Theodora Goss's Blog, page 29

December 30, 2012

Going to Museums

Yesterday, Ophelia and I went to the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. The Gardener Museum was once the house of Isabella Stewart Gardner, a wealthy woman in the late nineteenth century. After the death of her husband, she turned to collecting; eventually, after her death, she left her house and collection as a museum, with the proviso that it not be altered. And it generally hasn’t been. The collection itself is interesting and idiosyncratic: it looks a bit as though she traveled through Europe picking up whatever struck her fancy, and what struck her fancy were often quite beautiful things. I told Ophelia that we were going to visit a castle, and the museum does rather look like a castle on the inside. This is the central courtyard:

I think I go to museums with Ophelia so often because I was taken to museums so often as a child. And not just museums: we were always going to ballets, operas, plays, concerts. (I was usually bored at the concerts.) Without thinking about it too much, my mother was steeping us in culture — I say without thinking about it too much because it was the way she herself had grown up. You did not necessarily have money — my family lost all its property after the war, and was only compensated for it after the fall of the communist regime — but you could always have culture. You could always know music and art. Where I grew up, in Washington D.C., most of the museums are free, so we would go in whenever we wanted, and often on weekends I would simply wander around the National Galleries or the Hirshhorn. Museums still feel like home to me: I feel perfectly at ease in them, as some people do in churches. I love to wander around and then sit in the café (there is always a café) with a cappuccino, reading or writing.

At the Gardner Museum, I took Ophelia to the café, which was terribly overpriced. But I suppose that’s part of the experience I’m giving her — I want her to feel comfortable in museums, and know how to behave in cafés and restaurants. (She’s eight, so I’m in the midst of that — trying to make sure she knows how to behave appropriately in public, knows the codes. Because living in society means knowing and negotiating a set of codes, doesn’t it? And I want her to know it, so that if she later wants to break the rules, she’ll know what they are and how to break them. You have to know a system if you want to rebel against it.) Today we are working on how to dress for an evening at the theater, because we’re going to Boston Ballet’s new Nutcracker at the Opera House. (I wanted to write this blog post before it was time for me to get dressed.)

I got something very special out of going to museums as a child, something I think most children don’t get. It seems to be reserved for an elite, although it shouldn’t be. (I was certainly not part of a social elite, as a child. Except perhaps educationally.) It’s the sense that human culture belongs to me, and I belong to it. That I participate in it. Picasso and Matisse are not intimidating. They are brothers in arms, and we are all trying to create something, to produce art of various sorts. Of course, some parts of that culture belong to me more than others, simply because of my own cultural heritage, and I would be wary of using material from non-European cultures. I would use it, but with more care. Nevertheless, there’s a sense, not so much of ownership, but of participation.

That matters to me deeply in my own art, and it’s something I want Ophelia to have as well.

December 27, 2012

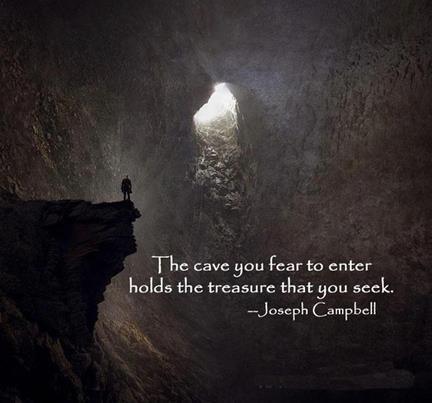

The Cave

On Facebook this week, I found the following quotation from Joseph Campbell:

Now, you should never trust a Facebook quotation, and of course I checked to see if Campbell had ever said this. He probably hadn’t, in exactly that form. What he may have said is something like this, in a lecture: “Where you stumble, there lies your treasure. The very cave you are afraid to enter turns out to be the source of what you are looking for. The damned thing in the cave, that was so dreaded, has become the center.”

So you’re afraid to enter the cave, you enter, you stumble in the darkness because the ground is rocky. But somewhere in that cave is the treasure, the thing you are looking for. To find it, you have to enter the cave in the first place.

