Theodora Goss's Blog, page 11

June 16, 2016

The Caretakers

The year I was finishing my PhD, I would go to a therapist once a week. I was trying to manage depression, which honestly I think is pretty normal when you’re finishing a PhD. That sort of intensive work, for that long, can be so difficult — you spend your days staring at a screen, trying to make the words and ideas fit together, and then you try to manage the rest of your life at the same time. It was one of the most difficult periods of my life.

Anyway, we talked about my childhood, and one thing she told me was that I was a “caretaker.” I think she said that partly because when I was about twelve years old, I became responsible for taking care not only of myself, but also my little brother. Then later I started babysitting, taking care of other children. Even later, I worked at summer camps. Almost all the jobs I had before going to law school involved taking care of people, in one way or another. But it started with taking care of my little brother.

There is another way of being a caretaker. Somewhere along the way, I was taught to do what we now call emotional work: that is, taking care of the emotional needs of other people. Being not only responsible, but also responsive. This is something a lot of women are taught, of course. I think I learned it because I was raised in a Hungarian family, where you were not only supposed to do the appropriate thing, you were also supposed to feel the appropriate thing. To respond in a way the family thought was appropriate. If you didn’t, you were called an ungrateful American child. Or spoiled. I’ve been called spoiled many times in my life. It’s an interesting word, with an implication of rottenness — if you don’t behave or feel the way you should, you are somehow rotten. I think a lot of people were raised this way, although it was starting to change when I was a child — there was already a sense that children should develop their own sense of self, should learn to stand up for themselves, to create their own boundaries. But that was not part of my upbringing.

So I became a caretaker, and for the most part I remained one. As I lawyer, I took care of clients. Later, as a teacher, I took care of students, and of course I still do. In some ways, it’s like taking care of your little brother. It doesn’t mean giving him everything he wants — it means making sure he heats a healthy dinner, does his homework, goes to bed at the right time. Taking care of students means sometimes giving them things they don’t want, like grades they will be unhappy about — because hopefully they’ll learn from getting a “bad” grade, and do better. It means doing what you believe is best for someone else. It also means listening, intuiting what is not said, caring.

There are good things about being a caretaker: if you’re doing it well, it’s helpful to other people. It makes conversations and interactions better, smoother, easier. This would be a difficult world without nurses and teachers, the types of people who are tasked most directly with caring for someone else. I don’t just mean helping — a surgeon can help you without exchanging a word with you. But nurses do both the emotional and physical work of caring, and that’s really what I’m talking about.

The danger of being a caretaker is that it can consume you. Taking care of other people is one of the most exhausting things you can do, as anyone with small children knows — in that situation, you are responsible for all their needs, physical and emotional. When my daughter started daycare and I went back to work, I was surprised by how much of a relief it was to do that sort of caretaking instead. I loved being with my daughter, but taking care of undergraduates, even sixty of them, was so much easier than taking care of a single two-year-old! That was of course because two-year-old children have no boundaries at all, physical or emotional, whereas teaching creates boundaries as well as connections — the emotional work of interacting with students was much easier.

Most women will know what I’m taking about when I say that caretaking requires emotional work, different amounts depending on the situation. Women are usually taught to do that work as they grow up — they are taught to be caretakers, to make others feel comfortable. They are taught to agree, to be agreeable. To defer when they are told they are wrong, to respond when a response is asked for. They are taught to take care of homes, men, children — and anyone they are in conversation with. If you’re a woman reading this, you probably have an instinct, in conversation, to make sure the person you’re talking to feels comfortable. It’s like putting a pillow under someone’s head. Smoothing a coverlet.

There are good things about that kind of work — another word for it is politeness, and back in the nineteenth century, gentlemen, as well as ladies, were praised for their ability to do it. Somewhere along the way we stopped asking men to do that sort of emotional work, and in male discourse we began to value authenticity. Speaking your mind became a masculine trait, although in women we still valued the ability to soothe, to make comfortable, to take care. That’s changing, although we’re at the point where women are being given the advice to speak up and ask for what they want, then penalized for doing so. It’s a confusing time. The bad thing about it is that, once again, it’s exhausting. Have you ever been in a conversation with someone you disagree with, but that person is also someone you need to treat with respect and politeness — maybe an older relative? Nodding, smiling, saying the soothing thing? Not getting into an argument? And ended up with a splitting headache afterward? Yeah.

What I want to say here is that being a caretaker can be a good thing, but you can’t do it all the time. You lose too much — to much energy, too much of yourself. There are times when you have to draw boundaries, when you have to retreat behind your own walls. You have to take care of yourself. That’s a cliché, but it’s true. There are times when you have to prioritize your own work, your own needs and desires, or you will burn out from trying to provide heat and light to other people. And caretaking can become a place to hide. A substitute for finding your own way, doing your personal work. It’s so easy to say “Everyone else needs me” and ignore yourself. It’s so easy to find emotional fulfillment in meeting everyone else’s needs, at least for a while. Parents sometimes realize that as their children grow older and they think, wait, what was I going to do with my life again?

Caretaking is not enough. Taking care of other people’s needs isn’t enough. Even saving the world isn’t enough if you lose yourself in the process. Although saving the world is a very good thing to do, of course. Society needs caretakers, and honestly we could probably use more of them. Some of the people who are supposed to be caretakers aren’t doing a very good job (politicians especially — anyone remember that they’re supposed to advance the common good?). But don’t let yourself be trapped in being a caretaker. That’s not good for you, or ultimately anyone else.

Take care of yourself too. It’s not new advice, but I think it’s good to be reminded of it every once in a while.

(The painting is by Jessie Wilcox Smith.)

May 22, 2016

The Mythic Arts

When you write a lot for a long time, eventually you learn a very important thing: why you’re writing.

I was thinking about just this issue recently: why do I write? Of course I write because I love writing, the way a dancer loves dancing — it’s a continual dance of the mind, and on days when I don’t write, I feel almost disoriented, not at all myself. I get angry with the world, on days I don’t write. And I write because I want to be read. I want to talk to people, tell them something. I want to communicate.

What I want to tell them is that the world is enchanted, and enchanting. I want them to see what I see: the beauty, the tragedy, the grandeur of this world of ours. Of our lives, even in their smallest moments. I want to show them enchantment. I want them to see the magic. Which is, I suppose, why I write and work in the mythic arts.

I first encountered this word in the work of Terri Windling, who was editing the Journal of Mythic Arts at the time. Unfortunately, the journal itself is no longer being updated regularly, but you can read its wonderful Archives online. What are mythic arts? To explain that, I have to go back a bit.

