Theodora Goss's Blog, page 14

November 25, 2015

The Gold-Spinner

The Gold-Spinner

by Theodora Goss

There was a little man, I told him.

I gave the little man my rosary,

I gave the little man my ring,

my mother’s ring, which she had given me

as she lay dying. A thin circlet of gold

with a garnet, fit for a commoner.

As I was a commoner, I reminded him.

Nothing magical about me.

Very well, he said. You may go

back to your father’s mill. I have no use

for a miller’s daughter without magic in her fingers.

I’ll keep the three roomfuls of gold.

I walked away from the palace, still barefoot,

still dressed in rags, looking behind me

surreptitiously, afraid he would change his mind.

Afraid he would realize he’d been tricked.

I mean, what kind of name

is Rumpelstiltskin?

But he would have kept me spinning

in a succession of rooms, forever.

I passed my father’s mill without entering,

either to greet or berate. I wanted you to be queen,

he had told me, after I said how could you

betray me like this?

You deserve that, you deserve better

than your mother. What kind of life

did I give her?

No, I wasn’t going back there.

By mid-afternoon I had left the town,

I had forded the river, I had come

to unfamiliar fields. I sat me down

by a hedge on which a few late roses bloomed

and from a thorn I plucked a tuft of wool

left by a passing sheep. I spun,

twisting it between my fingers

as my mother had taught me.

She, too, had the gift.

I coiled the resulting thread

of thin, soft gold

around my wrist. Somewhere along the road

it would buy me bread.

Until then, there were crabapples

and blackberries to share with the birds.

And the road ahead of me,

leading I knew not where, but somewhere different

than the road behind.

(The illustration is by Anne Andersen. Except in my poem, of course, there is no little man . . .)

November 18, 2015

The Stepsister’s Tale

The Stepsister’s Tale

by Theodora Goss

It isn’t easy, cutting into your feet.

Years later, when I had become a podiatrist,

I learned the parts of the feet. Did you know that your feet

contain a quarter of your bones? Calcaneus, talus, cuboid, navicular.

Lateral, intermediate, and medial cuneiform.

Metatarsals and then the phalanges, proximal, middle, distal.

They are beautiful on the tongue, these words from a foreign language.

My sister cut into her heels, which are in the hindfoot.

I cut into my big toes, called the halluces.

She cut into flesh and tendon and sinew.

I cut into bone, between the phalanges,

through the interphalangeal joint.

That’s in the forefoot, which bears half the body’s weight.

To this day, both of us walk with a slight limp.

The problem is that you do desperate things for love.

We loved her, the woman who wanted us to be perfect:

unblemished skin, waist like a corsetier’s dream,

feet that would fit even the tiniest slipper.

And so we played the aristocratic game

of identify-the-princess.

Sometimes it’s a slipper, sometimes a ring.

Oh mother, love me without asking me to scrape

my fingers like carrots, cut off my heels and toes.

Eventually, she became your favorite daughter,

the cinder-girl, the princess-designate.

She was the best at being perfect, but abuse

will do that to you.

A woman comes into my office, asking me

to cut off her little toes so she can wear

the latest fashion. I sit her down and say

did you know that your feet provide the body

with balance, mobility, support?

Come, let me show you a model: here’s the toe,

metatarsal and phalanges. You can see

how elegantly they move, as in a waltz,

surrounded by your blood vessels and nerves,

the ball gown of your soft tissue,

a protective coat of skin, the delicate nail.

Look, underneath, how beautiful you are . . .

(This illustration is by Charles Folkard, for an edition of Grimms’ fairy tales.)

November 14, 2015

The Morning After

The Morning After

by Theodora Goss

Even on the morning after

a great tragedy, the world is still beautiful.

Should it be? I don’t know.

Perhaps after the slaughter, after

the bodies lying in a field, the houses burning,

the clouds should no longer continue intermittently

concealing and revealing the sky. Perhaps the leaves

should stop turning orange and yellow and red.

Perhaps they too should honor the dead.

But they don’t.

If anything, the world says to us:

my strange, impermanent children,

look at my mountains. Learn to breath, as they do.

Look at my forests, at the trunks of trees that have grown

over a century. Or the grasses, renewed annually.

They live and die, yet are no less important than the rocks.

The moth that lives for a day is as precious

as the tortoise.

Learn to love what you are: a part

of the whole. Do not divide yourself.

