Theodora Goss's Blog, page 26

July 15, 2013

The Question

If you follow this blog at all, or follow me on Facebook or Twitter, you know that I have a corkboard over my desk. On it, I have several stickies on which I’ve written quotations that I want to remember. Here are a couple of them:

If you ever find yourself in the wrong story, leave. –Mo Williems

Do what I do: hold tight and pretend it’s a plan. –The Doctor

What would you do if you weren’t afraid?

(I don’t know who said that last one, but I know I read it on Terri Windling’s blog.)

I’m thinking of addinga sticky to the corkboard, but what I want to write on it is such a self-help cliché that I’m hesitating. Which is silly. What I want to write is a question, and it’s an important question for me to remember, because it’s one I should be asking frequently. Here it is:

Am I loving myself?

Love is both a noun and a verb: it’s both an emotion and an action. To love someone means not just to feel love for them but to act lovingly toward them. The act itself is a manifestation of love. So when I ask, am I loving myself, I’m not just asking how I feel about myself. I’m asking how I’m treating myself, whether it’s with love.

Obviously, the answer is often no . . .

Often, I don’t in fact treat myself particularly well. I get mad at myself and tell myself all the ways in which I’ve failed, or I’m inadequate. I don’t give myself the things I need: time to rest or take long walks, nourishing food. I push myself too hard. I blame myself for not giving other people what they need or want, even when it’s not possible or would involve significant sacrifice. Or I just make the sacrifice. (Is this a familiar list? I bet you’re nodding.)

What I need to do is treat myself as though I were in a relationship with myself. (In a sense, I am.) I need to take myself out, give myself treats, show myself that I care. Make sure that I’m taken care of. I’m not always so good at this . . .

That may seem selfish in that it’s self-ish, about the self, having to do with the self. But I think if we don’t love ourselves first, we end up not loving other people particularly well either. We start to resent them, because we know that we are missing something. We may expect them to supply that thing, but you should never depend on another person to supply the love that you aren’t giving yourself. That’s your job, not theirs.

So the question is there to remind me: I’m not going to useful, or productive, or loving, unless I love myself. And that’s an action, or rather the action is as important as the emotion. In fact, the emotion doesn’t need to be there for me to take action. Even when I don’t feel love for myself, I can act lovingly toward myself. I can buy myself flowers, take myself on a long walk, give myself time to rest. And then, often, the emotion will come — I will remember that I do love myself, despite how much trouble I can be sometimes.

I thought I would include two photographs in this blog post. The first is of me with the students at the Alpha Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror Workshop for Young Writers, where I was teaching last week. I had such a wonderful time at Alpha!

The second photo is of me with two lovely friends of mine, Nancy Hightower and Valya Dudycz Lupescu. This was taken at Readercon, the convention I attended last weekend.

I’m including them because loving myself also includes doing what I love: teaching wonderful students like those at Alpha, and spending time with my wonderful friends. Those are gifts I give myself, like buying myself flowers.

July 7, 2013

Self-Reliance

Yeah, I know. Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote an essay called “Self-Reliance,” and I’m not exactly going to top that, am I? Anyway, I’m not trying to rise to his level eloquence. This for example:

“A man should learn to detect and watch that gleam of light which flashes across his mind from within, more than the lustre of the firmament of bards and sages. Yet he dismisses without notice his thought, because it is his. In every work of genius we recognize our own rejected thoughts: they come back to us with a certain alienated majesty. Great works of art have no more affecting lesson for us than this. They teach us to abide by our spontaneous impression with good-humored inflexibility then most when the whole cry of voices is on the other side. Else, to-morrow a stranger will say with masterly good sense precisely what we have thought and felt all the time, and we shall be forced to take with shame our own opinion from another.”

Yeah, I’m not competing with Ralph . . .

Anyway, this is about a particularly small and local kind of self-reliance: the kind that allows you to visit a museum by yourself, or eat dinner by yourself in a restaurant. I’m writing about it because I know a lot of people who don’t feel comfortable doing those things. Either they don’t feel comfortable being alone or they don’t feel comfortable having other people see that they’re alone. Those are two different things, of course — and I’ve met people who fall into both categories.

