Theodora Goss's Blog, page 18

February 2, 2015

A Still Place

I haven’t posted for a while, and it’s partly because I’ve been so busy. Mostly because I’ve been so busy. But there’s something else . . .

I feel as though I’m in a still place, a place of stasis. That’s not necessarily bad. Stillness is also peaceful, and I’ve been feeling less frantic than I have in a long time. It’s a good place: I love everything I’m doing. I love teaching undergraduate writing at Boston University, I love teaching my graduate creative writing students at Stonecoast. I have enough money to cover my living expenses and some luxuries, which certainly hasn’t always been the case. (Graduate school — ugh.) I live in a beautiful apartment, in a beautiful city. I just happen to have the best daughter in the world.

But it’s a strange place, too, because I’m not used to standing still. I’m used to things happening, to continually moving toward. Or, you know, away from . . . I’m used to a sense of motion, rather than stillness. It’s strange, for me, to think that I could stay here for the rest of my life, and it would be a perfectly good life. If nothing changed, I would be fine. Of course, that never happens. Things always change: if nothing else, I will get older. Nevertheless, if I stayed here, where I am, for a long time — it would be perfectly fine. And sometimes that fills me with a sense of panic.

I think it’s because I’ve spent my entire life moving from place to place, adjusting to new circumstances. Hungary to Belgium to the United States. Philadelphia to Washington D.C. to Boston. To Richmond to New York to Boston again. University of Virginia to Harvard to Boston University. And now here I am, having lived in Boston for a long time, having been at Boston University for more than ten years, as a student and then teacher. A great deal has happened in that time — and it’s really only in the last few months, since I settled into this apartment, that I feel as though I’ve arrived someplace. That I’m not just transitioning from one place to another. There’s something lovely about feeling settled. But I’m not used to it.

I suppose what I should be thinking is, I’ve come to a place that I can build on. Here, where I feel both strangely at peace and agitated from that strangeness, I can finally start to build what I want to, which is books — I want to build out of words. My first full-length novel is already with my lovely agent. I just sent him a synopsis of the second novel. And I do have so many ideas, for novels and stories and essays . . .

So I suppose my advice to myself should be: settle in and work.

The other thing I need to remember, to remind myself of, is that nothing ever stays the same. Stasis is, in the end, an illusion. The world may feel still, but it’s spinning. Everything we do, every choice we make, can change what happens. Who knows what will happen with this novel, or the one after it, or the one after that. The more we do, the more opportunities we are given to do things. And that sometimes means we are overwhelmed with work (ahem). But it also means we get to do amazing things . . .

I have already gotten to do a lot of amazing things. And I intend to do more.

So I need to take this stillness as the gift it is — a time when nothing seems to be happening, and I can maybe catch up, take a breath. Get ready for whatever is to come.

(These pictures are from our snowstorm last week. Today we are having another snowstorm, and once again university classes are cancelled. I don’t remember them being cancelled twice in one semester . . . ever. Not since I arrived here more than ten years ago. This is a particularly heavy winter, just right for being contemplative.)

January 15, 2015

Stonecoast: Raven Poems

I haven’t written a blog post in two weeks! It’s because I’ve been teaching at the Stonecoast MFA Program. Once I got over the flu, I only had a few days to prepare, and then I was off on the train up the coast, to Freeport, Maine. Stonecoast is a low-residency MFA program, one of the best in the country, and I’m very lucky that I get to teach there. I’m particularly lucky because Stonecoast has a Popular Fiction section, which means that I get to teach not just writing in general (although I certainly teach that), but also specifically writing fantasy, science fiction, and mystery. This time, I led a workshop specifically on writing fantasy and made a presentation on Agatha Christie’s plotting. In a low-residency program, students spend each semester working closely (but at long distance) with a mentor, and then they gather for the twice-yearly residencies. That’s where I was: the winter residency.

But now that I have some time to write blog posts, I’m going to write about my experience at Stonecoast. So I’ll tell you how my residency went . . . And the first thing I’m going to do is post some poetry. I arrived at Stonecoast last Friday and immediately plunged into greeting faculty members and old students, meeting the new students, and of course the work of the residency. That first night, we had our first reading, and I was one of the readers. I read two poems, both of them about ravens. So I thought I would reprint them here! In my next few blog posts, I’m going to describe some of the things I taught. Of course I can’t give you the full flavor of what it was like — you had to have been there. But it will at least give you a sense of what I did during the residency, and some thoughts on fantasy and mystery (the two genres I focused on this time), as well as teaching in general.

(People sometimes ask how they can take create writing classes with me. The answer is: at Stonecoast. That’s it, I’m afraid. It’s the only place I teach creative writing, to the Stonecoast MFA students. But if I teach any place else, I will post that information . . .)

So to start us off, here are the raven poems that I read, with expression of course, that first night:

Ravens

Some men are actually ravens.

Oh, they look like men.

Some of them in suits,

some of them in shirts embroidered

with the names of baseball teams,

some in uniforms, fighting in wars we only see

on television.

But underneath, they are ravens.

Look carefully, and you will find their skins of feathers.

