to dip down into the deep well, into the dark water of story, and draw something out — you’re not entirely sure what, at first. Or maybe you’re never sure. But it takes going deep into a mysterious place where you’re not sure entirely what you’re doing. Template stories partake of the structure or substance of myth. Mary Poppins is one of the old gods . . .

Template stories are often not the stories we validate culturally: they are not the intellectual novels, ones that win prizes. They come, more often I think, from popular fiction, children’s literature, comic books . . . Perhaps because those sources are closer to the deep well. They are not trying so hard to be relevant. They usually don’t tell us about social conditions at a particular time and place, although literary critics can analyze Peter Pan in the context of the Victorian concept of childhood or J.M. Barrie’s life. But of course they are relevant, in a different way. They keep getting rewritten. Every generation gets its own Peter Pan, its own Miss Marple. King Lear is always fresh and new.

And template stories are not necessarily the best stories in literary terms. Dracula is a fascinating novel, but it’s not as well-written as anything by Thomas Hardy. Nevertheless, Dracula has a continuing life that Bathsheba Everdene does not. There are movies made of Far from the Madding Crowd, but she’s not a muppet. Maybe you don’t want your characters to become muppets? As for me, I would be thrilled to write a story that turned into a template, that turned into something other people wanted to reconfigure in various ways. I think that would be fascinating. But it does mean I think about story in a slightly different way. I try to go deeper, to send my bucket down into the well that exists in my head, and your head, and all of our heads. And sometimes it means I play with other templates, that I retell the old stories in my own way. Not for any particular conscious reason, but because that’s the sort of writer I am. Perhaps it’s fair to say that I am a teller of tales, that what I’m writing are tales of various lengths rather than short stories or novels? Isak Dinesen makes that distinction, and I think she’s certainly writing tales, which is why I like them so much.

At any rate, there are different ways to tell stories . . . and this is one of mine.

(The image is an illustration for “Snow White” by Hanna Boerke.)

April 5, 2017

Mapping the Fairy-Tale Heroine’s Journey: Quotations

Into the Dark Forest: Mapping the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey

by Theodora Goss, PhD

The tales that feature a fairy-tale heroine’s journey:

ATU 310: “Petrosinella” (Basile), “Persinette” (de la Force), “Rapunzel” (Grimm)

ATU 410: “Sun, Moon, and Talia” (Basile), “The Sleeping Beauty in the Woods” (Perrault), “Briar Rose” (Grimm)

ATU 425A: “East o’the Sun and West o’the Moon” (Asbjørnsen and Moe)

ATU 425C: “Beauty and the Beast” (de Beaumont)

ATU 450: “Brother and Sister” (Grimm)

ATU 451: “The Seven Doves” (Basile), “Six Swans” (Grimm), “The Seven Ravens” (Grimm), “The Twelve Brothers” (Grimm)

ATU 480: “The Fairies” (Perrault), “Mother Holle” (Grimm)

ATU 510A: “The Cat Cinderella” (Basile), “Cinderella” (Perrault), “Aschenputtel” (Grimm),

ATU 510A: “Vasilisa the Fair” (Afanas’ev)

ATU 510B: “Donkeyskin” (Perrault), “All Fur” (Grimm), “Catskin” (Jacobs)

ATU 533: “The Goose Girl” (Grimm)

ATU 709: “The Young Slave” (Basile), “Snow White” (Grimm)

The steps of the fairy-tale heroine’s journey as they appear in the tales:

Step 1: The heroine receives gifts.

Meanwhile, the fairies could be heard presenting their gifts to the princess. The youngest declared, “She will be the most beautiful person in the world.” The next added, “She will have the disposition of an angel.” The third decreed, “Her every movement will be marked by gracefulness.” The fourth, “She will dance beyond compare.” The fifth, “She will sing like a nightingale.” The sixth, “She will play every instrument with consummate skill.” — Perrault, “The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood.”

So the old queen packet up a great many precious items and ornaments and goblets and jewels, all made with silver and gold. Indeed, she gave her everything that suited a royal dowery, for she loved her child with all her heart. . . . Then she placed a white handkerchief underneath her finger, let three drops of blood fall on it, and gave it to her daughter. — Grimm, “The Goose Girl”

Step 2: The heroine leaves or loses her home.

When the king’s daughter saw that there was no hope whatsoever of changing her father’s inclinations, she decided to run away. That night, while everyone was asleep, she got up and took three of her precious possessions: a golden ring, a tiny gold spinning wheel, and a little golden reel. She packed the dresses of the sun, the moon, and the stars into a nutshell, put on the cloak of all kinds of fur, and blackened her face and hands with soot. Then she commended herself to God and departed. — Grimm, “All Fur”

She slept on the top floor of the house in the attic on a pathetic straw mattress, while her sisters had bedrooms with parquet floors, the most fashionable style of bed, and mirrors in which they could look at themselves from head to toe. — Perrault, “Cinderella”

Step 3: The heroine enters the dark forest.

The poor child was left alone in the vast forest. She was so frightened that she just stared at all the leaves on the trees and had no idea what to do next. She started running and raced over sharp stones and through thornbushes. Wild beasts darted near her at times, but they did her no harm. She ran as fast as her legs could carry her. When night fell, she saw a little cottage and went inside. — Grimm, “Snow White”

So the next morning, when she woke up, both the Prince and castle were gone, and then she lay on a little green patch, in the midst of a gloomy thick wood, and by her side lay the same bundle of rags she had brought with her from her old home. — Asbjørnsen and Moe, “East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon”

Cinderella thanked him, went to her mother’s grave, and planted a hazel sprig on it. She cried so hard that her tears fell to the ground and watered it. It grew and became a beautiful tree. — Grimm, “Aschenputtel”

Step 4: The heroine finds a temporary home.

The stepmother moved to another house near the edge of the deep forest. In the glade of that forest was a hut, and in the hut lived Baba Yaga. She never allowed anyone to come near her and ate human beings just as if they were chickens. The merchant’s wife hated Vasilisa so much that, at the new house, she would send her stepdaughter into the woods for one thing and another. — Afanas’ev, “Vasilisa the Fair”

Since he now feared that the stepmother might not treat them well and might even harm them, he brought them to a solitary castle in the middle of a forest. It lay so well concealed and the way to it was so hard to find that he himself would not have found it if a wise woman had not give him a ball of yarn with magic powers. — Grimm, “Six Swans”

Step 5: The heroine meets friends and helpers.

