Theodora Goss's Blog, page 13

December 11, 2015

The Gold-Spinner

The Gold-Spinner

by Theodora Goss

There was a little man, I told him.

I gave the little man my rosary,

I gave the little man my ring,

my mother’s ring, which she had given me

as she lay dying. A thin circlet of gold

with a garnet, fit for a commoner.

As I was a commoner, I reminded him.

Nothing magical about me.

Very well, he said. You may go

back to your father’s mill. I have no use

for a miller’s daughter without magic in her fingers.

I’ll keep the three roomfuls of gold.

I walked away from the palace, still barefoot,

still dressed in rags, looking behind me

surreptitiously, afraid he would change his mind.

Afraid he would realize he’d been tricked.

I mean, what kind of name

is Rumpelstiltskin?

But he would have kept me spinning

in a succession of rooms, forever.

I passed my father’s mill without entering,

either to greet or berate. I wanted you to be queen,

he had told me, after I said how could you

betray me like this?

You deserve that, you deserve better

than your mother. What kind of life

did I give her?

No, I wasn’t going back there.

By mid-afternoon I had left the town,

I had forded the river, I had come

to unfamiliar fields. I sat me down

by a hedge on which a few late roses bloomed

and from a thorn I plucked a tuft of wool

left by a passing sheep. I spun,

twisting it between my fingers

as my mother had taught me.

She, too, had the gift.

I coiled the resulting thread

of thin, soft gold

around my wrist. Somewhere along the road

it would buy me bread.

Until then, there were crabapples

and blackberries to share with the birds.

And the road ahead of me,

leading I knew not where, but somewhere different

than the road behind.

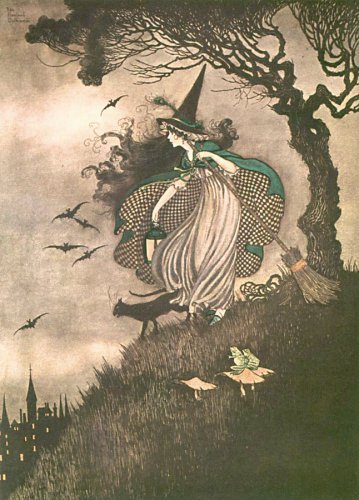

(The illustration is by Anne Andersen. Except in my poem, of course, there is no little man . . .)

The Stepsister’s Tale

The Stepsister’s Tale

by Theodora Goss

It isn’t easy, cutting into your feet.

Years later, when I had become a podiatrist,

I learned the parts of the feet. Did you know your feet

contain a quarter of your bones? Calcaneus, talus, cuboid, navicular.

Lateral, intermediate, and medial cuneiform.

Metatarsals and then the phalanges, proximal, middle, distal.

They’re beautiful on the tongue, these words from a foreign language.

My sister cut into her heels, which are in the hindfoot.

I cut into my big toes, called the halluces.

She cut into flesh and tendon and sinew.

I cut into bone, between the phalanges,

through the interphalangeal joint.

That’s in the forefoot, which bears half the body’s weight.

To this day, both of us walk with a slight limp.

The problem is you do desperate things for love.

We loved her, the woman who wanted us to be perfect:

unblemished skin, waist like a corsetier’s dream,

feet that would fit even the tiniest slipper.

And so we played the aristocratic game

of identify-the-princess.

Sometimes it’s a slipper, sometimes a ring.

Oh mother, love me without asking me to scrape

my fingers like carrots, cut off my heels and toes.

Eventually, she became your favorite daughter,

the cinder-girl, the princess-designate.

She was the best at being perfect, but abuse

will do that to you.

A woman comes into my office, asking me

to cut off her little toes so she can wear

the latest fashion. I sit her down and say

did you know your feet provide the body

with balance, mobility, support?

Come, let me show you a model: here’s the toe,

metatarsal and phalanges. You can see

how elegantly they move, as in a waltz,

surrounded by your blood vessels and nerves,

the ball gown of your soft tissue,

a protective coat of skin, the delicate nail.

Look, underneath, how beautiful you are . . .

(This illustration is by Charles Folkard, for an edition of Grimms’ fairy tales.)

The Witch-Girls

The Witch-Girls

by Theodora Goss

The witch-girls go to school just down the street.

I see them pass each morning with their brooms

and uniforms: black dresses, peaked black hats.