Once, I fell in love with a raven man.

I knew that to keep him I had to take his skin,

his skin of feathers, long and black as night,

like ebony, tarmac, licorice, black holes.

I found it (he had taken it off to play baseball)

and hid it in the attic.

He was mine for seven years.

I had to make promises:

not to hurt ravens, to give our children names

like Sky, and Rain Cloud, and Nest-of-Twigs,

spend one night a week in the bole of an old oak tree

that had been hollowed out by who-knows-what.

I had to eat worms. (Yes, I ate worms.)

You do crazy things for raven men.

In return,

he spent six nights a week in my arms.

His black feathers fell around me.

He gave me three children

(Sky, Rain Cloud, Nest-of-Twigs,

whom we called Twiggy).

And I was happy,

which is more than most people achieve.

You know where this is going.

One day, I threw a stone at a raven.

I was not angry, he was not doing anything in particular.

It is just

that raven men are always lost.

Think of it as destiny,

think of it as inevitable.

I was not tired of our nights together,

with the moon gleaming on his feathers.

No.

Or maybe he found his skin in the attic?

Maybe I had taken his skin and he found it,

and he picked three feathers from it

and touched each of our children,

and they flew away together?

Maybe that’s how I lost them?

I don’t even remember.

Loving raven men will make you crazy.

In the mornings I see them hurrying to their offices,

the men in suits. And I see them in bars

shouting for their baseball teams, and I see them

on television in wars that have no names,

and I say, that one is a raven man,

and that one, and that one.

Sometimes I stop one and say,

will you send my raven man back to me?

And my raven children?

Some night, when the moon is gleaming,

the way it used to gleam

on long black feathers falling

around my face?

And here is the second poem:

Raven Poem

On the fence sat three ravens.

The first was the raven of night,

whose wings spread over the evening.

On his wings were stars, and in his beak

he carried the crescent moon.

The second was the raven of death,

who eats human hearts. He regarded me

sideways, as birds do. Shoo, I said.

Fly away, old scavenger. I’m not ready

to go with you. Not yet.

The third was my beloved,

who had taken the form of a raven.

Come to me, I said,

when darkness falls, although

I’m afraid you too

will eat my heart.

This is where I was staying last week, at the beautiful Harraseeket Inn, in Freeport, Maine:

And this is a bird’s nest I saw as I was walking down the snowy street, the last day I was there. It was filled with snow . . .

January 2, 2015

Calling in Sick

Yesterday, I called in sick.

Since it’s Winter Break, there was no one to actually call in sick to . . . so I had to call in sick to myself. In the ten years I’ve been teaching, I’ve only called in sick to cancel a class once, on a day when I could barely crawl to the phone to make the call. (This was back when I still had a landline.) Usually when I get sick, but not very sick, I have a conversation that goes something like this:

Body: I’m sick.

Mind: No, you’re not sick. I have a lot of work to do, so you can’t be sick.

Body: I’ll put off being sick until the weekend. But then I’ll really collapse.

Mind: Deal.

I’m very good at not being sick for a couple of days. And then I really get sick when I have time to. It’s something I learned back when I was in college, taking exams. I would study study study, take my exams, do well on them. And then I would go to bed for a week, sick from exhaustion. Nowadays I don’t have exams anymore, but the ends of semesters are just as intense, and I tend to overwork myself just as much. What’s changed is that I cut myself less slack. I assume that I should be able to (a) grade papers and submit final grades for almost sixty students, (2) make sure my graduating MFA students get in their final theses, (3) send a finished novel to my agent, and (4) prepare for Christmas, including the shopping and cooking and decorating, without getting tired or feeling ill. Gracefully, like some sort of academic Martha Stewart.

Instead, of course, I wake up one morning and decide that showering and making breakfast both sound like way too much work . . .

The problem with being a doctor’s daughter (and I’m the daughter of two doctors) is that one was never allowed to be just a little ill. When I told my mother that I felt sick that day, she would come take my temperature. And if I didn’t have a temperature that said “fever” to her, I had to go to school. After all, she dealt with children who were genuinely ill, who were being treated for diseases like cancer. What I was doing fell under the category of malingering. Now when I feel ill, the first thing I do is check my temperature. If it’s normal, I immediately say to myself, “I’m not sick.” The problem is, I never have a fever. The useful thing about being a doctor’s daughter is that when you call a parent and say that you have a pain in your side and it’s probably nothing, that parent can say “Go to the emergency room.” Several hours later, you are being prepped for an appendectomy. At first, the doctors didn’t think it was appendicitis, because . . . I didn’t have a fever. (Not having a fever when you have appendicitis is apparently some sort of bizarre medical anomaly. So I can say with some confidence, seriously I never have a fever. If I ever did, I would probably be convinced that I was dying.)

But if you feel ill, you are ill. The feeling itself is a symptom. If you’re so tired that you don’t want to do anything but lie in bed and watch British crime dramas, you’re ill. If you think a piece of toast and a boiled egg sound like a perfect dinner, you’re ill. If showering sounds like way too much trouble . . . Well, it’s time to call in sick. Also if you’re coughing and blowing your nose, but I tend never to trust physical symptoms.