The bird tossed down a dress more splendid and radiant than anything she had ever had, and the slippers were covered with gold. — Grimm, “Aschenputtel”

The dwarfs told her: “If you will keep house for us, cook, make the beds, wash, sew, knit, and keep everything neat and tidy, then you can stay with us, and we’ll give you everything you need.” — Grimm, “Snow White”

How did this all come about? Things would have been different without the doll. Without her aid the girl could never have managed all the work. — Afanas’ev, “Vasilisa the Fair”

Step 6: The heroine learns to work.

She left the hut, went into the middle of the forest, climbed a tree, and spent the night there. The next morning she got down, gathered asters, and began to sew. She could not talk to anyone, nor did she have a desire to laugh: she just sat there and concentrated on her work. — Grimm, “The Six Swans”

“Stay with me, and if you do all the housework properly, everything will turn out well for you. Only you must make my bed nicely and carefully and give it a good shaking so the feathers fly. Then it will snow on earth, for I am Mother Holle.” — Grimm, “Mother Holle”

Since she had never seen a distaff or a spindle and was greatly pleased by all that winding, she became so curious that she had the woman come up and, taking the distaff in her hand, she began to draw the thread. But then, by accident, a little piece of flax got under her fingernail and she fell dead to the ground. — Basile, “Sun, Moon, and Talia”

Step 7: The heroine endures temptations and trials.

Snow White felt a craving for the beautiful apple, and when she saw that the peasant woman was eating it, she could no longer resist She put her hand out the window and took the poisoned half. But no sooner had she taken a bite when she fell down on the ground dead. — Grimm, “Snow White”

Vasilisa was the fairest girl in the village, and her stepmother and stepsisters were jealous of her beauty. They tormented her by giving her all kinds of work to do, hoping that she would grow bony from toil and weatherbeaten from exposure to the wind and the sun. And indeed, her life was miserable.” — Afanas’ev, “Vasilisa the Fair”

“No,” the woman said. “That is–there’s only one way in the entire world, but it’s so hard, you won’t be able to free them. You see, you would have to remain silent for seven years and neither speak nor laugh. If you utter but a single word and there is just an hour to go in the seven years, everything will be in vain, and your brothers will be killed by that one word.” — Grimm, “The Twelve Brothers”

Step 8: The heroine dies or is in disguise. (Sometimes this is the true partner.)

No sooner had she touched the spindle than she pricked her hand with its point and fainted. . . . Nothing could revive her. — Grimm, “Briar Rose”

“The hide of the donkey will be the perfect disguise to make you unrecognizable. Conceal yourself carefully under that skin. It is so hideous that no one will ever believe it covers anything beautiful.”

— Perrault, “Donkeyskin”

All that was in the room was gold or silver; but when she had gone to bed, and put out the light, a man came and laid himself alongside her. That was the White Bear, who threw off his beast shape at night; but she had never seen him, for he always came after she had put out the light, and before the day dawned he was up and off again. — Asbjørnsen and Moe, “East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon”

Step 9: The heroine is revived or recognized. (Sometimes she must do this to the true partner.)

She sat down on a stool, took her foot out of the heavy wooden shoe, and put it into the slipper. It fit perfectly. And when she stood up and the prince looked her straight in the face, he recognized the beautiful girl with whom he had danced and exclaimed: “She is the true bride.” — Grimm, “Aschenputtel”

The king could no longer restrain himself. He sprang forward and said, “You can be no one else but my dear wife!”

At that very moment life was restored to her by the grace of God. — Grimm, “Brother and Sister”

How great was her surprise when she discovered that Beast had disappeared and that a young prince more beautiful than the day was bright was lying at her feet, thanking her for having broken the magic spell. — de Beaumont, “Beauty and the Beast”

Step 10: The heroine finds her true partner.

No sooner had her precious tears fallen on the prince’s eyes than he regained his full vision. Now he could see just as clearly as he had seen before, and all this was due to the tenderness of the impassioned Persinette, who took him into her arms. He responded with endless hugs, more than he had ever given her before. — de la Force, “Persinette”

The king’s son, who was returning from a hunt, encountered her, and observing how beautiful she was, he asked her what she was doing there all alone and what had caused her to weep. . . . She told him the entire story, and the king’s son fell in love with her. — Perrault, “The Fairies”

When the sentence had been carried out, the young king married his true bride, and they both reigned over their kingdom in peace and bliss. — Grimm, “The Goose Girl”

Step 11: The heroine enters her permanent home.

When the king saw this, he ran and took Zezolla in his arms and led her to sit on the throne beneath the canopy, where he put the crown on her head and ordered everyone to bow and curtsey to her as their queen. — Basile, “The Cat Cinderella”

The fairy waved her wand, and everyone there was transported to the great hall of the prince’s realm, where the subjects were overjoyed to see him. The prince married Beauty, who lived with him for a long time in perfect happiness, for their marriage was founded on virtue. — de Beaumont, “Beauty and the Beast”

Step 12: The heroine’s tormentors are punished.

“The ogress, enraged at the sight of the king, flung herself headfirst into the vat and was devoured by the repulsive reptiles she had ordered put in there.” — Perrault, “The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood.”

“She deserves nothing better,” said the false bride, “than to be stripped completely naked and put inside a barrel studded with sharp nails. Then two white horses should be harnessed to the barrel and made to drag her through the streets until she’s dead.”

“You’re the woman,” said the king, “and you’ve pronounced your own sentence. All this shall happen to you.” — Grimm, “The Goose Girl”

When the couple went to church, the elder sister was on the right, the younger on the left side: the doves pecked one eye from each one. Later, when they left the church, the elder sister was on the left, the younger on the right. The doves pecked the other eye from each one. And so they were punished for their wickedness and malice with blindness for the rest of their lives. — Grimm, “Aschenputtel”

Sources for these tales:

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm. The Complete Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm. Translated by Jack Zipes, 3rd ed., Bantam, 2003.

Jones, Christine A. and Jennifer Schacker, editors. Marvelous Transformations: An Anthology of Fairy Tales and Contemporary Critical Perspectives. Broadview, 2013.

Tatar, Maria, editor. The Classic Fairy Tales. 2nd ed., Norton, 1999.

Zipes, Jack, editor. The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm. Norton, 2001.

Afanas’ev, Alexandr, editor. Russian Fairy Tales. Translated by Norbert Guterman, Pantheon, 2013.

(This information accompanied a paper originally given at the International Conference for the Fantastic in the Arts 38, in March, 2017. The image is an illustration for “Vasilisa the Fair” by Ivan Bilibin.)