There are various ways that human beings tell stories. Some of these ways are myths, legends, fairy tales, and history. Myths are stories of the gods. Legends are stories of heroes who have almost-godlike powers. Fairy tales are stories of ordinary people who encounter magic, who venture into or are impacted by fairyland. We separate out history from these categories because it is supposed to be “true,” but as J.R.R. Tolkien points out in “On Fairy-Stories,” history is often more truthy than actually true, and the farther back we go, the more it includes material that comes from myths, legends, and even fairy tales. Modern realistic fiction is fantasy (because all fiction is fantasy — Emma Bovary did not actually exist) that partakes of the truthy quality of history. Realistic fiction is another way we tell stories — a very modern way. The European novel as we know it (novel meaning new, not that old mythic, legendary stuff) dates only to the seventeenth century, although it dates back much farther in Japan.

Something important happened in the nineteenth century: realism and fantasy split off from one another. That split had started at least a century earlier — in Maria Edgeworth’s The Parent’s Assistant, a book for children old enough that Jane Austen would have been familiar with it, she prides herself on not including any fairy stories, which are bad for children in the way sweets are bad for them. It’s already clear from Edgeworth’s introduction that there is reality, and there is fantasy, and never the twain should meet. At least not in the imaginations of children, because they might become confused — they might expect castles and ogres and princes, whereas such things do not exist. So says Maria Edgeworth.

This movement to separate fantasy and reality, but also realism and fairy tale, continued into the nineteenth century, and by the end of the century it was very clear that there were the respectable novel and short story, and the considerably less respectable forms of fairy tale, myth, romance (in the old sense of an adventure story), ghost story, etc. By the twentieth century, they occupied different publishing niches, different shelves in the bookstore. As they still do.

The problem of course is that realism isn’t truth — it’s truthy. And myth and legend and fairy tale also contain truth, in a different way — not by pretending to be true, but by embodying deeper widsom about the world and ourselves. They allow us to tell different kinds of stories that are not accessible to us through realism. For example, The Wind in the Willows contains the very deep, very true, truth that animals have lives apart from our own, consciousnesses we don’t necessarily understand. It’s taken science until — well, now, to understand that truth. We are still exploring it scientifically, but it was there all along in myths and fairy tales. We just stopped listening, and in the meantime, a lot of animals got treated very badly.

Here’s the thing: talking about conservation will not save the badgers of England. If anything will save them, it will be the way people feel about Mr. Badger. We are human beings, and we make decisions based not on logic or rationality, however much we may think we do (deluded as we are about ourselves), but on emotion. And what creates emotion? Story.

If we are to be good, decent human beings, who do not destroy each other or this beautiful world of ours, we must learn that animals can teach us, that trees have wisdom, that kindness and generosity can make you a princess. We must also learn that there are ogres out there, and weapons to fight them. We must learn this in childhood, and we must learn it again (because we are forgetful and must continually be reminded) in adulthood. The mythic arts teach us the deeper truths we must learn, about the world and each other.

And that is the reason I write what I write. I sometimes say that I want to re-enchant the world, but by re-enchant I mean not make enchanted but reveal the enchantment that is already there. I feel as though I see a deeper truth: the world as it is, and as it could be for us if we, in our human folly, did not separate ourselves from the deeply real, did not pave over it with concrete (and the concreteness of our realism).

I’ve been told that what I write is too fantastical, too romantic. But I write about the reality I see. Maybe I just see reality a little differently? What I see is that so much of what we make is truthy, not true. Realism, not reality. We need to reach deeper, go down to the deep wells of story. That is the well I want to draw from.

Down there, the water is cool and dark, and it is the only thing that, ultimately, will quench your thirst. That is why I write.

(I was walking through the forest when I found what I think is an old church baptismal font. There, under the trees, it seemed to symbolize a different sort of baptism . . .)

May 15, 2016

Studying Adaptations

Writing is a craft and an art, as I’ve said many times and in many places.

To learn the craft, you need to study writing. To learn the art, you need to study life. Study it, experience it, live it . . .

But what I want to write about is an aspect of craft. I’m not sure when I started studying adaptations, but I distinctly remember reading The Hunger Games, one week when I had the flu, and then watching the movie almost directly after, specifically to find out how it had been adapted. Someone said (or maybe no one, because it’s one of those internet memes), being a writer means having homework for the rest of your life. That’s essentially true, and writers also set themselves homework. I read books specifically to study what makes them popular, what makes them work . . . or not. Often I learn as much from what I don’t like as from what I do. That week, being too sick to do anything else, I decided to read The Hunger Games. It wasn’t the sort of book I generally love, although I might have when I was younger, but I was impressed by its sheer compulsive power. Despite the fact that I could see how it was being done, how the narrative was put together, I could not put it down. I kept wanting to know what happened next. That in itself is a kind of writerly feat.

Then, still with the flu, I watched the movie version. I was fascinated by the changes that had been made to adapt the novel to a movie. For the most part, they were very effective changes: The Hunger Games and the Harry Potter series both belong to that rare tribe of books that are good in themselves, and are adapted well. Nowadays, I watch adaptations deliberately, trying to learn from them. I find that I can learn a great deal from the choices made by different writers. For example, lately I’ve been watching Grantchester, the BBC mystery series based on the novels by James Runcie. That’s an instance in which I prefer the television adaptation, which is quite different from at least the first novel. And it’s going in a different direction . . . It’s darker and grittier, with more psychological depth. The mysteries are more like puzzles: they fit together in intriguing ways. My brain has always liked puzzle mysteries.

On the other hand, I’ve been dissatisfied with every adaptation I’ve seen of an Agatha Christie mystery. I think the adaptations have gotten her novels completely wrong: they have been convinced that she writes cozies, and that Miss Marple and Hercules Poirot are fundamentally comical figures. But they’re not. In my mind, Poirot resembles Alfred Hitchcock much more than David Suchet, who played him on the BBC series. What we forget about Poirot is that he was a policeman. If you’ve ever met a policeman in real life, you’ll know they have a certain something that people get when they’ve been in positions of power over others, positions from which they wield judgement. Particularly over life and death. When Poirot reveals who he really is, the audience (as well as the criminal) should feel a sense of danger. Christie didn’t write cozies — she wrote perfect, poisonous little poems on death, deconstructions of the British social class system. There is something in her the adaptations, so far, have fundamentally missed.

Recently, I watched another sort of adaptation: the pilot and first season of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Here the pilot could be considered the original, and the first episode of that first season an adaptation of sorts. It was fascinating to see the different choices the director made in the first episode. The biggest change was the actress who played Willow. Looking at the pilot, I could see why the original actress did not work in that part — I’m sure she was very talented, but she seemed to be in a different show from the other characters. I suppose shooting a pilot is like drafting a chapter — once you look back at it, you can see what sticks out, what isn’t going to fit into the novel. You can see what sort of novel it’s going to be.