Mind: You’re just coughing and blowing your nose to fool me into thinking you’re sick.

Body: Go. To. Bed.

Basically, I’ve exhausted myself. My body is completely out of whack, and I need to get it back in again. (Is there such a think as in whack?) And that means giving it what it needs, which is a lot of sleep, and rest, and time completely alone. So I’m letting it sleep whenever it wants to, as much as it wants. And I’m still doing the work that needs to get done before next week, but more slowly. I’m not bothering with going out, or seeing people, until I want to again. (I’m an introvert, so this is very much what I need.) Luckily, I have several pairs of pajamas. I have at least a couple of days until I run out of food. I will probably take a shower today . . . I have books and Netflix on my computer, so basically, I’m set.

I think every once in a while we just have to call in sick to ourselves. We just have to say, “I’m going to be sick. I’m going to be sick until I’m well again.” And then we have to sleep and sleep, and binge-watch British crime dramas, and drink herbal tea. I’ll know when I feel well again because I’ll decide that I’m just so bored, and I’ll want to see what the outside world is doing. I don’t think it will take long.

But until then, I’m going to be well and truly sick.

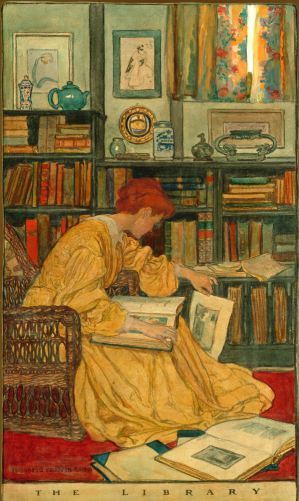

This painting is The Library by Elizabeth Shippen Green. I am nowhere near this elegant when I am sick. But let’s just pretend I am . . .

December 31, 2014

Why I Write

Last night, I stayed up late finishing the final edits to my novel manuscript before sending it to my agent for the second time. The first time I sent it to him, it was in the “well, I finished the novel but I’m still working on it because it’s not quite right, but here you can see that it’s finished” stage. This time it was in the “I hope you like it because honestly I can’t stand to look at it anymore” stage.

If you’re a writer and you’re sending manuscripts out, you know the stage I mean. It’s where you read through the manuscript on screen and decided to take out “that,” and then you read it on paper and decided to put “that” back in. And as you’re putting “that” back in, you stare at the screen, trying to read it both ways: with and without the word “that,” which really is only one of approximately 108,700 words in your manuscript. But there you are, agonizing over the one word. (“That” is one of my particular, personal problems. I did not realize this until an editor pointed it out and I did a word search on the short story she was editing. Sure enough, there were an awful lot of “that”s, about half of them unnecessary.)

These are the sorts of questions you ask yourself when you’re at that stage:

1. Should she have “dark brown” or “darker brown” hair?

2. Have I used the word “monkey” too often? (Word search for “monkey.”)

3. Do I need to mention that she left her umbrella at home? It wasn’t raining that morning.

4. How many characters are snoring? Is that too many characters? Do I need to cut some of the snoring?

5. Wait, where is her revolver? Is she holding it all this time?

I did, in fact, cut some of the snoring.

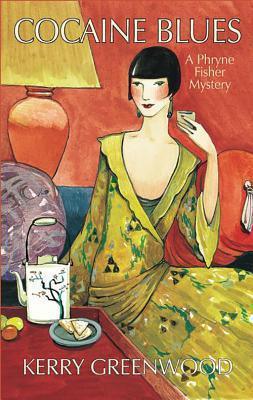

I sent the manuscript out around midnight, as an emailed document file, about 370 pages long (double-spaced). And then I celebrated by eating chocolate and watching two episodes of Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries, which took me to the end of Season 2. Now I have to wait until they film Season 3, which is entirely too long . . . If you haven’t heard of it, Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries is an Australian television series based on the books by Kerry Greenwood. If your taste in stories and television shows is anything like mine, you will love them. I adore Phryne (pronounced Fry-oh-nee), her 1930s Lady Detective, and I have to admit that I’m in love with Detective Inspector Jack Robinson. But that’s based just on the television series, since I haven’t read the books . . . yet.

So there I was, sitting in bed, in pajamas, eating dark chocolate with sea salted almonds in it, watching Miss Fisher on my computer (I don’t have a television). Thoroughly enjoying myself. And I thought: this is why I write. Because someday, someone might need something to entertain them, or cheer them up, or even just pass the time. And maybe my book will do that.

I think that’s worth all the agonizing over “that.”

It’s fair to say this novel took me two years to write: the first few chapters were written earlier, but I had to rewrite them after I finished my PhD and moved into my previous apartment. I had been thinking about the novel in the wrong way, and it took the mental freedom of having finished my degree to get it right. That apartment was where I really wrote the novel, finishing it last summer in Budapest and then adding the final chapters when I moved into this apartment, in August. Since then, I’ve been revising. And of course there has been a lot of revising along the way . . . Sometimes I think it’s pretty good, sometimes I worry that it’s awful and I just can’t see its awfulness. But I figure, it’s only the first full-length novel I’ve written, so if I mess up the first time, I’ll get it right the second time. Or the third. Or fourth. I’ll just keep writing . . . Someday, there will be a woman in pajamas, with chocolate, and she will stay up late to read something I wrote. Or maybe even watch something based on it, on her television screen!