April 3, 2017

Mapping the Fairy-Tale Heroine’s Journey

Into the Dark Forest: Mapping the Fairy-Tale Heroine’s Journey

by Theodora Goss, PhD

Since the publication of Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces and the popularization of his concept of a “hero’s journey,” described on the cover of the New World Library edition as “a universal motif of adventure and transformation that runs through virtually all of the world’s mythic traditions,” attempts have been made to formulate a similarly universal “heroine’s journey.” My paper is not one of those attempts. In it, I make a significantly more modest claim: that if we examine a particular subset of European fairy tales, we find a pattern of narrative elements constituting a “fairy-tale heroine’s journey.” This subset is small but important: it consists of fairy tales that focus on women’s lives, from childhood to marriage, and includes some of the most popular tales that have come down to us from fairy-tale writers and collectors such as Charles Perrault, the Brothers Grimm, Madame de Beaumont, and Alexandr Afanas’ev. When I mention fairy tales I consider part of this category (which are listed in my handout), you will recognize most if not all of their names: these are not tales that have fallen into obscurity. They are still being published in or as children’s books, usually for young girls; some of them have been filmed as Disney animated movies. They are important because for generations, they have presented to girls and women what society considers the natural pattern of a woman’s life. They have done so directly as literature for children, but also indirectly, by influencing adult fiction written for a female audience. This is the pattern of “Cinderella,” “Snow White,” and “Beauty and the Beast”: it is also the pattern of Jane Eyre.

In this paper, I will attempt to describe this narrative pattern, which I have (appropriately for fairy tales or self-help programs), divided into twelve steps. I will show how these steps appear in a variety of tales that fit the fairy-tale heroine’s journey pattern. This pattern functions like the underlying pattern that constitutes an ATU tale type: each element occurs in most, but not necessarily all, of the “fairy-tale heroine’s journey”-type tales, and elements can occur in different order or have different meanings from tale to tale. Some elements appear in certain version of a tale and not others. Nevertheless, I argue that they constitute a recognizable pattern that allows us to identify tales of this type, or perhaps meta-type, since it includes a variety of ATU-type tales. My analysis is influenced by the way in which Francisco Vaz Da Silva identifies symbolic equivalences between versions of the same tale type, as well as Marina Warner’s and Karen Rowe’s descriptions of how female tale tellers have used fairy tales to express their values and concerns.

Here are the narrative elements that I include in the fairy-tale heroine’s journey:

Step 1: The heroine receives gifts.

Step 2: The heroine leaves or loses her home.

Step 3: The heroine enters the dark forest.

Step 4: The heroine finds a temporary home.

Step 5: The heroine meets friends and helpers.

Step 6: The heroine learns to work.

Step 7: The heroine endures temptations and trials.

Step 8: The heroine dies or is in disguise.

Step 9: The heroine is revived or recognized.

Step 10: The heroine finds her true partner.

Step 11: The heroine enters her permanent home.

Step 12: The heroine’s tormentors are punished.

Why do these elements occur in the narrative pattern I have described? I believe they reflect the patterns of women’s lives in the countries where they were told and written down, from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries. Unlike Campbell, who claims that the hero’s journey is a universal mythic pattern, I claim that the fairy-tale heroine’s journey is a culturally and historically specific narrative that has been naturalized and universalized until we have come to accept it as the pattern of women’s lives in the Western world. Although we may not notice it in our cultural narratives, it is part of a social construction of womanhood that has affected women’s lived experiences.

This paper constitutes my first attempt to describe the fairy-tale heroine’s journey in an academic context: appropriately for a theory of popular narrative, it is based on thoughts published in a series of blog posts and then formalized in an article in Faerie Magazine. What I am about to present is both preliminary and provisional, and I hope you will forgive its present defects. It is meant as a point of departure: a way of testing some of the ideas I have developed while reading and teaching fairy tales, often to classes that consist primarily of female college students who are startled and sometimes dismayed to realize the extent to which the tales they read as children have formed their ideas about themselves and their expectations for their futures.

Let’s start by talking about the steps. I don’t have time to discuss how every step works in every story I’ve identified as a fairy-tale heroine’s journey tale, so I’ll try to give some representative examples. Most of these steps occur in most of the tales: often, when a step is missing in one version, it will appear in another.

Step 1: The heroine receives gifts.

The paradigmatic gift-giving scene in heroine’s journey tales occurs in Perrault’s “Sleeping Beauty,” where the fairies invited to her christening give her all the attributes necessary for a young lady at the court of Louis XIV, such as beauty, grace, and the ability to play every musical instrument. However, almost all of these tales include gifts, by which I mean an object or attribute freely given, rather than as a reward or in exchange. In some tales, the givers are fairies. Perrault’s Cinderella receives her coach, gown, and glass slippers from her fairy godmother, although her German counterpart Aschenputtle receives her dress and shoes from the doves that nest in the hazel tree growing on her mother’s grave. Other heroine’s journey tales also feature a gift-giving mother: the Goose Girl receives her mother’s handkerchief with three drops of her own blood, and Vasilisa the Fair receives a doll from her mother that will help her survive both her stepmother’s cruelty and Baba Yaga’s hut. Some fairy tale heroines receive gifts from their fathers: Donkeyskin receives three gowns and the donkey’s skin from her father, and Madame de Beaumont’s Beauty receives the rose she requested. She also receives gifts from the Beast, including a chest of dresses that magically appears at her father’s house. The lassie in “East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon” receives a golden apple, carding comb, and spindle from the three old women she meets while trying to rescue her bear husband–here we have wise women as gift givers, as in the Grimm version of Sleeping Beauty, “Briar Rose.” There are no gifts in “Six Swans” but in its variant “The Seven Ravens,” the sister receives a chicken leg from the stars so she can use the bone to open a glass mountain. The kind girl in “Mother Holle” is rewarded for her industriousness by being showered with gold–that is not a gift. However, in Perraut’s “The Fairies,” another version of the kind and unkind girl tale type, the reward (having flowers and gems drop from her mouth when she speaks) is specifically referred to as a gift.

I’ve talked about the gifts in these tales at some length so you can see both the wide variety among them, and what I argue is an underlying similarity: in almost all these tales, the heroine is given attributes or objects that help her attract friends and helpers, overcome tribulations and trials, and earn her final reward. The gifts come in different ways, from different givers, and at different stages of the journey–they have different meanings. But they are part of a larger pattern–the journey that the fairy-tale heroine must make.

Step 2: The heroine leaves or loses her home.

In all of the tales that fit this pattern, the heroine either leaves her original home or loses it in some way. Snow White and the sister in “Brother and Sister” must leave their homes to escape persecution by a stepmother. Donkeyskin must leave her home because of persecution by her incestuous father. The Goose Girl and the lassie in “East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon” leave their homes to be married, while Beauty leaves her home when her father loses his fortune, then leaves a second home to live with the Beast. Rapunzel is taken away from her home by a fairy or witch, depending on the version. Heroines who do not leave their homes lose them instead: Cinderella must live in her original home, but as a servant to her stepmother and stepsisters. She sleeps in the attic or sits among the ashes of the kitchen hearth. Sleeping Beauty both leaves and loses her home: in the Perrault version, she finds the forbidden spinning wheel in a castle in the country, rather than her family’s palace, and during her hundred-year sleep, she leaves behind her parents as well as the world she grew up in. When she wakes up, another family is on the throne. The common element here is loss: home is left behind or leaves the heroine behind in some fashion.