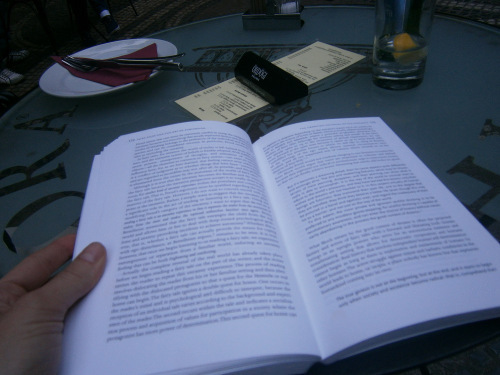

I thought I would include some pictures of me eating dinner on my last evening in Budapest, all by myself at my favorite restaurant. Here is the courtyard of the restaurant:

I can only speak for myself of course (Ralph would probably agree with that), but I value my solitude. I love spending time with people, but if I don’t get time to spend with myself, by myself — I become quite cranky. It’s part of being an introvert, I suppose. I love to travel by myself, and one benefit of doing so is that I get to see what I want, to think my own thoughts about it rather than having to tell other people what I’m thinking or having them continually tell me what they’re thinking. My favorite hosts and guides are the ones who simply let me do what I want, and I try to be that sort of host or guide myself, when people are visiting.

So, while I love people, I also love spending time alone. I suppose that’s one reason I feel so comfortable going to a museum by myself, or sitting in a restaurant by myself. But also, I always seem to meet people that way . . .

This is the book I was reading in the restaurant: Jack Zipes’ Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion. So I suppose, really, I wasn’t alone. I had the cantankerous, opinionated Zipes with me, and I had my favorite waiter to talk to, and I was surrounded by people speaking in English and Hungarian. It was lovely to sit and experience all that, without distractions.

The other reason people feel uncomfortable being alone has nothing to do with missing other people — they would feel perfectly comfortable being alone in their houses, as long as no one could see them. It’s that being alone is accompanied by a sense of shame. It’s as though being alone implies they have no friends, that they couldn’t find anyone to go with them. They are self-conscious. And I understand that — our culture emphasizes extroversion, the importance of being social and having friends. I guess the thing is, when I’m doing something alone, I never feel a sense of shame — I always have a conviction that I’m being fascinating and adventurous. Surely anyone who notices me is thinking, who is that woman sitting by herself? What is she reading? She looks so chic and sophisticated, all by herself . . . At least, that’s my conviction. But, probably more accurately, I suspect that no one notices or cares. That no one is judging me — everyone around me is simply going on with their lives.

It seems silly, to be ashamed of being alone . . .

This, by the way, is what I had at that final dinner: Hortobágyi Húsos Palacsinta. It’s one of my favorite dishes in the whole wide world, but you can only really get it in Hungary.

It’s important, at least for me, to be self-reliant. To be able to travel by myself, go into a foreign city with a map and walk around. To figure out exchange rates, visit the museums. Go to restaurants. Ask for help if I need to, laugh when I mess up.

And to be alone. I love my friends, who are wonderful. But I also need my alone time; I also need to wander around a city all by myself, looking into shop windows, browsing the bookstores, thinking my own thoughts . . .

I’ll send with something Ralph said, because he’s good people, is Ralph:

“Trust thyself: every heart vibrates to that iron string. Accept the place the divine providence has found for you, the society of your contemporaries, the connection of events. Great men have always done so, and confided themselves childlike to the genius of their age, betraying their perception that the absolutely trustworthy was seated at their heart, working through their hands, predominating in all their being. And we are now men, and must accept in the highest mind the same transcendent destiny; and not minors and invalids in a protected corner, not cowards fleeing before a revolution, but guides, redeemers, and benefactors, obeying the Almighty effort, and advancing on Chaos and the Dark.”

July 5, 2013

An Adventuress

I want to be an adventuress.

But that term has been used in some pejorative ways, so I have to specify what I mean by it. What I mean is a female adventurer. You know, like those Victorian women who went to distant lands, and learned the local languages, and climbed the Himalayas — often in not very practical Victorian clothing. Why then don’t I simply use the term adventurer? I suppose because it doesn’t have the same feel to it, the same sense of breaking boundaries and doing it with a sort of style and grace. I want some of the connotations of the word. But not others, because the term often describes women who use their charms and wiles to live off men — and that’s the opposite of adventure. An adventure requires self-reliance, guts. An adventure involves discovering yourself.

This was the conclusion I came to, that I wanted to be an adventuress, after returning from Europe. Which happened yesterday, actually. Yesterday morning I was in Budapest, and today I am in Boston. This is the last picture of myself that I took in Hungary, leaning against the railing of the Szabadság híd (Liberty Bridge), looking at the Danube. It was almost sunset: Budapest has the most gorgeous light at sunset.

What I learned, being in Europe for two months, was how easily I moved around, how much I loved the act of traveling. Of looking out a train window. Of getting into an airplane and flying to another country. Of carrying adapters, and trying to figure out new plumbing arrangements, and making my way in another language. Did you know that in England, there are no electrical outlets in bathrooms? It’s illegal, so you have to go into another room to dry your hair. Also, all over Europe, it’s useful to know the term “to take away,” which is equivalent to the American “to go,” because you are charged more for food that you’re going to eat in.