They giggle just like ordinary girls,

except that as they walk, their brindled cats

twine around their ankles. One will stop

and say, “You’ll trip me, Malkin,” scoldingly.

Then Malkin will look up and answer back,

“Carry me then.” The witch-girl will bend down,

scooping the cat into her arms, and perch

him on her shoulder. So the witch-girls pass.

I wish I could be one of them. Alas,

I don’t know how to fly on windy nights

or talk to bats, or brew a magic potion.

Although I think I could be good at witching.

I’d learn to curse and never comb my hair.

I’m pretty good at scaring passers-by

by making goblin faces through the window.

I’d trade white cotton dresses for black wool,

no matter how it itched. I’d fly my broom

up to the witches’ garden on the moon

where they dance nightly, kicking up their heels

with sylphs and fauns and ghouls. At least I think

that’s what they do. I don’t think witches go

to bed at nine, or even make their beds

each morning. No. Instead, they marry toads,

or live alone and read old books. They paint

landscapes in Germany, or climb the Alps,

or sit in Paris cafés eating chocolate

for lunch and maybe dinner. They get drunk

on elderberry cordial, speak with bears

on earnest topics like philology.

I wonder what the witch-girls learn in school?

Geometry that helps them walk through walls,

and how to turn a poem into a spell . . .

I wish that I could go to school with them.

I’d giggle and be wicked too, if they

would only let me.

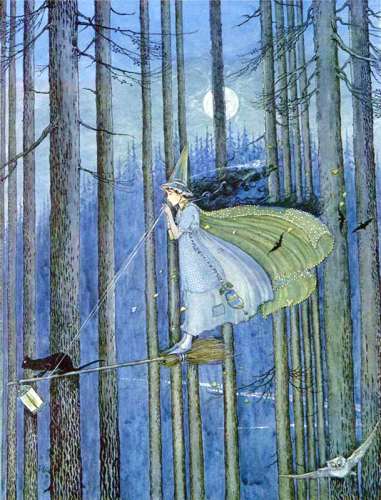

(This image is “The Little Witch” by Ida Rentoul Outhwaite.)

December 10, 2015

Why You Might Be a Witch

Why You Might Be a Witch

by Theodora Goss

Because sometimes you dream of flying

the way you used to.

Because the traffic light always changes for you.

Because when you throw the crusts of your sandwich

to sparrows in the public park, they hop close

and closer, until they perch on your finger

and look at you sideways.

Because as you walk down the street,

the wind plays with the hem of your skirt

so it swings dramatically around your ankles.

Because as you walk, determined and sensible,

your shadow is dancing.

Because a lot of people talk to cats

but for you they answer.

Because the sweetgum trees along the sidewalk

love to show you their leaves, sometimes even tossing

them in front of you, yellow veined red,

brown shot with green and yellow,

like children showing off artwork.

Because when you look up,

the moon is always smiling.

Because sometimes darkness closes around you

and you remind yourself that it’s all right,

you’ve worn this cloak before.

Because in winter you acknowledge

that snow is a blanket as well as a shroud,

and we must all sleep sometimes.

Because in spring you can hear the tinkling bell-sounds

that crocuses make, and the deeper gongs of the tulips.

Because the river waves to you in passing,

and you wave back.

Because even the brownstones of this ancient city

look at you with concern: they want to make sure you’re well.

You belong to them as much as they to you.

Because witches know what they are

and if I asked, do you remember?

You would have to confess that yes,

you do.

(The illustration is by Ida Rentoul Outhwaite.)

How to Make It Snow

How to Make It Snow

by Theodora Goss

First you must fall down the well.

At the bottom of the well

is the country at the bottom of the well.

That is its name, the only one it has.

You have two names, either the beautiful girl

or the kind girl, depending

on what day it is.

At the bottom of the well is a green meadow,

just like in the country you came from

but different. For one thing, the cows can speak.

They say, “Scratch our backs, scratch us

under the chin,” and you do.

The meadow is filled with poppies

and cornflowers. The air is warm,

and the sun is shining.

“Thank you, beautiful girl,” say the cows

and you walk on.

Across the meadow, there is a narrow path

worn by cow hooves. Follow it.

First you come to the oven.

“Take me out, take me out,” cries the bread.

“I’m burning up!” You take it out,

a brown wholemeal loaf. Carry it with you

for the birds — they appear later.

Next you come to the apple tree.

“Shake us down, shake us down,” cry the apples.