Give yourself this exercise: Watch a movie or television adaptation of a novel. Notice the following:

1. How has the plot changed, and why? Are those changes effective? Which version do you prefer or find more satisfying?

2. How are the actors bringing the characters to life? What has changed in the characters or how they’re being interpreted?

3. How has the screen version brought the setting to life? What sorts of details have the set designers chosen? How do they inform the story?

4. This isn’t part of the set or part of the characterization — perhaps it’s part of both? But notice how the characters are styled, what they are wearing. What sorts of decisions have been made about costume, and why?

5. Notice the camera. In a screen version, the camera substitutes for what you, as a writer, think of as point of view. What is the camera showing? What is is not showing?

6. What has been cut out? What did the screenwriters and director consider unnecessary?

7. Particularly in a modern version of an older book, how has it been updated? For example, something there only as subtext in the 1940s (a character’s homosexuality, perhaps) will likely be shown in the modern adaptation.

You can learn quite a lot from studying adaptations. It’s yet another tool in your toolkit as a writer, yet another thing you can study as you learn your craft.

And it’s an excellent way to distract yourself when you have the flu . . .

May 7, 2016

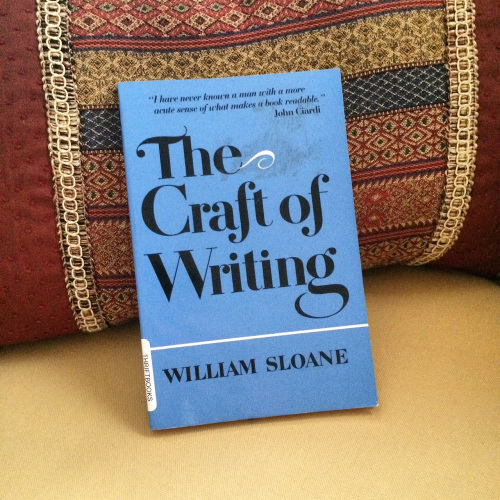

Writing with Density

Recently, I picked up a writing book in a used bookstore. I like to read books about writing, particularly those that focus on writing as a craft, because I find that I always learn something from them. Sometimes I learn what I don’t agree with, when the book doesn’t make sense to me — in which case I give it away again. But sometimes I find a book that is truly valuable to me, and then it becomes a part of my permanent library. That is the case with William Sloane’s The Craft of Writing. I was pretty sure I would like it when I saw that John Ciardi had written the cover blurb — I like Ciardi a great deal, not as a poet necessarily but as a critic and theorist. I like how he approaches writing, looking for a sort of modernist lyrical clarity, which is what I aim for in my own prose.

The Craft of Writing turns out to be an incredibly useful little book — so clear, so sensible. And it contains the best (and honesty, the only) description I have read of something that is central to writing, which is density. Here’s what it says:

“A vital aspect of the fiction-writing process, and most surely of all creative writing processes, is the matter of density. By density I mean richness, substance. It is the core of knowing your materials.

“Density is one of the most difficult aspects of fiction to discuss because it is not a separate element like plot or even characterization. Rather it is a part of everything else. Real density is achieved when the optimum number of things is going on at once, some of them overtly, others by implication.

“Writing is not a matter of a single, simple progression, with each sentence making only one point. Every paragraph, every sentence is related to the entire rest of the book, and if it is not so related it is superfluous. By ‘the entire rest of the book’ I mean what is to come as well as what has gone before. The part of the book already read is stored in the reader’s memory bank, and each new word is added to that storehouse. But in many ways what is being read is an invisible prophesy of what is to come. This is one part of the ingredient of density. There are many others.

“A good piece of fiction is something like the Scot’s definition of the haggis: ‘A deal o’ fine confoosed feeding.’ All parts of each scene are working: characterization of the people portrayed, creation of the physical world of the story, narrative motion, whetting of anticipation, resolution of the mystery, characterization of the author — style inevitable does this — all the dimensions and all at once.”

That’s density, the best description of it I’ve ever read. What I tell students is that every sentence in your story should be doing at least two things, three is better. If it’s only doing one thing (conveying information, for example), it’s insufficiently dense. If a story is written in such single-purpose sentences, it will feel flat, one-dimensional. What you’re aiming for really (Sloane would not have had this vocabulary, I think) is a story that is also a fractal. Each part of the story also contains the pattern of the entire story. But that’s high-order writing, J.S. Salinger’s “For Esmé — with Love and Squalor” level writing. What I’m talking about right now is simply density.

Density is how you establish a feeling of reality in your story. The real world we live in is dense, absolutely filled with stuff, near and far. We are constantly thinking about the past, the future. Just as I sit here writing these lines, I have around me the teddy bear I was given when I was a year old, all the books I have published on a shelf across the room from a shelf of the books I was given as a child, my watch reminding me that I will be going to see the lilacs later this afternoon, a to-do list telling me that I need to finish critiquing two manuscripts this weekend, a rock with the word Believe on it that I bought while I was finishing my doctoral dissertation, and a photograph of my daughter from two years ago as well as a poem she wrote last year. My world is absolutely full, layered. That’s the feeling you want to convey in prose.

The most common difference between the prose of an inexperienced and an experienced writer is density. The experienced writer’s prose will be much more dense. Therefore, it will feel more complex and satisfying.

I tried to think of an example of density in prose — Virginia Woolf immediately came to mind. But perhaps I’ll go with the beginning of “For Esmé — with Love and Squalor,” which is an almost perfect short story. Here’s how it starts:

“Just recently, by air mail, I received an invitation to a wedding that will take place in England on April 18th. It happens to be a wedding I’d give a lot to be able to get to, and when the invitation first arrived, I thought it might just be possible for me to make the trip abroad, by plane, expenses be hanged. However, I’ve since discussed the matter rather extensively with my wife, a breathtakingly levelheaded girl, and we’ve decided against it — for one thing, I’d completely forgotten that my mother-in-law is looking forward to spending the last two weeks in April with us. I really don’t get to see Mother Grencher terribly often, and she’s not getting any younger. She’s fifty-eight. (As she’d be the first to admit.)”

Notice how much is going on in this paragraph, which on the surface is so simple. We know the narrator is male, married, and that he takes a particular attitude toward his wife, who is “breathtakingly levelheaded” — a critical although affectionate appraisal. He’s not in England (America, probably), and he doesn’t have much money. He would very much like to go to this wedding, but expenses are what they are, and anyway his mother-in-law is coming. He likes his mother-in-law well enough, although again we get a sort of amused, sardonic tone (as well as the words “terribly often”–what does that “terribly” imply?). We know at once that this is a man who’s distant emotionally, or has distanced himself. He looks on the world amused, and somewhat passive. What sort of man does that imply? One who has been through trauma. He has discussed the matter rather extensively with his wife — we get the sense that she had a lot to say (breathtakingly — did she have to take a breath in the middle of the discussion? That’s rather the implication, isn’t it? That she did most of the talking, with scarcely a pause to breathe.) And the narrator is not level-headed. Expenses be hanged, he would very much have liked to go to this wedding. Why? Well, in the next paragraph he says,

“All the same, though, wherever I happen to be I don’t think I’m the type that doesn’t even lift a finger to prevent a wedding from flatting. Accordingly, I’ve gone ahead and jotted down a few revealing notes on the bride as I knew her almost six years ago. If my notes should cause the groom, whom I haven’t met, an uneasy moment or two, so much the better. Nobody’s aiming to please, here. More, really, to edify, to instruct.”