I like going to museums and seeing original paintings for myself: Renaissance art, for example, looks completely different for real than it does reproduced. It’s only when you see it for real, and up close, that you realize its complete brilliance. In Brussels, I saw Landscape with the Fall of Icarus by Pieter Bruegel (at least we think it’s by him, but maybe not say the art scholars). I had the impulse to bow before it, as though I were meeting an important personage . . . I like figuring out maps and metro systems, walking through a strange city and seeing the architecture, coming upon small cafés and bookshops. In Budapest I found an English bookshop and bought too many books. In Brussels I came across an outdoor antiques market and bought some English transferware coffee cups. Ever after, I can look at those things and say, yes, I found that copy of Margaret Atwood’s Alia Grace in Budapest. Or I brought those cups all the way back from Brussels.

There are good and bad things about being an adventuress. It means that I’m not very good at living a quiet life. I need to be doing things, going places, and there’s a sort of restlessness in that: I always feel as though I should find contentment in simply being. But that’s not who I am, and I think it’s better to accept that about myself than fight against it. I want a life of adventures and new experiences — sometimes those are uncomfortable and inconvenient, sometimes they can even be frightening. I don’t like inconveniences any more than the next person, and I try to avoid dangers. But the lure of adventures, of new things, even the smallest — of using different kinds of money, eating different kinds of foods! That is a great and powerful lure.

I think I’ll add one more picture, also of myself looking at the Danube that final evening. It was hot and I had put my hair up — I twist and tuck it, and it stays up by itself. But the bridge was windy, and the wind blew my hair down, so I ended up with this. I’m ending with it because I think it makes a fine Portrait of an Adventuress.

June 24, 2013

Grand Narratives

When I was in London, I had a long talk with a friend of mine who said something that struck me. He said that in his life, he wanted a “grand narrative.” And he had gotten one: he’s a musician, composer, and rock star. He had decided on things he wanted to do in his life, and he had done them, and they did in fact create a grand narrative — a fascinating story. His biography would be a terrific read.

I think many, perhaps most, people don’t want a grand narrative. I’ve known many that do, but then I spend my time with writers and artists, and they are more likely to want their lives to be fascinating stories. They are more likely to want grand narratives. (Although many of them don’t want grand narratives either — they simply want to do the work, and have the work speak for them.)

It seems almost vain or frivolous to want a grand narrative for one’s life — as though one should be satisfied with the work, and with a measure of security that allows one to do the work. And yet, it’s hard not to want a fascinating biography, a life in which unexpected things happen. At least, I find it hard not to want that, and after all, here I am writing this post at a coffee shop in Budapest. That’s pretty dramatic, isn’t it? And here I am telling stories about my life, on this blog, and Facebook, and even Twitter.

The pictures I’m going to include in this post are from the Hungarian National Gallery, the art museum I visited yesterday. Here is the art museum, which is housed in the castle on Castle Hill.

Pretty dramatic, isn’t it? I think it’s hard not to want a certain amount of drama and excitement in our lives. And to be honest, what I’ve noticed is that the people who want it, who want the grand narrative, tend to get it. They do in fact tend to have dramatic lives, the sorts of lives that would make good biographies. I suppose that to a certain extent, we all get what we want, what we expect for yourselves, because that’s what we work for. (Not completely, of course, which is why I qualified that statement. But our expectations do seem to determine our possibilities, at least in that what we don’t want or believe we can have, we usually don’t try for.)

This is the castle from below, when you’ve climbed down the hill and are ready to cross the Chain Bridge.

And this is the Chain Bridge, which is also pretty dramatic, with all its lions. I think every bridge needs lions, don’t you? Lots of lions, as many lions as possible and as good taste will allow. We all need lions to add drama to our lives.

And finally, here is me on the Chain Bridge, in front a beautiful design and some graffiti. That’s so Budpest: the Art Nouveau decoration and the graffiti both.

Many of my favorite writers and artists did have grand narratives. Isak Dinesen, Virginia Woolf, Georgia O’Keefe . . . They did not necessarily have happy lives, and the problem with grand narratives is that they’re not always happy. I’d like to have the grand narrative and the happiness both. But I understand what my friend meant by wanting a grand narrative. I want one of my own, and I think I’m doing a pretty good job of creating one — well, as much as I can. And then, I also want to do the good work . . .

June 23, 2013

The Art Museum

I grew up going to art museums. My mother always took me, although we have very different tastes in art: she likes modern art, by which I mean late 20th century. I like art of the 19th and early 20th centuries. When I was old enough, I would go into Washington D.C., where I lived as a teenager, and spend the afternoon at the art museums. Luckily, in D.C. all the museums are free, or I could never have afforded to go . . .