“We’re ripe!” So you shake the branches, as though

you were dancing with them.

The apples come tumbling down.

You put three in your pocket.

Now you are at the edge of the forest

and the birds call, “Feed us, feed us!”

You ask the loaf, “May I?”

“This is what I was baked for,” says the loaf.

So you scatter breadcrumbs

and the birds come, sparrows and chickadees,

robins and finches and juncos,

and a nuthatch. They perch on your arms

as you feed them. Absentmindedly,

you whistle as they do.

In the forest, a wild sow approaches.

For the first time you are afraid and step back,

but she says, “My little ones are hungry,

and I smell something sweet.”

You pull the apples out of your pocket.

“May I?” you ask, and the apples reply,

“This is why we fell.”

You kneel while the sow watches protectively,

feeding the apples to her three piglets,

bristle-backed, with tusks just starting to form

but still striped as though someone had marked them

with her fingers. The sow nods and says,

“You are a kind girl.” Then, followed by her progeny,

she disappears into the trees.

You continue alone.

It is getting dark. You have passed through the oaks

and now it is all pines. You are walking on needles.

The light is fading when you come to the cottage.

It looks like the cottage out of a fairy tale:

peaked roof like a witch’s hat, dark green trim,

small-paned windows through which firelight is flickering.

Someone is waiting for you.

You have nothing left, no bread, no apples.

So you knock.

The woman who answers is old, small,

like a doll made of cornhusks.

“You’re hungry,” she says,

“and tired. Come in, my dear.

The soup is almost ready.”

There is a fire, and a cauldron on the fire,

and a chair by the fire, and a cat in the chair,

and you can smell the soup.

“Come on, then,” says the cat, and gets up,

but only to settle again in your lap

once you sit down.

Here are the things you know about the old woman:

she milks the cows, she causes the apples to ripen,

she teaches the birds their songs, she runs her fingers

along the backs of the wild piglets

to put the stripes on them.

Here are the things she knows about you:

everything, also your name.

“What are you called, my dear?” she asks.

“The beautiful girl,” you answer. “Or the kind girl.”

“No,” she says. “From now on, you shall be

she who makes it snow.

Or Holle, for short.”

Holle: it suits you.

“Here’s what I’d like you to do tomorrow morning.

Sweep the floor and dust the shelves,

wash the curtains and wind the clock,

polish the silver. And when that’s done,

shake out my bedspread until the feathers

fly like snowflakes. It’s time for winter.

Can you do that?”

You nod. Yes, of course.

That night you sleep under the cat,

in her attic bedroom.

The next morning, you put on an apron she left for you,

then sweep the floor and dust the shelves,

wash the curtains in a metal basin,

wind the clock and polish the silver. Finally,

you stand on the cottage steps under tall pines

and shake out the old woman’s bedspread.

Snow falls and falls, until

the forest is silent.

“Well done, my dear.” She’s wearing a gray wool coat

and carrying a battered suitcase. “Can you do that again

tomorrow morning, and the day after tomorrow?

I need to visit my sisters, and I’m not sure

when I’ll be back yet.

It takes a responsible girl, but I’ve heard good things

about you from the cows, the bread, the apples,

the birds, even the trees. And the cat likes you.”

“I’ll do my best,” you say.

She kisses you on both cheeks, then rises up, up,

through the trees until she is only a speck

in the colorless sky.

You go back into the cottage.

There is a cat to scratch under the chin,

and books with stories you have never read,

and you haven’t introduced yourself to the clock yet.

Besides, you like your new name.

It’s the right name for a woman

who makes the snow fall.

If you know fairy tales, you’ll recognize this poem as a sort of prequel to the Grimms’ “Frau Holle.” I could not find a source for the illustration, but I’m guessing it’s from an early 20th century edition of Nursery and Household Tales.)

December 6, 2015

Heroine’s Journey: Death and Disguise 2

I was reminded recently of how the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey that I’m describing might be helpful to people: or at least to me.

If you’ve been following this blog, you know that I teach a university class on fairy tales. As I taught some of the most familiar fairy tales, by the Brothers Grimm and Charles Perrault, I realized that they often contained a very specific kind of heroine’s journey. So I started trying to describe it. I’m not a psychoanalyst or anthropologist; I don’t think of this journey as universal, in the way Joseph Campbell described his hero’s journey. Despite my respect for Campbell, I’m dubious of the univeralizing tendency. Among other things, it glosses over important cultural and historical differences. All I claim for the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey is that it’s a narrative structure we see in some fairy tales: the ones I’ve studied so far are European and usually go back to the middle ages. I think of it as a meta-tale type.