Do not think you are alone, or you alone

walk this earth. The wolves slip through the forest

and above you, the wild geese are calling.

You are part of the family: let that be

not frightening but reassuring.

This morning, the river will not mourn with you.

It will continue to flow, as it has since before

you were born. But as you memorialize the dead

again, for this has happened before, it will remind you

that beyond strife and sorrow and anger,

the leaves are turning. That it is autumn,

and the swallows are preparing

once again to fly south.

November 8, 2015

Beauty to the Beast

Beauty to the Beast

by Theodora Goss

When I dare walk in fields, barefoot and tender,

trace thorns with my finger, swallow amber,

crawl into the badger’s chamber, comb

lightning’s loose hair in a crashing storm,

walk in a wolf’s eye, lie

naked on granite, ignore the curse

on the castle door, drive a tooth into the boar’s hide,

ride adders, tangle the horned horse,

when I dare watch the east

with unprotected eyes, then I dare love you, Beast.

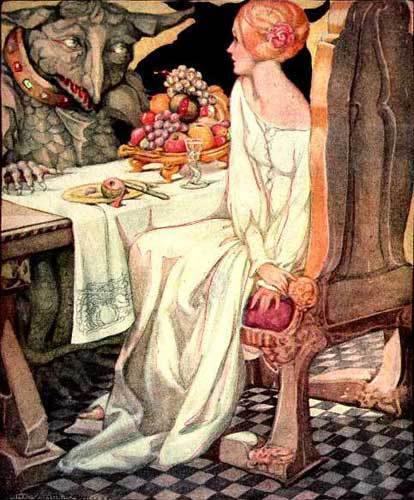

This image of Beauty and the Beast is by the Scottish painter and illustrator Anne Anderson. I particularly like it because it shows a beast that is genuinely beastly — not handsomely leonine. And it shows Beauty’s reluctance, in the half-turned body. But the Beast also looks gentle and concerned, as he is in the story by Madame de Beaumont.

I wrote this poem a long,long time ago — when I was in law school. It’s still a favorite of mine. If you would like, you can hear me read it:

This poem, and many more, can be found in my poetry collection, Songs for Ophelia.

November 7, 2015

Heroine’s Journey: Meeting Friends and Helpers

It’s been a while since I posted on the Fairytale Heroine’s Journey. What I’ve decided, in the last week, is that after I finish the book I’m currently writing, I’m going to write a book that brings together all the elements of the Fairytale Heroine’s Journey, and see if I can find a publisher for it. But in the meantime, I’m going to keep blogging about it, trying to generate the material from which I will write the book. That will allow me to think aloud, and also, if you want to, allow you to come on the journey with me.

Today I want to write about the fifth step in the process: The Heroine Meets Friends and Helpers.

In fairy tales that contains a heroine’s journey (not all of them do, of course), we usually find friends and helpers. Vasilisa the Beautiful has her doll, who helps her do the required chores in Baba Yaga’s hut. Snow White is most famous for the dwarves who help her out: in the Grimm version, they are simply seven dwarves, but Disney gives them names and personalities. He also adds the forest animals who help Snow White do housework in the dwarves’ house, and comfort her in the dark forest. (As we have seen, entering the dark forest is step three in the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey). In the Grimm’s version of “Cinderella,” Aschenputtel is helped by the birds that perch in the hazel tree growing on her mother’s grave. They help her sort lentils from the ashes, they give her dresses and shoes for the ball, and in the end, they peck out the stepsisters’ eyes. (Yes, I know, that’s such a harsh conclusion — why would friends and helpers do that? We’ll have to discuss the harsh conclusions of fairy tales later in the series.) In a Chinese Cinderella-type story, “Yeh-hsien,” the heroine is helped by a fish that she has fed and nurtured.

One thing we’re seeing so far is relationships of reciprocity: the dwarves take care of Snow White, and she keeps house for them. Aschenputtel cares for the hazel tree growing on her mother’s grave, and the birds in the tree help her. Yeh-hsien takes care of the fish, and even after her stepmother kills it, its bones give her clothes for the festival. The other thing we’re seeing is the power of a protective parent. Vasilisa’s doll was a gift from her mother. The hazel tree grows from Aschenputtel’s mother’s grave, and it’s clear that the gifts and protection come from her. In Perrault’s version of “Cinderella,” the fairy godmother has a parental relationship with the cinder-girl. She is, in a sense, a substitute mother figure. (Godparents did, indeed, have important roles in seventeenth-century France. They often provided what the parents could not, including financial help.) In “The Goose-Girl,” the heroine’s friend and helper is the horse Falala, whose head continues to speak even after it has been cut off. What that head does is confirm her identity: it’s the only entity that knows she is still a princess, not a goose-girl. And it’s also linked to her mother: as she passes the head each morning and evening, it says,

“Alas, young Queen, how ill you fare!