Whichever city I’m in, I always go to the art museums. In Boston, I’m a member of the Museum of Fine Arts, and here in Budapest, I knew that I wanted to go to the large, official art museum, the Hungarian National Gallery, before I left. I hadn’t been in a long time, because when I’m here I’m often with friends, and we go see the more touristy things. Not the art. But yesterday, I finally had time to go, and so I went.

The Hungarian National Gallery is in the castle at the top of Castle Hill. That means it’s an all-day trip, because I have to get up the hill, and then see the art in the museum, and then get back down the hill. That takes several hours. Yesterday was a perfect Saturday for it, except for the heat. But at least it was cool in the museum . . . This art museum is different from most of the large official art museums I visit, because it focuses specifically on Hungarian art. There’s no effort to include a token Picasso or Matisse for example, as you find in so many other art museums, and certainly in the American ones. I like that: it means you get to see all the art movements as they filtered through one particular country. I have a favorite Hungarian artist, and I’ll include three of his paintings here, each of which I saw in the museum yesterday. His name is Pál Szinyei Merse (1845–1920).

This is a painting called The Skylark:

I loved seeing the history of art through this particular national lens. It was particularly interesting to see late 18th and 19th century academic art applied to Hungarian subjects: incidents from Hungarian history, village celebrations, famous Hungarian beauties of their day. It was a lovely change from seeing the same techniques applied to English, French, or Italian subjects, which is what I’m used to.

What the museum made clear to me is the richness of the Hungarian artistic tradition, from the middle ages up to World War II. The period of the Hungarian Secession, which was the name given to the Hungarian version of Art Nouveau, was particularly inventive and original. It was a uniquely Hungarian interpretation of an international art movement, and you can see its effects in the architecture of the city, all over Budapest. That was in the late 19th and early 20th centuries — my favorite period, of course. And then, World War II happened.

This painting is called Faun and Nymph:

Judging from the art in the museum, World War II was devastating for Hungarian art. To my eye at least, Hungarian art after World War II, at least as represented in the museum, was entirely imitative. I found it interesting that even in the museum’s collection, World War II formed a dividing line in terms of art history: 20th century art to 1945 was displayed separately from 20th century art after 1945. And the art after 1945, to the 1980s — I’m not entirely sure how to describe it, except that although I don’t love the abstract expressionists, I do admire their innovation and power. But I’m used to looking at the spectacular American examples in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, or in the museums in New York. These paintings were abstract expressionism without its power. And they did not seem particularly Hungarian anymore.

And here is The Balloon:

I am, of course, open to being told that I’m wrong, that important art was happening in Hungary during that period. That I just didn’t look closely enough, or that it isn’t represented in the museum collection. I would be interested to hear a contrary opinion.

I don’t have any particular words of wisdom to end this blog post, except ones I’ve written before: that it’s so important, for writers particularly, to go to museums, to see art. No matter how small the museum, you always learn something. You always take something away with you, like a gift . . .

June 20, 2013

Hitting the Target

I’m reading Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood. I’m only at the beginning, a couple of chapters in, but it’s making me think about writing with a sort of precision, so that every word is perfect, every word counts. That’s what Atwood does, and it’s part of the reason she’s such a good writer. Every word she writes hits the target, at the center of the target.

I thought I would give you an example. These are the first three paragraphs of the first chapter:

“I am sitting on the purple velvet settee in the Governor’s parlour, the Governor’s wife’s parlour; it has always been the Governor’s wife’s parlour although it has not always been the same wife, as they change them around according to the politics. I have my hands folded in my lap the proper way although I have no gloves. The gloves I would wish to have would be smooth and white, and would fit without a wrinkle.

“I am often in this parlour, clearing away the tea things and dusting the small tables and the long mirror with the frame of grapes and leaves around it, and the pianoforte; and the tall clock that came from Europe, with the orange-gold sun and the silver moon, that go in and out according to the time of day and week of the month. I like the clock best of anything in the parlour, although it measures time and I have too much of that on my hands already.

“But I have never sat down on the settee before, as it is for the guests. Mrs. Alderman Parkinson said a lady must never sit in a chair a gentleman has just vacated, though she would not say why; but Mary Whitney said, Because, you silly goose, it’s still warm from his bum; which was a coarse thing to say. So I cannot sit here without thinking of the ladylike bums that have sat on this very settee, all delicate and white, like wobbly soft-boiled eggs.”