So thank you, Kerry Greenwood, for doing that for me. You don’t know me from Eve, and you’re all the way on the other side of the world, in a country I’ve never visited, but you gave me two lovely hours. Oh yes, a television show is always separate from the book, although based on it. But it would not have existed without you, sitting in a room, probably in front of a computer, agonizing over that final draft. Just like me.

These images are from the Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries television show and the first book in the series, which I now want to read . . .

December 28, 2014

Writing Lesson: Observation

I thought it might be interesting to put down some of the things I’ve learned from teaching writing. From writing too, of course, but I find that when I teach writing, I tend to make certain points over and over. Because these are the sorts of things that many writing students need to work on. So I thought they might be interesting to point out here as well, for those of you who are writers, or who simply want to improve your writing . . .

The first one I want to talk about has to do with observation. If you want to be a writer, you need to also be an observer . . . someone who is curious about the physical world around you. I don’t know about you, but I find it harder to write about the physical world than about mental states. It’s easy enough to describe what someone is thinking, but try to describe someone walking down stairs. I mean, in a way that makes it interesting.

(Ironically, writing students often think the way to keep a narrative interesting is to include action scenes. But action scenes can get very boring, very quickly. It’s often less interesting to watch a character act than to hear her think. Physical actions are usually interesting to the extent that they illuminate something else: the character herself, the world in which she is acting, etc.)

When describing the physical world, it’s very easy to fall into clichés. And the best way to avoid clichés is to observe closely, to see things as they are instead of as people say they are. To see what actually is.

So here is an exercise for any writers among you: go and observe. I do it sometimes sitting on the metro, where I can see so many faces, all different. I think about what makes them different, what distinguishes them from one another. I try to remind myself to observe, because it’s so easy not to see, isn’t it? To go through our days, particularly when we’re busy, and simply miss what is around us. The colors of leaves on the sidewalk. The different kinds of stone in the buildings. And the world is hard to describe anyway, because it’s so specific, each part of it different from every other part, and yet the words we have are “gray stone” and “autumn trees,” and it’s hard for writing to get at that specificity. But we have to try.

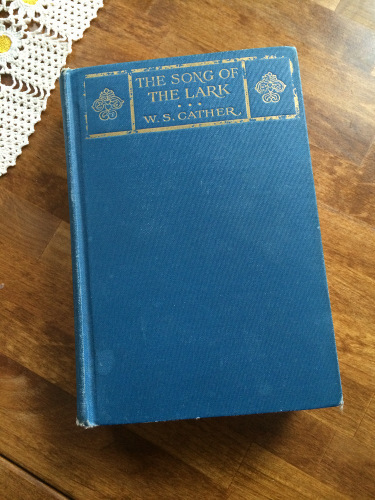

I was thinking about this recently as I read a description of a character in Willa Cather’s The Song of the Lark. The description comes right at the beginning of the book, two paragraphs in:

“Dr. Archie was barely thirty. He was tall, with massive shoulders which he held stiffly, and a large, well-shaped head. He was a distinguished-looking man, for that part of the world, at least. There was something individual in the way in which his reddish-brown hair, parted cleanly at the side, brushed over his high forehead. His nose was straight and thick, and his eyes were intelligent. He wore a curly, reddish mustache and an imperial, cut trimly, which made him look a little like the picture of Napoleon III. His hands were large and well kept, but ruggedly formed, and the backs were shaded with crinkly red hair. He wore a blue suit of wooly, wide-waled serge; the traveling men had known at a glance that it was made by a Denver tailor. The doctor was always well-dressed.”

This, by the way, is what Napoleon III looked like:

But I can imagine Dr. Archie without that image. He’s stuck in a small town in Colorado, but I know he will be a strong character, simply from the way he’s described. It’s a long description — you probably would not find one as long in a modern novel, since novels now are expected to move at a faster pace. But Cather avoids any clichés. She includes generalizations (“always well-dressed”), but also backs them up with specifics (the Denver tailor). And notice the information she does not give us: we don’t know the color of his eyes. It’s standard in student writing to find a description that focuses primarily on hair and eye color. Here Cather gives us hair color, but not just on Dr. Archie’s head. We also learn about his mustache and the hair on the back of his hands. We do learn that his eyes were intelligent, which is actually what we most need to know about him.

Do you see what she’s doing? She’s describing what we would probably notice if we actually met Dr. Archie. These are the things about him that stand out, that make him different from other people. That are specific to him.

So when you’re observing, you really have to observe two things at once: what is in front of you, and yourself noticing. You have to see how you’re seeing. And not just what is static, but also gestures. Here Cather gets gesture in a bit with the stiff shoulders; it’s a static description, but we get a sense for how he holds them, for how Dr. Archie moves. When you’re observing, think about how people move, how they walk down stairs, or put their hand on the railing, or look back up when they reach the landing. How do they turn back their heads? What do their gestures look like?