If this your tender mother knew,

Her heart would surely break in two.”

There’s a sense in which Falala speaks for the mother, who is not there to protect her daughter.

In “East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon,” the heroine is helped by the three old women who give her golden objects, with which she can rescue her bear husband. She is also helped by the winds, who take her to that impossible place, where he is being kept by a troll queen and princess. In “Sleeping Beauty” we have the fairy who mitigates the curse of death. In the Basile and Perrault versions, we also have the cook who saves Sleeping Beauty and her children. In the Basile version, “Sun, Moon, and Talia,” a king finds and impregnates Talia (the Sleeping Beauty) while she is still asleep. She has two children, Sun and Moon. She wakes when the two children, seeking her breasts to suck, instead suck on her fingers and draw out the piece of flax that has been lodged under a nail. Once the flax is out, she wakes up again. The king’s wife (yes, he has a wife) finds out about Talia and is understandably jealous. She summons Sun and Moon to the palace, where she has them killed and served up to the king. Then she summons Talia, whom she plans to burn in a fire. At the last moment, the king finds out what has been happening and saves Talia. Then the cook confesses that he has saved Sun and Moon, who were not killed after all, and served the king ordinary meat instead. The queen is burned instead of Talia, and the king, Talia, Sun and Moon live . . . happily ever after? I don’t know, this is a depressing version, isn’t it? It’s very much of Basile’s time, the Renaissance: a tale of power struggle, violence and violation, cannibalism. Its basic structure resembles Greek tragedy or Jacobean drama, not what we’re used to in a fairy tale. For me, it’s a useful reminder that the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey, as it has come down to us, does not have a simple or purely positive history. That history contains messages about women’s lives that we will want to both examine carefully and potentially reject. That is why the journey is continually being rewritten. Perrault, making his version of “Sleeping Beauty” more respectable for a French aristocratic audience, turns the king’s wife into his mother, who is an ogress. She wants to eat the princess and her two children, simply because ogresses enjoy human meat. In this version, the cook saves all three of them. The Grimms take out this entire episode, ending with the kiss of true love and the marriage of prince and princess. Their version, “Briar Rose,” was revised specifically for children, so rape and cannibalism had to be taken out. (Although other tales in their collection are dark enough!)

In “Beauty and the Beast” we also have a fairy: no surprise, since it’s a French fairy tale. The French fairy tales are chock full of fairies, whereas the Grimms tried to take them out, deeming them too French . . . So in French versions, helpers are often fairies, whereas in other traditions, closer to the oral folktales, they are more likely to be animals or old women who are actually witches. (Lesson of the fairy tale: always be kind to old women or animals, because you never know what power they might have.) I don’t remember friends and helpers in “Rapunzel” or “Six Swans,” so they don’t necessarily appear in every story. But the pattern is clear enough that I think we can conclude finding friends and helpers is part of the pattern. And this is important: when these elements of the journey don’t appear in one version, they often appear in another. In Andersen’s “The Wild Swans,” the queen of the fairies helps Eliza, the girl whose brothers were turned into swans. She appears first as an old woman and then in her own beautiful form and tells Eliza how to break the spell. It’s as though this pattern is imprinted in us somewhere, and later storytellers will often add what is missing in earlier versions. So, for example, Disney added the three helpful fairies to his animated version of “Sleeping Beauty,” and he sent his Princess Aurora into the dark forest, although the only dark forest in earlier versions is the one that grows up around her.

I’ve spent a lot of time here talking about the tales, and not what they mean to use. But I think the lesson is that we need to find our own friends and helpers. Often, we find them when we need them most, in the dark forest, as Snow White did. If we can take some lessons from this portion of the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey, I would suggest the following:

1. When you’re lost and alone, in the dark forest (even if it’s a dark forest of the soul), look around for your friends and helpers. You might be surprised to find they’re there with you. Let them help you . . .