What is it about these paragraphs that I find so perfect? The novel is about Grace Marks, a notorious murderess — who may not be a murderess after all, I don’t know yet and I’m not sure Atwood is going to tell me. Here I’m seeing the world through Grace’s eyes; she’s the one describing her surroundings. And I get such a sense of her as a person. She notices trivialities, she had a clear sense of her position and also her grievances, she is an astute social observer. She also speaks in a way that is poetic, almost stream of consciousness — when Atwood moves into the perspectives of other characters, the language becomes more structured, more typically Victorian. So the language fits the character. And I love the freshness and precision of the images, particularly the bums like wobbly soft-boiled eggs. I can see those women, can’t you?

But finally I think it’s a matter of ear, the fact that the sentences all sound right: there isn’t a wasted word in them. All the words fits into the rhythms of the sentences. Language is like music in that you can hear when it works. You can hear the perfection of a Mozart sonata, and you can hear the perfection of prose that is hitting its target. It’s the satisfaction of an arrow sinking into the center. (The target is your mind, your heart.)

It’s good for me to be reading this novel now, when I’m writing my own. What I’m writing is a first novel, and an adventure story of sorts. It makes no effort to be as sophisticated as Alias Grace. I’m not going to be Margaret Atwood, not on my first try! But it’s useful to have prose of that quality going through my head as I’m trying to write my own.

June 18, 2013

Fascinating People

I wanted to title this post “How to Be Fascinating,” but there isn’t enough space on the sidebar for a title that long.

I’ve been very lucky, as a writer and scholar, to be able to meet so many fascinating people. (And it really has been a function of being a writer and scholar: when I was a lawyer, I met people who made for interesting stories, but who were not fascinating in and of themselves. Like the Swedish media mogul Jan Stenbeck, who turns up in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo by Stieg Larsson. He makes for a good story — he once threw a pen at me. But he was not an interesting person to talk to.) I’ve been thinking about what makes them so fascinating.

By fascinating, I mean that these are the people you want to meet, and then talk to for hours, because they have so much to say, and what they have to say is so interesting, so engaging. Before you meet them, you think they’re going to be fascinating, and then you meet them and they are. (These are also the people whose interviews you want to read, because you care about their opinions, their interpretation of the world.) So, here’s what I’ve come up with: this is a primer on how to be fascinating.

1. Be fascinated. The fascinating people I know are always fascinated — by books, art, places. They are continually experiencing things. It’s as though their brains are sponges, continually soaking things up. They are constantly looking outward, experiencing the world. That doesn’t necessarily mean traveling a lot, although many of them do travel. They can get interested in the history of roses, or how to raise goats, or the differences between the folk and literary versions of “Little Red Riding Hood.” It’s so easy to become comfortable or complacent, to do the same things in the same ways. To, at some point, stop learning. But the fascinating people I know never do.

2. Think deeply about what fascinates you. The people I know who are fascinating have also thought deeply about what they have encountered in life and the world. They have opinions, but those opinions are informed and considered. When I’m with them, I feel as though I’m learning, as though my own understanding is becoming deeper. And it may be an understanding of something as superficial as knitting patterns. But the fascinating people I know think deeply even about knitting patterns. And through that deep understanding, something happens: they change. They are not merely collections of information: it’s not fascinating to have someone tell you the history of roses, for example. To talk information at you. Fascinating people seem to be able to integrate that information: it becomes part of them, part of a larger narrative, a deeper comprehension.

3. Share your understanding with the world. The people I know who are fascinating share the insights they’ve gained, the understanding their experiences have given them. They communicate to an audience in some way. I should say here that I find people interesting in general: I like talking to people, finding out about their lives and thoughts. But what I’m talking about in this blog post are the truly fascinating people, the ones whose thoughts get passed around. The ones whose words or images or choreography or research change us. The ones who make me say, I wish I could meet her. I’d love to hear what he has to say. And I don’t mean people who are famous. It can be as simple as seeing a blog post that makes me go, “Wow, that’s fascinating. I wonder what the writer is like.”

I feel as though I’ve only touched on this topic imperfectly and in a preliminary way. But I’ve been lucky to know such people, and it’s interesting to think about what makes them who they are. I don’t think they ever set out to be fascinating. They get fascinated, and then they start trying to develop a deeper understanding, and then they feel impelled to communicate with the world. So I guess the message is, if you want to be fascinating? Don’t think about it too much. Just start thinking about what fascinates you . . .

The photographs in this blog post are from the gardens of Castle Drogo. They are all from the Rhododendron Garden, which was planted in the 1940s. (I was interested in the garden design because I think many of the plants are probably original, and for me the colors are rather garish. But I think that was the height of garden design in the

1940s? The history of plants and gardens is one of my personal fascinations . . .)

June 16, 2013

Writing the Novel

I’m writing the novel. Not a novel, but this particular novel.

