Theodora Goss's Blog, page 22

March 15, 2014

My Writing Life II

This past week, I read a blog post on Terri Windling’s blog: “Being Normal is Over-Rated.” In it, she quotes from the writer Dani Shapiro on the writing life:

“I need to live by certain rules in order to protect my writing life. When I was starting out, I didn’t understand this. A friend would call and ask me to lunch or, worse, breakfast, and I’d jump at the chance to get away from my desk for a couple of hours and join the world of real people eating real meals. I convinced myself that I had enough discipline to go out for a bit and then return to my desk, perhaps even invigorated and refreshed . . . and then, an hour or two later, I’d discover that my work day was over. . . .

“Our work requires us to adhere to certain rules — not because we’re rigid or self-absorbed as frustrated friends or family might secretly think — but because it’s the only way we can do it. If we are deep inside a story, we’re in another world — the world we’ve created — which, for the time being, is where we need to live if we are to make it real to ourselves and, ultimately, to others.

“I used to be angry with myself for my inability to live a normal life with normal rhythms and also be a writer. But I’ve come to believe that normal is over-rated — for artists, for everyone. When I was writing Devotion, all but the most essential tasks fell away. My hair got too long; I skipped my annual mammogram; the dogs’ nails went unclipped; the windows didn’t get cleaned; I lost touch with friends. But I took care of my family, and my book got written. That was all I could manage. . . .

“Be a good steward to your gift. This is the first sentence on a list I keep tacked to the bulletin board in my study, an impeccable set of instructions left by the poet Jane Kenyon.

* Protect your time.

* Feed your inner life.

* Avoid too much noise.

* Read good books, have good sentences in your ears.

* Be by yourself as often as you can.

* Walk.

* Take the phone off the hook.

* Work regular hours.

” . . . Cultivate solitude in your writing space, your car, at the kitchen table when the house is empty. Get your blood moving, get your feet on the earth. Your mind is not floating in space but connected to a body. Kenyon wrote this before the lure of the Internet became like crack cocaine for most writers so I would add, ‘Disable the Internet.’ Find a rhythm. This is wisdom from a poet who died too young. I never knew her but she has helped me as much as anyone I have ever known.”

I love this, but rather in the way I love a story about a place I may never visit or experience for myself. It’s a vicarious pleasure, a dream of a writing life so very different from mine. I wish I could have that life, where you can stop doing everything else and just concentrate on your writing. That’s not my life at all . . .

So what is my writing life? First, let’s be realistic. The number of people who get do to nothing but write is small. The number of people who get to do that because they make enough money from writing is vanishingly small. When you see a writer who just writes, there are four possible scenarios: the writer has inherited family money (this is a lot more common than you would think or than I thought possible); the writer is being supported by a spouse (again, very common); the writer is making money from writing, but his or her primary income comes from freelance writing, usually nonfiction for corporations, writing the corporations will own; and the writer makes enough money by writing only what he or she actually wants to write. That last scenario is very, very rare, statistically. So what do most writers do? Well, they work.

Writers work at all sorts of different things. And there seem to be two broad ways of thinking about what writers should do. One is that writers should work at something they don’t have to think about too much, that really is a day job, so they can leave it behind at the end of the day and write. The other is that writers should find a job that fits with their writing, that informs their writing — like, teaching writing. What you choose depends on your personality, of course — and also on the choices you have. I chose the second path, teaching writing. It was a choice I could make partly because I had spent long years in graduate school doing a PhD, because nowadays it’s very hard to find a teaching position without an MFA or PhD after your name. But also, I’m no good at doing things that I’m not invested in. I knew that the “just a day job” track wouldn’t work for me. And honestly, many of the writers on that track would very much like to get off it. Those sorts of jobs are often very hard work, not much fun, and badly paid. They do it for the same reason most writers work: rent, food.

I’m very happy with the choices I made: the PhD was the hardest thing I’ve ever done, but I love teaching. I actually have two teaching jobs: one at Boston University, where I teach undergraduates, and one at the Stonecoast MFA program, where I teach graduate students. It’s hard, intense work, and it does involve the same parts of my brain that write, so after a full day of teaching, it can be hard to sit down and write fiction. But I would not give up either of them. Still, it does mean that my writing life looks very, very different from Shapiro’s. What does it look like? Well, every day is different, but there’s preparing to teach classes, teaching classes, holding office hours, commenting on papers. Dealing with all the administrative things involved in teaching, such as writing letters of recommendations. For my work with MFA students, there’s mentoring students on their creative writing, guiding the preparation of senior theses, preparing for the twice-yearly intensive residencies where we workshop student manuscripts. It’s certainly not a day job (or I would not have been up until 3 a.m. last night doing it). I love it, but when do I write? Well, the answer is, whenever I can.

I write late at night after all the other work is done. On the weekends, I spend time with my daughter, and then when she’s asleep, I write. During the summers, when I’m only teaching at one program, I have more time. That has only been true of the last two summers: before, I was finishing my PhD, and had no time to do anything but work on my dissertation. But the last two summers, I’ve traveled and done research for the novel I’m currently writing. I know, it sounds so fancy: going to London for research. And it was, but also, I don’t think I could have written this novel without it. I’m almost done with a second draft, and it’s taken so long in part because I had to learn how to write a novel, this novel. And in part because I had so many other things to do.

I’ve tried to arrange the other parts of my life to support my writing life. That is, I’ve tried to simplify all the parts of my life that aren’t working or writing. I live in one of the most expensive cities in the world, but I do try to live as inexpensively as I can. When I spend money, it’s on food or books. I don’t have a television. I don’t eat out, unless it’s with my daughter. I splurge on a museum membership, the occasional ballet or concert, fancy coffee. Face cream, flowers. When I travel, it’s to conferences or for research. (Anyway, to be honest, for me the perfect vacation would be going somewhere to do research or write. Because that’s what I find interesting.) It’s a lovely, intense life — I wouldn’t trade it for anyone else’s, and I feel very lucky that I get to do what I do. But it can also be very tiring!

So, I’m going to give very different advice from Dani Shapiro. It won’t be applicable to every writer, but I think it will be applicable to a larger group. If you want to be a writer?

* Learn how to write whenever and wherever you can. Create a writing space for yourself. This is not an external space, but an internal space: where you can go in order to write, even if you’re in the middle of an airport. Breathe, go to your internal writing space, write.

* Work irregular hours: that is, if midnight to 2 a.m. is the time you have to write, write then. Try to get enough sleep. Try to eat enough food. Make sure your laundry is done. Accept that your life may be irregular. Accept that it may be irregular for a long time.

* Learn how to live a normal enough life that you can make money to pay rent and buy food. The normal enough life is the price of having a writing life. Writing is cheap, compared to being an opera singer. But you still need a roof over your head, a computer, paper and ink. Internet.

* Learn to live cheaply. If someday you make a great deal of money from your writing, you will have learned good spending habits: you can buy the cheapest castle in Scotland. Until then, learn how to shop at thrift stores, and tell yourself it’s more interesting, more charming, more chic to shop at thrift stores than in department stores. And it is, really.

* Forgive yourself for all the things you’re not going to do, for the email messages you’ll respond to weeks or months late, for the things people will ask you to write that you don’t have time for, the friends you can’t meet for coffee, not that particular week or month — for all the things that will be late (and they will be). Apologize and move on. You don’t have time for guilt.

* Keep writing. If you wait for the perfect conditions, they will never come. If you try to create the perfect conditions, you will probably fail. Learn to write under less than perfect conditions, under the most imperfect conditions. And keep writing.

(This is the writer at her desk. Writing.)