I could write a blog post on overcoming fear and venturing into the cave. Except that’s not my problem. I always go into the cave. I’m not even sure why. I think I do it on principle, because I know that if you give in to fear once, you are more likely to give in to fear twice. You are more likely to hold back the next time, to say no, the cave is too dark, the ground too rocky. The things I’m afraid of are the same things I think we’re all afraid of. We often think of bravery as jumping out of airplanes, but seriously, who’s afraid of jumping out of an airplane? No, the things we’re afraid of are failure, loneliness, poverty. Being lost, facing rejection. Ultimately, death.

Being a writer means that you confront all of these. The path itself is a lonely one, and you face a continual possibility of rejection and failure. (You may remember that some time ago I wrote about how I deal with negative reviews? Everyone gets negative reviews. Well, to deal with mine, I read James Joyce’s negative reviews. I scroll through his one-star reviews on Goodreads. Seriously.) A book may be rejected by every publisher, a book may be published and fail. Poverty is a very real possibility. It’s easy to become lost. You can’t be a writer without going into the cave. I go into the cave so I can get used to being afraid. When I started going to conventions, I would always volunteer to moderate panels, in part so I would be put on panels, because there was always a need for moderators. You see, for some reason people are afraid to moderate. So I would find myself in front of two hundred people, moderating a panel that consisted of writers such as Samuel Delaney and Barry Malzberg and John Clute. When you do the things you fear, over and over again, you lose your fear of them. And you become used to the feeling of being afraid, so when you have to do the next thing you fear, you’re already accustomed to it. You know what it feels like. Eventually, you begin to want it, the feeling of being at least a little afraid, of moving past your comfort zone. You start to realize that if you’re not, to at least a certain extent, staring into the abyss, you’re not really living. You’re not even really writing.

So my problem isn’t going into the cave. My problem is that I always go into the cave, and then I stumble and fall. Not always of course, but sometimes. Then I feel stupid, and blame myself for having stumbled. For having failed to live up to expectations. That’s what I need to work on. Because I’ve met so many people who never even venture inside. People who tell me they have traveled the world, but when I ask them about it, reveal that all the trips were planned, were comfortable. People who call themselves romantics, but are afraid to fall in love — deeply, passionately in love with another person. Writers who are afraid to work on longer projects because of the fundamental fear that they will fail — that they will not finish, or the book will not find a publisher, or once published it will not sell.

What I need to do is pick myself up, mend anything that’s been broken, and say to myself, but I ventured into the cave. Of course I failed — that’s the sign of having tried. And then I need to look around for that treasure.

We should wear our failures as badges of honor, I think. Show off our scars, as soldiers used to show off the scars they gained in duels . . .

December 25, 2012

The Hellebore

I don’t usually write blog posts late at night. But tonight, I felt as though I had to. Earlier today, I had been scrolling through Facebook and had seen the image I’m including in this post: a picture of a hellebore. This post is a response to that image.

You see, hellebores are among my favorite flowers. I value them particularly because they bloom in winter, when all the other flowers are asleep, underground. They are a promise: that spring will come again, despite the darkness, despite the snow. Facebook is silly: you and I both know how silly it is. But sometimes it does allow you to see something magical, simply because it’s populated by human beings, who are intermittently magical. Some more than others, of course . . . Seeing this hellebore was like getting a glimpse of another country, like getting a sign that said “Wait, hope.”

Here, in case you are wondering what I’m talking about, is the image:

Tonight, I was trying to answer a question, which was, “Why do I feel so sick?” I thought, it’s the rich food — I never eat the way I’ve eaten in the last two days. (I had marzipan for breakfast.) I thought, it’s the lack of sleep — I’ve been overworked for so long now that I don’t remember how to be anything else. But no, I concluded. It’s something else, something deeper, a sickness not of the body but of the soul — and any sickness of the body is a symptom of that underlying sickness. I’ve gone too long needing something that is difficult to find — that deep connection with the world, or the world behind the world: the reality behind all our human games and constructs. I’ve gone too long saying and doing what I’m expected to, being who I’m expected to be. Moving through the world automatically, in a way I’ve learned to move through it, because don’t we all? So as to create the least possible friction.