He knew the bride. It was six years ago — he is not an old man, his mother-in-law is only fifty-eight. What was his relationship to her? Why will his notes cause the groom an uneasy moment or two? We don’t know — already we are in suspense, because we are put and kept in suspense by things we don’t know. A compelling narrative is simply a continuation of things we don’t know and want to find out.

Do you see how densely Salinger is writing? Really, it takes my breath away. We have place, time, characters, relationships, style, all going at once. Let’s look at one more paragraph:

“In April of 1944, I was among some sixty American enlisted men who took a rather specialized pre-Invasion training course, directed by British Intelligence, in Devon, England. And as I look back, it seems to me that we were fairly unique, the sixty of us, in that there wasn’t one good mixer in the bunch. We were all essentially letter-writing types, and when we spoke to each other out of the line of duty, it was usually to ask somebody if he had any ink he wasn’t using. When we weren’t writing letters or attending classes, each of us went pretty much his own way. Mine usually led me, on clear days, in scenic circles around the countryside. Rainy days, I generally sat in a dry place and read a book, often just an axe length away from a ping-pong table.”

Ok, and now we know where and when we are. We also know that we are being set up for something important, because six years ago our narrator was in a pre-Invasion training course in World War II. You know how Anton Chekhov famously talks about putting the gun on the mantelpiece? Well, in these first three paragraphs Salinger has put two things on a mantelpiece: World War II (that’s a pretty big mantelpiece!), and a woman he still remembers six years later, who is now getting married. In three paragraphs. Bow to the master . . .

What you want to do, if you’re a writer, is practice creating density, because density is one of those craft things: the things you learn, and that you need to practice. It’s like an artist creating perspective (three dimensions on a one-dimensional canvas). It’s like a dancer conveying emotions when all she has is gesture, the movements of her body. It’s an illusion, but fundamental to the art. (In art, the illusion is also true.) One of the best things you can do is read writers who are masters of density and figure out how they do it. The very best of them do it with absolute clarity. Notice that Salinger’s three paragraphs are very simple on the surface — there is not a wasted or confusing word. But they are deep and dense. Read the first few paragraphs of any Virginia Woolf novel and you will see the same thing.

Density is something I work on, something I aspire to. It is the fractal quality that makes black letters on a page come startlingly and vividly to life.

(Here is the book: The Craft of Writing by William Sloane. I recommend it most highly.)

April 30, 2016

Being a Changeling

I’ve always been fascinated by the idea of a changeling.

You know what that is, I’m sure. Although come to think of it, when I ask my students what a changeling is, most of them don’t know. They ask, is it something that changes? And I say, no, the “change” in changeling comes from the same root that gave us “exchange.” A changeling is really an exchangeling.

My friend the Oxford English Dictionary says that the word “change” goes back to the late Latin “cambium,” meaning “exchange.” Among its meanings, it specifies that change is the “substitution of one thing for another; succession of one thing in place of another.” It’s also a round in dancing, “passing from life; death,” and “a place where merchants meet for the transaction of business, an exchange.”

So what is a changeling? “A person or thing (surreptitiously) put in exchange for another,” or more specifically, “A child secretly substituted for another in infancy; esp. a child (usually stupid or ugly) supposed to have been left by fairies in exchange for one stolen.”

A changeling is a child who actually belongs elsewhere, left here in our world. That’s what I felt like, as a child. I wondered what I was doing here, when I obviously belonged somewhere else. I didn’t know where, but somewhere. I could not understand why the other children at my elementary school read books that were not about magic. I mean, how boring, right? I could not understand how the other teenagers in my high school could be so interested in popular culture — the latest movies, the latest music. Although by then I had learned to disguise my own lack of interest. I looked like everyone else, I spoke like everyone else. But I didn’t feel the way I imagined they felt. I was in love with Robin Hood, not Scott Baio. (I bet a lot of people reading this post won’t even remember that ’80s teen heartthrob. But most of you know who Robin Hood is.)

What I’m trying to describe is that sense I had, when I was young (and, confession, still have) of being permanently outside things. Not just that: of belonging someplace else. Part of it, of course, was being an immigrant. I did in fact belong someplace else, another culture. I had lived in that culture long enough to learn its language, to be Hungarian. And then I was taken away, and I had to become something, someone, else. I had to become American. At that time, the land I had come from was hidden behind an Iron Curtain, so it might as well have been fairyland. That’s part of it, I’m sure.

But I’ve met lots of people who feel this way, who are convinced they somehow belong elsewhere, and are still nostalgic for their home country. C.S. Lewis described this feeling, although it converted him to Christianity. I honestly don’t think it has anything to do with religion in particular. What is it then? I think perhaps it’s really the condition of being an artist. Or perhaps of being the sort of person who has an artistic approach to life. You know there is a fairyland, a magical country. You feel it when you create, and see it when you observe. You catch glimpses of it just beyond the reality other people insist is the only one. (I have also met people who don’t feel this way, and who did not at all understand what I was talking about. Sometimes I envy their comfort, how easily they move in this world. It seems to me that being a changeling is a state of continual discomfort.)

What I’m trying to say, I think, is that there are people out there (perhaps you’re one of them) who identify with the story of the changeling, the fairy child left to live in this world. The child who is convinced it belongs elsewhere, but does the best it can here, because that’s what it has, right now. The child who often feels (going back to the definition) stupid or ugly, because it doesn’t quite fit. It thinks, well, perhaps what I have would count as wit and beauty elsewhere? Under a different system of values?

The compensation, for me, of feeling as though I’m a changeling, a sort of perpetual outsider, is art. It feels as though what I do, the stories I tell, the poems I write, all come from someplace else, the place (wherever it is) that is my home. It feels as though I have access to a fairyland, a place where words come from and magic is made. And I see it, too, in little bits and pieces. Fairyland is there: in pools of water, curled up in flowers, as though it were one of those other dimensions described by quantum physicists. It’s as though I can see it interspersed in this world, intersecting it, or behind it but visible as though through a film or veil. Fairyland haunts this world like a ghost. It is always there: what we need are the right eyes.