Or should I say that I’m learning how to write a novel? This novel.

I find it very difficult to talk, or write, about writing the novel. So why don’t I show you some pictures? These are pictures of Castle Drogo, which I visited while I was in Chagford, Devon. (Two weeks ago, but honestly, it’s starting to feel like a lifetime ago.) Here’s a bit of the castle, which is actually too large to photograph in its entirety:

And here is the front entrance to the castle:

Castle Drogo was built in the 1910s and 20s, which means that everyone in Devon who mentioned it did so a little scornfully. It was not a real castle. But of course that was exactly why I wanted to visit. The turn of the century is my era, the era I studied as a PhD student and the era in which my novel is set. I wanted to see the building repeatedly described as the last castle built in England.

The castle itself was undergoing renovation, which was unfortunate. You can see the fences around it in the photographs above. I’ll have to go back once it’s been renovated and see the castle with all its original furniture. But I did take pictures of one particular room. Don’t laugh: it’s the bathroom.

You see, in order to write this novel, I need to know how people lived their daily lives. I need to know about things like bathrooms. In London, I saw some turn of the century bathrooms in ordinary houses. Here is a bathroom in a castle. I don’t know about you, but I want to know what sort of bathroom a turn of the century castle would have.

Since I’ve been in Budapest, I’ve been focusing on the novel, and it’s actually going well. At least I think it’s going well: this is the first draft, and it’s inevitably going to have a lot of problems, a lot of things I’m going to have to go back and revise. But if I can get the plot right, if I can describe the basic action of the book, I’ll be doing well. Then will come the difficult process of making sure it all works. That happens in revision. (I’m daunted by the prospect of going back and revising — there will be so much to revise! But I’m trying not to think about it.)

This is so different from writing a short story. I’ve written enough of those that I rarely spend much time revising anymore. When the story comes to me, it comes to me as a whole. I know the arc, I know where it will end. I can just sit down and write it, focusing on the writing itself, on how I will tell the story I already know. But I’m discovering this novel as I write it: it’s only recently that I’ve known how it will end. (Although I already know what the sequel will be about.) I’m not even sure where the ending will take place, although I think this is a London novel. I’m glad I spent so much time walking around London, figuring out how much time it takes to get from one place to another!

One of the things I’ve had to deal with is that it’s difficult for me to believe I can actually write a novel. I seem to never believe I can do something until I actually do it — and then it seems intuitive, easy! Anyone can be a corporate lawyer! Anyone can finish a PhD! Anyone can write a novel! That’s that I will think when I’m done. But I try not to let my inability to believe in myself stop me. As Georgia O’Keefe once said, “I’ve been absolutely terrified every moment of my life and I’ve never let it keep me from doing a single thing that I wanted to do.”

It’s difficult to write about the novel when I’m still in the middle of it, but I’m very glad to be in the middle of it, very glad that the writing is going well, that I’m finally focused. It’s taken me a long time to get here, a long time even to figure out how to write this novel. (I had a sort of false start. I was trying to write like someone else. That doesn’t work, in case you were wondering.)

Perhaps, really, it’s taken me a long time to become the person who could write this novel. I think we have to be certain people in order to write certain things. And then the process of writing changes us, and we become other people . . . So often, we talk about writing as a skill, as something that can be learned. And it is, in part. But it also integrally has to do with who we are. What we produce, what we can produce, has to do with who we are at any particular time. I think that I’m writing this novel now because I’m finally ready to write it. How will it come out? I’m not sure. I hope it will be good. No, I’m not going to think about that. If it’s not, I’m going to make it good in revision . . .

June 14, 2013

Dreaming and Writing

I’ve been writing down my dreams. Or trying to, because of course dreams start to slip away as soon as you wake up.

The reason I’ve been writing them down is that I’ve been reading books on myths and fairy tales, some from a psychoanalytic perspective, and they speak of dreams as emanating from the unconscious, of containing unconscious material that we can access and bring to light. And I’ve been wondering if this is true, if dreams contain important information rather than simply being random collections of images reprocessed from our conscious life. I’ve wanted to find out for myself.

The images in this blog post are from my mornings in Budapest. The first is of morning light coming in through the very tall windows of my grandmother’s apartment. The apartment building was built in the 1840s, I’ve been told. The ceilings are very high, about twenty feet, I think. So these windows are much taller than they look in the photograph. The trees I see through the window are in the park around the Nemzeti Múzeum.

For a long time, I avoided paying attention to my dreams, because what I remembered were the unpleasant ones. And I dream vividly, in intense detail, so the unpleasant ones were very unpleasant. I didn’t want to remember them.