Once upon a time, I lived in a teeny-tiny house in a forgotten town close to Boston, and I had a garden, in which I planted hellebores. They would come up every winter. I always dreamed that someday I would have a house with a large garden, one which bordered a wood, and in the wood I would plant all the wild flowers: hellebores, which are wild, and the old species daffodils, and fritillaries. I mention this because gardens can connect you to what is real, if they are real gardens, magical gardens. (Mine was magical.)

I’ve been so busy that I’ve barely been writing, and when I do write, it’s because someone has asked me for a story and offered me money for it. I barely write poetry anymore, because there’s no money in it. And yet I think poetry keeps us from becoming sick, and I think I’m healthiest when I can write poetry. It’s a sort of thermometer for the soul. (It occurred to me tonight that there is a certain irony in the fact that the world will pay me enough to live on for teaching others to write, but not for writing myself.)

The hellebore: it reminded me of all this, and helped me diagnose my own illness. But it cannot answer the question that remains, which is, what then? How to effect a cure? And that, I don’t know. But it does hold out the promise of spring after the snows . . .

December 22, 2012

The Black River

I went walking beside the river today. The river is a neighbor of mine, just out my back door and across a road. I visit it often, and what I’ve noticed is that it has its moods. Today the water was black and roiling. It was one of those cold, gray New England days, the day after the solstice, when it still feels as though light has drained from the world, even though you know, intellectually, that it’s coming back.

This is what the water looked like:

Looking down into that black water from the bridge above, I started thinking about our desire for the apocalyptic, our secret wish that the world would in fact end. We’ve seen this recently, haven’t we? I think we see it every few years. It seems to be a recurring aspect of human civilization: someone announces the apocalypse, and there is much rejoicing. Of course, the apocalypse never arrives. What we get instead is life going on, with its series of small apocalypses, intermittent acts of violence that seem to have no meaning. Instead of the end of the world, we get a shooting here or there. I suppose one attraction of the apocalypse is that it would provide us with meaning, with closure. That would be it, instead of this going on and on, this continuation of ordinary life.

I think at some level, I can understand why someone might be driven to acts of destruction. We call those acts senseless, but I’m not sure they are, and I suspect that part of my duty, as a writer, is to make sense of them. It’s not a pleasant duty: but I am a writer, and nothing human should be beyond me. Unfortunately, violence is all too human. To understand it, I have to understand what creates violent or destructive impulses in myself. Thinking about this, I immediately remembered Freud’s idea of the death drive, the desire for something that is not life, for a return to the inorganic. There are all sorts of ways in which I disagree with Freud, but I agree with him that we have that impulse, because I can feel it in myself. I am not afraid of heights. No, what I’m afraid of is jumping. It’s the part of myself that asks, what if I did? (I suspect many of us ask that question, and this is a case in which having a vivid imagination is a liability.) I can understand the desire for violence as a rupture of the ordinary, of daily continuity. I can understand how in certain circumstances, someone might want something, anything, to happen. A war, a bomb, a shooting. And I believe it’s important to understand, because only by understanding something can we present an alternative.

I believe that the opposite of violence is not peace, but art.

Art is a way to commit the extraordinary, to rupture ordinary life. To move us to a different plane of significance. It is the way to express most completely all that we are, including our will to life, our desire for death. A great work of art is an apocalypse, a bomb in the mind. It is at once an act of creation and destruction. I can’t walk through a room of Van Goghs without feeling that I am being remade, that parts of me are falling away, that I must change in response. When I write, it is as though I can jump into the dark water without actually jumping. Metaphor saves us . . .

Alice Walker wrote, “Writing saved me from the sin and inconvenience of violence.” That makes sense to me.

This is what the river looked like, when I pointed my camera not down into the water but across it. The buildings of the city glowed in the light of sunset. Day by day, this time of year reminds us, the light returns . . .