You might be familiar with tale types, which is a way that folklorists categorize fairy tales: different fairy tales that share common elements will be categorized as Cinderella-type tales, because there will be the wicked stepmother, the small shoe, even though in one version the Cinderella figure will be given clothes by a fish, in another a cow. Tale types also elide some cultural and historical differences, but at least they are aware of them. They do not try to say there is one Cinderella story underlying all Cinderella stories, or even all stories. They acknowledge that there are many different kinds of stories we can tell, and some of them have certain similarities. They also help us understand the historical development of fairy tales: Cinderella, for example, may originally have been Chinese. But we don’t know for sure, and for me that phrase, “We don’t know for sure,” is the hallmark of good scholarship. A scholar always tells us what she does not know.

So here I am, trying to describe a pattern I see in a number of different tale types. If you want to see the pattern itself, take a look at the “Journey” page on my website, where I list the steps of the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey and link to the various posts I’ve written about it. In my last post, I talked about the step where the heroine dies or is in disguise. Is it one step? Somehow, the death and disguise seem related to me. There’s Snow White in her glass coffin, the Sleeping Beauty in her forest of thorns. Rapunzel is not dead in her tower, but it too seems like Sleeping Beauty’s tower, a place of stasis. Meanwhile you have Cinderella and Donkeyskin in disguise, as servants — they even lose their names. The same sort of thing happens to the Goose-Girl. There is a variant in which the heroine’s true love is the one dead or in disguise: this happens in the “Animal Bridegroom” stories like “Beauty and the Beast” and “East o’ the Sun, West o’ the Moon.” In my last blog post, I connected this period of loss and stasis to the liminal state, the middle stage in a rite of passage. We must pass through a liminal state, a little death, in order to be transformed. It was a very technical sort of blog post.

And then I had a personal experience that highlighted for me why any of this might be important. It’s the end of the university semester; I’m exhausted. For the past few weeks I’ve been working every day, late into the night. During the day, I’ve been planning and teaching my final classes. On days I don’t teach, I’ve been meeting with students for up to five hours a day. In the evenings, and sometimes until the small hours of the morning, I’ve been reading and commenting on papers, answering emails. This weekend, for the first time, I have some free time before the final papers and portfolios come in, at which point I will be grading for a solid week. As you can imagine, I was feeling tired and rather down, getting my work done but dragging myself through the days. I got to Thanksgiving, which is a break for us, and all I wanted to do was watch British murder mysteries or baking competitions, which are surprisingly alike in their underlying narrative structure. And I thought, what is wrong with me? I blamed myself — perhaps I had planned the semester wrong? (No, semesters are like this for every professor who teaches writing.) I tried to push myself, but every time I did, I just got more tired, more despondent.

And then I had a revelation: I’m not in the dark forest. I’m in the glass coffin.

If you’ve read the structure of the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey, you know that there is a stage where the heroine must go through the dark forest. It’s usually fairly early on in the tale. The important thing about the dark forest is that you don’t die there. You’re lost, you’re scared, you’re usually alone, after you get rid of the huntsman who was sent to kill you . . . but you’re not going to die. The dark forest is simply something you have to get through, and it usually represents your fears, your encounter with the darkness in yourself and the world.

The lesson of the dark forest is: keep going.

The stage where you die, where you end up in the glass coffin, is usually a separate stage. (Except in “Sleeping Beauty”: she’s dead and in the dark forest at once. In tale types, and in the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey, there’s always an exception.) The lesson of the glass coffin is that you will be revived. You will eventually wake up. In fairy tales, death is temporary. In this way, I think, fairy tales hark back to a pagan past and a time when life was seasonal, cyclical. The year died and was born again. The people who originally told these tales lived in continual cycles — of the seasons, of life and death, of the pagan or later Christian festivals that marked the stages of the year. Even their daily lives were governed by the rising and setting of the sun in a way ours aren’t. When they became Christian, death was still figured as a rebirth.

The lesson of the glass coffin is: rest now.

What does that mean? It means that sometimes you are tired, and sometimes you are in a state of transformation, and in those times you must accept that you need rest. Don’t keep going. Instead, crawl under the covers. Watch British murder mysteries and baking competitions. This isn’t the time to power through. The journey includes periods when you’re not traveling, and you need to accept that. Sometimes, you won’t be going anywhere for a while. And that’s all right.