March 8, 2014

Defining The Lady Code

Some time ago, I wrote a blog post called “The Lady Code.” In it, I pointed out that there is still a “lady code,” an implicit code by which we determine whether or not a woman is a lady. This code dates back to at least the Victorian era: in Victorian novels, characters always seem to know, immediately, whether or not a woman is a lady “by her dress and manner.” (I don’t remember where those words come from, but most likely a Sherlock Holmes story?)

Here is what I wrote in my last blog post: “In American, we are raised with an implicit lady code, because we tend not to talk about social status. But upper-middle class girls are educated into it: they are taught what to wear, usually by their mothers. They are taught which skirts are too short, which shirts too tight. They are taught to signal their social status in coded ways.” I added, “So dressing, for a woman, is a complicated affair. When you look into your closet in the morning — and even before that, when you buy your clothes in a store or online — you are making a choice about what you want to communicate. You are speaking in a coded language. If you were raised by an upper-middle-class mother, you know the lady code. You are fluent in that particular language. You know that what you wear should vary depending on the occasion. You will not wear a cocktail dress to the ballet.”

I’ve wanted to write more about this topic for a while, because I’m fascinated by the various ways we communicate, including through clothes. And what I’ve wanted to focus on is that last bit: not wearing a cocktail dress to the ballet. In other words, the details of the code. You see, I was born in Europe, so a lot of the code, and how it applied in a modern American context, I had to figure out for myself. My mother was very strict about how I dressed, but her ideas came from her own mother, who was a lady in the old European sense. What I learned was very old-fashioned. How old-fashioned? As a child, I was taught to embroider, because that is what girl children learned . . . My grandmother told me that only gypsies wore earrings. That old-fashioned.

But I had to learn how to dress, and how dress codes operated, because I was trying to present myself as an educated, employable woman in modern America: first as a lawyer, and then as a professor. This post is about what I learned, how I think the code works: what upper-middle-class women teach their daughters, and what I will probably teach my own daughter. (Please note that in this post I am neither criticizing the code nor saying that anyone should follow it. I’ve rebelled against it plenty myself: when I was sixteen, I pierced my own ears, with safety pins. But the code exists, and we are judged by it. So I’m trying to understand it.) Here are some of its basic tenets:

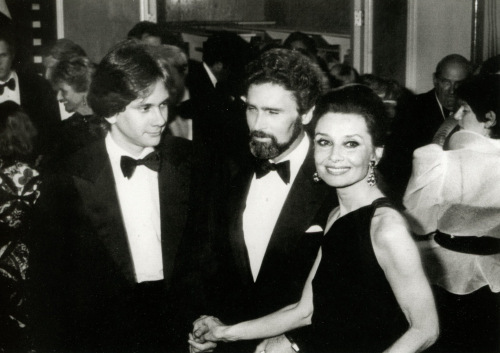

(The images in this blog post are all, obviously, of Audrey Hepburn. I chose them because she is such a perfect representative of the lady code, partly in how she was presented by Hollywood, but mostly in what she herself chose to wear. So I’ve selected photographs in which she at least seems to have been caught off guard, in her own clothes.)

1. Your clothing should be appropriate for the occasion. You actually find this explicitly stated in Agatha Christie stories, where Hercules Poirot has some wonderful pronouncements about what ladies do and don’t wear. A lady, he says, will always dress appropriately: she will not wear city clothes in the country or vice versa. I would say that dressing inappropriately for a particular context marks you as not understanding that context, whether it’s the ballet or, more importantly, a job interview. It signals that you don’t understand the code at work in the situation. What it sometimes means is that you don’t get the job, and that is, after all, the lady code’s most important ramification nowadays: it affects employment prospects. But more broadly, a woman who is what we call well-dressed will wear rain boots in the rain, flip-flops at the beach rather than on city streets. She will be dressed “appropriately.”

2. Your appearance, including makeup, should be “natural.” By “natural” I don’t mean natural: culturally, we actually think of a bare face, a face with no makeup on it, as a rebellion against social norms. (Which is ironic, since in the Victorian era, a woman wearing makeup would not be considered a lady. Oh, women did wear makeup, but it had to be so discreet as to be almost invisible. And never mentioned!) “Natural” means that you look like the cultural idea of natural: discreet makeup, hair a color that could be natural even though it’s probably not. Nails neatly trimmed but either unpainted or, if painted, a light color that looks, at first glance, like a natural nail. No obvious tattoos. (Tattoos on women have become more accepted recently. But socially, they are still judged. They will still affect important aspects of one’s life, such as job prospects. They remain markers of social class.)

3. Your jewelry and other accessories should be discreet. When I was an undergraduate at the University of Virginia, where the lady code was simply what most undergraduate women wore most days, I heard a boy from a small Southern town say that a woman should never wear more than five pieces of jewelry. He gave as an example a watch, two earrings, a ring, and a bracelet. And I still remember an article in which Miss Manners (remember Miss Manners?) was asked where it was appropriate to wear an anklet (remember anklets?). She said: on the wrist, where it is called a bracelet. Coco Chanel popularized long ropes of fake pearls, but she was a fashion designer, and a lady is not fashionable. She has style, which is a different thing altogether. Fashion stands out: style is discreet and understated. At UVA, all the undergraduate women seemed to wear a single strand of real pearls, perhaps because they had all gotten one when they turned sixteen. I did myself, as my sixteenth birthday present . . .

4. This is a complicated one: you should look feminine but not sexual. Got that? This is one of the reasons the lady code is so often criticized: it’s nuanced and complicated. And it can be used to shame women: I still remember being at a funeral at a small town in the South and hearing two women talk about a third, who had worn a black suit that had obviously not been meant for a funeral. The fit was too tight, and it showed cleavage. It was sexy. I remember that it was worn with very high stiletto heels . . . On the other hand, one thing I find useful about the code, myself, is that when I dress according to it, my body becomes functionally invisible. I am seen as a teacher or lawyer, not as a potentially sexual woman. I am not hit on . . . So the code cuts both ways, and I suppose that’s why it’s survived. It is, in one sense, a means of social control. But in another, it’s a way that women have controlled how they are perceived. And by the way, skirt length? Between the lower calf and just above the knee. Anything shorter is perceived as sexual; anything longer is perceived as properly for evening.

5. You should have style, but not be fashionable, and your clothing should signal quality, even if you bought it at Goodwill. About half of my closet comes from Goodwill . . . This is a complicated one too, isn’t it? And men wonder why women have so many clothes! By fashionable, I mean whatever is “in” this season. I teach at a very fashionable university, and I still remember the semester every undergraduate woman wore culottes. It was the semester of the culottes. By next semester, the culottes were gone, and my fashionable undergraduates would not have been caught dead in them. Dressing stylishly means dressing in a way that is timeless, and by timeless I mean in a style that has lasted for at least ten years. (That’s now long timeless is in fashion.) A white blouse, slim jeans, ballet flats, and patterned scarf would have been as appropriate on Audrey Hepburn as they are now. Another of Hercules Poirot’s wonderful statements is that whatever else she may look like, a lady will wear good quality shoes. (He solves a case because a woman pretending to be Lady Somebody is wearing cheap shoes. I kid you not.) This, by the way, is part of the reason jewelry should be discreet: because unless you are the Queen of England or Elizabeth Taylor, large jewelry inevitably looks fake, even when it’s not. Small jewelry looks real, even when it’s not. And quality is often tied to the idea of authenticity: real linen, real leather, real pearls.