Recently, I read a book called Writing Wild by Tina Welling. She says something about writers that struck me, although I would apply it to artists in general:

“As writers, we pretend to be among the normal people, all the while living in a way that no one, not even we ourselves, believes is normal at all. What we yearn for is to be acknowledged for who we really are. It may be the reason behind writing in the first place.”

“As writers, we choose a particular way of life. It is our business to see what others may miss; we see life as an exciting wilderness of connections, and we make it our work to discover these connections, mark the path through them, and pass the information on to others. We have noticed that we are after a larger experience of life than most. It doesn’t make us better than others, but it does demand that we be more alert to life. And so it makes us different. We know that, and we like our differentness. Yet it is uncomfortable at times.”

There are things I question about this quotation: for one thing, I don’t think anyone is actually “normal,” or that there is a normal to define ourselves against. There are simply different ways of being abnormal, defined against an imaginary normal that we have somehow made up. But artists may be particularly bad at fitting that imaginary template. They may be particularly incapable of appearing normal. And I do agree with what she says after that: it is our business to see what others may miss, to acknowledge it and represent it. It is our task to understand the connections, to experience and describe life as larger than most people imagine. Not all artists do that, but the ones who do are the ones I most admire, the ones whose work most resonates with me. They are the ones who seem to be looking into another dimension, who see fairyland curled into the trumpet of a flower.

If there is a good thing about being a changeling, it’s that you can see the magic, wherever it hides. And you can write about it, draw it, paint it. Dance it, even. (Change is a dance move, remember?) You can work to re-enchant the world. The world is already enchanted: re-enchanting it means helping other people see the enchantment that is there, and that we often seem to pave over, I think because it makes us uncomfortable. Because it reminds us that what we have, here, now, is only temporary. (Remember that a change is also the passage to death, and fairyland, in old stories, is the land of the dead.) It reminds us that we are ephemeral. But I think we need to be reminded.

Being a changeling means you feel as though you came from somewhere else, and will go somewhere else. It means acknowledging that you are here temporarily. It means seeing the magic in the world, and if you can, representing it for others, so perhaps they will see it as well. And it means being uncomfortable, feeling lost, sometimes feeling alone, because you see things differently than other people seem to see them — unless you can find other changelings to hang out with. But I don’t think I would exchange the way I perceive the world for comfort. It lets me see too much, it makes the world so much more vivid for me. And it allows me to create, which in the end is what I think the fairies left me here to do . . .

April 18, 2016

Shabby and Chic

I’m infinitely grateful to Rachel Ashwell.

Unless you’re interested in decorating, you probably don’t know who she is. She’s the decorator and designer who, in the 1990s, introduced the idea of Shabby Chic. It was very influential at the time, I suppose because everyone was so used to perfectly decorated houses being the standard to which we should all aspire. That was the ideal sold by the decorating magazines, and it mostly still is.

Shabby Chic was the idea that the things you had could be shabby — old, worn, cracked. But if they were beautiful, you could still decorate with them and create something chic — in fact, more chic than you could create with an entire roomful of perfectly-matched furniture. It was based on English country house style, as well as the continental style found in old apartments in Paris, old castles in Tuscany. It was the style of people who had inherited things and didn’t throw them away. The appeal was that this fundamentally aristocratic style could be used by anyone. You didn’t need to inherit things — you could buy them in a thrift store or antique store. If they were a little broken, so much the better.

Dishes didn’t have to match, linens could be crumpled, with maybe a few holes in them. That was perfectly all right. The style was about the beauty of age, use, decay. It promised authenticity. Like the Velveteen Rabbit, things were more real if they had been used and loved.

It appealed to me at once because it was the style I had first known, in my grandmother’s apartment in Budapest. If you wanted to, you could call it Genteel Poverty, but that doesn’t quite have the same ring, does it? My grandmother had it down: the antique linens (because women in her family had embroidered them), the mismatched plates and glasses (because some in the set had broken), the furniture that was a little damaged (because repairing it would have cost too much). Shabby Chic is, of course, a romanticized version of that. But as you know, I’m not against romanticizing things. A human life without romance, without illusion, would not be much fun. Anyway, chic is an illusion. Just ask that consumate sorceress, Coco Chanel.

Ashwell lives in California, although she’s originally from England — her color palette was all wrong for me. But the underlying idea was just right. And it came just when I needed it, when I had very little money to spend on the basic necessities, much less decorating. But I love living in elegant spaces. It makes me feel happier and more human. So here was a decorating style that matched my history, my budget, my basic philosophy of life.

Since then, I’ve applied her philosophy to all sorts of things: the way I buy clothes and books, the way I cook food. I would paraphrase it this way: “I may be thrifty, but I’m determined to be elegant.” I try my best to be both . . .

I thought it would make sense, in this post, to include a few pictures of what my apartment looks like now. It’s in Boston, so I have New England light, which has an undertone of gray. You have to combat that with rich colors.

Let’s start with my living room widows. That table, I bought unfinished and refinished myself. The chairs are from an antique store, although I recovered the seats. The yellow armchair is from Goodwill, the Victorian slipper chair is from an antique store that was selling it cheaply because the fabric is so damaged. Until I have time to have it properly reupholstered, it’s covered with a piece of Waverly fabric in my favorite pattern. The lamp I bought in a hardward store and repainted, then added the shade. I sewed the bobble fringe on myself. And the small black table, I carried a mile from Goodwill to my apartment. It’s a little damaged, but works just fine, as you can see.

This chair in my hall was originally from Goodwill, and it was brown. I painted it, put a piece of fabric over the cushion (that’s another thing that needs to be reupholstered), and added a pillow, also from Goodwill. The small sewing chest contains jewelry, the shelf holds green Indonesian potter collected over many years, on doilies crocheted by my grandmother.

And here is the shelf with the pottery, taken after I had bought my one indulgence, a CD player. I’ve had the shelf for more than ten years, and it’s a little water-damaged. Someday, hopefully, I’ll have a chance to refinish it.

This is my writing desk. Both the desk and chair were bought unfinished, and I refinished them. Everything else came from various places: hardware stores, Staples, art stores where they sell picture frames. The bulletin board came from Staples, but I covered it in fabric and pinned ribbon around the edges.

Across from it is the chest of drawers, found in an antique store. The things on it are from various places, mostly antique and thrift stores, although that lovely mottled vase comes from Etsy. The silver mirror needs to be polished . . . To the left is a bookshelf that holds my murder mysteries. Because there are days when nothing is as satisfying as a good murder. And the painting is by my grandmother.

This is just a collection of cushions on the daybed, which serves as a sofa and a place for guests to sleep. The ones in the back are actually long pillows — I sewed the covers myself. All the other cushions come from discount stores, except the one with the flowers, which is from Goodwill. The scarf behind the daybed is also from Goodwill.