December 21, 2012

Keeping it Simple

Today was one of those days you spend running around, trying to do all the things that need to get done, and they’re all such small things, but they need to get done or there will be trouble and inconvenience to follow. For example, while I was in New York, one of the nose pieces on my glasses fell off: you know, those small pieces of plastic that keep the glasses on your nose. Of course, you can’t wear the glasses without them. So an important errand today was running to my optometrist’s and having the nose piece fixed. Such a small thing, and yet so necessary.

And I had to buy milk, because while I was gone the milk had gone sour, which means that I can’t make myself oatmeal for breakfast. And while I was out, I bought groceries just in general, including new flowers, because my flowers had mostly died. I’m not sure why, but in a fit of extravagance, I bought two bouquets, so I had plenty of flowers left over. Here is the main arrangement, on the table:

And here is the arrangement in the bathroom:

There are so many of those fiddly little things in our lives: glasses nose pieces, and cell phone batteries, and keys. Heels on shoes. They need to be fixed, or copied, or recharged, or glued on. Oh yes, and on my way home I had to pick up a new toaster, because I had spilled water on the counter and my toaster no longer worked. So I stopped in the hardware store and bought a new one.

I mention all this because life is full of such things, such errands. And if you want to live an interesting life, an artistic life, you have to minimize them. You can’t always be concerned with the fiddly things. I try to do that, conscientiously: to simplify. To have as few bills to pay as possible, to arrange my life so that I’m not endlessly taking care of things. So that the fundamental activities of life are simple. That’s partly why I’m so glad that I don’t have a car, which takes endless care. Last week, I packed my bag, got on the subway in Boston, got on a bus to New York, got on a subway in New York, and there I was: spending almost a week in New York, going to see and do fabulous things. This summer, although I’m not sure about this yet, I may well be doing the same thing, except in Europe. You would be astonished at how easy it is for me to pack, get on the subway, get on an airplane, get on the subway, and be in an apartment in Budapest. Or a house in London. Or anywhere.

That’s not to say that my life isn’t very full. Right now, it’s too full. I had a long meeting with a friend of mine in New York who is also in the publishing industry, and I told him that what I really needed right now were an agent, an accountant, and an assistant. And honestly, if I keep doing the sort of work I’m doing, steadily, those things will be necessary in the next year. But at least they’re part of my work. I try to simplify my life so that my work can be as complicated as it is.

And so that I can live fully, think and feel deeply. Create the complicated work I want to. That’s where I want the complication to be: on the page, in the story. So in life, I’m trying to keep it simple. Not that it always works, of course. But I do try. (My glasses are fixed, I have milk in the refrigerator, my toaster can even toast hot dog buns. And I have new flowers in my apartment. That means I’m good to go . . .)

December 17, 2012

Finding Your Core

I’m sitting in an apartment in Brooklyn that belongs to the fabulous Maria Dahvana Headley. I came down by bus on Saturday, and I’ll be going back to Boston again on Thursday. My schedule here has been very, very full. On Sunday, I had lunch with Ellen Datlow, who has edited so many wonderful magazines and anthologies, and then on Saturday night, Nancy Hightower and I went to a magical party. It took place in a beautiful apartment belonging to the artist Cynthia von Buhler, in Manhattan. The guests were some of the most fascinating women in the arts that I’ve ever met: writers, artists, actors, creators in various media. The apartment itself was gorgeous: high ceilings, antique French furniture, mirrors and crystals and candlelight. It will give you just an idea if I post a picture of the stuffed peacock:

Yes, there was a stuffed peacock on the wall, and a lovely little dog so well-behaved that he did not bark at all at two white doves (not stuffed like the peacock, but performing doves that perched on our hands and flew around the room). It was like being in an enchanted palace for a little while. We talked about our lives and read from our work, and everyone there was beautiful and talented, and involved in such interesting projects. Here is me, underneath the stuffed peacock:

I didn’t get back to Maria’s apartment until very late, around 3:30 a.m. Today, I had lunch with Asimov’s editor Sheila Williams. I have more lunches and dinners and coffees planned with writers and editors this week, and then on Wednesday night I’m going to the KGB Bar reading with Ben Loory and Mary Robinette Kowal.