It occurred to me, writing this post, that writing handbooks often tell you how to write, focusing on the craft of writing itself. But they don’t often tell you how to be a writer: how to prepare yourself to write. How to go through the world as a writer, finding and absorbing the material you will need. Because writing doesn’t come out of your head. Oh, if only it were so easy! No, writing comes out of other writing, and out of your lived experiences. If it comes only out of other writing, it’s merely imitative. If it comes only out of lived experiences, it’s often unformed, uninformed. Like a long diary entry, uninteresting to read. Good writing happens when you’ve absorbed a great many things, both from books and from life, and they’ve mixed pretty thoroughly in you, as though you were a cocktail shaker. And then you pour it out, into whatever form you’ve chosen or it’s chosen for itself (whether a poem, or short story, or novel).

So if you want to be a writer, give yourself homework: go out and observe.

This, by the way, is my copy of The Song of the Lark, from 1924.

December 22, 2014

Small Details

Details matter.

Once upon a time, a long time ago (specifically, while I was in college), I took a poetry class. It was my introduction to the fact that taking a class with a Famous Poet doesn’t mean it’s going to be any good (it wasn’t). And that’s where I first heard the phrase “God is in the details.” I’m not sure where I heard “The Devil is in the details,” which I suppose is a sort of companion phrase. They both essentially mean the same thing, which is that details matter. (In my poetry class, the professor meant that the poem is in the details, which is both true and not true. He was referring to the small descriptive details that are at the heart of modern free verse. But the poem is also in the details of rhythm and rhyme.)

I was thinking of this last night, because it was the first night in about two weeks when I haven’t been working (frantically trying to finish the tasks of the semester). And instead of going straight to sleep, which is of course what I should have done, I stayed up to sew cherry red bobbles on my lampshade. Because decorating is also in the details — if the details aren’t there, aren’t right, you haven’t decorated at all. You’re just arranged furniture.

There is a sort of rule that I’ve been hearing about, mostly from business people: since 20% of your effort goes into achieving 80% of a task, and the remaining 80% goes into achieving the final 20%, you should focus on achieving that first 80%. As for the rest, “the perfect is the enemy of the good,” right? I suppose there’s nothing wrong with thinking that way, or acting on it, in certain industries. But there are places where the difference between 80% and 100%, or even 90% if you can’t get all the way there, is huge. Is everything.

One of those places is the arts. The difference between an artist giving 80% and 100% is the work of art itself. You can tell a painting, a novel, that isn’t at 100%. Where the artist or writer said, “that’s good enough.” What makes an artist great is knowing where 100% is, and doing his or her best to get there. Maybe not achieving it — probably not achieving it, because who are we kidding, art is hard. But trying anyway.

When I’m decorating, I add the bobbles. (Which I love in part because they’re slightly ridiculous, as though my lampshades belonged at a circus. This morning, I added bobbles to the other lampshade. Now I have two lampshades with red bobbles, like circus clowns.) When I’m writing, I sweat over the commas and semicolons. The novel I’m writing — I’ve read the entire manuscript out loud to myself, to hear what the sentences sound like. Over the next few days, I need to go over it one more time before sending it to Important People. Just to make sure there aren’t any stupid mistakes.

As I said, I suppose there are places where 80% is enough, and you can let the other 20% go. But not the spaces I work in: not in teaching, not in writing. And it’s not a way that I particularly want to live, because I care about the details, about getting to 100%. And there’s another saying that I’ve always remembered: “The way you do one thing is the way you do everything.” I think that’s often true: people who are conscientious in one area tend to be conscientious in other areas as well. I know it’s true for me: the better I get at one thing, the better I get at others. It’s as though each thing I do is a learning process. Putting red bobbles on my lampshades provides a lesson about writing, about teaching. About living.

Because in the end it’s about how we live, isn’t it? In the end, everything is. And everything can provide lessons. Even time spent sewing on red bobbles . . .

The photo above is from this morning: some of my sewing supplies scattered on the daybed in the living room, where I was working. The cigarette tin holds needles, the tea tin holds buttons, and the old Altoids tin holds my pins. The photo below is one of my lampshades, the one next to the Christmas tree, with red bobbles.

December 18, 2014

Tidying Up

I read the most charming book, recently. It’s called The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up: The Japanese Art of Decluttering and Organizing, by Marie Kondo. The author is a television star in Japan, where she has a show in which she . . . you guessed it, goes to people’s houses and helps them organize their possessions. Helps them tidy up. After reading the book, I watched clips from several episodes on YouTube, in Japanese of course. A lot of what she does is talk to people, and I’m guessing that she’s asking them what they love, which of their possessions are truly important to them. Because Kondo has a different approach to tidying up, one I found interesting and valuable.

The book is charming in part because Kondo is so obsessive, much more than I could ever be. But I’m going to describe what I found valuable in her book, the ideas that stood out to me. Because I need order to work well — I need my environment to be tidy.