I think that’s enough for now, and do realize that this list is a work in progress. It is my attempt to figure out how this language of clothes works, how we perceive dress. There are all sorts of codes — for different disciplines, for example, so that a female scientist will be expected to dress a particular way, which is different from a female elementary school teacher, and different from a female lawyer. But the lady code is a fairly broad, underlying social code that has a lot to do with how women are judged in our culture, which is why I wanted to explore it in more detail. How do I dress? Mostly the way I’ve described above, although my clothes are a little more bohemian, because they’re allowed to be. I’m a writer and a professor. I get to be a little artsy. But I do have to be conscious about how I’m perceived, because I’m often “on”: for students, colleagues, readers.

There’s a lot more to say about the above. Dress codes can operate in very different ways depending on race, social class, and other factors, and those are certainly worth exploring, although I haven’t said anything about them here. And there are people who can afford to ignore dress codes altogether. They tend to be the wealthy, who don’t need to work, or people who work in ways that give them a great deal of independence in defining their own looks, although they often have codes of their own. If you are a tattoo artist, you’d better have tattoos, and they’d better be good ones. Very few of us exist outside of these codes altogether, just as very few of us exist outside language. They are ways we communicate, sometimes deliberately, sometimes inadvertently. Which is part of what makes them so fascinating . . .

(And if you want to know whether something you’re planning on wearing is “ladylike”? Ask yourself if Audrey Hepburn would wear it. I think that’s a pretty reliable test . . .)

March 1, 2014

Feeling Alive

When I first read this quotation from Joseph Campbell, I thought he must be wrong:

“I don’t believe people are looking for the meaning of life as much as they are for the experience of being alive.”

Many years ago, I had read Victor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning, in which he says that what we need in life, most of all, is a sense of its meaning, of it being meaningful. And I believed him. I still do, but I think what Campbell says is true as well, in an even more fundamental and primary way.

We search for life’s meaning as intellectual beings, who reflect on our own state. But reflection is secondary: it’s us looking at our own lives, almost as though we stood outside them, and trying to locate a meaning in them. We do that in particular if we have suffered greatly, as Frankl (a concentration camp survivor) had. Finding meaning helps us — to deal with life’s intensity, its unpredictability, even if we have not suffered like Frankl.

But before we are intellectual beings, we are sensual beings, who experience the world by sensing, feeling. And before we look for meaning, we look for the experience of being alive, of feeling the intensity and unpredictability of life. We seek to participate in life itself.

We all want to feel alive.

Why am I making this point? Because it occurred to me, the other day, that we will do almost anything to feel fully alive, even if it hurts us in the process. It doesn’t have to hurt us: the need to feel alive makes us climb mountains, write books. It can result in exploration and adventure and art. So it’s a wonderful thing, a valuable thing. An intensely human thing. But like anything human, it can also cause harm. Recently, I read an article by a drug addict in which he described the need for a high as the need to feel fully and intensely alive — something he could not find in his ordinary life, even though he is a famous performer. It led me to wonder if many of our destructive behaviors could be caused by that perfectly natural need, and our inability to fulfill it in any other way. I don’t have many destructive habits: perhaps my tendency to overwork is the worse of them. That’s a behavior the world rewards, although it can be quite bad for me personally. It means that I sometimes collapse from tiredness, or miss out on aspects of life that could be rewarding. I don’t remember when I last kept up with a television show. But the work I do, both teaching and writing, makes me feel intensely alive, so it’s hard to rest. And I remember that when I was younger and did particularly stupid things (anything involving alcohol and dancing on tables, for instance), it was usually because I needed to feel alive, to feel a certain intensity that’s much easier for me to experience now, when I have more control over my own life. And when I have art.

I think art is probably the safest way to feel fully alive.

Experiencing art, by going to a concert or museum, makes us feel more intensely. But the true intensity comes from creating art. Even sitting here, writing this blog post, putting the words together while listening to Bach (which is what I’m doing), has a certain intensity to it. And then what I write will go out into the world, and you will either like it or not, find it relevant to you or not. There’s a risk in that, and the risk is fundamental to the intensity of the experience. We can’t feel fully alive without taking risks. That’s why climbing a mountain and writing a book will make us feel alive — they are different kinds of risks, but to both of them, we bring the totality of ourselves. We have to commit ourselves to the task. And that’s another component of feeling alive.

An idea is developing as I write this, about what it takes to feel fully alive. You commit yourself to something risky, something that feels greater than yourself. Like moving to Tokyo. (A friend of mine is currently living in Tokyo for several months, and I love to see the pictures she posts on social media. It allows me to participate in her adventures vicariously. But it would make me feel envious if I did not know that in June, I will be abroad myself, in Budapest for a month.) Like learning to play Bach on the cello. Something with a real possibility of failure. And then you do it, and see what happens. Perhaps we all need suspense in our lives, not just in novels . . . To feel fully alive, we need to feel as though we could fail. Isn’t that ironic? Because at the same time, we hate to fail, don’t we? We hate to fall, to make mistakes. And yet, so many of us, if our lives are too safe, if they are too ordinary, will long for something to take us out of ordinary safety. We will say, let’s move to Tokyo.

We need risk and the possibility of failure in order to feel alive, and we need to find meaning in life in order to deal with risk and failure. Imagine Campbell and Frankl dancing a waltz . . .

I write this in part because there’s been a sort of backlash recently against the Campbellian message that we should all follow our bliss. There are people who say, following your bliss can lead to failure. It can be more sensible to lead a good, ordinary life. And it can. But if I weren’t following my particular bliss? If I weren’t risking failure? I’m not sure what I would do. No, I do know, because I remember being a lawyer, and what that was like. I had made the safe decision, the sensible decision from a financial standpoint. And I felt dead. I went to the same office every day, I did work for clients that in many cases I did not respect. And I was not healthy, physically or mentally. I can understand how, under those circumstances, someone would turn to destructive behaviors, simply to feel alive. I think what Campbell means by following your bliss is this: do what makes you feel fully alive.

And if you’re not sure what that is, if you’re still searching for something to bring you to life? I recommend art.

(These are the flowers I bought this week. Today, the branches are sprouting leaves. They are coming to life . . . You can also feel alive by experiencing ordinary life more intensely — by going out into a forest and feeling the trees around you, by walking down the streets of a great city and feeling it surging with life. That comes with its own kind of risk, which is riskier in some ways than moving to Tokyo, because it involves an engagement with and descent into the self. But more on that another day.)

February 22, 2014

Being a Soulmate

I’ve been thinking about the idea of a soulmate, because I’ve seen friends who are in relationships, and friends who are not in relationships but searching for romantic partners. The idea of a soulmate is central to our idea of relationships now, isn’t it? That’s what we are all searching for, a soul mate, a partner who shares something with us that is of the soul, that goes to the core of who we are. I’ve seen friends who are convinced they are with their soulmates, and friends who are trying to find theirs . . .

And it seems to me that we’re thinking about the concept in the wrong way.

The goal shouldn’t be to find a soulmate. It should be to actually be a soulmate. And I think a soulmate is not necessarily a romantic partner. It’s anyone with whom you have a deep connection, and it can be a parent, a friend, a child . . . We need soulmates, and we need lots of them, but the best way to have soulmates is to be a soulmate, meaning to be the sort of person who is a soulmate to other people. Which is something you can practice.

So what does it mean to be a soulmate? Think about what we want from our romantic partners: we want to be understood, and then we want to be loved for who we are. A soulmate makes us less lonely, and there is a sense in which we are all alone: we all perceive the world from within our individual bodies, with our individual consciousness. As soon as you close your eyes, you are alone in the dark. A soulmate offers connection, and support, and understanding. A soulmate offers love. But it’s love that comes from and reflects that deep connection: the soulmate loves you for and because of who you are. This is why I say a soulmate can be a parent, friend, a child. A soulmate can even be an animal. (Those who have deeply loved and been understood by a cat or dog will know what I mean.)