2. Give back, be a friend and helper yourself. Even if you’re the heroine, clean the dwarves’ house, take care of the magical fish. Reciprocate for the care and friendship you receive.

3. Never discount the friendship of animals or old women. They may help you when everyone else has turned away . . . And they might be a lot more powerful than you expect.

This illustration for “Cinderella” is by Margaret Tarrant.

October 31, 2015

Writers and Money

This year, my writing income will exceed my expenses. Last year, it was the other way around.

That’s how it is with writing when you’re trying to build a career. I should explain what I mean by a career, because I have a job that gives me a regular income, in addition to which I have writing income (sometimes). It’s not a “day job,” which usually refers to a job unconnected with writing that you intend to do only until the writing works out . . . until writing itself can become a career. For one thing, I don’t just do it during the day. I teach, which means that I’m often up late at night, grading papers or preparing for classes. But I chose it specifically because it was about writing; it immersed me in writing and thinking about writing. My job is to teach writing: both academic writing at the undergraduate level, and creative writing at the graduate level to MFA students. I’m very, very lucky: I get to work on and think about what I love, every day. Oh, sometimes it’s tedious grading student papers. But grading papers, even at the most elementary level of marking the missing commas, makes me think about writing. It makes me consider what good writing is, why certain voices are lively and engaging. And of course it provides me with an income.

Because the thing I’ve learned about writing, over the years, is that it’s very, very difficult to make a living at it. Oh, people certainly do, but it’s a very small percentage of the people who actually write. Most of the people I know who make a living at writing have certain characteristics in common: (1) It took them a long time to get where they are, making a living at writing. Usually, you need several successful books in print before you can make anywhere near enough money from them to live on. (2) In the meantime, they had to rely on regular jobs, or on spouses who could support them. If they did not have those things, they went through a period of terrible struggle, and by terrible I mean not knowing where rent or food was coming from. (3) They write a lot, and they write fiction that is popular, that sells. As writers, they are both popular and prolific. (4) They are generally out there, at conferences or on social media, marketing their books. It’s certainly possible to be a wildly successful reclusive writer, but it’s rare. (5) They continue to supplement their income, with part-time teaching or freelancing or writing tie-ins.

If you want to be a writer, it’s best to confront the realities of writing income. First, you’ll have to write novels. The average short story sale will make you several hundred dollars, which is very useful when you’re trying to buy groceries or pay rent, but won’t sustain you over the long term. And poetry only pays for coffee. So you’ll have to write novels, and you’ll have to write them fairly consistently. The second reality is that writing income is itself inconsistent. I recently received half of the advance for my first and second novels. It was more money than I have ever put into my bank account at one time — I’m pretty sure my bank now thinks I’m money-laundering. But it was also the most money I’ll receive for these novels at once, unless they do every well indeed. I’ll receive more money when each of the final manuscripts are delivered, but it will be a smaller amount. And then of course when the film deal is made . . . Ah, but we’re just dreaming at this point. That happens, but not often, so what I have to count on right now is my advance. For which I am very grateful, but whether I’ll get this much money again from these books is up to the publishing gods. The only thing I can do about it is make these books the absolute best they can be, and then go on to write the next book.

The third reality is that publishing advances sound a lot more impressive than they actually are. For example, think of a writer who gets a quarter million dollar advance for a five-book series. A quarter million dollars! That’s an enormous sum of money. Until you break it down: that’s $50,000 per book. If each of those books takes about six months of work total, to write and revise, then revise again when the edit letter comes, then revise in response to the copyedits, the writer is making about $100,000 per year. That’s still a lot of money! But out of that, the writer is paying all the things that are invisible to regular employees. For example, I cost my employer, the university, about twice what I actually make. Among other things, the university pays for part of my medical insurance and matches any retirement fund contributions. The self-employed writer must pay for medical insurance and fund her own retirement, plus there’s a small thing called self-employment tax. I have to pay it on the writing portion of my income. So that advance isn’t the same as making $100,000 per year at a job. It’s like making $100,000 a year from a business, and then having it reduced by business expenses. If you’re a writer, you’re a business. So sayeth the IRS. And think about all the marketing for those books. It takes time to publicize a book, and even if the publisher pays travel expenses for readings and signings, that’s time the writer could be making more money by writing. It’s unpaid time, or time paid for by the advance. Finally, it can take considerably longer than six months to write a book. If it takes a year total, that income goes down to $50,000 per year, minus business expenses. And that’s on the high end of a novel advance . . . (The average novel advance is well under $20,000 per book.)