So I did: I rested. And afterward I felt better.

It helped me to have a model of the journey, to understand where I was on that journey. Because the journey itself, and this is one of my hypotheses, is based on women’s actual lives. Oh, not the lives we live now: no, it’s based on what women’s lives were like hundreds of years ago. But the underlying structures of those lives, the leaving home, going through dark forests, finding friends and helpers . . . all those fundamental things are still parts of our lives, and learning the patterns can help us identify them in our own lives. They can help us live the lives we live now, consciously and well.

(This illustration is by Louis Rhead. I chose it because the Queen looks so contemplative: here she looks less as though she’s admiring herself in the mirror and more as though she’s asking what it’s all about, anyway.)

December 5, 2015

Why You Might Be a Witch

Why You Might Be a Witch

by Theodora Goss

Because sometimes you dream of flying

the way you used to.

Because the traffic light always changes for you.

Because when you throw the crusts of your sandwich

to sparrows in the public park, they hop close

and closer, until they perch on your finger

and look at you sideways.

Because as you walk down the street,

the wind plays with the hem of your skirt

so it swings dramatically around your ankles.

Because as you walk, determined and sensible,

your shadow is dancing.

Because a lot of people talk to cats

but for you they answer.

Because the sweetgum trees along the sidewalk

love to show you their leaves, sometimes even tossing

them in front of you, yellow veined red,

brown shot with green and yellow,

like children showing off artwork.

Because when you look up,

the moon is always smiling.

Because sometimes darkness closes around you

and you remind yourself that it’s all right,

you’ve worn this cloak before.

Because in winter you acknowledge

that snow is a blanket as well as a shroud,

and we must all sleep sometimes.

Because in spring you can hear the tinkling bell-sounds

that crocuses make, and the deeper gongs of the tulips.

Because the river waves to you in passing,

and you wave back.

Because even the brownstones of this ancient city

look at you with concern: they want to make sure you’re well.

You belong to them as much as they to you.

Because witches know what they are

and if I asked, do you remember?

You would have to confess that yes,

you do.

(The illustration is by Ida Rentoul Outhwaite.)

December 2, 2015

Lady Winter

Lady Winter

by Theodora Goss

My soul said, let us visit Lady Winter.

Why? I responded. Look, the leaves still lie

yellow and red and orange in the gutters.

The geese float on the river. On the sidewalks,

puddles continue to reflect the sky.

My soul said, the branches are bare.

And you can feel it, can’t you, in your bones?

The chill that is a promise of her coming.

The year is growing older. Anyway,

you haven’t seen her in so long: it’s time.

We put on our visiting hats.

I stood admiring myself in the mirror

while my soul stood beside me looking pensive

and pale. Was she a little sick? I wondered.

Lady Winter lives on an ancient street

lined with elms that canker has not touched,

in a tall brownstone with lace curtain panels,

empty window boxes, two stone lions.

We rang the bell and heard it echoing.

A maid opened the door. Her name is Frost.

My lady looked the way she always does:

white hair, a string of pearls, rings on her fingers,

age somewhere between forty and four thousand,

a kind, implacable smile.

She said, my dear, what’s wrong? You don’t look well.

What, me? I’m fine. Perfectly fine, I said.

My soul just shook her head.

My lady has a parlor with a fireplace

in which I’ve never seen a fire. Instead,

it’s filled with decorative branches. Doilies

lie like snowflakes on the tables, bookshelves,

over the backs of armchairs.

She’s always wearing a gray cashmere sweater

and expensive shoes. She must have a closetful.

She usually serves us tea and ladyfingers.

But this time she said, I want you to go to bed.

Frost will take you upstairs, then I’ll come up

to cover you in blankets of felted wool,

comforters stuffed with down from eiderducks

that nest by Norwegian fjords. I’ll read you books

of fairytales about bears and princesses,

and stolen crowns, and castles beneath the sea,

and northern lights.

Grandmothers who grant wishes, talking reindeer,

a village in the clouds.

I’ll talk to you until you fall asleep.

Your soul will sit and watch through the long night.

From time to time she’ll take your temperature

to make sure you’re all right.

So I lay down in Lady Winter’s guest room:

reluctantly, but it looked so inviting,

a bed with draperies and a painted ceiling

from which the moon was hanging

by a silver chain.