Step 3: The heroine enters the dark forest.

There is almost always a dark forest. It is usually where the heroine loses her way, but also where she finds friends and helpers and potentially, a place of refuge. Snow White is almost killed by the huntsman in the dark forest, but it is also where she finds safety in the dwarves’ cottage. Heroines who enter the dark forest include Donkeyskin, the Goose Girl, and the girl who speaks gems and flowers in Perrault’s “The Fairies.” Several heroines live in the dark forest: Rapunzel’s tower is located there, and it grows up around Sleeping Beauty’s castle. Vasilisa must enter the dark forest to reach Baba Yaga’s hut, the lassie in “East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon” wakes up there after she loses her bear husband, and the heroine of “Six Swans” begins knitting aster shirts up a tree in the dark forest. The only exceptions to this pattern are found in Grimm’s Aschenputtel and Beauty and the Beast, where it is the father who ventures into the dark forest on his daughter’s behalf: Aschenputtle’s father brings her a hazel branch to put on her mother’s grave, and Beauty’s father brings her the fateful rose.

Step 4: The heroine finds a temporary home.

After they leave or lose their own homes, these heroines find temporary places to live and, often, learn whatever they need to before they move on. These temporary homes include the dwarves’ cottage for Snow White, Rapunzel’s tower, or Mother Holle’s house at the bottom of the well. Vasilisa’s stepmother moves her to a house by the forest, but Baba Yaga’s hut also becomes a temporary home where she gains the power to defeat her oppressors. Sometimes the temporary home is a portion of the original home, like Cinderella’s attic, or a portion of what will become the heroine’s permanent home, like the scullery of the castle where All Fur will eventually rule as queen. Sometimes the temporary home comes after what we believe to be the happy ending: in “Sleeping Beauty,” the princess is taken to a hunting lodge, where her ogre stepmother threatens to eat her and her children, an ending that does not appear in “Briar Rose.” However, the temporary home is never where the heroine ends up: it’s only temporary.

Step 5: The heroine finds friends and helpers.

Friends and helpers for the heroines of these tales include dwarves, doves, a magical doll, the head of a dead horse, and of course assorted fairies. The lassie in “East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon” is helped by three wise women and four winds. In some stories, siblings are friends and helpers, such as the brothers in “Six Swans” or the troublesome brother in “Brother and Sister,” who remains a companion even when he causes so much trouble. In Perrault’s “Sleeping Beauty,” the cook becomes a helper when he saves the princess and her children from the ogre queen. Fairy-tale journey heroines rarely have to solve their problems alone: there is almost always someone to help them or keep them company.

Step 6: The heroine learns to work.

When I started researching the fairy-tale heroine’s journey, I was struck by how often it includes the heroine learning or performing some sort of household task, even when she starts out as a princess. Cinderella must cook and clean for her stepmother and stepsisters. Snow White, who probably never cleaned in her own castle, keeps house for the dwarves. Donkeyskin serves in the kitchen, and the Goose Girl tends her geese. Vasilisa must cook for Baba Yaga, and later she proves her skill as a weaver and seamstress by making a shirt for the Tsar. The girl who went down the well does housework for Mother Holle. Perhaps the most important task is performed by the princess in “Six Swans”: while she is in the dark forest, she sews her brothers six shirts made of asters to break the spell that has turned them into swans.

There are two important exception. While Basile’s Talia wants to spin, she falls under the fairy’s curse as soon as a piece of flax lodges itself in her finger, and of course Sleeping Beauty’s finger is pricked by the needle. Here we have the motif of domestic work, but flipped around: the heroine wants to learn domestic work and cannot. And in Charlotte Rose de la Force’s “Persinette,” the girl in the tower is taught, not housework, but the accomplishments necessary for an upper-class young lady, such as reading, painting, and playing musical instruments.

Now that we’ve gotten to step 6, let’s pause for a moment and consider where these steps are coming from. I contend they represent, not stages in some mythic journey, but fantastical representations of ordinary experiences women had in their lives, during the eras when these tales were being written down. Fairy-tale heroines learn housework and needlework because that is what most European women learned in the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries. Even my mother, who grew up in nineteen-forties and -fifties Hungary, thought these were necessary skills for her daughter. She also told me about the gifts young girls would receive on special holidays or at particularly life stages. Heroines leave or lose their homes because women did leave–lower class girls to become servants or apprentice themselves to trades, upper class girls to schools or convents. What we are seeing, I believe, is the pattern women’s lives took at a particular period in time, turned into fantastical narrative. This includes both physical and emotional life stages. Dark forests did stretch across Europe; however, we have all also entered the dark forest metaphorically. Fairy tales are grounded in ordinary things, such as bread, trees, spinning wheels, and ordinary experiences, such as hunger, death, love. The fairy-tale heroine’s journey tales are no different. Let’s get back to the steps.

Step 7: The heroine endures temptations and trials.

Temptations are what the heroine must resist; trials are what she must undergo or overcome. Snow White is tempted by the corset laces, comb, and apple offered by the pedlar woman, who is her stepmother in disguise. Sleeping Beauty is tempted by the spinning wheel and its dangerous spindle. Rapunzel is tempted by the prince who visits her, and gives in to that temptation. The lassie in “East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon” also gives in to temptation, seeing her bear husband in his human form and thereby losing him. The heroine’s trials include becoming a servant or kitchen maid, having to remain silent while she sews six shirts for her swan brothers, sleeping for a hundred years while princes die in the thorn forest, or marrying what she believes to be a beast. Over and over, it includes the possibility of dying, whether stabbed by a huntsman, burned at the stake, or eaten with sauce Robert. It also includes losing the man she loves or her children.

Step 8: The heroine dies or is in disguise.

This is perhaps the strangest step in the fairy-tale heroine’s journey. Heroines who undergo a literal or symbolic death include Snow White, Sleeping beauty, and the sister in “Six Swans,” who must stay silent for seven years. Some heroines are not dead, but not themselves either: Cinderella, Donkeyskin, and the Goose Girl are in disguise. They have lost their old selves, and cannot regain them until recognized by another. Vasilisa visits Baba Yaga’s hut surrouded by skulls, which is clearly a place of death, and Mother Holle’s county is underground. These are also symbolic deaths. Why must heroines die in these fairy tales? I suggest these deaths represent the rites of passage more common in traditional societies. Arnold Van Gennep showed that such rites often involve a symbolic death: the participant symbolically dies in one social state and is reborn in another. Before our modern era, rites of passage were more common in women’s lives: often, they would mark when a girl became marriageable. In the tales themselves, these deaths and disguises happen when the heroines are adolescents, just old enough for marriage.