One way to make your life rich and wonderful is to have soul mates, and lots of them. But by lots, I don’t mean hundreds, because I think that’s impossible. You can’t connect that deeply with so many people. If you have two, or five, or ten, you’re doing well. What you want to do, of course, is be a good soulmate to them, to give them the love and understanding, the support, that you want yourself. (I should say, here, that being a soulmate is a reciprocal relationship. If you’re not getting that love and understanding back, it’s not a soulmate relationship, but something else. Obviously, what you get back will depend on the person in the relationship, and will change over time: a relationship with a child is not like one with a friend or parent. But the bond will be reciprocal.)

To have soulmates, you need to be a soulmate, and that takes practice. None of us is a soulmate naturally: we need to learn how. The best way to learn, the way you can always practice, is to be a soulmate to the one person you should always treat with love and understanding: yourself. You need to be your own soulmate.

There are several reasons you should be your own soulmate. First, because you’re handy: you will always be there to practice on. Second, because you need love and understanding and support, right? And there will be times when other people can’t give you those things, so you should be able to give them to yourself. And finally, because in our culture, we put such emphasis on finding a soulmate, by which we mean a romantic partner, and then we expect that partner to be our only soulmate, to be the person who gives us all the support and connection we need. Which is way too much of a burden to put on a romantic relationship, or on one person in general. We expect a partner to complete us, without realizing that we need to complete ourselves, so we can bring a complete person to the relationship. And, indeed, to all our relationships.

So, how do you go about being your own soulmate? Well, you can start by making a list of all the things you want from a soulmate. And then, systematically, figuring out how to supply those things for yourself. I was thinking about the things we typically want from relationships: things like love, and a home, and security. Adventure. The impetus to grow and become more of what we should be, more of ourselves. Those are the things we need to provide for ourselves. It’s only when we can provide them for ourselves that we can truly share them with other people: it’s only when you know how to go off on adventures that you can invite others on them. You can’t wait for other people to be the source of your adventures, or your security, or personal growth. If you can’t create a home for yourself, it’s very difficult to have one with another person.

Because here’s the thing: if you don’t love yourself enough, no one else is going to be able to love you enough to make up for that absence. No one else can fill up that particular abyss.

It’s dangerous to approach relationships, particularly romantic relationships, with that sense of need, to expect a romantic partner to supply what you can’t supply yourself. The danger is, in part, that you will get into or stay in a relationship that is unhealthy, simply because a relationship of any sort is better than no relationship at all. But an unhappy relationship, potentially even an abusive relationships, is worse.

On the other hand, a relationship in which two people can be their own soulmates, and also soulmates for each other: that’s the ideal, isn’t it? That’s when you can be a parent without expecting your child to fulfill your dreams, because you’ve fulfilled them yourself. Be a friend without expecting your friends to resemble you or agree with all your opinions, because why should they? Loving them as they are. And that’s when you can be in a romantic relationship without expecting your partner to supply what you lack, because you can do that yourself. So you can truly be partners, together because you want to be. The bonus of being in a romantic relationship is that you can practice being a soulmate to yourself and your partner at the same time. But you should never neglect being a soulmate to yourself.

This is a photograph of my paperwhites in full bloom. Outside, the ground is still covered with snow, but inside, I have created my own spring . . .

(One word of caution. By saying that you should practice being a soulmate, I am not at all implying that you should be or stay in relationships that are one-sided, in which you are supplying all the soulmate-ness. One reason to be your own soulmate is so you won’t get into those sorts of relationships. Soulmate relationships are always reciprocal. If you are good at being a soulmate, you will find that people want to be your soulmate, will actively seek you out for that purpose. And some of them will be soulmate material, but others won’t — they will be coming to you out of their own need for affirmation, their own sense of lack. But you won’t be able to help them: you can’t supply for other people what they can’t supply for themselves. They will also need to learn how to be their own soulmates. That’s the work we all need to do, for and by ourselves . . .)

February 16, 2014

Your Fairy Tale Name

As you may know, I teach a class on fairy tales. In my class recently, we were talking about names in fairy tales. Very few characters in fairy tales have ordinary names: they are almost never Ann or Michael. Their names mean something: Snow White is as white as snow, Cinderella has to sleep among the cinders. Blue Beard is frightening because of his blue beard, which is as unnatural as his propensity to kill his wives. Puss in Boots is distinguished by his footwear. Their names are attributes. Or their names can be nonsense words that are also codes, that don’t mean anything but also mean your freedom: Rumplestiltskin, for example. Many fairy tale characters don’t even have names: they are the Prince or the Miller’s Daughter.

If I were just a professor, I would go on about the meaning and function of fairy tale names. But I’m also a writer, so I’ve created a way for you (yes, you) to find your own fairy tale name. What would you be named if you were in a fairy tale? Take this short quiz to find out:

(Illustration for “Cinderella” by Margaret Evans Price.)

1. Are you a man, a woman, or an animal? If you are a man, go to question 2. If you are a woman, go to question 8. If you are an animal, go to question 15.

2. If you are a man, are you good, evil, or morally ambiguous? If you are good, go to question 3. If you are evil, go to question 4. If you are morally ambiguous, go to question 7.

3. If you are a good man, your name is “Prince” + [your best character trait]. Ex. Prince Organized.

4. If you are an evil man, do you have magical powers? If you do, go to question 5. If you don’t, go to question 6.

5. If you are an evil, magical man, your name is “The Wizard of” [where you live]. Ex. The Wizard of Portland.

6. If you are an evil man but not magical, your name is [your name] + “the Ogre” or “the Troll” (your choice). Ex. Sidney the Ogre.

7. If you are a morally ambiguous man, take your name and scramble the letters to form a nonsense word. Ex. Nathajon. (Try not to steal any children. It never pays.)

8. Are you a good, evil, or morally ambiguous woman? If you are good, go to question 9. If you are evil, go to question 13. If you are morally ambiguous, go to question 14. If you are descended from fairies, go directly to question 22.

9. If you are a good woman, do you define yourself by your best character trait, your best physical feature, or the challenges you have overcome? If by your best character trait, go to question 10. If by your best physical feature, go to question 11. If by your challenges, go to question 12.

10. If you are a good woman and define yourself by your best character trait, your name is [that character trait]. Ex. Patience. (Be prepared to demonstrate that character trait throughout the tale.)

11. If you are a good woman and define yourself by your best physical attribute, your name is [the best thing about that attribute] + [that attribute]. Ex. Sparkling Eyes.

12. If you are a good woman and define yourself by the challenges you have overcome, your name is [your most difficult challenge] – any final vowel + “ella.” Ex. Insomniella. Alternatively, if you have a distinctive article of clothing, you may choose to identify yourself by that article. Ex. Blue Wool Coat.

13. If you are an evil woman, your name is “The Wicked” + [your job]. Ex. The Wicked Accountant. (Watch out for red hot iron shoes.)

14. If you are a morally ambiguous woman, your name is [your favorite natural phenomenon] + [the color of that phenomenon]. Ex. Sleet Gray.

15. If you are an animal, are you really an animal, or are you enchanted? If you are really an animal, go to question 16. If you’re actually enchanted, go to question 19.

16. If you are really an animal, are you good or morally ambiguous? If you are good, go to question 17. If you are morally ambiguous, go to question 18.

17. If you are a good animal, your name is “Good” + [your name]. Ex. Good Jennifer. (You will probably have your head chopped off by the end of the story, but everyone else will live happily ever after.)

18. If you are a morally ambiguous animal, your name is [your favorite animal] + “in” + [your favorite article of clothing]. Ex. Kangaroo in Pajamas.

19. If you are enchanted, are you an enchanted man or woman? If you are an enchanted man, go to question 20. If you are an enchanted woman, go to question 21.