I know there have been articles on writers and how messy they can be. Some of them need mess, need disorder — they say within that disorder, they know where everything is. They get angry if anyone tries to tidy up. I’m not like that: I need my environment to be organized. I think it has to do with the way I think. My mind is itself a tidy place, or wants to be. It doesn’t like to be untidy, with important things tucked into the wrong places and forgotten. I do so much, have so many projects at once, that it’s really the only way I can operate. And one of the best ways to tidy my mind is to keep my physical environment clean, clearly organized. I don’t like inner or outer mess.

There are two other reasons I don’t like mess. One is that I need to live efficiently. I have so much to do that it’s frustrating when I have to spend time searching for a set of notes I knew I put somewhere. Or keys. Or change. If I’m working on a research project, I need to know which books I have relevant to that project, and where to find them. And second, I want to live in a beautiful space. Mess can be beautiful, but have you noticed that a beautiful mess is almost always intentional and intensely curated? Edward Gorey’s house was a beautiful mess, but he was an artist. It’s actually much more difficult to create a beautiful mess than simple neatness. So I try to keep things neat.

But I do fall into messiness sometimes, particularly when I don’t have time to clean. When I’m simply too busy.

So here are the central concepts from Kondo’s book that are particularly important to me:

1. You should only have things that bring you joy. This was a revelation, actually. What Kondo does, and I did not do this, is have people bring out all their possessions and put them on the floor. Then, she tells them to hold each one in their hands and decide whether that item brings them joy. If it doesn’t, it goes.

I thought I was being very practical by keeping things I had not worn for a long time, because I might need them again someday. But Kondo would say, while those things were useful to you once, they have outlived their usefulness. They are now ready to go away, wherever they’re supposed to go next. In a way, by keeping them, you’re impeding the flow of both your and their lives. Someone else could potentially use that coat. And then there are things that have outlived their usefulness entirely, and simply need to be thrown away. Old receipts don’t necessarily want to stay with you, to clutter up your drawers. They know when it’s time for them to move on, and so should you.

Did I mention that Kondo talks a fair amount about Shinto? It’s very clear that she believes all your things have spirit. If they’re no longer giving you joy, not only should they move on, they actually want to move on.

This prompted me to go through my closets and bookshelves. I try not to keep things I don’t love, but even I found things I was keeping that didn’t give me joy: some books I had bought because I felt as though I should read them, some clothes that were such a bargain at the time. I took several large bags to Goodwill.

2. Once you have discarded everything that doesn’t give you joy, make sure everything you’re keeping has its proper place. You should have a designated place for everything.

3. And you should make a habit of putting everything in its place. Now, this is difficult for me at the moment. Although I moved into this apartment six months ago, I’m still decorating. So there are paint cans on the kitchen counter, which is clearly not a place to store paint cans. (I just painted three lamps, and next come the shelves in what I glamorously call the walk-in closet, because you can walk into it, but is really a tiny room under the stairs, with a rod and drawers.) But I do try to make sure that whenever I take anything out of its place, I put it back. I notice that if it’s sitting out of place after I used it, I start to feel uncomfortable. This is partly Kondo’s fault: she makes me feel as though everything I own is sentient! As though my socks have feelings. (And how do I know they don’t?) Things like to be in their proper places, she says. And I know mine do.

There is a final concept in her book that I really like. She says that every day, when you enter your home, you should bow to it and thank it, and all the things in it, for taking care of you. For sheltering you, supporting you. Because after all, that’s what your things do, from socks to frying pans. I don’t actually bow down to my apartment (or at least not often!), but I like the idea of gratitude toward your things. That’s where the impulse to keep them neat, to take care of them back, ultimately comes from.

December 17, 2014

Heroine’s Journey: The Dark Forest

I don’t want to leave the Fairytale Heroine’s Journey for too long, because I don’t want to forget what I was writing. And anyway, I particularly want to talk about the dark forest. If you’re not sure what I’m talking about, take a look at my blog post “The Heroine’s Journey II“: it will explain what I’m doing.

And I have some good news! I’ve been asked to write an article about this idea of mine, about the Fairytale Heroine’s Journey. I won’t tell you where yet, until the article is written, submitted, and accepted. Then, of course, I’ll make an official announcement. But writing the article will help me develop my ideas.

So, let’s talk about dark forests!

This is one of the steps I described in the Fairytale Heroine’s Journey: “The heroine enters the dark forest.” There is a subset of fairy tales that is about the progress of a woman’s life. “Cinderella” belongs to it, as do “Snow White,” “Sleeping Beauty,” and “Vasilisa the Beautiful.” These are tales that show the heroine going on a journey, and that journey has certain steps. The steps are not always present, but they usually are. They do not always happen in the same order, and there are of course variations. As I wrote, I think of this as a meta-tale type, a structure that fits a number of the traditional Aarne-Thompson tale types. And one of those steps is entering the dark forest.