But since I arrived in Budapest, I’ve kept a notebook next to my bed, and when I wake up, I jot down whatever I remember. Not in detail, since my dreams are too detailed to capture in their entirety. But jotting down enough information that I remember what the dream was about.

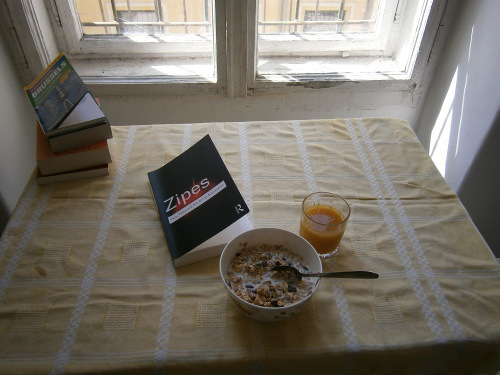

This is my breakfast: muesli, peach juice, and theorizing the literary fairy tale. The view is out the kitchen window into the courtyard, which I think used to be where the carriages drove in.

So far, I’ve learned a couple of things. One is that without an alarm, I naturally sleep nine hours a night. So sleeping five hours, which is the most I got some night during the semester, is probably not a good idea, is it? I think I need sleep, need a significant amount of sleep, and when I don’t get what I need, I’m not healthy or even happy. So that’s a useful lesson in itself.

The other thing I’ve learned is that I dream many times a night, many dreams: each time I wake up, I remember a different one. (Since the daylight comes in, I wake up several times in the morning, and if I’m still tired, I go back to sleep. I love the daylight coming in. I hate drawn curtains, hate to wake in darkness. When that happens, I always feel groggy.)

I can usually only remember the last dream or two, but I know there have been many, that I’ve dreamed many dream lives in the course of a night.

This is me in the distorting hall mirror, ready to go out for the day. The weather here in Budapest has been wonderful: warm, sunny. It’s definitely summer skirt weather, whereas in London a week ago I was wearing a fleece jacket and boots.

And as I expected, my dreams are intense, detailed. While I’m in the dream, I don’t remember that I’m dreaming, that I have another life, a life I call “real.” For the time I’m in the dream, the dream is my life, my reality. This is disconcerting when I wake, because I have to adjust and remember that I’m now in my “real” life. I have to remember what day it is, where I am in the world.

This is where I want to make a connection with writing (after all, I called this blog post Dreaming and Writing). I don’t know if it’s like this for other writers, but when I write, it’s as though I’m having a waking dream. I’m observing the story I’m telling as though it were reality, as though I were in it (although not participating in it). It’s happening all around me. I’m immersed in the story.

This is my writing desk. It’s not exactly ergonomic! I have to put a pillow on the chair to raise me up enough so I can type comfortably. I don’t think that television has been on since the 1970s.

When I emerge from writing, it’s an experience as disconcerting as waking up, as emerging from a dream. I have to try and remember what day it is, where I am in the world. It’s as though I’ve spent several hours in a version of sleep.

So what does all this tell me? Well, I’m going to keep trying to write down my dreams. I want to see what else I can learn about them. But what it suggests to me is that there is something profoundly complicated about the creative process. When I’m being creative, I’m putting myself into a certain mental state, changing what my brain is doing and how it’s relating to the world in a profound way. That seems important.

It also suggests that writers are very strange people. I suspect that artists, dancers, musicians all go through a version of the same thing: that they change mental states while creating and performing. What does it mean to be that sort of person? What does it mean to live with that sort of person? It must be difficult . . . (Writers can be difficult people to live with. I know that I am never entirely there, wherever I am. Part of me is always somewhere else, particularly when I’m working on a project, as I am now.)

And here is my table in the internet cafe down the street. This is where I am now, typing this blog post. That is a small latte, and it is genuinely small: about half the size of a latte in London or Boston. But in London, I can drink several small lattes throughout the day. In Boston, I can drink two at most, because the coffee there is so much stronger. And here in Budapest? This is my limit! Even the caffeine in this small latte is almost too much for me. But it’s the best coffee I’ve ever had, anywhere, ever.

The truth is, and I don’t know whether this is a good truth or not, that I don’t write to produce stories. Or for any of the superficial reasons: fame, fortune (neither of which are guaranteed anyway). No, the reason I write is that it’s always been my way of getting there, to that particular mental place where I’m living in a dream. Where my brain is functioning in a particular way. My desire to go there is like an addiction, and I suspect if I didn’t write, I would start going all wrong, the way people go wrong if they don’t dream.

Ray Bradbury said, “You must stay drunk on writing so reality cannot destroy you.” I think that’s sort of what I’m talking about . . .