20. If you are an enchanted man, your name is [your name] + “my” + [you favorite animal]. Ex. Andrew my Aardvark. (You will spend the tale trying to find a woman to disenchant you.) Alternatively, you could choose to be called “The” + [your favorite animal] + “Prince.” Ex. The Llama Prince.

21. If you are an enchanted woman, your name is [your name] – any final vowels + “ette” (if good) or “ile” (if evil). Ex. Amandette, Amandile. (By the end of the tale, you will have caused the Prince’s death. These things happen . . .)

22. If you are descended from fairies, your name is [color of your favorite flower] + [name of that flower]. Ex. White Lily.

Now that you have your fairy tale name, you’re ready to take your part in a fairy tale. Good luck! I hope you survive . . .

(Illustration for “The Frog Prince” by Mabel Lucie Attwell.)

February 9, 2014

Becoming That Woman

When I was growing up, when I was a teenager and then in my twenties, I had an image in my mind, of a woman. She was a woman I could never become, because she was so much more sophisticated than I was. She was the sort of woman who walked around European cities, with a scarf wrapped around her neck. She negotiated her way in English and probably French and who knew what other languages. She was beautiful and accomplished: she had done things and she knew it, and out of that came her confidence, her ability to walk through strange cities with a mysterious smile on her face. Looking as though she belonged, wherever she was in the world.

Yeah, you hate her too, right?

Hate is the wrong word. I never hated her: what I did was envy her. I would have wanted to become her, except that it seemed so impossible. She was so different than I was. Because I was . . . well, awkward, and unsure of my place in the world, and often scared. I felt as though I had no idea what I was doing, as though I was an alien or an imposter pretending all the time. You probably know what I’m talking about, because we’ve all been there. But I kept on doing what I was doing, kept on working and writing. Because this is life, and what else are we supposed to do? I finished things, as one does: poems, stories, degrees. So I published, and put my diplomas on the walls, and even won some awards. Oh, and I bought some smashing clothes, mostly in thrift stores because that was where I could afford to shop. And I taught classes.

One day, a student of mine asked to interview me for a sociology project. She was supposed to interview someone who was doing creative work of some sort. And one of her questions was, “Where did you get your style?” I stared at her and asked, “My what?” I think it was that day I started realizing something that has startled me ever since, that startles me all the time: somehow, I’m not entirely sure how, I had become That Woman.

This is a picture of me from last summer, in Brussels. Very consciously being That Woman! Because there I was, realizing that I was in Brussels, speaking (broken) French, buying sandwiches on baguettes, walking around the city and going to museums. And thinking, Yeah! I’m her . . .

(I bought the scarf at a small store in London, the skirt at a thrift shop in Budapest.)

I think those of us who are women all have a “That Woman,” the woman we don’t think we can become. And I guess what I want to say is, says who? You, that’s who. You say you can’t become her. And so you envy her, whenever you see her walking around a city or along a beach, or climbing a mountain, or whatever your That Woman does, because all of ours are different. (I don’t know if men have a That Man? It would be interesting to find out.) But, of course, you can.

I don’t think you become her by setting out to. You don’t say to yourself, I’m going to become That Woman, and go out to buy the right clothes. For one thing, you’ll get it wrong, because you probably don’t understand her yet. Your That Woman is a projection of what is deeply, truly inside you, the woman you could become (which is why you envy her, for being what you so want to be). So the way to get to her is to find what is deeply, truly in you, and keep doing it. While you feel awkward and inadequate, while you’re afraid. If it’s writing, go sit at your desk or in a coffee shop and write. If you want to go back to school, do that. Buy the clothes you really love (I still recommend thrift stores, which is where I get most of mine). Do the things you genuinely love to do. When you do that, over and over, you slowly start to become her. And it is in the process of becoming her that you understand who she is.

The hardest thing about this process is overcoming your own negative emotions: your fears and feelings of inadequacy. The thing to remember about emotions is that they’re only emotions. You can feel them without acting on them. So be afraid, but do what you want to anyway. Separate out your feelings and actions. Feel your feelings, but pay attention to your actions.

(This is me reflected in a mirror in front of the Magritte Museum, which is my favorite museum in Brussels. I was so glad to have gone to Brussels, simply to see this museum.)

I have two stickies over my desk about fear. They are on my cork board, where I can see them every day.

What would you do if you weren’t afraid?

Everything you want is on the other side of fear.

They work together, don’t they? Perhaps because I’m a writer, I think it’s useful to write things like this out. When I do, I find it’s easier for me to remember them, to live them. They become my inner voice, the voice that speaks when I need it to, that guides me. That inner voice speaks to all of us, and it often seems as though it speaks from outside, as though it’s the voice of another. But of course it’s not: the inner voice is your own voice, although it often repeats what others have told you. That you can’t, that you’re not good enough. But you can take control of that inner voice, you can change what it says. You do that not directly, because you can’t argue with the subconscious, but slantwise. Like by putting stickies over your desk.

Now that I am That Woman, there are some things I know about her. I’ll let you in on those secrets:

1. Before she became That Woman, she was not That Woman. She thought she could never become That Woman, until she did. She spent a long time being scared, feeling awkward and inadequate. And then one day, she found herself walking through Brussels in a swingy skirt and leopard print flats, with a scarf tossed carelessly around her neck. On that day, or another, she realized that she had become That Woman.

2. Some days, when she wakes up in the morning, she groans and crawls back under the blankets. You might think, Aha, she’s not That Woman all the time! But you’re wrong: groaning and crawling back under the blankets are part of being That Woman. It’s all part of the package. Later that day, she will walk to a cafe and work on a poem, or go to a museum, or just dreamily watch the snow come down outside her window. She will be That Woman, whatever she’s doing.

3. What defines her as That Woman is that she knows she is. She knows she’s the woman she wanted to be, or is well on her way to getting there. She looks at herself in the mirror and says “Yes.” She looks at her life and says, “This is what I wanted to do, and I’m doing it.” Her fundamental attitude toward herself and her own life will be love. Oh, some days she will be tired, and frustrated, and overworked! But underneath, there will be gratitude and joy.

Last picture: me on a park bench in Brussels, that same day. See? I wasn’t kidding about the leopard print flats . . .

February 2, 2014

After Depression

If you’ve been reading this blog or following my work for a while, you know that about two years ago, I went through a period of depression. It lasted a long time, or what is a long time for me — about a year. It happened while I was finishing my PhD dissertation, and was very much linked to that, I think. A PhD dissertation is one of the most difficult things you can do, sort of like climbing an intellectual Mount Everest with a committee both coaching you along the way and judging your form as you do it.

At the time, I dealt with it by going into therapy, meeting with a therapist once a week. That was a good way to handle the depression, I think. I never took anything for it, which may have been a mistake. Perhaps it would have gone away more quickly, or not hit as hard, if I had been on the right medication. I don’t know. As I finished my dissertation, and particularly after I defended, it slowly went away. I could feel it going away. While you’re depressed, you can’t really feel the depression — it’s your normal. You just feel as though you’re in the darkness, all the time. I used to call it the Shadowlands, and visualize it as an underground place where everything was dark and flat, as though the world were made up of silhouettes. I wrote about it, mostly on this blog, because writing is one of the ways I deal with things. And of course because one of my jobs as a writer is to talk about what I’m experiencing, on the chance that it may help someone else experiencing the same thing. It probably will — we are all human, we experience mostly the same things.

It was only when I started getting better, getting through and over it, that I could feel it — as a sort of dark cloud that hovered over me, and then near me, and then went away. I would tell my therapist, “It’s about three feet away now.” Recently, I realized that the cloud was nowhere near me, and hadn’t been for a year. So this is a post on what happens after depression. On where you find yourself once you’ve gotten over it, and what you do there.