However, there is an alternative pattern: in “Beauty and the Beast” and “East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon,” it is the male partner who is in disguise and symbolically dead. It is the heroine’s task to revive and recognize him.

Step 9: The heroine is revived or recognized.

This step is the logical corollary to the previous one. The heroine, or in some cases the hero, must be revived or recognized by another. The one who died must be brought back from the dead. The heroine of “Brother and Sister” must be both revived and recognized: once the king recognizes her as his wife, she miraculously comes to life again. Often the one who revives or recognizes the heroine is her true partner, but Vasilisa is saved by her mother’s blessing, and Mother Holle’s servant returns to the land of the living after having completed her tasks in the underworld.

Step 10: The heroine finds her true partner.

This step is very simple: the heroine marries an upper-class man. It is the inevitable ending of all fairy-tale heroine’s journey stories, and where it does not appear in one version of a particular tale, such as “Mother Holle,” it appears in another. Obviously, this step reflects a time when women were expected to marry, and marriage determined a woman’s material circumstances.

Step 11: The heroine enters her permanent home.

At the end of the fairy tale, the heroine finds the home she will remain in “happily ever after.” This is a place where she is no longer in danger, whether from ogres or wicked stepmothers. It is usually a castle.

Step 12: The heroine’s tormentor is punished.

Here we come to a litany of horrors. Stepmothers are forced to dance themselves to death in red-hot iron shoes. Stepsisters have their eyes pecked out. Sisters are turned into living stone statues. False servants are put in a barrel filled with nails and dragged along the street. Curiously, incestuous fathers and unfaithful kings are forgiven. It is the women who are punished, for what I would call the crime of being women in the wrong way. They are examples of what the heroines should not become. The fairy-tale heroine’s journey is both aspirational and disciplinary. It is built on the actual patterns of women’s lives, but also creates a pattern those lives should follow. Karen Rowe has described the all-female veillés that took place in certain parts of France–gatherings of women with their marriageable daughters “in which both generations carded wool, spun, knit, or stitched, thus enacting age-old female rituals. . . . Within the shared esprit of these late-evening communes, women not only practices their domestic crafts, they also fulfilled their roles as transmitters of culture” (Rowe 404). These are the sorts of spaces in which women gathered to transmit, often to a younger generation, cultural ideas and expectations about the patterns of women’s lives. As Marina Warner points out, “although male writers and collectors have dominated the production and dissemination of popular wonder tales, they often pass on women’s stories from intimate or domestic milieux” (Warner 408) such as the veillé.

Let me anticipate one response to the narrative pattern I have described: “Isn’t that the pattern of every fairy tale about women?” The answer, perhaps surprisingly, is no. It’s simply the pattern of the tales with which we are most familiar. When I searched among the fairy tale collections in my library, trying to find tales that fit the fairy-tale heroine’s journey pattern, I found the twelve listed on my handout. I suspect I could find more, but they are not particularly common among the hundreds of tales collected by folklorists such as the Grimms. And there are certainly tales about female characters that do not fit this pattern, such as “Tatterhood” and “Maid Maleen.” But the tales I’ve discussed have given us five Disney movies, and the pattern itself has given us a legacy that endures in writing for women. As I mentioned, Jane Eyre fits the pattern of the fairy-tale heroine’s journey, not because it’s some sort of universal pattern, but because Charlotte Brontë was consciously drawing on certain fairy tales, including “Cinderella” and “Beauty and the Beast.” If we had time, I could go through Jane Eyre and show how elements of its plot match the pattern I have identified, although the moor on which Jane wanders substitutes for the dark forest. Perhaps that is a topic for another paper. The legacy of Jane Eyre, and novels that share its plot structure, is a romance narrative that still effects how women think about themselves, their possibilities, and their positions in the world.

If it sounds as though I’m critical of the fairy-tale heroine’s journey, I am — and I’m not. It reflects the patterns of women’s lives over hundreds of years, and still affects the patterns of our own lives. It can be used to advance an agenda of domestication, as in Disney’s animated Snow White, or offer women their own quests, and their own possibilities for heroism. It’s also important to remember that this is only one narrative pattern found in stories about women: there are others, and perhaps some of them also deserve their own Disney movies.

Works Cited

Rowe, Karen E. “To Spin a Yarn: The Female Voice in Folklore and Fairytale.” The Classic Fairy Tales, edited by Maria Tatar, Norton, 2nd ed., 2017, pp. 393-405.

Warner, Marina. “The Old Wive’s Tale.” The Classic Fairy Tales, edited by Maria Tatar, Norton, 2nd ed., 2017, pp. 405-14.

(This paper was originally give at the International Conference for the Fantastic in the Arts 38, in March, 2017. The image is an illustration for “Catskin” by Arthur Rackham.)

March 12, 2017

Taking it Slow

Do you remember card catalogs?

Research in them was slow and clunky, but you learned how to do it in elementary or middle school, and then you knew how to do it ever after. I was thinking about card catalogs recently because my university updated its online catalog over the winter break, and when I came back to teach spring classes, I had to learn how to use it all over again. It wasn’t a terrible process — I could, at least, learn to use it well enough to teach students, relatively quickly. But I had just gotten used to the last set of updates, and I’m sure there’s another set coming. Indeed, we seem to be in the midst of a continual set of updates, at this point . . . recently, a page was updated in the middle of the class I was teaching, and my students had to figure out how to get access to a document, trying different URLs in the middle of class. This is the sort of thing we seem to live with now, a world in which we are always trying to figure out how to find or do something, because it’s changed since the last time.

My computer and cell phone are the same way: they are continually updating, and sometimes the updates don’t make a difference, but sometimes I have to figure out how to do something all over again in the new system. One could argue that this is good for us, that we are learning to be nimble, to think on our feet. Except that most of the time these updates are pointless. They do not make the systems any better or easier to use. At this point, if I want to do academic research, I don’t start with my university’s library catalog because the algorithm isn’t very good. I can get better results from JStor or even Google Scholar.