When I finished my PhD and started working full-time, I had to confront all this myself. I had to ask myself, are you going to treat writing as a hobby, or are you going to make it your career? Of course the answer was, a career. That’s what I’ve always wanted, to be a professional writer. That doesn’t mean I want to write full-time: I love teaching. It does mean I want to write every day, and produce on a regular schedule. I want to have novels and short stories and poems coming out regularly. I want to be known as a writer. So how, I had to ask myself, was I going to think about money? I had already spent a lot of money on my writing career: I had gone to Odyssey and then Clarion, I had been to any number of conventions. And those were all worth it, because they gave me the training and the contacts I needed. But now, I really wanted to think about my expenses as investments. Was a particular convention worthwhile? Would I learn from it, would I meet people I wanted to meet — writers I admired, editors I would love to work with? It’s wasn’t enough that I would have fun, because let’s face it, conventions are expensive. Did I want to spend $1000 on an industry convention where I wouldn’t necessarily meet readers, or should I put that money toward a research trip to Europe for the second novel? (That was an actual decision I had to make recently.) I haven’t been to as many conventions recently, because of such calculations. I’ll be going to more next year, because I’ll have a novel coming out in 2017 . . . So the investment will make sense.

I also had to do one more thing: I had to confront my own issues with money. My issues come partly out of the fact that I grew up in a household where money was always uncertain. We always had just enough money to get by, although sometimes the bills were paid late. But there was no concept of savings. My mother had grown up in communist Hungary, where if you had anything extra, it was taken away from you. My grandparents could not buy the apartment they had lived in since World War II until after the fall of communism. I was used to money coming and going, but never staying . . . that was my normal. I hated it — it made me feel uncertain, as though I were always standing on ground that could be shaken by an earthquake. But it was still how I, unconsciously, thought about and dealt with money. (It did not help that for years I had been a graduate student living on fellowships.) I had to consciously reevaluate my unconscious attitude toward finances, to make having savings a goal. To tell myself that money in the bank was normal, not an aberration. That it was not all right for me, who was lucky enough to have a stable job (when so many don’t), to get to the end of the month and worry about whether I was going to make it. I had to consciously build better habits. I’m still working on that.

If you want to be a writer, what I would advise is something like the following: (1) Be realistic about what it will mean financially. You may write a best-seller and never have to worry about money again for the rest of your life. That’s very, very unlikely. Even people who write best-sellers have to keep working, keep producing. I know, I’ve met them. They’re sitting with their butts in chairs, just like the writers who are starting out. (2) Deal with your money issues, because in a field as uncertain as writing, they will undo you. If you’re not used to saving and budgeting, start practicing now. (3) Make a plan, revise your plan. How are you going to support yourself? What will your sources of income be, while you write? How will you create a good life for yourself, a life you want to live, that also supports your writing? You don’t have to have a writing career . . . no one does. Writing can be a wonderful, fulfilling hobby. But if you want it to be a career, you need to treat is like a business (you know the IRS will!), even if you’re only making coffee money for right now.

(I should say here that I don’t budget, not formally, although I did while I was in graduate school. What I do now is know, at the beginning of each month, that I will have a number of recurring expenses, such as my electricity bill. On top of that, I will have necessary expenses, like groceries. I don’t worry about those. A certain number of small treats go in with those necessary expenses, like buying cupcakes for myself and my daughter — it’s a weekly ritual. I know what those recurring and necessary expenses will be, and I know that I can afford them — for those, I don’t need to budget. Beyond that, I have to think about how much I’m spending and why I’m spending it. I have to justify the expense. But perhaps that’s a subject for another blog post? And my taxes have gotten complicated enough that I would not tackle them without an accountant, which is another expense of doing business . . .)

Coming to terms with money, getting to the point where I could handle money with only a moderate amount of trepidation and anxiety, has been an important part of my adult life. But I’ve had to, because if you want to be a writer, and at the same time you want to eat and have a roof over your head, you have to address the money issue. Hopefully this post will help, a little . . .

This was me recently, in my novel-writing uniform. Sweat pants and fuzzy slippers. The fuzzy slippers are particularly important . . .