We see this in “Snow White” when she flees the huntsman: she must run though the forest. In “Sleeping Beauty,” as I pointed out, the forest grows up around her. We do not see the dark forest in Perrault’s “Cinderella,” but the forest actually comes to Cinderella in the Grimms’ version: she asks her father for the branch of a hazel tree, which she plants on her mother’s grave, and it showers gold and silver down on her in the form of the three dresses and dancing shoes. Most fairytales involving journeys have dark forests in them, for both a practical and a metaphorical reason. Practically, journeys used to involve dark forests: the tales I’m looking at are generally European, and there were dark forests between the villages, towns, and castles, the places of civilization. Going anywhere, even to grandmother’s house, meant going through the forest. And in the forest lurked dangers, such as wolves and wicked dwarves. But there is a metaphorical reason as well. The dark forest is an intuitive image for when we are lost, or possibly lost. It’s the place where we can lose our way and even ourselves.

For us, reading the fairy tales today, the dark forest functions as a metaphor for all the ways we get lost: anxiety, grief, depression. It’s where we can’t see ahead of us, where the trees are too dense. Where it’s too dark under the canopy. We look around and think, “Where am I going?” Or even, “Where is there to go? Is there a way out of here? Is there anything other than dark forest?”

There is, of course. There are kindly dwarves’ cottages, and huts on chicken legs, and castles ruled by white cats. You can get to those places, as long as you keep going. One thing fairy tales teach us is that there’s always a way out of the dark forest. Indeed, the dark forest often comes rather early in the tales. It’s an initial state of being lost. When you’re in the dark forest, most of the story is still to come.

There’s another thing I realized about the dark forest, when I was going through a small patch of it myself. (It was the forest of having a great deal of work to do, and too many deadlines, and not getting enough sleep.) At the time it came as such a revelation that I tweeted it, and so many people retweeted it that I realized it was something people needed to hear. It was this:

The heroine never dies in the dark forest.

Seriously, never. When you’re in the dark forest, you’re afraid. You feel as though it might be the end of the story: you might be lost forever. But it’s never the end of the story, and that’s another thing that fairy tales teach us. The dark forest is where you’re lost and afraid, but it’s not where you die. It’s only a part of the journey, not the whole of it. The dark forest has one power over you, which is the power to frighten you. But that’s it. And that realization can help you keep going.

I should say here that the heroine does die later, but in a fairy tale, death is a precursor to rebirth. Death is actually necessary for the heroine to become who she is. Sort of like the caterpillar becoming a butterfly.

So if you’re in a dark forest right now, and I bet some of you are, because patches of them can appear around any bend of the road, here’s what I want you to keep in mind:

1. You are a heroine.

2. You are on a journey, and on that journey, a number of things can happen.

3. One of those things is entering the dark forest. But other heroines have been on this journey before you, and they have something to teach you about the dark forest. Think of their journeys as maps that you can use for your own.

4. The heroine never dies in the dark forest.

5. The dark forest only has one power: to make you afraid. It’s all right to be afraid. But keep going, keep going.

6. On the other side of the dark forest are all sorts of adventures. You will have to share your loaf of bread with the birds. You will find a tree with golden apples. A talking snake will tell you what you need to know. You don’t know yet what those adventures will be. Keep going and find out.

(This is an illustration for “Cinderella” by Viktor P. Mohn.)

December 15, 2014

Daily Rituals

This morning, I read a blog post by the author Steven Barnes, who was a teacher of mine at Clarion, many years ago. Steve is also a personal coach, spiritual teacher, and martial artist: the sort of person who is always working on becoming a better version of himself, and teaching others how to become better as well. Here’s the post: “Your Life Is Not a ‘Lemon.'” And here’s the part of it that really struck me:

“You need to have a daily ritual of thought, movement, and emotion. Tell me your daily rituals, and I’ll tell you your life. Exercise daily and keep a food journal? That’s one body. No exercise and food unconsciousness? Another. Daily meditation and journaling? One psyche. Allowing the cess-river of daily news, political debate, human negativity and existential angst to flow over you unchallenged? That’s another. Daily checking your Mint.com account to see your finances and net worth? That’s one financial path. Inability to balance your check book? That’s another. Re-writing your goals daily and being crystal clear on what a perfect ‘today’ would be to implement them? That’s one life. Vague or no goals, and hoping for ‘luck’ to bring your dreams to you? That’s another. Daily focus on goals, actions, faith and gratitude? That’s one life. Rooting in the trough of our unfulfilled dreams, betrayals, failures, fears, guilt, blame and shame? That’s another.

“It isn’t fair that we have to take control. It isn’t un-fair. It just ‘is.’ Stand on the beach and scream at the waves that it is ‘unfair’ your shoes are getting wet. Or . . . back away. Or . . . take off your shoes and wiggle your toes in the wet sand.”

Basically, what Steve is getting at is that we can largely determine what our lives are like. Our lives are our daily lives: our experience of them is determined by the daily choices we make. And so we can make our lives good ones, healthy and happy and productive. Or we can make bad choices, and end up with unhealthy, unhappy, unproductive lives. It all depends on the small choices we make on a daily basis. Whether to exercise or not. Whether to eat the whole wheat turkey sandwich or the doughnut. Oh, not every choice has to be perfect! Not every choice can be. But our lives are better if most of our choices are good ones. And that happens if good choices are ingrained, and actually chosen automatically. If they are habits or rituals.