I’m not nostalgic for card catalogs, but I am nostalgic for an earlier version of the university’s online catalog, which worked so well — so much better than the current system! It seems to me that the systems we had in the earlier days of technology were more intuitive, easier to use. They really did help simplify our daily lives. Remember when ATMs were genius? They still are. But somehow or other, so many things have gotten complicated beyond usefulness. I love my iPhone, but I barely ever type on it because the keyboard is not worthy of the name. I still miss the keyboard on my old Blackberry. Now that, you could type on. And speaking of typing, I certainly don’t miss the days of typewriters, but for writing, I still use WordPerfect, which no one else uses anymore. It’s the perfect system for a writer, or at least the type of writer I am. It allows me perfect control over the manuscript, whereas with MS Word, half the time I don’t know what a particular code is doing. I’m not convinced that my students, who use MS Word, do either.

I love technology, but I love technology that makes sense and does its job. And somehow, we’ve pushed so much of our technology past some invisible point of usefulness, where it’s more of a headache to use than not. I barely ever call customer service anymore, because I know that I’ll end up in a briar patch of computerized options. If I need information from my bank, I walk into a bank branch and talk to an actual person. I have a credit card I keep and use specifically because when I call, the voice that answers belongs to a person. It’s such a luxury, nowadays, not having to talk to a computer . . .

Perhaps I’m a modern Luddite. I have nothing against textile mills, but I hate, with cordial passion, the checkout machines at the drug store that always break down when I try to use them, or the reimbursement system all universities seem to use now — it can take longer uploading the information to be reimbursed for the doughnuts at a meeting than you spent in the meeting. Recently, a vendor asked me to use a new system to pay him, and while I wanted to accommodate his preferences, there I was entering my information into yet another new system. I would much rather have written him a check. Remember checks? They’re so easy, and they haven’t changed since I was a child . . .

Here’s what I would say, as a modern Luddite (emphasis on the modern). Some technology helps us. A lot of technology doesn’t. Take what you find useful and use it. What you don’t find useful, avoid as much as possible. It will simply clutter your life, and there’s no reason to upgrade unless you absolutely have to. Choose what serves your interests and passions, reject what doesn’t. Yes, our modern lives will force us into using technology we hate or that wastes time, like when you check into your flight on your home computer, but then at the airport you effectively have to check in again because you have a bag, and then you have to drop off the bag, which is actually a third check-in. But . . . control it as much as you can. Get off the hamster wheel. You are not an hamster.

Take it slow, or as slowly as you want to. I have an iPhone and a laptop. I do not have a smart anything else, except my daughter, who is very smart indeed. I don’t even have a television or microwave . . . But I do have a tea kettle, a sewing machine. I never got an e-reader. I have lots and lots of books. I type my novels, but before that, I write them out by hand. (Yes, really. My antique WordPerfect program is supplemented, and indeed preceded, by an even more antique pen.) I like writing in notebooks, and when it’s not convenient to pay online, I write a check. I still get my tax information on paper, because paper. It feels like something, as opposed to information humming across wires. I like to see things, touch things — even tax forms.

Choose the speed at which you want to live, is what I’m saying. Sometimes we innovate in ways that are not actually useful, and then it’s up to us individually to say, no, not that. That’s a waste of time. After all, if I wanted to learn something complicated and time-consuming, it would not be the university’s online reimbursement system. It would be playing the piano, or knitting lace, or painting in watercolors — something real, solid, slow, and worth my time.

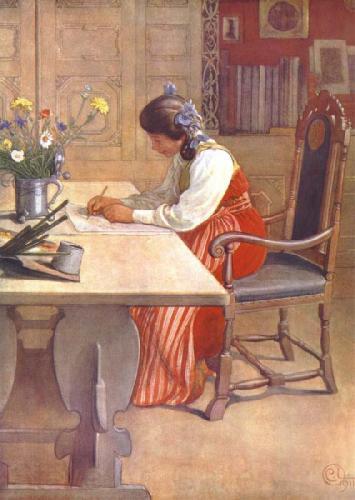

(The painting is Hilda by Carl Larsson.)

March 7, 2017

Writing in Troubled Times

The truth is that I haven’t felt much like blogging lately. I haven’t felt much like going on Facebook, or Twitter, or anything electronic. I’m forcing myself to write this post now . . . Why? I suppose because I’ve been feeling a bit invisible, as though if I don’t keep touch with the larger world out there, I might disappear. Not really, of course. I’m still a corporeal, very real person. I still wake up in the morning, eat, work. Sleep, sometimes. But I feel as though I do lose something, not being in touch.

It hasn’t been much fun to be in touch, lately. It hasn’t been much fun to look online, see the news, worry worry worry about where the world is going.

I realized this was a serious problem when I did not write any poems, not one, in January. I had promised myself that I would try to write poetry regularly, several times a month. That was why I started a poetry blog. It was incentive: I could write a poem, post it, and right away people could see it. I could get some sort of reaction. But January, nothing.

And now, just now, I realized I hadn’t written a blog post in February, not one. Even though I’ve been promising myself that I will start blogging more, particularly now that Facebook and Twitter are so much less fun. Facebook reaches the same twenty people over and over. Twitter is all depressing political news.

I’ve never found it this hard to write before. Oh, I’m writing . . . I have a book due, and I work on that! I’m working on it as fast and hard as I can. But I’ve always found it easy to write, and to write all sorts of things. Now, all I want to do is work on the book, which allows me to go in deep, to disappear into another time and place, to spend time being my characters rather than myself. All I want to do is escape into my own writing. Not communicate.

Perhaps the problem is, I don’t feel as though I have any particular wisdom to offer.

The sorts of problems I see in the news, I can’t fix, and have no fix for. I’m not the right person to tell you, call your congressman. Yes, call your congressman, but what I write about, what I think about, are deeper systems of values. I write about trees, and rocks, and birds. I write about fairy tales. I write about schools for witches. My writing is about what we should value, about the deeper magic of life. Not political positions, or not immediate ones, although I think politics infuses my writing. How could it not, when I was born behind the Berlin Wall, when my parents lived through 1956 in Hungary, when my grandparents lived through World War II? It’s always there . . . but I have little of value to say on current legislation.

So what do I add to the discourse? I’m not sure.

It’s incredibly facile to say, as some have said, that troubled times result in great art. Troubled times are as difficult for artists as for everyone else. They may result in some great works: great poems, great novels, great paintings. They also result in artists jailed, or prevented from traveling, or simply too poor to pursue the visions they’ve been given. I’m not any of those things — I have an incredible amount of freedom. Still, I find myself disheartened.

I suppose what I’ll have to do is simply force myself. I’ve always found that we cannot control how we feel, but we can control how we act. We can force ourselves to sit down, to stay at the page, to type the words, as I am typing them now. It seems to me that we are living in a cruel time, a time of wilful blindness, a time when so many of our leaders hold values that will result in illness, ignorance, death. In the destruction of the precious environment we live in. And not just our leaders — people all over the world who are greedy, unbelievably greedy. Who simply do not care that their wealth is built on the suffering of others.