October 23, 2015

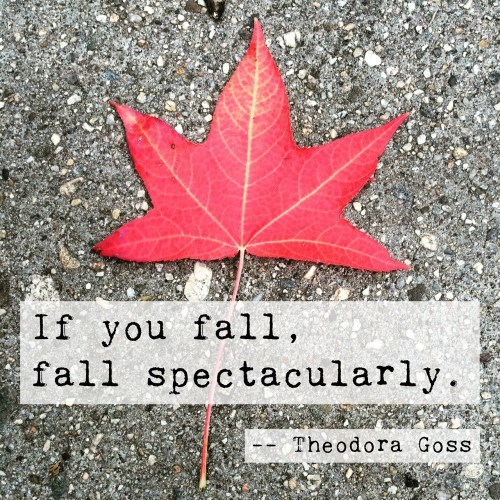

Fall Spectacularly

Yesterday, I was walking along my street, where the leaves on the trees have started to turn from green to red and yellow. And I saw this red leaf on the sidewalk, looking particularly spectacular. So I knelt down to take a picture. As I was kneeling on the sidewalk, the leaf spoke to me!

Do leaves speak to you? I bet if you read this blog, leaves and sidewalks and the whole of creation speaks to you . . . It certainly does to me. We just need to make sure we’re listening. Well anyway, this leaf spoke to me, very quietly, as leaves do. In almost a whisper . . . What did it say? you might ask.

It said, “If you fall, fall spectacularly.”

So I made a quotation photo, just so I could remember what the leaf said. It’s for you too, so feel free to share . . . (I put my name on it, but really the leaf said it first!)

October 18, 2015

Writing Your Stories

One of the hardest things about being a writer is that you can only tell your own stories.

I don’t mean that you can only write about yourself, or only about people like you. Of course you can write about different people, different places, different cultures. But the stories have to come from inside you. What you find outside needs to correlate to what you have inside. One of my central stories, for example, is losing a country. Or a family. It’s a story I find myself telling over and over again, almost as though I’m still trying to understand it. I could tell that story in a number of different ways, but the important thing is that it comes from inside and it wants to be written.

I’ve tried, before, to write the way I thought I should write. It never worked — the writing came out stiff, artificial. I see my students do it sometimes. They tell themselves, I’m writing a YA novel and this is the rule for writing a YA novel. They follow the rule, and the writing comes out sounding almost as though it were written by rote. It’s not alive . . .

“You can only tell your own stories” sounds almost inspirational, as though impelling you to tell your stories — it sounds as though it’s saying “you must tell your stories because no one else can tell them.” Which may be true, but it’s a different sentiment. “You can only tell your own stories” is actually a warning and a lament. Why a lament? Because what if your stories are not the ones culturally valued at that particular moment? What if you write poetry like Emily Dickinson or horror like H.P. Lovecraft? It’s going to be a hundred years before you are lauded as the most important poet of your generation, or people crochet Cthulhu hats. What if the stories in you aren’t New Yorker stories, or the sorts of stories that get you teaching positions in creative writing programs? I’m not talking about bad writing. I’m taking about good writing that isn’t what the culture wants or recognizes as innovative at a particular time. Or maybe ever . . .

I’m not sure, here, to what extent I’m talking about my own writing. After all, I’m writing in a genre that’s slowly being recognized as culturally important. I have many opportunities to publish my work. But even I feel, sometimes, as though my work is out of step, as though I am out of step with a mainstream. Or even, sometimes, where my own genre is going. But all I can do is write out of myself, dig deeper into myself, plumb my own depths to find the stories living down there. They are down in the mines of the self . . . And then find the things outside myself that correlate with those stories.

I was thinking, earlier today, of what is mine, what I know to be mine. What has become a part of myself. And I made a list:

1. Lists. Linear thinking, understanding through categorization. I learned it in law school, but it was always in myself. I have a logical mind that wants the world to be orderly. (Hint: it often isn’t.) I love order and structure and the intellect. I love the precision of a ballet class.

2. Flowers, and gardens more generally, and specifically roses. I love their names: Cardinal de Richelieu, Madame Hardy, Cuisse de Nymphe. I know them by name, I know their histories. Tall trees, running water, still pools. The calm of ordered nature.

3. But also wilderness: the beauty of mountains, rushing streams, storms. Mountain slopes covered with forests, like the ones where I grew up. Their blue, one behind the other as though a giant had filed them, fading into the distance.

4. Europe, especially Eastern Europe, which calls itself Central Europe. And Hungary, my own little corner of Europe. Even though I lost it, it’s still mine. I still claim it, and I hope it somehow claims me.