And this is probably the shabbiest but also chic-est thing I own: my bear Dani, who is almost my age. I painted that chair, and the shelf behind him still needs to be repainted — it’s supposed to be cream, not blue. But that will happen this summer, when I have some time.

Honestly, I think the reason I adopted this particular style, aside from its practicality (my dishes are cracked? that’s because they’re chic!) is that everything looks a little worn, which also means well-loved. It’s about having a life that is really, genuinely lived in. Which is of course what I try to do with my life — live in it as thoroughly as I can.

April 10, 2016

Glamour and the Struggle

I don’t remember who said it, except that it was a well-known writer. It flashed by one day as I was scrolling down my Twitter feed: “Don’t glamorize the struggle.” And I thought, yes, I know where that’s coming from. I understand that we should not glamorize the struggles of other people, or artists in general because they’re the ones who usually get glamorized. We should not say that poverty or addiction or mental illness make anyone a better or more authentic artist. And I agree with that.

But something in me rebelled just a little. It said, but if I didn’t glamorize my own struggle, where would I be? With just the struggle, that’s where. So what I want to say is, no, I would never glamorize anyone else’s struggle. But I do often see friends of mine who are writers and artists glamorizing their own struggles, and I think we’re allowed to do that. Because sometimes glamor is all we have, and while it doesn’t substitute for health insurance, it can in fact make the struggle easier to bear. We all get to have our own coping mechanisms, and glamor is one of mine.

What is glamor, anyway? I looked it up in the Oxford English Dictionary, where the first definition is as follows:

“Magic, enchantment, spell; esp. in the phrase to cast the glamour over one.”

The very first reference listed is to the old English ballad “Johnny Faa,” about a countess who runs away with the gypsies: “As soon as they saw her well far’d face, They coost the glamer o’er her.” That reference dates back to 1794, but of course the ballad itself is much older. Johnny Faa casts a glamor over the countess so that she runs away with him, from her castle and count.

In 1830, Sir Walter Scott used the term in that sense, writing, “This species of Witchcraft is well known in Scotland as the glamour, or deceptio visus, and was supposed to be a special attribute of the race of Gipsies.” Sorry, I know, the gypsies are often referred to this way in English and European literature, and yes, it’s had terrible consequences historically. It’s not usually good to be associated with magic, or its little sister, glamor. It often leads to imprisonment or hanging.

Why do I call glamor magic’s little sister? Here is the second definition listed by the OED:

“A magical or fictitious beauty attaching to any person or object; a delusive or alluring charm.”

Glamor carries the connotation of fakery: it’s fictitious, delusive. True magic is the art of changing: if you turn into a hawk by magic, you are a hawk. Glamor is the art of seeming. If you turn into a hawk by glamor, you still can’t fly. It’s a false magic, or at least a lesser magic.

When we glamorize the struggle, we make it seem less hard, but of course really it’s not, right? Although Alfred, Lord Tennyson does write the following lines in Idylls of the King, published in 1859:

“That maiden in the tale, Whom Gwydion made by glamour out of flowers.”

And that was a true glamor, because Blodeuwedd really was made, and became a true woman. So glamor does have some sort of power. To be honest, I think it has significant power because glamor alters our perceptions, and our perceptions do in large part determine our reality, especially the reality of our struggle. Glamor won’t get us health insurance, but it will change how we feel about our lives, whether we are optimistic or pessimistic about them. And for me, honestly, that makes a huge difference.

So when I feel most in the struggle, when I feel most down, most filled with self-doubt, that’s exactly when I tend to glamorize the most. That’s when I put on a long, swooshy skirt and walk through the city as though I owned it: yes, all the streets and the trees and the leaves that have fallen. That’s when I start to tell a story about myself in which I do, indeed, glamorize the struggle. I remind myself that although I did just spend five hours grading undergraduate papers, and I have five more hours to go, I’m still a writer — even if I haven’t touched my manuscript in a week. Because if I didn’t have that, what would I have? Just the struggle. And honestly, without the glamor, without believing in the magic, I might give up the struggle. It’s so much easier to have a quiet, sensible life than to be an artist.

I’m particularly interested in the etymology of the word. Here’s what the OED tells us:

“Etymology: Originally Scots, introduced into the literary language by Scott. A corrupt form of grammar n.; for the sense compare gramarye n. (and French grimoire ), and for the form glomery n.”

A corrupt form of grammar? Grammar, seriously? As in, “That department of the study of a language which deals with its inflexional forms or other means of indicating the relations of words in the sentence, and with the rules for employing these in accordance with established usage; usually including also the department which deals with the phonetic system of the language and the principles of its representation in writing. Often preceded by an adj. designating the language referred to, as in Latin, English, French grammar” (OED). That grammar?

In other words, glamor is related to writing. It’s a form of writing. A grimoire, you may remember, is “A magician’s manual for invoking demons, etc.” (OED). But the OED also says that it comes from the French grammaire, in other words, grammar. And gramarye is defined as either “Grammar; learning in general. Obs.” (OED) or ” Occult learning, magic, necromancy. Revived in literary use by Scott” (OED).

What do we learn from all this? Well first, that it’s all Scott’s fault. Which is a handy formula for pretty much anything: blame Sir Walter Scott. Second, that magic is and has always been intimately related to writing. To spell is both to create a word and to bespell, enchant. Writing is magic in that it alters our perception of realty, and so often perception is, let’s say, 70% of reality. (The other 70% is the part you can’t make go away, like hailstorms. But perception can change how you feel about hailstorms.) Third, that glamor is one of the tools of the writer, and I would say the artist in general. Glamor is actually the essence of what we do: we change not reality, but perception. We are spell-casters, all.

No wonder we glamorize the struggle.

I don’t have a clear answer as to whether or not we should. After all, Emily Dickinson’s and Vincent Van Gogh’s struggles were real and painful. And yet out of them came the most glorious art. What I do know is that I sometimes glamorize my own, and I think that’s all right. If I didn’t, I would be a lot less sane, and I would have a lot less fun. I wouldn’t walk through the city in a swooshy skirt, feeling like the heroine of my own novel, telling a story about myself as much as I tell a story about any of my other characters. I do think it’s important to be honest about the struggle, about how much sheer work goes into the making of art . . . which may or may not be good once you’re done. Which may or may not even be noticed. But it’s also all right, I think, to glamorize at least your own struggle every once in a while. If I didn’t, it would make the struggle so much more of a struggle, you see.

I chose this picture because it’s a very good example of glamorizing the struggle, taken on a day when I was tired and rather despondent because I’d been working so hard and not sleeping enough. After many hours of grading papers, I went out for some necessary grocery shopping and decide to take a short detour through the park. That’s where I took this picture, but as I’m sure you can tell, the underlying reality has been softened, sharpened, by an Instagram filter. And parts of the image have been cropped. The end result is me against dark the water of a forest pool, looking rather mysterious actually, when in reality I just looked tired. But the resulting picture makes me feel like a glamorous writer . . . which means I’m more likely to think of myself that way as well.