I don’t get it.

I don’t know, maybe getting it is not my job. Maybe my job is simply to do the work I’ve been given, which is to teach, to write, to do the best I can, create the best I can, under the circumstances. And, when I don’t want to do it, force myself to, as I am forcing myself to write this now.

Here’s what I can say: Underneath it all, there is a ground to stand on, and that ground is a real system of values. Those values are caring for our world, compassion for our fellow inhabitants of it, love of beauty. Rejection of cruelty. Rejection of treating others as less than they are. Rejection of the idea that you must own and control in order to be happy. Celebration of creativity, which is the path to joy. Yes, that is more complicated in practice than in theory — isn’t everything?

In the end, all you can do is walk your own path, do your own work. My work, I’m pretty sure, is writing. So, onward . . .

(The image is Woman and Vase with Flowers by A.C.W. Duncan.)

January 19, 2017

The Politics of Narrative Patterns

There are all sorts of reasons the American election went the way it did, but I think one of them, and perhaps quite an important one, was the way in which our thinking is determined by narrative patterns. What do I mean by narrative patterns? I mean that in narratives, in stories, there are underlying patterns we are familiar with. They recur from story to story: stories are often variations on these patterns. When we encounter these patterns, we feel fulfilled, comfortable — we recognize them, we like to read about them. We like variation, but only a certain amount of variation. Too much variation makes us feel unsatisfied, as though somehow the story is written “wrong.”

Let me give you an example. One narrative pattern is of the couple that dislikes each other but is destined to be together. We can call it the Pride and Prejudice pattern. As soon as we see the bickering but attractive couple on screen, we know the man and woman (it is usually a man and woman) are going to get together. We just don’t know how, or how long it will take. We willingly wait — the length of a book, a television season — for the pattern to be fulfilled. The pleasure is in watching the slow fulfillment of the pattern. But what if the woman decides it’s taking too long, that she would really rather be dating someone else? And then does date him, and then marries him and doesn’t regret it, but settles down happily to have children, grow old with her new and non-destined partner? That breaks the pattern. And at some deep level, a breaking of the pattern is upsetting to us. We might think that the writer isn’t doing it right, the television show has “jumped the shark.” We might feel cheated — after all, destined lovers are supposed to either get married or die for love. We don’t really want them to have any other ending.

Or what if the young hero, having been chosen by the wise old man (Gandalf, Obi-Wan Kenobi), goes on his destined quest, decides he’s tired of being cold and tired and in peril all the time, and just goes home to become a farmer, or an accountant? That’s not a story at all! you might tell me. Well, no, not if we define a story in a certain way — and we do, don’t we? What if instead of oppressing Cinderella, her stepsisters act like ordinary stepsisters, have perfectly ordinary sibling rivalries but nothing that goes so far as relegating anyone to be a servant, sleep by the stove, cover herself in ashes . . . That’s not a story. No, because we define stories in terms of narrative patterns.

Really, of course, anything can be a story. I looked up the word online, to find the most commonly accepted meanings. Here are a few: “an account of imaginary or real people and events told for entertainment,” “a report of an item of news in a newspaper, magazine, or news broadcast,” “a piece of gossip; a rumor.” None of those things have to fit a particular pattern. But that’s not really how we use the term, not when we say Tell me a story. No, then we mean “a plot or story line.” We want to hear about the destined lovers who find each other through hardship or finally recognize each other despite their own pride and prejudice. We want to hear about the hero chosen for a difficult quest who finally, against all odds, fulfills it and his destiny. We want to hear that Cinderella, poor and oppressed, fits the shoe and marries the prince. That’s what we mean by stories, and good stories. These narrative patterns are not unique to fairy tales, or genre fiction — they are everywhere, and what we call realism is as driven by them as any other kind of fiction.

There are writers who have claimed there is only one narrative pattern (for example, Joseph Campbell writing about the hero’s journey). That’s wrong. There are writers who have claimed there are two, or three, or twelve . . . No, there are many narrative patterns, and some are in the process of dying while others are being born. And they are not universal but deeply inflected by culture. The young man who must renounce his earthly love to go on a holy quest disappeared some time ago in our culture, and when we read it now, it sounds funny — like, why give up romantic love for the Holy Grail? That’s because we still value romantic love. The Holy Grail, not so much. However, many of our narrative patterns are thousands of years old. Each age dresses the pattern up in its own clothes, but the pattern persists. A civilized woman can still tame the wild man of the woods, as in the Epic of Gilgamesh, although nowadays the pattern might reverse itself and the woodsy man in a plaid shirt will likely help the woman convinced all she wants is to become a partner in her New York law firm understand that really, she wants to go live in the woods and write poetry, because that’s her deepest authentic self. The pattern persists . . .

These patterns are important because they are woven deeply in us, from the moment we are born to the moment we die, through the stories told to us — by our mothers, our teachers, our media. They weave us into our culture, and they weave us, ourselves — we are made of stories. We experience these patterns as truths and expect to live our lives by them. If we feel as though we are Cinderella, we expect to marry the prince, eventually. And then, if we don’t get our prince, we are often disappointed . . . One reason these patterns are so useful is that they are cognitive shortcuts. If we can understand the world through patterns, we don’t have to think as much or as hard. In the medieval era, accepting the story that the king was ordained by God and could do whatever he wished was a useful cognitive shortcut — if you did not accept it, you had to think so much harder, and for yourself, outside the pattern. You had to become a radical.

Why am I linking the idea of narrative pattern to politics? Because, while there are many reasons the election went the way it did, one reason, I believe, has to do with narrative patterns. People did not get so excited by Barack Obama, when he first ran, because of his policies. No, he was the young hero who had overcome adversity and triumphed. This was his quest, and when he won, it was his Cinderella moment. He fit the patterns, and voters invested energy and belief in him because of that. Of course they were disappointed — how could they not be, to realize he was a human being after all, one who had to do the complicated work of actually governing, of compromising to get anything done? When Donald Trump came along, he fit another narrative pattern: the stranger who rides into town and imposes order, bringing justice to the frontier. That’s a pattern embedded deep in American culture — you can see it in Clint Eastwood movies. It did not hurt him that he was not morally pure, because we do not expect the gunslinger to be morally pure — no, that’s reserved for heroes. And for women. So what pattern did Hillary Clinton fit? That’s the problem right there. We only have two patterns for older women who want political power. One is the Virgin Queen, like Elizabeth I: a woman is fit to wield power if she is willing to give up other aspects of being a woman, such as marital relationships or children. Her sacrifice makes her worthy. Notice how often Clinton was criticized for not having gotten a divorce, usually by women voters. While that criticism may have reflected a number of things, in part it reflected our underlying expectations about women and power — Clinton’s marriage and motherhood took her out of this particular pattern. What was left? The Wicked Queen. We know what she does — she seizes power (illegitimately) for her own gain, to satisfy her own ambition. She kills people or has them killed (this too was a criticism lodged against Clinton). And the Wicked Queen cannot be allowed to gain power — she must be defeated. All of our stories have told us that, from childhood on.