5. The perspective of the immigrant, the emigrant. The one who wonders where she belongs, who thinks in two languages. Who is perpetually an outsider, belonging to both cultures but never entirely to either. Who feels perpetually inadequate, not enough in either place.

6. Fairy tales, especially the dark Eastern European ones I read as a child.

7. Poetry, especially poetry that sings, as it has sung all my life through my head.

8. The nineteenth century, because I studied it as a graduate student. I am professionally trained it in, and have in a sense made it my own. And there is something temperamental that calls me back to the literature and art of that era. The end of the century, which I know best, was a time of transition, of becoming. And I seem to have always been in that process. No wonder I like vases with dragonflies on them . . .

9. Monsters, doubles, the Gothic and all its paraphernalia. Perhaps because I was born in Hungary, perhaps because I am an immigrant, perhaps simply because of who I am. I have always sympathized with those created by mad scientists or infected with vampirism. I have always felt myself to be double, like William Wilson . . .

10. Handicrafts: sewing, knitting, lacemaking. And art, which does not seem so different, I suppose because my grandmother did all these things and they were all expressions of herself, her own creativity. I have always assumed that women make art, because in my family they all do.

So I guess that gives me immigrant monsters who sew and grow rose gardens, somewhere in the forest at the foot of the mountains? And make lists . . . Or maybe the story is in the form of a list? Which, yeah, is actually the sort of thing I write! I’m pretty sure it will never make it into the New Yorker. I think there is an 11:

11. Sincerity, belief in a deeper meaning, a deeper pattern. A pretty complete absence of sarcasm and snark, although I’m all right at irony, I think. A lack of interest in things that are contemporary simply for their own sakes, in brands for example, in things that are culturally “cool” but I feel are pretentious. A belief in the importance of beauty. For its own sake, and for ours. And also,

12. A horror of violence, so that I will never write a story in which random people randomly die, and it doesn’t matter, or it’s done to make a point. Every single character matters, to herself if no one else.

So that’s a bunch of it, at least: the bundle of things that make up what I write, where it comes from. I guess I can only keep discovering my stories by writing them. But they will come from me, from the woman who loves roses and monsters and lace, and hates violence. And if at some point the culture decides they are worthwhile, that will have nothing to do with me. I will have written what is in me, which is really all I can do, and all I aim for.

This is me (the me that all the stories come out of):

October 17, 2015

One of Those Days

One of Those Days

by Theodora Goss

It is one of those days when I feel completely out of step

with the world, when I am convinced

I should be somewhere different . . .

Walking through a forest of tall trees, preferably maples

because it is autumn, and their leaves would create

a carpet, maybe even a path

of red and yellow. And I could follow it,

in the belief that I was going somewhere.

What has happened to my life?

My moments are measured by clocks,

not by the chirping of crickets, or the call

of birds in the underbrush at the edge of the forest,

not by the movements of water

as it falls over rocks into a pool.

Not by the sun sinking lower.

Although I know, I can feel, that it is all

falling: the leaves, the sun,

the running water into the still water.

And then the birds and crickets falling silent.

I can feel it even though in my efficient life

where the clocks are marking time,

all the minutes are the same: one after another,

in equal intervals. Still, outside my window,

behind the reflected electric lights,

slowly darkness comes,

like a benediction. And I feel

once again, that I was born elsewhere

and have, still, elsewhere to go . . .

where beneath tall trees, slowly the leaves

and evening are falling together.

I wrote this poem on a day when I was feeling exactly like this! If you’re interested in my poetry, you can read more in my poetry collection, Songs for Ophelia.

October 11, 2015

Looking Within

The more I study myself and other people, the most I realize that if you don’t find the things you need inside yourself, you won’t find them on the outside. You can’t find the things you need outside yourself.

I’m talking about the things you really need: love, success, affirmation of your fundamental worth. Our physical needs can be met externally. We can find food, shelter. But our emotional needs, our inner needs, can’t. Not really. Or not, at any rate, after childhood. Hopefully when we are children, we feel loved by our parents. We feel as though we are the most important thing in their world, that our successes and failures, our hurts and triumphs, matter deeply to them. This is not narcissistic: it is what a child needs to be healthy. The child then internalizes that love, and it becomes the self-love that he or she will need as an adult. Not having that sort of love as a child is a psychic wound that later needs to be healed. I’ve seen many of my friends with that sort of wound, in the process of healing. It’s not easy.