My soul sat down beside me.

Don’t worry, she said. There’s plenty for me to do.

Poetry to embroider, plans to knit.

I’ll wake you when the crocuses have broken

through the black soil, when warmth has come again.

Then Lady Winter put her soft, dry hand

like paper on my forehead

and she said

rest now.

(The image is by Elizabeth Sonrel.)

November 28, 2015

Heroine’s Journey: Death and Disguise

At some point during the fairytale heroine’s journey, she dies. Or she’s in disguise: actually, it’s much the same thing.

You remember the fairytale heroine’s journey, right? I haven’t written about it for a while, because I’ve been so busy. But today I thought I would return to it. Here, in case you’ve forgotten, are the steps:

1. The heroine receives gifts.

2. The heroine leaves or loses her home.

3. The heroine enters the dark forest.

4. The heroine finds a temporary home.

5. The heroine meets friends and helpers.

6. The heroine learns to work.

7. The heroine endures temptations and trials.

8. The heroine dies or is in disguise.

9. The heroine is revived or recognized.

10. The heroine finds her true partner.

11. The heroine enters her permanent home.

12. The heroine’s tormentors are punished.

So now we’re on Step 8, and here the strangest thing happens, and it happens in so many fairy tales: the heroine essentially loses herself. Snow White dies from the apple and is laid in her glass coffin. Sleeping Beauty sleeps for a hundred years. Cinderella and Donkeyskin are disfigured by ashes and the donkey’s hide: no one knows who they truly are. The Goose Girl is disguised as a goose girl, of course. In “Six Swans” the heroine must stay silent for seven years. Rapunzel is in her tower, just as Sleeping Beauty is in her forest. Vasilisa is in Baba Yaga’s hut, which is a place of the dead. The heroine is immured, lost to the world in some way. And lost to herself. The exception is “Beauty and the Beast”-type tales, which includes “East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon.” In those tales, it’s the male love interest who dies or sleeps, who is lost. The heroine’s task is to find him, to recognize him — which as we will see is the next step. But in most of the tales I’m familiar with, it’s the heroine herself who dies or is in disguise for a while.

One of my hypotheses is that this pattern is so strong, it gets put onto fairy tales that didn’t originally contain it. So for example, oral versions of “Little Red Riding Hood” did not include Little Red being eaten by the wolf. “Little Red Riding Hood” is not part of this family of tales about a woman’s development, from birth to marriage. But in the Grimm version, we have the disguise: Grandmother is really the wolf. And we have the death: Grandmother and Little Red in the wolf’s belly. The logical outcome would be for Little Red to marry the Hunter, and I bet someone has written or will write that version, because in fairy tales, patterns have a way of playing themselves out.

But anyway, back to our dying, disguised heroines. Why do they die? Why must they lose themselves?

My theory is that fairy tales reflect a mishmash of old stories, customs, rituals . . . and of course history. All sorts of things went into the making of fairy tales. Medieval famines went into them, and myths went into them, and the patterns of ritual went into them. I think that’s partly what we have here. What this death and disguise reminds me of, more than anything else, is a rite of passage. That pattern was described by Arnold Van Gennep in The Rites of Passage, which I read in graduate school. Van Gennep studied rites of passage from all over the world and concluded that they all share a three-part structure: they all have a pre-liminal stage, a liminal stage, and finally a post-liminal stage. So what is “liminal”?

A “limen” is a threshold: it’s the thing you cross over when you step through a door. At least, if you’re doing it in Latin! In a rite of passage, the pre-liminal state is stable: it’s the stage you were at before things changed. The post-liminal stage is also stable. So, for example, in a rite of passage you might change from a boy to a man, or an unmarried girl to a married woman. (I use those examples because they are two of the most common, and yes, rites of passage are usually gendered.) The liminal stage, between them, is unstable. It’s dangerous: to the person undergoing the rite of passage, and to anyone connected to that person. It must be closely supervised, protected by ritual. As traditional societies know, to change is to be in peril, at least for a while. The typical plot of the Victorian novel is this: “a rite of passage goes awry.” Usually the rite of passage is marriage, and poor Jane Eyre is left at the alter in her ritual wedding gown. What she must undergo next is a symbolic death on the moors, sleeping on the earth as though in a grave. I think it’s important that Charlotte Brontë made Jane’s rite of passage not marriage, but communion with the earth, which is described as a great mother.