It’s a very busy visit.

And it’s made me think about something that you learn in dance classes: movement comes from the core. Your core is the set of muscles around your abdominal area, the area from which moment in dance usually starts. When you move your arms and legs, you want to move them from the core. They don’t just move by themselves. They are supported by those strong muscles, from the hips to the middle of the rib cage. In order to dance well, you have to strengthen your core.

I think that over the last year, I’ve developed a strong core, metaphorically, in terms of my writing. I know what I’m doing and where I want to go. I have a clear vision of the sorts of stories and novels I want to write. What I need now is a strong core personally. I feel as though I’m still missing that, and when I travel, as I am doing now, I feel it: I can tell that I’m missing something. A sense of stability, a sense that I belong somewhere. If you don’t belong anywhere, all places are alike to you, which reminds me of a Kipling story but I don’t remember which one. Sitting here in an apartment in Brooklyn, I feel somehow rootless. I want to put down roots somewhere, so that when I go traveling, I always know where I will return to. Perhaps that’s the work of the next year.

That, and of course writing.

Writing this entry made me think of a sort of mantra: I am a ship made for sailing, and I shall not fear the storm. But I would like to know there is safe harbor somewhere.

December 12, 2012

Being Liminal

Sometimes, I annoy myself.

Tonight, for example. It’s cold outside, and my calves still hurt from a dance class I took on Monday, and I don’t want to go to another. But guess what I’m going to do? Go to a dance class, because it’s cold, and my calves hurt, and the class is going to be hard. I’m going because it would be easy to stay home and stream something on the computer, lying in my warm bed. But that’s not what I do, is it? No, I do the hard thing, because I’m me, and that’s what I always do. Annoying.

But I feel as though I have to do something, or anything, or perhaps everything, because at the moment I’m in a liminal state and it’s driving me mildly crazy. You know what a liminal state is, right? Arnold Van Gennep wrote about them in The Rites of Passage. According to Van Gennep, all rituals have three states: the pre-liminal, the liminal, and the post-liminal. The pre- and post-liminal are both stable social states. The liminal state is the state in between, the threshold over which you need to step to assume a new position. Except sometimes you get stuck in the threshold. Or sometimes the threshold just takes a lot longer to get through than you thought it would.

Well, I’m in that liminal state, between things: and I have no idea where I’m going. In a sense, I’m waiting for the universe to tell me, because I simply don’t know myself. The liminal state is the state of transformations, the state in which you change. In a ritual, it’s the state in which a young man goes out and becomes an animal for a period of time, living in the wilderness. It’s the state in which a young woman is socially out, but not yet engaged. It’s carnival. In life, it can often be a period of indecision, a period during which you feel as though there’s no ground under your feet. At the moment, I can’t feel the ground. I don’t know where I belong.

The problem with the liminal state is that it’s dangerous: Van Gennep tells us this. He says that the person on the threshold is at risk, particularly vulnerable. I can feel that — the vulnerability, the reaching out to something that might be more stable but not knowing where to find it. Liminal states last as long as appropriate: you don’t know when they’re going to end. They weaken you, and there are days on which I feel weaker than I would like, more tired.

I think that’s why I find comfort in things that are ordered. The ritual of teaching, the rigor of learning Hungarian (since I will probably go to Hungary next summer — unexpectedly, since I did not think I would be able to go), the language of ballet. When the teacher says tombé, pas de bourrée, glissade, pas de chat, I know the combination of steps to take. It’s nice knowing what steps to take, even if it’s only the next six.

My image for today is me after Monday’s ballet class:

I’ve had way too much uncertainty in my life to be comfortable with being liminal for long. I think I will end up with some sort of stability — I just don’t know when.

December 1, 2012

Being Responsive

Today, I looked at the date of my last post and realized it was November 17th, which startled me. I haven’t been good at posting, or at responding to comments. I wanted to explain why, because I think it goes to the problem that many writers have, keeping up with their writing lives as well as whatever other lives they might be leading.