Honestly, this isn’t the best morning for me to be writing a post like this one, because I was up very late last night. I had to buy an airplane ticket to a conference, and spent an hour trying to figure out the cheapest option, and even then it was very expensive, which is always stressful for me. And then I stayed up even later revising a couple of paragraphs in the novel. That felt good — the paragraphs are better now. But as I was doing it, I knew that I would be tired the next day. And tiredness isn’t good for me. You see, once you’ve been through depression, there are some things you know about yourself: (a) you could get it again, and (b) to avoid it, you have to take care of yourself.

So this is really a post about self-care. Before I talk about that, let me add a third thing you know about yourself: (c) you’re stronger now, stronger than you were before, but also more vulnerable. You’re like a reed that can bend with the wind. You weren’t destroyed by it, and you know that you’re not going to be destroyed. But you also know the wind can return.

(Paperwhites growing on my windowsill.)

So, what happens after depression? Well, the first thing is that after a while, you start to experience joy. I use that word deliberately. It’s not happiness, although you can be happy too — but happiness is a fleeting thing, something you can feel for a little while. Joy is deeper. It’s an inner peace and contentment and delight, based on nothing at all but life itself — the experience of being alive. You feel joy because your oatmeal tastes good, with milk and raisins and brown sugar, and because it’s cold outside and the sky is a clear gray, and because you have a warm blanket to wrap yourself in and a book to read. Joy is based on such little things, on breathing itself. The second thing is that you realize how important it is to take care of yourself. Here are the things I do, after depression:

1. I’m careful about what and when I eat. I eat whole grains, and lean proteins, and lots of vegetables and fruit. I give myself regular treats, usually chocolate. I make sure that I’m eating regularly throughout the day, small meals so I can keep up my energy. I never let myself become hungry and drained. And I make sure that my food is delicious, because if it isn’t, why eat it?

2. I exercise. Mostly, I get out and walk, long walks, even when it’s cold. Not just to walk, because that would bore me. (I’m rather easily bored.) I walk to buy groceries, or to the bookstore, or to my favorite thrift store to look at clothes. Walking around with a camera also gives me something to do. I can take pictures and post them later. I also do yoga and pilates, because moving makes me feel good, and being flexible makes me feel good.

3. I get more sleep. Not enough, I’m afraid, but what I’ve noticed is that getting too little sleep is one of the worst things I can do for myself. It starts a cycle, in which I eat too much and the wrong things, because I have to get energy from somewhere and if it’s not from sleep then it’s from food, and I’m too tired to exercise. Getting more sleep is at the top of my to-do list.

(A print I matted and framed myself.)

4. I prioritize my own work. This is difficult, because I have so much work to do: work I have to do, because it’s what I’m actually paid for, and then work people ask me to do, like write papers. And I simply can’t do it all. So I make sure that I do my own work, which means my writing — I make sure I’m writing every day. Which, of course, is why I was up too late last night. But if I don’t do that, I feel terrible for neglecting what is most important to me. It is, in a very real sense, like neglecting myself.

5. I give myself a regular diet of treats. Bubble baths, good books, cupcakes. You need to treat yourself well. You can’t control what goes on out in the world, how other people treat you. (People treat me very well, by the way. But most people want things from me, because after all I am a provider of things — help with papers, recommendations, advice. They want me to give talks and chair panels, both of which I will be doing next week. Write poems — I will need to finish a poem this weekend.) I have a sticky over my desk on which I’ve written, “Are you loving yourself?” When I’m not treating myself very well, I remind myself of this — that I must love myself, and love is a verb as well as a noun. It’s an action. And then I go buy myself lipstick or watch an episode of Dracula.

(A vase I bought at a thrift store.)

6. I go for beauty. I try to make my space as beautiful as I can, which also means that it should be neat and clean. I don’t always get to neat . . . But right now I have a vase filled with daffodils and yellow tulips on my dining table, and I’ve been framing some of the art I have so there’s more art on the walls. And as often as I can, I go to the museums or to hear a concert. I’m going to a concert today, actually. Beauty is therapeutic. Oscar Wilde once wrote, “Nothing can cure the soul but the senses, just as nothing can cure the senses but the soul.” I treat this as excellent medical advice, and listen to Dr. Wilde. To cure my soul, I engage the senses.

7. I reach out. It’s so easy, when you’re depressed, to curl in on yourself, and you may need to do that in the midst of depression. I certainly needed to — if I were a turtle, I would have crawled inside my shell. Perhaps a better image is the caterpillar inside its chrysalis. I needed some sort of covering, so I could change and emerge. Sometimes I just crawled under my blanket . . . But now I need to reach out, see people. Of course, I see people all the time, because I teach — I’m in constant contact. But the difficulty for me is to be in contact in a way that doesn’t involve responsibility, that is purely social. So I try to keep in touch with friends, make a point of traveling to new places even when it’s expensive. Yesterday, I bought a new suitcase! And I make a point of being on social media, because that’s a way of keeping in touch too.

8. Finally, and this is the last thing I’ll list although I’m sure there are also others, I let go. There are things I just can’t do — I can’t say yes to every request, lately I haven’t even been able to answer every email, and I have such a backlog of Facebook messages! This makes me feel guilty, but I can’t do anything about it. There simply isn’t enough time. I have to do what I can and let the rest go, feel guilty about it if I need to, but if I tried to do it all, I would be there again, in the space where there is no joy and no light.

And my life, right now, is filled with joy and light. It surprised me, really — that I should feel those things, and perhaps more powerfully than I ever have. How lovely it is, how lucky I feel simply to be me, to be able to do the things I do, have the things I have. To inhabit my own brain, which is a constant source of stories.

So there you have it: (a) eat right, (b) exercise, (c) sleep, (d) do YOUR work, (e) treat yourself, (f) go for beauty, (g) reach out, (h) let go. And find joy.

(Dressed for a concert.)

January 25, 2014

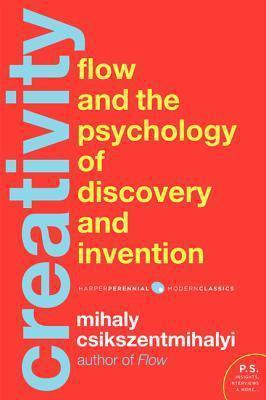

Being an Artist

I’ve been reading Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s book Creativity: The Psychology of Discovery and Invention. It’s a good book, not particularly scientific if we start to take it apart, but suggestive and interesting. And I care more about suggestive and interesting than I do about scientifically accurate, particularly when we’re talking about something as difficult to understand as creativity — and the creative impulse. The books I find most useful are those that offer an interpretation of the world that allows me to see parts of it in a new way. And this book does.

I’m only about a third of the way through, but I was struck by Csikszentmihalyi’s description of the three steps needed for creativity — I would say they are needed for creating good art in general. They are the three things every artist must do.

1. Internalize the system.

“A person who wants to make a creative contribution not only must work within a creative system but must also reproduce that system within his or her mind.”

In other words, as a writer, I work within a “system” that is literature. To work well, I need to know literature, know it thoroughly and deeply. I need to have read a lot of books, studied them, thought about them. If I don’t know the field I’m working in, it’s very difficult to be creative within it — to even create good art within in. I think this is why, when I decided to go back to school, I instinctively chose a PhD over an MFA. I wanted a thorough grounding in English literature, and I’d had bad experiences with poetry workshops. They had given me no grounding in poetry itself, the history of poetry or even poetic technique. (Now I teach in an MFA program, and I can tell you that we give students plenty of grounding, both in history and technique. But this was what I thought at the time.)