June 12, 2013

Meeting Artists

I love meeting artists. I love meeting writers too, of course. I travel a lot, and everywhere I go, I try to meet other writers. Whatever our backgrounds, we immediately have a common language: of wordcount, royalty payments, and more important things such as the stories we want to tell. What we want to do, where we want to go, with the worlds we’re creating. We talk about our art and the technicalities of its production.

But I love meeting artists because they’re doing something so different from what I do, yet related to it. Particularly artists who are working with the mythic, with fairy tales and fantasy.

While I was in Chagford, Devon (just a week ago, although it feels strange to think of it now, sitting as I am in a café in Budapest — the thing about traveling is that after a while, all the places you’ve been start to seem like dreams, like places in stories you’ve told or read), I met three wonderful artists. I thought I would write about them, in case you haven’t heard of them or seen their art.

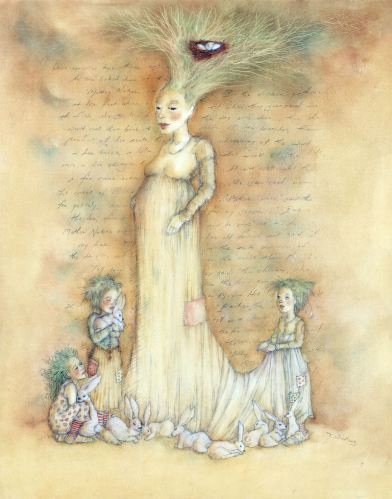

The first was Terri Windling. If you’re reading this blog, I’m sure you’ve heard of Terri, but perhaps as a writer or editor rather than an artist. However, she’s a wonderful artist. I had the privilege of wandering around the hillsides with her, seeing the magical landscape she calls home. I even spent time in her studio, doing some research in her collection of books on fairy tales. She has a website for her writing called Myth & Moor, but also a website devoted specifically to her art called Bumblehill. If you’re interested in her artwork, take a look at her Etsy shop, also called Bumblehill. I thought I would include a link to one of the prints she has posted there right now, “Mother Nature“:

(Funnily enough, since I’m in Budapest, all the Etsy prices are in Hungarian Forints!)

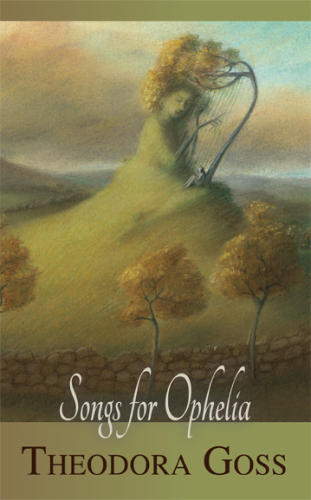

The second artist I met was Virginia Lee. I’ve known about Virginia’s art for years: I’d actually asked for a painting of hers to be the illustration for my first short story collection. But I’d never met her in person, and it was lovely to spend some time with her, looking through her work. (Artists! They take you to their studios, where they have stacks of original paintings, just lying on top of each other. And you gasp as you look through a stack of treasures . . .) Virginia also has an Etsy shop called Virginia Lee Art, but it’s empty at the moment, so I’ll post the cover of the poetry collection I’m currently working on, which will feature a painting of hers:

Here is a link to the original, called Moorland Melodies.

(Yes, I know, I’ve been working on the poetry collection and promising it for a while. I’ll get it done soon, I promise!)

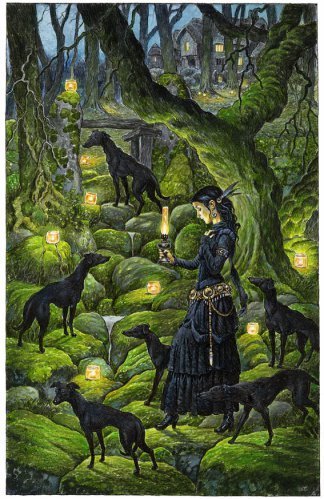

The third artist I met was David Wyatt, whom I learned about through Terri’s blog. David is an accomplished illustrator, with many books to his credit, but my favorite paintings of his were the ones he’d done for himself, simply because he had wanted to. Many of them are available as prints in his Etsy shop, David Wyatt Illustrations. My favorite of them all is this one, Mariana and the Black Whippets:

There are several reasons writers should keep in touch with artists. The most practical is that we always need illustrations, whether for covers or the interiors of books. And although we often don’t have control over who does the illustrating, sometimes we can make suggestions. But the deeper reasons have to do with inspiration, with getting ideas for our own work, or from the way artists work and think about their art. One of the most valuable things I do as a writer is keep in touch with artists who inspire me. It was so nice to meet three of those inspirations!