There are so many people to whom I’m supposed to respond, in one way or another. The most important group is my students, who often need my help with their writing. But I get emails about all sorts of other things as well: things for me as a professor, for me as a writer. And then there are facebook posts and messages, twitter posts and messages. On an average day, I can end up responding to a hundred people or more. (Not necessarily individually, of course. But on Friday I taught, and was therefore responsive to, 48 students. You see how the number can climb.)

A friend of mine who is an extrovert told me that contact with other people energizes her. Because I’m an introvert, it wears me out. All of those responses are little bits of energy, going out from me to whomever I’m responding to. And right now, there isn’t very much replenishing that energy. It can be replenished in various ways: rest, beauty, pleasure. Contact with close friends, which is replenishing rather than draining. But those are all things I have very little time for right now, and as a result I am almost always tired. Too tired to be as responsive as I need to be.

Too tired to write, which is a problem. Writing is interesting because it’s the one thing that both drains and replenishes you. Writing a scene leaves me both exhilarated and exhausted. But I need to at least have enough energy to start. (And time. It’s the end of the semester, and there’s so little time right now.)

I don’t have any particular wisdom to impart here. I just need to figure out how to live differently. I understand why some writers become recluses: they can pour all that energy into their work. I can’t do that: I’m not enough of an introvert, and I would be lonely. But I need to find a balance, and I don’t know where it is.

So if I’ve failed to respond to you about something in the recent past, that’s why.

Over the last few days, I’ve had the last two lines of Dylan Thomas’s poem “Fern Hill” going through my head. You know what I mean, right? Here is the last stanza:

“Nothing I cared, in the lamb white days, that time would take me

Up to the swallow thronged loft by the shadow of my hand,

In the moon that is always rising,

Nor that riding to sleep

I should hear him fly with the high fields

And wake to the farm forever fled from the childless land.

Oh as I was young and easy in the mercy of his means,

Time held me green and dying

Though I sang in my chains like the sea.”

It’s beautiful, isn’t it? But when words go through our heads repeatedly, it’s the unconscious speaking to us. (That’s how it speaks to us: through dreams, through poetry). And that’s not a good message to get. It means that I’m feeling like a free thing chained, even though I’m singing. But this is a problem to solve, a dilemma to get out of. Maybe I need to go down to the sea? I mean actually go down to the water, which is only a subway ride away from me. Sometimes, when your mind gives you metaphors, it helps to actualize them. Which reminds me, oddly enough, of John Masefield’s “Sea Fever”: “I must go down to the seas again, for the call of the running tide / Is a wild call and a clear call that may not be denied.”

Maybe if I hear that wild, clear call, I’ll figure out what to do. Or maybe the sea itself, in its ancient beauty and wisdom, will spare me some of its energy . . .

(This is a painting called Mediation by the Sea that is hanging in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. I don’t think the painter has been identified. It comes from the 1860s.)

November 17, 2012

Being Ruthless

Today, I stumbled upon an interview with William Faulkner in the Spring, 1956 edition of The Paris Review. In it, he says this:

“The writer’s only responsibility is to his art. He will be completely ruthless if he is a good one. He has a dream. It anguishes him so much he must get rid of it. He has no peace until then. Everything goes by the board: honor, pride, decency, security, happiness, all, to get the book written. If a writer has to rob his mother, he will not hesitate; the ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ is worth any number of old ladies.”

I remembered this quotation particularly because the author Dan Simmons had posted it once, and gotten some fairly negative responses. (Dan is one of the first people who ever encouraged me, and I am forever grateful to him for it.) I remember one of them: a man who wrote that Faulkner was wrong, that a writer had a primary responsibility to his family, his community, his country — oh, this particularly man had a long list of things the writer was responsible to, all of which were supposed to take precedence over his writing. And I thought, no wonder I’ve never heard of him. He’s not a writer.

If you read the entire interview, you’ll see that Faulkner is being egotistical in a humorous way, in a sense posing as William Faulkner, playing himself. I like that about him. I like that he created a persona. Why shouldn’t he? Why shouldn’t writers write themselves as well as their stories? It’s certainly more entertaining for us, who read them. I mean, I’m glad J.K. Rowling went off and bought a castle. I’m glad Anne Rice used to arrive at readings in a coffin. I like it when writers have a sense of drama, of story.