Did these patterns result in election victories or defeats? Who knows. But I think we can see them in the discourse around the election, in the ways candidates were talked about and thought of. There is a sense in which we live out the patterns, we live by the patterns — sometimes we die by the patterns. The patterns give us meaning. But . . . the patterns can change.

Once, I wondered if there was any use in my being a writer. I mean, I didn’t think it would be useless to me — I like being a writer. But I wondered if I, as a writer, would be of any use. To other people, to humanity as a whole. I wondered if I should have become a human rights lawyer, or something like that. But now I think that one of our most important tasks is telling stories, and I am a storyteller. I am a perpetuator and creator of narrative patterns. That means I have an obligation to be aware of the patterns, to wield them in ways that are good, and true, and useful. And I can create new patterns.

Whatever you think of these candidates individually (and I’m not talking about them here as individuals — that’s not my aim), I think it’s clear that we have a problem with the narrative patterns for women. If we want women in positions of power, if indeed that is something we would like to see (and I would), then we need to create new patterns. If we want to see other possibilities for women in general, so they are not stuck in binaries of various sorts, we need to create new patterns. Which is what, in my writing, I am trying to do . . .

(Portrait of Elizabeth I (Armada Portrait), by an unknown painter.)

(Illustration of the Wicked Queen from “Snow White” by Bess Livings.)

January 15, 2017

Miss Fisher and the Female Gaze

I’ve been re-watching Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries, which I like very much — it’s the perfect show to curl up with when you’re thoroughly tired of the modern world we’re living in. You get to go back to another world, equally complicated but in a different way. The show is clever, with twists and turns in every mystery, and has wonderful characters that are deftly developed over time. They have strong, solid, sometimes conflicted relationships. Overall, there’s a lot to like, and I put Miss Fisher in my pantheon of really fun, interesting detectives, up there with Miss Marple, Lord Peter Wimsey, and their ilk. But something particularly struck me, watching the series again. It’s that Miss Fisher is filmed for a female gaze.

I realized this while watching an episode called “Dead Man’s Chest,” in Season 2. The murder weapon, a knife, has been thrown from a pier, so of course someone must search in the water around that pier. We see Miss Fisher and her companion Dot standing on the beach. They are beautifully attired, with flowing dresses and summer hats, and both hold what look like delicious cones of vanilla ice cream in their hands. They are looking at the water, where Detective Inspector Jack Robinson and Constable Hugh Collins are bobbing up and down, rather like dolphins, looking for the murder weapon. Miss Fisher smiles and lowers her sunglasses, presumably to see better. Collins finds the knife, then both men walk out of the water, like in that famous James Bond bathing suit scene with Ursula Andress but in reverse. They are attired in the fetching two-piece men’s bathing suits of the 1920s, which are clinging to their bodies because they are, of course, wet. The camera focuses in a particularly appreciative way on Collins’ chest and arms, and because the top of his bathing suit is white, it becomes translucent when wet. (Don’t even tell me the costume designer didn’t do that on purpose.) Dot towels him off — she is the innocent young woman, not yet aware of what has happened, but Miss Fisher knows. You can tell by her smile, which is, well, knowing. She is perfectly aware of the sexual subtext of the scene, which she has in a sense set up — in the last scene, she asked, with a pointedly innocent look on her face, whether Collins brought his bathing suit. Jack Robinson is also sexualized, but not to the same extent: his bathing suit is dark, his body leaner, more spare. Collins is rather like the ice cream of the scene, in addition to the actual ice cream — he is a delicious dessert, and you realized that Dot has lucked out in a way she doesn’t yet appreciate. But Miss Fisher knows . . . Once out of the water, Collins hands the knife not to Robinson, but to Miss Fisher, who immediately starts analyzing it in the context of the case. End scene.

The perspective of this scene is that of Miss Fisher herself, the heterosexual woman appreciating male bodies. And I find that so interesting, because as I think is clear from years of aesthetic criticism, the heterosexual male gaze has been primary in our culture for a very long time. I’m not interested in abolishing gazes — there is no such thing as no gaze, or a neutral gaze. In art, in film, even in literature where what is seen is entirely imaginary, there is always someone gazing. What I am interested in, though, is the multiplication of gazes. That allows us to see things in different ways, and one reason for Miss Fisher‘s allure, especially among women, is that it allows them to participate in a female gaze (not the only female gaze, but one type).

This is a pattern in the series. In an earlier episode in Season 2, “Death Comes Knocking,” Miss Fisher is in bed with the handsome male assistant of a famous psychic. He is bare-chested — on his chest is a pattern of shrapnel wounds. Miss Fisher is dressed in a beautiful silk gown. The texture of her gown is as sensual, as attractive, as his bare chest. Again we are looking at the scene as though we were Miss Fisher herself — the show turns us all into Miss Fishers, figuring out mysteries, presented with attractive male romantic possibilities. Critics who have written about the show usually focus on its feminist implications, with its liberated female detective who is mature, smart, sexual. The show fairly consistently focuses on issues of women’s equality in the 1920s: driving, work, contraception. But its feminism is deeper than the issues it explores or Miss Fisher herself. It’s woven into every camera shot.

I have to admit, I find it refreshing to watch from the perspective of a female gaze. In the broad tradition of Western art and film, I’m usually watching from a heterosexual male gaze, and I’m used to that — but it does always involve a slight dislocation, as though before truly seeing a painting (of Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, for example), I have to hop to the left. That dislocation can be good — Robert Mappelthorpe’s photographs of male nudes are controversial in part, I think, because they ask us to see from the perspective of a homosexual male gaze, in which the male body is desired in the way female bodies are desired in most of Western art. Western culture is not used to seeing from that perspective. It’s not used to seeing from Miss Fisher’s perspective either. Multiple gazes, as many gazes are we have identifies, which are multitudinous. Let us all learn to see in different ways.

But right now, I’m appreciating Miss Fisher’s gaze. And thinking about what a very clever show this is, to allow me to see in that way.

(The image comes from this interview on NPR, and is credited to Ben King/Acorn.TV.)

December 31, 2016

Learning to Hide

Yesterday, I wrote a poem. I called it “Thumbelina.” It starts like this:

Sometimes I would like to be very small