April 3, 2016

Creating Rituals

Almost every morning, I do the same thing: wake up, eat breakfast, and then exercise.

Breakfast is almost always the same. A bowl of oatmeal with raisins. A mug of tea with milk. A glass of half orange juice and half fizzy water. And then I exercise for twenty minutes: a combination of yoga, pilates, and stretching. Always the same, every day, although I vary the moves and the order in which I do them, so I’m using different muscles on different days. But that’s my routine, and it doesn’t often vary. It varies most often when I’m traveling, either for teaching or when I’m at a conference or convention. In that case, breakfast might be a cereal bar, but I’ll try to make it a relatively healthy one, and I’ll still do my exercises in a hotel room, going through at least the basic routine.

I have an evening ritual as well. It involves a bubble bath and some reading for pleasure (almost the only time I get to read for pleasure). I also have other rituals: making my bed in the morning, buying flowers each week. I suppose I have rituals of all sorts.

What I want to say in this particular blog post is that rituals are important, because rituals change you. I learned this specifically when I started exercising every day. I’d never been a particularly athletic person. When I was in high school, I was on the tennis team and gymnastics team, although I wasn’t particularly good at either. In college I took dance classes, and those were the most fun . . . I learned that I love to dance. So I took dance classes on and off, mostly ballet because that is one of my great loves. But honestly, I’d never exercised regularly, until one day I created a routine for myself. I would do it several times a week for about forty minutes, and always felt better when I did. At some point, I’m not even sure why, I started doing it every day, but I didn’t have forty minutes every day. I did have twenty minutes every day . . . So the ritual was born. And then something happened that taught me a lesson about the importance of rituals: my body changed. I became leaner, stronger, and more flexible. And eventually (it took several months), I was surprised to realized that I was in the best shape I’d been in my entire life: better than as a teenager, or in my twenties, or thirties.

I know, you’re probably thinking: well, that’s obvious. If you do something every single day, it changes you. But the realization hit me like a hammer (ouch.) I had somehow assumed it was one of those platitudes: you know, the sort of thing you pin up on a bulletin board for inspiration that isn’t actually true. But it’s true. Rituals change you.

They can change you physically, and they can also change your inward perception of yourself. Making my bed every day, buying myself flowers every week, are ways of telling myself that I care about my space, that I take care of myself. They are the outward signs of my own self-care.

The best thing about rituals is that once they’re ingrained, you do them automatically, and it feels wrong to neglect the ritual — when I don’t exercise, it feels as though the world is somehow unbalanced, or I’m unbalanced. I never go more than a day without it. It’s easier to go through the ritual than not, I suppose because we are such creatures of habit. So it matters what kind of habits we develop.

What I’ve tried to do, since learning this lesson, is create productive rituals.

Creating a ritual is not easy. Here’s how you do it:

1. Figure out what the ritual is. Is it to exercise every day? Figure out when you’re going to do it, what specific exercises to do. Put together the routine.

2. Make it as easy as possible. It should take the minimum possible effort to follow the ritual. For example, I exercise right after breakfast, in my pajamas. My pajamas look and feel like yoga clothes. The music is right by the CD player, just waiting for me. Once I’m done, I shower.

3. Do it every day, or at whatever regular interval you’ve decided — once a week, once a month, but honestly I think daily rituals are the strongest. If you miss a day, forgive yourself but do it the next day. Keep trying, keep doing it. Eventually, habit will kick in and the routine will click. When you’ve done it enough, it will become a ritual. At that point, it will be easier to follow the ritual than not.

4. Make sure the ritual is a healthy one, because we can ritualize anything, we human beings. We are such creatures of habit, like animals that walk through a field following the same path every day. If your ritual is to sit in front of the television eating ice cream every night, that ritual will be very hard to stop. Indeed, the best way is not to try and stop, but to create a new ritual.

Does all of this sound terribly boring — exercising every day, eating the same breakfast every day? I don’t find it so. Instead, I find it reassuring. Going through the ritual every morning grounds me, particularly when I’m traveling — when I’m doing so much, speaking to students or an audience, it’s good to have taken the time, first thing in the morning, to go through my personal routine. It was something I did that day for myself. And having rituals frees me up to think about other things — it’s as though I’ve set part of my life on autopilot so I can think about other parts of it more deeply, live those other parts more fully.

So that’s it, really. That’s what I know about rituals, except that as I wrote above, we human beings are creatures of ritual. Think about our religions. We are continually creating rituals for ourselves. Make sure yours are good ones.

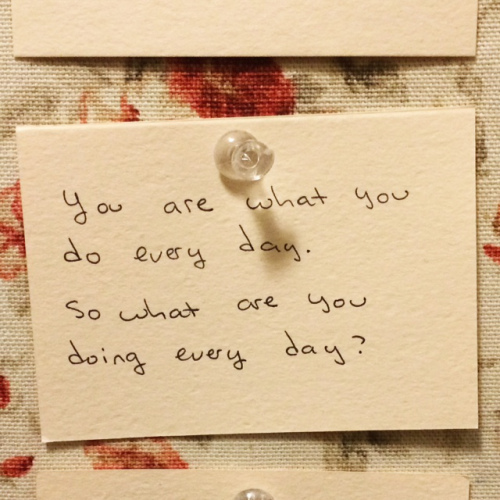

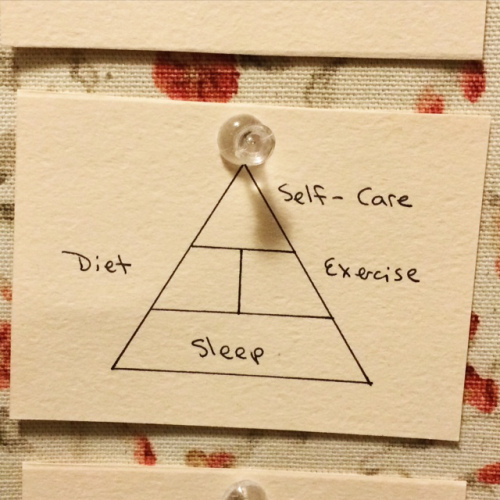

I do, in fact, have inspirational quotations pinned to my bulletin board. Here are two of them:

(Now I just need a ritual for the sleep part . . .)

March 28, 2016

You Lovely People

Oh, you lovely people.

I see you, every day, online and offline. I see you writing books and planting gardens and taking care of children. I see you painting murals and inking comics. You are playing the guitar or a piano. You are taking a ballet class, or learning to tango. You are making breakfast.

You are doing it with hope and grace, and faith in things we don’t know to be true: that tomorrow will come, that the things you are doing are worth doing. What you are doing is both elegant and ordinary, because the ordinary is, when done well, true elegance. And it is extraordinary, because any act of creation is extraordinary. It shows a love of life.