Steve talks about this as a way to deal with problems like depression, and I can speak to that, because I’ve been there. As readers of this blog know, I went through a period of serious depression when I was trying to finish my PhD dissertation. It was very difficult, but I eventually got out of it, with therapy and by building good habits. Now I try to maintain those habits, because I know that without them, I won’t be as healthy, either physically or mentally.

So what are my daily rituals? I have a healthy breakfast. Every day, I do twenty minutes of pilates, plus I walk a lot. Healthy lunch (cheese sandwich on whole wheat bread, apple), healthy snack (nuts, fruit, dark chocolate), healthy dinner (whole wheat pasta or brown rice with vegetables). Every day, time to rest and relax. All right, that last one I’m not as good at as I should be, and I definitely haven’t had enough sleep lately! I need to work on that. Also meditation. But the point is, the way you live on a daily basis affects the larger aspects of your life. The daily rituals are what keep me healthy. They are what allow me to be productive.

Some people say that when you’re depressed, you can’t do those things. That’s what depression is all about. But as someone who’s been there, I say that you can try, and you can start, and they will make you feel better. And for people who aren’t depressed, this is the way to have a good life: develop good daily rituals. These are the things that help me in particular:

1. Eat healthily.

2. Exercise daily.

3. At least once a day, do something that clears my head, that allows me to relax.

4. Keep my space neat and organized. Make my bed, do the dishes; if there is a mess, organize it.

5. Write, so the ideas don’t start clamoring around in my head.

6. Put a list of the larger things I want to accomplish up where I can see it. You know, the life things. Make sure that every day, I work on that list. That I’m accomplishing the larger things as well as the smaller ones.

7. Get some sleep. All right, no, I’m not as good at this one as I should be! But I’m working on it . . .

What are your daily rituals? It seems to me that most people don’t have good daily rituals; they live haphazardly. But you who read this blog — I bet you have them . . .

This is a picture of my Christmas tree. Just because it’s so pretty! It’s a yearly rather than a daily ritual, of course. But it ties me to the year, to time. I think our daily rituals do the same thing, actually. They make life more real for us . . .

December 14, 2014

Doing It All

I miss blogging.

I used to blog every day. And then I went to several times a week, and then recently I’ve barely blogged at all. It’s because I’ve been so busy. The problem with getting to do all the things you want to, is that you’re doing all the things. And there are still things I want to do that I don’t have time for.

So what am I doing? I have two wonderful academic positions, both of which I love: teaching writing to undergraduates at Boston University and in the Stonecoast MFA Program. This year, I finished a novel, so I am writing, even though it’s been a while since I’ve had a short story come out. I have almost enough short stories for the next short story collection; I mean, I have enough, but I want to write one more. And then I want to write the second novel, the sequel to the one I just finished.

I’m already into describing what I want to do, aren’t I? Instead of focusing on what I’m doing. The problem is that there doesn’t seem to be enough time. In these last few weeks in particular, finishing the academic semester, I’ve been exhausted, not sleeping enough and not eating very well. (I mean, I eat very healthily, or I wouldn’t be able to do what I do. But when I’m up past midnight, I get hungry again, and then I’m eating five meals a day. Like a Hobbit . . .)

So what is the problem exactly? I think it’s the sense that I’m doing so much for other people, and not doing all that much for myself. Not getting enough time to write, but also not getting to connect in the way I want to. In a way that blogging allows me to.

A friend of mine who is a writer once asked me why I do it, because it seemed to her as though it was taking time that I could be doing other work, like writing short stories. But blogging is easy for me, in a way writing short stories isn’t. It doesn’t take as much energy. And it allows me to get ideas out there, talk to people directly. I think I need that. I spend so much time talking as an authority on things. You know, I walk into a classroom and I’m the Professor. Or I’m advising a student on how to revise a story, a novel. Blogging is really the only place where I get to say, Here’s what confuses me. Here’s what my day is like. Here’s what I’m afraid of. (Failure and irrelevance, at the moment. Those are my particular fears.)

It’s the place where I get to speak without an editor.

I don’t know how much I can get back to it. There’s so much else I need to do. But I think that if I don’t get my ideas out, they get stuck in my head, and then it’s as though they’re all backed up, and they get snarled. I think I need a place to speak, and I think it needs to be public, because that’s who I am. It’s not enough for me to talk to friends. I’m a storyteller. Blogging is my way of telling the story of myself, and it allows me to get myself out of the way, so I can tell other stories as well.

Conclusion: I need a way to make sure that I’m writing. Otherwise, I get sick. I start to feel all wrong . . . And it’s important for me to write fiction, but when I can’t, blogging can fill that gap. It can keep me writing regularly, so I don’t feel as though I’ve somehow lost it . . . or lost myself. I need it the way I need to work out in the morning, or take a hot bath at the end of the day — because it keeps me healthy. I suppose the lesson here is that if you want to do it all, people will eventually let you. And then you will be doing it all, and you will go, all right, but I still need time for myself. Even if it’s writing a silly blog post!

This is me, on my way to class, on the last week of classes. With the first snowflakes of the season on my hat . . .