To create art in a field, you need to both learn it and then internalize it, to have it within you. Know it so deeply that it becomes part of your makeup. When I have trouble writing a sentence, I reach for Jane Austen or Virginia Woolf or Isaak Dinesen, as though they were tools in my internal cabinet. When I see waves, white and black, I hear Prufrock (which may be some sort of mental disease, actually).

2. Be motivated to work within the system.

That’s an accurate title, but really what I mean, and what Csikszentmihalyi means, is that you must be the sort of person who likes to play within the field you’ve chosen: who will write poetry even if no one reads it, who will write novels whether or not they’re published. You have to generate ideas and work for their own sake. In other words, your motivation must be internal, and out of it you must produce, and produce.

I see this with my friends who are artists and writers — they are constantly writing, constantly making art. They never stop. I’m not sure they could. I am sitting here on a Saturday morning writing a blog post, after staying up until 2 a.m. last night revising a chapter of my novel, because this is what I love to do. I love words the way Cleopatra loved jewels. A life of dealing with words, of teaching writing and of writing myself — I can’t think of any way I would rather spend my time.

Why is this important? Well, because it’s only out of that motivation, that enjoyment and sense of play, that you actually produce enough to (a) get better and (b) throw away what isn’t good enough.

3. Apply the critical apparatus of the system to discard inferior work.

Some art isn’t good, or isn’t good enough. You must know enough about what is and isn’t good to discard what, in your own work, is inferior. In other words, you must develop taste.

This can be a bit of a problem, because criteria of taste change over time, and you must have enough taste, be bold and innovative enough, to see what is good even before other people, often respected people within the system, recognize it. You must be able to say, “Yes, that Monet, he’s got something.” But I think the basic idea is sound: you need to be your own editor. What has helped me with this, more than anything else, is editing the work of other people — in other words, teaching writing. I can see when writing is trite, flat. I can diagnose what’s wrong with it, how it needs to change. And hopefully, I can see when those things are true of my own work, although I often cringe as I tell myself that what I’ve written isn’t good enough. It takes courage to be your own editor, but if you want to be good, you have to be. It’s a fundamental requirement.

Those are the three steps, and I think I’ve gotten better at each of them with time. That’s something else Csikszentmihalyi talks about, which is that it takes a lot of time. There are shortcuts in life, but not in art. There are efficiencies, meaning that if you study writing in a good program, it will teach you a lot about writing that you won’t get, or will get more slowly, by just writing on your own. But there are no shortcuts: you still need to put in the work. “Butt in Chair” is still the motto of all writers.

If I think of how long it’s taken me, simply to get where I am? I was writing regularly in high school — my first publication was in the high school literary magazine. So I’ve been writing for at least two decades. And there are days when I feel as though I’m just starting to get it . . . (But then, in an interview he did at ninety, Jorge Luis Borges said that some day he hoped to write the work that would justify him. I don’t think artists are ever satisfied.)

I think these three steps are important, or at least important to me personally, because I see people who are missing one or two of them, and they aren’t working the way I want to. Outsider artists don’t necessarily internalize the system, and they produce genuinely interesting work — being outside the system can be freeing. But it is often limiting because the artist remains outside the conversation going on within the system, in which works of art speak to each other, or lacks the craft, the technique, to be flexible, to produce a body of work that changes over time rather than replicating ideas and forms. Picasso immersed himself in the system before he did his own creative work — that man imitated everyone. Lacking critical faculty can be a real problem, because our culture does not necessarily reward good writing. You write a best-seller, and you think you’ve done good work because a lot of people are reading it. But the book will be gone within ten years because it doesn’t have the depth and complexity of great literature. I could go on, but won’t, because this post is already long enough and I have other things to do. After all, someday I hope to write the work that may justify me . . .

January 19, 2014

Being Photogenic

I’m writing this post because several friends of mine who are writers asked me to. I feel a bit awkward about it? In part because I’ll be posting pictures of me, and one is always criticized for that, and in part because I suppose it’s a frivolous topic, although how we appear to the world is usually important to us. And particularly important to writers, who are in a strange position, nowadays: they are photographed a lot, and those photos are used for publicity or posted online. And yet, they’re not performers, not actors or singers who are used to appearing in front of people. They are usually introverts, whose deepest relationships can be with imaginary characters.

Anyway. In the last couple of years, I’ve been getting a compliment that’s new to me, and surprises me: “you’re so photogenic.” Usually I say “thank you,” but if the person giving the compliment is also a writer, I say, “I’m not, actually. I’ve just learned how to be photographed, most of the time.” I suspect that no one is actually photogenic after the age of twelve. Children are photogenic, but adults . . . we’re too self-conscious, too aware of what the photograph might look like. So this is a blog post on being photogenic. I’m sure you’ve heard that “pretty is a set of skills”? Well, so is photogenic. I write this with a caveat: I’m not a photographer or a makeup artist, and I’m sure someone who is could do this much better than I can. The below is simply what I’ve learned as a writer, so that when I look at photos of myself online, I mostly don’t groan. (There are plenty of older photos of me online at which I do groan. Oh well.)

Everything I’ve learned has come from doing a professional photo shoot and being on video of various sorts, including a television show. There’s nothing quite like seeing yourself on early-morning television in Little Rock . . . And I should add that I took the pictures below in the worst possible conditions: mostly in the terrible lighting of my tiny pink bathroom, while recovering from quite a lot of traveling. All right, I think that’s enough with the caveats. On to what I’ve learned.

So, what is involved in being photogenic?

1. Attitude.

You must believe you are beautiful. Don’t laugh: you know what I mean. There you are, having your picture taken. You smile, wait for the click of the camera, and just at the moment it clicks, you think, “But I’m not beautiful. My pictures always turn out terribly, and this one will probably turn out terribly as well.” At that moment, your face takes on an expression of fear, apprehension, doubt. And that’s what makes it into the picture. So, you don’t have to believe you’re beautiful all the time. But at that moment, the moment the picture is taken, you must believe that you are worthy of being photographed.

How do you get attitude? Having your picture taken is like everything else: it’s a skill, and you get better at it with practice. So take your own picture. Take it a lot. You probably have a digital camera? Discard the photos you don’t like, keep the ones you do. Think about why you like them, what makes them work for you. Think about how you like to be photographed. This is me, with attitude:

At least, I think it’s attitude. Nothing about this picture says “I don’t think I’m worth photographing.” (Remember what I said about the terrible lighting and my tiny pink bathroom? Yeah, sorry. But if I can produce a picture I feel good about under those conditions, then I can produce a good picture anywhere.)

2. Makeup.

Sorry, this won’t help most male writers, who tend not to wear makeup. (Male actors and many male singers do, of course.) But the standards by which men judge their appearance tend to be looser, more lenient, anyway. They cut themselves more slack. This section is mostly for women, although if you’re male and doing a professional photo shoot, or if you’re on television, you may well use foundation of some sort. Or have it used on you!

So, here’s the thing: the camera isn’t taking a picture of you. The camera doesn’t know you, the wonderful scintillating person you are. The camera is taking a picture of certain planes and angles, in certain lighting. Makeup helps you control how the lighting falls on those planes and angles.

This is me, with nothing on my face except moisturizer. (And by moisturizer, I mean Proactive, because I have what is called “problem skin,” meaning that it breaks out if you say Boo! to it.) I happen to think it’s a perfectly nice face, but like this, it’s difficult to photograph.

This is my face with the most important step in the makeup process, which is foundation. Here, I’ve started with a thin layer of Garnier BB Cream, then MAC Studio Fix, and then MAC Studio Fix pressed powder. That sounds as though it would be heavy, but it’s not: modern cosmetics are designed to feel light. Foundation gives me a lot more control over how light will fall on the planes and angles that are my face. (Reminder: the camera isn’t taking a picture of you. You may as well be a mountain range, as far as it’s concerned.)