Meanwhile, I see terrible things. Bombs in parks where children are playing. Planes going down filled with teachers and doctors and electricians. With people who a moment ago were watching a romantic comedy.

And yet you are still teaching and doctoring and installing electrical systems. You are still planning and planting parks. You are still making romantic comedies, because love is inherently funny.

I see you and you see each other: all of us, all over the world, doing the work that matters. The work of creation.

I see your spring flowers, and the cakes you baked that didn’t quite turn out right. I see your new outfits. You are celebrating, because you are alive, and that in itself is cause for celebration. You are seeing the world, and it is beautiful, and you are doing your best to save it, whether you are trying to change laws, or sending money to organizations, or lifting a caterpillar off the sidewalk.

And you are noticing it, seeing the world, which is another way for nature to admire herself, because aren’t we her eyes? And aren’t we here in part to see her, to admire her beauty? We are her mirrors. We show her the hawk swooping between city buildings, the cherry blossoms in bloom. Ducks sliding across the water, willows bending like cathedral arches.

You are participating in a great dance.

You are a thread in the most magnificent tapestry ever woven.

You are a note in the song the universe is singing.

You are lovely, and this is what I was thinking as I watched you, all of you, simply being yourselves.

March 13, 2016

The Work of Writing

I keep reading blog posts that basically all make the same point: anyone can find time to write. You’ve probably read them too. The message is, if you want to be a writer, you can find the time. Get up early and write before work. Write on your lunch break. Write on your commute home. Write after everyone else is asleep. If you can write even a hundred words a day, eventually you’ll have a novel.

It’s not a bad message, but it’s aimed toward aspiring writers. And aspiring writers, I would argue, are very different from working writers, who are different, again, from professional writers.

Let me clarify what I mean by those terms. An aspiring writer wants to someday be a writer. He or she has not published anything yet, but is working on it, actively, ardently. Or has published a few things, and is working on publishing more, and more steadily. Most of my MFA students are in that position. A working writer is someone who actually works as a writer, by which I mean writes for money. That money makes up a percentage of his or her income. He or she had to pay taxes on it, which gives him or her headaches. He or she probably has an agent and an accountant, partly to lessen those headaches. But the working writer is not yet a professional writer. The professional writer makes his or her living writing.

Being a professional writer is very, very difficult. I have friends who do it. It’s much easier when you’ve already written a lot of books, at least some of them have been bestsellers, and at least some of them have resulted in movie or television deals. The economics of writing are just too hard: they are stacked against the writer. Anyone who has made it as a professional writer had put in a lot of hard work, and had a lot of lucky breaks. He or she should be commended. Getting to that point is so difficult that writers are told, over and over, often by their own agents, “Don’t quit your day job.” There are no guarantees that you will succeed, and once you do, there are no guarantees that you will continue to do so. I’ve seen writers trying to make it professionally fall behind on rent or put off buying medicine for chronic illnesses because an advance didn’t arrive when it was supposed to.

So what does it mean to be a working writer, which is where I would put myself? February and March have been a particularly busy period for me. Here are the things I’ve had due: First and most importantly, a revision of my novel in response to my editor’s letter and comments. I’m almost done with that. Then, page proofs for a short story that will appear in an anthology, responses to copyedits for a short story that will appear online, an interview for a short story reprint, and page proofs for three poems that will appear in various venues. I’ve had to write three new things: a review of an academic books (done), a conference paper (almost done), an introduction to a short story collection (working on it). Oh, and I had Boskone, where I appeared on panels, gave a reading, met with other writers and my agent. Next weekend, I will have the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts, where I’m giving that paper. I also have to count in there responding to various writing- and publishing-related emails, and sending a panicked email to my accountant because I haven’t even started working on taxes yet. (Although it won’t be too hard, since I’ve already paid estimated taxes for 2015, which means my documents are mostly in order).

Notice that not a single one of those things involves writing several hundred words a day early in the morning, or on my lunch break, or commute, or whatever. And in case it’s not clear, at the same time I’ve been working — teaching classes.

How do I do it? First, I’m very lucky in that my job is more flexible than most. I put in a solid 40-hour week, but I can decide when to put in most (though certainly not all) of those hours. Second, I do the writing work whenever I can. I fill every nook and cranny with it. What I’ve learned is that I’m not happy unless I’m also doing new writing, so amid all of that, I wrote a story. It still needs to be revised, and hopefully I can do that later this month. It’s taken me three months to write, which feels like a very long time for an 8000-word story. But in the meantime, I’ve revised a 100,000-word novel, so there’s that.

By the time you’re a working writer, you’ve already made a commitment to writing as a job, usually a second or third job. That means you have deadlines to meet, people to communicate with, just as you do in any job. It’s no longer just sitting in your bedroom, or in a café, or on a commuter train, and writing. It means you’ve already made a series of choices: for example, I have no idea what the hot new television shows are. I would have no time to follow them. Granted, these two months have been exceptionally busy — it should not be like this all the time, or honestly, I’ll just collapse. You need to get your sleep, you need to make sure you’re still exercising, just as you do with any job. You need to make sure you’re still living, or will go back to living a slightly more normal life as soon as things are less busy. Because a writing career is not a sprint, it’s not even a marathon: it’s just running. One day you decide to start running, and then you keep going. Only people who enjoy the actual running, and are not particularly invested on finish lines, have long-term writing careers. People who want a ribbon or trophy give up quickly.

Will I ever be a professional writer? Maybe someday. I’m certainly not counting on it, and it’s always a good idea to have a day job that you like — or love, because I genuinely love teaching. Maybe in twenty years or so I’ll retire, and by that time I’ll have enough books published that I can work as a professional writer!

My message here isn’t all that different from those blog posts I mentioned: Yes, if you’re an aspiring writer, find time to write, sit down and write, do it if not every day, then as often and regularly as possible. But if you’re lucky and work hard, you will one day transition to being a working writer, and that will take different organizational skills, as well as a particularly intense level of commitment. (You may as well start working on the commitment now.) From over here, I can tell you that I love being a working writer, despite the fact that I often don’t get enough sleep. (I need to work on the sleep — seriously, I can’t stress the importance of making sure you’re not going through the day delirious and hallucinating.) Even when I’ve spend five straight hours, butt in chair, working through copyedits made with Track Changes, which I can tell you is my least favorite activity in the world that doesn’t include actual physical pain. Even then, I love what I’m doing.

And that’s the secret, in the end. You have to love it for its own sake, whether you are an aspiring, working, or professional writer. That’s what we all share in common.

(This is me, on the day I was doing copyedits. Blurry picture, mirror could use a cleaning, and I’m in old jeans and socks. Yup, that’s what it looks like.)