Back to our fairy tale heroine. It was once common for girls, as well as boys, to go through rites of passage. These tended to disappear over time . . . But the important thing, for understanding fairy tales, is that girls did once go through them, and the central stage of the rite of passage, the liminal stage, often involved a ritual death. Disguise was also a kind of death: young boys would be sent out into the wilderness, where they would ritually become animals. They were dead to the human community. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that just as society was losing so many of its traditional rites of passage, the color of a wedding dress changed. Yes, fashions were following Victoria, and white is the color of innocence, a virginal color . . . but it’s also the color of a shroud. I think that’s why in the West, white has stuck as wedding-dress color. A bride also looks like a corpse. So the girl undergoing a rite of passage is ritually dead, or ritually something other than what she is — she is in disguise.

That’s what we have in fairy tales: a memory, an echo, of the rite of passage.

It makes sense, doesn’t it? If these particular types of tales, the fairytale heroine’s journey tales, were about the progress of a woman’s life, they would include a rite of passage in which she changes from a girl into a woman. That’s exactly what we have in Snow White and Sleeping Beauty. Some scholars have seen these instances of being dead as examples of extreme passivity, but because they occur so frequently in fairy tales, and are not always associated with being passive, I would call them times of transformation. It particularly interests me that they’re often associated with hearths. The Goose Girl must crawl into a hearth and whisper her secrets before she is recognized. Cinderella’s disguise comes from the hearth. Donkeyskin works in a kitchen, next to the hearth. Why a hearth? Well, for one thing, the hearth is a sacred space. It’s where food is cooked, where what is inedible is transformed into the edible. The anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss identified the difference between raw and cooked as the central difference between primitive and civilized. The hearth is the symbol of civilization itself. It was once presided over by the goddess Hestia or Vesta, who is one of the most important goddesses of the classical pantheon. (We tend to forget her, because there aren’t a lot of stories associated with her. But in actual belief and ritual, Vesta was absolutely central. She’s the one to whom the Vestal Virgins owed allegiance, and they kept the sacred fire of Rome itself lit.) The hearth is where transformation happens, and it’s also a tomb. In ancient belief, life was most often seen as a cycle: before things were born, they had to die. The hearth is a symbol of that. And hearths were sometimes used for burials . . .

Is it all starting to make sense? What I haven’t yet touched on is what use we, as modern human beings, can make of this. Perhaps that has to wait for another post. But the important thing is that before she can reach her happy ending, the fairytale heroine has to die or lose herself in some way. Or, in the “Beauty and the Beast” variant I described above, she has to revive or recognize the man she loves. But more on that another time . . .

This painting of Snow White in her coffin is by the Austrian painter Marianne Stokes.

November 26, 2015

The Witch-Girls

The Witch-Girls

by Theodora Goss

The witch-girls go to school just down the street.

I see them pass each morning with their brooms

and uniforms: black dresses, peaked black hats.

They giggle just like ordinary girls,

except that as they walk, their brindled cats

twine around their ankles. One will stop

and say, “You’ll trip me, Malkin,” scoldingly.

Then Malkin will look up and answer back,

“Carry me then.” The witch-girl will bend down,

scooping the cat into her arms, and perch

him on her shoulder. So the witch-girls pass.

I wish I could be one of them. Alas,

I don’t know how to fly on windy nights

or talk to bats, or brew a magic potion.

Although I think I could be good at witching.

I’d learn to curse and never comb my hair.

I’m pretty good at scaring passers-by

by making goblin faces through the window.

I’d trade white cotton dresses for black wool,

no matter how it itched. I’d fly my broom

up to the witches’ garden on the moon

where they dance nightly, kicking up their heels

with sylphs and fauns and ghouls. At least I think

that’s what they do. I don’t think witches go

to bed at nine, or even make their beds

each morning. No. Instead, they marry toads,

or live alone and read old books. They paint

landscapes in Germany, or climb the Alps,

or sit in Paris cafés eating chocolate

for lunch and maybe dinner. They get drunk

on elderberry cordial, speak with bears

on earnest topics like philology.

I wonder what the witch-girls learn in school?

Geometry that helps them walk through walls,

and how to turn a poem into a spell . . .

I wish that I could go to school with them.

I’d giggle and be wicked too, if they

would only let me.

(This image is “The Little Witch” by Ida Rentoul Outhwaite.)