Once, when my daughter was young, I was sitting in a park playing with her. Another mother was there, also with a young daughter, and a grandmother with her grandson. The grandmother had been watching that other girl (mine was just a toddler at the time) playing in the sandbox. I’m not sure what prompted the comment, but she leaned over to that mother and said, casually, “She’s a little spoiled, isn’t she?” I recognized her accent at once: it was Eastern European. And I thought, I know the culture you come from. I know it so well, because it’s my own. And I know the generation you come from too, because my grandparents came from it. It’s the generation that lived through World War II, and to them, all the younger generations were a little spoiled, their lives a little too easy. You can understand that perspective: they had lived in the worst of times, under the Germans and then under the Russians, through no food and then bread lines. They wanted to prepare children for the reality of the world. Would children who were spoiled, who were too loved, be ready for privation? Starvation, even?

But I think that’s the wrong way to look at it. Children can’t love themselves: they can scarcely love other people, at that stage. They are being bombarded all the time by a strange world, a world too large for them, a world beyond their understanding. Their emotions are in a turmoil. At that stage, they need external love, and hopefully there is someone around — if not a parent, then a grandparent, another relative, a friend — to give it to them. Later, that love will form a sort of rock in their consciousness, a place to stand. They will have the knowledge that they were well and truly loved.

But what happens later? That’s what I’m really concerned with here. Now that we are all online, we get constant glimpses into other people’s lives, and I see so many people mourning their lack of certain things . . . emotional support, a partner to love and care about them, success in their chosen fields. They want those things so badly, and they want those things to come to them from the outside. And those things may, but when they do . . . they won’t be enough. That’s the ironic thing, isn’t it? By the time you’re an adult, if you haven’t built that rock to stand on inside you, nothing that comes from the outside will ever been enough. When love comes, it won’t be enough, and you will doubt it. Surely you’re not worthy of it? Surely it’s not real? When success comes, you will want more success, greater success. You will realize that any success can go away, and the knowledge will be like sawdust in your mouth.

When you’re an adult, in order to recognize the things outside yourself, to benefit from them, you must already have them inside you. This operates on a physical level as well: if you are hungry on the inside, no amount of food will make you feel full. You will continue to hunger. (Then you will need to figure out what you’re hungering for.) It’s a strange image I’ve created here, building a rock. You can’t build a rock, not physically. But maybe you can psychologically, the way nature and time build rocks? I thought of using the word “platform” instead, but that’s not strong enough to express what I mean. It’s a rock to stand on, something solid. And it needs to be inside you, because all the things outside you are ephemeral. They can go away. The people who love you can stop loving you. The success you wanted so badly can end in failure. All the external signs of your worth can disappear, with a turn of the wheel of fortune that medieval scholars thought governed our lives. Then what are you left with? What you have inside, that’s all.

So you have to work on what’s inside. That’s not easy, is it? Particularly if after childhood you were left not with a solid rock but with an emptiness, a sort of windy darkness — if what you are standing on is empty space. But either way, the project is the same: you have to build and maintain a rock on which to stand, your own rock. You have to love yourself, and find love within yourself. You have to feel successful, even when your work has been rejected. How do you do that? Little by little, bit by bit, stone by stone. Everyone does it differently, and it’s hard, and it takes a long time. But learning to find what you need inside yourself is the process of becoming an adult. I wondered if I had any wisdom to offer on how to do this, how to build your rock. And I thought, this is all I know:

1. Treat yourself as though you were someone you loved.

2. If you have failed, reward yourself: you are one of the brave ones who tried.

3. Remember Vincent Van Gogh. He failed all his life, and created some of the greatest beauty of which human beings are capable.

For me, finding what I need inside myself has been a very long process, one that has taken all my life. Am I there yet, at perfect self-sufficiency? Of course not, and I don’t think I ever will be. I don’t think anyone is, except perhaps Buddhist monks. I am not a Buddhist monk. But I can say that I’m better at it now . . .

I do know that the process of finding what you need inside yourself, finding love, courage, peace, is one of the most important processes we go through as human beings . . . and as artists, for those of us in the arts. That rock inside yourself is a platform, from which you can jump. And maybe fly.

(I thought this would be the right image for this post. I took it yesterday, while walking through the woods, visiting my friend Autumn.)