Ironically, skin with foundation on it looks more natural, more like your own skin, on camera than your own skin does. I don’t know why — I’m sure a photographer could tell us?

And here is my face with the color added: lipstick, blush, eyeliner, two kinds of eyeshadow (dark under the eyes and on the lids, light on the brow bone), and mascara. These are from MAC and Revlon, but I won’t give you specific names or colors, because you’ll need different ones anyway. We’re all different.

(Oh, and by the way, any male readers who feel like telling me, at this point, that they prefer women without makeup? I don’t wear makeup for you. Both men and women have been wearing makeup since this thing we call civilization started. We wear it because we’re human, and like to play. Not wearing or liking makeup is perfectly fine, but doesn’t get you a moral cookie.)

So, why wear makeup if you’re going to be photographed? Obviously, you don’t have to. But I’ve found that it gives me more control over how a photograph will turn out. It combats the flattening and washing out that is an inevitable part of being photographed.

3. Angles.

Another reason to take photographs of yourself is so you’ll learn the angles of your face. Like all faces, yours will photograph differently depending on the angle from which the picture is taken. There’s a reason that, when I’m photographed by someone I don’t know, I turn my face to the right.

Here’s a shot of the left side of my face:

And here’s a shot of the right side (I feel like I’m doing Dovima here, and if you don’t know who she is, Google her):

In photos of the left side, I tend to look younger, more vulnerable. Also, strangely enough, more foreign. (Hmmm. Is that a picture of my shadow self? My writer brain starts to work on this concept . . .) The right side looks older, more sophisticated. Photographers talk about your “good side”? Well, it’s my more reliably photogenic side. And here I am head-on (which is a very hard shot to take, by the way, in a bathroom mirror). I almost never take a shot head-on because my features are asymmetrical, and the photo can come out looking strange.

Oh, and by the way, I’ve been focused on faces. But here’s a picture of me in a full-length mirror. In this picture, I am dressed in a terrible outfit for being photographed in: loose black t-shirt, old jeans (you can see a paint splotch on them), Timberland boots for going out into the snow with. Which is actually what I did about five minutes later — go out into the snow. What makes this picture not terrible are the angles of my body. If you look at actresses on the red carpet, they all angle their bodies in a similar way to be photographed. And it’s not just because standing this way makes you look thinner (although it does). It’s because the angles add a sense of movement, and therefore visual interest.

4. Lighting.

Lighting will make or crush and crumple up your picture. Lighting is all. That said, most of the time writers are photographed, it’s in the terrible lighting of a convention hotel. We can’t depend on good lighting.

What you need to do is work with the lighting you have. Figure out where it’s coming from, think about how it will hit your face, and turn so it’s as flattering as possible. Again, that’s something you learn from photographing yourself. That said, some lighting is never going to be pretty. For example, I went out in my Timberland boots and took some photos in the cold gray light of a winter day in Boston. Nothing you take in that light will be “pretty.” It’s just too harsh. So what do you do? If you want pretty but can’t get it, go for cool. Actually, that’s one of my principles: always go for cool. Pretty is boring. Cool has movement and impact. Cool is better.

This is the best picture I was able to take in that light, and I kind of love it:

I love the red of that hat and the lipstick, against the cold white of the skin, the gray and black of the background. I don’t think this picture makes me look attractive, but who cares? The picture itself looks interesting.

Nevertheless, there are times when we want to look pretty. That’s when you want a soft, indirect light. My desk lamp is perfect for this. It almost always gives me a good picture, like this one:

And that’s about it! If you’re at a convention and having your photograph taken, think: where’s my lighting, what’s my angle? And at the moment that picture is taken, think, “I’m beautiful.” Because, of course, you are. (The makeup, if you choose to use it, goes on beforehand.) I can’t guarantee the picture will turn out well, but once you’re “photogenic,” you should be able to look at most of the photos of you posted online and not groan.

I’m going to end with one of my favorite photographs, from a party I went to recently in New York City. The guests were mostly writers and editors, and of course there were going to be photos taken. This was taken before the party with my camera by Marco Palmieri, who takes wonderful photos anyway. But I think you can see all the elements I’ve been talking about in it. The writers in the picture are Nancy Hightower, Valya Dudycz Lupescu, Bo Bolander, and me. We are dressed differently, we have different makeup, we are all interacting with the camera in different ways. But each of us is doing what works for us individually, and I think the end result is terrific.

January 3, 2014

XII. The Rose

This is the twelfth and final section of my story “The Rose in Twelve Petals.” If you would like to see the previous sections, look below!

Let us go back to the beginning: petals fall. Unpruned for a hundred years, the rosebush has climbed to the top of the tower. A cane of it has found a chink in the tower window, and it has grown into the room where the Princess lies. It has formed a canopy over her, a network of canes now covered with blossoms, and their petals fall slowly in the still air. Her nightgown is covered with petals: this summer’s, pink and fragrant, and those of summers past, like bits of torn parchment curling at the edges.

While everything in the palace has been suspended in a pool of time without ripples or eddies, it has responded to the seasons. Its roots go down to dark caverns which are the homes of moles and worms, and curl around a bronze helmet that is now little more than rust. More than two hundred years ago, it was rather carelessly chosen as the emblem of a nation. Almost a hundred years ago, Madeleine plucked a petal of it for her magic spell. Wolfgang Magus picked a blossom of it for his buttonhole, which fell in the chapel and was trampled under a succession of court heels and cavalry boots. A spindle was carved from its dead and hardened wood. Half a century ago, a dusty hound urinated on its roots. From its seeds, dispersed by birds who have eaten its orange hips, has grown the tangle of briars that surround the palace, which have already torn the Prince’s work pants and left a gash on his right shoulder. If you listen, you can hear him cursing.

It can tell us how the story ends. Does the Prince emerge from the forest, his shirtsleeve stained with blood? The briars of the forest know. Does the Witch lie dead, or does she still sit by the small-paned window of her cottage, contemplating a solitary pearl that glows in the wrinkled palm of her hand like a miniature moon? The spinning wheel knows, and surely its wood will speak to the wood from which it was made. Is the Princess breathing? Perhaps she has been sleeping for a hundred years, and the petals that have settled under her nostrils flutter each time she exhales. Perhaps she has not been sleeping, perhaps she is an exquisitely preserved corpse, and the petals under her nostrils never quiver. The rose can tell us, but it will not. The wind sets its leaves stirring, and petals fall, and it whispers to us: you must find your own ending.

This is mine. The Prince trips over an oak log, falls into a fairy ring, and disappears. (He is forced to wash miniature clothes, and pinched when he complains.) Alice stretches and brushes the rose petals from her nightgown. She makes her way to the Great Hall and eats what is left in the breakfast dishes: porridge with brown sugar. She walks through the streets of the village, wondering at the silence, then hears a humming. Following it, she comes to a cottage at the village edge where Madeleine, her hair now completely white, sits and spins in her garden. Witches, you know, are extraordinarily long-lived. Alice says, “Good morning,” and Madeleine asks, “Would you like some breakfast?” Alice says, “I’ve had some, thank you.” Then the Witch spins while the Princess reads Goethe, and the spinning wheel produces yarn so fine that a shawl of it will slip through a wedding ring.

Will it come to pass? I do not know. I am waiting, like you, for the canary to lift its head from under its wing, for the Empress Josephine to open in the garden, for a sound that will tell us someone, somewhere, is awake.

(The painting is The Soul of the Rose by John William Waterhouse.)