But the quotation itself: I think it has a hard core of truth to it. And here’s that hard core. When you start writing, nobody cares whether you write or not. Your family wants what is best for you, which is often not writing, because writing involves making hard choices, including hard financial choices. I left law because I knew that I would never become a writer if I stayed in it. I think at some level, my family still doesn’t understand how I could have left a such a lucrative career. Your friends don’t care, because most of them don’t understand why you would want to be a writer in the first place. It’s only when you start becoming a writer that you make friends who are writers, and they do care — but that comes during the process. And when you start out, you have no readers. Once you have published some things that people have responded to, all this changes — then editors ask you for stories, agents want novels, readers let you know that your writing means something to them. But to get to that place, which can take a decade or more, you have to be ruthless. You have to prioritize your writing, because no one else will.

Of course, once you become successful and you’re making money, there are other things to be ruthless about — for example, ruthlessly following your own vision rather than writing the series that your editor or agent wants. It’s always best to have people around you, whether professionals or friends, who are on your side, who understand what you ruthlessly want to do, and actually support it. Then you can be a little less ruthless.

It’s the word “ruthless” that bothers people so much, I think. No, you shouldn’t actually rob your mother. But you may well rob her of a dream that you will someday be a successful lawyer or doctor. You may well disappoint her. That’s when I think it’s useful to remember Faulkner. To be a writer, you have to have a hard core yourself. You have to be willing to disappoint people, to say no, to take rejection. To be ruthless even to yourself, to refuse to put up with your own laziness and cowardice.

The arts are not for the faint of heart, you know.

November 12, 2012

Our Need for Romance

When I was a graduate student, I had money for necessities, but not luxuries. (Necessities were things like rent and heat. Luxuries were often things like clothes. That was when I got into the habit of shopping in thrift stores.) At some point, I mentioned to a friend that I missed being able to buy perfume. She sent me a whole bottle of Chanel No. 5. I used to wear it every day, and some days, I used to put just a little bit on before I went to bed, so I could smell it even in my sleep. I still have some left.

I don’t know if we all have a need for romance, but I think at least some of us do. I know I do . . .

I define romance broadly: in its modern meaning, it usually refers to romantic love, but in an older sense, it refers to the medieval romances, which were tales in the native vernacular (French, Italian, Spanish) rather than in Latin. They often involved knights, ogres and giants, ladies who lived beneath lakes or could turn into animals. They were tales of adventure and magic. I think we all need tales of adventure and magic in our lives.

I feel my own need for romance the most when I’ve been working very hard (as I have been recently). It feels as though I’m not truly living, merely existing. That’s when I want something interesting to happen. Something that tells me there is an underlying magic to the world, that life can be an adventure. Of course, as you can tell by this blog post, I’ve been feeling that way lately. It’s November, so the work is constant and it’s never done. But I hope there is some sort of magic and adventure in the near future, waiting for me. Sometimes I think that rather than making the future, we are pulled toward it, that there are certain nodes that draw us onward. It’s as though life is a matter half of fate and half of intention, both what we make it and what the universe wants of us. Sometimes I think of it as a dance: we are dancing with the universe, toward our futures, our fates.

I’ve gotten esoteric, I know. But what I meant to say was, I think many of us have a need for something other than ordinary life. We need it as a reminder that ordinary life is not all there is, that there is more. (And there is. I believe that.) There is courage, there is passion, there is beauty in the world. We can’t always see it, but it’s there. Those are all large things, and often we don’t have time for such large things, not in our daily lives. We only have time for smaller things, for small indicia of them. So we buy perfume; or wear long, elegant coats; or hang pictures of landscapes that remind us of our dreams. It is the most we can do, and some days that is enough. But it also reminds us that there is more to life, that the larger things exist.

I’m going to include one of my favorite pictures, which I may have posted before. It is John William Waterhouse’s My Sweet Rose, and it reminds me of our need for romance: our need to smell the roses on the wall, before winter takes them.